Cover price US & CAN $9.95 Regionally in New Mexico Display until Spring 2024 Newsstand display until September 30, 2023 POWER AND POETRY The Art of Rose B. Simpson SANTA FE ALBUQUERQUE TAOS ABIQUIU Plus ten more dazzling photo essays by some of our best artists behind the lens LOOKBOOK ANNUAL 2023 VOLUME 24

WOODS DESIGN | BUILDERS CONSISTENTLY THE BEST

and building the finest homes in Santa Fe for over 46 years photography

Designing

: © Wendy McEahern | Architectural Design and Construction

WOODS DESIGN BUILDERS 302 Catron Street, Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 • 505.988.2413 • woodsbuilders.com

: Woods Design Builders and Lorn Tryk

MICHAEL VIOLANTE & PAUL ROCHFORD 401 Paseo de Peralta, Santa Fe, NM 87501 505.983.3912 | vrinteriors.com convenient parking at rear of showroom

photo © Wendy McEahern

DAVID PEARSON PATRICIA CARLISLE FINE ART, INC. PEARSON STUDIO & SCULPTURE GARDEN 5 SCULPTURE | SANTA FE, NM 87508 505-820-0596 | CARLISLEFA.COM ADDISON DOTY (2)

Call to schedule a studio/showcase visit. Open 6 days a week. Closed on Thursdays.

STAN BERNING Stan Berning’s ART BOX | 901 Canyon Road | Santa Fe, New Mexico 87501 stanberningstudios.com | stan@stanberning.com | 928-460-2611 Abiquiu Inn / Cottonwood Grove, watercolor/gouache, 18” x 24”, 2023

View to Pojoaque / 8 AM, watercolor/gouache, 18” x 24”, 2021 Black Mesa / Clarified, watercolor/gouache, 18” x 24”, 2023

View to Pojoaque / 8 AM, watercolor/gouache, 18” x 24”, 2021 Black Mesa / Clarified, watercolor/gouache, 18” x 24”, 2023

SANTA FE SOPHISTICATION Santacafe.com 231 Washington Avenue 505.984.1788

Coyotecafe.com 132 West Water Street 505.983.1615

ETHELINDA Ghost Dance Lady - Southern Arapaho 60x40 oil on canvas 123 West Palace avenue 505.986.0440 info@manitougalleries.com

ETHELINDA Dutch 50x66 oil on canvas 123 West Palace avenue 505.986.0440 WWW.manitougalleries.com

SOFAS / CHAIRS / LIGHTING / CUSTOM UPHOLSTERY THROW PILLOWS / DINING / RUGS COLLECTIBLE & WALL ART / MIRRORS & MORE N EVER O RDINARY Always Extraordinary 530 South Guadalupe Street In the Historic Santa Fe Railyards 505.230.7000 Mon-Sat 10am-5pm / Sun 11am-4pm

1512 Pacheco St. A103 Santa Fe, NM 505.365.2687 VictoriaatHome. com Home Furnishings and Interior Design Retail and to the Trade

DANIEL NADELBACH

Wiford Gallery Art As Emissary www.wifordgallery.com | @wifordgallery SCIENCE BECOMES ART Come and see A NEW GENRE OF FINE ART from the Father of "vibrant toning on copper" TIM CHURCH exclusively at Wiford Gallery Santa Fe Opening July 21 at 5PM; through July 30, 2023 403 Canyon Road | (505) 577 - 0888

BETTE RIDGEWAY RED ON RED Santa Fe Palm Desert Carmel-by-the-Sea Sausalito Ft. Lauderdale Delray Beach Jupiter Naples Dallas Seattle Atlanta Charleston, SC RidgewayStudio.com PURE SENSUOUS COLOR

Euro-Asian Modernist We Dress Your Life 101 W. Marcy Street, #2 Downtown Santa Fe tokosantafe@gmail.com 505-470-4425 tokosantafe.com

DAN NAMINGHA 125 Lincoln Avenue • Suite 116 • Santa Fe, NM 87501 Monday–Saturday, 10am–5pm 505-988-5091 • nimanfineart@namingha.com • namingha.com • Representing Dan, Arlo, and Michael Namingha

HOPI HORIZON #29 Acrylic on Canvas 30˝ X 48˝ Dan Namingha ©2023

Jennifer & Kevin Box Studio & Sculpture Garden

Jennifer & Kevin Box Studio & Sculpture Garden

OPENING THIS SUMMER July 10 – October 13

Hero’s Horse, 2022 18’ x 18’ x 18’

Powder coated fabricated stainless steel KevinBoxStudio

New Mexico Landscape mixed media, 56" x 56"

KATE RIVERS

600

INGRAHAM

LINDA

Canyon Road Santa Fe, NM kaycontemporaryart.com

© 2023 Sotheby’s International Realty, 505.988.2533. All Rights Reserved. Sotheby’s International Realty® is a registered trademark and used with permission. Each Sotheby’s International Realty office is independently owned and operated, except those operated by Sotheby’s International Realty, Inc. All offerings are subject to errors, omissions, changes including price or withdrawal without notice. Equal Housing Opportunity. HEADQUARTERED ON THE HISTORIC SANTA FE PLAZA SINCE 1972 WEBSTERSANTAFE.COM | 505-954-9500 | THE PLAZA | 54 ½ LINCOLN AVENUE | SANTA FE Specializing in the Most Extraordinary! PROPERTIES, ART, APPAREL — PAST, PRESENT, FUTURE Chris, Patti, and Christopher Webster

sf rockers.com | RBWing | 505-490-9003 Repose, Relax, Reset | Maloof-inspired | Solid Wood Rockers Unique & Comfortable | $6,000 + tax santa

ocker

fe r

s

belt buckles + jewelry + gifts 662 canyon road | santa fe, nm 87501 505.986.9115 | johnrippel.com

PHOTO: © WENDY MCEAHERN FOR PARASOL PRODUCTIONS

Trend magazine is celebrating 25 years in print in 2024. 82 FourCities,SixMuseums: HowaNewCreativeCorridor PutsCultureontheSpot ThomasAshcraft’sHeliotown SUBYBOWDEN: ASantaFeArchitect PushestheBounds OfRegionalism SPRING/SUMMER2008VOLUME9ISSUE1 santafetrend.com SPRING/SUMMER2008 DisplaythroughJuly2008 U.S.$5.95Can.$7.95 ChangingtheVernacular: OneArchitect’sVision TheRailyard Gets ItTogether JudyChicago ShakesThingsUp TheGreening oftheEastSide LOOKBOOK summer 2016 HOPI POTTERY in New Light TOM JOYCE fuses the art and science of metal making PETER SARKISIAN’S sculptural enigmas 500 plus pages and will also be offered as a hardbound book. Looking back and celebrating the art + design + culture that is our legacy To order a special first-print, hardbound copy of our June 2024 25th anniversary issue, mailed to your home in the US. Send a check to Trend for $250.00 to P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504. FALL 2013 – SPRING 2014 Display through June 2014 U.S. $7.95 Can. $9.95 TREND ART+DESIGN+ARCHITECTURE FALL 20 1 3 SPRING 2014 VOLUME 14 ISSUE trendmagazineglobal.com LARRY BELL Sculptor of kinetic light CHRISTINE McHORSE Grand abstractions in clay WINKA DUBBELDAM The Dutch architect who has taken Manhattan and is remaking Bogotá PASSION OF THE PALATE Culinary Inspiration in Santa Fe, Albuquerque, and Taos 25 ArchitecturesofHappiness,Belonging,andImagination AsiaMeetsSantaFe: CostumingaU.S.PremiereOpera SolarBuildingGrowsUp EdgyLandscapes DisplaythroughOctober2007 U.S.$5.95Can.$7.95 HARMONY CUBED The art of Stuart Arends BEYOND STRUCTURE Rick Joy’s architecture as sensory experience DENNIS HOPPER Rebel with a cause ROMANCING THE MACHINE Santa Fe’s Concorso celebrates automotive high style ALSO: Rubik’s Cube of how to create a city that inspires us all of Santa Fe gallery openings, events, and cultural happenings $9.95 $9.95 LOOKBOOK Albuquerque

DOWNTOWN | 505.494.1453 | 125 West Water St MIDTOWN | 505.494.1407 | 444 St Michaels Dr Found exclusively in Santa Fe at Oculus Optical Botwin Eye Group | Oculus Optical

190

features

50 My New Mexico

A photographer is caught in the spell of the Old Southwest.

B y K evin Moloney

78 Worldly

In this picture suite, longtime New York Times photojournalist Lonnie Schlein takes you everywhere you ever wanted to go.

B y Su S an Spano

94 Nudes and Landscapes

A frequent Trend contributor contemplates and celebrates the female nude.

B y peter o gilvie

110 Another Day in Albuquerque

Photographer Eric Draper taps the city’s relaxed vibe, small-town feel, mingled traditions, and dash of the strange.

B y SiMon roMero

120 Life’s Work

A well-known gallerist and curator explores the work of Janet Russek and David Scheinbaum, the couple who helped to make photography a principal part of the Santa Fe art scene.

B y Stuart a . a ShMan

138 Audacity (What I Want to Say to Santa Fe)

Photographer Kate Russell observes the work of celebrated mixed-media artist Rose B. Simpson.

B y ro Se B. SiMp S on

150 Wanenmacher’s World Trend previews the deep, droll work of one of Santa Fe’s most spellbinding artists with photos by Kate Russell.

B y Cyndy tanner

160 Elusive Taos

A renowned photographer shares compelling words and pictures about a place few people really know.

B y B ill Curry

170 Quartet

Photographer Audrey Derell and four area artists make beautiful music in the studio.

B y gu SS ie Fauntleroy

190 In the Garden

170

Miraculous art photos by Nancy Sutor and Lonnie Schlein grounded in the nurture and intimate observation of a wild and wonderful New Mexico garden.

B y l u C y r . lippard

30 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Artist Geoffrey Gorman in his studio, photographed by Audrey Derell. Top: Nancy Sutor, November 5, 2022 (with cactus flower and hawthorn) from the series, Second Nature.

Otter Medicine

Troy Sice, Zuni Pueblo

The elements of both Earth and Water are present in otter medicine, which is connected with the primal feminine energies of life in balance.

Otter teaches us to reawaken our inner child, to share and to express joy for others.

Become like otter and move gently and playfully through the river of life.

Since 1981 Fetishes Jewelry Pottery 227 Don Gaspar, Santa Fe Keshi.com 505.989.8728

Carved shed elk antler with silver whiskers and pen shell and lapis eyes. Otters range in size from 7” long x 5” tall to 3” tall by 1 1/4” wide.

By Janna Lopez

201 DESIGN SOURCE

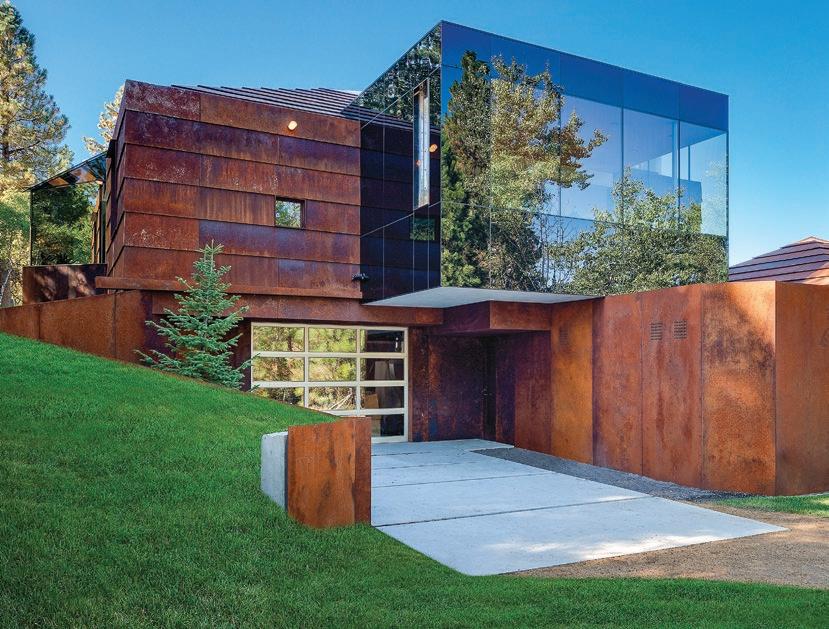

206 Robert Reck and the Rise of Southwest Regional Architecture

A master photographer and an architectural historian help us understand how old adobe evolved into some of the most striking contemporary architecture in the West.

By Elmo Baca

By Elmo Baca

225 PASSION OF THE PALATE

226 Off-the-Beaten Plate

Here’s something for people who’d like to eat their way around the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

By Susan Spano

230 Chef Olea’s Legacy Grace, dedication, and passion prove to be his life’s secret ingredients.

By Vani Rangachar

Photography by Daniel Quat

239 Ever Evolving:

The Cuisine of New Mexico

Four dynamic restaurants prove that nothing ever stands still when it comes to food and fine dining in and around Santa Fe

By Esther Tseng

Photography by Peter Ogilvie

250 Of Farm Stands and Food Security

Sustainable food production begins with compost, education, and joy at Reunity Resources in Agua Fria Village.

By Susan Spano

252 AD INDEX

34 TREND TEAM/MASTHEAD 35 FROM THE EDITOR 36 FROM THE PHOTO EDITOR 37 FROM THE PUBLISHER 38 CONTRIBUTORS 40 ART MATTERS The Contemporary Side of Things The New Mexico Museum of Art moves from modern to contemporary at a new companion showcase, the Vladem By Kathryn M Davis 42 FILM Silver Bullet Productions A not-for-profit gives Native American filmmakers a voice and prepares them for careers in a booming New Mexico industry.

Robert Reck, Reimers residence (2011) in Montana, designed by Eddie Jones.

departments 206

ON

THE COVER:

Rose B. Simpson, River Girls (2019).

32 TREND art + design + culture 2023

photo By K ate ruSSell

PUBLISHER

Cynthia Marie Canyon

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Susan Spano

ART DIRECTOR

Janine Lehmann

PHOTO EDITOR

Lonnie Schlein

COPY CHIEF

Vani Rangachar

PRODUCTION MANAGER & ASSOCIATE DESIGNER

Jeanne Lambert

CREATIVE CONSULTANT & MARKETING DIRECTOR

Cyndy Tanner

PHOTO PRODUCTION

Boncratious

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

Stuart A. Ashman, Elmo Baca, Bill Curry, Kathryn M Davis, Gussie Fauntleroy, Lucy R. Lippard, Janna Lopez, Kevin Moloney, Vani Rangachar, Simon Romero, Rose B. Simpson, Susan Spano, Cyndy Tanner, Esther Tseng

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS

Bill Curry, Audrey Derell, Eric Draper, Kevin Moloney, Peter Ogilvie, Daniel Quat, Robert Reck, Janet Russek, Kate Russell, David Scheinbaum, Lonnie Schlein, Nancy Sutor

REGIONAL SALES DIRECTOR

Mara Leader, 505-470-6442

ACCOUNT REPRESENTATIVES

Duncan Walker, 505-470-6442

Jaira Stewart, 505-470-6442

Anya Sebastian, 505-470-6442

NORTH AMERICAN DISTRIBUTION

Disticor Magazine Distribution Services, disticor.com

NEW MEXICO DISTRIBUTION

Ezra Leyba, 505-690-7791

ACCOUNTING AND SUBSCRIPTIONS

Patricia Moore

SOCIAL MEDIA MARKETING

Janna Lopez

PRINTING

Publication Printers

Denver, Colorado

Manufactured in the United States

Copyright 2023 by Santa Fe Trend LLC

All rights reserved. No part of Trend may be reproduced in any form without prior written consent from the publisher. For reprint information, please call 505-470-6442 or email santafetrend@gmail.com. Trend art+design+culture ISSN 2161-4229 is published online throughout the year and in print annually (20,000 copies), distributed throughout New Mexico and the US. To subscribe, visit trendmagazineglobal com/subscribe-renew. To receive a copy of the current issue in the US, mail a check for $17.99 to P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504-1951or go online to subscribe to the next issue at trendmagazineglobal.com/subscribe. Find us on Facebook at Trend art+design+culture magazine and Instagram @santafetrend

We’re seeking new and diverse voices! If you are a writer or photographer interested in contributing, please visit trendmagazineglobal.com/contribute and send your story pitches to santafetrend@gmail.com.

Trend, P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504-1951 505-470-6442, trendmagazineglobal.com

34 TREND art + design + culture 2023

EDITOR

After living abroad—Paris, Beijing, Rome, Armenia, Rwanda, and Vietnam for 20 years, working as a travel writer, editor, and teacher—I landed almost by accident in Las Vegas, New Mexico, about 60 miles northeast of Santa Fe. Little Las Vegas, I say, to distinguish it from the other one. It’s among the towns on the eastern flank of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains that suffered so terribly from last year’s Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak fire, which scorched 341,471 acres of some of the state’s most beautiful northern territory.

I taught writing at New Mexico Highlands University for a while and tried to open an ice cream shop near the Vegas Plaza, but nothing stuck until Trend ’s wonderful new photo editor, Lonnie Schlein, brought me to the magazine. We’re both New York Times alums. I launched the “Frugal Traveler” column before moving to the Los Angeles Times

I’m still learning Santa Fe, its culture and art. I’m still learning the hugely idiosyncratic state of New Mexico. But I must say I was encouraged when Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham, in some of the most beautiful cowgirl boots I’ve ever seen, stopped in Las Vegas during a Fourth of July parade last summer to pet my dog. Izzie is a little black Lab born on a ranch up in Cleveland.

My mandate at Trend, given to me by our publisher and fearless leader Cynthia Canyon, has been to seek out great, new writers to go along with the breathtaking photography in this issue.

Well, we found them. I’m proud to have New York Times National Correspondent Simon Romero, well-known feminist art writer Lucy R. Lippard, Santa Fe curator extraordinaire Stuart A. Ashman, and Southwestern art and architecture specialist Elmo Baca adding their distinctive voices to Trend. At the same time, I’ve been gratified to get to know and work with frequent Trend contributors like Peter Ogilvie, Cyndy Tanner, and Gussie Fauntleroy, not to mention talented magazine staff members.

When you put these writers and photographers together, you get a feast. You take in one photo essay—say Nancy Sutor’s luminous garden images or Peter Ogilvie’s striking nudes—and then must try another. It could be Kevin Moloney’s photographic ode to New Mexico or Eric Draper’s edgy, action-packed pictures of Albuquerque’s people. And then you must try another, and another.

Every one of these photo essays has been assembled with editorial care and pleasure. That is to say, my pleasure. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

—Susan Spano

FROM THE

35 trendmagazineglobal.com

Photo by Lonnie Schlein

After 40 years working as a photojournalist—mostly at The New York Time s—you’d think that I’d be ready to call it quits and move to a life of total relaxation. NOT!

Part of what drives me to keep going—aside from the sheer joy of looking at great photographs— is the satisfaction of being a part of a talented team, with everyone working toward the same goal. It was like that when I was part of the editorial team that won a 2002 Pulitzer Prize for a special Times section, A Nation Challenged, which covered the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks against the US. Later, the series was published as a book, crediting me as chief photo editor. It was a bestseller.

So, when publisher Cynthia Canyon, asked me to take on the prestigious position of photo editor for Trend magazine, I couldn’t say no. I wanted to be a part of a great team fulfilling a mission.

I certainly lucked out big time. What could be better for a photo editor than getting the chance to find multiple sensational photographers to shoot their own features, chiefly on New Mexico-related subjects. Each one would get a prodigious display of six to 12 pages. On top of that, Cynthia wanted me to contribute one of the photo essays. I could not imagine a more exciting assignment than working closely with them to produce stunning photo essays for an outstanding, elegant magazine.

My work for Trend is obviously now done. Working together with Cynthia, a woman of extraordinary vision, our very talented art director/designer Janine Lehmann, and our outstanding writer/editor Susan Spano (a New York Times alum) has been a very special experience for me. The magazine you’re holding in your hands reflects our various enterprises.

Throughout the process, I’ve so admired and have grown to like each and every one of the photographers represented in this issue. They are all professionals of the highest order, wonderfully talented and creative people: Peter Ogilvie, Robert Reck, Kate Russell, Audrey Derell, Eric Draper, Bill Curry, Kevin Moloney (who worked so very closely with me for years when I was the national photo editor of The Times), and the team of David Scheinbaum and Janet Russek (whom I’d known a lifetime ago and rediscovered working on Trend).

Through it all, I’ve made a bunch of round-trip driving excursions between the Dallas area and Santa Fe. And wow! I have grown to adore not only the state of New Mexico but also the city of Santa Fe. I now understand the extraordinary light of the area that so many photographers and artists have celebrated. No place in the United States bears any resemblance to this enchanting and beautiful world. There’s a great deal more learning ahead for me, but I am well on the way to a more complete understanding of what this place is really about.

Despite my total immersion in my work for Trend, I continue to be a political animal and news guy, preoccupied with the state of our world. Just as COVID-19 seemed to be winding down, Putin launched his outrageous genocide against the Ukrainian people. Tensions are growing between the US and China, and humanity’s pollution of our planet continues unabated. Fake news continues to spew forth its utter nonsense on social media, with Fox News leading the charge with anchors misleading the public about the results of the 2020 election, putting our democracy in jeopardy.

But truth matters! We still have a free press and some terrific magazines to peruse, like Trend. The magazine, which reflects the continued vibrancy of American art and culture, has more than survived through the most challenging of times for the print media. Many similar ventures throughout the country, especially in “artsy” towns, have closed shop. Next year Trend will celebrate its 25th anniversary and that’s quite an accomplishment. If you love art, design, and culture, Trend is certainly the place to go.

Cynthia has always believed in the value of print, and I agree. Although the magazine has an attractive website, it’s a pure delight to hold Trend in one’s hands, appreciating the very feel of it, the perceptible smell that comes from a stylishly produced journal. Even the ads—most of them from galleries and museums throughout the area—are a pleasure to look at.

So, my advice is simple: Get your hands on a copy of Trend and enjoy the pleasures contained therein.

Lonnie Schlein

FROM THE PHOTO EDITOR

36 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Lonnie Schlein in South Korea in November 2022 (photo by Oren Schlein).

In the last few years, I’ve been thinking a lot about legacy and what that means for me now that my son has grown and gone off to college.

I spent the last quarter of a century envisioning and creating a magazine that matters for my community. For me this meant learning about integrity in publishing, so crucial as the media evolves in these turbulent and confusing times.

Often it was against all odds that I learned how to publish in print, providing a level of excellence and beauty that few magazines can meet today. I never anticipated that print prices would double in 2022/23, forcing many magazines out of business. But tenacity and creativity have kept Trend going, regardless of the challenges.

This is a very special issue, as you will see, because I reached out to a photo editor, Lonnie Schlein, whose New York Times experience and expertise blew my mind. He, in turn, found longtime editor-writer, Susan Spano, who lives in Las Vegas, New Mexico, not far from Santa Fe. Their worldly perspective has taken Trend down new paths that you will appreciate in this issue.

I started on a life path in the arts through photography when I was in college. I had a very special photography teacher at Santa Monica City College near Los Angeles who had spent a lot of time taking pictures in Vietnam. He taught me how to feel, how to know from within what I was shooting, making it my own art. My final project for the class focused on laser light, which I shot at L.A.’s Griffith Observatory planetarium, replicating the look of nebulas and sacred geometrical shapes. I made it into a slideshow synced to the soundtrack of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. Patterns in science and nature have always moved me, as reflected in Trend magazine. I never imagined that the path I chose all those years ago would take me here publishing one of the best reads and magazines in the country in print, with Trend thriving, each issue better than ever.

— Cynthia Marie Canyon

Next year I will be celebrating 25 years in print with Trend. The 2024 issue will mark the occasion by reflecting back on the best stories we have published over the last 25 years. It will run more than 400 pages and be offered as a hardbound book. Looking back and celebrating the art+design+culture that is our legacy is as important as the work we do to find brand-new Trends to reflect each year.

To order a special first-print, hardbound copy of our June 2024 25th anniversary issue, and have it mailed to your home in the US, please send a check to Trend for $250.00 to P.O. Box 1951, Santa Fe, NM 87504.

LA MESA OF SANTA FE

FROM THE PUBLISHER

225 Canyon Road • Santa Fe NM 505-984-1688 • lamesaofsantafe.com

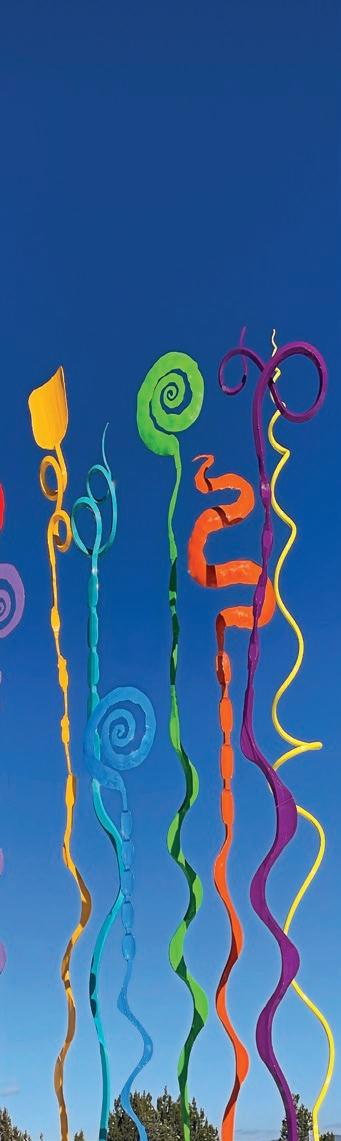

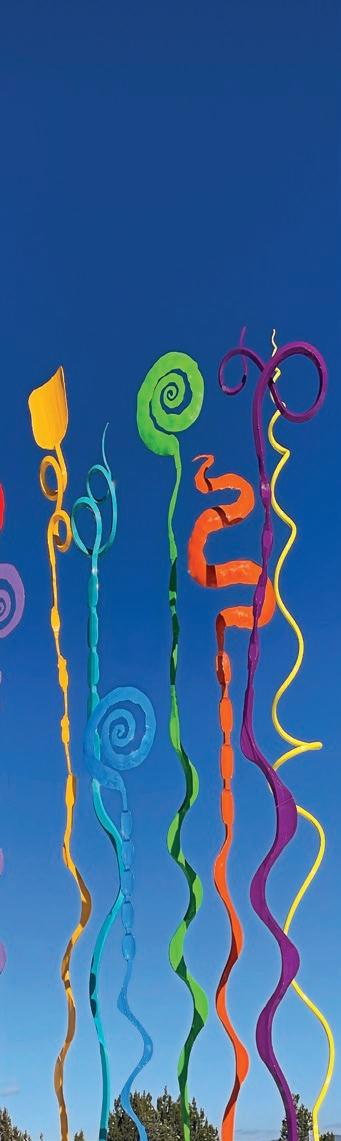

Christopher Thomson outdoor sculptures

Photo by Lonnie Schlein

37 trendmagazineglobal.com

CONTR IB UTORS

38 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Top, from left: Lucy R. Lippard (photo by Lonnie Schlein); Esther Tseng (photo by Linda Nguyen); Stuart A. Ashman (photo by Lonnie Schlein). Middle, from left: Simon Romero (photo by Eric Draper); Cyndy Tanner (photo by Kate Russell); Rose B. Simpson (photo by Kate Russell). Bottom, clockwise from left: Peter Ogilvie (photo by Bill Stengel); Vani Rangachar (photo by Barry Stavro); Audrey Derell (photo by Audrey Derell); Elmo Baca (photo by Lonnie Schlein); Kate Russell (photo by Kate Russell).

Stuart A. Ashman has long been part of the New Mexico arts scene as a photographer, museum director, and curator. He has coauthored books, like Abstract Art and Photography New Mexico, and was appointed Cabinet Secretary of the New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs in 2003. He grew up in Matanzas, Cuba, forging a lifelong interest in the Caribbean nation and its art. Last year he and his wife, Peggy, opened Artes de Cuba, a gallery on Lena Street in Santa Fe.

New Mexico-born Elmo Baca is a historic preservationist and author; his books include Rio Grande High Style and Santa Fe Design. He has served as program associate for New Mexico MainStreet, an organization that works to preserve historic townscapes throughout the state. In his hometown of Las Vegas, he restored a landmark 19th-century building near the plaza as a 50-seat, first-run movie theater. He is chairman of the Las Vegas New Mexico Community Foundation.

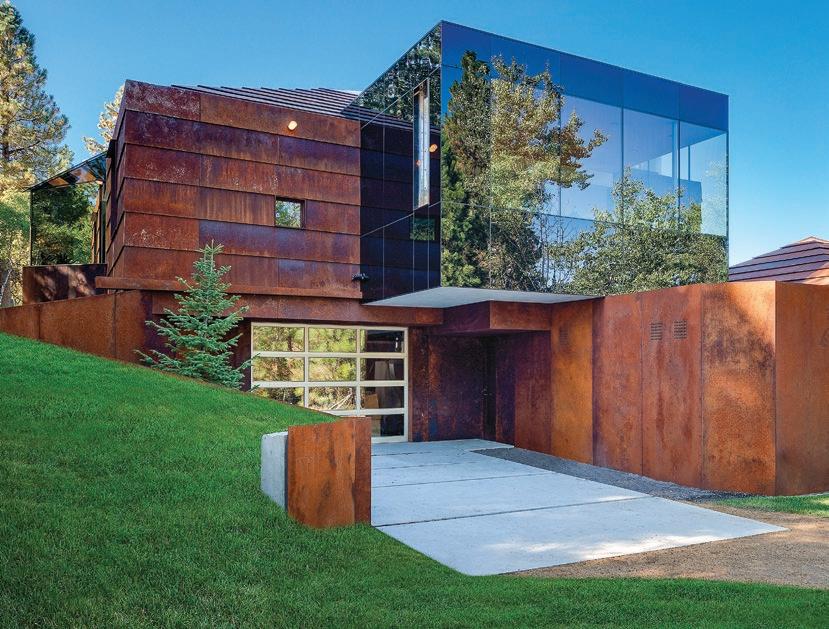

Audrey Derell’s lifelong journey in the arts began as a child in Finland. She lived and studied performing and visual arts in the Philippines, Belgium, France, Spain, and finally New Mexico. After a 20-year career in dance arts, Audrey transitioned into photography. Twelve years ago a pollenladen bee in the heart of a desert bloom captivated her mind and heart. Derell specializes in macro-botanical studies and dance imagery, and she enjoys meeting the fascinating artists whose portraits and oeuvre she captures for Trend magazine.

Lucy R. Lippard is a writer, activist, sometime curator, and author of 25 books on contemporary art activism, feminism, place, photography, and archaeology, most recently Undermining: A Wild Ride Through Land Use, Politics and Art in the Changing West, and Pueblo Chico; Land and Lives in the Village of Galisteo Since 1814. She is cofounder of several activist and feminist organizations, and lives off

the grid in Galisteo, New Mexico, where she has edited the monthly community newsletter for 26 years.

Raised in Southern California, Peter Ogilvie studied Art and Architecture at University of California at Berkeley, then pursued documentary filmmaking, and finally still photography, both fine art and fashion. “My passion for photography grew out of my love of looking at images,” he says. “Since I was a child, magazines and books full of pictures were magic worlds for me. I love capturing and creating those moments of the absurd and the divine that tell us the stories of who we are.”

Vani Rangachar, a longtime journalist, has written and edited many articles for leading US newspapers and publications on two coasts. She was deputy travel editor at the Los Angeles Times and most recently served as senior digital editor for Westways and AAA Explorer, magazines published for members of AAA. She serves on the board of directors for the Society of American Travel Writers (SATW) Foundation.

Simon Romero, born and raised in New Mexico, is a national correspondent for The New York Times, covering the Southwest. Based in Albuquerque, he travels widely to bring stories alive with on-the-ground reporting on issues, including energy politics, Indigenous sovereignty, the US-Mexico border, immigration, and climate change. Before joining The Times, he worked at Bloomberg News in Brazil, where he opened the news agency’s bureaus in Brasília and Rio de Janeiro. He is a recipient of the Maria Moors Cabot Prize for reporting on Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Robert Spiers Benjamin Award for best reporting in any medium in Latin America.

Kate Russell is a photographer based in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The subjects she

has covered are as varied as her background and include action, architecture, art, circus, fashion, food, friends, life, and travel. Kate also worked with New Mexico’s Meow Wolf as an artist, collaborator, photographer, and director of photography. Her photos define the Meow Wolf brand. Her work has been featured in Art Forum, New Mexico Magazine, Rolling Stone, The New York Times, and many others.

Rose B. Simpson is a mixed-media artist who lives and works in her ancestral homelands of the Santa Clara Pueblo, about 25 miles north of Santa Fe. She has degrees in art and creative writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts and in ceramics from the Rhode Island School of Design. Her work is held by the Denver Art Museum and New York’s Guggenheim Museum and has been exhibited at a host of museums and galleries, including Mass MoCA, the University of South Carolina School of Art and Design Museum, and the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe.

Cyndy Tanner is a Santa Fe-based freelance writer and co-owner of Parasol Productions, an events and photo styling company. Visual and verbal branding, book projects, and social media campaigns for clients keep her busy. Road trips, thrift stores, and mostly successful baking endeavors keep her happy.

Esther Tseng is a food, drinks, and culture writer based in Los Angeles, as well as a judge for the James Beard Foundation awards. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Bon Appétit, Food & Wine, and more. When not dining out, she enjoys snowboarding, Pilates, bike packing, and tending to her plot and leadership duties at her community garden. To unwind, she loves spending time at home with a book or streaming television accompanied by her cat, Chester. R

39 trendmagazineglobal.com

BY KATHRYN M DAVIS

At its inception, the New Mexico Museum of Art was a contemporary museum. Opened on the historic Santa Fe Plaza in 1917— long before such distinctions as “modern” and “contemporary” had specific meaning in the art world—the museum was intended to exhibit works by the new colony of artists living and working along Canyon Road.

More than 100 years later, a new moment in New Mexico’s artistic evolution is on the horizon and it has a new showcase. Slated for its grand opening in the summer of 2023, the Vladem Contemporary will focus on the contemporary side of New Mexico art. Dated roughly from the 1970s to the present, contemporary American art is distinguished by theorists from Modernism, which is typically seen as lasting from the mid-20th century to the 1960s and 1970s. By the 1980s, the art world was a different place, and the Vladem will reflect that.

Executive Director Mark White says that the New Mexico Museum of Art will

The Contemporary Side of Things

The New Mexico Museum of Art moves to include contemporary art in its focus by opening a new showcase at the super-cool Santa Fe Railyard

remain a singular institution, with dual campuses: the historic plaza site and the Vladem in the Railyard. Although each location’s exhibitions may be different visually, these paired establishments present a continuum of New Mexico’s significant trajectory within the history of American art.

The inaugural exhibition at the Vladem’s Railyard site will further that continuum. Shadow and Light focuses on New Mexico’s indefinable yet incredible light, which has attracted “artists and photographers to the region for decades,” as the museum’s assistant curator Katie Doyle says in her exhibition prospectus. She has selected artworks by such luminaries as Larry Bell and Ron Cooper of the Light and Space movement, renowned Earthworks artist Nancy Holt, installation superstar Yayoi Kusama, and Agnes Martin, whose deliberately quiet paintings are said to pulse with meaning.

Susan York is creating a graphite piece to be installed for the exhibition. Doyle has also chosen one of James Drake’s

most stunning video pieces, Tongue-Cut Sparrow. The exhibition will feature the striking Indigenous futurism of Cochiti Pueblo’s Virgil Ortiz, feminist icons Judy Chicago and Harmony Hammond, and self-described “culture witch” Erika Wanenmacher. In all, more than two dozen artists have been selected for this inaugural exhibition.

Designed by the architectural firm DNCA + Studio GP of Albuquerque and Santa Fe, the Vladem complex offers exhibition, storage, and education spaces, as well as a gift store on the Railyard side of Guadalupe Street. The new museum is named after Ellen and Robert Vladem, who made the lead contribution in a recent private-public fundraising campaign. (Steps from the Vladem, the Santa Fe Depot, the northernmost terminus for the Rail Runner commuter line, is receiving a facelift.)

A second entrance to the Vladem on Montezuma Street provides access to the spacious classrooms. Shadow and Light premieres in Gallery One on the

ART MATTERS

40 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Top, from left: Yayoi Kusama, Pumpkin, 2015 (courtesy of the Tia Foundation); Angela Ellsworth, Pantaloncini Double Untitled, 2019 (courtesy of the artist and Modern West Fine Art).

first floor, with nearly 5,000 square feet of exhibition space. Upstairs, Gallery Two comprises some 4,000 square feet of raw exposition space. An artist-inresidence area and 4,100 square feet of open storage allow visitors a perspective of the backstage functions of a contemporary museum.

With plenty of valuable wall space— not only necessary for exhibitions but also to keep the natural light from harming artworks on display—there is an abundance of our state’s celebrated light saturating the museum. Windows are thoughtfully situated, as are scrims.

And speaking of windows, the public will be able to see several of the Vladem’s ongoing installations during nonbusiness hours. The Windowbox Project on the northern side of the complex consists of an eight-foot-byeight-foot storefront window. Analogous to the Museum of Art’s previous—and well-attended—alcove shows, the Windowbox Project is designed to showcase regional artists, who will display their work quarterly. The museum is partnering with community-based Vital Spaces for the first year of window exhibitions.

Artists Cristina González and Morgan Barnard are scheduled for 2023.

A video window faces Guadalupe Street. The mural by Gilberto Guzmán that was on that side of the Halpin State Archives Building (formerly the Charles Ilfeld Company Warehouse) is to be permanently re-created by the artist inside the museum. Finally, always accessible to those who approach from the Railyard will be a light sculpture in the breezeway above the gift shop and the south entrance. At press time, artist Leo Villareal was completing the site-specific piece.

Together, the dual campuses of the Museum of Art will elevate the place of New Mexico in the narrative of American art. Santa Fe has long drawn visitors and residents, artists and their audiences alike. The Vladem will solidify New Mexico’s place in the art of today and our multicultural past as we look forward to an inclusive future. R

Hat Ranch Gallery is the most refreshing approach to acquiring art we have ever experienced Drive out to the beauty of the high desert, enter a home and learn about the artists, their methods and their subjects Don't miss the Hat Ranch Gallery ~ Marlene Elliot (Chicago , IL )

The most amazing experience we've ever had at a gallery The selection is wonderful and the customer service is over the top A MUST SEE when you're in Santa Fe

~ Sheri Autrey (Dallas , TX )

Hours: Thurs–Sun, 11 – 5 | 27 San Marcos Road W, Santa Fe, NM 505-424-3391 | hatranchgallery org | IG & FB @ hatranchgallery Private groups and appointments welcome

trendmagazineglobal.com 41

DANIEL QUAT PHOTOGRAPHY

S I LVER BULLET PRODUCTIONS

A not-for-profit gives Native American filmmakers a voice and prepares them for careers in a booming New Mexico industry

Native American sovereignty is a concept with deep individual and cultural significance. It entails autonomy, liberation, and recognition. Sovereignty for children, teachers, elders, tribal leaders, and community members is at the heart of Silver Bullet Productions, a not-for-profit educational film company.

For nearly 20 years, volunteer board members, tribal advisors, and unpaid staff from Silver Bullet Productions have worked alongside individuals from 20 of New Mexico’s Native American communities, teaching the art of storytelling through filmmaking. More than 55 documentaries have been completed, some nationally recognized and aired on PBS.

However Wide the Sky: Places of Powe r, which won a regional Emmy Award, explores the history and spirituality of Indigenous people and places of the American Southwest. It was directed by David Aubrey and written by Conroy Chino and Maura Dhu Studi. According to Silver Bullet, “The film transports viewers to Chaco Canyon, Bears Ears, Zuni Salt Lake, Mount Taylor, Santa Ana Pueblo, Taos Blue Lake, Mesa Prieta, and Santa Fe, and is narrated by Indigenous actress Tantoo Cardinal.”

Such Silver Bullet films are partnerships with Native American communities, creating invaluable

BY JANNA LOPEZ

BY JANNA LOPEZ

connections across generations. They share the uniqueness of each pueblo’s language, history, culture, and traditions, serving as archives of sovereign representation and truth.

The filmmaking is collaborative, taking as long as a year to complete, unifying leaders, teachers, elders, and children in the process. “Together, we decide the stories the community wants to explore and share,” says Pam Pierce, a lawyer, former teacher and charter school director, and cofounder of Silver Bullet Productions. “The intention is to preserve the voices of each tribe’s elders, illuminate a depth of heritage most people don’t know, and braid together unique languages, art, the beauty of the land, and teachings.”

Once a connection has been made between a community and Silver Bullet Productions, conversations about film projects begin, with students, teachers, and tribal leaders involved the entire time. Participants are asked: What question do you want your film to answer? Which stories do you want to tell? How will you approach historical complexities? And how will you best honor your culture?

Silver Bullet Productions provides the equipment and hands-on learning which give students professional career skills and opportunities for expression. They also get access to industry stars like Wes Studi, Maura Dhu Studi, Chris Eyre, and many other Native American film directors, producers, actors, and screenwriters.

FILM

42 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Silver Bullet Productions offers students from Indigenous communities yearlong educational and creative filmmaking opportunities. Equipment and professional industry guidance support communitywide project collaboration (photos courtesy of Silver Bullet Productions).

Film professionals commit to mentoring each community’s new filmmakers for a year.

“Silver Bullet Productions uses filmmaking to educate and spark discussion about culture and place,” director Eyre says. “Their teaching and documentaries help to grow Native American filmmaking and provide an avenue for authentic Native voices and storytelling.”

Adding to the authenticity are each project’s unpaid cultural advisors. Matthew Martinez, PhD, has been a board member and film project advisor for 12 years. He is a member of the Ohkay Owingeh tribe, a former New Mexico lieutenant governor, and past director at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture.

“Advisors are a critical piece to our projects,” Martinez says. “We rely on community educators, scholars, and tribal leaders to provide input in the development process of our documentaries. Advisors are key to helping set up site locations and identifying graphics, music, and other voices that help convey a narrative.” With great sensitivity, they guide the themes of

documentaries, which include such topics as the inherent power of Indigenous women, the warrior in past and modern times, tribal leadership, and sovereignty. “Silver Bullet Productions will not include footage or recordings that cross cultural boundaries or may be perceived as questionable,” Martinez says.

Looking ahead, Silver Bullet Productions plans to raise awareness and needed funds to engage smaller, more rural communities in educational, student-centric, collaborative films across New Mexico. Each project includes classroom discussion guides related to culture and thoughtful representation. Workshops are immersive and include panel discussions in which the whole community participates.

Silver Bullet Productions wants to guide a rapidly accelerating New Mexico film industry in a way that is inclusive and honors and sustains Indigenous cultures. Its mandate is to give the power of voice to Native American people so that they can tell their own stories in ways that protect and preserve their sacred cultures and lands. R

tierramargallery.com 225 Canyon Rd, Santa Fe, NM 505.372.7087 JARRETT WEST SCULPTURES 43 trendmagazineglobal.com

Director Chris Eyre, actor Zahn Tokiya-ku McClarnon, and Pueblo of Zuni Tribal Council members attend Silver Bullet Productions annual fundraiser (photos by Janna Lopez).

COMING SOON Autumn 2023 $449,900 - $489,900 STUDIOS AT PARKWAY studiosatparkway.com 1189 Parkway Drive palosantodesigns.com 505-988-7230 Giorgetti Real Estate Leslie Giorgetti Owner / Broker 505-670-7578 Commercial Condos, 1490 sf, Rufina and Siler FOR SALE OR LEASE DISTINCTIVE SPACES FOR WORK AND PLAY in Santa Fe’s Creative Center & Opportunity Zone

Trevor Mikula

Travis Bruce Black

Trevor Mikula

Travis Bruce Black

New Brow Contemporary Art 125 Lincoln Avenue Santa Fe, NM www.popsantafe.com 505.820.0788

Judy Shreve

SAMUEL DESIGN GROUP

LIVABLE. MODERN. LUXURY

WENDY MCEAHERN (3) 46 TREND art + design + culture 2023

ADVERTISEMENT 47 trendmagazineglobal.com

Stunningly seamless integration of space, light, and heart is a trademark differentiator of designer Lisa Samuel. Her company is founded on this premise. At its core, integration is an aim for inhabited spaces to elevate our life experiences. Samuel, president of Samuel Design Group in Santa Fe, utilizes credentials in design, architecture, and construction to extend imagination into internationally award-winning design projects; projects that promote life-enhancing power.

Samuel is proud to introduce the talents of Clayton Brandt, architect and interior designer, as her partner.

The Samuel team shares this express belief: “The design of spaces we occupy can have profound ‘life-enhancing’ power when the project is approached from a reverent heart space where everyone involved in the project is treated with kindness and respect.” This factor is essential to the collective philosophy of Samuel Design Group.

48 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Designing interiors and exteriors of homes is where Samuel believes the environment can truly be seen, felt, and expressed. She says, “Our home environment is, and has been, the foundation for a healthy life. The aesthetic beauty can positively enhance our living and supply us with a foundation for health. One’s home should be a space that encourages the best version of yourself. Even the most beautifully appointed room is truly empty unless the intrinsic energy and personal meaning is graciously curated.”

Samuel believes that healthy business environments are equally essential. Commercial lighting and interior design projects integrate every passionate detail for luxury hotels, resorts, galleries, and restaurants. Samuel shares, “Design expresses everything a business values: your products, employees, culture, and your customers. We can turn any room into a statement piece to convey the unique heart of your

brand. Fabrics, furnishings, and finishes are selected to express your business’s unique identity. Every element has a purpose related to your company’s essence.”

Design of aesthetically nourishing environments has earned Samuel the highest accolades. Samuel has won local, national, and international awards, including the prestigious International Property Award for Best Interior Design of a Private Residence, “Best of Houzz” for Design, and Customer Satisfaction by Houzz, the leading platform for home remodeling and design.

Samuel concludes by sharing, “When does a house become a home? When does any space envelop you and make you feel good? Is it designed to soothe? Many say that a house is made by hands but a home is made by the heart. In my experience, a space can only become a home when the owners’ personality and heart have been considered in each and every element I design.”

49 trendmagazineglobal.com Santa Fe | 505-820-0239 | samueldesigngroup.com

ADVERTISEMENT

My New Mexico

A photographer digs deep into his archives for images that stir memories of a place he can’t forge t BY

KEVIN MOLONEY

In late January 1998 I stood enchanted, photographing the setting sun’s glow on the modest, weather-beaten monument atop the ruin mounds of San Gabriel de Yunque-Ouinge. That year marked an important anniversary; it had been 400 years since more than a dozen of my soldier-colonist ancestors and their families took over the homes of the Tewa people who lived in this small pueblo. It crouches just across the Río Grande from Ohkay Owingeh, called San Juan de los Caballeros by the Spanish who arrived there in 1598. Throughout that anniversary year I photographed one site after another where my family disrupted the Indigenous world with war, taxation, and disease until they fused with it through intermarriage and collective struggle.

My family is a mix of wanderers, explorers, and refugees who all found themselves in what was long the most remote outpost in North America of any government that claimed it. With names like Márquez, Pérez de Bustillo, Robledo, and Baca, they pushed in with Spanish conquistador Juan de Oñate, became Mexican citizens in 1821, and then Americans in 1848. Their children married into wandering, exploring, refugee Irish and German families. My greatgreat grandfathers founded San Luis, the oldest town in Colorado. To them the state line was just a bureaucratic imposition across which culture and family flowed as unimpeded as the waters of the Río Grande. When I am asked where I am from, I reply that I was born in Colorado. But really, because of my long, deep roots here, I am of New Mexico.

To be of New Mexico is to have a very long memory. Those memories come from a heart swelling with pride or sometimes a stomach knotted with grudge. Like most things in a desert, they last forever. If, as photographer Minor White once wrote, all photo -

graphs are ultimately self-portraits, my New Mexico images are memories that connect my lifetime to a cascade of others—they inhabit my bones. To be of New Mexico is to know that anything that happened in the last 200 years, even the invention of photography, is recent news.

To be of New Mexico is to know that architecture is inhabited by the land rather than simply built atop it. Whether it is the 1,000-year-old Taos Pueblo, Santa Fe’s cherished 1610 chapel of San Miguel, or Mexican modernist Ricardo Legorreta’s Santa Fe Art Institute, valued structures here fuse with the landscape so fundamentally that they could only be replicated soullessly elsewhere. In other cities glass towers and particle-board tract houses sit temporarily atop the ground, waiting to be scraped off by environmental or developmental disasters. To be of New Mexico means that no matter where you live, you long for a home that is cradled by the land.

To be of New Mexico is to have a religion, no matter what that might be. Among those soldier-colonists of 1598 were zealous treasure seekers, dogmatic conquerors, pilgrim refugees of European caste systems, secretive crypto-Jews fleeing the Inquisition, and a handful of Franciscan friars hoping to convert by charm or force the Indigenous people who, despite those efforts, held onto important traditions. From those friars and the self-punishing Penitentes they inspired to ashrams, Sikh enclaves, and Latino Pentecostals, mystical religions abound here. Many of us also find belief and meaning outside established religion, as I have in the vocation of journalism or the priesthood of teaching.

My father, who had the heart and imagination of a mystic, carried that fervor to his own work as a photojournalist and a teacher. His love of land, image, and ritual attracted me irresistibly while I traveled

50 TREND art + design + culture 2023

51 trendmagazineglobal.com

A cross-carrying pilgrim wears a Virgin de Guadalupe rosary enroute to the Santuario de Chimayó in Northern New Mexico on Good Friday. Thousands make a pilgrimage to the 200-year-old shrine every Easter.

52 TREND art + design + culture 2023

The iconic 1878 spiral staircase at the Loretto Chapel in Santa Fe offered elegant access to the choir loft 22 feet above.

with him as a child, making pictures of New Mexico and the West. No matter the mythology or mode, to be of New Mexico is to believe in something passionately and selfsacrificially.

To be of New Mexico is also to understand that eventually your culture will be changed by collision or conflict with another. From prehistoric Clovis people to Ancestral Puebloans, Navajo, Pueblo, and Apache, Indigenous people have arrived, colonized, created, and dissipated here for millennia. They conflicted with ever-larger bands of Europeans, from Spaniards in 1598 and 1692 to blue-coated American soldiers in 1846.

Those soldiers opened routes to St. Louis on the far Mississippi River that my merchant great-great grandfather Dario Gallegos traveled. As a young man he joined the Santa Fe Trail trade and made commercial connections on the other side of the Plains that he later used to stock a mercantile store—still in business—in San Luis. Those wagon

A caretaker sweeps the nave at the Santuario de Chimayó, a revered Catholic pilgrimage site near the Santa Cruz River about 25 miles north of Santa Fe.

Right: George Chavez scrapes wax from the candleholders at the church built by his family. He died in 1989.

53 trendmagazineglobal.com

54 TREND art + design + culture 2023

A full moon rises over the 400-year-old plaza in Santa Fe and its distinctive and controversial Soldiers Monument obelisk.

55 trendmagazineglobal.com

Fragments, shadow art by Kumi Yamashita, at the New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe.

56 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Tourists at the Oñate Center in Alcade, New Mexico, with a statue of the Juan de Oñate. Its foot was sawed off to protest atrocities against Indigenous people committed by the Spanish. Top: Ohkay Owingeh Puebloans watch a 1998 parade celebrating the 400th anniversary of the 1598 Spanish invasion.

57 trendmagazineglobal.com

Clockwise, from top: Artist Golda Blaise Pickett works on a piece during an art throwdown at Meow Wolf, a Santa Fe center for immersive, interactive art; cinnamon rolls are loaded into a wood-fired horno oven at the historic Acoma Pueblo; acclaimed chef Martin Rios (center) puts the finishing touches on a dish in the kitchen of Restaurant Martin in Santa Fe.

58 TREND art + design + culture 2023

59 trendmagazineglobal.com

An Apache woman walks the ruins at Gran Quivira, part of the Salinas Pueblo Missions National Monument in central New Mexico. By 1678, the once-thriving Native American community was abandoned due to Spanish hostility, epidemics, and Apache raids.

60 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Young Native Americans stretch before sprinting up a desert hill near the Navajo Nation town of Shiprock, New Mexico. Top: An Acoma man at the Mission of San Estevan del Rey on the Acoma Pueblo, which sits atop a 400-foot-tall New Mexico mesa. The pueblo was leveled by Spanish troops in 1598.

trains, then the Santa Fe Railroad and Route 66, brought rare goods, new ideas, and eventually artists and writers seeking distant inspiration. They changed Taos, Abiquiu, and Santa Fe in their wake. To be of New Mexico is to know that more collisions will come, and that Santa Fe will again and again become a “city different.”

To be of New Mexico is to savor each meal as if it is your last. The high desert surrenders little surplus. Until the railroads changed the economics of supply, privation or starvation were only a dry or freezing season away. Here food is celebration, food is art, food is love. Traditional local dishes abound in the terroir of difficulty: earthy, complex, sharp, piquant, and bitter. My Nana’s Depression-era recipe for posole—our Christmas Eve staple still—embodies all of this through only six ingredients: dry hominy and red chiles from Fernandez Chile Company in Alamosa, garlic, oregano, salt, and a lamb or mutton shank simmered atop a stove all day. When local dishes are sweet—natillas, atoles, buñuelos—that sweetness is subtle, as if it is hard-won, and travels in the company of bitterness from cinnamon or anise. To be of New Mexico is to know that your food tells a fraught, complex story.

And yet anyone who considers themselves of a place would argue all these same things. The 1863 bricks of my current home in Indiana were kilned on site from local clay

and its foundation stones were cut from the bedrock strata below. The river that winds past is a stream of long history, change, and conflict. People here are as passionate in their beliefs as my New Mexican family is.

Why, then, is New Mexico different? If you are reading this in Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Abiquiu, Las Cruces, or even across that random and imperceptible bureaucratic line in San Luis, you know that it looks, breathes, and feels different. The air and sun feel as unique as a cool summer evening and as memorable as the incense of a piñon fire. It sneaks up on you like the warm, delicately acrid palate glow of good red chile.

As I write this, I search for the word that describes how New Mexicans, whether transplants or natives, feel about this place. In my photographs I see it in the sharp light of the Jornada del Muerto, the warm colors on the walls of Laguna Pueblo, the open skies above the ruins at Salinas, the dark and miraculous nave at Chimayó, and the ghosts of hundreds of generations who called this home. Is it complexity? Contradiction? Continuity? Many other places can argue the same.

I keep returning to a description of this place coined in 1906 by journalist Lilian Whiting. After a bit of nostalgic, familial, heart-filling consideration, I argue it all comes down to this: To be of New Mexico is to be enchanted. R

Kevin Moloney, longtime photojournalist for The New York Times, now teaches media design and development at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana (photo by Sami Hensley).

Left: Casilda Salazar Moloney, “Nana,” on Christmas Day 1959 (photo by Paul F. Moloney).

Kevin Moloney, longtime photojournalist for The New York Times, now teaches media design and development at Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana (photo by Sami Hensley).

Left: Casilda Salazar Moloney, “Nana,” on Christmas Day 1959 (photo by Paul F. Moloney).

61 trendmagazineglobal.com

Changing Woman Between Worlds, Virginia Maria Romero, acrylic on

canvas, 48” x 60”

613 Canyon Road Santa Fe, NM 87501 billhester@billhesterfineart.com

Portrait of David Bowie, James Paul Brown, mixed media on paper, 44” x 30”

Eternal Portals, Susanna Hester, oil on canvas, 18”

A Magical Place Bill Hester Fine Art BillHesterFineArt.com (505) 660-5966 Red Fat Happy, Barrett DeBusk, 4’ and 5’ and 28” tall, powder coated steel

x 24”

YENNY COCQ SCULPTURE

The love that lifelong artist Yenny Cocq pours into her creations has touched collectors all over the world. Through bronze sculptures and stunning elegant jewelry, Yenny expresses ever-evolving connections to family through love. She shares, “Love forms my creations—from my heart through my hands and work—to the embodiment of my sculpture.” Yenny has been internationally recognized for her pieces and has a huge fan base in Europe, where she once had a gallery in Copenhagen. Today, Santa Fe is her home. Yenny states, “It’s important to be connected to my local customers and community. People are always invited and encouraged to visit my Santa Fe studio.” Over the years her work has morphed and as she notes, “Although it’s become larger and wider, the essence of family connections remains the same. It begins with a single figure and then, as times change and relationships grow, perhaps the individual piece gets coupled, or a pet is added, or perhaps children. My work is meant to reflect the nature of people’s families and love.”

64 TREND art + design + culture 2023

yennycocqsculpture.com | 131 County Road 84, Santa Fe, NM | 505-670-6053

ADVERTISEMENT

In the studio male bronze before patina, 56”; The Two of Us, life-size bronze sculpture couple for outdoors, 56”; The Two of Us, bronze in private collection, 56” TOP THREE PHOTOS: YENNY COCQ; BOTTOM RIGHT PHOTO: KRISTINA KORSHOLM

Tim Wiford’s passion for art, enthusiasm for starting companies, and love for selling inspired the creation of the Wiford Gallery. Everything came together as an experiment to test an economic model based on giving expression to meaningful service; in this case giving heart, mind, soul, and strength to the placement of beauty in the world. “I have always believed that art is an emissary to a better world,” he says.

The formula has succeeded because the Canyon Road gallery, founded more than 20 years ago, is still strong today. The artists represented—currently there are five—have all done something of extraordinary value that sets them apart in the art world.

More than 40 years ago, Lyman Whitaker was the originator of Wind Sculptures™ and Wind Forests™, and is probably the most prominent kinetic artist in the world today. Tim Church has created his own genre called vibrant toning on copper. Trained as a scientist and researcher, he has devoted nearly 20 years of time and effort into researching his unique artistic process, working with acids, bases, and temperatures pushing materials to their limits, creating beautiful art from science. Jeremiah Welsh is the finest low-relief sculptor of his generation and can work in any format, style, or size. Rod Hubble is an exceptional painter who has mastered his genre and inspired people for more than 50 years. Finally, Ryan Steffen’s atmospheric stone sculpture infinity fountains contribute beauty and context to any space, inside or outside.

65 trendmagazineglobal.com WIFORD GALLERY wifordgallery.com | 403 Canyon Road, Santa Fe, NM | 505-577-0888

ADVERTISEMENT

Small Wind Forest™ by Lyman Whitaker, copper and stainless steel wind sculptures™

WIFORD GALLERY

In addition to representing these original living artists, Wiford Gallery also provides a service for collectors interested in acquiring or selling historical works of art. “Not everyone wants to go through the process of getting involved or continuing with art auctions,” explains Wiford. “So we work on their behalf to find what they are looking for and match sellers with suitable buyers.”

Wiford’s passion for art has clearly not diminished one iota since he started the gallery back in 2002. “Putting beautiful art into the world satisfies an essential part of my soul,” he says. “It is our honor to serve our exceptional artists, our collectors whose support of the arts energizes and expands that process, and our team members who connect all the parts that make the existence of Wiford Gallery possible.”

Spring Arabesque by Rod Hubble, oil on linen, 12” x 12”

Spring Arabesque by Rod Hubble, oil on linen, 12” x 12”

66 TREND art + design + culture 2023

ADVERTISEMENT

67

Clockwise from top left: Sunrise Duo by Ryan Steffens, infinity fountains; Teton Pair by JD Welsh, low relief bronze, 9” x 6”; Daybreak by Tim Church, vibrant toning on copper, 72” x 38”

Snowstorm over Sangre de Cristo Mountains 2020, Analog Capture on Film, Silver Halide Print on Dibond, 72" by 24"

Below: Cloud Panel 2022, Analog Capture on Film, Silver Halide Print on Dibond, 140" by 70"

Snowstorm over Sangre de Cristo Mountains 2020, Analog Capture on Film, Silver Halide Print on Dibond, 72" by 24"

Below: Cloud Panel 2022, Analog Capture on Film, Silver Halide Print on Dibond, 140" by 70"

ANALOG CAPTURE

Gerd J. Kunde has a long history of deeply exploring artistic pursuits. His interest in photography began at a young age. Growing up in Germany, he taught himself studio and street photography. He spent hours every day taking photographs and making prints in his own darkroom, and won a local photo competition at the age of 18. He went on to study physics and came to the US to pursue a career as a scientist when he was 29. After 20 years in the Southwest, science and art finally came together when he rediscovered the deliberate, detailed art of large-format analog photography.

In his artist statement he quotes photographer Aaron Siskind, who wrote in 1945 that while we see in terms of our experience, photographers must learn to relax those beliefs and capture an emotional experience. “No one else can ever see quite what you have seen,” Siskind penned, “and the picture that emerges is unique, never before made, and never to be repeated.”

Unlike digital images, which are flat and quantized, Kunde captures on analog, traditional film and his use of archival printing processes draws people in and makes his large-scale reproduc-

tions come alive. “I want people to have the same experience I had, being in that place,” he says. “I want them to see what I see and really feel they are part of the scene they are looking at.”

His archival prints are created by hand in the platinum-palladium process (up to 20 inches on Arches paper, an unusually large size for this technique) or laser-scribed on silver halide paper for larger prints. The photographs, all limited editions of 10, can be sized to fit a particular location—the largest reproduction so far has been 8 feet wide.

Moving beyond traditional presentations, Kunde offers what he calls “site-specific art,” working with a client’s expectations and spaces—creating paneled pieces. He invites visits to his studio and gallery in Tesuque, New Mexico. Seeing a photograph or photographic panel by walking 6 to 12 feet from side to side is a unique experience, and reflects the unique aspects of the analog techniques Kunde has mastered.

The large-scale images of boundless vistas extend the space, acting like a window to the sky. “My goal as a scientist is to transcend my training,” Kunde says, “and to touch people emotionally with my black-and-white photography.”

ADVERTISEMENT analog-capture.com | 505-920-9424 | info@analog-capture.com ADVERTISEMENT

69 trendmagazineglobal.com

antiques 608 canyon road, santa fe, nm 87501 (505) 982-8019

claiborne gallery

SWAT VALLEY, CARVED WOOD PANELS, 87” X 22”

SOMERS RANDOLPH

Somers Randolph has been actively pursuing form for most of his life. “I started carving wood, and then stone, in high school,” he recalls, “I was completely captivated by it. I decided at 15 years old that I would be a sculptor. There are magic moments when I can truly ‘see’ a form and they’ve provided the energy for a lifetime of carving.” Fifty years later, Randolph’s pieces are owned by notable collectors worldwide.

Now 67, Randolph creates his one-of-a-kind sculptures in stone from every continent. Marble, granite, alabaster, onyx, and even lapis have yielded unique shapes, with personalities that shift and change as they interact with light. Light bounces off the surface of an opaque sculpture, highlighting and drawing out hidden details, but penetrates deeply into translucent material, making the work glow and come alive. “I try to make each piece perfect in relationship with itself. Balance, proportion, weight, motion, and silhouette are a complicated set of conditions to arrange in a way that they coexist effortlessly,” says Randolph, “My pieces continue to become simpler, more complete, more statement than question.”

If you’re interested in sculpture, you are invited to visit Randolph’s home gallery and studio, just a mileand-a-half from the historic Santa Fe Plaza. Complimentary personal studio tours are available by appointment. Text him at 505-690-9097 or email sculptr@aol.com to introduce yourself and to check availability.

somersrandolph.com | Santa Fe, NM | sculptr@aol.com

ADVERTISEMENT 71 trendmagazineglobal.com

Somers Randolph in his Santa Fe studio

SOMERS RANDOLPH

MCEAHERN

72 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Green Durango calcite, 12” tall

WENDY

(4)

ADVERTISEMENT

73 trendmagazineglobal.com

Clockwise, from left: Turkish marble, 22” tall; Green Durango calcite, 12” tall; orange Utah alabaster, 11” tall; and orange Hannah calcite, 16” tall; Randolph works with a wide range of stone, including (from left) New Mexican marble, green Durango calcite, white Italian alabaster, orange Utah alabaster, and orange Hannah calcite.

PRESCOTT GALLERY and SCULPTURE GARDEN

Fredrick Prescott’s larger-than-life, brightly colored, solid-steel sculptures are truly one of a kind. Engineered to move in the wind or activated by hand, they combine reality with fantasy in an ever-evolving variety of magical images. There are 30-foot-high giraffes alongside pink flamingos, elephants, seahorses, dinosaurs, dragons, and many other real and imaginary creatures.

Everything is created in a 30,000-square-feet studio in Santa Fe. The process is inevitably complex, starting with a drawing transferred to a computer and then on to a machine that cuts sections in steel. The pieces are then powder coated with a spray gun, sandblasted, and then fired in a massive oven that heats the environmentally friendly powder paint up to 500 degrees, melting it into a glossy finish. A final

clear coat protects the work from the weather if it is to be displayed outdoors.

The enormous works are transported all over the country, strapped down on a huge trailer hooked onto a big truck, to be exhibited in museums, public parks, schools, galleries, and private homes. Prescott is also open to commissions and over the years has completed many, including some for celebrities such as Michael Jordan and Steven Spielberg.

The gallery on Agua Fria Street is currently showing a retrospective, with photographs and early works that demonstrate Prescott’s artistic evolution over the years. One may wonder: After a career that spans more than 50 years, has he ever run out of ideas? “Never,” he says. “The problem is too many ideas and not enough time.”

prescottstudio.com | 1127 Siler Park Ln, Santa Fe, NM 87505 | 505-424-8449

TOP:

74 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Prescott kinetic sculptures on safari Opposite left: Free Range Elk, kinetic sculpture, 8’ tall Opposite right: Rockin’ Rooster, kinetic sculpture, 10’ tall

GABRIELLA MARKS PHOTOGRAPHY

ADVERTISEMENT 75 trendmagazineglobal.com

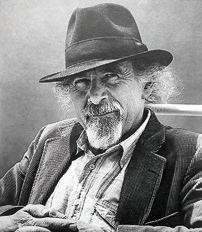

Alvaro Cardona-Hine, a self-taught painter, poet, and musician, was born in Costa Rica and came to the U.S. when he was 13 years old. Later in his life, he settled in Truchas, New Mexico, to devote himself to painting fulltime. He was one of the first artists to bypass the gallery system and represent his own work, opening the Cardona-Hine Gallery in 1988.

Many tourists and art enthusiasts travel through the village of Truchas on their way from Santa Fe to Taos. They come not only to enjoy the wonderful views but also to explore the workshops and studios of artists and artisans along the way. Cardona-Hine’s gallery flourished for almost 30 years until he finally passed in 2016.

A prolific artist, Cardona-Hine painted every day. His works differ widely in style and subject matter, ranging from birds and landscapes to brightly colored abstracts. His determination to remain free, with no recognizable format, is another reason why he opted out of galleries.

His remaining paintings are now in the possession of his daughter, Elena, who is finding homes for the last few hundred. “They really need to be seen, to be hung on walls, and enjoyed,” she says.

Consequently, she has put together an online gallery, cardona-hinegallery.com, so that people can see, enjoy, and purchase her father’s works of art. Sizes, prices, and subject matter vary enormously, so there should be something for everyone. And, as the artist said, “How sad a wall without a painting!”

cardona-hinegallery.com | 505-629-9241 | cardonahinegallery2023@gmail.com

ALVARO CARDONA-HINE

Clockwise, from top left: Bull Totem, acrylic on canvas, 78” x 50”

76 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Alvaro Cardona-Hine portrait Castles in the Air II , oil on acrylic on canvas, 76” x 54”

ADVERTISEMENT

77 trendmagazineglobal.com

Moroccan Evening, acrylic on canvas, 37” x 54”

Worldly

Been everywhere, knows everyone, can pull off anything. Lonnie Schlein, master New York Times photographer-photo editor, shows his stuff.

BY SUSAN SPANO | PHOTOGRAPHY BY LONNIE SCHLEIN

BY SUSAN SPANO | PHOTOGRAPHY BY LONNIE SCHLEIN

Most of us are deeply compelled—and sometimes fundamentally changed—by the work of photojournalists. Take, for instance, the indelible 1972 picture by AP photographer Nick Ut of a naked child running down a road in Vietnam after a napalm attack. The people who take such photographs roam the world seeking a way to visually express complicated political, moral, and emotional issues. And the right moment—or second—to photograph them. Some do it by instinct. For others, like Lonnie Schlein, getting the most vivid and meaningful shot comes from deep knowledge and broad experience.

Schlein has spent a lifetime looking at photos and shooting them. As a photo editor for some 35 years at The New York Times, he was assigned to the Metro Desk the morning of September 11, 2001, when his editor called him in to the office ASAP. But first he ran to the rooftop of his Midtown Manhattan apartment to capture some of the most achingly tragic images of smoke pluming above the World Trade

Center towers before they fell. With Schlein as photo editor, the paper’s 9/11 coverage won a Pulitzer Prize.

The Times was a lodestar even when he was young. “It was always around the house. I clipped and saved headlines. I have my own archives,” he says. Schlein was born and raised in the Flatbush neighborhood of Brooklyn. He got his first camera, a twin-lens Argoflex, around 1956. At the time, his Uncle Izzy was director of photography at CBS and, as a teenager, Schlein rode the subway from the far reaches of Brooklyn to the television studios in Manhattan, where he hung around the photo lab watching the pre-digital age techs “doing magic,” as he says.

After college, he started at The Times as a copy boy, running across West 43rd Street for cigarettes and coffee at the behest of editors and columnists. As he became one of the paper’s most respected photo editors, he made sure he could keep taking pictures, too. He traveled around the world with a camera. The more he saw, the more he knew.

Sometimes the image would fall in his lap. Right place, right time, as when he shot an ice climber dangling pre -

78 TREND art + design + culture 2023

cariously from a rope in Ouray, Colorado. Or his just-born daughter emerging into the world halfway between womb and obstetrician’s hands. Or the look of indescribable joy on the face of a young Black woman when Barack Obama accepted the nomination for president at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. Schlein always gives luck its due. Nevertheless, he says, “You must not shoot wildly. Wait for the right moment.”

When you look closely at some of his most powerful images, you see that something more than right-place-right-time is operating. You’ll see a studiousness and informed eye for composition in his photo of a Havana cigar factory worker with a dogeared photo of Che Guevara propped up in the background. The same intensity marks his shot of two boys on a stoop in Ghana who had just escaped from two years of slavery on fishing boats. He couldn’t get them to look at him or into the camera. “They had these empty expressions,” Schlein says. “They were totally destroyed.”

Schlein remembers the decade he was The Times national photo editor as the most exciting time in his tenure at the paper. He convinced Coretta Scott King to let the newspaper use a never-before-seen portrait of the King family and arranged exclusive Times photo ops of then-President Clinton. Getting reluctant subjects to allow photographers to take their pictures became his forte. “Just ask Lonnie,” coworkers would say. “Lonnie can pull it off.”

The story of how he got the last portrait session with John Lennon and Yoko Ono on November 3, 1980—just a month before Lennon’s fatal shooting on December 8, 1980—has passed into Times lore. The famously secretive couple had repeatedly refused the paper’s requests.

Finally, Schlein contacted Yoko and convinced her and John to sit for the portraits, though the paper had to break a cardinal rule and give them photo approval. Moreover, the shoot had to take place at 3 a.m. and only photographer Jack Mitchell was allowed in the studio. When Mitchell finished the contact sheets, Lonnie took them in a cab to The Dakota, where Yoko painstakingly selected 10 shots that she and John agreed the paper could publish. Around 5 a.m. Schlein’s wife, Monique, called. Yoko answered. “I’m sorry I kept your husband so long. He’s on his way home now.”

Photojournalist? Photo editor? Manipulator? Cajoler? There is simply no way of pigeonholing Lonnie Schlein. Never mind. When we look at his images, we see the world recorded by a photographer who has been everywhere, done everything, and seen it all. R

At a market high in the Peruvian Andes about 20 miles north of Cusco, Chinchero village women prepare feasts for visitors.

Top: A street-food chef grills mouthwatering beef and chicken skewers in the red-hot shopping and entertainment district of Myeong-dong in Seoul, South Korea.

At a market high in the Peruvian Andes about 20 miles north of Cusco, Chinchero village women prepare feasts for visitors.

Top: A street-food chef grills mouthwatering beef and chicken skewers in the red-hot shopping and entertainment district of Myeong-dong in Seoul, South Korea.

79 trendmagazineglobal.com

Opposite: The Spanish Coffee Shop and Bookstore on Solny Square in Wroclaw, Poland.

80 TREND art + design + culture 2023

In tiny Oakland Valley, New York, about two hours northwest of New York City, a woman on the banks of the Neversink River takes in the fog and sound of the rushing waters.

81 trendmagazineglobal.com

A visitor takes a break on a visit to Seoul’s ornate Gyeongbokgung Palace, built in 1395 for the Joseon Dynasty, which ruled Korea for more than 500 years.

82 TREND art + design + culture 2023

On a summer day in Copenhagen, a crowd gathers at Nyhavn Harbor to soak up the sun.

Brothers Joe, 10, and Kwame, 12, were sold by their mother to a fisherman in 2014. After two years of hard labor, they returned home and were adopted by a family in Senya

Ghana.

Beraku,

Beraku,

83 trendmagazineglobal.com

Top: Beached fishing boats line the Gold Coast of Ghana, where “slave castles” built by traders held captured Africans headed to slavery in the Americas. Slavery of other kinds persists in the region.

A worker strolls past a stone arch along the banks of the fabled Li River in Guilin, China, known for its otherworldly karst mountains and terraced rice paddies.

A worker strolls past a stone arch along the banks of the fabled Li River in Guilin, China, known for its otherworldly karst mountains and terraced rice paddies.

84 TREND art + design + culture 2023

Top: A child wades across a playground flooded after torrential rains in Middletown, New York.

85 trendmagazineglobal.com

Looking up at an eave at 14th-century Jogyesa Temple with Seoul’s electrified cityscape in the background.

86 TREND art + design + culture 2023

In the Libyan Sahara, travelers converse as the sun sets near Ghadamès, a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as “the pearl of the desert.”

87 trendmagazineglobal.com

In one of Havana’s largest factories, a worker rolls cured tobacco leaves, the old method of making cigars by hand.

88 TREND art + design + culture 2023

A joyful delegate at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver learns that Illinois Senator Barack Obama was nominated for President of the United States.

Quick Study

LONNIE SCHLEIN’S YOUTH COULD BE THE PREMISE FOR A VINTAGE MUSICAL COMEDY, not least because his father, Irving Schlein, was a musical director for Broadway shows by the likes of Cole Porter. Dad took the family along on the 1956 national tour of Porter’s Silk Stockings, traveling in luxe railroad sleeper cars. When the company reached a destination, Jan Sherwood, the actress playing the lead, would pose for the press, pulling up her skirt to adjust her garter. After arriving in Los Angeles on the Santa Fe Super Chief, Schlein, a plucky 10-year-old at the time, took a shot and gave the picture to Sherwood. He still has her thank you note saying he was “an excellent photographer.”

With anyone else that would be just an endearing story, but it prefigures Schlein’s longtime fascination with celebrity photography. Over the years, he has photographed everyone from Mickey Rooney to Al Pacino to Paul McCartney.

In the 1980s, as the first photo editor of Arts & Leisure, then one of the fat Sunday feature sections of The New York Times, he and his wife, Monique, were one of the most sought-after couples in New York’s art world.

89 trendmagazineglobal.com

Schlein (far right) and top editors of The New York Times gather on the evening of September 11, 2001, to decide what the next day’s momentous front page will look like.

Thegranddancebeginsagain.Thepullofthemoon mustbeobeyed. - SamScott PieProjectsContemporaryArtishonoredtorepresentthefollowingartists: KATEJOYCE·CAROLINELIU·BRIANMCPARTLON·AUGUSTMUTH DANANEWMANN·EUGENENEWMANN·SAMSCOTT·SIGNESTEWART JUDYTUWALETSTIWA pieprojects.org |924bshooflyst.,santafe,newmexico,usa|505-372-7681

SamScott, HighTideFalling, oiloncanvas,84x120in.

Iamabletocreatefantasticalnarrativesthatsparklarger conversationsofloss,joy,andtheeternityofself. -

PieProjectsContemporaryArtishonoredtorepresentthefollowingartists: KATEJOYCE·CAROLINELIU·BRIANMCPARTLON·AUGUSTMUTH DANANEWMANN·EUGENENEWMANN·SAMSCOTT·SIGNESTEWART JUDYTUWALETSTIWA pieprojects.org |924bshooflyst.,santafe,newmexico,usa|505-372-7681

CarolineLiu

CarolineLiuinherstudio

Nudes and Landscapes

Contemplating and celebrating the female nude in contemporary photography