Tuesday April 15th 2025

Tuesday April 15th 2025

The Asian Art Society features an online catalogue every month listing quality works of Asian art that have been thoroughly vetted by our select members, who are the in-house experts.

By bringing together a group of trusted dealers specializing in Asian art, our platform offers a unique collection of works of art that collectors will not find anywhere else online. To ensure the highest standards, gallery membership is by invitation only and determined by a selection committee of influential gallerists.

Cover Image: Detail of a Khanjar Presented by Finch & co on p. 18 /AsianArtSociety

Pieces are published and changed each month. The objects are presented with a full description and corresponding dealers contact information Unlike auction sites or other platforms, we empower collectors to interact directly with the member dealers for enquiries and purchases by clicking on the e-mail adress.

In order to guarantee the quality of pieces available in the catalogues, objects are systematically validated by all our select members, who are the in-house experts. Collectors are therefore encouraged to decide and buy with complete confidence. In addition to this the Asian Art Society proposes a seven-day full money back return policy should the buyer not feel totally satisfied with a purchase. Items are presented by categories please check the table of contents.

Feel free to ask the price if the artwork is listed with a price on request.

M ARBL e BA s IN AN d s TAN d

China

Yuan dynasty

14th century

Basin: 45 cm (h.) x 80 cm (diam.)

Stand: 44 cm (h.) x 43 cm (w.)

Provenance:

Private English collection, purchased

c. 2000

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Rasti Fine Art Ltd.

M.:+852 2415 1888

E.: gallery@rastifineart.com

W.v: www.rastifineart.com

A ye LLOW ge M, POLKI

d IAMON d AN d e NAM e L

P e N d ANT, sus P e N d IN g

AN e M e RAL d B e A d

China

Length: 4,1cms

Weight: 9,9gms

Price: 1.200 GBP

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Sue Ollemans

M.: + 44 (0) 7775 566 356

E.: sue@ollemans.com W.: www.ollemans.com

CARV ed JA de IT e

China

Set with diamonds

Diameter of jade: 4,6 cm

Height from loop above diamonds to base of jade: 6 cm

Price: 3.500 GBP

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Sue Ollemans

M.: + 44 (0) 7775 566 356 E.: sue@ollemans.com W.: www.ollemans.com

Lady Cripps was a huge force for good and responsible for raising money for China in the 1940s to alleviate the appalling starvation there after the Japanese invasion. She visited China in the 1940s to give out this aid from the UK and was well entertained by the Nationalists, meeting Chiang Kai-Shek and Madam Chiang. who was immensely wealthy in her own right, being one of the famous Soong sisters. She then went into the mountains to meet Mao in Yunan and stayed there for about three days. While she was there the Nationalists and Communists stopped fighting because of her and fear of shooting down her plane.She was given gifts by both sides - from the Chiang KaiSheks and from Mao. An album of wood block prints from Mao just sold at auction .

She was strictly instructed by her husband to be super careful about not taking sides while she was there as it might otherwise be thought to be Britain’s official attitude to one side or the other…..her husband went on to be Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1950s.

W OMAN’s He A dd R ess

CALL ed Pe RAK

Ladakh, Northeast India

Circa 1960

Turquoise, coral, carnelian, motherof-pearl, leather and silver 75 cm (l.) x 50 cm (w.)

Provenance:

Belgian collection, the father of the actual owner acquired it in Asia in the early 90’ies

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Farah Massart

M.:+32 495 289 100

E.: art@famarte.be

W.: www.famarte.com

This woman’s headdress known as a perak is from Ladakh in Northeast India.

The headdress consists of a central oblong panel in red leather decorated with many rows of large turquoise beads and carnelian. An old silver ga’u box with applied filigree, coral and turquoise has been centrally placed. It is flanked to both sides by a black half-moon lambswool earflap, to protect the ears against cold weather. Five strands of braided fibre strings are sewn at the flaps, to be tied into a knot behind the woman’s back.

An additional rectangular pendant set is decorated with rows of mother-of-pearl, turquoise beads and red coral strings.

The perak’s visible surface is covered with 128 turquoise stones; the biggest turquoise stone is placed at the front point, followed by the next best stones, where they are most striking. The perak is in a good condition, all the stones appear to be original, none are missing. The marks on the reverse show that the piece have been worn on the head.

Draped over the top of a woman’s head the headdress looks like a raised cobra (naga) ready to strike. In Hindu and Buddhist iconography the cobra with expanded hood represents protection of a deity image, and the perak by analogy offers protection to the wearer.

The perak is a status symbol for Ladakhi women, her wealth and position are shown by the number and quality of the stones, with turquoise as the dominant element; the value of the stones acts as a form of old-age security. When preserved intact the perak was traditionally passed from mother to eldest daughter on her marriage as a family heirloom. Older examples that passed through several generations might be covered with more stones. When a woman has no daughter her perak could be inherited by a close female relative, given away to a monastery or traded in the area.

India

Late 18th to Early 19th century

The red velvet covered sheath with pierced silver mounts with a large ivory hilt, decorated with rosettes of Rubies

Length: 34 cm, 35, 5 cm with sheath

Miniature:

11 cm (h.) x 9,5 cm (wide max)

Provenance:

Private English collection

Publication:

Hales, Robert; Islamic and Oriental Arms and Armour, a lifetime’s Passion

Published by: Robert Hales 2013, Butler Tanner and Dennis Ltd, ISBN 978-0-9926315-0-5

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Finch & Co www.finch-and-co.co.uk E.: enquiries@finch-and-co.co.uk T.: +44 (0)7768 236921

Accompanying the dagger is a miniature portrait on ivory of The Maharajah of Vizianagram

An old label to the reverse reading: ’portrait of the Maharajah of Vizianagram. Presented with dagger to Gereral A. N. Rich about 1855 for saving his life when attacked by a wounded cheetah’

Gilt ormolo frame

Dagger: iVOrY ACT 2018: A certificate for a pre-1918 item of outstandingly high artistic, cultural or historical value. Certificate number: WH73KH97 03/04/2025

Miniature: defra permit number: GJ3AB38X

Going back to the era when Arabian states waged wars and expanded their borders, it’s hard not to be captivated by the beauty and craftsmanship of the weapons they created. One such weapon is the Khanjar, also known as the Jambiya in Yemen. Although its exact origins remain a mystery, it’s widely accepted that the tool was used for both warfare, domestic purposes, and trade.

The earliest known depiction of the Khanjar in Yemeni history is found on the statue of the Sabean King. Dating back to the year 500 BC, this statue is currently housed in the National Museum of Yemen in Sana’a.

The weapon depicted on the statue features an i-shaped hilt, which differs from the more common J-shaped hilt we see today. This suggests that the I-shaped hilt represents a precursor to the modern J-shaped hilt. The J-shape we see today is believed to have emerged due to trade with India and the conquest of Yemen by the Ottoman Empire between the 15th and 17th centuries.

During the Mughal era, Yemen and India had strong trade links, and a similar weapon was recorded in the text ‘Ain-i-Akbari’, which provides details about the administration of Akbar. This weapon, known as the Jambhwa in India, bears a resemblance to the Jambiya. Given the strong trade ties between Yemen and India, as well as the close connection between the words Jambiya and Jambhwa, it’s hypothesised that the weapon originated from either country. in 1763, the first recorded account of a J-shaped Jambiya dagger appeared in the writings of Carsten Niebhur, a German explorer serving Denmark. The dagger was presented to alMahdi ‘Abbas, the imam of Yemen, as part of the traditional garments worn by the Yemeni people. The Ottoman conquest and subsequent spread of the dagger led to its use in other Islamic lands. It gained another name, the Handschar, and was adopted in the Balkans. The Khanjar, a traditional dagger, has evolved over time. Today, it’s typically crafted from wood, metal, or camel bones.

In the past, the wealthy and powerful, Royalty, Sayyids, and Hashemites, adorned Khanjars with ivory or rhinoceros horn hilts. These hilts served as a symbol of their status and wealth.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, Khanjars were also highly effective for defence. The daggers were worn on the front and centre of the waist, providing comfort during camel and donkey travel. Their curved shape made them ideal for thrusting attacks, eliminating the need to bend the wrist. Additionally, their agility enhanced cutting and twisting movements. The weight of the blade contributed to their destructive power.

As firearms became more prevalent, the symbolic significance of Khanjars grew. While some domestic uses, such as slaughtering and skinning animals, persisted, the dagger became a symbol of pride in heritage, particularly in Yemen and Oman. It was integrated into traditional regalia, reflecting a commitment to family honour and tradition.

The Khanjar held special significance in marking life’s milestones. it symbolised masculinity and was presented to boys during their transition to adulthood. Similarly, it was considered part of the groom’s attire during weddings, signifying a willingness to protect the family. Moreover, the Khanjar represented continuity, family honour, and the preservation of traditions as it was passed down from father to son. The fact that our example, presented here, was gifted to General A. N. rich, testifies to the daggers huge ‘importance’ conveying the gratitude from Maharajah Vizianagram’s after his life was saved during their hunting trip.

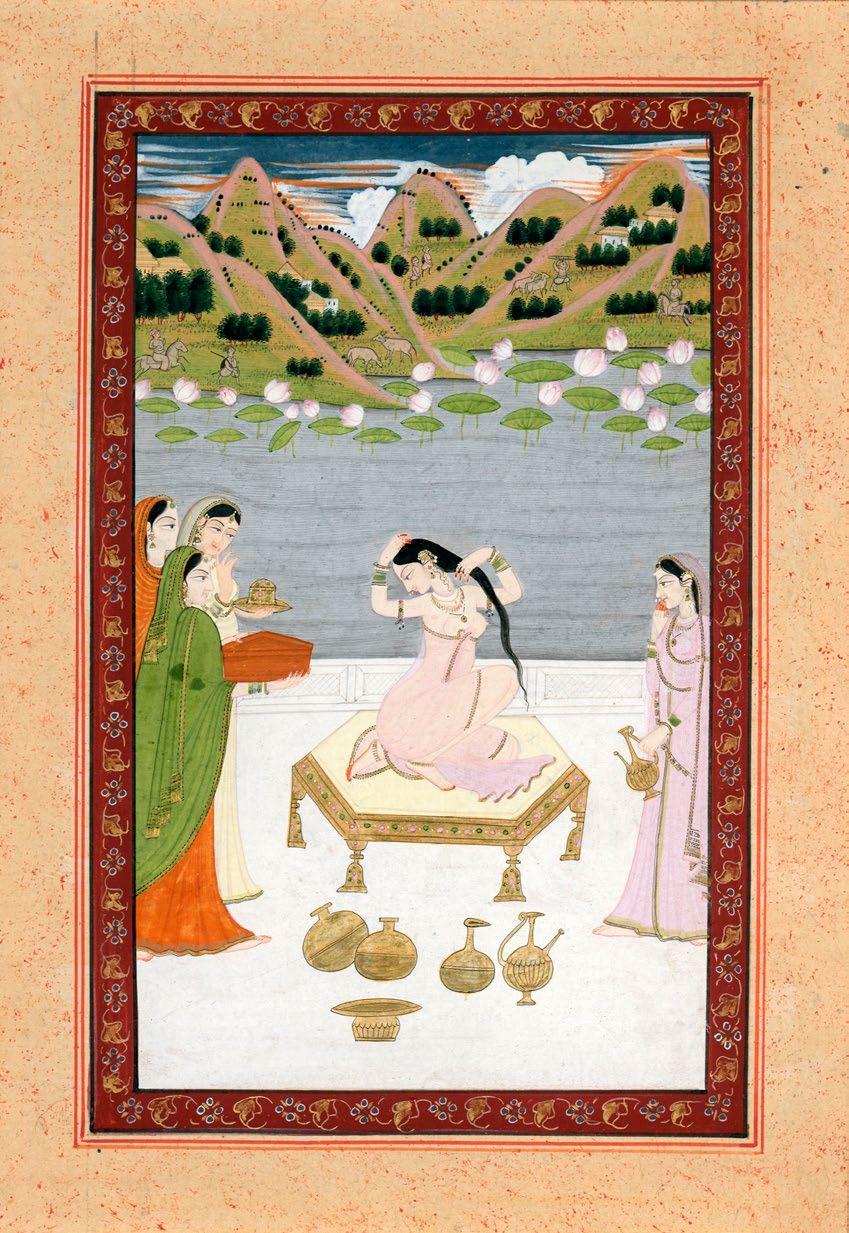

A NAy IKA P R e PARIN g TO Mee T H e R Be LOV ed

Kangra, India

Mid-19th century

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 19,5 cm x 12,7 cm

Folio: 26,7 cm x 17,8 cm

Provenance:

Christie’s New York, 6 July 1978, lot 64

Dr. Alec Simpson

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Kapoor Galleries

T.: + 1 (212) 794-2300

E.: info@kapoors.com

W.: www.kapoors.com

A nayika kneels on a gold and jeweled plinth, naked except for a transparent wrap and gold jewelry. Her lithe body turns as she wrings out her long black hair on the white marble terrace of the zenana. The woman is accompanied by four attentive handmaidens holding vessels that contain body oils, perfumes, ointments and lac for the palms of her hands and soles of her feet. As she prepares to greet her lover, the air is tense with anticipation. The blue, cloudy sky is streaked with red, rendering an evening sunset. In the middle distance rises a gray lotus-filled pond, the blossoms and leaves large and freshly blooming. In the far distance, a village set among steep hillsides is visible. Amidst its population of cowherds and small structures, two tiny mounted nobles gallop in from the left and right.

Compare these landscape features to a work signed by the artist Har Jaimal in W.G. Archer’s Visions of Courtly India, 1976, no. 73 and 74.

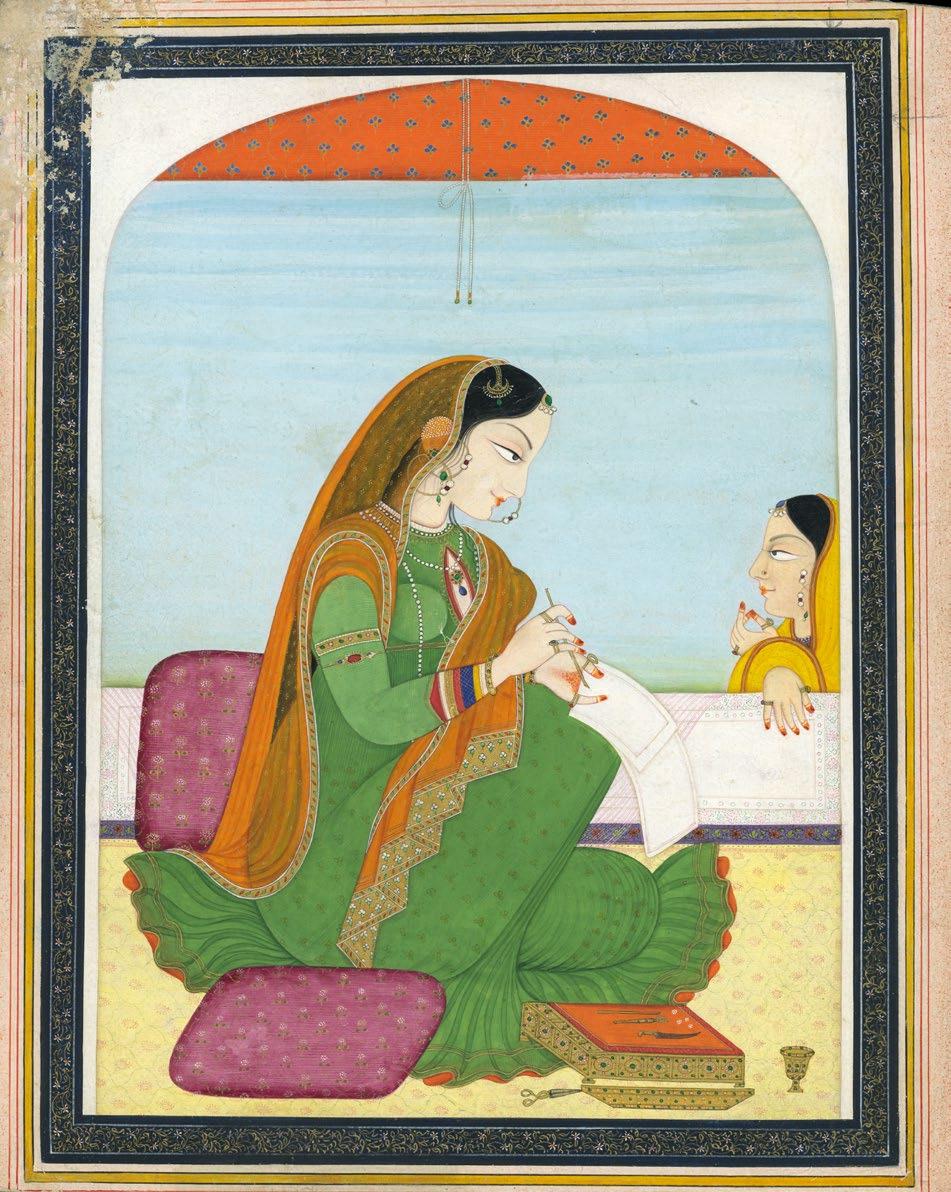

Kangra, India

Circa 1810-1830

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 21 cm x 15,2 cm

Folio: 24,8 cm x 19,7 cm

Provenance:

Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Kapoor Galleries

T.: + 1 (212) 794-2300

E.: info@kapoors.com

W.: www.kapoors.com

Within the frame of an arched window, a nayika (heroine) sits on a carpeted terrace dressed in a flowing green sari and orange veil with gold trim. She wears large ear and nose rings, strands of pearls and numerous jewels and ornaments. Her female companion awaiting the finished note to deliver to her beloved. Below, writing implements on a covered gold and jeweled plinth appear along with a knife, scissors, a small gold cup and a bowl.

The central female represents the consummate Kangra heroine, with a demurely lowered gaze and an archetypal profile, sharply defined features and jet black hair. Her fine nose, small red lips and shapely chin are enhanced by her subtle smile. Whether the figure is a courtesan or princess, this is an idealized rendering of a nayika, her features displaying the classic look of a perfect Pahari heroine found in countless miniatures since the development of the Kangra style. The present painting is a wonderful example of the pan-Pahari style of Kangra originated at Guler as a response to the increasing influence of naturalistic Mughal painting.

Kangra, India

Circa 1810

Opaque watercolor heightened with gold on paper

Image: 12,4 cm x 9,2 cm

Folio: 15,2 cm x 12,4 cm

Provenance:

Hellen and Joe Darion, New York, by February 1968 (no. 39)

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Kapoor Galleries

T.: + 1 (212) 794-2300

E.: info@kapoors.com

W.: www.kapoors.com

The wide and focused eye of the young maiden directs the viewer’s gaze directly to the figure’s hand with which she applies kajal in a mirror held by an affectionate child. She has already adorned herself with a tikka (hair ornament), nath (nose ring), earrings, necklaces, armbands, and rings. The vermillion on each of her fingertips matches that of the three layers of her diaphanous garments, decorated with green edges matching the window valence above. She appears to be preparing herself for an important event for which the child below has already been groomed. The child’s lavender dress matches the magenta and yellow textile that hangs over the base of the window, creating a pleasingly cohesive color palette.

The charming portrait is unmistakably Pahari, epitomizing a bold and colorful tradition that embraces naturalistic Mughal techniques. This type of architectural framing (a view through a window) is typical among paintings from Kangra, in particular, as is the deep blue border with a gold foliate motif and a secondary support of speckled pink paper.

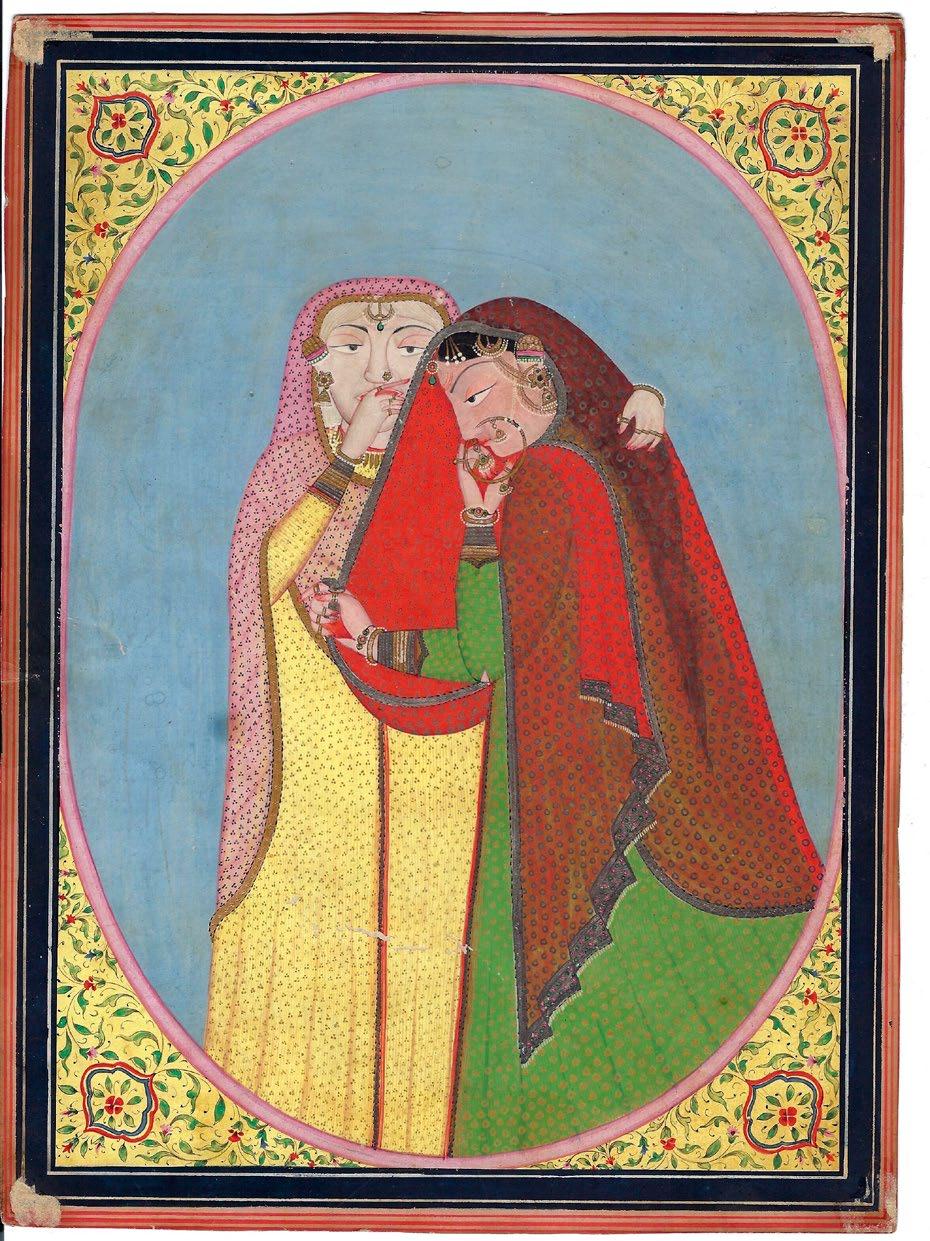

NAy IKA B H ed Mugd HA : NAVALA VA d H u (T H e Ne WLy Wedded)

Kangra, India

Circa 1810

Opaque watercolors heightened with gold on wasli

26 cm x 20 cm

Provenance:

Sotheby’s New York, March 21 and 22, 1990, lot 103

Price on request

Nayikas are a classification of heroines often in relation to dance or romance. They are put into a fourfold grouping by Keshav Das, according to age: up to sixteen (bala), from sixteen to thirty (taruni), from thirty to fifty-five (praudhaI), and over fiftyfive (vriddha). “The old and the learned say that tender in the years, this Nayika grows gradually, and her brilliance increases day by day” (M.S. Randhawa). This particular scene is an example of Mugdha or Navodha, which is subsequently divided into Navala-Vadha (the newly wedded).

The nayika can often be identified through common elements of her profile, a demurely lowered gaze, defined features and jet black hair. Her fine nose, small red lips and shapely chin are enhanced by her subtle smile. Whether the figure is a courtesan or princess, this is an idealized rendering of a nayika, her features displaying the classic look of a perfect Pahari heroine found in countless miniatures since the development of the Kangra style.

Here the maiden is seen dressed in green and draped by a delicate translucent orhani, garbed in elaborate jewelry seeking comfort from a companion. The piece is framed by an oval opening with floral motifs and a rosy pink border.

Reference: Randhawa, M. S. Kangra Paintings on Love. New Delhi: National Museum, 1962. Print. pgs. 34, 35, figure 11.

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Kapoor Galleries

T.: + 1 (212) 794-2300

E.: info@kapoors.com

W.: www.kapoors.com

A PAIR OF Ru B y AN d d IAMON d e ARRIN gs

North India

Late 19th century

Cabochon rubies set in a floral pattern around a polki diamond. The reverse decorated with incised black enamel on gold

Diameter: 3 cm

Price: 3.500 GBP

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Sue Ollemans

M.: + 44 (0) 7775 566 356 E.: sue@ollemans.com W.: www.ollemans.com

dO u BL e Red sHIP PAL e PAI

Paminggir

Kalianda District, Lampung, Sumatra, Indonesia

18th / Early 19th century

Cotton; metallic wrapped threads, silk; supplementary weft

79 cm x 424 cm

Provenance:

Samuel Josefowitz, Switzerland and New York

On loan to the Indianapolis Museum of Art for 30 years

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Thomas Murray

M.: + 1 415.378.0716

E.: thomas@tmurrayarts.com

W.: www.tmurrayarts.com

Double Red Ship Palepai are the most iconic of all Indonesian textiles and were extremely important in the Paminggir society. We see great ships, elephants, birds and human figures that have been interpreted as ancestors. However, this can only be speculated on as the last weavers who understood this rich iconography departed life more than a century ago, leaving no heirs to their knowledge.

Detail reveals the ’House of the Ancestors’

12

A N ANCI e NT JAVAN ese

ROyAL g OL d PART

A d ORNM e NT se T FOR A quee N, CON s I s TIN g OF A TOPKNOT CROWN WITH A ROCK-CRys TAL

FINIAL, A BR e A s T

ORNAM e NT, A B e LT, AN d A PAIR OF ge M-se T

u PP e R-ARM BRAC e L e T s, e ACH IN R e PO ussé

HI g H-CARAT g OL d

Java, Indonesia

Kingdom of Mataram, Central Javanese period

9th-10th century CE

Provenance:

Collection of a notable from the Hague, who stayed in the former Dutch East Indies around circa 1900; thence by descent

Purchased from the above by a distinguished Dutch collector (name is known to us) between 1970 and 1980

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Zebregs&Röell

+31 6 207 43671 dickie@zebregsroell.com www.zebregsroell.com

This object is registered at the Documentation Centre for Ancient Indonesian Art in Amsterdam.

We are grateful to the Documentation Centre for Ancient Indonesian Art in Amsterdam and Mr. Jaap Polak for their assistance in determining the specifics and date of this finial above.

royal Gold of java: Masterpieces of the Mataram Kingdom (8th–12th century)

royal gold, crafted for the royal court, often with solid parts cast in cire perdue, was adorned with gold plating, gold leaf, finely chased motifs, and repoussé goldwork - a technique in which relief is hammered from the reverse side with precision. These luxurious artefacts originate from Central Java between the 8th and 12th centuries, during the reign of the Mataram Kingdom (Medang), a HinduBuddhist kingdom that flourished from the 8th to the 11th century.

This royal goldwork, created using the repoussé technique, was carefully hammered, chased, and inlaid with polished gemstones, including cabochon-cut rubies, emeralds, glass, and black crystal. These gemstones were not merely decorative but were highly valued for their perceived protective qualities against malevolent forces and astrological meaning.

the repoussé technique and javanese Metalwork

Repoussé is a metalworking technique in which relief designs are hammered from the reverse side using various shapes and sizes of steel punches. This method was widely used

in Java and other parts of Indonesia, including Bali, Sumatra, and Borneo. The initial form was hammered from the back to create the basic shape, after which the finer details were meticulously chased and refined from the front - a process known as achèvement.

The craftsmen of Java were masters of this technique, achieving an extraordinary level of refinement. The application of repoussé on gold was widespread in ancient Java, particularly in royal jewellery and regalia, showcasing wealth and power and the high level of artistic and metallurgical skill in the region.

Gold was a symbol of royalty and a material of divine permanence. Unlike bronze and iron, which rust and corrode, or stone, which erodes over time, gold remains untarnished and unchanging, symbolizing immortality and divine power. The royal courts commissioned elaborate jewellery, regalia, and ceremonial objects, often decorated with floral and mythological motifs symbolising divine authority, protection, and cosmic order. The presence of gold and precious stones in royal ornaments reinforced the sacred status of the ruler, who was often regarded as a divinely appointed leader, a protector of Dharma (cosmic order), and an earthly counterpart of the gods.

Thus, such golden jewellery and royal regalia were not merely accessories but statements of prestige, status, and divine legitimacy. They illustrated the immense wealth of the Javanese elite and reflected the advanced craftsmanship achieved in this early period, highlighting

Java’s role as one of the great cultural and artistic centres of the Hindu-Buddhist world.

the Central javanese Period: A Flourishing Hindu-buddhist Civilization

The 8th to 12th centuries marked a period of great cultural, artistic, and religious development in Java, particularly under the Mataram Kingdom. Java became a spiritual and artistic hub during this era, heavily influenced by Indian Hindu-Buddhist traditions while developing its own distinct Javanese identity.

This period witnessed the construction of some of Southeast Asia’s most magnificent religious monuments, including Borobudur— the world’s largest Buddhist temple—and Prambanan, the grand Hindu temple complex dedicated to Shiva. These architectural marvels not only demonstrated the immense wealth and power of the Javanese rulers but also reflected a deep philosophical and religious syncretism that blended Hindu and Buddhist traditions into a uniquely Javanese form of spirituality. Besides architectural achievements, the culture saw a golden age in international trade, writing, science, poetry, music, etc.

As the Mataram Kingdom declined in the 11th century, political power shifted to eastern Java, giving rise to the Majapahit Empire, which would later become one of the greatest maritime empires in Southeast Asia. However, the artistic traditions, goldsmithing techniques, and cultural achievements of the Central Javanese period continued to influence Javanese craftsmanship for centuries, leaving a lasting legacy in Indonesian art and heritage.

A PAIR OF ANCI e NT

JAVAN ese ROyAL ge Mse T g OL d u PP e R-ARM BRAC e L e T s

Java, indonesia

Diam.: 11 (each)

Weight: 85 and 89 grams

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Zebregs&Röell +31 6 207 43671 dickie@zebregsroell.com www.zebregsroell.com

These armbands are crafted using the repoussé technique and show elegant scroll motifs and a central floral decoration. A primary green emerald, cut in an oval shape, possibly reused from another culture or period, is set at the centre, surrounded by cabochon-cut rubies, arranged in a repeated floral pattern on four sides. Some stones have eroded, and some are lost, which points to a rather brittle material. Perhaps pearls were used, which would not remain intact after such a long time.

The large-sized bands have a hollow construction and consist of two separate sections connected by a pin (now lost), suggesting that they were intended to be worn on the upper arm rather than the wrist. The distinct scroll motifs, known as ‘rolling ornament’, are seen in Javanese stone-carved temple reliefs and sculptures, including those at Borobudur and temples in Myanmar, Cambodia, and India.

A N ANCI e NT JAVAN ese

ROyAL g OL d BR e A s T

ORNAM e NT AN d A

ROyAL g OL d B e LT OR

WAI s TBAN d

Java, indonesia Gold

Breast ornament: 28,5 (h.) x 28 cm (W.) x 8 cm (D.) and weight: 160 grams

Waistband: 60 cm (l.) x 7 cm (h. max) x 1 cm (D.) and weight: 153 grams

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Zebregs&Röell

+31 6 207 43671 dickie@zebregsroell.com www.zebregsroell.com

it features elegant scroll motifs and floral decorations and is crafted from one thick sheet of gold, shaped through repoussé, hammering, chasing, and engraving techniques. Gold loops are soldered at both ends of the necklace for fastening around the neck.

The belt, using the same techniques, is crafted from three separate sheets of gold, connected by hinged sections secured with gold pins. Gold loops are soldered at either end for fastening, allowing the belt to be easily worn around the royal waist. Often, one person would wear two, three, or more belts.

A N ANCI e NT JAVAN ese

ROyAL g OL d TOPKNOT

usnisha CROWN

Java, Indonesia

Made of repoussé gold and adorned with a rock crystal orb finial with a gold flame placed behind it, the crown was used in Buddhist religious ceremonies 14,5 cm (h.) x 13,5 cm (w.)

Weight: 295 grams

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Zebregs&Röell +31 6 207 43671 dickie@zebregsroell.com www.zebregsroell.com

This crown, known as an Usnisha cover, was a royal crown from Java, worn by the highest royalty and intended to cover the topknot of a royal figure, or sometimes statues.

The curls on the crown reference the curls on the head of the Buddha, symbolizing that the king and queen are bodhisattvas - future Buddhas. Bodhisattvas are incarnations of enlightened beings who embody salvation in Buddhism. The small stylised curls symbolise snails, based on the myth of snails climbing onto the Buddha’s head to shield him from the scorching sun during meditation. According to legend, the Buddha was so immersed in his hours-long meditation on a hot day that he forgot the sun’s rays were shining on his bare head. The snails, with their cool and moist bodies, protected and cooled his smooth, exposed scalp. They enabled the Buddha to maintain his meditation for hours, though they themselves dried out from the heat. When the Buddha emerged from his meditation, he discovered 108 snails on his head. He realised that these snails had sacrificed their lives to create a distraction-free environment for his path to enlightenment.

The rock crystal orb atop the crown represents the protrusion on the Buddha’s head, known as the bump of wisdom. The crystal also enables the rulers to radiate light when wearing their crowns. A stylised flame, crafted from gold foil with a gold pin, is positioned behind the crystal sphere, possibly suggesting this light-emitting quality.

Similar crowns, all attributed by scholars to the late 9th and early 10th centuries, were found in central Java. The archaeological unveiling of the so-called Wonoboyo Hoard in 1990 was one

of the largest and most significant Javanese gold finds. in 2023, a fire raged at the National Museum in Jakarta, and although in early reports it was said that much of the collection was saved, it slowly became clear that many priceless artefacts were lost. Thus far, it is unknown whether the ancient Javanese gold collection has been saved from fire or theft, but many fear the worst.

Signed by Josen Zo and stamped by Seisan Japan

Edo era (1603-1868)

Inrô: 7 cm (h.) x 8 cm (w.) x 2,5 cm (d.)

Netsuke: 4 cm (l.) x 2,5 cm (w.) x 1,5 cm (d.)

Ojime: 1,5 cm (Diam.)

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by:

Galerie Tiago

M.: 00 33 1 42 92 09 12 –

00 33 6 60 58 54 78

E.: contact@galerietiago.com

Beautifull Inro of three compartments made in kinji lacquer with an hiro maki-e ornament chrysanthemum flowers of gold and silver lacquer. Inside is in fundame lacquer.

Presented with an Ojime in metal in the shape of a chrysanthemum flower and with its netsuke representing two chrysanthemum flower buds.

The chrysanthemum (kiku) in not only the heraldic symbol of the Japanese imperial family, it is also aflower with a complex history, still attached to the history of the Japanese isles. The flower is first described by Jacob Breynius in 1689, but it gets its name from Carolus linnaeus that named it after : “Chrys” from the root of the grecque word meaning “golden”, and “Anthemon” which mean flower, chrysanthemum is litteraly the golden flower

Far from the baleful meaning it has in Europe, the chrysanthemum in Japan is overall a symbol of power, but also of longevity and happiness. The golden flower originated from China and arrived in Japan along the Nara period, for long it was only regarded as medicinal plant to cure and drop fever.

In order to understand the symbolism behind the flower we have to go back to 1500-1400 BCE. Chrysantemum were already cultivated in China at the time, mostly as an aromatic and decorative plant. It was already considered as a noble plant with mysterious power, a flower so important only the nobility was able to grow it in their garden. The same flower can be identified on some of the oldest Chinese porcelain.

It is only around the VIII th century that the chrysanthemum is introduced in Japan and

risen to the status of national symbol. Later, the same flower will also be used as a model for the imperial signet.

Under the Heian era, the imperial family started to monopolize this symbol, by even creating a feast in its honour. On September 9th, or on the 9th days of the 9th month, the chōyō no sekku” festival is organized in Kamigamo sanctuary (Kyoto). After the ceremony of the chrysanthemum festival, a liturgic danse involving priests shooting bows and arrows while white raven costume take place. Which is then succeeded by an invitation to all children to compete in sumo wrestling inside the temple.

Even though this flower is well known over Japan for a long time now, it is only around the XIIIth century that the emperor GoToba choose to utilize the sixteen petaled chrysanthemum as its family crest. The heraldic of the chrysanthemum now represents all at once the emperor persona, the imperial family and the Japanese people. It is said that to honor former emperors their thrones were entirely covered in chrysanthemum flowers, originating the name of “Chrysanthemum thrones” to define the heir to Japan. Although formerly the appanage of the Japanese noble families, chrysanthemum growing became popular along the Edo period, originating from the imperial city o Kyoto. Numerous people dedicate their life to the selection and creation of new Chrysantemum varieties and expose their production in traditional family inn or among the numerous temples of Kyoto. All information, color, shape, name of the variety and even cost were conscientiously noted in a register. Even though it was essentially present in Kyoto, imperial city, between 1688 and 1703,

the culture of chrysanthemum then spread all over Japan.

In addition, chrysanthemum is also one of the four “Junzi”, which a literal transation could be “member of nobility”. Prunus orchid bamboo and chrysanthemum are together “the four nobles”. Each one symbolizes a season: Winter for the Prunus, spring for the orchid, summer for the bamboo, and autumn for the chrysanthemum. This “Junzi” are still used in pictural art all around Asia.

This rich symbolism is among the reason we find the chrysanthemum flowers all around, on the Japanese passport, or on the 50-yen coin for example. Also, the supreme order of the Chrysantemum is still existing today and is the highest-ranking distinction that a Japanese citizen can receive, it is attributed by the emperor.

Chrysantemum is thus the only flower to be awarded such high regards.

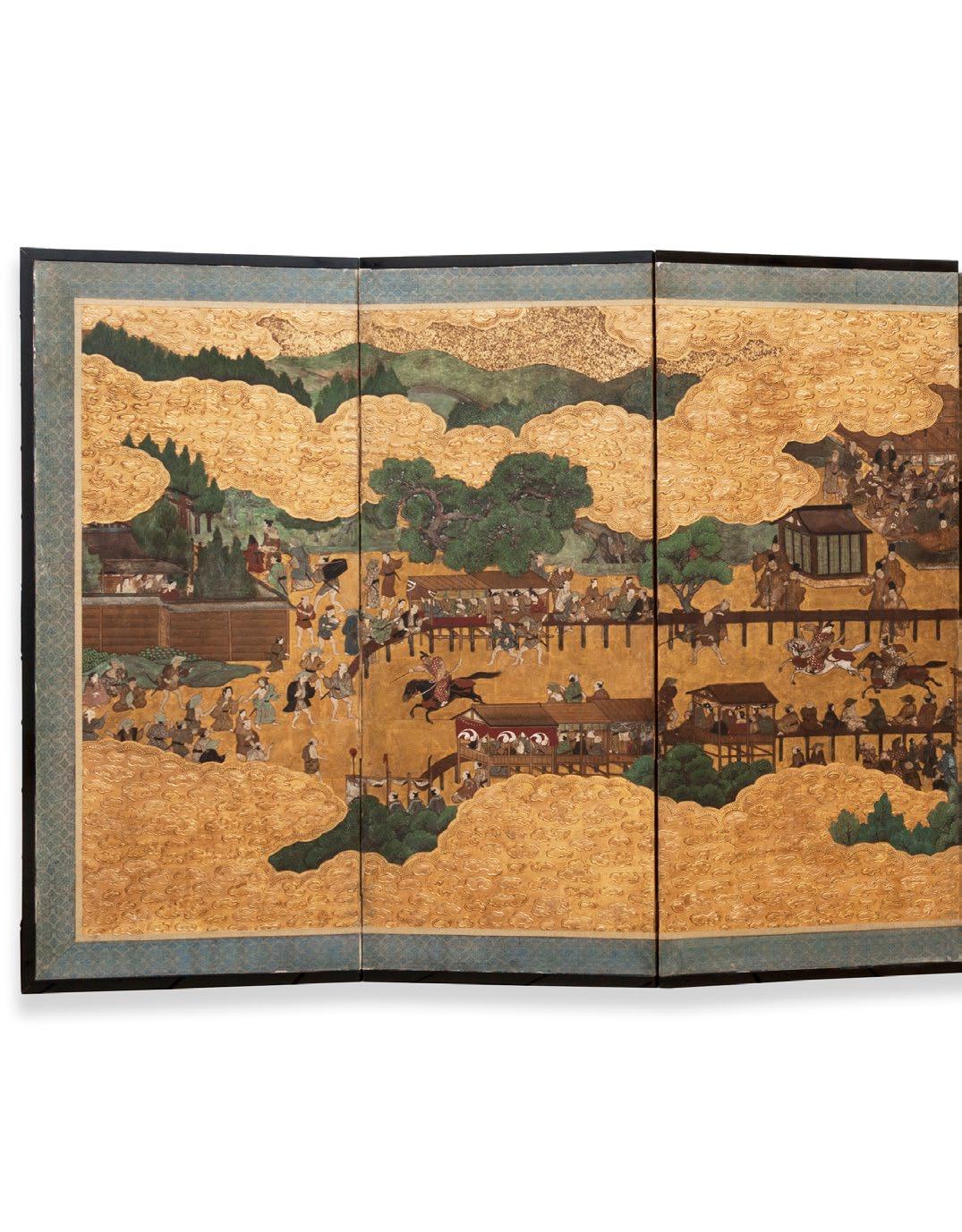

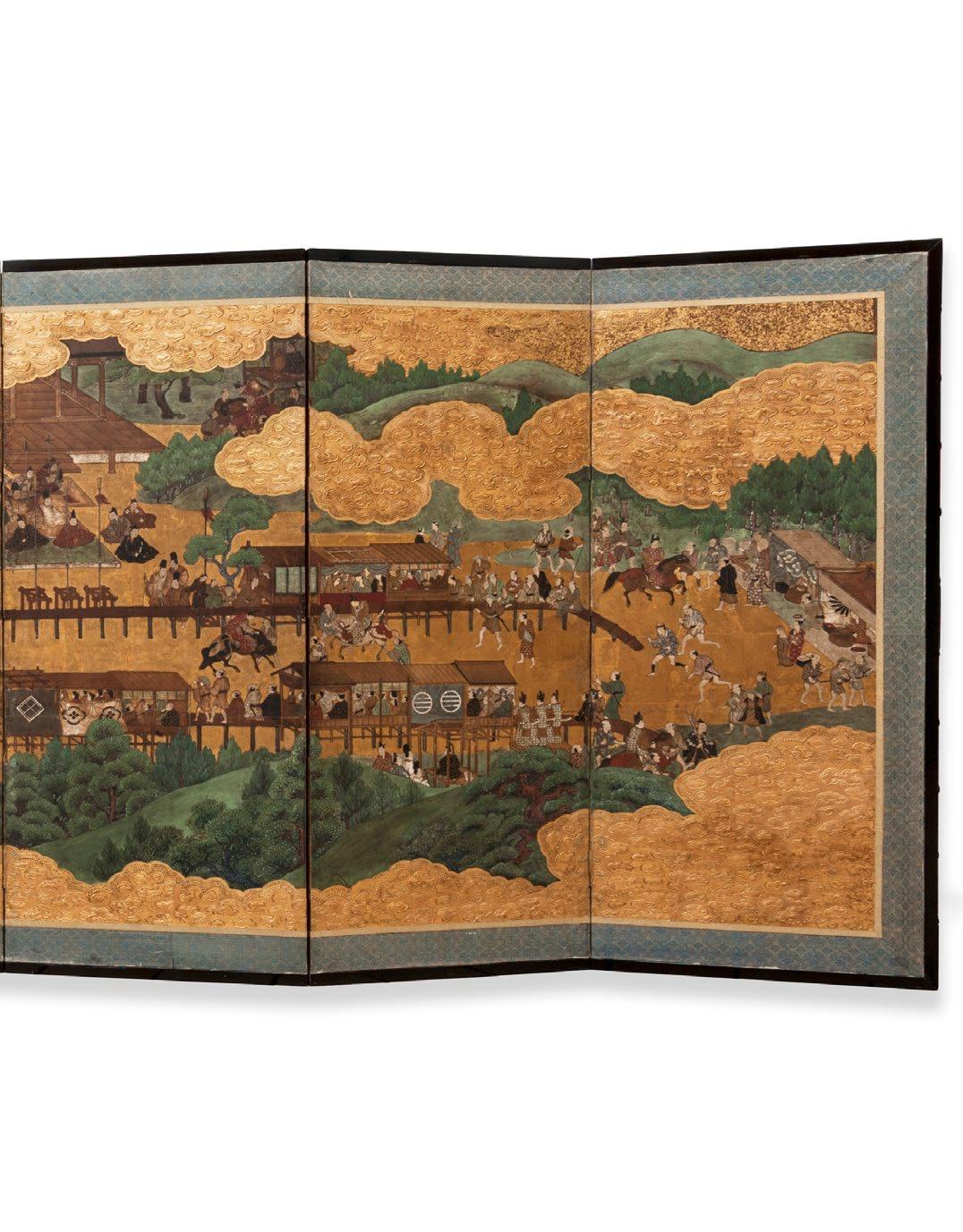

An exceptional pair of screens, each comprising six panels on goldbacked embossed paper decorated with horses races, called Kamo Kurabe-uma (ou Kamo Kurabeuma, 加茂競馬)

Japan

Tosa Mitsuyoshi (1539-1613, Tosa school) – Late Azuchi-Momoyama (1568-1600), early Edo (1603-1868) period

Late 16th – early 17th century

107 cm (h.) x 269 cm (l., each)

Length for the pair: 1143 cm

Price on request

Obj EC t Pr ESE nt E d by: Galerie Tiago

T.: 00 33 1 42 92 09 12

M.:00 33 6 60 58 54 78

E.: contact@galerietiago.com

The Kamo Kurabe-uma is a ritual horse race. Organized to pray for good harvests, peace and prosperity, it takes place as part of religious festivities to honor the deities of the Kamo shrine in Kyoto’s Kamigamo-jinja temple and is held every year on May 5. The race has its origins in the Heian period, the first edition being held in 1093.

On the back of each screen is a label on which is written the period of manufacture, the subject represented and the signature of the artist Tosa Mitsuyoshi (15391613, colloquial name Gyôbu, brush name Ky ûyoku, 土佐光吉). A painter of the late Azuchi-Momoyama (1568-1600) and early Edo (1603-1868) periods, he made his career in Sakai, Osaka prefecture, and was a member of the Tosa school.

The Tosa school was dedicated to yamato-e, the subjects and techniques of traditional Japanese art. This style is distinguished by its detailed depictions of scenes from the court, nature and Japanese literature.

Founded in the 15th century, members of the Tosa family held the position of head of the e-dokoro, the painting office at the imperial court in Kyoto. This hereditary position gave the Tosa an absolute artistic monopoly among the aristocratic and warrior classes.

However, in the following century, social unrest made the Tosa’s existence in Kyoto increasingly precarious. On the death of Tosa Mitsumoto (15301569), Tosa Mitsuyoshi lost contact with the imperial and shogunal e-dokoro and had to settle in Sakai, a trading port in Osaka prefecture. He placed himself under the patronage of wealthy merchants.

Several of the artist’s works are preserved in museums. Scenes from The Tale of Genji are in the Kyoto National Museum, the Sakai City Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.