10 minute read

History of Slavery in Missouri

The Boonslick took its name from the salt works begun in 1804 by Daniel Morgan Boone and his brother Nathan Boone, sons of famed frontiersman Daniel Boone. The older Boone had come to Missouri in 1799 at the invitation of the Spanish government and he settled in what is now St. Charles County.

The Boone brothers worked at a salt spring in what is now western Howard County and began manufacturing salt, an essential commodity for preserving meat.

Advertisement

The trail that developed from St. Charles to the salt lick became known as the Boonslick Road. The eastern edge of the Boonslick began at Thrall’s Prairie, named for tavern owner Agustus Thrall, who ran a tavern in Lexington, the first town within the boundaries of future Boone County.

“Standing on a high ridge along the eastern edge of the area referred to as Boonslick, Thrall’s Tavern provided a gateway, the link between the trail and the area of settlement,” Weil wrote in her thesis. “Thrall’s Tavern welcomed thousands of travelers into the western section of Missouri. Especially in these early years, the tavern played a crucial role in the young community.”

Weil, a teacher of history and psychology at Columbia Independent School, often brings her students on a field trip to the farm.

“We try to get them to imagine what it was like, you are cold, you are hungry, it is October, you have to harvest your crops from the farm and move,” she said. “You have to walk and everything is damp or wet or cold.”

Legal title to land on Thrall’s Prairie could not be obtained until 1818, when the federal land office opened in Franklin. Taylor Berry, a land speculator, likely used “New Madrid certificates” – claims for land to replace property destroyed in the 1811-12 earthquakes – to claim land that housed squatters, including Thrall.

Thrall purchased 160 acres of land in 1820 for $2,000.

Boone County was created by an act of the Territorial Legislature on Nov. 16, 1820. The thrust of development soon passed Lexington by.

It was not suited geographically to be the county seat because it was on the

This lunette depicts the April 2, 1821, meeting of the first Boone County Circuit Court. It was painted by Walter Ufer in 1927 as a decoration for the Missouri State Capitol Building. [IMAGE COURTESY MUSEUM OF ART & ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI]

western edge of the county. That honor went to Columbia, founded originally in 1818 as Smithton and moved moved a half-mile east to the banks of Flat Branch Creek in 1821. It was in Columbia where David Todd — uncle of future first lady Mary Todd Lincoln — would preside over the first circuit court session in April 1821.

The post office opened in Lexington in 1821 was closed by 1837.

The place lives on in the names of the people who settled on Thrall’s Prairie as place and street names. Anderson Woods was an original settler and John Woods Harris, his nephew, was a child of one when his parents arrived. He would later marry into the family that owned the Weil’s farm in the 1850s and improve it to become the Model Farm.

Harris gave his name to Harrisburg and Woods to Woodlandville.

The prosperity those early European inhabitants brought was evident in the 1830 census. The individual pages of the 1820 census for Missouri do not exist. Sixteen early settlers on Thrall’s Prairie who could be found in the 1830 count for Boone County owned 53 slaves, accounting for 32 percent of their households.

In 1839, that prosperity was enough to secure the University of Missouri for Columbia.

The land remains in production, and on a recent visit golden wheat was being harvested.

The Heffernans have worked to preserve the property and learn about it. An excavation in 2005 identified the site of the well and blacksmith shop, and artifacts they own range include hundreds of square nails and shards of glass. The town well was found and today it is enclosed in a chain link fence, overgrown but still full of water.

From the farm's more recent past, the Heffernans have a grist mill stone and steps from Harris’ plantation home, remnants of the Model Farm.

They have a duty to the past, Lisa Weil said, and they got that message loud and clear when the previous owner’s farm goods were sold after the family bought the land in 1991.

Floy McQuitty, born in 1894, was there, related to an early settler David McQuitty, was there.

“She stood 4-foot-10, maybe, on a good day,” Bill Heffernan recalled. “I could have just picked her up and carried her.”

Weil remembers her message for her father.

“She got right in Dad's face,” Weil said. “She came up at this event and said this is really important. There is a lot of history here and you need to take care of it.”

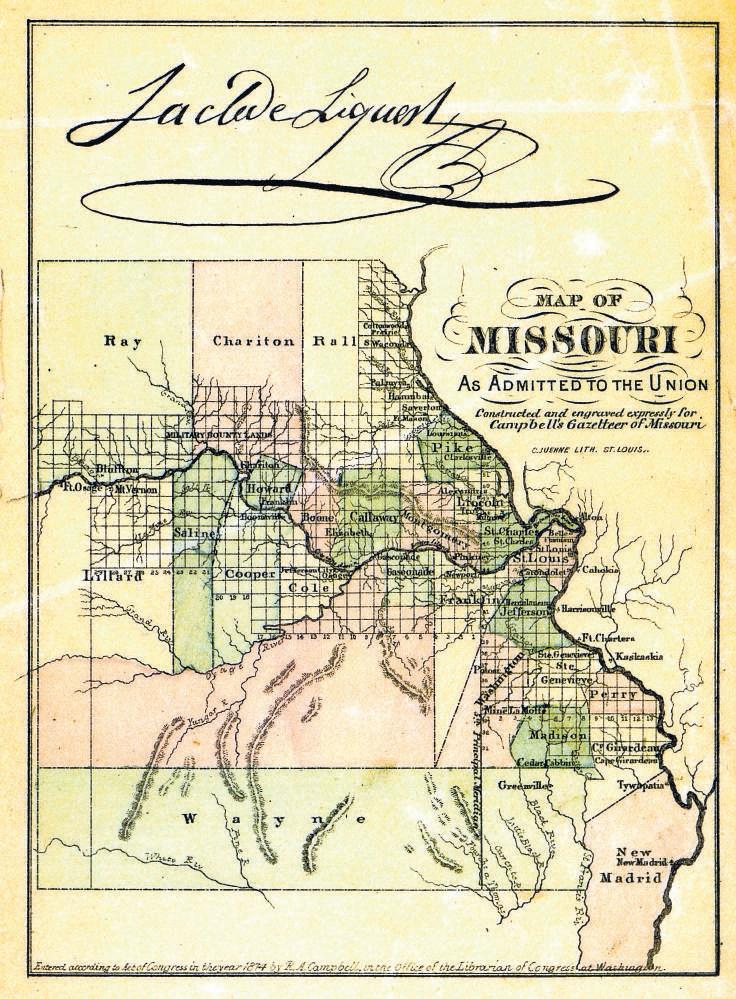

This map of Missouri at the time of its admission to the Union in 1821 shows only a few of the counties in the boundaries they have today, including Boone County, formed in November 1820. Missouri became a state under the 1820 Missouri Compromise, which barred slavery north of Missouri’s southern boundary in what remained of the Louisiana Purchase. [IMAGE COURTESY OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI]

ORIGINAL SIN

Slavery in Missouri remains a difficult issue as bicentennial approaches

BY RUDI KELLER | Columbia Daily Tribune F or most of two years in the early 19th Century, Congress was consumed by a debate over what to do about slavery in Missouri. And for much of that period, exactly how the issue would be decided was uncertain.

As the state approaches its bicentennial in 2021, how to explain Missouri’s birth in the pain of that debate – and the bloody legacy of racism that it bequeathed us – is also uncertain. But organizers know slavery, which has been called America's Original Sin, cannot be ignored.

“For me, I have been looking back at this issue some in part because I am working on a bicentennial history of Missouri that is a general overview from 1817 to the present,” said Gary Kremer, director of the State Historical Society of Missouri. “What has struck me so profoundly, and it is something that I knew anyway, but just how central race has been to Missouri history.”

The society will open its new home at the Center for Missouri Studies in August and is the lead agency in preparations for marking the state’s 200th anniversary. Exactly how it will tell the story of slavery in the center’s exhibits hasn’t been decided.

“I think we do need to remember that the bicentennial is not a celebration for every person who has a history with Missouri,” said Joan Stack, curator of the society’s art collection. “For some, that meant slavery being ensconced in our constitution and also the indigenous people gradually being forced out of our state.”

The long debate on Missouri started in 1819 and did not end until the state was officially admitted in August 1821. Anti-slavery representatives had the majority in the House but there was a balance of votes between slave and free states in the U.S. Senate.

In February 1819, Rep. James Tallmadge of New York introduced an amendment, which was adopted, barring settlers from bringing slaves to the state and slaves born after Missouri became a state would become free at age 25.

The Senate would not agree and Congress adjourned without an invitation to Missouri to write a constitution.

When that opportunity did come, the delegates wrote one of the most pro-slavery documents ever delivered for a new state. It required the state to compensate slaveowners if slaves were freed by law and guaranteed the right of slaveowners to bring their human property with them to the state.

It also barred “free negroes and mulattoes from coming to, and settling in, this state, under any pretext whatsoever.”

For the new arrivals in central Missouri, the issue wasn’t just theoretical. People had been streaming into the lands known as the Boonslick Country for several years, bringing families and slaves with them.

In the 1820 census of the Missouri Territory, 15.4 percent of the people in the state were slaves.

In central Missouri, the census for Howard County was divided into two

I T H I N K W E D O N E E D TO R E M E M B E R T H AT T H E B I C E N T E N N I A L I S N OT A C E L E B RAT I O N FO R EV E RY P E RSO N W H O H AS A H I STO RY W I T H M I SSO U R I . FO R SO M E , T H AT M E A N T S L AV E RY B E I N G E N SCO N C E D I N O U R CO N ST I T U T I O N A N D A LSO T H E I N D I G E N O U S P EO P L E G RA D UA L LY B E I N G FO R C E D OUT OF OUR STATE.

JOAN STACK CURATOR OF THE STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF MISSOURI’S ART COLLECTION

counts – east and west of the Bonne Femme Creek. The eastern portion, basically eastern Howard today and all of Boone County, had 5,466 people including 753 slaves. Boone County was not formed until November 1820.

Those white settlers who displaced the native tribes weren’t just men developing a wild land alone, Kremer said.

“In that sense, these were not selfreliant men,” Kremer said. “They were relying tremendously on their slaves and they were relying tremendously on their wives and their children.”

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 allowed the statehood of Missouri and Maine, Missouri as a slave state and Maine as free, keeping the balance in the U.S. Senate. It barred the creation of new slave states in the Louisiana Purchase territory north of Missouri’s southern border.

In 1820, that meant what is now Arkansas and a large portion of Oklahoma.

The defiant tone of the state’s first constitution, especially the prohibition on the entry of free blacks into the state, caused further problems in Washington.

“There are numerous themes that emerge in this period that are with us to this day,” Kremer said. “One is the conflict between state and federal control. If you go back and read the Missouri Gazetteer, or any newspapers from this period, what Missourians are complaining about most vigorously is they don’t want the federal government to tell us what to do.”

Congress demanded a statement from the legislature that it would not prohibit citizens from exercising their rights – granted by lawmakers in a special session in 1821 – and finally approved Missouri statehood later that year.

The Missouri Compromise lasted until 1850 as a political solution for slavery. During that period, abolitionism grew in the North and views hardened in slave states. The attempt at compromise in 1850 to grant California statehood as a free state lasted but a few years.

The Civil War finally ended slavery, with Missouri enduring armies camped on its soil and guerrilla warfare that left people dead on their doorsteps. Missouri freed its slaves in January 1865.

During debate on the Tallmadge Amendment, Rep. John Taylor of New York foresaw tragedy if Missouri was allowed to retain slavery.

“History will record the decision of this day as exerting its influence for centuries to come over the population of half our continent,” he said. “If we reject the amendment and suffer this evil, now easily eradicated, to strike its roots so deep in the soil it can never be removed, shall we not furnish some apology for doubting our sincerity when we deplore its existence …”