november mcmlxiv

Registered at G..P8s H O., Melbourne, for transmissionby post as a periodical +

november mcmlxiv

Registered at G..P8s H O., Melbourne, for transmissionby post as a periodical +

"To communicate is our passion and our despair."

WILLIAM

GOLDING, "Free Fall"

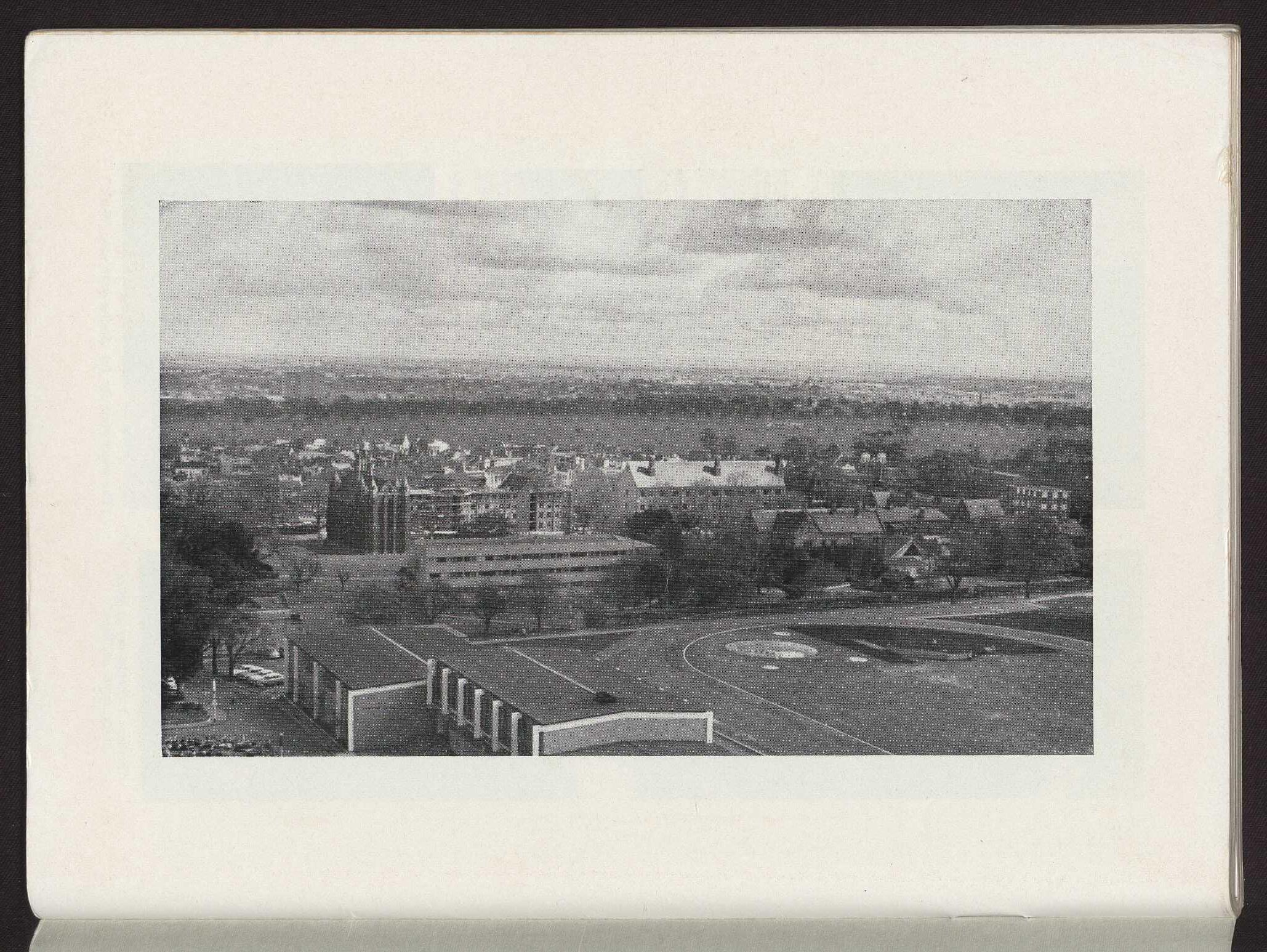

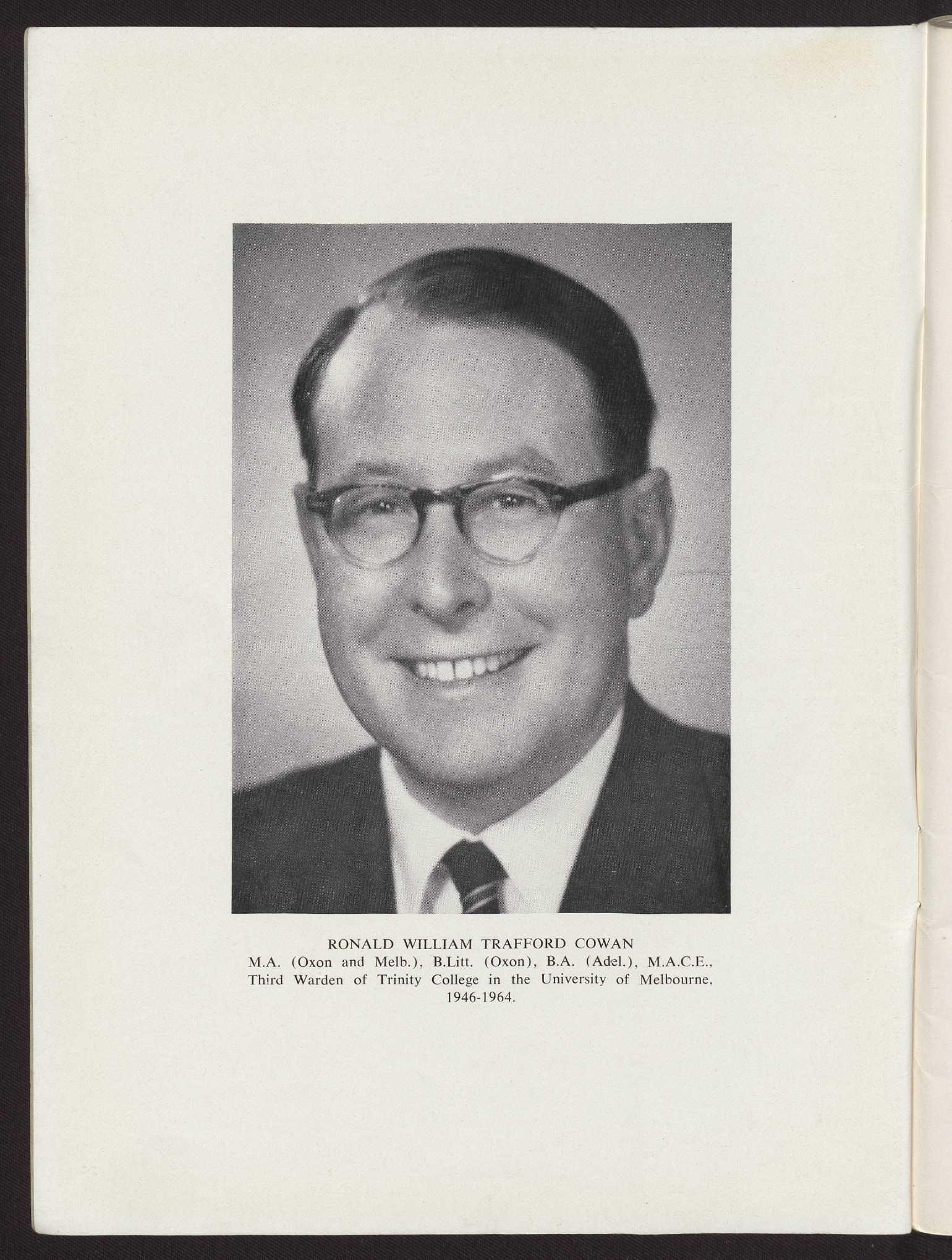

the University of Melbourne, 1946-1964.

The Magazine of Trinity College and Janet Clarke Hall in the University of Melbourne

November 1964

It is easy to hold forth about "The College" without trying to form a coherent picture of its functions, both ideally and actually. "The College" should do this or be thus; we all have obligations to "The College." What are the functions of the College, and what obligations do they impose upon us?

We must ask ourselves why we come into college. I think the first reason is the sheer convenience of living in college: Trinity would lose much of its attraction if it were ten miles from the University, or if we had to cook for ourselves.

The second main reason is the companionship of fellow-students: we like to be able to talk and form groups with like-minded people. As University students, we are supposed to be more "active" than most people. We have the capacity and inclination to work out for ourselves the pattern of our life instead of accepting that which society lays before us. We have the opportunity of forming groups to further our interests — sporting clubs, political bodies, cultural activities and informal discussion groups of all kinds. We hope that in a University there will be a higher involvement in our interests than in the community at large. The College, by bringing us all together, makes it easier for us to pursue these interests.

A third reason is the academic role of the College: to supplement the teaching of the University. The College can give the personal guidance that a University of 13,000 students cannot provide.

Finally, the College offers us a sense of community which the University cannot give us. In particular, it can provide a spiritual life through corporate worship and the personal witness of living Christianity.

It will be noticed that in all of these reasons the College is an adjunct to the University, compensating for its inadequacies but not supplanting it. The College does not exist independently of the University, but in conjunction with it. Its function is to enable us to live a fuller life as University students.

Few would disagree with this analysis. But its practical application raises difficulties. What happens when our University activities clash with our College activities — and most of

the respondents to this year's questionnaire agreed that they did? It is easy to say that we should give first priority to the University, but does this mean that a student without time for both should write an article for "Farrago" rather than watch the College football? All activities make demands on our time, and the more we participate in the general life of the University, the less we have available for College activities — and "the general life of the University" does not stop short at organised bodies and meetings, but extends to informal discussion in the Caf. and just keeping informed about current issues such as University finance or student morals.

It is becoming a part of the conventional wisdom to fulminate against "apathy", and to drum up attendance at College functions on the assumption that people should give these first priority. But if it is pressure of University activities that causes low attendance, then the College would be defeating its own ends by making them take second place to its own claims. Is the College competing with a University instead of supplementing it? We lose more than we gain by allowing College life to be a substitute for that of the University.

HAL COLEBATCH.

When we have left this College we will have little time for thinking generally; enmeshed in professional demands and driven by a ratchet of affluent survival, we will naturally be engrossed in localised affairs. The danger is that, when troubled by the inefficiencies, inadequacies and injustices of our society, we should concentrate futilely on healing our own little cells, without thought of curing the illness in the whole organism. While we are in College we have the luxury of being only loosely pressured, and can thus idle our time in evoking general principles — general principles which need application when so many people suffer from present haphazard organisation. This editorial offers as a main principle one so innocuous and acceptable as to seem completely unfunctional: "Our major aim should be to raise the level of personal contact throughout our community." This principle has immediate application to the problem of work — not the physicist's quantity, but the wage-earner's burden.

An optimistic estimate is that one-quarter of the Australian working force derive satisfaction from their jobs. The rest spent twothirds of their awakened hours in resigned boredom. Presumably, we, who are going to become professionals and academics, will be prepared to work hard in return for intellectual stimulation, responsibility and large salaries. But what of those employees whose greatest intellectual stimulation at the office is the "Sun" crossword (illicitly enjoyed)?: whose only responsibility is punctuality in serving the specified eight hours between the regulated times?: whose salaries and meagre annual leave give thin coating to the distasteful pill? What level of personal contact can one expect from a man who, after a full day of fatiguing and uninteresting work, is only too thankful to sink into a comfortable chair and absorb TV? It is a remarkably short-sighted community in which organisations merely strive to satisfy the demands of people in the few hours per day in which they are not working for these very organisations.

In an attempt to solve this problem, an initial move would be to pay psychologists to determine what are the factors of satisfaction in employment; large organisations would then act on their suggestions. This latter, of course, just could not happen at present. The shareholders of a "public" company will not allow any of the profits to be squandered in providing "luxuries" for company personnel; a conservative Federal Government, heavily supported by the owners of the large commercial and industrial organisations, will not spend any of the taxpayers' money in making public servants' jobs "cushier" — conveniently forgetting that public servants comprise a large minority of all taxpayers. The only way in which this problem will be recognised and attacked by Australian employers is for we ourselves, who through our ability and training will achieve positions of influence in this community, to recognise such problems ourselves and exert that influence to the common weal.

PETER GERRAND.

It seems obvious to say that one of the functions of a university is to encourage thought, and indeed it has been said many times before. But many students at this university do not think either long or deeply. There are many reasons for this: pressure of work, family background, personal difficulties, or laziness. All of these, except perhaps the last, are advanced from time to time to excuse or explain "apathetic" behaviour. "Apathy" has in fact become almost a proverbial joke. It seems then that there is still room for a discussion of how this situation arose and what, if anything, can be done about it.

It is true that many students are under pressures which make it difficult for them to take time off from their work without feeling guilty; and the less actively their time off is spent the less justifiable it feels. An evening spent at "Lawrence of Arabia" seems more profitable than an afternoon talking over coffee. Moreover, many students feel that when they do stop working the last thing they want to do is to think hard and rationally about important issues, since one of their nominal reasons for relaxing is fatigue. This is reasonable, and it is possible that while there is so much pressure to keep up with constantly increasing academic requirements it will be more and more difficult to think in general. Quotas, family expectations, and financial insecurity (often the fear of losing a scholarship) all operate to make us feel that if we are not working, at any rate we ought to be, and our time off ought to be nominally productive.

There are other factors which make it hard to break out of the opinions and values of our families or friends. It is difficult to make new friends in a university as large as this one, and many people have an understandable reluctance to join a club or group where they do not already know someone. It is inevitable

that we come up to the university with already formed ideas on politics, religion and the purpose of life, if our last years at school were at all interesting; and since these ideas are unlikely to be permanently satisfactory it is desirable that we should find other people who do not hold them, so as to realise that it is possible for other opinions to exist. Hence it is very important to make new friends at the university, no matter how hard this may be.

Unfortunately, we shall feel no impulse to do this if all we want out of our courses is a degree and a qualification for a better-paid job, or alternatively an occupation which will put off the day when we have to decide what job we want to take — a very common reason for girls to do Arts. Sweet-sherry values and the effect of a two-car garage on our principles of life may be vehemently denied by most members of college. But we are inescapably part of the community we live in, and unless we become aware of how much we are in fact influenced by prevailing values, we shall fmd it very difficult to throw them off or at least accept them critically.

Contact between people of different interests and concerns is clearly more possible in a college than in the university generally. And presumably if we are in a college we are less worried about failing ("the cream of the university"), and so will not be under the pressures which do limit even good students who are not confident of their own ability. The college should be able to do more than give folksingers an opportunity to get together and football fans a group to cheer for, or introverts the chance to get bawdily and acceptably drunk. Perhaps we should think more seriously that we don't know where we're going.

KATHARINE PATRICK.

With the death of Ronald Cowan, an era of College history has ended.

In appreciation of this man, we publish five articles below. The first is of the man and his career: it is the sermon preached at the funeral service in St. Paul's Cathedral by the Chaplain of the College, the Rev. Dr. B. R. Marshall, O.G.S. The other four are of the man as Warden: the authors were members of the College at different periods of his rule. Peter Balmford was a student at Trinity from 1946 to 1949, and a resident tutor from 1950 to 1962. Robe rt Todd (1951-1954) was Senior Student in 1954 and a tutor in 1958. Ian Donaldson (1954-1957) was also Senior Student in his final year. Michael Jones (19571963) was Senior Student in 1960 and 1962.

"And what can David say more unto thee? For thou, Lord God, knowest thy servant."— II Samuel 7, v. 20.

There was a moment in the life of King David upon which all his days converged. His past and his future gravitated, in the infinite time reckoning, upon that hour when for him his future was revealed. His judgment had occurred in the midst of his days and the rest of his long life was merely the working out of prophecy. Taken overall, he was found wanting. The great hero of the Jewish people, the type of Christ, the poet and singer of Israel and her glory, was revealed to himself, through him unto whom all hearts are open — and so is revealed to all the world as long as there is mankind upon the earth. His great achievement and his dismal failures lay side by side, in a moment of devastating clarity such as few of us could stand, and in the words of the prophet he came to know that his greatest ambition — the ambition to build a worthy temple to God — would never be realised. But, then, he was a great man. There was no spirit of recrimination or querulous questioning to be found in him, and so it was that the man who procured the death of another in order to steal his wife, and the man for whom his companions ran the most incredible risks

to satisfy his merest whim, and the man who mourned for his enemy as though he were his blood brother, the man who was plainly known in his power and his weakness. went in and sat before the Lord and said, "What can David say more unto thee? For thou, Lord God, knowest thy servant."

It is a bitter thing to reflect how far we are from that — from that devastating clarity of knowledge, whereby a man lies open before us. Our society does not encourage it. We are, it seems, incurably pluralist, and we love to have it so. Could we really stand a reconstruction of Israel where there was no Church and State. no fragmentation of human interests where our actions in one field of human endeavour were necessarily seen to involve every other? We tend' to fight the battles of life on a number of largely non-related fronts. We find it very easy to shrug off the consistency to which our conscience directs us because we are, as we say, cogs in the machine, and having delivered ourselves of this devastatingly original aphorism, resign ourselves to live with our multiple personalities, be they never so controlled. Though perhaps we pray for the moment to come when we could, as David did, sit down before the Lord, and say "For thou, Lord God, knowest thy servant."

But for most of us such honesty is rare, and our self-examinations are few and far between. We are greatly helped by the fact that when they happen, we are both Prosecutor, Judge and Jury, and so the verdict is assured — but with Ronald Cowan, what are to us fleeting moments of humility were to him a permanent attitude of mind. "Thou, Lord God, knowest thy servant" inasmuch as one might add, "thy servant knoweth Thee, O God."

From the beginning he was marked out as a person with a notable future. From the time he arrived at St. Peter's College, Adelaide, in 1928, the immense diversity of his skills and interests asserted itself. He not only represented his school in three different sports, but was prominent in almost every aspect of the school life — as Secretary of the Literary Society, editor of the School Magazine, an intercollegiate debater, School Librarian, a server and crucifer in the Chapel, a Rover Mate, and R.S.M. of the Cadet Corps, culminating in his appointment in 1932 as School Captain. On

the purely academic side he completed his school career with a dozen prizes, the Bruce Coulter medal and six scholarships or exhibitions.

His time at St. Mark's College (of which he was a scholar), and at the University of Adelaide, was similarly distinguished. He won his colours for athletics and football, continued his interests in library work, debating and scouting, was prominent in three University Committees, and at the end of 1935 won a scholarship in Modern History. At the end of the same year he was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship, though he did not take it up until the end of 1936, when he graduated in the School of History and Political Science with First Class Honours.

He went up to Oxford in 1937 and matriculated as a member of New College the same year. Oxford is always overwhelming to the newcomer and many Australians become oppressed by the sheer grinding competitiveness of the academic atmosphere and sink into a complete though sometimes learned obscurity. This did not happen to Ronald Cowan. He was a well-known member of his College, and played cricket for it with considerable success. He treasured up a cutting from the "Oxford Mail" of the eleventh of September, 1937, which notes cryptically, "Mr. R. W. T. Cowan, of New College, was fined 10/- for cycling without a light after dark, and 5/- for carrying Mr. R. Lloyd, of Balliol, on his bicycle. For allowing himself to be carried, Mr. Lloyd was fined 5/-." He graduated in 1938 in the Honours School of Modern Greats, and was only beaten to the highest places by such men as R. N. W. Blake, the biographer of Haig, later Senior Censor of Christ Church, and G. Seton-Watson, whose were names to conjure with in post-war Oxford. Upon the completion of his degree he submitted a thesis for the degree of Bachelor of Letters, and so his future began to take shape. The young Mr. Cowan, the newly appointed Rhodes Scholar, was interested in politics, so it was reported, but his true vocation was not yet realised— but thou, O Lord, thou knowest thy servant.

Of his distinguished career during the Second World War, during which he was commissioned in the field, others will doubtless write or speak with greater knowledge. The bare outlines of his career, both in the Middle East and on the Kokoda Trail indicate that he has lost nothing of his pristine thoroughness and general attention to detail. He was sec-

onded to Canada in 1944 as Chief Instructor of the Intelligence Training Wing of the Royal Canadian Military College, Kingston, Ontario. He was once interviewed in Canada by an eager young cadet for a Military Academy magazine, who noted with amazement that Major Cowan was extremely reluctant to use the word "I" but was quite willing to relate the experiences of others in his area — which, his young reviewer sagely remarked, is common in men who have been in action — but I think he was thinking of another generation. For this was not a general example but rather of one possessed of penetrating self-awareness and humility, of one who constantly said, "Truly, O Lord God, thou knowest thy servant."

When the war was over, Ronald Cowan found himself in the midst of a whirlwind political campaign in the first post-war election in South Australia. "Soldier, scholar and sportsman" said the slogan — "Support a Government with a good record by returning a candidate with a good record"; but may we not congratulate the caution of the voters of the electorate of Victoria for deciding, by a mere handful of votes, that they did not really know him quite well enough to let him represent the South-East of the State? So he was lost to politics, to our eternal thankfulness, and, doubtless, because the Lord knew his servant.

In 1946 he was appointed the Third Warden of Trinity College, within the University of Melbourne. He had been a tutor at St. Mark's, Adelaide, briefly before enlisting, and from that he found himself at the head of a famous College with a formidable tradition and as the successor of the great and never-to-be-forgotten Sir John Behan. As a member of the College at that time, and as one who was present in the Junior Common Room on that night in Second Term, 1946, when the College first met its new Warden at close quarters, I do not think we were either sympathetic or insightful into the enormous problems he was to face in the post-war years. We looked at each other in slightly veiled hostility, comparing this tough little man with the Olympian proportions of old Jock Behan. He was thirty-two and was junior both in age and military rank to some of the undergraduate members of the College which had a large proportion of exservicemen generally and ex-prisoners-of-war in particular. "Treat me right, I'll treat you right. Kick me hard, I'll kick you hard", he

said, and stumped out of the room, sweating, as he admitted to me fifteen years later, with fear and general foreboding.

He need not have worried. He listened to all Dr. J. C. V. Behan's admirable advice, kept an open ear and open mind to the knowledgable views of Mr. Sydney Wynne, the Overseer, and ran the College as he thought it ought to be run. And when one says that for the first seven years nothing spectacular occurred, that in itself was a remarkable achievement in the unsettlement of the post-war years.

He was to have scores of outside interests, but despite all their demands, he addressed himself to the problems of academic and economic administration with a relentless thoroughness. He was, as he styled himself, "honorary Bursar," and this led him into consideration of the Last penny, spent or earned, with a perseverance that must have deeply gratified his predecessor, who was also noted for this. To the time-waster and the chronic neglecter of opportunities, he was an implacable foe. The end of term gathering, euphemistically called the "Warden's sherry party," will long be remembered by all those who were obliged to attend them. His contact with the academic world was quickly established and the tradition of resident and non-resident tutors was carefully maintained. There was not a single student activity within the College to which he did not give attention and was quick to point out that some traditions so-called could be dropped without loss. He gave the utmost encouragement to sporting activities and the Dialectic Society, to mention only a few of the more permanent institutions, and to the Chaplain, he gave every support and the benefit of his wisdom.

But the Lord knew his servant, and at this point any attempt at a curriculum vitae falls to the ground. Slowly, but with growing momentum, Melbourne saw in him the man, it seems, for whom it must have been waiting. It was not sufficient that he should preside over Trinity College, and, through its Committee, over Janet Clarke Hall and later on its Council, and all this with care and minute attention to detail and profitable experience. He was called to serve on the University Council in 1952 and between that year and 1955 served on at least fifteen sub-committees. He was a member of two University faculties, Vice-President of the Staff Association, and in 1953 became president of the M.U. Football Club. But, as though the demands of his own campus

were insufficient, he unhesitatingly gave himself up to the demands of the great post-war expansion in higher education — thus it was that he was made a member of the interim Council of Monash University in 1958 and of the Council itself in 1961. International House claimed him and he spent time not merely in conferring about its future, but in raising money for it by sheer personal effort. In 1947 he became a member of the Council of Melbourne Grammar School, and gave it invaluable assistance again during those years of construction and development. He kept in touch with his fellow Rhodes Scholars and was secretary for the Rhodes Scholars resident in Victoria. He joined the Beefsteak Club in 1947, and in 1949 he was elected Chairman of Melbourne Rotary and served with distinction on a great many of its committees— but time would fail on such an occasion as this. Reciting a bleak list of the manifold activities of this remarkable man and of the ramifications of his interests: Y.M.C.A., Scouting in Victoria, endless committees of appeals, including the Committee for the rehabilitation of Hungarian students in 1958 and, latterly, the chairmanship of the Overseas Service Bureau. On the more formal side he was a member of the Executive of the Australian Council for Educational Research, and a member of the Australian Council of Education, as from 1959. Up to his very last days in hospital he was editing a volume of essays on Education which, one has no doubt, will be of the utmost importance. Truly, indeed, the Lord knew his servant.

His public image, as mediated through the newspapers, was as of a pricker of large and puffed-up balloons. Every sacred cow of the educational world came under his penetrating gaze and was subjected to his absolutely honest judgment. Compulsory education, the darling of democracy, has failed after seventyfive years, he said in Ballarat in 1946. Our fathers made the fatal mistake — they reckoned without religion as part of the educational process. The Universities were not immune for they, he said in 1950, turn out Quiz Kids and plum-job seekers. "The indications are that university education is a mass effort tending to produce people of a nice streamlined and deadly monotonous character" — the Melbourne "Sun" gleefully remarked that four university professors declined to comment. He had a fatal gift for relevant statistics. Many will remember the

controversy in 1953 when the question of a 25% increase of University fees was raised. It should be 33-1/3%, said the Warden of Trinity. For every hundred students, 60 are assisted by outside funds, he pointed out, and of these 60 only 8, on an average, fail. Of the 40 unassisted students, only 8 passed. "Of such people, speaking quite brutally," said the Warden, "I feel we should be doing the University a service if we made it known that this institution is no place for them." It was brutal and absolutely true; those words will have a strangely familiar ring in the ears of some of the younger members of the congregation.

The more recent controversy over the third university is still current with us. "Without the proper developments of the present resources and present university commitments, all that can possibly happen," said the Warden in a very characteristic phrase, "is that there will be a long discordant jangle as the education machine runs down."

Almost all these views brought forth both approval and wails of displeasure, but no one, enemy or sympathiser, could dispute the absolute honesty in which these decisions were made. But then, he could do no other. That was precisely himself. And as every student knows who has ever come into contact with him over the last eighteen years, this honesty and justice filled every corner of his personal relationships. Truly and indeed, the Lord knew his servant.

On the twentieth of September, 1945, the Naracoorte "Herald" reported a well-attended meeting in the Naracoorte Town Hall in the presence of the Hon. T. J. Playford, the Hon. J. L. Bice, M.L.C., and the Mayor of Naracoorte. Having spoken at some length, the young oncoming Major Cowan delivered himself of a resounding platitude. "I have formed my own idea," he said, "of what should be a reasonable state of Society — no order of society was worthwhile unless within it every individual was able to develop his full capacity and talents for the benefit of the community." Could we not say that it rested with the Third Warden of Trinity in recent years to give his life to put meaning into that statement and to leave behind him a blazing example and a profound encouragement to us in times when good examples are at a premium and when all strivings for perfection, except of the athletic sort, are regarded with the utmost sus-

picion. Thou, O Lord, knowest thy servant, but the question is, did we?

There is much talk in Christian circles these days about the witness on this or that frontier of society, but, alas, true to our pluralistic condition, we will go on trying to associate it with some specifically Christian organisation or movement. We want the real thing— Christians transforming secular society — but when we see it we hardly recognise it. It is not embodied in a report to Synod, and so it tends to lie outside our experience. Ronald Cowan was the ideal frontiersman; he combined two of the rarest gifts — wisdom and resolution. He was almost always right and he stuck to his guns whatever the personal costs. But the wondrous thing is that this sprang from and was fed by his faith in God and in His Son, Jesus Christ. His religion was undemonstrative in everything that did not matter. In matters of the greatest importance it was the reason of his existence. His regular Chapel witness alone was a silent example, but few outside College realised that he received Holy Communion three times a week with a regularity which shamed the more overtly ardent. Of his last days I shall not speak, except to say that to the end his faith was unwavering; and let it be clearly said that if anything gives meaning to this extraordinary life, it is the faith of the man himself and his clear and unequivocal response to the task to which our Lord Himself had called him and to which, in the strength of God, he gave himself without reserve.

His mortal remains are with us in the Cathedral, but shortly they will be removed and taken to Trinity College, where they will be incorporated into the fabric of the Chapel near the place where he worshipped — which is, of course, a sacramental sign of an even deeper incorporation — not merely into the building but into the lives of hundreds of students spread all over Australia and indeed all over the world. In the secular world his death is a disaster: in the divine reckoning it is a triumph — and in the context of the life of the Holy Church we can bear it, fortified by the presence of. Him who died and rose for us all, our Resurrection and the life of all the faithful. Truly, Lord, thou knowest thy servant: may God grant that he may know Thee ever more perfectly, until we may be united in the bond of peace, in the unity of the faith, and in the perfection which He wills for us.

Those of us who were in College at the beginning of 1946 knew that Dr. Behan was to retire from the Wardenship before very long. In the last week of first term we noticed a figure wandering round the College with Dr. Behan, and we realised that this must be his successor.

There was the usual end of term dinner, and that was the first occasion at which Cowan formally appeared before us. Behind him, on the wall between the paintings of Leeper and Behan, someone had strung up a small photograph of Cowan — in army uniform, I think— and beneath it the legend "Postera Crescam Laude."

"Wisdom is not, as knowledge is, something which can be directly sought and acquired. Like many other desirable things, it is a byproduct; it is the fruit of balanced development." So Cowan wrote in his brilliant Stawell Oration for 1961.

Wisdom was, in fact, one of the main characteristics of the late Warden — "perhaps the wisest of all my students," wrote G. V. Portus in his autobiography. It was this characteristic which induced so many organisations to make use of his services and which, from the beginning of his time at Trinity, enabled him to direct the affairs of the College so well.

I must confess that Cowan's wisdom was not so apparent to me when a student as it afterwards became. Perhaps it was the same for others, for he seldom sought out students and was not often seen in their studies — except after formal dinners, when he would drink large quantities of port, quite unperturbedly, and then go off to play one of his quarterly games of billiards.

But Cowan had an uncanny knowledge of his students and of what was going on in the College: his sources of information were not obvious, but the most undistinguished of reticent freshmen would be pretty much of an open book to him. He had an amazing knowledge, too, of those who had been members of the College before his time — and not merely of their Christian names, the more sonorous of which he loved to roll around his tongue. The names he might have learned from prolonged study of the College roll, but he knew much more than their names: information as to their academic and subsequent careers and their characters could be produced whenever appropriate.

Unlike his predecessors, Cowan was never faced with the problem of keeping up the numbers of men in College: his problem was to select those who were to be permitted to come into residence. It was no doubt his consciousness of the demand for places in College which led to his somewhat intransigent attitude on matters of discipline and his somewhat ruthless attitude to those who did not employ their talents to full advantage. As he put it in his Stawell Oration, "admission to a university is a privilege which ought not to be wasted on anyone who cannot or will not use it well."

How much more still might Cowan have done with his talents had he been with us for another twenty years.

PETER BALMFORD.

It has come to me as something of a surprise to realise that when I went up to Trinity at the beginning of 1951 Cowan had been Warden only for five years. We of course knew that he had only been Warden since the end of the War, but the impression one got was that things must always have been so.

This quick assumption of command was now to be carried over into a rather different College. For in 1951 the era of the ex-servicemen had virtually passed, though a few remained to exert a noticeable influence. The College still held its numbers at 120 (the number which the Warden regarded as the deskable limit for a residential College) and no new buildings had been added; freshmen were still found in the Wing and in Bishops'; not even in 1954 did there come that final, abysmal break with the past — a freshman in Upper Clarke's. But the men themselves had changed.

The setting therefore was that of a new kind of membership of the College, though in its old setting. Whether things would work out was, perhaps, in the Warden's own familiar phrase, "an open question". Indeed, when we met him as a group for the first time at the gathering in the Common Room at the beginning of the year, there was no doubt that he so regarded it: standing there in that familiar stance, gown-enveloped, the hands crossed in front of him, the head dropping regularly to one side as he spoke, he made it clear that where we went from there was up to us. But

he pointed out that of the previous year's Wooden Wing only four had lived to tell the tale — and left it to us to draw the appropriate conclusion. This was his method, and in following it up he moved with assurance. In striking a balance between what was and what was not permissible, and even more, knowing when to permit on some occasions activities that could not be accepted on others, the Warden was outstanding. There are no doubt those who expect close supervision of his charges from a College head. Those of us who went through Trinity under Cowan know better and we do so because he applied successfully one of his dominant principles, namely, that a man of University age should be expected to think and act for himself, with the corollary that if he makes mistakes then that is a good way of learning and if, on the whole, he succeeds, then he succeeds because of his own efforts, deriving in turn considerable satisfaction from so doing. If of course the axe had to fall, it did. But he always seemed to know the right moment, and because he did in fact have a close knowledge of his men and showed a keen and sympathetic understanding of them, I believe that he dealt justly. It is not on the whole difficult to be a disciplinarian; it is not easy, as the head of a community, simply to guide, inform and watch, but this I believe he did, and in so doing gave men a chance to be masters of themselves.

The extent to which he knew and cared for us was further demonstrated when someone went to him for advice, or simply for a friendly talk, in the years after leaving College. I know that many people did seek him out, and they found in him a source of wise counsel and encouragement. Here again he knew his men, not only from their College days, but also from following their steps after they had left College. The advice he gave was the more valuable because, while always sympathetic, it had sometimes to be frank, a feature which was always apparent in the references he gave. These were much prized, because they owed nothing to a desire to please, and all to a desire to advance the merits and define the limitations of the whole man, in the interest of his proper advancement.

To stop at that point might suggest that he was simply a brooding figure in the background, and this he assuredly was not. He was, above all, a friendly man, and his genial good humour a iov to all. How much we all looked forward to his speeches at College din-

ners and to his conversation and company over a drink afterwards in someone's room. Here he was a prized guest: I remember him particularly in a room in Upper Clarke's on one such occasion, the centre of fantastic conversations as a press of people surrounded him, delighting in his wit and humour. One remembers small things, too: giving the key to that incredible song at dinners with a resounding "Fill ...". Also his billiards match against the Senior Student after a Valedictory Dinner. The determination of a beaming Warden bending (not too easily) over his cue amidst a roaring company of delighted spectators found him at home with his men in the College he loved.

Those who arrived in College as undergraduates at the time of his appointment, mostly as ex-servicemen, perhaps might have expected easy manners from a man of their own age. To my era he was a man twenty years our senior, yet he came among us as a friend, and it is as a very true and happy friend that we shall most remember him.

"The gods from afar look kindly upon a gracious master."

—"The Browning Version", T.C.D.C., 1951. ROBERT TODD.

I remember that before I went for my first interview with the Warden of Trinity in 1953 I furtively looked up the word "warden" in the Oxford Dictionary. I had an idea that the person who signed himself "R. W. T. Cowan, Warden," on my letters must be a superior sort of secretary in the institution. Those of my friends whom I asked for information seemed equally uncertain, and those of my seniors who would have known I didn't dare to ask. The dictionary failed me, saying simply sentinel, guardian, air-raid official, and then listing a number of obs. and arch. senses, giving as examples of these the Wardens of the Marches, the Cinque Ports and Merton College. Then I was unable to find the Warden's office, and had a bizarre encounter (which did nothing to quieten my nervousness) with a florid, grey-haired man in a maroon jumper who left me with a clear impression — which he tried in vain in future years to restore— that it was he and not the Warden who ran the College. But uncertainties disappeared when I at last found myself face to face with Ronald Cowan: nothing here to suggest either

a menial or the eccentric holder of an obs. or arch. office. He was quiet, efficient. with a twinkle of humour behind the spectacles, and had a way of making you feel he was treating you as an equal and as a potential friend; he had a courtesy and a poise that was at once flattering and enviable to a schoolboy; a cool understated way of talking that made you think that Trinity was going to be a very adult and sophisticated place indeed. There was of course a good deal of false and often objectionable sophistication among the Trinity gents, a feeling of elegant exclusiveness that tended to show itself, for instance, in the adoption of rolled umbrellas and even, in one case, of spats, and which was understandably irritating to the non-collegiates. But although Cowan tolerated these, as he did most other kinds of mild experimentalism, his own form of sophistication was quite different; it was really that of the plain man, fluent, well-informed, highly competent; proud and fond of Trinity, but also keeping fresh his contacts in the outside world.

Dignity and traditionalism, of course, he had; he was ready, too, to "play the Warden", knowing that this was expected and enjoyed; but the role was accepted with good humour and probably some wryness. The habits and mannerisms are familiar enough: the stoutish figure pottering with a pair of snippers amongst his rose-bushes, or quite tigerish with excitement on the bank behind the goalposts; his solemn sweep out of chapel (memorising the absentees); his comfortable after-dinner speeches in laconic Rotarian style; his fastidious "good mornings" as he passed you on the college path, groups of students goodmorning-ed by name and in order of seniority, his greeting changing promptly to "goodafternoon" as the Ormond clock struck twelve. I remember him beaming with delight after the first nights of some of the successful Stowell/ Sargeant/Munro college productions of those years (there was a line in "The Winter's Tale" about "the warden's pies" which, probably for the first time in history, audiences seemed to find amusing); or again, re-telling some story about Chester Wilmot as he stood, coffee-cup in hand, with his back to the common-room fire, occasionally fetching another name and anecdote from the honour-board above, and concluding inevitably, "So . . . so," with a slightly sad smile for things past. Most of this was more than play-acting; it was plain to see how emotionally involved he was in life about the college.

There was a smallish radical group in the college, some of whose members later left for a new life at the founding of International House, who thought Cowan followed Oxford protocol and tradition too closely. Sometimes, indeed — as in the cases of compulsory chapel and formal dining with its black ties, set places, rules and fines — he justified Trinity practice by an appeal to Oxford practice: which in these cases had been long discontinued at all Oxford colleges. I don't think anyone realised this, although I remember there was nearly a nasty showdown during the visit of the President of Magdalen College in 1956, when questions were asked about religious attendance in Oxford. Perhaps Cowan knew that many people in Trinity enjoyed the novelty of tradition; perhaps the traditions had to be slightly exaggerated to allow them to exist at all. But some of this "traditionalism", if it can be called that, must have been the legacy of his deliberate policy in the post-war years (of which he spoke rarely, but with a nostalgic gleam) to impose a regular and orderly pattern on the naturally anarchical and haphazard day-to-day life in college; a policy which he found it convenient to continue in the softer years of the mid-fifties. His views on chapel were based of course on natural piety, but he also believed that to pursue an academic life, it was necessary to appear shaven and clean at a regular hour in the morning, no matter how taxing the previous night had been. His own habits were always so regular that it was said that the late riser could always tell when it was lunchtime by watching through his curtains for the Warden's punctual exit from the Leeper building.

The Warden's rules of discipline were sensibly few; but on these he was quite firm and quite predictable. An elderly student who strolled down the drive with his fiancee at five past six was once given a cool "good-evening" from the Warden and a five-pound fine the next morning. Severe enough, but it was agreed that he had no one but himself to blame. Sometimes, however, rules had to be invented to fit less predictable occasions. Once, for instance, someone had the highly enterprising and imaginative idea of running a hedge-clipping syndicate. The idea was to hire a large body of men with their own equipment, send them out to needy garden lovers in Malvern and Toorak, and take a large fraction of the profits without having done more than simply organise the scheme from a college room. An advertisement ask-

ing men interested in this work to call on Mr. at Trinity was inserted in Saturday's "Age." By some bad luck (was it?) all fortyseven applicants, many of them derelict and unshaven, lost their way inside Trinity and finished up knocking at the front door of the Warden's house. Hedge-clipping dropped out after that. The Warden also gave the occasional sharp talk to the college about the danger of neglecting one's work; the remarkable academic record of the college during these years probably shows not so much that the talks were necessary and effective as that the Warden had picked his entrants with a good deal of shrewdness. The most memorable of these occasions must be well known. It coincided with a "Farrago" attack on the new Memorial building then near completion in the Bulpadok; at the same time, not many people wanted to volunteer to live in the building the following year. The Warden gave the routine warning that those who did not get down to work pretty sharply might find their places in college next year in jeopardy. And "Jeopardy" the new building was promptly christened. Within a day or two the Warden himself was heard blandly refering to the building by this name.

I had better say something about the Onto incident, which was a feebler joke followed by an elaborate rescue operation. It all began when someone added a grammatical correction to a typed notice which the Warden had posted. The notice was at once removed, and another put in its place, reading (as it were): "Gentlemen who deface notices posted onto this board will in future be fined." That notice, and particularly the spelling of the word "onto," drew some comment that day. During the night, the inevitable happened: someone foolhardily scored through the word "onto" and wrote above it in a neat hand "on to." The axe fell hard: the victim was, after a difficult search (which involved, rather dangerously, the posting of further notices), found and heavily fined. As usual, the Warden was clearly within his rights, and not to have acted would have been pusillanimous; but both the OED and a natural love of stupid courage told everyone that the Warden had to be wooed back into a position where he could relent with dignity. A massive Festschrift was compiled with essays by divers hands on the etymological, phonetical, literary, historical, philosophical, and legal aspects of the variant spelling; the essays were bound

within a cover that was inscribed ONTO. and that divided down the middle between the "nand the "t" in order to preserve the ambiguity. The Warden was pleased, reduced the fine very considerably, and had the volume placed in the College archives, where I believe it still is..

On the whole, the mid-fifties were quietly academic years in Trinity; perhaps the Warden's least harassing time during his tenure of office. The last of the ex-servicemen left at the end of my first year; Jeopardy was opened the year after I left; the college was still relatively small, and we missed the administrative complications of the late forties and the expansion problems of the late fifties. But I think they were years that Ronald Cowan enjoyed as much as we did. It is hard to think of Trinity without him.

IAN DONALDSON.

Unlike the Dean, who was reported to have been paid the compliment of being asked for his father by the parents of a freshman, there was no shadow of doubt in my mind as to the identity of the man behind the desk when I first entered the Warden's office as a freshman in 1957.

The impression one got was that of a rather aloof man, and one felt that this was the closest one would get to him for some time. In fact, this initial impression was true; the Warden made little attempt to get closer to the members of the College — it was up to them to get closer to him.

Unfortunately, many members of the College did not appreciate that this was what the Warden wanted them to do, and hence, although he knew a tremendous amount about each man in College, the element of a personal relationship was missing in many cases. I feel that this contributed a good deal to the misunderstandings that arose from time to time between the Warden on the one hand and the members of the College on the other.

When someone did take the initial step towards a more personal relationship, usually by inviting the Warden into their study, they found him excellent company and able to converse with, and put at ease, even the freshest freshman. I consider myself privileged indeed that I had the opportunity of getting to know him well in my later years

in College, and I frequently went to him for advice or just for plain good company.

I cannot pretend that I always agreed with the Warden's decisions — frequently I did not — but it was a great help to learn that he did not allow such antipathy on College matters to descend to any personal animosity. His advice on personal matters was always sound and practical, and those who troubled to seek it found their effort well worth while.

His interest in all facets of College life was genuine and unfailing; he regularly attended meetings of the various Associated Clubs, and was always present to support the College during sporting events.

One of his qualities which everyone appreciated was his ability as an after-dinner speaker: his speeches were witty and wellconstructed — although I did hear Mr. R. K.

Todd on one occasion reprimand him for pruning the garden of his oratory with a pair of non-sequiturs.

He achieved a tremendous amount materially during the last seven years, as a number of buildings and extensions witness; but the most important part of the yard-stick for measuring his success as a Warden is the influence he had through "The College" on each of us who was there during his Wardenship. You cannot divorce "The College" from the Warden, because the College is what he allows and moulds it to be. We may each think we were influenced more or less, but I think we would all agree that our stay in Trinity under the Warden gave us a great deal of pleasure and helped prepare us more adequately for our chosen careers.

MICHAEL JONES.

T.C.A.C.

Chairman: Dr. J. R. Poynter.

Senior Student: Mr. J. O. King.

Secretary: Mr. P. F. Druce.

Treasurer: Mr. C. Selby-Smith.

Indoor Representative: Mr. P. L. Field.

Outdoor Representative: Mr. R. H. Treweeke.

1964 will go down in the minute books as the year of the College horse. After much hot air, the terms of reference for a sub-committee were agreed upon, and the sub-committee (as agents of the Clubs) ventured to WrightStevenson's saleyards at Newmarket for the annual Grand National Sales. There the horse market was found to be buoyant, and at the end of the day, despite furious bidding from Stan Spittle, the hammer had failed to knock a horse our way. Back to the "Sporting Globe", and here was found a great bargain. At the time of writing John King and Peter Field are under instructions to conduct a medical examination on the brood mare, Sky Blaze, who is in foal by Ottoman, to try to explain the bargain price of 250 gns. for this package deal. It will be with relief that gentlemen learn that negotiations for the horse Flying Lily — who drew the Books to Juttoddie — have fallen through. So, so far, no horse .. . but the sub-committee works relentlessly on.

The T.C.A.C.'s biggest expense this year has been on the Common Room, where, unfortunately, improvements must be slow. This is because, first, to furnish a common room properly costs about £4,000; second, a new common room is planned in a building to be constructed at the geographic centre of College — the cricket pitches; third, as no benefactors have been forthcoming, the cost of improvements rests primarily with the T.C.A.C. Fortunately, the College Council usually subsidises half our purchases. Last year the Clubs spent about £300 on curtains, rewiring and painting. This year we have spent £260 on chairs and have a new television set by courtesy of a thief and the Northern Assurance Company. The next items to be considered are probably rugs, magazine racks and small tables. Obviously sums of £250 to £300 per year can bring about

a satisfactory result only slowly, but perceptible progress is being made.

Financially, the Committee has tried to defy Parkinson's Law. The handling of major financial items has been put on a sounder basis: the Ball is now held at the Palais under a scheme whereby we should not incur a loss; the play (under philosophical finance expert, Frank C. Jackson) showed a profit; the printing of the "Fleur-de-Lys" will be carried out by a different, and, we hope cheaper, company; and expenditure on rowing has been minimised by an opportune purchase of a new eight. With no bungles in these matters, we have spent more on the cast party, more concert tickets, milk at the College auction, a greater range of magazines, improvements to the tennis court and perhaps even a new washing machine. The effort in defying Parkinson has, we trust, been worthwhile.

PETER DRUCE.

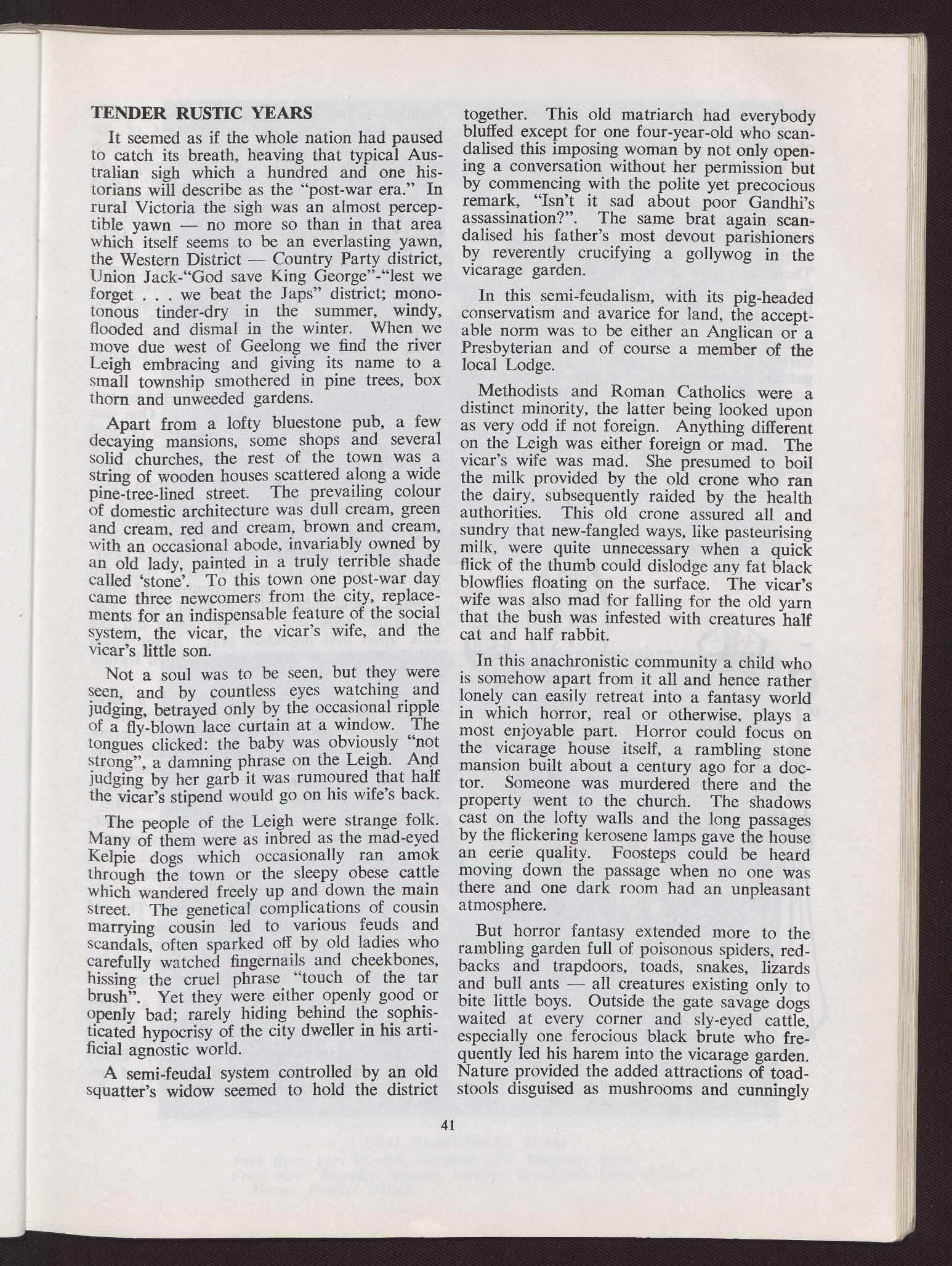

Senior Student: Joan Rowlands.

Secretary: Geraldine Morris.

Treasurer: Colette Cock.

Assistant Secretary: Helen Ford.

Librarian: Judith Whitworth.

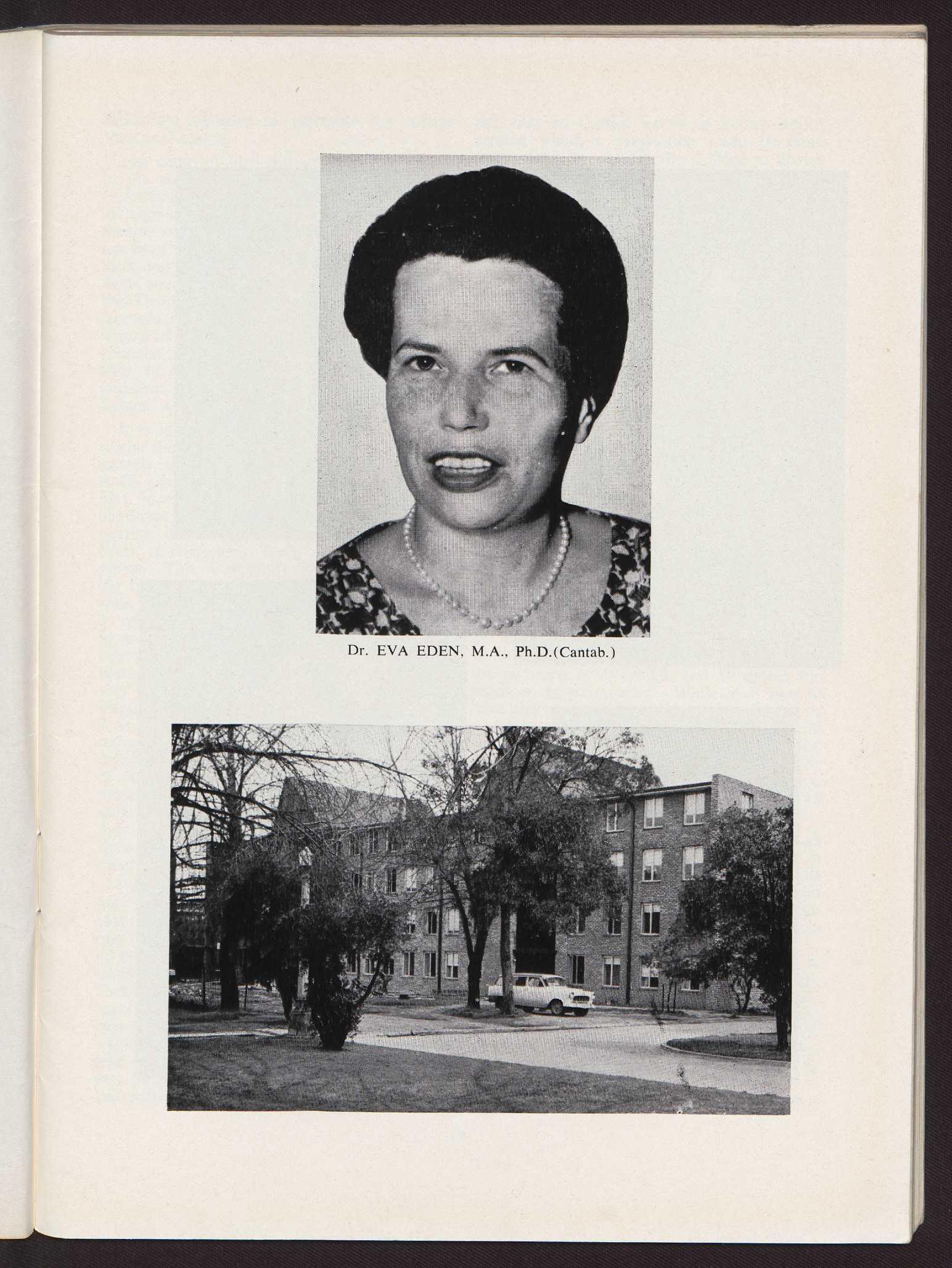

This year we have welcomed Dr. Eva Eden as our new principal. She has done much to consolidate the finances and administration of the College, the main result being the introduction of Nationwide food caterers to take charge of the kitchen. The results, as old students will testify, have been improved standards and smoother running.

Another part of her influence has been the number and variety of guests on High Table. During the year we have been privileged to entertain Mrs. Fader, wife of the Thai consul, Mr. and Mrs. Peter Balmford, the Warden of the Union, Mr. Sinclair-Wilson, and Mrs. Sinclair-Wilson, and the Heads of other University colleges.

At the end of second term the College held a dinner in honour of Dr. Margaret Blackwood, Chairman of the College Council, who was

awarded an M.B.E. in the Queen's Birthday Honours list.

We wish to welcome Miss Aitken back from her research work in the United States, and also Miss Dwyer, the only newcomer to High Table this year. Dr. Knight returned to the U.K. for a holiday in June, and we hope that her absence is only temporary. Miss Powling also left for foreign climes, and at the end of the year we shall be sorry to lose Dr. Manuel, who is returning to Malaysia, and Miss Foot, returning to the U.K.

The informal CRD in second term was held, for the first time, in the Common Room and not, as previously, in the Dining Hall. This proved to be a successful shift of venue, as its smaller size led to greater intimacy than was permitted by the vast acres of the Dining Hall.

This year, under the auspices of the Chaplain and the guidance of the Assistant Chaplain, a Chapel Vestry has been established, J.C.H. having two representatives on it: Jean Kerr and Kathy Bakewell. Its object is to increase lay participation in the administration of the Chapel and promises well for the future. 1964 has been a year of many changes. 1965 should see these changes consolidated and improved.

Dr. Eva Eden came into residence as Principal of Janet Clarke Hall at the beginning of the academic year 1964, from St. Catherine's College, Perth, where she had been Warden since 1961.

Dr.. Eden was born in Budapest, Hungary, and was educated there and at Kendal, Cambridge. She took her M.A. and Ph.D. at Cambridge University, and remained in England for a short time as Scientific Officer to the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries.

Dr. Eden then came to Australia, where she was Vice-Principal of Women's College at the University of Sydney, and a Senior Lecturer in Chemistry at the University. After spending some years in Sydney, she went to Perth, where, while Warden of St. Catherine's College, she lectured part-time in Biochemistry at the University of Western Australia.

Li addition to her academic interests, Dr. Eden is fond of skiing and is a Soroptimist.

We are fortunate in having a person of such varied abilities and wide experience as our new Principal at Janet Clarke Hall.

A notable development within the life of the College this year has been the formation of a Vestry to manage the affairs of the Chapel. Formerly, all responsibility for the running of the Chapel, in things ranging from the replacement of a light globe to decisions with regard to the time and form of College Prayers, has been in the hands of the Chaplain alone.

The newly-formed Vestry is designed to act as a kind of sounding-board whereby something of the preferences and desires of the colleges concerning the life of the Chapel can be aired. During the course of the year the Vestry suggested that some change should be made in the form of College Prayers, and that on Tuesday evenings, after dinner, some sort of informal hymn singing, particularly with modern music, should precede a short talk. The Vestry also decided that College Prayers of the old type should be abandoned on Thursday evenings, and that students should be encouraged to attend daily Compline, particularly on Thursdays, when Compline is preceded by a short devotional talk.

The Vestry has elected a secretary and treasurer and has taken over the banking and distribution of alms, the purchase of minor requisites, and the responsibility for matters of Chapel maintenance.

All this is designed to admit the worshipping community at large to a share in the administration of the Chapel, and to facilitate the influence of the Chapel in the life of the colleges.

The Assistant Chaplain, Fr. John Gaden, was ordained to the priesthood on the Feast of the Transfiguration, Thursday August 6. Acting by letters dismissory from the Bishop of Bathurst, Bishop Felix Arnott, in his first ordination, presided at the laying-on of hands and celebrated the Eucharist. The Occasional Sermon was preached by the Chaplain. Singing was led by the College Choir, which performed James Minchin's "Missa Veni Creator," a Byrd motet, "Sacerdotes Domini," and the Gelineau setting of Psalm 136. Fr. John celebrated the Eucharist for the first time the next day, the Feast of the Holy Name. Many visitors were present, despite the early hour (7.30), and shared with the College in this, its first chapel ordination.

They seemed a crew of some distinction, paddling lithely down the stream. And after, I heard someone say, "You know, we were unlucky to lose the final." It warmed me to hear thus expressed the College's traditional interest in intercoll rowing. But this is only a half a story.

I picked myself up from the floor, removed M 's untasty foot from my mouth, and was immediately assailed by premature crisis. Luckily M had more money.

On the river all a-quiver centuries later, how shall I describe the sensation of being fitted into a rowlock and backwardly plied in a forward direction? Our boat moved smoothly away from the riverside and into mid-stream. Minutes later, the crew now aboard, we jerked frenetically downyarra.

The water ingredient in the river lapped hopefully against the oaken panelling of our shippe. Boats aligned, muscles strained, we stood there knee-deep in will-to-do-as-well-aswe-can, for better than that no-one can do. The starter raised his gun and drained it at a draft.

Bang, it seemed to say, mocking my discomfort and my middle-class originals. A dull thud (aren't they all?) from upriver indicated the untimely demise of the timekeeper. And the shrilly-protesting whinny of the starter, "real bullets are louder." Listing now lynxlike the garlick prow departed pursuant to what we "hat ter beat."

Aftly grunting, stroke after stroking, we halted for a refreshing moment of truth. Should we go on or recant now (or later?)? The cox. I think, forced our decision, his watery voice scarce audible during the keelhauling. "Yes," he said simply. Thus reassured, we swept ahead amidst a flurry of quaint nautical oaths. I was going to "gunnel" you; you swore to "hang me from a three-foot yard-arm"; and we were mutually agreed that M would have his "main bracers spliced at two bells." Blueprint of victory? Prototype of triumph? Finally, I feel that mention must be made of the second half of the race, without whose untiring efforts we would surely have won. Posterity will celebrate this: we mightn't have won the race but at least we didn't have the moral victory.

MICHAEL SALVARIS.

There was movement at the College, for the word had got around

That the young sophisticates had had their way,

And were bringing their own liquor to help raise a thousand pound; So all the soaks had gathered for the fray.

There were folksingers to listen to and sausages to burn, There was Buckland with his violin and band; The fairy lights were dancing and the tutors took a turn,

And every darkened corner there was manned.

It was all in aid of Janet Lady Janet Lady Clarke, For she had to have a face-lift and a wash,

So the ladies of the College brought their friends and made their mark

On the quadrangle, Hall floor and brandy squash.

After squealing entertainment which continued until twelve,

An hour when all good girls should be asleep, Most departing guests departed, leaving us to count the spoons

And the young men raking rubbish in a heap.

The dance it was admitted was a fabulous success

(At least it said so on the social page), And we raised a lot of money, at the price of some distress,

So the Hall will be a pretty painted cage.

There is a danger that music may change from an activity to a consumer good. Soothing Muzak, designed by industrial psychologists and electronic engineers, is piped through our factories and office-buildings, teenagers are glued to their pulsating transistors in a drugged stupor, while concert attendances fall and talented musicians leave the country in despair.

In a small community like ours there is more opportunity for wider participation in music: we may be succeeding in this. Two good chamber music groups arose in College this year. The folk-singing trend of the last few years has reached the stage where some people are beginning to regard it as an alarming cult. The many strum away contentedly;

the talented few perform at Union nights and in local coffee lounges; the makers of fifth-rate guitars reap enormous profits.

Viva Jim Minchin and the Most Men! This year we saw the world premiere in the Chapel of a Jazz Mass, the Missa Centralia, written by Jim and orchestrated by Peter Gerrand. It is intended that this should become as familiar as the traditional Merbecke setting — at least in the College Chapel. This is supplemented by the jazz "Min Hymns", which were published this year in a booklet. Both the Missa Centralia and the hymns have received wide publicity in papers ranging from "The Anglican" to the Melbourne "Truth", and the choir and the Most Men have led services at a number of suburban and country parishes.

At this year's College Concert, the large number of individual performers and small chamber music groups made it unnecessary to invite a guest soloist. Organists, pianists, stringists and singists made up an appreciated programme. Of special interest to connoisseurs was the Mozart Horn Concerto, K.495, played by the traditional Field and Alexander duo.

The first meeting of the T.C.A.C. readily agreed to buy more concert tickets. We now hold four tickets in each of the A.B.C. Celebrity Concert, Youth Concert and Musica Viva series. This has enabled members of the College to hear a wide selection of high-quality performances.

This year the choir has introduced new masses and anthems by several College composers, and has given performances by public demand from St. Kilda to Seymour. Despite the mental anguish of our choirmaster, "unable to decide whether they should perform great works badly, or simply put mediocre works to death", there is no doubt that it has been chiefly responsible for the strength of the singing of the congregation.

Finally, the informal Sunday Salons, which started last year, have continued, but there have been fewer of them. Four have been held — a recital by pianist Geoffrey Saba and 'cellist Richard Smith, an "intimate entertainment" by Messrs. Field and Swalexander, a recital of Latin poetry with appropriate mood music by Jim Minchin, and a great Folk Sing. They have all been well-attended and popular, but the problem of finding performers has still not been solved.

HAL COLEBATÇH.

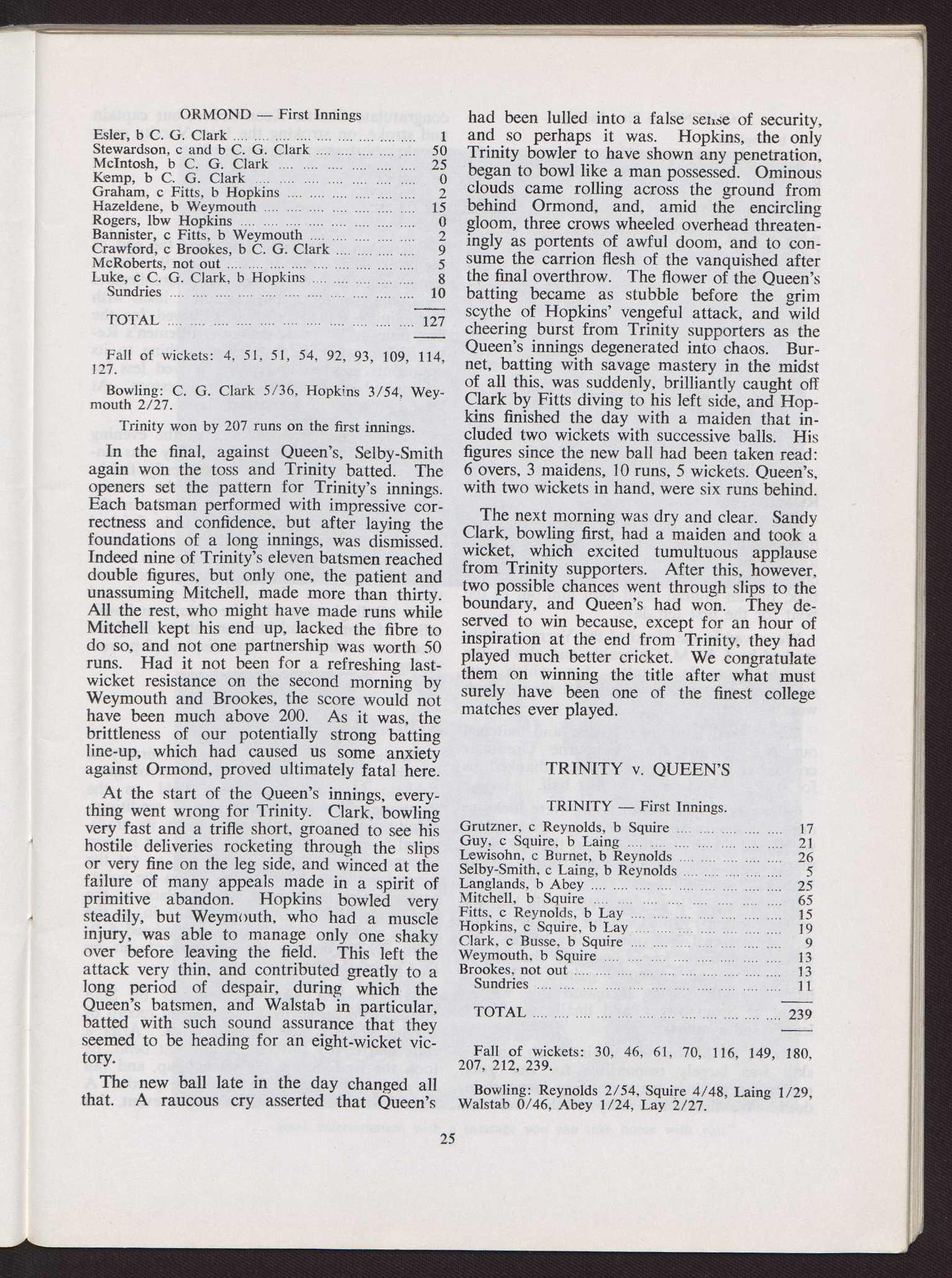

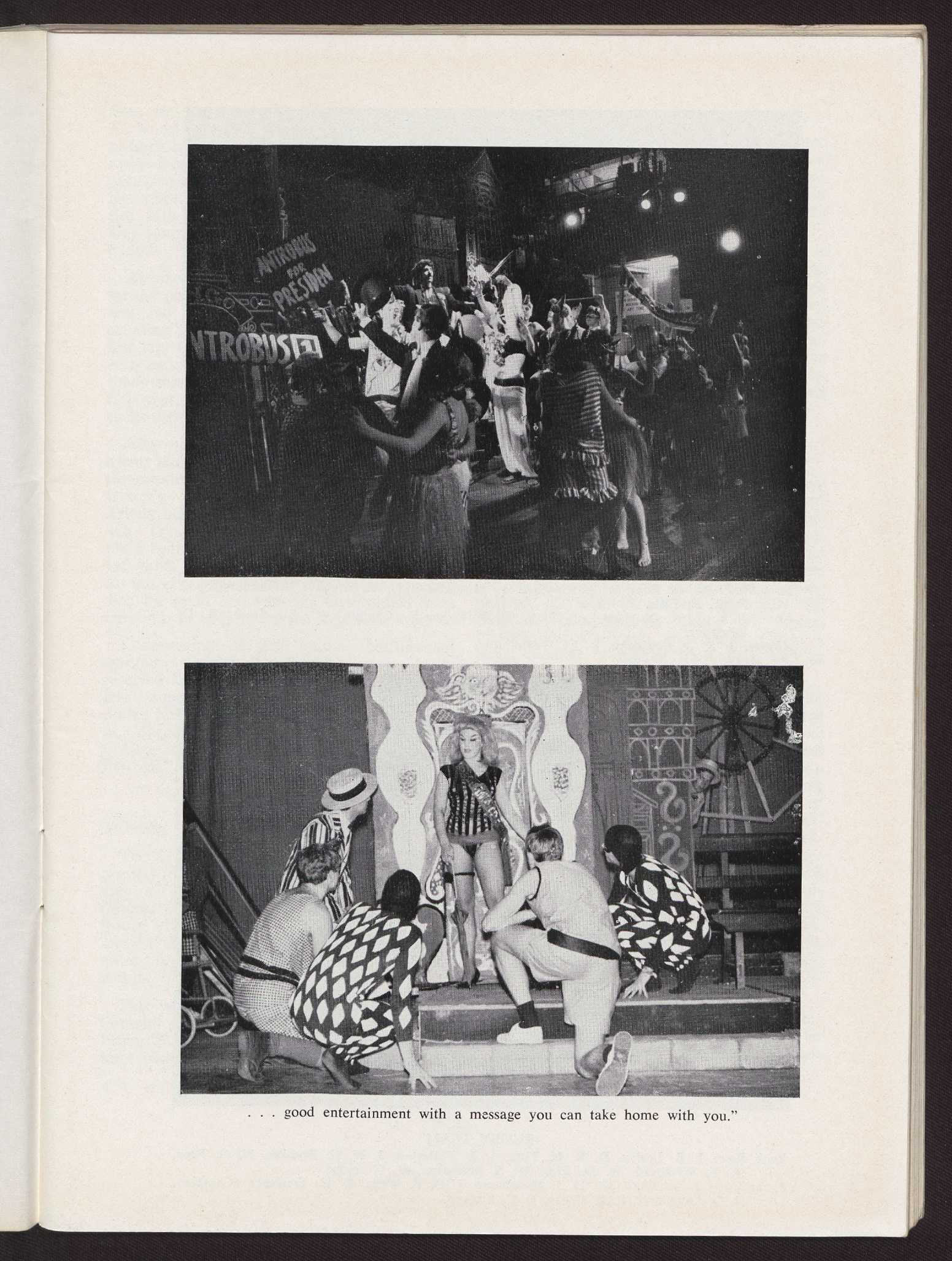

To an incurable romantic for whom the past has a magic the present can never regain the modern College play is not always a happy event. Perhaps those magnificently mounted productions of "Hassan", "The Tempest" and "The Winter's Tale" were not as substantial as they seemed at the time. Perhaps the suspicion one retains that they were a shade too static is true. But one may wonder whether their recent counterparts will be as affectionately remembered ten years hence as something worth doing and worth having done.

The trouble, it seems, is with the choice of plays. One year's disaster with the most difficult of the Shakespearian chronicles should not deter the College from attempting "Twelfth Night" or that most delectable of comedies, "As You Like It". This year's offering could safely have been put to rest with the war, or, at the latest, with Sir L. Olivier's peace offering to our war-unshattered nation. Its attempt to range to and fro through adventures of some five thousand years only served to anchor it the more to its own time. True enough, it had five or six parts to test the mettle of the most ambitious of College actors and actresses and a few dozen to provide tickets to the cast party for the others. But the success of the performance was in the teeth of the play itself. Could anyone, moved by the power of Mr. David Elder's and Mr. Carrillo Gantner's Cain and Adam scene in the third act be unconscious of the thinness of the material? If a voice in the wings says "yes", let him answer whether the spell held when the clock began to strike and the pages of time opened to have their say. Could they take the second act, with its anticipation of another event in Atlantic City, as anything but an excuse for Miss Eva Wynn's and Miss Helena Hughes' hilarious turns and the display of pyrotechnics at the end? Could anyone imagine that the tatty device of a play within a play of the first would seem to be the latest thing in baffling theatrical? Let the Dramatic Club worry less about what the (or a possible) producer wants to do and place a firm embargo on bad plays.

More is the pity that so much excellent work should have been revealed. Mr. Gantner, as the indomitable Mr. Antrobus, whether inventing the alphabet or simply pulling the ranks together and smiling through, towered over

the play as the author intended he should. Mr. Antrobus must communicate to the audience warmth and magnanimity, and this Mr. Gantner abundantly did. He was ably abetted by Miss Wendy Cameron as Mrs. Antrobus. After an uncertain start, Miss Cameron's performance gained in confidence and conviction. The play needs a strong Mrs. Antrobus, for she is not only the rock of her family but of Mr. Wilder's homely thought. Mr. David Elder and Miss Jo Rintoul were impressive as the Antrobus children, Henry and Gladys. Mr. Elder in particular showed versatility and dramatic strength of a high order in the transformation of Henry from a sulky schoolboy to the snarling Nazi of the last act. One's only reservation amongst the principals concerned Miss Hughes' Sabina, a treacherous part at various times taken by actresses of such diverse talents as Miss Tallulah Bankhead, Miss Mary Martin and Miss Vivien Leigh. Unfortunately, Miss Hughes was even less convincing when she stepped out of the role than within it.

As always, the bit parts gave pleasure. One remembers Mr. Peter Field doubling the professor and the telegraph boy, Miss Wynn's fantastic fortune teller, Mr. Russell Jackson's pet dinosaur, Mr. Kenneth Griffiths' baby mammoth, Mr. Paul Nisselle's singing and, for the collectors of Mr. Peter Elliott's characters, a vignette of an American broadcaster.

The production was once again in the hands of Ronald Quinn.

J. D. MERRALLS.

Recently the College plays have come in for some unfair and inappropriate criticism. It is the sort of criticism that devotes itself in all its ingenuity to explaining how the producer and the artist could have done something quite different much better, how the play could have been improved out of all recognition if the cast had done what they never intended to do.

Sadness is expressed in several quarters, and in several columns, past and present, of "Fleurde-lys," that the recent modernism in College theatre — "The Beggar's Opera" and "The Skin of Our Teeth" — has contributed to a lowering of theatrical standards in this College. It is suggested that Trinity is sadly out of step with other undergraduate societies and colleges in its apparent intention to give everybody a go, and cram as many people on to the stage as possible, regardless of the audience. An annual college outing to the theatre will hardly

"Oh why can't we have plays like we used to have . .

entice an audience to patronise the college theatrical season.

The cause of such disparagement originates in the choice made in recent years of plays containing a large cast. The recent experience in large-cast plays is an innovation in College theatre which, since "The Dark of the Moon," has been met not with appreciative encouragement but with disapproval, in spite of the obvious success of such plays. The College and the Theatre can no more pander to the preferences of the audience than it can to the whims of Critics: it must feel itself to be unconfined. "The Beggar's Opera" and "The Skin of Our Teeth" showed both that the audience can be outraged, infuriated and delighted, and the Theatre kept alive.

It is in connection with the appropriateness of the choice of play that a second issue arises, namely, the current vogue of anti-Shakespeare & Co. plays, which are no substitute for a good play in the classical tradition; the argument continues that one or two failures in Shakespearian theatre should not deter the College from re-attempting some of these masterpieces. This is certainly true and, of course, the College should, in the long run, put on a wide variety of plays, but no one should be so mistaken as to think that four years away from . the classics will disappoint the audience any more than it should disappoint us; and because the last three years have given three very good seasons, "Dark of the Moon", "The Beggar's Opera" and "The Skin of Our Teeth", it is surely insulting to read of the annual college romp to the theatre. Audiences were delighted with "The Beggar's Opera", in spite of its many short-comings. To those who prefer a lifetime of happiness with Shakespeare, I would say this: he who desires a lifetime of happiness with a beautiful woman desires to enjoy the taste of wine by keeping his mouth always full of it.

This anti-Shakespeare & Co. notion extends into the field of what is and is not a good play. "Pla ce a firm embargo on bad plays", one hears it said, but is there not much folly in the T.C.D.C. doggedly leaping into Greek tragedy, Shakespearian comedy, or perhaps "brutalistic" theatre with a characteristic disregard for reality, and hoping to make a success of it, without for one moment considering whether or not there is acting ability in College sufficient to meet with the demands of, say, Shakespearian comedy? With regard to this year's play, there were at the beginning of

the year no College actors of known ability around whom a production could be built; quite a risk to commit the College to Shakespeare in these circumstances. There is an impression being created by local critics that something Shakespearian is naturally good, and something even a little bit modern as being intrinsically sub-standard. It is no good saying Shakespeare is best three times a day after meals, and hoping it will be, and then gratifying it all by doing Shakespeare in April; it just does not work.

It is important to bear in mind the limitations and difficulties inherent in producing a College play. Trinity and Janet Clarke Hall are not always possessed of a rare handful of actors and actresses who have had notable experience on the stage, and for this reason the College cannot guarantee that each year its production will be of a similar vintage. Critics should not be surprised at gaps in College acting, rather they should be more ready to notice improvements in College theatre.

There is obvious disagreement as to the success or otherwise of recent College plays, and it is clear that the word success is being used ambiguously. Is the play made a success by the profit it makes from the public? Is it in satisfying the audience? Is it in satisfying the cast and the College that it was worth while after all? The premium on satisfying the audience is very high, and altogether too much to insure against. While it is nice to have the profit derived from the public, it is certainly no criterion of success. The secret surely is to make certain that the College, having fulfilled its obligation to the public by perfecting the presentation of the play it has chosen, should be thoroughly satisfied that all was done that could be done.

It is this manner of success, success from the point of view of those in the play and in the College, that is of prime importance. The College play has now become a College event similar in tradition to Juttoddie in that it implies and people expect this general involvement of people in. College in the play.

This article has been written primarily to clarify the alternative attitude to the College play, and to suggest that much of the published criticism has come from people all too distantly associated with the play. The College play is distinctly different from professional performances, and much could be achieved by critics recognising this.

JOHN OLIVER.

ELLIOTT FOURS

A Theological Approach

Circa 2 p.m.: Arrived. Lager broached. Sun out. Thirsty . . . not thirsty.

2.10 p.m.: Thirsty . . . not thirsty (etc., ad nauseam).

2.20 p.m.: At last the races start! ... 'bout time, too . . . —! Who's organising this — show? Oh. Nice day, Gal!

2.30-3 p.m.: Races ... thirsty ... quenched .. can't remember who's rowing ... shuddup an' go away!

3 p.m.: —! Look at Hone skolling all down the river. Good on you Geoff! Three cheers for Geoffrey.

3.15 p.m.: There goes Bainbridge Jr. with a pair, going the wrong way. It figures.

3.20 p.m.: Another — rigged crew! . . trust Rennie.

3.25 p.m.: Getting thirsty again . . . where did they get that cheese from? . . . Really! Mr. Fenton, really!

3.30 p.m.: WHO brought a football down? They should be . . . Here come the clergy. This'll set the tone!

3.40 p.m.: Get a load of Mr. Buzzard coxing a boat with Mr. Nankivell in the middle. Well, they couldn't put HIM at the end . . . er, "bow"? So that's what they call it? Thanks (smile) for nothing (mutter), you poor drunken ... (immediate penitential thoughts).

3.45 p.m.: Another — rigged crew! Mr. Stephen Larkins coxing, and Messrs. Pullen and Richards (very versatile coxes) at least KNOW how to row.

3.50 p.m.: The Larkins gang v. the Buzzard gentry . . . and the rigged crew wins! disqualified, that's better ... Quaff ... Quaff ... Go away.

3.55 p.m.: Mr. Larkins is swearing. Saith Mr. McPherson, "It's nasty, juvenile and petulent." Enlarge on that Mr. McP. "Next Elliott Fours — no football, no rigged crews, and the only prerequisite — sheer and utter incompetenshy at rowing!" Thank you, Mr. McP.

4 p.m.: Mr. Larkins tells Mr. Galbraith to go and...

4.5 p.m.: Messrs. Pullen and Richards howling and wingeing. ". . . and WE told Father Marshall and HE said ..." "Oh, shuddup, ya poor little . . ." quoth Gal.

4.10 p.m.: Mr. Larkins tells everybody to go and...

4.15 p.m.: Silly b—s still kicking the footy in the river ...—! I'm thirsty ... not thirshty now. Struth! The sunset already ... Mmm August? . . . That couple on the other bank don't seem to mind . . . Shame! (celibate ire raised) . . . Rob Murray's crew won a race? ... probably rigged ... Look, go away and leave me alone! Can't you lishen, you poor sot! Leggo! Leggo, I say, leggo!

4.20 p.m.:... Am going to cox a theological crew now. Of coursh we'll win! WE'VE got help ... Brother Richard B.G.S. is the stroke, the rest a very holy crew. Who says the thogs are a clique?

4.30 p.m.: All over. We won. It didn't look like that from the bank, but we won . . . Oh yeah? Wanna make something of it? . . . They had second VIII rowers in their crew .. . Right, so Brother Richard did row for Dur-

ham, but their crew just couldn't win. It was full of Protestants ... WHO'S bigoted? .. . now hang on, mate .. .

4.35 p.m.: Quoth Mr. McP. as he stepped into the boat, "What? NO Psychologists preshent?" Must remember that . . . The sun must be setting ... I think ... The Bainbridge Jr.-coxed pair returneth. (They didn't know how to stop the boat and had to row past the Riverside Inn!)

4.40 p.m.: Mr. P. F. Johnson coxeth an elegant crew bedazzled with the presence of the neophyte Senior Student ... Oh gallant caravel ... Finlay Cornell is having a swim.

4.45 p.m.: No sign of the other boat for the final race. The Murray-coxed barge hath departed anyway . . . Look, I'll tell you what you can do with that football ... (thinks — more penitential thoughts).

4.50 p.m.: Dicit Lyman L. Jones Jr. (re Elliott Fours), "It's a HELL of a GOOD theeng!!"

4.55 p.m.:Poor Ross Nankivell has had his fezzy hat and boozers' badge pinched. List! Swearing in Arabic . . . threatens to castrate the b— thief ... Oh how Eastern! How biblical! ... A Rumour — Tragedy — Boat sunk in six feet of putrid Yarra water. All lost? J. Schubert coxing — just like the last war! How typical of the Yanks (sudden penitential and SEATO thoughts — mea culpa, mea culpa ...).

5 p.m.: Rumour confirmed . . . Did they really sing "Nearer my God to Thee"? . . . Liar!

5.5 p.m.: Survivors hath returned . . . It's getting dark ... Mr. Schubert, wet from pate to pedes, is displaying remarkable physique.

5.10 p.m.: So dark now that we shall soon break forth into "Lead kindly Light, for I am far from Rome ..." ... Splitting headache. Must bot a lift back to Evensong. Wonder if it will be as good as the one after Elliott Fours last year ... Coming Father! ... Oh —! the final race. You can stay and watch it if you want to .. .

It was later gathered from sources more reliable than my own existential experience that the crew coxed by Mr. Rob Murray — Toby Hooper, Ian Lowry, Al Richards, Tim Sephton — won Elliott Fours.

PETER ELLIOTT.

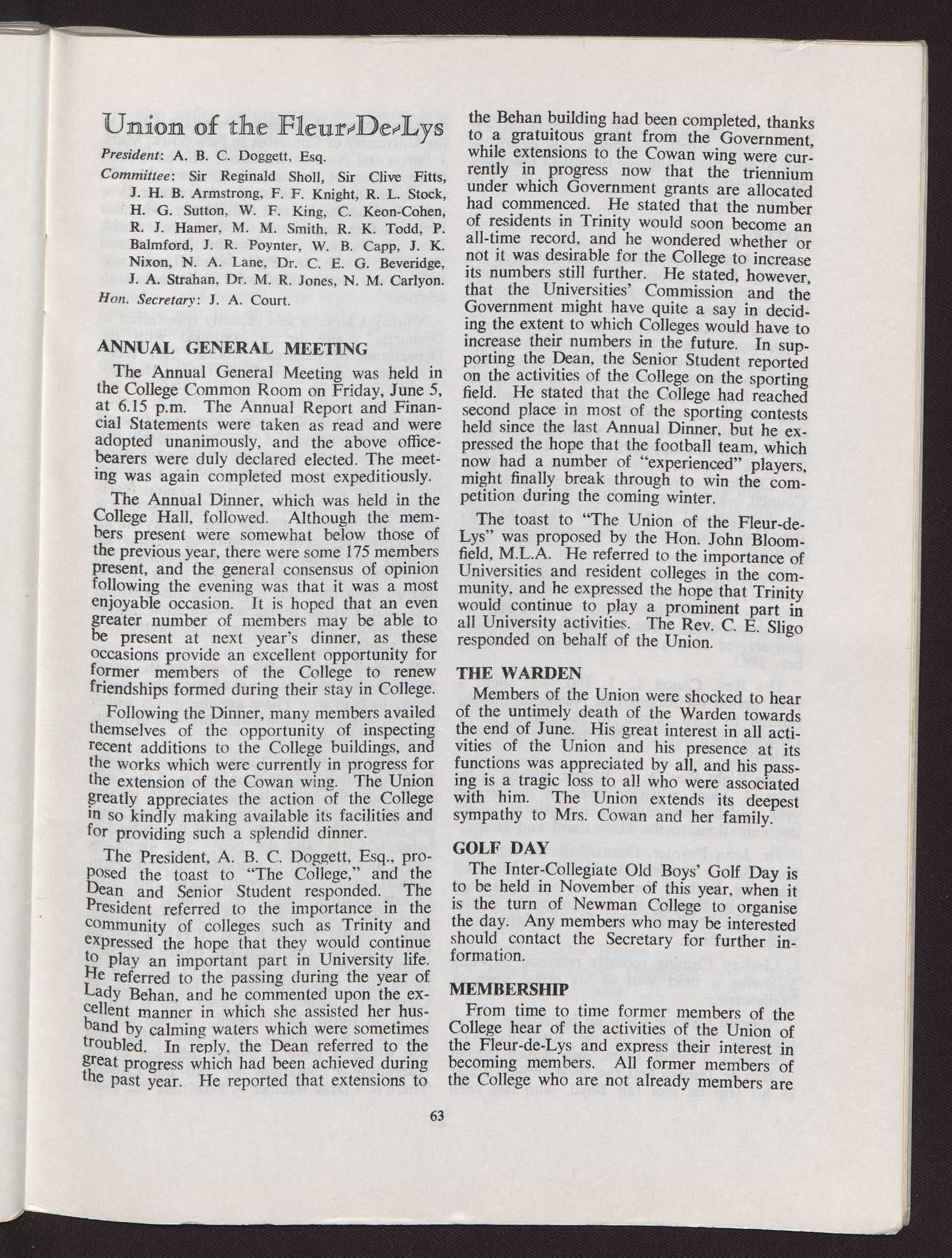

Bottle tops, toothpaste tubes, stamps and nylon stockings have been preserved by ladies this year, for the worthy purposes of the Korean War Widows' fund. The Austrian boy Gunter Rekisson is still being maintained through the Save the Children Fund. And, as well as giving a party for the children of the Victorian Children's Aid Society in Parkville, three J.C.H. students have been giving music lessons to the older children throughout the term.