With one or two exceptions, colleges expect their players of games to be reasonably literate.

MAURICE BOWRA, Warden of Wadham College, Oxford.

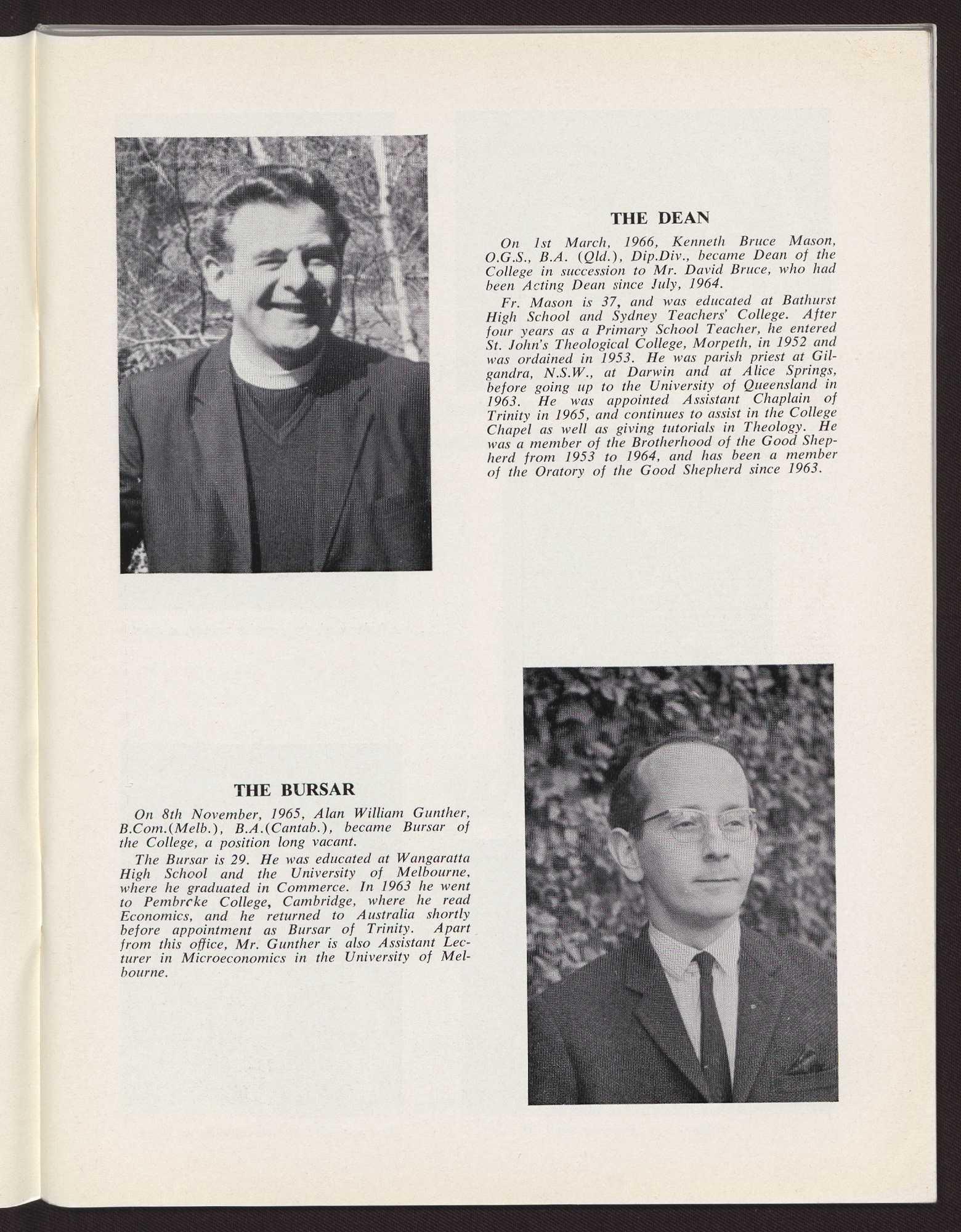

On 8th November, 1965, Alan William Gunther, B.Com.(Melb.), B.A.(Cantab.), became Bursar of the College, a position long vacant.

The Bursar is 29. He was educated at Wangaratta High School and the University of Melbourne, where he graduated in Commerce. In 1963 he went to Pembroke College, Cambridge, where he read Economics, and he returned to Australia shortly before appointment as Bursar of Trinity. Apart from this office, Mr. Gunther is also Assistant Lecturer in Microeconomics in the University of Melbourne.

On 1st March, 1966, Kenneth Bruce Mason, O.G.S., B.A. (Qld.), Dip.Div., became Dean of the College in succession to Mr. David Bruce, who had been Acting Dean since July, 1964.

Fr. Mason is 37, and was educated at Bathurst High School and Sydney Teachers' College. After four years as a Primary School Teacher, he entered St. John's Theological College, Morpeth, in 1952 and was ordained in 1953. He was parish priest at Gilgandra, N.S.W., at Darwin and at Alice Springs, before going up to the University of Queensland in 1963. He was appointed Assistant Chaplain of Trinity in 1965, and continues to assist in the College Chapel as well as giving tutorials in Theology. He was a member of the Brotherhood of the Good Shepherd from 1953 to 1964, and has been a member of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd since 1963.

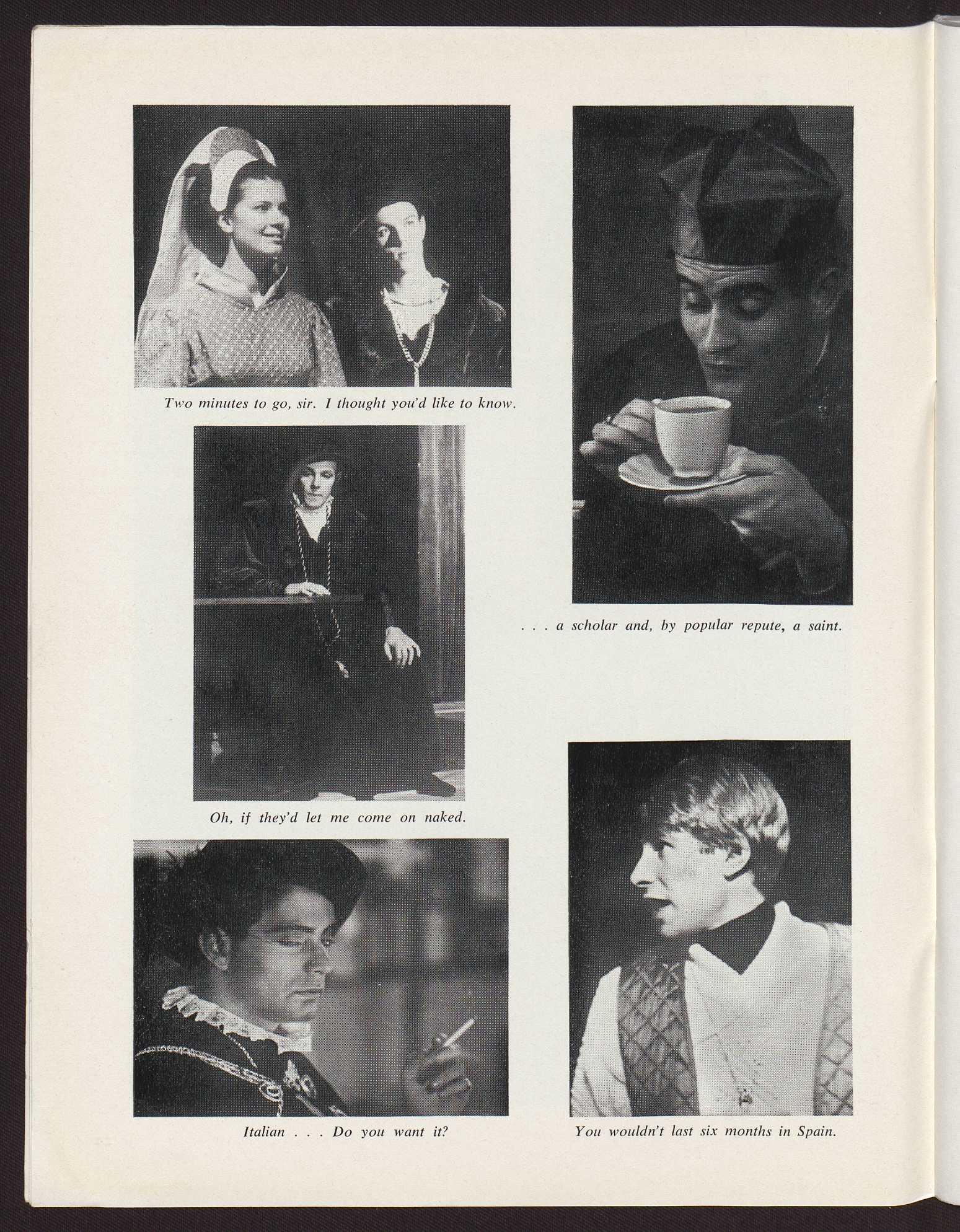

Two minutes to go, sir. I thought you'd like to know.

Oh, if they'd let na;

.. . a scholar and, by popular repute, a saint.

m Italian . . Do you want it? You wouldn't last six months in Spain.

November, 1966

After years of exposure to the editorial axe, the image and role of the College and the College Gent have, perhaps, been chipped and chopped beyond recognition. But the editorial which ventures off the traditional track strikes trouble. Should it be an indication of the philosophy behind the entire magazine, or is the individual editor to indulge in the analysis of a topic cautiously selected as "appropriate"?

It is absurd to pretend that an identifiable "philosophy" runs through a magazine with forty contributors and four editors, covering the field from football to marriages, so that accounts for the first possibility.

If one is denied a touch of editorial philosophy, a little pithy comment and analysis seems inevitable. But to resort to that technique for its own sake! Lest this aspiration be abused, I venture no further.

—P.A.H.S.

After reading Mr. Spear's editorial contribution, one might be forgiven for wondering if he has actually said anything. He has, in fact, rather neatly passed the buck. He has left his "colleagues" to flounder along in a wash of cliches, fulminations and generalisations, not to mention Exhortations and Great Truths, after cunningly pointing out that an editorial is a waste of paper, anyway. He might be right. But while he leans triumphantly on his editorial axe, it might be worth wondering why (and wasting some more paper in the process).

In recent years, editorials have either "probed" or "surveyed", depending on their perspicacity, such burning issues as "What is the College and/or University for?", "What is Fleur de Lys for?", "What are we for?", and, most disturbingly, "What is anybody for?". I don't pretend to say sooth on any of these hoary old problems, for the incontrovertible reason that I don't know the answer to any of them.

The existence of a species known vulgarly as "the College gentleman", a fixation of some previous editors, has always seemed a particularly bizarre conception. Perhaps a soupcon of Old World accuracy intrudes, but an unhealthy number of the supposed "men of chivalrous instincts" in this place seem, to the possibly confused perception of this writer, to be a collection of loud-mouthed buffoons. There are, of course, other definitions of "gentleman", such as "man of wealth and leisure", "man who has no occupation", etc... .

If the reader will pardon the interpolation of a Great Truth at this stage, we do "live in an ever-changing world". Not, however, in an ever-changing college. Trinity is still a pretty steam-driven sort of place, a state of affairs for which I, as a litterateur, have no solution. (So much for analysis.) I merely limit myself to the Exhortation that, if anyone has a new idea about anything, the right course is to suck it and see. (So much for pithy comment.)

Fleur de Lys itself, as the pithy Mr. Spear so rightly points out, has no "identifiable philosophy" — it doesn't even have a concealed

one, Freudians please note. What it is, of course, is a collection of unwilling reports of everything of interest (and some things which aren't) which happened in Trinity and The Hall before the closing date for copy. As editors, we, the undersigned, are responsible for the printed word, but not for the activities necessitating description. Only that mythological beast, "The College", can be that responsible, or irresponsible, as the case may be. So, with the final Exhortation to the reader to don his rose-tinted lorgnette, my message to anyone who has read this far is "read on".

—M.D.

—Alice More.

The best way to indicate College life would probably be to describe in detail some College activity, like a College Dinner or a CRD. But the bounds of both propriety and tradition prevent me from doing this, according to Mr. Spear, who states that "the editorial which ventures off the traditional track strikes trouble". This seems to me to be impossible; for, by editing this magazine, the Editors have shown themselves to be committed to tradition, and any attempt to write a strange editorial for Fleur de Lys must be merely trying to widen its College world-view, and not aiming to destroy it. Tradition seems to lie at the basis of Trinity life, both in the highspots like Juttoddie and as a general graph against which to write one's sporting or spiritual activities. The question whether Trinity has any right to exist in a restless and much-moderner-thanJeopardy Australia is, although interesting, an irrelevant one; for in Trinity its irrefutable tradition is both a scapegoat and a deity — and how can a society exist without both of these?

The problems facing JCH are traditional ones, but not in the sense of "usual" questions, for since the Great Divorce JCH has found itself in the unenviable position of a middleaged woman suddenly estranged from a dominating husband and embarrassingly faced with the sight of younger single women settling

down happily and enthusiastically. JCH's present "tradition" largely derives from its past association with Trinity, but the noticeable decline in the number of Trinity men at the CRD may be an indication that not all the ladies of the Hall desire a continuation of the Entente tres Cordiale. The majority may; and, if so, pro-Trinity freshers and Committees in the next ten years may fill in the gaps around the connections which this magazine indicates. But, whatever happens, it is certain that JCH will never consent to a revival of the old state of adolescent dependence.

I am an Editor of Fleur de Lys on the grounds of my belief in the benefits of cooperation and mutual respect of these two Colleges; but as a student at the Hall I must realise that the day may conceivably come when Janet Clarke Hall stops looking on Trinity as a Big Brother whom we hope is watching us, and evolves an identity of its own which permits only a view of Trinity as a hang-out for blokes who may, or may not, be interesting to know.

—C.W.F.

—King Lear.

HER VOICE WAS EVER SOFT, GENTLE AND LOW, AN EXCELLENT THING IN WOMAN.

Women in colleges travel a singular path. Being partial parasites of the old and mellow establishments that are men's colleges, and yet vigorous members of the university body politic, they claim both chivalrous consideration and equality of assertion. Between the poles of courtly femininity and rude academic health, they oscillate in a state approaching spiritual schizophrenia.

Academic institutions, happily, are less pervaded by the materialism outside. They represent communities in an intellectual proletariat where life is determined by series of usually three-year plans, progressing towards employment. The standards of these microcosms, reflecting those outside, exert similar pressures. The woman here must be truly ambivalent. Training for a competitive career, she cannot bludgeon her opposition without losing part of her femininity; she denies her

capacity to inspire in a man that devotion that makes his work a gallant achievement. To combine these demands a generosity and graciousness, infinitely patient and flexible. One thinks of eighteenth-century salons, where gentle manners blended subtly with penetrating intellects.

Whether women's colleges follow this pattern, or become glass-and-concrete stables for intellectual pedigrees, depends on outside developments. Perhaps men's colleges will evolve beyond proud isolation; certainly the universities cannot retreat to any secluded and scholarly niche.

—J.C.G.

Philippians 1: 3-6 — "I thank my God upon every remembrance of you, always in every prayer of mine for you all, making request with joy, for your fellowship in the Gospel from the first day until now; being confident of this very thing, that he which hath begun a good work in you will perform it until the day of Jesus Christ."

I must be frank with you and tell you that my text has been suggested to me by the word "fellowship". One of the ways in which we are celebrating the eightieth anniversary of the foundation of Janet Clarke Hall has been to appoint four Fellows, and in considering beforehand what should be the subject of my sermon for you today it has been this word "Fellowship" which has been running through my mind.

St. Paul first thanks God "upon every remembrance of you" and I think we may first of all thank God for every remembrance of those who have gone before us and have helped to build up the life of our College.

A sermon is not a place for self-congratulation or chiefly, even, for a catalogue of the great and good men and women who have contributed to our life. Detailed mention of them has been made in prayer. However, let me remind you of some of the turning points in the life of our College:

About the foundation of the College let me quote from Miss Joske's short history:

"Dr. Leeper returned from his trip, anxious that the young women in Melbourne should have the opportunity of sharing community life and enjoying University privileges. He found a house in a terrace in Sydney Road, a little

north of Gatehouse Street, and there in 1866 installed Mr. Thomas Jollie Smith, a tutor in Philosophy and Logic at Trinity, as Principal of `Trinity Hall'. He was hopeful that it would become the Girton College of Melbourne, and that there young ladies would enjoy opportunities to study in subjects suitable for them."

This institution was known as "Trinity College Hostel". Let me continue to quote from Miss Joske:

"It soon became evident that the Hall filled a need, and Dr. Leeper, after much effort, succeeded in interesting public-spirited people in subscribing for a new and suitable building for women students on land provided by the Trinity College Council. A committee of influential women was formed to further this aim, among whom was Lady Clarke and also Lady Davies. These two ladies were chief among those whose generosity made this building possible. The sole condition imposed by Lady Clarke in connection with her gift was that the hostel be open to women of all religious denominations."

So it was that Janet Clarke Hall came into being, though the name was not changed from Trinity College Hostel to Janet Clarke Hall until May, 1920. In the meantime, Mr. Smith gave place to Mr. Collins as Principal of the Hostel, but from 1902, with the principalship of Miss Bateman, the male line of principals ceased, and since then the College has always had a woman as its principal. In 1927 Miss Joske took over the principalship and remained in office until 1952. We are all delighted to think that she is with us this day.

In 1928 the Constitution of Trinity College

was altered so as to make it possible for a member of the Janet Clarke Hall Council to sit on the Trinity College Council, and it was also from this date, I believe, that the Principal of Janet Clarke Hall sat with the Council at its meetings. This was a considerable step in the recognition of the status of Janet Clarke Hall.

In the meantime, considerable building operations had taken place and at last, in 1930, with the opening of the Elsie Margaret Traill Wing, all the Janet Clarke Hall resident students were housed under one roof.

Thirty-one years later — in 1961 — after a complicated legal operation, and a great deal of discussion both for and against Janet Clarke Hall became an independent College, affiliated to the University of Melbourne, on ground made over to it by Trinity College. I am glad to say that this separation has not meant a separation of spirit. There is still, and will we hope continue to be, a very great deal of co-operation between the two Colleges, the sharing of tutorials and such like, and not least the sharing of this Chapel.

That, in brief outline, is our history — and we thank God for His providence over us.

Now may I go back to my theme of fellowship. The word is not only a great academic word, it is also a great Christian word and translates the Greek "koinonia", which is the word in my text. But it is not so much of its Christian application as of its broad general sense that I wish first to speak. I don't think it is any secret that the thing which chiefly attracted the present Warden of Trinity from the lofty heights of Canberra to the more lowly uplands of Melbourne academic life was the fact of community life of a College. Human beings are made for fellowship and made by fellowship. And I suppose that it would be true to say of most of us, as we look back on our time in College, that it has been this association-°in a common objective and a common life, which we call "fellowship", which meant as much, perhaps even more to us, than all the strictly academic curriculum. Or perhaps I should say that learning in community is a very different thing from learning in isolation. It is interesting that the new La Trobe University intends that every one of its number — whether they live in hostels or whether they

live outside in their homes — shall belong to a College. In the large agglomeration of students which a modern University is, the sense of belonging is hard to come by. He becomes an isolated student and so misses the full and formative life that only a college can give.

Let us thank God, then, that JCH has provided fellowship, ordinary human fellowship, a necessity for the "good life". But let us thank God also for all that is suggested to us by academic fellowship. If I may make a personal confession, it is that I think I would rather be given the honour of a Fellowship at my College than I think any other honour at all. The original meaning of the word "fellowship" which, I understand, from the Oxford Dictionary, comes from the Norse language, is a person who had put down a fee; he was a fee-law, someone who had, by payment of a fee, purchased a stake in a community. What a wonderful thing it is to have a stake in the academic community, a community which is world-wide, bound together by one thing, namely, the pursuit of truth. At one point, when St. Paul was compelled to boast about his antecedents, he claimed, not in so many words, to have a fellowship, but, as having sat at the feet of Gamaliel, to have a stake in the Jewish intellectual fellowship.

It is right that we should celebrate this fellowship in this Chapel, since all truth comes from God and the pursuit of truth always leads to God, and those who are members of its academic community, particularly those who are members of it, are dedicated in company and in fellowship to pursue the truth wherever it may be found.

This has always been a fellowship of persons far wider than that of their own College, though their own College has been as it were the focusing point of this community of learning. In the Middle Ages there was a tremendous sense of fellowship between scholars of every country of Europe, and I am glad to think that this community sense of world-wide intellectual pursuit is even stronger today than ever before. There is more movement of scholars today from one University to another, and more pooling of resources than there has ever been before. It is not unsuitable that, as we thank God for Janet Clarke Hall, so should we thank God for this stake in a wonderful world-wide fellowship.

But, let us widen the circle. St. Paul thanks God for the fellowship in the Gospel that he has with those to whom he writes. This is the Fellowship of the Holy Spirit of which we speak in the Grace: "the Grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the Fellowship of the Holy Spirit".

Janet Clarke Hall is a Church College and its fellowship is, as it were, a microcosm of that great university fellowship, which is both the creation of the Holy Spirit and which is cemented by the Holy Spirit. This Church is a community of persons who know themselves to have been made members of this great family by the action of the Holy Spirit and who, at the same time, know that all the resources of intellect and emotion of brain and being, indeed of life itself, are the gifts of this same Holy Spirit and are gifts given in the fellowship of the Holy Catholic Church. This is not to say that the action of the Holy Spirit is bound by the boundaries of the visible Church: "extra ecclesiam mula salus." This is sometimes translated — outside the Church is there no salvation? I prefer the translation which says that without the Church there is no salvation. Wherever there is truth, beauty or goodness, there is the Holy Spirit at work, but these gifts of the Spirit would not come to fruition were it not for the fact of the Spirit's community, the universal Church of Christ. Don't let us despise our link as a college with this Church. From the start we have been inter-denominational, but we have never been secular.

V.

But I ask you to lift your sights even higher. I must add to my text these words from the first epistle of St. John, the third verse of the first chapter:

"Our fellowship is with the Father and with His Son, Jesus Christ."

This is, indeed, a staggering thought. We can understand very easily that human beings are made for fellowship one with another, and that apart from such fellowship human achievement would be impossible. This human fellowship is also divine. In Christ God has fellowship with man. In Christ man is given fellowship with God Himself The central act of worship of the Christian Church is an act of fellowship with one another which is contingent upon our fellowship with the Father and His Son. If you accept the Biblical revelation, and if you believe that man is created in the image of God and has had breathed into Him the breath, or the Spirit, of life, the consequence follows naturally: man is made for communion with God, and it is that fellowship with God which makes him truly human.

I will not enlarge upon this. I only want us to be sure that we put first things first and remember that all our learning and all our fellowship will be poor and thin if it is not founded in fellowship with God, and in the knowledge of God.

So let me finish with the last words of my text: St. Paul writes thankfully of his friends at Philippi because he is confident that he— that is to say, God — who has begun a good

work in them, will continue it until the day of Jesus Christ. We look forward to many, many years of service by this College to its members and by the members to their College and to the University and to the world at large. The first eighty years of a College are but a beginning, and God Who has begun a good work here will surely continue it. We live in a world of change, indeed, of revolution.

Some people think that committees are just some fabulous animal, shapeless, effortless and brainless, which enjoys being the centre of attention and speculation.

Others tend to look on committees as a purposeful and well-intentioned experiment in collective action.

Actually, we do not look upon ourselves — as committee members — in quite this exciting and definitive way. Perhaps if the reader would care to think of a board of directors, corporative, pressured, permanent, then he will not be too far from the half truth.

Burdened by the shame and unfinished business of its predecessor, the new committee is relatively uncommitted to any policy at the start of its year in office. It is only during the course of the year that it assumes any identification with the issues that concern the College. Committee work should ideally involve detaching controversy from day to day complaints, changing muddle into order, apathy and disenchantment into sensible recommendation, and establishing general principles— for in an institution so loosely principled and so randomly organised as a university college, there is a very great need for general principles. Establishing general principles really means planning, and at Trinity planning means organising a mass of undifferentiated opinions, values and humbug into some viable and intellectually honest argument or policy. It has to be this way because to achieve reform students need bargaining power, and the technique of persuasion does not come from flabby conceit or emotion, but from persistence and recommendation.

Of course, change can be pretty abrupt— witness if you will the amazing fee rise. It

We must expect that Janet Clarke Hall will change in some respects and we must have the faith to believe that He Who has begun a good work will continue it in change and through change — but that fundamentally the work will remain the same, namely in fellowship to pursue truth as fellow-workers with God.

appears, to anyone as ill-informed as the writer, that this year's College budget was a crisis affair, enacted to deal with our lopsided economy. Trinity's economic position is simple and common

After a few years of boom inflation and excessive investment, annual income began to slump behind annual expenditure. A typical balance of payments predicament. The textbook answer is stop, deflate, wield the fiscal cosh at the luxury sectors, raise taxes-fees, and force everyone to struggle into their economic corset.

This was the second deflationary round in eighteen months because of Trinity's precarious payments situation. In view of this, I suggest that the College needs a prices and incomes policy, a sort of national plan which lays down recommendations, firstly to improve the whole ghastly mess, secondly to name investment priorities, thirdly to indicate methods of improving efficiency and productivity, and fourthly to excite a sort of managerial cum academic spirit of Dunkirk which will give the College the impression that some businesslike reconstruction (post-war?) is going on. Any impression so long as it gets us away from government by spasm.

Compared with the economic policy of the College, the remaining issues look like tarnished coins indeed.

The Committee were glad to see the old chestnut of Women hours crop up again. Glad because it is a testing ground for any administration, and yet disappointed because no one is entirely happy that either the students or the authorities perceive of women hours in the most practical way. Extended women hours is not a matter which is best decided upon by voting, it is more a matter of coming to realise that Trinity is a male College in which each gentleman may study, amuse and discipline himself in a manner most enlightening to himself, so long as his behaviour does not interfere with the privacy of his colleagues.

This year the College did not ask for orthodox Scandinavian sexual freedom, or its Antipodean equivalent, rather it asked to have women in College a little longer and a little later than is permitted at present. However, the students must have touched some of those ticklish and erogenous policy zones for the answer was definitely no; the whole charade has been confined to mothballs for a year and a day.

Still, with chaste optimism, I do believe in the words of that old love song, "our day will come". I should add that the next line goes on to say "and we'll find everything". I would not like to speculate on it, and certainly more women hours do not guarantee it.

What else happened in Trinity this year? (You must be joking.) It is always gratifying when College rules take a change for the better, and every now and again we are able to appreciate this.

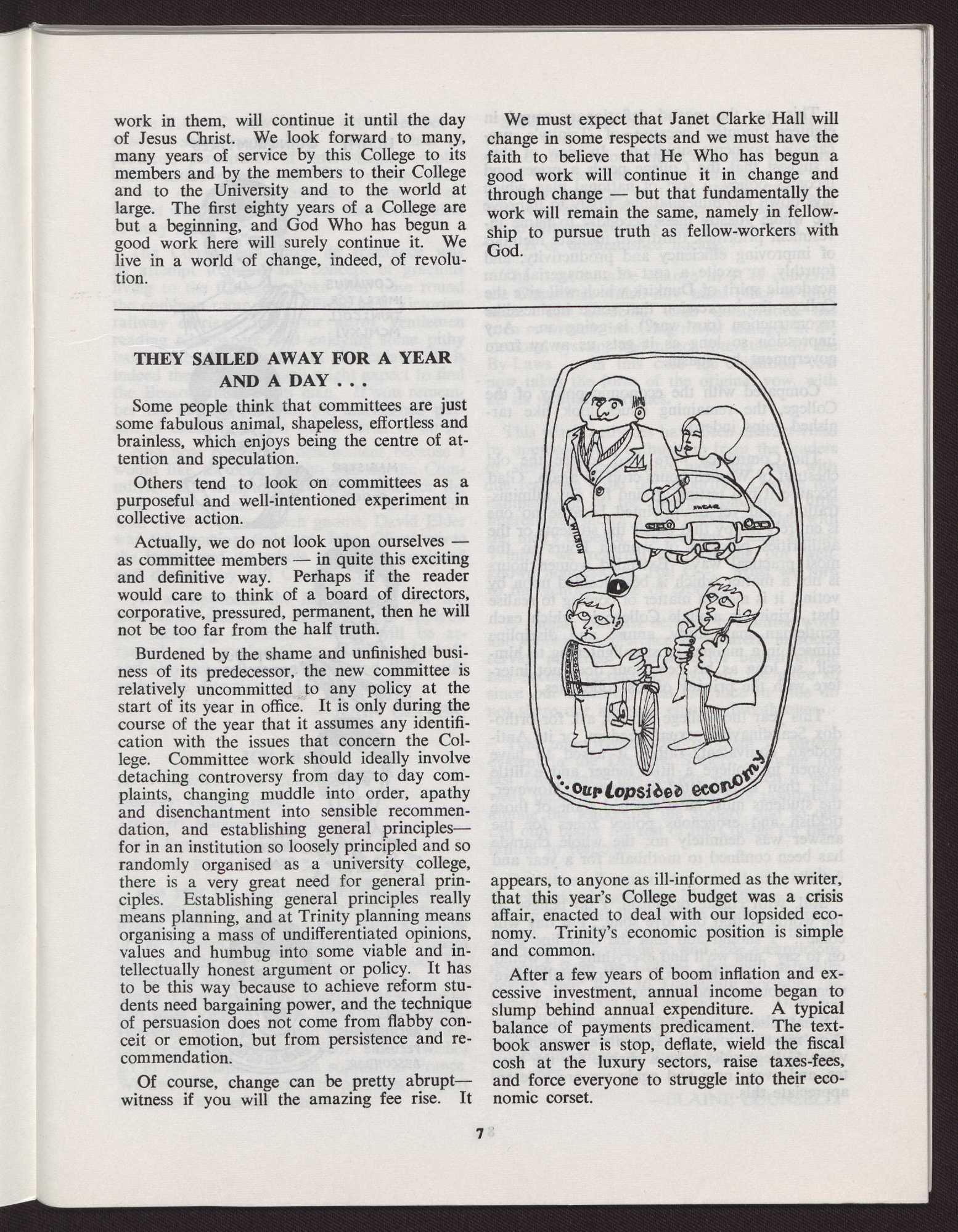

CO WA NUS IMPERATOR. TRIM I COLL MCMLXVI

The T.C.A.C. now has an extra member— a social secretary no less. He is a chief of protocol, perpetrator of intercollegiate diplomatic initiative, ball and C.R.D. entrepreneur, a sort of campus (kampus?) James Bond blessed with uncommon talent and savoir faire. A busy man.

The Committee's piece de resistance was its attempt to bring the concept of gracious living to the College. Poke your nose round the common room door. Plush as a Victorian railway carriage, incubator warm, gentlemen reading newspapers, and enjoying some pithy banter (about something in particular). It is indeed the very place you might expect to find the Benson and Hedges man. If you remember the old adage about the unashamed pursuit of excellence, then where better to do it?

And now comes the denouement because I would like to mention who was on the Committee: Bill Kimpton was responsible for the stage management of the show, Alan Archibald acted as our Zurich gnome, David Elder was the sporting diplomat, John Oliver wrote the lyrics, and the whole thing was produced and directed by Bill Cowan.

As we approach the last night of our uninterrupted season we should like to applaud the incoming Committee which will be arranged and conducted by Adrian Mitchell, and also say well done to the mod JCH outfit under the direction of Libby Eaton.

—JOHN OLIVER.

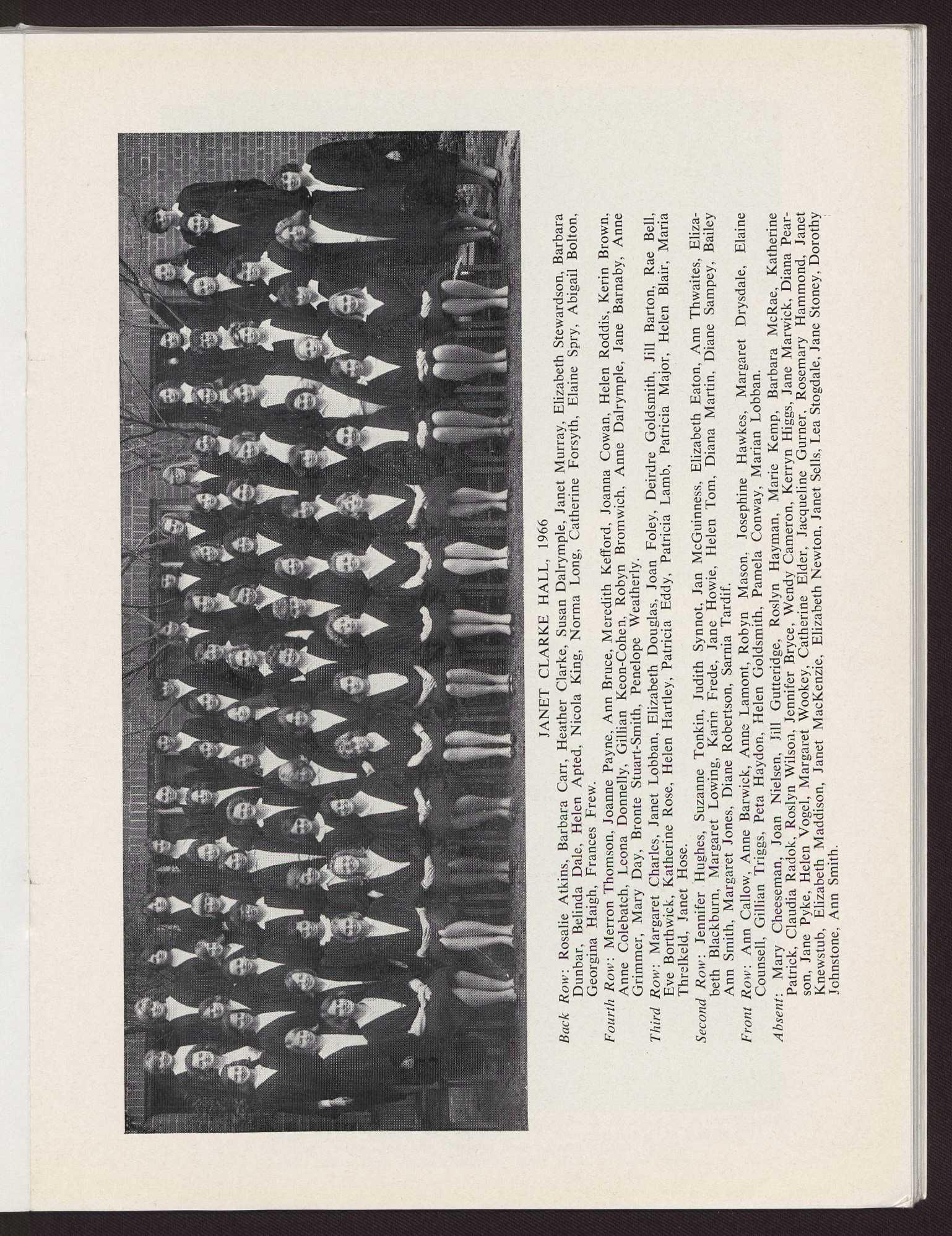

Senior Student: Elaine Counsell.

Secretary: Gillian Triggs.

Treasurer: Margaret Drysdale.

Home Secretary: Josephine Hawkes.

Librarian: Peta Haydon.

This year the eightieth anniversary celebrations brought distinction to the Senior Common Room when Miss Aitken was made a Fellow of the College. We congratulate Miss Aitken and the others Fellows, Dr. Blackwood, Dr. Henderson and Dr. Knight. Other news of the Senior Common Room concerns Miss Huang and Miss Viggers, whose departure we regret. However, we look forward to continued musicales with Miss Booth in 1967. Good wishes go to the Chaplain for his sojourn in France. We await his return when he promises to sport the latest in clerical fashions.

Social activities have brought many visitors to the College. Of special interest was the visit of the Oxford and Cambridge debaters, Keith Ovenden and Jeremy Burford. For this particular privilege we thank Gillian Triggs, as Miss University. From Jeremy we learnt that the traditional style of the Trinity-J.C.H. debate is of distinguished lineage.

The most notable change in JCH concerns the Committee which now takes office in third term. The Students' Club Constitution has been re-written, involving major changes in the electoral system, and minor alterations in the By-Laws — in this case the initiation vow now takes the form of the original vow, with all its nuptial overtones.

This year's activities have been characterized by unprecedented enthusiasm from the leaders of sub-committees, who have not met with due response from the majority. Despite the campaigning of the Sports Committee, little interest was shown in the hockey matches with the men's colleges. In seeking a team against Trinity, we resorted to including our wellknown non-resident, Hal C—. Must we turn to the gentler game of croquet?

A similar contrast between committee work and College indifference is apparent in social service projects. The need for united giving has become increasingly evident, the more so since our discovery that the men in blue do not share our ideas on charity discotheques.

This minority/majority problem is further evident in the Dialectic Society. During the last four years, this Society has been a very weak phoenix. There is no lack of inspiration among the leaders of the Society, and so one can only blame the rest of the College for their failure to respond.

Doubtless all senior students silently lament the chronic phenomenon of "indifference", but I think this year the problem needs to be mentioned. If, after unprecedented work, the active minority continue to find only a capricious response from the College, they will naturally devote their time to University Societies, as some of our best students do now. Thus, we will fail to meet the stronger challenge of other colleges, and University and College interests will become more conflicting and less reciprocal than ever.

—ELAINE COUNSELL.

I . have not always felt that the Dialectic Society was a hopeless cause. Indeed, when I first . read the . rules and aims of the society, I was impressed by its apparent importance in College life. Even after a year I had not lost faith. There were "giants" who still made me feel that the society carried some weight in College. But this year the response to efforts of people like Fenton, Telfer and Peter Elliott has been more disappointing than ever.

I don't think that a society where you have to drag members along serves any useful purpose. The desire to join in discussion on current affairs or philosophical ideas is just not the sort of thing that can be fed into you, or sung at you like a television commercial.

This leads . to certain inescapable conclusions: Firstly, that very few people regard public speaking as important or . interesting in their lives. Apart from the Dialectic Society, this is evident in TCAC meetings, where attendance is also down, and in the attitude to speeches at College dinners. Speaking for speaking's sake seems unwanted (or at least unappreciated). The result is that no one seems. much interested in attending a debate,

whether serious or frivolous. Secondly, there is obviously an unhealthy imbalance in College between communal intellectual pursuits and communal social and sporting activities, with thought coming a very poor second to action. The majority of people in College, whether scientists, historians or anyone else, have little time or inclination for serious thought about anything outside their own particular field. The Dialectic Society could be the ideal instrument for helping people overcome their lack of intellectual contact with what are basically other specialists. This leads to my third thesis which concerns guest speakers, forums and similar ideas. The response to the symposium on Vietnam was unique in its enthusiasm, and it is worth noting that the Dialectic Society had nothing to do with its organization. The high standard of the speakers that night is just the sort of thing we're striving for. The interest in guest speakers was also more than satisfactory. As a result, one is inclined to feel that this is what the Society should aim to dish up to the College. One can imagine a guest speaker once a fortnight or so, with forums on various topics, say by the Engineers on car design, or by Medical students on cancer. If this was mixed with a

flourishing series of Sunday salons, I would find myself thinking that the College was worthwhile intellectually as well as socially. The trouble is twofold: trying to get the bulk of people in College to write essays is like trying to get them to take up ballet, while, on top of that, one has to attract an audience at each of these occasions — and once again, one suspects, people in College will go their own merry ways.

My three conclusions, then, are: (1) Interest in debates as such is nil; (2) Lack of interest probably reflects the specialization inherent in academic courses; (3) There is a viable alternative to what now passes for a Dialectic Society, but it would probably involve the end of debating as such in this College.

—PETER SEDDON.

Early in the year, murmurings were heard around the College that terrible things were happening in Lower Jeopardy. And, in the twinkling of an eye, McCarthyites raged and longed for Juttoddie, the College religious checked up on the floor Chapel attendance and breathed anathemas, and Monarchists

imagined they bespied fledgling Geoffrey buttons in the sun-starved corridors as the news of the L.B.J. Society went forth. And it was spread abroad by some that the local U.S. Information Centre, rejoicing in the discovery of an antipodean outpost of the "Great Society", sent to Jeopardy thirty endorsed copies of "The God That Failed" with tears and a thankful heart.

We must, however, disappoint Ambassador Clark and his lackeys. It was the positioning of an over-used expletive in the middle of the floor name rather than adoration for the thirty-sixth President which gave the society its name. But its activity has not been entirely frivolous. In the main it has been to engage in seminars given by members of the floor, with the occasional outside guest, on topics which are not confined to any particular discipline and have some relevance to important social and intellectual issues. But in a sense the topic, so-called, has been less important than the mere fact of bringing together in equal discussion men of many varied academic interests. It was hoped that, in some way, the quality of College life, at least for the people concerned, would be improved. —IAN LANGMAN.

Even at eight the sky is softly night; Its edges, never ragged, have the fine Fragile divisions of a Chinese drawing— Delicate perfect trees along the west.

The quiet sky rattles with the wind Shaking the stiff palm-leaves; The local children, swimming, scatter the sky With distant seagull cries.

I have sipped cold water in this night Comfortably; and still I cannot remove Your face from the sky, or distinguish Your voice from the air.

But even though some perfection snapped With the fine doomed fragility of our love, This sky, darkening, mellows: Changes, but never breaks.

—KERRYN

HIGGS.

Wigram Allen Prize Essay 1966

I have always been fascinated by the variety of sporting and recreational activities undertaken by the members of our community . . . and fascinated also by the apparently numerous motives and social forces behind them. There are a large number of men, for instance, who subscribe to a mystic relationship between physical exercise and mental health, which puzzles me. Never content as spectators, they play football, hockey and similar games when young, and form weekend tennis parties with alcohol and bad language when older. These activities provide a weekly fuel of fitness with which to temper the discipline of weekday mental and physical activity. Many others, of course, take up spectator sports at an early age — there seems to be little distinction between manual and mental labour when choice of recreation is made.

If we glance back into history, we find that the primitive man naturally combined physical and mental activity in earning his living, which was hunting. Survival of the fittest at its most stark. The social unit in the cave was small, and the enterprises of the prehistoric man were presumably translucent with stoic simplicity and virtue.

As the social unit has grown from roving tribes and villages to cities, the individual man in particular has ceased to perform tasks identical with the man in the next cave. He has become more or less a specialist, performing tasks which, when united with those of his neighbour, support the whole society — not just the family unit. After hours, of course, the man's duties are more primitive.

The sophistication of roles has Ied to an unnatural type of weekday activity which requires balancing recreation — in some cases to restore the body and in some cases to restore the mind.

The physical fighting encounters, available so unashamedly to primitive man and an excellent reflection of original sin, were concentrated into a Saturday or equivalent afternoon. These had to be enjoyed vicariously by a new phenomenon — the spectator. The idea seems to have been to set in conflict reasonable equals for extended physical engagement . . . the more equally matched the greater the ten-

sion and excitement. Thus there were gladiators in Rome, jousting Saxon knights and virtuoso football teams at the Melbourne Cricket Ground.

The primitive man was driven by the necessity of survival to engage in physical combat, man with man, and man with beast, but not so the modern spectator, whose participation is only vicarious, unless the primitive beast comes out in him. The necessity for recreation is not as compelling as the primitive man's necessity for recreation. It is therefore well to instil added virtue into these modern pastimes by gentlemanly rules, fraternity, prizes and fervent adulation of championship.

Is it surprising, then, that the more gentlemanly schools rabidly extol the virtues of team sports and athletic attainment? . . providing excellent group brainwashing and commendable preparation of spectator material. Rare is the Senior Prefect who cannot play the game, and shunned the mere bookworm.

The efforts of these institutions have been undeniably successful, and not only is there a general aura of masculinity in participation, but also an actual belief that suspension from a team or sporting activity is a devastating punishment. On such the Western District mentality is fashioned.

In the post-school stage, of course, such brainwashing receives professional exploitation. The sporting tribunals become the little man's haven for regulating the war-like tendencies of the performers in arena sports — a means also of maintaining interest throughout the week for spectators.

One tragedy is that the lady-like schools have adopted too many gentlemanly sports like swimming, basket ball and hockey, extinguishing the primitive, docile females so characteristic of most extant primitive tribes and encouraging emancipated womanhood as criminological statistics, American Housewives, and suffragette clergywomen constantly remind us.

At this point it is well to remark that many take their leisure in the individual primitive manner. These are generally the more sensitive members of the community who are cap. able of dredging their souls by imagination in-

stead of corporate physical catharsis. They read, they listen to classical music, they paint and even think. Not that they don't indulge themselves from time to time in corporate recreations, but having learnt so well vicarious enjoyment, the experience is apt to be traumatic.

No — it is they who will be found on a Saturday night at the symphony concert, the ballet, the theatre, while the bulk of the populace is at home re-living the afternoon on the telly. Exhausted from standing in the outer or drinking in the members' ,they will test their memories and see things from another angle in the replay, guessing who marked the ball when the buzzer goes. These programmes are repeated on Sunday for those whose closer participation in arena team sporting clubs requires them to perform socially after the clash until the early hours of Sunday morning. Not surprisingly it is to these functions that the more beautiful and less suffragette women flock. They bind the wounds of their heroes and catalyse the primitive individual prowess of such performers.

Meanwhile, the people hearing Isolde's Liebestod in the Town Hall or watching Salome at the opera house are no less content. Their vicarious capacity is such that their enjoyment can be even greater than the indulged footballer. And to provide the stimulating sight and sound, moreover, the orchestral players, the singers and dancers have to be even fitter than footballers. The music critic of The Bulletin had a point when he commented in the 3rd September issue: "Zubin Mehta was a godsend for those who view conducting as the most sophisticated of spectator sports."

It would seem that our choice for sports to admire is a matter of taste, not good or bad taste, but different taste. The canvassed antagonism between artistic sports (if I may call them such) and athletic sports seems as much a waste of time as that canvassed between religion and science. All will survive with official blessings. The critics of Helpmann as Australian of the Year and Governor Cutler as Father of the Year might pause to refresh themselves with a question: who is fittest to survive?

The answer seems to me to be those who develop their sensitivity or vicarious pleasure early in life; a sensitivity which increases with knowledge and years, unlike an athletic talent which hastens early from the body and leaves

one on the bowling green. While physical fitness can certainly stimulate the intellect, physical fitness alone will not stimulate the aesthetic sensitivity of the individual, it is tragic indeed to see so many people in our community burnt out at an early age, with formidable intellect certainly but little imagination and sensitivity. They live an old age of boredom in a working, television and gardening rut, waiting for life to be snuffed out. Newspapers and grandchildren are their main novelties . . . grandchildren to whom they have little to give but fantasy tales of stoic youth and athletic achievements.

And the dangers are becoming worse as our society develops its odious characteristics, moulding a more desperate recreational mentality, highlighting specialisation in weekday activity, deviating further and further from the prehistoric norm. There is less and less room for the golfer and hunter and fisherman to escape, for as weekday working hours are reduced more will find time to crowd the retreats.

In truth recreation will become a real art, and I am not sure that the sensitive bookworm, the artist and the music lover, who perhaps even at school enjoyed their sport vicariously, will not be fittest to survive.

—DAVID

FENTON.

Australians are very strange people. One of our strangest aspects of character is a selfconscious sense of inferiority about places we know too well. Everything "abroad" is bigger and better until one manages to get "abroad" when, suitably oiled with the local nectar, our Australian informs everyone within shouting distance of the gold-paved streets of Brisbane, the solid silver coathanger across the Harbour, that Ayer's Rock is several miles high, that the bloke who caused the tragedy of the pub-with-no-beer is recounting these facts, and, of course, that sometimes the sun shines in Melbourne.

Melbourne . . . It seems strange to praise the city of one's birth and upbringing in the company of friends who share an almost filial regard for her, almost as obvious and embarrassing as telling friends how beautiful someone is when they know her well and she happens to be in the room at the same time. But that is the problem when one comes to reflect upon the city. It is part of us all and we are part of it, so much that we hesitate in applying neuter gender when we speak of "her". The modern mind is now consciously and unashamedly urban. The pessimists point towards the sociological nightmare of the megapolis which will emerge as the metropolis explodes. But I am an optimist preferring to leave such horrors to the Science Fiction author or those theorists who earn a living by writing deep works on hypothetical problems. I wish to praise Melbourne, my Melbourne, for in arrogating personal possession to the immense sphere of existence I find the basis for my praises, the impressions of childhood.

Returning to the city of birth at the age of five after four years in the country was quite a surprise, for I remembered nothing of that city at all, which is not surprising. First impressions are thus little more than vivid sensations experienced in an inner Northern industrial suburb, noises, smells, sights and spectacles. I remember the mornings pierced by the distant factory sirens and heavy with the odour of the manufacture of Weeties, the winter afternoons when the peace of the nearby park was disturbed by the roar of crowds at the football ground, or the blood-curdling cries of little boys in short grey pants with braces, re-enacting the Korean War and the same little boys sitting up in church on the following morning with brilliantine-soaked hair, the

addition of a double-breasted grey suit coat to the same grey short pants and wide bright tie puffed out in proud parody of adult fashion. Visits to the first Italian delicatessen in Carlton come to mind, to the Aquarium which burnt down, and the Exhibition Building next to it which everyone said was going to burn down. Standing on a large hill in the middle of the park, later removed by the Council because it provided visual interest, a child could see a vision of the city which has changed little and retains a symmetry and beauty of its own, the view of the Eastern Hill capped with the hospitals, the fire station and the slender grey spires of St. Patrick's. Those spires ... taken singly no more ridiculous example of malproportion could be found, but together they are daring and elegant. Those spires ... in the days of sectarianism one child found himself involved in noisy disputes as to which cathedral had the tallest steeple, disputes which were usually solved in the most direct fashion. But, to me, this vision was the essence of the whole sprawling mass of buildings and people, the central hill echoed by the sentinel slopes of distant Northcote, Kew, St. Kilda and Footscray, a geography in which the human city is not an intruder but in a sense a necessary completion of the creation, almost a living organism.

It is mawkish to say that the people are the city, an indication perhaps of a tendency in modern urban life to separate the inanimate skeleton of buildings and streets from the animate occupying flesh. We do not wish to identify ourselves too closely with the city because it may tie us to the past, for other generations have left a more vital and splendid impression than ourselves. Growing older in this city can provoke an inquisitive desire to probe the past.

If you would see the living faces of Melbourne past I would take you down the narrow streets of Fitzroy or up the steep Richmond Hill or through the lanes of Abbotsford, past the single-fronted dwellings, where in the dusk the old women with leather faces, hardened and lean, dressed in long cotton-print aprons, casually greet their several generations of passing neighbours, or shuffle down to the dark little corner shop with its sickly odour of eighty years of cheap confectionery. But they are vanishing, withdrawing into shadowy curtained rooms heavy with the fumes of patent medicines, slipping away to a well-tended grave. The next generation to the ancient ones can

be seen on the trams which pass near the cemeteries each Sunday, plump bundles of scented well-washed wool, clutching flowers for the departed, sucking peppermints and with the inevitable sprig of daphne pinned beneath an old gold brooch, living token of the visit to a friend's garden.

Talk to them and even these old ones, but children at the dawn of our century, will recount the past of the corporate city. They share that strange Melbourne pride which lauds our city by contrasting it with another. They will tell us, half joking, "God gave them the Harbour, the Scotsmen built the Bridge, and what did they do for themselves?" The pride of her people passes on, but there is a placid Melbourne character which tempers it, so far sparing us from the hurried hardness of the other city. I do not criticize. I merely observe.

With the memories of some old South Yarra dowager or an elderly workman in a pub we can look upon the sweeping avenues and vistas of the city with eyes no longer bound by time. Step into the city arcades, the old arcades, and the past drifts across the mind. We detect the chatter and clatter of the coffee palaces and the music halls, the clamour of the street vendors, the murmur of the crowded bars reeking of bay rum, bear grease, sweat and beer, and cheap tobacco, the bubbling piping of a street organ and behind it all the incessant rumbling and clopping of a thousand passing carts, hansoms, carriages and drays. I love the arcades, they are the old public life of everyday Melbourne, whether we seek its memories in the steady bustle of the Royal Arcade, where Gog and Magog strike out the hours bewitching a century of little children, or whether we wander in the cool splendour of the great Block Arcade, where within living memory the sophisticated and fashionable paraded, "doing the Block" as they put it . . . and why? "Oh, simply to see— and be seen."

The sedate Melbourne past is still with us, but changed. The rigid social caste which divided the aproned women of Abbotsford from the dowager in South Yarra is not as inflexible as before. Other families occupy the stately homes of the past figures of gentle society, if the homes have survived at all. The pale-faced people imprisoned, it would seem, in black broadcloth and black silk, would be raised to their carriages to journey from the

city to their mansions in the south-east. The same carriage would carry them, all white and glorious, to the great Ball which celebrated the opening of the Exhibition Building, where thousands danced and feasted beneath the dome. On a sunny holiday they could be seen setting out in the ferry as a brass band played for the picnic trip to that watering place rearing its towers and Norfolk pines above the Bay, to Queenscliff. But the riches of the 'eighties have long passed away and all that remains of that age is the faint whisper of taffeta and the muffled footsteps which, I am assured, may still be detected on a drowsy afternoon on the staircase and in the passages of a certain old mansion in Toorak.

Since then we have seen two depressions and several wars and the more recent memories of Melbourne are easily at hand, violent memories, petty memories. The troubled expansion of this living organism, with its many facets. Who could picture Bourke Street when the Police Strike was on and a howling mob of several thousand swept down from Spencer Street smashing shop windows and looting as they came, only to be stopped by the reading of the Riot Act and the batons of volunteer police? People still remember the cable trams, the days when the streets were very dusty, the years when the eccentric Killarney Kate sang Irish ballads in Bourke Street or when Cole's Book Arcade sold a million books for the masses. Melbourne gasped when its extroverted proprietor put large and detailed advertisements in the major papers for a frugal, clean and capable wife. The petty details are still passed on from old to young, the unbelievable prices and sizes of chocolates and sweets, the awesome fact that cake manufacturers really used genuine butter and eggs in their cakes. Forgotten are the working conditions, the past wages and the cost of living, but never mind, such legends soothe the aged and provoke doubts in the bland modern facade of the young.

Growing older in Melbourne and possessed of a consciousness of Melbourne past leads to reflection upon the power of the city grounded in her wealth and tradition. A wandering in the far reaches of the business-end of Collins Street is enough for the tourist who leaves the city very surprised at the brash display of granite and marble and bronze. But power made our city the federal capital for two decades and all know that the national

finance. still centres upon her. . The power of Melbourne is sealed for eternal memory in her buildings, her palaces, for so they seem to me. What other Australian city houses the Governor in a Florentine palazzo, the Treasurer in a Renaissance Roman palazzo, the Government Statist in a French chateau, and the original Post Office in an excellent replica of a large Hotel de Ville? Perhaps her people are not conscious of the splendour of these expressions of power, yet these are the elements which make the power of a great city exciting and living, something, with which the citizen can identify himself.

Today, with several notable exceptions, the people of the city do not wish to share their wealth and power in great monuments since that was all neatly fulfilled by our forebears. We seem to be caretakers and cleaners of the greatness of the past, registering our power in huge commercial office blocks and occasionally beautiful freeways. We do not hesitate to use the marble and stone on these works which our forebears lavished on the cathedrals and the Library. In the cathedrals the mosaics are reflected on the barbaric daring of Butterfield's'; ` chancel columns or in the chiselled alabàster altars set with semi-precious stones which Cluster around a great apse. Perhaps we pause on the grand staircase of the Library to admire the marble, but perhaps only to attempt `a 'rough estimate of the cost in presentday sums The cost is everything now and the profit, the goal of real power squandered on the vulgar homes of the richer outer suburbs.

The sprawl of the city as a greater whole does not betoken real power. It is undignified, uncontrolled and immature. Indeed, most of the expansion of the great metropolis over the past forty years has produced the ugliness, social insecurity and lack of concern between

people which is the problem of the critics, the social workers and those who love the past as much as they hope in the future.

The city surrounds me, I am part of it, my life is tied completely to its wider life. We claim this in an age when urban life is being twisted into alienation. Alienation from persons is indeed terrible, but perhaps alienation from the city as a living whole is part of this. People may find much of the security of the past if they really learned to love an eminently lovable city. What excitement we should feel at the sight of Melbourne seen from afar, let us say from the slopes of Mount Martha in a travelling car and it is night time. No, it is not the chaos of twinkling lights but that throbbing glow of the city caught on some low cloud formation, the glow of the continuing and renewing creative life of millions. And, at night, perhaps in the stillness of a park or these University grounds, a mysterious humming sound may be detected, the life of the city — just traffic noise to the analytic mind— but sometimes it seems more than that. It lives. It can never die.

The vision of a city stays with me. To step apart from her yet still be within her bounds I could climb another hill, and from the heights of Studley Park look across the river and the mess of little streets, to see once more the climax of the Eastern Hill, the towers, domes and spires. Is not this the most beautiful skyline in the land? Affection may blind, but the eyes of love see the past, present and future as one. The blemishes are lost in the symmetry and unity of the vision but the experience is never lost. It stays with me when I come down the hill once more and rattle home in a large green tram.

—PETER J. ELLIOTT.

During the holidays I went out into the hills behind my home and sang; I don't mean that I can't sing indoors — I can and do, rather badly — I may even be heard on precious occasions wheezing around these sacred halls; neither had I any desire to imitate the nuns of Hollywood or Miss Julie Andrews. No, I went out into the hills for the simple pleasure of walking. C. S. Lewis once said that he thought walking and talking to be two of the greatest pleasures in life—but that they should never be mixed. I don't agree with him: walking is one of those soothing mechanical exercises, like football, and allows the happy illusion of freedom of mind reflected in one's surroundings; conversation is not compelled, and one says what one wishes to say, always thoughts of great profundity, and then no more . . . the very antithesis of a College sherry party. Walking alone gives ample scope for reflection but during the holidays I hung drapes over the mirrors and ran from reflections. So that is why I was singing in the hills . lingering over the pleasures of thoughtless action for once.

As I plodded along like a happy fool, I became conscious of bird calls all about me. It has been explained to me that the song of the nightingale was not especially important to Keats and I am grateful for this information, for I have listened patiently to any number of birds' songs, including that of the "lightwinged Dryad of the trees", and I have been unable to hear a song, though I will cheerfully call a field melodious and very easily hear the wind in the willows (though I must confess when it comes to a choice between the sounds and the smells of the countryside I'm all for the smells).

These, at any rate, were not the songs that I was hearing: they were loud, harsh calls; they had banished the Gershwin melody from my head and I stood quietly watching the birds dart far above me. There were two in particular who were jesting with the wind, soaring about and behind me. There was an astonishing ease with which they were at once a part of nature and yet vigorously enjoying it, perhaps because it was spring. I am not especially familiar with the courting habits of birds; but I am an optimist and always hopefully assume that when two of any species flirt and enjoy one another's company love might at least have something to do with it.

Yet as I watched them their circlings became lower and I noticed that they were coming more closely to the ground. Quite suddenly one of them swerved towards me and I heard the heavy flapping of its wings just above my head. I began to walk, quickly, and looking hurriedly up again saw that there were now four creatures above me; in violent succession three of them flew, screaming, straight towards me, and I found myself shielding my head with my coat. Again they did it. I walked, almost ran, down the hill toward the road and then they flew off, calling loudly one to another. Finally, as I was nearing home, I heard again the heavy flapping of wings and rushing wind behind me: I ducked and then turned quickly, but could see no bird.

Perhaps it is easy to explain; perhaps the setting sun had shone in my eyes creating jewels for a thieving magpie; perhaps they were heading me away from their nests; maybe my presence had disturbed them. But I was uneasy. Clearly I was alien to their sense of nature: I was an intrusion, not to be ignored but to be driven away with shrieks and cries of indignation and then pagan exultation. Are the mountains then not for man? Are storks and rabbits to live in the valleys and not our virgin daughters? Has man nowhere to go where he may be accepted as part of the natural world?

Nonsense! we exclaim, we have created our own world, a world of civilizations and sophistications; we are progressing away from our rude forefathers. Yet I think we have bound ourselves to the world we have created: man has become obsessed with what he terms his creativity.

"Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air, and over every living thing that moves upon the earth."

They are the words of the "creator" or, at any rate, a poetical conception of the great creative act. The command is to multiply and subdue: well, we have multiplied, with a cheerful enthusiasm, and mankind has subdued nature; but indeed we have done more than that. Let us not modestly avert our eyes or blushingly retire leaving our achievements unspoken for. Not only have we subdued nature; not only have we transformed it to suit our needs; but we have replaced it with our own splendours

... our great cities have risen, crammed with the works that our hands and our mighty minds have wrought. Our own human "creativity" has become the centre of our souls; and then rather pleased with the final result we have defiantly placed ourselves in the centre of it. This, we say, is of ourselves: we can understand a world that we have created: do not disturb us with the harsh beauties of the natural world except on a coloured slide. We have dragged ourselves out of the dirt from which we were created by the great unknown, and are busily washing the dirt away.

Surely we have misunderstood ourselves? The originality of our creations lies not in their essential novelty but in the perception of realities which have always existed, the realities of the created world. The genius of the artist lies in new perception: whether we talk of mathematicians or poets, of architects or musicians, the excitement and fineness of their work lies in their true recognition of the world, a true understanding of reality. Creation in its fittest sense is for the gods. If a man were capable of true creation he would not be understood by his fellow-men: his work would have no basis in the reality which we know; we could merely cry, "Give us the eyes and then we shall see."

As it is, we also are a part of creation: sometimes it seems irritating and humiliating; we must bow to the cabbage if we are to survive, and cultivate the cauliflower as if it were our friend. Yet we are so made that there is the finest proportion between ourselves and the world about us. The finest insights of the human mind do not shriek at the alienation between ourselves and the realities of the natural world; rather, breadth of vision always seeks the totality of all that we know, including ourselves. Perhaps this is why we are not very often left breathless by the world about us: we are so much a part of it that we need more than a view from the top of a hill to see it as it really is. And, anyway, to acknowledge the beauty of the natural world we should have to admit the presence of something magnificent within ourselves, perhaps even of divine origin and that would be a little too terrible. Human nature is responsible it seems for all our mistakes and stupidity; heaven only knows what

is responsible for the rest. Our histories have soured us and made us cynical: the delights of personalities, of humour, of companionship, have become exceptional; our follies and foolishness have become the norm by which we judge ourselves and the world in which we live and move and have our being. The modem writer revels in this wretched ruin; even love he has managed to destroy by grim and frightening associations. To fall in love has thus become the most disturbing accident: it has always been an accident perhaps, surprising and joyful. Yet now we have become unable to admit the possibility of such exquisite affection between such sullied creatures. We have climbed into a cardboard box dragging our intelligence in behind us and closed the lid: reality we no longer accept.

If we would accept ourselves we should at least be at one with the world. We should be able to see the beauties of the world about us; and sing about them: then at least we shall be in sympathy with an evening sky or a shallow stream. Then we can gaze into a pool and see reflections of ourselves whether the water is calm or not.

Unfortunately we have become alien to any suggestion of divine creativity and the work of man no longer seems to be a fresh interpretation. Instead we seize upon it as an alternative to reality. A few men suddenly seem to have become gloriously inspired, of themselves we suppose, and they, whom we can understand rather better than the gods, they shall become our shepherds, we shall not want anything . . . and they it is who shall lead us by the still waters. Except that we tend to forget the still waters and the table spread before us. Instead we gaze with rapt devotion upon these new modern shepherds and study not what they see but the visionary light in their eyes. They have become an alternative to the harsher though sweeter demands of reality.

What we fail to perceive in accepting man's creativity as reality in itself, is that it reflects, often magnificently indeed, the greater glorious reality of the whole world, and that no matter what we ever do on this curious planet, finally all we can say is: A rose is a rose is a rose.

It is hard to make saints interesting; so often they seem to merge absent-mindedly into vague abstractions, with a mocking smile at the artist as they disappear into clouds of glory: sometimes, indeed, they may strike us as downright repulsive and echoes of Uriah Heep's nagging voice are heard prompting our reaction. Robert Bolt's "hero of self-hood" is neither dull nor repulsive; he is a man of sharp wits and subtle whims. His sense of personal individuality and integrity is as powerful as the lust of a king. The importance of Sir Thomas More's qualities is greater in our age than it was when Henry reigned; as diverse a mind as Camus' has seized upon self-hood to explain, or at least make bearable, the human comedy. "A Man For All Seasons" is scarcely limited by the conventions of a tawdry period play. Bolt quietly suggests the period by reference to events and people necessitated by the plot. The dialogue is written in good and lively plain English: we were not forced to listen to those infuriating conversations generally heard in "Tudor" plays:

"Peasant: Hast thou heard that good King Henry hast fallen for another wench? I vow thee none good wilt come of it!

(SUSSEX accent vitally necessary)

2nd Peasant: God's Body!" (any other accent)

—a general mixing of idioms of all ages with a scattering of "thou's", "thee's", and as many topical references in one breath as possible, plus, of course, unstinted allusions to at least the last half-dozen English monarchs.

Bolt concentrates our attention on some halfdozen chief characters, creating them within the context of the play and not of history; otherwise it becomes painfully obvious that the wax is still hot from Marie Tussaud's.

The production in the Chapel was a happy venture: although the innovations were scarcely exciting, occasionally some quite beautiful touch was effected; which is why, if you go into the Chapel late at night one evening you may hear the steps of the chancel being washed by the Thames and the voice of a man crying for a boat. Fortunately the acting was of a very even standard: we did not chew our programmes, nervously anticipating an actor whom we knew would be dreadful; on the contrary, the audience received the play with relaxed appreciation and a confidence in the presentation.

Undoubtedly the sureness of the production was due to David Kendall, though the effect was sustained by the cast. There was an ease of movement, of speech, of reaction, which gave an exciting impression of unity of intention amongst the players; an air of assurance was felt, which the workmanlike construction of the play deserves and encourages.

The most delightful performance was that of Gus Worby as the Common Man: it is not an easy part at all, and not one for which Mr. Worby might seem to be especially suited; but within a few minutes his charm and witty coarseness of interpretation had quite engaged the audience and allowed him to do very much as he liked with the awkward task of stringing the play together along the slender lines of his monologues.

John Brenan's performance was competent: his saintliness was not sickly but rather he allowed the strength of his seeming passivity to triumph over wretched circumstance. There was a certain lack of development in the characterization which provoked admiration and understanding if not sympathy. The physical effort alone of playing such a part is very great indeed; to overcome such a difficulty with grace and ease is an achievement. As his wife, Cathy Forsyth gave an intense performance, lion-like indeed with a golden mane; though a less vehement performance might have allowed a greater poignancy towards the end of the play. Ann Kupa was quietly charming in a not very interesting part, but I found her anguish as More's death approached very moving indeed.

Richard Rich was strikingly ingratiating and the words oozed from his mouth like festering sores: it required a swift change of attitude to applaud Jo Thwaites. The complementary nature of his part to that of John Brenan was nicely discerned, even if occasionally Master Rich did not sound especially like an English gentleman.

I found John Morgan's convulsive performance as Will Roper disconcerting though credible; I was frequently worried that Will Roper would twist himself so much as to fall to the floor in hopeless exhaustion.

Cromwell, played by Ted Blamey, was entertaining in a part which is somewhat wordy. He made long speeches seem worth listening to, though there was scarcely an impression of character lying behind them.

Irrelevance has its delights, and the speech of John Telfer as Chapuy's attendant, so beautifully distorted, was quite unnecessary and very funny.

The other performances were thoughtful and impressive as a vigorous background; though Mr. Elliott's voice seemed in quest of an unknown home-country, his intense under-playing of Wolsey was brilliantly done .

Michael Hamerston and John Harry were pleasing to the eye, and their immensely robust confidence in themselves was quite suited to their roles. David Adcock's voice I found rather lacking in interest, though his easy assurance was quite convincing. Ken Griffiths' cheerfully created caricature was, if accepted as such, most entertaining. Diana Martin came and went quickly: I could not speak for her facial expressions, but her speech emerging from the gloom was an unexpected pleasure.

It was a fortunate choice of play and of setting, but I hope that success will not lead to repetition. The Chapel has some serious defects (acoustics and shape chiefly), which cannot be overcome, and its atmosphere would tend to be the same for any play.

After the play, a forum was held at the University to discuss its success: the general interest in it was great, and it was bitterly torn to pieces then put together again to the satisfaction of an audience comprising chiefly the cast and sound-effects men.

The greatest success of the play came in the College dining hall: for once football, women, College "politics" and apricots lost their place

as chief topics of conversation and the ghosts of literary criticism crawled about the tables.

—GEORGE MYERS.

Amongst the five prizes awarded for University theatre productions over the past twelve months, two went to Trinity's play.

"The Union Council Production Prize", for the best overall production was won by David Kendall for A Man for All Seasons.

"The Union Theatre Repertory Company Prize", for the best individual performance in any play (with the exception of productions by M.U.S.T. and Queen's College), was won by G. R. Worby for his part as "the Common Man".

The Chapel Vestry is now predominantly a group of chapel-goers elected by the Parish Meeting. This, perhaps, is the most important change to have taken place this year. This new system (unlike that which it replaces where the Vestry was self-perpetuating) will mean that able people from Trinity, JCH and Parkville will be elected to the Vestry at one of the bi-annual Parish Meetings.

The first Parish Meeting was held in second term with roughly eighty people present. The meeting appointed a committee to investigate social service projects which could usefully be helped by the TCAC and the Vestry. Among other things, the meeting also decided to change the time of Sunday matins to 10.30 a.m., to recommence "Tuesday Specials" and to ask the Secretary of the Dialectic Society to organize a symposium on Christianity.

Despite the dull form of the Stock Market, there has been a remarkable increase in College giving during the past year. Last year more than $1,300 was donated to the Dogura Mission Hospital Appeal in Papua. Besides this, nearly $1,000 from Chapel collections was donated to various missionary societies both here and abroad. Another College appeal is being held this year, this time for projects in North Queensland and New Guinea, and it seems that last year's total will be surpassed.

One particularly heartening feature of our newly begun social service effort is that many men and women from both Colleges are giving their time and energy to provide practical help where it is needed, here in Carlton and also in New Guinea. In January, the Colleges sent thirty-five students to Papua and New Guinea to help at Anglican Missions, and many of

our men have spent Saturday mornings chopping wood for needy pensioners in Carlton. This College has been insulated from the University and the outside world for too long. It is pleasing that the "I'm all right, Jack" attitude is being dispelled.

The Vestry is considering several changes in the times of services in Chapel, and also in the fabric of the Chapel. It is proposed to experiment with matins at midday on Sundays so that possibly more of the later-rising gentlemen of the D.O.C. will be in a position to attend. A beautiful French harmonium (purchased by the Chaplain and the Warden) has been placed in the Nave, a new bible has been donated by an anonymous donor and a fine new altar cross, decorated by Nicholas Draffin, purchased. Moreover, those who have suffered silently for years will be glad to know that super-soft foam rubber kneelers are being made. The British composer Peter Maxwell Davies is being approached to discover whether we could commission him to write a new setting of the Sung Eucharist.

The condition of the Chapel building itself is causing the Vestry concern. Some renovations have been completed, but there is still much to do. Perhaps the most expensive section is the great west window, which is still being held in position by four wooden beams originally placed there by Mr. Wynne in 1933 as a temporary measure. During Melbourne's rainstorms water has poured through gaps in the window, causing considerable damage.

The Chaplain is taking his well-earned sabbatical leave until the end of second term 1967. He will be studying at the Sorbonne, and later in England. All our best wishes go with him.

—BILLCOWAN.

Connoisseurish taste buds flowed again as throughout the year members of the College were able to maintain an exceptionally high musical standard, both creative and, as our Wigram Allen Prize Essayist would have it, vicarious.

A series of Sunday Salons matured once more from the deep vaults of Nankivellian splendour. He managed to contract many local celebrities, including Mr. Ken Griffiths, who this year successfully avoided the nobblers and repeated his success as a finalist in

the A.B.C. Concerto and Vocal Competition. And, of course, Field and Alexander, those effervescent commentators on the ways and conscience of Everyman, once more delighted the masses with an expanded repertoire and a style now far more poised and engaging.

The College Concert organised by Charles Kemp brought forth the usual array of performers: Robert Peers demonstrated the suitability of the Chapel for string playing with three works for the guitar; Miss Dian Booth (who has generally been enhancing musical life with performances in Chapel and a recital at JCH) played violin works of Bach and Handel; John Shepherd played the "Fantasia" in D minor for organ by Henry Purcell, and the College Choir sang Orlando Gibbons' "This is the Record of John" and William Croft's "God is Gone up with a Merry Noise". Pianist Barry Firth opened Part the Second in the Dining Hall with Bach's "Sinfonie" from the Partita No. 2 in C minor, and a Chopin Etude. Bailey Ann Smith played Debussy's "Syrinx" for Flute, and Di Martin and Cathy Forsyth treated us to Alan Frank's "Duet for Two Clarinets". Excellent performances were heard from pianists Rosemary Hammond, who played a Beethoven Sonata, Mary Rusden, who was able to tear herself away from the catalogue room, and that man again, Ken Griffiths. Ensembles produced interesting effects — Rosalie Atkins, Norma Long and Leona Donnelly played a Mozart trio for Violin, Piano and 'Cello, and the celebrated Bayreuth Festival Orchestra, batoned by K.G.> sparked off new insights. Richard Smith, B.Sc., who now practises in the Music Room with the door open, played 'cello works of Faure and Manuel de Falla. Then the traditional light-hearted song —this time by Peter Hughes and Peter Field— led the thirsting warriors into the valley of gargantuan banqueting pleasures known only to the Romans.

A spontaneous offer from the Warden saw an orgyish Choir Bunundrum at the Lodge — livened up by rather extreme and tasteless items from JCH and the Chaplain, who insisted on familiarizing us all with "La Mer" — which he is on now. Of much more sensitivity and inherent loveliness was the Warden's stirring ballad, recalling those lost years when breeding really was something to sit up at, and the poor really did live underground. Another crudity was that song written by Cathy Forsyth.

At the Play, "Man For All Seasons", the College Choir sang two anthems of Orlando Gibbons' "O Lord Increase My Faith", and the very rarely heard six-part "O Lord in Thy Wrath Rebuke Me Not".

A series of Sunday organ recitals was held in Chapel — an introduction well worth persevering with, as the Trinity organ is certainly one of the finest in Melbourne. Recitalists were Jean-Paul Maki, an American student returning from a year's study in Paris; Sergio de Pieri, who played works of Pasquini, Clerambault, and included Mozart's "Fantasia and Fugue" in F minor for Mechanical Organ, and Britten's "Prelude and Fugue on a theme of Vittoria". The Reverend Michael Wentzell returned for a very successful recital, and Norman Kaye concluded the season with a recital in October. All were very well attended. Lance Hardy, Sergio de Pieri, Andrew MacIntyre and Rodney Wetherell were guests invited to play the concluding voluntary after Mass on Sundays.