Cover Art: 'Bathsheba' by Marc Chagall (1962-62). Public domain, taken from WikiArt.org.

Anastasia Fedosova

Emer O’Hanlon

Aisling Doherty-Madrigal Jack Smyth

Alessandra Aspromonte Jade Brunton Cúán de Búrca Eoghan Conway Caroline Loughlin Felix Vanden Borre

Anastasia Fedosova & Jack Smyth

Dr Peter Arnds

Сны, как известно, чрезвычайно странная вещь: одно представляется с ужасающею ясностью, с ювелирски-мелочною отделкой подробностей, а через другое перескакиваешь, как бы не замечая вовсе, например, через пространство и время. Сны, кажется, стремит не рассудок, а желание, не голова, а сердце, а между тем какие хитрейшие вещи проделывал иногда мой рассудок во сне! “Сон смешного человека”, Достоевский Ф.М.

As is known, dreams are extremely strange things: some incidents are presented with a fearsome clarity, the details crafted by a jeweller, while other parts you leap over as though entirely unaware of, for instance, time and space. Dreams seem to be driven not by reason but by desire, not by the mind but by the heart. And yet, what cunning tricks reason has played on me in a dream!

“The Dream of a Ridiculous Man”, Fyodor Dostoevsky. Translated by Anastasia Fedosova.

It was the prominence of dreams and their significance in the work of Fyodor Dostoevsky that initially inspired me to consider “dreams” as an editorial theme for this issue. Closer to fables or novellas, stories within a story, in Dostoevsky’s novels dreams serve to reveal a hidden level of the characters’ psyche, drive or twist the plot, and convey the author’s philosophy and ideology. Dreams disobey the laws of time, space, and logic. Governed by our heart and most sincere desires, rather than reason, they become spaces where anything is possible and nothing is forbidden: “extremely strange things” indeed.

In a sense, dreams themselves are a form of translation and a form of communication, perhaps the most honest one. Dreams are uncontrollable: a dream materialises not when we want to see it, but when it wants to be seen by us. Dreams carry us across the border into the world governed by our subconscious, that is, dreams translate us (translate comes from Latin trans "across, beyond" + lātus "borne, carried”, thus to translate is to carry over). A space beyond, dreams unite us with our loved ones, even if they are far away, or long gone. Besides, dreams translate reality into signs, symbols, metaphors, and images.

With the theme of “dreams” we, therefore, invited you to turn your gaze inward and confront your own fears, wishes, and fantasies. We encouraged you to break away from societal boundaries and conventions and give way to the unconscious. We wanted you to present us with literary and artistic pieces that would reflect the hidden, but also point at the ideal, the desirable, the longed for. We asked you to show us the ambitions and strivings for the better. We suggested that you introduce us to the state of sick delirium or light reverie. We wanted to see your worst nightmares. We asked — and you listened. You gave us your own interpretation of

dreams, strange, curious, and honest.

In the pages to come, you will be carried across into the realm of dreams. You will find the yearning of a passionate lover and the sorrow of unrequited love; the longing for those who have passed away; the dream as form of death and resurrection; the dream-like narratives of Jewish folklore and the Surrealists’ automatic writing; the ideal of a virtuous human; and of course the literal dreams, the night visions. Amongst others, you will find translations of the work of Franz Kafka, Pablo Neruda, William Shakespeare, Samuel Beckett, W.B. Yeats, Jorge Luis Borges, Wolfgang Borchert, and Seán Hewitt.

You will encounter a series of wonderful illustrations and artworks, grouped in the middle of this issue as a gallery. The piece used for the cover is Marc Chagall’s “Bathsheba”. It is based on the Biblical story which narrates how King David fell in love with a beautiful woman whom he saw when she was bathing, and who turned out to be the wife of Uriah. Smitten by the beautiful bather, David had her husband killed in battle, married Bathsheba, with whom he had a son who would later become King Solomon. Chagall depicts the narrative in a dream-like manner, depicting Bathsheba as a bride, surrounding the couple by angels, flowers, and candles, illuminating the scene by his signature blue tone.

The issue is closed by a critical essay on translation exploring the Italian adaptations of James Joyce’s Dubliners, particularly the theme of dreams in music within the short story collection. We are proud to contribute to the field of literary translation through the publication of this essay, and we will hope to continue to showcase the academic essays exploring this fascinating area and providing us with tools for understanding, defining, and examining different forms of translation.

My gratitude is to my predecessor, Cian, for his trust and faith in me. It is my honour to follow in your steps and build up on your achievements. Thank you also to Andrea and Oisín, with whom we worked together under Cian’s guidance, for their continuous support, warm words, and contributions to this issue. None of this would have been possible without the members of my excellent editorial team. Thank you to Emer, Cúán, Alessandra, Caroline, Eoghan, Felix, and Jade for your dedication, reliability, and professionalism. My immense gratitude is to Aisling, who devoted her time and energy to this journal at times most challenging for me in spite of temporal and geographical distance between us. To my marvellous Art editor, Jack, thank you for being there every step of the way: for realising every crazy idea of mine in your wonderful artworks, for navigating me through the hurdles of layout, and for so much more that remains unseen in the pages. My gratitude is also to Dr Peter Arnds, the ever-supportive advisor of this journal.

Lastly, thank you to all of the contributors for your passion, creativity, and drive: you never cease to astonish us with your talent. And thank you to you, reader. Read on. Read on, tread on the pages of this journal, only …Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Anastasia Fedosova‘Il souhaite les tissus du ciel ’ trans. by Aisling Doherty-Madrigal

In this dreamlike poem, the speaker talks of what he longs to give to his love. He wishes to be able to provide them with the impossible and the beautiful – the very cloths of the heavens themselves – but, being poor, offers the most valuable thing he possesses: his dreams.

‘Prelude’ trans. by Octavio Pérez Sánchez

Poetic dream, delirious prose, epiphanic vision: “Preludio” develops a sombre theme through a series of fantastic images. As the opening text of La Torre de Timón, Ramos Sucre’s collection of historical reflections, poetical images and visions, this text exemplifies the author’s sensibility and his careful treatment of language.

‘Reality’ trans. by Arianna Bettin

In ‘Reality’ (1993), Wisława Szymborska defines reality by juxtaposing it with dreams in a modernist and existential context. Dreams are seen as a means to pull back from an unleavable reality, and as a safe place, that we can decide to leave at any time.

‘Searched and Pined’ trans. by Frøya Mostue-Thomas & Matthew James Hodgson Sigbjørn Obstfelder is considered the first modernist poet of Norway. His work explores the im possibility of proximity, and the simultaneous distance and paralysis of intimacy. The speaker of this poem is arrested in a dream-like trance while discovering the disconnect between dreamed versions of reality and reality itself.

‘She Stood on the Bridge’ trans. by Frøya Mostue-Thomas & Matthew James Hodgson

The refrain of this poem, “facing me,” creates a counterpoint to the content by suggesting for wardness or directness. Most of the poem, however, offers us a sensitive and observant speaker caught in a dreamy state of curiosity about the woman in white on the bridge.

‘A Dream’ trans. by Adrianna Rokita

The title reflects Miron Białoszewski’s experience of an impossible love in communist Warsaw which results in an absurdist piece. My translation retains all the essential linguistic, rhythmic and stylistic features that highlight the poem’s oneiric quality and reflect the idea of fusing reality with imagination.

‘Strach z létání’ trans. by Michaela Králová

One interpretation of “Fear of Flying” is that it explores the yearning for one of your friends. Whether the poem represents the dream of coming out, or day-dreams about one particular woman, Hacker manages to convey a strong longing for the love of the narrator's dreams.

‘Chování koťat o tom, že chováte děti III’ trans. by Michaela Králová

Marilyn Hacker remains of a pivotal figure of anglophone lesbian poetry. Her poem ‘Having Kittens About Having Babies III’ explores the dream of having children. By focusing on chil drearing, Hacker transcends the pure erotics within the queer community, hence representing a distinctly subversive dream/act.

‘Never will I gaze upon the woman’ trans. by Kinga Jurkiewicz

This is a queer love poem written by a female Polish poet a century ago. She reflects on the impossibility of romantic love between women in her time, but nonetheless dreams that one day, a century after her, it will bloom, be possible.

‘To Walk Further Along the Path ’ trans. by Tyan Priss

This excerpt of bonus content from Pierre Bottero’s famous Ellana trilogy showcases the ways of the Shadowalkers: reality-defying rogues who roam the world freely, inconsistent as reveries. This translation, which aims to convey Bottero’s poetry and imagination, is a venture into the most dream-like of literary genres: fantasy.

‘Sublimely Frank’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

To the eternal day-dreamer or away-dreaming me, the theme of this issue has a mesmerising appeal. Emotion is often the core of a poem, while the form can grow around it naturally. The bold blend of profound feelings and a humorous touch always draws me in.

‘Touched between dreams’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

On TV, a best-selling author said: ‘When you write outdoors, you’re no true writer.’ Poor bloke, I disagree impolitely and boldly: you don’t know what you’re missing.

‘A Meek Dream’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

This teasing little “real-life dream” is a playful example of the way a poem can truly “write itself” and the author becomes the audience, trying to interfere or steer all the same – with a smile. Enough self-mockery?

‘Sogno di una notte di mezza estate’ trans. by Martina Giambanco

The title of A Midsummer Night’s Dream speaks for itself. The motif of dreams is used to explain the strange events of the night, and the oneiric atmosphere imbues the comedy with a sense of illusion and gauzy fragility. In this scene, Titania wakes up from the spell which had made her fall in love with Bottom, believing it a dream.

‘Dream’ trans. by Kinga Jurkiewicz

This poem evokes the experience of dreaming, both through the constantly transforming images, as well as its halting rhythm and ample use of ellipsis. We walk towards a waiting lover through an evolving fantastical landscape, only to stumble and wake up in the last line, departing the dreaming world.

‘An Bhrionglóid’ trans. by Aoibh Ní

The title means “The Dream”, and the dreamlike nature of this scene allows the mostly realistic play to take on a temporary supernatural element, providing a distancing effect for the rather brutal things the Elbe says to Beckmann.

‘I'm Scared’ trans. by Joseph Shaw

In ‘Tengo Miedo,’ the dream, which will not fit in the speaker’s head, is unleashed on the rest of the poem, crowding out their unvoiced shout and letting the universe die its slow death. Incredi bly, it was written by Neruda at the age of thirteen!

‘

Kafka a la orilla ’ trans. by Aisling Doherty-Madrigal

This is an excerpt from Murakami’s Kafka on the Shore. In this section, Kafka, a fifteenyear-old boy who has run away from home, enters a beautiful library he has long dreamed of visiting. He realises that this is exactly the refuge he has always wished for, and he begins to hope for a better life. I believe this fits beautifully with this issue’s theme because not only does this particular extract deal with Kafka’s dreams and desires, but the book it is taken from is surrealistic and dream-like in its own right.

‘Alone and Unmoving’ trans. by Ioana Răducu

Employing surrealist automatism, Gellu Naum explores a dream-like realm where the eerie and the nonsensical are understood as intimate projections of the unconscious. A fragmented self strives to make sense of personal experience through unrestrained language and amalgamations of bizarre images, urging a momentary renunciation of rationality.

‘Dream’ trans. by Isabela Facci Torezan

This is a short poem featured in Rosana Rios's children's book "Cheiro de Chuva". The poem refers to dreams we have when we sleep as well as our aspirations and hopes. Dreams are portrayed as not always happy: sometimes the journey to "follow our dreams'' is full of sadness and tears.

‘Connemara’ trans. by Andrea Bergantino

There is an oneiric tone to this poem by Seán Hewitt, at times eerie, halfway between a dream and a nightmare. “Connemara” revolves around the tension between the lyrical I’s circum scribed perception and the pervasive presence of the personified dark, leading to a final moment of communion.

‘Lao Décheannach’ trans. by Adam Dunbar

I believe this poem captures the hope and otherworldly aspects of dreams. Although the calf is destined to die, in these few hours he can admire and appreciate his perfect dream-like night. Being a very nature-heavy poem, Irish suits it perfectly.

‘Having and Being’ trans. by Arno Bohlmeijer

As Ed Hoornik was a devoted poet and married to a good friend of my mother’s, it’s a special honour to translate his work. In view of his hardships during and after WWII, this poem is particularly strong, having ‘wish-dream’ written all over it.

贝克特’trans. by Bowen Wang

It was in Pan Pan’s promenade adaptation at Dublin’s Project Arts Centre that for the first time I read and immersively experienced this radio play. Dislocated from reality (perhaps in a dream), Beckett’s fragmented, sleep-talking narrative forces us into a labyrinthine space as we navigate an inner journey through our egos and selves.

‘Poetic Art’ trans. by Ana Olivares Muñoz-Ledo

Horace’s Ars Poetica speaks of creation, how to seek inspiration and what it means to create. Jorge Luis Borges replied to this same idea in the poem Arte poética [Poetic Art]. A dream is a type of death to which we go every night in search for inspiration, in search for ourselves.

Minding Gran

During the ceremony announcing the new city poet laureate, I was a nervous nominee, and Eva Gerlach was a celebrity guest, reading her awarded work.

Her quietly first-class performance calmed me down. Her lovely dream here can make people stay - even after they’re gone.

‘Brionglóid na bhFear Cill Mhantán’ trans.

This is a translation of the first and last verses from a poem written by my grandfather Eddie O’Byrne, based on a dream he had that his home county of Wicklow had won the All-Ireland final. It’s fascinating how both female and male sportspeople are included in his ideal team.

‘A Dream’ trans. by Nicholas Johnson

Franz Kafka (1883–1924) uses this short text, framed as a dream, to link artistic productivity and the fear of death. Written before 21 June 1916 (the date on which Max Brod first sent the typescript to Martin Buber), this parable was first published in Das jüdische Prag (December 1916).

‘Ná Caill Do Mhisneach’ trans. by Oisín Thomas Morrin

Like Miyazawa Kenji, we all strive to become a better person - kinder, wiser and more loving. In this short poem, from his sick bed, Kenji lays out the dream of the ideal virtuous human he longs to become.

‘Hasidic Stories’ trans. by Itamar Shalev

The Hasidic Story is a sub-genre in the Jewish oral tradition of storytelling and hagiography, originating from 18th century Eastern Europe. Hasidic stories are usually dreamlike in more than one sense. They are short, fragmented, picturesque, cryptic, physically impossible, and endlessly (un)interpretable. It has to mean something— but what?

‘Memory at Last’ trans. by Arianna Bettin

In this poem, Wisława Szymborska explores the unreachability of both memory and dreams, as they are constantly present in our lives but out of our reach. Yet, through dreams, Wisława Szymborska meets again her deceased parents, re-establishing harmony between her conscious and unconscious halves.

‘The first landing of Dubliners by James Joyce in Italy. A comparative analysis between "Eveline", "Clay" and "The Dead" in their four leading Italian translations.’ A critical essay by Sara Begali.

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths, Enwrought with golden and silver light, The blue and the dim and the dark cloths Of night and light and the half-light, I would spread the cloths under your feet: But I, being poor, have only my dreams; I have spread my dreams under your feet; Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Si j’avais les tissus brodés des cieux, Ornés de lumière dorée et argentée, Les tissus bleus et foncés et ombreux De la nuit, de la lumière, de l’avant-soirée, J’étendrais les tissus sous vos pieds: Mais, étant pauvre, je n’ai que mes rêves; J’ai étendu mes rêves sous vos pieds; Marchez doucement, vous marchez sur mes rêves.

Yo quisiera estar entre vacías tinieblas, porque el mundo lastima cruelmente mis sentidos y la vida me aflige, impertinente amada que me cuenta amarguras.

Entonces me habrán abandonado los recuerdos: ahora huyen y vuelven con el ritmo de infatigables olas y son lobos aullantes en la noche que cubre el desierto de nieve.

El movimiento, signo molesto de la realidad, respeta mi fantástico asilo; mas yo lo habré escalado de brazo con la muerte. Ella es una blanca Beatriz, y, de pies sobre el creciente de la luna, visitará la mar de mis dolores. Bajo su hechizo reposaré eternamente y no lamentaré más la ofendida belleza o el imposible amor.

I wish to be amidst empty darkness, for the world cruelly hurts my senses and life itself afflicts me: insolent lover whose whispers bring me bitterness.

Then my memories would desert me: now they flee and come back with the rhythm of tireless waves; they are wolves howling as the night blankets the desert with snow.

Movement, that vexing sign of reality, heeds my fantastic sanctuary; but I will have climbed from it arm in arm with death. She is a white Beatrice who, standing atop the moon’s crescent, will visit the sea of my pain. Under her spell I will lie forever, and no longer shall I lament slighted beauty nor unattainable love.

Jawa nie pierzcha jak pierzchają sny. Żaden szmer, żaden dzwonek nie rozprasza jej, żaden krzyk ani łoskot z niej nie zrywa.

Mętne i wieloznaczne są obrazy w snach, co daje się tłumaczyć na dużo różnych sposobów. Jawa oznacza jawę, a to największa zagadka.

Do snów są klucze. Jawa otwiera się sama i nie daje się domknąć. Sypią się z niej świadectwa szkolne i gwiazdy, wypadają motyle i dusze starych żelazek, bezgłowe czapki i czerepy chmur.

Powstaje z tego rebus nie do rozwiązania.

Bez nas snów by nie było. Ten, bez którego nie byłoby jawy jest nieznany, a produkt jego bezsenności udziela się każdemu, kto się budzi.

To nie sny są szalone, szalona jest jawa, choćby przez upór, z jakim trzyma się biegu wydarzeń.

W snach żyje jeszcze nasz niedawno zmarły, cieszy się nawet zdrowiem i odzyskaną młodością. Jawa kładzie przed nami jego martwe ciało. Jawa nie cofa się ani o krok.

Zwiewność snów powoduje, że pamięć łatwo otrząsa się z nich. Jawa nie musi bać się zapomnienia. Twarda z niej sztuka. Siedzi nam na karku, ciąży na sercu, wali się pod nogi.

Nie ma od niej ucieczki, bo w każdej nam towarzyszy. I nie ma takiej stacji na trasie naszej podróży, gdzie by na nas nie czekała.

Reality doesn’t scuttle away the way dreams do. No murmur or ringing disturbs it, no cry or rumble can disrupt it.

In dreams images are hazy and ambiguous, and can be explained in many different ways. But this is a bigger riddle, reality means reality.

Reality has the keys to dreams. But reality can open itself and cannot be closed. School reports and stars are falling in, butterflies and old flatirons are falling upon, headless caps and scraps of clouds. An unsolvable riddle arises from them.

Dreams would not exist, if it weren’t for us. But the one, who is essential for reality, has yet to be known, and the result of his insomnia is shared with everyone, who wakes up.

It’s not that dreams are crazy, it’s reality that is crazy, maybe for its stubbornness, with which it sticks to the train of events.

In dreams our recently deceased are still alive, they can even enjoy their health and take back their youth. Reality lays their dead bodies before us. Reality is not falling back.

The vividness of dreams makes it easy for the memory to shake them off… Oblivion doesn’t scare reality. It's a tough one. It sits on our necks, rests on our hearts, unravels under our feet.

There is no escape from reality, it tags along behind each of us. And there is no stop on the route of our journey where it’s not waiting for us.

Har gaat og higet mod varme øine, hvori livsens glød funkler, mens kastanjelokker dunkler solhud.

Har gaat og higet mod kys, mod favntag! hvori livsens glød brænder og de sorte øine tænder solild!

— Inat kom min brud mig imøde. Hendes livsens glød var slukket, hendes favn, hendes mund lukket, ligbleg.

For warm eyes: searched and pined, inside of which life’s glow alights, where chestnut-coloured hair remained hiding the sun-kissed skin.

Searched and pined, for a soft kiss, embrace, inside of which life’s glow burns brightly, grows older, and the darkness in those eyes, sunbursts amongst the blue!

— Last night, my warm eyes came to me. Her glow was faded, incomplete, and her embrace, her lips: concealed, bloodless, fresh-fallen snow.

Hun stod paa bryggen i solskjærmskyggen, viftende hvidt mod mig.

Hun havde ilet! Hun havde stilet skiftende skridt mod mig

Og derfor sødmen ved halsens rødmen strøg sig saa blidt mod mig

Og derfor navnet ved nye havne smøg sig saa tidt mod mig.

She stood on the bridge hidden by the shape of a parasol, in one motion swept, wearing white, facing me.

She had a hasty stride, where was she off to? Strange pride, changing pace with each step, facing me.

And when the sweetness of her blush, gentle caress, overcame my sense, my touch, she was facing me.

And now, it is the names arisen of new piers I witness which sneak up so quickly facing me.

I ja trochę nie żyję, I ty trochę nie żyjesz. Wpadasz, szybę wybijesz. Ja leżę. A ty fruwasz, Fruwasz, wyczuwasz, fruwasz, Całujesz mnie i witasz. Ja leżę. Wierzę. A ty znów nad poduszką, Troszeczkę za płaściutko I za-nad głową, Ale nie papierowo, A po ludzku i rzewnie, Więc czuję to tak pewnie. Wzruszam się do zazdrości O ludzi, o gości, o coś, Bez słów graty wywracam Pół na niby, pół wściekle, Zabić ciebie? Czy meble?

I buch: ten żal do siebie: Budzę się, nie ma ciebie. Leżę. Tramwaje, świat, Dzień. Z ciebie ani cień. Ty ani tak, ani tak, Już nie żyjesz pięć lat. Wiesz o tym? Wiesz?

A ja coś podejrzewam, Że nie tylko na ciebie Tak się gniewam. Oj tak. Bo to coś ty, Ale nie tak zupełnie, Coś kimś żywym, żywym, żywym (Tak. Pewnie...)

Sztukowało się coś. I tak myślę i badam, I już przez okno wpadam Do ciebie, bo ty — w łóżku A ja fruwam za bardzo, A chcę być tuż tuż.

I już Wyciągam ręce w dół, A ty po mnie — w górę, Łapiesz mnie wpół. Ściągasz. I ja cię witam, I oczy ci odmykam, Bez mowy. Ty przy tym Trzymasz mnie, żebym Pod sufitem znów nie był.

A potem zazdrość, szczęście, Podniecenie, leżenie Czy lecenie, co jeszcze? Niewiele, i się budzę, I trudzę, to rymuję, Samo się potrzebuje. Rymy. A solidarność Plus mizerność, niezdarność, Niewierność — no. Fruwam sam przy suficie. Dmuch, dmucham w ciebie życie? I czy to to jest na to? A jak nie to, to co? Już będzie szóste lato Szło... Wiesz? Skąd?

I’m a little dead, And you’re a little dead. You come and break the glass. I lie down. You fly, You fly, feel and fly, You kiss me and say ‘Hi’. I lie down. I keep my faith. And you, again, over a pillow, A little too flat And beyond your head, But not in a paper way, But in a humane and tenderly way, So I feel so firmly, And it moves me to the point of envy, About people and guests and what ever else, Without words I overturn the junk Half pretend, half irked, Should I kill you? Or should I kill the furniture?

Biff! I feel grief because of you: I wake up and you’re not there, I lie down. The trams, the world, Another day. No shadow of you left. You’re neither this, nor that, You’ve been dead for five years’ time. Do you know this? Do you?

And I’m suspecting something, That it’s not just you I’m angry with. Oh yes, because that something is you

by Adrianna RokitaBut not quite still, Something alive, alive, alive (Yes. Perhaps…) Something was piecing itself togeth er.

And I think and I inspect, And through the window I fall To you, because you are - in bed And I’m flying too much Wanting to be close by, And within sight.

And now

I stretch out my arms to the ground, And you follow me – to the sky, You catch me in half. You drag me down. And I greet you, And open your eyes, Without speech. Meanwhile you Hold me down, so that I’m not under the ceiling Again.

And then envy, joy, Excitement, lying down, Or flying, what else? Not much so I wake up, I toil away so I rhyme, It’s an inevitable pastime. Rhymes. And like-mindedness, Plus ordinariness, clumsiness, Fickleness - yes.

I fly alone under the ceiling.

Tramwaje. Jadą, jadą, Bo to nie dom. Nocleg na Żoliborzu. Z tobą gorzej. Ja ulatuję, jak leżę, Od nóg, już sen mnie bierze, A za plecami deszcz cz cz. Ja zbieram po przystankach Raz Żoliborz — Śródmieście Ćśśś... Raz Żoliborz — Bielany Od różnych spotykanych Dla ciebie życie ćśśś... Po prośbie, ale chytrze, Bo trzeba rąk dotykać, Ale tych co się chce.

Puff, do I puff life into you?

And is this what this is for?

And if not, then what is it for?

Soon it’s going to be the sixth summer. It was coming… did you know?

Where from?

Trams. They go and they go. Because this is not their home.

A night in Żoliborz. You keep getting worse. I escape when I lie down, From legs up, the dream is seizing me up, And behind my back, ssshoooweeeeryyy rain

I collect around the stations

One time Żoliborz - Downtown Squeaaaaak!

Another time Żoliborz - Bielany

From many lives encountered, A life for you is squeaaaaak!

A request after, however slyly, Because one must touch other hands, But only when one wants to touch them oneself.

I won’t go down in flames till I’ve gone down on you. I won’t go down anyway except in your brushfire. I would say, stay with me tonight. I wouldn’t say no. I’ve done the peephole-watch where you stride off like Shane. If I wake up at wolf-hour, cub, I want to suck my fingers that taste of your cunt, and gently infiltrate the tangled mane around your sleepy face, and tug and stroke and lick you just awake enough to start over. But there’s been enough wind-change warning to counsel having a good line for parting in separate cabs at midnight with a joke: “Night, angel—call me later in the morning.”

Plameny pekel mě nebudou oblizovat, dokavaď já nevylížu tebe. Do horoucích pekel mě neuhraneš, to leda skrze tvá rozpálená křoviska. Řekla bych, ať zůstaneš dnes večer se mnou. Neřekla bych ti ne. Už jsem na tebe skrze kukátko zírala, kdy rázně odcházíš jako Shane. Když se probudím ve vlčí hodinu, mládě, chci sát své prsty, které chutnají po tvé kundě, a něžně prostoupit do té zamotané hřívy kolem tvého ospalého obličeje, a tahat a hladit a lízat tě až se probudíš jen natolik, abychom mohli začít nanovo. Ale varování před změnou větru bylo dostatek na to nás ponaučit, že bychom měly mít připravenou repliku na rozloučení, každá ve svém vlastním půlnočním taxíku, s vtípkem: "Dobrou – zavolej mi pak ráno, zlato."

They get to make their loves the focal point of Real Life: last names, trust funds, architecture, reify them; while we are, they conjecture, erotic frissons, birds of passage, quaint embellishments in margins. Self-restraint is failing me, and you, dear heart, suspect your old trout’s about to launch into a lecture. Give me a serious long kiss. I ain’t. Give me another one. Look what we’re making, besides love (that has a name to speak). Its very openness keeps it from harm, or perhaps it wears our live-nerved skin as armor, out in the world arranging mountains, naked as some dream of Cousin William Blake.

Mohou ze svých lásek udělat ústřední bod svého Skutečného Života: příjmení, svěřenské fondy, architekturu, vyspraví si je; zatímco my jsme, oni staví pro domněnky rezidenturu, erotické frissony, přelétaví ptáci, kuriózní, k mání, ozdoby na okrajích. Sebeovládání ve mně selhává a ty, drahé srdce, podezříváš svou starou babiznu, že chce ti udělat přednášku. Dej mi vážný, dlouhý polibek. Nejsem k mání. Dej mi další. Podívejte se, co děláme, kromě lásky (která má jméno tak říkajíc). Její samotná otevřenost jí brání v poškození, nebo možná nosí naši kůži – živé nervy – jako brnění, venku v horách, které přerovnávají svět, nahá jako nějaký sen bratrance Williama Blakea.

Nigdy w oczy nie spojrzę kobiecie (w sto lat po mnie zakwitną krokusy), nigdy w oczy nie spojrzę kobiecie, w której dusza ma chodzi po świecie.

Ja, co łzy jej zważyłam w mej piersi (w sto lat po mnie zakwitną fijołki), ja, co łzy jej zważyłam w mej piersi, jak nie czynią druhowie najszczersi –

ja, co jedna słuchałam cierpliwie (w sto lat po mnie zakwitną jabłonie), ja, co jedna słuchałam cierpliwie o jej życia radości i dziwie –

nigdy ust jej nie dotknę ustami (w sto lat po mnie zakwitną jaśminy), nigdy ust jej nie dotknę ustami ni włosów nie obleję łzami.

Never will I gaze upon the woman (a century after me crocuses will bloom), never will I gaze upon the woman, who carries my soul with her.

I, who weighed her tears in my breast (a century after me violets will bloom), I, who weighed her tears in my breast, unlike even the truest of friends –

I, the only one who listened patiently (a century after me apple trees will bloom), I, the only one who listened patiently to her life’s joys and strangeness –will never touch her lips with mine (a century after me jasmine will bloom), will never touch her lips with mine nor soak her hair with my tears.

Se glisser derrière l’ombre de la lune.

Rêver le vent.

Chevaucher la brume. Découvrir la frontière absolue. La franchir.

D’une phrase, lier la Terre aux étoiles. Danser sur ce lien. Capter la lumière. Vivre l’ombre. Tendre vers l’harmonie. Toujours.

Aux confins du monde connu, là où les frontières des empires humains pâlis sent jusqu’à ne plus être que d’aléatoires tracés sur les cartes d’explorateurs devenus fous depuis longtemps, là où les légendes sont tissées avec des fils de vérité et où la vérité vacille devant l’inconnu, là se dresse une montagne solitaire. Défi lancé au ciel tel un arrogant doigt de roche adamantine, elle transperce les nuages et tutoie les étoiles.

Une caverne s’ouvre près de son sommet, bouche noire et béante d’où s’échap pent des relents de souffre, des lueurs rougeoyantes et, la nuit venue, d’ef frayants grondements.

Des chevaliers montent la garde devant cet antre obscur. Figés dans d’étranges postures, ils sont vêtus d’armures qui furent naguère étincelantes. Le plus impressionnant d’entre eux est un colosse brandissant une hache de combat et un écu au blason devenu illisible. Qu’il pleuve, vente ou neige, il demeure immobile.

Comme ses compagnons, il est mort.

Slip behind the moon’s shadow. Daydream the wind. Ride the mist. Find the absolute boundary. Cross it.

In a single sentence, bind the Earth to the stars. Dance on that bond. Harness the light. Live the darkness. Strive for harmony. Always. ***

At the very end of the familiar world, where the borders of human empires pale into mere variables drawn on the maps of explorers long-turned mad; where legends are woven with threads of truth and where truth flickers before the unknown; there stands a lonely peak. A challenge to the sky, an arrogant finger of diamond-like stone: it pierces through the clouds to flirt with the starlight.

A cavern opens up at its top. Its dark, gaping mouth exhales a sulphury stench, burning red glows; and, at night, frightening growls.

Knights watch over the sombre den. Frozen in strange poses, they wear arm ors that once shone and glimmered. The most impressive of them is a giant brandishing an axe and a shield adorned with a now-unrecognisable coat of arms. He stands still through rainfall, wind and snowstorms.

Like his companions, he is dead.

The visor of his helmet is pulled down. His flesh has melted under hellish

Si la visière de son heaume n’était pas baissée et si sa chair n’avait pas fondu sous feux de l’enfer, on lirait dans son regard une terreur si totale qu’elle est devenue folie.

Aucun bruit sur la montagne. Aucun mouvement. La mort et le silence.

Une silhouette se glisse pourtant entre les corps pétrifiés des héros oubliés. Légère, indécelable, elle pénètre dans la caverne. L’obscurité n’a aucun effet sur la grâce de son pas.

Elle avance, aussi précise qu’une flèche. Aussi silencieuse qu’une ombre. ***

Sous la montagne, le dragon sommeille. gé de cinq mille ans, il repose sur un extraordinaire monceau d’or et de bijoux, de pierres rutilantes qui cascadent sous ses ailes repliées, de parures scintillantes et de joyaux mirifiques. Trésor inestimable pour lequel des rois, par dizaines, se sont damnés.

La puissance des grands anciens coule dans ses veines tandis que la magie originelle enveloppe son corps d’une aura bleuté. Il veille sur son butin. Red outable sentinelle, capable de déceler le moindre bruit, la moindre présence sur une incroyable distance et de réduire en cendres n’importe quel intrus, voleur audacieux ou armée conquérante.

Il ne bronche cependant pas et ses paupières restent closes lorsque l’ombre pénètre dans son antre. Fine silhouette vêtue de cuir souple, elle s’approche sans crainte de la titanesque créature. Elle n’accorde pas un regard aux rich esses qu’elle foule.

Nulle lame, nulle flèche n’a jamais effleuré le Dragon, aucun contact humain n’a jamais souillé ses écailles brillantes.

La main d’Ellundril Chariakin se pose sur son cou.

fires. If not, one would read in his eyes a terror so absolute it turned into luna cy.

No sound disturbs the peak. No movement. Death entwined with silence.

Regardless, a silhouette slips between the petrified bodies of the forgotten heroes.

Feather-light, there-yet-not, she traipses into the cave. Darkness has no grip on her, on the elegance of her step. She moves forward, precise as an arrow. Soundless as a shadow.

***

Under the mountain, the Dragon slumbers. Now five thousand years old, he rests upon an unequalled tumulus of gold and fineries, of blood-red stones that stream beneath his folded wings, of glittering jewellery and dazzling precious gems. A priceless treasure that kings, dozens upon dozens, sold their souls to try and acquire.

The power of the old ones runs through his veins as magic–the very first to exist–coats his body in a blue-hued aura. He guards his gold. A formidable sentinel, capable of detecting the faintest noise or presence from miles away, of turning to ashes any trespasser, be it an emboldened thief or a conquering army.

And yet, he neither moves nor lifts his eyelids when the shadow enters his lair. She is thin, clad in soft leather, fearless as she approaches the titanesque creature. She does not spare a glance to the riches she treads on.

No blade, no arrow has ever grazed the Dragon. No human touch has ever soiled the lustre of his scales.

Ellundril Chariakin lays a hand upon his neck.

Lorsqu’il ouvre les yeux, alerté par un sens surnaturel, le Dragon est seul. Il comprend instantanément.

Que quelqu’un est venu.

Que quelqu’un est reparti. Que rien ne lui a été volé.

Que quelque chose lui a été apporté.

Un message. Écrit en lettres flamboyantes sur le mur qui lui fait face: Beauté du geste libre

Supériorité de l’esprit sur la force Rire.

When he opens his eyes, alerted by an otherworldly sense, the Dragon is alone. Immediately, he understands.

Understands that someone came. That someone left. That nothing was stolen. That something was given. A message. Written in vivid letters on the wall in front of him: Beauty of the unbinded act

Spirit over strength Laughter.

Er komt een vreemde meneer, of nee, een onbekende man arriveert in mijn besloten droom

en laat graag toe, min of meer, in vierde instantie, dat mijn naakte zij hem raakt, hier of waar.

Maar hij moet een beetje huilen. Warme en stille tranen vleien zich tegen milde verbazing, die het zou willen vragen: Waarom?

Geen behoefte aan een held, kom je me wel tegemoet?

Blote voeten op naakt gras in beweging, voelen het leven van de aarde tot nieuw zeeland, ieder blaadje van boom en bloem, dat viel toen de wind nog doodstil bleef liggen van hoop of groot en moedig liefs, dat samengaat met vergeving, die me teder laat weten.

A strange man arrives, no, I mean a stranger comes by to my private dream.

In the fourth instance he more or less allows my sore and bare skin to touch him anywhere.

But lightly he’s crying. Quiet and warm tears lie mildly on my surprise, that would like to ask why.

You don’t need be a hero; could you meet me halfway?

Nude feet in the naked field move along and feel the life in the earth, to new sea-land, each leaf of flowers and trees, fallen before the breeze went all still, in hope of brave tenderness to show and let me know gently about redemption.

by Arno BohlmeijerDe wind is hard warm, één zintuig maakt hij van je huid en haar, waait een kier naar binnen en vindt… wat geen mens heeft gekend.

Omdat niemand het zocht of zag?

In de zon van dit groene land wil ik languit een dutje doen, met gesloten oren en ogen.

Grenzend aan droom/wens vallen blaadjes daar hier, weer en meer op mijn blote lijf, komen pootjes van een dier, zacht als in een sprookje?

Nee, het zijn de vingertoppen van klaarlichte dag, een schitterend slot of begin, dat me niet zo bang wou maken.

The wind is a warm force, your skin, hair and soul become a single sense.

It blows a chink inside, and finds… what no human has known.

Because they didn’t see or seek?

In the sun of this green land I’d like to rest, stretched and free at full length, closing my eyes and ears.

In wish or dream a leaf is falling there here, again and more on my bare skin, and tiny feet of a creature arrive as sweetly as in a fairy tale?

No, it’s the fingertips of broad daylight, a bright finish or beginning, that tried not to give me this fright.

Wees maar niet bang dat ik ijdel arrogant word, naast brede schoenen loop. Als ik één moment of twee aan succes denk, bekendheid, erkenning, publicatie, recensie,

snijdt een vel manuscript mij in de vinger. Wel de linker (niet degene die schrijft) en het bloeden valt mee, pijn en schrik gaan voorbij, dus wie weet… Is het minder symbolisch of ironisch dan het lijkt?

O, dertien regels: negatief teken. Nee, kijk, is al verleden tijd.

Please, don’t be afraid that I’ll get vain, arrogant, bragging, glary, carried away. The very minute or two I dare even think of success, recognized, published, reviewed,

a sharp sheet of manuscript cuts me, comes back to bite. It’s the left hand, not the one that writes, thankfully, and the bleeding looks treatable, the pain and scare nearly pass. Who knows, it might be less ironic and symbolic than it would appear.

Another freaky fright: there seem to be thirteen lines here. No, were, right?

by Arno BohlmeijerEnter PUCK.

OBERON [Coming forward.]

Welcome, good Robin. Seest thou this sweet sight? Her dotage now I do begin to pity; For, meeting her of late behind the wood Seeking sweet favours for this hateful fool, I did upbraid her and fall out with her, For she his hairy temples then had rounded With coronet of fresh and fragrant flowers; And that same dew, which sometime on the buds Was wont to swell like round and orient pearls, Stood now within the pretty flowerets' eyes Like tears that did their own disgrace bewail.

When I had at my pleasure taunted her, And she in mild terms begged my patience, I then did ask of her her changeling child, Which straight she gave me, and her fairy sent To bear him to my bower in Fairyland. And now I have the boy, I will undo This hateful imperfection of her eyes. And, gentle Puck, take this transformed scalp From off the head of this Athenian swain, That, he awaking when the other do, May all to Athens back again repair, And think no more of this night's accidents But as the fierce vexation of a dream. But first I will release the Fairy Queen. [Squeezing a herb on Titania’s eyes.]

Be as thou wast wont to be; See as thou wast wont to see.

Dian's bud o'er Cupid's flower Hath such force and blessed power. Now, my Titania, wake you, my sweet Queen!

Entra PUCK. OBERON [Avvicinandosi.]

Benvenuto, buon Robin. Vedi questa scena deliziosa? Ora comincio a provare pietà per la sua stupidità; Poiché, incontrandola pocanzi dietro il bosco Alla ricerca di dolci primizie per quest’odioso sciocco, L’ho rimproverata ed abbiamo discusso, Dato che lei aveva a quel punto ornato le sue tempie pelose Con una ghirlanda di fiori freschi e fragranti; E quella stessa rugiada, che talvolta nei boccioli Era solita gonfiarsi come rotonde perle orientali, Stava quindi negli occhi di quei graziosi fiorellini Come lacrime che piangevano della loro stessa disgrazia. Quando io l’avevo derisa a mio piacimento, E lei in termini miti mi implorava di aver clemenza, Allora le ho chiesto in cambio il suo bambino changeling, Che mi ha dato immediatamente, ed ha ordinato alla sua fata di portarlo al mio pergolato nel Regno delle Fate.

E adesso che ho il fanciullo, toglierò questa odiosa imperfezione dai suoi occhi. E tu, bravo Puck, togli questo scalpo transformato Dalla testa di questo bifolco Ateniese, Così che, al suo risveglio insieme agli altri, Se ne possano tutti ritornare ad Atene, E non pensare mai più agli incidenti di questa notte, Se non come una forte agitazione lasciata da un sogno. Ma prima libererò la Regina delle Fate. [Spremendo un’erba negli occhi di Titania.]

Torna ad essere com’eri prima, A vedere come vedevi prima.

Il bocciolo di Diana sul fiore di Cupido Prevalga con con forza e poteri sacri. Adesso, mia Titania, svegliati, mia dolce Regina!

T1TANIA [Starting up.]

My Oberon, what visions have I seen ! Methought I was enamoured of an ass.

OBERON There lies your love.

TITANIA How came these things to pass? O, how mine eyes do loathe his visage now!

OBERON Silence awhile: Robin, take off this head. Titania, music call, and strike more dead Than common sleep of all these five the sense.

TITANIA Music, ho, music such as charmeth sleep!

[Soft music plays.]

PUCK [To Bottom, removing the ass's head]

Now when thou wak'st, with thine own fool’s eyes peep.

OBERON Sound, music! Come, my Queen, take hands with me, And rock the ground whereon these sleepers be.

[They dance.]

Now thou and I are new in amity, And will tomorrow midnight solemnly Dance in Duke Theseus' house triumphantly, And bless it to all fair prosperity. There shall the pairs of faithful lovers be Wedded, with Theseus, all in jollity.

PUCK Fairy King, attend, and mark: I do hear the morning lark.

OBERON Then, my Queen, in silence sad, Trip we after night's shade; We the globe can compass soon, Swifter than the wandering moon.

TITANIA Come, my lord, and in our flight Tell me how it came this night That I sleeping here was found With these mortals on the ground.

Exeunt Oberon, Titania and Puck

TITANIA [Alzandosi.]

Mio Oberon, che strano sogno ho fatto! Credevo di essere innamorata di un asino.

OBERON Qui giace il tuo amore.

TITANIA Come sono potute accadere queste cose? Oh, quanto disprezzano i miei occhi il suo viso, adesso!

OBERON Un attimo di silenzio: Robin, togligli questa testa. Titania, invoca la musica, e colpisci, più letale Del sonno, i sensi di questi cinque.

TITANIA: Musica, oh, musica tale da incantare il sonno! [Suona una musica soffusa.]

PUCK [A Bottom, rimuovendo la testa d’asino.] Adesso, quando ti alzerai, tornerai a vedere con i tuoi occhi da sciocco.

OBERON Suono, musica! Avanti, mia Regina, prendimi per mano, E scuoti la terra dove giacciono costoro addormentati. [Danzano.]

Adesso tu ed io ci siamo riappacificati, E domani a mezzanotte, solennemente, Danzeremo nella dimora del Duca Teseo trionfanti, E la benediremo propiziando ogni prosperità. Lì le coppie di innamorati fedeli Si sposeranno, con Teseo, tutti in allegria.

PUCK Re delle Fate, ascolta, e nota: Io già odo l’allodola del mattino.

OBERON Dunque, mia Regina, in triste silenzio, Ritiriamoci seguendo l’ombra della notte; Possiamo presto fare il giro del mondo, Più veloci della luna errante.

TITANIA Vieni, mio signore, e durante il tragitto, Narrami come è accaduto che io stanotte Mi ritrovassi a dormire qui Per terra con questi mortali. Escono Oberon, Titania e Puck

Iść przez sen ku tobie, w twe słodkie ręce obie… przez pola długie ogromnie, sadzone w rzędy doniczek… samych niebieskich konwalii i szafirowych goryczek… …przejść przez jezioro nieduże, zrobione z drewnianej balii… i trochę nieprzytomnie iść dalej przez bór ciemny, w którym kwitną róże, lecz w którym nie pali się ani jedna świeca… gdzie straszy stary niedźwiedź dziecinny zza pieca, dziś przerobiony na kota… I widzieć w oddali już twoją psią budę z kryształy, blachy i złota… przedrzeć się z trudem poprzez dziwną grudę… i jeszcze ten rów przebyć… – potknąć się – i już nie być.

To walk through a dream towards you, into your sweet embrace… through fields stretching so long, Planted in rows of pots… Of blue snowdrops only and sapphire gentians… …to cross a small lake, made from a wooden bath… and somewhat unwittingly walk further through a dark forest, abound with blooming roses, but with no lit candle… where haunts the old childish bear from behind the hearth, turned today into a cat…

And to see in the distance your shed of crystal, tin, and gold… break through a strange clod with difficulty… and cross this ditch… – stumble – and no longer be.

Der Traum, aus dem Theaterstück Draußen vor der Tür

(In der Elbe. Eintöniges Klatschen kleiner Wellen. Die Elbe. Beckmann.)

BECKMANN: Wo bin ich? Mein Gott, wo bin ich denn hier?

ELBE: Bei mir.

BECKMANN: Bei dir? Und – wer – bist du?

ELBE: Wer soll ich denn sein, du Küken, wenn du in St. Pauli von den Landungsbrücken ins Wasser springst?

BECKMANN: Die Elbe?

ELBE: Ja, die. Die Elbe.

BECKMANN (staunt): Du bist die Elbe!

ELBE: Ah, reißt du deine Kinderaugen auf, wie? Du hast wohl gedacht, ich wäre ein romantisches junges Mädchen mit blaßgrünem Teint?

Typ Ophelia mit Wasserrosen im aufgelösten Haar? Du hast am Ende gedacht, du könntest in meinen süßduftenden Lilienarmen die Ewigkeit verbringen. Nee, mein Sohn, das war ein Irrtum von dir. Ich bin weder romantisch noch süßduftend. Ein anständiger Fluß stinkt. Jawohl. Nach Öl und Fisch. Was willst du hier?

BECKMANN: Pennen. Da oben halte ich das nicht mehr aus. Das mache ich nicht mehr mit. Pennen will ich. Tot sein. Mein ganzes Leben lang tot sein. Und pennen. Endlich in Ruhe pennen. Zehntausend Nächte pennen.

ELBE: Du willst auskneifen, du Grünschnabel, was? Du glaubst, du kannst das nicht mehr aushalten? Hm? Da oben, wie? Du bildest dir ein, du hast schon genug mitgemacht, du kleiner Stift. Wie alt bist du denn, du verzagter Anfänger?

BECKMANN: Fünfundzwanzig. Und jetzt will ich pennen.

ELBE: Sieh mal, fünfundzwanzig. Und den Rest verpennen. Fünfundzwanzig und bei Nacht und Nebel ins Wasser steigen, weil man nicht mehr kann. Was kannst du denn nicht mehr, du Greis?

An Bhrionglóid, ón dráma Taobh amuigh os comhair an dorais (San Eilbe. Monabhar monatónach na dtonnta beaga. An Eilbe. Beckmann.)

BECKMANN: Cá bhfuil mé? A Dhia, cá bhfuil mé anseo?

EILBE: Liomsa.

BECKMANN: Leatsa? Agus- cé thú féin?

EILBE: Cé ar chóir go mbeinn, a scalltáin, má léimeann tú isteach san uisce ón Droichead Tuirlingthe ag St. Pauli?

BECKMANN: An Eilbe?

EILBE: Í féin. An Eilbe.

BECKMANN (iontas air): Is tusa an Eilbe!

EILBE: Á, stróicfidh tú na súile linbh sin díot, an ea? Shíl tú gur cailín óg rómánsúil a mbeadh ionam, le himir bhánghlas? Cineál Ophelia le duilleoga báite i mo ghruaig scaoilte? Shamhlaigh tú ar dheireadh ina d’fhéadfá fanacht i mo lámha lile cumhra go deo na ndeor? Seans ar bith, a mhic, do bhotún a bhí ann ansin. Nílim rómánsúil ná cumhra. Bíonn boladh bréan ó abhann chreidiúnach. Sin mar a bhíonn. Boladh ola agus éisc. Cad atá uait anseo?

BECKMANN: Codladh. Ní féidir liom é a sheasamh thuas ansin a thuilleadh. Níl tuilleadh bainteach leis uaim. Codladh atá uaim. A bheith marbh atá uaim. A bheith marbh go ceann mo shaoil. Agus codladh. Codladh i gciúnas ar dheireadh. Codladh deich míle oíche.

EILBE: Is mian leat bailiú leat, a ghlasaigh, an ea? Síleann tú nach féidir leat é a sheasamh a thuilleadh, hm? Thuas ansin, an ea? Tá tú leitheadach go leor le ceapadh, tá go leor déanta agat cheana féin, a núíosach beag. Cén aois thú ansin, a thosaitheor bheagmhisniúil?

BECKMANN: Cúig bliana is fiche. Agus anois is mian liom codladh.

EILBE: Féach anois, cúig bliana is fiche. Agus codladh go ceann na coda eile. Cúig bliana is fiche agus dreapadh san oíche agus sa cheo isteach san uisce, mar nach féidir é a sheasamh a thuilleadh. Cad nach féidir leat a sheasamh a thuilleadh, a dhoineantaigh?

BECKMANN: Alles, alles kann ich nicht mehr da oben. Ich kann nicht mehr hungern. Ich kann nicht mehr humpeln und vor meinem Bett stehen und wieder aus dem Haus raushumpeln, weil das Bett besetzt ist. Das Bein, das Bett, das Brot – ich kann das nicht mehr, verstehst du!

ELBE: Nein. Du Rotznase von einem Selbstmörder. Nein, hörst du! Glaubst du etwa, weil deine Frau nicht mehr mit dir spielen will, weil du hinken mußt und weil dein Bauch knurrt, deswegen kannst du hier bei mir untern Rock kriechen? Einfach so ins Wasser jumpen? Du, wenn alle, die Hunger haben, sich ersaufen wollten, dann würde die gute alte Erde kahl wie die Glatze eines Möbelpackers werden, kahl und blank. Nee, gibt es nicht, mein Junge. Bei mir kommst du mit solchen Ausflüchten nicht durch. Bei mir wirst du abgemeldet. Die Hosen sollte man dir stramm ziehen, Kleiner, jawohl! Auch wenn du sechs Jahre Soldat warst. Alle waren das. Und die hinken alle irgendwo. Such dir ein anderes Bett, wenn deins besetzt ist. Ich will dein armseliges bißchen Leben nicht. Du bist mir zu wenig, mein Junge. Laß dir das von einer alten Frau sagen: Lebe erstmal. Laß dich treten. Tritt wieder! Wenn du den Kanal voll hast, hier, bis oben, wenn du lahm getrampelt bist und wenn dein Herz auf allen Vieren angekrochen kommt, dann können wir mal wieder über die Sache reden. Aber jetzt machst du keinen Unsinn, klar? Jetzt verschwindest du hier, mein Goldjunge. Deine kleine Handvoll Leben ist mir verdammt zu wenig. Behalte sie. Ich will sie nicht, du gerade eben Angefangener. Halt den Mund, mein kleiner Menschensohn. Ich will dir was sagen, ganz leise, ins Ohr, du, komm her: ich scheiß auf deinen Selbstmord! Du Säugling! Paß gut auf, was ich mit dir mache. (Laut.) Hallo, Jungens! Werft diesen Kleinen hier bei Blankenese wieder auf den Sand! Er will es noch mal versuchen, hat er mir eben versprochen. Aber sachte, er sagt, er hat ein schlimmes Bein, der Lausebengel, der grüne!

BECKMANN: Gach rud. Ní féidir liom aon rud a sheasamh thuas ansin a thuilleadh. Ní féidir liom a bheith ocrasach a thuilleadh. Ní féidir liom a bheith ag stabhaíl a thuilleadh, agus seasamh os comhair mo leapa agus stabhaíl amach as an teach arís toisc mo leaba a bheith lán. An chos, an leaba, an t-arán- ní féidir liom é a sheasamh a thuilleadh, an dtuigeann tú!

EILBE: Ní thuigim. A fhéinmharfóir smaoisigh. Ní thuigim, an gcloiseann tú! An síleann tú, toisc nach bhfuil do bhean ag iarraidh spraoi leat a thuilleadh, toisc gur ghá duit bacadaíl agus toisc go mbíonn do bholg ag canrán, mar sin is féidir leat téaltú faoi charraig? Léim isteach san uisce mar sin? Tusa, dá mbeadh gach duine atá ocras orthu ag iarraidh iad féin a bhá, bheadh an seandomhan maith maol ar nós cheann sheachadóir troscáin, maol agus lom. Ní mar sin atá, a mhic. Liomsa, ní éireoidh leat leis an teitheadh sin. Liomsa, tugfar bata agus bóthar duit. Muise, bachóir na an bríste a theannadh ort, a bheagadáin. Fiú má raibh tú i do shaighdiúir ar feadh sé bliana. Mar Sin a bhí gach duine. Agus tá siad go léir ag stabhaíl áit éigint. Faigh leaba eile duit féin, má tá do cheann féin líonta. Níl do phíosa suarach beatha uaim. Ní leor thú dom, a bhuachaill. Lig do sheanbhean é seo a rá leat: Mair ar dtús. Siúil amach. Siúil arís! Nuair atá an píopa lán agat, anseo, suas go dtí an barr, nuair atá tú bacach leis na troitheáin a oibriú agus nuair a bhíonn do chroí ag imeacht ar na ceithre boinn, ansin is féidir linn an cheist a phlé arís. Ach anois, cuir deireadh leis an raiméis, maith go leor? Anois imíonn tú as mo radharc, mo bhuachaillín órga. Ní leor do ghreim bheag beatha dom. Beir greim air. Níl sé uaim, a núíosaigh úir. Éist do bhéal, a mhic máthar! Is mian liom a rá leat, séimh, i do chluas, tusa, tar anseo: Déanaim cac ar do fhéinmharú! A shiolpaire. Tabhair aire, cad a dhéanaim leat. (ós ard) A bhuachaillí! Caith an beagadán seo suas ar an ngaineamh in Blankenese! Bainfidh sé triail as arís, gheall sé dom. Ach séimh anois, deir sé go bhfuil cos dhona aige, an caolan míolach, an glasach!

Tengo miedo. La tarde es gris y la tristeza del cielo se abre como una boca de muerto. Tiene mi corazón un llanto de princesa olvidada en el fondo de un palacio desierto.

Tengo miedo -Y me siento tan cansado y pequeño que reflejo la tarde sin meditar en ella. (En mi cabeza enferma no ha de caber un sueño así como en el cielo no ha cabido una estrella.)

Sin embargo en mis ojos una pregunta existe y hay un grito en mi boca que mi boca no grita. ¡No hay oído en la tierra que oiga mi queja triste abandonada en medio de la tierra infinita!

Se muere el universo de una calma agonía sin la fiesta del Sol o el crepúsculo verde. Agoniza Saturno como una pena mía, la Tierra es una fruta negra que el cielo muerde.

Y por la vastedad del vacío van ciegas las nubes de la tarde, como barcas perdidas que escondieran estrellas rotas en sus bodegas. Y la muerte del mundo cae sobre mi vida.

I’m scared. The evening is grey and the sadness Of the sky opens itself like the mouth of a corpse. My heart contains the cry of a princess Forgotten at the bottom of a deserted palace.

I’m scared — And I feel so tired and so small That I reflect on the evening without meditating on her. (In my sick head there must not be room for a dream Just as in the sky there was not room for a star.)

Even so in my eyes a question exists And there is a shout in my mouth that my mouth does not shout. There is no ear on all the earth that hears my sad complaint Abandoned in the middle of the infinite earth!

The universe dies of a calm agony Without the Festival of the Sun or the green twilight. Saturn agonizes like a sorrow of mine, The Earth is a black fruit that the sky bites.

And through the vastness of the void go blindly The evening clouds, like lost boats That hide broken stars in their holds.

And the death of the world falls upon my life.

I go into the high-ceilinged stacks and wander among the shelves, searching for a book that looks interesting. Magnificent thick beams run across the ceiling of the room, and soft early-summer sunlight is shining through the open window, the chatter of birds in the garden filtering in. The books on the shelves in front of me, sure enough, are just as Oshima said, mainly books of Japanese poetry. Tanka and haiku, essays on poetry, biographies of various poets. There are also a lot of books on local history. A shelf further back contains general humanities – collections of Japanese literature, world literature and individual writers, classics, philosophy, drama, art history, sociology, history, biography, geography ... When I open them, most of the books have the smell of an earlier time leaking out from between their pages – a special odour of the knowledge and emotions that for ages have been calmly resting between the covers. Breathing it in, I glance through a few pages before returning each book to its shelf.

Finally, I decide on a multi-volume set, with beautiful covers, of the Burton translation of The Arabian Nights, pick out one volume and take it back to the reading room. I've been meaning to read this book. Since the library has just opened for the day, there's no one else there and I have the elegant reading room all to myself. It's exactly like in the photo in the magazine – roomy and comfortable, with a high ceiling. Every once in a while a gentle breeze blows in through the open window, the white curtain rustling softly in air that has a hint of the sea. And I love the comfortable sofa. An old upright piano stands in a corner, and the whole place makes me feel as though I'm in some friend's house.

As I relax on the sofa and gaze around the room a thought hits me: this is exactly the place I've been looking for all my life. A little hideaway in some sinkhole somewhere. I'd always thought of it as a secret, imaginary place, and can barely believe that it actually exists. I close my eyes and take a breath, and the wonder of it all settles over me like a gentle cloud. Slowly I stroke the creamish cover of the sofa, then stand up and walk over to the piano and lift the lid, laying all ten fingers on the faintly yellowing keys. I close the lid and cross the faded grape-patterned carpet to the window and test the antique handle that opens and closes it. I switch the floor lamp on and off, then check out all the paintings hanging on the walls. Finally, I flop back down on the sofa and pick up where I left off, concentrating on The Arabian Nights for a while.

Me meto en una sección de estanterías que llegan hasta el techo y deambulo entre ellas, buscando un libro que tenga una pinta interesante. Unas gruesas vigas impresionantes cruzan el techo de la habitación, y la luz suave de principios de verano brilla a través de la ventana abierta, por la cual se oye el canto de los pájaros. Los libros en las estanterías enfrente de mí son, como dijo Oshima, principalmente libros de poesía japonesa.Tanka y haiku, ensayos sobre la poesía, las biografías de varios poetas. Hay también muchos libros de historia local. Una estantería más atrás contiene las humanidades generales – colecciones de literatura japonesa, literatura mundial y escritores individuales, clásicos, filosofía, teatro, historia del arte, sociología, historia, biografía, geografía … Cuando los abro, la mayoría de los libros tienen el olor de una época pasada que se escapa de entre sus páginas – una fragancia especial de conocimiento y emoción que durante años había descansado tranquilamente entre las portadas. Respirándolo, ojeo unas cuantas páginas antes de devolver cada libro a su estantería. Por fin, me decido en un conjunto de varios volúmenes, con hermosas portadas, de la traducción de Burton de Las mil y una noches, elijo un volumen y me lo llevo a la sala de lectura. Hace tiempo que quiero leerlo. Como es justo después de la hora de abrir, la biblioteca está vacía y tengo la elegante sala de lectura para mí solo. Es exactamente como la foto de la revista – amplia y cómoda, con un techo alto. De vez en cuando una brisa ligera sopla por la ventana abierta, la cortina blanca susurrando suavemente en el aire que huele vagamente al mar. Y adoro el sofá cómodo. Hay un viejo piano vertical en la esquina de la sala, y todo el lugar me hace sentir como si estuviera en la casa de algún amigo.

Mientras me relajo en el sofá y mi mirada vaga por la habitación, me viene un pensamiento a la cabeza: este es exactamente el lugar que he estado deseando encontrar toda la vida. Un escondite en algún socavón. Siempre había pensado que sería un lugar secreto, fantástico, y apenas puedo creer que realmente exista. Cierro los ojos y tomo un respiro, y la maravilla de todo esto se asienta sobre mi como una suave nube. Lentamente, acaricio la cubierta cremosa del sofá, y me levanto para acercarme al piano y levantar la tapa, colocando los diez dedos en las teclas ligeramente amarillentas. Cierro la tapa y cruzo la alfombra descolorida con dibujos de uvas a la ventana y pruebo la antigua manilla que la abre y la cierra. Enciendo y apago la lámpara de pie, y entonces me fijo en todas las pinturas colgadas en las paredes. Finalmente, me tiro en el sofá y sigo de donde había dejado, concentrándome en Las mil y una noches por un rato.

Când te oprești în fața oglinzilor o mână iese din apele clare ca să te mângâie o mâna care este totdeauna a ta această mână de mătrăgună și de hârtie care-mi amintește dezastruoasele și amplele întâlniri în fața oglinzilor

Și de data aceasta umerii mei nu mai au umbră nu mai sunt decât picioarele mele care aleargă aceste triste biciclete aceste butoaie încărcate cu pălării

Vom trece strada fără a vedea ce se întâmplă în pachetul acesta sunt pantofii uzați ai cenușăresei dar nu ne privește deloc în camera aceea goală răsună poate armonica morții ceea ce văd e un fluture călcat de tren ceea ce ating e sângele tău ca un arbore ceea ce aud e părul tău ca o scoică

Iată dezgustătoarele smintiri corpul meu împărțit în două jumătatea mea roșie jumătatea mea albastră linia precisă care mă împarte pe care ai construit-o mușcându-mi palmele iată jumătatea mea calmă jumătatea mea dezesperată

Îți vor trebui ace mai tari ca să le coși împreună sfori mai elastice degete mai abile va trebui să distrug singur ceea ce am iubit împreună și mai ales va trebui să te miști liberă când voi traversa orașul acesta pustiu în frumosul meu costum de scafandru

When you stop before the mirrors a hand reaches out of clear waters to caress you a hand that is always yours this hand of mandrake and paper which reminds me of our long and ruinous trysts before mirrors.

And this time my shoulders cast no shadow it’s just my legs that keep running these sad bicycles these barrels jammed with hats

We shall cross the street without looking to see what’s happening inside this package are cinderella’s worn out shoes but that does not concern us inside this empty room death’s harmonica may be echoing what I see is a butterfly crushed by a train what I touch is your blood like a tree what I hear is your hair like a clamshell

Witness these repulsive aberrations my body split in half my red half my blue half the clear you drew biting at the palms of my hands witness my serene half my desperate half

You will need thicker needles to sew them back together more flexible strings more agile fingers I alone must destroy that which we loved together and above all you must move lavishly when I cross this empty town in my splendid diving suit

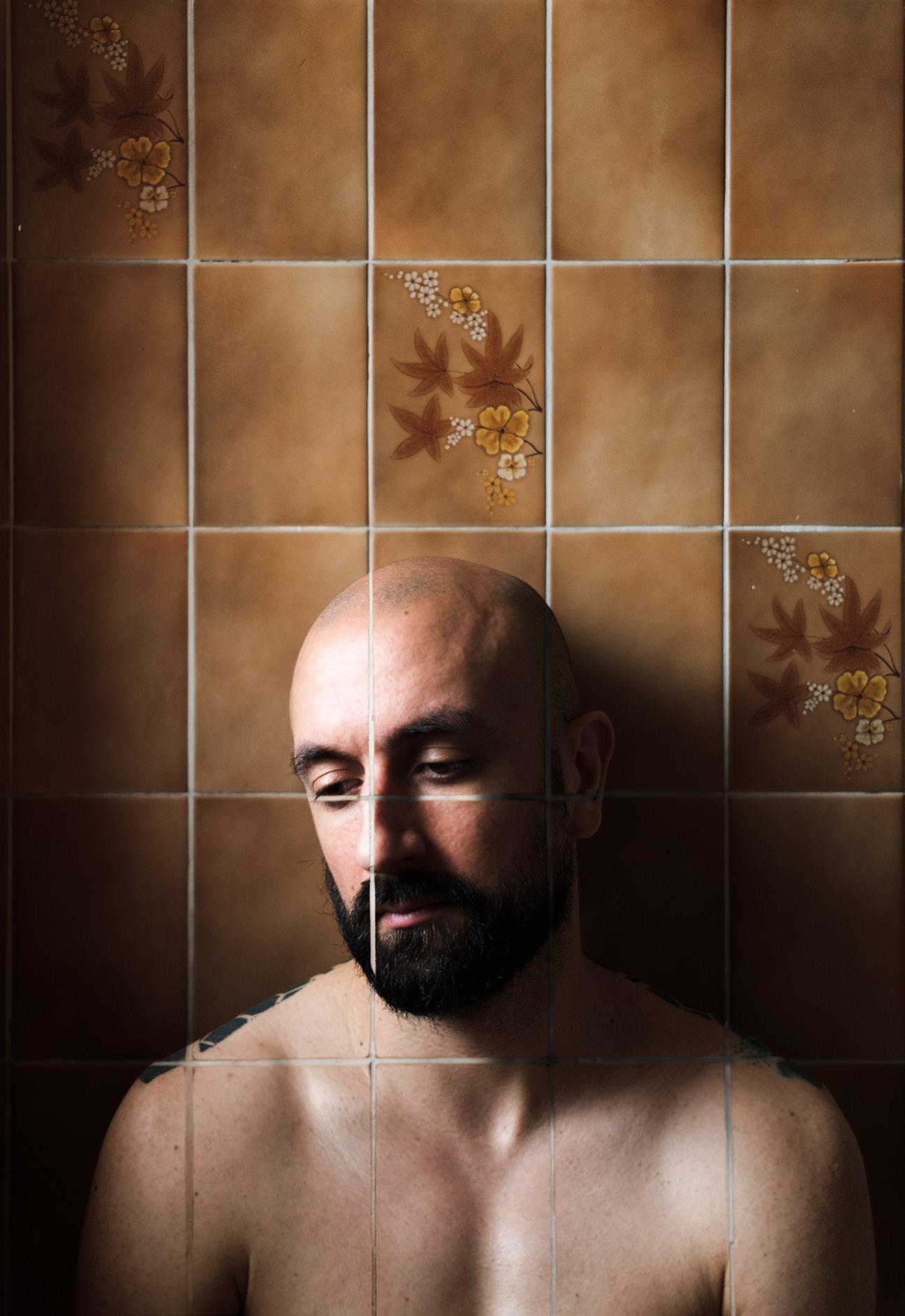

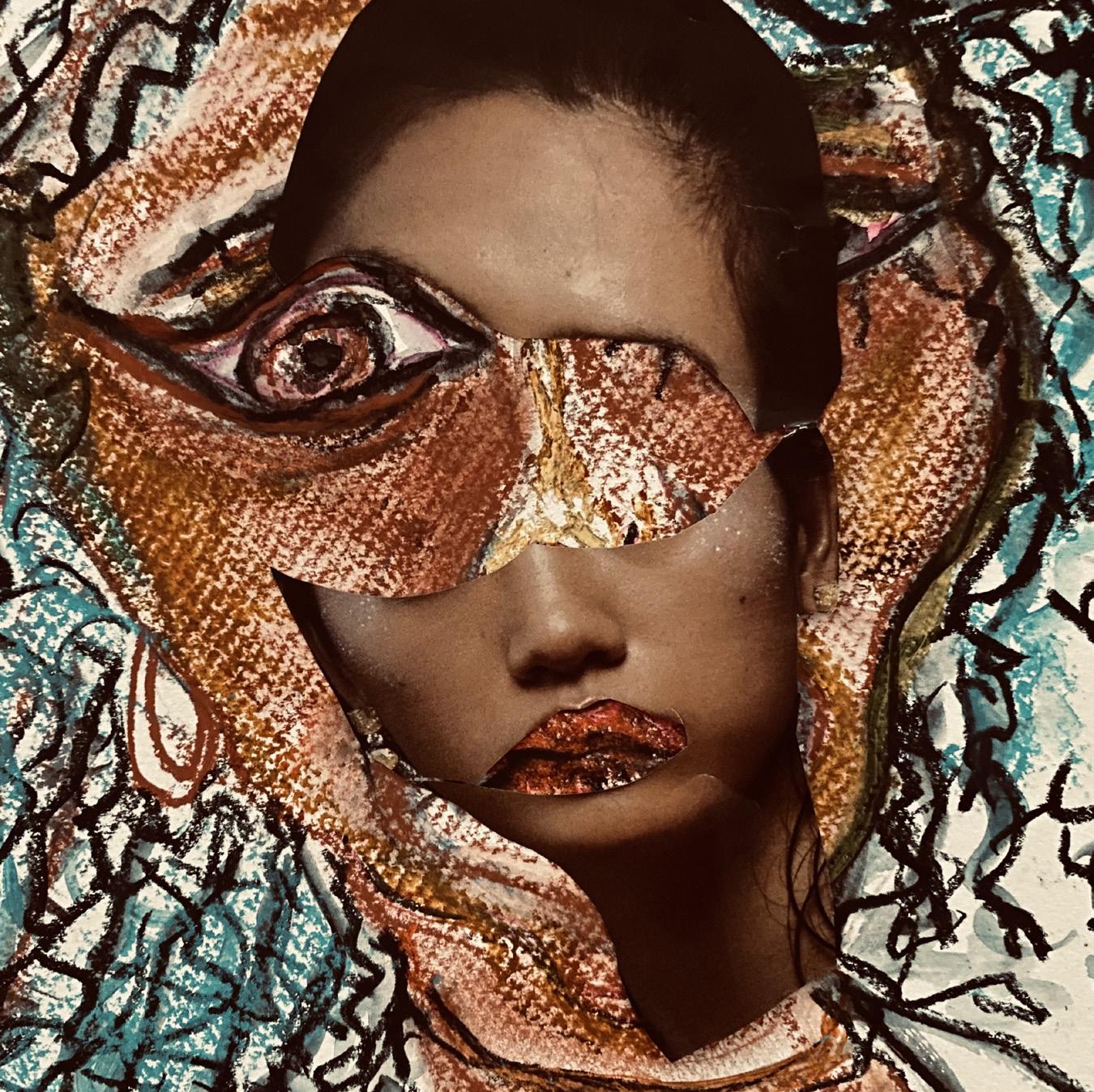

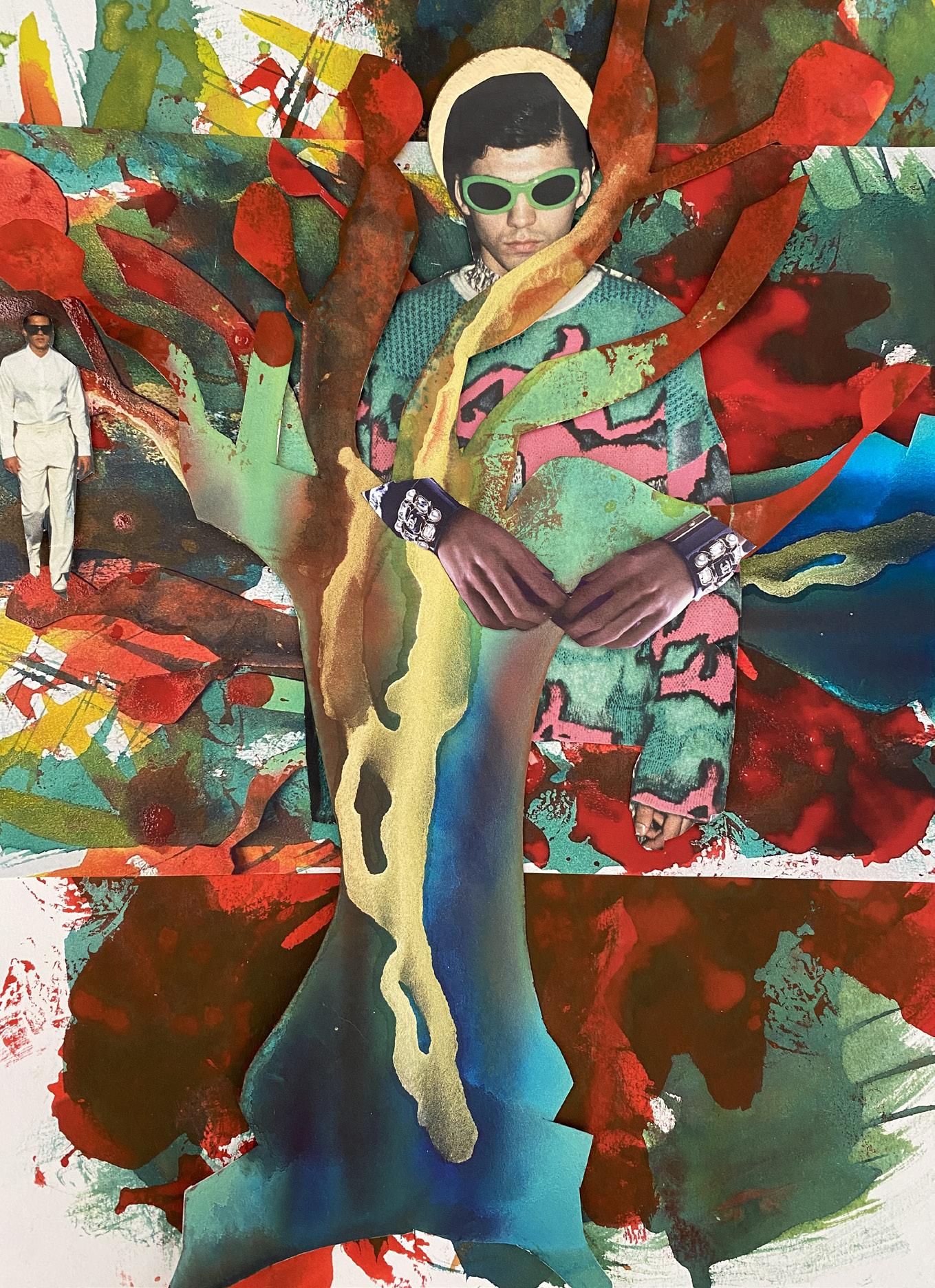

Mauricio Quevedo - Self Portrait

Mauricio Quevedo - Self Portrait

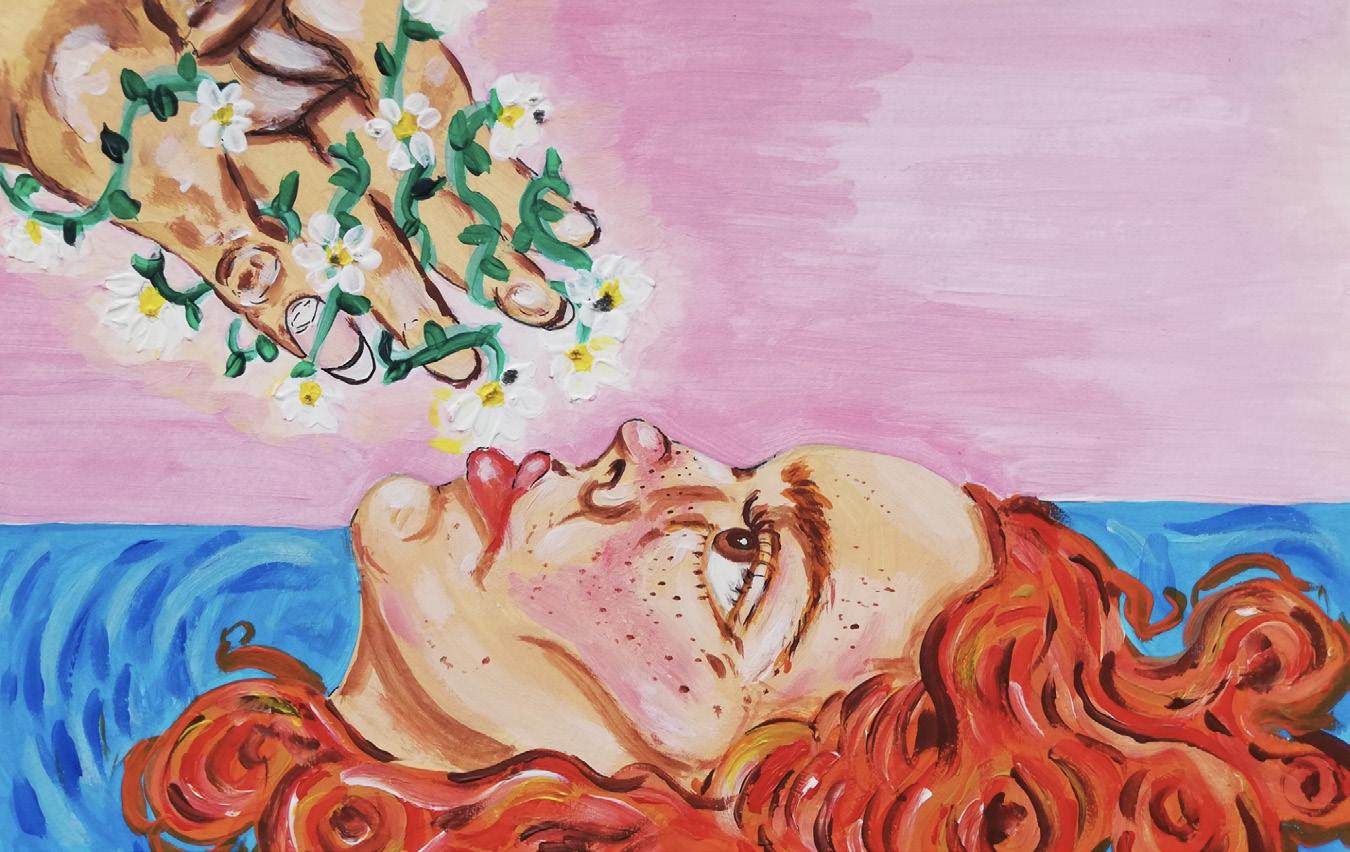

Ella

Ella

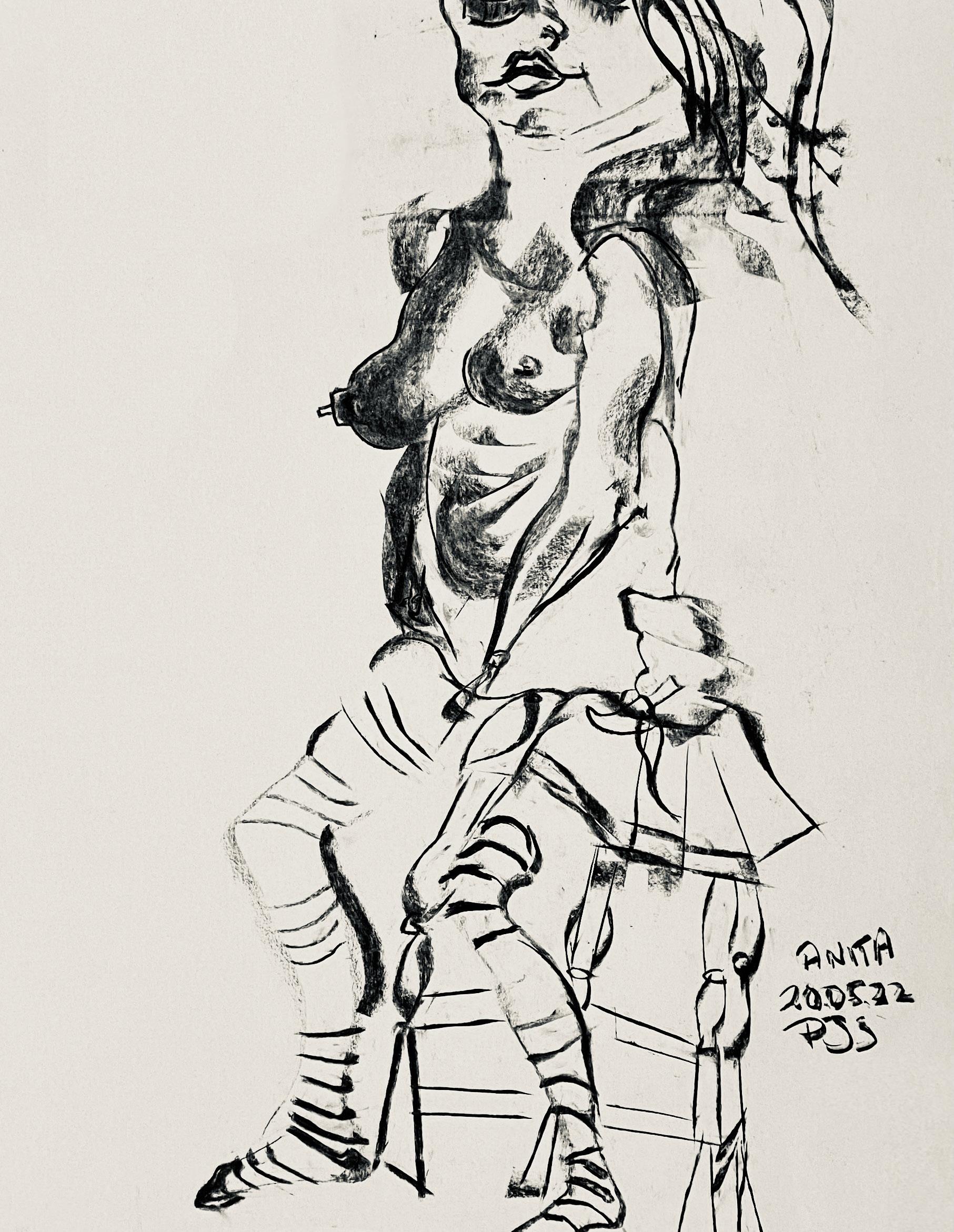

Penny Stuart - I like my crisps plain (Series 5)

Penny Stuart - I like my crisps plain (Series 5)

Penny Stuart - I like my crisps plain (Series 12)

Penny Stuart - I like my crisps plain (Series 12)

Penny Stuart - Michael is sitting on a stool on the top floor of a big Georgian house on Parnell Square

Penny Stuart - Michael is sitting on a stool on the top floor of a big Georgian house on Parnell Square

Thelma Ackermann - To have a panic attack in front of the rising sun

Thelma Ackermann - To have a panic attack in front of the rising sun

Thelma Ackermann - Extrascenceur

Thelma Ackermann - Extrascenceur

Thelma Ackermann - The one who leaves and the one who stays

Sonhei que estava chovendo, bem no meio do meu sonho.

Pingos caíam sem parar frios, gelados, molhados, molhando meus pensamentos encharcando minha vida como lágrimas do mar.

Sonhei que estava chovendo e eu não tinha guarda-chuva! Tanta água a me cercar lagos mares oceanos, carregando-me nas ondas feito surfista sem prancha e que não sabe nadar.

Sonhei que estava sonhando com uma chuva tão forte, que comecei a chorar gotas, água, tempestade, escorrendo no meu rosto até a tristeza ir passando até eu parar de sonhar.

Sonhei que a chuva caía borrasca tempestuosa, e acordei com a melodia da noite silenciosa…

I dreamed: it was raining Raining inside my dream. Drops would fall non stop Icy, Cold, Soaked Watering my thoughts Drowning my life Like teardrops the sea couldn’t hold

I dreamed: it was raining And I didn't have a raincoat! All that water around me lakes seas oceans I was being carried by the waves A surfer without a board A sailor without a boat

I dreamed: I was dreaming About a rain so strong That it made me cry Drops Water Storm Running down my face Carrying the sadness along Carrying this dream away

I dreamed: the rain was falling A stormy wind Woke me up I can hear the music That the silent night sings…

I will encounter darkness as a bride And hug it in mine arms.

All distance emptied, the world reduced to an arm’s length. The closeness of the night is absolute: nothing to steady an eye on, nowhere to rest a thought. My life is narrowed to the ground beneath my feet. There is a guilt to it, a clandestine hush to the fumbling of breath. Whole fields have surrendered – the night lifts its hood over them, calms them, sings a hymn of warm silence to lull the grass to sleep. A small wind brushes past my leg, somewhere a bird settles in a hedgerow or rests its full breast in the stubble of the corn. The dark wants my life for itself. It raises its lips to mine, its breath is in my breath, and I think its face pauses before mine. Imagine its contours –the deeper pools of blackness – its full embrace. My limbs are buoyed helplessly by it, and I float. I almost speak, but it stops me, lifts a finger to the empty word of my mouth, and leans in.

Andrò incontro all’oscurità come a una sposa e la terrò tra le mie braccia.

Vuota ogni distanza, il mondo ridotto alla lunghezza di un braccio. La presenza della notte è assoluta: niente su cui fissare lo sguardo o posare i pensieri. La vita si riduce alla terra sotto i miei piedi. C’è un senso di colpa, una quiete nascosta dietro questo respiro impacciato. Interi campi si sono arresi – la notte stende il suo manto su di loro, li calma, canta un inno di tepore e silenzio per cullare l’erba al sonno. Un vento lieve mi accarezza la gamba, da qualche parte un uccello si sistema in una siepe o riposa il petto gonfio tra le stoppie. Il buio vuole la mia vita per sé. Porta le labbra alle mie, il suo fiato nel mio fiato, e sento il suo viso fermarsi davanti al mio. Ne immagino i contorni, le curve scure, il suo abbraccio pieno. Il mio corpo inerme è alla deriva, fluttua. Sto per parlare, ma mi blocca, porta un dito alla parola vuota nella mia bocca, e si appoggia a me.

Tomorrow when the farm boys find this freak of nature, they will wrap his body in newspaper and carry him to the museum.

But tonight he is alive and in the north field with his mother. It is a perfect summer evening: the moon rising over the orchard, the wind in the grass. And as he stares into the sky, there are twice as many stars as usual.

Amárach, nuair a thiocfaidh na gasúir ar an lao ar leith seo, clúdóidh siad a chorp le páipéar nuachta agus iompróidh siad é go dtí an músaem.

Ach anocht tá sé beo sa gharraí thuaidh lena mháthair.

Is tráthnóna foirfe samhraidh é: an ghealach ag éirí thar an úllord an ghaoth san fhéar.

Agus é ag stánadh ar an spéir tá dhá oiread (níos mó) réaltaí ná mar is gnách

Op school stonden ze op het bord geschreven. Het werkwoord hebben en het werkwoord zijn; hiermee was tijd, was eeuwigheid gegeven. De ene werkelijkheid, de andre schijn.

Hebben is niets. Is oorlog. Is niet leven. Is van van de wereld en haar goden zijn. Zijn is, boven die dingen uitgeheven. Vervuld worden van goddelijke pijn.

Hebben is hard. Is lichaam. Is twee borsten.

Is naar de aarde hongeren en dorsten. Is enkel zinnen, enkel botte plicht.

Zijn is de ziel, is luisteren, is wijken. Is kind worden en naar de sterren kijken. En daarheen langzaam worden opgelicht.

At school they were on the board: the verb to have and the verb to be. They brought us time here, eternity. One was appearance, the other real life.

Having is nothing. It’s war. Not living. It’s caught by the world and her gods. Being is lifted above those things, getting fulfilled with a godly ache.

To have is heavy. It’s flesh. The chest. It’s craving and thirsting for the earth. It’s merely phrases, just plain duty.

To be is the soul, it’s listening, giving way, to watch the stars and become child and slowly rise towards them, growing lighter.

OPENER (dry as dust): It is the month of May . . . for me. Pause. Yes, that’s right. Pause. I open.

VOICE (low, panting): —story . . . if you could finish it . . . you could rest . . . you could sleep . . . not before . . . oh I know . . . the ones I’ve finished . . . thousands and one . . . all I ever did . . . in my life . . . with my life . . . saying to myself . . . finish this one . . . it’s the right one . . . then rest . . . then sleep . . . no more stories . . . no more words . . . and finished it . . . and not the right one . . . couldn’t rest . . . straight away another . . . to begin . . . to finish . . . saying to myself . . . finish this one . . . then rest . . . this time it's the right one . . . this time you have it . . . and finished it . . . and not the right one . . . couldn’t rest . . . straight away another . . . but this one . . . it’s different . . . I’ll finish it . . . then rest . . . it’s the right one . . . this time I have it . . . I’ve got it . . . Woburn . . . I resume . . . a long life . . . already . . . say what you like . . . a few misfortunes . . . that’s enough . . . five years later . . . ten years . . . I don’t know . . . Woburn . . . he’s changed . . . not enough . . . recognizable . . . in the shed . . . yet another . . . waiting for night . . . night to fall . . . to go out . . . go on . . . elsewhere . . . sleep elsewhere . . . it’s slow . . . he lifts his head . . . now and then . . . his eyes . . . to the window . . . it’s darkening . . . the earth is darkening . . . it’s night . . . he gets up . . . knees first . . . then up . . . on his feet . . . slips out . . . Woburn . . . same old coat . . . right the sea . . . left the hills . . . he has the choice . . . he has only—

OPENER (with VOICE): And I close.

Silence. I open the other. MUSIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

OPENER (with MUSIC): And I close.

Silence. I open both.

VOICE/MUSIC (together):—on . . . it’s getting on . . . finish it . . . don’t give up . . . then rest . . . sleep . . . not before . . . finish it . . . it's the right one . . . this time you have it . . . you’ve got it . . . it’s there . . . somewhere . . . you’ve got him . . . follow him . . . don't lose him . . . Woburn story . . . getting on . . . finish it . . . then sleep . . . no more stories . . . no more words . . . come on . . . next thing . . . he—

OPENER (with VOICE and MUSIC): And I close. Silence. I start again.

VOICE: —down . . . gentle slope . . . boreen . . . giant aspens . . . wind in the boughs . . . faint sea . . . Woburn . . . same old coat . . . he goes on . . . stops . . . not a soul . . . not yet ... night too bright . . . say what you like . . . the bank . . . he hugs the bank . . . same old stick . . . he goes down . . . falls . . . on purpose or not . . . can’t see . . . he’s down . . . that’s what counts . . . face in the mud . . . arms spread . . . that’s the idea . . . al ready . . . we’re there already . . . no not yet . . . he gets up . . . knees first . . . hands flat . . . in the mud . . . head sunk . . . then up . . . on his feet . . . huge bulk . . . come on . . . he goes on . . . he goes down . . . come on . . . in his head . . . what's in his head . . . a hole . . . a shelter . . . a hollow . . . in the dunes . . . a cave . . . vague memory . . . in his head . . . of a cave . . . he goes down . . . no more trees . . . no more bank . . . he’s changed . . . not enough . . . night too bright . . . soon the dunes . . . no more cover . . . he stops . . . not a soul . . . not—

Silence. MUSIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Silence.

VOICE/MUSIC (together): —rest . . . sleep . . . no more stories . . . no more don't give up . . . it’s the right one . . . we’re there . . . nearly . . . I’m there . . . somewhere . . . Woburn . . . I’ve got him . . . don’t lose him . . . follow him . . . to the end . . . come on . . . this time . . . it's the right one . . . finish . . . sleep . . . Woburn . . . come on—

Silence.

Mirar el río hecho de tiempo y agua Y recordar que el tiempo es otro río, Saber que nos perdemos como el río Y que los rostros pasan como el agua.

Sentir que la vigilia es otro sueño Que sueña no soñar y que la muerte Que teme nuestra carne es esa muerte De cada noche que se llama sueño.

Ver en el día o en el año un símbolo De los días del hombre y de sus años, Convertir el ultraje de los años En una música, un rumor y un símbolo,

Ver en la muerte el sueño, en el ocaso Un triste oro, tal es la poesía Que es inmortal y pobre. La poesía Vuelve como la aurora y el ocaso.

A veces en las tardes una cara Nos mira desde el fondo de un espejo; El arte debe ser como ese espejo Que nos revela nuestra propia cara.

Cuentan que Ulises, harto de prodigios, Lloró de amor al divisar a su Ítaca Verde y humilde. El arte es esa Ítaca De verde eternidad, no de prodigios.

También es como el río interminable Que pasa y queda y es cristal de uno mismo Heráclito inconstante, que es el mismo Y es otro, como el río interminable.

Rivers are full of time and water memory tells me time is another river. All faces pass like water and we get lost just like the river.

Vigil is a different kind of dream which dares not to be death and the most feared death of every night is called dream.

Find in days and years a symbol of mankind’s era and its years. Change the passing of years into music, a whisper and a symbol. See dreams in death, oh, sunshine, melancholic gold, such is poetry eternal and scarce. Poetry always returns like sunshine.

Time and again my face finds me on the other side of a mirror. Art must be like that mirror revealing our own face.

It is said that Ulysses, full of prodigies love-cried at the sight of Ithaca olive green and humble. Art is Ithaca infinitely green, empty of prodigies.

It is also like this river, so endless which passes and stays, a crystal of you erratic Heraclitus, you and another, like the river, ever so endless.

In mijn droom was mijn oma weer een klein meisje, soort zusje.

Het regende dus ze droeg laarzen en een jasje van plastic dat glom.

Hinkte om me heen onmogelijk vlug: voor, links, achter, rechts en terug op het andere been.

Bij elke sprong werd ze een klein beetje jonger en ik riep voor zover ik in mijn droom roepen kon: oma met miljoen lichamen! stop, we blijven altijd samen.

In my dream, my Gran was a little girl again, a kind of sister.

It was raining, so she wore wellies and a jacket of plastic shining bright.

Hopscotched around me impossibly fast: ahead, right, back, left, and back on the other leg.

With each jump she grew a bit younger and I cried as far as I could cry in my dream: Gran with a million lives!

Wait, we’ll stay together forever.

One night as I lay sleeping, a strange dream came to me I dreamed I was up in Croke Park where Wicklowmen long to be, It was All-Ireland final day and our hearts with hope filled up Wicklow were playing Fermanagh for the Sam Maguire Cup Wicklow’s Captain was an Aughrim man for whom we’ve much esteem

As he proudly stepped into the fray as leader of our team. We cheered and clapped so loudly there from the Hogan Stand, As the teams paraded ‘round the pitch to the Michael Dwyer Pipe Band.

Well, we did as we were ordered, sure the roads were chockablock. Somehow we lost our bearings, and landed in Kilcock, The shouts of “Come on Wicklow!” filled the balmy evening air

As we gloated in our victory ‘round the Curragh of Kildare And as evening was closing in, and amidst all the joy and fuss, We headed back to Aughrim on the Tinakilly bus. So coming near Andy Allen Park I suddenly woke up, I looked around; there was no team, no bus, and worst of all, no cup. Well again we keep on hoping that we’ll soon realise our dream. In the meantime, let us all get out and support our senior football team.

Oíche amháin is mé i mo chodladh, tháinig brionglóid ait chugam. Bhí taibhreamh agam go raibh mé i bPáirc an Chrócaigh, áit a bhraithimid uainn a bheith.

Cluiche Ceannais na hÉireann a bhí ann , is líonadh ár gcroí lán le misneach. Bhí Cill Mhantáin ag imirt i gcoinne Fhear Manach don Chorn Sam Mhic Uidhir. Fear ó Eochraim a bhí mar chaptaen na foirne, fear a raibh meas mór againn air.

Nuair a thug sé céim i gcomhrac mar cheann foirne Chill Mhantáin. Lig an lucht féachana molta astu ó Ardán Uí Ógáin Mháirseáil na foirne timpeall na páirce don Bhanna Píob Mhichíl Uí Dhuibhir

Bhuel, rinneamar mar a dúradh linn, nach raibh na sráideanna ag cur thar maoil.