Study of Open Inquiry & Viewpoint Diversity at Trinity School

Margarita Curtis, Rick Melvoin, Vance Wilson

May 11, 2023

Margarita Curtis, Rick Melvoin, Vance Wilson

May 11, 2023

Autumn 2022 – Strategic School Leadership LLC (“SSL”) was retained by the Trinity School Board in the a�ermath of the situa�on involving faculty member Ginn Norris and Project Veritas. The three partners from SSL who agreed to engage in this work are:

Margarita Curtis, PhD. – former Modern Language Department Chair and Dean of Studies at Phillips Academy Andover and for 13 years Head of School at Deerfield Academy in western Massachusets

Richard I. Melvoin, PhD. – former History Department chair and Dean of Studies at Deerfield Academy, former Assistant Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid at Harvard College, and for 25 years Head of School at Belmont Hill School, located near Boston, Massachusets

Z. Vance Wilson – long�me English teacher, English Department chair and administrator at several independent schools before serving for 19 years as Headmaster of St. Albans School in Washington, D.C.

December 7-8, 2022 – SSL spent two days on Trinity’s campus, mee�ng various representa�ves of the school, including the Advisory Commitee established to help in this work (and including parents, faculty and trustees), and refining the work ahead.

December 2022 – In the a�ermath of the on-campus visit, SSL considered several firms to help SSL and Trinity conduct a survey of students, faculty and staff, and parents to explore issues of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” at Trinity. SSL presented two candidates to Trinity, and Head of School John Allman par�cipated in Zoom interviews with the two finalists. SSL and Trinity decided to work with the firm Mission & Data LLC (www.missionanddata.com). The three M&D partners engaged in this work were Ari Betoff, Sarah Enterline, and Avis Leveret.

January 2023 – SSL and Mission & Data worked together to dra� a survey instrument for Trinity. With significant review and revision from Trinity, notably via the Head of School and Board chair, M&D completed a revised survey by the end of the month.

February 2023 – M&D administered the survey and then dra�ed a report that summarized its findings. That was reviewed and revised by SSL. A 9-page slide deck was created out of the report for SSL to use when it visited school.

March 13-16, 2023 – The three members of the SSL team spent four full days at Trinity. The goals in every mee�ng they led were the same and three-fold: to review the findings from the survey, to respond to ques�ons or comments, and to seek ideas for how Trinity could make changes to enhance opportuni�es for open inquiry and expressions of viewpoint diversity, both in and out of the classroom.

SSL met with 28 groups over the four days:

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

Eleven Student Mee�ngs: focus groups in every grade level from grade 6 through 12, open mee�ngs for any interested students in grades 9/10 and11/12, and mee�ngs with the Upper School Senate and SDLC (Student Diversity Leadership Council)

Eight Faculty Mee�ngs: separate mee�ngs for Lower, Middle and Upper School facul�es, two open mee�ngs for any faculty and staff, mee�ngs with the History and English departments, and a mee�ng with the Department Heads

Nine Parent Mee�ngs: 2 for parents in the Lower and Middle Schools, 3 for parents in the Upper School, plus mee�ngs with the PA DEI Commitees leadership and the PA Cabinet

In addi�on, SSL made itself available for individuals or couples who wanted to meet privately. There were 8 such mee�ngs.

April 25, 2023 - SSL returned to campus for the day to meet with the Advisory Commitee, the senior administra�ve team, and 15 members of the board of trustees to review its findings and dra� recommenda�ons. SSL also met with one addi�onal parent couple.

March/April 2023 - SSL dra�s a report to present to the Board at its mee�ng on May 11.

May 11, 2023 - SSL presents in person its report to the Board.

Strategic School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

“Free expression is not a problem with a solution bounded by the laws of physics that can be hacked together if only enough coders pull an all-nighter. It is a dilemma requiring messy trade-offs that leave no one happy. In such a business, humility and transparency count for a lot.”

The Economist (19 December 2022)

The purpose of this section of our report is to provide some overarching ideas that we three partners at Strategic School Leadership took from our visits to the school and from the results of the survey conducted by Mission and Data LLC. But any study of Trinity needs, first, to place the school in a larger context: in the world of schools, particularly independent schools, but also in New York City and in an America that is roiled by deep divisions and, often, a loss of civil discourse. (This report’s accompanying Reading List provides a representative sample of publications highlighting dimensions of this challenge.)

What we thus offer first are some general observations and points of context.

In addressing issues of open inquiry and viewpoint diversity, what Trinity is dealing with is not “a problem to get solved.” Instead, the school – to its credit – is leaning into a complicated, sometimes emotional set of issues that are impacting not only the school but much of American society. These issues can be “addressed” but there will never be perfect solutions.

In addressing these ideas, it is important to acknowledge that the world, this country, and Trinity School are very different than they were ten or seven or even three years ago.

• The political landscape is more polarized; divisions are greater than they were; anger and fear are greater – on all sides.

• One manifestation of that is the loss of clear understanding of different political beliefs, including such concepts as “liberal,” “conservative” and “progressive” – and in some places civil discourse has been lost or replaced by angry and divisive rhetoric.

• With that concern in mind, we urge care in use particularly of the word “liberal,” for in the western tradition of education, “liberal” has referred to (according to the Oxford Dictionary) “willing to accept or respect opinions different from one’s own; open to new ideas.”

• So too has the word “conservative,” which has a long and broadly accepted history in political and social theory, been of late misused, further limiting healthy discourse.

• Issues of racial and social justice have become more critical for many people in this country, including significant numbers of students, parents, teachers and administrators. These issues were becoming more central well before George Floyd’s killing in May of 2020, but gained significant momentum at that point.

• For many independent schools, Floyd’s killing became a flashpoint to examine, more deeply than ever before, their role in society. Points included:

- Schools’ histories in regard to addressing issues of race and inequality

- The harm that had been done to some students of color, especially black students, in the past that schools had not been aware of or had not responded to adequately

- The ways in which schools should address these issues, looking both backward and forward

- New questions about what a school’s mission should be in addressing issues of racial and social justice

• Challenges brought by social media continue to increase, as well as questions not only about what is “right” but even what is “true”

• Schools are still reckoning with the impact of the pandemic, not only in terms of learning loss but also in terms of the socialization of children and their social and emotional development

• The pandemic also had a damaging effect on the efforts of all schools to build community and, with that, trust. This extends not only to students and teachers but to parents as well.

In addition to the recent rise of the aforementioned issues, independent schools have felt for some time inexorably rising pressures in a range of programs and services, including:

• Achievement and success in athletics and other extra-curricular activities

• Providing sufficient support for students, particularly around social and emotional learning

• College admissions

These forces, when combined with more attention in schools to issues of diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging, have only exacerbated the pressures.

Amidst all that, it is also appropriate to note that, even as many schools have made commitments to greater engagement on issues of racial and social justice, there has been pushback from some community members, or at least tension, at both the scope and speed at which some schools have addressed these issues.

In viewing this complex web of forces, we urge caution not to conflate issues. Examination of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” is related to but is not identical to efforts in schools to address broader issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion (“DEI”). In looking specifically at Trinity, one of the tensions we uncovered is that some community members view – or fear – the examination of open inquiry and viewpoint diversity as an attempt to limit DEI efforts.

Another complexity in this work, at Trinity and at many other schools, is a distinction between efforts that promote diversity, equity and inclusion that relate to a broad array of ethnic, racial, religious, socioeconomic and even political groups versus particular efforts that focus on the African-American or Black experience in schools, in America’s past and in society today.

Our work at SSL has taken us to literally dozens of independent schools in the last three years. There is not a school we have worked with that has not faced these issues.

If there is a general pattern that we have observed in the schools with which we have worked, particularly in the northeast, it is that many faculties have shown significant commitment to this work; that large numbers of students support such efforts; that parents have had somewhat more mixed views; and that some boards of trustees have expressed concern about the extent and rate of change.

Three Constituencies – Three Lenses Three Sets of Observations

While any generalizations have their limits, after reviewing the survey data and talking with literally hundreds of Trinity students, teachers, and parents, we offer two different ways to consider where Trinity now sits in regard to the core issues of open inquiry and viewpoint diversity. First, we think it may be helpful to acknowledge that the three key constituencies at the school – students, faculty and staff, and parents – have different lenses through which they view the school. Thus, we think it is of value to outline different key themes that emerged from each group.

Faculty. Here are some ideas that focus on the faculty experience:

Many faculty members at Trinity (and at many schools, private and public) were deeply impacted by the political storm of recent years, accelerated by the 2016 election and then particularly by George Floyd’s killing and its aftermath. Many have asked themselves, and their schools: where do larger issues of social and racial justice fit into the education of young people? How should students learn about new or historically not represented voices or subject matter?

As noted above, it is also important not to conflate two issues. One is the issue of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” – but the other is Trinity School’s role in addressing issues of social and racial justice, especially in these inflamed times. To the latter: in what ways and to what degree should Trinity be addressing these issues? The efforts of the ARTF demonstrate significant commitment, and many in the community look now to see what the speed and extent of implementation of the Task Force recommendations will look like.

Yet one could add a third issue here: how does Trinity best work with its students, and its parents, in a world that is seeing rapid changes in addressing social issues, from gender expression and gender identity to microaggressions to changes in the study of history and the humanities to challenges of what is “true” to the role of media and social media?

Further, what is the proper role of a faculty member in teaching about these issues, or in integrating them into an existing program? Is a teacher’s job to introduce ideas without a point of view, or are some of these issues appropriate for a teacher to address directly, including expressing one’s own beliefs? As examples, should differing views of racism be given moral equivalency? Many people, at Trinity and beyond, would say no. Yet by possible contrast, should different views about gay marriage be considered, given that some in the Trinity community have religious or cultural views that do not support it?

We believe this issue – the proper roles for faculty in the classroom – lies at the heart of this entire study. Acknowledging its complexity, we add one more dimension of this challenge: the current debate now playing out on many college campuses over what constitutes “free speech.” This is a different issue than “open inquiry” or “viewpoint diversity” but it needs to be acknowledged, even if it might be separated from Trinity’s future discussions.

This issue becomes still more complex when one considers the historic “independence” of independent school teachers. Many teachers, particularly of long standing, have prized – and expected – autonomy in the classroom. How does a school honor significant autonomy but also maintain appropriate accountability? How much autonomy is desirable – by teachers, administrators, parents? How much is appropriate?

Amidst these challenges also lie new pressures that some teachers have felt since the pandemic began. There is great concern within the profession that there remains significant exhaustion from having to deal with the impact of Covid, with a reckoning of racial and social justice issues and, at least for a time, with new ways of teaching driven by the pandemic. Across the country, more teachers are leaving the profession, and many schools, even strong ones like Trinity, are seeing shrinking pools of qualified candidates. How can the school find, retain and support a strong faculty?

The faculty have instituted significant changes in curriculum over the last 10 years. While our time with faculty has been limited, we understand that these include:

• Major reworking of some curricular offerings, particularly in the History Department at the Upper School level

• New thinking about pedagogy, some of which comes in response to greater sensitivity to issues of difference among students at Trinity and among people in American society and in the world

• Additions to or changes in some of the programs of the Middle and Lower Schools, reflecting issues being discussed in society, that focus on issues of gender, sexual identity, race, ethnicity, religion, and socioeconomic status

How does Trinity provide a good balance between curricular and pedagogical innovation and its strong traditions? And how do changes get made and reviewed?

Parents. If the first set of issues focuses on the faculty, another broad set centers on parents. Some key issues:

Not only Trinity students and teachers but parents have been adversely affected by the pandemic. Numerous parents feel they have lost an easy level of access to the school that existed before March of 2020.

Understanding this, it may not be surprising that the Board’s initiating of a study of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” catalyzed a range of responses from parents that went significantly beyond the most immediate questions raised by the faculty matter of last fall. As one example, many Lower School parents particularly lamented the loss of daily time every morning that included the chance to come into the school building. Second, several parents

Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

expressed concern about some dimensions of the school’s DEIB efforts. In sum, many parents responded to the opportunity to participate in the Mission and Data survey by raising a host of issues that had given them concern over the last three years.

When one couples physical isolation with the political, racial and social issues that have roiled American society in the last several years, it is not surprising that some parents feel somewhat distant from the school. Some parents who have been part of Trinity for many years spoke wistfully about the sense of loss.

Given that feeling of isolation and separation, several parents feel a greater need for more or better communication from the school, especially as the school has continued to make changes in response to changes or challenges in society.

• One example is the issue of sexual identity and the number of people in American society, including students (some of them quite young), who see themselves as nonbinary: not fitting into traditional and historic “binary” divisions of male and female.

• A second example is the evolution of language used to describe students of different racial or ethnic backgrounds

• Curricular changes made by the school also reflect evolving thinking from faculty about the best possible course content. In history and social studies, that might include a more nuanced or complex look at people who have traditionally been seen as heroes. For example, how does one reconcile Thomas Jefferson as the author of the Declaration of Independence and as the holder of slaves through his lifetime? As part of that question, at what point in a child’s education is it appropriate to introduce such complexities?

Students. Trinity’s students are of course at the heart of the enterprise, living through these changes in school and society. Engaged and thoughtful, the students with whom we interacted wrote or spoke about a range of themes that have emerged for them:

As an important starting point, the survey results and our 11 meetings with student groups showed that Trinity’s students are generally very positive about their school.

It was striking that through four days of conversations with students in both the Middle and Upper Schools, little concern emerged about the use of social media platforms. Cell phones were ubiquitous in “The Swamp,” yet students did not express concern about misuse of social media, of inappropriate messages or shaming or “cancel culture.”

Students affirmed results from the survey that indicated strong overall support for teachers, yet several readily asserted that there are individual faculty who do not support or even allow for viewpoint diversity, at least on certain subjects.

Contrary to data from the survey, in conversations many Upper School students stated that students with conservative views were allowed to express their opinions, in and out of class, as long as they did not (to use a student’s phrase) “act like jerks.”

While some parents are concerned with Trinity introducing ideas about gender identity or matters of racial and social justice in classes or in special programs (seen particularly in the

Middle School program in grades 5-8, addressing gender, socioeconomic status, racism and unconscious bias), the students seemed unruffled by these. One Middle School student group explained that “we know all that already” – which may or may not be true, but which seemed noteworthy.

While the incident in the fall clearly upset many adults in the Trinity community, at this stage the students we heard from have moved past it. That does not mean that the students do not take the issues seriously – the February 2nd issue of the Trinity Times made this entire study of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” its lead story. But Upper School students seemed to have largely moved on, and most Middle Schoolers did not have much memory or understanding of the incident at all.

One of the more challenging dimensions of this study has been the effort to synthesize the quantitative and qualitative data of the “mixed methods” survey administered by Mission and Data LLC. It is a testament to how seriously the Trinity community has taken this study of open inquiry and viewpoint diversity that no fewer than 1221 members – students, parents, faculty and staff – took the time to fill out the survey. It is also impressive that 675 of those respondents also saw fit to add comments to augment the quantitative responses.

All three members of the SSL team read all the comments; we three also took an extra step of having each do a “deeper dive” into one of the three constituent groups (students, faculty/staff, parents), coding the responses, quantifying those that were positive, negative or mixed, and then writing up general themes or conclusions from each constituent group. The nine “observations and points for reflection and discussion” that follow here emerged from this work ONLY if they were seen in the qualitative review of all three constituent groups and complemented appropriately the quantitative data from the study. That does not mean that they represent a majority sentiment – but it does mean that all three groups had enough people raise the issues that they warranted inclusion in this set of observations.

We also note that a comprehensive summary of the Mission and Data survey accompanies this report, with a review of methods, process and statistical summaries. A shorter summary of that report, in the form of a Powerpoint, was used by SSL in conducting its 28 meetings with student, faculty and staff, and parent groups in March of 2023.

With that explanation of methodology as a framework, the nine ideas that we offer for reflection and discussion are:

1. All constituencies believe that most Trinity teachers are talented, committed, caring and interested in the different ideas of their students

2. An acknowledgement that Trinity, like many independent schools in New York (and beyond), has a liberal or “left-leaning” orientation – and that most members of the Trinity community in general are comfortable with that

3. While the majority of Trinity community members believe that students have great freedom to express their ideas, several community members asserted that openness to different views depends greatly on the teacher.

4. This survey of “open inquiry and viewpoint diversity” catalyzed a set of responses in the “comment” section, especially from parents, that went well beyond the core issue under study to include matters ranging from DEI efforts to school communications to teaching about gender

5. Despite letters from the Head of School and Board president, concern persists that Trinity’s study of viewpoint diversity might be seen as in direct conflict with the efforts of the AntiRacism Task Force (ARTF)

6. For some members of all constituencies – students, faculty and parents – there is significant peer pressure not to express views that are not liberal or progressive.

7. There exists fear among some that a student expressing dissent politically or culturally could lead to a lower grade from a teacher or, from fellow students, a loss of place or even ostracism.

8. There is concern that dominant social, religious or cultural beliefs at school make it difficult for some students to openly express their beliefs.

9. There is some worry that the rise of DEI work at Trinity, even though broadly supported, has ironically created, for some, an environment that belies the school’s goals of diversity and inclusion in examining some issues and has ushered in an “orthodoxy” that inhibits open inquiry and viewpoint diversity

Recommenda�on #1

Make the full SSL report, including the Mission and Data survey results, available to the en�re Trinity community.

We believe that a board request to all cons�tuencies to par�cipate in the survey should be mirrored by a willingness to share the results. Sharing the report can help enhance trust throughout the school community and encourage progress as the school moves forward.

Recommenda�on #2

Create a leadership group to review the SSL report and oversee implementa�on of recommenda�ons

• Leverage exper�se of administrators and faculty members who are interested in and excel at ppromo�ng open inquiry and viewpoint diversity.

• Charge the group with reviewing Trinity’s most recent strategic plan (Vision 2027), the An�Racism Task Force (ARTF) report, and this SSL report with a focus on points of convergence among the three studies.

• Engage in substan�ve discussion about both convergences and possible divergences among the three reports. Work with school leadership to determine next steps to ensure the fulfillment of ins�tu�onal goals and priori�es and to coordinate plans for implementa�on of proposed changes.

Recommenda�on #3

Remain student-facing.

• Keep the focus, from day-to-day opera�on to strategic thinking, on the best educa�on that can be offered to this genera�on of students, especially given the extraordinary societal changes and pressures they face.

• In determining points of convergence and divergence among the three studies, in each case ask what programs and prac�ces can best support the students of Trinity School not the board or administra�on, faculty, parents or alumni, but the current students.

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

Recommenda�on #4

Engage the faculty as central to this work.

• Provide the resources, most importantly the �me, for faculty to discuss the challenges they face in addressing open inquiry and viewpoint diversity, and consider appropriate steps forward.

• Ask the hard ques�ons. What do or should “open inquiry” and “viewpoint diversity” mean at Trinity School? When are they difficult or even undesirable? From the administra�on perspec�ve, how should this work be overseen at the school, including the ques�on of how much autonomy a teacher has or should be given, but also by what criteria teachers are hired, evaluated, and supported in professional development?

• Faculty work needs to be both internal – within the current faculty – and also outward facing.

• Bring to campus resources (speakers, programs, organiza�ons, readings) that focus on open inquiry and the effec�ve exchange of ideas (see the SSL report’s Resource and Readings sections)

• Be willing as a faculty to explore Trinity’s values, consider its norms, and examine both content and pedagogy.

• Ensure that this faculty effort results in concrete, specific steps to enhance open inquiry and viewpoint diversity as is appropriate for each of the three divisions and across academic disciplines.

Recommenda�on #5

Renew a schoolwide focus on community.

• Consider possibili�es for chapels (both individual events and ongoing programs), community �mes, debates, open mee�ngs, and any other gatherings devoted to students in all three divisions of the school.

• While support of viewpoint diversity should be part of these gatherings, so should a spirit of mutual support and affec�on for the school and for one another.

• Recognizing that the loss of community has been felt by parents as well as their children, find ways to enhance communica�on and appropriate contact at the school again with ini�a�ves for all three divisions.

• Remembering the toll that the pandemic and other issues have had on faculty and staff, find ways to honor and support the adults who make the school run every day.

• Finally, remembering the highest values of Trinity School, engage in this difficult but important work with good heart, good inten�on, and grace.

In this list we offer a representa�ve sample of publica�ons and websites that highlight recent controversies in schools and college campuses across the country, resul�ng from a variety of factors: speaker disinvita�ons, 'shout-downs,' demands to rename campus landmarks, community-wide diversity statements, safe spaces, speech codes, trigger warnings, and other measures that some view as barriers to open inquiry and viewpoint diversity.

We also include examples of policies and statements issued by colleges and universi�es in response to these incidents, highligh�ng their commitment to freedom of expression as a fundamental cons�tu�onal right, and as essen�al to the mission of the university in a democra�c society.

These selec�ons are followed by a list of recent ar�cles that emphasize the intersec�on and viability of free expression and inclusivity, and that promote a balance between open dialogue and the need to make all community members feel safe and included. The premise of this sec�on is that free speech can coexist with efforts

In the “Resources” sec�on we include several entries that provide guidance on how to foster construc�ve debate and dialogue across differences at academic ins�tu�ons, with the goal of equipping young people – and the teachers who mentor them with the tools, skills, and disposi�ons to par�cipate effec�vely and generously in a “poli�cally vibrant, mul�-racial, mul�-faith democracy.” (newpluralists.org).

A Chronological and Representa�ve Sample of Polariza�on and Conflict in Higher Ed

**Denotes Highly Recommended

• The Aspen Ins�tute. (2018, April 3). Clash of Values? College campuses, free speech, inclusion, and safe spaces [Video]. YouTube.

• Lukianoff, G., & Haidt, J. (2018). The coddling of the American mind: How good inten�ons and bad ideas are se�ng up a genera�on for failure. Penguin Press.

• ** Behrent, M.C. (Winter 2019). A tale of two arguments about free speech on campus. American Associa�on of University Professors.

Excerpt: AAUP’s Commitee on Government Rela�ons 2018 report, Campus Free-Speech

Legislation: History, Progress, and Problems. As the commitee’s report on campus free-speech legisla�on notes, “many of the most difficult issues surrounding free speech at present are about balancing unobstructed dialogue with the need to make all cons�tuencies on campus feel included.”

Strategic School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

• PEN America. (2019, October 21). Chasm in the classroom: Campus free speech in a divided America.

• McWhorter, J. (2021). Woke racism: How a new religion has betrayed Black America. Regnery Publishing.

• Steele, D. (2022, June 2). Afraid to speak up or out. Inside Higher Ed. Student reluctance to speak freely on campus rose again in the last two years, according to a survey. But are things as bad as the numbers indicate?

• Mounk, Y. (2022, June 16). The real chill on campus. The Atlantic. Most students are open to real debate. But their colleges are failing them.

• Flaherty, C. (2022, November 7). Divisive academic freedom conference proceeds Inside Higher Ed.

Controversial event on academic freedom at Stanford University goes forward amid controversy. Speakers include Amy Wax, Jordan Peterson, Scott Atlas, Joshua Katz and more.

• **Adichie, C.N. (2022, November 30). Freedom of speech – The Reith lectures. BBC Radio.

• Patel, V. (2023, January 8). A lecturer showed a painting of the prophet Muhammad. She lost her job. The New York Times.

• Hoffman, A. (2023, March 1). My liberal campus is pushing freethinkers to the right. The New York Times.

• Will, G.F. (2023, March 12). When it comes to a political craze based on a bad idea, worse really is better. The Washington Post.

• The Wall Street Journal (2023, March 14). DEI Is Dying On College Campuses. Or Is It?: Students weigh in on their experiences with diversity, equity and inclusion practices in higher education.

• French, D. (2023, March 23). Free Speech Doesn’t Mean Free Rein to Shout Down Others. The New York Times.

• Shields, J.A. (2023, March 23). Liberal Professors can rescue the GOP. The New York Times.

• Hilliard, J. and McLaren, M. (2023, March 28). Newton School Committee votes down controversial advisory panel, calling it ‘a Trojan horse.’ The Boston Globe.

• Hasnas, J. (2023, March 29). What does it take to really protect campus free speech? The James G. Marton Center for Academic Renewal at Duke University. Policy adoptions are useless without enforcement mechanisms.

• Knott, K. (2023, March 30). Republicans: Campus free speech under attack. Inside Higher Ed “My colleagues and I have the delicate job of considering how to ensure compliance through enforcement mechanisms that our law currently lacks.”

Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

• Rosman, K. (2023, April 12). Should college come with trigger warnings? At Cornell, it’s a ‘Hard No.’” The New York Times “We cannot accept this resolution as the actions it recommends would infringe on our core commitment to academic freedom and freedom of inquiry, and are at odds with the goals of a Cornell education,” Ms. Pollack [University President] wrote in a letter with the university provost, Michael I. Kotlikoff

• Alonso, J. (2023, April 13). Shouting down speakers who offend Insider Higher Ed “Over the course of a month, students on four different college campuses shut down speakers they disagreed with. Why is it so hard to forge a consensus on what protecting free speech really means?”

• Quinn, R. (2023, April 14). A Texas trilogy of anti-DEI, tenure bills. Inside Higher Ed. Three Texas bills would end tenure, force universities to fire professors who “attempt to compel” certain beliefs and ban what the legislation defines as diversity, equity and inclusion programming. The State Senate has already passed one.

• **French, D. (2023, April 16). The moral center is fighting back on elite college campuses. The New York Times. “It’s important to emphasize that the fight over free speech on campus is not left versus right. Attempts to suppress ideas and stifle speech come from both ends of the political spectrum. The faculty and administrators at Stanford, Cornell, Harvard and Chicago who are making their stands aren’t a collection of conservatives taking on woke college students. Instead, they represent the moral and legal center of the American academy taking on the extremes. Left and right tend to challenge free speech on campus in different ways. Left-leaning students have led shout-downs and disrupted events, while right-leaning legislators have passed or considered laws stifling the expression of controversial ideas about race and gender. Both sides have proved capable of mobilizing online outrage to punish professors who offend their constituencies.”

• Quinn, R…(2023, April 18). Tennessee Again Targets ‘Divisive Concepts’. Inside Higher Ed “While other Southern states advance legislation targeting what they define as DEI, Tennessee has passed legislation inviting complaints about professors.”

• **Backon, J. (2023, April 19). Letter. Intrepid Ed News: OESIS Network. “I spoke with a number of faculty members from different schools about the approach to integrating DEI into the curriculum. They were concerned that their school's emphasis on learning the history of the poor treatment of disadvantaged groups was being interpreted as an indictment of the white race; that white students were feeling guilty about acts and policies carried out by their predecessors, and in some cases, family and friends. The conclusion was that the goals of equity and belonging programs were not being enhanced, but rather inverted. The white majority was now being excluded in Ibram Kendi’s binary portrait: if you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem. How did our sincere efforts to improve equity and belonging yield the unintended consequence of reversing those efforts?”

oesis@oesisgroup.com

Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

• **Moody, J. (2023, April 21). Ex-Presidents for Academic Freedom. Inside Higher Ed “PEN America has convened a group of 100-plus former college presidents to push back on threats to academic freedom as higher education remains a frequent target for politicians.”

• Saul, S. (2023, April 23). At U.Va., an alumnus attacked diversity programs. Now he is on the Board. The New York Times. “Mr. Ellis is part of a growing and forceful movement fighting campus programs that promote diversity, equity and inclusion, known as D.E.I. Politicians, activists and alumni who oppose the programs say they enforce groupthink, establish arbitrary diversity goals, lower standards and waste money that could go to scholarships. Lawmakers in 19 states have taken up legislation to limit or block university D.E.I. program.”

• Knox, L. (2023, April 27). North Dakota quietly enacts first anti-DEI law Inside Higher Ed. “North Dakota governor Doug Burgum signed into law on Monday a “specified concepts” bill banning educational institutions from asking students or prospective employees about their commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) initiatives. It also prevents public higher education institutions from requiring noncredit diversity training of any students or employees.”

• Quinn, R. (2023, April 28). Hundreds of UNC professors oppose ‘overreach.’ Inside Higher Ed. “Faculty members are opposing what they consider encroachments from three sources: the state Legislature, the UNC Board of Governors and the Chapel Hill Board of Trustees itself.”

• University of Chicago. (1967). The Kalven Committee: Report on the University’s Role in Political and Social Action. “To perform its mission in the society, a university must sustain an extraordinary environment of freedom of inquiry and maintain an independence from political fashions, passions, and pressures. A university, if it is to be true to its faith in intellectual inquiry, must embrace, be hospitable to, and encourage the widest diversity of views within its own community... It cannot insist that all of its members favor a given view of social policy; if it takes collective action, therefore, it does so at the price of censuring any minority who do not agree with the view adopted... The neutrality of the university as an institution arises then not from a lack of courage nor out of indifference and insensitivity. It arises out of respect for free inquiry and the obligation to cherish a diversity of viewpoints. And this neutrality as an institution has its complement in the fullest freedom for its faculty and students as individuals to participate in political action and social protest. It finds its complement, too, in the obligation of the university to provide a forum for the most searching and candid discussion of public issues… From time to time instances will arise in which the society, or segments of it, threaten the very mission of the university and its values of free inquiry. In such a crisis, it becomes the obligation of the university as an institution to oppose such measures and actively to defend its interests and its values.”

• University of Chicago. (2014). Report of the Committee on Freedom of Expression. “But it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive. Although the University greatly values civility, and although all members of the University community share in the responsibility for maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility and mutual

Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community.”

• Princeton University. (2015). Princeton's commitment to freedom of expression.

• Williams College. (2019, November 13). Faculty Steering Committee's Statement on Free Inquiry and Inclusion.

• Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (2022). MIT Statement on Freedom of Expression and Academic Freedom.

“

We cannot prohibit speech that some experience as offensive or injurious. At the same time, MIT deeply values civility, mutual respect, and uninhibited, wide-open debate. In fostering such debate, we have a responsibility to express ourselves in ways that consider the prospect of offense and injury and the risk of discouraging others from expressing their own views. This responsibility complements, and does not conflict with, the right to free expression.”

• Martinez, J. S. (2023, March 22). Next Steps on Protests and Free Speech [Letter]. Stanford Law School

• Patel, V. (2023, April 9). At Stanford Law School, the Dean takes a stand for free speech. Will it work?. The New York Times.

A View from the Inside: The Higher Ed Perspec�ve

**Denotes Highly Recommended

• Hess, D. E., & McAvoy, P. (2014). Controversy in the classroom: The democratic power of discussion. Routledge. [Dean of the School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison].

• Hess, D. E., & McAvoy, P. (2015). The political classroom: Evidence and ethics in democratic education. Routledge. [Dean of the School of Education at the University of WisconsinMadison and Program Director of the Center for Ethics and Education at the University of Wisconsin-Madison]

• Sexton, John. (2020). Standing for reason: The university in a dogmatic age. Yale University Press. [President Emeritus, New York University]

A powerful case for the importance of universities as an antidote to the “secular dogmatism” that increasingly infects political discourse John Sexton argues that over six decades, a “secular dogmatism,” impenetrable by dialogue or reason, has come to dominate political discourse in America. Political positions, elevated to the status of doctrinal truths, now simply are “revealed.” Our leaders and our citizens suffer from an allergy to nuance and complexity, and the enterprise of thought is in danger. Sexton sees our universities, the engines of knowledge and stewards of thought, as the antidote, and he describes the policies university leaders must embrace if their

institutions are to serve this role. Acknowledging the reality of our increasingly interconnected world and drawing on his experience as president of New York University when it opened campuses in Abu Dhabi and Shanghai Sexton advocates for “global network universities” as a core aspect of a new educational landscape and as the crucial foundation-blocks of an interlocking world characterized by “secular ecumenism.”

• Knispel, S. (2022, October 21). Why free speech –and especially disagreement matters on college campuses. University of Rochester NewsCenter.

• **Diermeier, D. (2023, March 17). How to combat tribalism on campus. The Chronicle of Higher Education. [Chancellor of Vanderbilt University]

“The next step is to set explicit expectations for constructive conversations and hold students to a high standard. Just as we ask them to adhere to an honor code, we can ask students to uphold civil discourse as a core value. We can insist that they seek to understand first and judge later. We can oppose name-calling as a substitute for thoughtful argument and call out refusals to engage with the other side as counter to intellectual life. We can remind students that they are members of one community, committed to living and learning together — even when that means doing so alongside people with whom they disagree…. it’s incumbent on us to give students the resources and support they need to risk engaging with unlike-minded peers on highly charged issues... the most urgent free-speech question on our campuses isn’t just whether someone has the right to say something. It is whether we can teach students to talk with one another in a way that allows understanding and cooperation to follow.”

The Viability of DEI Efforts and Free Expression

**Denotes Highly Recommended

• Palfrey, J. (2017). Safe Spaces, Brace Spaces: Diversity and Free Expression in Education. MIT Press. [former head of school at Phillips Academy, Andover]

• Jay, J. (2017). Breaking Through Gridlock: The Power of Conversation in a Polarized World. Berrett-Koehler Publishers

• PEN America. (2019, March 13). And Campus for All: Diversity, Inclusion, and Free Speech at U.S. Universities.

• National Constitution Center. (2019, March 22). Free speech on college campuses: Administrators & free speech. [Video]. YouTube. Dean Ted Ruger of Penn Law, President Tom Sullivan of the University of Vermont, President Ken Gormley of Duquesne University, and President Julie Wollman of Widener University, examine how they balance free speech and inclusion interests on campus.

• **PEN America. (2019, April). Balancing free speech and inclusion: Four simple strategies for campus leaders.

Strategic School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

• Israel, T. (2020). Beyond your bubble: How to connect across the political divide, skills and strategies for conversations that work. American Psychological Association.

• Schultz, K., & Gatti, L. (Eds.). (2021). Learning and living in polarized times: Insights from conversations about social identity, polarization, and learning. Teachers College Press.

• **Stockman, F. (2022, November 5). This group has $100 million and a big goal: To fix America. The New York Times “In February 2020, in the midst of a vitriolic presidential election, an idealistic group of donors from across the ideological spectrum met to plan an ambitious new project. They called themselves the New Pluralists and pledged to spend a whopping $100 million over the next decade to fight polarization by funding face-to-face interactions among Americans across political, racial and religious divides.”

• American Council on Education. ACE, PEN America resource guide to help leaders make the case for academic freedom and institutional autonomy. (2023, February 24).

• NASPA. (2020). Free Speech and the Inclusive Campus: How Do We Foster the Campus Community We Want? NASPA-Student Affairs Administrators in Higher Education.

• O’Neil, E. and Fay, J. (2022, November 7). Discussing politics in classrooms is an opportunity for growth, not division. EdSurge. Five core principles of constructive dialogue

• Princeton University. (2023). The Intersection of Free Expression and Inclusivity.

• Wilfrid Laurier University. The Intersection of Freedom of Expression and Equity, Diversity and Inclusion. (n.d.).

• **Balaven, K. (2023, Spring). An educator’s recipe for depolarizing schools and selves. Independent School Magazine NAIS.

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

Across Differences at Academic Ins�tu�ons

• The Better Arguments Project

“The Better Arguments Project, a collaboration by the Aspen Institute Citizenship and American Identity Program, Allstate, and Facing History and Ourselves. It is a national civic initiative created to help bridge divides—not by papering over those divides but by helping people have Better Arguments… In partnership with communities and advisers around the country, we have synthesized three dimensions and five principles of a Better Argument… Better Arguments trainings are live, interactive webinars designed to teach the public about the Better Arguments Project’s approach to constructive disagreement. Our team offers two types of trainings – Better Arguments 101 and Better Arguments: Principles to Practice.”

“Join us for a one-hour introduction to the Better Arguments Project. Together, we will reflect on the role of arguments in a healthy democracy, and we will introduce the Three Dimensions and Five Principles of a Better Argument. If you are new to the Better Arguments Project or know someone who is interested in the program, this session is a perfect way to get started. Register or share today! Tuesday, May 23, 3 – 4 pm ET – Click here to RSVP .

• Facing History and Ourselves.

Facing History and Ourselves is a global non-profit organization founded in 1976. The organization's mission is to "use lessons of history to challenge teachers and their students to stand up to bigotry and hate… It is an active and continuous process that calls on each of us to connect the choices of the past to those we face today. To build a more just and equitable future, we must face our history in all its complexity. Our programs are designed and led by experienced former school leaders and teachers. We understand your school community’s strengths and challenges. Together we will work with you to identify and advance your school’s goals, nurture teachers' growth, and motivate young people to recognize their own agency and responsibility.”

• R.E.A.L.® Discussion skills for grades 6-12.

“Conversation is mission-critical for schools. It is at the heart of learning, belonging, well-being, and leadership. It’s how work gets done and relationships get built, in and beyond the classroom. At R.E.A.L.® we partner with future-focused school leaders to build mission - aligned programs for teaching and celebrating conversation skills on campus… For teachers facing a tech-centric world, in-class learning which relies on conversation – is becoming even more important. In an AI era, teachers need new tools for explicitly teaching – and equitably assessing – the human skills that robots can’t replace. At the top of the list? The oral and social skills students learn through live discussion.”

- NEW CASE STUDY, featuring work at Girls' Prep in TN

• Heterodox Academy: Great Minds don’t Always Think Alike. J. Haidt and N. Quinn Rosenkrans, co-founders, 2015.

- What is Viewpoint Diversity? * You Tube Video

Strategic School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

- Compendium of Resources for High School Educators

- Tools and Resources

- Constructive Dialogue Institute (J. Haidt)

• The Discussion Project: Learn to Discuss, Discuss to Learn School of Education, University of Wisconsin-Madison

The Discussion Project provides highly interactive in-person professional learning for institutions, educational leaders, and instructors. Through expert instruction, the course provides researchbased techniques to design and implement equitable, inclusive, and engaging classroom discussion. 7 Modules, 7 Learning Objectives.

- In-Person series in August 2023

- Free online workshop

• Bipartisan Policy Center. (2021). Campus Free Expression: A New Roadmap. Academic Leaders Task Force on Campus Free Expression.

• The Aspen Institute. (2023, February 22). Transforming Conflict on College Campuses. In partnership with our friends at the Constructive Dialogue Institute, our team co-authored an important new report called “Transforming Conflict on College Campuses.” In recent years, many college and university leaders have found it increasingly challenging to advance the mission of higher education in the context of a hyperpolarized national climate. We wrote this report to describe the undercurrent of conflict on campus and provide recommendations for moving forward. This report is intended as a peer-informed resource for higher education administrators, faculty, and staff by diagnosing the conflict and surfacing promising directions for addressing conflict on campus. It is already being used at colleges and universities around the country. Click here to read the full report.

• Citizen University, Eric Liu, CEO, non-profit organization. “We all have the power to make change happen in our communities — and the responsibility to try. Here at Citizen University, we equip civic catalysts with the ideas, strategies, and spirit to build a culture of powerful, responsible citizenship in cities across the country. In the Youth Collaboratory Program, high school students dive deep into how power works and who has it. This program brings together passionate students from all across the country for a year of insights, connections, and practice — learning how to build civic power for good. You’ll travel to cities across the nation, meet leading civic innovators from all corners of the country, and use what you learn to develop a personal Power Project.”

• New Pluralists

Many Voices, One Future: Building a Nation of Belonging for All. A project sponsored by the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors. “New Pluralists invests in strengthening the growing field that is addressing our nation’s crisis of division, distrust, dehumanization, and disconnection. We are focused on culture change — on shifting the norms, values, skills, and behaviors that shape the way we see each other and ourselves. This work advances a larger vision for change. Strengthening a pluralist culture

Strategic School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

complements the important structural change others are undertaking to enact policies and reform institutions.”

• Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE).

“Formerly known as the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education, is a non-profit civil liberties group founded in 1999 with the aim of protecting free speech rights on college campuses in the United States. [1][2][3] FIRE was renamed in June 2022, with its focus broadened to speech rights in American society in general.[4] Mission: FIRE defends and promotes the value of free speech for all Americans in our courtrooms, on our campuses, and in our culture.”

• The Sustained Dialogue Institute

“SDI works to improve community capacity to engage differences as strengths while helping people move from dialogue to action…We define dialogue as ‘listening deeply enough to be changed by what you learn.’ SDI provides workshops and educational trainings tailored to your institution’s needs.”

• Institute for Citizens and Scholars, Rajiv Vinnakota, President

“We’re on a mission to ensure that young people gain a deep understanding of our history, culture, government, institutions, and current affairs from diverse sources and perspectives. They vote, think critically, and have concern for the welfare of people of all backgrounds in their communities and across the nation. They debate and learn from each other, and work across difference to form a more perfect union. Now is the time to create an effective citizenry that strengthens democracy together…. The Civic Network is a New digital portal of self-directed learning experiences for American middle and high school-age learners from leading civic learning content providers. The Civic Network’s digital platform will be available to schools, libraries, afterschool programs, and other channels.”

• Harvard University Resources Democratic Knowledge Project,

“The Democratic Knowledge Project (DKP) is a K-16 civic education that offers curriculum development resources, professional development workshops for educators, and assessment tools and services all in support of education for democracy. Katie Giles, Strategic Initiatives Project Officer for the Democratic Knowledge Project, broadly oversees the DKP work areas in curriculum development, professional development, assessment and evaluation and strategy and policy.”

• Intercollegiate Civil Disagreement Partnership Fellowship, Edmond and Lily Safra Center for Ethics

“The intercollegiate Civil Disagreement Fellowship (ICDP) is our most recent fellowship opportunity for Harvard College undergraduates. The Intercollegiate Civil Disagreement Partnership (ICDP) is a consortium of five colleges and universities located throughout the United States. The mission of the ICDP is to advance fundamental democratic commitments to freedom of expression, equality, and agency; develop students’ skills to facilitate conversations across political difference; and create spaces for civil disagreement to flourish on college campuses. The core of the ICDP is a cross-institutional fellowship that brings together students from a range of public, private, two-year, and four-year institutions. The fellowship develops students' abilities to engage in and lead conversations about difficult, important topics across political difference at their respective universities and beyond.”

Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

• Elizabeth Block, Ethics, Harvard Graduate School of Education.

• IQ Squared - America's Debate Series

“Let's restore critical thinking, facts, reason, and civility to American public discourse. Watch or listen to Intelligence Squared debates on a variety of different topics. Hear From Both Sides. Balanced & Intelligent. Debate Research. Foster Critical Thinking.”

• P.T. Coleman, Professor of Psychology and Education, Columbia University, 2023 NAIS Annual Conference Speaker. Author of The Way Out: How to Overcome Toxic Polarization. Columbia University Press. 2020

“How can Americans loosen the grip of polarization and concentrate instead on solving the country’s most pressing problems? That’s the question Columbia University social psychologist Peter Coleman raises in The Way Out. He explores the ways that conflict resolution and complexity science can guide citizens who want to deal with seemingly intractable differences. He also goes into detail about principles and practices to help navigate and heal divides in homes, workplaces, and communities. Through a blend of personal accounts from his years of working on entrenched conflicts and the lessons Coleman has learned from research, The Way Out shares ways to break out of deeply rooted opposition and improve lives, relationships, and country.”

• Heather K. Gerken, Dean of Yale Law School

“Under Gerken’s leadership, the Law School admitted the five most diverse classes in its history with some of the highest yields ever, bringing in talented students from around the world with a strong record of academic performance and exceptional accomplishments. In the 10 years prior to 2016, an average of 32 percent of the student body were students of color. In the Class of 2024, approximately 54 percent are students of color and just over half are women. More than a quarter of the class is the first in their family to attend graduate or professional school and approximately one in six is the first in their family to graduate from college. Gerken and her administration have worked diligently to provide financial, professional, and mentoring support to students who come to the Law School without existing networks or financial support. She also helped nearly triple the number of veterans attending Yale Law School by expanding recruitment efforts and participation in the Yellow Ribbon Program. In addition, Gerken remains steadfast in her commitment to increasing faculty diversity, often partnering with other parts of the University to bring in renowned scholars from a diverse array of fields.”

• Jonathan Haidt, Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at the New York University Stern School of Business“Haidt has attracted both support and criticism for his critique of the current state of universities and his interpretation of progressive values. He has been named one of the "top global thinkers" by Foreign Policy magazine, and one of the "top world thinkers" by Prospect magazine. He is among the most cited researchers in political and moral psychology, and is considered among the top 25 most influential living psychologists.”

• Diana Hess, Dean of the School of Education, University of Wisconsin, Madison

“Since 1997, Hess has been researching how teachers engage their students in discussions of highly controversial political and constitutional issues, and what impact this approach to civic education has on what young people learn. Her first book on this topic, “Controversy in the Classroom: The Democratic Power of Discussion,” won the National Council for the Social Studies’ Exemplary Research Award in 2009. Her most recent book, “The Political Classroom: Evidence and Ethics in Democratic Education,” co-authored with Paula McAvoy, won the American Educational Research Association’s Outstanding Book Award in 2016 and the prestigious Grawemeyer Award in 2017.”

• Van Jones, CNN political contributor, host of the Van Jones Show and The Redemption Project, 2023 NAIS Annual Conference Speaker

Beyond the Messy Truth: How We Came Apart, How We Come Together. Ballantine Books. 2018

“As a progressive activist with roots in the conservative South, CNN commentator Van Jones wants to challenge citizens to disagree constructively while transforming collective anxiety into meaningful change. Beyond the Messy Truth is a call to individuals in both political parties to abandon the politics of accusation. A better way is “bipartisanship from below” a means to find practical answers to problems such as poverty and addiction that affect all Americans, regardless of region or ideology. The goal is to prompt Americans to abandon old ways of thinking about politics and instead come together and help those most in need. Throughout the book, Jones shares inspiring memories of his activism on behalf of working people, stories of ordinary citizens who became champions of their communities, and examples of cooperation amid partisan conflict”

• John Sexton. President Emeritus, and Benjamin F. Butler Professor of Law New York University. Author of Standing for reason: The university in a dogmatic age. Yale University Press. 2020

A powerful case for the importance of universities as an antidote to the “secular dogmatism” that increasingly infects political discourse. John Sexton argues that over six decades, a “secular dogmatism,” impenetrable by dialogue or reason, has come to dominate political discourse in America. Political positions, elevated to the status of doctrinal truths, now simply are “revealed.” Our leaders and our citizens suffer from an allergy to nuance and complexity, and the enterprise of thought is in danger. Sexton sees our universities, the engines of knowledge and stewards of thought, as the antidote, and he describes the policies university leaders must embrace if their institutions are to serve this role. Acknowledging the reality of our increasingly interconnected world and drawing on his experience as president of New York University when it opened campuses in Abu Dhabi and Shanghai Sexton advocates for “global network universities” as a core aspect of a new educational landscape and as the crucial foundation-blocks of an interlocking world characterized by “secular ecumenism.”

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

Immigra�ng from Cali, Colombia at age 12, Margarita O’Byrne Cur�s atended Ursuline Academy of New Orleans, then earned a B.A. (French) at Tulane and a B.S. (Educa�on) at Minnesota State University Mankato. She pursued her masters and Ph.D. in Romance Languages and Literatures at Harvard University.

A teacher at heart, Margarita won numerous accolades for her classroom work, rising to department chair and then Dean of Studies at Phillips Academy, Andover. During this �me she earned five Kenan Research Grants, published a book and several ar�cles on Spanish and La�n American literature, and par�cipated in over a dozen na�onal and interna�onal literary conferences.

Former Modern Language Department Chair and Dean of Studies at Phillips Academy Andover and Head of School at Deerfield Academy. During Margarita’s thirteen-year tenure as Head of School, Deerfield’s endowment grew by $250 million, financial aid doubled, professional development funding quadrupled, and $140 million of capital improvement projects were completed. Margarita transformed long-range planning at the Academy, delivering the school’s first-ever Strategic and Campus Master Plans and stewarding these plans through the impact of both the Great Recession and a major inves�ga�on into historical sexual misconduct. In this later challenge, Margarita established a new, higher standard for empathy and transparency with survivors and the media.

Having traveled and worked in 50+ countries, Margarita brings an inclusive, cosmopolitan ethic to her work and worldview: she believes that cultural competence drives innova�ve approaches to the world’s most pressing problems. At Deerfield, Margarita doubled the size of domes�c and interna�onal travel programs and emphasized DEI, bringing Deerfield’s first-ever Strategic Plan for Inclusion in 2016.

Margarita’s warm and energe�c nature has extended her impact. She served on several accredita�on visi�ng commitees, as the President of the Eight Schools Associa�on, and as a trustee of School Year Abroad and Global Connec�ons. She serves on the Board of Trustees of Los Nogales School in Bogotá, and of Rostro de Cristo, an organiza�on that facilitates service opportuni�es for high school and college students with marginalized popula�ons in Guayaquil, Ecuador. In the 2020-2021 school year, Margarita served as Interim President of Ursuline Academy the school she atended when first arriving in USA.

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

Rick Melvoin spent his en�re career in the world of educa�on. A graduate of Harvard College, with an M.A. and PhD. in history from the University of Michigan, he served as a teacher, coach, theater director, dormitory resident and, in �me, History Department chair and Dean of Studies at Deerfield Academy.

A�er five years as Assistant Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid at Harvard, he became Head of School at Belmont Hill and served there for 25 years. His experience in working with schools and boards runs deep. He was elected to the Board of Overseers at Harvard; he also served on the boards of The Winsor School, The Haverford School and The Epiphany School. He also has served as president of the boards of the Interna�onal Boys Schools Coali�on and The Headmasters Associa�on.

Currently he chairs the Governance Commitee as a member of the board of Facing History and Ourselves and chairs the Program Commitee for The Steppingstone Founda�on.

Vance Wilson has been a teacher, coach, dorm supervisor, department chair, dean of faculty, division Head, associate Head, and Head of school. He worked at four independent schools before becoming the Head of St. Albans School in Washington, DC, where he served for nineteen years. He received his B.A. from Yale College, a Diploma from Trinity College, University of Dublin, and his M.A. from the University of Virginia.

He has served on a number of boards and associa�ons, most notably as the chair of the Academic Services commitee of NAIS and Independent School’s editorial board, and as the President of the Interna�onal Boys’ School Coali�on. He was the co-inves�gator of the Klingenstein Programs at Teachers College, Columbia, a professor at Madison Area Technical College and an adjunct at the University of Delaware. Services on school boards include The Asheville School, Roxbury La�n School, and Tower Hill School, and associa�ons include the Mid-South Associa�on of Independent Schools, the Associa�on of Independent Schools in Greater Washington (AISGW) and the Associa�on of Independent Schools in Maryland (AIMS).

School Leadership: Serving school leaders so their schools may thrive.

This survey was commissioned by the Trinity School Board of Trustees, collaboratively designed by consultants from Strategic School Leadership, Mission & Data, and Trinity School leaders. The aim of the survey was to understand the degree to which:

● Trinity programs and practices provide for student expression of a diversity of viewpoints and promotes principles of open inquiry in and out of the classroom;

● the School fosters and hinders these expressions;

● the instructional practices used by the faculty foster civil dialogue; and,

● students feel they can express/not express unpopular or controversial viewpoints.

The survey was fielded in February, 2023 to all parents/caregivers with known and valid email addresses, to all current faculty and staff, and to all middle and upper school students. Survey results guided onsite work in March 13-16, 2023, facilitated by Strategic School Leadership and is here shared in summary form with the Board of Trustees and school leaders.

Viewpoint Expression - For most community members, Trinity is viewed favorably with regard to its promotion of open inquiry and fostering student experiences that reflect a diversity of viewpoints. Most community members believe that Trinity encourages students to be open to explore new ideas and that most classrooms are socially and emotionally safe spaces. However, political views and orientations (usually termed “conservative” and “liberal”) can cause discomfort, and many community members note a climate that is not open to those with more conservative political or social viewpoints. This concern was shared by some members of all three constituencies: students, faculty, and parents

Educational Beliefs - The viewpoints of Trinity community members are strongly on the side of endorsing teaching and learning that includes examination of individual attitudes and bias, openly discusses issues related to racism and inequity, incorporates diverse cultures and experiences, challenges school arrangements that maintain societal inequities, and dispels meritocratic views of success. Community members who endorse these beliefs are likely to have more favorable perceptions and experiences within the School, feel more comfortable expressing their viewpoints, and are less likely to withhold because of a worry of negative consequences. Community members who do not endorse these beliefs are likely to find themselves in the minority.

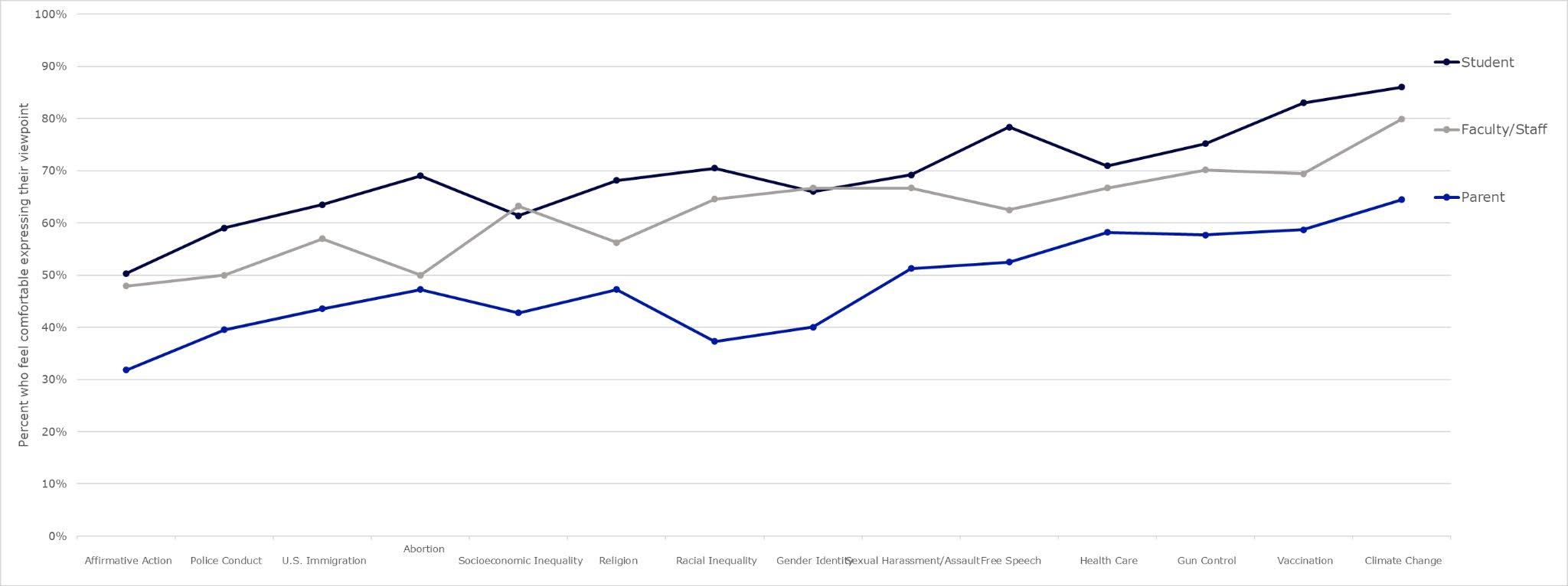

Constituency Group Differences - In many cases, the perceptions and experiences of parents/caregivers differ significantly from those of faculty, staff, and students. Parents are less likely to endorse the educational beliefs stated above, hold less favorable attitudes toward school practices, are less comfortable expressing controversial viewpoints, and are more likely to hold

back from sharing controversial views because they see a climate that is not open or encouraging or see no benefit to participating.

Gender and Ethnic Group Experiences – Students who identify as male are less likely to endorse the educational beliefs outlined above, view Trinity as less tolerant and welcoming of multiple viewpoints, yet are more likely to express a controversial viewpoint because they feel it is important to express their view; male community members are also more likely to hold back for fear of negative consequences. Community members who identify as people of color are more likely to find Trinity to be tolerant and welcoming of diverse viewpoints; however, community members who identify as Middle Eastern are less likely to share their opinions, and Trinity’s students, faculty and parents of color are hardly monolithic in their view.

Instructional Practices - Classroom teachers and Middle and Upper School students identified a variety of practices currently employed across many disciplines where teachers engage students in civil dialogue across diverse and divergent points of view. There is a clear pedagogical distinction between Lower School classrooms and Middle/Upper School classrooms. Students cite several examples of purposeful discussions where they are asked to role-play, research, and debate different views on a topic. Community Time experiences vary, particularly between Middle School and Upper School.

Consistent with Trinity’s aim of ensuring that all students feel a full sense of belonging, this survey was commissioned by the Board of Trustees, which identified a need to review institutional practices at Trinity that promote or inhibit student expression of a diverse range of viewpoints. The survey is also a response to an Anti-Racism Task Force (June 2021) recommendation to undertake more robust survey practices.

The survey aimed to understand the practices and processes used by Trinity School to foster open inquiry in its educational spaces. As the school’s mission statement makes clear, within the vibrant educational conversations at the heart of the Trinity experience, one of the school’s primary educational obligations is to “ask our young people what they believe in so they can know themselves in the world.” This survey sought feedback from the community in assessing how well the school provides students with the “tools of rigorous and passionate intellectual inquiry and self-expression” as students explore, question, and develop. In this way, Trinity strives to educate “thoughtful and persuasive citizens” able to engage in civil dialogue across diverse and divergent points of view.

The survey was collaboratively designed by the consultant teams at Strategic School Leadership and Mission & Data in partnership with John Allman, Head of School, David Perez, Chair of the Board of Trustees, and members of the Advisory Committee set up to support this work. The survey contained questions related to seven areas.

1. Respondent Demographics

2. Educational Beliefs

3. Individual Perceptions and Experiences

4. Instructional Practices

5. Comfort with Controversial

6. Reasons for Expressing a Controversial Viewpoint

7. Reasons for Withholding a Controversial Viewpoint

Survey responses were anonymous. The instrument was built and distributed via Qualtrics and data collection and analysis was overseen by Mission & Data. Survey findings in this report are provided to the consultants from Strategic School Leadership who are charged with both summarizing the results in their recommendations to the Board of Trustees and using the results to guide their work with the larger school community. Consultants from Strategic School Leadership will host focus groups and listening sessions with students, faculty, staff and parents to both review the survey data and seek input from the community regarding strategies and approaches that will allow Trinity to respond constructively to the survey results. In so doing, the consultants will seek to learn the ways that community members think the institutional response to the survey data can be informed by the recommendations of the Anti-Racism Task Force and Trinity Vision 2028.

The instrument was built and distributed via Qualtrics and data collection and analysis was overseen by Mission & Data. Each community member was emailed a unique link to the survey and up to two reminders. Unique links were single-use, meaning that they could only be used to submit one survey response.

Survey responses were anonymous. Links between community member email addresses and survey responses were removed via the survey platform. In addition, in order to maintain a high level of response anonymity, responses to close-ended questions are grouped in all analyses. Groups with less than 10 responses are not reported. However, open-response comments are reported below in several cases as they add to the narrative and understanding of the survey findings. Quotes are verbatim. Any mention of an individual person or potentially identifying information have been excluded from this report. All comments have been shared and read by the consultant teams at Strategic School Leadership and Mission & Data.

The survey fielding took place between February 8-21, 2023. Parents/Caregivers with valid email addresses were emailed the survey. Middle and Upper School students completed the survey during the school day at a designated time. Faculty and staff were emailed the survey to complete during the school day at their leisure. The median duration to complete the survey was 11 minutes, though this did differ between constituencies. Students averaged 9.3 minutes, parents/caregivers averaged 13.9 minutes, and faculty/staff averaged 14.2 minutes.

A total of 1,221 surveys were completed. Response rates were strong and reflective of a substantial effort by Trinity to ensure all community members had the opportunity to participate. In addition to the primary constituent groups surveyed, responses also reflected a small number of faculty/staff spouses, alumni, parents of alumni, and trustees who were also parents/caregivers; these individuals were included in analyses of parents.

Trustees who are not current parents were also surveyed. It is important to note that the parent group likely contains more than one response per household/family, for families with more than one parent/caregiver. Due to the survey anonymity specifications, the percentage of families represented cannot be determined, but it is likely considerably higher than the accompanying graph suggests

Demographic information was used to create respondent segments in order to analyze responses within and between groups. These segments included:

● Constituency Group;

● School Division;

● Gender; and

● Ethnicity.

*Note: 83% of responding faculty are classroom teachers

*Note: Faculty, staff, and parents/caregivers across all divisions were invited to participate, whereas only middle and upper school students participated.

*Note: 4% of chose “Prefer not to say” to gender

*Note: 38% of the respondents consider themselves a Person of Color

**Note: Less than 1% of the respondents chose Native American, North African, or Pacific Islander as their ethnicity.

Five survey questions were adapted from the Learning to Teach for Social Justice Beliefs scale (Ludlow, Enterline, Cochran-Smith, 2008) in order to ascertain the educational beliefs held by community members. Higher average scores correspond to higher endorsement (agreement) with these five items; lower average scores correspond to lower endorsement (disagreement) with these items. Items were randomly sorted by survey respondent to avoid ordering bias.

1. An important part of learning is examining one's own attitudes and beliefs about race, class, gender, abilities, sexual orientation, and other demographic differences.

2. Issues related to racism and inequity should be openly discussed in the classroom.

3. Good teaching incorporates diverse cultures and experiences into classroom lessons and discussions.

4. Part of the responsibilities of a teacher is to challenge school arrangements that maintain societal inequities.

5. Whether students succeed in school depends on many factors, not just on how hard they work.