8 minute read

In the Archives with Shan Goshorn

In the Archives with Shan Goshorn Gina Rappaport

and Heather A. Shannon

The contemporary historian has to establish the value of the study of the past, not as an end in itself, but as a way of providing perspectives on the present that contribute to the solution of problems peculiar to our own time.1

On October 22, 2013, Shan Goshorn emailed a number of Smithsonian Institution employees to thank them for facilitating her research during the first part of her Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship (SARF). We were among the recipients: Gina, the photo archivist at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA), and Heather, then the photo archivist at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) Archive Center. Shan returned to Tulsa, she wrote, with her “brain so full of information and ideas” that she had only just settled in to make baskets “motivated by [her] research” at the Smithsonian. She looked forward to returning to Washington, DC, to complete her fellowship and to show the new work to the Smithsonian archives and collections staff who had gone “out of the[ir] way to inspire” her research. She signed off: “In the belief of who we are, Shan.”2 In the belief of who we are. These words, so generously written, included rather than implicated us in a difficult shared history, and they made us part of Shan’s remedy—her solution—to the problems peculiar to our own time. She invited us to consider and feel with her the history, represented by archival records, of violence and oppression perpetrated against indigenous Americans. These same records, Shan made clear, also offered evidence of Native resistance, determination, and resilience. Shan gathered facts and information from a perspective fully alive to the implications of archival data. We watched her engage with the materials in the NAA and the NMAI archives on intellectual, emotional, and critical levels. These responses confirmed our own convictions that archival practice with respect to indigenous peoples is not just inadequate—it is problematic. Like the historian, Shan uses primary sources to reconstruct the past; however, the histories Shan tells are experienced rather than read. Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, a series of seven pairs of baskets (fig. 1), embodies Shan’s ability to reconfigure archives and their narrative potentials into a history to be experienced by the viewer. John Choate’s before-and-after photographs of Carlisle Indian School students serve as the source imagery of the baskets (figs. 2, 3). Richard Pratt, founder and superintendent of the school, commissioned the photographs to demonstrate the success of the institution’s mission to assimilate and acculturate Native children. The baskets confront us with the human cost—past and present—of Pratt’s notorious undertaking. The baskets also reveal to us the ways in which archival practices mediate access to collections and shape interpretation. Archival protocols, for example, dictate that researchers keep collection materials flat on the table, giving the researcher little choice but to understand

OPPOSITE

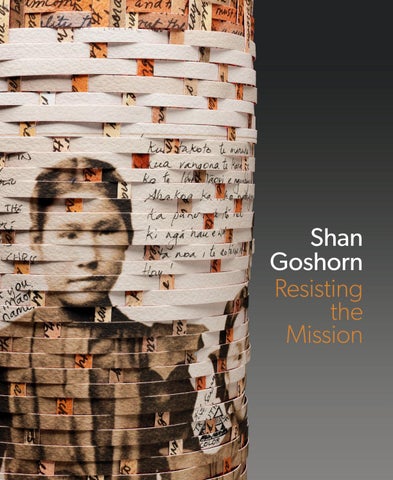

1. Shan Goshorn, Four Pueblo Children (Before/ After). One of seven pairs of baskets from Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, 2017. Archival inks, acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew. Artist’s collection.

ABOVE TOP

2. John N. Choate, Four Pueblo Children (Tsai au-tit-sa, Mary Ealy; Jan-i-uh-tit sa, Jennie Hammaker, Teai-e-seu-lu-ti-wa; Frank Cushing; Tra-wa-ea-tsa-lun-kia, Taylor Ealy) From Zuni, NM upon their arrival at Carlisle, ca. 1880. Albumen print. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA, PA-CH1-044a.

ABOVE BOTTOM

3. John N. Choate, Four Pueblo Children (Teai-e-se-ulu-ti-wa, Frank Cushing; Tra-wa-ea-tsa-lun-kia, Taylor Ealy; Tsai au-tit-sa, Mary Ealy; Jan-i-uh-tit sa, Jennie Hammaker) From Zuni, NM, after several months at Carlisle, ca. 1880. Albumen print. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA, PA-CH1-033a.

4. Detail of Four Pueblo Children (After).

5. Shan Goshorn working on Resisting the Mission: Filling the Silence, Tulsa, Oklahoma, 2017. them as two-dimensional. Yet Shan envisions these archival objects, both photographic and textual records, in three dimensions. The imposing height and columnar forms of the baskets give the children’s bodies volume and allow them to occupy our physical space. Compellingly, Shan does the same with texts. She renders Pratt’s speech, infamous for the phrase “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man,” three-dimensionally. In the baskets these words, printed on splints, lend structure to the bodies of the children, but like so many wounds, they also puncture the young bodies. Pratt’s speech, Shan reminds us, represents the lived trauma that manifested physically and mentally in the children and their descendants (fig. 4). In weaving together photographs and text, Shan transforms the documents. This transformation is an act of authorship whereby Shan strips away the authority that the archives confer on a document’s creator and on the document itself. For us, her appropriation of the documents underscores the problematic nature of archival structures and descriptions. The governing principles of archival management—provenance and original order—emphasize aspects of a collection that typically privilege the source or creator rather than the subjects represented. For example, with respect to the Carlisle photographs at the NAA, the collection is titled “The John N. Choate Photographs of Carlisle School Students.” The title emphasizes Choate’s relationship to the photographs (as their author) more than it does the children depicted. The naming convention subordinates the children to the maker of the photographs. Is Choate’s authorship necessarily the most significant attribute of these photographs? Shan’s intervention reminds us that, no, it is not. She cuts reproductions of the photographs into splints for the creation of a traditional form of Native art. This resolute act indicates that Choate’s authorship is perhaps the least important attribute of the photographs (fig. 5). By destroying and reconstituting the images, Shan restores the the children’s central importance to the photographs and unites us with the children’s histories. How do we, then, as stewards of repositories whose major focus is on indigenous peoples, build on Shan’s example? How do we establish the centrality of the children in the context of the archives? Shan’s baskets show us what is at stake if we fail: descendants and communities are unable to locate archival records; individuals remain nameless, their stories subsumed into an archival system whose logic is is often opaque to all but archivists. Our experience with Shan makes clear that we must depart from archival rules. As works of art, Shan’s baskets are an expression of her understanding of the world; they represent her subjective vision. Archives, on the other hand, have historically been mistaken to be objective—neutral receptacles for unbiased fragments of history.3 The very form of Shan’s art, the basket, calls to mind the archive. After all, like an archive, the basic function of a basket is to serve as a repository. As such, Shan’s baskets hold and generate collective memory; however, unlike the archives, they give voice to the enduring trauma of the boarding school experience. Assumptions of neutrality obscure the fact that the archives are complicit in the genesis and perpetuation of trauma sustained by indigenous Americans. Choate’s photographs arrest moments of trauma experienced by indigenous children. The photographs’ inclusion in the archives consigns the trauma to the past. Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence argues otherwise. Shan’s engagement with a traditional art may put us in mind of the archives, but her baskets eliminate the distance between the past and present, and potentially the future. The splints of the basket interior are printed with the names of the more than 8,000 children who attended Carlisle, while those on the exterior have been annotated by contemporary community members. Together, the interior and exterior splints reveal, rather than conceal, generational trauma (fig. 6). The baskets point to the subjective nature of archives and their contents and thus erode the notion of archival neutrality and objectivity.

At the Smithsonian, as at so many other institutions, Western perspectives permeate archival collections and the standards used to arrange and describe them. What would happen if archivists broke with professional standards to accommodate other perspectives, other voices? In her catalog essay for Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, Shan recounts an interaction with a Native elder at the 2010 Red Earth Indian Show in Oklahoma City. After taking in the first of Shan’s Carlisle baskets, Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian School (fig. 7), the elder was moved to tears. She encouraged Shan to place the basket in a museum, where it would “tell our story.” Shan uses the archives to help tell that story. But her baskets also tell a story of the archives and have implications for our work as stewards of archival records. Shan’s work resists the pretense of archival neutrality. So must we.

NOTES

1. Hayden V. White, Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978), 41.

2. Shan Goshorn, “Post SARF visit,” email message to the authors, 2013.

3. For a revised view of archival neutrality, see Verne Harris, “Postmodernism and Archival Appraisal: Seven Theses,” South African Archives Journal 40 (1998): 48–50; Randall C. Jimerson, Archives Power: Memory, Accountability, and Social Justice (Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2009); Joan M. Schwartz and Terry Cook, “Archives, Records and Power: The Making of Modern Memory,” Archival Science 2, no.1–2 (2002): 1–19; and Francis X. Blouin and William G. Rosenberg, Processing the Past: Contesting Authority in History and the Archives (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011). 6. Detail of Four Pueblo Children (Before).

7. Shan Goshorn, Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, 2011. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew. Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ. Museum purchase, acquisition fund; 2015.12.a, b. Photo: Peter Jacobs.