36 minute read

Exhibition Catalogue

Large Baskets

Two Views, 2018 Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, 2017 The Fire Within, 2016 Swept Away, 2016 Prayers for Our Children, 2015 Unexpected Gift, 2015 Unsolicited Gifts, or How to Eliminate a Culture, 2012 Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian

Boarding School, 2011

Medium Baskets

Red, White and Blue, 2017 Remaining a Child, 2017 Loss, 2016 Roll Call, 2016 Red Flag, 2015 Shrouded in Grey, 2015 Civilization, 2013 Despite (a.k.a. Three Sisters), 2012

Small Baskets

Direct Link, 2017 Lure, 2017 Marketable, 2017 Red to White, 2017 Valuable, 2017 Decline, Challenged, 2014 On the Shoulders of a Child, 2013 Forever a Part of Us, 2012

Catalogue entries: Shan Goshorn All dimensions height by width by depth.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 14 ¼ x 13 ½ x 13 ½ (36.2 x 34.3 x 34.3 cm) The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania Purchased with funds from the Friends of The Trout Gallery, 2018.12

Weaving technique: Cherokee double-weave; Blackbird’s-Eye pattern; the white, black, blue, and yellow splints refer to the four sacred colors of the Navajo.

Inscriptions: white, black, blue, and yellow splints: Navajo prayer for well-being; tan splints: Torlino’s Carlisle Indian School student records; rust-colored splints: family stories of Torlino’s life (as told by his oldest son, Francis, to his great-great-greatgranddaughter, Nonabah Sam).

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, Tom Torlino, c. 1882; John N. Choate, Tom Torlino, c. 1885. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

Diné (Navajo) student Tom Torlino (or Tolino) is the iconic representation of a “success” as touted by the Carlisle Indian School administration. Arriving at the school as a young man, Torlino interrupted his traditional training as a medicine man to learn “white man” ways. After four years, Torlino’s transformation was considered by the school’s superintendent, Richard H. Pratt, to be one of the most notable cases for support, recruitment, and promotion through before-and-after photographs made of the student. In this basket, the photographs of Torlino are interwoven into a single image.

Many students who attended boarding schools faced identity issues when they returned home, never feeling as though they fit fully into their Native culture or the dominant white society. Upon Torlino’s return to Coyote Canyon (Brimhall), New Mexico, he resumed his traditional studies and served as medicine man for his people. He also served as translator for the first Navajo chairman, Chee Dodge. His experience at Carlisle reshaped and reinformed his life, allowing him to shift between both Diné and white customs. Although he served his people in multiple traditional capacities, they always called him “Has’tíín Bilígánáá” (White Man), due to his hair, which he kept short. Per the wishes of Tom Torlino, the family remains active and true to their Diné teachings, but also greatly respectful of the value of continued education.

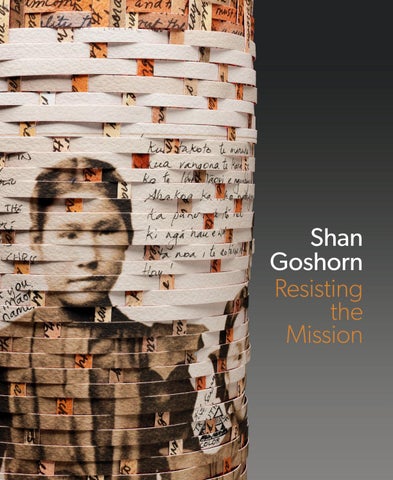

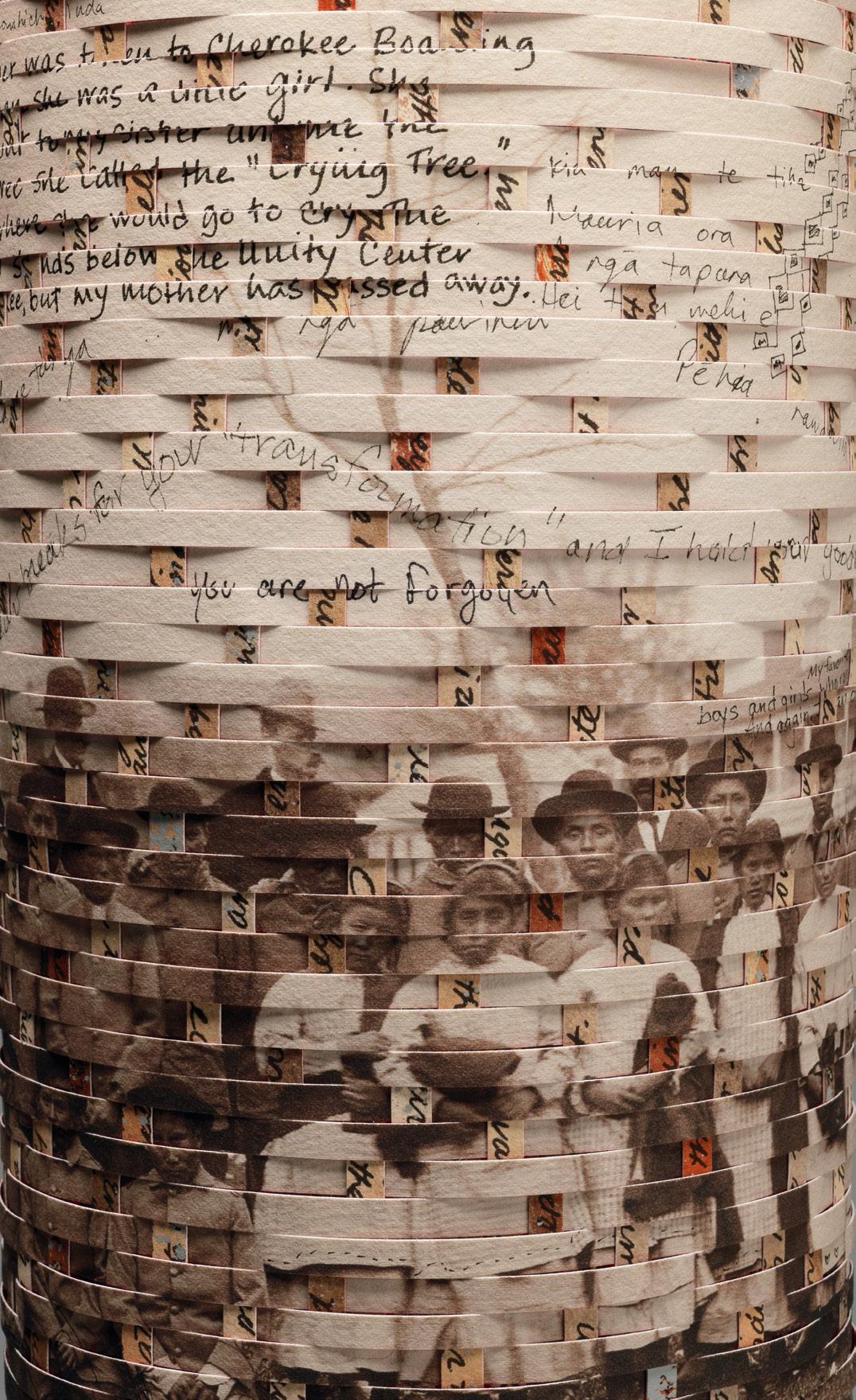

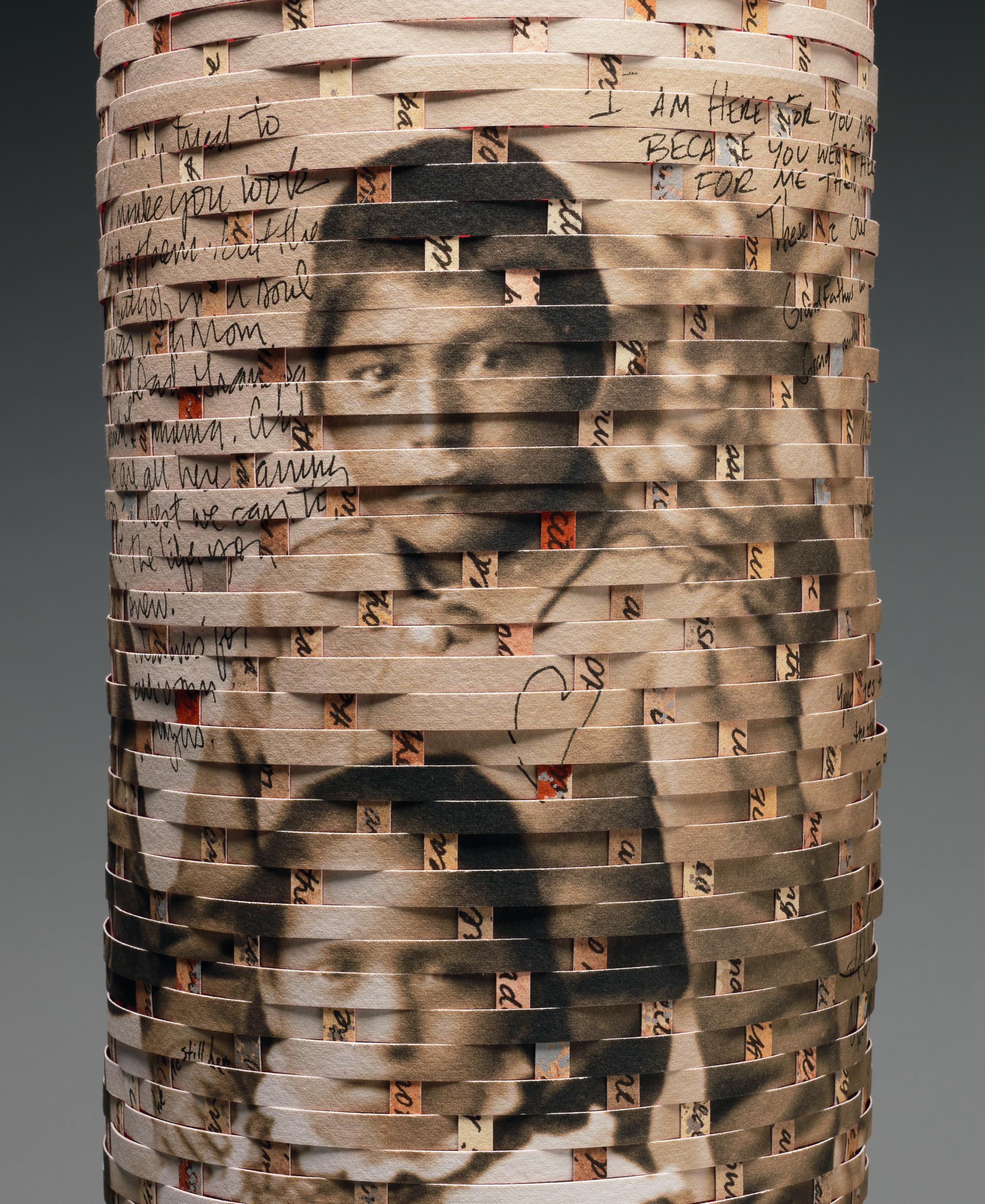

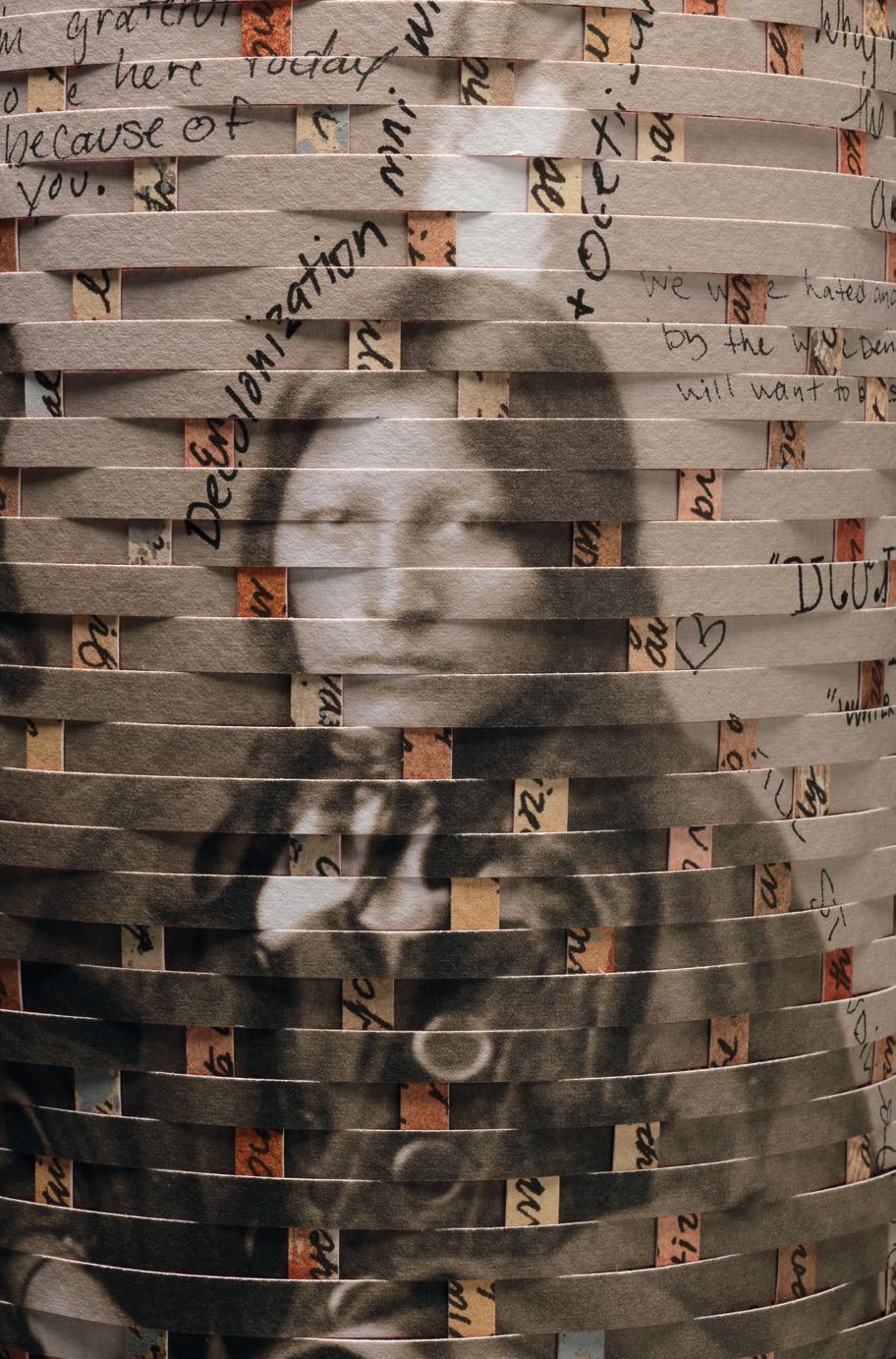

Resisting the Mission began with the well-known before-and-after photographs taken of the Native children. These photographs were made upon their arrival at the Carlisle Indian School and, again, after some time spent there, to illustrate the purported efficacy of the school’s assimilationist objectives. The photographs are maintained in a number of collections, including the National Museum of the American Indian and the National Anthropological Archives, both Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; and the Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Over the course of a year, I encouraged varied community interactions, asking people to write their comments directly on the surface of these enlarged reproductions before I cut them into splints and wove them into baskets. Their remarks are heartfelt and poetically beautiful, ranging from family stories of tribal members who attended this iconic institution to remorse about the way these children were treated during this ugly part of US history. The Carlisle Indian School’s assimilation campaign was a heinous attempt to destroy an entire culture through government-sanctioned whitewashing techniques. Historical trauma still haunts Native people as a result of this deliberate theft of language, family, and culture. I hope this piece will give audiences, especially Native people, an opportunity to overcome the silence that has been suffered for too long. “We remember your sacrifices. You have not been forgotten.”

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of students (Kokleluk, Esanetuck, Coogidlore Tumasock, Aneebuck, Lablok) from Port Clarence, Alaska (c. 1897–98). National Anthropological Archives, Washington, DC.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of Chiricahua Apache students from Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida (Clement Seanilzay, Beatrice Kiahtel, Janette Pahgostatum, Margaret Y. Nadasthilah, Frederick Eskelseah, Humphrey Escharzay, Samson Noran, Basil Ekarden, Hugh Chee, Bishop Eatennah, Ernest Hogee), c. 1886–87. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: exteriors: written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; interiors: names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of Pueblo students from Zuni, New Mexico (Frank Cushing, Taylor Ealy, Mary Ealy, Jennie Hammaker), c. 1880. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of Sioux Students (Richard [Wounded] Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear, Timber [Chauncey] Yellow Robe), c. 1883. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of Pubelo Girls (despite the title, their attire suggests Plains Indian influence), c. 1884–85. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Pair of before-and-after baskets: each 21 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist's collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exteriors) written comments by contemporary community members; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (interiors) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic sources: John N. Choate, before-and-after images of Navajo students (Manuelito Chou, Manuelito Chequito, Benjamin Damon, Charles Damon, Saahtlie, Tom Torlino, Antoinette Williams, George Williams, and four unidentified students). Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Archival inks, acrylic paint, and copper foil on paper, polyester sinew 19 ½ x 15 x 15 in. (49.5 x 38.1 38.1 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (exterior) red splints: the names of Cherokee students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; charcoal-colored splints: text from the Indian Removal Act of 1830; (interior) recent writing about growing up Cherokee (written in the Cherokee syllabary using a digital font).

This basket is woven in a contemporary shape of my own making, inspired by the Cherokee seven-sided star, which represents the seven tribal clans. It also refers to the central Council House fire, the importance of which cannot be underestimated. In the fall, at the beginning of every new year, all personal family fires are extinguished and relit from embers of this eternal sacred fire, symbolizing rebirth and tribal continuity, connecting our past to the future. Each clan is represented by a distinct wood, contributing a “V” portion of the star border that surrounded the central fire. The basket interior features a ring of brightly burning fires referencing the eternal flame (embers from the original Council House fire were carried to Oklahoma and then back to Cherokee, North Carolina) and the rekindling of contemporary Cherokee people’s passion to reclaim our cultural birthright and traditions.

Interwoven into the basket exterior are texts associated with matters that were devastating to Cherokee culture: the Carlisle Indian School and the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the latter of which led to the journey known now as the Trail of Tears. Inside the basket is the text of recent writing about what it is like to grow up as a Cherokee, written in the Cherokee syllabary (in a digital font), to represent our active desire to never again relinquish our traditions.

The basket’s internal fires break through to the exterior documents, illustrating the way we will overcome historical trauma by relying on the teachings of our ancestors.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 15 x 30 x 11 in. (38.1 x 2 76.2 x 7.9 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Water pattern.

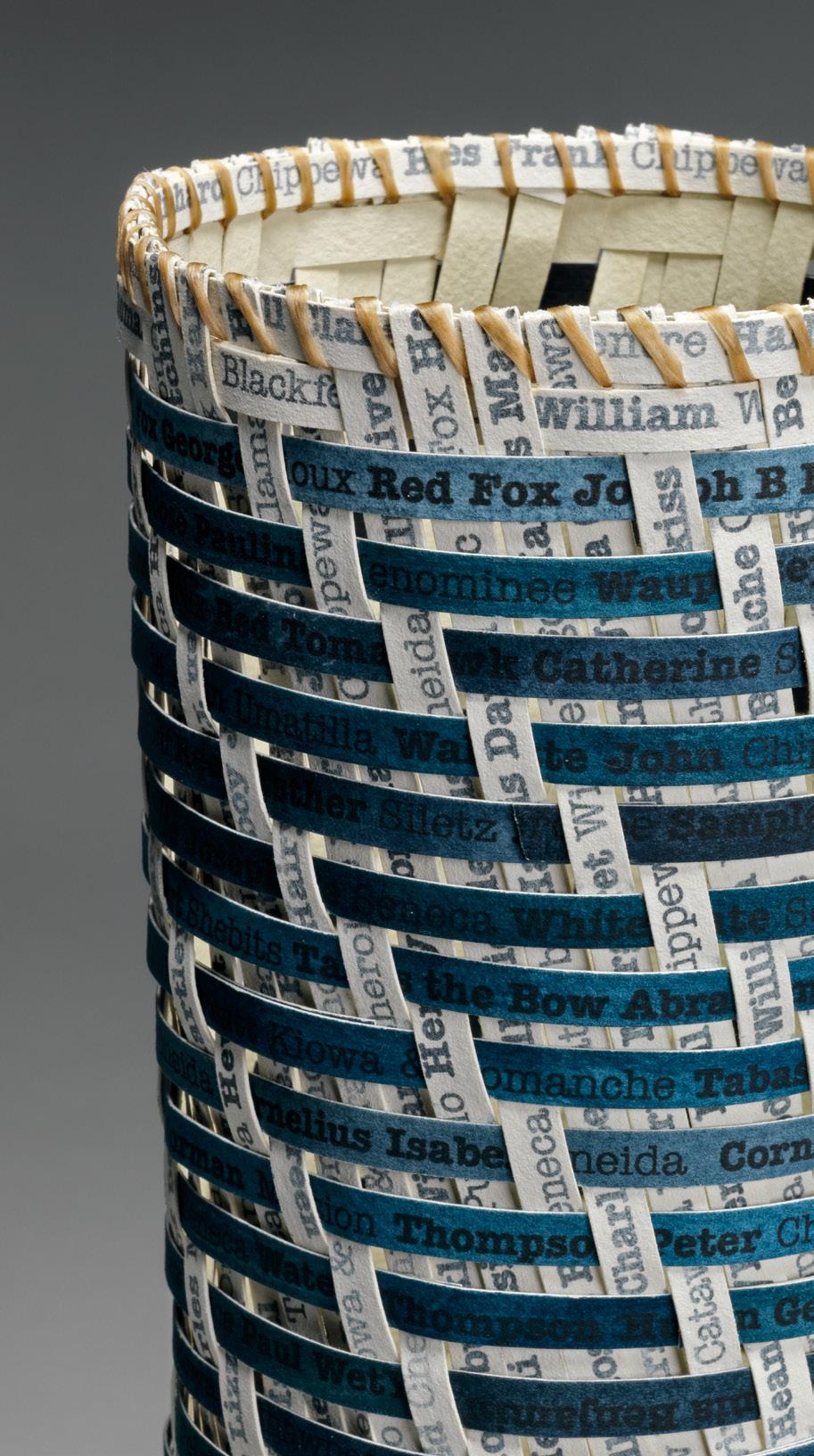

Inscriptions: names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic source: Tuckaseegee River, North Carolina.

The idea for this piece visited me in a dream. The resulting work is a three-dimensional interpretation of the basic Cherokee basketry pattern called “water,” a design that is included around the base and the rim. The finished basket is woven in a familiar Cherokee weave, but expanded so that the entire basket assumes the zigzag of the pattern. Wrapping around the basket is a mournful, evening photo of the Tuckaseegee River flowing through the ancestral Cherokee homeland. This image, along with the river-like shape of the basket and plunging blue interior, epitomize the deep sorrow and dark tide of removal experienced by Indian communities throughout the northern hemisphere over the sweeping loss of their children and way of life. The interior features reproductions of the Carlisle student roster as evidence that we remember and honor the sacrifices these children were forced to endure.

20 ½ x 11 ¼ x 11 ¼ in. (52.1 x 28.6 x 28.6 cm) Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Sam Wertheimer and Pamela Rosenthal Collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Cross-on-a-Hill pattern.

Inscriptions: (exterior) names and tribes of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; prayers of healing and well-being in Navajo, Lakota, Kaw, and Cherokee; lyrics to “We remember your sacrifices. You will not be forgotten.”

Photographic source: John N. Chaote, Carlisle Indian School Student Body, 1884. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

This basket includes the first photograph I saw at the National Anthropological Archives (NAA) representing children at the Carlisle Indian School. The NAA staff pulled it for me knowing that I was interested in seeing images from boarding schools, but I was not prepared for the imperial size or the content of this image. It was so exceedingly emotional for me to see the solemn brown faces, the shorn hair, and the stiff military uniforms on these little children that I had to leave the room to compose myself. I’ve been thinking about this image ever since, knowing that patience was critical and that I would eventually be shown the best way to include this photo in my work. I wove this image into the exterior of this basket, integrating with relevant texts.

Included throughout the interior of the basket, and within the crosses of the exterior, are the names and tribes of the more than 8,000 children listed on the Carlisle student roster during its thirty-nine-year existence. Despite the name of the traditional Cherokee weaving pattern—Cross-on-a-Hill—I use it here to symbolize the sanctity of the children, reminiscent of bright points of light in their vast sea of sorrow. Woven into the basket are prayers of healing and well-being in the Navajo, Lakota, Kaw, and Cherokee languages. Also included are the words to a memorial song: “We remember your sacrifices. You will not be forgotten.” The enclosed shape is interpretive of a protective embrace, symbolically comforting these beautiful children.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 16 ½ x 10 x 10 in. (41.9 x 25.4 x 24.4 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; variation of the Unbroken Friendship pattern.

Inscriptions: names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic source: John N. Choate, Carlisle Indian School Student Body, 1912. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian, Washington, DC.

Boarding schools are viewed by most Indian people as a crushing detriment to Native culture. But I see one very positive influence that I have never heard discussed: namely, the relationships that were formed among the students as a result of being sequestered with other children experiencing the same sad circumstances. Students learned to rely on each other as surrogate siblings, many marriages were later made based on these childhood friendships, and the bonds between tribes was cemented. Even today, reunions for Indian boarding schools are well attended, with former students often traveling across the country for the opportunity to reconnect with lifelong friends.

In this basket, I have included my great-grandmother’s personal recollection of attending boarding school, written in my hand (blue splints), along with my mother’s handwritten memoirs of her Cherokee boarding school experience (white splints). I am adopted by a 90-year-old Kiowa woman, and she penned Indian names (yellow splints), many of which are the last names of friends she made from her many years at Chilocco and Haskell Indian boarding schools. I combined these documents with an image of children newly arrived at Carlisle Indian School; the red interior interlaces names from the student roster of this same institution. The handprints wrapping around the exterior are an ancient way of demonstrating ownership. I use them here to illustrate how these experiences belong to us as Indian people and how we are all connected. The pattern is a variation of a Cherokee design called Unbroken Friendship. I love how, in this use, the pattern shifted on each corner to include a grouping of three crosses instead of one, as if embracing future offspring. Our love extends through generations.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 7 x 16 x 11 in. (17.8 x 40.1 x 27.9 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee double weave.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; Indian Removal Act of 1830; list of commodities with Indian names; New Testament.

Photographic source: alcohol bottles. The devastation that Native people have experienced in their struggle to maintain culture and identity can be attributed, in part, to the removal of children from loving families to raise them in military institutions; the denial of people’s right to live in their homelands; the inability to cultivate and maintain a traditional diet, with devastating results on health; the introduction of alcoholism; the criminalization of traditional religions; and the effect of a dominant society comically using Native images, names, and ceremonies for entertainment.

This basket features splints printed with a variety of documents and images that represent uninvited burdens brought to the first people of this country by the new settlers, all of which have contributed to the demise of Native culture. Included are a boarding school manifesto, a removal treaty, labels from cans of commodity foods, images of bottles of alcohol, the New Testament, and a list of the stereotypical usage of Indians to promote commercial products including mascots.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 12 x 20 x 12 in. (30.0 x 50.8 x 30.0 cm) Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, New Jersey Museum purchase, acquisition fund, 2015.12a, b Photo: Peter Jacobs

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School. Photographic source: Thompson Photo Co. Poughkeepsie, NY, Carlisle Indian School Student Body, 1912. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Educational Genocide illustrates the impact that boarding schools continue to have on Native people today. The exterior features a photograph of students at the school and Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, save the man,” speech. The red interior (lid and base) weaves names from the list of more than 8,000 children who attended the Carlisle Indian School from 1879 to 1918. During my research, I found the names of two of my great-grandparents.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 15 x 8 ½ x 8 ½ in. (38.1 x 21.6 x 21.6 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Eye-of-the-SacredBird pattern.

Inscriptions: (red splints) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; (white and blue splints) lyrics to “Ten Little Injuns.”

This basket combines two documents: the names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School and lyrics to Septimus Winner’s song “Ten Little Injuns.” Written in 1869, these hostile lyrics include: “one got executed and then there were nine, one got syphilis and then there were eight, one chopped himself in half and then there were seven, one broke his neck and then there were six, one dead drunk and then there were three, one passed out drunk and then there were two, one shot himself and then there was one, he went and hanged himself and then there were none.” The original lyrics were written as a way for children to learn how to count, giving an indication of the American sentiment toward Native children. This Cherokee pattern, called Eye-of-the-Sacred-Bird, was deliberately woven in red, white, and blue to suggest the stars-and-stripes and even the eye of the emblematic eagle. This basket questions the heinous impact these assimilation experiments, and thus American policy, have had on the collective psyche of generations of Native people.

Archival ink on frosted vellum, x-rays (silver on polyester film), polyester sinew 10 ½ x 11 x 7 ½ in. (26.7 x 27.9 x 19.1 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Mountain pattern; coffin shape.

Inscriptions: names of students buried in the Carlisle Indian School cemetery.

Photographic source: x-rays.

While reviewing files and documents in the Cumberland County Historical Society’s library, I learned many heartbreaking stories about these children. One young woman from my tribe was bedfast in the hospital for a year before she died. I had to wonder if her parents knew and if they were given the option to participate in her healing. Another young man made a conscious and fatal decision after he was “confiscated” from a train while trying to depart with other members of his tribe; the school would not allow the boy’s release along with his cousins because the staff denied his uncle’s authority to claim him. In protest, this child refused all food until he escaped from the school in the only manner left to him. My heart aches for every single one of these children who were separated from the only family and culture they knew and thrown into an alien society that was so at odds with their upbringing.

This basket is woven of splints created from x-rays and frosted vellum paper. Under normal lighting, the Cherokee basket pattern of Mountains is evident, linking these children with their homelands. However, when the LED lights (inside the basket) are turned on, the x-rays reveal images of bones, referencing human remains. This imagery is integrated with the names of students buried in the school cemetery, handwritten on the vellum. The shape of the basket is also a familiar Cherokee one called the “coffin” shape.

The title was inspired by a Kiowa Black Leggings Society Dance that memorialized warriors from battles since the Korean War. The emcee recited all the names of warriors who had given their life in battle since the Korean War, also commenting for each that s/he “would forever be eighteen years old” (or their age when they died). It was a beautifully moving ceremony. While studying the Carlisle cemetery logs, I was struck that these children will forever be remembered by their age at their death. Many Indian people consider this school to be the result of a war crime, thus making the children prisoners of war. It does not seem a stretch at all to afford these deceased children with the same honor as the Kiowa warriors.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ½ x 4 ¼ x 4 ¼ in. (29.2 x 10.8 x 10.8 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; variation on the Unbroken Friendship pattern.

Inscriptions: eight treaties between the US Government and a number of Native nations; (blue splints) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Loss integrates names from the Carlisle Indian School official student roster and text from eight different treaties between the US government and a vast sampling of Native nations. They are identified in woven order from top to bottom (two are duplicated): Horse Creek, Canandaigua, Medicine Lodge, California, Navajo, Muscogee, New Echota, Medicine Lodge, Canandaigua, and Fort Wayne. Generally speaking, these treaties resulted in major land loss and relocation for Indian people. The pattern is a variation of a traditional Cherokee one called Unbroken Friendship. I chose it to illustrate how closely these government-sanctioned policies were used to eliminate the first people of this country.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ½ x 4 x 4 in. (29.2 cm x 10.2 x 10.2) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: names of Cherokee students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

The title Roll Call refers to having your name called to indicate physical presence, typically in a school setting. The response to such a call would be “here” or “present.” Unfortunately, this would be counterintuitive to the institutionalized instruction of Native children, which hindered their ability to have a voice and to have a sense of place. After being sequestered at these institutions for years, Native children left these schools with the conflicted feeling of not belonging to either white society or their own tribal culture—they were literally silenced in both worlds. The weave for this basket is my first prototype to create a twist unique to a DNA strand.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 8 x 7 ¼ x 7 ¼ in. (20.3 x 18.4 x 18.4 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: single weave.

Inscriptions: Medicine Lodge Treaty; names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; prayers in three tribal languages and one in Hebrew; lyrics to “We remember your sacrifices. You will not be forgotten;” Raphael Lemkin's definition of genocide.

Genocide. It is an ugly word that sums up the most inhumane of actions. And it is rarely associated with the atrocities that happened in the United States.

Raphael Lemkim, a Polish attorney of Jewish descent who escaped Nazi Germany, coined the term genocide from genos- (Greek: family, tribe, race) and –cide (Latin: killing). His definition identified eight essential actions, which ranged from attacks on the social, cultural, economic, biological, physical (subcategories here include endangering health and mass killing), religious, and moral characteristics of a people. Lempkin’s definition is woven into the interior of this basket.

US government policy and actions against the American Indian horrifically achieved each of these points. Massacres are remembered as battles where women,children, and unarmed men were oftentimes killed at the hands of the military. Native communities and towns were annihilated and tribes were starved while sequestered in forts. There was also a systematic cleansing of culture through the denial of language, religion, and citizenship. In this basket, two documents support this claim: the Medicine Lodge Treaty (reflecting land loss and displacement) and the names of children from the Carlisle Indian School student roster (reflecting the removal of children from their homes and teaching them government-approved ideas). These texts are woven into the basket with prayers—including one asking for healing and peace of mind—in three tribal languages and one in Hebrew. Also included is the Cherokee Memorial Song “We remember your sacrifices. You will not be forgotten.” The bright colors and X-pattern serve as a naval warning flag. If the events of the past are not truthfully remembered and taught to our children, they can easily happen again.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ¼ x 7 ¾ x 8 in. (28.6 x 19.7 x 20.3 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: Raphael Lemkin’s definition of genocide; the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Medicine Lodge Treaty; names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Shrouded in Grey combines the texts of Raphael Lemkin’s definition of genocide (see cat. 13) with three documents that support this claim: the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Medicine Lodge Treaty, and names of children on the Carlisle Indian School student roster. The title references the burial shroud, serving as a testament to the extraordinary number of lives lost as a result of military murders. It also speaks to the fact that this is a clearcut issue not to be clouded in political rhetoric. There can be no argument that there was a genocide in this country as surely as there was one in Europe. We cannot turn a blind eye to the fact that other indigenous people around the world are still suffering from these forms of persecution. True healing cannot take place until these atrocities are openly acknowledged.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 10 x 9 ½ x 9 ½ in. (25.4 x 24.1 x 24.1 cm) Kim Niven Collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; list of commodities with Indian names; statistics of domestic abuse directed at Indian women. Photographic sources: Thompson Photo Co. Poughkeepsie, NY, Carlisle Indian School Student Body, Carlisle, Pa., 1912. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; bottles of alcohol.

This basket weaves together Pratt’s infamous speech, the names of commercial products that use Indian names and images, the disproportionately high statistics of domestic abuse directed at Indian women, and photographs of bottles of alcohol. The title—Civilization—is tongue-in-cheek; all of these elements introduced by the dominant white culture contributed to detrimental changes for Native people, who moved from a traditional society into the one we experience today.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper Corn: 9 x 5 x 5 in. (22.9 x 12.7 x 12.7cm) Beans: 7 x 7 x 7 in. (17.8 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm) Squash: 6 x 9 x 9 in. (15.3 x 22.3 x 22.3 cm) Brenda Toineeta and Wilson Pipestem Collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

Photographic sources: corn, beans, squash (at Kituwah Mound).

This set of baskets features photographs of corn, squash, and beans. These three vegetables were traditionally grown together in a symbiotic relationship; not only did the beans cling to the upright stalks of the corn, but this planting combination enriched the soil more than three times that of the individual plants. To further illustrate this relationship, these are nesting baskets.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 2 x 1 ½ x 1 ½ in. (5.1 x 3.8 x 3.8 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Chain pattern.

Inscriptions: statistics representing injustice experienced by Native women today; Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

This miniature basket is woven with a Chain pattern, representing a link between the assimilation experiment of Indian boarding schools in the late nineteenth century and the pervasive violence experienced by Native women today. The boarding schools stripped Natives of their culture, language, and families. Americans perceived Natives as less than potential citizens and, at best, a glorified labor force. This sort of ideology, of Natives being objectified and undeserving of respect, continues today, evidenced by the high rate of violence directed by non-Native men toward Native women and by the number of Native women who are assaulted, raped, murdered, or missing at rates starkly higher than non-Native women. Rarely are the perpetrators prosecuted or brought before a court of law. Woven into this basket are statistics representing this particular injustice experienced by Native women and Richard H. Pratt’s infamous speech.

18. Lure, 2017

Archival inks, acrylic paint, silver leaf on paper, polyester sinew 4 ½ x 1 ¾ x 1 ¼ in. (11.4 x 4.4 x 3.2 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee fishing basket shape.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

I wove this piece in the shape of a traditional Cherokee fishing basket; the diminutive size and light-reflective colors mimic a fishing lure. It alludes to how children were lured and sometimes forced to the Carlisle Indian School and similar institutions, in ways that were unethical and cruel. In some instances, critical government rations were withheld from tribes until family members relinquished their children to school agents. In others, military police were dispatched to intimidate families into releasing their children. These tactics were devastatingly successful in removing children from their reservations and placing them into white society. In the thirty-nine years that Carlisle was in existence, more than 8,000 Native students were enrolled and taught that their language, customs, and spiritual beliefs were wrong and needed to be replaced.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, artificial sinew 2 ¾ x 2 ½ x 2 ½ in. (7 x 6.4 x 6.4 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: (rust splints) Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech; (brown splints) list of commodities with Indian names.

This basket interweaves the text of Pratt’s famous assimilationist speech and a list of commercial products that exploit Native culture. Together, they show an equal amount of disdain for Native people. The very culture the US government strove to eliminate is now being bastardized as a source of advertising gimmicks. Despite being living, breathing human beings, indigenous people and their traditional ways have, from the very beginning, been devalued and dehumanized in the United States.

20. Red to White, 2017

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper Size: 3 x 2 ¼ x 2 ¼ in. (7.6 x 5.7 x 5.7 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave; Cross-on-a-Hill pattern.

Inscriptions: (red splints) names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; (white splints) Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

One tactic used in the overall mission to eradicate Native culture was the removal and replacement of children’s names. Names—often having a historic link to family lineage—were anglicized upon their arrival to the schools. The children were sometimes given a choice to pick a name from a blackboard list, without first hearing it pronounced. This new name, having no connection to family, clan, or tribe, would then be inherited by all following generations.

Woven in a red Cross-on-a-Hill Cherokee pattern are the names of children listed on the Carlisle Indian School student roster. Woven in white is the speech of Captain Richard H. Pratt, founder of Carlisle, in which he describes his vision for the school—essentially a vision to replace a red culture with a white one.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 3 x 2 x 2 in. (7.6 x 5.1 5.1 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School; boarding school memoir of the artist’s great-grandmother.

This basket integrates the names of students at the Carlisle Indian School with words from the boarding school memoir of Stacy Saunooke, my great-grandmother. It took years for her to share her story. Recounting the chores all the children were required to perform and the way she personally was reprimanded for helping a new arrival by explaining a foreign procedure in Cherokee (the first language to both girls), my great-grandmother’s account is priceless to our people. The aqua and emerald gem-like colors of this basket represent the precious value of my great-grandmother and all the children who were acculturated in these schools. Much like the time-tested strength of gems, the fortitude these students demonstrated, despite extreme hardship, is a testament to their resilience.

22. Decline, Challenged, 2014

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 6 x 3 x 3 in. (15.2 x 7.6 x 7.6 cm) David and Sue Halpern Collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee single weave.

Inscriptions: names of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School.

Photographic source: historical map showing the decrease of Cherokee lands.

This small basket combines names from the more than 8,000 children on the Carlisle Indian School student roster with a historical map showing the decrease of Cherokee lands due to colonization. Just like the borders of the original homelands, the names on the exterior are fading, illustrating the mission of boarding schools to erase Native culture. The interior names are washed a deep red to illustrate the inherent, core beliefs of Native people and our objective to maintain our identity despite the fact that others have repeatedly tried to strip them from us.

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 3 x 3 x 3 in. (7.6 x 7.6 x 7.6 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: Cherokee burden basket shape.

Inscriptions: Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

This is the artist’s first attempt at weaving a Cherokee burden basket. Regarding Pratt’s quote, burdens don’t get any heavier than that.

24. Forever a Part of Us, 2012

Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 1 ½ x 2 ¾ x 1 ½ in. (3.8 x 7.0 x 4.4 cm) Artist’s collection

Weaving technique: double-weave.

Inscriptions: text from Richard H. Pratt’s “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man” speech.

Photographic source: Carlisle Indian School student rosters, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian, Washington, DC.

Exhibition Checklist

Large Baskets Medium Baskets

All dimensions are listed as height by width by depth. Two Views, 2018 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 14 ¼ x 13 ½ x 13 ½ (36.2 x 34.3 x 34.3 cm) The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA Purchased with funds from the Friends of The Trout Gallery, 2018.12

Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence, 2017 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Seven pairs of baskets; each: 21 ½ x 6 ½ x 6 ½ in. (54.6 x 16.5 x 16.5 cm) Artist’s collection

The Fire Within, 2016 Archival inks, acrylic paint, and copper foil on paper, polyester sinew 19 ½ x 15 x 15 in. (49.5 x 38.1 x 38.1 cm) Artist’s collection

Swept Away, 2016 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 15 x 30 x 11 in. (38.1 x 76.2 x 27.9 cm) Artist’s collection

Prayers for Our Children, 2015 20 ½ x 11 ¼ x 11 ¼ in. (52.1 x 28.6 x 28.6 cm) Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew Sam Wertheimer and Pamela Rosenthal Collection

Unexpected Gift, 2015 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 16 ½ x 10 x 10 in. (41.9 x 25.4 x 24.4 cm) Artist’s collection Red, White and Blue, 2017 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 15 x 8 ½ x 8 ½ in. (38.1 x 21.6 x 21.6 cm) Artist’s collection

Remaining a Child, 2017 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 10 ½ x 11 x 7 ½ in. (26.7 x 27.9 x 19.1 cm) Artist’s collection

Loss, 2016 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ½ x 4 ½ x 4 ¼ in. (29.2 x 10.8 x 10.7 cm) Artist’s collection

Roll Call, 2016 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ½ x 4 x 4 in. (29.2 x 10.2 x 10.2 cm) Artist’s collection

Red Flag, 2015 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 8 x 7 ¼ x 7 ¼ in. (20.3 x 18.4 x 18.4 cm) Artist’s collection

Shrouded in Grey, 2015 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 11 ¼ x 7 ¾ x 8 in. (28.6 x 19.7 x 20.3 cm) Artist’s collection

Civilization, 2013 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper 10 x 9 ¼ x 9 ¼ in. (25.4 x 24.1 x 24.1 cm) Kim Niven Collection

Despite (a.k.a. Three Sisters), 2012 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper Corn: 9 x 5 x 5 in. (22.9 x 12.7 x 12.7 cm) Beans: 7 x 7 x 7 in. (17.8 x 17.8 x 17.8 cm) Squash: 6 x 9 x 9 in. (15.3 x 22.3 x 22.3 cm) Brenda Toineeta and Wilson Pipestem Collection

Unsolicited Gifts, or How to Eliminate a Culture, 2012 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 7 x 16 x 11 in. (17.8 x 40.1 x 27.9 cm) Lambert Wilson Collection

Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, 2011 Archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew 12 x 20 x 12 in. (30.0 x 50.8 x 30.0 cm) Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ Museum purchase, acquisition fund, 2015.12a, b