27 minute read

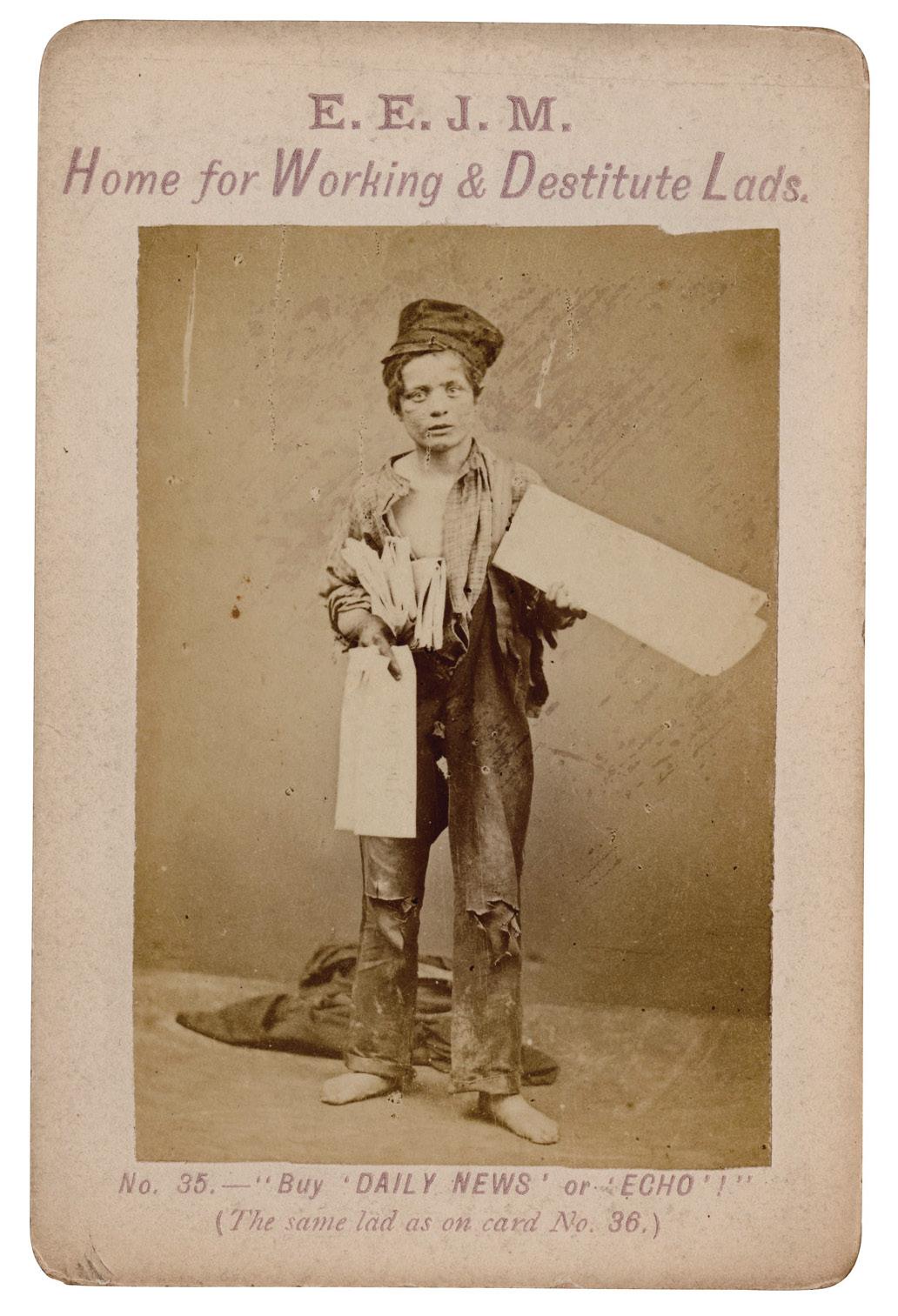

Shan Goshorn’s Resisting the Mission and the Origins of Before-and-After Photographs at the Carlisle Indian School

Shan Goshorn’s Resisting the Mission and the origins of Before-and-After Photographs at the Carlisle Indian School1

Phillip Earenfight

“A photograph is a meeting place where the interests of the photographer, the photographed, the viewer and those who are using the photograph are often contradictory. These contradictions both hide and increase then natural ambiguity of the photographic image.”2

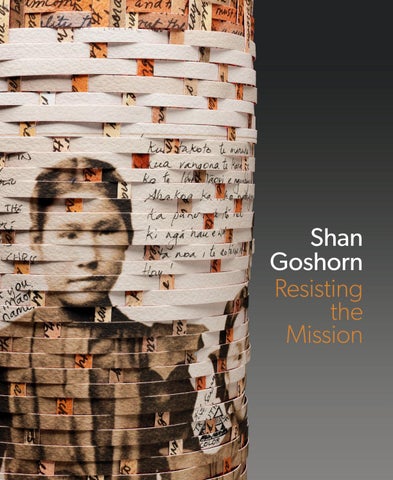

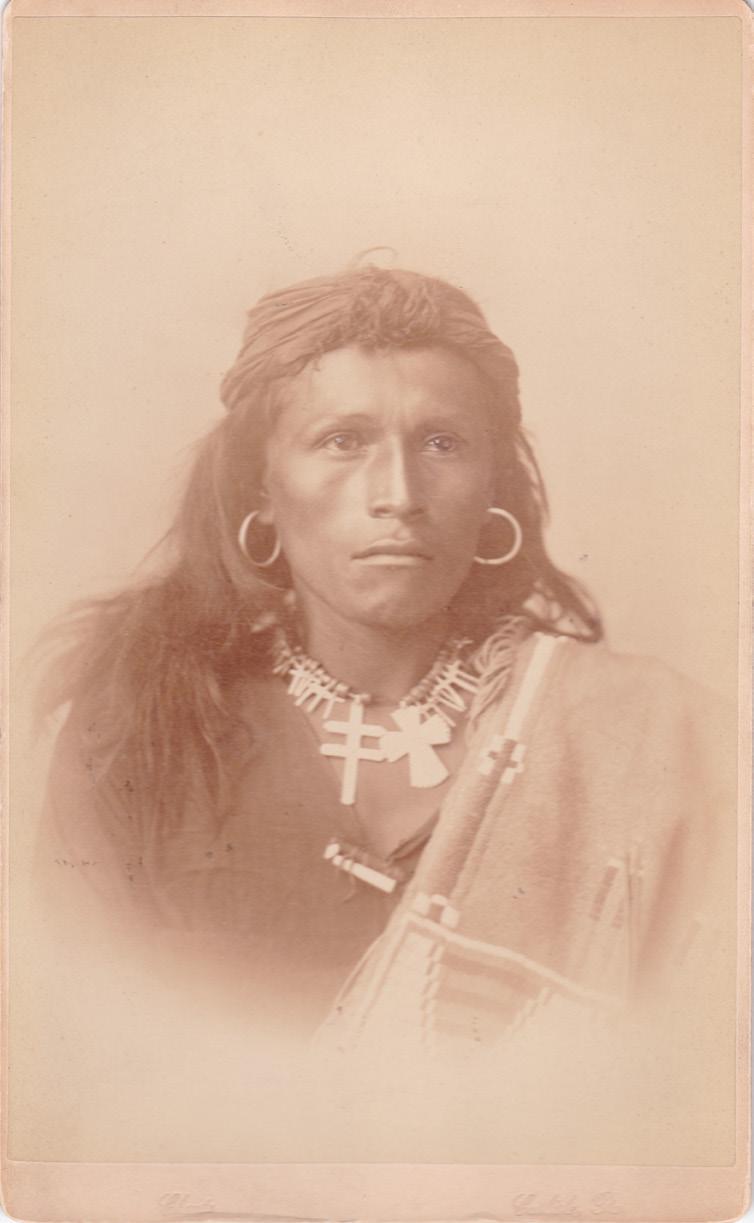

The compelling imagery that Shan Goshorn has woven into the pairs of baskets that comprise Resisting the Mission: Filling the Silence are enlarged versions of vintage before-and-after photographs made of students who attended the Carlisle Indian School (fig. 1).3 These photographs show selections of the Indian students—Alaskan, Apache, Navajo, Pueblo, Sioux—upon their arrival at the Carlisle Indian School (before) and several months later (after) (figs. 2, 3). They were made by John N. Choate, a prominent local photographer in the small town of Carlisle, Pennsylvania, during the last decades of the nineteenth and the early twentieth century.4 The before-and-after pairs of photographs were conceived and staged by the founding superintendent of the Carlisle Indian School, Richard Henry Pratt, who commissioned them, in part, to demonstrate what he regarded as the efficacy of assimilationist practices at the first and most

1. Shan Goshorn, Three Sioux Students from Mission Resisted: Filling the Silence, 2017. One of seven pairs of baskets: archival ink and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew. Artist’s collection.

2. John N. Choate, Wounded Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear, Timber Yellow Robe; Upon Their Arrival in Carlisle, n. d., Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Carlisle Indian School, PC 2002.2, folder 6.

3. John N. Choate, Wounded Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear, Timber Yellow Robe; 6 Months after Entrance to the School, n. d., Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Carlisle Indian School, PC 2002.2, folder 7.

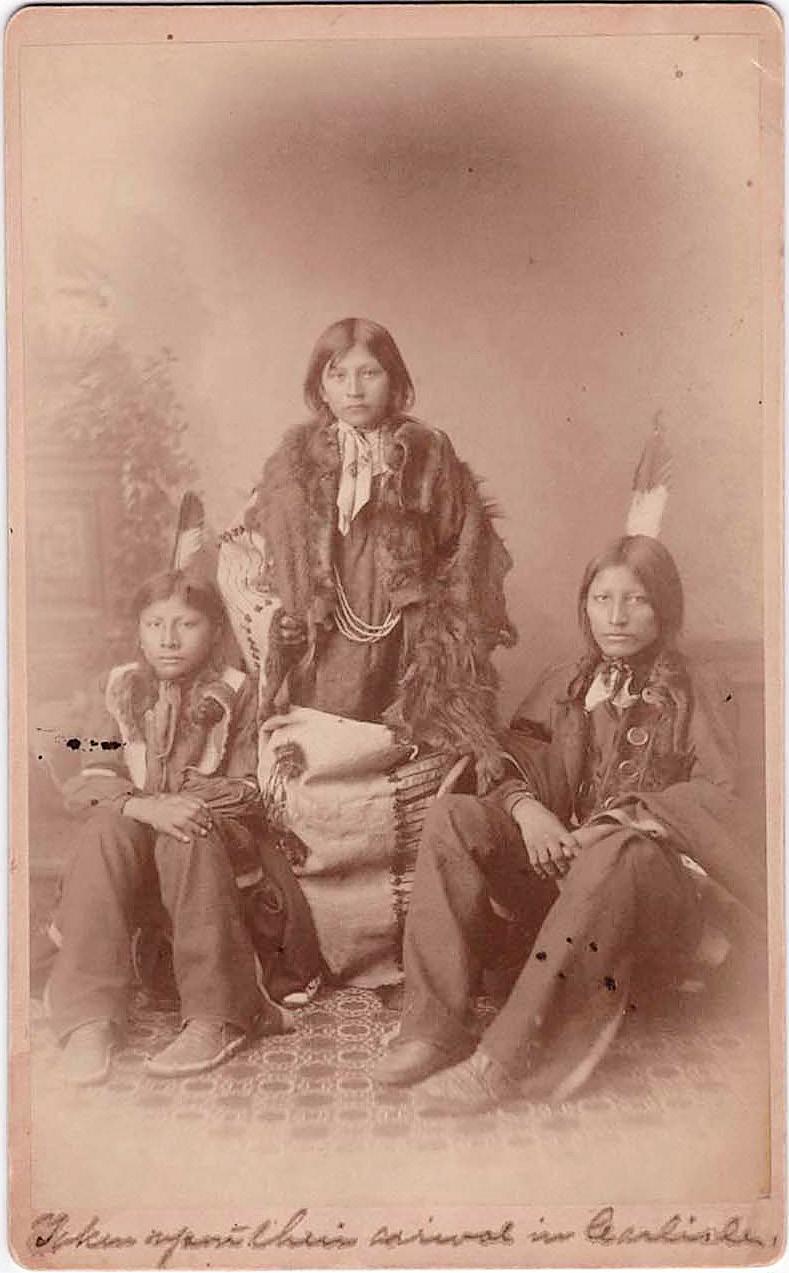

4. Mathew Brady Studio, Gordon, 1863. Albumen print on card. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, NPG.2002.89. influential of the nation’s off-reservation boarding schools. According to Pratt, Choate’s beforeand-after photographs offered indisputable, visual proof that his school was physically—and by not so subtle implication—culturally transforming “blanket” Indians (to use Pratt’s term) into “civilized” members of white society.5 The paired photographs are well known among scholars and archivists of the Carlisle Indian School and, more broadly, of those who study and follow matters associated with Native Americans. Indeed, the paired photographs are, perhaps, the most widely recognized images, dare one say, icons, of the school and its mission. The photographs, however, are more than documents of a mission. They, like the photographs of former Black slaves, which display the marks of brutal torture at the hands of their owners, bear witness to the systematic abuse of minority ethnic populations by dominant whites (fig. 4).6 In the case of the tortured slave photographs, a “before” image is unnecessary; one can easily visualize the skin smooth and even, prior to the scars. However, unlike the photographs of mutilated slaves, where evidence of hate stands visible as many and deep scars, Choate’s formal portraits of the Indians present an air of late-Victorian pleasantness. The damage to the person is not immediately apparent. And some viewers see no damage, only improvement. In these images, the destructive effects are subtler; the photographs more pernicious. While few could fail to recoil at the sight a of a deeply scarred physical body, it requires imagination and empathy to visualize the scarring of one’s cultural identity, particularly in images that appear so refined and adhere faithfully to the portrait conventions of the day. In selecting Choate’s before-and-after photographs as the focus for Resisting the Mission, Goshorn seized on imagery that emerged during a pivotal moment in US history, when matters of cultural assimilation, photography, evidence-based science, and advertising intersected in significant and, at times, nefarious ways. Although Pratt’s work with Choate in creating beforeand-after photographs at the Carlisle Indian School is well documented and published, the story of how Pratt arrived at using paired photographs—initially at St. Augustine and then at the Hampton Normal Agricultural Institute in Virginia—to demonstrate the acculturation of Indians has received little scholarly attention.7 By considering these earlier practices, one gains a broader picture of this material and the place of Resisting the Mission within it.

Before-and-After Imagery Prior to Pratt The practice of using images to document and promote change over time emerged during the Industrial Revolution, enabled by the development of larg-scale printing operations and the advent of modern print advertising. Indeed, the last quarter of the nineteenth century witnessed the weaving together of various strands of imagery, art, science, colonialism, capitalism, and notions of civilization and citizenship that led to the emergence of before-and-after imagery. And just as photography has two simultaneous points of origin (Paris and London), so too, the surviving evidence suggests that the earliest before-and-after images appeared in England and the United States at the same time, cultivated by similar cultural forces. Among the earliest known uses of photographs to document and promote acculturation appears in the before-and-after photographs made during the US Civil War of “Taylor” or “Contraband Jackson,” a young runaway slave who became a Union drummer in the 78th Infantry Regiment, US Colored Troops (figs. 5, 6). As James Brookes notes:

In slavery, the boy appears in rags and tatters, his body exposed and with no props to symbolise his social worth. In the second image he stands as a drummer in formal military dress, wearing a frock coat and white gloves. The instrument, a martial symbol of organisation and of keeping

time, provides evidence that he was able to rise from the oppression of slavery to the position of one who would beat the step that the Union Army marched to in its destruction of the South’s slave society in the last years of the war.8

The pair of photographs were used by abolitionists to demonstrate the uplifting and civilizing influence that military service could have on African Americans, transforming them from penniless slaves to men of rank and status. Such service and self-sacrifice to the country were touted as a means towards enlightenment, emancipation, citizenship, and assimilation.9 The photographs provided tangible evidence to Frederick Douglass’s argument:

Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S., let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.10

Here, photography provided the weight of seemingly unbiased documentation of such service. As Susan Sontag later observed, “[a] photograph passes for incontrovertible proof that a given thing happened.”11 Although the photographs of the Union drummer seem stiff and staged to modern eyes made cynical by the ease of digital manipulation, one must consider the power of such imagery at this time. In an age when photography was new, trust in its veracity was high, and its potential to sway opinion was at its peak, it is difficult to overestimate the persuasive power of the medium. A second example of photographic before-and-after images are the those made for Dr. Thomas John Barnardo, an Irish philanthropist and founder of homes for poor children in the East End of London.12 To promote the efficacy of his institutions and raise charitable funds,

5. Photographer unknown, Taylor [aka Jackson], young drummer boy for 78th Colored Troops Infantry, in rags, 1864–1865. Albumen print on card. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

6. Photographer unknown, Taylor [aka Jackson], young drummer boy for 78th Colored Troops Infantry, in uniform with drum, 1864–1865. Albumen print on card. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, DC.

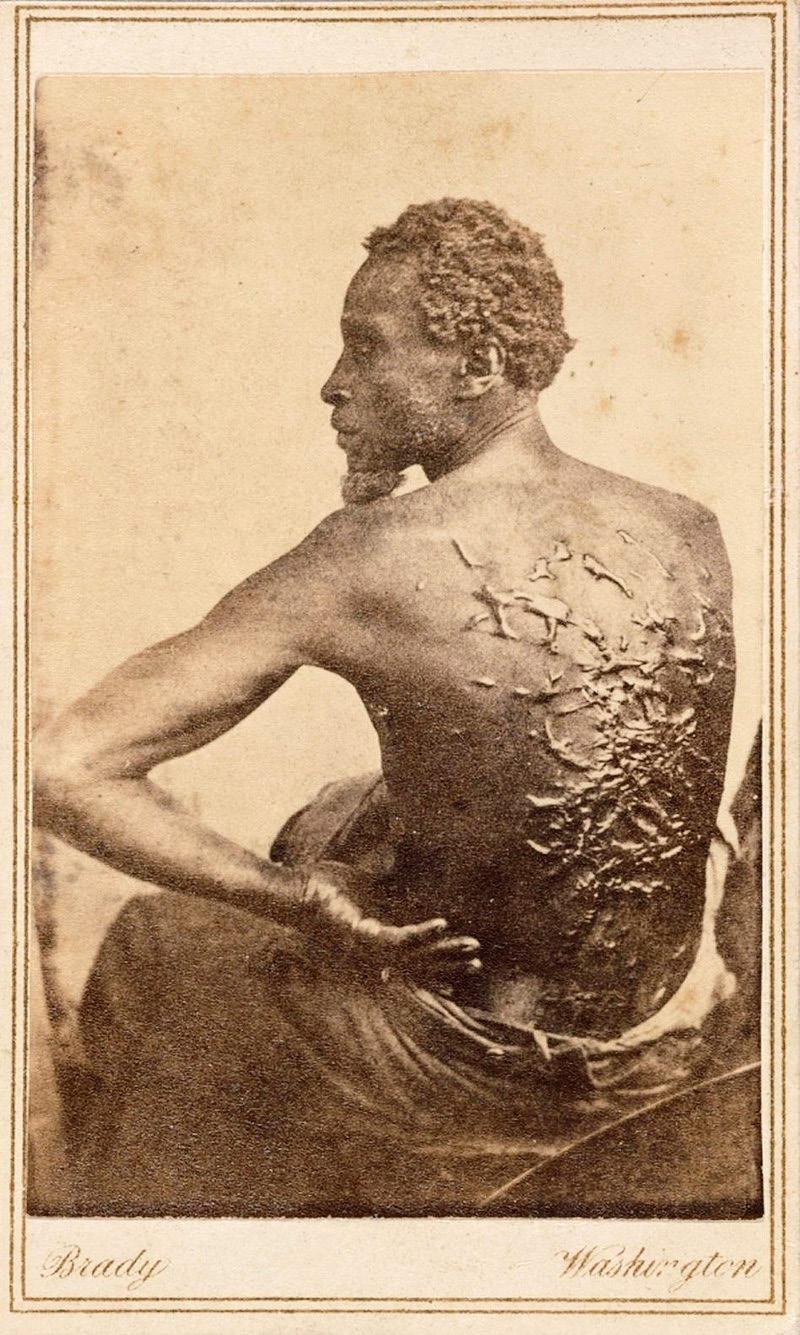

7. Thomas John Barnes, E.E.J.M. Home for Working & Destitute Lads. No. 35. “Buy ‘Daily News’ or ‘Echo’!” (The same lad as on card No. 36.), from Barnardo Before and After Picture, c.1872. Albumen silver print cabinet card. Barnardo’s Photographic Archive, London. Photo © Barnardo’s Photographic Archive.

8. Thomas John Barnes, E.E.J.M. Home for Working & Destitute Lads. No. 36. “Going to Sunday School,” from Barnardo Before and After Picture, c.1872. Albumen silver print cabinet card. Barnardo’s Photographic Archive, London. Photo © Barnardo’s Photographic Archive.

Bernardo commissioned a series of before-and-after images—which he called “contrasts”—to illustrate the transformation of destitute street children into healthy youths of promise under his care (figs. 7, 8). He produced tens of thousands of the mounted photographs, which he sold or gave away. In one instance, he claims to have used the “contrasts” to convince a would-be child prostitute named Bridget to enter his care. Ever the promoter, Barnardo exceeded the bounds of British credulity and, in July 1877, he was accused by rival philanthropic organizations in court for staging his photographs and enriching himself on the charitable donations they inspired. As part of the attack on Banardo, George Reynolds, an evangelical Baptist minister, self-published a pamphlet entitled “Dr. Barnardo’s Homes: Startling Revelations,” where he alleged that Barnardo, in an effort to exaggerate the contrast that appears in the paired photographs, “tears their clothes, so as to make them appear worse than they really are. A lad named Fletcher is taken with a shoeblack’s box upon his back, although he never was a shoeblack.”13 Pressed with the truth, Barnardo admitted to artistic license: “we are often compelled to seize the most favorable opportunities of fine weather, and the reception of some boy or girl of a less destitute class whose expression of face, form, and general carriage may, if aided by suitable additions or subtractions of clothing ... convey a truthful picture ... of the class of children received in unfavourable weather, whom we could not ... photograph immediately.”14 Ultimately, the court of arbitration cleared Barnardo of wrongdoing. While his accusers were motivated in part by the considerable amount of charitable funds his scheme attracted, the case was pivotal in the history of photography because it further undercut Victorian notions of the photographic image and its veracity. More significant for this study, however, is that a “deliberately manipulated photograph of a child was considered not just an assault on notions of representational truth, but an assault on the innocence of the child itself.”15 A final example of before-and-after imagery dates from the 1890s, which is well into the period when the Carlisle Indian School was in operation. Although made in the wake of Pratt’s before-and-after photographs, it provides a valuable insight into the age and the moral depravity

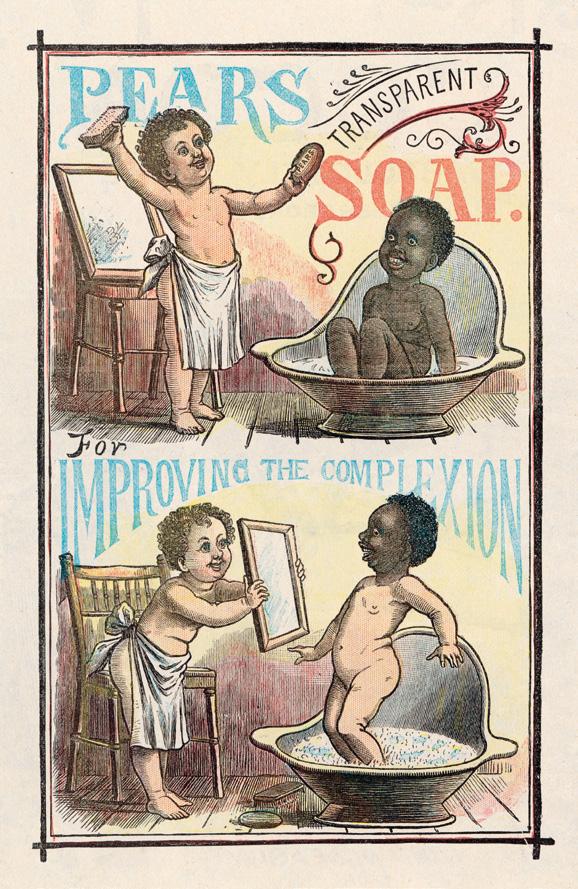

to which such promotional efforts could descend. It concerns the work of Thomas James Barratt, the chairman of A&F Pears and “father of modern advertising,” who played a key role in England in using the before-and-after concept in drawing together marketing, colonialism, and capitalism. In a series of racist ads from the 1890s for Pear’s Soap (fig. 9), the company produced two-panel before-and-after designs. The first features a white child presenting a black child with soap, brush, and a basin of water. In the subsequent panel, the black child, “after” using the soap, appears gleaming white from the neck down, demonstrating the astonishing effect of the soap’s “cleaning” ability. The promotional text reads: “Pear’s Transparent Soap. For Improving the Complexion.” This ad visualizes in the most insulting, literal terms the effects of “enlightenment.” Produced at the height of colonization, when expansionist greed brought the world’s powers into increasing contact and conflict with indigenous peoples, the before-and-after advertisement linked Pears Soap with British imperial culture, enlightenment thought, a growing obsession with hygiene, global marketing, and the country’s self-styled civilizing mission.16 While there is no evidence to indicate that Richard Henry Pratt knew anything of these specific examples (although his experience in the Civil War and the sheer volume of Barnardo’s photos leads one to speculate as much), the use of photographs and prints to demonstrate change through a pair of before-and-after images was an increasing popular rhetorical device in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Thus, consistent with the promotional activities of his day, Pratt, in an effort to promote his self-fashioned approach to assimilating the Native Americans, visualized the results of these efforts through before-and-after photographs, first at St. Augustine, then clarifying the practice at the Hampton Institute, and finally expanding and codifying it at Carlisle.

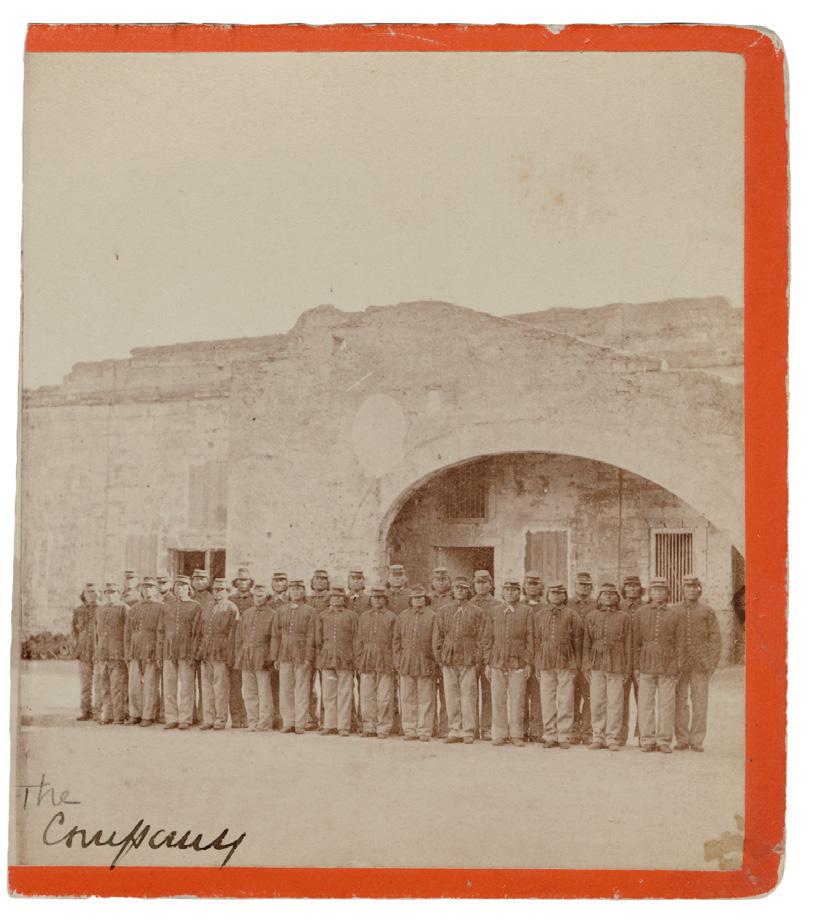

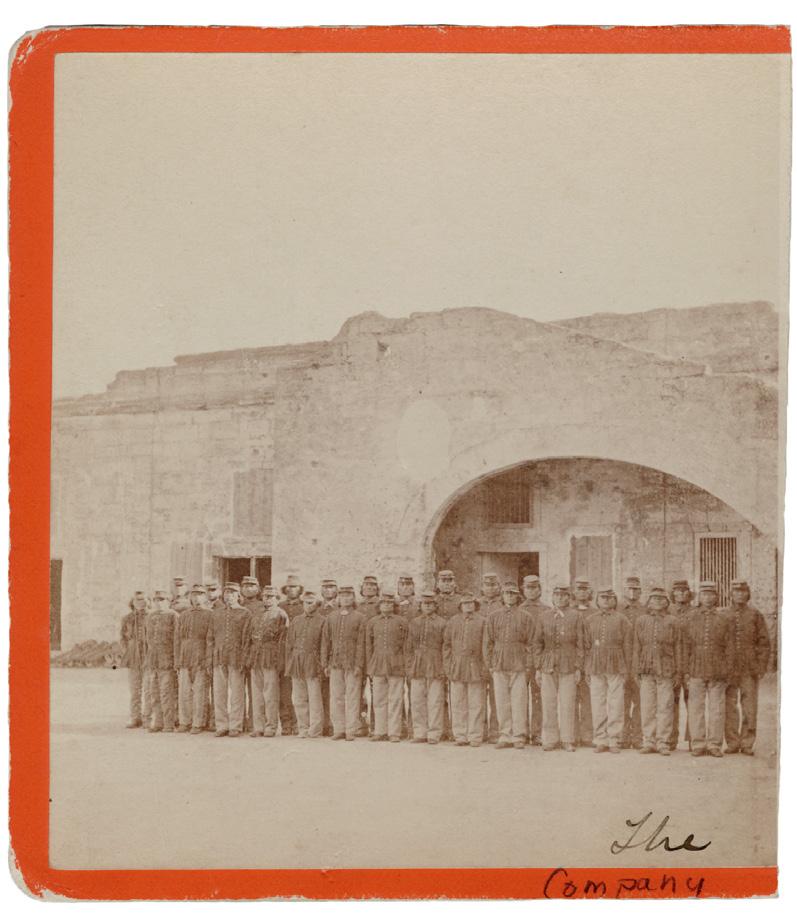

Before-and-After Photographs at Fort Marion and Hampton (1875–1879) Pratt’s first efforts at assimilating Native Americans and documenting such practices began with a rather humble assignment. In 1875, Pratt was selected to escort and supervise seventy-two Indian prisoners of war from Fort Sill, Indian Territory (later, Oklahoma) to Fort Marion in St. Augustine, where they were to be incarcerated until conflict with white settlers on the Plains subsided.17 Despite his detailed account of the twenty-four day passage from the Plains to the coast, Pratt makes no mention of plans to photograph the Indians upon arrival at Fort Marion, and nothing of his plans to transform—without the approval of his commanding officer—a routine transport/prison detail into an experiment in forced acculturation.18 Nevertheless, shortly after they arrived at the old Spanish fort, Pratt and the town’s local photographer (probably George Pierron), arranged to take photographs of the Indians (fig. 10).19 After the photo session, Pratt began his assimilationist experiment: stripping the Indians of their language, clothes, customs; cutting their hair; and reforming them as Western-thinking, English-speaking military cadets. Whether the immediate and obvious physical change (haircut and uniforms) prompted another round of photographs, thereby setting in motion the first before-and-after images of the Indians at the fort, it is not known. Regardless, Pratt had photos taken of the Indians in uniform over the course of the next three years. In one example, among the many preserved in Pratt’s papers at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library of Yale University (fig. 11), two rows of uniformed soldiers stand at attention in the fort’s courtyard, along the arched stairway that leads up to the elevated terreplein. Their consistent dress and comportment belies the differences in language, identity, allegiances, and beliefs that lay below the veneer of martial order. Commissioning such photographs (and selling them to the city’s tourist population) were periodic occurrences at the fort, evident by the more than fifty negatives known to have been made at the site.

9. Pear’s Soap Advertisement, c. 1890s, color lithograph. Photo courtesy ALAMY stock photos.

10. Photographer Unknown, Indian Prisoners upon Arrival at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida, 1875. Albumen print, Richard Henry Pratt Papers, WA MSS S-1174, box 23a, folder 745. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

11. Photographer unknown, A Group of Plains Indian Prisoners of War in Military Uniform Assembled in Courtyard, Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida, c. 1875–1878. Albumen prints mounted on a stereo view card. Richard Henry Pratt Collection, MSS S-1174, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut.

While the Plains Indians were, by the late nineteenth century, increasingly familiar with the practice of photography, which they would have encountered on occasion at the reservations and forts on the Plains, being the subject of tourist photographs that were bought and sold in St. Augustine must have been a novel experience. Indeed, the practice was curious enough for Making Medicine, a Cheyenne warrior held captive at the fort, to create a marvelous drawing from a uniquely Indian perspective that illustrates Pratt and his staff photographing Indians (fig. 12). Indeed, it captures a scene almost identical to the stereograph describes above. From a bird’s-eye-view, the drawing presents the perimeter wall of the court yard and the uniformed Indians at attention, with the photographer, Pratt, and George Fox (his interpreter) opposite the Indians, directing the scene. Unlike the stereograph, which shows only the perspective of the photographer’s gaze through the camera’s lenses, Making Medicine’s drawing shows all parties equally, from a third-person point of view. Seen in light of this drawing, the photographs made

under Pratt’s authority at the fort appear entirely one-sided, intrusive, peering, and subject to the gaze of those in control. Perhaps it was the knowledge of other before-and-after images he might have seen, or simply the sight of the photographs made of the Indians upon arrival at the fort and later, that led Pratt to see their value as persuasive evidence to prove the efficacy of his assimilationist experiment. Regardless of what stirred his thoughts, by 1878, when the US government permitted the Indians to return to the Plains, it is certain that Pratt was aware of before-and-after imagery and of its potential. This is confirmed by a trompe-l’œil illustration in the New York Daily Graphic (which is based on photographs and drawings made at the fort) that shows a “before” and an “after” drawing of the Indians tacked to either side of the central, circular image —the first, on the Plains in their own clothes, and the second, at Fort Marion in military-issue uniforms (fig. 13).20 The two drawings are labeled “Past” and “Present” respectively. Upon releasing the prisoners of war from Fort Marion in 1878, seventeen of the surviving sixty-three stayed with Pratt, who took them to the Hampton Institute, where they joined recently freed slaves to further their Western education and assimilation.21 At Hampton, Pratt worked with Samuel Chapman Armstrong to develop a biracial, segregated educational environment. Not long after Pratt’s arrival, the subject of photographs emerged. In a letter that Armstrong sent to Pratt, who was in Nebraska on an admissions tour at the time, he urges: “We wish a variety of photographs of the Indians. Be sure and have them bring their wild barbarous things. This will show whence we started.”22 While Armstrong’s request seems to suggest that the concept of before-and-after photographs might have been new to Pratt, which would be unusual in light of the proceeding discussion, perhaps it was meant as a reminder of what Pratt was already well acquainted, rather than the introduction of a new idea. Whether such photographs were made is uncertain; none have been identified with this request from Armstrong. That said, by the time Pratt parts company with Armstrong the following year to accept the superintendent

13. Scenes at the Fort. The Indian Prisoners Released from Fort Marion, Florida, Daily New York Graphic, April 26, 1878.

12. Making Medicine, Indian Prisoners at Fort Marion Being Photographed, c. 1875–1878. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, MS-39B.

14. John N. Choate, Back of photographic card from Choat’s studio, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Carlisle Indian School, folder 12. position at the newly created Carlisle Indian School, he left for Pennsylvania with a firm command of before-and-after imagery and how it can be used to visualize and promote the mission of acculturation at the school. Thus, by the time he met Choate at his studio on 21 West Main (High) Street, he had a clear idea of what he would like the photographer to do. Once in Carlisle, Pratt put Choate to work documenting a wide range of activities at the school, with the before-and-after photographs occupying a pride of place in his work. A particularly fine example of this can be seen in his paired images of Wounded Yellow Robe, Henry Standing Bear, Timber Yellow Robe (figs. 2, 3). In the before image, the three men appear with a range of items selected and arranged to emphasize their exotic qualities. Indeed, the standing figure appears overburdened if not nearly buried in blankets, robes, and related items, hands all but hidden. His partners, each with a feather inserted prominently in his hair, sit on a rug that covers the floor that extends back to the illusionistic studio background, which suggests an architectural element on the left and an uninterrupted view into a landscape to the center and right. The boys regard the photographer (and viewer) with extraordinary frankness. In contrast, the second photograph presents the three youths in what looks like a comfortable Victorian interior space. No longer consigned to the floor, the two flanking boys sit on upholstered furniture and strike gestures appropriate to late nineteenth-century gentlemen-in-training. Hands, a key indicator to social grace, are placed prominently in one’s lap or on the shoulders of others. The illusionistic background describes an interior space that gives way to the framed view of a mountain. The boys direct their attention to the right, in deference to the viewer. Choate (and/or Pratt), unable to restrain baser impulses, positions the group so that the plant fronds rise up behind the figure on the left, mockingly, in imitation of the feather that appears in the previous photograph. While not as patently phony as Barnardo’s “contrasts” nor as insulting as the Pear’s Soap advertisement, the subtle differences between Choate’s two photographs effectively conveyed to fellow viewers what appeared to be a major change in the nature of the sitters. Indeed, they were effective because the differences were subtle and not heavy-handed. Pratt put such photos to a range of uses. In a letter to T. C. Pound, a member of the US House of Representatives, he wrote:

I send you today a few photographs of the Indian youth here. You will note that they came mostly as blanket Indians. A very large proportion of them had never been inside of a schoolroom. I am gratified to report that they have yielded gracefully to discipline and that our school rooms, in good order, eagerness to learn, actual progress, etc., are, to our minds, quite up to the average of those of our own race. Isolated as these Indian youth are from the savage surroundings of their homes, they lose their tenacity to savage life, which is so much of an obstacle to Agency efforts, and give themselves up to learning all they can in the time they expect to remain here.23

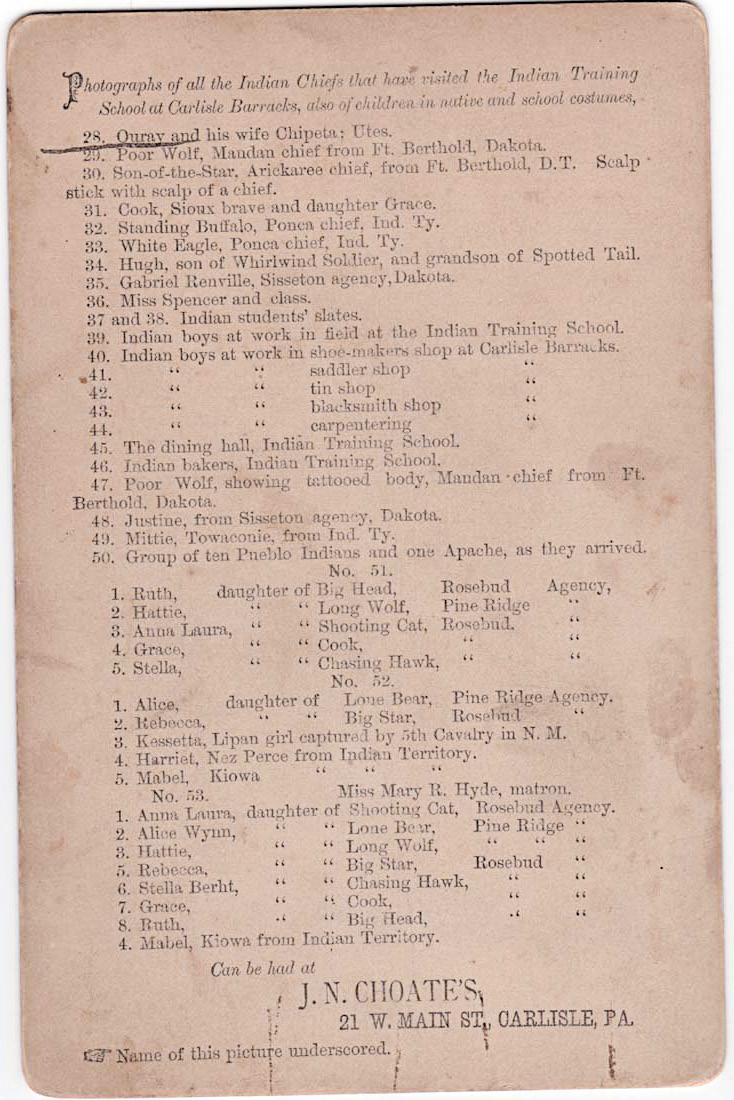

Apart from their political value, the photographs were a notable item in Choate’s inventory. On the backs of his photographs we find the following promotional text: “Photographs of all the Indian Chiefs that have visited the Indian Training School at Carlisle Barracks, also of children in native and school costumes (fig. 14).”24 It also appears that Choate and Pratt worked

together on marketing the photos. The Big Morning Star, a newspaper of the Carlisle Indian School, published instructions on how to order photographs of the students. In its April 1881 issue, the paper lists eighty-nine photographs of the Indian School and their prices. In 1886, two new subscribers to the newspaper would receive: “…two photographs, one showing a group of Pueblos as they arrived in wild dress and another of the same pupils three years after.”25 Assimilation was not only government policy, it was a commodity.

Pratt’s Tom Torlino and Goshorn’s Two Views Today, among the best known of Choate’s before-and-after images are two views of the Diné (Navajo) student Tom Torlino (figs. 15, 16). Here, the photographer presents Torlino bust-length, an image that shows little of the sitter’s clothing and symbols of status and rank and concentrates attention on his face. In this case, that concentration brings out that the face in the earlier photograph is much darker than the face in the later one. This difference, one could assume, served Pratt’s interests as it is presented in most vivid terms the physical—and by implication, cultural—changes that had taken place. Such a difference can be coincidental, or they can be achieved rather easily by the photographer—in advance (through different lighting scenarios, exposing/processing the negatives differently), after the fact (exposing/processing the photographic print paper differently), or a combination of both. From the photographs, it cannot be determined how precisely Choate achieved these results nor at what point he or Pratt seized upon their contrasting appearances and their potential usefulness. Nevertheless, there is little doubt that Pratt was pleased with the results. Today, these two photographs are iconic images that visualize, perhaps more vividly than any other, Pratt’s assimilationist mission. Indeed, they are among the most often repeated images from this context in circulation. As such, they serve as key resources for Shan Gorshorn.

15. John N. Choate, Tom Torlino (upon arrival at Carlisle), c. 1882. Albumen print on card. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

16. John N. Choate, Tom Torlino (three years later), c. 1885. Albumen print on card. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

17. Shan Goshorn, Two Views, 2018. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, polyester sinew. The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College. Purchased with funds from the Friends of The Trout Gallery, 2018.12.

18. Detail of Two Views. In 2018, Goshorn completed Two Views, a work that features Choate’s before-and-after photographs of Tom Torlino (fig. 17). However, rather than produce two baskets with a beforeand-after image on each—as she did for seven sets of baskets that make up Resisting the Mission, she wove the two images into one, integrating them into a single portrait (fig. 18). In doing so, Goshorn has stopped time, blunting Pratt’s efforts to divide an Indian into two successive beings along a temporal continuum; one to kill and one to save. She has also stopped movement through space, seizing on a central issue of permanent dislocation and loss of place and belonging faced by so many who experienced Fort Marion, Carlisle, and related institutions. She has, in one gesture, upended the fundamental tool of Pratt’s photographic propaganda: the ability of the camera to capture time and space as a means to shape an assimilationist narrative. Her weaving technique poetically resolves the complexity of assimilation into a single, haunting image; one that conveys a sense of how it feels to be torn from one’s world and thrust into another where they are not wanted. This reading of Two Views, one that stops time and space in the before-and-after photographs, causes one to re-evaluate the seven pairs of baskets in Resisting the Mission. Rather than reading them according to Choate’s and Pratt’s sequential ordering of time, as before-and-after images, I propose that they invite an “after” to “before” reading as well. One that reversed direction and causes the viewer to imagine “what has been lost?” To look at the “before” photograph and contemplate “what could have been?”

1. Phillip Earenfight, “Photography and Ledger Drawing at Fort

Marion,” paper presented at the symposium “A Kiowa’s Odyssey: A

Sketchbook from Fort Marion,” The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College,

Carlisle, PA, October 20, 2007; and idem, “Captive Images: Ledger

Drawings and Photographs from Fort Sill and Fort Marion,” paper presented at the symposium “Picturing the North American Indian,

Gettysburg College, Gettysburg, PA, November 20, 2009. The author is preparing this material for publication.

2. John Berger and John Mohr, Another Way of Telling (New York:

Pantheon, 1982), 7.

3. For the artist’s working methods, see the essays by Shan Goshorn,

Heather Shannon, and Gina Rappaport, in this volume.

4. On Choate, see Richard Tritt, “John Nicholas Choate: A Cumberland County Photographer,” Cumberland County History 13, no. 2 (Winter 1996): ; Lonna M. Malmsheimer, “‘Immitation White Man’: Images of Transformation at the Carlisle Indian School,”” Studies in Visual Communication 11, no. 4 (fall 1985): 54–75. Laura Turner, “John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photography at the Carlisle Indian School,” in Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879–1918 (Carlisle: The Trout Gallery, 2004): 14–18; Molly Fraust, “Visual Propaganda at the Carlisle Indian School,” in Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879–1918 (Carlisle: The Trout Gallery, 2004): 19–23; Antonia Valdes-Dapena, “Marketing the Exotic: Creating the Image of the “Real” Indian,” in Visualizing a Mission: Artifacts and Imagery of the Carlisle Indian School, 1879–1918 (Carlisle: The Trout Gallery, 2004): 35–41; Beth Haller, “Cultural Voices or Pure Propaganda? Publications of the Carlisle Indian School,” American Journalism 19 (2002): 65–68.

5. Lonna M. Malmsheimer, “‘Imitation White Man’”, 54–75.

6. David Silkenat, ““A Typical Negro”: Gordon, Peter, Vincent Coyler, and the Story Behind Slavery’s Most Famous Photograph,” American

Nineteenth Century History 15 (2014): 169–86.

7. Scholars of Fort Marion during the Plains prisoner of war years (1875–78) frequently reference the photographs made at the fort during this period. The author is completing a systematic catalogue and analysis of the surviving fifty or so surviving negatives made at Fort Marion.

8. James Brookes, “An Eagle on His Button:” How Martial Portraiture

Affirmed African American Citizenship in the Civil War,” US Studies

Online (2014), accessed July 10, 2018, http://www.baas.ac.uk/usso/ an-eagle-on-his-button-how-african-american-martial-portraiture-affirmed-black-citizenship-in-the-civil-war/.

9. One can see how this sentiment contributed to Pratt’s view of the

Indian “problem” and how a military-styled educational experience, such as the one he introduced at Fort Marion, represented what he believed was the solution.

10. Frederick Douglass, “Should the Negro Enlist in the Union Army?”

National Hall, Philadelphia, July 6, 1863, published in Douglass’

Monthly in August, 1863.

11. Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), 5.

12. Seth Koven, “Dr. Barnarbo’s “Artistic Fictions”: Photography, Sexuality, and the Ragged Child in Victorian London,”Radical History Review 69 (1997): 6–45; Kenneth Bagnell, The Little Immigrants: The Orphans Who Came to Canada, new edition (Toronto: Dundurn Group, 2001), 81—102; and Mark Oliver and Zeta McDonald, “The Echoes of Barnardo’s Altered Imagery,” The Guardian, October 3, 2002; and Simon Heffer, High Minds: The Victorians and the Birth of the Modern (London: Random House Books, 2013), 658.

13. George Reynolds, Dr. Barnarbo’s Homes: Startling Revelations (1875),

Goldsmith’s Library, University of London; and Oliver and McDonald,

“The Echoes of Barnardo’s Altered Imagery.”

14. Reynolds, Dr. Barnarbo’s Homes: Startling Revelations; Oliver and

McDonald, “The Echoes of Barnardo’s Altered Imagery.”

15. Oliver and McDonald, “The Echoes of Barnardo’s Altered Imagery.”

The British public was already alert to the problem of veracity associated with this new media. The controversy over Henry Peach

Robinson’s Fading Away (1858), a photograph representing a scene of a dying girl (she was a healthy model) compiled from five separate negatives, illustrates how viewers implicitly trusted the documentary appearance of the media and how it felt bitterly betrayed when it discovered otherwise.

16. Anne McClintock, “Soft-Soaping Empire, Commodity Racism and

Imperial Advertising,” in Nicholas Mirzoeff, The Visual Culture Reader (London: Routledge, 2002): 304–16.

17. Brad D. Lookingbill, War Dance at Fort Marion: Plains Indian War

Prisoners (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006); Richard

Henry Pratt, Battlefield and Classroom: Four Decades with the

American Indian, 1867–1904, edited by Robert M. Utley (New Haven:

Yale University Press, 1964); Everett A. Gilcreast, “Richard Henry Pratt and American Indian Policy, 1877–1906,” (PhD diss., Yale University, 1967).

18. Pratt, Battlefield and Classroom, 112–13.

19. This photographer was probably George Pierron, who maintained a portrait studio in the center of town, a few blocks from the entrance to the fort.

20.New York Daily Graphic, April 26, 1878.

21. On Pratt at Hampton, see Jacqueline Fear-Segal, White Man’s Club:

Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation (Lincoln:

University of Nebraska Press, 2008), 23–25; 102–35; Donal Lindsay,

Indians at Hampton Institute, 1877–1923 (Urbana: University of Illinois

Press, 1995). On the fate of the warriors who returned to Indian

Territory, see Lookingbill, War Dance at Fort Marion, 174–98.

22.Adams, Education for Extinction, 47; Samuel C. Armstrong to Richard

H. Pratt, 26 August 1878, MSS S-1174, Pratt Papers, Yale Center for

Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library,

Yale University, New Haven, CT; and Richard H. Pratt to Samuel C.

Armstrong, 13 October 1878, Armstrong Papers, Hampton University,

Hampton, VA.

23.Pratt, Battlefield and Classroom, 248.

24.Turner, “John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photographs,” 16, fig. 7. An example is back of the photograph Ouray and His Wife

Chipeta, Utes, Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle Indian

School, folder 12.

25.Turner, “John Nicholas Choate and the Production of Photographs,” 15; Malmsheimer, “‘Imitation White Man,’” 65.