11 minute read

Filling the Silence: Protecting the Names

Barbara Landis

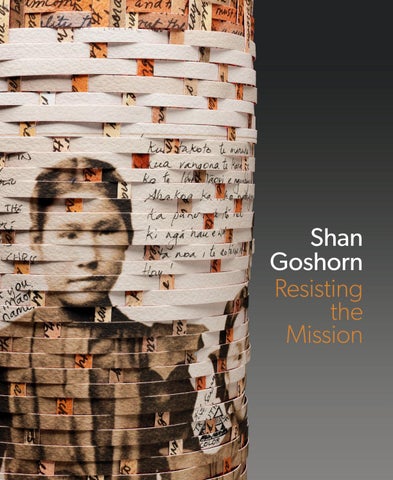

It was when I first saw a photograph of Shan Goshorn’s Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School that I realized the thousands of names of the Carlisle Indian School students had become memorialized and protected in a profound medium—the interior of a basket (figs. 1, 2). For thirty years, I have been collecting, sorting, and editing those very names, organizing them by nation, weeding out the duplicates, and uncovering new names found in Carlisle Indian School documents. My intention has always been to make those names accessible to the nations, including them as lists with every Indian School descendant inquiry I have answered in my work as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School Archives Specialist for the Cumberland County Historical Society (CCHS) in Carlisle (fig. 3). I developed those lists as web pages ready to be distributed upon request by relatives. Whenever I answer inquiries from descendants, I always include their nation’s list(s), and oftentimes my correspondents make discoveries of additional

1. Shan Goshorn, Educational Genocide; The Legacy of the Carlisle Indian Boarding School, 2011. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper splints. Montclair Art Museum, Montclair, NJ. Museum purchase, acquisition fund; 2015.12.a, b. Photo: Peter Jacobs.

2. Artist working on Educational Genocide.

OPPOSITE Shan Goshorn, Educational Genocide (detail), 2011, cat. 8. Photo: Peter Jacobs.

3. Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA.

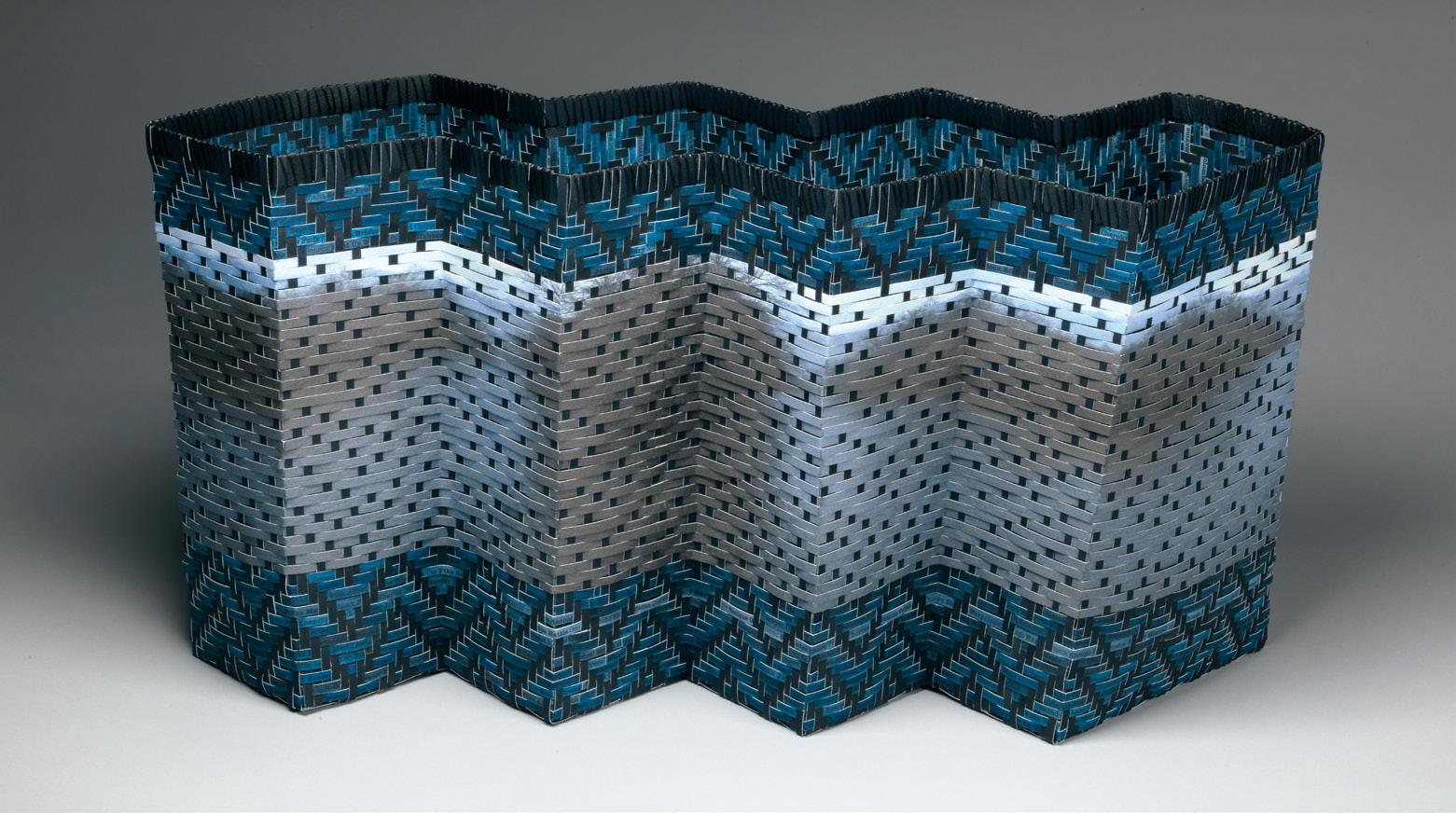

4. Shan Goshorn, Swept Away, 2016. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper splints, polyester sinew. Artist’s collection.

5. Shan Goshorn, Unexpected Gift, 2015. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper splints. Artist’s collection.

6. Shan Goshorn, Roll Call, 2016. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper splints. Artist’s collection.

7. Shan Goshorn, Decline, Challenge, 2014. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint on paper splints. Artist’s collection. names of Carlisle relatives whose stories had become lost to them. I have learned from corresponding with Native American archivists that it might not be appropriate to make those names easily accessible to the general public researching the Indian School because name lists might be printed and carelessly handled, buried under stacks of books, or wadded up and dropped into trash cans. Because of that, the student names I collect are not publicly linked, and relatives must know the URLs for the web listings in order to access them. The names are the sacred remnant of what we know as “Carlisle,” along with the stories held within descendant genealogies. These are the same names woven into Goshorn’s Educational Genocide basket on blood-red splints, in the shape of a coffin. They are held together in the interior of that basket coffin, protected by a lid, surrounded on the outside of the basket by images of the first children to be sent to Carlisle. The names have been put to rest, sheltered, and woven by the loving hands of a descendant, Shan. They have become the respected and honored representation of thousands of individual stories woven together and reconnected to one another in a good way. Several of Goshorn’s other baskets include splints of names of Carlisle Indian School students. Swept Away is Goshorn’s rendition of children swallowed up into the darkness of assimilation, inspired by a dream after visiting Carlisle (fig. 4). The fluidity of movement of chil-

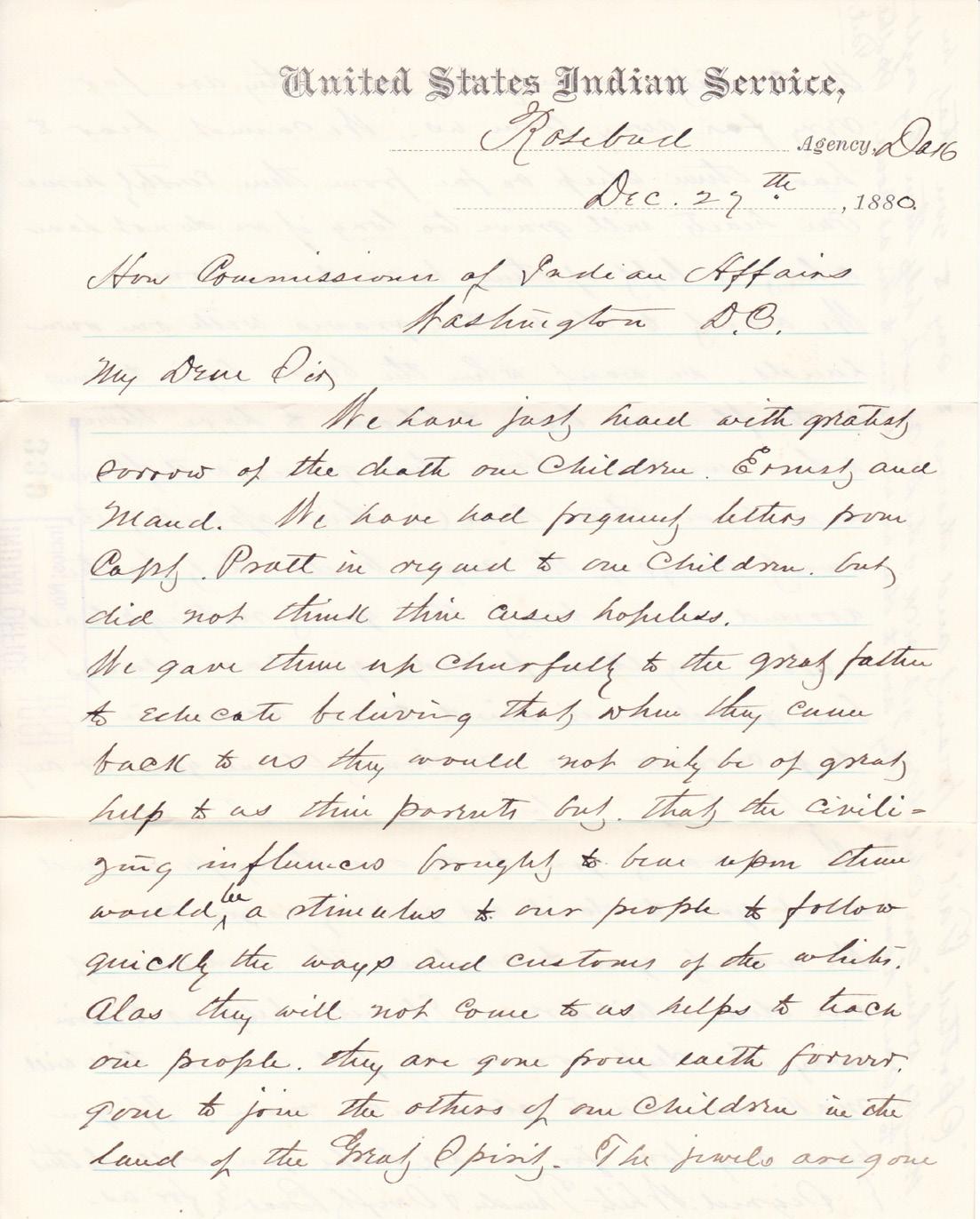

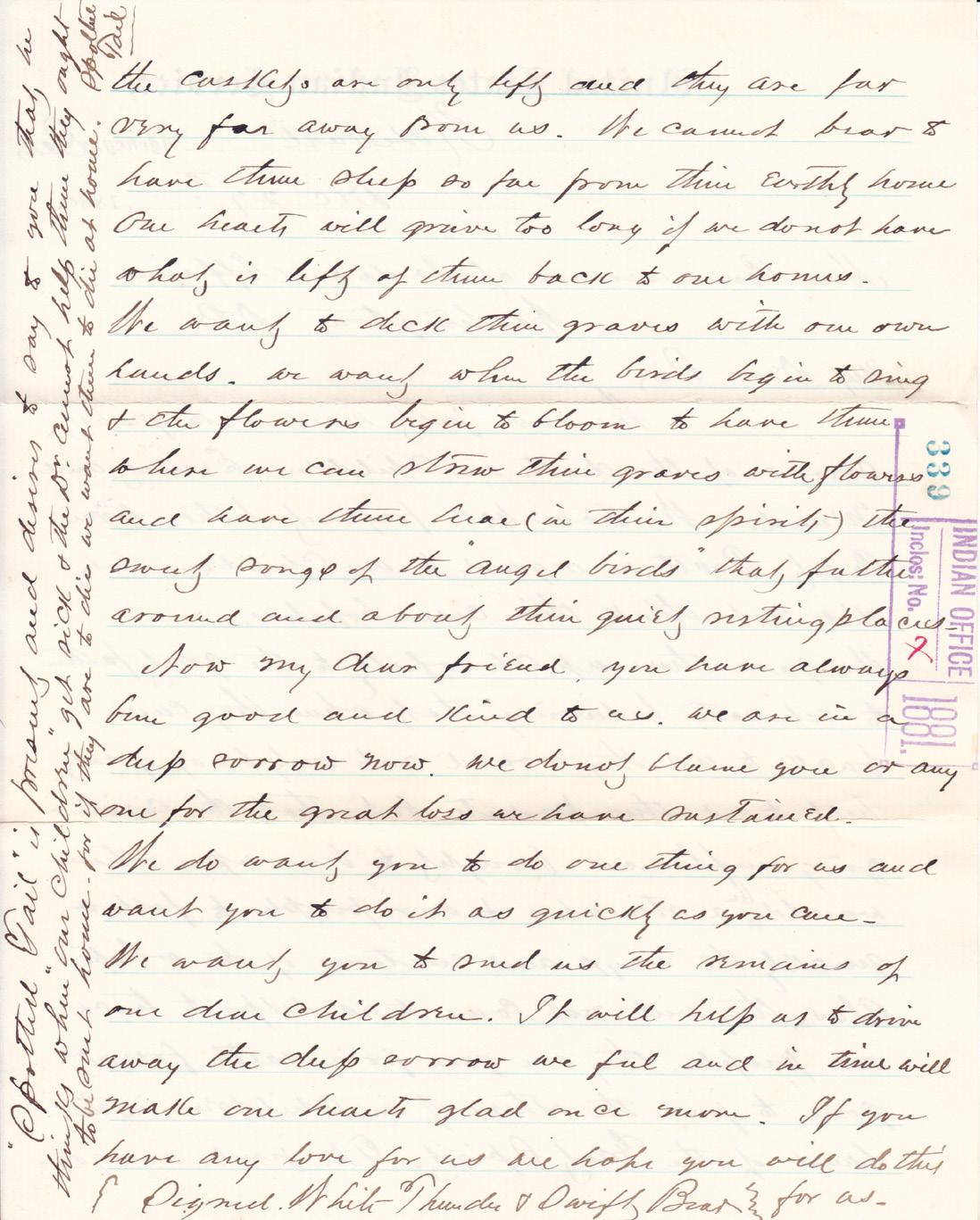

dren’s names embodied in the interior of the basket’s rippling water is recognizable to anyone imagining the trauma and hopelessness of offspring carried away in the darkness. Other baskets include student rosters, most notably Unexpected Gift, Roll Call, and Decline, Challenge (figs. 5–7), where the names that appear on the exterior of the basket seem to fade away. The Fire Within replicates the Cherokee Council Fire and includes the names of Cherokee students sent to Carlisle (fig. 8). Among the names found on and within these baskets is a unique set of names also found in the student rosters of the Carlisle Indian School—the names found on gravestones in the Indian Cemetery (fig. 9). The Indian Cemetery at Carlisle has been memorialized in many ways over the years. A pan-tribal group, the American Indian Society, based in the greater Washington, DC, area visits the graveyard on the Saturday of every Memorial Day weekend in May to freshen up the silk flowers in front of each stone, to sing, to pray, and to burn cedar, sage, tobacco, and sweetgrass. In 2000, during Cumberland County’s Powwow 2000, hundreds of descendants came to dance, and spiritual leaders from several nations memorialized the Carlisle student burials in unique and private ceremonies. In 2014, during the Cumberland County Historical Society’s initial Carlisle Journeys conference, a Lakota elder mixed soil from the grave of his great-grandfather Spotted Tail (South Dakota) and soil from the grave of Geronimo (Oklahoma), with that from the graves of Carlisle Indian School children from Apache, Lakota, and other graves, to bring familiar soil to the Carlisle children buried there. Although the US Army’s official Carlisle Indian School cemetery report includes a 1927 newspaper reference describing these burials as “unclaimed” remains, a recent discovery by the Dickinson College Special Archives Digitization Project contradicts this assertion. Rosebud Sioux leaders White Thunder and Swift Bear, whose children died at Carlisle, requested their children’s remains be returned to them. In a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs dated December 27, 1880, they wrote in response to the deaths of Maud Swift Bear and Ernest White Thunder:

We cannot bear to have them sleep so far from their earthly home. Our hearts will grieve too long if we do not have what is left of them [returned] back to our homes. We want to deck their graves with our own hands. We want, when the birds begin to sing and the flowers begin to bloom to have them where we can strew their graves with flowers and have them hear (in their spirits) the sweet songs of the angel birds that f[l]utter around and about their quiet resting places. (fig. 10)

When Shan, her daughter Neosha, and Emily Arthur toured the Indian School grounds in mid-May 2016, I accompanied them on a visit to the cemetery (fig. 11). We were there to plan Goshorn’s and Arthur’s respective exhibitions at The Trout Gallery for the centennial of the closing of Carlisle in 2018. I had visited the cemetery many times before, trying to find answers to nagging questions born out of my fear that the names found in the historic records did not

8. Shan Goshorn, The Fire Within, 2016. Woven basket: archival inks, acrylic paint, copper foil on paper splints. Artist’s collection.

9. Indian Cemetery, Carlisle Barracks. Photo: Charles Fox.

10. Letter from Maud Swift Bear and Ernest White Thunder to the US Commissioner of Indian Affairs, December 27, 1880. US National Archives, record group 75, entry 91, Letters Received by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (1881–1907), box 1, item 339, pp. 1, 2.

11. Shan Goshorn, Emily Arthur, and Barbara Landis at the Indian Cemetery, Carlisle Barracks, 2016. Photo: Neosha Pendergraft. perfectly match the names on existing stones. There are sets of plot maps showing names recorded when the cemetery was first moved in 1927, then again when stones were rearranged in 1947, and once more on the most recent map, which is currently posted on a plaque at the site. The three plot maps created after the reinternment of the Indian Cemetery show three different pairs of names for two sets of stones. While walking among the rows of stones and praying for every child, one by one by one, I was struck by how sincerely loved and protected each child had become at that moment. One of Shan and Neosha’s own community’s relatives was buried among the stones, a revelation found during Goshorn’s preliminary research. I watched Shan, the mother, with Neosha, the daughter, move through their memorializing process completely in sync, in quiet reverence to what was needed during their sojourn, photographing the names, placing the tobacco ties and the collected prayers and testimonials at the base of each stone. And then there was their connection to Mattie Oocumma, the Eastern Cherokee child buried there. It was a time of quiet reverence—a visitation profoundly sacred in its silence. It was a memorial act for those precious lives lost but whose names are not forgotten. And now those names live on—in a basket. Interest in the Indian Cemetery at Carlisle has brought the history of the school into broad public awareness during the past several years because of the efforts of groups of relatives determined to repatriate the remains of their Carlisle forebears (fig. 12). In the fall of 2015, a group of Rosebud Sioux youth passed through Carlisle on their way home to South Dakota from a visit to the White House Tribal Youth Gathering held by President Obama. The students’ chaperones designed a trip to the Carlisle Indian School grounds to make them aware of the history of their ancestors’ boarding school experiences. After touring the campus, the group

stopped at the cemetery. Dozens of teenagers walked through the graveyard and were confronted with their own surnames on the gravestones. Stunned by their discovery, they returned to South Dakota to advocate for the return of those relatives. After their intentions were publicized, the Rosebud Sioux contingency collaborated with an Arapaho woman who had tried to repatriate her own relatives ten years earlier. Her first efforts had been rebuffed by the US Army War College’s legal representative, but by the time the Rosebud youth began their quest, she had become the tribal historic preservation officer for her community. Hearing of the efforts of the Rosebud youth, she and her relatives revisited their own efforts to bring home three of their children who were buried in the Indian Cemetery at Carlisle. The Army Corps of Engineers offered their support and organized listening sessions and sent letters to all the nations representing students buried in the cemetery at Carlisle. The US Army acquiesced to the petitions of relatives and agreed to accommodate and pay for the return of the Northern Arapaho children sent to Carlisle in 1881 who had never come home. Affidavits were filed, elders were consulted, and arrangements were made to begin the process of repatriating three Arapaho children. In the summer of 2017, a contingent of relatives from Wyoming traveled to Carlisle to collect and return home the remains of Little Chief, Horse, and Little Plume. The group consisted of elders, youths, their chaperones, and their tribal historic preservation officer. During a tour of the school grounds, the young people received gifts of tobacco pouches that had been set aside from Goshorn’s packet of remembrances during her previous visit to the Indian Cemetery. It seemed as if her efforts of the previous spring to protect the children buried in Indian Cemetery now served to protect those who had come for their ancestors’ remains.

12. Warren Petoskey plays his flute at the Indian Cemetery, Carlisle Barracks, 2012. His grandfather and great-aunt attended the Carlisle Indian School. Photo: Charles Fox.

NOTES

1. The Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, PA, is the primary repository for archival materials associated with Carlisle Indian School.

Additional materials can be found in the Pennsylvania State Archives,

Harrisburg; the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian

Institution, Washington, DC; and the National Archives, Washington,

DC. The Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, Archives &

Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, draws together resources from a wide range of sources for online research. See http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/page/contact.

2. For information regarding the cemetery, see http://carlisleindian. dickinson.edu/cemetery-information; Genevieve Bell, “Telling Stories Out of School: Remembering the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 1879–1918” (PhD diss., Stanford University, 1998); Jacqueline FearSegal, White Man’s Club: Schools, Race, and the Struggle of Indian Acculturation (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2007); Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose, Carlisle Indian Industrial School: Indigenous Histories, Memories, & Reclamations (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2016); J. W. Joseph, Hugh Matternes, and Matthew Rector, Archival Research of the Carlisle Indian School Cemetery: U.S. Army Garrison, Carlisle Barracks, Carlisle, Pennsylvania (New South Associates Technical Report 2635, Contract W912P9-16-D-0015, Task Order 6. July 5, 2017); Barbara Landis, “Death at Carlisle: Naming the Unknowns in the Cemetery,” in Fear-Segal and Rose, Carlisle Indian Industrial School, 185–200; “Cemetery Information,” Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center, Archives & Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Dickinson College, accessed July 14, 2018, http://carlisleindian.dickinson.edu/cemetery-information/ resources.

3. The American Indian Society was established in Washington, DC, in 1966 to preserve Native culture by teaching and promoting customs and arts, by promoting health education, and through other civic duties that continue to contribute to the social advancement and wellbeing of American Indian communities.

4. “Cemetery Information” (see note 2).

5. Ibid.

6. Indian delegations to Washington, DC, dating back to the nineteenth century, often included an excursion to Carlisle, to visit family, friends, and students associated with the Indian School. See Herman J. Viola,

Diplomats in Buckskins: A History of Indian Delegations in Washington

City (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1981).