45 minute read

Weaving History, Lives, Justice, and Beauty into Art with Something to Say

Suzan Shown Harjo

Multifaceted and Nuanced Art Statements Shan Goshorn is a brilliant, wise, and beloved woman—brave, caring, passionate, and compassionate. A truth seeker, she is a stronghearted, good-humored activist for the rights of Native Peoples, women, artists, the environment, and more. A mixed-media, concept-based artist of great renown, she utilizes photography, painting, basket making, silversmithing, and collage and montage artistry to make her two-dimensional and three-dimensional works. Her many series make fulsome, cohesive statements, and she masters each subject in a manner worthy of acknowledgment as a scholarly dissertation. As both a friend and curator, I have long been a “Shan fan,” and I am privileged to offer these words about her as a sister in arts and activism. A daughter, citizen, and honored artist of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians in North Carolina (Wolf Clan), she was given the name of Yellow Moon. She has lived and worked in Oklahoma for over half of her life in Tulsa, a city that grew from the convergence of lands and peoples of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), and Osage Nations. Oklahoma boasts thirty-nine Native Nations, with distinct cultures and histories, and whose citizens include an astonishingly high ratio and variety of artists. Shan is recognized as a courageous artist-activist, a champion of fairness and justice in our time, for the ancestors, and for the coming generations. Public descriptions of her often say that Goshorn is “best known for her baskets,” but she considers herself an artist who uses the “medium that best expresses a statement.” I have curated her work in exhibitions and have known her over the decades as one of the best artists in whatever medium she was working at the time. She is also a captivating storyteller and a most effective advocate. In making art or otherwise imparting knowledge, she is clear and unflinching about treaty violations, grave robbing, violence against women, torture of children, harm to Mother Earth, mascoting and stereotyping, and damage to Native languages and sacred places. Her statements give heart to those searching for ways to present issues and to reach for solutions to our myriad emergency situations. The impact of her work is incalculable. In our Tsistsistas (Cheyenne) way, we are instructed to choose our friends as we would choose people to take into battle and to make peace, after or even without fighting. Goshorn is such a person. For years, I have considered my friendship with her as one of my defining features, but it is not necessary for the visitor or reader to meet her in person to know the multifaceted and nuanced Shan Goshorn through her body of work. I would like to introduce or reintroduce her, in some leaps through time, with a few examples of her art and advocacy periods and pieces that led to this magnificent exhibition of her multimedia basketry work.

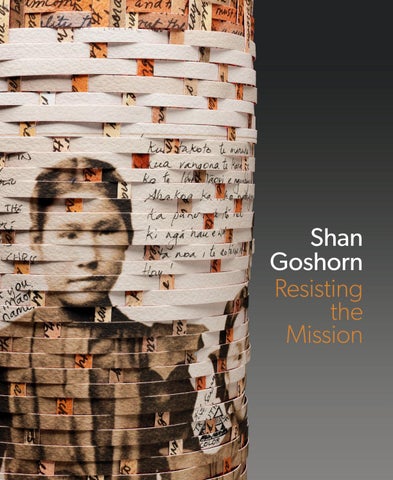

OPPOSITE

Shan Goshorn, High Stakes: Tribes Choice #2, 2011. Digital photograph: archival pigments and glitter on paper.

1. Bob Haozous, Artificial Cloud, 1991. Steel. Tulsa, Oklahoma. Photo: Jay Goebel / Alamy Stock Photo. Native Visions and Voices in the Columbus Quincentenary Shan and I first met in Tulsa in 1992, during the ramp up to the high-visibility Columbus Quincentenary (or The Invasion, as it is known in Native circles). We were there to celebrate the work of Chiricahua Apache artist-activist Bob Haozous, at Tulsa’s dedication of his monumental sculpture Artificial Cloud, and to amplify Native visions and voices on these main points:

First: This red quarter of Mother Earth was the home of great civilizations and cultures for millennia before the lost Columbus washed upon our shores.

Second: 500 years of genocide, ecocide, and erasure caused the deaths of millions and ongoing misery and trauma for survivors.1

Third: Native Peoples are still here. We are trying to explain what happened to us since 1492, with persistent, urgent hope that knowledge will help prevent it from happening again. We are engaged in reclamation and education work to make a better world over the next 500 years and beyond.2

Artificial Cloud is one of Bob’s important public art statements on these points (fig. 1). At 71½ feet tall, his steel sculpture is capped by a wide billowy cumulus-cloud shape on a broad-based, three-tiered pedestal that narrows skyward to a spire supporting the cloud. On the pedestal are cutout and welded figures: gingerbread-style people with missing hands or feet; disembodied hands; airplanes flying and falling; humans right side up, upside down, and sideways; directional arrows pointing both up and down; and a few oversize manacle ankle rings resembling giant door knockers. The sculpture is made of untreated steel, to show the corrosive effect of pollution over time. After the dedication, Shan and I hit it off, recognizing common concerns with human rights, the environment, and the continuing genocidal tendencies hemisphere-wide. Indigenous and allied writers, visual artists, teachers, parents, and students were busier than we ever expected, with 1992 exhibits, concerts, and forums; campaigns against the emotional violence inflicted on our youth by the advertising and sports worlds through caricatures and false narratives; and sunrise ceremonies and observances commemorating those Native Peoples who did not survive and celebrating those who did.3 Our intensive work and focus kept the years from 1992 to 1994 from becoming a massive “discovery” extravaganza that portrayed us, if at all, as onlookers at the march of history. Collectively, we persuaded many cities, schools, cultural centers, and social justice organizations to invite Native speakers, to commission and show Native artists’ work, and to hire indigenous teachers. With stepped-up media coverage of Native America, our “rock the boats” campaign tamped down multiyear plans for replicas of the Nina, Pinta, and Santa Maria to make dockings in ports never seen by Cristobal Colon. Goshorn’s imaging and speaking abilities were invaluable in this broad public relations movement, and it was in this context that she was making visual imprints with her people’s art. Our consciousness raising then helped grow the ongoing movements toward Native Studies and designations of Indigenous Peoples Day.

Mascoting, Stereotyping, and Commodification Goshorn’s constructions and montages provide visual commentary on the social injustice of invidious discrimination and the distortions of cultural identity in popular culture. She points

out that the names of great nations are better known as vehicles, insurance companies, sports teams, and buildings, and argues that our cultures should be respected, “not flaunted like some advertising gimmick.” Her work on “Indian” mascoting and name-calling in sports is part of the widespread movement that has eliminated two-thirds of all so-called Indian symbols, logos, caricatures, mascots, and behaviors from American educational athletic programs. Native Peoples and allies have consigned more than 2,000 of these race-based stereotypes and cultural appropriations to museums and history books since the first one was removed in 1970, when the University of Oklahoma formally retired its dancing mascot, “Little Red.”4 Goshorn’s Honest Injun collection, launched in 1992, shows the wide range of misrepresentations of Native ceremonies, clothing, appearance, histories, and values resulting from 500 years of commodification. Her hand-painted black-and-white photographs of commercial brands that use so-called Native names and imagery to sell their products include the Land O’Lakes butter maiden (fig. 2) and “Chief Wahoo,” a former symbol of Cleveland’s Major League Baseball team. In 2015, California became the first state to ban public schools from using the vile name they shared with Washington, DC’s National Football League franchise.5 With only 1,000 remaining on the “Indian” mascot horizon, and with more changing every month, these branded disparagements soon will go the way of the once ubiquitous lawn jockey. Goshorn continues this vital work in other mixed-media pieces such as No Honor, which she writes was informed by historical connections between a slur on a sports pennant and Indian bounty hunting (fig. 3). Many colonies and trading companies, and some states proclaimed bounties on certain targets, such as the Massachusetts bounties (1775) for the capture or scalps of Penobscot Nation men, women, and boys and girls under age twelve, “that shall be killed and brought in as evidence of their being killed.”6 Others aimed at generic Native targets—as with the Pennsylvania bounties (1764), assigned according to a sliding scale, on “hostile Indians”7; the California bounties (1850s) for heads or scalps of Indians who stood in the way of goldrushers; and the Minnesota “reward” (1863) for “every red-skin sent to Purgatory”—or related practices involving scalping, skinning, parading, and cashing in “war trophies” of parts of Indian bodies, notably documented in three military inquiries by Congress and the Secretary of War into the Sand Creek Massacre (1864).8 Some proclamations used the word “scalps,” also using “topknots” for hair from the head, both of which involve skinning. While topknots might be enough proof for bounty payers that the hair and skin came from dead Indians, or arguably were tribally specific, they were insufficient to prove the gender or maturity of a deceased person. That evidentiary level required the scalped genitalia, entire skins, or whole bodies, but the latter were not viable in terms of transportation or storage. Goshorn and other human rights activists have decried the use of racial slurs for years. (I have done so since 1962 in the movement that started before my time.) In No Honor, Goshorn combines the slur on a sports pennant with identical dictionary definitions for it and for offenses against others that are long absent from polite society. “Why,” she asks, “is one term acceptable and the other not?” In another series she approaches wrongheaded notions by bringing actual Native people to the fore. Her installation Reclaiming Cultural Ownership; Challenging Indian Stereotypes presents thirty-six documentary-style images of Native people living everyday life. Related to this series is Indin Car, which was featured in an exhibition at the District of Columbia Arts Center (fig. 4). In this work, she recontextualizes the pejorative cliché “Indian car”—meaning a vehicle “so worn-out, beat-up and pitiful” that it had to be “owned by an Indian”—as simply a car of Indians. Hers is an image of a carload of Cherokee warriors wearing traditional regalia, and red

2. Shan Goshorn, Land O Lakes Margarine, from Honest Injun, 1992. Hand-painted black and white photograph.

3. Shan Goshorn, No Honor, 2014. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper.

5. Shan Goshorn, High Stakes: Tribes' Choice #1, 2011. Digital photograph: archival pigments and glitter on paper.

6. Shan Goshorn, High Stakes: Tribes' Choice #2, 2011. Digital photograph: archival pigments and glitter on paper.

and black face and body paint. Of all the excellent work in this show, by a dozen top Native artists, Goshorn’s Indin Car was the lead image selected by The Washington Post for its first feature on the exhibition.9 Goshorn’s work supports many human rights causes and efforts to inform the general public where the education system has failed to do so. As just one example, she has worked with other Native artists in Oklahoma to set the record straight on the state-revered traditions of the “Boomer Sooner” legacy and the ongoing ill effects of non-Native settlers’ land rushes for Native territories. In the late 1800s, tribal lands were declared “excess” by a federal law that was discredited and overturned a half-century later, but not before two-thirds of the Native land base had been lost to taxes, oil and land speculators, railroad barons, and shady bankers, judges, lawyers, and government agents. Goshorn also tackles various aspects of the often-contentious issues surrounding tribal gaming operations, informing non-Natives about the inherent sovereignty of Native Nations that courts and Congress affirm as the authority for these businesses, and trying to stop the endless gibes about rich casino Indians. In High Stakes: Tribes’ Choice #1 and High Stakes: Tribes’ Choice #2, she addresses the related topics of self-stereotyping and cultural exploitation (figs. 5, 6). She hand-colored two black-and-white silver-gelatin photographs of a Native woman and Native man in traditional outfits, making the companion images sparkle in fine-grade glitter. She describes the works as commentary on the tensions between the glitz of casinos and traditional tribal culture that is used to attract customers. This work is a cautionary note for Native Nations to consider carefully “how we allow ourselves and our traditional ways to be marketed.”

Earth Renewal and Earth Return Series From 1997 to 2010, Goshorn produced work for two series, Earth Renewal and Earth Return. Describing Earth Renewal as conceived during a very difficult pregnancy, Goshorn has written

that she followed medical advice and withdrew from political activism to focus on supportive imagery that would help her create a healthy pregnancy and birth of her daughter. Her double-exposed, hand-tinted black-and-white photographs began during “this meditative time,” and are illustrative of traditions and ceremonies regarding the “nurturing qualities of our original mother, the earth” and the “caretaking duties” of her human children. One of her personal favorites in the Earth Renewal series is Kituwah Motherland, showing the translucent image of a Cherokee woman, symbolic of ceremonial renewal, superimposed on the Kituwah Mound, the Cherokee origin place (fig. 7). Located on Eastern Band Cherokee land near the Tuckasegee River in the Great Smoky Mountains of North Carolina, the Kituwah Mound also is recognized as the spiritual and historical Mother Town by the Cherokee Nation and the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma. Goshorn made her homage after part of the mountain overlooking Kituwah was bulldozed for a power plant, which the energy developer agreed to build elsewhere when faced with an outpouring of concern and organized action. Goshorn’s work helped raise awareness and funds to address ways to protect the sacred place. The Eastern Band designated Kituwah as a “sacred site” in 2013, saying it holds ancestral remains and embodies the “sacredness of all that existed [and] for future generations.” Earth Return “gives voice to the struggle” of Native Peoples in protecting and repatriating ancestors and sacred and cultural patrimony from collections and holding repositories throughout the United States. After centuries of grave robbing at burial grounds and looting and defacing ceremonial places—with both Native remains and sacred items fenced, bought, and sold as art and artifacts—the US Congress enacted the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 and other related human rights laws. Despite the legal protections, both Native people and objects continue to be trafficked, auctioned, and marketed at escalating prices; displayed, studied, and exploited for tourism or profit, or in the name of science; and exhumed, poisoned, and otherwise desecrated by drilling, mining, vandalism, recreation, and other geophysically damaging activities.

7. Shan Goshorn, Kituwah Motherland, from the series Earth Renewal, 2010. Hand-colored black-and-white photograph.

8. Shan Goshorn, Industrial Trade Blanket #1, 2007. Acrylic with brass, copper, steel, and metallic foil. The “wounds inflicted by institutionalized racism,” cannot heal, says Goshorn, “until we are perceived as human beings” rather than as “archeological artifacts.” In 2003, Goshorn’s repatriation work was in a two-artist show with Comanche artist Juanita Pahdopony at the American Indian Community House Gallery in New York City. Otoe-Missouria playwright Annette Arkeketa’s play Ghost Dance was performed, and Shan, Annette, Juanita, and I made remarks on a post-play panel. It was one of the best discussions on repatriation issues in my memory (and that includes over fifty years of talking about and working on repatriation and museum policy issues, since 1967). The images and voices of Goshorn and other artists have contributed significantly to efforts at instituting and enforcing US policies that address these cultural imperatives, and to the ongoing efforts of Native Peoples to improve the laws and complete returns. Goshorn’s art and explanations of these protective policies and why they are necessary have helped to educate many people who might be otherwise confused. Some tend to resent such policies, wrongly thinking they confer special privileges to Native Peoples, and somehow take something away from non-Natives. In fact, other segments of American society do not need remediation, because non-Natives already enjoy policy privileges and have not been subjected to the harrowing, multigenerational experiences and unjust laws that we have endured. While such remedial legal action is essential, it still may need to be explained. Through her art, Goshorn makes this type of history and information accessible to people who know little about laws of this nature and our unique need for and relationship to complex substantive legal policies.

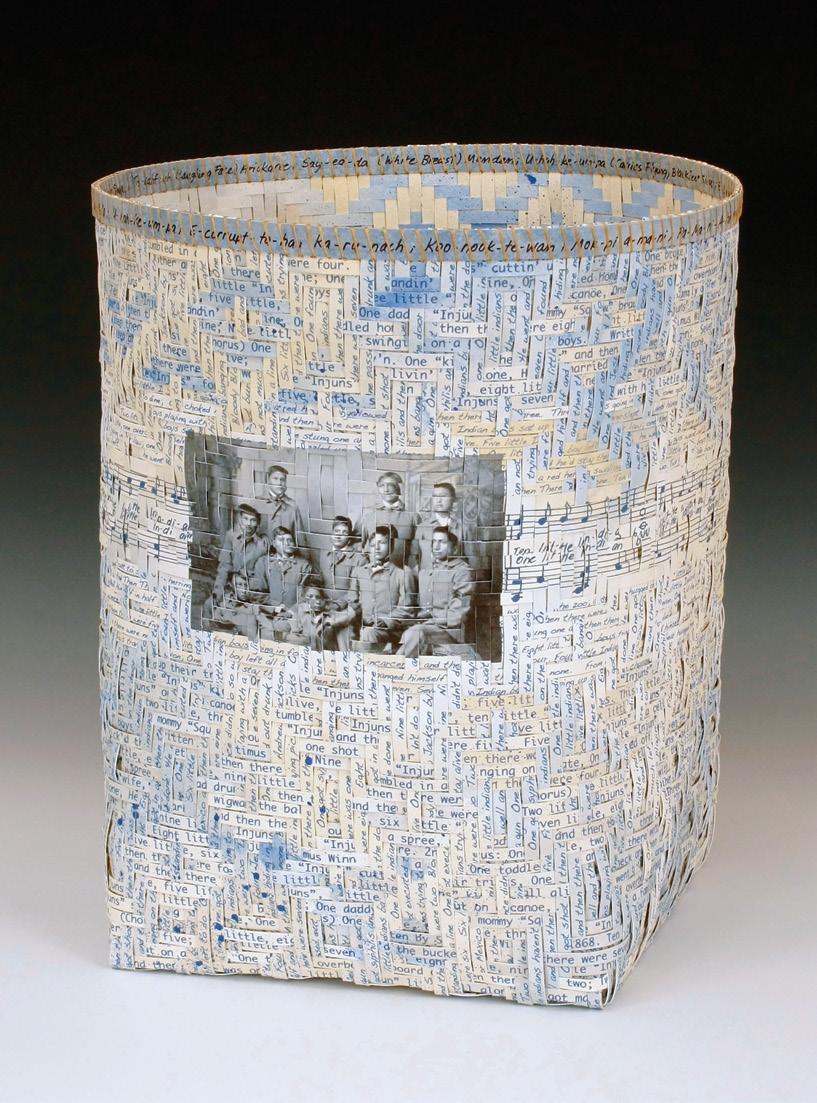

Industrial Trade Blanket Series and 10 Little Indians Goshorn’s Industrial Trade Blankets series was inspired by the colors and symbology of the wool blankets Native Peoples initially acquired as trade items, first from the English, Scots, Spanish, French, and Irish, and later from the Americans. Native Peoples in what are now the Northeast and mid-Atlantic US were wary of the trade blankets, because word that some carried smallpox spread almost as quickly as the deadly disease, and many believed that it was a military weapon to clear the land. Native lack of immunity to the diseases brought here by Europeans—from the common cold, consumption, influenza, measles, mumps, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and whooping cough to bubonic plague, chicken pox, cholera, syphilis, typhoid, and others—eradicated entire Indigenous Peoples and untold numbers of Native persons in wave after wave of epidemics. Eventually, trade blankets became more common than hides or furs as outerwear, sleep covering, and shelter, due to the rapidly dwindling numbers of buffalo, elk, antelope, beaver, fox, and other animals that were being hunted, trapped, and pushed to the edge of extinction by the increasingly lucrative Euro-American markets and the growing immigrant populations. By 1900, the Native population was below 250,000, while non-Natives in the United States numbered more than 75 million. Trade blankets also symbolized Native “primitiveness” and “savagery.” “Back to the blanket” and “blanket ass” were pejoratives used against Native students and adults who, after being “civilized,” returned to traditional ways, speaking heritage languages, painting and dancing in ceremonies, and wearing long hair and hides, furs, trade cloth, and blankets.10 Goshorn’s Industrial Trade Blankets series is comprised of multimedia works that feature paint, brass, copper, steel, and metallic foil, symbolizing bullets, mining, scourges, and other pressures that caused the swarms of non-Natives and the vanishing Native populations. Goshorn

started the series in 2006 and completed it in 2008. Among the works in the series is Blanket #1 (fig. 8), which features a red-orange field and a wide strip of metallic foil, suggesting the stripes found on original wool trade blankets. On either side of the foil, Goshorn shows small round metal objects, which resemble the abstracted images of bone sections with missing marrow commonly seen on Native blankets, where they symbolize industry, precious metals, and pox. Goshorn continues to explore blanket symbolism in her work in other formats, notably in 10 Little Indians (figs. 9, 10), a single-weave basket that deals with dancing and dead Indians. She interwove two historical photos with three versions of the song “10 Little Injuns,” including the original lyrics of 1868, hate filled and graphic, about how the “little Indians” were killed or committed suicide. The basket exterior integrates a pair of before-and-after photographs, one representing a group of Native boys in blankets upon their arrival at the Hampton Boarding School and another of boys at the Carlisle Indian School in military uniforms. Inside the basket are drawings taken from the song’s music sheet of what Goshorn describes as “dancing children dressed as pretend Indians.” Her 10 Little Indians reminded me of two items in The Indian Helper, the weekly newsletter of the Carlisle Indian School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.11 A story in the March 23, 1888 issue is about “a party of Apache Indians,” after a trip to Washington, DC, “visiting their children and relations at Carlisle before starting west again” with an interpreter and their 10th Cavalry escort. The other item, “Our Exhibition,” begins: “Monday night the Apache chiefs did not come…. There were ‘Ten Little Indian Boys,’ however, who counted themselves out and in again in a most mathematical and delightful way….”

Displacement Installation In Goshorn’s installation Displacement, images of songbirds are painted on seven small canvases, with nine wood cutouts on the wall of swallows in flight (fig. 11). Calling her dark cutouts “shadows of hope,” Goshorn here expresses the wish that indigenous cultures “will persevere.” A lifelong fascination with birds led her to qualify for a federal wildlife license,

9. Shan Goshorn, 10 Little Indians, 2013. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic on paper.

10. Detail of 10 Little Indians.

specializing in orphaned and injured migratory songbirds, which she calls “barometers of the earth’s health.” She is particularly concerned about two invasive species—the European starling and English sparrow—and their devastating impact on and the alarming decline of indigenous songbirds. Emphasizing that she is speaking of birds, she says “it is not a far jump” to “think about Indians.”

Defending the Sacred—Standing with Standing Rock Immersing herself in historical research, Goshorn diligently looks for the context, meaning, and details of her subject imagery and content. In 2017, she made Defending the Sacred (figs. 12, 13), a mixed-media sculpture, to promote awareness of the environmental and humanitarian battle taking place on the original and treaty land of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe and others of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), Great Sioux Nation. Dakota Access, LLC, and Energy Transfer Partners proposed—and the US Army Corps of Engineers approved in April 2016—a pipeline to haul 450,000 barrels of fracked oil sludge each day underneath the Missouri River and Lake Oahe, risking burst pipes that would contaminate the sole source of fresh, safe water for the entire region, as well as severely damage the ancestors and ceremonial lands and waters of several Native Nations. The pipeline would extend for more than a thousand miles, from North Dakota’s Bakken oil fields through South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois, and then be transported separately to the Gulf of Mexico.12 After a federal finding that the pipeline would not harm Native historical places, supporters joined with the Standing Rock Tribe to peacefully oppose threats to the water and sacred landscape. Rallying around the message Mni Wiconi (“Water Is Life”), thousands camped at the confluence of the Cannonball and Missouri Rivers, and hundreds of Native Peoples sent supplies and other support. In September 2016, UN Indigenous Peoples Rapporteur Victoria Tauli-Corpuz and many other UN experts called for a halt to construction because it threatened water, burial grounds, sacred places, treaty rights, and the health and well-being of Sioux Peoples, and because Standing Rock was denied consultation and information regarding the “presence and proximity” of pipeline routing and siting to the Reservation.13 Article 19 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples mandates UN countries’ good-faith consultation and cooperation with Indigenous Peoples and that they “obtain their free, prior and informed consent before” taking “measures that may affect them.”14 The US Army assistant secretary for civil works, Jo-Ellen Darcy, announced in December 2016 that the pipeline easement at Lake Oahe would not be granted, and that it was most

responsible and expeditious to explore alternate routes for the pipeline crossing.15 That good news and two blizzards brought the encampments to an end. However, in January 2017, as one of his first acts following inauguration, President Donald J. Trump reversed the army’s decision with a presidential memorandum, fulfilling a campaign promise to fast-track construction of the $3.8 billion pipeline (without disclosing he had owned stock in the pipeline companies that he only recently had divested).16 Within weeks, the army announced its intent to grant a thirty-year easement to the Dakota Access for a 30-inch diameter underground light crude pipeline at Lake Oahe Dam and Reservoir. Goshorn’s Defending the Sacred is a briefcase-shaped basket woven in the Cherokee “water” design that covers the outside and inside walls. Photographs and text are interwoven on the interior and exterior surfaces of the briefcase. The interior walls include a photo of a prayer fan woven among splints that bear the words of Lakota prayers, symbolizing protection and Standing Rock’s commitment to peace. The fan faces an image of the vast Oceti Sakowin camp. The exterior walls display the text of the Horse Creek Treaty (1851) as well as a photo and the text of the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), between the United States and the Sioux Nations. As the standoff at Standing Rock caught the attention of the world, comparisons between the pipeline and a snake were capturing the imagination of many, including Goshorn. Lakota and Dakota visions, dreams, and prophecies revealed an approaching black snake made of greed’s pure poison, and those who spoke publicly about those things said that the snake arrived as the pipeline. Standing Rock’s then-chairman David Archambault II, of the Hunkpapa and Oglala Lakota, referenced the comparison in a New York Times opinion piece.17 He wrote that the pipeline “would snake across our treaty lands and through our ancestral burial grounds…. a half-mile from our reservation…[crossing] the Missouri River, which provides drinking water for millions of Americans….” Goshorn wove the snake motif over Dakota Access propaganda on her briefcase’s remaining outside wall and featured another image of the Oceti Sakowin camp of “protectors

12. Shan Goshorn, Defending the Sacred, 2017. Woven suitcase: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, with wood, antler, artificial sinew, glue, brass.

13. Detail of Defending the Sacred.

14. Shan Goshorn, Pieced Treaty: Spider’s Web Treaty Basket, 2007. Woven basket: ink and acrylic on paper. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. of the sacred earth and water.” She chose the briefcase structure because the battleground is the judicial system, where the court case, initiated in July 2016, has lasted longer than the ten-month standoff. She writes that the briefcase’s handle hardware is made from antler, signifying the “strength of our resolve.” Not only has she given the issue her creativity and voice, she also donated all proceeds from Defending the Sacred to the Standing Rock Sioux legal fund. This is yet another example of why Goshorn is respected, admired, and beloved.

Message in a Vessel In her long, successful career as an independent artist, Goshorn did not try to make a basket until 2006, but she is a natural at making conceptually based baskets of watercolor-paper splints, using the shapes, patterns, and methods of traditional Cherokee baskets. She prints the text of presidential messages, congressional records, quotations, treaties, and laws, as well as maps, photographs, and other texts and images on the paper before cutting it into splints that she then weaves. In the short documentary profile Shan Goshorn by Seminole and Muscogee filmmaker Sterlin Harjo, the artist recalls the hostility toward her activist work as “people wrapping themselves up in barbed wire,” denying any possibility that their “ideas were bigoted.”18 That changed when she started making woven statements, a change she attributes to the “unassuming shape” of a basket, “a vessel for mothers or grandmothers” to gather, carry, or support something, “maybe a baby.” Calling the basket vessel a “nurturing part of our history, of our memories,” the film shows her weaving in the midst of artworks in progress. She describes people being comfortable with the nonthreatening nature of the basket and becoming “so curious” about the colors, patterns, images, or words that “they literally lean in so they can understand and see.” And “that’s the moment” for this “conversation I’ve been trying to have for thirty years.” She is joyous that people “actually get it,” understanding through her baskets what is problematic about their attitudes and expressions regarding mascots, treaties, sovereignty, and other issues Native Peoples deal with daily.

Pieced Treaty: Spider’s Web Treaty Basket—Goshorn’s First Two Single-Weaves It was my good fortune to be in the vicinity at the origin of Goshorn’s career of mixed-media basketry excellence. One day in the mid-2000s, she called and asked what I was working on, and I updated her on the Nation to Nation treaties exhibition and book I was guest curating and editing for the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI).19 W. Richard West Jr., of the Cheyenne, green-lit the project in 2003, and I co-curated it with Standing Rock Sioux author, theologian, historian, activist, treaties expert, and dear friend Vine Deloria Jr. We had constructed the spine and arc of the exhibition and book, and decided on certain treaties, objects, oral histories, and texts to illustrate treaty making, what each party wanted, and how treaties are living, breathing, continuing, and exercised daily. We were looking for contemporary artwork that would help convey the nation-to-nation continuum, make sovereignty understandable, and place treaties in the present and future tenses. Goshorn promised to think about what she might create with a treaties theme, perhaps in a basket: “I’ve always wanted to make a basket; maybe this is the right time.” Time passed, but before I could follow up, she had emailed a photo of Pieced Treaty: Spider’s Web Treaty Basket (fig. 14). It was sculptural, contemporary, tradition based, and the first basket she ever made. She printed the Cherokee Nation–Oklahoma Tobacco Compact on watercolor paper, which she painted and cut into splints that she then intertwined in the traditional Cherokee spider’s web pattern.

Pieced Treaty is a large woven mixed-media basket, with a shock of long unwoven splints of text sprouting from the woven top, and others cascading down the sides. The weaving techniques, paints, and text contribute shades of pink, from champagne and cherry blossom to Persian and rose. The large pink basket fit right in with our foundational color palette, based on the purple, lavender, and white beads made from quahog clamshells and whelk shells, which are used for wampum strings to verify authority, credentials, or memory, and for the woven wampum strips that are many Native Nations’ records of treaties and events. The palette was set early on, when we decided to display as many Nations’ wampum as possible and to feature the Two Row Wampum (the Haudenosaunee-Dutch Treaty of 1613) as a visual, thematic thread of the exhibition. West jumped at the chance for the NMAI to acquire Pieced Treaty, and it became part of the museum’s permanent collection in 2007; both he and incoming director Kevin Gover, of the Pawnee, were enthusiastic about showing it in our exhibition. Goshorn later wrote that Pieced Treaty refers to the continual breaking of agreements. Her basket was deliberately left unfinished to reflect the tobacco compact’s contentious renegotiation status. When our exhibition opened in 2014 at the NMAI on the Mall, Goshorn’s premiere basket was prominently placed at the exit, to give visitors a visual takeaway of the intricate, continuing, unfinished story of treaties, and sovereign Nations’ promises of peace and friendship forever.

A Greater Degree of Difficulty: First Double-Weave, Sealed Fate The intense interest in her first mixed-media baskets encouraged Goshorn to tackle the more difficult double-weave. She explains that the double-weave basket is “very tricky,” because it is woven from the inside bottom to the desired height, then down the outside, and finished on the bottom with no obvious indication of beginning or end. She taught herself by carefully examining a finished basket and finding her own “tricks of the trade.” Her first one—Sealed Fate; Treaty of New Echota Protest Basket (fig. 15)—took her more than a year to figure out. Goshorn

15. Shan Goshorn, Sealed Fate; Treaty of New Echota Protest Basket, 2010. Woven basket: ink and acrylic on paper.

later recalled that a top Cherokee basket maker told her the “man-in-the-coffin” lid shape of her debut venture into double-weaves is sacred and the “most difficult one to make.” The Museum of the Cherokee Indian, in Cherokee, North Carolina, at that time, declared Goshorn to be the fourteenth living maker of double-weave baskets. The outside paper splints of Sealed Fate carry the Treaty of New Echota, which purportedly agreed that the US could move the Cherokee Nation from its homeland to Indian Territory. The inside splints carry names from ninety-five pages of the signatures of Cherokee citizens, disputing the legal authority of the signatories in 1835 at the capitol of the Cherokee Nation in New Echota (now, Georgia, where the non-Natives were the most rancorous and murderous gold-rushers and squatters on Cherokee lands). The splints of the man-in-the-coffinlid are printed with the signature of President Andrew Jackson. Goshorn notes that a Cherokee warrior saved his life at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend (1814), but as president, Jackson refused to even view the protest documents. The US Senate ratified the treaty, and Jackson signed it into law in 1836, less than three months after the signing in New Echota. Jackson even defied a US Supreme Court ruling that could have stopped the bloody Removal.

Color of Conflicting Values In Color of Conflicting Values (fig. 16), Goshorn intertwines her painted version of the $20 bill with the face of President Jackson and the words of his Indian Removal Act (1830). Both cruel and deceptive, the Removal allowed the United States to act under the color of law to wrench Native Peoples from their homelands and herd them on to Indian Territory (most of present-day

16. Shan Goshorn, Color of Conflicting Values, 2013. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper, with gold foil.

Oklahoma, much of Kansas and Nebraska, and parts of Colorado, Missouri, Montana, North and South Dakota, and Wyoming, now mostly owned by non-Natives).20 Countless children, women, men, and entire families were killed on the Potawatomi Trail of Death, Cherokee Trail of Tears, and the Long Walk of the Navajo and many other Native Nations. The wrenching experiences, survivor guilt, and deep wounds of loss, humiliation, torture, and injustice continue to traumatize present generations, nearly two centuries after the original genocide. For this basket, Goshorn combined Jackson’s words and image with the greens and browns of the lush forests of Cherokee homelands in the Great Smoky Mountains and the green, gold, and other colors of money in the heinous Removal chapter of US history.

Feminine Sacred: A Commentary on Domestic Violence in Indian Country Feminine Sacred (fig. 17) commemorates the reauthorization of the Violence Against Women Act (2013), which affirmed Native Nations’ inherent sovereignty to protect their citizens from domestic violence.21 The law recognizes tribal jurisdictional authority to arrest and try all perpetrators. This is particularly important because non-Natives commit most of these crimes against Native women and children, and some non-Natives have moved to reservation land specifically to be free from prosecution though a legal loophole that placed them beyond the reach of tribal police, investigators, jails, and courts. That changed with the enactment of the law, and now Native families have recourse against non-Natives who terrorize them, as some have for decades. Goshorn is one of the few artists to call attention to this part of the law, the reasons for it, and its implementation, all of which are vital in light of expected challenges by those perpetrators of anti-Native violence who want to continue a lawless existence. There also will be persons, ranging from the uninformed to the prejudiced, who commit crimes, report on crimes, and judge criminality; and they all need to be educated, as the US Congress was, about the legitimacy and capacity of Native Nations’ law enforcement and judicial systems, to avoid arduous litigation on the soundness of the law itself. This is another area in which Goshorn’s work helps convey complexity but also makes the issue understandable. Her purple and lavender Feminine Sacred is woven into single diamond shapes, each of which showcases a purple ribbon—symbol of domestic-violence awareness—a pattern that is repeated up, down, and around the basket. She combines splints printed with the law and those with a quote from Oglala Sioux author, educator, and performer Luther Standing Bear, who was in the first class at Carlisle in 1879. “It is the mothers, not the warriors,” he wrote, “who create a people and guide their destiny.”

This River Runs Red Goshorn joined other artists in the exhibit Bring Her Home: Stolen Daughters of Turtle Island (2018), to sound an alarm about the epidemic of Native women being murdered, kidnapped, and trafficked in the US and Canada. Some missing women have been found in urban sex-work districts and in the remote “man-camps” of North Dakota’s fracked oil fields; the bodies of others are discarded in abandoned cars, at construction sites, and under docks and pilings; and still others are never found or counted among the missing. Goshorn’s woven work This River Runs Red (fig. 18) is in the Cherokee water pattern, and its splints contain statistical information in black and white. A white rectangular map shows the Red River, which runs from Winnipeg to South Dakota, and whose name Goshorn says is “heartbreakingly fitting.” She marked part of the river with a blood-red “visual gash” as a reminder of this place, where Native women have been “discarded and seemingly forgotten.” The basket’s top outside rim is red, as is the entire interior, which lists the names of hundreds of murdered and missing women and their

17. Shan Goshorn, Feminine Sacred, 2015. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper.

18. Shan Goshorn, This River Runs Red, 2018. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper with artificial sinew.

First Nations, compiled by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation after the Royal Canadian Mounted Police wrongly declared their cases solved. Pointing to the deep historical roots of this crisis, Goshorn states that Native women, valued as leaders in all aspects of Native national life, often are devalued by non-Native men as “disposable sexual commodities.” Today’s disproportionately high rate of violence against Native women and a judicial reluctance to prosecute these crimes support the theory that the historic devaluation appears to be ongoing. She argues it is time to recognize the women’s humanity and value, and to “put a stop to this terror.”

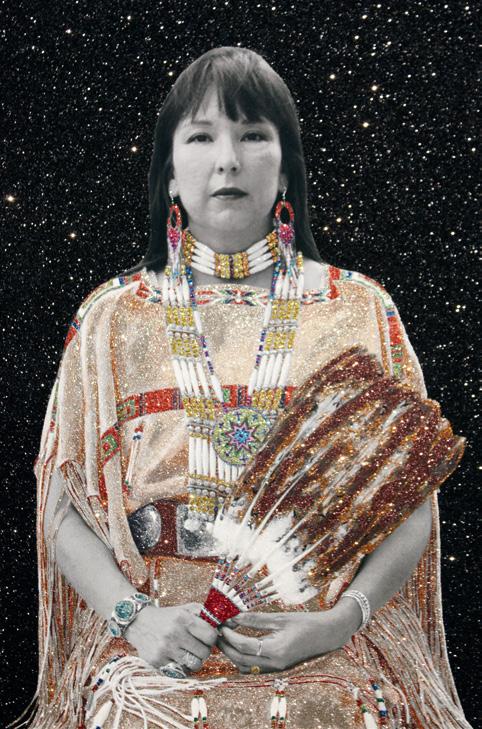

Warrior Bloodlines Series and Not Your Pocahontas Statement In the ten baskets of her 2017 Warrior Bloodlines series, Shan made what she calls an “homage piece to celebrate the strength and courage” of Native women. While she was “inspired” by

her Smithsonian research in 2013, she was taken aback by the way that Native women were described or captioned in the collections, especially by the use of squaw as an identifier. The term is “not a favorable one,” she wrote, but rather a “word for vagina,” indicating the “white newcomer’s perceived use or value of Indian women.” She said she “felt fiercely” that these women “deserved recognition and honor beyond these labels.” One of the baskets in the series features Ta tow ou do sa, a Pawnee woman who was photographed in the 1880s. The basket carries the names of contemporary Native women woven on the inside (fig. 19). It was shown in the 2017 exhibition, We Are Native Women, at the Rainmaker Gallery in Bristol, England, along with Viable 1, a digital composite of a quote about mothers and an image of Jasha, a young mother-to-be “carrying our most precious cultural legacy,” said Shan. We Are Native Women exhibited works by a dozen artists on the occasion of the 400th anniversary of the 1617 death of Matoaka (Pocahontas, Amonute; Powhatan) at Gravesend, Kent, England. Shan’s artist statement, “Not Your Pocahontas” takes aim at the way the historical figure has been distorted in popular culture and made into a fictional character, a cartoon of a “scantily clad Indian princess” who abandoned her people and traditions for her “white man hero, and thus his white culture.” Instead, Pocahontas was “kidnapped” and used as leverage in trade talks with her father, Chief Powhatan. “Dooming a person’s existence to that of a stereotype is worse than never having lived at all,” wrote Shan.

Shan Goshorn’s Photograph Elsie Davis, Carlisle Indian Cemetery There are some women who show up to speechify for the sisterhood, but seldom show up for the sisters. There are some artists who just show up to make a sale. And there are some activists who only show up for the show or to profile against the sunset. Shan is not any of these. Shan shows up. Full stop. She should be taught as a life lesson on the kind of human being we all might strive to become. She has huge ideas and a lot of them, and she takes great care with what others might dismiss as the small stuff. The process and inspiration for her boarding school works and her journey toward the before-and-after pairs—Resisting the Mission; Filling the Silence—are ably detailed by Goshorn and others elsewhere in this publication. I will say only that I have the highest regard and admiration for what she has done, the way she has done it, and the astonishing work itself. Here is the kind of thing she does as she is about the business, duty, and cultural imperative of making art and living life. This is a closing note in the nature of an appreciation to Shan for an act of kindness for my family that she made time for as she was preparing this extraordinary exhibition. She let me know in May 2016 that she had placed a blue bundle, with cedar from the Wyandotte Ceremonial Grounds, at the headstone on which is carved the agency name of my ancestor: Elsie Davis / Cheyenne. Shan emailed a photograph of the headstone (fig. 20), which I had not seen in more than a year. It made me cry—for Elsie, for our family, for our Cheyenne People, for a world that might have been—but also for the loving ways that Shan and others placed bundles and other precious things at Elsie’s headstone, and for the kindnesses in the world that is. Her name is Vah-stah (Washita). She walked on in 1893, not in 1898, as her headstone reads. July 16, 1893, is when she died, not five years later. She was sixteen. The name Elsie Davis was imposed on her when her birth was noted by the federal agent at Darlington, Indian Territory. She was number 131 in Richard Henry Pratt’s record of deaths of January 1, 1904. A scant notice of her death was printed on page 3 of the four-page weekly newsletter of the Carlisle Indian School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, The Indian Helper: “The remains of Elsie Davis

19. Shan Goshorn, Ta tow ou do sa, Pawnee, from the Warrior Bloodlines series, 2017. Woven basket: archival inks and acrylic paint on paper with artificial sinew.

20. Stone marker for Elsie Davis, Cheyenne (misdated July 16, 1898), Carlisle Indian School Cemetery, Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Photo: Shan Goshorn.

were laid quietly to rest in the school grave yard on Monday afternoon. Elsie has been a sufferer for several months and died Sunday afternoon of consumption.”22 Also reported on page 3 were such items as: “The lawn is getting dry.” “The gable end of gymnasium has been rebuilt.” “Capt. Pratt and daughters…are spending a few days at the seashore.” There was news of school visits by two “eminent” men: “sculptor Brown…on his way to Gettysburg to get the details of the General Meade statue he is about to build”; and Frederick Douglass, whose address on the “‘Self-made Man’…has been printed in pamphlet form for our pupils.” Also noted was a report from the Plains: “We are informed that there was big dancing going on at Rosebud Agency, Dak, on the Fourth, and many an Indian made himself poor by giving away all he possessed. The author of our information…seems to think that the Indians are progressing backwards.” This last item was not casual information, as Indian dancing and ceremonies had been criminalized under the federal Civilization Regulations for more than ten years (and would last another forty),and offenders could be branded as “hostiles”and jailed or starved indefinitely.23 Giveaway ceremonies, like the one described at Rosebud, were specifically banned in the Civilization rules, which elaborated that the “excuse that one was a mourner” was “no defense.” That was the policy backdrop for Carlisle and its corporal punishment for children “talking Indian” or “singing Indian” (or for doing anything in the ways of the peoples and families of the hostage-students). At the historic burial place where Vah-stah’s headstone rests, there is a plaque that reads: “INDIAN CEMETERY. Buried here are the Indians who died while attending the Carlisle Indian School (1879–1910). The original Indian Cemetery was located to the rear of the grandstand on Indian Field in 1931. The graves were transferred to this site.” Carlisle’s own records present a more circuitous route from death by foreign disease to finally resting in peace. Bodies were first moved for road construction and transferred at least once more for building construction. It is not known whether some, all, or none of the bodies moved around the campus now lie with or near their headstones. There are still questions, many more than answers. Are all the students accounted for? Are they buried individually or in a mass grave? Are all their body parts there? Might they have been exhumed for the US Army Surgeon General’s Indian Crania Study (1860–1890), which “harvested” more than heads? Today, some Native Nations are seeking return of their citizens’ remains, and the army seems anxious to repatriate all the remains. It is not known to the Native public if there are plans for something else to be done with that hallowed ground. I want you to love Vah-stah, so I will write more about her when some immediate questions are answered. Love her anyway and now. She was sixteen and died of tuberculosis. Both her mothers were gone. Her father had passed within the year. She had close relatives at the school. She also was contagious. Her older brother and her sister-in-law, both of whom were former Carlisle students and new parents, lived and worked there, at the dairyman’s cottage behind the historic farmhouse. Their eldest child was my mother’s mother, who was four years old when her father’s baby sister, Aunt Vah-stah, died. After she walked on, the whole family moved to Indian Territory on Cheyenne land along the Washita River. So, love her now. She’s been by herself for a very long time. And love Shan Goshorn. Perhaps through her good works, good vision, and good words, we can find answers, respect the unanswerable, and fill the silence. Nae’ese. Vooheheva’e.

1. American Indians in the Federal Decennial Census, 1790–1930, Records of the United States Census and the National Archives.

2. “Statement of Vision Toward the Next 500 Years,” from the Gathering of Native Writers, Artists and Wisdom Keepers, Pueblo of Taos, New

Mexico, October 14–18, 1992, sponsored by The Morning Star Institute and The 1992 Alliance.

3. Stephanie A. Fryberg, “American Indian Social Representations: Do

They Honor or Constrain American Indian Identities?” paper presented at “50 Years after Brown vs. Board of Education: Social Psychological Perspectives on the Problems of Racism and Discrimination,”

University of Kansas, May 13–14, 2004. Accessed August 20, 2018, http://www.indianmascots.com/ex_15_-_fryberg_brown_v.pdf

4. “Ending the Legacy of Racism in Sports & the Era of Harmful ‘Indian’

Sports Mascots,” Report of the National Congress of American Indians,

Washington, DC, October 2013.

5. Melanie Mason, “California Schools Barred from Using ‘Redskins’ as

Team Name or Mascot,” Los Angeles Times, October 11, 2015.

6. Spencer Phips, Governor of Massachusetts, Bounty Proclamation on the Tribe of Penobscot Indians, November 3, 1755, cited in Egerton

Ryerson, The Loyalists of America and Their Times: From 1620 to 1816 (Toronto: William Briggs, 1880), 2:79.

7. Richard Henry Pratt, letter to the editor, Army and Navy Journal, March 20, 1911, regarding the Pennsylvania Bounty Proclamation of 1764,

“for the scalps or capture of hostile Indians, for every male above ten years, scalped, being killed, $150; for every male above ten years, scalped, being killed, $134; for every female above ten years, captured, $130; for every female above ten years, scalped, being killed $50,” citing Gordon’s History of Pennsylvania. Richard Henry Pratt

Papers, Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Library, WA

MSS S-1174, box 25, folder 793.

8. “Dakota Man Exposes Vile History of ‘Redskins,’” The Daily Republican (1863) reprinted in Indian Country Today Media Network, April 28, 2013. The text includes the following: “The State reward for dead Indians has been increased to $200 for every red-skin sent to Purgatory.

This sum is more than the dead bodies of all the Indians east of the Red

River are worth.” US Congress, Joint Committee on the Conduct of the

War, “Massacre of the Cheyenne Indians,” in Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War at the Second Session Thirty-eighth

Congress, vol. 3, pt. 6 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865); and US Congress, Senate, Report of the Secretary of War, Sand

Creek Massacre, Sen. Exec. Doc. no. 26, 39th Cong., 2nd sess., Referred to the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs (Washington, DC:

Government Printing Office, 1867).

9. Layana Romanathan, “A Native American Vision for D.C.,” The

Washington Post, April 13, 2007.

10. Commissioner Circular pursuant to Civilization Regulations, 1884, 1894, Letter to Superintendents, January 13, 1902, in Annual Reports of the Department of the Interior for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1902, Indian Affairs, Part 1, Report of the Commissioner, and Appendixes (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1903), states: “Long

Hair Prohibited…. The wearing of long hair by the male population of your agency is not in keeping with the advancement they are making, or will soon be expected to make, in civilization. The wearing of short hair…will certainly hasten their progress towards civilization.

The returned male student…goes back to the reservation…. He also paints profusely and adopts all the old habits and customs which his education in our industrial schools has tried to eradicate…. You are therefore directed to induce your male Indians to cut their hair, and both sexes to stop painting…. if they become obstreperous about the matter a short confinement in the guard house at hard labor, with shorn locks, should furnish cure…The wearing of citizens clothing, instead of Indian costume and blanket, should be encouraged. Indian dances and so-called Indian feasts should be prohibited. In many cases these dances and feasts are simply subterfuges to cover degrading acts and to disguise immoral purposes. You are directed to use your best efforts in the suppression if these evils.” 11. “Our Exhibition,” The Indian Helper (Carlisle Industrial Indian School) 3, no. 82 (March 23, 1888).

12. Richard D. Harnois (Sr. Field Archaeologist) Not Eligible and No Historic Properties Determinations, Oahe Project, US Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District, Department of the Army, United States) to Fern Swenson (Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer, North Dakota Historical Society) April 22, 2016: “Concurrence with Findings and Recommendations of Dakota Access/Oahe Crossing Cultural Resources Survey Report”; John W. Hendersen, Colonel, Corps of Engineers, District Commander, “Mitigated Finding of No Significant Impact, Environmental Assessment, Dakota Access Pipeline Project, Williams, Morton, and Emmons Counties, North Dakota” (July 25, 2016); Standing Rock Sioux Tribe v. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, US District Court for the District of Columbia (Motion for Preliminary Injunction, Request for Expedited Hearing, August 4, 2016); Dakota Access, LLC v. Dave Archambault II et al., US District Court for the District of North Dakota Western Division (Complaint, August 15, 2016).

13. Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples, United Nations, Statement of September 22, 2016. See also, end of Mission Statement, March 3, 2017.

14. Article 19, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, United

Nations General Assembly, adopted (144 in favor, 4 against, 11 abstentions), September 13, 2007.

15. Jo-Ellen Darcy, Army Assistant Secretary for Civil Works, Department of Defense, United States, December 4, 2016; and Notice of Intent to Prepare an Environmental Impact Statement in Connection with

Dakota Access, LLC’s Request for an Easement to Cross Lake Oahe,

North Dakota, Department of the Army, Department of Defense, United States, Federal Register, 5543–5544, document no. 2017–00937, 82 FR 5543, January 18, 2017.

16. Donald J. Trump, President of the United States, Presidential Memorandum for the Secretary of the Army—Construction of the Dakota Access

Pipeline, Office of the Press Secretary, the White House, January 24, 2017. And Paul D. Cramer (Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Army [Installations, Housing and Partnerships], Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Army [Installations, Energy and Environment]), Announcement

Notice of Intent to Grant 30-Year Easement to Dakota Access at Lake

Oahe Dam and Reservoir, letter to Honorable Raul Grijalva, Ranking

Member, Committee on Natural Resources, US House of Representatives, February 7, 2017.

17. David Archambault II, “Taking a Stand at Standing Rock,” opinion, The

New York Times, August 24, 2016.

18. Sterlin Harjo, dir., Shan Goshorn (Tulsa, OK: Fire Thief Productions, 2016), 9 min. accessed August 21, 2018. http://www.sterlinharjo. com/shortdocs/

19. Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American

Indian Nations, edited by Suzan Shown Harjo (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 2014).

20.Andrew Jackson, President of the United States, Message to Congress of December 8, 1829, called for enactment of the Indian Removal Act:

“Professing a desire to civilize and settle them, we have…thrust them farther into the wilderness….and the Indians….have retained their savage habits….” And The Indian Removal Act of 1830, 21st Congress,

Signed by the President on May 28, 1830.

21. Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013, 113th Congress,

P.L. 113-4, Signed by the President on March 7, 2013.

22.The Indian Helper, 8, no. 44, July 21, 1893.

23.Civilization Regulations of the US Secretary of the Interior, in “Civilization” (issued, 1884; reissued, 1894, 1904; withdrawn, 1935),

Solicitor’s Library, US Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.