LETTER FROM THE EDITORS

Notice anything different? A new era of Melisma Magazine has been ushered in, and with that comes a new logo, new members, and even a new room for meetings, but the same enthusiasm for music. If we’ve learned anything during our tenures as Editors-in-Chief, it’s that change is necessary in order to propel something to new heights. With the help of our extremely talented design team, we have overhauled our design language for a slick new look that we hope still stays true to the roots of the magazine.

As for the contents of the magazine, Colin kicks us off with a reflection on how the context behind “bad” albums can turn them into influential classics as time passes. Next, Jack lets us know what constitutes a true sellout musician and how this affects how the media sees them. Sean dives into the world of modern remixes and their implications on the original music. Hannah gets us thinking about how our brains process beats. After that, Rap historian Daniel takes us on a journey through the rise of the guitar in trap music. Alec assesses the impact of leaks on fan culture and entitlement. Resident Weezer fan Jason takes us through the ups and downs of the oft-memed rock band. Andrés with his newfound love for K-pop makes an argument about why marketing in the Korean industry is genius. Resident geriatric Ethan presents a comprehensive history of our beloved Melisma Magazine. Finally, Georgia caps this issue off with their albumreview-cum-comic of Tufts alum Louie Zong’s Windsor Road (did you know that he used to sub on WMFO?).

Unfortunately, not everything gold can stay; at the end of this semester, some of our most exceptional and vibrant members of Melisma will be leaving us for the world beyond the MAB. The sheer impact that these seniors and super-seniors have had on the magazine can’t possibly be stated in words, and we bow endlessly to all of you. And to everyone else, whether you’re picking up a copy for the very first time or capping off your collection: thank you for keeping us alive. It’s been a wild year being your EICs, and we hope that you join us for one final semester in the front seat. So let’s ride (vroom vroom).

- Andrés and Ian

OUR STAFF

EDITORS IN CHIEF: Andrés López, Ian Smith

MANAGING EDITORS: Grace Rotermund, Spencer Vernier

SENIOR EDITOR: Julia Bernicker, Julien Desjardins, Jason Evers, Ethan Lam, Georgia Moore, James Morse

CREATIVE DIRECTOR: Isabel Overby

PRESS DIRECTOR: Liliana Boekhout

DESIGN TEAM: Liliana Boekhout, Mia Rodriguez, Michelle Samigoullina, Olivia White, Anna Zhang

SOCIAL MEDIA DIRECTORS: Ian Glassman, Alec Rosenthal

VIDEO EDITORS: Ian Glassman, Keira Myles, Cecilia Wang, Anevay Ybáñez

EDITORS: Sunny Astacio, Jack Brownlee, Ben Clossey, Hannah Costa, Annika Crawford, Isaac Dame, Jake Rubenstein, Sara Kessel

FOREIGN CORRESPONDENTS: Lucy Millman, Jill Yum

Spoiled Milk...

or Fine Wine?

HOW CONTEXT AND BAD ALBUMS COINCIDE

By Colin BaileyThewidely-accepted notion that music is an art form defined by subjectivity rather than objectivity is vital to the music critic’s work. The music critic seeks beauty and value in every track or album, recognizing that the artist strives to create something meaningful. However, sometimes an overwhelming majority of critics determine that a piece of music is simply awful. Call me narrow-minded or conventional, but I think there’s a certain objectivity in music where something should be labeled bad, because that’s just what it is. The humble reader may say, “but somebody’s gotta like it,” and I agree with them. While many albums that are a rough listen receive terrible reviews from critics at first listen, many notably bad LPs have grown in popularity over the years. The phenomenon of borderline unlistenable albums becoming magnum opuses is a matter of not of the music improving with time, but of context.

First, let’s bring forward a few examples to familiarize ourselves with some god-awful noise. The Shaggs were a rock outfit formed by the Wiggin sisters in 1965 in a small New Hampshire town. The sisters released their debut album Philosophy of the World in 1969 to a commercial

flop. A hodgepodge of offbeat drum patterns, heinous vocals, and notably unphilosophical lyrics defined the album and rendered the band laughing stocks. While many critics bashed the album upon its release, it is now considered one of the rawest artistic contributions to the music world. A day after the Shaggs released Philosophy of the World, Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band dropped Trout Mask Replica, an album that received surprisingly terrible reviews, considering how well-established the band was. Critics did not take kindly to Captain Beefheart’s crunchy “Howlin’ Wolf-esque” vocals lay atop distorted guitar and dissonant chords, saying that the album was one of the worst of that year. Nowadays, it’s considered one of the best of all time.

Moving to more modern examples, the street musician Wesley Willis has released a multitude of unconventional albums, including Rush Hour and Rock n Roll Will Never Die, featuring songs such as “I Whipped Batman’s Ass,” “Lotion,” and, quite possibly his most famous track, “Rock N Roll McDonalds.” Willis’ songs are often defined by a three-chord structure, strained, screaming vocals, and crude lyrics that make little sense. Willis received no critical

acclaim for many years before being profiled by MTV on a program and elevated to stardom. Despite his music lacking a pleasant or on-key sound, his songs strike many today as works of genius. Farrah Abraham’s debut album, My Teenage Dream Ended, marked her shift from being a young star on MTV’s 16 and Pregnant to a serious artist. Abraham’s album features heavily auto-tuned vocals and lyrics about teen angst accompanied by oddly-mixed EDM beats. The album received horrid reviews from critics, with most journalists noting its “weirdness” and “horrible combination of sounds.” In the last few years, though, the album has obtained cult status for its sheer oddness, emotion, and angsty lyrics.

Some may say that these newfound success stories are the result of critics becoming more contrarian and less reliable over time or perhaps the music aging well, but most of the above examples were not good then and still sound awful today. I propose that the newfound respect for these artists and albums is a consequence of the context surrounding their albums or personal backgrounds. For instance, Austin Wiggin, The Shaggs’ father, forced the sisters to play music to fulfill a palm-reading prophecy that

his mother had given him many years before. In addition, Trout Mask Replica became one of the biggest influences for modern progressive and avant-garde rock, and Captain Beefheart was hailed as a genius. Wesley Willis struggled with severe mental health issues, and with this context, a reconsideration of his craft has led many to see him as a genius. Farrah Abraham’s sonically unpleasant album is now revered for its influences on modern-day hyperpop and EDM. No one knew who produced or released these albums at first, let alone their influence on popular music. Critics and casual listeners may not see the albums as sonically enjoyable, but the context surrounding them is often inspirational, and heart-warming, or shows their influence on more refined evolutions of similar music in the future. The music, as a result, shifts from a terrible album to a piece of noisy art. As albums age and their impacts come to fruition, their popular values change concurrently. The context behind the production and influence of albums makes them age like wine or milk, depending on the circumstances.

The Art of the SELLOUT

CREATIVE FREEDOM + COMMERCIAL SUCCESS

By Jack ManiaciThechoice between creative freedom and commercial success has always seemed to haunt rising stars across the music industry. In previous decades, this dilemma was seen as a conflict between an artist and their label or management. It’s often said that the Beatles went out of their way to start their own label and were suddenly able to reach the height of experimentation in their music. My Bloody Valentine were only able to complete their magnum opus, Loveless, in spite of their label, Creation Records, and Mr. Oizo succeeded in releasing more original material after F Communications called his work “unlistenable.” Many still see these conflicts as part of a noble resistance against the greedy industry for the good of music as an art form. The concept of the “sellout” artist accounts for the other side of this story.

The sellout, a musician that makes stylistic changes to their music to match current trends or cater to a particular audience, is framed in opposition to the creative martyr of the past. They are an artist who, according to popular perception, has no serious artistic vision, and who lacks intention in their music, only seeking to make money. But this title can be short lived.

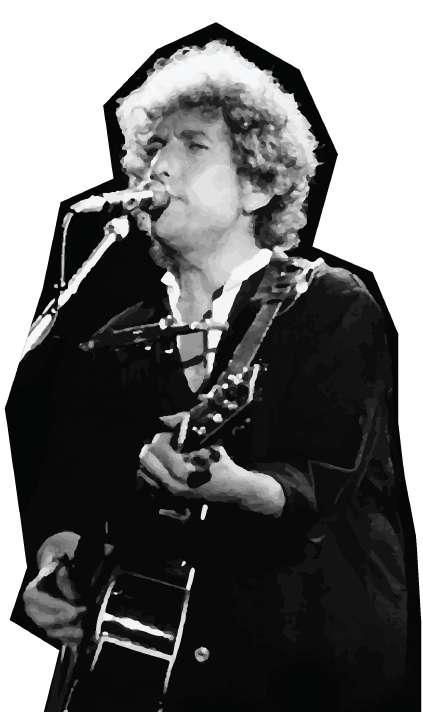

Fans of Bob Dylan were famously dismayed at his switch to electric guitar after he became known for his bluesy folk and protest songs, but that uproar is merely a historical footnote now. This is the inherent problem with the “sellout” label: it makes a normative claim about the quality of an artist’s music based solely on the commercial context of its release. Like the idea of the creative martyr, these claims almost exclusively describe releases that music media has reached a general consensus on.

“Bad” music can come from anywhere, whether it’s released by heavy hitters like Atlantic and UMG or one of millions of independent artists. At the same time, the vast majority of artists that make music for a living, no matter the quality of their music, value commercial success and

will go far to achieve it. In these actions, the progression of the so-called sellout is observable, even if the title shouldn’t carry the implications it does.

So, is there a right way to seek success? In music media, there’s a clear difference in the treatment of artists that get called sellouts and those who don’t. This is evident in Pitchfork’s coverage of Italian rock band Måneskin, who began their ascent to global fame after winning the 2021 Eurovision contest. Their album Rush!, which failed to innovate after their energetic first releases, received a scathing write-up from the publication.

Reactions like this ask what it takes to find Dylan’s route to success? Selling out doesn’t demand a decline in quality, so what’s to be achieved by labeling individuals who reach new heights of success and fame in this way? One could look to Weyes Blood, who gradually transitioned from dark ambient and noise music to critically acclaimed 70spastiche singer-songwriter ballads. Weyes Blood’s music has experienced an even more extreme genre shift than Måneskin, but has clearly garnered a positive reception. The explanation for this is that “selling out”—adopting a more popular style and gaining success from it— cannot explain musical quality. Weyes Blood was likely to be critically well-received whether or not her most recent releases were in her original style, while Måneskin’s style has been out-of-bounds for years.

If artists understand this dynamic of the industry, they can pursue their creative interests without fear of commercial failure. Before Moby’s Play saw him license 18 songs for commercial use, he was unable to find success with his critic-friendly electronic music. Moby’s case provides the perfect example of why selling out doesn’t mean much for perceptions of artistic integrity. Knowing his music would be well-received by the music press, Moby made sure it was heard by any means necessary, his newfound legitimacy making him invincible to the sellout label.

“This is the problem with the “sellout” label: it makes a normative claim about the quality of an artist’s music based solely off of the commercial context of its release.”

“The sellout artist, a musician that makes stylistic changes to their music to match current trends, is framed in opposition to the creative martyr of the past.”

BEHIND

THE BEAT

By Hannah CostaPicture yourself on the green line, heading into Boston on a Friday evening. Look at all of the people wearing headphones or earbuds. Now watch their movements. Chances are, some of them are bouncing their feet or tapping their fingers to mimic the songs playing through their ears. It’s a universal phenomenon—one you can bear witness to in any public space, and almost always as you wait for your train to arrive at the T stop.

Perhaps it’s my tendency to fidget and squirm, but I find myself tapping along to the beat all the time. I notice it primarily when I am in class, where I tap out a rhythm with my feet on the ground subconsciously, not realizing what I’m doing. A majority of the time, I’m replicating the kind of dance that I have done since I was seven years old: Irish step dancing. Regardless of whether or not they’re related to Irish dance, though, all the little taps and beats I make mindlessly throughout the day tend to follow a consistent beat.

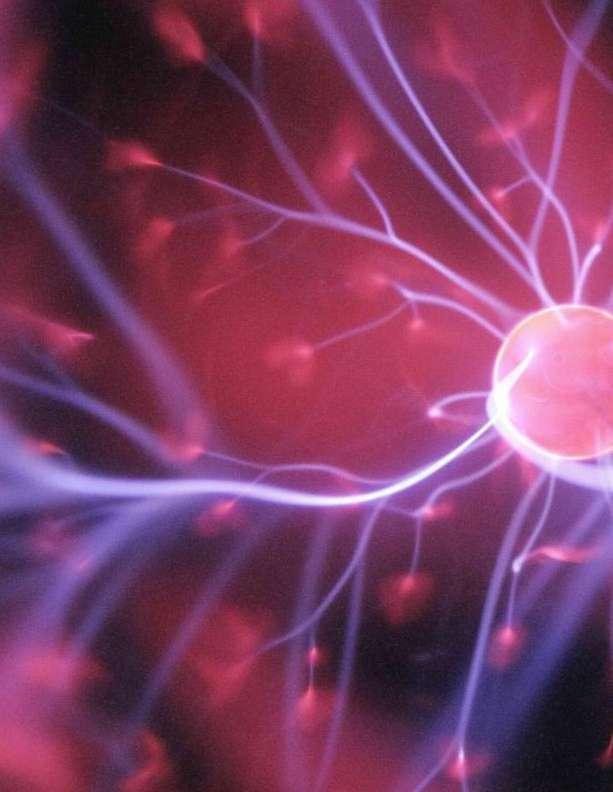

In my Intro to Cognitive and Brain Sciences class, Professor Aniruddh Patel taught me that the mind can perceive or distinguish a beat or musical pattern even without music actively playing. I can’t remember the last time my mind was silent; I constantly have a song playing in my head, half the time it’s an Irish dance tune, and no matter the song, I find myself tapping along and following the beat, whether or not I mean to.

The beat is understood to be a detection of a regular pulse someone can get from rhythmic music. It’s not the same as the feeling one gets when they hear a song they want to dance to—that’s just feeling a groove.

The beat serves as a reference point, both for keeping along to a track’s progression or for music-based movement, that thing we like to call dancing.

It is, rather, an innate sense—in fact, the human brain actually has the framework to sense and maintain a beat.

Some people are actually considered beat deaf. This means they’re unable to follow a beat that is mindlessly apparent to others, and such individuals continuously fail experiments designed to test their beat processing skills. For instance, one day as I was in the car with one of my friends, listening to music, she tried to imitate the way I was robotically tapping my leg to the beat. To my great amusement, she was completely unable to do so, consistently behind the beat, needing to listen to the song in order to produce her own tapping to follow.

Most of us, if we are not beat deaf, will process a beat differently than this. Beat processing is actually a predictive process.

Ultimately, two different factors have contributed to my strong sense of beat. The first is my family’s interest and involvement in music. My dad spent the 80s and 90s in thrash metal bands, where he composed and performed music, primarily as a bassist. He, just like me, is constantly tapping his fingers in some rock drum sequence, and has an incredibly sharp beat perception. I also attribute my years spent in competitive Irish dancing to this skill. Like many types of dance, the music we dance to is split up into 8 counts, or bars, of music. Irish dance uses several different tempos that tend to correlate to different kinds of dances. I have had to sharpen my sense of timing in order to properly perform and succeed in competition (though timing was never difficult for me, thanks to my musical upbringing).

Therefore, if you tap along to a track, the taps themselves are not based off of the sound of the beat they correspond to, they’re based off of a prediction your brain has automatically made about the timing of the next beat in the song. It’s not as much one’s ability to listen to music that contributes to this process as it is an actual cognitive process happening without thought.

While not all music has an official metronomic beat, the vast majority of the music we listen to does, and we pick up on it automatically! Beat-based music provides a better foundation for dancing as well as remembering the lyrics and nuances of the song. We learn songs faster and can replicate them more accurately when they have a strong sense of a beat. This is something you should consider the next time you are waiting for your stop along the T, watching other commuters tap their feet and nod their heads. Behind this mindless task is a plethora of cognitive processes that go beyond a simple physical movement.

The brain is wired to predict what’s to come in a song based on the timing of what’s already happened.

From DJ Turntables to TikTok Snippets:

By Sean Coughlin

By Sean Coughlin

“Good artists copy, great artists steal.” This quote, often attributed to Pablo Picasso, suggests the common view that artistic contributions cannot be truly creative unless wholly original is a misconception. Considering the magnitude of art that borrows ideas and takes inspiration from the stylistic choices of others, the argument unquestionably falls flat. Exciting and boundary-pushing work is consistently conceived through the application and reimagining of various influences, a phenomenon especially present in the modern music landscape. The musical concept of “remixing” began as the practice of DJing became popular. Rather than just playing pre-recorded songs, DJs began to alter and rearrange the compositions in ways that diverged from their origins. A revolutionary step in remixing was the creation of house music in Chicago’s underground scene in the 80s and 90s. DJs took disco, soul, and funk songs and altered their tempo, drum patterns, and other characteristics to forge a more mechanical,

danceable sound. Successive genres expanded the possibilities of remixing. A keen example of this phenomenon is “plunderphonics:” a form of sound collage that mashes several recognizable songs to form entirely new and unique compositions. Notable plunderphonic musicians include John Oswald, Girltalk, the Bran Flakes, and famously, the Avalanches. The Avalanches’ debut album, Since I Left You, is praised within the genre for its expansive and eclectic use of samples. The duo compiled an estimated 3,500 samples to create their magnum opus, hundreds of which remain undiscovered to this day.

Similar to plunderphonics, vaporwave is a genre that emerged in the 2010s incorporating synthpop, jazz, and elevator music into ambient mixes. Originating as a microgenre on YouTube as a microgenre, vaporwave exploded in popularity in the mid-2010s, and continues to hold cultural importance today.

Countless experienced producers started their careers by making music under the vaporwave umbrella, including Oneohtrix Point Never, George Clanton, and James Ferraro.

Sampling, as an extension of the remix, has been highly influential in hip hop production from the 90s onward. Several prolific hip hop producers such as Madlib, Nujabes, and J Dilla, have garnered notoriety for their instrumental beat tapes and albums. Producers have also incorporated remixing into hip hop culture through other non-sampling methods. A popular rap subgenre in the 90s and 00s was created with the rise of the “chopped and screwed” track , pioneered by Houston artist DJ Screw. Screw’s DJing technique involved slowing down a song’s tempo and adding record scratching to “chopup” certain portions of a song. While this style was closely associated with the Houston rap scene, Screw brought his touch to songs from a wide variety of genres. He produced chopped and screwed versions of cuts by D’Angelo, Cameo, Tom Browne, and Ms. Lauryn Hill; even Phil Collins’ “In the Air Tonight” appears on one of Screw’s mixes. Following his untimely death in 2000, the DJ’s legacy was maintained as the chopped and screwed style branched beyond the Houston scene. Many notable hip hop artists have paid tribute to DJ Screw, such as Travis Scott who dedicated the song “RIP Screw” on his album Astroworld to the legendary producer. Despite the many nuanced and exciting methods for remixing pieces of music, their application may not always prove tasteful or innovative. In the age of the internet, online platforms such as YouTube and TikTok have made remixes of songs more widespread and accessible, which promotes many uninspired and derivative mixes. “Slowed + reverb” videos have gained popularity on YouTube as a DIY remix style. Admittedly, slowed-down versions of popular songs paired with anime GIFs can be aesthetically pleasing. However, these mixes require minimal effort to create and are pumped out at an overwhelming volume. This style is clearly derived from DJ Screw’s underground sound but lacks the same level of authenticity and uniqueness as chopped and screwed. Rather than taking years to establish an audience, these YouTube uploads garnered attention almost instantly which minimizes the harder, organic route artists like

DJ Screw took. Slowed + reverb cannot help but feel like a gentrified mockery of the genre which preceded it. Undeniably, a highly influential producer such as Screw represented subculture, struggle, and talent in a way his internet-famous successors never can.

The prevalence of slowed + reverb edits has birthed other lazy styles online such as sped-up edits, 8D audio, and other cheap versions of audio manipulation (Youtube videos such as “‘Redbone’ by Childish Gambino, but it’s being played in the other room” come to mind).

The problem with these edits is not that they sound unpleasant; oftentimes, the opposite is true. Hearing well-known songs slowed down or sped up can be an enjoyable experience when they’re used as background or filler music. The issue with this style of remixing comes, rather, from the lack of deeper artistic expression. Anyone with a baseline of technology can make these changes to a recording, a process that fails to challenge both creator and listener.

Some may assume that these derivative remixes may negatively impact the art of remixing in popular music going forward. One important thing to note, however, is that these videos are not the only remixes being created in the age of the Internet. Algorithms for YouTube and TikTok will promote the most accessible, simple, and lowest common denominator content by default. The fad of slowed + reverb will eventually be replaced by something equally uninventive, while musical phenomena with staying power receive their proper flowers. Genres such as house, vaporwave, and plunderphonics are still incorporated into popular music today. Artists such as Kaytranada, Knxwledge, TV Girl, Vegyn, and countless others have received proper acclaim for their remix-focused musical outputs and will not be going anywhere soon! This demonstrates that paradigm-shifting art and style will reign supreme over substandard, low-effort content. Beyond videos such as “‘20 Min’ by Lil Uzi Vert (slowed + reverb)” are a plethora of other remixes from producers whose approach and style are truly inventive and dynamic.

Leaks and Fan Culture

BY ALEC ROSENTHALIn an age when the internet has become an overflowing cornucopia of content, the relationship between those who consume content and produce it has evolved significantly. Hivemind fandoms now haunt Twitter, eagerly over-protective in their delusional and parasocial haze, and the mindsets of many listeners often disrespects the boundaries of the artists they claim to love.

The heart of fan culture in the 21st century has seen fans turn to engaging with artists as forms of identity, regularly in association with a broader fanbase. While music’s capacity to forge community is essential, the development of “stan” culture—extreme devotion to and support of an artist—has created newage conflicts in considering the relationship between an artist and their fans. When actual appreciation for an individual’s art is outweighed by the desire to use them to curate a specific aesthetic or simply as a personality trait, the fans rob the artist of their agency and claim ownership of their art in order to create external identity. Within “stan” culture, this lack of artistic agency only expands, with artists stripped of their identities and reduced to aestheticization representing a niche group of netizens.

Often, this manifests as entitlement. Leaks have recently been a prominent example of this phenomenon, not only acting as a nuisance to artists but a cultural signifier for fans of all stripes. Fans often use familiarity with an artist’s leaks to indicate how closely an individual follows them and the extent of their knowledge on the artist’s discography, both released and unreleased. Charli XCX exemplifies that struggle, as leaks have become a significant part of her culture as an artist. In-jokes between her and fans, such as the phrase “play ‘Taxi,’” a track off her unreleased, leaked third studio album, are yelled out at shows to communicate to her how much of a fan an individual is.

Despite this, the negative repercussions of leak culture almost completely overshadow the positives.

In an interview with The FADER, Charli described the unfinished state of the album, explaining how fans dictated much of the project’s aesthetic before its leak. “‘It didn’t have a title,’” Charli said. “‘Everyone else just kind of gave it a title; people made artwork. Yeah, it was never really a fully formed thing, so that’s kind of all like the decisions of fans, actually. I didn’t feel like it was my decision to not put it out; the decision was kind of out of my hands because someone hacked me. It just kind of felt like my work got taken from me and it was no longer mine’” (The Fader, 2019).

With the internet’s extensive influence on our lives, pira cy and leaks have become commonplace in the music industry. Individuals access and illegally distribute music by hacking into emails or cloud storage, and songs spread through internet forums and social media. For instance, Playboi Carti’s “Immortal” is an extremely popular leak, circulating around social media sites such as Tiktok and having been published illegally on SoundCloud with over 3.8 million streams as of April 6, 2023.

However, the popularity of leak culture often comes at the expense of the artist, and such a massive invasion of privacy can create long-term negative repercussions for an artist’s career.

Jai Paul’s infamous leak incident, in which 16 demo tracks were published on Bandcamp against his wishes, drove him to take a long-term hiatus from music.

Years later, Paul has since returned to music, officially releasing the leaks as an album titled Leak 04-13 (Bait Ones) and performing at Coachella 2023. Still, Paul said the leak incident frustrated and traumatized him, especially as a result of the widespread belief that he had leaked the material himself. Paul released a statement in 2019, saying “I’d been denied the opportunity to finish my work and share it in its best possible form. I believe it’s important for artists as creators to have some control over the way in which their work is presented, at a time that they consider it complete and ready.”

More than ever, leak culture’s disregard for the artist’s agency continues to show itself in online spaces. In response to fan demand for posthumous SOPHIE releases, Sega Bodega posted on Twitter, “this type of mentality was so prevalent with sophie ‘fans’ it annoys me to this day / *i understand she wanted this, but i want something else so let me have it* / *i understand her

An album leak in 2017 caused Charli to scrap the effort, as she felt that the album had been ruined as a consequence of it being released outside of her control.

desire for privacy but lets hack her for sport*.” Without question, the constant clamoring by fans for unreleased or unfinished material has become a widespread irritation for artists in this digital age.

Still, there have been exceptions to this trend, with fans actively choosing not to listen to leaks, advocating vehemently against them. The leak of Beyoncé’s Renaissance two days before its release exemplifies this, especially due to her own public recognition of her fans’ loyalty to her. Beyoncé tweeted, “So, the album leaked, and you all actually waited until the proper release time so you all can enjoy it together. Ive [sic] never seen anything like it. I can’t thank yall [sic] enough for your love and protection.”

While Beyoncé’s experience displays a loving, communal fan culture, the reality is that leak culture is pervasive, and fans continue to lack respect for the boundaries of the artists they listen to. The question remains: how can we control these ruthless mobs of netizens and inspire them to recognize the problem with prioritizing one’s personal listening experience over an artist’s wishes?

“I’d been denied the opportunity to finish my work and share it in its best possible form.”

“I believe it’s important for artists as creators to have some control over the way in which their work is presented, at a time that they consider it complete and ready.”

It’s December 17, 2021. I’m standing in one of the very top rows at the Barclays Center. People are chatting all around me, anxiously awaiting the main act to take the stage. The lights go dark and cheers flood the arena.

As the voices of thousands of fans ring, the sound of a roaring guitar takes charge while smoke billows over the crowd. Suddenly, booming 808s ring out, and Playboi Carti begins to yell at the top of his lungs. On stage, he seems inhuman; his abrasive screeches sound more like a demon exiting someone’s body than they do rap music being performed. He keeps yelling as the guitarist performs a face-melting solo, transitioning from “Stop Breathing” into another guitar-heavy track, “Rockstar Made.” Despite the utter chaos on stage, the only two people creating this mayhem are Playboi Carti and his guitarist. How did we get to this point? When did guitars become so popular in this once fully synth-driven subgenre?

Trap is a subgenre of hip hop, arguably created in 2003 by T.I. and popularized by trailblazers like Waka Flocka Flame, Chief Keef, and Future. In the early 2010s when these artists were bursting onto the scene, they used blaring synths accompanied by drums and hi-hats to create massive anthems, almost always focused on energy and hyping up an audience. Over the last few years, however, trap music trends have steered toward a more melodic approach. Massive hits like “223’s” by YNW Melly, “Mood” by 24kGoldn & Iann Dior, and “Rockstar” by DaBaby all have guitar-driven beats accompanied by melodic rapping and hooks. To understand the evolution of guitars in trap, we need to go back to 2015, when superstar Travis Scott released his landmark debut studio album Rodeo. In the time since its release, Rodeo has come to be seen as one of the most influential trap albums to date. It combined the sound with other genres like pop, alternative R&B, and neo-psychedelia, which was a concept seldom explored in mainstream trap music prior to its release. Scott incorporated guitars into several songs on the record, most notably “Piss on Your Grave,” which features an extended Jimi Hendrix sample, and “Antidote,” which has a distorted guitar riff propelling the entire song. Scott had used guitars in his music before (see “Mamacita” from Days Before Rodeo), but “Antidote” became a massive hit, pushing him into the trap mainstream and bringing guitar along with it.

Taking inspiration from the more melodic cuts on Rodeo, another surprising pioneer of trap-guitar fusion was none other than Post Malone. His 2016 debut album Stoney featured a number of guitar-heavy tunes, including hits like “Go Flex,” which loops acoustic guitar over traditional 808s and hi-hats. George Cook, director of operations for Dallas rap station KKDA, has stated that hearing that track was when he “first noticed the return of the acoustic guitar” in hip hop (Leight, 2018). Post Malone’s mega-star status helped push trap guitars even further into the mainstream: “Go Flex” currently has almost 900 million Spotify streams and spent 11 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart, while Stoney spent 328 total weeks on the Billboard 200.

100 Chart, while Stoney spent 328 total weeks on the Billboard 200.

Although Rodeo and Stoney had a fair amount of influence, guitars wouldn’t be as prominent in trap music today if it wasn’t for Young Thug. Unlike Scott and Malone’s aforementioned works, Young Thug’s Beautiful Thugger Girls, released in 2017, was not commercially successful. It was marketed as a country album, even displaying Thugger playing guitar on its cover art. Although it wasn’t an immediate hit, the album’s influence is now apparent, paving the way for Thug’s protegés Gunna and Lil Baby to take guitar-based trap to new heights. In 2018, Gunna collaborated with Lil Baby on “Sold Out Dates,” a crown jewel of guitar trap and melodic rap as a whole. The duo contribute some of the finest verses of their careers, coasting on an infectious looped guitar sample while bragging about their immaculate fashion tastes and influxes of cash from sold out shows. In return, Travis Scott recognized the potential of their sound, and recruited Gunna to rap on “YOSEMITE” along with Canadian rapper NAV, interpolating “Sold Out Dates” in the chorus. “YOSEMITE” turned out to be one of the biggest hit songs of the year, coming off the hugely popular ASTROWORLD. After that entered the mainstream, the stage was set for one of the biggest guitar trap hits ever made, Gunna and Lil Baby’s “Drip Too Hard.” The track currently has 1.1 billion streams on Spotify, and it cemented the two as consistent hitmakers with a style that would influence countless up-andcoming rappers including Roddy Ricch, Lil Tecca, and Polo G.

It would be inappropriate to discuss guitar trap without mentioning the enormous impact of the emo rap subgenre. Artists like Lil Peep, XXXTENTACION, and Juice WRLD were catching fire around the same time that Young Thug, Gunna, and Lil Baby began to utilize guitar trap sounds. Lil Peep’s 2016 album hellboy was an early contributor to the sound, with almost every song incorporating a guitar-driven instrumental. XXXTENTACION’s 17 is a blend of downtempo guitars and melancholic lyrics, and gained attention for its stark contrast to his aggressive early SoundCloud works like “Look At Me!” and “Take A Step Back.” Juice WRLD’s “Lucid Dreams” may be the single most famous guitar trap effort to date, garnering over 2.1 billion Spotify streams and spending 48 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart since its 2017 release, peaking at the number 2 spot. Artists like Trippie Redd, Iann Dior, and The Kid LAROI were also heavily influenced by emo rap’s guitar implementation; all of these artists assisted in the rise of trap guitars while Gunna and Lil Baby were making hits in the mainstream scene.

implementation; all of these artists assisted in the rise of trap guitars while Gunna and Lil Baby were making hits in the mainstream scene.

After several years with melodic trap in the center stage, Playboi Carti’s 2020 album Whole Lotta Red shifted the paradigm, taking trap guitars further than ever before. Carti experimented with guitars in the past on 2017’s “wokeuplikethis*” with Lil Uzi Vert, but Whole Lotta Red brought an energy that was very different. Rather than focusing on melody, Carti teamed up with producer F1lthy and opted for a blaring, in-your-face approach, often involving him yelling at the top of his lungs over distorted guitars and pummeling 808s. This album acted as a precursor to the now popular subgenre known as rage music, with rising artists like Yeat, Ken Carson, and Destroy Lonely taking influence from Carti’s style.

While rage is currently the hot topic, there is no telling where guitar trap will venture next. One of the most intriguing musical developments of 2023 has been Lil Yachty’s Let’s Start Here. It’s a psychedelic rock album, yet it comes from one of trap’s most consistent superstars over the last several years. With a trap artist venturing so far from the genre’s foundations, we can only begin to imagine the influence this will have on guitar trap over the next few years. Will we start to see a new wave of rappers trying out a psychedelic, guitar-laden approach? We’ll just have to wait and see. The only thing we know for certain is that guitar trap is continually evolving at a rapid pace, and thanks to experimentation from artists like Carti and Yachty, it’s safe to say that we can expect exciting innovations in the years to come.

There are so many acts that started good and got bad. There’s a million possibilities behind this—they might’ve sold out, lost their drive, succumbed to the dreaded “playing it safe” mentality. Equally, many acts started bad and got good. With time, artists can grow their skills, hone their sound, and improve production. You can probably name a couple bands that fit into either category. But—how many bands start great, get mediocre, get good again, then release albums that can hardly be called music, get good again, get bad again, and finally get good again? How many bands have such a bizarre oscillation in quality? This is the great mystery of a certain polarizing quartet from Los Angeles: Rivers Cuomo’s own Weezer. There are two types of people: those who don’t care about Weezer (>99% of the world) and those who hate Weezer (also known as their fans). After all, it takes a certain amount of fortitude to listen to truly nightmarish “albums” such as Pacific Daydream, Death to False Metal, or the unholy Raditude (on which Rivers Cuomo infamously laments that he “cannot stop partying”). You have to hold a deep love for an artist’s great works to acknowledge (and even appreciate) their worst. Here lies the dilemma of the Weezer fan: enjoying and praising the band’s successes, while also seeking to understand the vision behind its failures. This conflict is at the heart of the question I seek to answer: why, exactly, does Weezer have such an inconsistent discography? The band’s frontman, Rivers Cuomo, has clearly shown his songwriting chops on lauded works like Blue and Pinkerton; how, then, could he go on to release what has been called “the worst guitar music of the 2000s” on Raditude?

There are so many acts that started good and got bad. There’s a million possibilities behind this—they might’ve sold out, lost their drive, succumbed to the dreaded “playing it safe” mentality. Equally, many acts started bad and got good. With time, artists can grow their skills, hone their sound, and improve production. You can probably name a couple bands that fit into either category. But—how many bands start great, get mediocre, get good again, then release albums that can hardly be called music, get good again, get bad again, and finally get good again? How many bands have such a bizarre oscillation in quality? This is the great mystery of a certain polarizing quartet from Los Angeles: Rivers Cuomo’s own Weezer.

There are two types of people: those who don’t care about Weezer (>99% of the world) and those who hate Weezer (also known as their fans). After all, it takes a certain amount of fortitude to listen to truly nightmarish “albums” such as Pacific Daydream, Death to False Metal, or the unholy Raditude (on which Rivers Cuomo infamously laments that he “cannot stop partying”). You have to hold a deep love for an artist’s great works to acknowledge (and even appreciate) their worst. Here lies the dilemma of the Weezer fan: enjoying and praising the band’s successes, while also seeking to understand the vision behind its failures. This conflict is at the heart of the question I seek to answer: why, exactly, does Weezer have such an inconsistent discography? The band’s frontman, Rivers Cuomo, has clearly shown his songwriting chops on lauded works like Blue and Pinkerton; how, then, could he go on to release what has been called “the worst guitar music of the 2000s” on Raditude?

For those who don’t know the history of the Weez—most of you, I imagine—let me just get us on the same page. You can trust me, because I just spent the last six months of my life meticulously listening to and analyzing Weezer’s twenty-one album long discography—especially the bad parts. From the beginning: there’s a pretty universal agreement that Weezer’s best albums come from the 90s, with Blue and Pinkerton. It’s usually a toss-up between the two as to which is considered their best; Blue is remembered fondly for its clean sound and unique character, while Pinkerton is generally acclaimed for its rougher production and deeply personal (if slightly creepy) lyricism. There was a dip in quality in the new millennium with ‘01’s Green, ‘02’s Maladroit, and especially ‘05’s Make Believe, which is often regarded as the band’s point-of-noreturn; many wonder, had this album never been made, if Weezer would still be seen as the mediocre band they’re regarded as today. Red cemented Weezer as meme legends, especially for their “Pork and Beans” music video that celebrates the viral videos of early YouTube. Then: the dark ages. In 2009, Weezer released the accursed Raditude, followed by Hurley and Death to False Metal the following year. In a farfetched attempt to promote Hurley, Weezer collaborated with YouTube rising star FRED. Just when everyone thought Weezer would never make a worthwhile album again, 2014 saw the release of the shockingly good Everything Will Be Alright in the End, followed by White, both of which are fondly considered some of the best.—Oh! and just when things are getting good again, the out-of-touch Pacific Daydream is released, followed by the mediocre cover album Teal (though it

For those who don’t know the history of the Weez—most of you, I imagine—let me just get us on the same page. You can trust me, because I just spent the last six months of my life meticulously listening to and analyzing Weezer’s twenty-one album long discography—especially the bad parts. From the beginning: there’s a pretty universal agreement that Weezer’s best albums come from the 90s, with Blue and Pinkerton. It’s usually a toss-up between the two as to which is considered their best; Blue is remembered fondly for its clean sound and unique character, while Pinkerton is generally acclaimed for its rougher production and deeply personal (if slightly creepy) lyricism.

There was a dip in quality in the new millennium with ‘01’s Green, ‘02’s Maladroit, and especially ‘05’s Make Believe, which is often regarded as the band’s point-of-no-return; many wonder, had this album never been made, if Weezer would still be seen as the mediocre band they’re regarded as today. Red cemented Weezer as meme legends, especially for their “Pork and Beans” music video that celebrates the viral videos of early YouTube. Then: the dark ages. In 2009, Weezer released the accursed Raditude, followed by Hurley and Death to False Metal the following year. In a farfetched attempt to promote Hurley, Weezer collaborated with YouTube rising star F ED.

Just when everyone thought Weezer would never make a worthwhile album again, 2014 saw the release of the shockingly good Everything Will Be Alright in the End, followed by White, both of which are fondly considered some of the best.—Oh! and just when things are getting

eulogy for a rock band

on the and rise and fall and rise of weezer

by jason eversincludes an astonishingly danceable cover of TLC’s “No Scrubs”). The middling Black would be the decade’s final Weezer release, seemingly pointing to another era of mid2000s whateverness.

good again, the out-of-touch Pacific Daydream is released, followed by the mediocre cover album Teal (though it includes an astonishingly danceable cover of TLC’s “No Scrubs”). The middling Black would be the decade’s final Weezer release, seemingly pointing to another era of mid2000s whateverness.

So—what do the 2020s have in store for Rivers and the band? In the past two years alone, Weezer has already put out six major releases (okay, four of them are EPs, but you get the point). Some have been well-received, others not so much. I believe we are currently in an era of Rivers rediscovering what makes Weezer Weezer. The band is primarily guided by Rivers, and with more time to reflect and sharpen his songwriting during the lockdowns of 2020, he has taken to experimenting with the band’s sound once again, bouncing back and forth between chamber and baroque pop, AOR, glam metal, folk rock, progressive rock, and a variety of other genres. This experimentation is the key to understanding the great mystery of Weezer. Rivers isn’t writing to satisfy the fans— he’s writing to satisfy himself, to engage with the music he loves. And of course, that isn’t going to work for everyone all the time.

In 1996, when Weezer released Pinkerton, it was met with an avalanche of criticism. It was panned for its sloppy self-production, which paled in comparison to the sleek work of Blue producer Ric Ocasek. Rolling Stone critic Rob O’Connor lambasted its “juvenile” and “aimless” lyrics, and the magazine’s readers eventually voted it the

So—what do the 2020s have in store for Rivers and the band? In the past two years alone, Weezer has already put out six major releases (okay, four of them are EPs, but you get the point). Some have been well-received, others not so much. I believe we are currently in an era of Rivers rediscovering what makes Weezer Weezer. The band is primarily guided by Rivers, and with more time to reflect and sharpen his songwriting during the lockdowns of 2020, he has taken to experimenting with the band’s sound once again, bouncing back and forth between chamber and baroque pop, AOR, glam metal, folk rock, progressive rock, and a variety of other genres. This experimentation is the key to understanding the great mystery of Weezer. Rivers isn’t writing to satisfy the fans—he’s writing to satisfy himself, to engage with the music he loves. And of course, that isn’t going to work for everyone all the time.

In 1996, when Weezer released Pinkerton, it was met with an avalanche of criticism. It was panned for its sloppy self-production, which paled in comparison to the sleek work of Blue producer Ric Ocasek. Rolling Stone critic Rob O’Connor lambasted its “juvenile” and “aimless” lyrics, and the magazine’s readers eventually voted it the third worst album of the year. A radio interview on the album’s

third worst album of the year. A radio interview on the album’s deluxe rerelease serves as a primary source of fan disappointment; a radio derisively asks Rivers, “I would like to know, why was your first self-titled album so put together and perfect and why was your second album, like… less like that?” In spite of all this, Pinkerton is now considered one of the band’s best albums, proving that often,changing one’s sound is an important part of artistic evolution. And now—the future of the Weez. We’ve already seen an avalanche of Weezer in the 2020s. Some have been excellent, such as OK Human, on which Rivers fuses the band’s classic pop sound with a full 38-piece orchestra. Some releases have been less successful, such as Van Weezer from the same year, which seeks to emulate the hard rock sound of Van Halen. The band just put out the four-part SZNZ series, each of which focus on di erent genres to fit the mood of their respective seasons. It seems that, even after thirty years of musicianship, Rivers is not slowing down any time soon. For listeners of Weezer—fans and detractors alike—there’s a lot to look forward to, so long as Rivers continues to follow his heart.

deluxe rerelease serves as a primary source of fan disappointment; a radio derisively asks Rivers, “I would like to know, why was your first self-titled album so put together and perfect and why was your second album, like… less like that?” In spite of all this, Pinkerton is now considered one of the band’s best albums, proving that often,changing one’s sound is an important part of artistic evolution.

And now—the future of the Weez. We’ve already seen an avalanche of Weezer in the 2020s. Some have been excellent, such as OK Human, on which Rivers fuses the band’s classic pop sound with a full 38-piece orchestra. Some releases have been less successful, such as Van Weezer from the same year, which seeks to emulate the hard rock sound of Van Halen. The band just put out the four-part SZNZ series, each of which focus on different genres to fit the mood of their respective seasons. It seems that, even after thirty years of musicianship, Rivers is not slowing down any time soon. For listeners of Weezer—fans and detractors alike—there’s a lot to look forward to, so long as Rivers continues to follow his heart.

The Genius of Marketing : How Fans Become

When I first started to listen to K-pop around 2018, I would only add the occasional song to my playlist. I was completely removed from any real knowledge of the genre’s inner workings except for the omnipresence of BTS and the spamming of fancam videos on Twitter. However, something changed when I was introduced to LOONA last year, and the rest is history.

I am writing now with a shelf full of K-pop albums and multiple posters on my wall. As a relatively new fan, it has been fascinating diving into this distinct musical world and seeing how the dynamic between artist and fan plays out compared to the Western music industry. The marketing strategies that inform this relationship particularly interested me. As an outsider looking in, it surprised me just how in-your-face yet normalized some of these tactics were. I have noticed three main marketing factors that all fall under the ultimate goal of selling a product viable from day one: creating and fostering a parasocial relationship, recognizing that online content is everything, and valuing both the physical and digital album. While these strategies are not unique to K-pop, they became so heavily utilized that they have become the very foundation of the industry.

K-pop stans are known for their fanatic levels of love and loyalty to their favorite groups and idols, and this is not by coincidence. The record labels behind the groups are extremely calculated in the ways in which they present their artists and how the fans can interact with them. Because of the particular ways that fans can interact with their favorite artists, this naturally leads to parasocial relationships being formed: a one-sided affair where the fan selflessly pours themselves out for the idol while the famous party does not reciprocate anywhere close to the same degree.

One of the ways in which companies and artists develop and encourage parasocial relationships is through dedicated idol messaging apps such as Weverse, bubble, and Phoning. These apps simulate a private messaging

By Andrés López

By Andrés López

room between the idol and fan, so the fan is able to send messages to the artist, but the reality of the situation is that the idol sees the room as a huge group chat between themselves and their entire fan base. So, the idols send relatively generic messages about how they are feeling or how their day went, although they do directly reply to some messages on occasion. Despite this, fans become extremely invested anyway because of the exclusive nature of the content and the prospect of the idol responding to their message. Additionally, companies explicitly promote this kind of behavior from fans. For example, the description of Phoning, the official app of girl group NewJeans, states that it is an app where fans can “Share [their] life with NewJeans [...] through LIVEs, messages, photos, and calendars - and become friends for life.” Clearly, companies want to convince fans that they can somehow become close to their favorite artists despite the improbability of such a thing truly happening. The most outrageous aspect of the messaging apps is that fans have to pay to be able to send and receive messages. Transparently, companies commodify the idol’s online presence, and it works.

"Clearly, companies want to con vince fans that they can somehow become close to their favorite artists despite the improbability of such a thing truly happening."

Another online method of nurturing this relationship is through live streams. Here, fans can connect with idols on a closer level than on the messaging apps because of the more human aspect of seeing someone on the screen. Idols also respond to more questions and comments directly during the live streams because of the constantly flowing chat. These streams are on very accessible platforms too, which makes it easy for a wider audience to get involved. This relationship is also encouraged through one-onone events such as fancalls, fansigns, and hi-touch events. In the case of fancalls, they get to have a short video call with the idol of their choice. At fansigns, fans get to physically chat with the group, get their signatures, and give them gifts if they so choose. Finally, at hi-touch events, fans give the group a high five. Besides the face-to-face aspect of all of these events, what they have in common is that fans usually have to spend quite a bit of money to even have a chance at attending, since a lot of these events use a lottery system to decide who gets to go. For example, for fancalls and fansigns,

signup codes will be included in albums, so to increase one’s odds at winning a spot, one would have to purchase many albums. Moreover, hi-touch events are generally included in concert VIP packages, which are very expensive as well. Nevertheless, the steep prices do not dissuade fans vying to interact with their favorite artist.

All of these modes of interaction thus lure the fan deeper into the group’s rabbit hole. While this might all seem very deceitful, since the idol persona certainly gets commodified and sold to the fan, this is not to say that idols don’t care about their fans. They are being genuine when they thank their fans, but it is impossible to provide personalized attention to every fan, so companies and idols have to come up with ways to imitate that.

When idols are not interacting with their fans in person or over a messaging app, then they are constantly involved in the creation of online content for their group. Companies have recognized that in the digital age, online content is everything, for visibility and audience engagement alike. This approach to digital content has proven effective, given the fervent fan bases of most groups who are active online. On platforms like Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube, groups flood feeds with a constant stream of selfies, vlogs, dance challenges, covers, behind the scenes videos, and more. If they aren’t making something to be uploaded to the group’s page, then they are making an appearance on a radio, music, or variety show or doing a photoshoot for a magazine or a brand collaboration. Additionally, these videos are given official English subtitles upon release or shortly afterward, which creates a wider viewer base.

These kinds of videos also help groups create and capitalize on viral moments, especially ones related to their songs’ choreography (NewJeans again being a prime example with their song “Hype Boy”). Their extremely strong online presence quite literally bends algorithms in their favor. I have experienced this firsthand, as simply viewing or liking a few posts completely changed my feed so that K-pop related posts dominated my screen. This inevitably creates an attitude of entitlement for fans, where they expect content constantly. This attitude even carries over into the music video-related content, with groups releasing multiple videos for one song, including a traditional music video, a performance version, and a dance practice version. All of these forms of content come together to create a seemingly never-ending source of entertainment, which enthralls fans worldwide.

Lastly, the way K-pop companies approach both the physical and digital album is another reason why they have been able to cultivate such passionate fan bases. More often than not, physical K-pop CDs come in multiple versions with different covers, photo books, other inclusions, and sometimes even different tracklists if the release is limited edition. This introduces multiple collectible elements when it comes to buying physical K-pop albums. Because the album is usually not just a jewel case, companies can not only attract fans with the unique packaging, but also include a multitude of extras along with the CD, the most notable one being the photocard. A photocard is a trading card of a K-pop idol, and the sheer amount of cards out there has kept fans busy collecting their favorites. Additionally, companies reward fans for purchasing

"All of these modes of interaction thus lure the fan deeper into the group’s rabbit hole."

albums early with pre-order benefits such as posters or photocard sets. Companies also sometimes fuel this feeling of having to have all versions of an album by releasing an alternate version, such as a digipak, after the initial hype around the first version has subsided.

When it comes to digital releases, K-pop companies have a very intentional process for marketing their albums. In stark contrast to Western artists who largely keep their fans in the dark about when their album comes out, K-pop groups publish a detailed calendar where everything from the tracklist to concept photos to the album itself have a release date and time. While both strategies can help build hype, I have noticed that many fans of Western artists get frustrated when waiting for news about the album to come out, as they only have speculation to rely on. Thus, the only real complaint I have heard from K-pop fans about the rollout is that sometimes it can be published too close to the release of the album, causing it to feel rushed.

K-pop companies also make very deliberate decisions in regard to the composition of the album itself. Espe cially early on, K-pop groups release “single albums,” which are usually two song EPs with a lead single and a B-side. In the modern day, singles and EPs like these usually do not receive physical releases, but they are quite common in K-pop. After a few successful sin gle albums or “mini albums” that serve as a proof of concept, the group can finally move on to a full album. Even after a successful full album, groups will go back to releasing multiple mini albums a year. This strategy of releasing short projects allows companies to hype

up multiple releases per year, bringing in more revenue and keeping the group in the public eye.

There is so much more that I could cover in the idiosyncratic world of K-pop, but the parasocial relationships, strong online presence, and approach to albums stood out to me the most with respect to nurturing some of the most enthusiastic fan bases in music. Companies put idols and their musical product out there so much that it becomes hard to not get invested in their personalities. While writing this article, I wondered what the implications would be for Western music if they took a page from the K-pop marketing strategy. K-pop has been gaining popularity year after year, and it will be extremely interesting to see if any of the idiosyncrasies of the industry spread throughout the world.

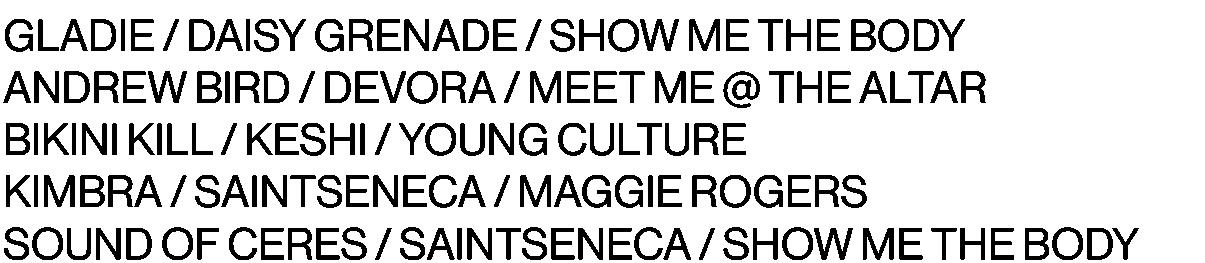

COVERED ARTISTS

SPRING 23

Bikini Kill

Dayglow

Drugdealer

Coco & Clair Clair

Devora

Let’s Eat Grandma

Maggie Rogers

Meet Me @ The Altar

Panchiko

Saintseneca

Show Me the Body

Sound of Ceres

Winkler