14 minute read

WRITING NEW ORLEANS INTO THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION

Writing New Orleans into the

American Revolution

Advertisement

BY EMILY CLARK, CLEMENT CHAMBERS BENENSON PROFESSOR IN AMERICAN COLONIAL HISTORY D. LAMMIE-HANSON, SILVERPOINT DRAWING ON BLACK SURFACE, 2018.

Most Americans don’t know that Louisiana fought in the American Revolution on the side of the thirteen British mainland colonies. Only a handful know that one of the soldiers from Spanish colonial Louisiana who helped win America’s freedom was a man named Noel Carrière, the commander of the New Orleans free black militia.

The absence of Louisiana and Carrière from most versions of America’s founding story highlights one the great paradoxes embodied by New Orleans. In the popular imagination, the city is unique, unlike any other in the U.S.—an exotic, exceptional place that sits outside the parameters of what is typically American, past and present. This is the city that is promoted to tourists and, if truth be told, to prospective Tulane students. The New Orleans waiting to be discovered in the city’s archives, however, is quintessentially American, right down to the role it played in the nation’s birth. If you don’t know that this story and its heroes are there to be found, though, you’re unlikely to go looking for them. Even if you’re a historian. And even if you are a historian and intrigued by that prospect, in order to find them you have to be able to read the French and Spanish documents that reveal the city’s history.

The majority of American Revolution historians have not found themselves on this path. And although I can and do read French and Spanish, I have to confess that I did not go looking for Carrière. I stumbled over him. In the course of a quarter of a century in New Orleans archives spent chasing down the histories of colonial nuns and free people of color, I kept coming across his name. He flitted in and out of the archives like a moth, indistinct and elusive, but persistent. About ten years ago, I realized that I had enough archival fragments to trace him from his birth in slavery in the 1740s to his death in 1804. It’s rare to be able to do that, since the records that fill America’s archives were produced by Europeans and their descendants who were eager to tell their stories but mentioned Africans and African-descended people only in passing, if at all. That was especially true of those born into slavery, like Carrière.

Yet there he was in the archives, again and again. The priests of St. Louis Cathedral recorded him as the godfather and namesake of many enslaved and free infants and adults who shared his African ancestry. Those same priests wrote him into the historical record as an honored witness at the marriages of men who served under him in Louisiana’s free black militia. New Orleans notaries included

him in the inventories of those who claimed him as a slave, recorded his sale to new owners and, finally, inscribed his name on the document that verified his purchase of himself, an act that made him legally free. Another priest documented his marriage, and yet another his burial. A census revealed that he was a barrel maker, and an act of sale revealed that he owned a home and a workshop in New Orleans. Other acts of sale chronicle his purchase of other human beings to labor for him, a sobering, confusing discovery. Spanish governors listed him on the rolls of the free black militia and twice nominated him for medals and monetary rewards for his valor in battles of the American Revolution.

As the bits and pieces from the archives piled up and I worked to make sense of them, I realized that Carrière epitomized many of the things that made America, America. He pulled himself up from nothing. He was a devoted husband and father who worked hard so that he could leave enough to his children to provide them with the security his own father, captured in Africa and enslaved in Louisiana, could not give to him. He fought bravely in the war that granted America independence and promised its people freedom. And, like so many economically successful American men of his time, he bought the bodies of others to serve him. One of the great ironies embodied by America’s founders was their invocation of liberty even as they held others in bondage. In this, sadly, Carrière was no different from Thomas Jefferson.

In other ways, Carrière could not have been more different. His father came to New Orleans in the hold of a slave ship as a small, terrified child taken captive in the chaos that followed the fall of the African kingdom of Ouidah. The African-born commander of the Louisiana free black militia who taught Noel the arts of war initiated him into the great military tradition of the ceddo warriors of Senegambia. The most important people in Noel Carrière’s life, the people who taught him how to be a man, a husband, a father and a soldier, were Africans. He was an American Revolutionary War hero, but he joined that fight as much as a son of Africa as a son of America.

Noel Carrière was a global American founder, a figure who embodies the intersection of New Orleans with the U.S. and the wider world. He was worth looking for.

Clark’s book, Noel Carrière’s Liberty: From Slave to Soldier in Colonial New Orleans, is expected to be in print in early 2021.

A Temple in LITTLE WOODS

BY ALLISON TRUITT ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY

New Orleans’ Little Woods neighborhood stretches out along the southern shoreline of Lake Ponchartrain. Once called “poor man’s Miami Beach,” the area was famous for its fishing camps perched on stilts and piers jutting into the water. In the 1920s, these camps housed restaurants and a few music clubs, but later, only those in Little Woods withstood the onslaught of development planning, including the ambitious East Lakefront Development program proposed by the Orleans Levee Board in 1963. This was the case at least until 1998, when even those camps were reduced to pilings by Hurricane Georges, and in its aftermath when the mayor refused to grant rebuilding permits, citing public health concerns. Today, Little Woods is best known as home to the New Orleans Lakefront Airport.

I had never visited the neighborhood until September 2019 when I learned that Sister Thanh Trang, a Buddhist monk, had returned to New Orleans and established a new temple. After Hurricane Katrina, she resided in a nearby Buddhist center but left the city after a year or so. A few Vietnamese families continued to rely on her to carry out funeral rituals and to provide spiritual guidance and many urged her to return and settle down in New Orleans.

New Orleans is said to be an exceptional city. After the hurricane, the city embraced Vietnamese Americans within this narrative, particularly the New Orleans East neighborhood, centered around Mary Queen of Vietnam Church. But if exceptionalism highlights some stories, it casts shadows on others, overlooking those places and peoples that do not conform to the city’s exuberant storylines. As a cultural anthropologist, I have focused on Buddhist institutions along the Gulf Coast, and how these institutions challenge our understandings of the city and its place in the world. Presently, New Orleans has numerous Buddhist centers, including five Vietnamese temples in the greater metropolitan area, a Thai temple, and other meditation groups. Yet these spiritual communities are seen not of the city, only in the city, reinscribing the persistent trope of Asian Americans as strangers from a distant shore.

OPPOSITE PAGE: SISTER THANH TRANG AT THE BUDDHIST CENTER IN THE LITTLE WOODS NEIGHBORHOOD OF NEW ORLEANS.

How can we instead see Asian Americans as full participants in the process of rewriting New Orleans, inscribing new meanings into the city’s landscape? The large structure that houses Sister Thanh Trang’s Buddhist Center on Edgelake Court today was once the residence of a Baptist pastor. Neighbors claimed he never returned after Katrina and that the building had lay vacant for almost 15 years. Last year Sister Thanh Trang saw a posting for the property just days before it was to be auctioned by a bank. She drove by and walked through an open gate. There she saw a large yard with its towering live oaks. The neighbors welcomed her, and now Sister Thanh Trang and her fellow monk, Sister Thiên Trang, support their . vocation by caring for a dozen or so children after school.

I visited Sister Thanh Trang again in the early afternoon in December. She was dressed in grey robes topped off with a brown down vest, her smile warm and open. While we drank tea, we lingered over stories of her childhood—how she had fled Vietnam in 1981 at the age of eight; how she learned to shop and cook for her father and three younger sisters in Hong Kong; how her mother arrived three years later; how her family was later transferred to the Philippines, a former U.S. colony, to learn American culture. She giggled as she recounted her attempt to reconcile her attraction to Buddhism with her adolescence in America, and how her master refused to believe her when she told him she wanted to become a monk. She later resided in monasteries in California, Indiana, France, and Taiwan. Now she was ready to plant herself, and her practice, in New Orleans.

As our conversation wound down, she led me down the narrow hall, past the newly completed worship hall, through the classroom filled with art supplies, to the backyard. She showed me where she had removed dozens of trees so the children would have room to run, but she left the large oak tree in the front yard standing. Its thick trunk and outstretched limbs may have been standing long before the neighborhood was known for its fishing camps and public beaches. Now rooted firmly in the ground, the tree would shelter the temple in Little Woods.

LET NEW ORLEANS PLAY ITSELF

BY ANGELA TUCKER VISITING ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DIGITAL MEDIA PRACTICES

TOP LEFT: ALL SKINFOLK AIN'T KINFOLK. THE UNPRECEDENTED STORY OF A HISTORICAL MAYORAL RUNOFF TOLD THROUGH THE EYES OF BLACK WOMEN LIVING IN NEW ORLEANS. DIRECTED BY ANGELA TUCKER.

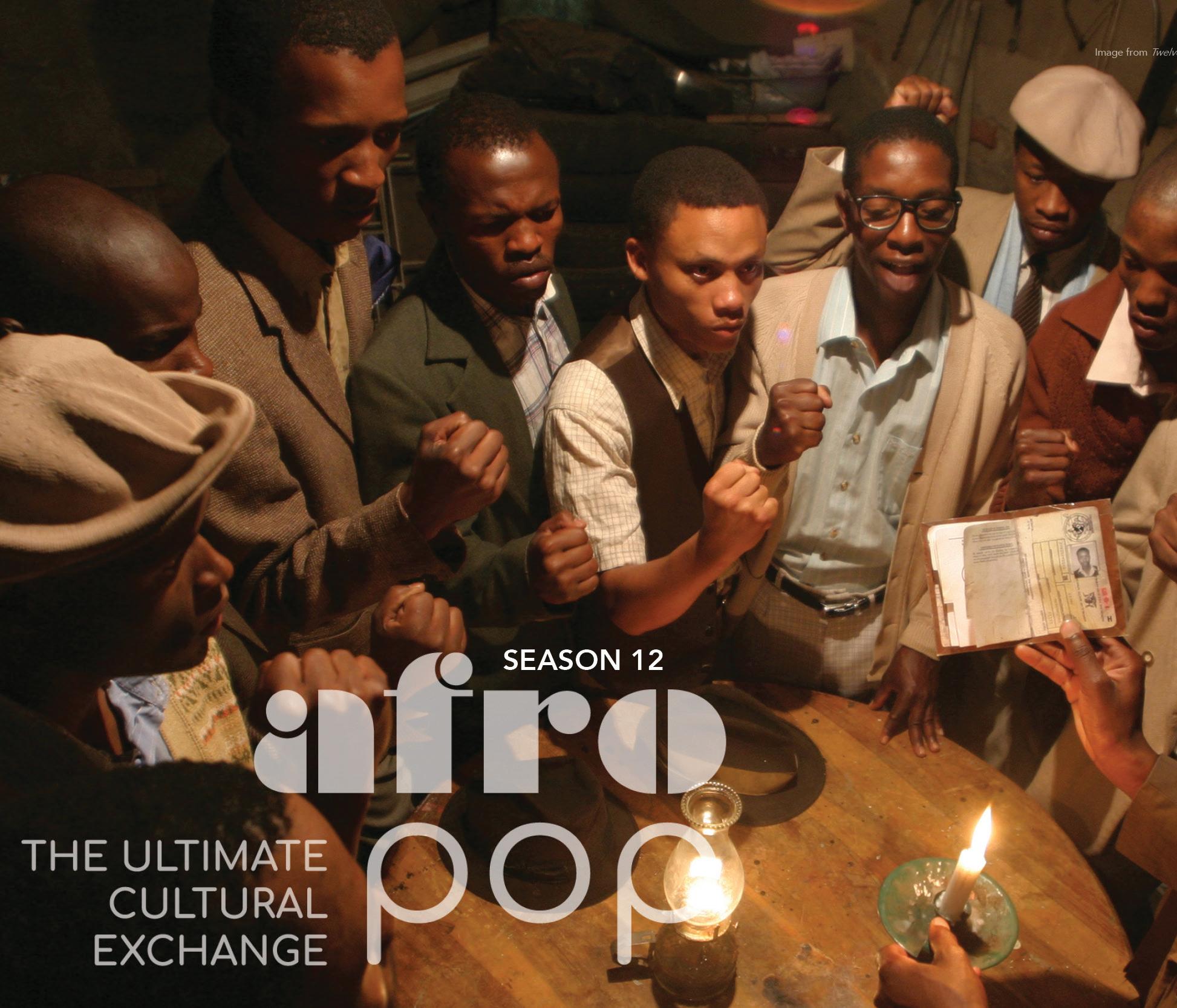

BOTTOM RIGHT: CO-EXECUTIVE PRODUCED BY ANGELA TUCKER, THE DOCUMENTARY SERIES "AFROPOP" DELIVERS ENGAGING AND THOUGHT-PROVOKING STORIES ABOUT MODERN LIFE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA. I t was the end of 2014, and I needed to do a real intake of my life. I was living in my hometown, New York City, and I had hit a wall. I was steadily working on an enviable amount of film freelance jobs, a difficult feat to pull off in this competitive industry, but was beyond exhausted. At that time, I knew I wanted to teach more, to take fewer soul-sucking money jobs, to continue my life’s work of creating media about underrepresented communities, and to live in a place where people valued and appreciated the importance of joy, rest, and self-care. So, with my production company, TuckerGurl Inc., I took the plunge and moved to New Orleans.

When I told film industry people that I was moving to New Orleans, they would often say, “Oh, there’s so much film happening there now.” I would reply with excitement but honestly, I did not know how this perceived boom in film work in Louisiana would affect me directly. My company’s biggest client was Black Public Media, an arm of public television, where I am the Co-Executive Producer for their documentary series “AfroPoP.” That project could be done from anywhere but it was not enough income to hold me for the year. Part of my rationale for moving was a desire to make more fiction projects, especially feature length films. I knew that large studio films like Jurassic Park 3 or series like NCIS: New Orleans filmed in the city but they weren’t exactly posting job listings for independent film directors. I had to dig deeper to understand what these film incentives meant for me.

Louisiana’s film tax credit program has been around since 2002. In layman’s terms, having this program means that productions at a certain price point can get benefits, also called incentives, for filming in Louisiana. States have become production hubs entirely because of incentives, with Georgia and Louisiana at the top of the list creating a new regional hub called “Hollywood South.” In Louisiana, these incentives include filmmakers getting back 30% of what they spend in the state. For larger projects, this can add up to a return of millions of dollars. Obviously, this money has to come from somewhere—in 2019, the state of Louisiana shelled out $150 million toward film tax incentives alone—and for a state as poor as ours, having incentives this extensive, does not come cheap. However, the influx of crewmembers and actors brings increased revenue to local businesses throughout the city.

I quickly learned that these incentives would benefit me in ways I wouldn’t have imagined working in New York City. Even though I was not working on these larger features, my peers were. This steady work allowed me to easily find crew and collaborators

who had outlets to earn regular income. The arrival of studio films and television shows has created what Governor John Bel Edwards called in a recent industry event a “creative class:” a group of people that can remain in Louisiana making a living while pursuing their own passion projects. I’ve been able to meet other independent filmmakers quickly because of New Orleans’ size and culture, and groups like Film Fatales and organizations like the New Orleans Film Society and the New Orleans Video Access Center have allowed me to create a community with invaluable friendships. Most filmmakers get jobs because of referrals and so the more people you know, the better.

What a bigger investment in the Southern film industry and an increased interest in Southern stories have made clear is that the film industry has a growing interest in regionalism. Documentary funders have started the charge by creating new programs like Tribeca Film Institute’s If/Then Short Documentary Program, which specifically funds filmmakers based in underserved regions like the South or the Midwest so they’re able to make short documentaries that are distributed on major platforms like The New York Times’ website or PBS. These funders see the importance of having work made by people living in these regions. Independent feature film

making is slowly following suit but there is still a tendency to use places like New Orleans as a studio space instead of making stories that are specific to the region. Vicki Mayer, a professor in the School of Liberal Arts Department of Communication, attests to this in her book Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans: The Lure of the Local Film Economy, observing that the influx of film-making in New Orleans has “created a para-industry predicated on the city’s malleability as a canvas.”

But many of us are trying to change that. Now armed with an incredible community of filmmaking collaborators, I too am working to create local New Orleans stories in partnership with makers who are indigenous to this community. I have found a new quality of life that allows for more rest and focus. I have been able to make a feature length film, “All Styles,” currently available on Amazon, and also make three short films, one of which, All Skinfolk Ain’t Kinfolk, premiered on PBS’ Reel South in April, while beginning to teach in Tulane’s Digital Media Practices Program. I know this doesn’t sound restful but trust me, it is!

After six years in New Orleans, I have seen more and more filmmakers and small studios bring their film projects to the city and increasingly hire local crew and talent in more decision-making positions. I have a deeper understanding of the complicated and beautiful history of my new city and, therefore, am able to tell richer and complex stories about it. However, until the larger film industry directly funds and distributes more work by born-and-raised Louisiana makers, we still have a long way to go in creating an industry that benefits everyone equally.

UPDATE: I wrote this piece before COVID-19 was in our midst. As the world struggles with how to handle reopening, the film community is doing the same. This summer I was supposed to direct a feature length fiction film that has been postponed. As of now, there are no answers, but every filmmaker knows that people are hungry for content. I remain optimistic that regional stories that have a strong point of view and are grounded will still be desirable to the filmgoing public. I know the New Orleans film community will weather this, but I also know that none of us will be the same.