UKIUKRAQ FALL 2020 ANGUNIAQTUQ HARVESTING

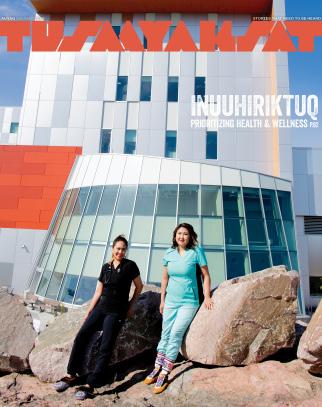

ON THE COVER

Inuvialuk hunter and harvester Dean (Manny) Arey retrieves fsh from his net on the Peel River across from Alfred Semple’s camp in Akłarvik.

ON THE COVER

Inuvialuk hunter and harvester Dean (Manny) Arey retrieves fsh from his net on the Peel River across from Alfred Semple’s camp in Akłarvik.

Publisher Inuvialuit Communications Society

Editor Jason Lau

Guest Editor Michelle Gruben

Art Director Kyle Natkusiak Aleekuk

ICS Manager Tamara Voudrach

Ofce Administrator Roseanne Rogers

EDITORIAL

Storytellers Kyle Natkusiak Aleekuk, Kayla

Nanmak Arey, Renie Arey, Charles Arnold, Brenda Benoit, Robyn Apiyuq Boucher, Corrine

(Kunana) Bullock, Bradley (Oukpak) Carpenter, Stephanie Charlie, Jennifer Costa, Frank

Dillon, Lillian Elias, Douglas Esagok, Nunga

Felix, Colin P. Gallagher, Alex Gordon, Richard Gordon, Michelle Gruben, Lisa Hodgetts/ILH, Jody Illasiak, Melvin Kayotuk, Allen Kogiak, Ellen V. Lea, Paden Lennie, Natasha Lyons/

ILH, Jonas Meyook Jr., Sarah Meyook McLeod, Shane Nakimayak, Stephanie Nigiyok, James Pokiak, Tyrone Raddi, Chris Ruben, Mardy Semmler/IWB, Tanis (Akutuq) Simpson, Billy Storr, J.D. Storr, Margaret Thrasher, Brian Wade, Kaitlyn Wilson/WMAC-NS.

Artists Kyle Natkusiak Aleekuk, Deeanna Benoit Smith, Caragh Crandell, Cora Devos, Nunga Felix, Hunter Franson, Taylor Ipana, Melvin Kayotuk, Mariah Lucas, Tom McLeod.

SPECIAL THANKS TO

Umoja Toronto, Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre (Beverly Amos, Ethel-Jean Gruben) on the Inuvialuktun Playing Cards project.

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

President, Iñuuvik Lucy Kuptana

VP, Tuktuuyaqtuuq Debbie Raddi

Treasurer, Uluhaktuuq Joseph Haluksit

Akłarvik Director Frederick Arey

Paulatuuq Director Denise Wolki

Ikaahuk (Sachs) Director Jean Harry

BUSINESS OFFICE

Inuvialuit Communications Society

292 Mackenzie Rd. / P.O. Box 1704

Inuvik, NT X

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Contact icsfnance@northwestel.net or phone +1 (867) 777-2320 to subscribe or renew. As of this issue, our prices are: $20 CAD (1 year) and $36 CAD (2 years). Find us also on Apple Books.

TUSAAYAKSAT IS FUNDED BY:

Inuvialuit Regional Corporation

GNWT (Education, Culture and Employment)

UBLAAMI! We are pleased to present you with the Fall 2020 Hunting and Harvesting issue of Tusaayaksat Magazine, guest edited by Akłarvik’s Michelle Gruben. Tis issue is special because it reminds us of where we draw strength from in difcult times—tamainni (all the land). We traverse stories from Inuvialuit who use the land and animals fully and completely for sustenance, tools, clothing, income, and art. Aarigaa!

With the holiday season upon us, we begin looking inward and giving thanks for all that we have and all that is to come in the new year. We reflect on the challenges these past 12 months, and there have been many! I would encourage you to be kind to yourself when you think back on this year. Celebrate every win—no matter how small. We as a community cannot expect to be running at full capacity, or demand "excellence" during this time. With so many around the world and now here at home who are struggling, we need to be as empathetic and compassionate with each other as possible. Nukuuyukkun

In honor of the new generations of hunters and harvesters to come, I will end with a photo of my irniq on his first spring hunting trip in Ikaahuk. Liam Elanik—nunami!

Celebrate our land, the fortunes of its bounty and life-giving abilities, and celebrate our people.

Quyanainni, Quviasuglusi Qitchirvingmi, Nutaami Ukiumi Quviasuglusi! Tank you, Merry Christmas, and Happy New Year!

TAMARA VOUDRACH MANAGER, INUVIALUIT COMMUNICATIONS SOCIETY nunami tamainni (Peace on Earth)!THANK YOU FOR TAKING the time to read the latest publication of Tusaayaksat. ICS is pleased to ofer the Hunting & Harvesting edition of the magazine. Tis edition is produced by the hard work and creativity of Tusaayaksat Editor, Jason Lau and Guest Editor, Michelle Gruben of Akłarvik Hunters and Trappers Committee (AHTC).

Michelle is an exceptional AHTC Resource Person in Akłarvik. She is actively engaged in advocacy for Inuvialuit hunters and harvesters, and is also IRC’s representative on the NWT Water Stewardship – Aboriginal Steering Committee.

We feature many harvesters both full-time and part-time, and of course could not feature all, so are planning a subsequent edition in 2021. I hope you enjoy the profiles and stories; I am happy to see several harvesters have agreed to be interviewed, as most Inuvialuit are reluctant to speak about themselves at all.

Today we are living in a society where a lot of food is store-bought, like the flour in your cupboard and tea on the table—but nothing can replace tuktu, qilalugaq, and iqalukpik. Nothing can be so fresh as aqpiit or kimmingnat picked right from the land. Tis is harvesting and hunting.

As we continue to enjoy the abundance of the land, let's respect it as well. I am disheartened to see a lot of garbage left on the land; we should all make every efort to bring back our trash. Teach our children to bring back their garbage as well. Tis land is yours and the responsibility lies within you to be its guardian.

As we reach the Holiday season I want to wish each and every one of

you a very peaceful and enjoyable Christmas season with lots of rest and gratitude for the good country we live in, and the opportunity to live a peaceful existence in a strong democracy. Let’s appreciate the opportunities we could have, and the life that can be lived if we choose to do so.

I leave you with a picture of me and my mom Phyllis out at our bush camp in the Mackenzie Delta living our best life, taken in 1975.

Be safe and stay healthy during this COVID-19 pandemic.

Quviasuglusi

Qitchrivingmi!

LUCY KUPTANA PRESIDENT, INUVIALUIT COMMUNICATIONS SOCIETY

Qitchrivingmi!

LUCY KUPTANA PRESIDENT, INUVIALUIT COMMUNICATIONS SOCIETY

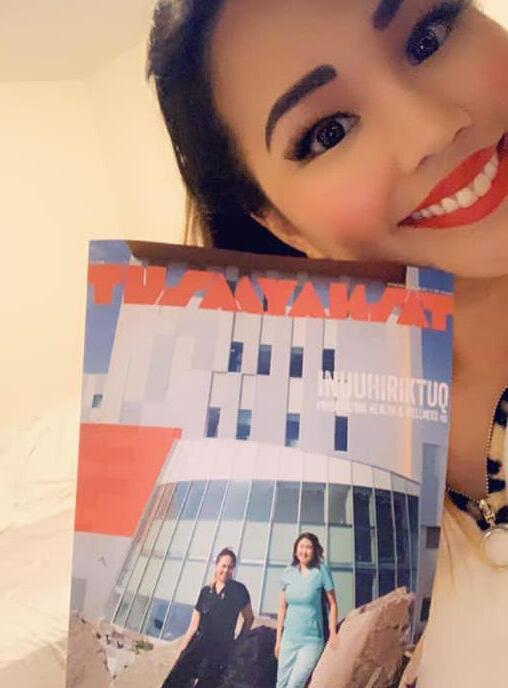

"Hoping to inspire some kids to go to post-secondary school! If I can do it, so can you! Take advantage of all the Inuvialuit funding we get—the opportunities are endless! If any of y’all have any questions about my experience, don’t hesitate to contact me. I’ll be happy to be a mentor for you." —Amber-Joy Gruben

My name is Michelle Gruben. I’m originally from Tuktuuyaqtuuq, but I moved to Akłarvik maybe 25 years ago, when I was a young teenager. I’ve been living in Akłarvik for all these years since.

I grew up with my parents Roger and Winnie Gruben in Tuk. I learned a lot of respect from them and my grandparents—my ataatak Willie Gruben, and my anaanak Helen Gruben. They provided encouraging words and traditional knowledge when I was younger; my jitjii and jijuu did the same.

In Tuk, we used to always go geese hunting and fshing in the spring with my dad and my uncles like Bigman (Robert Gruben) and Dang (Patrick Gruben). They always took me out. When I was a young girl growing up, I was not scared of things. I loved going to Shingle to go fshing, because it all just reminds me Tuk—just on the other side, the ocean. I loved going to Shingle to cut fsh, just to see the landscape, to see no willows. Growing up in Tuk there’s no willows—no nothing. Moving into the Delta, it’s diferent, but I learned to love this community of Akłarvik.

I think I’m lucky to have this job as Resource Person with the Akłarvik Hunters and Trappers Committee (AHTC). I had just happened to go to the store one day and I saw the job posting; closing date was the day I went to the store. That was in March 2009… and I’m still here at Akłarvik HTC, October 2020!

I have much respect for the land, from what I was taught from my anaanak and ataatak, my

MICHELLE GRUBEN, GUEST EDITORparents, and my in-laws. I have much respect for the animals, the land, the water. We need to treat this area with respect for our future generations. When I look at our future generations, I think of my nieces and nephews and their kids they’re gonna have down the road. We still have to provide for those kids in the future—it could be 100 years from now.

As Inuvialuit, we are strong people. We always help one another, and I think that’s my rule here at AHTC: to help [and] assist other members of the community. I’m not here for myself, I’m not here for things I wanna get done. I’m here for what the membership here in Akłarvik or in the other ISR communities [wants]. ‘Cause we all have to work together to get things done properly. So that’s part of the reason I just love my AHTC job. Sometimes I might be stern and whatever, but I think I learned that from my anaanak

I also sit on some other co-management boards as an Inuvialuk representative, keeping in mind all opportunities for Inuvialuit within the ISR.

If it wasn’t for COVID-19, this ofce would’ve been busy with people coming. It’s good to see all these emails and biographies that our people are sending [in]. I’m happy that [we are] gonna put out this Harvesting issue and to focus on Akłarvik, ‘cause that’ll be (gotta use my famous word) deadly! I’m honoured to be part of this Harvesting issue. I’m honored someone thought of my name and I just wanna continue to be the person I am by helping the membership.

I would like to take this opportunity to thank ICS for giving me this opportunity to be Guest Editor. I enjoyed it! As I always say… Stay deadly!

My name is Allen Kogiak. I was born in Iñuuvik and pretty much raised up here in Akłarvik. See, I’ve always been out on the land trapping, and I was pretty much a full-time trapper back in the mid 80s, trapping with my uncle Buster McLeod in Iñuuvik.

We had a pretty good operation for trapping. So, I was doing that and then the prices started to go down. To me, it kinda didn’t seem like a viable option for future, so I left around ’86— that was the last time I trapped.

So, I went back to school back in early 90s at Arctic College in Fort Smith. I only had a Grade 9 education, so I couldn’t really get into whatever I wanted. I took pre-employment mechanics because at that time I was really interested in mechanics, and still am. I was also always on the land, passionate about our animals, our land, our environment, and keeping it clean—so I decided I’d try and take the Renewable Resource Technology program. Tey told me I needed pretty much Grade 12 and really high marks in science.

I really worked hard there. Man… I just gave ‘er! I worked as hard as I could and at the end of the year, after my exams, everything—I came

out pretty much on top of what I needed. Ten I applied and got into the Renewable course. Tat was a really tough course I tell you— you have to be dedicated 100% if you want to do something like that. And I wanted it, so I worked hard. Tere were lots of really tough courses like entomology and zoology… basically anything ending with ‘-ology’, you’re studying!

I graduated, but along the way when I was in college, I wanted to make my name and my face known—that this is what I was passionate about. I got my foot into the door with various federal agencies and other non-governmental organizations that deal with the environment, the land, and animals. During my first year in

Renewable, I went to work for Wood Bufalo National Park as a Visitor Activities Ofcer, where I was taking tourists out to look at bison and interpreting diferent stuf in the park.

While I was in that role, I went upstairs and introduced myself to the Warden Service, sat down with them, and told them what I was doing, and what all my interests were. Te second year, when I graduated, we had my convocation ceremonies on the Friday, and by Monday I was wearing a uniform—a full-fledged Park Warden for Wood Bufalo National Park!

From there, I met one of my co-worker’s dad; he was district manager for Indian and Northern Afairs in Fort Smith. He mentioned they would be creating another position for a LandUse and Water Inspector and asked if I would be interested in something like that. I said, “Yeah, I would!” Tat’s what I wanted to do—to be in a position where I can protect my land. And when I say, ‘my land’, I mean all our land in the NWT. It’s our land; we all have to protect it.

I met with two guys: Floyd Adam was one of them (he was the big head honcho of the whole

Indian and Norther Afairs of all the NWT), and Rudy Cockney at the time was the district manager for Iñuuvik. I got all gussied up—dressed up real nice—expecting a huge interview for such an awesome position with the federal government, but we just sat around having cofee and talking all morning!

Rudy said, “Well, when can you move?” And I said, “Well, I need at least 2 weeks to put my notice in.” He said, “Okay, well, 2 weeks from now the movers will come to your house.”

Sure enough, 2 weeks later, boy, we were on the plane to Iñuuvik and I was happy because I had left home in 1986. I got on with Indian and Northern Afairs as a Land Use Inspector.

After that, I promised my wife that we’d be in Iñuuvik [for only 5 years], ‘cause she’s from the Yellowknife/North Slave region, and she wanted to go home. 5 years went by just like a blink of an eye. Keeping my promise, we left, and I went to Yellowknife and ended up working at the mines. Ten, from there, I moved to Tulita for about 5 years, then back to Iñuuvik, then here in Akłarvik.

"It's like: Guardian. You see, I think throughout the world, there’s this 'Guardian' program. Not only Inuvialuit have it; there's places in other countries like Australia. There are 'guardianships' all over, doing the same thing as what I'm doing. It’s not only us—it's almost every culture. Some BC Indigenous peoples have the same thing. There's all over like this, and it's important because it gives us a heads-up for you to have somebody there in case something happens [to] make sure things get rectifed and reclaimed. So, it's awesome, man." —Allen Kogiak (Photo from Joint Secretariat – Inuvialuit Settlement Region)

When I got home, I started working as an employment ofcer upstairs for Akłarvik Community Corporation for about 2 or 3 years. Last year, I seen the ad for this position, Munaqsiyit Monitor. And it sounded good! Just right down my alley because it’s a position where I can be a part of protecting my land—and this is my land here in Akłarvik, the Delta. Tis is our land; this is where I grew up. Tis is where I learned to trap and fish.

So, I applied on this position. I wasn’t the first choice, I'll tell you that—but it was eventually offered to me. I signed on Oct 20th of last year, 2019. Now, I’m in a position to be able to play a pretty big part in protecting our land. Once I got hired on, they brought us all for training and I took this community-based monitoring program.

Tere is one Munaqsiyit Monitor in each of the ISR communities. As a Munaqsiyit Monitor, I am the eyes and ears for our people, for the land. I look after and look out for the land, the animals, the water, the environment. Any problems or any concerns in those areas, people will come to me or they’ll call the HTC ofce.

In the past, during jiggling season there were always people leaving fish behind, leaving mess behind. Last year when I got hired on, I said I’m gonna be monitoring all these sites. We got Jackfish Creek right across from here, we go up the Akłarvik River a little ways, you got Mar-

tin’s and a little further is Jim Firth. You come back this way, you head up North towards the coast, you go to Six Miles, and also to my granny Martha Dick's. Tat’s where pretty much the fishing areas are, for jiggling. People always left fish, you know. So, I put signs up to remind people not to leave messes behind at those sites and I’ll patrol them.

I also monitor the ice road with Max Kotokak. He’s our other Munaqsiyit Monitor in Iñuuvik. So, we meet up half ways just before you get to Mackenzie—just passed Clovis and Darlene’s camp on the road. We meet up there checking for garbage, accidents, or if somebody broke down. It could be anything. And last year, when they were doing gravel haul, there was lots of problems with vehicle breakdowns. Holy, man, talk about huge oil spills! When they break down, antifreeze spills. Antifreeze is the worst because if an animal sees it, they lick that antifreeze as it kind of tastes sweet to them. So, they keep ingesting it because it tastes good— but it's poisonous, bad for them.

As a Munaqsiyit Monitor,

I am the eyes and ears for our people, for the land. I look after and look out for the land, the animals, the water, the environment.

When hunters and trappers notice something that’s out of the ordinary when going out, they know they can contact me and make sure we do something about it—or we get the right, proper authorities to go out there. As soon as they see something on the road, they’ll call me up right away or message me on Facebook and say, “Hey, Allen, you should check this out. Tere’s a truck broken down. Look like a big huge spill or whatever underneath.” If I know it wasn’t there yesterday, I jump in my car and take of. I always have my camera—I got to take pictures and recordings. I’ll document everything on paper and do reports. Tis way I can get it right of to the NWT Spill Line. Once you get it to them, it’s out of your hands and those guys will contact the proper authorities and something will be done.

Another thing, too, is: say if somebody broke down, they know to call me. I got my Ski-Doo here and everything all ready. I just gotta keep gas handy in case something happens late at night. Ten I can just fire up my Ski-Doo and go pick up somebody or look for somebody. So, yeah, my job is wide open—but mostly we’re looking after the environment and the animals.

I love my job. It’s something I'm passionate about. Another thing I'm really passionate about too is our environment—with global warming, climate change. I always try to keep up to date with that.

Any chance I can get to go to these conferences is really important to me because we’re going through quite a bit here in Akłarvik. Especially with thawing permafrost, because the whole town is on [it]. Now it’s turning to water—but what happens after that? Tere’s no more stability. Te damage is done. It’s taking place and there no stopping it. Tere’s nothing we can do. Here in Akłarvik, our roads used to be solid and now it’s water [and] not solid anymore. Houses are shifting; banks are eroding really fast. Once that ice pops out and it’s exposed to the outside environment (like the air, sun, heat), there’s no stopping that from slumping too.

Tis is stuf that’s really important to me; I'm really happy I am in this position. It's awesome and you get to travel on the land. It gives me a good opportunity to be out and mostly to protect our land—that’s the best thing. Te main

thing is: our land is important because it provides for us. It provides food, it provides shelter, and everything. We have to really be diligent and keep our land clean as much as we [can]. Our animals as well—we have to manage ‘em well.

I have done a lot of things, I worked in various jobs along the way—but my passion was always trying to protect the land and get a job like that. All this was made possible through my education. Tere was hard work and sacrifices, but it paid of. Te places I’ve been, the training I've received, the people I’ve met… it's awesome and I get to protect our land. I started with my education. I mean—I worked hard, and I stress that to kids today. With your education, you might have to give up a few sacrifices. You might have to go away from home, but it’s gonna make you a better and stronger person. If you're like me and you get your education in something you’re passionate about, then you do something your passionate about. You’re gonna go far and do it good.

The Munaqsiyit Program was launched on October 19, 2019. Monitors throughout the ISR have been hired for the program “as the eyes and ear of the land”. They include: Max Kotokak Sr. (Iñuuvik HTC); Frank Wolki (Paulatuk HTC); Allen J. Kogiak (Akłarvik HTC); and Ron Kallak (Uluhaktok HTC). Sachs Harbour and Tuktoyaktuk HTC Munaqsiyit Monitor positions are both vacant. The crew holds responsible duties that include going out on-feld, collecting and observing data, and connecting a communication gap for Western Science and Traditional Knowledge. The program is growing and is always encouraging more Inuvialuit participants. (Words by Joint Secretariat – Inuvialuit Settlement Region)

My name is Brian Wade. I am 35 years old. I have been married to my wife Carmen Wade for 7 years and we have been together for 14 years. We have two beautiful children: Abigael, who is 11, and River, who is 2. My mother is the late Lena Gruben, and my father is Ron Wade.

I was raised by a single mother, visiting my dad down South only for a few weeks every year. My mother and I lived in numerous places throughout my childhood, which included Yellowknife and Iñuuvik. We moved away from Iñuuvik to Calgary when I was 11 years old because my mother wanted me to pursue a higher quality of education. I later moved back to Iñuuvik when I was 21 years old, following the oil patch work. At this point in my life, I was a city boy through and through. I knew nothing about hunting and the land. I always enjoyed fishing, which kept me somewhat connected.

Living in Calgary throughout my teen years meant I sacrificed the crucial years of learning how to hunt, navigate, and be out on the land— the years when boys usually get their first caribou, or learn to call geese. All of this was sacrificed because I was away from the North, and away from my older cousins and uncles who would have taught me.

When I moved back to Iñuuvik and established myself in my early 20s, I had a job, family, and children, but I felt like I was still miss-

ing a part of me. I tried filling that void with alcohol and weekend fun. Tis only made the emptiness worse. It wasn’t until I was 30 years old that my wife surprised me with my own snow machine. Tis gave me the tool I needed to go out and explore. I recall sitting there looking at a map, remembering key location points, and taking of—no fears, excited to be out on the land. Now that I look back, I may have been a little naïve to the dangers, but it all worked out in the end. I stayed on the main trails and learned them, the bearings, lakes, and rivers first. Once I learned the main trails, I was set. From there, I learned the fishing seasons: when to fish for loche, coney, and lake trout. Tis gave me fulfillment that I had never felt before. I remember my first trip to Sitidgi Lake 45km east of Iñuuvik, and thinking how cool it was to be that far out of town, with nobody around, and having the whole lake to myself.

Once I had the fishing figured out, I wanted to learn to hunt. For one whole year—all four seasons—I tailed one of my older cousins: learning the harvest seasons, knowing what to look for, how to read tracks, and how to process our kills. For giving me the knowledge and taking the time to teach me, I will always be grateful to him. He gave me the gift of providing for my family, and skills I can pass down to my children. I remember the first moose I killed by myself. My mind went blank. I completely forgot

A good hunter doesn’t envy anybody, or get jealous of anybody else’s catch; instead, they encourage and congratulate each other because there’s an understanding that everybody gains if we all share with each other.

how to gut and process the animal! Luckily, instinct kicked in and I was able to quarter it.

In my opinion, a good hunter or harvester is someone who understands the cycle of life. Te animals and fish that are sacrificed to nourish and feed our people. A good harvester is someone who not only hunts for their immediate family, but hunts for anybody in their community. A good harvester doesn’t get caught up on the -30oC weather, but understands that people are hungry and need the meat, sacrificing their frost-bitten cheeks to fill freezers. A good hunter doesn’t envy anybody, or get jealous of anybody else’s catch; instead, they encourage and congratulate each other because there’s an understanding that everybody gains if we all share with each other.

Let’s fast forward 5 years: my wife, children, and I love being out on the land. We built our own cabin out at Imaryuk (Husky Lakes). We eat only meat that we have harvested. For over 2 years we have not bought meat from the stores! Our diet consists of moose, caribou, geese, and fish. We have a respect for the land and the animals we share our land with. It is very important to us that we learn together and explore as a family. I make every efort to teach River and Abigael everything I know and everything I learn. My wife Carmen gives me the time I need to harvest, and the support I need when I fail. I have a great job that supports this lifestyle we live. I am truly grateful for all who are in my life.

I enjoy giving out what I harvest. It gives a purpose to going out and harvesting. Te smiles and gratuity you receive when you give someone meat or fish is rewarding; you gain a sense of accomplishment. I try to give to the Elders, single mothers, and people who don’t have the ability to go out and harvest first. If somebody asks, though, I will never say no. I was taught to give the Elders the “golden goodies” like the tongue and heart, and to give away clean meat without hair, not the wounded meat.

Having the tools, guns, supplies, and gas to go out and enjoy these activities isn’t cheap. Te initial cost of buying these machines is outrageous, and then there is maintenance and upkeep on top of that. It takes a lot of creativity to aford these luxuries. My wife and I have come up with a few ways to support our adventures. One of these ideas was selling battered fish

plates made from local fish. I go and ice fish, set net, or rod and reel for the fish, then fillet and cook it. My wife cooks the sides and does deliveries. We make the batter and tartar from scratch. It has worked up to this point, and people seem to really like it. Te other way we supplement the costs is by selling moose dry meat. I was never traditionally taught to cut and make dry meat; I just picked up a knife and started slicing. I like the traditional taste of it, so I just use salt and hang until it is dried. Once again, people seem to like it. Being creative is key to being able to go out and enjoy our land. Times have changed—you cannot just up and go. It takes financial planning and a lot of resources to make a trip possible.

If COVID-19 has afected us in any way, it has given us more time away from town. It has secured funding from the governments to give everyone the means to go out on the land. Tis has encouraged us to spend more time out there. We love being on the land. It doesn’t even matter what we are doing—exploring, hunting, fishing, or just spending time in our cabin. Te life we live in town is only so we can have the means to live our life out on the land. I love the sites we have seen, the memories we have made, and the lessons I’ve been taught. I am grateful to my mother for raising me to be the man I am today, my family for being beside me no matter what, and my Inuvialuit culture that guides and teaches me daily.

Being an Inuvialuk, and feeling the fulfillment from being out harvesting, travelling—I would encourage everybody to try and get away from town as much as possible. Our ancestors travelled and socialized together, living of the land, living among the animals, and having a balance with the universe. Tis is what is ingrained in our souls. Te land heals all wounds and helps sort a confused mind.

Our land—the ISR—is so vast. At a glance it could seem so empty, but if you stop, look, and listen to it, it will feed your body, your soul, and your mind.

My name is Margaret Trasher. I reside in Iñuuvik, but am originally from Tuktuuyaqtuuq, NT. I was raised in Tuktuuyaqtuuq with my family of 8—my dad, mom, four sisters, and one brother.

As far as I can remember, at the age of 5 years old, I can reminisce of when I first started learning and watching my parents harvest our traditional foods. My dad, Lawrence Trasher, was a very well-known fisherman in Tuktuuyaqtuuq. He had dedicated most of his time and daily routine to his fishing in the summer and fall seasons. Tere were times when he and my mom would take us down to the smoke house where they would both cut and hang dryfish. Oh, how I

miss those memories to this day! My dad would take fish to Elders of Tuk and those who needed the food. His wise words always come back to me. He would say, “Help and always give to Elders.” I am thankful for watching them and learning by their side. If it weren’t for them passing on the Traditional Knowledge, I would not know how to harvest the whitefish today. Now I do the same as they did: make dryfish, give to Elders, and teach my children—or just let them watch and play.

I had grown to love to harvest a second traditional animal during the late fall seasons of September. We would head to our fall/spring camp known as Galiptut (shallow waters). Tere,

Me at the age of 18-19 years old on the land hunting; me and my dad beside our smokehouse; our camp Galiptut (shallow waters) outside of Tuk.

My dad cutting whitefsh at a fsh-cutting contest; my recent photo of a jumbo whitefsh I had cut up; my daughters helping down at the harbour, fxing our table for fsh.

I would hunt our ‘wavies’ [snow geese] and speckled belly geese— better known as yellowlegs. Tis I had learned from my late father, Lawrence, at the early age of about 12 years old. I can remember I had started shooting the 410 then. I mostly used the 410 to practice on closerange geese and until I got the hang of shooting guns; then, I switched to 20-gauge shotgun. Ever since the first day I learned to shoot geese, I was hooked. I loved to help harvest for my mom and dad, and still do to this day. I had not only learned to shoot, but also watched my mother make geese dinners—plucking, gutting, and cutting the goose every way to make soups and roasts. I hope to pass

on the knowledge in my memory to my children, as they now watch and learn from me when I prepare foods and cook. My most memorable time would be watching my parents cut up both fish and geese to prepare them for our dinner. Now, I show my kids the exact same routine as my parents had shown me.

Honestly, I think that’s what makes a good harvester and hunter: having the patience and the will to learn, and to listen to those who can show you how to prepare and harvest our traditional animals. To this day, I know how important it is and how much it means to our way of life. It is how we survive, how we live, and it’s a part of who we are as Inuvialuit. Our El-

ders have left us to pass on what we know, from making foods and clothes to not wasting anything we harvest. We were taught to not waste our animals and foods. Tat is one thing I'll remember that my dad told me: "If you kill it, then you will eat it, so don’t kill animals for fun. We don’t waste food.” I took that very seriously. If you harvest and you cannot use something, then give it away to those who can make use of it.

With my knowledge, I try my best today to help my mother and others. Tis past summer of 2020, I finally had the time to make dryfish and harvest for my mom. We sure had fun. We also took my daughters to the same spot where I used to play

at their age. We would collect wood for fire, fix tables for cutting fish, cut, dry and hang fish, as well as have picnics. It made my heart full of joy and happiness because I know how much I loved to play on that Tuk beach as a kid, and now my kids enjoy it. Eight years have come and gone since my dad passed, but with his knowledge carried on, I can still hear his words and see him harvesting fish and geese. I'd like to say thank you Dad and Mom for showing me how to live our ways of life. I am very grateful and very thankful.

One thing I'll remember that my dad [Lawrence Trasher] told me: "If you kill it, then you will eat it, so don’t kill animals for fun. We don’t waste food.” I took that very seriously. If you harvest and you cannot use something, then give it away to those who can make use of it.

I’ll never forget what my parents taught me: animals are our life and food.

I grew up in Akłarvik, NT. My early memories are of West Channel hunting visitors from other camps in the early 80s. All camps were flown to on airplanes—I was just a kid then. My earliest hunting experience was shooting a caribou with a 3030. My dad and his friends helped me—it was a very exciting time. My dad, my late brother Lawrence, and I would also go to the coast every year to hunt polar bears. I miss those days. My parents have since passed away from cancer.

My dad would always talk about Prudhoe Bay, so I moved to Kaktovik, Alaska in ’96 to work at an oilfield. It was the best experience of my life; I was known to my employer as the toughest [person] they ever saw!

I now have spinal stenosis, which prevents me from working. I missed the oilfield dearly, so my friend Steve and I started a tour company taking people to see the polar bears. We get people from all over the world—we even took a few Canadians.

I was always intrigued by photography, but never got into it until we purchased a couple of Nikon cameras last year. I’ve since taken a lot of photographers to see polar bears. I now love

to photograph our polar bears and anything else that shows our beautiful land. I know what it’s like now—photography is very interesting!

We now live with COVID-19. My parents would have never known if they were still alive—they would have still lived in the bush! Because of COVID-19, we’ve lost all of our clients this year—which afected me and my business hard. It’s not just about the money, but about taking people to see the bears. COVID-19 also afected my family hard. We would travel to Akłarvik to visit every year, but now we are not sure how long it will be before our next visit.

We have to respect our Elders. Tey are the ones that teach us to know where to go and hunt. I’ll never forget what my parents taught me: animals are our life and food. It makes me feel really good to be a good hunter and to respect the land. I’m very, very sorry for our young people; they need to get out more. Tey still do, but things are very, very diferent now. We used to visit Elders a lot. It is very important to show the young people how to properly harvest food from the land and talk about weather changes.

We are now in a diferent world, but I will continue to take my pictures of the land.

Hello, my name is Shane Nakimayak. I am 33 years of age, and I am from Paulatuuq, Northwest Territories. I have 3 kids—my daughter, Sophia (the eldest at 8), and my two boys, Glen and Devon (2 and 1).

Growing up, I was always out with my grandparents, who adopted me at a young age. Te most memorable time in my life was when my grandfather made us a home in the treeline (Bekere Lake Lodge), neighbours to Lac Rondevue (owned by Billy and Eileen Jacobson).

Before the cut of of hunting caribou for sport, we were always out from August to October. Tose were the best 3 months anyone could ask for if you loved being out on the land—especially if it was in the treeline.

My first encounter with animals was with caribou when they were migrating North one year. We jumped in our boat with a 25-horsepower Mercury and waited for them to start crossing the lake. We watched for at least an hour before the sport hunters made their choice, so we let them pass until the chosen tutku were far in the lake. From there on, it was easy

picking. Tis would happen a few times more as we had multiple hunts going. I was too young to help with the meat, but as I watched, my grandfather taught me how it was done step-by-step—never missing a moment. Seeing all the parts that came out of the caribou was a big mystery to me, like the bible, kidneys, heart, and liver, so I had questions all day for my grandfather! He said that these are the parts that make a good meal—not just the meat and fat—so eat what you think you can. If not, someone else might want it.

My current relationship with the animals is very respectful and caring. I’m out on the land every season, starting with geese hunting, char fishing in our big lakes, whale hunting up North of home (which I just got hooked on), then in the fall for caribou for a few months until freezeup, then up the river for char again.

Hunting and fishing here never stop! If you want to be a good hunter, listen to what the Elders have to say about the land and the animals because their advice is crucial to the next generations. Nothing has changed about the land and how

hunting is done, so again, listen to the Elders. We don’t have much of them now who paved the way for our future.

If I was asked if COVID-19 afected my hunting and fishing, I would say no because if you’re out on the land, you’re most likely to be safe and sound as long as you have heat, food, and water.

My advice for future hunters and harvesters is to just be out there whenever you can, because it’s the biggest part in our tradition and culture. It’s in our blood and, most of all, it’s our way of life. Some may want to go to college or find a new place to live. I went through this in my teens but realized that I was meant to be here with my grandparents where my whole life was spent. Still today I’m living those days over and over, which I also want my kids to do as well, because living this world today, there is no use leaving home [in the North] when isolation is not a bad idea.

So, take care of the land and the ocean, and they will provide you with a blessing of good country foods... quyanainni and have a good winter my fellow Inuvialuit!

My advice for future hunters and harvesters is to just be out there whenever you can, because it’s the biggest part in our tradition and culture. It’s in our blood and, most of all, it’s our way of life.

I was born in Iñuuvik on June 18th, 1998 and was raised in Tuktuuyaqtuuq. Tere’s no other place like home where I would have wanted to be brought up.

I first started fishing and hunting when I was 8 years old; that’s when I started working with fish, watching my uncle Chris cut fish down at our smokehouse, and make pipsi (dryfish). I would have always gone to see if there would be any conies for me to practice on to try and learn how to cut fish. After that, that’s when I knew that I would be working on fish every year; I knew how to work and clean the fish later through the years!

Goose hunting is another thing that I love to do. When it comes to hunting geese in the spring, I spend most of my spring living out on the coast. Goose is one of my favourite country foods that I harvest of the land for myself, my family, and others who can’t hunt. I got my first gun when I was 9 years old, and that same year, I started hunting geese with my uncle Chris. He also showed me how to hunt seals and drive boats.

Te year I turned 18, I finally got the chance to go caribou hunting. I caught up to some other hunters, and they said that the caribou

weren’t too far from where we were. I followed one of the hunters about 35-40 miles away from town to where the caribou were. When we got to the caribou herd, I did not know what to shoot—bull or cow—so I watched my partner to see what he shot. After he got his caribou, I started to shoot the one that I thought I could; I managed to get 6 caribou for my first time hunting them. After we gathered our caribou on the lake, I watched as my partner skinned and butchered them. Since it was my first time hunting caribou, I did not know how to skin. After he was done skinning two caribou, I started on my own and got the hang of it after my second one—with a bit of help and guidance. Ever since that day, I have loved hunting caribou and working with the meat.

I’m very happy with what I’ve learned through the past years! I’ve travelled with many people growing up—I picked up a lot of diferent hunting skills and a lot about the land. I’m very thankful for those who took their time to teach me everything that I know today. With what I’ve learned, I can now pass it on to our younger generation of future hunters and providers for the community.

I usually just use what comes to mind when I’m going to draw, and I always study the animals closely and get a good look at the animals. Tat way I would know the look and form of what I’m going to draw.

I mainly work on fish during the long summer. Ten, when fall and winter arrive, that’s when I’m busy hunting caribou. I hunt caribou in the fall time before freeze-up so that we’ll have enough meat to last us until wintertime comes. Ten, I harvest the caribou throughout the winter for myself, my family, friends, and Elders. When spring arrives, that’s when I start to hunt and prepare geese for the summer and coming winter. I am now the main provider for our family, and I always try to think of others who may not be able to hunt, or single parents in need of help.

Te thing I love about hunting is that I know my family, friends, and others will be eating well. It’s really hard for our people to not have our taste of food from the land. Growing up, our country food is usually our main food that we eat. I will always try my best to help others in any way possible; that’s just the way I was brought up. “Always share and help others no matter what, sharing is caring!”

To be a hunter and provider, it takes a lot of years until you know every hunting and sur-

vival skill, as well as the landmarks. It takes a lot of learning and listening to be a hunter [and/or] provider. I don’t look at myself as the best hunter or tell anyone that I’m better than them. We are all equal—that’s how I look at hunting or being a harvester.

Tis year, with COVID-19, I thought that it was going to be difcult to go out on the land, but it really created a lot of opportunities, like funding for gas and food. I have never seen so many people out camping during the winter and spring before, which was a good thing, because it kept a lot of people away from town. Having all of these seasonal on-the-land programs throughout the year makes it easy for our youth to get the chance to learn our traditional and cultural ways of living, as well as survival skills for the future when they do start to go hunting on their own. It puts a big smile on my face when I see our younger generation wanting to take their time to learn and wanting to be out on the land more.

To be a hunter, it takes a lot of years until you know every hunting and survival skill, as well as the landmarks.

My name is Jonas Meyook Jr., from Akłarvik. My father was Jonas Meyook Sr. from Alaska and my mother was from here. I just like hunting—I’ve done it all my life with my parents and other people like Tom Arey Jr., Bob McKenzie, and my brothers.

My father started hunting along the coastline from Alaska to here, but mainly from Herschel Island to Shingle, Running River, into town here, and up in the mountains. He hunted down to the coast where it’s all flat country. He said that’s where he could see his animals, and then track and chase his animals. So, that's how I got into hunting. I ended up staying down at Herschel Island for a few years with Bob Mackenzie and others, coming back with my relatives, like Tom Arey. From there on, I started hunting on

my own and working for a while. Once I got a Ski-Doo, I started hunting and I never stopped. Me, I started hunting wolves and wolverines— big game. I never hunted small game after that. I stick with wolves, wolverines, grizzly bears, sheep, and muskox—grizzly bears in springtime, polar bears in falltime. One day, if I ever get a goat, then I’ll fulfill my dad's dream because he hunted all the animals. He used to always come home with diferent animals from [around] Herschel Island, trapping all winter foxes and rats.

You’re always learning more when you’re following animal tracks. Where the animal goes, you gotta go! When I chase animals, I go up and down the Richardson Mountains, where sheep stay. We walk up on top there. I really don’t care for travelling the river—me, I go up in the mountains because it is safer. My life is up in the mountains and down towards the coast; I don't really know Delta as good as the mountains. We go up and down rough high mountains. Like steep mountains and that, you could [go] vertical and full blast. Sometimes, you fly 20, 30 feet— just ski jump!

I hear wolves howling all the time. Once you hear wolves howling, we just start howling back after that. Sometimes, we’ll be traveling and see wolf tracks, so we start calling them. Next thing, you hear ‘em calling back! Tat's when we find out where they are, and we try and track ‘em down after that. Once they howl, they're gonna want to know who you are, too, so they're gonna come and check you out.

Just as long as you howl, like a dog noise— anything like that. Every time a wolf herd is together, they all know each other’s howls. If they hear you make a diferent howl, they're gonna be like, “Hey, you're diferent! Diferent territory. We don't know who you are.” Wolves are always territorial.

Te first time I [howled] was when I was hunting bear. I knew there was wolves up in the mountain, so I kept howling. I knew the wolves was there so I brought a couple of friends of mine the next day and I started howling. We watched 10 wolves running towards us! Every time wolves get close, the pups always start getting closer first—about 100 yards, maybe—and the adults wait for a while. Ten, they start circling you.

My friend Robert Archie and Tomas Gordon there—they got kind of nervous. [One of them] started loading up his rifles and said, “Holy! Look at that—you called those wolves right to us.”

I told him, “Well, what you’re scared of? We got the gun. We got Ski-Doos. We're hunting.”

We hunt a lot of wolves mostly to keep the wolf population down. Most I ever got one year was 19 wolves! One Elder told me—quite a few years back—that they shot about 60 wolves in between here and Canoe Lake, in order to save our Porcupine caribou herd. Tat's how come we got a large porcupine caribou herd, ‘cause they were hunting wolves. Te thing about hunting wolves is keeping the caribou population in check— that's the thing people don't think about.

One thing I really don't like is when there's people in other communities cutting of their people from hunting caribou, because of declining [population]. If those guys hunt their wolves, they wouldn't have declining caribou.

When my mother was alive, she used to always have first choice at my animals. Like sometimes, I'll bring two wolverines or a bunch of wolves home, and I'll show her. She says aarigaa, then I know she likes it and you know, it's hers! She always had first pick [on] them there and then. Nowadays, I deal with taxidermists and people who are wanting that. I never sold a wolf since my mother passed away, [but] I just sold an Arctic wolf to a woman in Alaska after putting it on Facebook. I told them I just about kept it!

Some would say polar bears and Grizzly bears are the top animals, but once a wolverine gets full grown, they're the top animals of the North. In the moonlight, Bob MacKenzie saw the biggest polar bear... and a wolverine chasing it away from a carcass! He said, “Wolverines are the top animal of the North.”

Wolverines have really sharp claws because them, they climb trees. Ten the jaws: they always clamp up on their nose and start biting around. Sometimes they find wolverines up in the trees and willows and shoot them, when you're up in the hills.

Most wolverines just take anything away from wolves. Nowadays we hear stories with Billy Archie about how wolf packs are getting bigger, because they said he see wolf tracks just about wide as a Ski-Doo! Tat's a lot. Me, I caught about 20 this year. Most of them come

from Alaska—big herds down that way. Tey always follow the caribou when they're coming from the Alaskan side. Wolves come from the coast, too.

One of my friends Dale calls me qavvik (wolverine). Because I travel alone, he said, “Yeah, you're just like a qavvik.”

We knew there was wolves on the other side in the canyon. Sheep started running out, so I started howling. All the while, I'm skinning my two sheeps. I howl for a while; I skin for a while. An hour and a half later, in that video, the wolves’ grey heads start popping up. You could see where they’re running down at the end. About 7 to 10 of them started coming up. I start barking just like a dog—that's going to make them really start coming. [My common-law] was making that video. She was counting the wolves, elbowing me, and saying, “Look at their heads!”

If you guys saw that video on Facebook, what you don't see [is] on the right side of us were six more that came up [much] closer than what you saw! All together [there] must’ve been about 20 of them!

Some viewers just didn't like the video. Other than that, people said: well, this is what we do up North to save our caribou, [we] know hunting and this is our life. If it wasn't for hunting wolves, we wouldn't have any caribou.

Just be safe and make sure you know your areas when you're traveling. You gotta try and learn your snowbanks, which way the wind is going, and traveling around the ocean. Sometimes you get “white-out” and drifting, and that's what really buggers you up! Sometimes you don't know the wind switches.

When you're up in the hills, you gotta know where the main trail is. I would be on the main trail before it get[s] dark, and we always try to stay on the main trail. I'll say: don't get of the trail until you see something—because if you get caught in a storm, you're trying to find your way around and you got two trails now. Two trails don't make as good as one trail. Stay on the trail until you find wolf tracks or something, then start expanding out to try and track it.

When I go travel around the country there, I always try to stay away from them deep creeks and stay on the main trails until springtime. You could go pretty well anywhere because there's lots of snow. Te one thing about snow is that, when you're going traveling, it's got to be packed, and it'll hold the Ski-Doo.

Up this way in the Delta, the snow is still soft, so you're sinking through. You got to be more careful about that for traveling with tundra and snow, because we have “rock country” towards John Martin towards Sheep Creek; we have tundra country from Cash Creek Timber. I call Canoe Lake side “tundra side” towards the coast, and it’s more safe to travel down that way.

Never run out of shells. Always have extra shells for bear or something when you're walking back to your boat, especially in the fall times.

Listen to Elders when you go hunting. Te Elders will tell me: if you go this far, you'll see this and that.

I like traveling. If I had a million bucks, I would buy 10 Ski-Doos and a truck, and then travel around, ‘cause the winter is my lifetime.

Winters feeds a lot of hunters and trappers and give people a good life. 20-30 years down the road when there's no snow, some people gonna be wishing, “Boy I wish I drove a SkiDoo,” or something. Traveling with Ski-Doo—at least I got to do all that. And [I’m] still doing it, still trying.

I am from Tsiigehtchic, NT, and I grew up in Akłarvik.

Every summer, we would travel to the Yukon coast (Shingle Point) and do our harvesting for beluga whales, fishing, caribou, and also berries. My most memorable part is being at Shingle Point. Growing up there every year with all the families sharing and looking after each other and traveling together—everyone was always busy. What makes a good hunter or harvester is someone who listens to their parents or Elders when being taught. Be patient—you don’t need to rush. Because you’re on the land, you have all the time to learn.

COVID-19 didn’t afect my hunting and traveling; it actually helped me get on the land more with the funding available for gas and groceries.

My advice for the next generation is to keep teaching your kids so they can keep the cycle going.

You don’t need to rush. Because you’re on the land, you have all the time to learn.

I grew up in a small community of 500-600 people called Akłarvik. I have lived here most of my life as most of my family are from Akłarvik. Growing up, I have always been around my dad, uncles, and cousins, hunting and harvesting caribou and geese. As long as I can remember, I have always observed from the blinds and ran to get the geese after they were shot. Around the age of 12 was when I started doing the shooting.

At that same age was when I started learning how to cut, hang, smoke, and store fish. My late Ama Alice Husky taught me everything on how to work with fish. Being at Shingle Point cutting and working with fish with her is my favourite memory of harvesting fish.

Alice Husky was my great-grandmother. She came everywhere hunting and fishing with our

family. She was a great person to our whole family by helping everyone with cutting caribou for drymeat right up until she couldn’t do it anymore.

For me, the pandemic hasn't given me any problems with harvesting animals this year. I still went out to our family camp by the Mackenzie River for geese, to Shingle Point for almost a month to harvest fish, and continued harvesting fish when I got back home to Akłarvik on the Peel River.

When hunting and harvesting any kinds of animals, I think you need someone to teach you to do everything—not being taught the same thing many times, but having the knowledge to learn once and let it stick with you. Someone has to teach you in any way to do anything with harvesting native foods. You need to be taught about where to go, whether it’s in the mountains, the river, lakes, or the flats. You need to be taught how to work with whatever meat it may be and to store it properly. Tere's going to come a day that you will have to do it all on your own.

My name is Sarah Meyook McLeod, I’m from Akłarvik. My parents are Jonas Meyook Sr. and Sarah Meyook Sr. I grew up down at the coast mostly and then moved to keep in and out of town—in town for a few months and then back out on the land. I mainly grew up around Shingle Point and Herschel Island, so I used to travel down that way until my dad passed away. We go back and forth lots.

Growing up with my mom, siblings, auntie, and uncles, I [learned] how to work with seal. My dad used to have seal nets; him and my uncle used to have two or three out and they used to catch quite a bit of seals. We used to skin them and eat some, but it’s been so many years now. Tey used to hunt caribou and we used to always fish, following the char coming up this way. We used to have camps here and there in the Delta. After we were done harvesting for whale or fish at Shingle, we used to come this way [and] fish until just about middle of September, all the way up to close to town.

We used to [work with seal] at Herschel. We used to buy fur. My dad and my uncles, they used to hunt seals and once in a while they used to get walrus. We used to skin seals, dry them and sew with them, but it’s been many years since. I never work with seal for years... Oh, golly, maybe 25 years or longer?

PHOTO by TOM MCLEOD

PHOTO by TOM MCLEOD

After my parents died, I haven’t been to Herschel for years, [since] 2006 or 2005. I went down with couple of friends and my sister because we had a memorial for my auntie down there when she passed; [of] course we wanted to go. Tat’s the last time I went. I did get ofers to go down to be a cook and that, but since I started working at the Akłarvik Health Centre, I keep turning [them] down.

My two older boys work there now as park rangers. I keep telling these guys: I gotta try to go down one of these times. In the springtime? We fish. We used to whale, and we used to do lots of stuf like that. I never been to Shingle point, too, for about 4 years. After my mother passed, we go down there couple of day trips to fish for a little while.

Other than that, we’ve been just traveling in the Delta. We trap and hunt goose and caribou; once in a while we’ll get wolverine or wolves. Before I started working (it’s going on 4 years now since I started), I travel quite a bit on the land with my kids. We go hunting, fishing, picking berries.

I like to pick berries. I don’t know [if] I’m the best but I pick quite a bit because I always try to bake with it. We do go places here and there to pick cranberries. I hardly pick blueberries. I like to pick aqpiit (cloudberries) ‘cause we travel around quite a bit, go places here and there to pick them. And people always ask me: “Where's your secret spot?”

One Elder, before she passed, kept telling me about Fish River and said: “I used to pick berries in there. Tere’s lots of aqpiit, lots of cranberries.” After 15 years, we finally found that spot this year—and we did pick quite a bit of berries from in there!

I show my kids [these spots] because I like my kids and grandkids to travel with me. Tey come camping with us ‘cause we built a cabin at Police Cabin (on Police Cabin Lake, on the border between NWT and Yukon) for my berry picking, where you can just land, walk up, and pick aqpiit. I don’t like rushing back, so we all have a place to stay for a couple of days, go pick berries, and check around for caribou.

I always tell them: any little channel, we’ll take and follow. "Let’s just go look around, and we’ll check places.” And that’s what we do. I al-

ways let ‘em be my driver and go places to look for berries.

When [my son] Tom was small, there was one place my uncle showed me in a lake at Yaruvaluk. He’d said: “I’m gonna show you where’s a berry place. Don’t tell people! Don’t give your spot away.”

Tom was small; he must’ve been about 8 years old I think. And he seen all these aqpiit. Now we call it “Aqpik Heaven”, ‘cause it was so much berries that first time we start picking. He said: “Holy, lots of aqpiit.” I said: “Yep. Your ataatak showed me first this place.” He named it Aqpik Heaven so that’s what we call it when we go there. ‘Cause you could just [get] on the land, walk a little ways, and it was just covered! But these past few years wasn’t too much.

So, I show my kids few spots and where to go to pick berries. I take them all over. I pass it on to them so they could know where to go.

When we go out on the land, we always ask them to come with us just so they can learn how to work with stuf. [My granddaughters] already know how to shoot [a] gun. We always try to take them out with us, ‘cause we hunt lots of beavers and muskrats too.

We still go out on the land lots. [My husband Ian] traps minks and I go out with him; we help him quite a bit with trapping. He also follows me to Shingle, so we travel and harvest from both sides.

Nellie Arey—that’s my sister—she’s been all over. She really knows that way, and all the [Inuvialuktun] names. I take my other sister and brother out—show them and try to tell them: “Watch the Land.”

My boys, they show [others] how to skin and stuf like that. My oldest son, when he gets his fur, he always try to make his daughter skin; she’s pretty good at it. Last fall, [a] few hunters got caribou and I guess that girl didn’t know much how to skin and cut it, so my oldest granddaughter Gabrielle would show her how to skin and where to cut the caribou. Tey said: “Oh you know lots!” And Gabrielle said: “Yeah, my dad taught me, my Aaka and my Poppa taught me.”

So, we try to teach our kids and our grandkids. I tell the grandkids: “Blood can’t hurt you, you could wash it of, it might smell for a little

while but it’ll always come of.” I always try to teach them how to cut meat and stuf like that. But these kids, they always really work with meat, fish, rats, and muskrats.

I don’t touch foxes or lynx—always let them do that. ‘Cause the time I seen bugs on lynx and... they’re pretty big ah? So I said: “I’m not touching those!” I don’t skin those but I skin anything else. I said that’s [Ian’s] job to do (and he does it).

And that time I was really picking cranberries up this way (up Black Mountain) and we call that place “Cranberry Heaven” because there’s so much cranberries! I was really picking cran-

berries—not paying attention to nothing. Usually I look around a lot, but not this time. Tere was so much berries so I wasn’t paying attention. Good thing [Ian] came down to me, ‘cause he said: “You know there’s a bear behind you?”

Tere was a Grizzly bear behind me not far from me! [Ian: He was just picking berries behind her!]

Yep, so holy—I sure opened my eyes! He said I should shoot up in the air to scare him... Never even moved. [Ian: We had a pile of lumber up on the hill there; it just sat on that lumber and laid down. We had to shoot up on the gravel to make that gravel pop up and get it scared.]

Sometimes I get so carried away from just picking. But now when we go out berry picking, we always look out all over us!

He named it Aqpik Heaven so that’s what we call it when we go there. ‘Cause you could just [get] on the land, walk a little ways, and it was just covered!PHOTO by TOM MCLEOD

Hi, my name is Douglas Esagok. I was born and raised in Iñuuvik, but spent a lot of my childhood out in the Delta hunting, fishing, and trapping. Come March 1st, my parents would pull me and my siblings out of school to go to our family cabin to trap muskrats, and other fur bearing animals.

Some of my earliest experiences were when my father Frank Joe Esagok taught me how to snare rabbits. He once allowed me and my older sister Diane to run our own muskrat trapline, and to his surprise, we actually caught a lot of muskrats. Beginners luck—haha!

Nowadays, I continue to hunt and trap to sustain my family, ofset my income, and practice Inuvialuit culture. I also train younger hunters, whether it be family members or not.

But mainly, I hunt and trap to keep my skills sharp. It brings me great joy to see and handle a nice fat moose, caribou, or prepare a beautiful prime fur pelt for an auction or local sale. On top of that, you get the feeling of pride that comes with a successful harvest.

One of my most memorable moments was when I watched in awe of one of my hunting partners, who took over when we harvested a big bull moose together: he basically pushed me

aside and said, “I got it!” So, he went to work gutting and skinning. He’s now a very accomplished harvester himself, whom many members of his own family rely upon for meat, maktak, fish, and so on.

Like many Inuvialuit, we respect the wildlife we harvest and do our best to harvest sustainably and ethically, mainly because we know not only youth are watching, but our Elders are too.

So, as a young hunter, I was guided by my Elders and carry their teachings with me; I apply their knowledge almost daily. I was very lucky to have had the upbringing I had mainly because I lost my father and mentor when I was 12 years old.

My uncles Abel Tingmiak, Ernie Dillon, and Lefngwell Shingatok, took me under their wing and taught me about traveling the land, hunting, trapping, and fishing, mainly because they all knew I was eager to learn from the thousands of questions I’d ask them!

When it comes to hunting for food, youth should be taught which parts are edible on caribou and moose, and how to clean it properly. Just because they may not eat a certain part— for instance, head, hooves, or stomach—there’s always Elders in town that want those parts.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit last March, it scared me to the point where I took my family out to our cabin, so we’d be safe should things ‘hit the fan’ in the NWT. We had to pack up and leave pretty fast, as most people in town were doing the same. Luckily, we had assistance from IRC with funding to help us get out, as it seemed almost impossible, because it is so expensive just to go for a weekend—let alone the possibility of staying out for up to three months, or maybe more.

Te upside to all of this was that I got to take my wife and two daughters out for spring break-up. We harvested muskrats, geese, and ducks while we were out there. Our longest stretch was 42 days without going into town! We saw tens of thousands of geese migrating all spring. We had a good spring, although we did flood out! Tankfully, the water receded after two days so we were okay.

In closing, my advice to the next generation of hunters and harvesters is: always respect the land and the animals, listen to your Elders, take only what you need, never waste, and take all the edible parts of your harvest! Quyanaq!

We respect the wildlife we harvest and do our best to harvest sustainably and ethically, mainly because we know not only youth are watching, but our Elders are too.

My name is Christopher Ruben and I am an Inuvialuk Beneficiary from Paulatuuq, NT. I was born in Cambridge Bay, NU, and moved from there to Paulatuuq in 1972.

Well, I grew up with a very traditional lifestyle with my dad and mom (Edward and Mabel Ruben). Each year—especially when it was the season to harvest, like August—we'd be getting ready to stay at the Hornaday River for about a month or so, fishing and ensuring we have the fish (char) stock for the long, cold winters! Not only that, we would harvest caribou when it was time to do so—especially middle/ late August to September when the tuktu are migrating south! On July 1st, we'd be preparing for the annual Beluga Harvest, traveling a good distance to get the whales; it’s always an exciting time! Goose hunting I'd say for me would be on top of my bucket list each year for sure, and that’s when it warms up in the spring of May.

It’s priceless to be out there with the land and the animals. You feel a big part of it in your body; you feel free, and you’re getting good healing from the land. It's one of a kind. You

have to be out there to feel all the energy, like you’re one with Mother Earth or Nature! I love everything about our animals. Even if it’s just a bird or a flower or a bee—it’s all one! It's amazing...[harvesting] is something I'm very happy to be a part of each year.

If you want to be a harvester or a good hunter, it has to be taught from your parents, or maybe a friend, an uncle, or a brother-in law. You have to be taught especially with the land; you have to know the country that surrounds you in your community! If you have that drive to want to learn, it shouldn't be that hard! You’re never too old to learn!

If you’re going to harvest for food, then yes— every bit counts if it’s for food on your table or even making clothing, sewing, or what have you! Ten yes—use all that you can!

COVID-19 has had an efect on everyone. For example, if you ordered shells for your rifle or shotgun, you’d experience delays in getting your supply from retail stores, and it won't make it on time! It slows the process of harvesting. Te only other option I see is to get it ahead of time.

But, the community hunters are always aware of harvesting times. So, doing your stock before hunting—it prepares you even more.

What I’d have to say about the next generation is: take it slow, ask questions, don’t rush yourself in what you're harvesting for, take everything that can be used, don't waste. Soak in everything that you’re taught from Inuvialuit teachers, community Elders, leaders, your father, uncle, brother, sister, mom, or aunt.

All of this is continuing on our traditional lifestyles, ensuring the next generations have this Harvesting Right—for now and for the future!

Take it slow, ask questions, don’t rush yourself in what you're harvesting for, take everything that can be used, don't waste. Soak in everything that you’re taught.

This thriving Inuvialuit business is ready to warm our hands and our hearts this winter

Fred Carpenter was born in October of 1908 near Tuktuuyaqtuuq and died April 14th, 1984. His mother was an Inuvialuk named Divana and his father was John Carpenter from France. Fred moved down the west coast and settled north of Cape Kellett on Blue Fox Harbour. Then he returned to the mainland, not coming back to Banks Island until 1937. That year he established the settlement of Ikaahuk (Sachs Harbour), named for the ship Mary Sachs of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913.

Fred's status as the leader of Ikaahuk (Sachs Harbour) is legion. He was a good man who took interest in his community and tried to help others. Fred Carpenter teamed up with Fred Wolki's brother, Jim, to begin running trap lines. Together they became known for their superior dog teams, as well as becoming two of the top fur trappers in the Canadian North.1

Animals do play a large role in where I am from. We relied heavily on animals for sustenance and clothing. My family has always hunted various animals. I personally don't have much experience hunting or harvesting, since I grew up in Iñuuvik and everything was provided by my family for my mom and me. However, my mom always prepared traditional food for me; even as an adult she would send me country foods as ofen as she could.

My frst experience was goose hunting on Banks Island; before that I have worked on preparing wild meat for consumption. When I lived in Ikaahuk (Sachs Harbour) for

a year as a teacher, I was able to go ice fshing and geese hunting in the spring. It was an amazing experience and I would love to do it again. I hope in the future I can go on other hunting trips for bigger game.

Working with muskox hides began in July 2019 when we started our business Qiviut Inc. The hides are dried and then the qiviut is combed out, which is then made into qiviut yarn. Working with the hides is a lot of work, but also makes me feel more connected to my culture and home. The process of obtaining the mill began with my brother Bradley "Oukpak" Carpenter who found the mill for sale from Alaska. We discussed partnering up and decided that it would be a great business. He few to Alaska and picked up the equipment but it sat unused for a while until we found a space available. From there we began purchasing

muskox hides from Ikaahuk (Sachs Harbour) and Uluhaktuuq hunters. With the mill equipment, we are now able to create qiviut yarn, Nuna Heat hand warmers, roving, and recently have begun to make knitwear.

When we frst acquired the mill, the machines were so intimidating, but with time and patience we were able to run them with minor issues. When we initially started the business, our goal was to be 100% Inuvialuit-owned and operated, and so far, we have held true to that. It has been an amazing journey and an extremely steep learning curve. Through hard work and perseverance, we have overcome many obstacles along the way. We have seen a steady increase in inquiries from around the world. So many people are intrigued by qiviut and want to learn more. As a result, our sales have begun to refect this.

There are many steps in processing quality yarn. The frst step—and most important one—is patience. I can't stress this enough! The milling process begins with combing muskoxen (singular: umingmak; plural: umingmat) hides which can take up to two days of steady combing. Others may sheer their hides, but we prefer to hand comb ours. Once the fbre is combed, it is thoroughly washed and dried. It then moves to our carding machine, which straightens the fbres into roving (long and narrow bundles of fbre) and helps to remove the guard hair. The carding machine is also where we mix other fbres with Qiviut to create our yarn blends. This can take multiple runs to get it ready for the next machine, which is the pin drafer.

The pin drafer takes the roving and turns it into pencil roving coils, which are ready for spinning. The spinning machine not only spins the coil into single strands, it also combines two or more strands together resulting in a spool of plied yarn. Our mill produces either skeins or cones of yarn. The fnal step (which is optional) is the dyeing process. Dyeing can be quite involved and ofen requires a skilled hand, but the results are always worth the extra efort.

At Qiviut Inc. we produce four types of yarn: 100% Qiviut and three blends called Kunik, Niviuk and Qiviut Fingram Sock. In our Inuvialuktun language kunik means "kiss" and this blend consists of 60% Qiviut, 25% Superwash Merino and 15% Silk. Niviuk is an Inuinnaqtun word which is a term of endearment and this blend consists of 60% Qiviut, 30% Cashmere and 10% Silk. Our Fingram Sock Blend is made up of 40% Qiviut, 35% Superwash Merino, 15% Silk and 10% Nylon. Many of our blends and dye colour names refect our culture, land, and language. We wouldn't have it any other way.

All of our yarn can be used to make our knitwear, which is Qiviut Inc.'s newest venture. We are producing mittens, hats, scarves, neckwarmers, socks and much more. Most of our knitwear is produced in house by our talented team member Robby "Halogak" Inuktalik (pictured on right). Robby came on board nearly a year ago and has become our most valuable asset.

Another product we ofer is Nuna Heat. Nuna Heat is a hand/foot warmer made from 100% Qiviut fbre. In our language Nuna means "Earth" or "Land". The idea came to us as a result of growing up in the North. My grandparents used to collect Qiviut of the land and stuf it inside our mitts and boots to keep us warm. We are basically carrying on a tradition passed on through generations.

There are many steps in processing quality yarn. The first step—and the most important one—is patience.

When Qiviut Inc. was frst incorporated, we were producing yarn as a wholesaler. Fast forward a year, we are now producing beautiful knitwear. We are set up in Nisku, Alberta, where we have a storefront and our mill under one roof. In the months to come, we plan on hosting spinning and knitting classes where our customers can learn all about working with this amazing fbre and tour the mill. It would be nice to see some of our Inuvialuit participating in our classes. Although we are located in the South, there are many Inuvialuit and Inuit benefciaries located in or around the Edmonton area, and, as we grow, we hope to provide training and job opportunities to those who are interested. We have many people in the North who contribute in various ways to the mill; this includes harvesting, hide preparation, and combing. As we grow and learn, we expect more of our process to expand back into the North. We are very proud of how far we have come and excited about what the future has in store for Qiviut Inc.

Our plans for the future are to continue to grow Qiviut Inc. and distribute luxurious yarn and knitwear. We would also like to be able to give back to our communities by donating money that will beneft our people in the North.

Our people have always ensured that animals are harvested ethically. All parts of the animals are used for food, clothing, or crafs. The hunters are given a quota of how many muskoxen can be harvested in the year and this ensures that they are not over hunted and nothing is wasted, our people only hunt what is needed.

Qiviut Inc.'s website is www.qiviutinc.com and we are also on Facebook and Instagram @qiviutinc

The pandemic has caused so much misfortune due to separation and isolation. We have always been a people who stick together and helped one another when times are tough. Designed by 10-year-old Inuvialuk artist Gabriella Haogak-Carpenter, 100% of the profts from sales of our new t-shirt will go to assisting Inuvialuit ‘who reside outside the Inuvialuit Settlement Region (ISR). They come in sizes S (small) all the way to 6XL, and are $30.00 CAD plus shipping and handling. Contact us via Facebook or Instagram Messenger to place an order today.

As we grow and learn, we expect more of our process to expand back into the North.

"

Tis is my ofce," exclaims Frank Dillon, as he looks around the Firth River 'fish hole', while taking a quick lunch break in between catching hundreds of fish with a seine net. He does this every fall as part of a multi-year program set out to monitor Dolly Varden populations in rivers situated in the North Slope mountains. Tis program is one of many where Akłarvik harvesters monitor Dolly Varden through the Akłarvik Hunters and Trappers Committee (AHTC) and in partnership with Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO), the Fisheries Joint Management Committee (FJMC), Parks Canada, Yukon Territorial Parks, and numerous community members.

Frank Dillon at the Firth River.

Photo by Ellen Lea.

Frank Dillon at the Firth River.

Photo by Ellen Lea.

WORDS by ELLEN V. LEA (Fisheries and Oceans Canada), MICHELLE GRUBEN (Akłarvik Hunters & Trappers Committee), COLIN P. GALLAGHER (Fisheries and Oceans Canada), JENNIFER COSTA (Parks Canada)

FEATURING

FRANK DILLON, RICHARD GORDON, ALLEN KOGIAK, PADEN LENNIE, BILLY STORR, AND J.D. STORR

Dolly Varden, known locally as iqaluqpik (Inuvialuktun) and dhik'ii (Gwich'in), belong to a group of fshes called char, which includes Arctic char and lake trout. Although they are diferent species, Dolly Varden were called Arctic char in the past because they appeared similar to one another.

On the North Slope, diferent types of Dolly Varden can be found within a river system. Sea run, or anadromous char, grow to larger sizes (almost 3 feet) and migrate seasonally between the river and ocean. Resident Dolly Varden, typically males that are small in size, spend their lives in the river and sneak spawn with sea run char. Lastly, landlocked char are separate populations of small-sized males and females located above waterfalls.

The general distribution of sea run Dolly Varden in the Arctic extends from west of the Mackenzie Delta into the Yukon North Slope and Alaska. Dolly Varden are important to the Inuvialuit and Gwich'in cultures and diets, especially for the communities of Akłarvik and Ft. McPherson.

that char but, mmm, it's ever good." —Michelle Gruben

"It's been a big food source for many years. It's really big with our family. Every Christmas, when our family comes together, we have what we call a cardboard party. We cut up fsh eggs, frozen char, and stuf like that, and most times you can't get my kids to the table to eat—but if there's char cooked, they'll sit down and eat almost a whole fsh." —J.D. Storr