African Vulture species

Vultures are birds of prey – Kingdom Animata, Phylum Chordata, Class Aves. African vultures are in the family Accipitridae – the same family as eagles, kites, buzzards and hawks. There are eleven vulture species in Africa, four are confined to the continent, the rest also occur, naturally, in Europe and Asia.

Cape vulture – Gyps coprotheres

• Africa. Only found in Southern Africa, and increasingly rare.

• Wingspan 2.25-2.65m, 7-11kg, body 95-115cm.

• Cape vultures live in colonies, on cliffs.

Hooded vulture –Necrosyrtes monachus

• Sub-Saharan Africa

• Wingspan 1.73m, 1.5-1.9kg, body 67cm

• Lives in open grassland, forest edge, the coast and edge of deserts. May be seen around human settlements, where it will eat garbage as well as carrion and its other foods.

Bearded vulture – Gypaetus barbatus

• Sometimes known as the Lammergeier vulture.

• Africa, Asia, Europe.

• Wingspan 2.63cm, 5.2-6.2kg, body 104cm.

• Mostly eats bones.

3 PACE Vultures

Photo © Bettina Boemans

Photo © Chris van Rooyen

Photo © Chris van Rooyen

Ruppell’s vulture – Gyps rueppellii

• Also called the Ruppell’s Griffon vulture.

• Africa. Mostly found in East and West Africa, the Sahel, Europe.

• Wingspan 2.4m, 6.8–9kg, body 101cm.

• Breeds in colonies of 2-2000 birds, on cliffs. Young are cared for by parents until the breeding season after they fledge.

White-headed vulture –Trigonoceps occipitali

• Africa.

• Wingspan 2.3m, 3.3-5.3kg, body 85cm.

• Shy, often first to arrive at a kill but will allow larger species to finish before feeding.

• Nest in trees, often Acacia or Baobab.

• Unlike most species, white-headed vultures feed their young for six months after they have left the nest.

White-backed vulture –Gyps africanus

• Africa, Europe.

• Wingspan 2.18m, 4.2-7.2kg, body 94cm.

• Nests in trees, and roosts in groups.

• The most common and widespread species, but has declined by nearly 90% in just three generations! It is now critically endangered.

4 PACE Vultures

Photo © Elize Labuschagne

Photo © Chris van Rooyen

Photo © Chris van Rooyen

Egyptian vulture – Neophon percnopterus

• Africa, Asia, Europe.

• Wingspan 1.68m, 1.6-2.4kg, body 68cm.

• Will lay two eggs, and line the nest with whatever suitable materials are available –wool, grass, even rags.

• Eats carrion, small vertebrates, eggs.

Lappet-faced vulture –Torgos

tracheliotos

• Africa, Asia.

• Lives throughout sub-Saharan Africa, except the wet equatorial zone. Lives in a wide range of habitats from mountain slopes to desert, woodland and savanna.

• Wingspan 2.8-2.9m, 6-8kg, body 115cm.

• Scavenger, also hunts small vertebrates.

• Nests in tall trees.

Palm-nut vulture –Gypohierax angolensis

• Africa.

• Common throughout west and central Africa, in the west of Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique, and the eastern coast of S. Africa.

• Wingspan 1.5m, 1.2-1.8kg, body 60cm.

• Lives where raffia and oil palms grow. An omnivore, mostly vegetarian, feeding on palm fruits, as well as fish, insects, meat and carrion.

5 PACE Vultures

Photo © Albert Froneman

Photo © Jacques Schelschop

Photo © Chris van Rooyen

Distinguishing male and female vultures

The white-headed vulture is the only vulture species in Africa with males and females that have different colouring. The female has white secondary feathers whereas the male is all dark.

Cinereous vulture –Aegypius monachus

• Also known as Black or Monk vulture.

• Mainly Asia and South Europe, rare in North and West Africa, the Sahel. Those in Africa tend to migrate to Europe in the wet season.

• Wingspan 2.6-2.9m, body 110cm, 6.2-8.5kg. Massive bill up to 9cm long.

• Usually solitary, in remote, mountainous regions, away from people. Nest in trees, often near cliffs, in loose colonies. Young are cared for by parents until the breeding season after they fledge.

Griffon vulture –

Gyps fulvus

• Also called Eurasian Griffon vulture.

• Africa, Europe, Asia.

• Lives across Asia, southern Europe and north Africa, though not in the Sahara desert.

• Wingspan 2.6m, 6.2-8.5kg, body 110cm.

Collective nouns

Can you find a kettle, committee and wake in this book?

A group of vultures at rest is a ‘Committee’.

A group of vultures that are flying is a ‘Kettle’.

A group of vultures feeding is a ‘Wake’.

6 PACE Vultures

Photo © Meydad Goren

Photo © Meydad Goren

7 PACE Vultures

White-backed vulture © Albert Froneman

Vulture wings and flying

African vultures all have long, broad wings, with deeply slotted primary feathers. Their wings are adapted to fly high and far. They soar or glide gracefully on wind currents called thermals – flying techniques that use very little energy, so enable them to be high in the sky for long periods of time.

Vultures are not good flyers, except for soaring. Landing and take-off can be difficult and clumsy.

8 PACE Vultures

Cape vulture fledging © VulPro

Cape vulture © Chris van Rooyen

Size

Vulture wingspans (from the tip of one outstretched wing to tip of the other) can range from 1.4-2.9m. The photo below shows Obert Gayesi Phiri, manager of VulPro’s sanctuary, in front of a life size image of a Cape vulture!

The biggest Wing-span

Lappet-faced vultures have some of the biggest wingspans – up to 2.9m. Cinereous vultures also reach 2.9m and some say that 3.1m has been recorded!

Weight

Cinereous vultures are heavy, they average between 7 and 12kgs, females are heavier than males and weigh up to 14kg.

Height

Cape vultures can be 1.2m tall when standing!

The smallest

Hooded vultures are smaller than most, but the smallest is the Palm-nut vulture, with a wingspan of 150cm, they weigh no more than 1.75kg with a body only 60cm.

The Ruppell’s vulture is the highest flying bird in the world –observed from an aeroplane at 11,278 metres above sea level (32,000 feet). Most creatures would not be able to breath at that altitude!

9 PACE Vultures

Image © VulPro

Senses

Vultures have few or no feathers on their heads and necks. This helps with cleanliness, and to regulate body temperature. By exposing or by protecting the bare skin, they lose or retain heat.

The bald patches are known as the ‘eyes’ or ‘blushing spots’ of a vulture. They are able to help regulate temperature and also used to highlight the mood of the bird. If they turn red, the bird is angry or trying to dominate, if they are blueish, the bird is relaxed.

African vultures don’t have good hearing.

Like most birds they have a poor sense of smell. They are very sensitive to, and respond to small changes in air pressure and movement.

Vultures have fantastic sight, four to eight times better than humans.

10 PACE Vultures

Cape vulture © VulPro

Cape vulture © Penny Fraser

Communication

Vultures do not vocalise a lot. They will hiss and grunt when feeding to warn other birds away from the food they want. Vultures hop, jump and stretch out their wings to intimidate each other when bickering over food.

Vultures don’t have a syrinx (the part of the throat that allows birds to sing) which is why they hiss and grunt instead.

Vultures are not brave. They will quiver with fear when frightened!

Cape vultures © VulPro

11 PACE Vultures

Cape vultures © VulPro

Habitat

African vultures need large open spaces.

They are not found in forests, DRC, Angola (except the smaller Palm-nut vulture) because there is not enough space for them to forage and land amongst dense trees. They soar on wind currents, moving high in the sky and over wide areas, looking for food, or signs of food. It takes a lot of energy for a vulture to ‘take off’ from the ground or from a structure, so they like to perch and nest where they can drop into the air and glide until they catch a thermal which will carry them upwards. They like cliffs, and tall trees.

Different vulture species each have habitats they prefer, for most it is savanna, grassland, open woodland and forest edge.

Cape, Ruppell’s, Egyptian, Griffon and Bearded vultures are mountain species that prefer mountainous areas. Lappetfaced, White-headed, White-backed, Cinereous, Hooded and Palm-nut vultures are tree nesting species that will live in a wide range of habitats from desert to the African tropics.

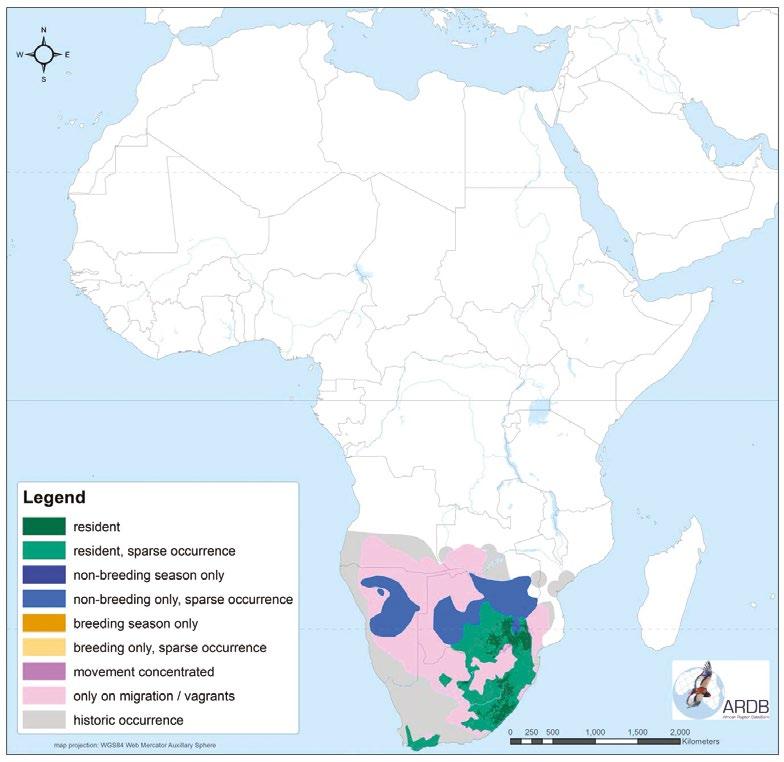

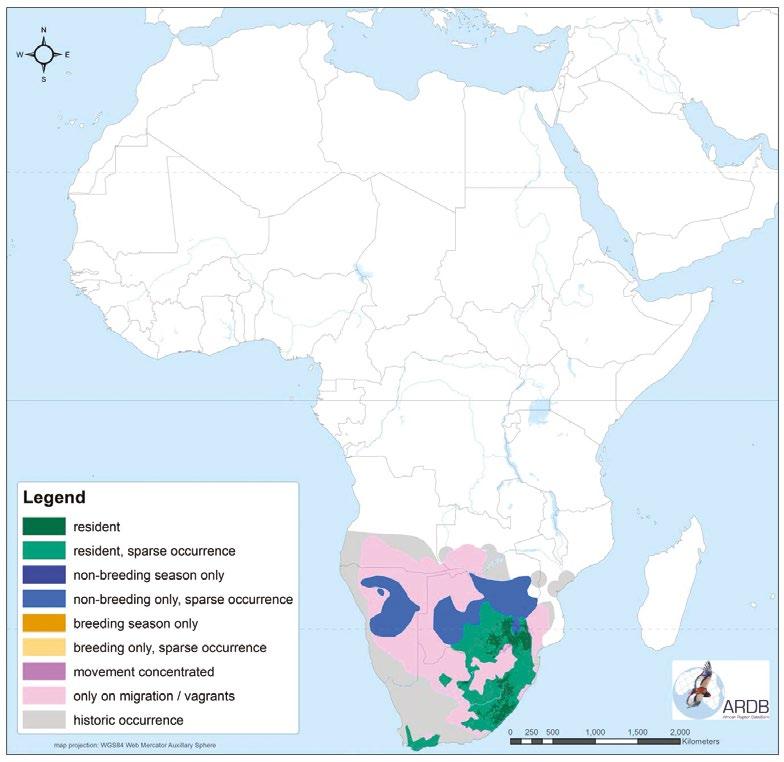

Distribution of species

The distribution or range of a species, is the geographical area over which that species can be found, living wild.

The Palm-nut vulture has a large range including most of the west, central and into eastern parts of Africa, as well as the eastern coast of South Africa. The White-backed, White-headed, Hooded and Lappet-faced vultures have large ranges. The Cape vulture is a southern species, found mainly in South Africa, Botswana and Lesotho (map top below). The Ruppell’s vulture was once Pan-African and common, but its’ numbers have dropped by 97%. The distribution has also reduced (map bottom below).

12 PACE Vultures

Range size

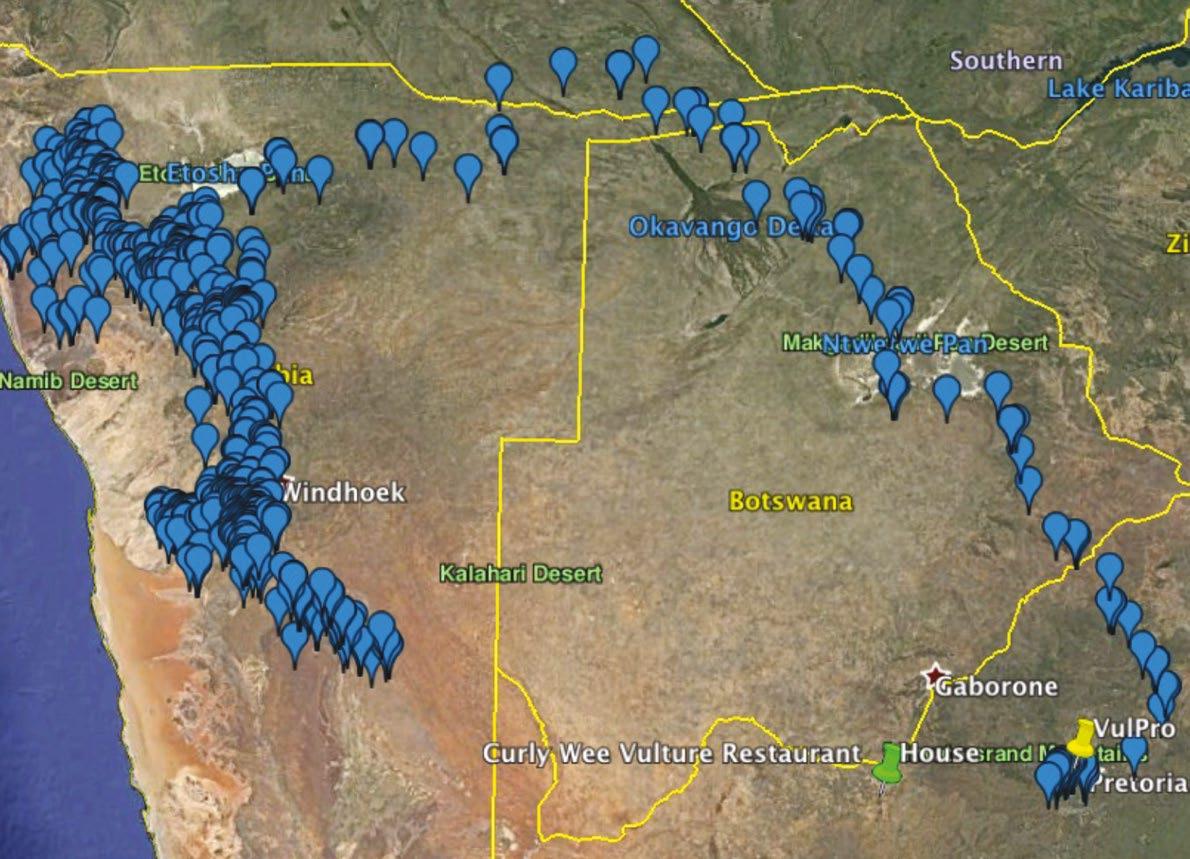

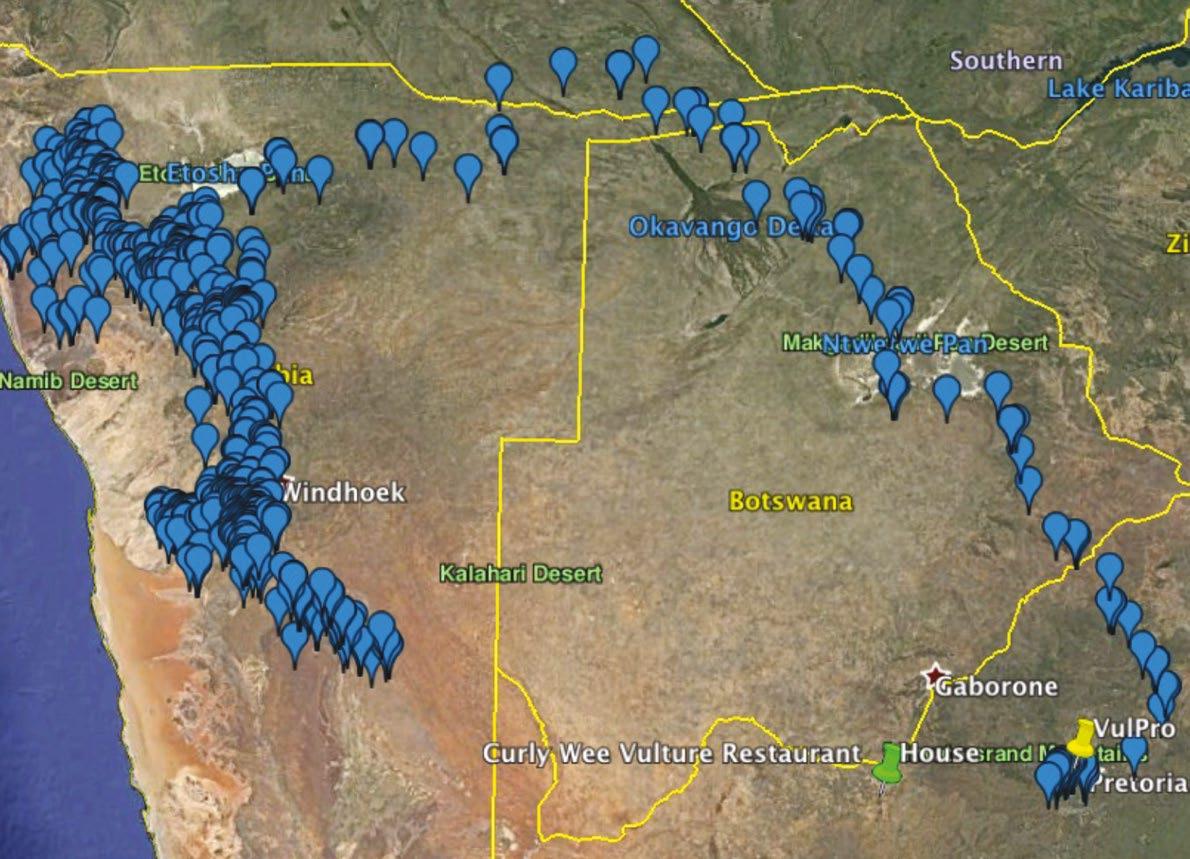

Individual vultures can travel enormous distances.

Vultures are tagged, usually on their leg or wing, so that their location and movements can be monitored.

The blue points on this map mark the movement of an African White-backed vulture that was GPS tracked for seven months in 2015. It travelled north from South Africa across Botswana into Angola. It then flew to the west of Namibia, where it went up and down the country many times.

The journey below was even longer and more convoluted.

National boundaries mean nothing to wildlife!

13 PACE Vultures

The flocks are not family groups, and can include many species.

Vultures form breeding pairs, ‘couples’, that mate for life. Some species prefer to nest away from other pairs, other species breed in colonies of many pairs in the same place.

The breeding season varies depending on species and location.

Vultures make nests. A male and a female will build their nest together, using sticks, often lined with grass and leaves. Different species use slightly different materials – some use thick twigs, some smaller twigs, grass, or leaves.

Family and reproduction

Vultures are quite sociable and often fly, feed and roost in large flocks.

14 PACE Vultures

White-backed vultures © VulPro

Cape vulture © VulPro

Some species of vulture nest on rocky cliffs. Cape and Ruppell’s vultures nest on cliffs in colonies that can be just two pairs or more than 800 pairs.

The white patches on these cliffs in South Africa (photo above) are made by nesting vultures.

Nests may be very close together, often on small ledges.

The colonies, like this one at VulPro (below), are peaceful places, with bickering but no aggression between the birds.

Vultures may use the same nest for many years.

15 PACE Vultures

Cape vultures nesting © VulPro

Cape vulture cliff © VulPro

Cape vultures nesting © VulPro

Some species nest in trees. They usually prefer tall trees, and different species often choose different positions. Hooded vultures nest in forks in the tree, while Whitebacked vultures nest in the canopy. One tree may provide a nesting site for more than one species, each in their favoured locations.

Vultures lay eggs. Most species lay one single egg per year. Female birds will continue laying throughout their adult life.

The parents take turns to sit on the nest incubating their egg. Incubation, depending on species takes 43-56 days. It is quickest for smaller species.

A healthy new egg (right) viewed in front of a light. The red embryo in the centre will grow into the chick.

The nest of Cinereous vultures is huge, 1.5-2m wide and 1-3m deep. They use the same nest year after year, adding to the size each time.

Most vultures lay just one single egg per year.

16 PACE Vultures

White-backed vulture © Albert Froneman

Fertile vulture egg © Kerri Wolter, VulPro

Vulture chick © Amanda Ellis

Vultures eat food for their young, keep it in their crop, low inside their neck. When they have returned to the nest the parent regurgitates the food for its chick, like this one on the right.

Vulture parents protect and nurture their young until they leave the nest. Then young birds look after themselves.

Ruppell’s vultures are a bit different – parents care for young until the next year’s breeding season. White-headed vultures feed their young for six months or so after leaving the nest.

Chicks fledge (leave the nest) at 80-140 days old.

Vultures are some of the most tender, loving and devoted parents you could imagine. They are meticulous in caring for their young. Both parents share the nest building, incubation, feeding and raising of chicks.

Vulture lifespan is up to 35 years in the wild, 50 years in captivity.

17 PACE Vultures

Cape vultures on nest © VulPro

Cape vultures: feeding chick © Bettina Boemans

Food, diet and feeding

Most African vultures are carnivores (carnivores are animals that only eat meat). Vultures are one of the most efficient scavengers on the planet. Scavengers eat carrion – animals that died, or were killed by a predator. Some vultures are omnivores. Omnivores eat food that comes from animals and food from plants. The Palm-nut vulture for example eats meat, fish, scavenges, and eats plant foods like palm nuts. Some species eat garbage and even excrement. Hooded vultures also eat insects and larvae. It is very rare for vultures to attack a healthy living animal, but some have been known to feed on sick or weak animals when carrion is scarce.

Vultures soar high in the sky using their eyes to locate carrion. They also look out for other vultures flying above carrion. In this way they can spot food up to four miles away.

Look at the vultures’ bills in these photographs. They are strong and stiff, adapted to tear food from a carcass. Different species eat different parts – tough skin, soft tissue like intestines, muscle, tendons or bone, some species handle larger, others smaller pieces.

Vultures are opportunistic feeders, which means if they see food they eat. When food is abundant, they feast until full. They can eat up to 20% of their body weight in one meal, but will then sit lethargically digesting, and may not eat again for days.

Vultures are able to eat rotting meat and not get sick because they have strong enzymes and acidity in their stomachs which destroy dangerous bacteria and viruses. This keeps them safe from diseases and means they help in preventing diseases from spreading to humans and other animals. Other scavengers like feral dogs carry diseases and will pass them on to people.

18 PACE Vultures

Griffon vulture © Meydad Govey

Lappett-faced vulture © Katherin Hanzalikova

Hooded vulture © VulPro

Cinereous vulture © Meydad Goven

19 PACE Vultures

White-backed vultures squabbling © Clint Ralph

Lappet-faced vultures squabbling © Clint Ralph

Vulture feet

Unlike eagles, vultures are not able lift and carry away large pieces of food, nor whole animals, unless very small, like lizards. Compare the feet of eagles left and vultures right, in the pictures below.

Eagles have strong legs and feet, and large talons. Vulture feet are smaller, with shorter claws.

Vultures use their feet for stability when they are pulling food from a carcase.

20 PACE Vultures

Fish eagle © VulPro

Martial eagle © VulPro Cape vulture © VulPro

Cape vulture © VulPro

Hygiene

Vultures are very clean animals. They keep themselves clean and they keep the environment clean for us. They bath and preen their feathers after eating. Their bare heads and necks mean that rotten food and bacteria doesn’t stick on their feathers.

Vultures and public health

Vultures are keystone species.

The role of keystone species in food chains and food webs means that if they disappear the whole ecosystem will change. If the number of vultures reduces, then the number of crows, feral dogs, jackals and other vermin which eat carrion and waste will increase. Unlike vultures these animals carry and spread disease.

Vultures can eat dead animals that have foot and mouth disease, rabies or even anthrax and the infection will most likely end in the vulture’s digestive system, they clean up and destroy safely.

Vultures help keep us safe.

Vultures – ‘Basically, they are the cleaning crew’.

21 PACE Vultures

Cape vultures bathing © Bettina Boemans

Cape vultures feeding © VulPro

22 PACE Vultures

Cape vulture fledgling © VulPro

23 PACE Vultures

Cape vulture © VulPro

Dangers faced by Vultures

Natural predators

Eagles, leopards and baboons will pluck vulture chicks from their nest. They will also take birds that fall from a nest or are injured on the ground. Rarely, hyenas and other big carnivores catch adult vultures when they are distracted in a feeding frenzy, or lethargic after gorging on food. Humans are their biggest threat.

Humans and human activities are the biggest threat to vultures.

Vultures don’t see power line cables, so they collide with the wires and suffer injuries, almost always fatal.

Image © VulPro

Image © VulPro

As well as injury from the impact of collisions, vultures, and other birds, can be electrocuted when they fly into electricity cables.

This vulture was electrocuted. Both wings were very badly burned. It did not survive.

Vultures often perch on electricity pylons. Pylons and poles provide a resting place with clear views. But thousands are maimed or killed every year.

This is the foot of a vulture that was electrocuted. The skin and flesh on its feet were burnt off.

Countries across Africa are working hard to improve the supply and availability of electricity. As infrastructure is put in place it must be safe, for people and for wildlife. We must campaign and insist on this. The design on the left is dangerous for vultures. The modified design on the right is safe.

Can you see the difference?

When tags are attached to the cables, vultures see these and avoid the danger.

It is safest when electricity cables are buried underground.

25 PACE Vultures

Electrocuted Cape vulture © VulPro

Image © VulPro

Images © VulPro

Poisoning

Vultures have evolved to resist powerful naturally occurring diseases yet some human created substances are deadly poisons to vultures.

One poisoning event can wipe out an entire colony of vultures.

In one single event in August 2022 one hundred vultures were killed by poison in Kruger National Park, South Africa.

In June 2019, five hundred and thirty vultures were killed by poison in Botswana.

Illegal poachers are responsible for many vulture deaths. Elephant and rhino poachers poison vultures to stop them alerting wildlife guards to their illegal activities. This is called Sentinel killing. If wildlife guards see vultures gathering and circling in the sky, they will investigate. They know that vultures fly like that when they have seen food and it may be that wildlife has been killed by poachers. The vultures act as sentinels or guards.

Some people use vulture body parts for traditional medicine. Thousands of vultures lose their lives for this reason. In Guinea-Bissau West Africa, in one brief period in 2020, two thousand birds were deliberately poisoned using pesticides, just to supply this ‘muthi’ trade. There is no evidence that medicinal or ritual use of vulture body parts has any effect – people wasting money and vultures dead for no reason. Some of West Africa’s best traditional doctors now use plant based alternatives. Better for vultures, better for us.

There is no evidence that medicinal or ritual use of vulture body parts has any effect. Some of West Africa’s best traditional doctors now use plant based alternatives. Better for vultures, better for us.

Some vulture poisoning is not intentional….

Lead ammunition used by hunters can poison vultures. Vultures consume the lead shot when feeding on carcasses left by hunters. Some countries have made lead shot illegal, replacing it with steel, which is not poisonous.

Pest control poisons. Livestock farmers in some countries cause vulture deaths unintentionally. Farmers that leave poisoned bait intended for predators threatening their livestock – feral dogs, jackal, etc – often end up also killing vultures that feed on the baited carcasses.

26 PACE Vultures

Veterinary drugs and the Asian Vulture crisis

In the 1990’s 95% of Indian vultures, millions of birds, died. They were poisoned, unintentionally, by eating the carcasses of cattle that had been treated with a widely used anti-inflammatory drug called Diclofenac.

The drug is safe for cattle, and humans, but it causes vulture’s kidneys to fail. When the vultures died, the number of feral dogs,

crows, rats and other scavengers skyrocketed. The number of rabies cases also sky-rocketed. Vultures contain rabies, other scavengers do not.

Researchers in Ethiopia have seen vulture numbers decrease and feral dogs increase. They fear the same public health outcomes experienced in Asia, including massive increase in rabies cases.

27 PACE Vultures

White-headed vulture © Jamie Soto

What can we do? Respect

Like most wildlife species vultures are suffering from loss of habitat. They have fewer safe places to forage and fewer safe places to breed. If you know where vultures live, keep your distance, respect their space, don’t disturb or threaten them, and encourage others to do the same.

Teach

Share what you’ve learned about vultures with those around you, so that our communities and our next generation become vulture protectors.

Don’t use poisons and pesticide –against any wildlife.

Advocate

As African countries develop, so vultures face more dangers from modern infrastructure like cables, power lines, pylons, buildings, airports and reservoirs. We can all play our part by pushing for any development we are involved in to be wildlife safe. Also, share what you know with teachers, journalists, planners, electricity supply companies, and local authorities, so that vulture friendly decisions are made.

Bust those myths

Vultures can see things that are a long distance away, their eyesight is eight times stronger than us humans. They cannot ‘see’ things that are not there, they cannot help you see events that have not yet happened, nor help improve your sight, insight or judgement. To believe they can is superstition, and not true.

Vulture body parts will help you no more than a wooden replica – save your money, and keep the vultures alive, for everyone’s sake.

Read more on the VulPro web site

www.vulpro.com

If you find an injured vulture, call a conservation agency.

28 PACE Vultures

© Charne Wilhelmi

References

The Vultures of Africa. 1992. P. Mundy, D. Butchart, J. Ledger & S. Piper. Acorn books & Russel Friedman books. South Africa.

Magnificent vultures of Africa. 2020. VulPro & Hans Hoheisen Charitable Trust. PO Box 285, Skeerpoort. 0232. South Africa

Vultures & biodiversity – saving lives! Education booklet, 20 pp. VulPro. www.vulpro.com

VulPro Fun Facts & Games. Education booklet, 16 pp. VulPro. www.vulpro.com

Old world vultures. Sept 2019. vol. 261. VulPro & Thea Felmore Arica’s unsung garbage collection heroes. Africa Geographic Stories & Galleries. https://africageographic. com/stories/vultures

BirdLife International 2022 IUCN Red List for birds. Downloaded from www.birdlife.org on 09/09/2022.

Image credits

Photographs used with permission and are copyright of VulPro. Special thanks to photographers: Meydad Goren; Elize Labuschagne-Hull; Albert Froneman; Chris van Rooyen; Charne Wilhelmi; Jacques Schelschop; Kerri Wolter, Bettina Boemans, Katherin Hanzalikova, Jamie Soto, Clint Ralph and Amanda Ellis.

Distribution maps reprinted with permission. From: Buij, R., Davies, R., Kendall, C., Monadjem, A., with Rahman, L. & Luddington, L. 2019. In Prep. Vulture strongholds and key threats: a mapping exercise to guide vulture conservation in Africa.

For more information on vultures, visit

www.vulpro.com

VulPro’s kids corner vulprokidscorner.wordpress.com

On Facebook www.facebook.com/VulProAfrica

Follow VulPro’s tracked vultures on www.vulpro.com/vulture-tracking

Endangered Wildlife Trust

www.ewt.org.za

29 PACE Vultures

Photo © VulPro

Somebody somewhere has found a solution! The idea behind PACE is to spread simple solutions to environmental problems between communities across Africa. From fuel-saving stoves to rainwater harvesting, solving human – wildlife conflict, compost making to tree farming. PACE shares information about the environment and the very practical ways in which people are addressing common environmental problems. There are ten modules in the PACE pack, this booklet is part of the Living with Wildlife module.

PACE is for students, teachers, community use and general reading

Contact pace@tusk.org www.paceproject.net

VulPro works across South Africa to protect endangered vulture species. VulPro has a rescue and rehabilitation centre to treat injured, grounded, and disabled vultures. Rehabilitated and captive bred vultures are released and monitored. VulPro does research, education, advocacy and outreach. It also runs a ‘vulture restaurant’ that provides regular safe food to wild vultures, and advises others on correct and safe vulture restaurant practice.

Contact www.vulpro.com

Acknowledgements

TUSK thanks DHL, ICAP and the Vodaphone Foundation for their significant and generous support of PACE. Their support has been fundamental to the success of PACE to date.

30 PACE Vultures

Image © VulPro

Image © VulPro