CONNECTING ALUMNI, FRIENDS AND COMMUNITY

JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO

Dr. Timothy F. Murphy Scholar, leader, humanitarian, community connector

CONNECTING ALUMNI, FRIENDS AND COMMUNITY

JACOBS SCHOOL OF MEDICINE AND BIOMEDICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY AT BUFFALO

Dr. Timothy F. Murphy Scholar, leader, humanitarian, community connector

Dear friends,

Research has always been at the heart of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, driving innovation in health care. In this edition of UB Medicine, we proudly highlight our researchers who are deeply committed to addressing health disparities.

Through groundbreaking research and collaborative partnerships, they are forging new connections between our school and the community, driving impactful change.

With a dynamic team of seasoned and emerging leaders, the Jacobs School is poised to redefine health care. Our vision is a future where everyone, regardless of background or location, has access to exceptional care.

I am incredibly proud of our Jacobs School faculty, whose extraordinary achievements have been recognized by esteemed institutions and the highest levels of academia.

Among these outstanding individuals is Timothy F. Murphy, MD, a SUNY Distinguished Professor and key leader in our Jacobs School. As senior associate dean for clinical and translational research and director of UB’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Dr. Murphy has significantly advanced our university’s mission. His visionary leadership has fostered a culture of innovation and collaboration, transforming the institute into a hub for cutting-edge research, attracting top-tier talent, and securing substantial funding. Dr. Murphy’s dedication and achievements have been recognized with the UB President’s Medal, honoring his exceptional scholarly achievement, humanitarian acts, generosity and exemplary leadership.

We are also thrilled to welcome several new chairs and key leaders to our team whose expertise and vision will further strengthen our mission.

While we celebrate these accomplishments, we also pause to honor the legacy of departing colleagues whose dedication has shaped our institution. Their mentorship and expertise will continue to inspire us.

As we look ahead, we remain steadfast in our commitment to fostering an inclusive environment where every perspective is valued. Together, we will advance medical research and education, making health equity a reality for all.

I hope you enjoy this edition of UB Medicine as we celebrate the remarkable work being done at the Jacobs School.

Warmest wishes,

Allison Brashear, MD, MBA Vice President for Health Sciences and Dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

UB Medicine is published by the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB to inform alumni, friends and community about the school’s pivotal role in medical education, research and advanced patient care in Buffalo, Western New York and beyond.

VISIT US: medicine.buffalo.edu/alumni

COVER IMAGE

Timothy F. Murphy, MD, champion for health equity, and 2024 recipient of the University at Buffalo President’s Medal.

Photo: Sandra Kicman

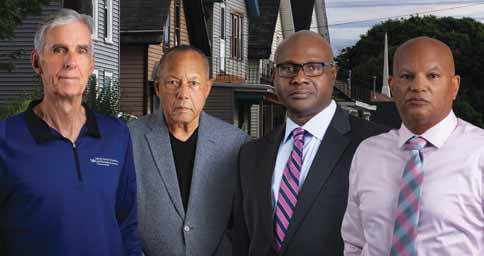

24 BUILDING MOMENTUM

UB, Jacobs School researchers fueling acceleration of community-focused movement addressing health disparities

26 MURPHY RECOGNIZED FOR CAREER ACHIEVEMENTS WITH PRESIDENT’S MEDAL

28 ART OF DIVERSITY

Larger-than-life mural reflects Jacobs School’s commitment to community, inclusivity

30 NIELSEN’S ROLE IN PASSAGE OF AFFORDABLE CARE ACT DOCUMENTED IN OBAMA PRESIDENCY ORAL HISTORY

One of the “extraordinary people” invited to tell the story of the 44th president

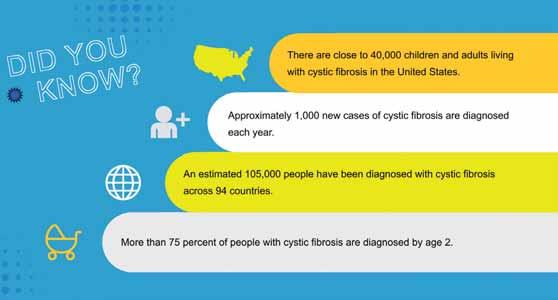

Decades of UB research have dramatic effect on the lives of patients with cystic fibrosis

ALLISON BRASHEAR, MD, MBA

Vice President for Health Sciences and Dean, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

Jeffry Comanici

Assistant Vice President for Principal Gifts, Executive Director of Advancement

Editor Patrick S. Broadwater

Contributing Writers

Dawn Cwierley

Ellen Goldbaum

Dirk Hoffman

Copyeditor Ann Whitcher Gentzke

Photography Sandra Kicman

Meredith Forrest Kulwicki Douglas Levere Nancy Parisi

Art Direction & Design Ellen Stay

Editorial Adviser

John J. Bodkin II, MD ’76

Affiliated Teaching Hospitals Erie County Medical Center

Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center

Veterans Affairs Western New York Healthcare System

Kaleida Health Buffalo General Medical Center Gates Vascular Institute

John R. Oishei Children’s Hospital Millard Fillmore Suburban Hospital

Catholic Health Mercy Hospital of Buffalo Sisters of Charity Hospital

Correspondence, including requests to be added to or removed from the mailing list, should be sent to: Editor, UB Medicine, 955 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14203; or email ubmedicine-news@buffalo.edu

A select collection of images from events happening at the Jacobs School over the past few months.

In recognition of Mental Health Awareness Month, SUNY Chancellor John B. King Jr. visited the Jacobs School on May 15 to join President Satish K. Tripathi, Dean Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, and others for a comprehensive discussion about mental health

All eyes were turned skyward— wearing the proper protective eyewear, of course—on April 8 for the once-in-a-lifetime solar eclipse. Buffalo was one of the locations in the path of totality. Hundreds of spectators gathered on South Campus to view the rare celestial event, which impressed despite cloudy skies. Photo: Douglas Levere.

resources for students. The discussion also addressed research to develop new therapies and outreach services for the community, made possible, in large part, through substantial New York State investment. Photo: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki.

A packed house was on hand in M&T Auditorium in November for a kickoff event celebrating the launch of the Future of Health report, a joint effort from the Jacobs School and the Jacobs Institute. The event featured nearly a dozen guest speakers discussing key takeaways from the groundbreaking report. A reception followed in the Jacobs School atrium. To learn more or get your free copy of the report, scan the QR code.

David A. Milling, MD, speaks as New York State Commissioner of Health James V. McDonald, MD, and Jacobs School Dean and Vice President for Health Sciences Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, look on during a press conference at the Jacobs School last December announcing $4.6 million in state funding to help increase diversity among the physician workforce in New York. Photo: Sandra Kicman.

A delegation from Uzbekistan’s Ministry of Health visited Buffalo in early February, stopping to visit several sites at the University at Buffalo as part of a tour of the U.S. to bolster the Asian country’s public health capabilities. After stops at UB’s Clinical and Translational Science Institute and the School of Public Health and Health Professions, the Uzbeki scientists learned about the Jacobs School’s medical curriculum and toured the Downtown Campus, including stopping at UBRISE2 Surgical Center, where they were photographed with Michael Rauh, MD, assistant professor of orthopaedics. Photo: Sandra Kicman.

The Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences recently added several new associate deans to its leadership team.

• Gustavo A. Arrizabalaga, PhD, joins the Jacobs School as senior associate dean for faculty affairs.

• Jennifer A. Surtees, PhD, professor of biochemistry, has been named associate dean for undergraduate education and STEM outreach.

• Kara M. Kelly, MD ’89, has been tabbed as associate dean for pediatric translational and population health research.

• Robert F. McCormack, MD, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine, has been named associate dean for ambulatory strategy.

Arrizabalaga joins the Jacobs School from the Indiana University School of Medicine (IUSM), where he distinguished himself as a professor in the Departments of Pharmacology and Toxicology, and Microbiology and Immunology.

Arrizabalaga has served as the assistant dean for faculty affairs and professional development, assistant director of the independent investigator incubator and director of faculty mentoring at Indiana University.

research portfolio includes numerous peer-reviewed publications that have significantly advanced our understanding of parasitic diseases.

As senior associate dean for faculty affairs, Arrizabalaga oversees faculty recognition, career development and mentoring. He works closely with the dean and Jacobs School leadership to lead recruitment, appointments, promotions and tenure decisions. His strategic leadership will support faculty success and promote a diverse and inclusive academic environment.

Surtees has been a member of the Jacobs School faculty since 2007. She has served as co-director of the Genome, Environment and Microbiome (GEM) Community of Excellence at UB, which advances understanding of the genome and microbiome, and their interaction with the environment, through research, education, community programs and art.

He earned his PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he conducted pioneering research on the Drosophila protein nanos. He further honed his expertise during his postdoctoral fellowship at Stanford University School of Medicine, focusing on molecular and genetic studies of Toxoplasma gondii. His impressive

In her new role, Surtees provides oversight of and strategic vision for the Jacobs School’s undergraduate educational programs, provides strategic vision for K-12 STEM educational outreach and engagement in the Jacobs School, and initiates STEM-focused community outreach for adults.

An internationally recognized expert on genome stability and genetic diversity, Surtees has focused her research on the general problem of maintaining genome stability, which refers to an organism’s or cell’s ability to accurately transmit genetic material to a new generation.

As co-director of GEM, Surtees spearheaded genome and microbiome literacy programs in the community, particularly the city of Buffalo, through engaging events to promote conversation and hands-on inquiry-based activities, workshops and lessons for K-12 and adult populations.

For her work, she was honored with the Jacobs School’s Community Service Award for Excellence in Promoting Inclusion and Diversity.

In close collaboration with Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center and UB’s research offices, Kelly focuses on overcoming barriers in research processes, fostering innovative research projects and strategically enhancing research expenditures at the Jacobs School. In addition to her vital role in expanding research training programs and developing initiatives to strengthen the clinical-translational workforce within the region, she facilitates faculty research by connecting them with local research cores, such as the UB Biorepository, and enhancing available services.

In her new role, Kelly’s leadership deepens UB’s research relationship with Roswell Park, where she occupies the Waldemar J. Kaminski Endowed Chair of Pediatrics and is a professor of oncology.

Kelly has extensive experience and recognized expertise as professor of pediatrics and chief of the department’s Division of Hematology/Oncology at the Jacobs School. She also serves as program director of pediatric hematology/oncology at Oishei Children’s Hospital.

In his new role, McCormack, a faculty member and leader at the Jacobs School for over 25 years, is spearheading a crucial transformation initiative: shaping the non-surgical ambulatory practice plans of UBMD Physicians’ Group into a cohesive, patient-centric unit designed to thrive in the evolving health care landscape.

This marks a significant step forward in the Jacobs School’s commitment to enhancing health care access and experience for Western New Yorkers. Working closely with UBMD leadership, clinical partners and university stakeholders, McCormack will create a shared vision and actionable strategies for non-surgical ambulatory care.

Beyond his current position as chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine and president of UBMD Emergency Medicine, McCormack boasts extensive clinical expertise in emergency medicine and a strong record of community leadership and partnership, recognized through numerous awards and honors.

McCormack’s research delves into crucial areas of emergency medicine, contributing to improved patient care and understanding of critical conditions.

HWI

Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute (HWI) will join the University at Buffalo, a move designed to strengthen the two organizations’ joint mission to advance medical science research and education in Western New York and beyond.

With HWI joining UB, the long-standing partnership between the two institutions will be strengthened and will further the legacy of Nobel Prize winner Herbert A. Hauptman, who led HWI for decades while serving as a UB faculty member.

When the transaction is finalized, HWI will be known as the University at Buffalo Hauptman-Woodward Institute (UB-HWI).

UB will maintain HWI’s research center—700 Ellicott St., on the Buffalo Niagara Medical Campus—as a hub for medical science research, and will keep UB-HWI as the building’s anchor. The HWI building will be gifted to the university, subject to required approvals, so that the facility will continue to serve as a hub of scientific research and innovation.

The agreement will build upon HWI’s excellence in structural biology research while leveraging UB’s world-class strengths in drug discovery, artificial intelligence, computational chemistry and other fields.

“Honoring the initial philanthropy of Helen Woodward Rivas, continued by the Constantine family, as well as the many incredible scientific achievements of Dr. Herbert Hauptman and the many talented researchers that followed, past and present, is of paramount importance to our board of directors,” said HWI Board Chairman Sam Russo.

“As we explored possibilities with UB, we sensed clear alignment, and a unique opportunity emerged to meaningfully accelerate our collective research efforts by combining forces. With the entire combined UB-HWI team, we are excited by the potential to grow our impact on the Buffalo community and the world,” he added.

UB President Satish K. Tripathi said that “with UB’s and HWI’s shared mission of research, education and community engagement, the university is very excited to welcome the members of the HWI community into the UB community.”

HWI was founded in 1956 as the Medical Foundation of Buffalo by Woodward Rivas and George Koepf, a Buffalo physician who believed basic research was critical to improving human health. It is believed to be the oldest independent nonprofit

medical research institute in the nation that is dedicated to understanding and curing disease.

In 1985, Hauptman and Jerome Karle received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering new methods to visualize pharmaceuticals and proteins, and how they interact. These techniques have been adopted worldwide in the development of pharmaceuticals. In recognition of Hauptman’s achievement and to honor Woodward Rivas, the foundation was renamed the Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute in 1994.

Today, HWI researchers continue to make critical advancements in structural biology, studying, among other things, the structures of the body’s proteins. This enables HWI scientists—many of whom have appointments at UB—to see what proteins look like when functioning properly, and what they look like in cancer, cardiovascular disease and other diseased states. The work has applications in medicine, biotechnology, agriculture and other fields.

“With the entire combined UB-HWI team, we are excited by the potential to grow our impact on the Buffalo community and the world.”

-Sam Russo, HWI Board Chairman

Pairing the two organizations will spur cutting-edge research and innovation, officials say. For example, UB is home to Empire AI, Gov. Kathy Hochul’s $400 million artificial intelligence consortium. UB will partner with colleagues in UBHWI to explore how AI can advance their understanding of diseases and potential treatments.

Additionally, UB envisions the new UB-HWI facility as a hub for community outreach and other programs designed to build interest in science, health and well-being.

Left: Hauptman-Woodward Medical Research Institute will join UB, the two groups announced at a press conference in May 2024 at the Center of Excellence in Bioinformatics and Life Sciences. From left: Christopher Greene, HWI interim CEO; Provost A. Scott Weber; Connie Constantine, emeritus HWI board chair; President Satish K. Tripathi; and Sam Russo, HWI board chair. Photo: Meredith Forrest Kulwicki.

JAMA Paper: Telemedicine Treatment Twice as Successful as Off-Site Referral for Vulnerable Populations

People with opioid use disorder who have hepatitis C virus (HCV) were twice as likely to be successfully treated and cured from HCV if they received facilitated telemedicine treatment at their opioid treatment program (OTP) than if they were referred off-site to another provider, according to findings published by a University at Buffalo team of researchers in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

The study is one of only a few randomized controlled trials that have been conducted to determine the effectiveness of using telemedicine to improve health care access for vulnerable populations.

Led by Andrew H. Talal, MD, MPH, professor of medicine in the Jacobs School, this study explored the effectiveness of integrating telemedicine into OTPs for HCV management, thereby removing the need for off-site referrals.

The study was conducted from 2017 to 2022 at 12 OTPs in New York State that dispense methadone. Researchers enrolled 602 participants with opioid use disorder who had been diagnosed with HCV. Participants received treatment with direct acting antiviral medications for HCV and were followed for two years after being cured to evaluate for reinfection.

The researchers found that 90.3% of those in the telemedicine arm at an OTP were cured of HCV infection compared to 39.4% of participants referred to an off-site specialist. Two-thirds of those in the referral arm never initiated HCV treatment at all.

The researchers also found that being cured of HCV resulted in subsequent health and well-being improvements for participants, including significant reductions in substance use.

“Our study demonstrates how telemedicine successfully integrates medical and behavioral treatment,” Talal said.

The National Cancer Institute has awarded a five-year, $3 million grant to Remi M. Adelaiye-Ogala, PhD, assistant professor of medicine, to continue studying mechanistic determinants of therapeutic resistance in advanced prostate cancers.

Most prostate cancer deaths occur in men with advanced prostate cancer that has become resistant to current treatments, including androgen receptor (AR)-targeted therapies, according to Adelaiye-Ogala.

“The glucocorticoid receptor (GR) has emerged as a focus for developing inhibitors/modulators that block its activity by competitively binding to its hormone-binding site,” she said. “However, GR can also be activated through mechanisms independent of this site.”

Adelaiye-Ogala said her study aims to understand these alternative activation pathways, specifically focusing on how posttranslationalmodifications activate GR as an oncogene in advanced prostate cancer.

“Our research will help create precise and effective treatments for this subpopulation of patients that are safe and improve outcomes for men with high-risk, advanced prostate cancer.”

To address the increasingly urgent needs of the growing population of adults aged 65 years and older, UB is dedicating $4 million to aging-related research.

The investment will leverage the university’s wide-ranging expertise in age-related issues and research throughout its 12 academic units. It will allow UB to expand and enrich educational programming, enhance faculty recruitment, and strengthen multidisciplinary research collaborations with the goal of generating solutions that address the physiological and societal elements of aging.

The new initiative will dedicate resources toward bolstering these efforts, while also supporting the recruitment of new faculty who are focused on novel approaches to aging-related challenges.

“As a city that is home to minority and aging populations growing more rapidly than in other U.S. regions, Buffalo is uniquely positioned to be the place where innovations targeted to these communities should be developed and implemented,” said Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, dean of the Jacobs School and vice president for health sciences. “This new focus will allow UB to more powerfully leverage its scholarship and innovation to address the increasingly complex needs of our region’s aging population.”

New research published in Nature Neuroscience reveals how memory works on a cellular level, findings that are critical to the understanding and treatment of memory disorders, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

The research focuses on engrams, which are neuronal cells in the brain that store memory information. “Engrams are the neurons that are reactivated to support memory recall,” said Dheeraj S. Roy, PhD, one of the paper’s senior authors and an assistant professor in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics. “When engrams are disrupted, you get amnesia.”

In the minutes and hours that immediately follow an experience, he explains, the brain needs to consolidate the engram to store it.

Remi Adelaiye-Ogala was awarded a $3 million grant to study mechanistic determinants of therapeutic resistance in advanced prostate cancers.

The researchers developed a computational model for learning and memory formation that starts with sensory information, which is the stimulus. Once that information gets to the hippocampus, the part of the brain where memories form, different neurons are activated.

When neurons are activated in the hippocampus, not all are going to be firing at once. As memories form, neurons that happen to be activated closely in time become a part of the engram and strengthen their connectivity to support future recall.

“This research tells us that a very likely candidate for why memory dysfunction occurs is that there is something wrong with the early window after memory formation where engrams must be changing,” said Roy.

Physicians have hesitated to prescribe GLP-1RA medications, such as those with brand names of Ozempic and Victoza, to patients with a history of pancreatitis because it was believed that they could increase the risk of acute pancreatitis.

Now, researchers from the Jacobs School report that their research has found that these medications don’t put these patients at increased risk for pancreatitis, and the drugs may actually lower their risk.

The work was presented June 1 at ENDO 2024 in Boston.

“Our clinic often sees patients with a history of pancreatitis who could benefit from GLP-1RA treatments,” said Mahmoud Nassar, MD, PhD, a fellow in the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism in the Department of Medicine at the Jacobs School.

“GLP-1RA drugs work through a mechanism that not only controls diabetes and aids in weight loss but also has antiinflammatory properties, which likely contributed to the reduced risk,” Nassar explained. “Our research offers good news for patients with a history of pancreatitis. They can now use GLP-1RA drugs to effectively manage Type 2 diabetes and obesity without an increased risk of pancreatitis, expanding their treatment options.”

Stem cell therapy to treat diseases such as multiple sclerosis often has disappointing results because the transplanted cells die off before they can take effect. In fact, more than 95% of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) transplanted into individuals with a spinal cord injury die following injection. This is partly because the

process of injecting the cells can damage them.

Two University at Buffalo researchers are working on a possible solution: injecting shear-thinning hydrogels (STH) into the brain, which protect the cells and result in more successful therapy.

Stelios Andreadis, PhD, SUNY Distinguished Professor of chemical and biological engineering, and biomedical engineering, and Fraser J. Sim, PhD, professor of pharmacology and toxicology and director of UB’s Neuroscience Program, were recently awarded a $2.9 million, five-year grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to further investigate this technology.

“STHs have emerged as promising candidates for the injection of Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes, the cells that form the myelin sheath in the brain and spinal cord,” said Andreadis, who also directs UB’s Cell, Gene and Tissue Engineering Center (CGTE), of which Sim is a member.

“The work we plan to undertake has significant implications for regenerative medicine, as it has the potential to develop novel strategies to enhance stem cell delivery for treatment of devastating neurological diseases that remain intractable to current treatments.”

Stem Cell Study Reveals How Infantile Cystinosis Causes Kidney Failure—and How to Potentially Cure It

University at Buffalo research has identified how a misstep in the genesis of a key component of the kidney causes infantile cystinosis, a rare disease that significantly shortens the lifespan of patients.

Published Nov. 30 in the International Journal of Molecular Sciences, the work reveals that the mechanisms that cause the disease could be addressed and potentially cured through the genome-editing technique CRISPR. That could make kidney transplants, the most effective treatment currently available for these patients, unnecessary.

Infantile cystinosis, the most common and most severe type of cystinosis, occurs as the result of an accumulation in the body’s cells of cystine, an amino acid. The buildup damages cells throughout the body, especially the kidneys and the eyes.

Human-induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) are stem cells that can differentiate into many different cell types. They hold tremendous potential for studying genetic diseases; the drawback has been that differentiation into certain cell types has been problematic. Such is the case with many cell types found in the kidney.

But a new protocol developed by this research team was successful.

“When our normal human-induced pluripotent stem cells were subjected to the differentiation protocol we developed, we were able to demonstrate extensive expression of physiologically important markers of the renal proximal tubule, the specific nephron segment that is altered in this disease,” said Mary L. Taub, PhD, senior author on the paper and professor of biochemistry.

The protocol involved extracting stem cells from a healthy individual and an individual with infantile cystinosis. The researchers developed a culture medium to grow stem cells that included a small number of defined components present in blood, including insulin, specific proteins, growth factors and others. That finding means that the CRISPR genome-editing technique could be used to repair the defective genome and potentially cure the disease.

Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, vice president for health sciences at the University at Buffalo and dean of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB, has been appointed to the board of directors of the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC).

One of 19 board members, most of whom are deans of the nation’s leading medical schools, Brashear will serve from November 2024 to November 2025.

The AAMC represents the nation’s medical schools and teaching hospitals and is dedicated to transforming health care through innovative medical education, cutting-edge patient care and groundbreaking medical research.

“UB is proud that Dr. Brashear has been named to the board of directors of the AAMC. This appointment recognizes her national reputation as an academic health leader, as well as her excellence as a medical researcher and educator,” said A. Scott Weber, PhD, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs at UB.

Brashear was elected to the AAMC Council of Deans in 2022 and assumes the role of chair-elect in the fall of 2024. She was an AAMC Council of Deans Fellow for 2014-15.

A powerful advocate for promoting diverse leaders in medicine, Brashear was instrumental in creating one of the first national leadership programs in neurology for women. She is a frequent lecturer on the importance of diversity in medicine, and a lifelong champion of advancing women’s leadership in medicine.

Several Jacobs School faculty members received recognition from national, state and university organizations. Among them:

Liise K. Kayler, MD, clinical professor of surgery, and Michal K. Stachowiak, PhD, professor of pathology and anatomical sciences, were recipients of 2024 SUNY Chancellor’s Awards for Excellence.

The Chancellor’s Award for Excellence in Scholarship and Creative Activities recognizes the work of those who engage actively in scholarly and creative pursuits beyond their teaching responsibilities.

An advocate for diversity, equity and inclusion in health care and combating structural racism, Kayler co-founded and is president of the New York Center for Kidney Transplantation, a statewide collaborative to improve access to kidney transplantation, and serves on the board of directors of the Kidney Foundation of WNY.

Stachowiak is regarded as one of the world’s leading researchers on fibroblast growth factor signaling and, more broadly, as a firmly established leader in the neuroscience community. Stachowiak has made several seminal discoveries and developed innovative concepts to significantly influence our perception of the genome—its function, structure and regulation.

Amit Kandel, MD, MBA, associate professor of neurology, has been honored by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) with its 2024 Clerkship Director Innovation Award.

The award recognizes individuals who have developed unique tools to teach medical students, assess knowledge and benchmark progress.

Kandel, who directed the clerkship in the Department of Neurology from 2019 to 2023, was honored in part for his use of facilities in the school’s Behling Human Simulation Center.

Four Jacobs School faculty

members have been named SUNY Distinguished Professors, the highest faculty rank in the SUNY system.

Appointed to the distinguished professor ranks by the SUNY Board of Trustees at its meeting on April 16 were:

• Ralph H.B. Benedict, PhD, professor of neurology

• Michael E. Duffey, PhD, professor of physiology and biophysics, and medicine

• Jeffrey M. Lackner, PsyD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Behavioral Medicine

• Sanjay Sethi, MD, professor of medicine and chief of the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care and Sleep Medicine

The rank of distinguished professor is an order above full professorship and has three co-equal designations: distinguished professor, distinguished service professor and distinguished teaching professor. Duffey was named a Distinguished Teaching Professor; Benedict, Lackner and Sethi were named Distinguished Professors.

Benedict is a pioneer in the understanding of cognitive disorders, and the treatment of people with multiple sclerosis (MS). He is one of the top investigators worldwide in standardized neuropsychological testing and quantitative brain imaging used in assessing cognitive dysfunction in MS and other neurological diseases.

Duffey has demonstrated excellence in teaching, curricular development, student mentoring and academic scholarship. He co-founded the interdisciplinary graduate program in biomedical sciences, a revolutionary umbrella curriculum that unified six graduate basic science programs and has served as a model for other institutions.

Lackner is an international expert in the field of cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) for the treatment of gastrointestinal and chronic pain disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). His work on nonpharmacological approaches to chronic

pain has dramatically changed clinical practice guidelines in the U.S., Europe and Asia.

Sethi, assistant vice president for health sciences, is an internationally regarded pulmonologist with a primary clinical and research interest in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the third leading cause of death worldwide.

Gabriela K. Popescu, PhD, and Thomas A. Russo, MD, have been elected Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), which is the world’s largest general scientific society and publisher of the journal Science. Popescu is a professor of biochemistry in the Jacobs School. Her research centers around NMDA receptors, which produce electrical currents that are essential for cognition, learning and memory. Her current eight-year research grant from the National Institutes of Health focuses on the excess activation of these receptors, which can cause pathological cellular loss in stroke, brain and spinal cord diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

Russo, SUNY Distinguished Professor in the Department of Medicine and chief of its Division of Infectious Diseases, is an expert in infectious diseases. He conducts research on gram-negative bacterial infections, antibiotic-resistant infections and works on developing targeted vaccines and drugs.

Anne B. Curtis, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor of medicine, is recipient of the 2024 Dr. Carolyn McCue Award for Woman Cardiologist of the Year. Curtis was presented with the award at the Heart Health in Women Symposium on Feb. 3.

A Jacobs School faculty member since 2010, Curtis is both a clinician, caring for patients at UBMD Internal Medicine, and a Jacobs School researcher, specializing in clinical cardiac electrophysiology, the field of cardiology that studies, diagnoses and treats disorders of the electrical activity of the heart. She was the Charles & Mary Bauer Chair of the Department of Medicine in the Jacobs School from 2010 to 2022.

Leslie J. Bisson, MD, the Buffalo Bills medical director and the June A. and Eugene R. Mindell, MD, Professor and Chair of the Department of Orthopaedics at the University at Buffalo, has received the top research award from the NFL Physicians Society (NFLPS).

Bisson was awarded the Arthur C. Rettig Award for Academic Excellence at the NFLPS Scientific Meeting in Indianapolis, where he presented “How to Leverage an Athletic Training Outreach Program to Deliver Hands-Only CPR Training in Underserved Communities.”

Last October, the Mother Cabrini Health Foundation awarded Bisson a $300,000 grant to address barriers to bystander

cardiopulmonary resuscitation/automated external defibrillator (CPR/AED) training in underserved communities in Buffalo. The aim was to train 60 providers as AHAcertified CPR instructors, and to train 8,000 Western New York student-athletes and their families in hands-only CPR/AED use. In the first 12 months of the program, Bisson and his partners have trained more than 12,000 athletes, their families and members of underserved communities.

Margarita L. Dubocovich, PhD, has been honored by the Association for Clinical and Translational Science (ACTS) as the 2024 recipient of its Award for Contributing to the Diversity and Inclusiveness of the Translational Workforce.

Dubocovich, a SUNY Distinguished Professor of pharmacology and toxicology, received the award April 3 at Translational Science 2024, the annual meeting of ACTS, in Las Vegas.

The ACTS Award for Contributing to the Diversity and Inclusiveness of the Translational Workforce recognizes individuals who, through their careers of mentoring, policymaking or team building, have contributed to a more inclusive and diverse workforce.

Because of her tireless focus on and success in increasing diversity and inclusion in STEM, Dubocovich was named the Jacobs School’s inaugural senior associate dean for diversity and inclusion in 2012, becoming the first diversity officer at UB.

Jeffry Comanici has joined the Jacobs School as the new assistant vice president for principal gifts and executive director of advancement.

Comanici brings a wealth of experience and a deep commitment to fostering academic excellence and community engagement to his role at the Jacobs School. He most recently served as the executive director of post-traditional advancement at Syracuse University. In that capacity, he developed and implemented strategies to engage post-traditional alumni, resulting in significant increases in alumni support and engagement.

He is an active Syracuse University alumnus, having graduated from the Martin J. Whitman School of Management

with a Bachelor of Science in marketing and finance. He also holds a Master of Public Administration from the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs. His career at Syracuse University included roles as assistant dean for advancement at the College of Visual and Performing Arts and chief development officer and leadership positions within the School of Information Studies.

Beyond academia, Comanici has made a significant impact in Central New York. He served as president and executive director of the Syracuse Symphony Orchestra and played a pivotal role in designing and managing a comprehensive principal/ planned/major gift program at the Crouse Health Foundation.

On a dramatic day, surrounded by friends and family, 169 Jacobs School medical students found out where they’ll be heading next in their quest to be a doctor. Precisely at noon on March 15—in synch with thousands of their peers across the country— UB students opened their white envelopes to reveal where they will train in residency.

Jelyn Cruz Eustaquio matched with Brown University for a residency in anesthesiology with a first-year internship in Buffalo.

For Jelyn Cruz Eustaquio, Match Day was like a dream.

The Philippines native matched with Brown University for a residency in anesthesiology with a first-year internship in Buffalo.

That was the ideal scenario for Eustaquio, engaged to an endodontist, whose Western New York contract expires next year.

“Next year, we will go to Rhode Island together,” she said. “I matched in the advanced program, so my first year at UB and my last three years will be at Brown.

“It’s like a dream come true to go to an Ivy League school, but it was also a dream come true for me to go to a SUNY school for medical school. This is the best that I could

have hoped for.”

Eustaquio’s unique journey into medicine began well after she moved to the United States as an 18-year-old. After witnessing health scares affecting her mother and sister, she was inspired by the doctors who provided their care to change careers and pursue a degree in medicine.

She eventually ended up at the Jacobs School, where she felt she could receive personalized attention and mentorship. She credits that guidance with helping her land a competitive Tylenol Care Future Scholarship in 2021, one of only 10 health professions students nationwide to win the top $10,000 prize.

“When I interviewed at UB, I was amazed by the building—it was brand new at that time—but it was really the people I met on the interviews that guided me here. I have no regrets. I am so happy I ended up here because it has gotten me where I wanted to be.

“When I moved here, I had no idea I would end up on this journey. I’m going to be the first person in my family to be a doctor, and this is really huge for me. The barriers, the challenges, when I look back, those pushed me to where I am. But I think it’s the people along the way that really got me where I am—being inspired by the people around me and a lot of the exposures that I had.”

Eustaquio, who lived for a time in Connecticut, is excited to head back to New England for her residency at Brown. But she’s also thankful for the opportunity to

spend another year in Buffalo.

“I’m so grateful I’m going to end up working with people I already know at UB for the first year. I think it’s going to be an easier transition into residency, knowing that I’m familiar with the rotation and the people.”

The only hiccup in Eustaquio’s day was a brief moment when she wasn’t able to get her envelope open.

“I couldn’t rip the envelope, and I realized I don’t know how to use a letter opener,” she joked. “At that moment, I just closed my eyes, and I could feel my heart pumping. I was scared, but I couldn’t wait any longer to see where I was going.”

After tearing into the envelope, she got a good look into what was in store for her in the future while taking a moment to consider where she has been.

“Everyone in this room felt the same way—you work so hard for the past four years, this is a testament to all the work we’ve put in. I’m really proud of everyone here. It’s an amazing feeling. I know it will be hard—residency will be hard—but it’s a new chapter, and every story has a positive and a negative. This is a moment of the positive. You have to celebrate it.”

For a full list of matches and photo gallery from the 2024 Match Day event at the Powerhouse in South Buffalo, visit https://bit.ly/3LNRjGc

David A. Milling, executive director of the Office of Medical Education and senior associate dean for medical education, announced each of the students in attendance, then led a 10-second countdown to the moment students could find out their matches.

“Today, dreams are realized, futures are shaped, and the culmination of years of hard work and dedication is celebrated,” said Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, UB’s vice president for health sciences and dean of the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, in her welcome address to the crowd of students, family, faculty and friends.

“Your potential knows no bounds, and we cannot wait to see what the future holds for each of you.”

The Jacobs School continued its strong tradition of retaining graduates to stay in Buffalo for their advanced training

In all, 27 percent of the class—45 students—have chosen to stay at the Jacobs School for their residencies.

“We see this as a testament to their dedication to our community, the City of Good Neighbors, and their dedication to contributing to our robust health care systems,” Brashear said.

“By continuing their training in Western New York, these future physicians directly contribute to improving health care access and addressing gaps in care delivery, especially for underserved communities.”

Among the specialties that have the most matches from the UB class are: internal medicine (seven), psychiatry (five), family medicine (four), internal medicine - prelim (four), pediatrics (four) and med-peds (three).

This year’s class included two MD/PhD, one MD/MBA, one MD/MPH and two MD/ OMFS dual-degree students.

Alyssa Reese matched into a plastic surgery residency at Eastern Virginia Medical Center in Norfolk.

“I’m really excited, I’m really lucky to match into such a competitive specialty,” she said.

Asked about how she feels about heading to Virginia, the Rochester native who also earned her undergrad degree at UB said she’s looking forward to it. She did a rotation in Virginia and is happy to be headed back there.

“It’s been a wild ride, a rollercoaster, a lot of ups, a lot of downs, but it was all worth it in the end,” said Kelsey Gibson, who matched with her first choice, pediatrics at New York Presbyterian Hospital. “I’m here with my family and my best friends, so to come together and to have such an amazing outcome, it was worth the whole journey.”

Shelley Verma matched into a primary care track in medicine at Strong Memorial Hospital at the University of Rochester.

The Syracuse native said she was elated to be moving a bit closer to home. She is also proud to be pursuing primary care.

“I want to develop better skills to prevent disease in my patients,” Verma said.

Jake Zipp, a Williamsville native, attended UB as an undergrad, enrolled in the Jacobs School for medical school, and is one of three generalist scholars who will be doing their residency in family medicine at UB.

“Doing the General Scholars program, I kind of knew I was coming here, so I was not as nervous as everybody else, but still opening the letter is a cool experience,” he said. “I’m really glad to be staying here. I love the city. I don’t see any reason to leave.”

“It’s been a wild ride, a rollercoaster, a lot of ups, a lot of downs, but it was all worth it in the end.”

-Kelsey Gibson, 2024 Jacobs School medical school graduate

John Ciarletta and Kirsten Frauens met during the first year of medical school and planned to marry a week after graduating from UB.

Engaged couple Kirsten Frauens and John Ciarletta each matched at Strong Memorial Hospital at the University of Rochester.

Frauens, a Rochester native, matched in physical medicine, while Ciarletta, originally from Long Island, matched in neurology.

“We’re going together, so I am good with that,” said Ciarletta. “I’m just very grateful for all the people that help you get to this point. It’s definitely a big milestone, and it’s a mix of excitement and fear of the unknown, but at the end of the day you just have to be grateful for how you got here and all the people that helped you.”

The couple met as first-year medical students and have been inseparable ever since. They planned to get married a week after graduating from UB.

“Neither of us thought we were going to end up in Buffalo for med school, but we did,” Frauens said. “We met each other early on and ended up getting engaged, and now we’re getting married. Everything worked out.”

“Coming to UB was the best decision I ever made,” Ciarletta said. “It was lifechanging for the better.”

Medical School Commencement

Friday, April 26, 2024

3 p.m., Center for the Arts

The Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences graduated 169 medical students during its 178th commencement.

Six students earned dual degrees, including two MD/PhD graduates; one MD/MBA graduate; two MD/oral and maxillofacial surgery graduates; and one MD/MPH graduate.

The Class of 2024 entered medical school at the height of the COVID pandemic, which further strengthened the bonds between classmates, said class speaker Susan Maureen Eichhorn.

“Over these last four years, I have seen people go from strangers to peers to family. We not only worked and studied together, but we watched each other grow into the mature, confident people you see in front of you today.

“We have struggled together, we have persevered together, and more importantly, we have achieved together. This is a success that deserves to be magnified.”

Eichhorn then encouraged her classmates to look ahead to the next chapter.

“As you embark on this phase of your journey, I hope you continue to push the boundaries of what is possible and never lose sight of your capacity to change patients’ lives.”

James V. McDonald, MD, New York State commissioner of health, was the keynote speaker, and James S. Marks, MD ’73, PhD, was awarded a SUNY Honorary Doctoral Degree in Science.

McDonald’s diverse career includes serving as an officer in the U.S. Navy, as well as private practice in rural areas where health care shortages existed. Prior to becoming New York State commissioner in 2022, he served at the Rhode Island Department of Health for 10 years.

He told the graduates that the word “resilience” comes to mind when he thinks of them.

“You started medical school during a pandemic, when there was no vaccine and no treatment. It was a time of uncertainty like had never been seen in this country,” McDonald said. “Resilience has been important to me because medicine is a career full of challenges. It was never on

my bingo card for life to be the physician for 20 million people, but taking care of a large group of people is a privilege.”

Marks is the former executive vice president of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) and an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine.

A pioneer in public health and health equity, and a global leader in child and maternal health, health promotion and chronic disease prevention, he has dedicated his career to reducing health disparities and improving access to quality health care.

Before joining the RWJF, Marks held important leadership roles in public health, including serving as assistant surgeon general and director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

In 2018, Marks and his wife, Judi, BA ’69, MEd ’72, created the James and Judith Marks Family Scholarship Fund, which provides financial support to students in the Jacobs School.

Marks said receiving the honorary degree is special because UB is where he earned his medical degree more than 50 years ago. He said his father and grandfather also earned their degrees at UB and his wife earned her Bachelor of Arts and master’s in education in school counseling degrees from UB.

Marks asked rhetorically what does one hope to gain from a college?

“A sense of connectedness and community with students and faculty,” he answered. “My wife and I got that here, and that is why this recognition is all the more meaningful.”

Biomedical Sciences Commencement

Sunday, May 19, 2024

9 a.m., Center for the Arts

Thirty-five doctoral, 76 master’s and 209 baccalaureate candidates received degrees in biomedical science fields during the May commencement ceremony. Fifteen of the doctoral degrees and eight of the master’s degrees were awarded to students in the Roswell Park Graduate Division.

Four Jacobs School graduates received a Chancellor’s Award, the highest State University of New York undergraduate honor:

• Sarah Bukhari, a biochemistry major, who was an undergraduate researcher in the lab of Jennifer A. Surtees, PhD, professor of biochemistry. Bukhari secured funding from the Experiential Learning Network and was deeply involved in community engagement, serving as both the volunteer coordinator and vice president of the largest student-run prehealth organization, the Association of Pre-Medical Students.

where she earned the 2023 Inspire Spotlight Award.

Among the outstanding graduate students recognized, doctoral graduate Haley Victoria Hobble was honored with the Biochemistry Graduate Student Research Achievement Award and the Dean’s Award for Outstanding Dissertation Research.

Commencement speaker Styliani-Anna “Stella” E. Tsirka, PhD, the Miriam and David Donoho Distinguished Professor of pharmacological sciences and vice dean for faculty affairs at the Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University, spoke about empathy and persistence.

“Beyond the technical skills and academic achievements that you have earned and will continue to earn, what will set you apart is your capacity for empathy, for compassion, your ethical responsibility,” she said. “In the pursuit of scientific advancement, try not to lose sight of the human element and the living organisms whose lives may be impacted by our work.”

• Lea Kyle, a biochemistry major with minors in physics and public health, was a University Honors College Scholar. She was the president of UB Rotaract, a volunteering club on campus, and was also a student researcher in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology, focusing on the effects of chronic inflammation on muscle function due to chronic infection.

• Bryan Renzoni was a biochemistry major, a University Honors College Presidential Scholar and Honors College Ambassador. As a BioXFEL Scholar, he has received multiple research internship positions and worked in two different laboratories, contributing to work on the development of novel organic and organometallic compounds with applications as cancer therapies.

• Rachel Esther Sanyu, an international student from Uganda, majored in pharmacology and toxicology. She was an Honors College Scholar who conducted oncology research within the lab of Wendy Huss, PhD, at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center and at Johnson & Johnson,

Above: Styliani-Anna”Stella” Tsirka, of Stony Brook University, gave the keynote address at the Biomedical Sciences commencement.

Associate professor of sociology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Deadric T. Williams, PhD, was the keynote speaker for the fourth edition of the University at Buffalo’s “Beyond the Knife” endowed lecture series established by the Department of Surgery in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

The title of Williams’ talk was “Structural Anti-Blackness and the Persistent Racial Inequality.”

Williams noted there is a tendency for people to think that racism is an individual-level attribute whereby you have to be intentional to be racist. But intentionality is not a necessary condition for the maintenance of white supremacy and anti-Black racism, he said.

“It is sufficient, but not necessary, especially when we think about this thing called racial disparities in health,”

Last September, approximately 300 community members along with UB students, faculty and staff gathered for the sixth annual “Igniting Hope” conference. The gathering has matured into what organizers describe as a movement aimed at bringing lasting change to the region by ending race-based disparities and their devastating impacts on the health of Black people, Hispanic people and other underrepresented groups.

Williams said. African Americans are more likely to die at earlier ages, he said, noting that maternal mortality and infant mortality rates, in particular, vary across racial lines.

“The debate often emerges when we start talking about why they exist and why they persist,” Williams said.

Deadric Williams, associate professor of sociology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, delivered the Beyond the Knife lecture in M&T Auditorium on Feb. 22.

“Racism is an ongoing feature in the U.S. It is not episodic. Policies and laws are responsible for racial inequality.

“Instead of asking for what accounts for racial disparities in health, I argue we should be asking what are the mechanisms that maintain racial disparities in health,” he said. “When we answer that question we can understand its genesis, how it ends, and becomes recreated and then we can start highlighting the mechanisms, not to account for the gap in health, but what maintains it. And if we can answer the question of what maintains it, then we can find ways to end it.”

“The system was created before any of us were ever born,” he said. “Remember, racial inequality is America’s equilibrium. So anytime there is a social movement (Civil Rights Movement, Black Lives Matter) fighting against the system, it corrects itself because it does not know how to do anything else.”

Williams also talked about how stress gets under the skin to affect health disparities—noting how our brains interpret stressors in a particular way, based on past experiences.

“Our bodies are equipped to deal with acute stress, but are not equipped to deal with chronic stress,” he said.

Williams said the country’s racial disparities are so prevalent and so normative, that it has created a political and racial divide.

“As we move forward, we need to think about racial inequalities as a failure of human rights, period,” he said. “It is not just differences in some outcomes. It is a violation of human rights.”

A central part of the discussion at the conference delved into issues at the core of medical research, such as informed consent and medical mistrust. Moderated by Jamal B. Williams, PhD, assistant professor of psychiatry in the Jacobs School, the session featured David Lacks and Veronica Robinson, the grandson and great-granddaughter, respectively, of Henrietta Lacks.

Lacks was the young, African American mother whose cancerous cell tissue has become, since her untimely death in 1951, one of the most important medical research tools ever discovered. Without her knowledge or consent, tissue was removed during a biopsy she underwent at Johns Hopkins Medicine and shared with the hospital’s tissue lab.

Unlike all other cells, hers (now named HeLa cells after her) didn’t die in the lab. Instead, they rapidly divided over and over, a phenomenon that to this day remains a unique medical mystery. HeLa cells have played a key role in the development of major medical advances, from new cancer treatments to the invention of vaccines that protect against polio and COVID-19 to in vitro fertilization.

Today, Lacks family members are active in the National Institutes of Health’s HeLa Genome Committee, but for decades they had no idea of the extraordinary role Henrietta played in modern medicine. Neither she nor her family was ever given the opportunity to provide informed consent. Only after a tenacious science writer named Rebecca Skloot started researching the story, which eventually became “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks,”

did the family learn about their ancestor’s incredible legacy.

“The Henrietta Lacks story is a story of science at its best and at its worst,” said Williams.

The Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences welcomed the 2024 Can-Am Clinical Anesthesia Conference to Buffalo in May, marking the first time the international event was held on the American side of the border.

Founded by McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, in 1983, the conference brings together leaders in anesthesia from Canada and the United States to share cutting-edge advancements, foster collaboration and inspire transformative change.

The University at Buffalo traditionally participated in the event

Stacey A. Watt led a move to bring the international Can-Am Clinical Anesthesia Conference to Buffalo, marking the first time the event had been held on American soil.

Gender equity, belonging and retention took center stage at the UB DoctHERS Annual Symposium, celebrating women in medicine while tackling persistent challenges.

DoctHERS is a leadership network of female physicians, scientists, faculty, health care professionals, residents and students whose goal is to address current issues in the medical and scientific fields to enhance advancement, mentorship and equal opportunities for future generations of women in medicine and science.

This year’s event, held Feb. 13 in the M&T Auditorium, featured Julie K. Silver, MD, a leading expert on gender equity, as the keynote speaker. Silver was an associate professor and associate chair in the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at Harvard Medical School. She has published groundbreaking research on workforce diversity and inclusion topics.

Silver said accelerating gender equity is really about disparities.

“We have made a lot of progress, but this was probably the most discouraging study for women in medicine when it came out in 2020,” she said, noting a NEJM study titled “Women Physicians and Promotion in Academic Medicine” that included a sample of 559,098 graduates from 134 U.S. medical schools.

“It found that over a 35-year period, women physicians in academic medicine centers were less likely than men to be promoted to the rank of associate or full professor or to be appointed to department chairs, and there was no apparent narrowing in the gap over time,” Silver noted. “We know that critical mass theory does not work in gender equity.”

She said she decided to use her strategic experience to look for tipping points in the process to assist women in medicine in advancing in their careers.

that was hosted in Niagara Falls, Canada, but the last in-person CanAm conference was in 2019.

Stacey A. Watt, MD, MBA, clinical professor of anesthesiology at the Jacobs School, said after the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted inperson gatherings, the conference did not seem to be coming back.

She made a bold decision to act to resuscitate the conference and contacted McMaster University officials.

“I felt it was the perfect opportunity to showcase UB and allow for the American side of the Can-Am conference to have its turn,” she said.

“It has been and will always be a collaborative event, bringing the best of both sides of the border together to discuss differences, similarities and share opportunities,” Watt added. “Our plan is to continue the Can-Am conference here at UB for at least the next five years, if not longer.”

The 2024 conference featured moderators and panelists from partner institutions McMaster University, Albany Medical College, the University of Rochester Medical Center and Western University in Canada.

The keynote address, titled “Addiction in Medicine,” was given by Joshua J. Lynch, DO, clinical associate professor of emergency medicine at the Jacobs School, and the founder of MATTERS, an innovative opioid treatment program.

At this year’s DoctHERS event, Jacobs School Dean Allison Brashear welcomed Julie K. Silver as the keynote speaker. Silver is a leading expert on gender equality and has published groundbreaking research on workforce diversity and inclusion.

“The hardest thing to do is find the tipping points, but when you do, that’s gold because you can drive change really fast,” Silver said. “I decided I was going to start with medical societies and recognition awards.”

Another tipping point Silver said was a Lancet study that showed women in medicine were underrepresented in clinical practice guidelines.

That led her to author a paper in the journal Cell that presented a novel concept Silver called “interorganizational structural discrimination.”

“The idea behind it is if an organization that has known problems with structural sexism or racism or whatever, that if you work with those organizations and they have fixable problems, then you are complicit,” she said.

In response to the growing demand for genetic counseling services nationally and regionally, the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo has hired a program director to launch a master’s degree program in genetic counseling.

Lindsey M. Alico, a Western New York native who was co-director of the genetic counseling program at Sarah Lawrence College, has been hired to implement and direct the genetic counseling program at UB.

Alico, a clinical assistant professor, is a board-certified genetic counselor who earned her master’s degree in human genetics from Sarah Lawrence in 2011. She will guide the UB program through accreditation.

Approved by the New York State Education Department and SUNY, UB’s program is pursuing accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Genetic Counseling, which will allow graduates to sit for the American Board of Genetic Counseling certification exam. Genetic counselors who pass the exam are granted the Certified Genetic Counselor credential, which is required to practice in most areas.

Genetic counselors are experts in genetics and genomics; they provide

Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences medical students working with community anti-violence groups in Buffalo have developed an elective course on “trauma surgery and trauma-informed care.”

The purpose is to train medical students, particularly those interested in surgery, in trauma-informed care in Buffalo’s Level 1 Adult Trauma Center at the Erie County Medical Center (ECMC).

Critical partners are Buffalo’s two antiviolence organizations—Buffalo SNUG (Should Never Use Guns) and Buffalo Rising Against Violence (BRAVE) Trauma Recovery Center—housed within ECMC. BRAVE is Western New York’s only Trauma Recovery Center, having attained that distinction from the National Alliance of Trauma Recovery Centers late last year.

“Students spend half their time working on the trauma service at ECMC alongside attendings and residents, and the other half with BRAVE and SNUG,” said Michael Lamb, PhD, director of surgical education in the Jacobs School and instructor for the elective. “The students serve as navigators for trauma patients and their families, offering support and advocacy during their hospital stay, clinical follow-ups and home visits.”

“The whole goal is to bridge two worlds

patients with information and guidance about inherited diseases and conditions that may affect them and their families. Patients who have received a disease diagnosis may be referred to a genetic counselor to determine if there may be a genetic component to it; couples who are expecting a child or are trying to conceive may also see genetic counselors.

Unlike other members of the health care team, genetic counselors don’t directly diagnose or prescribe. Instead, they help interpret complex genetic and genomic information for patients and empower them to make decisions about their health that are best for them.

“We are trained to facilitate decisionmaking,” said Alico. “We aren’t going to say ‘you need this genetic test.’ Our job is to evaluate and communicate genetic risk information so you can decide if you want the test or not.”

that usually don’t collide,” said Gaby Cordero, MD, a recent Jacobs School graduate who was the first person to take the elective.

The idea to create a trauma-informed curriculum developed from conversations between Jacobs School students Pia Corujo Avila, Katherine Foote and Sydney Johnson, all of whom had been awarded the Department of Surgery’s summer diversity research fellowship for underrepresented students in 2022.

WATCH: Scan the QR code to learn more about the Jacobs School’s innovative approach.

“As the surgeon, the only time you may see the patient is in the OR,” Johnson said. “You need a bit more humanity. When you understand the world the patient comes from, the injury that brought them to the hospital, and what they are going home to, you can be more proactive in their care. When you, the provider, are able to take all of this into consideration, the patient will have better outcomes.”

After years of research and planning, the Jacobs School has launched its brand-new medical school curriculum. Class of 2028 students arrived on campus in July 2024 and were the first to participate in the Well Beyond Curriculum, a cuttingedge approach that will redefine medical education in Buffalo for years to come. Learn more at medicine. buffalo.edu/well-beyond

This spring, 100 farmers and villagers throughout Belize underwent training in lifesaving “Stop the Bleed” techniques provided by a team led by Jacobs School medical students.

Members of the Global Surgery Student Alliance at the University at Buffalo made the trip during their spring break to provide “Stop the Bleed” training, a program of the American College of Surgeons, which has been shared with more than 4 million people worldwide. As a result, many more Belizeans now know how to quickly control bleeding, a critical skill for residents who often live far from health care facilities.

In just a week, the team of Buffalo and Rochester-based students, nurses and physicians traveled to five different locations in rural Belize to do the training.

The idea for the Belize trip started with Rachel Yerden, a second-year student in the Jacobs School who had been working with InterVol, an organization that also repurposes unused extra medical supplies and sends to global areas of need.

Wanting to provide more hands-on assistance to those in need, Yerden began discussing with her peers ways to leave a lasting impact.

“We wondered, what’s the most sustainable way for us to be involved?”

Yerden said. “We knew teaching was highly sought after in these communities, but we didn’t know what we could teach because we are just students.”

But once they discussed the medical disparities experienced by people in rural Belize with Belizean health care workers, it became clear that one of the biggest causes of morbidity and mortality was the inability to get severely injured people treated because of their remote locations. It quickly became apparent that “Stop the Bleed” training would go a long way toward saving lives.

InterVol was on board with the idea and helped connect Yerden with emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in Belize. Yerden organized and led the trip with Seth Baker, another second-year student in the Jacobs School. Buffalo and Rochesterbased health professionals, including those from InterVol, went on the trip as well.

Upon arrival in Belize City, Yerden, who is fluent in Spanish, taught the first class for the volunteers on the trip, as well as

some local EMTs. That training certified 10 physicians and EMTs who traveled with the group throughout the week. These Belizeans are now certified as instructors

Second-year medical student Rachel Yerden said one thing she was most proud of was the eclectic group of people they offered “Stop the Bleed” training to on the trip to Belize. “I taught classes to cacao farmers, banana farmers, families, elementary school teachers, children and health care workers,” she said.

for “Stop the Bleed,” who will, in turn, train more people in their respective communities.

Gender-affirming health care is a bit easier to access in Western New York, thanks to a new webpage developed by Jacobs School medical students working with local clinicians.

The webpage, LGBTQIA2S+ Healthcare Resources in Erie County, went live this past summer and is hosted by the Erie County Department of Health. It provides information about local health care resources specifically for patients who identify as LGBTQIA2S+. (The acronym stands for lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, queer or questioning, intersex, asexual and 2-spirit.)

“People who are seeking genderaffirming health care should know that our region has a solid foundation of clinical and medical resources,”said Gale R. Burstein, MD, Erie County commissioner of health and clinical professor of pediatrics in the Jacobs School. “LGTBQIA2S+ patients are more likely to be disproportionately affected by health disparities. This comprehensive list will save patients time as they research medical care options.”

The need for such a resource became obvious when a new faculty member at the Jacobs School who provides genderaffirming care had difficulty finding other local clinicians who do the same. Genderaffirming health care providers often refer

patients to each other so it’s important for them to be familiar with each other and the scope of their colleagues’ practices.

A quick search turned up only one name: Elana Tal, MD, clinical assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology in the Jacobs School. She knew there were plenty of other clinicians in Buffalo and Erie County providing gender-affirming care, but the fact that they were hard to find was a concern.

Tal organized several students who she knew were interested in improving gender-affirming care in Western New York and gender-affirming education in the Jacobs School. The group included Virginia Alexandria Headd, MD, a 2024 graduate of the Jacobs School; Madison Clague of the Class of 2026; and Zoe Arditi and Berkley Sawester of the Class of 2027.

“We were dismayed at how hard it was to find providers, but also pleasantly surprised by the depth and breadth of services being provided by physicians once we identified them,” said Tal.

Gender-affirming care encompasses a range far broader than people may assume. It can range from medical and psychiatric treatments to many different types of plastic surgery, including oral and maxillofacial surgery and otolaryngology, to speech and language coaching, all of which are available in Erie County.

The Oct. 7 attack on Israel dramatically changed everything in that country. For the Haroush family, living in central Israel, life had begun to change prior to that date, but for very different reasons.

For months, Noa Haroush, 18, had been complaining of weakness on her left side. At first it didn’t seem severe, but as time went on it got worse. By late summer, Noa was experiencing shakiness in her hand and arm, her mother Sharon said.

“It was scary,” Noa recalled. “I didn’t know what it was. I thought maybe it could be from stress from school or maybe a medication.”

Clearly, something was very wrong and the family took her to the hospital. After more than a week of tests and imaging, they received a diagnosis: Noa had Moyamoya disease, a rare condition in which the arteries that go to the brain become blocked, putting the patient at high risk for stroke and bleeding in the brain.

Endowed Chair of Neurosurgery at UB, co-director of the Gates Stroke Center and Cerebrovascular Surgery at Kaleida Health, and president of UB Neurosurgery. “It was on both sides of her brain. She was already having symptoms throughout her whole left side.”

Noa needed surgery immediately. Levy teamed up with his longtime surgery partner, Adnan Siddiqui, MD, PhD, CEO and CMO of the Jacobs Institute, and vice chair and professor in the Department of Neurosurgery at the Jacobs School.

The surgery felt endless, Sharon recalled. It lasted eight long hours. “It was very hard to just be in the waiting room.”

The surgery was completely successful, but Levy told the family it had been one of the most complicated surgeries his team had ever done. The family’s relief was hard to put into words, especially after they learned that Noa’s condition was so severe she could have been very close to having a stroke.

“I really want to thank Dr. Levy, Dr. Siddiqui and their team and all the nurses,” Sharon said. “Everyone took such good care of us. They did such a wonderful job.”

The condition can be cured if brain surgery is done in time. Israel has sophisticated medical facilities. But surgery for such a complex, rare condition is best done at a high-volume facility where surgeons have experience operating on such patients—such as Gates Vascular Institute, where UB neurosurgeons have done this operation numerous times.

The family already had a connection with Buffalo. Elad I. Levy, MD, who chairs the Department of Neurosurgery in the Jacobs School, was born in Israel. His father and Noa’s grandfather have been best friends for decades.

The family made a quick decision to come to Buffalo once they learned of the Hamas attack. Noa arrived in Buffalo with her parents and three siblings on Oct. 8.

While imaging of her brain had been done in Israel, Levy decided to do another cerebral angiography. The procedure involves using a catheter to inject contrast dye into the bloodstream. X-ray imaging then reveals how blocked the arteries have become.

The new images told a terrifying story that hadn’t been evident in the original images, providing a much better roadmap for the surgery.

“She had one of the worst cases of Moyamoya we’ve ever seen,” said Levy, SUNY Distinguished Professor, L. Nelson Hopkins

In addition to state-of-the-art stroke care, complex neurosurgeries for rare conditions are increasingly being done at Gates Vascular Institute, a Kaleida Health facility, by Jacobs School neurosurgeons, making it a top site for complex neurosurgeries.

“We’re an international destination for neurovascular surgery,” said Levy. “When people need this kind of care, and they start to research who can deliver it, we are at the top of the list.”

“We’re an international destination for neurovascular surgery. When people need this kind of care, and they start to research who can deliver it, we are at the top of the list.”

Elad I. Levy, MD, SUNY Distinguished Professor and L. Nelson Hopkins Endowed Chair of Neurosurgery

NYS funding helps grow geographic footprint, introduces ‘no stigma’ vending machines

MATTERS, an innovative opioid treatment program that grew out of a University at Buffalo physician’s frustration with the limitations of care for patients who had overdosed, is expanding its services throughout New York State, thanks to funding from the state’s Department of Health.

end bias and discrimination surrounding opioid use disorder,” said James V. McDonald, MD, commissioner of the New York State Department of Health. “The department welcomes the collaboration with the University at Buffalo’s opioidtreatment program and the deployment of vending machines as an innovative tool to supplement existing harmreduction programs throughout the state.”

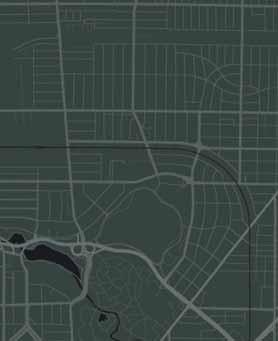

Starting last fall, MATTERS has installed 12 “no stigma” vending machines throughout New York State (see map below), including here in Western New York. They provide free naloxone, the overdose antidote, and free test strips for fentanyl and xylazine.

The first one in Erie County is located outside the Kenmore Volunteer Fire Department, which hosts the machine; it is owned and serviced by Save the Michaels of the World, which raises awareness about drug addiction and its risks. Additional machines in Western New York are on Virginia Street in Buffalo and Main Street in Lockport.

One of the 12 “no stigma” vending machines installed throughout New York State by MATTERS. They provide free naloxone, the overdose antidote, and free test strips for fentanyl and xylazine.

stigma, increase awareness and build a future free from addiction’s grip,” said Allison Brashear, MD, MBA, vice president for health sciences at UB, dean of the Jacobs School and president of UBMD Physicians’ Group.

Chinazo Cunningham, commissioner of the New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports, said: “OASAS is proud to partner with MATTERS in our work dedicated to serving people with substance use disorders. The new MATTERS harm-reduction vending machine builds on OASAS efforts to expand the availability of such lifesaving materials. This is important work, and we look forward to working with MATTERS on future projects.”