MAPPING THE FUTURE

U of I drone lab spearheads aerial monitoring for rangeland management

CONTENTS

HWHI S 25

Photo by Garrett Britton

8

IDAHO’S RESEARCH POWERHOUSE

R1 designation positions U of I within the top tier of research universities.

U of I’s

6

FOCUSED ON MOVEMENT

Researchers aim to reduce injury risk in ROTC cadets through improved movement training.

10

MAPPING THE FUTURE

U of I’s drone lab equips students with advanced skills.

14

GOLDEN MILESTONE FOR A VANDAL LANDMARK

Fifty years after opening, the P1FCU Kibbie Dome remains an iconic athletics complex.

16

WORKING TOGETHER

By blending Indigenous knowledge with STEM education, U of I tackles natural resource challenges and inspires future leaders.

20

ANGLER TURNED SCIENTIST

An INBRE scholar investigates the links between insects and healthy waterways.

22

FROM HAVOC TO HARVEST

U of I students develop a weed-killing robot that could boost reforestation efforts.

24

TEACHING AI TO TRANSLATE

An interdisciplinary team translates a century-old German educational book using generative AI.

28 BRAVE. BOLD. UNSTOPPABLE.

U of I seeks Vandal Family support to accelerate groundbreaking achievements.

32

REVOLUTIONIZING RANGELAND

Students develop virtual fence technology to improve cattle management and wildlife conservation.

34

GIRLS WHO INVEST

A business major leverages U of I’s investment programs to become its representative for an international corporate finance program for young women.

35

KEYS TO LEARNING

A CLASS senior discovers his future while studying music from his past.

37 THE TIME IS NOW

A U of I researcher finds that treating certain health conditions can reduce the number of dementia diagnoses.

Photos by Garrett Britton

Online subscriptions are more

and

of

They reduce the environmental impact of

products. Email advserv@uidaho.edu to opt out of the print edition and get the online magazine delivered to your email inbox. Read it online at uidaho.edu/magazine.

University of Idaho research drives our state’s economy and provides innovative solutions to our most vexing challenges.

This spring, we celebrate reaching our long-pursued goal of R1 research classification from the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. Joining the top tier of research universities in the country brings prestige to the tremendous work we already do across the state. More importantly, the designation allows us to better compete for research dollars, 80% of which go to R1 institutions.

The new classification verifies the remarkable growth of our research enterprise. We’re national leaders in water, forestry, wildfire, agriculture and soil health research. We set a U of I record last fiscal year with nearly $136 million in research expenditures, more than all other private and public Idaho educational institutions combined.

This issue of Here We Have Idaho highlights some of the innovations, creative solutions and practical community-building ventures we have completed.

Our drone lab supports research across the state, and we’ve expanded it to build and repair our own drones. Another team of students and faculty members at U of I Coeur d’Alene is working with the U.S. Forest Service to design an autonomous robot that can identify and kill weeds in large tree nurseries.

U of I integrates STEM education with Indigenous perspectives to address natural resource and land-use challenges, while fostering educational partnerships for students. In the Department of Movement Sciences, a faculty member and student are designing a program to keep ROTC cadets healthier.

Our medical education faculty members and students research dementia and study prevention.

Research plays a central role in the U of I student experience. Student research featured in this edition includes stories about virtual fence ear tags for cattle and insects’ role as water-quality indicators, among many others.

If you’re like me, you’ll appreciate the depth and breadth of U of I research celebrated in this issue and on display throughout our state each day.

Go Vandals!

Sincerely,

C. Scott Green ’84 President

Here We Have Idaho

The University of Idaho Magazine Spring ʼ25

President C. Scott Green ’84

Co-Chief Marketing Officers

John Barnhart

Jodi Walker

Executive Director, U of I Alumni Association

Amy Lientz ’95

Alumni Association President Jon Gaffney ’08

University of Idaho Foundation Chair

Clint Marshall ’97

University of Idaho Foundation CEO

Ben McLuen

Managing Editor Jodi Walker

Layout/Design

Karla Scharbach ’87

Editor

Joy Bauer ’98

Writers and Contributors

Ralph Bartholdt

Leigh Cooper

David Jackson ’93

Danae Lenz

Todd Mordhorst ’99

John O’Connell

Alexiss Turner ’09

Emma Zado ’23

Photography

Ralph Bartholdt

Idaho Visual Productions

Garrett Britton

Melissa Hartley

Christopher Giamo

For detailed information about federal funding for programs mentioned in this magazine, see the online version of the relevant story at uidaho.edu/magazine.

University of Idaho is an equal opportunity, affirmative action employer and educational institution.

© 2025, University of Idaho

Here We Have Idaho magazine is published twice per year. The magazine is free to alumni and friends of the university. University of Idaho has a policy of sending one magazine per address. To update your address, visit uidaho.edu/alumni/stay-connected or email alumni@uidaho.edu. Contact the editor at UIdahoMagazine@uidaho.edu.

The iconic P1FCU Kibbie Dome turns 50 in 2025.

Photo by Melissa Hartley

GEMS

SPRING ’25

Here are some shining examples of U of I’s impact and excellence.

Read more articles at uidaho.edu/news or follow University of Idaho on FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM and X

2025 is the 100TH

$7.8 Million

Grant to support young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

$136M

10%

Increase in doctoral student enrollment in 2024 over the previous year.

1ST anniversary of the College of Graduate Studies.

24,000

Rare and unique books in the U of I Library Special Collections and Archives.

U of I ranked the best of college dorms in Idaho by University Magazine.

In research expenditures at U of I last fiscal year, surpassing all other Idaho research institutions combined and setting a new record.

2,025

First-time students enrolled in Fall 2024, the largest in U of I history.

The P1FCU Kibbie Dome celebrates a halfcentury in 2025. Read more on page 14.

Ranked Best Value Public University in the West by U.S. News and World Report for the fifth consecutive year. NO.1

54

U of I researchers are top in their field, according to Stanford/Elsevier, more than all other Idaho research institutions and Idaho National Lab combined.

37,200+

Since the founding of the College of Business and Economics. TOP 6%

U of I’s ranking among all public universities on the Top Public School list.

Donors to the Brave. Bold. Unstoppable. campaign since 2015. Thank you!

100 years

FOCUSED ON MOVEMENT

U of I research could create a healthier US military

By David Jackson ’93

Photos by Melissa Hartley

Department of Movement Sciences Associate Professor Joshua Bailey waited four years to reboot his research on injury risk profiles and prevention after it was shut down because of COVID-19 in 2020.

Rafe Richardson, a junior majoring in biological engineering and an Air Force ROTC cadet, wanted to learn more about musculoskeletal injuries while pursuing his dream of becoming a doctor.

Together, their research through the College of Education, Health and Human Sciences could help ROTC programs nationwide keep their cadets healthier by teaching them how to move more effectively.

“Both the Army and Air Force are employing civilian strength conditioning coaches on some of their bases because they see the value in this type of program,” Bailey said. “Our goal is to get cadets at the ROTC level to focus on this training so they start with a solid understanding of how to stay healthy.”

Jumping right in

As the son of an Air Force pilot, Richardson knew all about the physical demands of being in the military long before he thought about joining ROTC.

After listening to Bailey speak at an Air Force ROTC event in 2024, he chased the professor down to discuss the specifics of Bailey’s study. It was exactly the kind of research opportunity Richardson was seeking.

The research team spent several months recording and analyzing participating cadets’ movements. The cadets performed lunging, squatting and jumping exercises so their mechanics could be recorded and studied.

“What we’re doing is testing their strength and their movement ability,” Richardson said. “We look at the way their entire skeleton moves as they land. We’re measuring their ground reaction force — how their feet and legs are interacting with the ground.”

U of I’s Movement Sciences team records performance mechanics during exercise routines.

Because military members are constantly in motion, they are susceptible to movement-related injuries. Bailey and Richardson are looking for traits that could predict a cadet’s specific risk factor for injury.

“When their foot hits the ground, we can see exactly how much force they’re exerting,” Richardson said. “We can also see how that force moves up their leg based on their movement patterns. From there, you can calculate how much stress is being put on joints, hips, knees and ankles.”

In addition to sharing data from this study with interested ROTC programs around the U.S., Bailey plans on including this information in an application submission for a 2025 U.S. Department of Defense grant designed to address the physical and mental health of members of the U.S. military.

Basic understanding

Richardson and Bailey are running a second session of analyzing ground reaction force for ROTC cadets during the Spring ’25 semester before moving on to phase two of their study — intervention with cadets.

Based on data provided by cadets regarding selfreported injuries or health issues, the U of I team will use the information they compiled to create profiles for each cadet offering suggestions to reduce injury risk.

“These tasks we are doing with the cadets have optimal movement patterns to them,” Bailey said.

“Deviations from the optimal movement pattern may indicate either weaknesses or risk factors for injury. We want to show them how to improve their movement patterns, which would then decrease the chance of injury.”

Richardson learned about this project because of his involvement in ROTC, but as someone with medical school in his sights, he saw it as the perfect way to combine his passions for the military and the medical world.

“I would love to make a large impact in ROTC and other training programs with this study,” said Richardson, who received a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship from U of I’s Office of Undergraduate Research for his contributions to the project. “In basic training, you hear about people getting injuries from performing routine exercises. It’s not because they are in horrible programs — it’s because they haven’t been taught about biomechanics and how to correct their movement. So hopefully our study can start that conversation.”

Rafe Richardson

The analysis reveals flaws in movement mechanics, which allows the U of I team to show cadets how to decrease their injury risk.

IDAHO’S RESEARCH POWERHOUSE

U of I earns elite R1 status

University of Idaho is among the top research institutions in the United States after earning the R1 designation in the 2025 Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education this spring.

U of I is the only higher education institution in the state to receive the distinction, which is garnered by less than 4% of all U.S. higher education institutions.

To classify as an R1 institution, universities must:

• Have at least $50 million in annual research expenditures.

• Grant at least 70 research doctorates.

When President Scott Green joined the university in 2019, he made reaching R1 status a top goal. U of I increased its research expenditures to $135.9 million in 2023 and grew its doctoral programs by 18.4%, reaching an all-time high of 606 doctoral students in Fall 2024.

U of I is also home to 54 scientists recognized in the prestigious Stanford-Elsevier Top 2% Scientists List, more than all other Idaho research institutions and Idaho National Laboratory combined.

Why R1 status matters:

• Federal and state agencies and private organizations recognize R1 institutions’ capacity to conduct groundbreaking studies and tackle complex societal issues.

• Top-tier faculty and ambitious graduate students gravitate to R1 universities, enhancing academic excellence and driving innovation.

• Undergraduate and graduate students gain hands-on opportunities to engage in cutting-edge research, preparing them for leadership in academia, industry and beyond.

• R1 status enhances the university’s reputation locally, nationally and internationally and positively influences rankings, which can increase enrollment and funding opportunities.

• States with R1 institutions attract businesses and industry, bringing jobs, innovation and economic growth.

MAPPING THE FUTURE

U of I’s drone lab spearheads aerial monitoring for rangeland management

By Ralph Bartholdt

a

of over a dozen operational

are revolutionizing research by enabling researchers to cover more ground and measure data that might be difficult to obtain using traditional field methods.

Photos by Garrett Britton

U of I’s drone lab boasts

fleet

drones. Drones

The Curlew National Grassland is 50,000 acres of rolling prairie in Oneida and Power counties dotted with weather-worn farm buildings that lean precariously in the sun and wind. The grasslands are visited seasonally by flocks of migrating birds and are home to sharptailed and sage grouse.

“It’s one of those amazing places that you would never find by accident as you drive through the state,” range ecologist Jason Karl said. “It’s way out there in the southeast corner of Idaho, pretty remote.”

Karl, professor in the College of Natural Resources and director of the Rangeland Center at University of Idaho, will visit the grasslands often in the coming years. He and Eric Winford, a research assistant professor and associate director of the Rangeland Center, have a research project at the grasslands where, with the help of students, they will make regular drone flyovers to document changes in vegetation in response to land management.

As part of his job as a professor, Karl operates U of I’s drone lab, an interdisciplinary research and teaching group located in the Integrated Research and Innovation Center (IRIC) on the Moscow campus. The lab is the epicenter for drone projects led by professors who are part of the lab. Research associated with the lab includes wildland fire recovery research, stream restoration monitoring, weed treatment and seed application, and forest inventory projects. Most of the lab’s projects are carried out by graduate students, and results are

directly used in managing Idaho’s agricultural and natural resources.

When he came to the university almost a decade ago after working as a scientist for the USDA’s Agricultural Research Service, Karl was already heavily invested in drone research.

“The dean at the time suggested that faculty on campus doing drone research should coordinate their efforts,” Karl said.

He helped assemble the university’s first drone summit where U of I faculty members and students shared how drones were being used in research and teaching.

That was the genesis of the drone lab in IRIC 205.

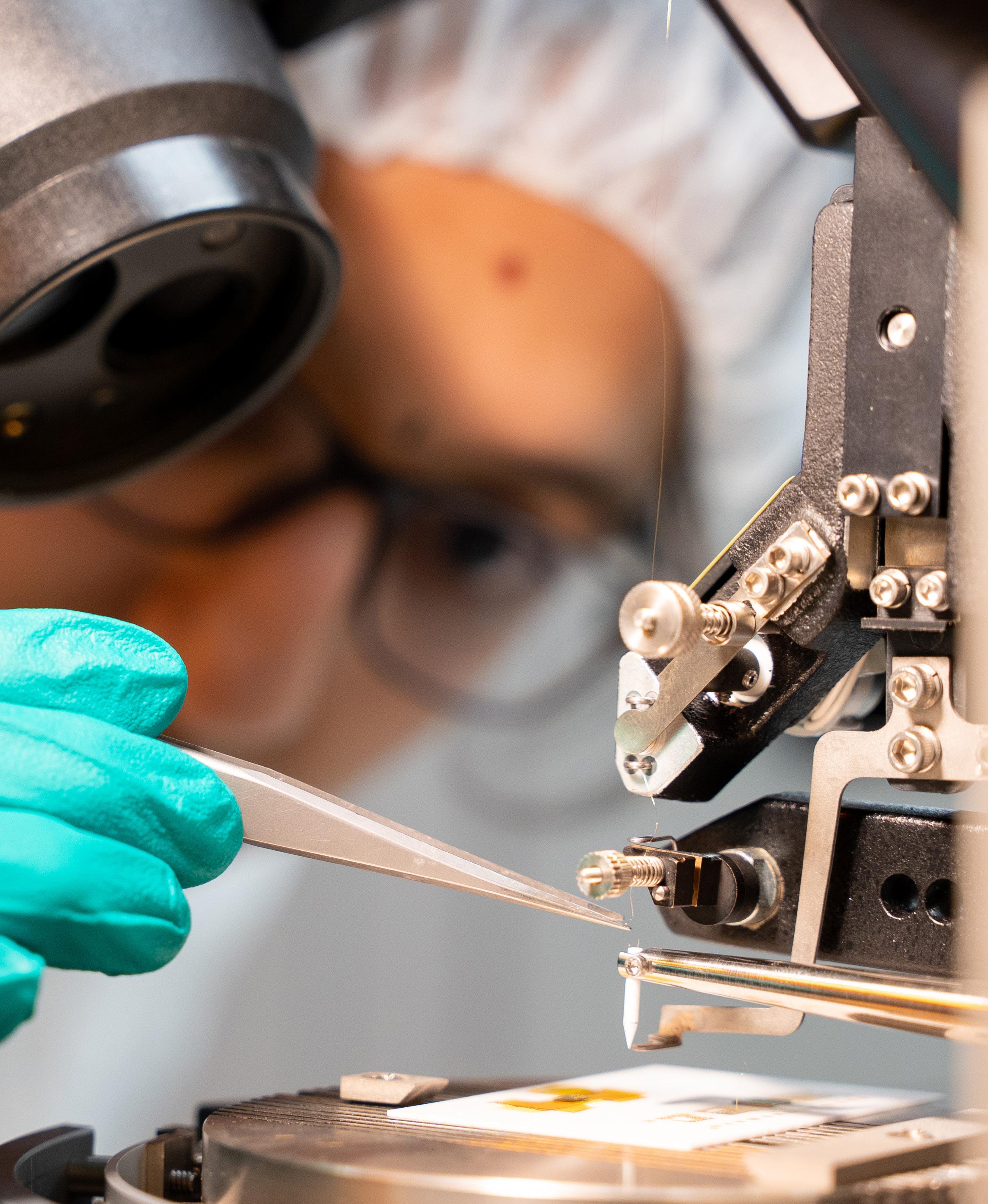

In the well-lit, glass-walled room, drones are modified and repaired. Drone pieces clutter the lab’s work benches, and a variety of drones in many sizes — some working, others defunct — are stacked on shelves or hang from the ceiling.

Graduate students in the lab work with faculty members from the College of Natural Resources, the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences, College of Science and College of Engineering.

Karl and Winford’s project on the Curlew grassland, funded by the U.S. Forest Service, uses drone mapping to explore how grazing during different seasons affects the abundance of invasive grasses and wildfire fuels on rangelands. Another Rangeland Center project monitors rangeland and riparian restoration projects in southern Idaho.

Professor Jason Karl, from the College of Natural Resources, inspects a drone that is used for forest inventory research.

“A large part of both these projects is drone-based monitoring,” Karl said. “Drones let us cover more ground and measure things that would be difficult with traditional field-based methods.”

Without drones, some aspects of the projects would be too labor-intensive and almost untenable.

As part of its inventory, the lab employs a dronemounted LiDAR sensor for high-resolution 3D mapping. LiDAR, which stands for light detection and ranging, uses laser pulses to measure distances and create 3D maps of land surfaces. The drone LiDAR sensor is used to monitor forest inventory and stream restoration, measure snow depth, estimate stockpile volumes and track wildfire recovery.

“We’re one of the few groups that has a drone-based LiDAR sensor that can be used on any U of I research project or for teaching,” he said.

A recent collaboration with the Intermountain Forest Cooperative led to a drone demonstration at the U of I Experimental Forest, during which the Idaho Forest Group agreed to donate one of its drones to the lab.

“It’s a type of drone we haven’t had before,” Karl said.

“It’s a vertical take-off and landing plane. It takes off

like a quadcopter then flips over and flies like a plane.”

The new drone can fly three times as long and cover three times the distance using the same-size battery as a regular drone.

“We’re training students on this type of drone that many people don’t have access to,” he said.

As drones become staple tools for research, demand for their use has grown, Karl said, and with the drone lab’s increased popularity, its function expanded.

Recently, the lab — which has over a dozen operational drones in its fleet — was designated a university service center, which allows it to provide drone data collection and analysis services to U of I departments and external partners, assisting in research where drones are needed.

“As the legal compliance, training requirements and costs of drones has increased, individual faculty members are having a harder time justifying buying their own drones to collect data, especially for small projects.” Karl said. “The drone lab can provide pilots and equipment to do that.”

The lab was recently designated a university service center, which allows it to provide drone data collection and analysis services to U of I departments and external partners, assisting in research.

A recent federal government mandate prohibiting the use of Chinese-made drones on federally funded projects beginning in 2025 may sideline several of the lab’s drones, Karl said. This includes a large drone used in Professor Leda Kobziar’s cutting-edge wildland fire and microbe research.

“This is the last month we can use this drone,” said Phinehas Lampman, a doctoral student who pilots drones equipped with various air samplers, meteorological sensors and cameras for remote sensing over wildland fires. “This drone will be grounded, and we’ll have to replace it with an American-made drone.”

The cost to replace the wildland fire drone will exceed $25,000, he said.

“The new regulations are causing us to retool an entire drone fleet,” Karl said.

Karl sees the mandate as a small temporary setback that could open opportunities for the lab to establish partnerships with U.S. drone makers, and the law could result in students building their own drones at U of I.

“We have a solid and cutting-edge curriculum that teaches students how to use drones in different applications,” Karl said.

He expects the lab to expand further, leading the way for regional drone research.

“I’d really like to see our drone lab at the forefront of developing the use of this technology in all kinds of research and teaching applications,” Karl said. “This is an area that is full of opportunities for innovation, and we at U of I are in a position to take advantage of those opportunities.”

FGOLDEN MILESTONE

for a Vandal landmark

1975-2025

ifty years after opening, P1FCU Kibbie Dome remains University of Idaho’s iconic indoor athletics complex. It has hosted countless sporting events, rodeos, powwows, festivals and concerts by world-famous musicians like Lionel Hampton, Macklemore and Kenny Rogers. Its uses remain broad, from a polling station to a gathering spot for the Vandal Family during times of grief and where they celebrate graduation. It was once where students registered for classes.

Delve into the history of U of I’s sports complexes:

1925

Football and baseball games are played on MacLean Field, an open lawn between the Administration Building and Memorial Gym named after former university President Alexander MacLean.

1937

Despite the hardships of the Great Depression, fans clamor for a more developed athletic facility. Neale Stadium, completed on the western edge of campus in time for the 1937 football season, uses the campus topography to create a horseshoe-shaped complex with wooden benches for several hundred fans. It lacks locker rooms and outdoor lighting.

1969

Harsh Palouse winters and time take a toll on Neale Stadium, and it is condemned due to soil erosion. Football home games move to Pullman and other locations.

1971

U of I begins the football season in its new Idaho Stadium, featuring concrete bench seating. Initially, Idaho Stadium was planned as an outdoor venue with a seating capacity of over 20,000, alongside a large indoor arena for basketball and cultural events. When financing fell through, campus leadership aimed for a multipurpose facility. The small Idahobased Trus Joist Corporation proposes a novel design to enclose the roof using engineered wood products instead of steel or aluminum.

Aerial view of Neale Stadium, 1947.

1975

William Kibbie, a student at U of I for less than a semester in the 1930s, donates $300,000 to kickstart fundraising for the 14-story tall roof. The Associated Students of U of I (ASUI) raises awareness and dedicates student fees to the project. The fully enclosed facility opens in 1975 under the name ASUIKibbie Activity Center.

2024

The structure is renamed the P1FCU Kibbie Dome after the Lewiston-based credit union P1FCU invests $5 million in a 10-year naming rights deal.

2025

To honor the ASUI’s legacy of support for the dome, a bronze monument of Joe Vandal is commissioned and will be installed near the dome.

Architect’s rendering of the ASUI-Kibbie Activity Center, 1971.

Front page of The Argonaut from Nov. 8, 1974.

ASUI-Kibbie Activity Center under construction, 1975.

Images provided by U of I Library Special Collections and Archives.

WORKING TOGETHER

U of I strengthens its relationship with area Native American tribes

By David Jackson ’93

Photos by Garrett Britton and Melissa Hartley

AUniversity of Idaho team is creating a transformative approach to solving complex natural resource and land-use challenges by integrating STEM-based learning with the perspectives of Indigenous communities at the K-12 level.

“When we have teachers learning from members of the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s Department of Natural Resources or at events at McCall Outdoor Science School (MOSS) to talk about water and land usage, they are better prepared to share Indigenous knowledge when they go back to teach,” said Shanny Spang Gion, a doctoral student in the College of Natural Resources.

The Center for Interdisciplinary Indigenous Research and Education (CIIRE) strengthens educational partnerships between U of I and its tribal nation partners by encouraging Native American K-12 students to not only think about attending college, but also to incorporate tribal knowledge into STEMrelated disciplines.

“What we want to create is a hub of information, a knowledge base,” said Vanessa Anthony-Stevens, College of Education, Health and Human Sciences associate professor of social and cultural studies and

co-principal investigator of CIIRE. “We want to bring diversity of thought to these discussions about the relationship between the land and its people.”

Creating the relationship

Partnering with Native American students begins with recruiting them to U of I. That’s where people like Dakota Kidder come in.

Kidder, program manager for U of I’s Tribal Nations Student Services, brings high school students to U of I through programs like Helping Orient Indian Students and Teachers into STEM (HOIST).

HOIST has relationships with area tribes, primarily the 11 Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) tribes, and notifies their schools about U of I events.

The MOU is an agreement between U of I and the affiliated tribes to strengthen their relationships and improve the quality of educational services and opportunities provided to Native American students at U of I.

All high school students in the MOU tribes who have completed the ninth grade can join HOIST.

HOIST summer camps at MOSS are STEM-oriented. Events include science-based activities — classes, field trips and workshops — as well as cultural activities and leisure events to round out their experience.

“In HOIST applications, we specifically ask them about their interests related to STEM,” Kidder said. “We want them to think about what kinds of STEM activities they are interested in as it relates to their culture and how they might use that knowledge.”

To support this idea, scholars in the Cultivating Indigenous Research Communities and Leadership in Education and STEM (CIRCLES) program serve as mentors for HOIST, showing ways Indigenous research addresses current social and environmental issues.

Another HOIST goal is to show students the support available once they arrive, such as information about financial aid and scholarships, scholastic advising and adjusting to life away from home.

“We want to prepare them for life on campus and introduce them to people who will ultimately help them be successful once they get here,” Kidder said.

Everyone contributes

Last summer, Cultivating Relationships (CR), an outreach and research-based project funded by the National Science Foundation, and the Coeur d’Alene Tribe coordinated a five-week course for 70 Plummer-area K-12 students.

CR’s mission is to partner K-12 teachers with tribal nations and U of I researchers to examine the

relationships between people, places, lands and waters through STEM learning.

The program, led by the Coeur d’Alene Tribe’s departments of Education and Natural Resources, exposed the students to environmentally focused questions and the idea that information from tribal sources should be considered when attempting to answer those questions.

One way Indigenous information is passed down is through storytelling by tribal elders, which was featured at the program.

“Storytelling from elders — knowledge holders — is very genuine,” said Spang Gion, a former tribal scholar with CR. “When students hear stories about land management, operational knowledge and values important to the tribe, they listen.”

The program also focused on establishing strong connections between teachers and students.

“It’s crucial for teachers to build that trust with their students,” Spang Gion said. “When we share stories about our land and about our water, we end up teaching each other and learning from each other about how to approach difficult questions.”

CIIRE, CR and other related programs aim to foster reciprocity between tribes and their communities, ensuring that the Indigenous knowledge tribes share benefits everyone, not just the tribes, Spang Gion said.

“We want to be intentional about starting, supporting and sustaining these relationships,” she said. “What we want to create is a space where we can ask questions and share stories which can lead us to possible solutions.”

Shanny Spang Gion

Vanessa Anthony-Stevens

Replicating wildfires to improve safety

Story by Alexiss Turner ’09

Photo by Melissa Hartley

University of Idaho students are developing a prototype to improve understanding of wildfire behavior and enhance risk mitigation and safety research. The project, a collaboration between the College of Engineering and College of Science, involves creating a device that produces embers to observe and test ember-structure interactions in controlled environments, mimicking real wildfire conditions.

“This isn’t just playing with fire,” said Peter Wieber, a recent biological engineering graduate who served on the team. “We’re providing a wildfire research tool for the world.”

In 2023, wildfires consumed 97,504 acres in Idaho, according to the Idaho Department of Environmental Quality, causing property damage, timber loss, exposure to smoke, watershed pollution and fatalities. Embers play a significant role. As a natural byproduct of wildfires, they can travel long distances and ignite spot fires.

Understanding ember interactions with natural and human-made materials is crucial for mitigating wildfire expansion and developing fire-resistant building materials, said Alistair Smith, project sponsor and Earth and Spatial Sciences professor.

“This device provides a safe way of understanding the mechanisms for how heat and fire impact everything from structures to plant physiology,” he said.

Smith’s team includes physicists, fire ecologists, chemists, plant ecophysiologists and remote-sensing scientists, all focused on improving the mechanistic understanding of fire in Earth environments. The student-designed prototype uses a motorized auger woodchip feed system and propane flame to output a steady stream of embers for 15 minutes without refueling, ensuring accurate assessments while minimizing risks.

Students conduct fire ignition simulation and testing using U of I’s ember generator in the IFIRE Lab, one of the only fire combustion labs on a university campus in the U.S.

Researchers uncover first evidence of a Mars spatter cone

Story by Danae Lenz

Postdoctoral researcher Ian T.W. Flynn identified a volcanic vent on Mars as a potential spatter cone, linking volcanic activity on Mars to similar activity on Earth. The work is in collaboration with Erika Rader, assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Spatial Sciences.

Flynn discovered the Martian feature strongly resembles Earth’s spatter cones through detailed morphological investigation and ballistic modeling, comparing it to one formed during the 2021 eruption of Fagradalsfjall in Iceland.

“Since spatter cones can only form in the right conditions, their presence gives us a benchmark to shoot for when simulating Martian volcanoes,” Rader said.

Spatter cones, created by hot lumps of flying lava falling to the surface during explosive eruptions, are found in many places on Earth, including Idaho’s Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve. They were long suspected of existing on Mars but, until now, there was no solid evidence confirming their presence.

The similarity between Martian and Icelandic spatter cones indicates similar eruption dynamics. This discovery expands the range of volcanic eruption styles possible on Mars. Flynn, now a professor at University of Pittsburgh, continues to collaborate with Rader.

U of I opens federally funded center to tackle rural issues

Story by John O’Connell

University of Idaho is now the home of the Western Rural Development Center (WRDC) — one of four rural development centers throughout the country. The center had been housed at Utah State University since 1999.

“The WRDC actively engages with local communities, translating research findings into actionable solutions,” said Paul Lewin, executive director of the new center. “By fostering collaborative projects that involve faculty from Western universities, the center contributes to the well-being of rural areas. It establishes U of I as a hub for joint, communitydriven initiatives.”

The WRDC, located in the Idaho Water Center in Boise, will also be involved in workforce development, educating community leaders on grant opportunities and informing public policy by identifying experts to write position papers on relevant issues.

ANGLER TURNED SCIENTIST

Scholar investigates the links between insects and healthy waterways

By Ralph Bartholdt

Jack Stafford stood knee-deep in the gurgling Gibbon River in Yellowstone National Park as water dripped from the grayling he had caught on a fly.

“I was standing there in this beautiful river holding this rare and beautiful fish with the sun shining on the hills and meadows, and I thought, ‘This is pretty great,’” he said.

Stafford, an undergraduate fisheries management student from Harrison, decided then that a career in fisheries biology may be worth pursuing.

While studying at University of Idaho’s College of Natural Resources, Stafford secured a grant from INBRE — the Idea Network of Biomedical Research Excellence. The group’s purpose includes funding projects that promote public health.

Stafford’s U of I curriculum and research are outdoor focused, and not usually associated with white lights and lab coats. However, the INBRE grant will help

pay for his work on two research projects in Chris Caudill’s lab in the College of Natural Resources.

One of the studies involves sampling water from streams in the Clearwater River drainage to identify aquatic insects that serve as indicator species of healthy rivers. That means the bugs’ presence indicates the water is clean and healthy. If the bug isn’t there, it could suggest stream quality problems.

“If these insects are found in rivers and streams, it shows the water is good quality, and their absence can mean there’s a problem like a type of pollution that may also affect communities and people living alongside the river,” Stafford said.

Other environmental factors with broader implications on water quality and human health may also affect species abundance.

“Our work on invertebrates is aimed at understanding how invertebrate diversity in streams changes within watersheds and how species

Fisheries management student Jack Stafford

Photos by Melissa Hartley

will respond to environmental change because invertebrates are critical to supporting trout and salmon in Idaho streams,” Caudill, an associate professor of fisheries, said.

The study includes refining how elevation changes influence aquatic insect populations and species and using the data as baseline information for climate change monitoring, he said.

Stafford’s second study explores the distribution of two rare species of stonefly — called snowflies — found only in Latah County. These insects emerge during winter and mate on the snow.

The project aims to map the two species’ distribution, with a key focus on developing molecular tools to significantly enhance the ability to detect the stoneflies in a wider area.

Molecular tools include identifying specific genetic markers, DNA “barcodes” that could help detect stonefly species from environmental samples like water or sediment.

“The broad goal is to better define the habitat and distribution of the species so conservation guidelines can be developed,” Caudill said.

The work on snowflies is done in collaboration with Idaho Fish and Game and U of I’s Barr Entomological Museum.

Stafford said his interest in biology and fisheries developed gradually from a natural curiosity about aquatic ecosystems while living along Lake Coeur d’Alene and spending free time popping lures into the water.

“Fishing was just something we did as a family, and I learned to fish early on,” he said.

His mother, a former bass tournament angler with a few wins under her belt, encouraged Stafford to take up angling. However, his primary influence was two Lake City High School teachers. During a summer field trip to Yellowstone National Park, they inspired Stafford to survey grayling in the Gibbon River.

The outdoor science project motivated him to enter the biology field, and because he was already an angler, fisheries seemed a worthwhile pursuit.

“Jack has been an enthusiastic student of freshwater ecology and dedicated in the lab and field,” Caudill said. “His love of fishing blurs with his interest in freshwater ecology and fish biology — he is as likely to share a story about trying to find a remnant population of redband trout in a tiny stream as he is to share pictures of big fish.”

Stafford collects insect larvae to take back to the lab where they are identified and preserved.

FROM HAVOC TO HARVEST

Project Evergreen provides an innovative approach to weeding large tree nurseries

By

Todd Mordhorst ’99

Photos by Ralph Bartholdt and Melissa Hartley

The team unveiled its weed-killing robot last summer at the U.S. Forest Service nursery.

Project Evergreen team member Kevin Wing.

Each year, Professor John Shovic awards the “Crown of Destruction” to the student who wreaks the most havoc in the Center for Intelligent Industrial Robotics in Coeur d’Alene. The tongue-in-cheek honor may go to Brent Knopp this year, but the solution arising from the damage could boost reforestation efforts in Idaho and nationwide.

The U.S. Forest Service called on Shovic and his students to develop an efficient solution to eliminating weeds from its nurseries. The U of I team embarked on Project Evergreen to build a machine that can autonomously move through a nursery, locate, identify and kill destructive weeds.

As Knopp and the Project Evergreen team built their robot designed to clear weeds from tree nurseries, challenges emerged. But when it comes to innovation, sometimes things must break before a breakthrough.

“The high voltage on the weed-killing mechanism was coupling with the frame, and we blew up the robot two days before a demonstration for six nurseries,” Shovic said. “That’s when Brent earned the ‘Crown of Destruction.’ We give it to the student that does the most damage — whoever does the best job Vandalizing stuff.”

Nurseries can spend up to $100,000 annually on weeding and frequently struggle to find workers willing to do the monotonous task. The U of I robotics group tackled the challenge by designing a GPS-guided robot equipped with a camera and an AI system to identify weeds and a subsystem to kill the weeds.

Shovic tapped Garrett Wells to lead the project. The computer science doctoral student welcomed the challenge.

“It was definitely daunting to have a project that has so many different components, from hardware to software,” said Wells, who earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at U of I. “We’re really fortunate with the people that came together on the team.”

Knopp earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering before starting his master’s in computer science, so the team relied on his expertise to develop the weed-killing component. After much brainstorming and experimentation, the Navy veteran designed an electric zapper to electrocute and kill weeds.

The explosive setback days before their demonstration eventually led to solutions. Redemption came last summer when the team demonstrated its prototype robot for the Forest Service.

“It felt really great to show them our work,” Knopp said.

The next steps for the project include adding an autonomous computer that identifies weeds to run the AI program. After that, all the computer systems must be integrated. Commercial production of the weedkilling robot is likely years away, but the students continue to expand upon Project Evergreen, gaining tremendous skills in the process.

“This project is everything I envisioned for graduate school,” Knopp said. “I wanted to apply machine learning to robots, and the scope of work in this project is great experience.”

The team uses GPS to guide its robot and AI to identify destructive weeds. U of I master’s student Brent Knopp, left, worked on the weedzapping mechanism while doctoral student Garrett Wells, right, led the team and helped integrate hardware and software.

TEACHING AI TO TRANSLATE

Artificial intelligence elevates music education accessibility

By Leigh Cooper

Photos by Christopher Giamo and Garrett Britton

Miranda Wilson, professor of cello and music history

For their co-authored book on the history of teaching string instruments, Miranda Wilson and two colleagues read every book they could find about playing violin, viola, cello or double bass. They turned to Google Translate for help with tomes unavailable in English.

“I read so many completely brilliant books and articles that had never been translated into English, and I thought we were missing out,” said Wilson, a University of Idaho professor of cello and music history. “I realized, if I didn’t translate these books, nobody else was going to.”

One book stood out for Wilson — “The Mechanics and Aesthetics of Cello Playing,” by celebrated professor and cellist Hugo Becker (1863-1941), published in 1929.

But diving straight into a translation was impossible. The book was written in German, and although Wilson was trained in the language, she didn’t feel experienced enough to tackle a translation of century-old German. Additionally, the book’s specialized terminology would have challenged a hired translator.

First, there’s the cello lingo, which includes instrument parts and classical music jargon. Second, when Becker wrote his book in the early 1900s, he wanted to incorporate information from the emerging scientific field of physiology. To write about the anatomically correct way to play the cello, he hired physiologist Dago Rynar as coauthor for his expertise in anatomical vocabulary.

For assistance translating the 100-year-old jargon-filled German book into a sharable teaching aid in English, Wilson turned to the artificial intelligence experts at U of I’s Institute for Interdisciplinary Data Sciences (IIDS), which provides data and computing support for U of I researchers.

AI avengers assemble!

In Fall 2024, IIDS launched the Generative AI Fellowship to help faculty members use AI in their research. Michael Overton, associate director of IIDS, oversaw the first cohort of four participants.

“We have a good technical team and the knowledge to assess the ethics and biases aspects of AI, but we started this fellowship to learn how scholars wanted to use AI,” he said.

Cello

Upon joining the fellowship, Wilson sat down with Director of IIDS Research, Computing and Data Services Luke Sheneman, who was excited about the opportunity to translate Becker’s book. For Wilson, the chance to translate the book meant creating a new teaching tool.

“The more I read, the more I felt that the profession needs this,” Wilson said. “Becker worked with some of the most famous 19th-century composers, such as Johannes Brahms and Clara Schumann, and throughout the book he writes about the interpretation of their music, advice that he must have gotten from the composers themselves.”

The team started with a poorly scanned PDF version of the book, and Sheneman and IIDS web developer John Brunsfeld used numerous generative AI techniques to translate the contents. Generative AI is artificial intelligence that learns from existing content to create new content including images, videos, text, audio or computer code.

First, the AI team converted the PDF scanned images of the book’s pages into text, because AI specializing in language translation requires text files. They automatically ran each scanned page through a large “multi-modal” computer vision model, which takes images, speech and video and converts them into

a different form of communication. In this case, it converted PDF images of words to text and kept them in German.

Then the big lift — translating German, cello jargon and anatomical terminology into English. Sheneman’s team tasked five different large language AI models to individually translate the book from German into English.

“I used an ensemble of large language models because all the models have distinct strengths, weaknesses and biases based on how they were trained,” Sheneman said. “When they get stuck, they all sometimes make stuff up.”

Sheneman needed to provide the language models prompts — commands that tell the program what the user wants — and he learned to include context about the book’s content and audience. He discovered that asking AI for help with writing better prompts improved translation.

“Translation’s hard,” Sheneman said. “There’s a lot of subjective decisions that are made, and a lot of it’s done in the context of your audience.”

When complete, all the first translations were different.

Anatomical diagrams posed a challenge for AI when translating the cello manual.

“There were some hilarious mistranslations,” Wilson said. “In a passage about how you should not make an unpleasant sound, it got confused by a German colloquial expression and translated it as ‘you must not be a celery munching cellist.’”

Finally, Sheneman pulled out a powerful reasoning model, which spends time “thinking” about the content it’s given. The model looked at outputs from the original five AI models, identified where they disagreed, analyzed those points of contention and resolved the disagreements.

Although not perfect, the translation was astonishingly accurate, Wilson said.

“I later asked an expert in German translation if there were any mistakes. And he said, ‘No, this is flawless,’” she said. “I was shocked because I had never had an experience of artificial intelligence translation that I hadn’t had to change a lot.”

Access to education and technology

As part of the IIDS fellowship, faculty members and AI experts discussed ethics and responsible uses of AI.

“If I had had a huge grant, I would have hired a human translator to do it,” said Wilson, when comparing the $150 price tag of IIDS’s work to the thousands of dollars a translator would have cost.

“But we are making knowledge more accessible. A lot of people who are teaching cello don’t have access to teaching tools, and many simply can’t afford them. Becker’s book is such a gift, and it’s tragic to me that it’s not better known.”

There is one English translation of Becker’s book, but it is on delicate microfilm and hard to access. Wilson plans to publish her translation as an Open Access educational resource e-book through the U of I Library, accessible for the public. The book is in the public domain, meaning no copyright will be violated.

The success of the generative AI fellowship led IIDS to continue the program in Spring 2025.

“If someone’s interested in using AI but they’re scared because they don’t know how to use it, that’s exactly the kind of person I want to work with. I hate barriers when it comes to accessing technology, especially in science,” Overton said. “Your ideas should be your only limitation.”

Luke Sheneman, Institute of Interdisciplinary Data Sciences’ Research, Computing and Data Services director.

OUR BIGGEST, BOLDEST PHILANTHROPIC CAMPAIGN EVER IS MAKING HISTORY

Thank you, Vandals! Your extraordinary generosity has contributed $500 MILLION to advance student success, sustainable solutions for our state and a thriving Idaho.

So far, that’s: $155 MILLION for scholarships $245 MILLION for research, faculty and academics $100 MILLION for facilities, campus enhancements and community outreach

Now, let’s keep the momentum going to maximize our collective impact because every gift makes a difference.

How do we know? Vandals and friends have made more than 150,000 gifts. 85% of those gifts are $500 or less.

Together, we are building a thriving Idaho — and world — for all.

Make your gift before Dec. 31 to be part of this historic campaign.

VANDAL GENEROSITY

DRIVES UNSTOPPABLE IMPACT

Dear Vandals,

We are thrilled University of Idaho is recognized as an R1 institution, placing us among our land-grant research university peers, including Colorado State and Washington State University.

This is a new era of opportunity, fueled by our deeply generous Vandals and partners. Together, we have created new endowed faculty positions, increased scholarships and hands-on research, built world-class facilities and so much more that delivers real value to Idaho and beyond.

But our work is not finished. As we push toward the Brave. Bold. Unstoppable.

campaign finish line on Dec. 31, your gift will accelerate the university’s groundbreaking achievements and boundary-pushing innovation for the two million Idahoans (and counting!) we serve.

The time is now. Please join us and the thousands of Vandals ensuring our alma mater’s continued success and growth. What we can accomplish together has no limits. Thank you for your engagement, enthusiasm and philanthropy that is transforming U of I and building a thriving future for all.

Go Vandals!

Scan the QR code to lend your support.

MAKE A GIFT. BE UNSTOPPABLE.

Vandals, volunteers and campaign co-chairs (left to right) Bill Kearns ’81, Lisa Grow ’87 and Clint Marshall ’97.

BOLD INVESTMENTS

CREATE A THRIVING IDAHO

Making a difference

Donors, partners and U of I elevate Idaho’s workforce and industries

Facilities like the Idaho Center for Plant and Soil Health at U of I’s Parma Research and Extension Center engage students, researchers and industry partners to solve some of Idaho’s biggest problems.

Funding from agricultural stakeholders and other donors was crucial to constructing the center, which opened in 2024 and focuses on research in hops quality, microbiology, plant pathology and nematodes — microscopic worms that can devastate Idaho potatoes, sugar beets and cereal crops.

Investment accelerates impact

In October 2024, the J.R. Simplot Company Foundation, Idaho Potato Commission, Amalgamated Sugar, McCain Foods and other stakeholders established the Saad Hafez Presidential Endowed Chair in Nematology. Named in honor of U of I’s now-retired extension specialist and professor of nematology, the position will be located at the Parma Research and Extension Center.

Agriculture industry partners also help fund graduate student research into bacterial and fungal diseases of onions, potatoes and sugar beets.

Endowed positions and graduate student funding attract world-class faculty, top students and research grants — the essential components to advancing science and technology, training a skilled workforce and keeping Idaho’s industries and communities thriving for decades to come.

“The key thing that made this possible was partnership.”

Michael Parrella, dean of the College of Agricultural and Life Sciences

QUICK FACTS

• Agribusiness is responsible for $1 of every $6 dollars in sales in Idaho.

• Every $1 invested in U of I’s nematology program has returned $53 to Idaho agriculture.

• Established at the urging of local farmers, the Parma Research and Extension Center has served southwest Idaho for 100 years.

“Because of your support, I have had countless opportunities to put my knowledge into action through class, labs and different research.”

Regan Stansell, biotechnology and plant genomics major

Idaho Center for Plant and Soil Health

REVOLUTIONIZING RANGELAND

Resources, helped develop an ear tag that uses virtual fence technology to control the movement of

Emma Macon’s research yields optimal ear tag for

managing cattle on the range

By Ralph Bartholdt

Photos by Melissa Hartley

Emma Macon enrolled at University of Idaho to study rangeland science like her father, who is an extension agent in the blue oak woodlands northeast of Sacramento, California.

At U of I, Macon anticipated taking part in research projects that would guide her career out of doors.

“My sister and I spent a lot of time in the grasslands with my dad, who we called a grass geek because he knew the names of all the plants,” she said. “I wanted a job working outside, and U of I has a reputation for getting students the skills they need to do that.”

Working with Professor Karen Launchbaugh at the university’s Rangeland Center, Macon joined a project that explores virtual fence technology. The

technology uses location devices on the collars and ear tags of livestock to create a virtual fence that allows ranchers to control cattle without using barbed wire.

Standard barbed wire fencing is expensive to maintain and can cause injuries to livestock, people and wildlife, including elk and pronghorns. It also fragments landscapes, disrupting wildlife migration patterns. Scientists are developing cost-effective virtual — or invisible boundary — fences for better land management and wildlife conservation.

As part of her student research, Macon wanted to know what limiting factors must be addressed when outfitting cows with virtual fence ear tags.

Emma Macon, a senior in the College of Natural

cattle on the range.

“We wanted to know what size and how heavy ear tags can be before they hinder cattle, and how small we could make them and still incorporate all the radio devices that are necessary to monitor and control cattle,” she said.

Working in the rangeland lab in the College of Natural Resources, Macon spent hours weighing prototype ear tags made of hard plastic that would contain radio receivers that used electric shocks to train cows to stay within boundaries. Last summer, she tested the various sizes and weights on cattle at the university’s beef center, monitoring behavior and side effects such as infections and ear injuries.

“A cow’s ear only has so much real estate on it, and putting extra weight on the ear can hurt animals, affecting their eating habits and movement,” said Launchbaugh. “Knowing just the right size and weight of a tag is really important.”

Macon is the first student researcher to consider ear tag size, weight and placement on the ear when applied to virtual fence research. She earned a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship from the Office of Undergraduate Research to conduct the research funded by the Department of Agriculture.

The scholarship helped pay for travel costs as well as her time spent in the lab and outdoors monitoring the ear tags’ effects on rangeland livestock.

“We needed to know the size and weight of a plastic ear tag that didn’t bother cattle and impede their behavior or their hearing, and the mobility of the ear,” Macon said.

She tagged cattle, observed their behavior and analyzed data to determine the optimal ear tag size.

Her research, in conjunction with other virtual fence research conducted at the Rangeland Center, used radio fences that are less costly than GPS-based models, weigh less and are more accurate.

GPS virtual fences are accurate to within about 10 yards, Launchbaugh said, while Macon’s radio ear tags are accurate to within a few feet.

Macon’s virtual fence research was a highlight of the Spring ’25 graduate’s college experience.

“I really enjoy helping develop this technology that could be a real boon to ranchers, reduce the number of fences on the range and also be beneficial to cattle by not hindering them with heavy equipment,” she said.

Emma Macon and Hope DiAvila, of the Rangeland Center, conducted ear tag research on cattle at the beef center.

Virtual fence ear tags use radio fences that are less costly than GPS-based models, weigh less than collars attached to cattle’s necks and are accurate to within a few feet.

SGIRLS WHO INVEST

Student ambassador Catherine Hubinger maximizes University of Idaho career opportunities

By Ralph Bartholdt

Photo by Garrett Britton

lang terms for money include, “bread,” “dough” and “lettuce.”

Junior business major Catherine Hubinger prefers “cabbage,” because, as a fourth grader participating in a school project in Eagle, she grew one.

It was huge.

So big, in fact, that the vegetable she planted from seed in her mom’s garden earned her a $1,000 prize, a front-page newspaper picture and a state award.

That’s a lot of “cabbage” for a 9-year-old, Hubinger said.

With the help of her parents, she invested the money, and her passion for growing green stuff was born.

As a finance and accounting major in the College of Business and Economics, Hubinger augmented what she already knew about growing greenbacks at the college’s Barker Capital Management and Trading Program, as well as its Davis Investment Group.

These experiences landed her an opportunity as U of I’s representative for Girls Who Invest, an international program that teaches corporate finance to young women. As part of the program’s requirements, Hubinger attended a summer intensive at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

“The program’s goals include reaching a point where women make up 30% of the workforce in the investment industry, from the 10% it is right now,” Hubinger said. “It really provides student participants with a strong background across various sectors of the financial industry.”

Hubinger was the first woman in Idaho to be accepted into Girls Who Invest and is U of I’s student ambassador.

“I have recruited other girls and encouraged them to apply to the program,” she said.

Her experience with Girls Who Invest and two additional U of I investment programs, including the newly established Barker Trading Club, gave Hubinger a wealth of financial know-how that she hopes to turn into a career when she graduates Spring ’26.

“Ever since I first invested the money from winning the cabbage project and, later, taking a high school trading simulation course, I have loved to watch the markets move and investments grow,” she said.

Attending U of I was a no-brainer decision after visiting the campus her junior year in high school.

“To learn that U of I had a trading program and such a gorgeous campus, I was like, ‘I need to go here,’” she said.

Business Professor Duff Berquist, Barker’s program director, was acquainted with Girls Who Invest and realized there was a dearth of student ambassadors from Idaho.

“Catherine seemed like a great candidate. She was knowledgeable from having taken advantage of our investment groups and was on track to do something bigger,” Berquist said. “It’s a very competitive program and she came through it with flying colors.”

Hubinger, a member of Delta Gamma, said investing money and keeping up with business trends that affect investments has been the benchmark of her college experience.

“I have worked with large portfolios, from college to the corporate, and this summer I did equity research,” she said. “It’s fun to be contributing to a firm and working on funds which are managing money for all sorts of customers and companies. I find it fascinating and fulfilling.”

Junior business major Catherine Hubinger

KEYS TO LEARNING CLASS senior discovers his future while studying music from his past

By David Jackson ’93

Photos by Melissa Hartley

Senior Alexandro Aguilar came to University of Idaho in 2021 to study chemical engineering, but his enduring love of music, especially the Mexican folk music he grew up listening to in Payette, altered his course after only two weeks on campus.

Ironically, thanks in part to a scholarship from an engineer who graduated from U of I in the 1940s, Aguilar is now on a musical career path he wasn’t sure he could find.

Despite playing piano since age 8 and participating in his high school drum line for four years, Aguilar hesitated to study music in college because he wasn’t sure that degree would lead to a successful future. But after hearing his freshman roommate talk about what he was doing in his music classes, Aguilar felt conflicted.

He asked a faculty member if changing his major so soon was a good idea. The instructor told Aguilar she got an undergraduate degree in engineering and later returned to earn a graduate degree in theatre arts, which was her true passion.

“She told me she wished she had followed her heart and studied theatre from the start,” said Aguilar, a first-generation college student. “That was the sign I was looking for.”

After signing up for music classes, Aguilar began thinking about what direction he should go with his studies. He kept coming back to a comment made by one of his professors.

“The quote is ‘strive to be known as the only one who does what you do’ — I’m not sure where I stole it from,” said Dan Bukvich, university distinguished professor at the Lionel Hampton School of Music (LHSOM). “I also do my best to remind students that they are here to major in themselves.”

Alexandro Aguilar

Aguilar, whose parents were born in Mexico, grew up in a primarily Spanish-speaking home. Curious to learn more about the composition of the music he grew up listening to, he spent two weeks in Mexico City in 2024 researching the work of Manuel Ponce, an influential Mexican folk music performer.

“To understand a musical piece, a performer must research the conditions under which it was created — musical, cultural and political,” said Roger McVey, professor of piano at LHSOM. “This process of study, thought and consideration is necessary to bring artwork to life — that’s what musicians do.”

The trip was funded by the Bert Berlin Scholarship Enhancement Humanities Award through the College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences.

Berlin ’47, a mechanical engineer, established the scholarship endowment fund for undergraduate humanities students to support activities that enhance their personal development and educational growth.

“Research in music is a lot different than research in engineering,” Aguilar said. “When I started listening to different styles of music, I heard a piece by Ponce and got very emotional because it sounded like Mexico to me. But I didn’t know much about Mexico. I wanted to learn more about why those sounds meant something to me.”

Born in Mexico, Ponce played piano and guitar and studied classical music composition in Europe in the early 1900s before returning to Mexico to teach.

“I think there’s some things Ponce wrote in his music, a specific kind of technical focus, that you don’t find with most European composers,” Aguilar said. “The rhythmic aspect, the horns and mariachis … his music is very unique because it combines his classical training and his Mexican background.”

Aguilar also spent time with his parents in Mexico City. As they described the sights, sounds and history of the area they grew up in, Aguilar began to understand the cultural nuances of the music he was studying.

“I was born in the U.S., and even though I speak Spanish, I always felt like I wasn’t fully connected to my culture,” he said. “Being able to finally make that connection through my music has helped me bridge that gap and has made this research very special to me.”

Aguilar’s research in Mexico City, combined with his love of playing music and his familiarity with the classroom from serving as a teaching assistant for Bukvich, helped him realize he’d eventually like to become a music teacher.

“Alex is a dedicated, inquisitive student and a natural leader,” McVey said. “He is a bright light who enriches the people around him.”

Alexandro Aguilar traveled to Mexico to research the work of Mexican folk music performer Manuel Ponce.

THE TIME IS NOW

Addressing key risk factors could stall the global rise in dementia

By Emma Zado ’23

by Christopher Giamo

There are 55 million people worldwide diagnosed with dementia, a number expected to triple by 2050. But what if that rise could be stalled?

Dementia is a condition where cognitive decline negatively impacts daily living. It is caused by diseases that destroy nerve cells and brain function.

University of Idaho School of Health and Medical Professions Professor Thomas Farrer researches reversible cognitive decline and how untreated health conditions can mimic or increase the risk of dementia.

By analyzing public health data and studying brain scan images, he discovered that addressing certain risk factors can lead to a reversal of cognitive decline.

Photos

Professor Thomas Farrer

“Alcohol and opioid pain medication abuse is common in middle-aged and older adults,” Farrer said. “That substance abuse causes cognitive decline. If you were to get the necessary treatments and stop using those drugs, you can see improvement in cognition.”

Before teaching at U of I, Farrer practiced as a clinical neuropsychologist for eight years. His interest in dementia began during his training, where he enjoyed the mystery each case presented.

“Over time, I realized that there’s no cure for dementia,” he said. “If we don’t have a cure, and the number of people with dementia continues to go up dramatically, we need to do everything we can to prevent it from happening.”

Many things can negatively impact the brain and increase the risk of dementia or cause cognitive problems later in life. However, some health conditions that increase the risk of dementia are preventable or treatable.

Sleep disorders like insomnia, mental health conditions like depression and even addiction are among the treatable health conditions that are associated with an increased risk of dementia and cause of cognitive decline in older populations, Farrer said.

Depression in a 75-year-old can appear to be dementia. An individual may experience memory loss or changes in demeanor, behaving as if they

have dementia when they have treatable depression. Addressing the patient’s depression can improve their cognitive functioning.

Identifying potentially treatable causes of cognitive decline can lead to earlier screening for underlying medical conditions that may be contributing to or causing that decline, said Lynn Schaefer of Nassau University Medical Center in East Meadow, New York, who is collaborating on a book with Farrer about reversible cognitive decline.

Schaefer said that by screening for these treatable conditions, physicians and other providers can determine if a patient would benefit from a more comprehensive assessment for dementia.

“This research can increase awareness of modifiable risk factors for dementia so that people can make informed decisions for their health to best reduce their odds of developing dementia,” Schaefer said. “It can bring people a sense of control and hope.”

Farrer’s suggestions to help prevent cognitive decline include engaging in wellness activities like avoiding ultra-processed foods, exercising regularly and visiting a primary care doctor.

“We have to have public health interventions, public health campaigns and increased knowledge about these things,” Farrer said. “At one point, no one cared about smoking, and then there was a public health intervention about the dangers of smoking and now far fewer people smoke. There are success stories of public health interventions; we just have to educate people.”

While dementia diagnoses are expected to increase due to a growing aging population, the rise may be less significant than initially projected as the number of misdiagnosed cases declines, he said.

“The time is now. I mean that from both a population health and a research standpoint,” Farrer said. “This is an area that is attracting significant research interest because we are on the brink of a major public health challenge. Now is the time to double down on our research efforts and prioritize public education to address these issues. We can reduce people’s risk for dementia.”

Farrer discusses cognitive assessment with students.

CLASS NOTES

1960s

Robert F. Wall ’69 was named conductor-musical director of the Clear Lake Symphony in Houston, Texas.

1970s

Don Shelton ’76 received the Crowder Cup from Phi Gamma Delta for outstanding faculty advising.

1980s

Scott Fehrenbacher ’80 was approved and inducted into the Canadian Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

Ken L. Post ’82 published the short story collection “Greyhound Cowboy and Other Stories” with Cornerstone Press.

Brian Von Bargen ’86 retired in July 2024 after working at the Hanford nuclear site in Washington for 37 years.

David LaMure Jr. ’88 received the 2024 Idaho Governor’s Award in the Arts for Excellence in the Arts.

1990s

Shelly Nelson ’90 obtained her Doctor of Psychology (Psy.D.) in school psychology from Capella University in 2024.

Audra Rojek ’96, ’99 was named to the American Council of Engineering Companies of Georgia’s list of 100 Most Influential Women in Georgia Engineering.

U of I congratulates these Vandals on their achievements.

Sara K. Sterner ’97 was presented the Cal Poly Humboldt Excellence in Teaching Award and promoted to associate professor.

Eric Swenson ’97, ’03 retired after 14 years as the Montana Office of Public Instruction’s business education specialist.

Ron L. Woodman ’97 joined the firm Hamburg, Rubin, Mullin, Maxwell & Lupin as partner in the Business Law department.

Christian Housel ’99 received the 2024 Idaho Governor’s Award in the Arts for Excellence in Arts Administration.

Jamie Michelle Waggoner ’99 published “Hades: Myth, Magic and Modern Devotion,” with Llewellyn Worldwide.

2000s

Jennifer Disotell ’02, ’04 was promoted to associate deputy director of Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service.

Jennifer Eccles ’02 was appointed vice president for advancement at Harvey Mudd College.

Jeffrey L. Beck ’03 received the 2023 Outstanding Research Achievement Award by the University of Wyoming Ag Experiment Station.

Johanna Blickenstaff ’08 was selected as vice president for strategic communications and marketing at Colorado College.

Jeremy Castillo ’08 was promoted to area supervisor at Ross in Honolulu, Hawaii.

Jeff Pittman ’08 co-founded boutique investor relations service FastPitch IR and signed their first client, Brookmount Gold, a gold exploration and production company.

2010s

Austin Folnagy ’10 was selected as president of the Oregon Community College Association and board member of Lane Community College.

Steve Hanna ’11 was promoted to director of product management at Micron.

Leila Emily (Weber) Hickman ’11 was granted tenure and promoted to associate professor of accounting at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo.

Jory Mikael Mickelson ’13 published their second book of poems, “All this Divide,” with Spuyten Duyvil Press.

SIGN UP FOR THE ONLINE MAGAZINE

Online subscriptions are more sustainable. They reduce the environmental impact of printing, transportation and disposal of paper products. Email advserv@ uidaho.edu to opt out of the print edition and get the online magazine delivered to your email inbox. Read it online at uidaho. edu/magazine.

IN MEMORIAM

Robert Gene Kerns ’44, Tacoma, WA, June 19, 2022

Betty Jean (Rice) Thompson ’45, Edmonds, WA, Oct. 17, 2024

Robert Swanson ’51, Pocatello, Sept. 3, 2024

Glen D. Morgan ’59, Lewiston, Sept. 14, 2024

Anne Kirkwood Trail ’60 , Spokane, WA, Jan. 19, 2025

Allen Strong ’64, Citrus Heights, CA, Nov. 4, 2023

Joelle F. (Michaelis) Jackson ’67, Asotin, WA, Nov. 23, 2024

Lawrence J. Kaschmitter ’69 , Montgomery, TX, Sept. 25, 2024

Randal F. Rice ’70 , Boise, Sept. 14, 2024

Harold Roy Seitz ’70, Eagle, Aug. 2, 2024

Pam Ann (Eakin) Pierce ’89, Bellevue, Nov. 18, 2024

Roland McIntyre Cooke ’91, Portland, OR, Sept. 6, 2024

U of I extends its condolences to the family and friends of our departed Vandals.

Stanley Daniel Shakenis ’92 , Waldport, OR, July 15, 2024

Martin William Hart ’97 , Las Vegas, NV, July 17, 2024

FACULTY/STAFF

D. Craig Lewis, Englewood, FL, Aug. 4, 2024

Monte Lee Steiger, Genesee, Oct. 13, 2024

Richard C. “Dick” Bull , Moscow, Jan. 5, 2025

MARRIAGES

Lilian Bodley ’20 to Samuel Myers ’20 February 2024

Philip “Flip” Kleffner ’55 , Moscow

Philip “Flip” Kleffner ’55 passed away Jan. 22, 2025, his 92nd birthday. Flip’s University of Idaho legacy began as a student leader and recordsetting athlete. He attended U of I at the same time as his future wife, Jo Ella (Hamilton) Kleffner ’56, also a dedicated Vandal. The couple were married for 69 years and had six children, 15 grandchildren and 14 great-grandchildren, many of whom are Vandals or future Vandals.

After graduation, Flip played baseball for the Philadelphia Phillies and served as an Ada County commissioner. The family moved to Moscow in 1980, and Flip became director of Alumni Relations for 17 years. He connected with thousands of Vandals and established alumni programs and events that continue today. He received multiple awards and recognition for his leadership, volunteerism and athleticism, including the university’s Idaho Treasure Award and induction into the North Idaho and U of I Athletics Halls of Fame.

provided by U of I Library Special Collections and Archives.

University of Idaho wishes these Vandal newlyweds lots of love and happiness.

Kylie Touchstone ’16 to Isaac Curtis ’16

September 2024

Emily Good ’20 to Cameron Weller ’20 September 2024

Freshman football player for University of Idaho Phillip ‘Flip’ Kleffner (#11), kicking, 1951.

Image

FUTURE VANDALS

1. Harper Katherine Becker, daughter of Shauni (Wemhoff) ’14 and Matt Becker ’16

2. Mateo Castillo, son of Brianna (Reasoner) Castillo ’18

3. Addison Lynn Doman, daughter of Katie ’12, ’22 and Chris Doman ’12, ’21

4. Cecelia Griffith, daughter of Cory Griffith ’10 and Mallory Cook Griffith ’12

5. Ransom Wilberforce Harned, son of Helena ’18, ’19 and Matthew Harned ’18, ’19

6. Hannah Athena Lemke, daughter of Stevie (Bergman) ’09 and Eric Lemke ’16

7. Ziggy Sorin Lie, son of Anna (Matteucci) ’18 and Stephen Lie ’18

8. Charlotte Elta Marks, daughter of Emily (Mulhall) Marks ’15

9. Hiranmayi Vignesh, daughter of Divya and Vignesh Jayaraman Muralidharan ’19

10. Celestia Avery Rand, daughter of Katie Celestia (Keller) Rand ’16

To be featured in Class Notes:

Submit your news at uidaho.edu/class-notes. You can also email your information, including your graduation year, to alumni@uidaho.edu, or via regular mail to Class Notes, Alumni Relations, 875 Perimeter Drive, MS 3232, Moscow, ID 83843-3232. Please limit your submission to fewer than 50 words.