18 minute read

CEO INSIGHTS – ROBERT LIMB OIL SPILL RESPONSE LTD

Wherever you go in the marine spill industry you meet people whose CVs seem to have Oil Spill Response Ltd (OSRL) on it somewhere. Their imprint on the industry is significant and its culture of quiet professionalism weaves its thread throughout the industry and in many areas they set the benchmark for the industry which all seek to follow.

With oil companies becoming energy companies and the necessary reduction in the use of hydrocarbons as the world pushes to net zero, I was keen to understand how OSRL are preparing for this. So, it was a pleasure to sit down, face to face, for a couple of hours with Robert Limb, its CEO, to discuss OSRL and his thoughts on the future of his business and the industry in general.

There is a myth that runs through the industry that OSRL is different to every other business in the industry in that they have a pot of gold, the oil companies, who pay for everything they do.

They do not. OSRL has 162 members divided into three categories of membership https://www.oilspillresponse. com/membership/our-members/ :

PARTICIPANT MEMBERS

– they are shareholders and are primarily companies involved in oil exploration and production. These members are generally oil companies or are working directly providing services for them; e.g. Trafigura. This is where the majority of OSRL income comes from.

ASSOCIATE MEMBERS

they pay a membership fee based on the level of risk eg a tariff per platform, per refinery, per vessel etc; A good example of membership here is: Associated British Ports Southampton or Prax Lindsay Terminal Limited.

NATIONAL AUTHORITY

MEMBERS – these are governmental organisations or agencies, like the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency, Irish Coast Guard, Rijkswaterstaat Zee En Delta, The Commonwealth of Australia - Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources. Members receive; support in risk management, staff and management training, OSRL incident management support and deployment of OSRL resource in support of exercises and, importantly, incidents wherever they occur in the world.

For members it is a fixed price contract with some variables related to deployment.

For OSRL it means they know their income but do not necessarily how much they are going to need to spend to support their members. Consequently, it is not a blank cheque!

However, they have more experience than any business in the industry in the number of unplanned events and incidents they are going to have to deal with in an average year!

This unusual ownership and membership structure is a legacy of OSRL’s formation.

A succession of oil tanker losses in the late 1960s and through the 1970s, caused considerable environmental harm and negative publicity for the oil companies who owned the vessels. It also demonstrated that governments in general had little defence against large spills.

These significant pollution incidents, occurring in relatively close succession, caused Europe to wake up to the risk it carried in allowing lightly regulated vessels to navigate their waters with inadequate maritime pollution incident plans as demonstrated by the response to each of these incidents. Government responded with tighter legislation. The oil companies, whose oil it was that spilled, were heavily fined and their reputations adversely affected. To mitigate further losses, they started to play a more active role in developing their own response organisations. In the UK, British Petroleum (BP) set up a large oil spill response base in Southampton and established, what is now Vikoma, a company manufacturing oil skimmers and retention booms on the Isle of Wight.

Subsequently the BP base was syndicated amongst various oil companies and in 1985 Oil Spill Response Ltd (OSRL) was formed to continue this pioneering work with funding support from four other international oil companies. This is the basis of the existing member/shareholder structure.

Consequently, in March 1989 when the SS Exxon Valdez struck Bligh Reef in Prince William Sound in Alaska spilling 10.8 million gallons of crude oil, OSRL staff were amongst the first response organisations to arrive at the incident from outside Alaska.

(For keen followers of oil spill response history you can read a more in depth article here in Spill Alert Issue 20 https:// issuu.com/ukeirespill/docs/spill_alert_20_ april/s/12064677)

Since then, OSRL has responded globally with trained staff, with its contracted and/ or directly owned dispersant platform. The training department, first established in 1991, shares knowledge and experience from subject matter experts and responders within the industry and OSRL has built a global network of 16 bases manned with centrally employed and local employees.

SS Torrey Canyon (25-36 million gallons crude oil) off the Isle of Scilly on 18 March 1967. SS Walfra, (14 million gallons) off Cape Aghulas, South Africa in February 1971. SS Amoco Cadiz on the Portsall Rocks, Brittany, Bay of Biscay (220,800 tons of crude oil) March 1978.

Enroute to a wireline logging job in Bu Hasa field in Abu Dhabi, UAE

ITS WORK IS NOW DIVIDED INTO THREE SPECIFIC AREAS OF ACTIVITY:

SURFACE RESPONSE

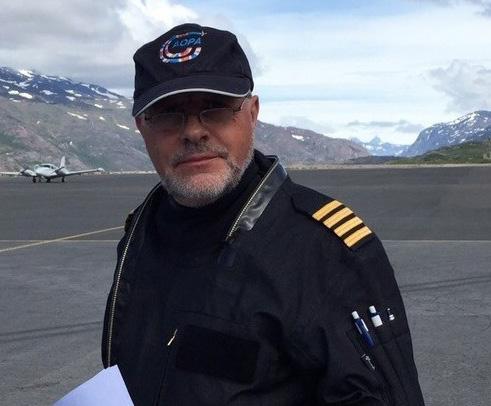

Flying the Atlantic – refuelling stopover in Narsarsuaq, Greenland on the way to Canada

This area responds to its members incidents when called upon to do so. It spends a lot of time preventing incidents by helping its clients manage risk and put in place procedures, equipment, and training so that they can contain it should one occur. This buys time for OSRL to deploy to manage the response and to deal with larger incidents should they occur. In addition, members have access to Technical Advisors with free in country assistance provided in the event of an incident.

OSRL conducts frequent exercises as part of member training. On the day I visited staff were debriefing and wrapping up an oil spill exercise in the English Channel that involved simulated dispersant application using their Boeing 727 Tersus system supported by the UKCS surveillance aircraft, Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS) and vessels.

It is also brought in to assist other organisations dealing with incidents. A good example of this is their involvement in the MV Xpress Pearl, where OSRL was initially mobilised by ITOPF in response to the loss of this vessel off the coast of Sri Lanka. Since then, it services have been retained by London P&I Club to assist them in the clean-up from the loss of the ships container load which includes a significant quantity of plastic nurdles. OSRL will likely provide further assistance when the wreck of the vessel is finally removed from the seabed by the salvors. Here competence, capability and speed of response rather than contractual relationship has won OSRL this valuable piece of work.

This division also manages the global dispersant stockpile which consists of 5000m3 of three types of dispersant stored in six locations around the globe. Another area of current focus is growing the wildlife emergency preparedness and

SUBSEA WELL INCIDENT SERVICES

In the unlikely event of a subsea well control incident, the Capping Stack is a temporary solution in order to stop an uncontrolled release of hydrocarbons to the environment while a relief well drilling operation with well kill is considered to be a permanent solution OSRL is the custodian of the equipment, storing and maintaining the capping stack systems in four international locations. 15KPSI capping stacks are located in Brazil and Norway, and 10KPSI capping stacks are located in Singapore (this cap is currently being upgrade to 15KPSI) and South Africa. The units can be configured for a variety of subsea interface requirements, and can be transported by land, sea or air. Maximum operating depths are 12,500ft/3800 m and they all include chemical injection points to mitigate the formation of hydrates. It is suitable for both exploration and production wells, and can safely contain, choke and cap up to 100,000 bpd flow in a controlled manner.

The subsea group are responsible for the management, maintenance and mobilisation of these capping stacks and other subsea systems. When an incident occurs OSRL are ready to assist the incident owner with the installation of these devices over a well. It is fair to say that OSRL are now world leaders in this technology and considerable experience is now vested in the company who have worked with its members to help design, manage the build and practice the deployment of these devices. The company continues to evolve the service providing additional equipment and capabilities to meet this rapidly evolving part of the Oil and Gas industry.

PREPAREDNESS SERVICES

This group provides a wide range of services and support including:

Preparedness training and support Exercises including Crisis and Incident management Equipment hire to support specific operations Technical support and development Consultancy and Secondments for both offshore and onshore risks Membership support and stakeholder engagement

OSRL is a busy global international operation that is often quite different to the calm one sees when one visits it waterside HQ base at Southampton. This base also provides administration and management for a complex and geographically diverse business.

In February 2013 Robert Limb, took over the helm of this global operation. Unusually his roots were in the international oil and gas business and not in the Royal or Merchant Navy like many of his predecessors. This marked a change that many noted at the time. However others suggested that a strong international commercial background was just what OSRL needed in changing times and in the years since, it seems they were right.

After graduating in Chemical Engineering from the University of Exeter on a scholarship from the Atomic Energy Authority, Robert found himself graduating to join an industry which the Conservative Government of Margaret Thatcher had just torpedoed by terminating all of its major projects.

Visit to the OSRL base in Bahrain.

So after just 6 months in the nuclear industry, he joined oil services company, Dresser Atlas in 1980 and spent a year as a field engineer working in the US and Canada learning the basics of the job. He was then deployed to the Middle East for just over five years, initially in Saudi Arabia. Field Engineers worked all over the country at exploration and production facilities. With a rotation of 60 days on and 16 days off they were rapidly exposed to full range of production activities. In the same role he then transferred to Abu Dhabi to a new start up business helping develop a footprint in an area with considerable business potential.

His next role was in the UK North Sea operations as a General Field Engineer based in Aberdeen, working in Norway, UK and Holland. After 8 years in field operations, he moved into management

as an Operations Manager initially in Aberdeen and then in Great Yarmouth to run a project for Conoco and subsequently the Southern North Sea activities. Once this was established, he moved back to Aberdeen to manage the UK operations.

In 1990 he was appointed Country Manager in Norway managing Scandinavian and Russia operations at a time of change following the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. In 1994 he moved to Singapore as Vice President, Asia Pacific to turnaround a loss-making division. This involved creating a new team, a strong ethos, giving people clear direction and allowing them the scope to do their job properly. The business expanded significantly opening new operations in Australia, Bangladesh, India and Vietnam.

After four years and following the acquisition of Western Atlas by Baker Hughes in 1998 Robert was asked to move to Houston as Vice President, Global Operations. In an oil price downturn and after 6 months in post, he persuaded the Board to split the business into Western and Eastern Hemisphere Operations. He and a colleague then each took responsibility for Global Operations and Sales in their respective hemispheres. By then the business employed 18000 people worldwide, with sales of $35 billion and some of this growth was coming from the move into integrated services where the oil companies were starting to contract out support services which might include drilling wells, managing infrastructure etc.

After 30 months in this role, Robert was approached by a friend and former colleague who worked in private equity and was asked to join Vetco, an oil and gas business that had been bought from ABB in mid-2004. Robert joined in 2006 and in 2007 the subsea business was sold to GE and subsequently in 2008 the Aibel engineering and construction business was sold to a Norwegian Group by which time he had become the President of the holding company.

Whilst not Roberts’ first introduction to private equity, his positive influence in funding business growth and restructure, was clearly demonstrated at Vetco Aibel. With new owners finding their feet, Robert was then invited by Credit Suisse to join Total Safety Inc. as Senior Vice President International Operations to improve global sales in the oil and gas sector. This was at the time of the Macondo incident in the Gulf of Mexico which accelerated their growth. A number of acquisitions were achieved including Z-Safety in Belgium, France, Germany and Netherlands. This was significant for Total Safety and gave them the direction they needed and once business had settled, Credit Suisse sold out in late 2011, which saw Robert take some After a few months back at home, in late 2012, he was then approached about and subsequently joined as CEO of Oil Spill Response Limited in Feb 2013. This was a familiar name to him as when at Vetco Aibel his VP HSEQ had previously served on the Board of EARL (East Asia Response Limited) which subsequently merged with OSRL and by coincidence met his predecessor over dinner through a mutual friend. After a smooth handover he took the reins and it was apparent that Robert would be helping to navigate OSRL through considerable organisational and operational change.

Following the Macondo blowout in the Gulf of Mexico in April 2010, the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP) created the “Global Industry Response Group (GIRG)”, to learn the lessons from the Macondo blowout and other similar events. Its work was divided into three core areas:

PREVENTION: to improve drilling safety and reduce likelihood of a well control incident

INTERVENTION: to decrease the time it takes to stop the flow from an uncontrolled well

RESPONSE: to deliver effective oil spill response preparedness and capability

Robert working as a field engineer in the Middle East

In May 2011, IOGP published GIRG’s comprehensive set of recommendations and proposed that three entities be created to manage and implement them.

The Wells Expert Committee (WEC):

to analyse well incident report data and share lessons learned, advocate harmonized risk-based standards, communicate good practice, provide permanent improvement in well control teams’ competence and behaviours and promote continued improvement in BOP reliability and efficiency.

The Subsea Well Response Project

(SWRP): a consortium of operators to investigate, design and deliver improved capping response with a range of equipment for shutting down wells; to design additional hardware The Oil Spill Response Joint Industry Project: to manage the

recommendations on oil spill response – develop new recommended practices, improve understanding of oil spill response tools and methodologies and to enhance coordination between key stakeholders internationally.

OSRL have been heavily involved in all three groups.

SWRP spawned OSRL’s Subsea Well Intervention Service (SWIS) which is in operation 24/7. Its members have invested $700M in Capex to create well Capping stacks, Containment and Offset Installation Equipment and to provide infrastructure to support a robust response capability to ensure that in the unlikely event of a Macondo type incident, industry will be better prepared to respond. To ensure that industry has a broader more integrated capability the Global Subsea Response Network (GSRN) has been set up by OSRL to provide a more comprehensive group of companies that can provide the full gambit of services that maybe required during a subsea well incident.

Naturally the Oil Spill Response Joint Industry Project has involved OSRL in considerable work with all of the major oil spill response organisation, this includes the Global Response Network which Robert chaired for three years. Large responses do not generally rely on one company responding to and dealing with the whole incident. To achieve a successful response requires a network of local and regionally based competent responders together with global resources to combine resources to quickly and efficiently deal with major incidents.

OSRL has also spent much time working closely with IPIECA as part of the joint industry project updating IPIECA excellent and comprehensive good practice guides.

Concurrent with this activity has been the introduction of a jet powered dispersant delivery system using 2 x Boeing 727 aircraft. Ambitious in concept it took time to deliver when the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) ruled that dispersants should be treated as flammable liquids. Being a pilot, Robert understood how the CAA have to ensure safety but found the delay to the project frustrating. The resolution came through a series of lengthy and costly engineering and safety studies which resulted in the certifying bodies recommending approval. This gives OSRL a tremendous aerial wide area dispersant capability with the previously contracted

Other air assets that OSRL provide are a PA31 Navajo based at Doncaster and two Cessna 337 in West Africa. All aircraft are equipped with dedicated surveillance sensors and communications systems for oil spill detection and response.

Many of OSRL Members now give strategic direction but require their operating companies to be in constant dialogue with OSRL so that prevention and preparedness is maintained. Consequently, a lot of time is spent supporting members in maintaining their ‘licences to operate’ which are always under scrutiny from Government’s and environmental organisations.

As oil companies lose experience, through retirement or the desire to outsource, OSRL is providing the ‘integrated services’ solution, familiar to Robert’s days at Baker Hughes. This generates stronger relationships between its members and OSRL. One of mutual dependency.

As the energy transition evolves OSRL will likely grow the integrated solutions business to ensure that oil spill risk resulting from operations continues to be well managed and assured. This will be particularly pertinent for the smaller oil companies taking over larger oil company assets as we are seeing occurring in more mature fields.

To assist in this, OSRL has been working closely with the UK Oil and Gas Association which was formed to support the activities of its members across many different aspects of the industry. One specific concept of current interested is the application of mutual aid to increase the available resources while ensuring resilience for any future incidents.

OSRL is also broadening its footprint of members with the breadth surprising from Government Agencies all over the world, to shipping companies, to river authorities and national coastguards including the UK Maritime and Coastguard Agency who also have access to the second Boeing 727 whenever it is available.

Roberts’ job is not only managing a £129M turnover business that is globally deployed with 280 employees but considerable stakeholder management. Its 162 members all have unique issues and whilst he is well supported, he is the CEO and in effect they buy a chunk of his time. Having weathered the COVID pandemic whilst maintain response capability worldwide, there are strategic issues that affect the business for the long term and a read of the excellent and informative company accounts publicly available at Companies House gives an insight to those I have not covered in this insight.

Robert’ prior commercial experience at senior level at ‘best in class’ oil and gas service companies brought commercial vigour and insight to OSRL at a time, post Macondo, that it needed. He has helped his senior team navigate the challenges that these reviews and new opportunities have presented. Subsea incident services is now the largest activity and home to unique capability and knowledge. The traditional response network is busy and being seen by many as best in class. OSRL is close to Government and its many agencies, particularly the MCA and this is as it should be. Consequently, the OSRL brand is highly

New Singapore base opening in Loyang Supply base Robert has a hand off approach to management. He sets the tone, gives strategic direction, reviews progress, engages with staff, encouraging openness in the organisation and listening to what people say. He has frequent townhall meetings where staff hear what is happening and is planned and seeks feedback from them. In a diverse and multicultural organisation this openness is welcome and has been one of the strengths that has helped OSRL manage through COVID and the changes in response this has necessitated.

Robert has been in post 8 years and whilst he did not mention retirement he no doubt feels that thoughts must turn to succession in such a stakeholder management business where change needs consultation.

Also his plane sits on the runway waiting to travel afar!

ROBERT LIMB CEO INSIGHTS

Diversity in all shapes is a strength and is powerful particularly as it avoids groupthink.

Encouraging diversity avoids organisations looking at the world through stereotypes.

Encourage people to say what they think and encourage inputs from all.

Think outside the box, there are so many opportunities in this changing world. Look locally as partners as well as nationally particularly as the energy mix changes but stay on top of technology.

Be careful how you treat people and always do so fairly. You get more back if you invest in them. The days of the dark satanic mills are long gone!

Educate and Train staff as broadly as you can afford to: e.g. leadership, people skills, the wider business, special to role training, as they are the company’s ambassadors. Yes, some may leave once better trained but they are also ambassadors for your business and bring with it goodwill and sometimes further opportunities. Seek and encourage co-operation across industry – when large incidents occur we all have to work together and the better we know each other the more seamless and trusting this will be.

Lessons from COVID:

People learn from people and need that interaction to gain knowledge, learn new skills and bond as a team.

Working remotely has generally been good and made possible by investment in technology that enables it. If this improves work/ life balance and mental resilience, then that is good as we now know productivity can be maintained.

It has possibly broken the ‘competitiveness at all costs’ that has existed in busines for many years and that is a positive.