Education

Michigan

The Magazine of T he Universi T y of Michigan M arsal fa M ily s chool of e d U ca T ion spring 2024

When I ask people to imagine possibilities for the future of education—even the very near future—I hear a fascinating variety of scenarios. Ranging from hopeful to grim, most people seem to have a sense that education from pre-Kindergarten through college is on the verge of evolving—or needs to be.

We have the privilege of shaping the future of education every day here at the Marsal Family School of Education. When we imagine the possibilities, we pay particular attention to centering the experiences of educators and learners, basing our ideas on rigorous research, and holding justice and equity as inviolable priorities. We let our imagination be bold, ambitious, and creative while simultaneously staying grounded in the scholarship for which we are so well respected.

One prediction I have heard is that artificial intelligence will obviate the need for teachers in classrooms. Though I vehemently disagree with that suggestion, it is reasonable to think that AI will continue to change education. We are committed to making that change be productive and healthy for both learners and educators and share a few examples with you in this edition of MichiganEducation

Dr. Anne Ruggles Gere brought her expertise in the teaching and learning of writing to U-M’s Generative Artificial Intelligence Advisory Committee, which was tasked with providing guidance to the university community on the use of generative AI tools. She delved into questions around the meaning of learning to write,

ethical implications and equity concerns of adopting AI tools, and responsible AI development and research on our campus. As many educators (including at our own university) have discovered, the emergence of AI forces instructors to think differently about assignments and, in doing so, has the potential to lead to more meaningful, dynamic instruction.

Dr. Gere shares some of her reflections on the process of producing the report that guides the university’s approach to AI.

Dr. Ying Xu explores the use of AI to make better learning tools for young children. She observed early in her research that children learn more from using media if someone engages them in conversation about what they viewed or played. Dr. Xu saw an opportunity to incorporate conversational AI into children’s television programming to maximize learning gains. Her collaborations with PBS KIDS have yielded exciting new AI-enhanced programming in which children can interact with characters from educational shows. Xu’s work is encouraging for another reason: her emphasis on participatory design has led her to begin a new project empowering teachers and parents to use AI to generate learning sources for children.

Dr. Jamaal Matthews and his team have created a virtual coaching space designed to support secondary mathematics teachers in creating inclusive learning environments. Years of research on minoritized student experiences in mathematics classrooms led to the creation of the Belonging-Centered Instruction framework that the team uses in their coaching. Dr. Matthews is also intentional about creating a sense of belonging for teachers in the coaching. This helps them move beyond enacting a set of practices to experiencing a shift in mindset so that they can best support their students’ development of identity and belonging and, ultimately, mathematics success.

In the world of human intelligence, at our P-20 partnership school in Detroit, The School at Marygrove,

Dr. Alaina Jackson and English teacher Bayan Founas launched the REACH Center—an inviting space in the high school that supports the school’s culture and climate through a culturally responsive restorative justice lens. Activities hosted by the center encourage students to bring their whole selves to school, develop critical consciousness, recognize and resist injustice, and connect with other people. The center is also home to a mentorship initiative in which high schoolers lead activities for students at the elementary school. The REACH Center encompasses many of the aspects that we, the partners, envisioned when creating a justice-centered multi-generational learning community in Detroit.

Several years ago, we launched our Teach Blue Initiative to strategically provide resources to recruit, prepare, retain, and recognize teachers. This year, we launched Teach Blue Fellows—a cohort of expert teachers who will be working in partnership with Marsal School faculty to define problems of practice in their work and to craft solutions that they implement in their schools. They will regularly document their work to share with beginning teachers, experienced peers, parents and community members, and education researchers. The work of veteran educators is complex and fascinating—but too often invisible. We are eager to collaborate with our fellows, communicate their findings, and elevate them as committed professionals over the next year.

Finally, we are proud to introduce the 2024 Marsal School Alumni Award recipients. We have designated three categories for recognition: the Emerging Leader Alumni Award presented to Dr. Andrew Kwok (BS ’07, PhD ’15); the Distinguished Alumni Award for Primary/Secondary Education presented to Patricia Dignan (EdD ’82); and the Distinguished Alumni Award for Postsecondary Education presented to Dr. Julian Vasquez Heilig (AB ’97, AM ’99). It is inspiring to read the stories of alumni making a difference in many different areas of education, and an honor to give out these awards.

We at the Marsal School are optimistic about the possibilities for the future of education. We see many reasons to be. We move forward in this crucial work knowing that whether the change we seek is technology-assisted, policy-defining, or paradigmshifting, we will hold ourselves accountable to learners, families, educators, and society, never losing sight of our commitment to justice and equity. ■

2 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Front cover photo: A U-M student leads local middle school students in a scavenger hunt around the UM-Ann Arbor campus during a two-day Digital Wellness Symposium. Photo by Jose Juarez, Michigan Photography

Could AI Help Children Get More Out of Educational Television Programs?

Dean Elizabeth Birr Moje

Editor

Danielle Dimcheff

Associate Editor & Lead Writer

Jeanne Hodesh

Contributing Writers

Rod Franchi

Alli Romano

Chris Tiffany

Design

Savitski Design, Ann Arbor

Hammond Design, Ann Arbor

We invite you to join the conversation by submitting ideas for future issues, letters to the editor, and class notes. marsal.umich.edu/magazine

Stay connected!

Web: marsal.umich.edu

Facebook: UMichEducation

X: UMichEducation

Instagram: UMichEducation

Office of Communications

610 East University Avenue

Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1259

soe.communications@umich.edu

Anoteoneditorialstyle:TheMarsalSchool strivestoestablishconsistencyacross materialsanddocuments,however,we acknowledgethatterminologyandstylingare personal.Wemake the intentional choice to honorthepreferencesofthesubjectswhoare interviewed for articles and we wish to accommodatethosepreferenceswherepossible.

assistant professor Ying Xu explores possibilities introduced by conversational ai

Virtual Coaching Helps Math Teachers Embrace Belonging-Centered Instruction

associate professor Jamaal Matthews studies how social and pedagogical supports can mitigate student alienation and dehumanization in mathematics and actively empower disenfranchised youth to realize their belongingness, agency, and skill

Teaching Writing in the Age of Generative AI

professor anne ruggles gere reflects on recommendations from the university’s generative artificial intelligence advisory committee

We Asked, AI Answered

can you tell the difference between our words and chatgpt’s?

Meet the 2023-24 Alumni Award Recipients

Emerging Leader and distinguished alumni awards recognize Marsal school alumni who exemplify the school’s mission in the work they do every day

A New Center at The School at Marygrove Reaches In, Out, Around, and Beyond to Advance Justice

clinical assistant professor alaina Jackson and English teacher Bayan Founas launch the rEach center

Teach Blue Fellows

Marsal school alumni make visible the work of expert educators while continuing to grow as lifelong learners of their own craft

Hail to the Conqu’ring Heroes

Marsal school students, faculty, alumni, and future alumni celebrate a championship happenings champions for Education

class notes

7 10 12 14 16 20 22 26 4 24 29 31

in Memory 3 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Above and top of previous page Storyteller, puppeteer, educator, and author Marilyn Price led students at The School at Marygrove in puppetmaking workshops. Price heads the nonprofit TriBraining, Inc., a foundation that provides training in the art of teaching and reaching all types of learners.

Above Campus Visit Day welcomed graduate and doctoral students to visit campus and learn more about the academic programs to which they had applied, and to (hopefully) say “Go Blue!”

Above and top of previous page Storyteller, puppeteer, educator, and author Marilyn Price led students at The School at Marygrove in puppetmaking workshops. Price heads the nonprofit TriBraining, Inc., a foundation that provides training in the art of teaching and reaching all types of learners.

Above Campus Visit Day welcomed graduate and doctoral students to visit campus and learn more about the academic programs to which they had applied, and to (hopefully) say “Go Blue!”

4 Michigan Education • s pring 2024

Above Dean Moje and Noah Moore, a resident teacher at The School at Marygrove, discussed the Michigan Education Teaching School model with U-M parents.

Above Local youth visited campus for the two-day Digital Wellness Symposium, a collaboration between the Marsal School, the School of Information, and the School of Social Work, to explore the impact tech devices and social media have on users. Following the symposium, the youth participants worked for two months with U-M students to research topics of digital wellness and share their findings with other youth and adults in their community.

Left Dr. Derek Briggs, a professor at University of Colorado, Boulder, delivered the 2024 Frank B. Womer Lecture. His talk, “An economist, a psychometrician, and a father of a special needs child walk into a school…” considered some best- and worstcase scenarios for the use of student assessments in conjunction with valueadded modeling as an approach meant to enhance educational opportunities and outcomes.

Above The 26th annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Children and Youth Program, serving preK-12 students, featured musical performances by local musicians and youth ensembles, interactive storytelling sessions, guided discussions, group projects, and a rap poetry workshop.

Above Students who were admitted into the Elementary and Secondary MAC programs visited campus to learn more about their respective programs.

Above The 26th annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Children and Youth Program, serving preK-12 students, featured musical performances by local musicians and youth ensembles, interactive storytelling sessions, guided discussions, group projects, and a rap poetry workshop.

Above Students who were admitted into the Elementary and Secondary MAC programs visited campus to learn more about their respective programs.

5 Michigan Education • s pring 2024

Above At the annual Hail Yeah! event, students wrote thank-you notes to alumni donors at U-M who have given gifts of $50 or less. The event highlights the importance of every single gift to our schools and colleges.

Professors and students from the Marsal School presented at Latinx Research Week, including Dr. Sharim Hannegan-Martinez, Dr. Deborah Rivas-Drake, Cassandra Arroyo, Valeria Ortiz-Villalobos, Alex Cabrera, Zahira Flores-Gana, Victoria Vezaldenos (at left), Anushree Bhatia, Viviana Velez-Negron, and Chloe Collon. The theme for this year’s conference was “Illuminating Familismo.”

right Eleven international scholars from the U.S. Department of State-sponsored International Visitor Leadership Program visited the Marsal School to learn about English Language Development in teacher education and English Language Learning resources on the U-M campus. Every scholar came from a different country, and participated in a 10-day tour of the U.S. to explore the theme of “American Language and Multicultural Diversity.” They met with U-M’s Dr. Susan Atkins and Dr. Judy Dyer.

right Students and their families gathered for the Secondary Teacher Education Induction Ceremony, which welcomes undergraduates who are studying to be secondary teachers and preparing to start their professional courses.

6 Michigan Educ ation • s pring 2024

Could A i Help Children g e t More Out of Educational Television programs?

assistant professor Ying Xu explores possibilities introduced by conversational ai

According to a national survey, Assistant Professor of Educational Studies Ying Xu notes that children in the U.S. spend an average of two hours per day watching television or online videos.

“There are a lot of debates and worries about children using digital technologies. In my projects, we’re not trying to increase the time children spend with technology. But what we could do is think about the time children are already using technology. How could we make the technology a better learning tool for kids, and maximize their learning during the time that they are already spending, for example, watching TV or playing video games?”

Xu, who has a background in linguistics, has long been interested in the ways in which our acquisition of language can be supported by technology. While interning at a digital publishing company that developed educational media to teach kids English, Xu was responsible for observing how children interacted with the company’s products. She took note of how much the children enjoyed the media and what they learned from their interactions. Based on what she gathered, Xu drafted recommendations for the product design department to improve the products. Soon, however, she saw the limitations of exploring the potential posed by technology in the corporate sector. To further explore this line of inquiry, she went on to pursue her doctorate in Language, Literacy, and Technology at the University of California, Irvine.

In her early research observing children’s use of a range of different media—like televisions, e-books, and touchscreen games—Xu determined that children benefit more from media use if they are prompted by an engaging individual who asks them questions and listens to them reply, or when the content is specifically designed to encourage them to talk.

“When devices like Amazon, Alexa, and Google Home were introduced to households, I immediately recognized the potential for the technology to simulate the way a teacher or parent would engage young learners in educational dialogue,” Xu says. She conducted preliminary studies which showed that children

could learn from their conversations with AI. “At that time, not a lot of people were aware of this potential for conversational AI. I thought it would be beneficial to find a partner who has already produced high-quality media and see how we could use AI to enhance how much children could learn.”

7 Michigan Education • spring 2024

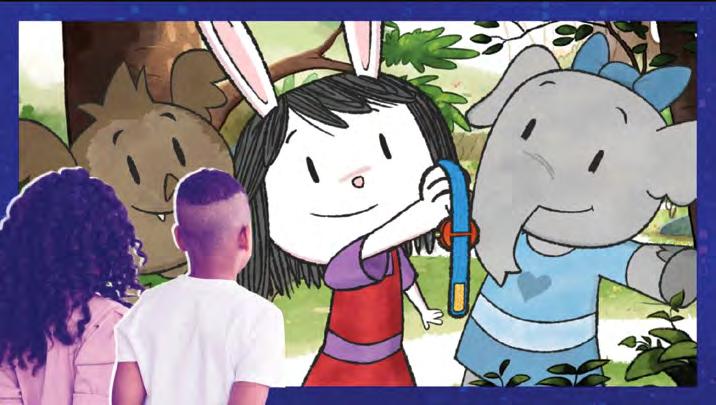

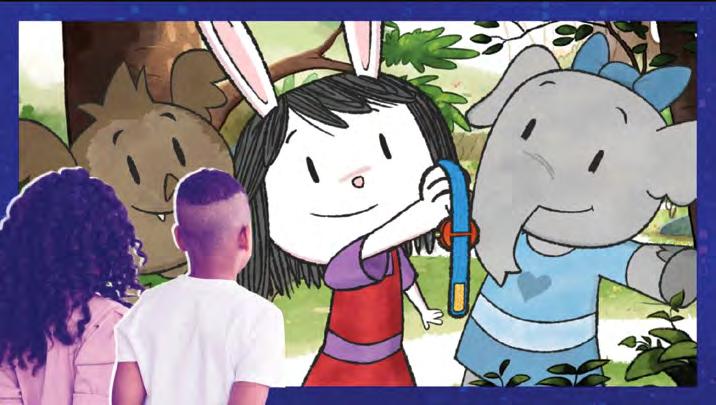

Since 2018, Xu has collaborated with PBS KIDS and a team of colleagues to study the impact of AI-enhanced children’s television programs. Building on shows like Dora the Explorer and Mickey Mouse Club House, which have pauses in their scripts for children to respond to the characters, Xu wanted to see how they could use AI to make the characters interact with the children based on their answers to questions. Because many children watch TV shows on mobile devices now, Xu saw an opportunity to incorporate conversational AI into the program by utilizing a device’s microphone.

The children who viewed the fully interactive episode performed the best on the assessment questions, followed by the group who watched the semi-interactive version and then those who watched the original noninteractive episode.

Xu and her team created an interactive version of the PBS KIDS program Elinor Wonders Why, a science show for preschool-aged children. In their version, a curious bunny named Elinor listens to the responses young viewers give when she poses questions. She can reply with feedback specific to a child’s answers, or provide prompts if the viewer needs assistance.

“We know that children admire their favorite TV characters and may even form emotional attachments to them,” says Xu. “What if the character could actually listen to them and talk back to them? It means a lot to kids.”

research projects on interactive Ai

In a study Xu and her colleagues presented at the 2023 American Educational Research Association (AERA) annual meeting, they divided 240 children into three groups. One group watched the fully interactive, AIenhanced version of ElinorWondersWhy, the second watched the original non-interactive broadcast of the episode, and the third watched a semi-interactive version similar to a show like Dora the Explorer, in which the character poses questions, pauses as if listening, and then provides generic responses.

After watching the show, the researchers tested how much children had learned using an assessment developed by the team. The children who viewed the fully interactive episode performed the best on the assessment questions, followed by the group who watched the semi-interactive version and then those who watched the original noninteractive episode. Additionally, Xu’s team looked at the children’s responses to the questions Elinor had posed during the episode. The participants who watched the semiinteractive version lost interest in responding to Elinor’s questions when they realized she could not comprehend their answers.

In February 2024, PBS KIDS launched a new program, Lyla in the Loop to engage a broader range of children—this time ages

4–8—in STEM education. Over the last year and a half, Xu’s team has been working closely with the show’s creators and PBS KIDS to see how they could adapt it to incorporate AI to facilitate student’s interactions.

“There are a lot of design considerations that you need to think about: how to ask the best questions, how to facilitate students’ engagement if they are a little more hesitant to share their thoughts. And if we identify those who have misconceptions about a question, how do we scaffold those students?” says Xu.

Once all of the design aspects were taken into consideration, Xu and her team began to test the content with kids. In the first phase of testing, they just wanted to see if their design worked or not.

Ying Xu with Elmo during a visit to Sesame Workshop

Ying Xu with Elmo during a visit to Sesame Workshop

8 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Elinor speaks directly with a child in the interactive version of the show.

“We are interested in code switching—allowing the conversational Ai to understand the mixed use of multiple languages.” Ying Xu

“It’s what we call a participatory design phase. We sit down with a group of five to 10 kids and show them our interactive videos. We just observe how they interact with the conversational AI.” They also ask the children questions: What do you like about this process? Was it confusing? Do you have any ideas that could help us make it even better? Xu’s team took the kids’ responses into consideration to continue improving the conversational video.

In the second phase of testing, the team will run a randomized trial with a larger number of children—200–300—dividing them to watch the same content in different formats as they did when testing the efficacy of AI enhancement to ElinorWondersWhy. As with the first program, the topic of LylaintheLoop is STEM-related, with episodes that teach computational thinking. However, this new program will be offered in both Spanish and English.

Benefits of Ai-enhanced programming

The majority of the children Xu and her team work with are bilingual learners who do not speak English at home. They have found that these students benefit from the AI-enhanced programming to a greater extent because the scaffolding it provides helps them better comprehend the scientific concepts being introduced in the shows.

“We have learned that kids feel comfortable interacting with the AI that is more consistent with their language background,” says Xu. So do their parents. The finding inspired Xu’s team to see if they could make conversational AI more inclusive. “We are interested in code switching—allowing the conversational AI to understand the mixed use of multiple languages. Multilingual children often switch between different languages based on the situations and the context and who they’re talking with.”

In collaboration with the Joan Ganz Cooney Center at Sesame Workshop, Xu is exploring how a Spanish-English bilingual AI could support parent-child interactions during storybook readings in Latine families. From interviews with both the children and the parents who tried the bilingual AI, she found that participants appreciated the flexibility to engage in both languages. In fact, it inspired parents to think about

the overall importance of cultivating their child’s bilingual and bicultural identity.

Xu is also keen to see if, by facilitating the meaningful interactions between children and their favorite TV characters, they might come to see the characters as role models for learning STEM. In LylaintheLoop, the main character is an African American girl. “We’re very curious to see if having a dialogue with Lyla will become a factor in encouraging girls and those from minoritized backgrounds to become scientists.”

Furthermore, Xu hopes to determine whether having a dialogue with AI could

project (also funded by the NSF) to empower non-technical experts who know children best, like teachers and parents, to use AI to generate learning sources for children.

“We are designing AI that allows teachers to ‘collaborate’ with it to embed meaningful learning questions into educational videos,” she says. “This approach allows teachers to tailor AI-generated questions to fit their specific instructional needs, rather than relying solely on predeveloped content.” Xu’s team is conducting interviews with teachers in different states and has found that educators are generally excited about the potential of

help kids not only learn about the concepts introduced in the show, but also transfer that knowledge to different scenarios. “This is one thing that we think is very important,” she says, “because learning is not just memorizing a concept, but also actually being able to apply it in everyday problem solving.”

Xu and her team have received two National Science Foundation (NSF) grants to support their research with PBS KIDS. Much of her previous research had an emphasis on participatory design, using feedback from children, parents, and teachers to inform different iterations of the media she and her colleagues develop. However, with the advances in generative AI, Xu is interested in extending this user engagement beyond the design phase, allowing kids and educational stakeholders to continuously customize and influence the media content as they use it. She is now working on a new

AI to improve their instruction, especially when they have adequate control over the content and its application.

When Xu is met with resistance to researching the potential uses of AI in early and elementary education, she understands parents’ and teachers’ skepticism. But she is also ready with an answer.

“As researchers, it is actually our responsibility to understand the implications of AI on child development before the technologies reach children at a massive scale,” says Xu. “We need to stay ahead of the curve and think about what kind of impact this technology could have on children’s cognitive development, social emotional development, and physical health. It is our job to understand this better so that we can provide guidance to facilitate the future development of the technology in a way that is safe and inclusive for children.” ■

Pipeline Studios, © SHOE Ink / PBS KIDS / Shutterstock / Prostock-studio, TechSolution

9 Michigan Education • spring 2024

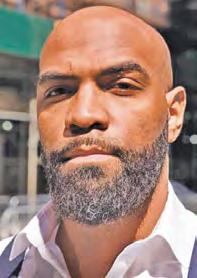

Virtual Coaching Helps Math Teachers Embrace Belonging-Centered instruction

associate professor Jamaal Matthews studies how social and pedagogical supports can mitigate student alienation and dehumanization in mathematics and actively empower disenfranchised youth to realize their belongingness, agency, and skill

Dr. Jamaal Matthews’ latest work began with a sudden flash of insight during a 2019 conference. “I went to a convening at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation around sense of belonging,” Matthews explains. “They had a pamphlet of all the people who were attending, where each of us defined belonging in their own words. It was interesting seeing everyone’s different conceptions and notions of belonging.” The pamphlet made Matthews think of how it might connect to his work with Newark Public Schools—a project that followed students over the course of five years from their middle school math classrooms to their high school math classrooms.

“We had almost 300 hours of interview data from Black and Brown students talking about their experiences in their math classrooms,” Matthews says, “their racial identity, their interactions with their teachers and peers—all these things that give us a sense of how they defined belonging. So here I am with these research experts who are explaining how they define belonging for themselves. But how do Black and Brown kids who are trying to navigate their sense of belonging in math classrooms, how do they define it?”

“We had five years’ worth of all this interview data,” Matthews recalls. “It took a year and a half, maybe two years, to go through it all, but that’s how we created Belonging-Centered Instruction—BCI—these different dimensions of how students think about and conceive of belonging.”

BCI aims to support secondary mathematics teachers in developing classroom practices that encourage equity for racially marginalized students and examine the psychological and sociocultural mechanisms that facilitate teacher growth in culturally conscious mathematics instruction. BCI coaches work with teachers to help them provide social and pedagogical supports that mitigate student alienation and dehumanization in mathematics and actively empower disenfranchised youth to realize their belongingness, agency, and skill.

Matthews, an Associate Professor in Educational Studies and the Combined Program in Education and Psychology at the Marsal Family School of Education, is the recipient of multiple national awards—including outstanding dissertation awards from the American Psychological Association (APA) and ProQuest, the APA Early Career Educational Psychology Research Award, the National Academy of Education/Spencer Postdoctoral Fellowship, and the Best Article Award from Educational Psychologist in 2018 for his article “Black and Belong-

ing at School.” His research interests are grounded in his experiences as a middle school mathematics teacher in the Bronx.

Using data from the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR), an international consortium of academic institutions and research organizations housed at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research, Matthews and his team were able to put parameters around different dimensions of belonging and begin the process of figuring out how teachers can enact these different dimensions. “We coded maybe 500 ICPSR videos using this BCI framework,” Matthews explains, “and found that the different dimensions predict a variety of different outcomes for students. Achievement, multiple measures of engagement, persistence, effort—all of these things.”

“We’re trying to create a belonging space for teachers, helping them see their students with a different view and provide personalized, tailored feedback and support.” Jamaal Matthews

Matthews says that, given the ways Black and Latine students face social threat and stigma in mathematics education, they need culturally competent teachers to help them confront these challenges in ways that engender belonging, healthy identity development, and mathematics success.

Matthews and his team used the data they collected to create a virtual coaching/pedagogical/learning space designed to support teachers and build their capacity to execute on various dimensions of belonging. This virtual intervention against traditional negative outcomes of current math classroom practices provides teachers with observational analysis of their instruction and continuous improvement coaching for cultivating Belonging-Centered Instruction.

“It’s not just didactic instruction,” he explains, “I think part of the danger—and there are a lot of dangers with a framework like this and how people take it up and use it—is that it just becomes a checklist of do x, y, and z. It can become about doing behaviors and not recognizing that there’s a mindset shift and a belief system shift needed to fully maximize the enactment of these different dimensions.”

“We really are trying to get to a deeper level of belief systems on ways of thinking and being,” Matthews continues. “Ultimately, those will infiltrate practices that teachers do in the classroom. We’re trying to create a belonging space for teachers, helping them see their students with a

10 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Jamaal Matthews

different view and provide personalized, tailored feedback and support. In our coaching work, we try to create this atmosphere of belonging that the teachers can experience. It’s almost a meta demonstration of what they ultimately could be doing in their class.”

“The combination of watching videos of themselves teaching, exploring the BCI framework in Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) and reflecting on their practice in one-on-one coaching sessions has resulted in major shifts in their teaching pedagogies and approaches,” says Rebecca Guarino, a coach analyst for the project who works as a master teacher in mathematics in New York City. “The teachers we are coaching in the BCI framework have been really responding well to our program. We have seen teachers change their practice from lecturing to using student-centered protocols, integrating nonviolent communication strategies with students they are struggling to connect with, discussing the implications of systematic racism on their school culture and classroom practices, and sharing new strategies amongst our PLC community.”

With support from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the project is currently being piloted with a total of 15 teachers in two large urban districts in the Northeast that serve predominantly Black and Brown students. Matthews expects to double that number next year and double it again the following year, with an overall goal of working with 120 teachers over the course of the three-year project. Each teacher will work with BCI coaches for a minimum of three separate eight-week cycles—essentially a full school year. Currently, coaches work together in pairs with a “pod” of four teachers. Matthews’ team is working on ways to streamline systems so that coaches have more capacity to take on more teachers.

“Teaching is an extremely stressful, demanding job from many different angles,” Matthews says, “from students, from administrators, from parents, from the districts. Many teachers do not get the respect and sense of value that they should for the work that they’re doing. It’s hard for us to say ‘create this belonging space for your students’ when you’re struggling with your own sense of belonging as a professional. So we try to make the PLC a space where, once a week for 90 minutes, they can feel that, along with our coaches and teachers who are working on similar problems of practice.”

Thinking beyond the initial three-year pilot program, Matthews is cautious about expanding the project to other domain areas. “At a high level, yes,” he says. “I think the ideas do transfer, but getting into some of those practices and finer grained principles, I think there’s just going to have to be another grounded study that would have to take place, similar to the one that we did in secondary math. If we suggest transferring these ideas into a biology class or a physics class without having done the same ground work—I’m a little wary of doing that.”

“When the work of teaching centers belonging, students know, understand, and feel their identities are held sacred in the mathematics classroom. And that, by any measure, is a success.”

Charles

Phillips

Matthews also has concerns about the inevitable questions around how Generative AI might be utilized in this work, but has been keeping an open mind. “There are some AI folks out there who are doing work around equity as it relates to group conversational patterns,” he says. “There are ways in which dominant voices within the group make space for secondary voices—folks who don’t speak up as much. Right now we’re collecting all of this data that we could potentially learn from, but we don’t have the people power to code all of that. So it seems like the perfect problem for GenAI, to leverage that technology. That could help us refine our coaching processes and contribute to academic knowledge in teacher education.”

For now, however, the pilot project is still gaining steam—and is already beginning to show some encouraging results. Charles “Chaz” Phillips, a PhD student and Rackham Merit Fellow in Mathematics Education at the Marsal School who also serves as a coach analyst for the project, says, “I have a teacher that loves how the subdimensions have helped develop his teaching craft and strengthen relationships with his students. When the work of teaching centers belonging, students know, understand, and feel their identities are held sacred in the mathematics classroom. And that, by any measure, is a success.” ■

11 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Teaching Writing in the Age of generative Artificial intelligence anne ruggles gere

reflects on recommendations from the university’s generative artificial intelligence advisory committee

Over the course of her 30-plus years as a professor at the University of Michigan, Anne Ruggles Gere (PhD ’74) has borne witness to seismic changes in the way we write and teach writing. A professor of English and Education since 1987, she has served as chair or co-chair of the Marsal Family School of Education’s Joint Program in English and Education since 1988. From 2008 to 2019, she directed the Sweetland Center for Writing, a comprehensive writing center that exists to support student writing at all levels and in all forms and modes.

Gere remembers producing her dissertation on a typewriter. And she remembers the way the introduction of computers changed student writing. Before computers, she recalls, the most common mistake was misspelled words; with the advent of computers—and their spell check programs—the most common mistake became misused words. (Think ‘their’ instead of ‘there,’ ‘to’ instead of ‘too,’ or, to Gere’s delight—when referring to one’s demons—‘exercise’ instead of ‘exorcise.’) She was teaching at the dawn of the internet, and this year—in her final two terms before retirement—she found herself teaching in the age of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI).

In early 2023, as the emergence of GenAI programs like ChatGPT began to spark concern throughout institutions of higher education, Provost Laurie McCauley and Vice President for Information Technology and Chief Information Officer Ravi Pendse announced the formation of an advisory committee to recommend how the university should approach the evaluation, use, and development of emergent GenAI tools and services. Gere was asked to join. She knew colleagues who had declined, but she felt compelled to add her voice.

Iagreed to join the committee because writing studies is my field,” says Gere.

“And frankly because when I looked at the composition of who was already on the committee, nearly all male, nearly all from the sciences and engineering and medicine, I thought they needed somebody from the humanities, somebody who’s a teacher—all the things that I value that I wasn’t sure would be heard if my voice wasn’t there.”

Consisting of faculty, staff, and students from across the university, the Generative Artificial Intelligence Advisory (GAIA) Committee worked to create resources for the university community to handle the impact of GenAI programs, provide training and support infra-

structure for the use of GenAI tools, and study its longer-term implications for work and life at U-M. The body was tasked with devising a report that would set the foundation for the university’s path forward with GenAI in the short, middle, and longer terms.

“I think it’s fair to say that many of the people on the committee were very positive and excited about the potential for generative AI,” says Gere, whose own bias tilted in the other direction. “What I pushed for was more about what effect this is going to have on the University of Michigan’s teaching mission and on the people who are doing the work of teaching. My major contribution—in addition to talking a lot about writing with people who don’t think about it as much— was to design and carry out a survey.”

The survey, which was shared with faculty, students, and staff across the university in early June 2023, was designed to help the GAIA Committee make recommendations that would allow the university to maximize GenAI’s potential benefits.

With over 6,000 responses, results from the survey confirmed Gere’s sense that there are as many possible downsides as upsides from the adoption of GenAI. The results showed that of the three groups surveyed—staff,

“ 12 Michigan Education • spring 2024

faculty, and students—staff had the most negative feelings about GenAI. This group was worried about job security. Faculty were most concerned about academic integrity.

“Undergraduates were most enthusiastic, which was not surprising because I think they are much more comfortable with technology than probably any other group on campus,” says Gere. “What I found interesting was that they also had a strong negative response because they feared they would be falsely accused of cheating. That sort of weighed against their enthusiasm.”

As McCauley and Pendse state in an introduction to the report, “GenAI is shifting paradigms in higher education, business, the arts, and every aspect of our society. This report represents an important first step in U-M serving as a global leader in fostering the responsible, ethical, and equitable use of GenAI in our community and beyond.” The report is meant to be used as a catalyst for conversation as GenAI technology—and the university’s adoption of it—continues to evolve. The report spans topics including an explanation of the science and capabilities of GenAI; guidance for instructors; the impact and management of GenAI on teaching, learning, and research; ethics and equity; training resources; and ongoing academic research on GenAI. Additionally, the report anticipates the impact GenAI will have on campus life, offers examples to instructors for how to create dynamic assignments, and explores the positive and negative effects GenAI may have on the university community.

Of the many recommendations and guidelines outlined in the report, Gere was most pleased by two decisions the committee made. First, that the university should create its own version of ChatGPT—U-M GPT. Gere frames the recommendation as an equity issue—whereas anyone can access the free version of ChatGPT online, not all students would be able to afford subscribing to the latest and best version of the tool. That would create an imbalance of access among the student body. U-M GPT would also address the security implications posed by the GenAI tool that is widely available. “It prevents the work of our students from being used to train and advance the larger GPT,” says Gere.

The other decision she commends is choosing not to rely on detection tools to check whether or not student work has been created by GenAI.

“The detection game becomes an arms race very quickly. Nobody wins,” says Gere. “Perhaps more importantly, it changes the relationship between students and teachers. I do not see myself as a police officer in the classroom, and I don’t ever want that role. I see myself as an enabler who’s going to try to help people develop into the best writers they can be. And it seems to me that playing police is exactly the wrong way to do that.”

With over 6,000 responses, results from the survey confirmed gere’s sense that there are as many possible downsides as upsides from the adoption of genAi.

When Gere addressed the Marsal School community at Fall Convocation in September, she shared examples from her own teaching practice for how to navigate the use of GenAI tools with students. One of the most common assignments given to K-12 and college students is to write an essay about a given topic.

“That is truly a terrible assignment,” said Gere, “and it’s perfect for GenAI. ChatGPT can write essays. They’re not very good essays, but it can write essays. As teachers, if we care about the quality of student writing, I think we have to think long and hard about the quality of our assignments.” She suggested including features in assignments that have students address the audience to whom they are writing and the purpose for which they are writing. “It seems sort of simple, but let me tell you, assignments don’t often include those features, and that can make a huge difference.” Another approach Gere suggested was requiring the submission of iterative drafts throughout the semester rather than turning in one big paper at the end of the term. “If we are asking students to write multiple drafts, and providing feedback as those drafts are being produced, they can’t win with AI. Rather than simply assigning something and then waiting for students to turn it

in, it seems to me part of teaching is intervening in that process in these ways.”

In the seminar Gere taught during the fall term, she had students use U-M GPT to generate ideas to get started on one assignment. For another assignment, she asked them to use U-M GPT to create a draft of a paper, and then use it as an object for revision. By articulating the weaknesses in the GPT-generated draft, the students were able to identify the elements that would make it a stronger piece of writing—adding specific details to make it less general, developing a clear and distinct voice—and in turn learn to incorporate those same tactics in their own work. Finally, she had students ask the AI to write a bibliography on any given topic. “Of course, half of what the tool generated were hallucinations.

“I’m trying to help students learn about what AI is,” continues Gere, “because I don’t think that just shutting the door is the answer. But figuring out what it can do and where it really doesn’t make sense to use the tool is useful.”

Gere says that more organizations—including the Modern Language Association and the National Council of Teachers of English—are stepping forward with findings from task forces convened to advise how to navigate the new moment we find ourselves in. In January 2024, Karthik Duraisamy, who served as chair of the U-M GAIA Committee, spoke about the university’s report at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland where members of the business world were as concerned about how GenAI will shift areas of industry as members of the U-M community have been about its impact on higher education.

Although she’s impressed that the committee’s work is being shared with a broad audience, and glad that the recommendations of professional organizations are providing resources to teachers, as someone who has seen technologies come and go throughout her long tenure in the classroom, Gere remains somewhat hesitant about the dramatic effect some claim GenAI will have on teaching.

“If you care at all about student learning,” she says, “I don’t see how you could persuade yourself that just having students give directions to a machine is learning how to write. There’s so much more to learning than just the input of content.” ■

13 Michigan Education • spring 2024

We Asked, Ai Answered can you tell the difference between our words and chatgpt ’s?

We asked ChatgpT to create some content for the Marsal School. Can you tell which answers were written by faculty and staff at the school and which were generated by AI?

1. What careers will a Master of Arts in Educational Studies at the Marsal Family School of Education prepare graduates for?

A: A master’s in Educational Studies prepares graduates for a dynamic career in education beyond traditional teaching roles. This program equips grads with a deep understanding of educational theories, policies, and practices, enabling you to analyze and address complex issues within educational systems. Students gain expertise in curriculum development, educational technology, inclusive teaching strategies, and leadership, making them well-suited for roles in educational administration, policy analysis, curriculum design, and educational consultancy.

Additionally, this degree fosters critical thinking, research skills, and a global perspective on education, allowing students to contribute to educational reform and innovation. Graduates often pursue careers in nonprofits, governmental agencies, educational technology firms, and higher education institutions, where they work to enhance educational outcomes and equity. The Marsal Family

School of Education thus prepares students to become a transformative leader in education, capable of making significant contributions to the field.

B: A master’s in Educational Studies prepares graduates for diverse roles in nonprofit organizations, government agencies, and industry. Read on to learn how each concentration area focuses on specific competencies and prepares graduates for various career paths.

The Design and Technologies for Learning Across Culture and Contexts concentration prepares professionals for designing a wide range of learning environments in formal and informal settings. Graduates have the expertise to examine theory, research, and design with a critical eye toward improving outcomes for learners. Graduates have found great success as learning experience designers, doctoral fellows, and in many educational roles working in both for-profit and nonprofit organizations.

The Educational Equity, Justice, and Social Transformation concentration provides students with a foundation in the social, cultural, economic, historical, and political foundations of schooling. Graduates are prepared to critically examine educational contexts, practices, and policies rooted in

injustice, whiteness, and oppression in educational systems to unpack how these systems have fostered social inequity and work toward justicedriven change. Graduates have taken positions in educational, government, and nonprofit organizations as education equity specialists.

The Research for Educational Improvement concentration prepares students for positions in research organizations, centers, or projects engaged in evaluation research, or as research support staff in formal and informal educational settings where education professionals are engaged in improving practice and policy. Students have opportunities to learn the practices of research design, data collection, and data analysis, how to conduct literature reviews, how to conduct consultation with education professionals, and how to write reports.

If a student’s career objective is integrating business acumen with educational expertise to effect meaningful improvements in our education system, the Marsal Family School of Education and the Stephen M. Ross School of Business offer a dual degree program.

2.

or

3. Write a welcome from the dean of the Marsal Family School of Education to the graduates of the class of 2024.

A: On behalf of the faculty and staff, it is my honor to congratulate you on the completion of your degree at the University of Michigan. Your family, friends, and colleagues join us in celebrating this wonderful achievement and wishing you success in the next phase of your career.

True

False: AI wrote the dean’s cover letter in this issue of Michigan Education magazine?

Michigan Education The Magazine of T he Universi T y of Michigan M arsal fa M ily chool of e d ca T ion spring 2024

14 Michigan Education • spring 2024

I hope that you are as proud of your accomplishments as we are. Through hard work and commitment, you have earned your degree from one of the finest universities in the world. The University of Michigan, as a public institution, exemplifies society’s commitment to education for the common good, making your degree even more powerful.

Thank you for your many contributions to our community during your time at the Marsal School. Just as you have shaped our school with the ideas, perspectives, and skills you brought with you into this community, you now take all that you are and all you have become at the University of Michigan out into other communities around the world.

How will you transform the world using your education? How will you transform the world through education? We use a phrase to describe the contributions of our alumni: infinite impact. This means that in every obstacle you face head on, and in every opportunity you create, you have limitless potential. Each of you will contribute infinitely to making the world a better place.

May you always remember that you are not alone in your endeavors. Today, we welcome you into an alumni family of over 42,000 graduates. Generations of teachers, scholars, policymakers, and leaders in both corporate and nonprofit enterprise have shaped education in this country and around the world. You will follow in their footsteps even as you blaze new trails. Go Blue!

B: As the Dean of the Marsal Family School of Education, it fills me with immense pride and joy to address you on this momentous occasion. Today, we gather not just to celebrate your academic achievements, but also to honor the journey you have undertaken to reach this significant milestone in your lives.

Throughout your time at the Marsal Family School of Education, you have shown an unwavering commitment to excellence, a deep passion for learning, and an inspiring dedication to making a difference in the world through education. You have not only mastered the theoretical aspects of your field but have also demonstrated remarkable ability to apply this knowledge in practical settings, positively impacting the lives of those around you.

As you stand on the brink of a new chapter, I want to remind you of the vital role you will play in shaping the future. The knowledge and skills you have acquired here are tools that empower you to contribute to a better world, one where education is accessible, inclusive, and transformative. Your commitment to fostering learning, encouraging critical thinking, and nurturing the potential in every student will ignite change and drive progress in our societies.

The path ahead will present challenges, but it is also ripe with opportunities to innovate, inspire, and lead. Remember, the true mark of an educator is not just in the knowledge they impart, but in their ability to spark curiosity, build resilience, and instill a lifelong love of learning in their students. I have every confidence that each of you will rise to this challenge with the same determination, creativity, and compassion that you have shown during your time with us.

As you move forward, know that you will always be a cherished member of the Marsal Family School of Education community. We are excited to see the impact you will make and look forward to celebrating your future achievements.

Congratulations, graduates of the class of 2024. The world is waiting for your contributions, and I have no doubt that you will leave an indelible mark on the field of education.

A:

B:

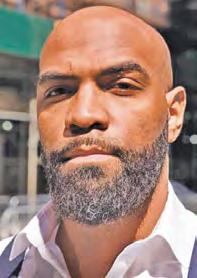

4. Show me the dean of the Marsal Family School of Education.

4. Show me the dean of the Marsal Family School of Education.

ANSWER KEY 1.

2.

3.

4.

15 Michigan Education • spring 2024

B is written by the Marsal School.

False. Dean Moje did indeed write the cover letter.

A is written by Dean Moje.

A is a picture of Dean Moje. Strangely, the AI added some of its own elements, stating “Here’s the image of the dean of the Marsal Family

School of Education, set in a futuristic office on Mars, showcasing a blend of innovation, diversity, and leadership.”

Meet the 2023-24

Alumni Award Recipients

Each year, the Office of Development and Alumni Relations recognizes alumni who exemplify the school’s mission in the work they do every day with the Emerging Leader Award and the Distinguished Alumni Award.

Emerging Leader Alumni Award

Andrew Kwo K

On his first day as a new teacher in 2007, it wasn’t just Dr. Andrew Kwok (BS ’07, PhD ’15) and his students in the classroom.

A reporter and photographer from the Oakland Tribune were there on assignment, following Kwok’s every move throughout his first year of teaching. Kwok, who had recently graduated from the University of Michigan, had moved to northern California to live with friends. He got a job through the Oakland Teaching Fellows, and after six weeks of preparation, was placed in Oakland’s Excel High School, where he was to teach science.

Several weeks into the school year, the first of what would be a series of articles profiling Kwok ran in the Tribune. “New teacher survives first two weeks of high school” read the headline on the front page. “Kwok struggled to teach over the banter and back talk,” the article noted, going on to report that he wondered what he’d gotten himself into. When Kwok read the piece, he was horrified.

“That got back to the administration and the district, and even to my students,” he recalls. His students wondered if they were the reason he was struggling. Well, yes, he told them, but he was also struggling because he was new to the profession. In response, the administration provided Kwok with instructional and classroom management coaches. Peers came into his room to check on him. Kwok credits these supports with ultimately helping him succeed early on in his career. But it didn’t take long for him to realize that the

additional help he had benefited from was rare for new teachers.

By no means does he consider his three-year tenure at Excel long, but Kwok says during his time there, he saw many other new teachers leave after one semester, or even one week.

“It ultimately led me to think about two aspects. One was the importance of classroom management as an opportunity for new teachers to succeed in the classroom right away. The second was figuring out what else it may take to have new teachers stay in underserved schools.”

He recalls a cohort of math students that had three teachers in a single academic year. “They could have left for non-pedagogical reasons, but regardless, it still had the same impact on the students.” The students were deprived of appropriate math instruction that year.

“That really propelled me to go back to school to think about how we can better support new teachers and how we can make sure they have the proper training to succeed,” says Kwok, who returned to his alma mater to pursue his doctorate at the Marsal Family School of Education. Today, Kwok is a professor in the Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture in the School of Education and Human Development at Texas A&M University. His research focuses on beginning teachers and making sure they have the proper preparation and support to succeed in any school, but particularly in underserved schools. He explores the classroom management beliefs, actions, support, and eventual effectiveness of beginning teachers, with the primary goal of having these teachers focus more on building relationships instead of maintaining behavioral control. In another line of inquiry, Kwok studies teacher preparation policy and practice, aiming to improve teachers’ preparation. This area of investigation suggests that teacher education programs should shift their curricula toward more equity-oriented objectives to better prepare teachers for diverse K-12 classrooms. Additionally, Kwok

“That really propelled me to go back to school to think about how we can better support new teachers and how we can make sure they have the proper training to succeed.” Andrew Kwok

explores the perceptions and experiences of beginning teachers. His multiple publications on this topic have led to programmatic change in how leadership offers continuous teacher feedback, coaching supports, and

16 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Kwok

additional professional development.

Kwok’s work has been funded by the U.S. Department of Education, Texas Education Agency, and departments of education in various counties. His research has been published in the American Educational Research Journal, Educational Researcher, Journal of Teacher Education, Urban Education, and Teacher and Teacher Education. Additionally, he serves as an associate editor for Journal of Teacher Education and on the editorial board of Urban Education, informing future scholars and guiding the field. He is a current EdResearch for Action Writing Fellow through the Annenberg Institute at Brown University and recently won research awards from the Association of Teacher Educators, two American Educational Research Association Special Interest Groups, and Texas A&M University.

Just as he hopes his own work will help improve the educational system by influencing changes that will better prepare new classroom teachers, Kwok credits the Marsal School, specifically his mentor Associate Professor of Educational Studies Matthew Ronfeldt and Dean Elizabeth Birr Moje, with preparing him to succeed in academia.

“Michigan trained me beyond what I thought was possible. It helped me think about research in innovative and rigorous ways, and that training has meant everything to me. That’s why I constantly keep in touch and give back, because Michigan provided me with such essential tools to succeed in educational research.”

Distinguished Alumni Award for Primary/Secondary Education

PAtrici A d ign A n

Veteran educator Patricia Dignan (EdD ’82) is a trailblazer, innovator, and tireless advocate. Over six decades, she revitalized schools, shattered gender barriers, and championed community engagement. In a career that has spanned teaching students from preschool to college, Dignan has been an effective, groundbreaking leader.

“Every district or school that I’ve been involved with has gotten either state or national recognition for improved student achievement and parent involvement,” Dignan notes proudly.

Dignan’s life is steeped in rich educational experiences. After attending a one-room schoolhouse in Alpena, Michigan, she earned a teaching degree from Aquinas College and a master’s in education from Eastern Michigan University. She also earned an EdD in education with a focus on administration and supervision from U-M and a JD from the former Detroit College of Law (now Michigan State College of Law).

Her professional journey began in her hometown, where Dignan briefly taught fourth grade before being appointed community school director—the first women in the country to hold such a position. To engage parents in their children’s educational experience, she invited them to attend cooking and exercise classes and roller skating parties, offered parent education classes, and visited students’ homes.

“We opened the school to the community so that people felt more connected with their children’s school,” she explains. When parents and community members get involved, Dignan says, it increases student performance and success, so she has continued the practice throughout her career.

In 1968, Dignan (Bissonette) married fellow educator Patrick Dignan, an

economics teacher and football and baseball coach. Hungry for a professional challenge in Ypsilanti, she joined another U-M graduate, Ken Burnley (BSEd ’64, TeachCert ’64, AM ’69, PhD ’77), to start the first alternative middle-high school for struggling teens in the country. She said students thrived in the small, nontraditional environment.

However, despite her early successes, Dignan still had to battle gender discrimination. She was once offered a lower raise than a male colleague. After giving birth to her daughter on a Friday, Dignan returned to work the following Monday. She had no formal leave and wasn’t allowed to use sick days. Undeterred, she continued to break barriers. Dignan became the first female principal in Ypsilanti in 1972, and was elected president of the Ypsilanti Principals Association two years later.

Reviving underperforming schools became one of Dignan’s specialties. Within

“We made school relevant to not just the community but to life in general,”

Patricia Dignan

a year of starting at Woodruff School, Phi Delta Kappa named it one of the country’s top 100 schools for improved student achievement and community involvement.

When she was appointed to Ypsilanti’s Ardis Elementary School, only half of the students read at the state level. With the help and enthusiasm of her teachers, Dignan revamped the curriculum, instituting one consistent reading system and conceptual instruction, and encouraged grade-level teachers to share in lesson planning. To boost outreach, Dignan launched weekly parent newsletters, workshops, and community education. The results were astounding: within two years, 82 percent of Ardis’ students were reading at the state level, and Ardis ranked as one of the top 20 elementary schools in the state. Dignan created special events at Ardis and other schools, including health, agriculture, vehicle fairs, and even a Renaissance celebration.

“We made school relevant to not just the

17 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Dignan

community but to life in general,” Dignan says. “It was fun and interesting.”

In 1988, Dignan was named assistant superintendent for the Milan School District and then advanced to superintendent, the first woman to hold both positions. While working in Milan, Dignan enrolled at U-M for her doctorate, juggling parenting, schoolwork, and a full-time position. Her doctoral research centered on the role of principals. “In the school hierarchy, the principal is the most important figure at the fulcrum of kids, parents, and community,” she says.

Dignan has always embraced new challenges. In 1995, she joined Falls Church City Public Schools in Falls Church, Virginia, becoming the first female superintendent in the greater Washington, DC, region. Upon her return to Michigan, Dignan was named the first dean of Washtenaw Technical Middle College (WTMC), which was located on the campus of Washtenaw Community College. At the time, WTMC was the only middle college in the country dedicated to technical education. She later launched a series of Detroit-area charter schools. One was Beacon International Academy, a charter elementary school housed in a Detroit church. Dignan asked the teachers to keep journals documenting their challenges, and she shared suggestions and strategies to help.

“It was the most effective teacher education they ever had,” she recalls. “It was also the most fun I ever had.”

Beacon International Academy was an instant success: in six months, students improved their reading levels by three grades, and 98 percent of parents were involved.

In 2000, Dignan joined Detroit Public Schools Community District as executive director. She supervised 58 schools over five years, including Renaissance High School, which earned a coveted National Blue Ribbon Award, and all her schools posted improved reading scores.

Dignan has been featured in the Journal of American Health, Executive Educator, and Instructor and was recognized by the

American Association of School Administrators. The author of six books, she also taught at Eastern Michigan University. She was inducted into Aquinas College’s Hall of Fame in 2002 and Eastern Michigan’s School of Education Hall of Fame in 2005.

“Not only is Dr. Dignan a rare educator, but…[she] has been a trailblazer throughout the entire school hierarchy, creating highly successful programs in preschool, elementary, high school, and college,” says Emily Bryson, a family friend and Eastern Michigan University student, who nominated Dignan for the award.

Dignan remarks that her 59 years of achievements would not have been possible without the love and support of her husband, Patrick, who “kept the home fires burning” while she traveled to make presentations, did in-service training sessions around the state, and attended classes at Detroit College of Law and U-M. She is also grateful for the support of her children—John and Cassandra, and her late son, Jimmy—whom she raised while pursuing her career.

Dignan says U-M’s Marsal Family School of Education gave her a foundation for her administrative career, bolstered her research, and honed her leadership skills. She remains a dedicated Wolverine.

“The University of Michigan has a special cachet,” she said. “You can be out of the country and see people wearing their Michigan gear and instantly feel a kinship. I’m proud to have gotten a degree from U-M.”

Distinguished Alumni Award for Postsecondary Education

Juli A n

V A squez Heilig

Julian Vasquez Heilig (AB ’97, AM ’99) is an ardent believer in the power of community, data, and innovation to effect change. Throughout his distinguished career in higher education, public policy, and civil rights, Vasquez Heilig has deployed research and worked

with like-minded partners to improve educational access and nurture a new generation of educators.

As an undergrad at U-M, Vasquez Heilig studied history and psychology. He found a home in the Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program (UROP), where he investigated educational equity and higher education policy. The experience led him to pursue a master’s in higher education at U-M’s Marsal Family School of Education.

After graduation, Vasquez Heilig joined the Houston Independent School District (HISD) as a research specialist. At the time, HISD claimed it had solved the achievement gap and achieved 0 percent dropout rates; it was called the “Texas Miracle.”

“I wanted to be part of that. At first blush, it appeared to be an ideal place to engage in educational policy and leadership focused on equity,” Vasquez Heilig notes. However, the data behind the scenes at the district told a very different story. Upon closer inspection, Vasquez Heilig found glaring inconsistencies. To delve deeper, he enrolled at Stanford University for a PhD in educational administration and policy analysis and a master’s in sociology, where he collaborated with Dr. Linda Darling-Hammond.

After graduation, Vasquez Heilig joined the University of Texas’s College of Education as an assistant professor. He continued to champion educational equity and access for underserved students, tackling rigorous—and sometimes controversial—research, such as investigating charter schools’ claims about success for Black students and challenging Teach for America’s model. While there, Vasquez Heilig and colleagues crafted a new idea for a locally based approach to school accountability. With Darling-Hammond’s advocacy and support of community-based accountability, the California legislature enacted Local Control and Accountability Plans, or LCAPs, into state law.

Seeking an outlet for his research and advocacy, Vasquez Heilig launched a blog, Cloaking Inequity, which attracted more than 1 million users from 200 countries.

18 Michigan Education • spring 2024

“The blog has been a remarkable gateway to opportunities in my career that I never could have envisioned,” says Vasquez Heilig, who continues to write new posts.

He was invited to advise the NAACP and state and federal policymakers on education. He has appeared in national media on hot-button education reform issues, has traveled widely to community convenings and universities, and has delivered more than 100 talks on civil rights and educational access.

Two years after gaining tenure at UT-Austin, Vasquez Heilig continued his academic work by joining the College of Education at California State University, Sacramento, as a full professor and director of the doctorate program in educational leadership.

“As a researcher, he has been fearless in tackling the toughest issues, using data and research to shine a light on both inequality and hypocrisy,” says DarlingHammond, now President and CEO of the Learning Policy Institute. “As a leader in higher education, he has transformed institutions to focus on equity, to support high-quality research, and to transform practice in powerful ways.”

Vasquez Heilig has also contributed his expertise as a volunteer policy adviser for the Obama campaign and co-chaired the Biden campaign education policy committee. Additionally, he advised Gavin Newsom’s gubernatorial campaign, served as the NAACP’s Education Chair, and was a member of the organization’s Executive Committee in both California and later Kentucky.

But academia has always remained his cornerstone. When the University of

Kentucky (UK) offered him a position as Dean of the College of Education, he accepted the opportunity to serve. “As an academic leader, you can do community engagement and change work and innovation at scale,” Vasquez Heilig explains. “You can be that voice for students, families, and other stakeholders that have been voiceless.”

In his three-year tenure, the UK College of Education doubled freshman enrollment and increased its racial/ethnic diversity by

communities.” To facilitate growth, Vasquez Heilig is focused on increasing faculty and student diversity and raising retention and graduation rates. In one year, retention for Black and Latinx students increased by about four percentage points, and the graduation rate is at the highest level in 25 years.

“This is service work. We commit to the work on behalf of students, staff, and faculty because we want to improve access and equity for communities.” Julian Vasquez Heilig

150 percent, improved faculty diversity by 20 percent, and increased its national ranking to its highest point in recent memory. Vasquez Heilig and his team launched an educational policy center with the NAACP, the first of its kind, and assembled the school’s first Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion (JEDI) student advisory council after the murder of Breonna Taylor in nearby Louisville. In 2022, Gov. Andy Beshear named him a Kentucky Colonel, the state’s highest honor.

Upon joining Western Michigan University as Provost in 2023, he became the first underrepresented minority to hold the position. Vasquez Heilig, who identifies as Latinx and African American, has since devoted his work to collaboration, change, and community. “This is service work,” he says. “We commit to the work on behalf of students, staff, and faculty because we want to improve access and equity for

To foster deeper connections and support for students at WMU, Vasquez Heilig founded a student advisory council, plays weekly basketball games with migrant students, and championed the Student Success Hub, a group of students and staff that helps students navigate and solve academic, wellness, and other challenges that have negatively impacted their educational journey. He also supported initiatives for the university to forge ties to communities that WMU serves. That push is evident in the school’s new Spanish-language marketing strategies, a newly created prison education program at Lakeland Correctional Facility in Coldwater, Michigan, and newly appointed leadership and work groups to address recruiting, retention, and climate for Native Americans, Latinx, Black, military personnel and veterans, and other stakeholder groups.

Vasquez Heilig has also prioritized tackling broader societal issues such as the teacher shortage. Western Michigan is a frontrunner in the state’s “Grow Your Own” program, which trains school staff and community members to become certified teachers, accounting for one-quarter of program attendees across the state.

Vasquez Heilig remains undeterred in his pursuit of excellence. “Our journey is far from over. Satisfaction eludes us. To lead and to educate is to embrace a perpetual dissatisfaction with past achievements, coupled with an unwavering resolve to do even more for communities.” ■

19 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Vasquez Heilig (left) with U-M president Santa Ono

A New Center at The School at Marygrove Reaches In, Out, Around, and Beyond to Advance Justice

clinical assistant professor alaina Jackson and English teacher Bayan Founas launch the rEach center

alaina Jackson (AM ’12, PhD ’18) joined The School at Marygrove (TSM) in 2021 as the Educational Justice and Culture Coordinator, just as the school was returning to in-person learning after the COVID shutdown.

“Our understanding of what schools needed to be and do had shifted,” Jackson recalls. “When I was hired we knew there was going to be some work to do on the ground when it came to culture. We allowed ourselves the space to figure out what that would mean—to be responsive to this community and its needs.”

With a background in restorative teaching practices, Jackson’s goal was to create a center in the high school that would serve as a community hub. Jackson describes restorative teaching practices as those that “support all members of the school community to build and repair relationships (when harm has occurred) centered on care, respect, and open communication.” This year she and Bayan Founas (AB ’14, AM ’19), 10th grade English and creative writing teacher at TSM, founded the REACH Center, which opened its doors in September 2023 with the aim of holistically supporting school culture and climate through a restorative justice and culturally responsive lens.

“I’m really passionate about understanding what it means to practice justice in ways that feel tangible, and in ways that actually impact students’ lives,” says Jackson, who is also a clinical assistant professor of educational studies at the Marsal School. “We are intentional about the REACH Center being a space that’s not your traditional classroom with desks. There are beanbags and alternative seating, and we have interactive elements on the walls for folks.”

Open each day at lunchtime, the REACH Center offers students an alternative outlet to the cafeteria, which Founas notes can be overstimulating. “It gives them somewhere to bond with other students, get away from the day, hang out, and relieve some stress.”

The REACH Center’s mission is dedicated to building a school environment filled with student joy, history, celebration, support, and culture. This is achieved through the use of restorative practices and transformative activities that seek to dismantle stereotypes of Black and Brown kids in schools.

The center focuses on four goals: reaching in, reaching out, reaching around, and reaching beyond. In terms of reaching in, the REACH Center aims to develop a critical consciousness and awareness that equips members of the school community to interrogate the world around them. Reaching out entails creating and experiencing opportunities for mentorship and connection. Reaching around means the center engages in responsibilities toward the collective struggle against racism and all forms of oppression and injustice within schools and within communities both near and far. Reaching beyond conveys how the center challenges participants to imagine the possibilities of a more just, humane, and equitable school and world.

The center aims to help teachers and staff build restorative practices into their teaching and the culture of the school. Each Monday, in the

20 Michigan Education • spring 2024

Jackson Founas

principal’s weekly email to faculty, Jackson and Founas include tips on ways to achieve this. “It’s quick strategies they can use during the week,” says Founas. “We try to make it as light a lift as possible.”

During its inaugural months, the REACH Center focused on providing opportunities for members of the school community to transcend the traditional student-student or student-teacher relationship. Through its “Mondays at the REACH” lunchtime series, the center offered programming such as trap yoga, game sessions, karaoke, and gingerbread house decorating. During the month of November, the center celebrated the 50th anniversary of hip hop by honoring the genre’s often overlooked non-male voices as part of their Eats and Beats series. In February, the REACH Center supported a student-led committee that organized a series of events for Black History Month. The lineup of offerings included a Black Lives Matter at School week of action, a spirit week highlighting both historical and contemporary aspects of Black heritage, and a Divine Nine HBCU

“I’m really passionate about understanding what it means to practice justice in ways that feel tangible, and in ways that actually impact students’ lives.” Alaina Jackson

Day that brought in people from outside the school to build community. The month concluded with a dynamic showcase of performing arts, and awards.