8 minute read

Irish working-class voices: an extract from our latest anthology

FROM THE SHOP FLOOR

For past catalogues, we’ve loved going behind the scenes at some of the UK’s beloved bookshops, chatting to their booksellers and finding out more about their stores. In light of the pandemic, which has caused retailers to shut, we thought we’d highlight a few wonderful bookshops which have taken to selling their wares online. Please do give them a virtual wave and help to support some brilliant independent booksellers.

Advertisement

Book Corner

www.bookcornershop.co.uk

Fox Lane Books

www.foxlanebooks.co.uk

The Little Bookshop Cookham

www.thelittlebookshop.info

Reading Roots

www.readingroots.co.uk

FILE SEEMS FAULTY

Sam Read Books

www.samreadbooks.co.uk

Shelflife Books and Zines www.shelflifebookshop.com

No Alibis Belfast

www.noalibis.com

Ullapool Bookshop

www.ullapoolbookshop.co.uk

6

THE 32

The 32 is a celebration of working-class voices from the island of Ireland. Edited by award-winning novelist Paul McVeigh, this intimate and illuminating collection features memoir and essays from established and emerging Irish voices including Dermot Bolger, Roddy Doyle, Lisa McInerney, Lyra McKee and many more. As in Common People – an anthology of working-class writers edited by Kit de Waal, and the inspiration behind this collection – The 32 sees writers who have made that leap reach back to give a helping hand to those coming up behind.

Extract from ‘The Gaatch’ by Kevin Barry

My father’s family kept an uncle in the attic. This was in the house on Brown’s Lane, which was off Lord Edward Street, about 500 yards from Colbert Station in Limerick city. The McCourt family of Angela’s Ashes fame lived a couple of lanes away. In my father’s house there were five children, the two parents, and the uncle in the attic. I don’t know what this uncle’s name was, or whose side he was on, or whether he was an invalid or just a bit odd in himself, but I know that he was kept in the attic.

This must have been around the late 1920s or early 1930s. My father left school at about ten years old, as did most of the kids who lived in the inner city at that time. He became a messenger boy around town before eventually getting work with CIÉ down at Colbert Station – a lot of the family ended up working there, mostly as wagon-makers.

Of the family lore that survives, much of it concerns my grandmother, Mary Kate, who died long before I was born. She was an unconventional woman for the time in that she went to the pub alone – the lounge bar of the Railway Hotel – and also she went to the bookmaker’s. This was considered close to scandalous at the time.

The Railway Hotel is on Parnell Street, opposite Colbert Station, the same street where my mother’s family lived. They had moved in from west Limerick in the 1930s, and my grandfather and grandmother on that side always seemed to me like country people. After living in a flat on Parnell Street for a while, they got a council house in Ballinacurra Weston, a house that stayed in the family until my aunt, the last of the family in Limerick, died in 2005.

When I was born, in 1969, we lived in a council house on Hyde Road, about a half-mile down from Colbert Station, and about the same again from the site of Brown’s Lane, which by then had been knocked down.

7

Working-class families tend to move around in fairly tight circles. In 1972 we bought a house – I think for about £1,500 – in a new estate of semi-ds called Ballinacurra Gardens, about a mile from my mother’s parents’ house in Weston. A lot of the families who moved into the raw new estate were also coming from council houses. Most houses had about five or six kids knocking around in them and the estate was teeming, especially on the summer evenings – it’s very quiet now. The estate was close to the Catholic Institute tennis club, long established to service the very respectable neighbourhoods of Rosbrien and Greenfields nearby. We didn’t join the tennis club.

I went to school at CBS Sexton Street, a couple of hundred yards from Colbert Station. Thinking about my schoolmates, I’d say about three quarters of us were from working-class backgrounds and the rest were lads from the county who tended to be the good hurlers. I’d wanted to go to Crescent College Comprehensive for secondary, not least because it had girls in it. I sat the entrance exam, which consisted of multiplechoice questions, and I came out of it pretty certain that I’d scored 100 per cent. I didn’t get offered a place in Crescent Comp – you generally had to have a brother or sister who’d gone there before you, and it was the case with Crescent Comp that the brothers and sisters were mostly from the better areas, from the middle-class estates, and from the old, established roads. The casual way schools in Ireland are segregated very strictly along class lines still astonishes me.

About a month before I sat my Leaving Cert in 1987, one of our teachers came in one morning and gave us a talk about our destinies. We were the top-streamed class in the school, considered to be the smarter kids, the good workers. But still and all, he said, Ye’re likely to end up in bum office jobs around the town. I remember the phrase exactly – ‘bum office jobs’. He spoke for quite some time, and he painted a grim enough future. If we didn’t watch ourselves, he said, we’d be working in dreary little insurance offices, and we’d be answering to bosses who had gone to the Crescent Comp. They would be no smarter than us, he said, but they’d have gone directly to university, while we’d have been doing bookkeeping courses in the tech. He explained that it was systemic. His message, quite passionately delivered, was that we should struggle with all of our resources not to be placed in the boxes that were waiting for us. He suggested that the limits of our futures were very often set by the limits our families foresaw for us. He had been watching all this play out for years, he said, and it made him angry. We were all a bit rattled by this talk. We hadn’t seen it coming.

8 A couple of years later, I began working my first job as a junior reporter on a local newspaper. On Thursday mornings I attended the sittings of Limerick District Court. I did the courts for a couple of years, and I can’t remember ever hearing a working-class defendant’s word taken over the word of a guard. You could predict with high accuracy the forthcoming judgements from the look of the defendant taking to the witness stand. If he or she had a working-class kind of gaatch to them – as we’d say in Limerick, meaning that they carried themselves in a certain way, dressed in a certain way, spoke in a certain way – they would very likely be found guilty. We’d often discuss it in the reporters’ box. Some lad in a tracksuit would be sauntering up to give his account of the night in question, with a face on him, and we’d nudge each other, and slyly wink. Not a chance, we’d say, not a chance…

Find The 32 on page 73 9

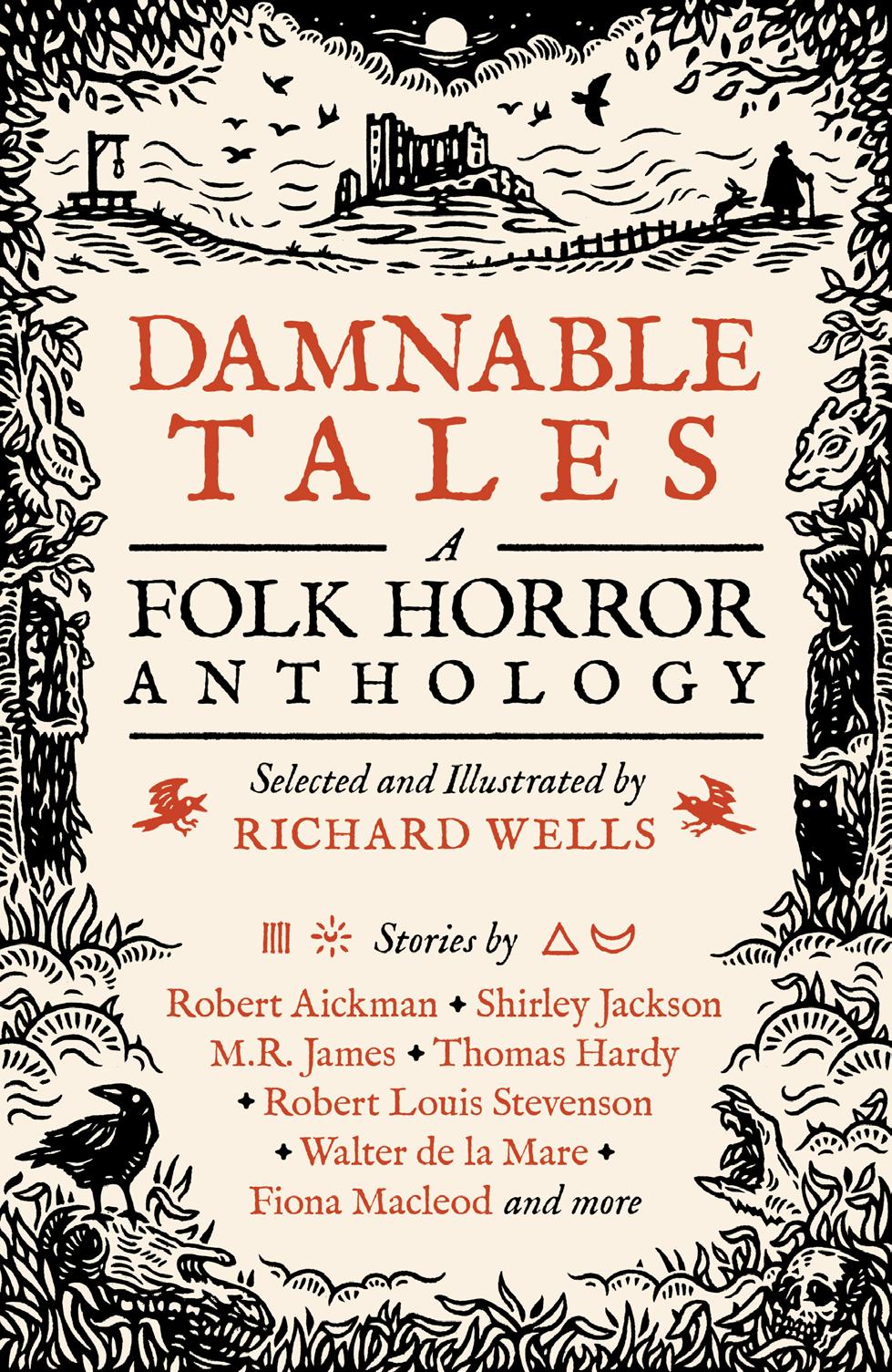

DAMNABLE TALES: A FOLK HORROR ANTHOLOGY

A richly illustrated anthology which gathers together classic short stories from masters of supernatural fiction including M. R. James, Sheridan Le Fanu, Shirley Jackson and Arthur Machen, alongside lesser-known voices in the field including Eleanor Scott and Margery Lawrence, and popular writers less bound to the horror genre, such as Thomas Hardy and E. F. Benson.

Selected and beautifully illustrated by Richard Wells, these stories stalk the moors at night, the deep forests, cornered fields and dusky churchyards, the narrow lanes and old ways of these ancient places, drawing upon the haunted landscapes of folk horror – a now widely used term first applied to a series of British films from the late 1960s and 70s: Witchfinder General (1968), Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and The Wicker Man (1973).

Richard Wells is an illustrator and graphic designer. Primarily working in the television industry, he has provided graphic props for the likes of Poldark, Sherlock, Doctor Who and the 2020 BBC adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Outside of his television work, he makes and sells his own darkly folkloric artwork, often lino-cut and hand-printed. His recent work includes a series of prints based on the ghost stories of M. R. James.

‘Thanks (I think) to the social media popularity of my series of lino prints based on the ghost stories of M. R. James, it was a nice surprise to be contacted by the folks at Unbound about a possible collaboration. I had at the back of my mind a plan to expand my print series to cover a wider selection of vintage “folk horror” style tales. So to make this the basis for my first illustrated book seemed the obvious choice. When I pitched the idea, I only had a few tales I knew I wanted to include, so I then had the pleasure of searching for more. Cue lots of scouring through vintage horror omnibus books for stories that might fit the bill, and tracking down recommendations from fellow fans of the genre. Searching for that feeling of rural uncanny; chilling, rustic tales that take place in the great outdoors. With the first lockdown hitting

10 just as I began, I was very grateful of the project to keep me occupied, managing to keep to a routine of one new linocut illustration per week. It was a thrill to see how warmly the project was embraced, and I can’t wait for people to receive their copies.’

– Richard Wells, editor and illustrator of Damnable Tales

11