A privilege to lead the university

NTENSE WEEKS OF election campaigning, debates, party leadership debates and sta tistics have, for obvious reasons, filled the media and will continue to do so during the formation of the government. We can still only speculate as to what this will mean specifically for higher education and resear ch. Regardless, I am once again struck by the strong impact that our researchers at the Uni versity of Gothenburg have had on the media reporting. They helped to guide, explain, ana lyse and balance. The most prominent in this context are of course our political scientists, but our expertise is also used extensively in other areas. It is really interesting and always makes me very proud of the university. I know how much work goes into it.

The exposure during the elec tion coverage is a clear example of the University of Gothen burg's extensive scope. Another is the multitude of talking points and seminars that were presen ted by us during the Gothenburg

Book Fair the other week. Our university has outstanding education and research in all scientific fields, as well as a high appeal and is strongly competitive. I sincerely believe and hope that many suitable candidates will apply for the position of vice-chancellor, which will become available on July 1, 2023. It is truly a privilege to be trusted to lead the University of Gothenburg, but I have decided not to run for another three-year term. Having said that, almost a full year of my term remains and there is much left to do. It is my intention not to slow down, I intend to continue working, and in some cases finish, as much as is possible of what we started to gether. The most important thing for me is to hand over a university that is in good order. A university that is improved and revitalized!

Vice-Chancellor EVA WIBERG

Editor-in-chief: Allan Eriksson, phone: 031–786 10 21, e-mail: allan.eriksson@gu.se

Editor: Eva Lundgren, phone: 031–786 10 81, e-mail: eva.lundgren@gu.se

Photographer: Johan Wingborg, phone: 070–595 38 01, e-post: johan.wingborg@gu.se

Layout: Anders Eurén, phone: 031–786 43 81, e-mail: anders.euren@gu.se

Address: GU JOURNAL, University of Gothenburg Box 100, 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden E-mail: gu-journal@gu.se Internet: gu-journal.gu.se ISSN: 1402-9626

Translation: Språkservice Sverige.

The Journal has a free and independent position, and is made according to journalistic principles.

NEWS 04–13

The 100 researchers at the top.

A research leader is like a star chef.

Political scientists best in Sweden.

Nobel prizes lead to top ranking.

Summer school in Gothenburg.

How to avoid bad journals.

PROFILE 14–17

The Arctic back and forth.

REPORT 18–23

Messages from Ukraine.

Seeking to understand extremism.

Will an AI take your job?

14Looking for new plants

Masthead

Recipe for a Successful Researcher

ANY OF THE ARTICLES in this issue are about how to be successful in research. One of these lists the top one hundred researchers who were given the most external grants and what determines who receives these. It is concluded that a large program does better than several smaller projects, and that having a committed research leader who encourages the other team mates also plays a key role in improving these prospects. We have interviewed Gunnar Köhlin, leader of Environment for Deve lopment, who points to Elinor Ostrom as an example for how a good research leader should be.

IN THE LATEST Shanghai-ranking, Political Science at GU ended up in 19th place among world leading departments – which ranks it the best in Sweden. Again, this positive outcome is a result of dedicated research leaders and large institutes within the Department, such as QoG, V-Dem and GLD.

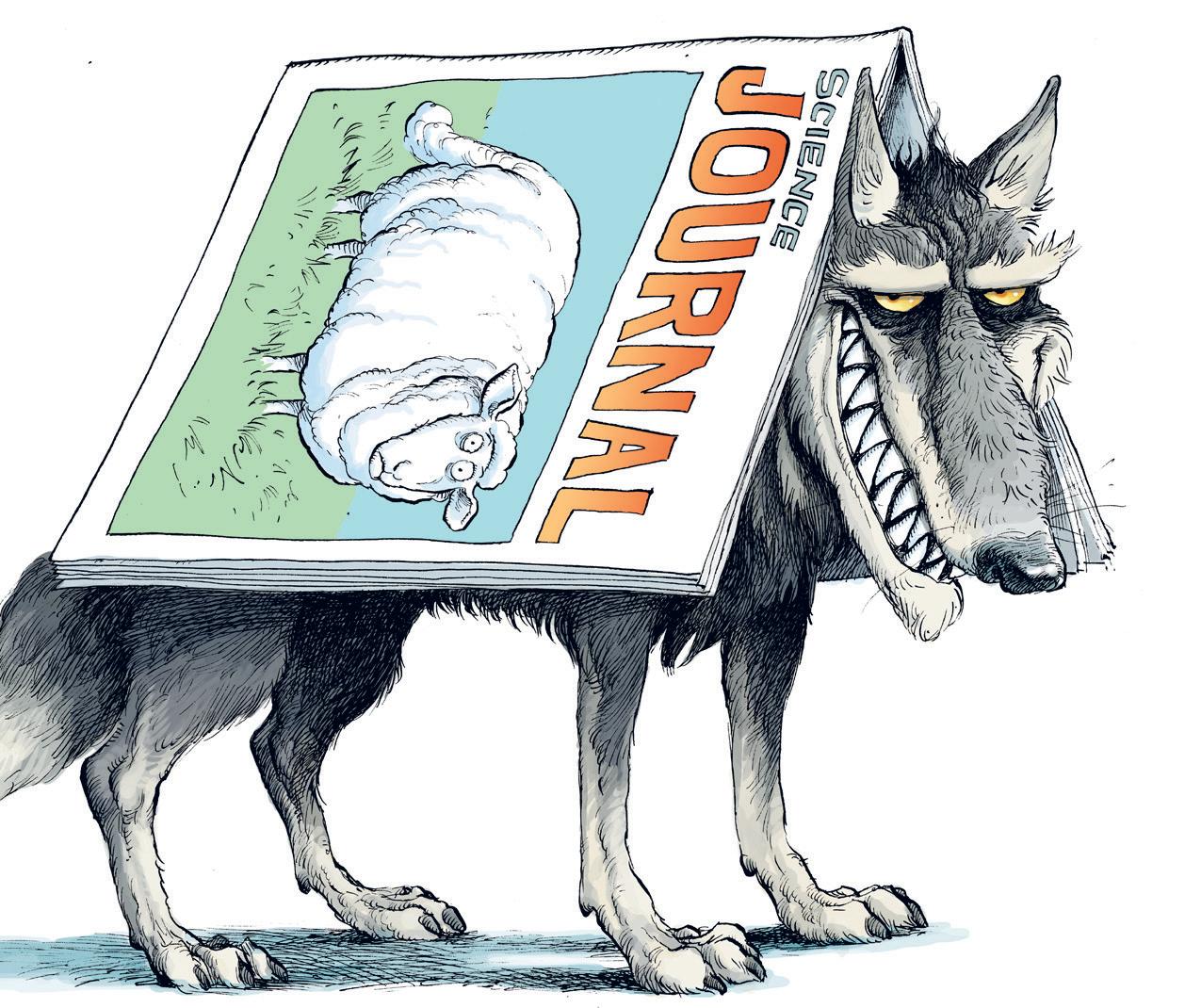

The problem of so-called predatory journals is another hot topic. Therefore, the University Library has started a series of webinars focusing on what to be aware of when choosing a journal. One such

warning sign would be the length of the peer review process; if very little time has been spent, then there is cause for concern.

Climate change is advancing rapidly in the arctic, explains this issue’s profile, Anne Bjorkman. She is doing research on how plants adapt to the change and has reached to some surprising conclusions.

THE WAR IN Ukraine continues to affect us all. For those interested in snapshots from the war, there is Messages from Ukraine, a small booklet that has been made as a collaboration between resear chers and an illustrator.

Finally; are you afraid of AI taking over your job? The fear is not unwarran ted, says Erik Winerö, who has tested the program GPT-3. Ask the program to write a poem in the style of a well-known writer, and it will do just that – and rather well too. The question is; should this make you worried? Not really, argues Erik Winerö, who thinks creativity will always be important, regardless of the effectiveness of new computer programs.

We hope you will enjoy this issue!

Allan Eriksson & Eva LundgrenHard work brings great success

Göran Bergström leads the giant project Scapis.In the years 2017–2021, the 100 most successful researchers at the University of Gothenburg brought in SEK 4.2 billion in external grants.

Sahlgrenska Academy's researchers accounted for just over 2.4 billion of the funding.

GÖRAN BERGSTRÖM, Professor of Cardiovascular Research, is at the top of the top-100 list. He is the person responsible for Scapis, a unique knowledge database for researchers who want to investi gate cardiovascular and pulmo nary diseases.

– The database contains samples and images from 30,000 randomly selected healthy participants between the ages of 50 and 64 collected since 2012. They have undergone thorough medical examinations, including X-rays, ultrasound examinations and pulmonary function tests. They also had to answer lifestyle questions.

Anyone doing research in the field is welcome to apply to use the data. Amongst the approx imately 1,500 variables, the researchers can select the ones in which they are interested.

– The database will continue to grow, at least until 2040 but

GÖRAN BERGSTRÖMhopefully even longer, says Göran Bergström.

The main financier is the Hjärt-Lungfonden (the Heart and Lung Foundation), but the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Founda tion, Vinnova and the Swedish Research Council also support the project.

– I think that one reason why the project received so much funding is precisely the stated goal of sharing. Some researchers keep their data to themselves, but the very point of research is to contribute to public knowled ge. Scapis is for everyone who is interested in cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases.

I think that one reason why the project received so much funding is precisely the stated goal of sharing.

Top 100. These researchers have raised most money over 5 years.

Project leader Faculty Total Project leader Faculty Total

Göran Bergström Gunnar Köhlin Fredrik Bäckhed Henrik Zetterberg Elisabet Carlsohn

Lars Borin

Monika Rosén Volpe Giovanni Staffan Lindberg Anna Wåhlin Maria Falkenberg Johan Ling Jonas Nilsson Johan Åkerman Gunnar Hansson Ruth Palmer Andrew Ewing Sven Enerbäck Niklas Pramling Maureen McKelvey Björn Redfors Thomas Nyström Katharina Stibrant-Sunnerhagen Johan Woxenius Ingmar Skoog Raimund Feifel Eva Forssell Aronsson Magdalena Taube Annika Rosengren

Ulf Smith

Kristina Sundell Linda Johansson Davide Angeletti Thierry Coquand Ann Hellström Kaj Blennow Peter Thomsen Sebastian Swart Claes Ohlsson Joakim Larsson Björn Burmann Romeo Stefano Ali Harandi Anders Ståhlberg Magnus Simrén Richard Neutze Adel Daoud Margit Mahlapuu Kristian Kristiansen Anders Rosengren

Sahlgrenska Business Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Humanities Education Science Social Science Science Sahlgrenska Humanities Business Education Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Education Business Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Business Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska IT Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Social Science Science Humanities Sahlgrenska

The data comes from the EKO database and

613 499

648 720

063 416

543 414

948 165

069 770

391 701

788 475

270 102

741 323

530 000

519 832

889 819

993 053

647 278

764 000

905 825

920 254

029 027

100 000

450 324

722 000

429 555

174 800

782 294

283 073

150 000

612 997

818 748

320 246

621 741

340 000

113 372

850 000

731 150

402 434

568 113

571 119

233 823

756 415

495 000

319 694

047 975

831 838

176 027

114 219

009 530

916 710

818 358

597 976

61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70.

72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. 79. 80. 81. 82. 83. 84. 85. 86. 87. 88. 89. 90. 91. 92. 93. 94. 95. 96. 97. 98. 99. 100.

Åsa Löfgren Bo Söderpalm Håkan Pleijel Märta Wallinius Shibuya Hiroki Jan-Eric Gustafsson Sebastian Westenhoff Anders Ekbom Martin Holmén Helena Carén Elmir Omerovic Lena Carlsson Martin Henning Karl Börjesson Jan Holmgren Göran Landberg Jan Borén

Jonas Hugosson Magnus Gisslén Nir Piterman Claes Gustafsson Bengt Hallberg Mats Brännström Jenny Nyström Alyssa Joyce Jan Lötvall Liss Kerstin Sylvén Chandrasekhar Kanduri Ann Frisén

Krefting Gemensamt Medicin Kerstin Persson-Waye Thomas Sterner Andrea Spehar Dag Hanstorp Per Arne Albertsson Leif Klemedtsson Marcus Lind Anna Martner Jörg Hanrieder Mattias Hallquist Anders Lindahl Linda Engström Ruud Anna-Carin Olin Emma Börgeson Paul Russell

Sofia Movérare Per Karlsson Gunnar Steineck Volkan Sayin Milos Pekny

Business Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Science Education Science Others Business Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Business Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska IT Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Education Sahlgrenska Social Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Business Social Science Science Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Science Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Humanities Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska Sahlgrenska

large annual amounts research leaders have raised 2017–2021.

that have been posted at a department or a unit are not included.

588 964

440 000

361 265

880 000

868 700

931 000

813 659

301 315 27 764 423 27 244 495 26 849 300 26 789 607

523 000

423 038 26 241 521 25 322 001 24 814 501 24 424 521

170 012 23 265 148 23 248 000

874 600 22 588 200 22 141 596 22 046 871

732 050

660 685 21 586 800 21 386 200

000 000

906 388 20 843 389 20 709 989 20 230 950 20 176 100

159 822

936 250

847 000

784 396

765 231

735 581

727 231

665 573

660 113

582 636

504 600 18 800 000

716 664

386 709 18 328 785

statistics do not show the extent to which the funds have been used.

The role of the lead resear cher is important, says Göran Bergström.

– Running a major resear ch project is a very hard job and requires both energy and endurance. While having the ultimate responsibility, you also have to be inclusive and incorporate all the good ideas from your colleagues. A lead researcher must collaborate with all the different experts within the project and build a strong team that works towards a common goal.

Göran Bergström's own research is about finding mo dels to predict who is at risk of heart disease.

AMONG THE MANY researchers who collaborate with Scapis is Fredrik Bäckhed, Profes sor of Molecular Medicine. He researches the impact of gut bacteria on health and disease. To a large extent, it is about translational research, and very close collaboration with the clinic.

– We are trying to find causal links between gut bac teria and, for example, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Among other things, we study how microbial composition affects processes in organs such as the liver, adipose tissue, muscles and pancreas, both in healthy people and in people with metabolic diseases.

One reason for the success is the location of the research team with premises at Sahl grenska University Hospital.

– WE HAVE ACCESS to both worlds, both researchers in molecular biology and micro biology, as well as practising clinics. We can run into each other in the corridor, talk about a problem and solve an issue, without booking a me eting. Moreover, we invest in the long term, instead of scrat ching the surface, we try to understand the very mecha nisms that cause disease.

The lead researcher's task is to function as a coach, says Fredrik Bäckhed.

– You point out the direc tion and are responsible for raising money. But without a team it is not possible to be a coach. All our colleagues are skilled in their field, whether it is microbiology, physiology or bioinformatics. My team is also very international with employees from 12 different countries, which contributes to different perspectives. We set a high bar and sometimes our discussions can be very lively.

FREDRIK BÄCKHED is also involved in research com munication. Recently, his research team launched the website Livet i tarmen (Life in the Gut) with popular science

facts and answers to common questions.

– The third task is very important. But it has little significance when it comes to research grants, where good research and well-formulated applications are what matter.

HENRIK ZETTERBERG , Pro fessor of Neurochemistry, researches neurodegenerative diseases. Among other things, his team has developed a simple blood test for diagno sing Alzheimer's disease and is now working on trying to develop tests for other cogni tive diseases as well.

– About 15 years ago, few people cared about Alzhei mer's disease. But in recent years the field has really taken off and developed very quick ly. The fact that things happen is of course interesting for funding bodies. We have received funds from both Swedish and international financiers, including the Gates Foundation. The more grants we get, the more we can do, which leads to even more grants; we are quite simply in an upward spiral.

Although the lead rese archer is important, Henrik Zetterberg emphasizes the importance of the team.

– When you apply for a grant, you specify what expertise the team possesses. Having talented colleagues

simply increases the chances of getting grants.

In fifth place on the list is Elisabet Carlsohn in her role as Head of Core Facilities.

– The fact that we are so successful when it comes to attracting external funding is partly due to long-term work, tremendous commit ment and the extensive skill of our experts, and partly to our close collaboration with research teams that conduct high-quality research. The visible result is the overall allocation of external funding to our research facilities and would not have been possible without our fantastic experts, who backed and promoted the applications, Elisabet Carl sohn explains.

CORE FACILITIES supports research teams mainly in the life sciences, including through expert advice and training. This provides access to advanced equipment, tech niques and support for pro jects in terms of experimental design, sample preparation, data collection and analysis. Core Facilities is open to all researchers, at the University of Gothenburg, other univer sities and also within industry.

More funding with large programs

Number two on the list is Gunnar Köhlin, Director of Environment for Development (EfD).

– The purpose of the centre is to train environmental economists in developing countries and to increase collaboration on environmental issues between researchers and politicians, so that research has a real impact on society.

SINCE 2019, EfD has been a separate unit at the School of Bu siness, Economics and Law. But the organisation was started in 2007 as an international network of research centres, mainly in the Global South.

– Since then, the organisation has expanded, most recently by moving parts of Gothenburg's Centre for Sustainable Develop ment (GMV) there, says Gun nar Köhlin, Senior Lecturer in Economics.

One success factor has been that EfD is a programme where many parties work together and not just a time-limited project.

– A LARGER PROGRAMME makes it possible to create the infra structure required to draw in greater funds. Having several people who can work with the programme for many years also provides stability. EfD also has its own research fund with funding that is sent around the world, which enables further collabo rations.

The most common way to attract external funds at the Uni versity of Gothenburg is to have individual researchers apply for grants from the Swedish Research Council or Formas, for example, Gunnar Köhlin points out.

– When it comes to major programmes, for example app lications to the EU or Linnésats ningarna (the Linnaeus Initiati ves) a number of years ago, we have been less successful at the University of Gothenburg. We do not really have the structure that enables a more interdisciplinary organisation. Not even when it comes to the UGOT Challenges, which was the University of Gothenburg's own investment in major societal challenges, are there any specific plans for how the centres can continue to sur vive and be supported adminis tratively and financially.

Although Gunnar Köhlin is responsible for EfD, he points out that he certainly does not do everything.

– When I visited Nobel laureate

Elinor Ostrom at her centre in Bloomington, Indiana, I realized that being a world-renowned re search leader is like being a star chef at a Michelin restaurant. It is important to be involved, keep track of things and act as a mentor. But it is also important to create a social context for the team and recognize their skills. The real challenge is maintaining momentum as the team grows or changes.

EfD is primarily financed by Sida.

– But many other stakeholders have also supported the organi sation over the years, both at the University of Gothenburg and around the world.

…I realized that being worldrenowned leader is lika being a star chef at a Michelin restaurant.

GUNNAR KÖHLIN

– A good research environment also benefits education, says Mikael Gilljam.

Political scientists at the top of ranking

In the latest Shanghai Ranking, the political scientists at the University of Gothenburg are ranked 19th in the world. It is the highest ranking in Sweden and second highest in the Nordic region.

A focused publication strategy is one explanation for the good result.

IN THE SHANGHAI RANKING , the subject Political Science is mainly measured bibliometrical ly, that is, it is mainly publica tions and citations that count. Admittedly, there is an indicator for prizes, but it has never been relevant to Swedish universities.

The University of Gothen burg's high ranking is no coinci dence, but follows a long-stan ding trend.

– We adopted a strategy a few years ago which means that we strive to constantly publish

better and better articles in increasingly higher ranked jour nals, explains Mikael Persson, Assistant Head of Department at the Department of Political Science. Since the 1990s, the department has also worked to create an international culture, in which Bo Rothstein has been important. At major American conferences there are usually a couple or perhaps three political scientists from Lund, Stockholm and Uppsala – but about twenty from Gothenburg.

The only higher education institution in the Nordics that ranks higher than the Univer sity of Gothenburg is Aarhus University, which ended up in 10th place.

– We have a number of colla borations with Aarhus, including a number of our PhD students who are working there now. The goal is, of course, to learn from them and become even better.

At major American conferences there are usually a couple or perhaps three political scientists from Lund, Stockholm and Uppsala – but about twenty from Gothenburg.

The Department of Political Science is strongly research oriented. They bring in a lot of external funding, in the last five years around SEK 76 million a year.

– It is quite a lot considering that the department is not that big, having only around 75 re searchers, says Head of Depart ment Mikael Gilljam. One reason for the high ranking is probably that our researchers are encoura ged to take a very broad interest in research, and not just devote themselves to their own special area. The ideal is that everyone should try to be interested in everything that goes on at the department. Good research leads to more interesting and better courses, the research environme nt thus rubs off on the teaching, so in return we get a vibrant teaching environment.

Getting an article into a really prestigious journal, such as

the American Political Science Review, requires hard work, explains Mikael Persson.

– The best journals receive perhaps 1,500 submissions per year but only accept a few dozen articles. Writing an article that is of so high a standard that it has a chance in the tough competition takes a long time, it can take several years of work. Someti mes we are lucky and manage to publish in several high-ranking journals, sometimes it goes less well, even though the work we have done is equally good. So while we are very proud of the good ranking, we must remem ber that a slightly higher ranking here or there does not say much about the level of quality at the department. However, the fact that there is a positive trend where we have been high in the ranking for several years is proof that we are good. And it certainly has an impact on our ability to recruit employees and attract new students.

Also within Public Administra tion, which is one of the political science department's speciality fields with a majority of publi cations coming from there, the University of Gothenburg was ranked highest in Sweden, in 23rd place.

Difficult to measure quality

Also within Human Biological Sciences and Dentistry & Oral Scien ces, the University of Gothenburg ranks highest in the country, at 23 and 33, respectively. At the same time, Biological Sciences is ranked at a creditable 36th place.

– The Shanghai Ranking is the one of the major rankings where the University of Gothenburg obtained the best results. There are many reasons, but one is Arvid Carlsson's Nobel Prize in 2000, explains Magnus Machale-Gunnarsson.

HUMAN BIOLOGICAL Sciences is a broad field that includes most things to do with human biology and preclinical medicine, says Per Sunnerhagen, Deputy-Head of Department of Chemistry and Molecular Biology.

– Maybe it could be translated as “bio medicine.” The ranking reflects how much we publish and are cited in prestigious journals, among other things. This time our ranking is very good. It is certainly impor tant for our reputation and our ability to attract both employees and students. But different rankings weigh different things in different ways and how a university goes up or down does not really say much about the day-to-day operations.

Magnus Machale-Gunnars

son, analyst at the Planning and Follow-up Section, who compiled the results. He agrees that rankings must be taken with a fairly large pinch of salt.

– In the Shanghai Ranking, the univer sities receive points for major prizes, for example. One might think it strange that the University of Gothenburg gains prestige because of Arvid Carlsson's Nobel Prize, but after all, it was only 22 years ago. It is true that prizes that were awarded more

than 90 years ago are not counted, but Uppsala University still receives points for the Arne Tiselius Chemistry Prize in 1948 and Stockholm University benefits from the George de Hevesy Chemistry Prize in 1943. And Harvard's 161 Nobel Prizes are, of course, hard to top.

In the Shanghai Ranking, there are two indicators for the Nobel Prize, which together make up 30 percent of the total score.

– That's a lot. For universities fur ther down the list, a single prize plays a very important role. The University of Gothenburg currently gets 22.1 points in total and is ranked in 138th place. If we had not had the Nobel Prize, we would have received 19.2 points and ended up in 190th place.

Another way to assess quality is to use reputation surveys. Researchers get to an swer questions about which universities are the best in their field, says Magnus Machale-Gunnarsson.

– IF THE FIELD IS very large, such as “medicine,” which is not unusual, it is of course impossible to answer. Often, the refore, respondents often state the most famous universities, if they answer at all; the response rate is somewhere around 5–10 percent. So while a good ranking for the University of Gothenburg is wonder ful and should be celebrated, we should not get too despondent about a lower ranking on another occasion.

Text: Eva Lundgren Photo: Shutterstock

Would you like to find out more? In this clip Magnus Machale-Gunnarsson provi des a little more information: https://play. gu.se/media/t/0_zf09rjni

Summer school on site in Gothenburg

This year's version of the University of Gothenburg's summer school, with the theme of sustainability based on the 2030 Agenda, attracted students from all over the world. We had 400 applicants for 120 seats.

– The students were overwhelmingly positive, says Elin Fransson, Project Coordinator.

THE UNIVERSITY OF Gothen burg's summer school, Summer School for Sustainability, had to be cancelled due to the pande

mic in 2020 and was held for the first time in 2021, but online. This year, the event was held on site and welcomed students from all over the world to delve deeply into issues related to the global sustainability goals and the 2030 Agenda for five weeks.

– THE IDEA IS to promote oursel ves internationally towards part ner universities and international students, and to show what we can offer in Gothenburg, says Elin Fransson, Project Coordina tor for the University of Gothen burg's summer school.

The summer school works on

the basis that the three dimensi ons of sustainable development – social, economic and environ mental – must be integrated into the organisation. In this way, the University of Gothenburg wants to strengthen its relevance as a social stakeholder and partner in order to make an impression on societal development and contri bute to the Global Sustainable Development Goals set by the UN General Assembly in the 2030 Agenda and which the University of Gothenburg has adopted.

– In the announcement for departments and faculties to nominate courses, there is a

We receive a wide variety of courses that are all linked to and united by the idea of sustainability.

demand for courses that have a sustainability theme, in some way or another. We receive a wide variety of courses that are all linked to and united by the idea of sustainability.

The courses offer everything from pedagogy, biology and archaeology to digitalization and political science, says Elin Frans son. For example, you can learn about petroglyphs, biodiversity in Western Sweden and about managing migration.

– THE RANGE OF courses for 2023 is set, but for 2024 we hope to receive further course proposals from more faculties. In the long term, the initiative is about be ing able to showcase the entire breadth of the university.

Among the 120 students who participated in this year's sum mer school, there was both di versity and breadth. There were students from many different countries, varying backgrounds and of mixed ages. And from the evaluation that is being conduc ted right now, we can ascertain that the majority of the partici pants were appreciative.

– SOMETHING THAT both stu dents and teachers highlighted as positive is precisely the hete rogeneous mix that contributes new perspectives on various sustainability challenges.

Even in the peripheral programme associated with the summer school, the goal was to let the idea of sustainability per meate everything. Among other things, blankets were purchased together with Welcome Services, which will be reused for future summer schools. There was also a Free Shop at Studenternas Hus and at Olofshöjd, where you could pick up cutlery and kitchen utensils, things that had been forgotten or left behind, and which were then returned for further use. All the procure ment of food was also aimed at organic, vegetarian and vegan options.

– We also had a self-guide about how the students could discover the city. In it, we wrote

about how to get around using public transport and rental bikes. We also included informa tion about all the second-hand and thrift shops that we know of, as well as shops and workshops that do repairs, and sell locally produced and sustainable alter natives, says Elin Fransson.

Text: Hanna Jedvik Foto: Johan Wingborg– Both students and teachers appreci ated the heteroge neous mix, says Elin Fransson.

FACTS

COURSES at GU:s Summer School for sustainability. Biodiversity in Western Sweden

Teaching Sustainable development from a Global perspective

Digitalization in a Changing World

Managing Migration Documentation and Interpretation of Rock Art

If, as a course leader, you are interested in information about how you can integrate a course into the summer school, you can contact Elin Fransson. Summerschool@ gu.se!

Be aware of predatory journals!

Recently, the problem of so-called predatory journals has been a hot topic. To support the University of Gothenburg's researchers, the University Library offers a number of different webinars on this current theme.

THIS SPRING, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences presen ted a new report on predatory journals from the InterAcademy Partnership, IAP: Combatting Predatory Academic Journals and Conferences. Predatory journals refer to journals that, in exchange for payment, publish scientific studies that have not been peer reviewed.

Eva Hessman, librarian at the Biomedical Library, confirms that it is a growing concern.

– We receive more and more questions from researchers and PhD students, but also many pe ople who need support when it comes to reviewing publication lists from applicants in connec tion with recruitment.

This is precisely why the Uni versity Library offers webinars to increase knowledge about iss ues related to dubious journals.

In order to meet the increased demand and improve knowledge about research ethics, Eva Hess man, together with her collea gues, has started a collaboration with the Council for Research Ethics at Sahlgrenska Academy. This spring they held a series of webinars under the title 20 minutes for researchers. Avoid predatory journals, focusing on what red flags researchers should be aware of when choosing a journal.

– DURING OUR WEBINARS , we try to have a nuanced debate by problematizing the concept of predatory journals. Scientists are not prey. You have as much responsibility for your choice of publication as when it comes to method and analysis of data, says Eva Hessman.

During the webinars, the rese

archers have the opportunity to ask questions and dis cuss the issue. It might involve which signals to pay attention to in order to determine whether a journal is reputable or not.

– THE MOST COMMON thing is that the journals use indicators in a non-scientific way and lie about how big an impact factor they have. Among other things, it is common for them to base their impact figures on Google Scholar or Index Copernicus, and not on the accepted impact factor from Incites. They also do not shy away from charging handsome fees from young researchers who depend on being published and receiving citations.

ACCORDING TO Eva Hessman, the biggest risk with publishing in these journals is appearing to be unprofessional.

– If you show poor judgement in your choice of publication channel, it seems likely that your judgement may be erroneous in

You have as much responsi bility for your choice of publica tion…

EVA HESSMAN

other contexts as well.

What the individual resear cher can do to counter predatory journals is to learn to identify them.

One warning sign is the esti mate of how long the fact-check ing process may take.

– THE SHORTER the time, the gre ater the cause for concern. One recommendation is to talk to your colleagues and investigate whether the journal in question

is available in one of the databa ses you use in your research.

– There are no easy answers. This is not a black-and-white issue. You have to form your own opinion and familiarize yourself with the subject, says Eva Hessman.

Text: Hanna Jedvik Allan ErikssonFACTS

20 minutes for researchers is a series of short presentations where the University Li brary provides advice on tools and services.

For more information visit: www.ub.gu.se/sv/tjans ter-och-stod/20-minu ter-for-forskare

The term "predatory jour nal" was coined in 2010 by Jeffrey Beall, libra rian at the University of Colorado in the USA. He published a list of open access journals that he judged to be predato ry journals. The list is no longer updated.

Illustration: David Parkins

Illustration: David Parkins

and melting ice

Ellesmere, Canada's northernmost island, in the summer of 2012. Anne Bjorkman is sleeping in a small cabin. Suddenly she wakes up to the sound of glass breaking. When she looks at the window, she sees the head of a polar bear peeking through.

We find Anne Bjorkman in the basement of the Bota ny Building, where she is sorting through the equipme nt that she and her colleagues brought with them on an expedition to Svalbard, one of three areas where her team has ongoing research projects. The equipment in cludes different measuring instruments and drills, but also packets of hair nets for various plants, for keeping out pollinating insects.

Her field of research is plant ecology, specifically how plants in the Arctic are affected by climate change. She has conducted research in the Arctic many times before, but this time the expedition ran into some problems.

– Some of our equipment was sent back and forth, and because of the SAS strike several colleagues almost didn’t manage to get there. However, Svalbard in the summer is fantastic as there is plenty of light both day and night. You can work as long as you like, and the nature is wonderful with all the birds, polar bears, and wild reindeer. But I was surprised at the disruption to the landscape, primarily due to intensive mining for coal in the mountains.

The other area where Anne Bjorkman's team conducts research is Latnjajaure, 20 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

The third research area is Greenland.

– My field season in Greenland was special, because that year my husband and eight-month-old son came with me. It is relatively easy doing research in Green land. Near the field station there is a small community with shops and other home comforts where you can also use your mobile phone.

Research on the Arctic is important, not least for

understanding climate change. Forty-two percent of the Earth's soil carbon is stored in the frozen tundra; if the tundra thaws, the consequences for global warming will be staggering.

– This is why it’s so worrying that temperatures are rising three times as fast in the Arctic, compared to the rest of the world.

And the high Arctic heats up particularly quickly. Every summer, scientists put out markers where the glacier ends, and each year the ice has retreated a little more.

Climate change leads, among other things, to mos ses declining while shrubs spread. It also leads to taller plants moving into the Arctic, explains Anne Bjorkman.

– Taller plants tend to trap snow, which acts like a blanket to keep the soil warm in the winter. Taller plants are also more likely to stick up above the surface of the snow, and their dark branches absorb more heat than the white snow. Both phenomena accelerate the warming effect. On the other hand, large leaves provide more shade in the summer, which has a cooling effect on the soil.

Climate change also results in plants that are adap ted to warmer climates starting to spread over larger areas. Although, that is not always the case.

– During my PhD work on Ellesmere Island, we did experiments using a number of open-top greenhouses that warm the air inside. We planted seeds from plants that were adapted to a warmer climate farther south, as well as seeds that belonged to the area's natural popu lation. The hypothesis was that in the greenhouses, the plants that were adapted to a warmer climate would outperform the plants that were naturally present in that location. But that turned out not to be true. On

the contrary, the local populations had both a higher survival rate and grew larger than the heat-adapted plants. The experiment thus shows that temperature is only one of many factors that affect how and where a plant thrives. Things like the composition of the soil, day length, and grazing pressure are also significant.

Anne Bjorkman grew up in Virginia, USA. She got her Swedish surname from her great-grandfather, who came from Jönköping. That she would study Biology was a given – nature has always interested her. However, as her interest included nearly everything related to the subject, it was not immediately obvious

exactly what she would focus on.

– I received my bachelor's degree from Cornell Uni versity and then I spent a few years doing field studies. For a while I was in Costa Rica studying capuchins, small monkeys with white faces. Later, I went to Pana ma to do research on manakins, a type of passerine. Eventually, I applied to a number of different universi ties but decided that the University of British Columbia in Vancouver suited me best. I was there for over six years and did my master's and PhD there.

Since then, Anne Bjorkman has worked as a post doctoral fellow in Leipzig, Edinburgh, Aarhus, and Frankfurt. She also studied in Russia for four months and learned to speak enough Russian to do field studies in Siberia. In 2019, she came to Gothenburg with her family, and at the same time received a five-year scho larship from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

– I enjoy the Scandinavian balance between work and leisure. I also prefer the Swedish system for exter nal grants, where more researchers receive a little less funding, than the American one, where a few research ers receive a lot. The Swedish view of doctoral students also appeals to me. Here, they are seen as colleagues who have four years to finish their thesis. And if they teach, they are compensated with additional research time. In Germany, doctoral students are considered to

be more like students, and the duration of study is only three years, regardless of teaching.

Research is interesting in itself – but of course field studies are particularly exciting. Anne Bjorkman's more strenuous adventures include five summers of field work on Ellesmere Island.

– It takes three hours to fly there, with special planes equipped with skis to land on the ice. Other research teams camp up there, but my team had access to a couple of cabins set up by the Canadian police in the 1950s. The cabins do not have running water, sewage or an internet connection, but they do have some solar panels so you can keep your laptop running and send short text messages by satellite phone. There were generally about five people in my team, and we became very close friends; indeed, they were my only contact with humanity for two and a half months.

To protect themselves from polar bears, expedition members in the Arctic always carry shotguns. However, they are initially loaded with a rubber bullet, and it is only in an extreme emergency that you would shoot using live rounds. In most instances, polar bears are scared away with "bear bangers" – a small cylinder with a firecracker in it that you launch into the air.

It was one of these bear bangers that Anne Bjork man grabbed when she was woken up one night by a polar bear trying to get inside her cabin.

– It had poked its head in through the window just a few metres from my bed, but it was obviously far too big to actually get through. I started banging on the wall as hard as I could to scare him off and to wake up my colleagues.

She yelled at her colleagues to grab the gun and went outside the cabin to fire a bear banger and scare the animal back towards the ice.

– It worked, but on his way past the cabin he saw me and stopped, just a few metres away. We stared at each other for a second. Then I tried to set off another banger, to keep him moving, but this one was a dud and didn’t fire. The only thing I had was the empty cartridge from the first banger, so I threw it at him, and then he ran off.

After a visit by a polar bear, it is very important to keep an eye out to make sure that it has really been scared off and does not come back.

So, the team stayed awake and scouted the area. In fact, an hour later the polar bear was on his way back to the cabin again.

– But this time we were all ready, and my colleagues and I came out shooting bear bangers and guns and making all kinds of noise. After that the polar bear left and didn’t come back.

Anne Bjorkman was never particularly afraid, though.

– I was standing right at the door and could have easily slipped back inside if the situation had become dangerous, so mostly I remember just being impressed by seeing such a large, powerful, and beautiful animal. So mostly it was a feeling of awe, though I admit it took a while before I stopped jumping at every loud noise.

It had poked its head in through the window just a few metres from my bed …

Anne Bjorkman

Works as: Senior lecturer at the Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences. A Wallenberg Academy Fellow, newly appointed Research Leader of the Future by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Background: Studies at Cornell University, PhD at Universi ty of British Columbia, post doc. in Germany, Denmark and Scotland.

Family: Husband, two sons, a dog and a cat.

Latest book: A historical detective story. When I have time to read for fun, I want it to be something as far from reality as possible.

Latest film: Monsters, Inc. (with my 4-year-old).

Favourite food: Vegetarian tacos and Boston Cream Pie.

Personal interests: Other than science? Nature, hiking, travel, piano, classical music, baking.

The war in words and pictures

– Unfortunately, the ways out of Mariupol are cut off and we are surrounded. I would come to Sweden with great pleasure, but as I said, no way out. But one day I will be the happiest person in the world to see all of you in person!

These words were written by Viktoriia on February 26 in Mes sages from Ukraine, a graphic novel with quotes from 13 young Ukrainians about the first weeks of the war.

Gregg Bucken-Knapp, Professor of Public Administration, had originally intended to put together a completely different book.

– Since 2018, I have arranged two two-week courses within the programme Swedish Institute Academy for Young Professionals (SAYP). The programme aims to support young officials working on migration and integration in the Baltic Sea area, in the Balkans and within the EU Eastern Partnership. A couple of years ago I had the idea of asking the course attendees to participate in a slight ly different book project. They were to write short personal vignettes about their work, which they would then reshape into a graphic story, working together with the editors and the illustrator. The work was already in progress when, on February 24, news reached us of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Among those involved in the book pro ject were several Ukrainians. Naturally, their colleagues at SAYP were concerned for their well-being. Gregg Bucken-Knapp emailed questions and offered to help,

in the form of support if they wanted to come to Sweden.

– Some of the Ukrainian attendees were in other countries, some were on the run, some had decided to stay and fight – whether in the civil defence or in the military was difficult to know. Of course, while we wanted to find out as much as possible about their situation, we did not want to bombard them with questions, when they were busy with their own situation.

Gregg Bucken-Knapp started to com pile a schematic of where the Ukrainian colleagues were and where they were headed. At the same time, their various messages stirred his imagination. How was Olga doing, who fled from Kyiv to Lviv with her little gerbil? How could they help Oleksii who sent a wish list of medical supplies? And will Mariia mana ge to get herself to Poland with her young son? Working with Joonas Sildre, Gregg Bucken-Knapp started to think about how all of this could be depicted in text and images.

– The book that we had already started on was temporarily set aside. Instead, we started working on Messages from Ukraine. While we really wanted to use the material that had been sent to us, the ethical aspect was important. Of course, in no way did we want to exploit these people, and were took care to ensure that everyone who participated really understood and accepted how the text and images would be used together.

Graphic novels and cartoons may be perceived as a frivolous way of presenting research on serious matters. But even though it is still unusual, the interest is growing for scientific findings where words and images are equal partners, Gregg Bucken-Knapp argues.

– The book is being published by

University of Toronto Press in their ethnoGRAPHIC series, which focuses on graphic cartoons, both as part of the research process itself as well as a way of engaging the public in a more accessible, open and aesthetically pleasing way. Interpreting other people’s interpretation of life is what we do as social scientists, and sometimes a picture can express a si tuation more effectively than any amount of words. For example, I think the final cartoon in Messages from Ukraine shows precisely what we all think of the war. It portrays a young girl with her fist clen ched looking up at a bomber, shouting: “Stop this!”

Facts

Since 2018, the School of Public Adminis tration has been arranging training modu les under the SYPE programme (Swedish Institute Academy for Young Professio nals), which are funded by the Swedish Institute. The Baltic Sea Region and the EU's Eastern Partnership module is held in conjunction with the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs in Tiblisi and the Western Balkans module is held in collaboration with The Integration Foundation of Estonia in Tallin.

The target audience is young officials, politicians and employees or volunteers within civil society, and the focus is on inte gration and migration. The School of Public Administration was first granted 3.2 million SEK up until 2022. Following the invasion of Ukraine, an additional 145,000 SEK was provided in order to be able to accept more Ukrainian attendees.

The book, Messages from Ukraine, is the result of a partnership between Gregg Bucken-Knapp and the Estonian illustra tor Joonas Sildre. The publisher is Univer sity of Toronto Press and the book is part of their ethnoGRAPHIC series. All revenue from sales of the book will be donated to the Canada-Ukraine Foundation.

Text: Eva Lundgren Photo: Johan Wingborg

Text: Eva Lundgren Photo: Johan Wingborg

While we really wanted to use the material that had been sent to us, the ethical aspect was important.

GREGG BUCKEN-KNAPP

Bike demonstration against threatened research

“Back in the day, people helped one another and you could feel safe when walking the streets.”

Doctoral student Luca Verste egen calls it nostalgic thinking – an important motive for more and more people voting for populist far-right parties.

– Currently, research in this growing right-wing extremist environment is threatened, not least since Russia invaded Ukraine, he says.

Luca Versteegen has just completed a 1,500 kilometre bike ride from Budapest in Hungary to Athens in Greece. From a city where the extreme right is in power, to a city where democracy took its first tentative steps several thousand years ago. Once in Athens, he participated in a conference on political psychology, which is Luca Versteegen's field of resear ch at the department of political science in Gothenburg. His doctoral thesis deals with the socio-psychological reasons for the tremendous success of the extreme right in the last 10–20 years.

Through his bike ride, he managed to collect 18,000 SEK – for the Scholars at

Risk network. The money goes directly to support researchers who can no longer carry out their research freely. He men tions a Hungarian researcher who was forced to move to Italy for conducting re search on the Hungarian government. He also talks about a Turkish colleague who wanted to study the situation of sexual minorities in the country. He was black listed with the comment: you will not receive research funds if you continue with this. In Ukraine, many universities have been damaged in the fighting and researchers have been forced to flee.

– Being able to participate in a resear ch conference where ideas and also opi nions can be freely exchanged without the risk of reprisal is not a natural state of affairs to everyone in the world. Unfor tunately, the authoritarian development in Hungary, Poland, Russia and Turkey has meant restrictions on the freedom to investigate pressing social issues in these countries, states Luca Versteegen.

The populist parties differentiate between normal, ordinary people and politicians, who are considered corrupt and mostly interested in helping them selves. The ordinary people are also superior to the foreigners.

The financial crisis of 2008 and the

Luca Versteegen comes from Hamburg and is a doctoral student at the department of political science.

I also believe that an individual’s ability to handle challenges is crucial for determining how they vote.

LUCA

refugee crisis of 2015 are considered to have given a real boost to far-right parties in many countries. They are sometimes seen as putting much-needed pressure on the other parties, but they also pose a threat to democracy as they question the democratic system. They also attack ethnic and religious groups, or sexual minorities who are not considered to be part of the people.

Common explanations for people voting for far-right parties tend to be financial and cultural: weak links to the labour market, that one either does not have a job or is in low-paid employment, and that one lives in an area with a lot of immigrants.

– They have received some scientific support.

But I am interested in how two people with the same social circumstances can vote so differently: one for an established party like the Social Democrats, and the other for an extreme right-wing party.

More and more researchers in the field are now saying that the subjective experience of social developments can be more decisive than the objective condi tions. The perceived social structure may, for example, be more important than the number of migrants in a residential area.

Luca Versteegen analyses large amounts of representative data from the Netherlands. They show that people who are nostalgic about how society and people used to be tend to vote for the far right. They feel disadvantaged and unhappy and find answers in populism. People who are instead nostalgic for per sonal things like music or family holidays tend to vote for the traditional parties, probably because they are happy with their memories.

In the qualitative interviews with 30 right-wing, populist German voters, he decided to pose an open question: How do you experience your social, political and cultural situation now compared to 30 years ago? Many respondents stated that they felt safer and were more trus ting of other people in the past.

But in East Germany, it was hardly safer in the past with neighbours who could be informants and the constant surveillance, Luca Versteegen argues.

– These are what I call nostalgic depic tions of the past that can explain why far-right parties, which present the same nostalgic narratives, are successful.

The interviews also show that some people do not feel appreciated as men and white.

– They say, for example, that quotas mean that men are discriminated against. They are bothered by new gender-neutral words or any words that even refer to women. They think the immigrants have taken over. They belong to the majority society, but they still feel excluded.

Many consider themselves disadvanta ged by society.

– In East Germany, which we have studied, they have had bad experiences with the government. The degree of trust in politicians, and trust in people in gene ral, seems to matter.

Many people talk about the pandemic, the refugee crisis and global warming. There are too many things going on at the same time, people feel overwhelmed.

– I also believe that an individual’s ability to handle challenges is crucial for determining how they vote.

Facts

– Large numbers of researchers and stu dents have been forced to flee after Rus sia's invasion of Ukraine, but only women have been allowed to leave the country. Most of them remain in Ukraine and strugg le to continue their work despite the dang ers. Many are also taking part in the war. A number of universities have been damaged or destroyed, research infrastructure has been damaged, including scientific equip ment and laboratories. Many higher educa tion institutions have been relocated.

– Scienceforukraine.eu is a grassroots movement with volunteer researchers and students from many countries, who, through contacts with funders and policy makers, are working to support Ukrainian researchers and students who have been affected by Russia's invasion of Ukraine. It disseminates information on social chan nels about how to help Ukrainian acade mics, maintains a database of the assis tance and collaborates with organisations, governments and the scientific commu nity.

Above all, countries in Eastern Europe have welcomed Ukrainian researchers, students and their families. Donations from various European institutions, governments and the EU have been an important means of support for Ukraine.

Something in the system must be sick, seems to be a conclusion that gives support to the far right and its simplis tic explanations, where immigration is singled out as the main problem. Another nostalgic narrative that re-emerges is that society was more homogenous before, which may be true. But the conclusion that a party on the far right can solve the challenges of the future needs to be explained.

– I believe that the solution to redu cing polarization in society is education. The segregation that is widespread in Gothenburg, for example, is not good either. In Landala, where I live, it is very white. It is better to have a mix of people.

Luca Versteegen points out that he has some way to go before he can draw cer tain conclusions. He says selection can matter. The 30 people he had the oppor tunity to interview were all politically en gaged and more experienced rhetorically than other voters. The far-right parties in Sweden and France have undergone a "detoxification" in order to increase their voter support. But in Hungary, where Luca started his bike tour, and in Germany, where he interviewed far-right supporters, the radical right-wing parties have become even more extreme.

– Some we interviewed expressed a very racist ideology. I cycled from Budapest, Hungary to Athens, Greece, raising money to make people aware that research into this growing far-right environment is now under threat.

Text: Peter Olofsson

Photo: Peter Olofsson and Kristina Wagner

Text: Peter Olofsson

Photo: Peter Olofsson and Kristina Wagner

Does your computer write better than you?

GPT-3 is a digital service that produces text that appears to be written by a human. The service is free of charge, easy to use and available to anyone.

– Technology is one of seve ral reasons why homework has become more problematic as a basis for academic assess ment in schools. But above all, these kinds of transformative technologies force us to reflect on why skills such as writing are important, says Erik Winerö, upper-secondary school teacher and doctoral student in applied IT.

The database from which GPT-3 retrieves information is gigantic, among other things it contains all the Wikipedia pages up until 2019. There is also other material, such as published works by Tomas Tranströmer. This means, for ex ample, that you can ask the programme to write a poem about public transport in Gothenburg in the style of Tranströmer. Not satisfied? Then be more specific and try again. The programme constantly produces new material and does not

copy existing text; systems that check for plagiarism such as Original (formerly “Urkund”) are therefore of no use here, Erik Winerö tells us.

– My impression is that a lot of people underestimate technology. They don’t believe that GPT-3 works very well, but when you experience it in real time, they are often quite taken aback. Further more, if we consider the fact that GPT-3 soon will be superseded by the next generation, GPT-4, which is estimated to be more than 500 times as powerful, we realise that we are facing a truly transfor mative technology. The consequences for schools are numerous. Above all, GPT-3 makes it problematic to use written as signments done as homework as a basis for examination. Of course such assign ments were always problematic. Not only do they encourage cheating, but are also unfair, as pupils have such different home environments; some have access to a well-equipped home office while others share a small room with their siblings.

But GPT-3 does highlight a considerably bigger issue than the possibility of chea ting: why should we continue to struggle with writing exercises when we have computer software that can produce text that is just as good as our own? One

answer can be found in the work of Alex ander Luria, Erik Winerö explains.

– Luria was a Soviet researcher who in the 1920s and 1930s conducted experi ments that are unlikely to be repeated. The basis was the massive educational initiative that was implemented in the newly formed Soviet Union where the rural population – largely illiterate –would learn to read and write. For a time, this led to there being large groups of people that were comparable in terms of living conditions, but who differed by the fact that some were literate while others were not.

What Alexander Luria investigated was the way in which a written language affected people’s way of thinking. For ex ample, what about logical reasoning, such as: Precious metals cannot corrode. Gold is a precious metal. Can gold corrode?

– Those who had learned to read had no problem giving the correct answer, while those who could not read answered based on their own experience instead: I don’t own any gold, how should I know whether gold corrodes? What Luria showed was that something happens to us when we become literate: Not only does it enable us to acquire and pass on infor mation more easily – learning to read and

you?

Erik Winerö says that people often underestimate digital technology.

or paste text from other sources. Most schools have such systems, but as a rule they are only used for final examinations. But Erik Winerö argues that they could be used in other instances as well.

– It is important that a test has good validity, that it measures the right thing. If the pupils are not used to the digital systems, the validity will deteriorate. One way of improving the situation is therefore to use the systems frequently, also for assignments that are not for final examinations. Because pupils do not need more tests, they need fewer. The previous curriculum contained a paragraph about teachers, when grading, considering everything they know about the pupil; this was interpreted by many to mean that they must assess everything the pupil does. And if this is communicated to the pupils, there is a risk that they will believe that they are not allowed to fail, which is one reason why Swedish pupils are suffering from growing stress. And yet it is precisely like Yoda pointed out in Star Wars: “the greatest teacher, failure is.”

In order to reduce stress and encoura ge the pupils’ creativity, the teachers must be careful to distinguish between the activities that will be assessed and those that will not.

Because permissive learning environ ments, where pupils feel safe to fail, is crucial to a good education. An insight that is sometimes counteracted by the school system, says Erik Winerö.

– A computer generated text can constitute an interesting starting point for discussions, such as about why a text is good or bad, and about what the text might have been like had I written it myself. Also, GPT-3 can be quite fun, and might inspire people to write themselves.

Naturally, digital technology will have an impact on much more in our future society than the ability to produce text, Erik Winerö points out.

– Digital technology will replace almost all of the labour that most of us make a living from now. As, we to a great extent today identify ourselves with our work, that future perspective may appear frightening. But having a particular pro fession is something that is a fairly recent phenomenon. We can spend our time on other things, such as trying to become good democratic citizens. We can also spend time on artistic endeavours and perhaps take pleasure in the enjoyment and self-realisation that writing can provi de – regardless of how many good digital programmes are being developed.

Text: Eva Lundgren Photo: Johan WingborgExamples

By entering: “Write a poem in the style of Tranströmer about AI-based text, cheating and Swedish schools”

write enables us to learn to think.

So we must not lose sight of writing, Erik Winerö points out.

– The upper-secondary school curri culum in Swedish has been increasingly focusing on different types of text and analysis of them, such as op-ed articles, abstracts and scientific memos. All of these are types of text that GPT-3 produ ces relatively well. One way of managing the risk of pupils using AI to generate text will be to focus more on the writing process itself. But of course it is more demanding to follow the processes of a large number of pupils rather than asses sing written text using a matrix. This is an example of our having to move away from so-called “product pedagogy,” but that requires time and resources.

Another way of ensuring that pupils do not cheat is to let them write in digital test systems that lock the writing surface. This means that pupils cannot use Google

– Even though assessment is a crucial part of school life, up until 2011 assess ment and test construction was not a mandatory part of Swedish teacher trai ning education. One explanation could be the dominant views of knowledge, in which memory and facts are disparaged as measurements of knowledge. Interpre tations of the theories of, for example, Piaget, Vygotsky and Dewey may lead to the notion that it is only when you do something practical that knowledge be comes visible. With that mindset, classic tests become less relevant. Furthermore, sometimes you come across the view that since we can google for facts, we do not need to remember them to the same extent as we used to. The problem is that that is not the way our brain operates. For example, in order to be able to think critically, we need access to information in our long-term memory. A mobile pho ne cannot replace that.

So, should digital programmes, such as GPT-3, be completely banned? No, Erik Winerö argues.

GPT-3 produced the following text: When we’re cheating in our writing we take the shorter path when we make our way

It is easier and takes less time and we don’t need thinking

but it is never truthful cause we’re lying

And cheating will forever remain in place

As a shadow on our learning

A memory of the shortcut that we once took

When we cheated in our writing.

… Learning to read and write enables us to learn to think. ERIK WINERÖ

The Moment

Where? Who, When?

• The amphitheatre at Humanisten.

• Agnes Eriksson and Philip Ahlgren.

• Saturday June 18.

In short

One afternoon in mid-June, Humanisten was transformed into something very special: the open light amphitheatre became a wedding venue for Agnes Eriksson and Philip Ahlgren.

– We both work in the construction in dustry and are interested in architecture and therefore wanted to get married in a venue that is special in some way. We se arched for a long time before we eventually got tips about the Humanisten. And the amphitheater is really beautiful with

its large, open staircase! The acoustics are good, the woodwork contains fine details and the artist Meriç Algün, who is responsible for the decoration, has used recycled materials. It is simply a room for joy.

Neither Agnes nor Philip have been students at Humanisten or have any other connection to the building.

– No, we chose the venue only becau se it is so beautiful. After the ceremony, we had a reception in Villa Johanneberg right next to Näckrosdammen, which of course was also practical. The number of guests at the wedding was just over 50, the officiant was Marianne Carlström and the wedding trip went to Portugal, the French Riviera and Corsica.

Foto: JOHAN