Volume 15 | Issue 1 | Spring 2022

Volume 15 | Issue 1 | Spring 2022

Dear reader,

To An Unknown God seeks to engage thoughtfully with both Christian and non-Christian readers with topics that spark meaningful conversation. This semester, we gathered poetry, prose, and artwork all produced by TAUG and its friends for this purpose. Our theme this semester is Wonder

As I reflect on the past two years as editor of this journal, I consider what I appreciate most about its composition. Beautiful artwork, compelling storytelling, and sincere reflection are some consistent ingredients of the journal that come to mind. These take stage in this semester’s print through childhood reminiscence, ponderings about one’s place in the universe, and contemplations of beauty in the midst of brokenness.

As you read through this issue, celebrate the effort spent creating a beautiful thing such as this, even with all its imperfections. Perhaps, TAUG can help you glimpse the wonder of our world and our good Creator.

Unknowingly,

Benjamin Chow

Editor-in-Chief

Benjamin Chow

Executive Editor

Justin Fung

Executive Designer

Patricia Tse

Business Manager

Dorcas Cheung

Associate Designers

Claire Oh

Phoebe Chen

Reba Sy

Sara Helalian

William Webster

Associate Editors

Christy Koh

Corina Chen

Christine Youn

Grace Lee

Ian Buchanan

Business

Phoebe Chen

To An Unknown God is not affiliated with any church or any religious group. Opinions expressed in articles do not necessarily represent those of the editors. We are completely student-run and funded partly by the student body as an ASUC-sponsored student publication. Funding is also provided through individual donations. Distribution is free while supplies last. To contact us, please email us at taug@berkeley.edu. Visit us at toanunknowngod.weebly.com/.

“Therefore, the One whom you worship without knowing, Him I proclaim to you.”

–– Acts 17:23*Not photographed: Justin Fung, Dorcas Cheung, Sara Helalian, William Webster, Corina Chen, Grace Lee

Words: Ian Buchanan

Not quite like a child asking, She observes, The words that apprehend the thought Too calmly reasoned, too full of the learning of them.

(Referring to the cautious pupil) I’ve interrogated many in that loving way: Phone, Furnace, Cloud, Lake, Coral, Serpent, Frost, Sandal, Page, Road, Wordsworth, Day, Washington, Fear, Number, Soul — The soul becomes small almost without effort, But full, and overfull.

It’s a very easy thing to have stumbled, She relates, To have decorated oneself in tight brown stripes of skin. And the eye insists on exposing the interior In cross-hatches of red and never blue, which surprises

Once I was younger and the prince of oceans, Before the revelation of the night And its pale prioress, And the voice of the mother queen imperfect Compels, as though by centrifuge, Adoption of a colder age — Though bright, and very bright.

How to escape that arresting spirit That so perverts the eyes — Surgery, Cello, Costume, Father, Carpet, Glass, Dying? How excellent to multiply the forms And not assume. To leave unincorporated Bodies not belonging to oneself.

If anything attaining, Necessarily the innocent question: Life, Death, Body, Soul?

Ian is a fourth-year English major who only jaywalks when absolutely necessary, though not without exceptions.

I’mpretty sure there are two kinds of wonder. The first, I wonder if, how, why. The wonder that comes with a question. Second, I wonder at, in, with. The kind of wonder that marvels.

I wonder all the time.

When I was younger, I was full of questions about the end of the world, forgiveness, doubt. Don’t think I was some philosophical bundt—I was simply a worrier. I couldn’t let go of my concern that if I messed up, any hope I might get through God would disappear. My dad would hold me in my wonderings, treating each worry and anxiety with gentleness and wisdom.

As I reached middle and high school, I wondered if any boy would ever like me and now that I’m older I wonder why boys think they can walk over any girl they want. Now I wonder at the way people manage to wear outfits to school every single day, when I struggle to keep a pair of jeans on for longer than the duration of a lecture—started on Berkeley time too. I wonder how California’s sky is so blue yet greys so suddenly and I wonder how come the sunset is always prettier in San Diego than San Jose. I wonder if my definition of wealth will change the more I acquire, and worry that it will give me aspirations to join the 1-percent.

When I observe the city moving around me, I think she wonders too. Berkeley is constantly wondering why her streets hold so much brokenness while Oakland wonders why we can’t seem to fight inequality. My school wonders if it can house all its students—sparking dozens of debates, articles, and protests—and students wonder why they can’t be heard.

Wondering demands a certain level of not knowing. Louis Armstrong wondered at the world he lived in while Shawn Mendes wonders what it’s like to be loved by the girl he pines after. Stevie Wonder was born wondering (and not just cause he couldn’t see anything). R. J. Palacio wrote her middle-grade novel Wonder, calling us to try and wonder at the uniqueness of a single human being. And yet because wondering takes this uncertainty, this curiosity, I think too often wonder is put on a shelf. We can wonder another day. For now, we have back to back meetings on Zoom and judgment to dole out on people who think differently than us. We’ve got online shopping to do, fancy restaurants to dissect, and today’s newest word game to try.

There’s another kind of wonder though. My mama taught me how to wonder through marveling. Have you ever marveled? I used to impatiently speed walk when we went wandering through our neighborhood together. She still is always pausing to admire a front yard, reaching out a hand to pick a tempting orange. (My family always wonders at the way

she exhibits such an Eve-of-Genesis tendency to pick what isn’t hers.) We’d meander through a museum, reading every plaque and drawing the paintings we saw in art journals. For my sisters and I, art crafts, and writing assignments were in great abundance under our mom’s direction. Museums, hikes, traveling, baking, decorating at holidays: whatever door was open, my mom walked through to show us another way to wonder.

For several summers in high school, my family traveled to Europe, enjoying the privilege of tagging along on my dad’s work trips. In London, my mom took our family to Regent’s Park, Hyde

Words and Photos

CORINA CHENBy example she taught us how to appreciate other cultures, the loveliness of a different sea, or the calmness found blooming by the side of the road. She does this over and over again no matter where we are, and in doing so reminds me what it’s like to be in awe of the little and the big of the world.

Wondering takes time. Admiring a sunset while driving is different than pulling off to the side of the road and bathing in every color’s slow release. Having the chance to wonder, I’ve realized, is a slow gift. Entertaining questions or letting awe wash over you takes time we often aren’t ready to relinquish. I worry that we are becoming a fast paced society with no bandwidth for wonder. Being able to ask, “I wonder why the sunrise is pink at dawn and red at dusk” is more than physics saying red wavelengths have the longest reach—it’s saying I’m taking the time to hold the beginning and end of a day in all its beauty.

And so to wonder takes patience and humility. The ability to slow down, calm down, notice the little surpass that happen on the walk to class. It might mean admiring a building usually rushed by everyday, or arching your gaze up to see if you can see where the redwood’s headed.

Park, and Kensington Gardens. Each park featured sprawling lawns and large, fragrant roses. Couples lounged on the grass or walked winding paths. My romantically-oriented mind was immediately swept up in the soft glory of the scene. As we snacked and moved through the gardens, my mom remarked upon the picnicking, peaceful culture of the parks. Or, when we went to Greece and Italy, my mom sighed at the freshness of the food and the temperate climate of the coast, encouraging us to wonder at the differences between there and here.

After each act of creation, God looked at it and called it good. In doing so, he was finding wonder in his world. As I walk though his marvelous world, I like to pick the flowers. My friends are always teasing me that I pick flowers along city streets with zero guilt. This is true. Perhaps I should absolve my mom of her own fruit-picking guilt. More so, however, looking for the next pink or yellow bloom is my way of continuing to wonder at the way creation forces her way through cement blocks of grime and brokenness.

Corina is a third-year double major in English and Linguistics who gets a thrill every time the sun comes out. When not writing, she is working out, snacking, or exploring.

After each act of creation, God looked at it and called it good. In doing so, he was finding wonder in his world.

How did you join my somber parade?

My shadow could not cling to me so tight. How can you hunt me still and yet not be evaded?

Who taught you to reject the light, but still, Who bound and chained your soul with mine in which past decade?

Every step I have taken to outrun you has led me with all the force of nature’s psychological gravity back to you.

Which scalpel will be used to undo myself from you?

And shall I face its hilt or blade; is this follow through, give into?

You are with me at the twilight of my being and at the dusk of my daily terrors. You knelt beside every wet and bloody bedside and cooled every nightmare from the raptures of horror and every daydream of the sun’s breathless kiss.

You are no friend of mine but you are a soulmate yet.

Let our bonds be tender, made of flesh and sinew, Joined and defined by covenant of blood renewed.

You have no power, no claim over me, but you shall be seated at my table and attend my council.

Draw from me every joy and every sorrow - round them like a pottery of synaptic dough in your hands.

For you shall not have my life and you will find some joys that you cannot shape without a forceful destruction and, yet, I know you are not an aberration of bone and hammer, but of tears and sighs.

So let your influence over me be that: tears to wash and heal and sighs to breathe and feel.

Companion Two, How do you follow me as you do? Is this follow, pass through? Do you lead, thank you?

You are constant wherever you emanate from.

You are as solid as hurricane winds and as tangible as snowfall to the hypothermic. But you are constant in your heavy lightness - I sense your burden yet the burden is not mine.

You are constantly on my mind yet rarely near my heart.

This is not love or friendship, This is surgery and absence.

I feel you, the shape of you, you are the hole - the ravine edges that my fingertips discover every occasion that I take my heart in blind examination into my hands.

How can you act so crushing? How could you be so stunting?

So gracefully malleable to my touch and so stalwartly constant against my fists? You are an encompassing perception, every day that I have ever known, and you are here?

When has your heart protected mine?

When did I earn this right divine?

When was I adopted to your nameWas I a toddler, a baby, or an unspoken aim?

You taught that petulant toddler peace but she learned only quiet and you saved that smiling, plaid-clothed girlFor where are her pink, purple, blue bruises?

You let them tell her ‘Your birthright is sin, Your family admonished herein.’ But I heard you shout in a whisper I still hear: “Love wins.”

You saved that grinning, pride-clothed girlFor where are her pink, purple, blue bruises? They striped themselves on the banner of the sunset. Now dawn is nigh.

I have never been loved - never held in safety - and never grew. I have always been your daughter and I have never been loved. I have never felt you hold my hand and I have climbed mountains. You have never made a footprint beside me and I have conquered forests. Your reflection is only sky in the tumbling rivers I have longed to drown in. And you are to me as the sea- I never touch or feel it and it is the most powerful force I know.

I have never been loved. For I am love’s daughterI have never been loved in the collision of myself and a loving one for I am steeped in love as air and water, as milk and honey.

I have never been loved because you are love and I am nothing. I have never loved as I feel loved now.

Anya is a third-year Sociology and Economics double major minoring in City Planning who intends to dedicate her days to San Francisco and its people.

Words: Grace Lee

You remind me now

How Hope makes the heart fragile!

Remember!

I didn’t want to be afraid of the future

I wanted the opposite (The opposite?)

I wanted to be excited

For it with anticipation

In my face and hands

But what about tomorrow?

Remember!

That was when my heart ached With longing With terror

Deprived of sense

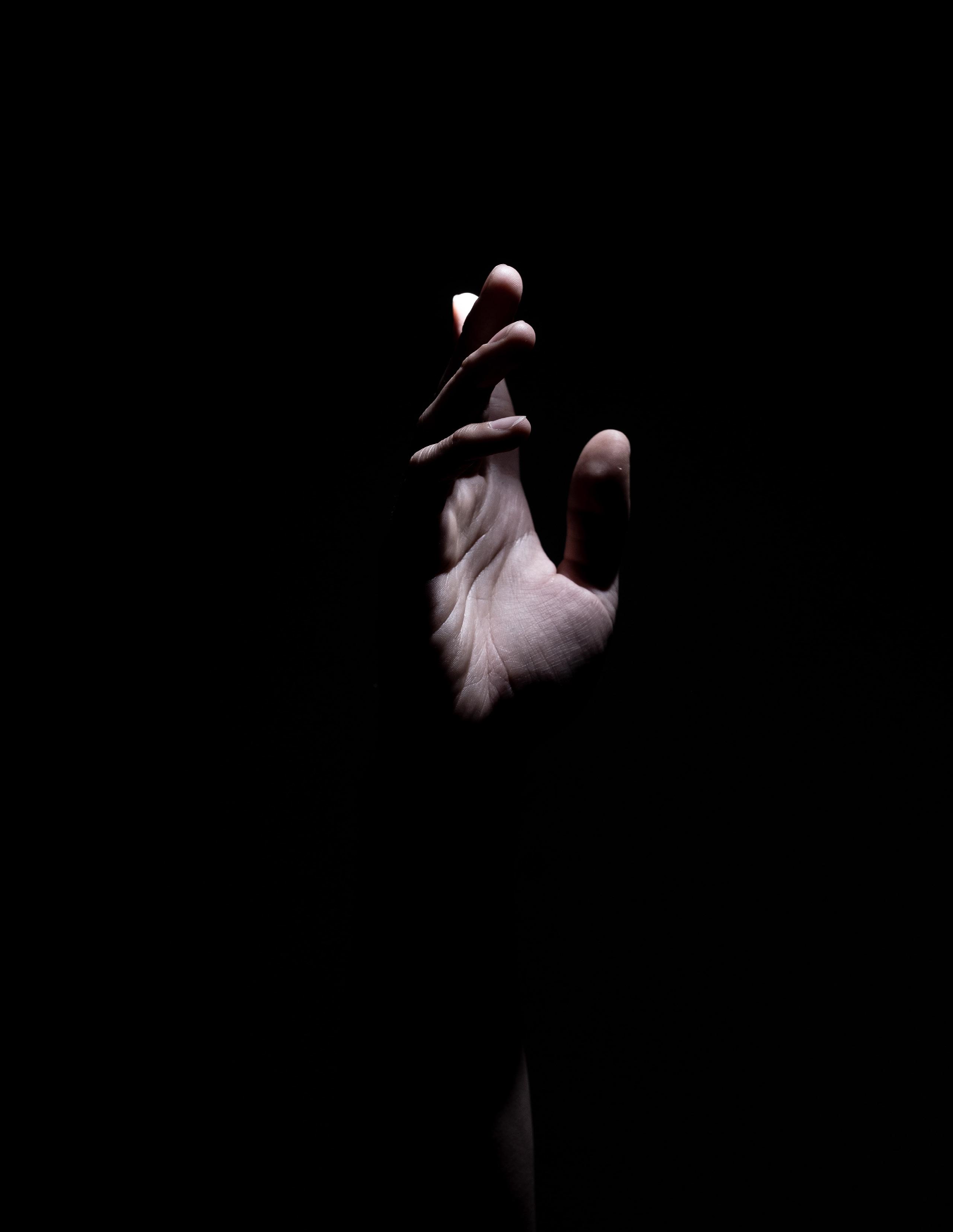

But I still reached my hands out Crying

I want to be excited about it!

My voice roaring

When the drums pounded, the cymbals crashed, the guitar rang, the voices soared up toward the ceiling, they filled the room

We filled the room

I remember!

Confessing was trusting

I stood with palms up

Thinking I was ready to give (To give?)

But now I know

As my fingers tremble to unfurl

I stand with hands up

Waiting

Because You cleared my path then

And now

As I confess my unbelief

You dare make me remember!

Your laughter roaring

You dare me

With eyes wild

Fierce smile

To wonder!

Grace is a fourth-year English major and Education minor who loves to write poetry and prose, sing, read, dance, and have deep, honest conversations with friends about God and His ongoing work and blessings in their lives.

Hail, holy Light, offspring of Heav’n, first-born, Or of th’ Eternal co-eternal beam May I express thee unblamed?

- John Milton, Paradise LostRecently, I have developed a new style of doodling. Lacking any knack for conventional artistry, I have instead circled-in on a sort of linguistic portraiture, created by stacking each consecutive word of an arbitrary phrase onto the first, until inevitably they all accumulate into an incomprehensible smudge.

I like to begin this process with a random but roomy base — a “what,” or a “because,” or a “maybe,” occasionally substituting conceptual width for physical. From here, I’ll source successive words or phrases from a song, a novel, or a conversation which I overheard that day and tucked away in my pocket for just such an occasion. For all my effort in building, the words never transcend the flat plane of the page, and in overlapping only ever end in the aforementioned smudge on the margin of my notes. Still, at the right angle and in the right lighting, you can just barely make out fragments of the original text — the sharp bridge of an “H,” or the pronounced curvature of an “R.” The more you look, the more, too, the letters begin to merge, forming complex amalgamations alien to any recorded language. The sweeping underhand of a “y” joins with the left-leaning center of an “m,” and an “o” swallows the anterior “s,” suggesting some new expression just beyond contemporary understanding.

A similar effect can be produced on a grander scale by pressing several pages of a book up to a window. Provided the paper is sufficiently thin, and the sun sufficiently bright, you might encounter in a single square a cosmic clash of scenes and settings, with peace and war depicted simultaneously and inversely, one reading leftto-right and the other right-to-left. Through a process of trial and error, you might manage to incorporate as many as five or more pages, front and back, though this requires no small forethought. Few texts are better suited toward this end than the Bible, whose delicate leaves allow Abraham, Isaac, Israel, and Joseph all to occupy the same literary landscape with little difficulty. Still, with the addition of more and denser pages, even these figures grow too dense for me to distinguish in fullness, and certainly exceed my capacity to trace — tracing being the original use of this window-trick when I was in elementary school.

My professors often focus, in our studies of the great authors and poets across history, on the fact of repetition. Each artist within their own corpus develops certain habits, either formal or thematic, from which they cannot, or will not, escape. Their successors, in turn, take up these same forms, these same themes, spurred on by awe and intrigue, and almost imperceptibly the private obsessions of an author become the public questions of a generation, of a culture, of an era. Onto the first work, a second is laid, and then a third, a fourth, a fifth — and out of this infinite layering, infinite variations emerge of the same initial question. By this, the thought is made to grow in complexity, if not clarity, extending out to every sphere of human experience, lest in idling it should fail to capture even a single wayward speck of honest insight. Emerson’s eye becomes Melville’s whale, becomes Whitman’s calamus, becomes Dickinson’s cathedral tunes, and there is beauty in the careful compilation of each word along the chain, meaning in the mysterious communion of grass and fish and concert.

I find a like but lesser pleasure every time I add another word to my phrase-towers. Though in effect I have only multiplied the lead stain, nevertheless I cannot help but feel that, provided the words are sufficiently striking, and the eye sufficiently illumined, there will always be another novel form to find in the adding.

The Kindly Ones (Gr. Eumenides) live under the Earth. They are “monstrous creatures dressed in black with snakelike hair,” like “dogs that run behind a wounded hare.” They execute justice, but they have no regard for courts, juries, or judges; because their justice is older than the justice of the books. Rather, they enforce more basic laws of kin, country, and hospitality. Whoever kills, the Kindly Ones will kill. Whoever turns away, the Kindly Ones will turn away. It’s strange, then, that they are called Kindly Ones in Aeschylus’s Oresteia trilogy, and actually, they don’t have that title until Athena assigns it at the very end of Eumenides (more on that later). Throughout Agamemnon, Libation Bearers, and most of Eumenides, they are known as Furies (Gr. Erinyes). They have smelled spilled blood, and lust for revenge.

The trilogy begins with the homecoming of Agamemnon, king of Argos, who in the heat of the Trojan war gagged and slaughtered his daughter Iphigenia in order to secure a military victory. Clytemnestra, his wife, is understandably incensed and avenges Iphigenia’s death when we hear screams of pain from backstage (the Greeks preferred to keep death discreet). Agamemnon and his prisoner of war are dead, and justice, it appears, has been served, “the plunderer plundered, the killer paying in full.” Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus reign as queen and king, and there is peace for our time.

In the second play, Orestes, Agamemnon and Clytemnestra’s son, meets with his sister Electra to pour libations upon his father’s grave. “Who, after all, can ransom blood poured on the ground?” I’d like to believe he understands that ultimately no one can, but Orestes and Electra will try. They conspire to masquerade as worn travelers at Clytemnestra’s house pleading for hospitality—a sacred supplication invoking bedrock Greek civic virtue. Clytemnestra cannot refuse, and after some discussion, she and Aegisthus die at her son’s hand.

This is the will of the Furies. “The trickles of blood / let onto the ground demand more, / more blood.” Orestes has satisfied the Furies’ longing for justice, to collect a debt against the house of Argos. Are you keeping score? It seems to me there is a problem: death and death do not add to zero. In the economy of blood there can be no double-entry bookkeeping, in which debits to one account are balanced by credits to another. There is only debit.

Every death in our story has been avenged by two. Clearly, we cannot keep going like this, and the whole crew at Argos is tired. “Where at last will this fierce havoc find something / to lull it to sleep, to end it?”

The Environmental Protection Agency values a human life at roughly ten million dollars. Cheaper than two lives, yes, but an inhumanity. You can’t number any human life in dollars, and that we need to do so in order to keep the human environment healthy is an embarrassment of arithmetic: a necessary one, perhaps, but an embarrassment nevertheless. On the other hand, in the 2022 Ukraine conflict, Russian soldiers were offered amnesty and $50,000 to surrender. This deal would price surrender as a substitute good for death or imprisonment. In our time there is a two-hundredfold spread between the price of death by organic lead and the price of death by metallic lead. There is no liquid market for blood.

Not only whole lives: all things that are essentially human essentially resist accounting. In his seminal “The Case for Reparations,”1 Ta-Nehisi Coates proposes a case-by-case reckoning of the plundering of black ancestries by white-owned institutions such as police departments and banks. He points to Germany’s postwar payment to Israel as proof-of-concept, and in a case study on housing in Chicago, calculates damages on the order of thousands of dollars per household. The accounting is tedious and fraught with imprecision, he acknowledges, though not necessarily hopelessly so.

1 https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

Words: Simon Kuang

Simon (‘16) is a TAUG alumnus currently working on a PhD in Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at UC Davis.

Financial mathematics demonstrates that if I steal your money, I can repay it with interest, and the accounting equation balances. But reflecting on Coates’s essay seven years later, Jesse McCarthy in Who Will Pay Reparations on My Soul? finds it morally untenable to appraise one’s ancestry in dollars. Sure, there must be an accurate valuation in theory, he explains, but any amount, no matter how large, dehumanizes a thing that is essentially human: to do so is a moral contradiction with one’s own being.

I once walked past a sign advertising “resources for historically underserved students.” It struck me as somehow right if you take a collective or corporate account of human family and faction. But prima facie it doesn’t make sense, because no student, no matter how underserved during their twenty-something years of life on Earth, is historically underserved. To allocate so much ontological weight to history is at loggerheads with the fundamental assumption that makes liberal democracy Liberal: I, human, am mainly a product of my own choice, much more than my “history.” As a consequence our country—rightly, in my view—renders clemency to children whose parents commit crimes at the border, yet themselves have done no wrong. I see no answer or system, only an unfolding of endless complications under this question.

And the discussion of money—that is only the easy part. Coates leaves as an open question the “moral debt” between descendants of slaves and descendants of slaveholders. This question is taken up in Jesse McCarthy’s book and interviews. McCarthy highlights an initially-$102 million compensation fund payable to the Sioux nation for the United States’s 1877 violation of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. The Sioux refuse the payment to this day, and it has appreciated to $1.3 billion.2 To accept the payment would constitute an unacceptable retroactive sale of sacred earth. They demand its return.

My examples show that in the large-scale moral ledger, balances only grow. In general, we cannot hope that they will be paid to satisfaction. At best they are eroded by forgetfulness.

In the third and final play of Oresteia, we have asked to speak to the manager(s): Apollo and Athena confront the Ghost of Clytemnestra and a chorus of Furies, who are at their exercise again after the last play’s matricide. As a sign of progress from violence to statehood, Athena holds a trial for Orestes with a jury of Athenian men. The plaintiffs accuse, Orestes gives a lame excuse citing determinism, there is a gripping cross-examination, and the jury votes. Although Athena casts the tie-breaking vote in favor of acquitting Orestes, she picks a technical nit, a prejudicial loophole: “There is no mother who gave birth to me. / With all my heart, I hold to what is male.”

More keen on a verdict’s political usefulness than on its jurisprudence, Athena has probably not regarded the arguments at all, and the courtroom chaos that ensues is resonant with modern and not-so-modern legacies of justice subverted on insubstantial, procedural grounds. But she soothes the Furies with a speech that praises their ethical understanding and offers them seats of honor as the divine police of Athens, provided that they don’t devolve to the old pre-legal ways. Suddenly they are converted, and dance with joy and vow to bless the wombs and fields of Athens. Athena toasts the spectacle as a triumph of Persuasion’s power to inaugurate an age of civic cooperation among men. A most charitable interpretation is that we have witnessed the power of forgetfulness, in the very best sense of forgive-and-forget. (Seen more cynically, the toast is an ode to gullibility.)

But on a separate register, I believe Athena is spot-on. She casts a vision for human reconciliation not as a numerical but a political, a redefining and renewing of the relationship fabric between plaintiff, defendant, and witnesses. It is a creative act that looks forward. It diverts attention from retribution, not because it is wrong, but because it is impractical, inadequate, and tiring.

When you flip a fair coin a large number of times, you expect the ratio between heads and tails to approach 1:1 as you record more flips. Likewise, the average value of a die roll approaches 3.5 as you record more rolls. There is an idea that this phenomenon, the Law of Large Numbers, is explained by the Law of Averages: when there has been a streak that is majority heads, it is only natural that upcoming rolls will be majority tails. As early as 1796, Pierre-Simon Laplace knew that the Law of Averages, or the Gambler’s Fallacy, is, of course, false. Long sequences of coin tosses are almost certain to converge to 1:1, but this is not because Nature keeps score and balances heads with tails. It’s because any apparent streak will, in unfathomably infinite experimentation, be diluted by comparable infinities of heads and tails (the Central Limit Theorem), like a drop in the bucket.

I fear we unduly commit a theological Gambler’s Fallacy when we reduce God’s cosmic justice by “in Christ reconciling the world to himself”3 to a cosmic Excel spreadsheet, a numerical balancing of the books, as if the Almighty’s coming peaceful reign will be ushered in by a detailed calculation and dispensation of who owes whom what, a system of simultaneous equations that only a divine mind can solve. While God is a meticulous judge, “punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and fourth generation,”4 enforcing reparation and atonement to the tune of Zeus’s Furies, he also mercifully clears debts, “reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them” (my emphasis).

Double-entry bookkeeping is like a physical conservation or continuity law, asserting that material value is never created or destroyed. But Christian justice staunchly rejects conservation and the economy of scarcity and the not-enough. Images of redemption in the Scriptures are of peaceful sleep, bountiful harvests, and vigorous streams. “Even the nations are like a drop from a bucket, and are accounted as dust on the scales.”5 When viewed through the lens of redemption, humanity’s total obligations barely register as a rounding error. The driving force of Christian reconciliation is not retribution, but dilution beyond measure.

The righting of wrongs is a statecraft, not of patching and fixing, but of enlarging and building. The political fabric that holds together, once torn, cannot be sewn. It can only be re-woven richer than before. We have an apocalyptic vision that Egypt and Assyria, Israel’s ancient captors and oppressors, are at last reconciled as neighbors: “On that day Israel will be the third with Egypt and Assyria, a blessing in the midst of the earth, whom the Lord of hosts has blessed, saying, ‘Blessed be Egypt my people, and Assyria the work of my hands, and Israel my heritage.’”6 The temple that formerly contained the house of Israel is expanded to include its former pariahs, and the new house worships more richly than the first.

The finger is on the “play” button, not the “rewind” button, in the vision of reconciliation that Athena articulates in Eumenides. There was a catastrophic flood in the Old Testament that turned back the clock, so to speak, to restore a less evil society. God vows never to do so again. From Noah on, correction, conservation, and restoration are not viable plans for world history. The only way out is forward; despite our efforts to make things right, “‘See, I make all things new.’”7 Just like the wounds on Jesus’s side persisted after his resurrection, humanity’s sin which caused the same wounds will not be erased from the story. It will only be out-narrated by abundant, amazing grace, not drowned by a flood of water, but washed clean in a fountain of blood.

3 2 Corinthians 5:19, New Revised Standard Version

4 Deuteronomy 5:9

5 Isaiah 40:15

6 Isaiah 19:24-25

7 Revelation 21:5

You will find an assortment of people as you walk around campus, each captured by their busy schedule. Some are aspiring authors, others gifted musicians. Some hope to become doctors, and others hope to become lawyers.

The first article I wrote for TAUG was titled “A Restless Culture.” You can still find it now in Volume 12, Issue 2 of our journal. That was my freshman year of college. The theme for that semester was Work and Rest. In it, I criticized people looking to their work for fulfillment. When I looked around, it was hard not to be cynical. My main critique was in pursuing work as an end in itself, and I saw many of my peers doing just that, regardless if their dream career leaned more altruistic.

There is, however, a downside to this attitude towards work. In my essay, I mainly penned with a negative disposition, seeing in what ways our work can go wrong or lead us astray. In discussing what not to do, I didn’t stop to look at what goodness might be found in occupation. This approach led me to eventually scoff at work as a whole. I took my ideas to their extreme, and led myself to think that the only career which was fulfilling would be that of a minister, since my work would be devoted to God.

Upon reflection, I’d now like to address my initial remarks; work is deeply entwined with what it means to be human. We were created to be working people. Adam, after all, was commissioned to work on the first few pages of the Bible. On these same pages, God gave Adam and Eve what theologians call the “cultural mandate”: that we are to steward the world in such a way so it grows into its fullest potential.1 This could be anything from composing music, to improving a city’s infrastructure, to even packing lunch for your kids everyday. It is immensely beautiful and distinctly Christian to live out this mandate in all of our different occupations.

In light of these things, a more favorable view of work could be one which neither idolizes it nor despises it. We can temper our propensity to polarize towards one side with reverence for God’s design, knowing that God’s design is intricate, perfect, and revealed to us in Scripture. Resting in this design gives meaning and goodness to a whole number of occupations I had previously discredited for myself. Now, I don’t know what job I will end up in, but I am in a much more peaceful place than before.

This exploration, finding the balance meant for us in the goodness of our work, might give us a good framework for engaging with all of creation. We might be encouraged not to discount everything as inherently bad, but learn to acknowledge and sit in awe of God’s good design for creation.

1 Chase DawsBen is a third-year Philosophy and Environmental Economics & Policy double major who loves making music with friends.

It was only a few months before my one-way plane trip to California when I realized that I would soon be moving across the country. I guess the idea of leaving everyone and everything behind hadn’t really hit me earlier. But just as much as I was nervous, I was excited. Soon, I thought, we will be off to college where we’ll find our little cliques. I could already see the clubs running rampant and flyers thrown across the walkway that I would later come to know as Sproul Plaza. Looking back, it all seems a little too picturesque. A little too perfect.

Now, I walk briskly with my earbuds tightly clutched in my hand, knowing that the faster I can get to my dorm, the sooner I can sit down and truly enjoy the coveted audiobooks I borrowed from my home library back in New Jersey. As I find my way up the cramped elevator and into my dorm, I breathe a sigh of relief. It feels like I finally reached my respite: my bed. But, I know the day is far from over. In just two hours, I will have to leave again for my fourth lecture of the day. Before that, I will try to squeeze in a 3-mile run and a shower, and if I can, I will do half a practice test for my midterm at the end of the week.

You know when you have those dreams where you feel like you are falling and then for just a second you wake up and take a big sigh of relief, realizing you were all but living a dream?

When I first arrived at Berkeley, that’s how I felt. From imposter syndrome to insecurity about my place in the world, I felt as if every waking moment of my life was a continuous struggle in the never-ending nightmare. Everyone around me seemed to be constantly doing something, leading me to doubt my own abilities as a competent student, employee and even as a friend. I was being washed ashore time and time again, lungs filled with the grimy saltwater of the Pacific. I was falling from a tower, as tall as the Campanile, but for some reason, my feet would never find solid ground.

Slowly, circumstances improved. My actions only healed when my heart posture with the Lord healed as well. I recognized my value as a fearfully and wonderfully made creation of God. In the same way, how I viewed myself was only reflective of whether or not I believed what God says about me. It would be a cliché for me to say that I found God amidst the uncertainty– that He gave me new breath in my lungs and steady ground to walk upon. Frankly, I don’t think that’s an accurate depiction of what had truly happened. Rather than finding God, I think God found me. Compared to God giving me new breath and solid ground, a more accurate metaphor would be that God gave me an oxygen tank and a parachute. Many nights, I prayed for God’s guidance, and, over time, I gained a rather peculiar sense of peace, despite my obstacles remaining. He told me that while He would not strip all my trials away from me, He guaranteed that trusting in Him would allow me to make it through in one piece. Retrospectively, perhaps that is what the feeling of peculiarity was: the peace that transcends all understanding. Being a freshman in Berkeley has been difficult. As someone who’s always taken pride in their independence and ability to take on the world, the freshman experience has really left me humbled. As a result, my ego has been continually beaten down and bruised, more so than I often let on. I’ve struggled with being vulnerable in the past, but without the direct support of my friends and family, I became more guarded than I had ever been. In the same vein, my struggles being vulnerable have also made me more dependent on my spirituality than ever before. Many days, I look down and see miles and miles of nothingness. But with my eyes open and mouth agape with wonder, I look up and see Him. If the trials around me are going to draw me closer to God, then all I can ask from Him is to keep me there: to keep me in the perpetual freefall of doom, falling thousands of meters, back into His arms.

... to keep me in the perpetual freefall of doom, falling thousands of meters, back into His arms.

”

“I wonder why…” Three simple words I often use. I use these words not only when I am amazed by something. I use them especially when things are going terribly wrong.

The suffering around me always leaves me with questions. I begin to wonder. I wonder why. Why do people leave? Why do I feel so numb to life sometimes? Why COVID?

My wonder is filled with worry. I wonder why I feel lonely, and worry that I will feel that way forever. I wonder why I don’t have that opportunity, that open door before me, and I worry about my future, or lack thereof. I wonder why the people and things I love most in life seem to be taken away from me and worry that I will never love people or things again.

Suffering from endless questions to worry about, I often feel stuck. In these moments, God feels like a God who only allows pain. The description of God as a God of beauty or wonder or glory repeatedly fails me. It’s as if I see God in parts. “God v1” is the God I read about in the Bible who is glorious, and “God v2” is the God I experience who is sometimes loving but often feels apathetic to my life.

Psalm 8 challenged this view of God for me. Psalm 8 begins by describing the glory of God as seen so blatantly in creation. This is the glory I would consider “God v1.” However, verses 3–5 begin to question this dichotomized view of God:

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?

Yet you have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor.

Psalm 8:3–5 [ESV]

These verses epitomize the unbelievable wonder creation inspires and also the incredible wonder experiencing God inspires on a personal basis. More surprising is the fact that this Psalm is actually referenced later in the Bible in Hebrews 2, and is actually a Psalm that talks about Jesus. This is called a Messianic Psalm.

Hebrews 2 suggests that the “son of man” referred to in this Psalm is actually Jesus Christ, who becomes “lower than the heavenly beings” for a while as He comes down to earth. This chapter in Hebrews focuses on how Christ suffered on the cross to bridge the gap between humanity and God.

As I read these two chapters of the Bible, I started to wonder. Should I be seeing God differently? Is the real astonishing part of God the fact that He is glorious AND He loves us intricately?

God cares about you and me even as He is so much more glorious than we could ever imagine. How? At the center of this love that God showers upon us is Christ. So, in many ways, God is most amazing in one moment. On the cross.

Christ’s suffering is essentially at the core of God’s glory! This blows me away. Often I question God in suffering and begin to worry. However, through suffering, God saves me, allowing me to wonder at His glory.

Christ suffered, showing that my suffering and the suffering I witness around me matters to God! It matters to Him so much that He sent Christ to suffer in order that one day in Heaven there will be no more of this mind-boggling pain. Christ on the cross turns the wonder and worry I feel around suffering into wonder and worship of the God who suffered once for all.

Witnessing the glory of this God who is both amazing and loving shifts my worrying wonder into worshiping wonder. Now, I have hope for heaven and I have worship in my heart. Suffering around me points me to Christ and to peace from Him.

So, let’s wonder! Let us allow our worryful wondering to take us to the cross, that we may glimpse the glory of our God and may be filled with hopeful wonder in our hearts daily.

Words: Christy Koh

The most eminent Venusian doctors were at a loss. None of them could diagnose the sudden illness, his mind’s withdrawal into coma. No matter. After a week of pumping drugs and nanos into his system, he was clutching at consciousness, and everyone considered that good enough progress. It was a shame his memory was shot. Though he was only catatonic for a week, the past months were lost to him, mere charcoal smudges of port-window spacescapes smeared on his smoothened brain. What was my last assignment, tactical exercise, planet composition report; for that matter, what was I even studying last trimester… and who cares? His thoughts oozed lazily as honey, mired in a sweet, viscous fatigue.

As soon as Nurse Shastry realized he could respond to sound, she informed him of her trials in ministering to him.

“Dear God, Amos, let me tell you: every day you would sit up and vomit, vomit, vomit like anything! You were on IV, so I don’t understand how you did it.” She leaned toward him with mock horror, whispering, “It’s almost like you were reincarnated as the merlion. Wish my weatherman could forecast this acid rain.”

Nurse Shastry talked too much. Still, the bizarre imagery wrung a dry laugh from him. “Guess I’ll check. Got a mirror?” She helped to prop his body into a sitting position and handed him her pocket compact.

In the grimy, silvered surface appeared a shock of unkempt curly locks, an unshaven jaw, both prematurely grizzled from the rigors of academy training. A beast! This staring creature seemed a separate species from the smoothcheeked, impeccable cadet who strode onto the Leviathan only two years before, whose eyes shone brighter than the stars they looked to. The reflection’s eyes scared him: one could drown in the stone cold voids. I’m an alien mer-

lion, he mused hollowly, imagining beta waves radiating through galactic deeps, vainly seeking likeness. What must the others think, to see me like this? He let his arm fall back and closed his eyes. A silent tear spilled down.

The rasp of coarse-woven cloth on his damp cheek yanked his morose thoughts unwillingly back into the room. “Poor dear, that won’t do. We’ll fix you right up, you young officer-to-be,” Nurse Shastry hmmphed sympathetically, brusquely dabbing at his eye with the cloth. “You’ve come far, and you’ll be back to usual in no time – it’s all a testament to your strength. Ad astra, per aspera, eh?”

Ah, you old hag, can’t you let me be depressed in peace? Amos grimaced wryly through the tears. Nurse Shastry continued to dab mercilessly.

Ding! A chime, indicating an incoming call on the ansible. Nurse Shastry withdrew her handkerchief at last and left the room. Reluctantly, Amos answered.

“Chien!” Amos winced as Major Sherman’s gruff voice boomed through the earpiece. “Heard you’re awake. How’re you faring, boy?”

“I’m alright, sir. Better.”

“Good to hear your voice again.” The major paused. “You’re missed in the lower units. Your mentees have been raising hell since you quit a few months back. The team’s right about to test their autonomous tunneling protodrone, and they want you to be there for the launch. It’s set to be one of the most profitable projects we’ve completed.” Sherman rattled off details as Amos waited in tense silence. With each word, the realities of past life thundered like dark rain clouds in his skull, washing away his blissful, honeyed lethargy.

“We’ve docked at planet Wolf 1061C and will have teams running comp analysis for the next month. A major shipment deadline’s at the end of the quarter, so you’ll need to catch up. Focus on healin’ up.” The major’s voice turned gentle, but to Amos the quietness only sharpened his words. “Shame this happened, but we have much faith in you. Everyone’s eager for you to return.”

I’m afraid your faith is misplaced. “Yes sir.” His lips were dry, his chest constricting. With all due respect, sir, how can you expect me to move on? How can you ask me to return, to operate as usual?

“That’ll be all then. Ad astra?”

But of course. He opened his mouth to muster a “Per aspera!,” but only managed a strangled gurgle. Here’s reality; now fall in line, strap on your harness, and pull hard with the inexorable surge of progress. Again he felt his gorge rise, choked on the sour, sticky dread that invaded his mouth. Get back to usual. Numb the pinpricks of conscience, plan mining campaigns, and rake in the cash. Catch up and deliver. What did anyone want from him other than what he could deliver? His stomach churned in anxious fury. Not staying to hear the ansible’s disconnect, he lurched from the room and reached the toilet just as bile forced its way out.

When the nausea receded, Amos slumped to the tiled floor, lightheaded and drenched in cold sweat. I can’t go back and perform as they want me to. Lightheaded, he couldn’t gather the strength to raise himself to return to the infirmary. Strangely, in his mind’s eye, a great rusty iron door appeared. He shuddered –there was malice in the thing waiting behind it. He fought the overpowering urge to forget, to hide, to run from what he’d barricaded his mind against. He forced himself to remember, to face, to heave open the door.

Waiting behind it sat a grim panel of examiners, bespectacled eyes flashing severely. “Tell us, boy, why do you want to go to space?”

This was not a difficult one. Question and response were practically engraved in his mind, considering the countless personal statements written, the interviews with admissions officers, sergeants, and finally the Grand Major of the United Earthian Space Force.

As a boy, he’d studied in school how, by the works of his hands, man gradually brought nature under his control: crops and livestock, stones and metals, rivers and mountains, tides and weather, sickness and aging, defiance of gravity, even the genomic substance of himself. Influenced by his parents’ faith, he came to believe that rationality was a special ability given to man by God. As the Psalmist wrote:

You have made him a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor.

You have given him dominion over the works of your hands;

you have put all things under their feet…

And what next to put under mankind’s feet? Mars and Venus, Neptune and Pluto, beyond the Milky Way, and the next, and the next! Space, strange and untamed, invoked some kind of extraterrestrial manifest destiny. Chasing space was a courageous pursuit to plumb the depths of the cosmic ocean, a brave foray to cast light on the unknown.

“Yes, yes, but that’s quite theoretical,” the panel insisted. “Give us something tangible, something inspiring.”

If you had asked him as a young Earthian initiate, he would have said this: glory, honor, awe. This was glory: defying gravity and biology to transcend man’s earthbound state by the concerted efforts of the brightest, most tenacious scientific minds. This was honor: seeking knowledge and technology to feed and flourish human life. Humanity’s crown was forged by boundless imagination, lofty ambition, and relentless curiosity. He, Amos Chien, had wanted to be the next to lead the charge.

“And what of awe, son?” The panel of examiners blurred, coalesced into an elderly man with kind eyes, clothed in priestly robes. Raising his gaze to the sky, the father continued reciting the psalm.

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?

What was creature compared to the Creator? Amos had beheld the Aurora Borealis, trudged through icy tundra, studied the sweep of an albatross’s wing. Among these, the distant stars were the most moving and mysterious things he knew. The same specks that vanished in the daylight blazed at several thousand Kelvin; if their paths were to cross, one would consume the Solar System with barely a hiccup. All his

life he’d been drawn to see the beautiful things God had made, and in searching, to consider their maker.

“So you sought to know God,” the father smiled.

“Yes, if not all of Him, at least to know a little more. At least a few important answers.”

“To what questions?”

“You know, father. Christ said that he ushered in a kingdom of truth. I devoted my life to finding the knowledge in the world that heals sickness, protects nature, keeps children safe and well fed. I wanted to understand you through your word and through your creation. But how can you let people who take your Word wreak havoc among innocents? Terrorists took your Word as a mandate to murder hundreds. The religious on earth remain divided, quibbling over semantics and cynical in their spirituality. A tyrannical leader rises up, incites war; another deceiver sows deadly conflict between his own people. Those fortunate enough to find success in the world must prioritize their own comfort to be happy. It’s blindness, drunkenness and escape and ignorant bliss, not the horrific wonder of knowing, that make this harsh reality bearable. And father—why does it seem that the more I discover, the more I realize that even your Word pulls the wool over our eyes?”

The father’s eyes widened at this blasphemy. Without warning the kindly smile gaped open, splitting at the jaw, horrifyingly twisted itself inside out over the wrinkled skin into a crimson glistening mask. “Youu!” Pulling a knife from its robes, the creature howled as it lunged at Amos and plunged the blade into his gut. “You of little faith!”

Amos cried out, clutching his abdomen, but it was words instead of black blood that spurted from his mouth. “But how! How can you simply say, ‘Have faith,’ when this sadistic plan commands us to suffer virtuously through pain after pain? You tell us to reach out and pray ad astra, to an intangible heavenly hope. No, even when we try to blind ourselves with sweet or pithy words there waits only aspera after aspera after all.”

The accusatory figure sneered at him, then morphed back into his own pale and disheveled reflection in the bathroom mirror.

In the end, as much as he wished it were not so, wonder only looked beautiful with one eye closed. He staggered out the bathroom door and—“Bloody ‘ell!”—collided with someone. There was a thump as a book and a girl splayed

onto the floor.

The girl gingerly sat up and looked at her scraped hands. “Ow…” She was just a kid, couldn’t be more than ten. A Venusian native, by the bluish pallor of her skin.

“Oh, I’m sorry,” Shame flared in his cheeks. “Are you hurt?”

She looked up and scowled. “Watch where you’re going, mister!” Seeing the distress on his face, her annoyance shifted to wariness. “Sir… is there something wrong with you?”

He grimaced. “Nothing a kid like you should worry about.” The girl shrugged and reached down to pick up the book, which had fallen open to a sketch on the inside cover: a pudgy pig with great feathered wings stretched above it, and something scribbled beneath.

The whimsical sketch and the girl’s irreverence piqued him, a welcome diversion from uglier thoughts. Amos couldn’t resist a jibe. “Aren’t you a little old for picture books?”

“Hey! It’s not a picture book, it’s Steinbeck!” She raised her chin with pride. “And I’m the first in my grade to start East of Eden.” Her brown eye glimmered, the fall forgotten, and the words flowed as she clutched the book to her chest. Amos found the girl’s passion quite endearing.

“My mistake, young lady. Tell me then, what’s it say under that pig?”

“‘Ad astra, per alia porci,’” The girl opened the book again. “It’s Latin for ‘to the stars, on the wings of a pig’.”

“Ah, so that’s how your family flew to Venus?”

“No! You’re silly,” She laughed. “They flew on a rocket ship, the ones your company builds.”

“What’s he saying, then?”

“Uh, pigs don’t have wings. So pigs flying would be kind of a miracle. He’s kinda saying he’s a pig, but he loves the stars, dreams big, and has the spirit and hope to reach for something that’s basically impossible,” The girl paused. “But maybe it isn’t.”

“Huh.” How could a pig fly? Even if it possessed dreams of the stars, would evolution deign to give wings to a creature so surely destined for the dirt? Not before starving its pudgy body or shaving down its wide bones, carving away the essence of pig via billions of generations running themselves off cliffs. And even with wings,

to flap into space—laughable! He supposed that, evolutionarily speaking, flying pigs were just as absurd as the idea that humanity could overcome its self-serving tendencies. Still, the desire was there.

“That’s a deep message to grasp. Count me impressed.” The girl beamed at his words. “So, kid, are there any stars you’re reaching for?”

“Yes.” She turned wistful. “I know it’s a lot to ask, and it cost a lot to bring my parents here, but I want to go to Earth one day. I want to explore forests and swim in the reefs. I want to kiss my grandma on the cheek.”

“Seems a worthy goal to me.” And an impossible one. Colonist families were committed to leave Earth for the rest of their lives, and their offspring too. But who knew? Ardent, seemingly wasteful love could overcome calculative progress.

There were realities beyond his knowing, beyond his control. It would take a miracle, to be sure, but perhaps he lived in a reality where beings meant for the dirt could be lifted toward noble dreams. Perhaps there was hope to be found with eyes wide open, a hope that breathed wonder back into a dead world. One only had to believe there was meaning to give wings to grasping.

“I have plans, you know. If you want, I can show you,” she offered shyly.

He took her little hand, and the warmth of it bloomed into the aching corners of his soul. Yes, he could think of a miracle that had made it possible.

WORDS: JUSTIN FUNG

Lovers and lost souls alike ask the same question as they approach a dreaded crossroads. We must go somewhere and to an ordained end, but what wisdom can guide us? Economic rationality commends she who chooses the end that holds the highest utility, and various philosophical traditions propose she choose the end with the highest moral good. Each path presents its various trials and rewards, appealing to various individuals’ desires. But what is good? And what is good to me?

Is good upheld virtue? The propagation of kindness and love? But what are those, my God? My immature comprehension of philosophical ethics cannot compel me to do much of anything, much less change my heart; how can I hope that they can be a light for my path?1 What good can my will do to lead myself and my friends? I can control neither my heart nor what I desire. Help me to no longer pursue what I know cannot lead me. Help me to delight in you and not to look for the happy life where it does not exist. Only your Word can define good and bring us Home.

Father, take the scales off my eyes to comprehend the extent of your love and to imitate your Son, the manifestation of love and goodness. He takes on the judgment for our sins, descends to the grave, and rises again; he satisfies your justice and demonstrates his love for sinners in his death and his life. Thank you, Father, for the gift of eternal life with you. How unsearchable are the depths of your love and how unknowable is the perfection of your character! What a true love you are, to care for your own, and to demonstrate the greatest love: to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.2 Compel me to do the same.

All things are for the magnification of the greatness of your name! Open my eyes to see and praise you for the change you have worked in my brothers’ and sisters’ lives. Oh how wondrous it is to behold even a glimpse of you, the unknowable, hidden God, through them! You hide yourself and work all things according to your will. How faithful and kind! Gracious patience marks the process by which you call us into being and restore us.

To pick up my cross and follow you, Lord, to render to you what is yours, and to love You and my neighbor. These things I read and hear uttered by my brethren, yet nothing in me desires your good. Create in me a new heart, Father, lest I sleep the sleep of death and consign myself to nothingness.3

Thank you for your Son and for my fellow man, who reflect your care and grace; thank you, Lord, for these mirrors that are an image of you, our one True Love. Remind us that we are but mirrors of you, the light of the world, and that your children are to reflect your light, that all may behold your name.

Whom have I in heaven but you?4 To know you is to be joyous; yet, I know that you will create sorrow in my heart, too, Lord, for the things you despise and the sin that clings closely to me. You are holy and the shedding of my sores is crucial to the growth of my love for you.

Reveal yourself to me, for I confess that I have blinded myself from you, the Immutable Goodness, and sought after shifting shadows. May your loudness shatter my dead heart; change me to delight in mercy, not sacrifice, and to render to you what is yours.5 For you are the only Way, and the only truth, and the only life. To your end I will go.

Amen.

Justin is a third-year Economics and Data Science double major ruminating on “Coram Deo.” In his free time, he enjoys Ultimate and singing.

“For you are the only Way, the only Truth, and the only Life . To your end I will go.”

I wonder, if between the cracks of dawn birthing clouds soon to drift, for doves to glide, white curtains, wherethrough a glinting light spawns, drape your windows lest Eclipse’s surprise–

if howbeit you unravel daybreak; my blooming pink peony–entice me sweet for prose’s sake.

Words: Sara Maral Helalian

Words: Sara Maral Helalian

NATHAN ANDERSON

GARY SCOTT

PATRICIA TSE

STEVEN VAN ELK

SAM MARX

BIRMINGHAM MUSEUMS TRUST

ANNIE SPRATT

SEHOON YE

GUY BASABOSE

NIKOLA TOMASIC

JULIA ZOLOTOVA

BEN DEN ENGELSEN

CORINA CHEN

AKIRA HOJO

KATRIN HAUF

LEONE VENTER

PATRICIA TSE

JENNY

PHOEBE CHEN

CLAIRE OH

GINO

MARK BASARAB

VERA SH

DIANA SCHRÖDER-BODE

PATRICIA TSE

“And why do you worry about clothes? See how the flowers of the field grow. They do not labor or spin. Yet I tell you that not even Solomon in all his splendor was dressed like one of these. If that is how God clothes the grass of the field, which is here today and tomorrow is thrown into the fire, will he not much more clothe you—you of little faith?”

Matthew 6:28-30

toanunknowngod.weebly.com