WELCOME. UNM ART MUSE/ZINE

You belong here.

The UNM ART MUSE/ZINE is a reflection of The University of New Mexico Art Museum’s exhibition, Hindsight Insight 4.0. The goal of this publication was to invite the UNMAM Student Advisory Council (SAC) to create a published response to this exhibition that exists outside of the museum’s institutional voice. The publication purses SAC’s mission of “empowering student voices, creating meaningful student connections, and facilitating ongoing student dialogues about critical subjects.” Throughout the Spring 2024 semester students in SAC were encouraged to conduct exploratory and multidisciplinary research through art making, text and visual based research in their projects.

We hope you enjoy reading this zine as much as we’ve enjoyed creating it!

Joseph McKee UNMAM Coordinator of Student Engagement & Technology

Hannah Cerne

You Belong Here, pg. 1

Analysis of Deliah Montoya’s MFA Thesis, pg. 17 - 18

MARKETING

Hannah is pursing an MA in Museum Studies and was recently accepted into the MA Art History program at UNM. She serves as a Graduate Research Assistant and Study Room Assistant at the UNM Art Museum. She is also a cartoonist for the Daily Lobo, an independent newspaper at UNM. Hannah is a member of the UNM Galleries, Libraries, Archives, and Museums (GLAM) Club and the UNMAM Student Advisory Council (SAC).

Andrew Roibal

Warhold Polaroids 2024, pg. 2 - 6

MARKETING

Andrew Roibal is a Native American artist based in the Southwest. After spending many years doing artwork as a hobby, he pursued art in college to develop his skills across a variety of mediums, specifically photography. His subject matter usually consists of constructed scenes, bringing a fictitious concept to life, with a focus in high-contrast portraits with vivid chromatic lightning.

Marina Perez

In Conversation with Zig Jackson, pg. 7 - 8

COPYEDITING

Marina Perez (she/they) is a cultural worker with ancestral roots in the Southern Sierra Madre Occidental mountains of West Mexico. She is a doctoral student in the Department of Art History at the University of New Mexico studying Native art and culture.

Shaun Pinello

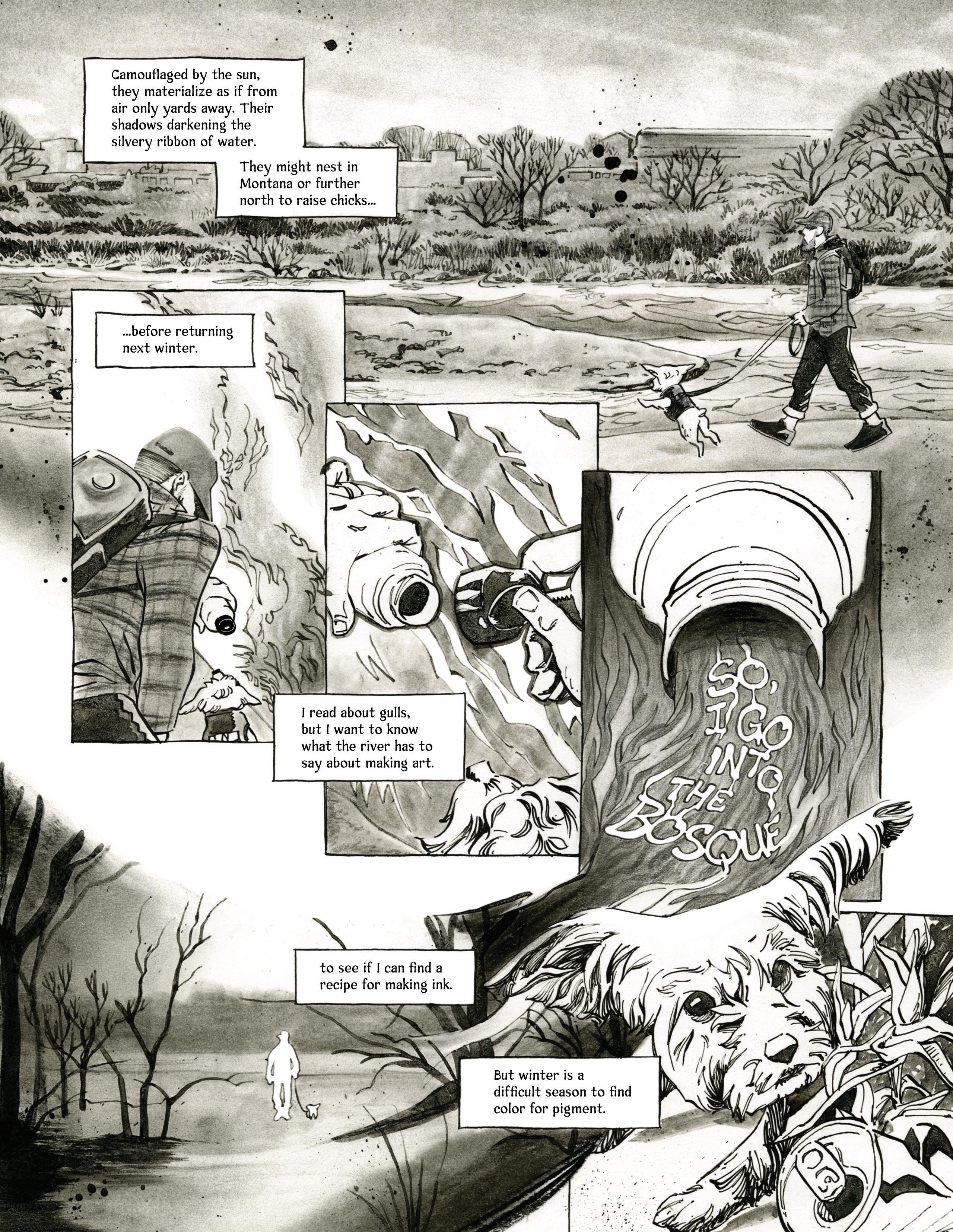

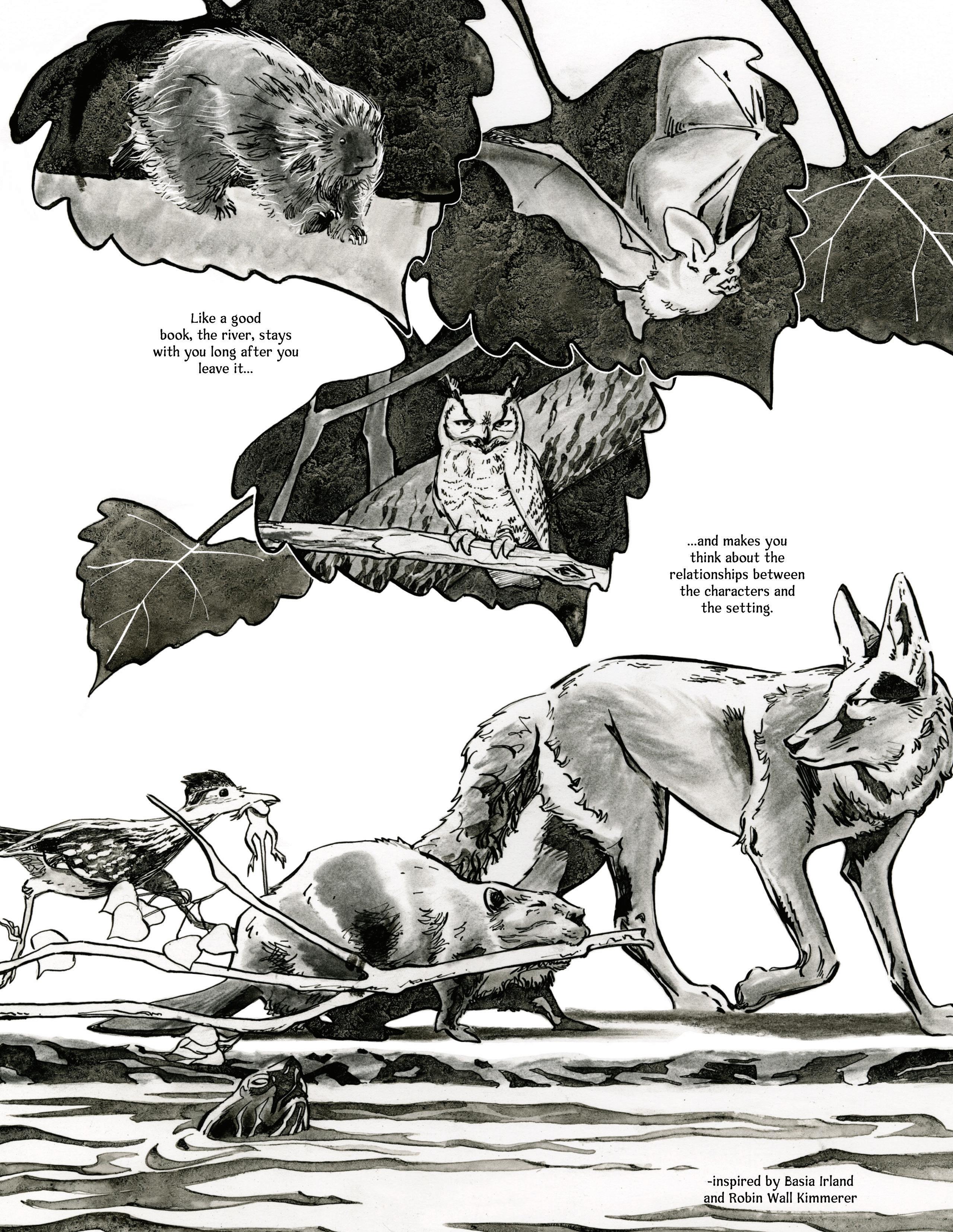

Reading Rivers, pg. 9 - 12

DESIGN

Shaun Pinello (he/him) is a husband to his partner Jessie and a friend to all dogs. He is currently working towards a BFA with a focus on printmaking.

Astrid Larson

Reflections of the Land, pg. 13 - 14

MARKETING

Astrid Larson (any pronouns) is a second year Linguistics and Interdisciplinary Arts student at UNM. Her work is multidisciplinary and experimental, drawing inspiration from the New Mexican landscape, her dreams, and Mexican folk art. See more of their art on Instagram @streed.art.

Armelle Richard

Reflection, pg. 15 - 16

DESIGN

Armelle Richard (she/her), a creative art enthusiast, embarked on her academic journey by earning undergraduate degrees in French Language/Culture and Photography from Pennsylvania State University. She recently achieved her MA in Instructional Design & Technology, along with a Professional Development Graduate Certificate in Museum Studies from the University of New Mexico. Armelle was born in France and lives in Albuquerque, NM with her husband, two children, and two cats.

Laura Olson

The Wild Flower Portrait, pg. 19 - 20

COPYEDITING

Laura Olson (she/her) completed her Master’s degree in Musicology at the University of New Mexico in 2024. Her interests lie in making museums more accessible and how music can play a role in museum spaces and interpretations of exhibits.

YOU BELONG HERE

Hannah CerneY

ou belong here

O

U

ur space welcomes all

nder our adobe architecture and through our glass corridor

B E

L

O

N G

eginning your visit with magenta, lavender, and forest green walls

xperience Eco Pulse and Self Identity along the halls

iving through the portraits and the natural materials displayed

wning your own thoughts, curiosities, and adventures as your mind becomes amazed

ext is the reading room for all to enjoy

rab a book and sit as if you have time to express joy

H E R E

ere is a place for all to belong

ven if you may feel foregone

ight here is where you can feel safe, so please stay

ven if you may be new to this place

Warhol Polaroids 2024

My project was done so that I could document my last semester at UNM, in a similar way that Andy Warhol did so from the late 1950s up until his death in the late 1980s. While some of the polaroids on display in Hindsight Insight 4.0 depict more varied moments of life, I wanted mine to have it’s own visual language so that the focus is on the subject matter of each print. Unique people in a unique place, in unique times.

In Conversation with Zig Jackson

Marina Perez

On February 20, 2024, I had the opportunity to interview contemporary Native photographer Zig Jackson (Mandan, Hidatsa & Arikara). In our conversation, we discussed several topics ranging from retirement, honoring our mentors, and respecting women as family and community story-keepers.

Through our conversation, I learned Jackson’s former creative practice as a painter and potter led him to study in the Department of Art at the University of New Mexico. Through the mentorship of UNM Photography professors Tom Barrow, Betty Hahn, Patrick Nagatani, and Rod Lozorik, Jackson developed a practice and career in photography.

Jackson shared one of the strategies he would often employ while selling his work as a UNM art student, “Frontier. That’s where I used to sell. I used to sit at the brown table in the back

and have all my work. And if you want to buy my work, meet me in the rug room.” I greatly appreciate Jackson sharing this memory as he offered a glimpse into the determination and resourcefulness artists practice to connect with potential buyers and engage directly with local community members. Through Jackson’s willingness to remain accessible to the local community, he utilized a beloved community space to strengthen the connection between art, people, and culture. These principles are further reflected in Two Moons Stoic/Two Moons Smiling (1991, printed 2000), currently on view in The University of New Mexico Art Museum’s exhibition Hindsight/Insight 4.0.

Jackson’s Two Moons Stoic/Two Moons Smiling is part of a series that challenges stereotypical representations of Native Americans. Presented as a diptych, Two Moons Stoic/Two Moons Smiling includes two photographs of Austin

Two Moons, a Northern Cheyenne elder and Medicine Man from Busby, Montana.

Viewers are first introduced to Two Moons as he is seated on a rocking chair with his right leg elevated and extended outward. In the first image, his gaze follows the direction of his body, providing the camera with a side profile view. Through his neutral facial expression and turned body posture, the image is reminiscent of early twentieth-century photographs depicting Native men as stoic. In the second image, Two Moon breaks from his “stoic” posture and smiles directly towards the camera. His engagement with the viewer invites us into a moment of genuine warmth and connection.

The background of these two images depicts Two Moons’ family photographs, personal memorabilia and cultural objects. Two Moons was a direct descendant of Chief Two Moons a Cheyenne military leader and chief who participated in the Battle of Little Big Horn of 1876. The background of the photographs provides significant cultural context, offering insights into Two Moons’ ancestral connections, tribal history, and cultural heritage. The background elements serve as a visual anchor, with Jackson emphasizing the shift in Two Moons’ facial expressions and drawing attention to the nuances of human expressions.

From stoic to smiling.

By positioning these two photographs sideby-side, Two Moons’ joyful expression creates a critical intervention in the colonial representation of Native peoples. In our conversation, Jackson reflected on the misrepresentation of Native Americans in photography, “Native Americans have the greatest sense of humor. We laugh, we joke, and we play. Then we got to be stoic because that’s what the turn of the century did with those cameras.” The departure of posing for settler imaginaries allows for new visual material to be re-imagined such as portraits of elders smiling. Two Moons modeled a sense of candid joy that further represents the resilience, defiance, and hope

Native peoples continue to embody.

Nearing the end of our conversation, Jackson shared, “He has the most beautiful smile.”

Revisiting my interview notes, I was moved to have a meal at Frontier in Jackson’s honor. So, I ordered his favorite dish and sat in his favorite room.

I sit here now, smiling and eating green chile stew in the rug room.

Green chile stew and tortilla served on a brown tray (TOP). Rugs with various Southwestern patterns hang on the walls and ceiling of Frontier Restaurant in Albuquerque, New Mexico (BOTTOM).

Additional Notes:

In 2023, Zig Jackson retired as a Professor of Photography from the Savannah College of Art & Design, yet he continues to support and mentor many of his former students. In 2024, Jackson received the prestigious 2024 Honored Educator Award from the Society of Photographic Education (SPE). This award recognizes Jackson’s enduring commitment to nurturing emerging artists and scholars.

A very special thank you to Zig Jackson for sharing virtual space to share his stories and experiences in the arts.

Reflections of the Land

Astrid Larson

My pieces play off of interpretations of reflection and its relationship with New Mexico. The jackalope is a mix of literal interpretations the shadow and river reflection and figurative ones the jackalope reflecting the mythology of the southwest. Roadrunners, our state bird, are another animal that has become an icon of the land, reflecting what we see around us and our desire to create a symbol for our state. The following piece reflects my personal interpretation of the creatures of New Mexico through an original character that I have developed and drawn throughout the year. All of these creatures are set in the classic scenery of New Mexico, which is familiar and comforting to those from here. This creates yet another reflection on our views of home and how we internalize the feelings associated with it and reflect them into our lives.

Reflection

Armelle Richard

This reflection on portraiture comes from my deep appreciation for art history and artistic tendencies. You will find me most comfortable on the non-subject side of a camera as demonstrated in this portrait I took of my son. In this untitled piece, I used bright colors, to exemplify his exuberant personality. This portrait goes beyond the simple chronicling of his likeness in a photograph. Overlaying the image is an intense pink mark, sketching a framework, a croquis of sorts. This element was challenging since most of my artistic expression has been through photography Unsurprisingly, I felt more comfortable creating a portrait of someone I knew well. Rarely do I take images of people, especially of strangers. Just thinking of the word take seems invasive — however quickly the camera shutter snaps.

Growing up outside of Philadelphia not far from Amish communities, I learned the Amish don’t want their photos taken. The Amish feel that it “promotes individualism and vanity, taking away from the values of community and humility by which they govern their lives.” [1] As artists making portraits, we are in some way taking or capturing something from our portrait subject to put on display. While I don’t have practical experience with other formats, I would consider it even more intimate to sculpt, paint, or draw someone given the time commitment and handwork needed for these mediums.

When we take a portrait, we say something about a person’s character by the expression of that person in imagery, be it from the use of light, darkness, color, crop, or angle. This can be true of self-portraits as well. This statement by philosopher Plotinus (3 A.D.) struck me, “Self-portraits are produced not by looking out at a mirror, but by withdrawing into the self”. [2] The self-portrait captures who we are well beyond our exterior facade and prompts us to explore our interior identity. A portrait, self-portrait, and even a selfie are all visual representations of individuals. How people present themselves visually is a complex interplay influenced by internal factors —

such as personality, values, and beliefs and external factors — such as societal norms, cultural influences, and personal goals. Portraiture, in all forms, has a long history that plays a central role in shaping and reflecting who we are. Whether serving as historical records, capturing memories, or reflecting our identity, portraiture figures prominently in society. There is a “timeless delight in our ability to document our lives and leave behind a trace for others to discover.” [3]

Portraiture, in a broad sense, has been around since the early Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, but it wasn’t until the Middle Ages that we began to see ourselves, quite literally in mirrors. [4] Arguably, the Renaissance brought the desire to give an accurate likeness to the portrait’s subject. While once reserved for those with privilege, power, or status, several crucial innovations brought us to a time where capturing one’s likeness has become commonplace and accessible to most. The digital age brought “technical innovation resulting in the increasing democratization of the medium.” [5] In photography specifically, from the invention of handheld film cameras to the digital camera, and currently, with our ubiquitous use of smartphone cameras, capturing a photograph has become more equitable and inclusive. Despite the illusion of being spontaneous or informal, carefully curated selfies have become a valuable tool for branding and self-expression in the modern-day online landscape.

Hindsight Insight 4.0 pulls work from the museum’s extensive collection. Two sections shape the exhibition; Eco Pulse: Rise and Fall focuses “on the interconnections between humans and the natural world,” and A Sense of Self: Performing Identity for the Camera “explores photography’s role in constructing identity and public personas.” [6] The photography in the exhibition captured my attention. It encapsulates an amazing amount of work. Small prints lend themselves to creating a cohesive group including Mike Disfarmer’s Gelatin silver prints and Andy Warhol’s Polaroids. The show successfully portrays the broad application and the evolution of how a photograph is made. Many earlier pieces (c. 1800s) featuring unnamed subjects are interestingly not credited by an artist. Thus, to the viewer the photographer does not seem important. Does this speak to how the ability to capture images evolved from merely an act of archiving, or a tool for the means of emotional and artistic expression? The artist’s identity becomes more relevant when portraits become artistic. Notably, the framing in some of the portraits has the subject staring right down the viewfinder, engaging directly with the audience. Other subjects deliberately avert their gaze.

Above all, the most powerful feature in the space is the in-gallery photography studio, which allows visitors to participate by taking photographic portraits of themselves or as a group. This activity exemplifies the ease with which we can capture images today and provides a safe space for visitors to express themselves. In the end, portraiture transcends a mere depiction as it examines the complexity of human history and identity. From ancient times to the modern-day digital era, portraiture has evolved, through technological advancements and broader implications of representation and artistic expression. Through the lens (so to speak) of portraiture, narratives are shaped, and perceptions are challenged. Portraiture appears to remain a timeless reflection of our shared human experience.

[1] “The Amish and Photography.” PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/amish-photgraphy/ [2] Hall, James. “The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History.” (New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 9. [3] Wortham, Jenna. “My Selfie, Myself.” The New York Times, October 20, 2013.

[4] Hall, James. “The Self-Portrait: A Cultural History.” (New York, NY: Thames & Hudson, 2015), 8. [5] Rawlings, Kandice. “Selfies and the history of self-portrait photography.” OUPblog, November 21, 2013. https://blog.oup.com/2013/11/selfies-history-self-portrait-photography/ [6] Exhibition wall text panel from Hindsight Insight 4.0.

Analysis of Delilah Montoya’s MFA Thesis

Hannah CerneDelilah Montoya is a Contemporary Chicana artist who was born in 1955 in Fort Worth, Texas, and raised in Omaha, Nebraska. Montoya moved to New Mexico to earn a BA, MA, and MFA from the University of New Mexico between 1984 to 1994. Her family influenced her decision to attend the University of New Mexico in Albuquerque as well as the beautiful landscape, and the inspiring professors and leaders at the university. Montoya desired to learn about her Chicana culture in New Mexico and used her opportunity of attending UNM to do just that.

Montoya has taught at Smith College, Hampshire College, California State University, the Institute of American Indian Arts, and the Fine Arts Department at the University of Houston since 2001. While pursuing a career in academia Montoya continued to practice her skills and techniques as a studio artist. Her work has been shown at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the New Mexico Museum of Art, the Mexican Museum, the University of New Mexico Art Museum, and many other institutions.

As Montoya pursued her education at UNM, she worked with, and was mentored by, many experienced and knowledgeable professionals. One of the mentors whom Montoya worked with and learned from was Ann O’Keefe, Montoya states, “I learned how to produce photo printmaking from Ann O’Keefe. I would show up at the printmaking department. She was there, and I would run the press for her.” Other mentors and advisors who supported Mon-

toya’s path include Betty Hahn, Patrick Nagatani, and Flora Clancy. Montoya utilized the bright minds around her and found support within the art community at UNM.

Throughout the Spring 2024 semester, a piece from Montoya’s master’s thesis, a collotype titled, Sagrado Corazon: Loca y Sweetie (1993) is on display in Hindsight Insight 4.0 at the UNM Art Museum. Montoya’s sitters include two young women who were students at UNM. The image shows two women dressed,

as Montoya describes them, “cholas.” The young women are posed against graffiti-covered walls side by side, leaning against one another with subtle facial expressions. Montoya’s portrait challenges the term “chola” and its use for the identification of individuals.

Montoya’s collotypes from her master’s thesis series, Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart, depicts people from the Albuquerque community, showing identities through portraiture. The photographs used for her thesis work, taken in her studio in the Art Annex at UNM show individuals and groups of people posed in front of walls covered in graffiti, including a painted Baroque Sacred Heart on one wall. Montoya’s studio provided a space where she could experiment with her work and create art that challenged the public and current ideologies.

As she continued her education and her master’s thesis projects for both her MA and MFA, she looked deep into her heritage and culture. Montoya began her research with the blending of European and Indian religious traditions. The Sacred Heart, or El Corazon Sagrado, is a cultural icon that Montoya investigated. As she furthered her investigation and research, she sought affirmation of her own Chicana identity by exploring her homeland, Aztlan (northwestern Mexico and the southwestern United States, the ancestral home of the Aztecs). As she searched for configurations of her vision, Montoya continued to research the history of the Sacred Heart. The Sacred Heart has been a religious symbol in Nahua (central Mexico populations) and European philosophy. By the sixteenth century, the confrontation of both cultures resulted in the creation of the Baroque Sacred Heart.

Montoya’s research led her to conclude that the Baroque Sacred Heart symbolizes the outcome of cultural exchange through religious imagery. The modification of religious imagery in this exchange, like in the creation of the Baroque Sacred Heart, shows the European appropriation of Nahua aesthetics. When Nahua Society and European Catholicism developed

a relationship through the Baroque Sacred Heart, they exchanged their ideologies. Montoya utilized her research of the Baroque Sacred Heart and its history to inspire her master’s thesis, Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart, where she explains that it is not unusual for two different cultures to choose the human heart as a religious symbol of the divine.

Montoya’s boldness in the face of objection is inspiring to all young artists trying to break into contemporary art communities, a trait prominently shown in Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart. The inclusion of community members as sitters displays identity through portraiture, this shows Montoya’s thoughts on identities through her and the sitters’ heritage and culture. Montoya’s collotype Sagrado Corazon: Loca y Sweetie (1993) is a fine example of confronting the “chola” identity, by posing two young female students as such. The Baroque Sacred Heart graffitied on the walls along with many other hearts are prominent displays of the religious and cultural transitions colonizers have enforced on the religious symbol. Delilah Montoya followed the path of curiosity and passion, which led her to become one of the most prominent Chicana artists in the United States.

To learn more about Delilah Montoya and her thesis, Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart, scan the QR code below to read Sagrado Corazon Sacred Heart: An Interview with Delilah Montoya on Here to Inspire: the UNM Art Museum Journal.

Hannah Cerne. “Sagrado Corazon Sacred Heart: An Interview with Delilah Montoya .” UNM Art Museum, 2024.

Montoya, Delilah. “Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart.” Thesis, University of New Mexico, 1-8, 1994.

Hernandez, Rigoberto. 2015. “The ‘Folk Feminism’ Roots of the Latina ‘Chola’ Look.” NPR. https://www.npr.org/ sections/codeswitch/2015/04/22/401263832/the-radicalroots-of-the-latina-chola-look.

The Wild Flower Portrait

Laura OlsonIn writing a musical piece for Julia Margaret Cameron’s The Wild Flower (Allegorical portrait of Anne Chinery, Mrs. Ewen Cameron) (1867), I let the art itself guide me. Working from a thumbnail of the portrait, I created a grand staff and added musical notation across the image. Musical notes coincide with the woman’s eyes, nose, chin, and hair but also occupy the edge of the piece as well. While I took artistic license to add dynamics and trills, I wanted to keep the music fairly simple and let the art be my guide for writing. To create a piece with 32 measures, I reoriented the thumbnail and redrew the grand staff. This gave me four combinations of notes I could use and allowed me to play with rhythm to make the piece more interesting for listeners. The inspiration for this project came from the desire to understand visual art through my field of study in music. The integration of various Arts (I use capital A to distinguish arts as an umbrella term to cover all art forms), is often overlooked and separated from one another. With my piece, I hope to inspire others to combine different art practices to create interdisciplinary approaches to their respective fields.

To listen to The Wild Flower Portrait scan the QR code belowor visit artmuseum.unm.edu/exhibition/sac-spring-24

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Wild Flower (Allegorical portrait of Anne Chinery, Mrs. Ewen Cameron), 1867. Albumen print. 72.484. University of New Mexico Art Museum.

Julia Margaret Cameron, The Wild Flower (Allegorical portrait of Anne Chinery, Mrs. Ewen Cameron), 1867. Albumen print. 72.484. University of New Mexico Art Museum.