EXTENDED REALITY IN THE CITY:

Examples of use of immersive technologies in different scale urban public spaces or cultural heritage site.

A dissertation submitted to the Manchester School of Architecture for the degree of Master of Architecture (MArch).

The cover was produced by Dream by WOMBO

Declaration

No portion of the work referred to in this dissertation has been submitted in support of an application for another degree or qualification of this or any other university or other institute of learning.

Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the author and lodged in the John Rylands Library of Manchester. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made.

Copyright

Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the author. The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Manchester School of Architecture, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the university, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement.

Further information on the conditions under which disclosures and exploitation may take place is available from the Head of Department of the School of Environment and Development.

2

Acknowledgement

First of all, I would like to thank Dr.Jessica Symons for her expert advice and encouragement throughout this challenging project

Thanks to my parents, Mr Deng and Mrs Li, for their endless support, kind and understanding spirit during my case dissertation.

To all relatives, friends, and others who in one way or another shared their support, either morally, financially and physically. Cheers.

3 Extended reality in the city

Acknowledgement

Abstract. List of Figures.

Chapter 1: Introduction.

1.1 Background.

1.2 Aims and Structure.

1.3 Methodology.

Chapter 2Extended reality applications Review.

2.1 Introduction: The technical background of extended reality.

2.2 The Seville Principles.

2.2.1 Principle 1: Interdisciplinarity.

2.2.2 Principle 2: Purpose.

2.2.3 Principle 3: Complementarity.

2.2.4 Principle 4: Authenticity.

2.2.5 Principle 5: Historical Rigour.

2.2.6 Principle 6: Efficiency.

2.2.7 Summary for evaluation system

2.3 Cases for different urban scales Review.

2.3.1 City 2.3.2 District 2.3.3 Public area 2.3.4 Building 2.3.5 Monument

2.4 Conclusions.

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale.

3.1 Background.

3.2 Process.

3.3 Technology. 3.4 Achievements.

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake.

4.1 Background.

4.2 Process.

4.3 Technology.

4.4 Achievements.

4 Extended reality in the cityContents

Contents

Chapter 5: Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts within cities.

5.1 Background. 5.2 Process.

5.3 Technology. 5.4 Achievements.

Chapter 6: Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni.

6.1 Background. 6.2 Process.

6.3 Technology.

6.3.1 Project1: 360-degree panoramic photos

6.3.2 Project2Interactive VR experience

6.4 Achievements.

Chapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square.

7.1 Background.

7.2 Process.

7.3 Technology. 7.4 Achievements.

Chapter 8: Conclusion. Bibliography.

Figure References.

5 Extended reality in the city

Contents

All of the top 10 technology companies, including Apple, Google, Samsung, and Microsoft, are now all jumping on board and investing heavily in the virtual reality technology. In fact, 75% of the top100 plus companies on Forbes' list of the world's most valuable brands have already launched their development of virtual reality or augmented reality experience services for their customers or invested in developing the technology. Suffice it to say that VR/ AR/XR technology is going trendy (David, 2016). Virtual reality and augmented reality technologies have long influenced the populace on varying scales and in a plethora of urban application scenarios. With regards to immersive technology, 3D modelling, gamification, and virtual worlds (metaverse) are some of the typical concepts. However, practitioners rarely consider the use of this technology in the context of feasible urban applications. This dissertation will summarise the evolution of this technology in terms of the various scales of Extended Reality applications in urban environments. The analysis of extended reality applications is achieved through a qualitative study of the relevant literature and case studies. Through the analysis of cases at various scales, the rules for the application of extended reality technology in urban environments are summarised, and attempts are brought forward to enhance its application. Abstract

6 Extended reality in the city

Abstract

List of Figures

Figure 1. Illustrations Information on the classification of urban scales.

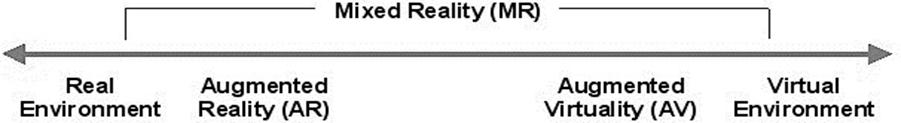

Figure 2. The initial figure from Milgram and Kishino.

Figure 3. Distinction between VR, AR and MR.

Figure 4. Gent aerial.

Figure 5.Data exchange from open 3D data over Sketchup to a 3D web viewer and Unity.

Figure 6. Configuration of the Skyline Globe and Unity Web build server.

Figure 7. the 22 February 2011 earthquake struck Christchurch, It shows the city's CBD enveloped in a cloud of dust.

Figure 8. CityViewAR s displaying virtual construction sites in AR view.

Figure 9: The Map view displaying POIs as icons on the map.

Figure 10: The popup dialog displaying the description of a chosen virtual architecture in AR view.

Figure 11: Views for distinct kinds of content: Detail view and Panorama view (from top to bottom).

Figure 12. the square in front of Gwanghwamun.

Figure 13. (a) Don˘uimun before destroyed estimated early 1900s.

Figure 14. Field visits :(a) virtual reality experience halls with visual gates and urban landscapes in the Jos˘on era; (b) AR of the position and shape of "Don˘uimun" that is confirmed by mobile phone.

Figure 15. the interior space of Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni.

Figure 16. Stanza dei Prototipi, Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni.

Figure 17. Shooting Technical Scheme.

Figure 18. Panoramic picture of “Stanza dei Prototipi”.

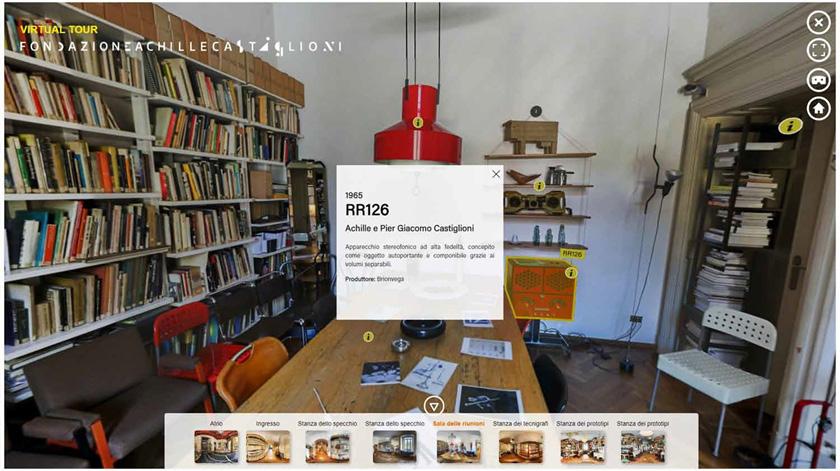

Figure 19. Virtual tour, view of the meeting room with interactive elements.

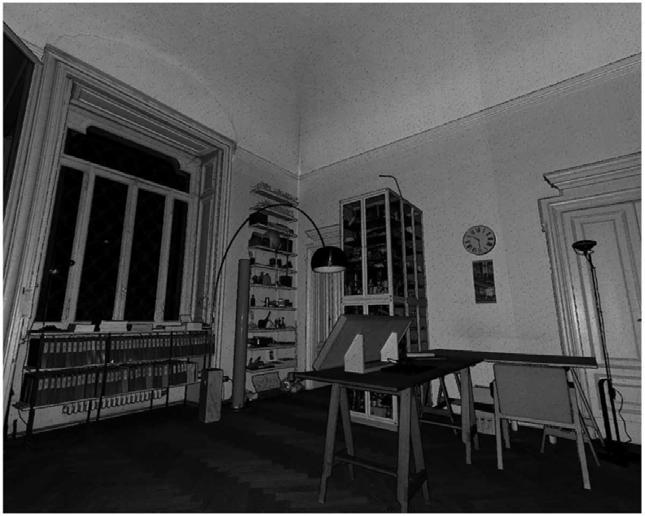

Figure 20. The point cloud details (Recap).

Figure 21. Workflow for modelling architecture components (Rhinoceros) .

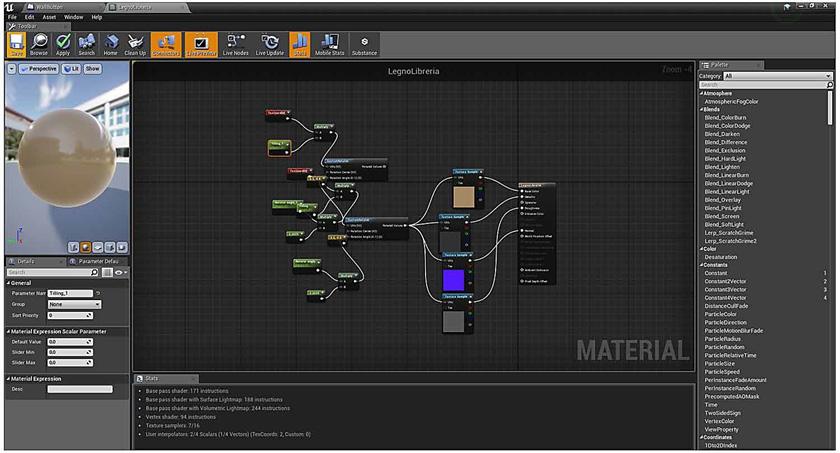

Figure 22. Material Editor (Unreal Engine).

7 Extended reality in the city

List of Figures

Figure 23. In the foreground, the interactive box (labeled with phrase “prototipi Gibigiana”) and the open drawers (Unreal Engine).

Figure 24. the Wignacourt Fountain.

Figure 25. The Wignacourt fountain today located int St. Philip Garden in Floriana (Malta).

Figure 26. The scheme of workflow.

Figure 27. Historical exhibition of the Wignacourt Fountain in St. George's Square in the early 18th century.

Figure 28. Reconstruction of dense cloud in St George's Square from merging TLS scan.

Figure 29. The Dense cloud reconstruction of Wignacourt Fountain from Digital Photogrammetry process using Agisoft Photoscan software.

Figure 30. Spacekit which is a tool for design large-scale AR.

8 Extended reality in the city

List of Figures

Chapter 1: Introduction

1.1 Background

Evolving 3D technologies (virtual reality, augmented reality, as well as mixed reality) enable us to represent and interpret the present, the past, and the future in the real world (Ioannides, 2017, page3). The virtual and real worlds are constantly intertwined, colliding, and connected. The real city is being virtualised, while the virtual world expands. Using immersion technology, the virtual cultural heritage in turn contributes to the preservation of the historical remembrance of the real city's inhabitants. Mankind in the 21st century could be said to be dreaming on a continuum between the real and the virtual (Matthys, 2021). This dissertation encapsulates the contribution of AR, VR, and MR technologies to various urban scenarios by focusing on the current application of immersive technologies in the city at various scales. Through case studies of the application of VR, AR, and MR technologies in different scales of urban environment, this dissertation strives to summarise the rules of application of immersion technology in various scenarios and to enhance the application of this technology in the architectural space through a critical analysis of each case.

1.2 Methodology

First and foremost, this dissertation will employ interpretivism as the research methodology. There is no unified model for the application of extended reality technology at all city scales, and different projects at different scales and in different locations may apply different techniques to address different challenges. The only way to explore the application of extended reality technology, consequently, is to implement the interpretivism philosophy to each case in conjunction with specific theories for a reasonable analysis.

Secondary, this article will analyse the application of extended reality at different scales in cities through a qualitative approach utilizing literatures reviews and case studies. A literature review is a necessary research tool for understanding the current state of development of virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), as well as mixed reality (MR) technologies. A review of immersive technologies in spatial sciences undertaken by the University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland FHNW

9 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 1: Introduction

(Çöltekin, 2020) documents unresolved issues and research challenges in the field of extended reality (VR, AR, MR) and research challenges. This section offers a brief summary of the setting information on the field in extended reality (Çöltekin, 2020). Whereupon an invertigation of the current status in the usages of extended reality technologies is presented. The urban scale is subdivided, ranging from an entire city, a city district, a public space, a building, and finally to a monument. A corresponding case is sought for each urban environment at various size scales, and an endeavour is made to summarise the patterns by which this extends to pragmatic applications. Thirdly, The book Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage, co-authored by Marinos Ioannides ( Founder and Director of Digital Heritage Research Lab in Cyprus University of Technology), Nadia MagnenatThalmann (founder and director of Interdisciplinary Laboratory of Human Computer Animation at the University of Geneva) and George Papagiannakis (computer scientist specialising in computer graphics and VR, AR) recording The Seville Principles, offers several principles on the field application of extended reality to digital heritage (Ioannides, 2017). This principle will serve as an essential evaluative framework for the analysis of the individual cases presented in this article.

Finally, through the analysis of the cases at various scales, the rules for the application of extended reality technology in urban environments are summarised and efforts are brought forth to enhance the application of extended reality technology.

1.3 Structure

The following section of the dissertation consists of a literature review that outlines the technical definitions of extended reality (VR, AR, and MR) and provides brief examples of application scenarios for each technology. Due to the lack of theory in evaluation in extended reality applications at various scales in cities, this dissertation introduces the international principles of virtual archaeology to enrich the evaluation perspective of extended reality technologies and to establish a system for the evaluation of extended reality applications. As case studies will be leveraged to advance the research in this dissertation, a review of

10 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 1: Introduction

each case is necessitated. Each case is then presented, evaluated, and analysed. Following a multidimensional analysis of the cases, conclusions are drawn, and an attempt is made to summarise the extended reality technology's application.

Figure 1. Illustrations Information on the classification of urban scales.

CITY DISTRICT PUBLIC AREA

CITY DISTRICT PUBLIC AREA

11 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 1: Introduction

BUILDING MONUMENT

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

2.1 Introduction: The technical background of extended reality

The aim of this research is to analyse the application of Extended Reality (XR) at various urban scales. Understanding the precise meaning of Extended Reality (XR) technology is paramount for analysing its applications. VR, AR and MR refers to the technical and the conceptual suggestion of space interface has been studied for decades by researchers in engineering, computer science, as well as human computer interaction (HCI). Nowadays, term extended Reality (XR) has been applied to describe whole spectrum of VR, AR, as well as MR (Çöltekin, 2020). MR can also be perceived as an intermediary between real and virtual environments, blending elements of the physical world and the virtual world.

VR, AR, as well as MR are three distinct technologies that are interconnected and intertwined. Therefore, three conceptions are indispensably distinguished in order to comprehend relationship among present cases and the requisite virtual demonstration.

- Virtual Reality (VR): Interactive computer-produced experiences happen in a simulation surroundings. VR primarily involves auditory and visual feedback, however other modes of sensory feedback are also viable. Using a VR device, a person can "look around" in an artificial world, move around, and co-act with environment (manipulate objects or activate mutual effect factors) (Bolognesi, 2020).

- Augmented Reality (AR): There is an interaction experience with the real environment in which real-world objects are 'augmented' with computer-generated virtual information via various sensory formations (Bolognesi, 2020).

- Mixed or merged reality (MR) virtual data with real world; rather, it places virtual objects into real world and enables users to co-act with those objects. This technology is prevalently referred to as "mixed reality": it is the world fused of reality and virtual whereby the physical world and digit objects exist together and co-act in real time (Bolognesi, 2020).

Figure 2. The initial figure from Milgram and Kishino, in 1994.

Figure 3. Distinction between VR, AR and MR (Bolognesi,2020).

12 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

Each of the three distinct technologies possesses unique characteristics and application potential. As an electronic device, Virtual Reality (VR) enables users to immerse themselves in a completely virtual world. This means the technology can be used to construct a virtual city on a large scale or to virtualize the interior of small buildings through 360-degree panoramic photographs. Augmented Reality (AR) is more of an interactive experience, where the user is placed in the real world and uses a mobile device or wearable to receive enhanced feedback on real information. Humans are the primary subject of interaction, so the application scenarios for this technology must also be on a human scale. The primary object of interaction is information; therefore, its application consists of virtualizing information at the urban scale and providing access to it for human interaction. Mixed Reality (MR) is the blending of the virtual and the real world to create an immersive experience. Therefore, applications such as virtual shopping and virtual environments stand to gain more from this technology.

2.2 The Seville Principles

Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various scales in cities reveal that the primary goal of the projects is to preserve cultural heritage. In these instances, the transformation of cultural heritage into digital heritage is the common denominator. To date, the major of XR study has been driven by technology (Çöltekin, 2020), despite the fundamentally philosophical nature of XR developments and their inspiration. This is the reason why there is a lack of holistic theory regarding how to evaluate a technology utilisation situation involving extended reality. In order to evaluate the projects in the case studies, the research introduces the international principles of virtual archaeology, called the Seville Principles. Interdisciplinarity, Purpose, Complementarity, Authenticity, Historical Rigour, Efficiency, Scientific Transparency, and Training and Evaluation are the eight sections of the International Principles of Virtual Archaeology (Ioannides, 2017). This section of the article reviews the various components of this principle and summarises the evaluation system for Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales. Scientific Transparency and Training and Evaluation for the Evaluation system of Case Studies of extended reality (XR) at the construction of various urban scales are not applicable, so it will not be discussed here.

13 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

2.2.1 Principle 1: Interdisciplinarity

Given the complexity of computer visualisation of heritage, it encompasses disciplines such as history, heritage conservation, architecture, computer visualisation, and etc. Such an intricate issue cannot be resolved by an individual kind of specialist, but rather requires the collaboration of a large number of specialists (archaeologists, computer scientists, historians, architects, engineers, and so on). Methodically, however, this proposal is limited by the budget available for each project (Ioannides, 2017). In a sense, the more complete the team of experts in a project, the higher the quality of the completed project. Consequently, in the evaluation system for Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales, the greater the variety of experts involved, the stronger the project team and likely the better the project outcome will come to fruition.

2.2.2 Principle 2: Purpose

Before virtualising cultural heritage, the project's objectives and final presentation should be clear. The overall objectives of the project must fall into one of these following categories: research, conservation and/or dissemination. The virtual project offers an accessibility to all content, be it virtual reconstructions or 3D scans. Virtual archaeology is also dedicated to the democratisation of culture (Ioannides, 2017). Therefore, in the evaluation system for Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales, projects must have a clear purpose and motivation, and the outputs should be democratic and transparent.

2.2.3 Principle 3: Complementarity

Other method and processes utilised for the general management of archaeological resources should not be anticipated to be replaced by computer-based visualisation (virtual restoration should not be expected to replace real restoration, just as virtual access should not replace real access) (Ioannides, 2017). Therefore, in the evaluation system for Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales, virtualisation of the original project should not be utilised as a substitute for project restoration, and cultural heritage should be afforded equal weight to digital heritage.

2.2.4 Principle 4: Authenticity

The historical features, buildings, and environments should be

14 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

well respected when creating the virtualised heritage replica. This principle must be permanent, or the virtual heritage will become a figment of the imagination (Ioannides, 2017). Therefore, in the Case studies of extended reality (XR) at different scales in cities evaluation system, digital restoration projects must respect and reflect reality. However, this principle is not relevant to the creation of design-based projects.

2.2.5 Principle 5: Historical Rigour

The approach of virtualising cultural heritage must be rigorous and authentic. Any form of digital heritage must be corroborated by historical research and archaeological documentation (Ioannides, 2017). For digital restoration projects, the Case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales evaluation system should support a meticulous historical research process. However, this principle is not relevant to the creation of design-based projects.

2.2.6 Principle 6: Efficiency

The point to efficiency in the virtualization of legacy is to use less resources to continuously generate more and better outcomes. (Ioannides, 2017). Therefore, in the evaluation system for Case studies of extended reality (XR) at different scales in cities, it is necessary to designate an appropriate technical mechanism to manage the project's input.

2.2.7 Summary for evaluation system of case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales

The following conclusions may be drawn from the aforementioned principles. Firstly, the greater the variety of experts involved in the evaluation system of extended reality (XR) case studies at different urban scales, the stronger the project team will be and the more likely the project outcome will be successful. Second, the project should have a distinct objective and strong motivation, and its outcomes should be democratic and transparent. Thirdly, the virtualisation of the original project should not replace the project's restoration, and cultural heritage is essential as digital heritage. Fourthly, the process of a digital restoration project ought to be supported by an exhaustive historical research process. Fifthly, digital restoration projects must respect and reflect reality. Sixthly, it is necessary to designate an appropriate technical mechanism to manage the project's input.

15 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

A research area that is entirely technology-driven can also be risky (Çöltekin, 2020); thereby, the article establishes an evaluation system of case studies of extended reality (XR) at various urban scales by critically introducing The Seville Principles.

2.3 Cases for different urban scales Review

This section of the dissertation will review case studies of the application of extended reality (XR) at various scales in urban environments. This dissertation seeks to discuss the application of extended reality technology at various scales. Therefore, the sampling of cases is crucial and challenging. First, the scale of the city is subdivided from large to small (Figure 1) into a whole city, a district of the city, a public area, a building, and a monument. It is then a matter of selecting cases that correspond to each of these five scales.

2.3.1 City

In 2016, the Belgian city of Ghent launched a project to engage citizens in a digital 3D reconstruction of the city's historical environment. The community created the project, which is not financially backed by the city administration. Ghent is a pioneer in the 3D city modelling. Digital 3D models of the city were used in urban design, planning, and urban revitalization as early as the 1980s. They experimented with virtual reality in the 1990s and 3D GIS and digital mapping a few years later (Matthys, 2021). The city will serve as an illustration of the application of immersion technology at the scale of the entire city, with citizen participation.

2.3.2 District

In 2010 and 2011, two devastating earthquakes struck the New Zealand city of Christchurch, ruining more than 900 buildings. During the earthquakes, a third of the city centre complex was torn down. It is difficult for residents to reimagine what the city and its significant historical landmarks would have looked like in the past. CityViewAR is a smartphone augmented reality (AR) software for outdoor use. The app provides an AR visualisation of the city within the city limits (Lee, 2012). A district of the city is visualized as an example to demonstrate the application of augmented reality (AR).

16 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

2.3.3 Public area

During the Japanese colonial period, two important cultural heritage sites in Seoul, Gwanghwamun (the main gate of the Royal Palace) and Hyoch'ang Park (a city park containing the graves of famous people), were heavily damaged. There have been efforts made by the Korean government to restore these two cultural heritage sites, but there are limitations to those attempts. It was necessary to demolish and relocate portions of the cultural heritage, necessitating the spatial transfer of the heritage. Cultural heritage is digitally restored and reproduced in its original form using augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) to restore the city's sense of site (Youn, 2021). In a public space, the cultural heritage will serve as a model of the use of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR).

2.3.4 Building

Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni in Milan, Italy, was converted into a museum after the death of the renowned 20th-century architect Achille Castiglioni. Researchers virtualised the entire site utilising 360° panoramic photographs and virtual reality (VR) (Bolognesi, 2020). The museum will serve as an example of virtual reality (VR) implementation in a building.

2.3.5 Monument

The fountain in St. George's square in Valletta, the capital of Malta, is a notable city landmark. 1746 saw the redesigning and relocation of the fountain. Researchers were permitted to virtualise the results at the original St. George square (Scianna, 2020). This fountain will serve as an example of the use of augmented reality (AR) and virtual reality (VR) for a landmark, or a monument.

2.4 Conclusions

In order to better analyse the use cases of extended reality at various urban scales, a precise definition of extended reality technology is furnished. Due to the absence of theory in the evaluation of different scales of extended reality applications in cities, this thesis ingeniously introduces international virtual archaeology principles to broaden the evaluation perspective of extended reality technologies and to establish an evaluation system for extended reality applications. By elaborating on the division of urban scale, the cases are placed in five distinct urban spaces

17 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

and discussed separately. Entering the city's various scales, cases that were once separate converge into unity. Thus, a new area of discussion is opened up for the analysis of the application of the technology for extended reality. Through this research design, the application of extended reality technology and urban space is revealed to be closely linked. This enables the analysis of the use of extended reality at various urban scales.

Therefore, following the clarification of the research gap, the research perspective, and the research methodology, the present condition of the application of the extended reality technology at the urban scale and the contribution the extended reality technology bring to the city can be established.

18 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 2:Extended reality applications Review

Figure aerial, Meskens

Figure aerial, Meskens

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale 19 Extended reality in the city EXTENDER REALITY-CITY

4. Gent

(2020).

3.1 Background

After Paris and London, Ghent (Belgium) was the third largest city in northwestern Europe, surpassing both Amsterdam and Brussels. Today, Ghent has approximately 260,000 residents. In the 1980s, Ghent began utilising CAD, GIS, and 3D modelling for urban planning and development. Ghent was a pioneer in the domain of 3D city modelling. The city of Ghent initiated a project in 2016 that encourages citizen engagement in the digital reconstruction of the city. This experiment demonstrates an aspiration to explore the 4D city in addition to the 3D digital reconstruction of the city. A large number of non-professionals utilized free 3D software and game engines to explore the possibility for 3D and 4D online interaction (Matthys, 2021). This project details the 3D modelling of a 4D animated spatial time machine (AniSTMa: a 3D model of the city that includes the dimension of time). Prior to this project, Ghent had extensive experience with 3D city modelling. In 2008, Ghent was the first city in Belgium to establish a 3D Team, which developed and coordinated 3D applications for all municipal departments. Years of innovative 3D (re)search earned them the funding from the EFRD innovation programme (European Fund for Regional Development) from 2009 to 2015. In 2009, the inner city was scanned with Lidar 3D and vectorized into a large-scale 3D dataset. In 2014, the entire city was made available in LOD2 CityGML format. A lot of specialist work has been done based on this model. There have been no funds for the development of new 3D-based apps since 2015. (After the EFRD funding). Consequently, the decision was made to utilise collaborative 3D modelling (Matthys, 2021). This is an example of a large-scale, public application of extended reality technology.

3.2 Process

In 2012, as part of the EFRD initiative, the "My House, My Dream" children's competition was held (Matthys, 2021). During the event, 10 children were selected from 100 to partake in a week-long 3D workshop with 10 MA students in architecture. The 2016 cocreation of the "3D city game Ghent" was inspired by the previous project. Members of the public were invited to use the open 3D data to develop creative 3D visions of their local environment. Some 3D concepts can motivate municipalities to realise them in the real world. Unrealised fantasy projects can be displayed in a virtual exhibition that presents ideas for the future of the city in 3D

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale

20 Extended reality in the city

online or through VR/AR. The project attracted individuals ranging in age from 7 to 80 years old. Ghent-based 3D experts provides a brief presentation on digital 3D drawing to the first participants. In subsequent sessions, citizens with greater expertise in 3D modelling went on to teach beginners how to draw in 3D. The city of Ghent also invited students with knowledge of game engines to inform the public about their use. This became an unprecedented collaboration between citizens and government employees. Most individuals appear to lack knowledge and experience. They were in contact with the group's experts (Matthys, 2021). Different groups had different interests and used different techniques. However, the results of these exploration are summarised in a unified way in this project.

3.3 Technology

A group of participants wished to revive the history of demolished (or destroyed) culturally significant buildings in this affluent city. The group visited the city archives and studied historical drawings and books in order to reconstruct the legacy. The creation of a digital 3D game or gamification necessitates at least three roles: 3D modellers, programmers, and storytellers. These responsibilities were performed by citizens. Some of them use specific 3D modelling software (Sketchup pro, Blender, 3D studio max, Z-brush, Cinema 4D). Unity is programmed using C# or JavaScript. Some used GitHub to collaborate on programming. The storytellers (those in charge of the scenario) created a story in MSWord. Slack was used to track (historical) information regarding 3D projects, while Trello was utilised to track tasks. PlasticSCM, a collaboration programme, was used to simultaneously design and code in the same project. The project did not utilise the BIM platform for collaborative work because the software is not free and is difficult to use for non-specialists. In data, the city's model data will employ open 3D data (In 2015, the City of Ghent published open 3D data online). Sketchup users can swiftly create simple 3D models in data exchange without having to work in a 3D city model environment. If they have a Sketchup Pro licence, they can import DWG files into Sketchup and save them as SKP files to share with other participants. Sketchup drawings are exported in DAE format. Professionals in 3DStudioMax convert DAE files to 3DML files (in the 3D viewer) and FBX files (for the game engine Unity) after performing a quality check (Matthys, 2021) Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at

21 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 3:

an urban scale

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale

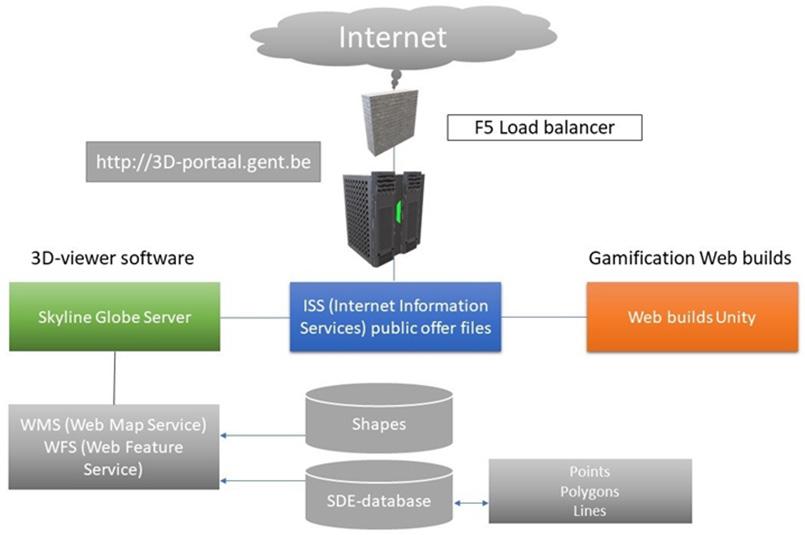

Figure 5.Data exchange from open 3D data over Sketchup to a 3D web viewer and Unity (Matthys, 2021).

In the process of creating the game, the Sketchup designs produced by the general public were imported into the 3D game engine Unity, which also contains files from Blender and Cinema4D. They used Sketchup 3D repository and Unity Asset Store assets to construct the building's surroundings (trees, vegetation, street furniture, animals). Interning students helped participants animate 3D models in Z-brush, Blender and 3D Studio Max. Some inexperienced creators incorporate code into animations. To construct the 4-dimensional web, the team purchased new servers and licences for Skyline Globe and set up servers to manage the different datasets (Matthys, 2021).

Figure 6. Configuration of the Skyline Globe and Unity Web build server (Matthys, 2021).

This set of 3D co-creation tools and systems is created to facilitate the various groups in completing their research projects. Each

22 Extended reality in the city

project can also be discussed in 3D environment and presented in virtual reality.

3.4 Achievements and evaluation

A combination of free 3D software, historical research, game development, and municipal server infrastructure could be used to construct an animated spatial time machine (AniSTMa). The collaboration among the public, government officials, ICT city partners, and students has delivered fruitful result. The entire project relied entirely on public spontaneity and did not involve a large number of experts. At the beginning of the project, professional staff provided some guidance to the public and offered support and assistance with equipment and software. Throughout the project duration, the public had to acquire knowledge on modelling and game engine independently. Therefore, considering this event in terms of Interdisciplinarity, it can only be inferred that the participants were sufficiently diverse and spanned a wide age range. Only a few professionals were involved in the project, and the outcome was not so much a high level of extension technology application as it was public participation. Important aspects of the project encompass the co-creation of the work and bringing the development of an extended reality application closer to the public. The team has ready access to open city data and has benefited from Ghent's early years in the field of 3D city modelling. The project's achievements can be presented to the public in the form of VR and AR games. The results of the gamification also include the participation of historians from city archives (or folklore societies) who provide information on lost buildings. This is an excellent example of Historical Rigour, but the ambitious goal of creating a model of the entire city with information about time was not fully attained at the outset of the project. Due to the pro bono nature of the project, neither financial support nor obligations were imposed on the participants. Consequently, some of the groups' efforts were in vain because participants abandoned the project before their completions (Matthys, 2021).

From the perspective of the application of extended reality-related technology in the entire urban dimension, the most important aspect of a project out of purely public interest is to bring the technology closer to the public. For a real city-scale application of extended display to be completed, substantial financial backing or Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale

23 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 3:

the participation of a major corporation would be required. Due to their limited capacity, a large number of inexperienced individuals actively participated in this project but were unable to achieve the goals that were established at the outset. Therefore, there is still a need for a large number of professionals for the large-scale application of extended reality technology. During this period of rapid development of augmented reality, the development process should not be considered in isolation from the application. Incorporating a diverse range of individuals from various backgrounds into the development of extended reality is itself an application of the technology.

Chapter 3: Ghent, Belgium: A 4D city created by multiple partners at an urban scale

24 Extended reality in the city

EXTENDER REALITY-District

Figure 7. the 22 February 2011 earthquake struck Christchurch, It shows the city's CBD enveloped in a cloud of dust. Needham, (2011). 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Figure 7. the 22 February 2011 earthquake struck Christchurch, It shows the city's CBD enveloped in a cloud of dust. Needham, (2011). 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

25 Extended reality in the city

Chapter

4.1 Background

In September 2010, Christchurch (New Zealand) was hit by a 7.1 violent earthquake, followed by over 10,000 aftershocks, completely distorting the city's landscape. In February 2011, the city experienced its most destructive earthquake to date, destroying more than 900 insider city buildings. Having ruined one third of almost a third of the city centre ruined by the two major earthquakes, it is difficult to recollect the city's original appearance as well as significant historical landmarks that have vanished (Lee, 2012). With the AR technology, visitors can consider the city as it could be prior to and after destructive earthquakes. The mobile AR app CityViewAR, it demonstrates building models from the original locations. This app is intended to serve as an outdoor AR data explorer of earthquake-related geographical data in Christchurch (Figure 8). Although history records as well as are plenty of the buildings, a number of the information is uneasy to access for the buildings are scattered and not organised in a location-oriented manner. The purpose of its function is to collect this information, reorganise it as a geo-located concepts, and lead it to a more opened approach to visit via modern personal information technology, thereby facilitating people in comprehending and remembering the earthquake-damaged historic sites. In addition to providing access to building information, CityViewAR allows users to see the building as it once stood on the site (Lee, 2012). This is an exemplary application of extended reality technology in a district.

4.2 Process

Based on the problems faced by the city, the development team embarked on the development of this application. The New Zealand Human Interface Technology Lab in University of Canterbury in New Zealand was entirely responsible for the entire development process. During the course of its development, the app was presented at two major events and received feedback. The app has since been made available for free download on the Android Market. In April 2012, after completing the app's development, the development team launched an online survey to collect user feedback. The group then conducted an experiment to determine whether the AR elements enhanced the user experience. The experiment enlisted 42 participants, consisting of 15 women and 27 men between the ages of 13 and 51. The 200-meter-long

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Figure 8. CityViewAR s displaying virtual construction sites in AR view(Lee, 2012).

26 Extended reality in the city

Cashel Street was chosen as the test site. Before the earthquake, there were approximately 20 buildings on this street, now only 7 remain. The development team also devised a questionnaire for the use of the app. This experiment contains the comparison of user’s responses while visiting from CityViewAR with the AR between its interface is on or off . Consequences demonstrate AR interface enhances the user experience as a browsing interface and a content viewer.

4.3 Technology

The CityViewAR application has been progressed according to Google Android operation system as well as software developing kit (Lee, 2012). The application supports various Android 2.2 and later smartphone and tablet devices and includes the requisite sensors (camera, GPS, electronic compass as well as accelerometer). Google Maps API service provided the geographic map data, while the Google Sketch-up software was used to develop and register the 3D building models. The app includes an SQLite database for storing POI data, and 3D architectures are depicted using with an internally progressed mobile outdoor AR framework according to Android SDK and OpenGL ES API (Lee, 2012). The most recent edition version of the app (v1.5) contains more than 110 architectures with 3D models as well as approximately 20 panoramic images of many positions in city center of Christchurch (Lee, 2012). The application's design starts with a map view that is easier to access regardless of the user's location (Figure 9). Using the icons in the lower-right corner of the screen, users are able to easily switch between the available browsing views.

The application superimposes building information on a live scene background in AR view mode to display virtual content on the phone's screen. CityViewAR utilises the building's original threedimensional (3D) model to enable users to see virtual building on location. Users may co-act with AR view using their phone's touching screen interface. Touching a virtual building or icon in AR setting will display a pop-up with a concise depict of t scene and other icons linking to additional content like text, pictures, audio, as well as video clips (Figure 10) (Lee, 2012). For the approximately one hundred buildings now featured in the CityViewAR program, there are three sorts of content: textual descriptions, images, and panoramic pictures. The detailed viewpoint (Figure 11) offers

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Figure 9: The Map view displaying POIs as icons on the map (Lee, 2012).

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Figure 9: The Map view displaying POIs as icons on the map (Lee, 2012).

27 Extended reality in the city

details of building, containing data like history facts, and distance from tuser's current position (Lee, 2012). While the majority of the application's POIs are buildings, some of them are panoramic locations. When the user selects this type of POI, a 360-degree immersive panoramic image is displayed on the screen (Figure 11). The user is able to pan viewing direction by dragging on the touch screen or by tapping a button to activate motion sensor (Lee, 2012).

4.4 Achievements and evaluation

The project was developed by a team of experts using proven development techniques to produce an outstanding presentation. The app combines maps, building information, and augmented reality technology to depict Christchurch prior to the earthquake. The project's initial goal was to use AR technology to restore the houses destroyed by the earthquake; however, though not all of the houses were digitised, the app was sufficient to help city residents record the city's history. The project's results were also sufficiently open for the app to be made available for free on the Google Apps marketplace. As the earthquake's impact was so catastrophic that a complete physical restoration of the city could not be justified, the use of augmented reality technology became justified. The project's AR presentation is primarily comprised of 360-degree photographs as opposed to extensive modelling; 360-degree photographs are a good record of building textures and scenes but lack interactivity in comparison to building models. However, there is no doubt that the use of 360-degree photographs for localised urban extended reality applications is an effective and relatively inexpensive solution. And according to the development team's research report, panoramic photos are quite popular. Given the limitations of AR technology and networks at the time, panoramic photographs were indeed the most effective way to present them. Due to the rapid iterations of AR technology and the burgeoning demand for AR experiences, panoramic photographs are not the final form of AR presentation. Considering the user's device and making it easier for the user to access AR, a cost-effective and efficient solution should be shortlisted for the implementation of augmented reality in a city.

Figure 10: The popup dialog displaying the description of a chosen virtual architecture in AR view (Lee, 2012).

Figure 11: Views for distinct kinds of content: Detail view and Panorama view (from top to bottom) (Lee, 2012).

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

Chapter 4: Christchurch, New Zealand: A virtual city restoration after a major earthquake

28 Extended reality in the city

EXTENDER REALITY-public area

Figure 12. the square in front of Gwanghwamun, BBC NEWS (2019).

Figure 12. the square in front of Gwanghwamun, BBC NEWS (2019).

29 Extended reality in the cityChapter 5: Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts within cities

5.1 Background

The restoration of urban cultural heritage will inevitably conflict with inner-city development. The protection and utilisation of history sitesof old urban areas is one of the central themes of localized revitalization in Korea (Youn, 2021). From the year 2000, the Korean government in Seoul has embarked on a process of urban renewal oriented towards the preservation of historical and cultural values. The Urban Renewal Act was enacted in 2010 in Korea, and urban renewal and preservation of cultural heritage were integrated. But trials to extend and repair initial values and forms of city heritage positions will unavoidably result in space conflicts with neighbouring city fabric, commonly evolving in a manner that is incompatible with the preservation of urban heritage (Youn, 2021). To develop cities, either a radical economic logic or a cultural logic can only be a one-sided affair. Applying extended reality technology to urban heritage conservation and restoration may alleviate such a dilemma (Youn, 2021). The restoration of Gwanghwamun, Hyoch'ang Park's Tombs and Shrine in Seoul is an example of this conflict and the use of augmented reality in an urban public area. The application of extended reality technology is concentrated in the project Don˘uimun; therefore, this project will be the focus of the analysis.

5.2 Process

Gwanghwamun and Hyoch'ang Park were important local features during the Joseon dynasty, but they were severely damaged during the Japanese colonial era. The Korean government has attempted to restore these public spaces in an effort to restore their local character. However, the restoration has major limitations due to numerous practical considerations. Both the renovation of Gwanghwamun's platform and the relocation of Hyoch'ang Park's shrine, which involved heritage-based spatial transformations, clashed with the surrounding urban buildings. The digital restoration of the Don˘uimun (the west gate of the Jos˘on Dynasty's city wall) is an illustration of reconciling conflict through recreating senses of place in the virtual realm and stimulating public's culture memory via presentable assets (Youn, 2021). The restoration of Don˘uimun through the use of extended reality technology is a bridge to ease spatial contradictions. Don˘uimun is the westernmost of Seoul's four gates. The gate has a lengthy past and was erected in September 1396. Nevertheless, the gate

Chapter 5: Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts within cities

Chapter 5: Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts within cities

30 Extended reality in the city

was demolished in 1915 during the Japanese development of Kyongsang (Seoul) and the development of the tram (Figure 13).

In 2009, the government of South Korea in Seoul announced a plan to restore the West Side Gate by 2013. Since then, conflicts have arisen within the urban space, such as disputes over the budget, land compensation, and the design of the architectural prototype. As the West Gate is a major thoroughfare in the city, the restoration project will result in years of traffic congestion. In 2019, 104 years after the gate was demolished, the Korean government decided to digitally reconstruct the gate. This digital restoration plan is easily accessible to the public. Near the original location of the gate is a small museum with a VR experience. Through a headmounted monitor, visitors can appreciate the digitally restored West Side Gate. In addition, the Korean government has developed an augmented reality app called Don˘uimun augmented reality. Visitors passing by the original gate can view augmented reality images of the restored gate on their mobile devices (Figure14).

5.3 Technology

The digital restoration of the West Gate in Seoul uses relatively advanced extended reality technology. Although no information was provided regarding the development of this system, it is evident that the technology is a continuation of the development of the two cases in Belgium involving Ghent and Christchurch. In addition to employing modelling technology and game engines, the digital city gates presented in the VR experience must also make use of this technology. The development of the mobile application must also be based on the Android or iOS development framework. Compared to Ghent and Christchurch, the digital restoration and scene reproduction of the entire city gate appear to be a meaningful improvement. This case also encompasses innovative applications for extended reality technology as a technical attribute. Rome Reborn exemplifies the use of VR and AR to restore cultural heritage. Rome is an enormous museum, whereas Seoul's urban heritage is stored within a rapidly developing metropolis. Even though South Korea is not the first country to implement this strategy, it advances the digitization of urban heritage. The restoration of the Seoul gates can be described as the concluding application of extended reality technology. The entire project is presented to reflect the latest developments in the application of extended reality technology.

Figure 13. (a) Don ˘ uimun before destroyed estimated early 1900s. Used with permission from Ref. Figure13.

Figure 14. Field visits :(a) virtual reality experience halls with visual gates and urban landscapes in the Jos˘ on era;

(b) AR of the position and shape of "Don ˘ uimun" that is confirmed by mobile phone (Youn, 2021).

Chapter Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts cities

31 Extended reality in the city

5:

within

5.4 Achievements and evaluation

The whole project was initially driven by a government initiative, and it is endorsed by sufficient financial and technical resources. In the initial plan, the Korean government attempted to physically restore the demolished gate. However, due to competing interests, the initial intent was not carried out. Digital restoration, a compromise solution, was implemented. The success of the digital restoration of the gates can be attributed to the strong financial backing of the Korean government and the development of extended reality technology. According to government estimates, the physical restoration of the gates would have cost $84 million, while the digital restoration using augmented reality technology would have cost only $420,000. (Youn, 2021). This also demonstrates the economic value of digital restoration for the restoration of urban heritage. The results of the project are opened in public buildings throughout the city for free public viewing. Additionally, visitors are able to utilise their mobile facilities to co-act with the AR display. By restoring the city gates, the project evokes the collective memory of the city's residents and enhances the local identity of the modern city without altering its urban fabric. Nonetheless, it is regrettable that the digital restoration of urban heritage alone cannot entirely replace the value of urban heritage. The digital heritage does not enhance the real urban environment. In conclusion, the digital restoration of Seoul's West Side Gate has yielded positive results, but there must be a balance between urban preservation and urban development. The usage of extended reality technology for digital restoration of urban heritage in public urban space should make proactive use of existing experiences and cutting-edge technologies. Additionally, innovative applications of extended reality technology should also be explored.

32 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 5: Seoul, Korea: Using immersive technology to mediate spatial conflicts within cities

Extended reality in the cityChapter 6: Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 15. the interior space of Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni, Castiglioni (2013).

Extended reality in the cityChapter 6: Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 15. the interior space of Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni, Castiglioni (2013).

33

EXTENDER REALITY-Building

6.1 Background

In recent years, art and cultural institutions have begun to recognise the immense potential that extended reality technology offers to augment museum visitors’ experiences. With the development of extended reality technology, new types of art and cultural venues, led by ViMM (Virtual Multimedia Museum), have augmented the museum genre (Bolognesi, 2020). After the death of the renowned Italian architect and designer Achille Castiglioni, the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni was transformed into a museum, and the entire building was opened to the public in 2006, with the consent of his heirs. The Achille Castiglioni Foundation is responsible for classifying, archiving, and digitising the manuscripts, documents, books, and periodicals related to Achille's various projects throughout his lifetime. This space will also feature a number of the designer's most renowned works, which are housed in the museum (Figure 16). The entire area stands for a small Italian museum organization, quite different from the grand museums.

The museum as a whole must cover its own expenses and is responsible for its own promotion. However, this small institution is supported by numerous admirers and various companies, such as the Achille Castiglioni Foundation, that are enthusiastic about digitising the museum (Bolognesi, 2020). This small museum digitisation project is a case study in the use of extended reality technology on an architectural scale.

6.2 Process

This small museum's digitisation is divided into two virtual projects. Specifically, the first project will virtualise the entire interior of the building utilising 360-degree panoramic photo format. The second project is an immersion VR experience progressed for Oculus Rift. Development team prepared tripods, camera heads, and a BLK360 laser scanner for both projects. On top of this, the development team devised a detailed workflow for the projects. The project was scrutinised, a photo data set was acquired, and the materials for panoramic photographs were collated. The material was then stitched together to create the finished 360-degree panorama. The virtual interactions were then designed to facilitate the completion of the first project. Using laser scanning technology, the development team will first digitally scan the room for the second project. The collected point cloud data will then be processed. Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Chapter 6: Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 16. Stanza dei Prototipi, Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni. Maria (2020).

34 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 6:

The entire building's model will then be refined. Last but not least, a game engine will be introduced to develop an immersive VR experience. The development team carefully compared alternative VR technologies. The final decision was to apply a Slide-on HMD to visualise virtual travel. The development team selected an Oculus Rift device for the VR display in order to evaluate the VR effects (Bolognesi, 2020).

6.3 Technology

6.3.1 Project1: 360-degree panoramic photos

The incorporation of 180° x 360° photographs into the virtual tour of the museum will facilitate and encourage more museum visits. The development team specified seven photo dataset collection points based on the spatial characteristics of the interior of this small museum: the external atrium, inlet region, mirror room, meeting room, drawing room, as well as prototype room (Bolognesi, 2020). Once data collection points had been determined, the development team utilised a Canon EOS 70D to collect the photographs. The camera was rotated in a regular pattern and 36 photographs were taken at each collection point to complete the task (Figure 17). A 180° x 360° panorama was then created for the virtual tour by optimising and trimming the photos together (Figure 18).

Figure 18. Panoramic picture of “Stanza dei Prototipi” (Bolognesi, 2020).

Figure 17. Shooting Technical Scheme (Bolognesi, 2020). Italy: The Virtualisation the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 17. Shooting Technical Scheme (Bolognesi, 2020). Italy: The Virtualisation the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

35 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 6: Milan,

of

After completing the collection and collation of data, the development team used 3D Vista Virtual Tour Pro to design a virtual tour of the entire space. In this system, the interactive virtual arrows on the floor serve as the primary means of navigation throughout the virtual space for the visitors. By moving to the left and right, the visitor can observe the entire interior space (Bolognesi, 2020). The space's exhibits are labelled with basic information that can be viewed by visitors (Figure 19).

6.3.2 Project2: Interactive VR experience

The second project, which involved laser scanning, scene modelling, virtual reality development, and interaction, was more complicated than the first. This project's objective was to create an immersion VR experience for the Oculus Rift and to digitise the entire structure. Utilizing a laser scanner, a digital survey of the museum's interior was conducted in order to collect the necessary data for its digitisation (Figure 20). The scanned data constitutes a point cloud in Cartesian coordinates. The development team used a Leica BLK360 laser scanner for this digital survey. This laser scanner has the advantages of being economical, light weight and it scans fast. The laser scanner can be applied to upload data directly to an iPad app, which can then be used to upload information to CAD, BIM, VR as well as AR related usages (2020).

After obtaining the point cloud data for the interior of the building, the data is imported into Rhinoceros, and used to refine the model of the entire building space (Figure 21).

Figure 20. The point cloud details (Recap) (Bolognesi, 2020).

Chapter Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 19. Virtual tour, view of the meeting room with interactive elements (Bolognesi, 2020).

Figure 21. Workflow for modelling architecture components (Rhinoceros) (Bolognesi, 2020).

Chapter Milan, Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 19. Virtual tour, view of the meeting room with interactive elements (Bolognesi, 2020).

Figure 21. Workflow for modelling architecture components (Rhinoceros) (Bolognesi, 2020).

36 Extended reality in the city

6:

After modelling the built environment in Rhino, the digital model of the museum is exported to Unreal Engine in fbx format. Detailed textures in virtual building sceneries can be augmented in the game engine (Figure 22). Through various data and parameter settings, the game engine can recreate the materials and colours of the buildings as precisely as possible to optimise the realism of the virtual environment and render it ever more immersive.

After modelling the built environment in Rhino, the digital model of the museum is exported to Unreal Engine in fbx format. Detailed textures in virtual building sceneries can be augmented in the game engine (Figure 22). Through various data and parameter settings, the game engine can recreate the materials and colours of the buildings as precisely as possible to optimise the realism of the virtual environment and render it ever more immersive. The Achille Castiglioni Foundation provided invaluable guidance during the development of VR scenes. The team of developers decided to recreate as many of the building's objects as possible in the virtual environment, and added a number of interactive elements to the virtual space, such as drawers that can be opened (Figure23).

Figure 23. In the foreground, the interactive box (labeled with phrase “prototipi Gibigiana”) and the open drawers (Unreal Engine) (Bolognesi, 2020). Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

Figure 22. Material Editor (Unreal Engine) (Bolognesi, 2020).

Figure 22. Material Editor (Unreal Engine) (Bolognesi, 2020).

37 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 6: Milan,

6.4 Achievements

The entire project is a complete digitisation of the entire building space from both a 360° panoramic photo and a VR immersive experience. The result of the project is an open-access database of the building, which enables the permanent preservation of the museum's historical memory and legacy. The simultaneous existence of the building's virtual scenario and physical space reflects the complementary nature of architectural heritage conservation. The Achille Castiglioni Foundation assisted with the digitization of the building space. In addition, the development team's professionalism was vital to the realisation of the overall project outcome. The final VR and 360° panoramic photos reflect the building's original spatial relationships. This includes digitising the interior objects of the building, making the entire virtual space more immersive. The team's development process is an exact recreation of the digitalization of a modest structure. Two architectural virtualisation paths were chosen throughout the case to explore the application of extended reality technologies at building scale, from the simple to the complex. This case study is a meaningful reference for the building-scale application of extended reality technology.

Chapter Italy: The Virtualisation of the Studio Museo Achille Castiglioni

38 Extended reality in the city

6: Milan,

Figure 24. the Wignacourt Fountain, Continentaleurope (2016).

Figure 24. the Wignacourt Fountain, Continentaleurope (2016).

39 Extended reality in the cityChapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square EXTENDER REALITY-monument

7.1 Background

Enhancing the accessibility of cultural heritage is a crucial topic in archaeology today. This not only indicates that cultural heritage is inaccessible in physical space, but also that it is only a matter of time before it vanishes for a myriad of purposes (Scianna, 2020). The advancement of extended reality technique can dedicate to preservation of culture heritage (Scianna, 2020).The Wignacourt fountain, now located in St. Philip's Garden in Floriana, was originally situated in Valletta (Figure 25). The monument was constructed in 1625, but Grand Master Pinto redesigned and relocated the fountain in the Palace of Justice in 1746, altering its shape, decoration, and location substantially. Nonetheless, this was not the final location for the monument. Eventually, the fountain was relocated to Floriana's St. Philip Garden (Scianna, 2020). The inquiry of the changes to this monument coincided with an opportunity to extend the application of reality technology. The research team scanned and modelled with the assistance of augmented reality technology to produce a virtual time travel. This project is an example of the application of extended reality technology at the scale of the monument.

7.2 Process

The research team will complete the entire project by collating historical documents, scanning the site and 3D modelling (Figure26).

A thorough historical survey of the object of study was necessary before the fountain could be digitised. The historical documentation was the first step in the entire project. The lack of documentation of the surroundings, on the other hand, posed a number of challenges for the entire project. Through means of a typological study, the research team was able to compensate for the lack of historical resources. The fountain in St. George Square (Figure 27) was built in the early 18th century. The configuration around the entire site had changed significantly, according to a comparison of the on-site environment with historical documentation. A digital restoration of the entire environment is required (Scianna, 2020).

Surveying operations will be undertaken to obtain virtual information on the entire site. The research team compared different techniques depending on the different dimensions

Figure 25. The Wignacourt fountain today located int St. Philip Garden in Floriana (Malta), Scianna (2020).

Figure 26. The scheme of workflow (Scianna, 2020).

Chapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square

40 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square

and geometrical features of the site and the fountain. For the characteristics of the site and the fountain, different scanning methods were chosen. After obtaining the point cloud data, the research team processed it before importing the files into Blender. Finally, the virtual environments created in Blender are imported into Unity to create AR programmes.

7.3 Technology

The technical aspect of the project can be categorized into three sections. The first is to scan the site and the fountain. The second is to reconstruct the scene in 3D. Finally, there's VR, as well as AR app development. TLS equipment, specifically the Faro Focus3D X 150, was used to survey the site with a precision of approximately 1 cm. The team scanned the site six times due to its large size in order to obtain detailed site location cloud data (Figure 28). A digital photogrammetric reconstruction was used to investigate the Wignacourt fountain in Floriana's San Felipe Garden (Figure 29). The research team used a Sony Alpha 6000 DSLR camera to capture sufficient detail and texture of the fountain. The quality of the digital photogrammetry was superior to the laser scan during the small-scale virtual reconstruction of the fountain. The digital photogrammetry point cloud data was more uniform and denser, avoiding the problem of shadow areas not being scanned. The point cloud data from the site and fountain was then imported into the Faro Scene merge file. Autodesk Recap was employed to simplify the point cloud data. The Poisson reconstruction algorithm in Cloud Compare software was deployed to transform the point cloud data into a mesh surface. Finally, in Blender, the mesh model was repaired and refined (Scianna, 2020).

Since Blender features a game engine, it was also leveraged to create the virtual environment. Blender's Verge 3D and WebGL were used by the research team to develop VR. On top of the Android operating system, AR development was accomplished with Java-script and HTML5 tools (Scianna, 2020).

Figure 27. Historical exhibition of the Wignacourt Fountain in St. George's Square in the early 18th century (Scianna, 2020).

Figure 28. Reconstruction of dense cloud in St George's Square from merging TLS scan (Scianna, 2020).

Figure 29. The Dense cloud reconstruction of Wignacourt Fountain from Digital Photogrammetry process using Agisoft Photoscan software (Scianna, 2020).

Figure 28. Reconstruction of dense cloud in St George's Square from merging TLS scan (Scianna, 2020).

Figure 29. The Dense cloud reconstruction of Wignacourt Fountain from Digital Photogrammetry process using Agisoft Photoscan software (Scianna, 2020).

41 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square

7.4 Achievements and evaluation

The project's creators desired to optimise cultural heritage accessibility by incorporating extended reality technology. The research team compared various digital reconstruction tools during the project, settling on the best technical path based on the scale and geometric characteristics of the reconstructed objects. Digital photogrammetry has a notable advantage in terms of digital reconstruction accuracy, and it can produce high-quality point cloud data. Laser scanning is valuable for digitally reconstructing large-scale sites, but it has a number of drawbacks, namely low accuracy and the need for multiple processing of the models obtained. A historical study of the project is deemed necessary for the digitisation of cultural heritage. However, the lack of relevant documentation has a critical impact on the project's quality. Finally, this project is an exemplary reference for the use of extended reality technology at the monument scale, as well as an inspiration for future small-scale applications of the technology.

42 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 7: Valletta, Malta: The Virtualisation of the fountain of St. George square

Figure 30. Spacekit which is a tool for design large-scale AR, Taiuti (2019).

Figure 30. Spacekit which is a tool for design large-scale AR, Taiuti (2019).

43 Extended reality in the cityChapter 8: Conclusion 、EXTENDER REALITY-conclusion

The fundamental objective of this dissertation is to evaluate how immersive technologies are now being used in cities at various sizes in order to contextualise the contribution of AR, VR, and MR technologies to cities in various scenarios. The dissertation addresses the exact definition of extended reality technologies as well as their contemporary applications. To strengthen the system of evaluation of the application of extended reality technologies, the principles of digital archaeology are introduced into the review and analysis of five case studies of extended reality applications at various scales. There are differing technical paths for deploying extended reality technology in various urban scales.

At a city scale, as it is a large-scale application of extended reality technology, the focus should be on the financial investment of the project. This has a key impact on the presentation of the final outcome. Residents are a factor at the city scale and inviting them to participate in the extended reality development process contributes to the proliferation of the technology. The application of extended reality on a district scale focuses more on the street. At this scale, virtualisation of street scenes is paramount, but as it is still a large scale, economic considerations must be taken into account in order to achieve a good presentation. The continuous virtualisation of street information can enable city dwellers in archiving their city's history while also serving as a means of caring for their urban lifestyle. Virtual heritage reconstruction incurs a significant financial cost at a scale of public space, though it is less costly than physical urban heritage restoration. At this scale, extended reality technologies can be used in a variety of innovative ways, such as to resolve development conflicts within cities. Virtual urban heritage, on the other hand, does not serve as a primary means of urban heritage conservation since it does not realistically enrich the physical living space of its inhabitants. The methods of applying extended reality technologies become more diverse at the building scale, and the projects become more finished and better expressed. This scale is ideal for pushing various cutting-edge extended reality technologies to the test. On a monument scale, more refined technical means, such as digital photogrammetry, can be used to apply extended reality. At this scale, extended reality necessitates a greater focus on site information. 8: Conclusion

44 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 8: Conclusion Chapter

At large scales, the application of extended reality technology is more akin to game development. However, since the application in urban environments is more of a public welfare project, the financial return is insufficient to warrant the high quality as a game. The diversity of small-scale applications of extended reality technology includes a variety of technical paths and applications. The use of extended reality is relevant to the conservation of urban heritage at any scale of urban space. This is a reflection of the positive role of extended reality in society. The authors argue that as extended reality technology evolves, the types of urban spaces will become progressively diverse. The boundary between virtual and physical space will become increasingly blurred.

45 Extended reality in the city

Chapter 8: Conclusion

Bibliography

Books

Baruah, R. (2021). AR and VR Using the WebXR API Learn to Create Immersive Content with WebGL, Three.js, and A-Frame. 1st ed. 2021. Berkeley, CA: Apress.

Hovestadt, L., Hirschberg, U. and Fritz, O. (2020). Atlas of digital architecture: terminology, concepts, methods, tools, examples, phenomena. L. Hovestadt, U. Hirschberg, & O. Fritz, eds. Basel: Birkhäuser.

Guazzaroni, G. and Pillai, A.S. (2020). Virtual and augmented reality in education, art, and museums. G. Guazzaroni & A. S. Pillai, eds. Hershey, PA: Engineering Science Reference, an imprint of IGI Global.

Guidi, G.; Frischer, B.; Lucenti, I. (2017). Rome Reborn—Virtualizing the Ancient Imperial Rome. In Workshop on 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures; Fondazione Bruno Kessler.

Ioannides, M., Magnenat-Thalmann, N. and Papagiannakis, G. (2017). Mixed Reality and Gamification for Cultural Heritage. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Ioannides, M., Magenta-Thalmann, N. and Papagiannakis, G. (2017). Mixed reality and gamification for culture heritage. M. Ioannides, N. Magenta-Thalmann, & G. Papagiannakis, eds. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

Kersten, T.P. et al. (2012). Automated Generation of an Historic 4D City Model of Hamburg and Its Visualisation with the GE Engine. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 55–65.

Lichty, P. (2020). Making Inside the Augment: Augmented Reality and Art/Design Education. In Augmented Reality in Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 261–278.

Lynch, K. (1973). The image of the city. Cambridge (Mass.). M.I.T. Press.

Articles

Banfi, F. et al. (2022). 3D HERITAGE RECONSTRUCTION AND SCAN-TO-HBIM-TO-XR PROJECT OF THE TOMB OF CAECILIA METELLA AND CAETANI CASTLE, ROME, ITALY. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives, 46(2), pp.49–56. [Online] [Access on 12th May 2022]

46 Extended reality in the cityBibliography

Extended reality in the city

Banfi, F. and Mandelli, A. (2021). Interactive virtual objects (ivos) for next generation of virtual museums: From static textured photogrammetric and hbim models to xr objects for vr-Ar enabled gaming experiences. International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences - ISPRS Archives, 46(M-1-2021), pp.47–54. [Online] [Access on 12th May 2022]

Bolognesi, C. M., & Aiello, D. A. A. (2020). Through Achille Castiglioni's Eyes: Two Immersive Virtual Experiences. In Virtual and Augmented Reality in Education, Art, and Museums (pp. 283-310). IGI global. [Online] [Access on 12th May 2022]

Chen, M.-H. et al. (2019). Towards VR/AR Multimedia Content Multicast over Wireless LAN. In 2019 16th IEEE Annual Consumer Communications & Networking Conference (CCNC) IEEE, pp. 1–6. [Online] [Access on 12th May 2022]

Chung, N. et al. (2018). The Role of Augmented Reality for Experience-Influenced Environments: The Case of Cultural Heritage Tourism in Korea. Journal of travel research, 57(5), pp.627–643. [Online] [Access on 12th May 2022]