1 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

avenues volume five a publication of the Urban Design Committee (UDDC) of the Washington Chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA|DC) happy - cities

AVENUES, VOLUME 5: HAPPY CITIES

URBAN DESIGN COMMITTEE

AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS, WASHINGTON, DC

MANAGING EDITORS

JANKI SHAH, ASSOCIATE AIA

SAAKSHI TERWAY, ASSOCIATE AIA

KUMI WICKRAMANAYAKA, AIA

PUBLISHED BY AIA, WASHINGTON CHAPTER

421 7TH STREET NW WASHINGTON, DC 20004

AIADC.COM

2023

THE VIEWS EXPRESSED ARE THOSE OF THE AUTHOR AND NOT THOSE OF THE URBAN DESIGN COMMITTEE NOR THE WASHINGTON CHAPTER, AMERICAN INSTITUTE OF ARCHITECTS.

6 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

06 letter from the chair: happy cities by Saakshi Terway

12 provocations

14 urban design and the happy city: on community representation within the public square by Timothy Maher

24 happy! by Greg Luongo & Erin Peavey

42 public space for a privatized individual by Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

50 the lived-in city | happiness in urban form by Dominic Weilminster

58 firmitas, utilitas, venustas no longer by Joseph Mckenley

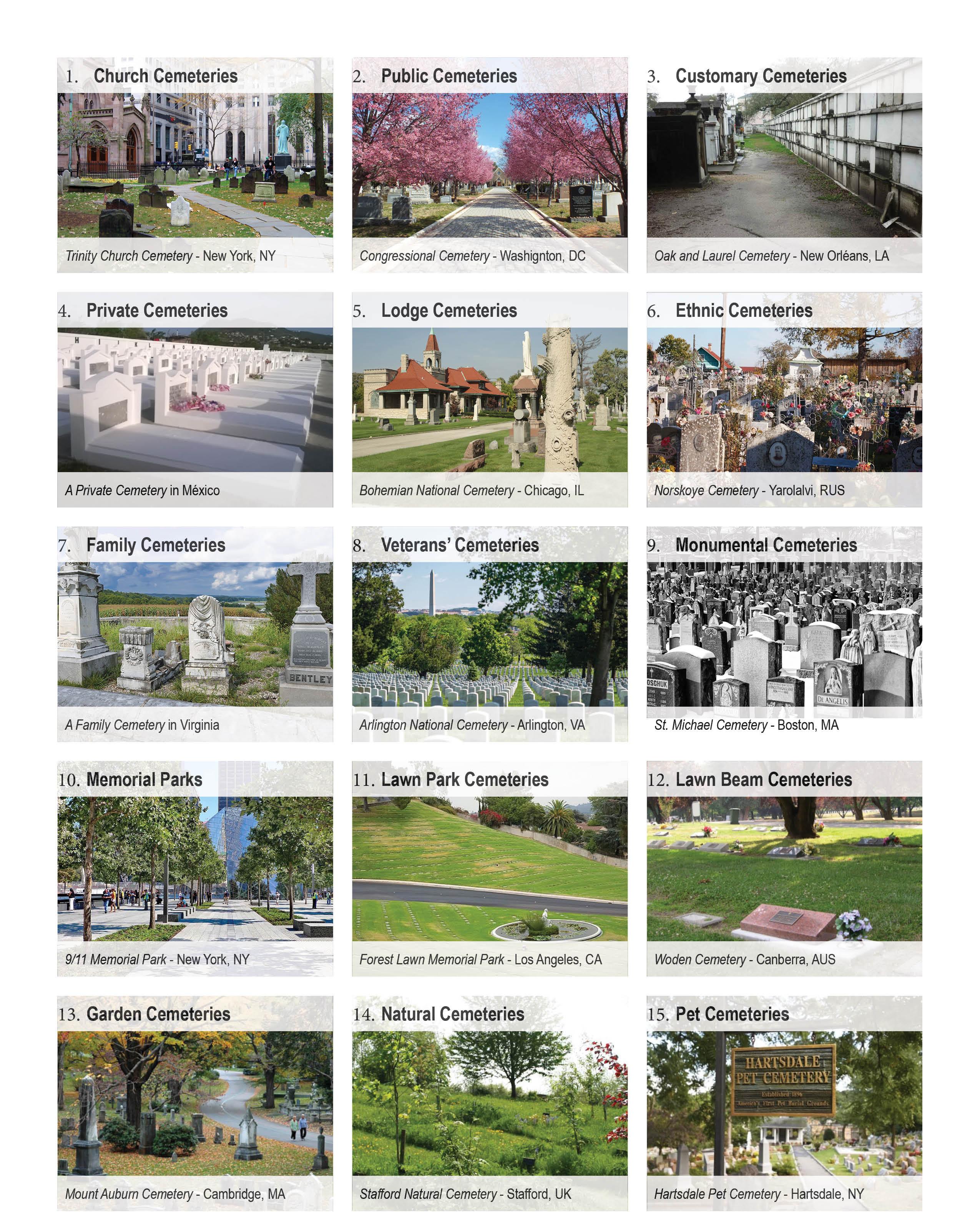

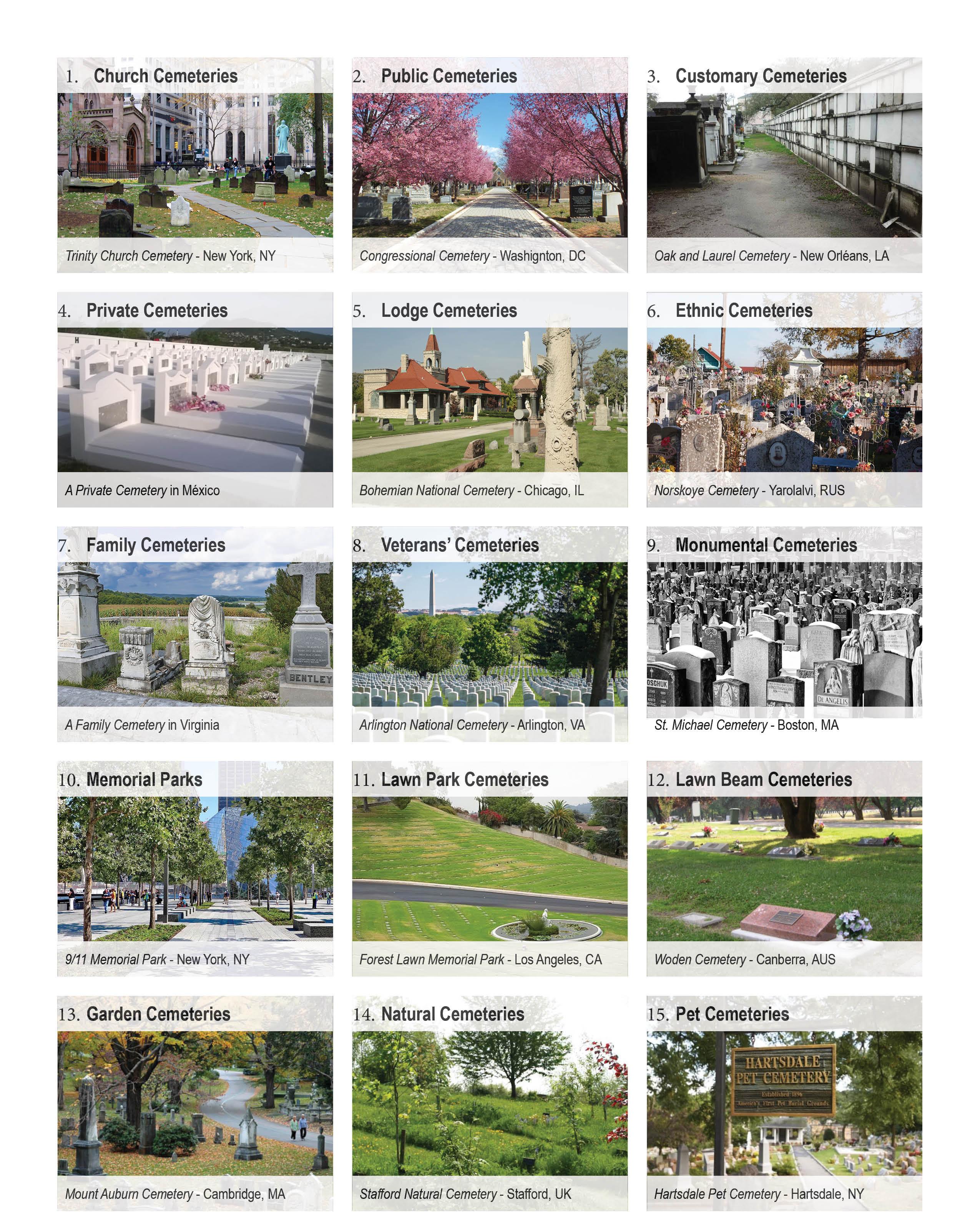

70 metamorphosis: a vision for the urban cemetery of tomorrow by Bradley Benmoshe

by Rita Wu

7 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities contents

86 happenings 88 politics, protest and place, the role of inclusive urbanism in civic activism 90 pdaily city nature challenge 92 rethinking & revitalizing urban parks post covid-19 93 portfolio and resume workshop 94 culture amplifier - ideas competition 96 ideas

DC space

the reconstruction of chinatown in washington

98

by Aaron Greiner & Rishika Dhawan 106

DC

letter from the chair

happy cities

I am delighted to introduce the fifth annual publication of Avenues, the journal of the Urban Design Committee of the American Institute of Architects, Washington DC Chapter (AIA|DC).

Who We Are

Founded in 2017, the Urban Design Committee acts to improve the quality of cities and people’s lives. This mission is supported by our five key goals:

1. Create a Forum to engage other organizations in Urban Design.

2. Raise Public Awareness of the value of Urban Design.

3. Promote Visionary Thinking about the future of cities.

4. Advocate for Public Policy that promotes livability, spatial equity, and environmental stewardship.

5. Develop Allies among architects, planners, landscape architects, stakeholders, and policymakers.

Journal Overview

This journal is divided into three sections.

Section 1, “Provocations”, talks about what authenticity means in today’s context.

Section 2, “Happenings”, highlights the milestone events that were organized within the year to understand authenticity in the city better.

Section 3, “Ideas”, exhibits a collection of competition entries that animate the essence of authenticity.

Happy Cities

This year we focused on the overarching issue: what makes a city happy?

Each year we adopt an openended theme to frame our critical thinking on the challenges we face in urban design. The theme for 2021 was “Happy Cities”. Throughout the year, we looked

at “what makes a city happy” through various lenses of urbanism like community engagement, community development, equity and equality, sustainability, crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED), etc.

Can design make the world a better place? It is often argued that a well-designed space can change lives, and this may be true. Nevertheless, any design is ultimately impacted by the context in which it is placed. Cities are designed spaces embedding past trials and errors, built on layers and layers of context. We, as urban designers, strive to insert ourselves into this amalgamation. Composed of architects, philosophers, investors, artists, sociologists, activists, and citizens, we engage with these contexts, and ultimately—whether we like it or not—we affect lives in our communities and our world.

10 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Cities are magnets for those seeking better jobs and a wider range of opportunities. But increasing urbanization is causing cities to become sprawling spaces without a sense of community. The sustainable development of a city directly impacts human well-being. In terms of happiness, people across cultures, creeds, genders, and geographical regions can find a common ground. Happiness is not just an individual characteristic, but also a community characteristic strongly influenced by social connections, cohesion, and local amenities.

As urban designers, planners, and architects, we know there are techniques that can encourage people to think of their city not just as a place, but as a community shared by all. There is growing awareness that social bonds may be shaped by characteristics of the built and social environment. These social bonds, in turn, may help to overcome community threats that could diminish residents’ happiness and weaken their social cohesion.

What’s Next

If the utopian concept of a happy city has a weakness, it is that it is subjective to every individual’s experiences. As practitioners and passionate urbanists, we must strive to affect positive change in the very real challenges of our time. There has never been a greater need for urban design to be a critical multidisciplinary practice for our city, our nation, and our global community. We invite you to find new avenues for exploration in the text that follows and to join us as a member or collaborator in 2022.

Saakshi Terway, Associate AIA Chair, AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

11 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

provocations

this section challenges our assumptions and explores the meaning and application of our theme HAPPY CITIES

urban design and the happy city: on community representation within the public square

by Timothy Maher, Urban Designer, DC Office of Planning Urban Design Division

JUST WHO IS THE HAPPY CITY FOR?

To actively pursue the notion that we can create the happy city, urban designers, planners, and policymakers must first recognize that our work must elevate participation in the public sphere so that all who desire to be in this space can feel safe and welcome within it. Our work must first be grounded in the ideals of resilience, sustainability, and equity so that people from many disparate backgrounds (cultural, racial/ ethnic, socio-economic) feel their voices have the power to influence how they are governed. This has long been an integral promise of the American experience, spoken of often by the founding fathers, but never seriously contemplated until recently.

One immediate facet of the idea of equity – and where urban

designers and planners play an integral role – is the issue of representation in the public square. Do the members of a community feel like their values are reflected in the physical design of their neighborhood? Can they feel as safe or welcomed in the public spaces they inhabit as anyone else of a different background? Do they feel that if they were to speak up about an issue occurring within that space they would be heard or that frequently marginalized voices would be elevated? These questions form the building blocks for inclusion and belonging in a neighborhood and lay an important cornerstone: If members of a community feel represented, acknowledged, and free to fully participate in the public square, only then have the prerequisites been met for our aspiration to the happy city.

Representation in the public

square is intrinsically important, otherwise the issue of who is memorialized in statuary across the country – and who has access to the power structures that make such decisions – wouldn’t be so heated a discussion at this time. Similarly, we direct a wealth of resources into historic preservation and the creation of historic districts, in part to shape which collective memories or aesthetics are prioritized as neighborhoods ebb and flow over time.

Representation should be so intrinsic to the field of urban design that it ought to make up much of the curriculum of Urban Design 101 courses at universities. But herein lies the challenge for urban planning and design at all levels – how do we engage the whole of a community in such a way as to honestly elicit input on how they want to shape the design of their surroundings?

14 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

UNDERSTANDING ENGAGEMENT AND A NEEDED PARADIGM SHIFT

Over the past several years, the DC Office of Planning (OP) has made several efforts to shift the thinking as to how community members are included in planning efforts. The first of these pilot efforts, organized as part of a grant award by the Kresge Foundation in 2016, was the citywide Crossing the Street program, an effort to use art and culture as a means to bring communities together and begin dialogue with neighborhoods experiencing rapid demographic and social change.

Through outdoor music, art, and cultural performances, tactical urbanism demonstrations, and neighborhood potlucks, dozens of individual events and installations were hosted across the city, all scoped and workshopped with community stakeholders. This effort pushed city planners into the physical space of the neighborhood where they could directly engage community members on what was their turf – to ask questions about what is cherished within a neighborhood and what challenges need to be addressed while physically inhabiting that very space. It became an outdoor forum that better allowed individuals who

have not previously interacted with the Office of Planning before to have an avenue for engagement.

Simultaneously, OP began conducting Public Life Studies as another shift in public engagement efforts. Based on the Jan Gehl idea that direct observation of activity (and inactivity) can provide clues as to the way people use their public spaces, a Public Life Study can better assess how the physical design features of a public square are actually used rather than relying on vague design intentions and assumptions. Following up the direct observations are intercept surveys to provide insight into

15 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Protest at the statue of Confederate General Albert Pike, D Street NW, on who should be represented in the public square, 2017

Photo credit Vision Planet Media

how people perceive the spaces they inhabit and their reactions to various elements within a space. In turn, new or proposed conceptual designs for public spaces can then be improved by understanding some of the myriad ways in which people interact with their surroundings. For example, observations can focus on how users pass through a space, where they opt to linger (whether by themselves or with a group), or by watching for when a wall is just an aesthetic fixture versus when it is used as a bench, footrest, or playground.

TO MOVE FORWARD, WE AS PLANNERS AND DESIGNERS NEED TO RECOGNIZE OUR ROLE

IN IMPROVING COMMUNITY REPRESENTATION WITHIN THE PUBLIC SQUARE. THIS IS A MARATHON EFFORT TO BUILD TRUST AND RECONSTRUCT RELATIONSHIPS WITHIN COMMUNITIES, ESPECIALLY WHERE ECONOMIC SEGREGATION AND DISPLACEMENT HAVE OCCURRED.

Both of OP’s proactive engagement models are light years beyond the standard practice of community engagement that has persisted for decades – a weeknight evening meeting that is typically attended only by those with the free time to – and yet they still fall short of what could be. Though, a

critical shortcoming of the Public Life Study method is that direct observation and surveying of people as they inhabit a space homes in on groups already comfortable in that space and proceeds to set their behavior up as the baseline. What is left unseen (or lesser seen) are groups marginalized in public or those more hyper aware and uncomfortable with being watched or recorded while going about their daily lives.

THE LONG AND INCREMENTAL ROAD TO BETTER COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT

To move forward, we as planners

16 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Left: Crossing the Street events: Okuplaza Fest in Adams Morgan, 2016. Right: See/Change in Park View, 2016.

Photo credit: DC Office of Planning

and designers need to recognize our role in improving community representation within the public square. This is a marathon effort to build trust and reconstruct relationships within communities, especially where economic segregation and displacement have occurred. And while our current toolkit of engagement ideas is improving, it does not yet suggest a flawless solution. On that end, we should consider that each project moving forward can serve as a testing ground for new and potentially inspiring means of expanding our outreach to the members of a community that have yet to give us their time or trust.

A chance for a novel approach to engagement came in 2020, notably during the summer and fall months of the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic when District residents were facing a slew of unprecedented pressures stemming from the public health crisis. At the time, the city was operating under ‘Phase 2’ restrictions that set limits on the interior capacity of restaurants and shops, and mandated physical distancing and mask use in public. With people’s behaviors so intensely altered during the health emergency and safety orders, the direct observation of a Public Life Study was an uncertain endeavor. At that time, however, OP began a series of investigations into the Frank D. Reeves municipal center and its surrounding public spaces

at the intersection of 14th and U Streets, NW.

First, a bit of history. The Reeves Center plays a fairly significant and at times nostalgic role in the memories of many longtime District residents – it was intended in the mid-1980s to help reinvigorate a neighborhood struggling with a lack of investment following the 1968 riots less than two decades prior. The calculated ‘investment’ of a large municipal office building set back from the street to create an expansive front plaza would kickstart weekday activity along the corridor with a thousand daily government workers. These workers would have an immediate need for a variety of surrounding retail spaces, lunchtime diners, dry cleaning, shoe repair shops, and the like. The plan was that this would in turn spur new residential and office development to then induce additional demand for retail in a positive feedback loop of economic vitality and growth and set the course for a self-sufficient and desirable neighborhood again.

In time, the U Street corridor, once the bustling arts and finance center known as Black Broadway in the early and mid- 20th Century, re-emerged as a place of exciting nightlife, flashy retail and restaurants, high-rise residential buildings, and rebuilt historic theaters. Arguments can be made as to whether or not it was the Reeves Center that really did act

as catalyst for the neighborhood (and academics continue to go back and forth on it), but the idea that it played a significant role in revitalizing a Black neighborhood by a Black mayor in the early days of Home Rule is still present in the minds of many long-term residents of the District.

A CASE STUDY ALONG BLACK BROADWAY

One illustration of the microcosm of this re-birth was the 14th and U Street intersection and the adjacent public plaza which has played witness to many spontaneous protests and celebrations over the years as a central gathering space.

On the night that Barack Obama first secured his party’s nomination as a presidential candidate, celebrants including a makeshift drum circle gathered at the plaza in revelry. Similarly, several years later, activists in the Don’t Mute DC campaign purposefully selected the 14th and U Street plaza as a site of protest and demonstration when a white newcomer to the neighborhood filed a complaint in an attempt to shut down a nearby corner store for playing Go-Go music on a speaker from the sidewalk. Events of this nature have a way of gravitating towards the open plaza.A clear challenge to exploring urban design is presented by this cocktail of ingredients:

17 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

18 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Protest at the statue of Confederate General Albert Pike, D Street NW, on who should be represented in the public square, 2017

Photo credit Vision Planet Media

The Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center, view from the southeast.

Photo credit Erkin Ozberk

19 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Activity on the 14th and U Street NW intersection, view from the northwest

Photo credit Timothy Maher

Public Plaza at the 14th and U Street NW intersection, daytime weekday .

Photo credit Timothy Maher

A municipal center built by an important Black political figure in a city with a majority Black population located in a renowned, former Black financial/ entertainment district;

A public plaza and community gathering space for local political protest and celebration; and

The potential redevelopment of a site in a neighborhood that has been experiencing economic pressures that can lead to displacement.

And so for urban designers the question is raised; how can we ensure that any future

development proactively carries and builds upon the shared cultural memories of a space, positively acknowledging the rich history of Black enterprise, while taking note of how residents want to participate in the public square today? And can we address this effectively both meeting the needs of existing residents while also making room to welcome new members to the community so that all can feel represented and coexist within their public square?

As OP embarked on a Public Life Study of the 14th and U Street intersection during the first fall season of Covid, it was clear that

in-person observation would be unreliable (few were behaving normally in public and even fewer were comfortable answering questions from a stranger in a mask) so we resorted to a series of community storytelling and narrative exercises conducted online. During this process, we asked community respondents to expound on their memories of the space, what types of activities do they believe still belong on the site and if they want any new activities introduced. What we got in return was something different than the typical snapshot of pedestrian activity over a single weekend at the site; we received

20 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Columbia Heights Plaza; Though approximately the same size as the 14th and U plaza (~0.3 acres) the plaza in Columbia Heights sees considerably more daily use, much stemming from the fountain and adjacent retailers.

Photo credit Timothy Maher

a broad mosaic of many positive and negative perceptions of the space that spanned decades, told to us from the perspective of the persons witnessing it firsthand. Though it was a cacophony of points of view with many gaps and some events we were unable to corroborate, it did allow us to home in on a sense of collective memory and cultural value of the immediate area.

ON MOVING URBAN DESIGN AND ENGAGEMENT FORWARD

As a case study in improving public engagement, the Reeves Center site is far from faultless. It illuminated for us a novel method of tapping into collective memory that we have only just begun to explore, but fell short in reaching marginalized populations that are not connected to the internet. But if we can learn these lessons and improve our next model, it serves an overall positive purpose.

And as with any planning study, the true challenge of seeking a more equitable representation and a voice for communities within the public square must inspire the work conducted during the design and implementation stages of development. The study is still necessary – we can continue to broadcast these issues so that future participants in this ongoing process can build on top of the information that has already been gathered. Planning and urban

design here can act as planting the seed of an idea, and so OP introduced the following design principles to be considered for any proposals on the site moving forward:

Living Legacy: Recognize the once-in-a-generation opportunity to celebrate and honor the living legacy of a neighborhood steeped in the U Street corridor’s historic link to Black identity, culture, and enterprise. Acknowledge the Reeves Center’s ties to civic activism and the struggle for Home Rule in the District through architecture, urban design, commemoration, and public art and promote Black-owned businesses as principal tenants of any redevelopment.

Public Plaza: Maintain a true public open space along the site by transferring a portion of the private lot for use and ownership by the public. Design an open plaza that prioritizes visual openness, physical access, and comfortable environmental conditions and that reflects the shared values of the District and its people.

Engaging Edges: Prioritize day-today activity, foot traffic and visual interest along the site through site design, architecture, and a curated selection of ground floor tenants with opportunities for outdoor retail or café spaces to the benefit of the surrounding neighborhood.

As we continue to address the role urban designers and planners play in a community’s access to and representation within the public square, we welcome the chance to constantly learn and evolve from past attempts. It is only through the long-term building of community trust that they lend us their voices and guide us to better, more sustainable and inclusive outcomes. It is on us as designers and planners to not turn back when facing sticky problems and instead open our ears to improvement.

21 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

REFERENCES

To follow up on OP’s Public Life Studies and other Placemaking and Public Engagement efforts, check out the following:

Creative Placemaking at OP and the Crossing the Street Project: https://planning.dc.gov/page/creative-placemaking

Public Life Studies at OP: https://planning.dc.gov/publication/guide-public-life-studies-dc

Public Space Activation & Stewardship Guide: https://planning.dc.gov/page/district-columbia-public-space-activation-stewardship-guide

Our City, Our Spaces Guide: https://planning.dc.gov/our-city-our-spaces

22 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

23 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Happy!

By Greg Luongo, AIA and Erin Peavey, AIA, WELL AP, EDAC, LEED AP BD+C, HKS

WHAT MAKES US HAPPY?

To answer that question, we looked to the Nordic countries, which are consistently ranked as some of the happiest places on the planet. And while the reasons why vary, a handful of universal characteristics came up in research conducted by The Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark. According to their findings, seven factors are fundamental to contributing to a sense of happiness:

Health: No surprise here really. If we’re sick, we are generally unhappy. Health is also one of the factors that not only affects us as individuals, but our family and friends as well.

Wealth: This one doesn’t come as a surprise either. Data shows that richer countries and people are simply happier in general. But the important thing to understand

here is the trigger: being without money is the root of unhappiness. If we can’t put food on the table or provide a roof overhead, it causes stress and anxiety. There’s also an interesting factor of diminishing returns when it comes to wealth, where more or excessive wealth does not necessarily have a corresponding bump in happiness.

Trust: This factor is less obvious than money or health. In Nordic countries, foundational trust comes in two forms. First is trust in the state and government, which can come as a result of low levels of corruption, strong governance and democratic institutions, and widespread access to basic services that support well-being. The second is trust in one’s fellow citizens and neighbors. When we can trust our neighbors, we generally have fewer worries — we’re less anxious about theft or threats of harm. Trust just makes

life a little bit easier and more convenient.

Personal Freedoms: There is a strong correlation between the level of personal freedom in a given country and the level of happiness. Beyond civil liberties like freedom of speech and assembly, personal freedom means having the ability to decide how to spend one’s time, which can lead to increased well-being and a balance between work and personal life. People in most Nordic countries have a fairly good work-life balance, meaning that they are relatively in control of what they get to spend their time doing. Of course, freedom and choice are affected by our life circumstances such as where and how we work, whether we have children, and what our support networks look like — but regardless, having more personal freedoms is proven to increase happiness.

24 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Quality Relationships: In every study the Happiness Research Institute conducts and in every data set they look at, whether it’s local, national, or international, the quality of our relationships is often the best predictor of whether people are happy or not. This appears to be true for humans across all geographies and cultures. No matter where we come from or where we live, what drives happiness in Copenhagen is similar to what drives happiness in Washington, DC.

Generosity: As humans and social beings, we are fundamentally wired to feel good by doing good. Being kind and/or generous to those around us provides a shortterm boost to well-being — often called a “helper’s high.” Engaging in long-term volunteering can also lead to feelings like having a greater sense of meaning and purpose.

Community: The last factor highlights the importance of togetherness and belonging. Being part of a collective, and having strong relationships and a

community consistently appears as a major contributor to happiness — whether it’s measured at a precise moment in time, in general across a lifetime, or in terms of our sense of purpose.

25 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Nyhaven, Copenhagan, Denmark

Photo credit: Febiyan - Unsplash

happiness and the built environment

Our understanding of how our environment shapes our happiness has evolved quite a bit in the last few years. These seven “happiness factors” can provide direction for us as we design the built environment moving forward. The way we live and work is rapidly transforming — the dividing lines between the two continue to disappear. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated trends associated with the physical and virtual hybridization of urban life while also exposing other social, environmental, and economic challenges our cities will face in the future.

The pandemic also brought to light the health impacts of loneliness and social isolation, which have been linked to sleep loss, ill health, dementia, premature, death and even heartbreak. A 2010 study found that these effects on our health are as harmful to our life

expectancy as a 15-cigarette-a-day smoking habit. Even before the pandemic, global trends towards individualism and away from traditional sources of solidarity and community exacerbated loneliness.

A recent Kaiser Family Foundation Study showed that more than one in five adults in the United States (22%), United Kingdom (23%), and one in ten in Japan (9%) report being frequently feeling lonely or socially isolated.

Coupled with the effects of the pandemic, technology, and social media continue to simultaneously connect and isolate us. Many of us have an increased desire for meaningful shared experiences in connected, socially enriching environments.

So how can we design the built environment to promote social connection? What are some urban design strategies we can leverage

to improve our happiness? As designers and researchers at the global design firm HKS, we are committed to answering these questions. We believe that through research, informed intent, and meaningful (measurable) impact, are core tenets of responsible design and innovative practices. An HKS original research report, How the Built Environment Can Foster Social Health, identifies guidelines for design spaces that combat loneliness and social isolation and foster social capital and communities. Here are excerpts from the report:

26 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: Main Street. Charlottesville, Virginia

Photo credit: Tach - AdobeStock

the built environment as a social determinant of health

As humans, we evolved living in communities. People gathered in small tribes to support one another, to provide protection, warmth, food, and care for children. Given our nature, being completely autonomous and independent was a threat to survival. Our basic need to be interdependent remains, even though the backdrop of humanity has transformed over centuries.

The scientific community is just beginning to understand the extent to which the built environment of all scales is a social determinant of health. Research shows that designers and urban planners can increase people’s social capital in a place by creating spatial designs that facilitate social interaction among residents. Early research indicated that certain elements in neighborhoods, such as porches and tree-lined streets, can promote neighborly conversations and voter

turnout. Furthermore, a large-scale systematic review of the scientific literature showed that the design qualities of a place—walk-ability, sense of place, greenness, street design, and architecture—have the potential to increase social interaction, the integration of diverse people, social support, civic pride, social resilience, and social and political involvement.

Many American communities have become very car-dependent and less walkable through zoning ordinances that deemphasized public transit and essentially banned mixed-use zoning, and thus, pedestrian-oriented neighborhoods. However, walkable neighborhoods have been linked to higher social capital, lower rates of depression, less reported alcohol abuse, and more physical activity. Researchers have tied certain characteristics of the environment, such as house and

street design, population density, mixed land use, proximity to the city center, the amount of greenery and communal space to improvements in a range of social health markers, including social well-being, network size, trust, and perceived safety. Communities are feeling the pressure of urban sprawl, with commuting taking up more time that was once dedicated to leisure or family and friends. In contrast, high-rises and rows of cookie-cutter condominiums have popped up throughout cities like Seattle, San Francisco, and Dallas, marketed as modern living, but it appears developers gave little thought to how these facilities connect with the rest of the urban fabric, featuring buildings that crowd out any shared space between neighbors and that fail to offer a sense of welcome or scale in the form of overhangs, trees, and benches at street level.

28 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

This disregard for the surrounding environment may be partially to blame for an emerging body of research warning against adopting this development model. In addition, the popularity of door-delivery services and virtual

transactions is chipping away at the core of our humanity: the need for physical interactions with other people. We are losing the intervals in our everyday lives that get us to slow down and bond with those around us—the glue between the

physical spaces that frame our existence.

29 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Communal Meal

Photo credit: Priscilla Du Preeze

the power of third places

The prehistoric Stonehenge monument and other archaeological sites offer ample evidence of human civilization’s enduring need for communal gathering spaces, those places where people can come together for celebration, ritual, and the mundane. These places are what sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined third places—places unlike the private, informal home and the public, formal workplace, being both informal and public. These are places where people gather and socialize deliberately or casually: meet friends, cheer for the home team with fellow fans, or just sit to people-watch.

The physical environment is an important factor underlying our health ecosystem, influencing how we think, feel, and behave. This is why third places — libraries, coffee shops, parks — deserve our attention. Third places are a

special type of place unlike the private, informal home and the public, formal workplace, being both informal and public. Third places can strengthen social capital, foster social connection, and boost diversity and wellbeing. They also serve as “enabling places” that promote recovery from mental illness by providing social and material resources. Yet little is known about what design characteristics of a third place can help improve social health.

As designers and urban planners, we too often discount the importance of preserving and elevating human connection in an effort to focus on efficiency and lowering costs. Designing for social health is important for people in any era, but it is especially relevant today as loneliness and social isolation become more prevalent.

We are just beginning to recognize the role of our built environments in shaping our social experiences and opportunities for connection. Spaces designed and activated to facilitate social connection can help us overcome loneliness by sparking or supporting meaningful relationships.

The following guidelines are a resource on how to design for social health and empowers everybody with the tools to create better spaces.

30 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: Union Station Market, Washington DC

Photo credit: Susie Ho - Unsplash

Accessibility: Creating Places That are Safe, Inclusive, and Walkable

Perhaps the most foundational attribute of a good third place is that it is accessible to those who can use it. The best versions foster a sense of ownership and become regular parts of people’s lives. This requires safe, convenient, affordable, and comfortable access to the place. For children, this means they can gather, play, and explore with some independence from parents as developmentally appropriate. For senior adults or people with disabilities, this means that there are easy physical access options, benches to rest, and spaces to shelter them from the elements. For all ages, the ideal is a space that is within walking distance from home, work, or school. Humans evolved to navigate our worlds on our feet, and much research has shown the benefits of physical activity on the health of our minds and bodies, and the role of walkable streets, neighborhoods, and cities in fostering well-being.

Studies have demonstrated that people living in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods have more social capital compared to residents of car-oriented suburbs People in walkable neighborhoods report being more likely to trust others, participate politically, know their neighbors, and be socially engaged. Car dependence

limits opportunities for in-person interaction, and whenever possible, it is best to shift away from auto travel when we think about how people access a third place.

Activation: Programming Place from Ordinary to Extraordinary

Ideal third places bring together diverse people who seek recreation, amenities, or a break from monotony. Connections will happen naturally. The celebrated urban designer Jan Gehl put it this way: “Social activity is the fruit of the quality and length of the other types of activities because it occurs spontaneously when people meet in a particular place”. For third places to be successful, they must intentionally serve people’s fundamental needs, from quiet time to socializing.

At a coffee shop, this means spaces for meeting people, as well as spaces for focused work and patios for pets. Library activation can happen through child reading circles, spaces for teens to study and socialize after school, fun meetups for older adults, and cubicles for those just needing to hammer out work. For workspaces, activation means placing lunch tables and coffee machines next to the intersection of natural paths of travel but also providing places where the whole staff can gather for celebrations or town

halls. At the neighborhood block, this means having places where people can eat with their families, pick up a gift for a party, or cheer for a sports team. Activation can also include events on the street made possible by temporary road closures. This array of options interspersed with housing and work provides for a mixed-use area that is vibrant day and night and provides natural safety through “eyes on the street”. Often city or neighborhood parks fail, not because of the lack of green space or playscapes, but because there is little else to pull people to the park that supports the full spectrum of daily life.

Designing “purposeful inconveniences” that funnel everyday activities through a common point can lead people to slow down and connect with theirs. This strategy has been used at Pixar with its famous single set of bathrooms at the center of its Emeryville, California office, and at Zappos’ Las Vegas headquarters with its central plaza that is the single point of entry.

32 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: People biking in Washington DC

Photo credit: Tim - Adobe Stock

Choice: Finding Joy in Variety, Flexibility, and Control

Places that provide variety, flexibility, and choices on how to use the space fosters personal control and support habitual use for a wide range of activities that suit people’s varying needs and moods. Providing people, the freedom to choose how to engage (e.g., play, relax, focus) and where to locate themselves (e.g., booth seating, communal table) facilitates person-environment fit, or the ability for a person to choose or modify an environment to fit his or her needs and preferences, and creates a sense of comfort. The dynamic and changing nature of comfortable spatial proximities to people we encounter (e.g., strangers, acquaintances, or friends) is the basis of proxemics, the study of personal space, and helps inform different types of seating options.

Third places should support a wide range of uses and options for gathering with people or finding privacy. There should also be flexibility to fit a spectrum of needs and abilities (e.g., older adults, new mothers, and children’s groups). For children, this means creating a variety of ways to play (e.g., reading corner vs. jungle gym, playing in the fountain vs. on the grass) and the ability to control what activities to engage in. In workplaces, this means balancing

privacy and collaboration—a concept often called “we, me, us”—by allowing people to control where they sit and how they engage with others, based on the formality or informality of the circumstances.

Human Scale: Weaving Comfort into the DNA of a Place

Spaces designed at a human scale use architectural detailing and variety to create small and intimate environments that are comfortable for people to move through or occupy. These are spaces that meet our basic human needs for comfort, safety, and interest, and that feels good to be in for reasons that are often indescribable. City blocks designed at a human scale have been shown to promote more social interactions and lingering, whereas research reveals that blocks with large expanses of monotonous storefronts elevate stress responses and speed walking. This conclusion was tested at a Whole Foods in New York City, where a research team found that despite the store operator’s desire for Whole Foods to feel like a local grocery store and blend with the existing neighborhood, the expansive glass storefront repelled passersby, who quickened their pace to get past it. This finding echoes a growing body of research in both human and mouse models that show how spaces devoid of ornamentation and variety can elicit a strong stress response,

believed to be linked to the painful boredom they provoke.

A well-established components of the human-scale design is the quality of providing prospect and refuge, offered by buildings or spaces that create a sense of enclosure while giving people the ability to look out—for instance, being under a patio pergola or on a front porch and watching the street. If you have ever felt the pull of a cozy booth seat or rested at the base of a tree, you have experienced the natural comfort of a space that provided prospect and refuge. This quality promotes a dual sense of security and openness that allows us to deepen existing friendships and form new ones.

34 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: Outdoor Dining

Photo credit: Franz12 - Adobe Stock

Photo by franz12 - AdobeStock

Photo by franz12 - AdobeStock

Nature: Moving from Gray to Green

As humans, we evolved to be comforted by nature, a phenomenon known as biophilia. The benefits of exposure to nature have been demonstrated across environments, from hospitals to workplaces, schools, and beyond. There is growing evidence that exposure to direct and indirect natural elements, such as large and small greenery, daylight, and outdoor spaces, is positively linked to mental health. Urban green space has been tied to better physical and mental health, increased sociability, and decreased aggression and stress. And researchers have associated higher quantity and quality of streetscape greenery, which includes dense, well-maintained foliage, trees, and plantings, with elevated social cohesion. Furthermore, streetscape greenery has been identified as a factor that works with social cohesion to reduce acute health-related complaints and improve people’s perceptions of their general health and mental health. Greenery and natural elements can be especially important in places that are significant to well-being and restoration because of their known salutogenic effects. Third, places that blend the indoors and outdoors and integrate greenery are more effective at creating environments where people feel comfortable and want to linger—all ingredients in creating

opportunities for connection. We can design biophilic environments along three different dimensions: direct, indirect, and symbolic. Direct biophilic features are natural elements that do not rely on humans to sustain (e.g., daylight, native plants, animals). Indirect biophilic features require human intervention to preserve (e.g., potted plants). Symbolic biophilic features do not offer nature itself, but rather images or virtual experiences of nature.

Sense of Place: Crafting a Place as Unique as the People Who Use It.

A handful of architectural theorists mused that in the digital age, all spaces should be a blank canvas on which the digital world can imprint. That probably feels wrong to most of us, and rightfully so. We value uniqueness, whether it is a character in a favorite TV show, a quirky friend, or a beloved local hang-out. Capturing the uniqueness of the people who use a space and the community around it is vital to creating a third place that feels authentic, and sparks a sense of belonging. Since early studies of human geography, the place has been understood as space, imbued with human relations, culture, meaning, values, and activities. A third place may incorporate features or elements that are significant to its community through their meaning may not be immediately apparent to outsiders or their

appearance aesthetically pleasing to the public. For example, a Texas taco joint in Dallas’ Lower Greenville neighborhood has 10-foot-tall dancing frogs that perhaps make some drivers cringe, but they are nostalgic remnants of an old tango club and have become neighborhood icons. Especially effective third places can often provide types of social interactions that are lacking elsewhere in people’s lives. For instance, these places can help connect new mothers, patients struggling with cancer, and women dealing with infertility with other people in their shoes, and those connections can ultimately turn into friendships. In co-working spaces, certain features can make the environment feel vibrant and creative and motivate membership. People can symbolically honor this shared identity in many ways: by featuring rotating local artwork, having local community members create murals, pinning messages of encouragement in public areas, or displaying special pieces of décor to mirror the character of the place.Having the local community participate in the design and creation of a space contributes to the sense that the space is not merely a vessel for the masses but a unique reflection of the people who live and work in the area. Involving local stakeholders helps ensure not only that the aesthetics feel true to the community but also that the place serves local needs with the activities and amenities it provides.

36 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: Rock Creek Park, Washington DC

Photo credit: Silver Media- Adobe Stock

A Call to Action: Creating third places and enhancing happiness!

It is up to each of us to create connections in our own lives: to linger outside so we can spend time with our neighbors, to bring back block parties, to invite colleagues to join us for lunch. This kind of interplay is what transforms a space into a collective third place. Or better said: “Communal space becomes relevant to mental health when and only when it is humanized: urban residents invest communal space with meanings, emotions, and relations that lie at the heart of social life.” Whether it is turning a driveway into an

afterwork neighborly tea spot, or gathering other new moms for a regular night out, or petitioning the city for a new playscape at an old neighborhood park, our actions can cumulatively transform communities.

The six guidelines – accessibility, activation, choice, human scales, nature, and sense of place – for design for social health can apply to small or large built environments, from the office coffee station to the city block.

By using them in our own neighborhoods and backyards,

we can be a part of making cities happier, by design.

Visit HKS’ website for a full copy of the report. In it you will find additional research and guideline details, grounding the concepts in science and illustrating them with case studies. The section for each of the six guidelines also lists principles for the design of the physical environment, programming, and policy to give you the tools to take concrete action in your community, whether you’re a resident, business owner, or government authority.

38 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

39 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Cherry Blossom Festival, Washington DC

Photo credit: Sergio Ruiz- Adobe Stock

A parklet in San Fransisco CA

Photo credit: Sergio Ruiz- Adobe Stock

REFERENCES

Alrasheed, D. S. (2019). The relationship between neighborhood design and social capital as measured by carpooling. Journal of Regional Science, 59(5), 962–987. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12457

Bayne, K. (2018). Environmental enrichment and mouse models: Current perspectives. Animal Models and Experimental Medicine, 1(2), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/ame2.12015

Cabrera, J. F., & Najarian, J. C. (2015). How the built environment shapes spatial bridging ties and social capital. Environment andBehavior, 47(3), 239–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916513500275

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). The growing problem of loneliness. The Lancet, 391(10119), 426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01406736(18)30142-9

Carmona, M. (2019). Place value: place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes. Journal of Urban Design, 24(1), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/13574809.2018.1472523

Cattell, V., Dines, N., Gesler, W., & Curtis, S. (2008). Mingling, observing, and lingering: Everyday public spaces and their implications for well-being and social relations. Health and Place, 14(3), 544–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.10.007

Cigna. (2020). Loneliness and the Workplace: 2020 U.S. Report. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2018-0055

De Vries, S., van Dillen, S. M. E., Groenewegen, P. P., & Spreeuwenberg, P. (2013). Streetscape greenery and health: Stress, social cohesion and physical activity as mediators. Social Science and Medicine, 94, 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.030

Dijulio, B., Hamel, L., Muñana, C., & Brodie, M. (2018). Loneliness and social isolation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan: An international survey.

Dosen, A. S., & Ostwald, M. J. (2016). Evidence for prospect-refuge theory: a meta-analysis of the findings of environmental preference research. City, Territory and Architecture, 3(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-016-0033-1

Duff, C. (2012). Exploring the role of “enabling places” in promoting recovery from mental illness: A qualitative test of a relational model. Health & Place, 18(6), 1388–1395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.07.003

Ellard, C. (2015). Places of the heart: The psychogeography of everyday life. New York, NY: Bellevue Literary Press.

Fan, Y., Das, K. V., & Chen, Q. (2011). Neighborhood green, social support, physical activity, and stress: Assessing the cumulative impact. Health and Place, 17(6), 1202–1211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.08.008

Finlay, J., Esposito, M., Kim, M. H., Gomez-Lopez, I., & Clarke, P. (2019). Closure of ‘third places’? Exploring potential consequences for collective health and wellbeing. Health and Place, 60(October), 102225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102225

Fu, Q. (2018). Communal space and depression: A structural-equation analysis of relational and psycho-spatial pathways. Health and Place, 53(July), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.06.007

Glover, T. D., & Parry, D. C. (2008). Friendships developed subsequent to a stressful life event: The interplay of leisure, social capital, and health. Journal of Leisure Research, 40(2), 208–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2008.11950138

Glover, T. D., & Parry, D. C. (2009). A third place in the everyday lives of people living with cancer: Functions of Gilda’s Club of Greater Toronto. Health and Place, 15(1), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.02.007

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday.

Hickman, P. (2013). “Third places” and social interaction in deprived neighbourhoods in Great Britain. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 28(2), 221–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-012-9306-5

Holt-Lunstad, J. (2017). The potential public health relevance of social isolation and loneliness: Prevalence, epidemiology, and risk factors. Public Policy & Aging Report, 27(4), 127–130. https://doi.org/10.1093/ppar/prx030

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., & Layton, J. B. (2010). Social relationships and mortality risk: A meta-analytic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(7), e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

Hood, C. M., Gennuso, K. P., Swain, G. R., & Catlin, B. B. (2016). County health rankings: Relationships between determinant factors and health outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(2), 129–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.024

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. New York, 71, 474. https://doi.org/10.2307/794509

Kahana, E., Lovegreen, L., Kahana, B., & Kahana, M. (2003). Person, environment, and person-environment fit as influences on residential satisfaction of elders. Environment and Behavior, 35(3), 434–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916503035003007

Kellert, S. (2008). Dimensions, elements, and attri-butes of biophilic design. In J. H. Kellert, J. Heerwagen, & M. Mador (Eds.), Biophilic design: The theory, science, and practice of bringing buildings to life (pp. 3–19). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kelly, J.-F., Breadon, P., Davis, C., Hunter, A., Mares, P., Mullerworth, D., … Weidmann, B. (2012). Social Cities. Melbourne. https://doi.org/10.1017/ cbo9780511706257.014

40 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

41 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

public space for a privatized individual

By Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar, iSTUDIOS

ABSTRACT

Architects have often used the 3 basic planes of designing spaces. The roof, wall and floor plane. These planes are used to determine our relationship with space. With the development of digital technology, this has changed our relationship with space again.

Digital technology is now integrated in our daily lives more than ever. It has changed how we share information with each other and how we engage with the spaces around us. We can sit on a couch and work, enjoy entertainment, order groceries and food, connect and communicate with each other. In particular, the impact of digital technology can be seen in the changes in how we communicate in the public realm.

Before the internet, the public realm was found in the form of

public space. People gathered in physical spaces to display public opinion about the latest policies and to share their thoughts about their governments. The public space was also a stage for artists, a place where people could remain anonymous, but still be connected to the people around the area. The space formed an environment which nurtured and interacted with human behavior, thereby giving rise to a people-environment relationship.

The project investigates the impact of the digital space on our relationship with space and on a newly emergent form of public sphere in the digital world.

IMPACT OF DIGITAL SPACE ON SOCIETY

Shalini Misra and Daniel Stokols in their paper discuss the importance of the people-environment

relationship at a societal level.

There has been considerable concern about the societal consequences of virtual forms of interpersonal communication and social interaction, such as in the form of chat rooms and virtual communities, as well as the privatization of public life. Putnam, for example, voices the concern that the effortless ability to communicate through the internet might encourage people to spend more time alone and interact with unknown people, reducing their ability to make meaningful relationships with face-to-face interaction and instead encouraging superficial exchanges with strangers. Further, online communication by avid Internet users may result in underdeveloped social relationships with their online communication partners, at least in some instances (Misra,

Stokols

42 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

2012). Even when conversing with close friends and family, impoverished online conversations might displace higher-quality, face-to-face conversations as people tend to omit the social niceties that promote and maintain social relationships (Misra, Stokols 2012). Gergen contends that online conversations, as in the case of email, become obligatory and pragmatic acts, instead of personal expressions. Horizontal relationships that emphasize a breadth of contacts are favored over vertical relationships that require dedicated attention, effort, time, and commitment (Misra, Stokols 2012).

The digital space has given rise to multiple ways of being connected to each other, but has failed to offer a way to develop a meaningful relationship with each other,though this meaningful bond between humans is critical in keeping the social fabric intact.

PUBLIC SPACE AND PUBLIC SPHERE

The terms “public space” and “public sphere” have both been used by different actors to signify differing meanings. The Habermasian formulation of the public sphere posited a novel form of social interaction facilitated by a

network of institutions comprised by physical locations and mediated discourses. Following this model, the public sphere is understood by scholars as mediated exchanges that are deeply rooted in placebased communication. “A set of physical and mediated spaces” is what Catherine Quires has defined as the public sphere, where people come together to deliberate, express, and identify interests of common concern.

I understand the public sphere as a theater and the citizens as its actors. As a form,the public sphere stirs social and collective imagination. This form also enables

43 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Diagram of the three planes of space making along with the 4th plane, the digital plane. Image Credit: Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

people to come together and agree on principles to achieve social consensus. Thus, the form of the public sphere uses the most optimum way to reach the masses. The diagram illustrates the relations between the public space and the public sphere.

STRATEGY

Existing design-based studies of public spaces offer some clues as to their importance, but most do not value public spaces for their ties to public spheres. These designs are constrained by incomplete definitions, and the endings and scope of their research are limited.

The most successful public spaces have successful physical and programmatic qualities that can be applied elsewhere. A successful public sphere also attracts users on the platform with the most engaging features.

Taking this basis forward, the design solution is divided into a place and cyber-based strategy. The place-based strategy is a collection of public spaces and places in a city that respond to the vibrant socio -cultural nature of every neighborhood. The public space can be permanent or temporary based on the community’s choice to participate.

These spaces of a city collectively form a single public space for the city. The public spaces can be used by the citizens for social gatherings/ events or any other event of collective nature.

The cyber-based strategy is a platform for the organizer of the event to use it as a platform to inform the citizens around the public space. The cyber-based strategy is in the form of a digital application. As the usage of mobile phones has increased and is owned by almost everyone. The cyber space thus gives everyone a possibility to engage in social events in the physical space. The

44 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Diagram of the components that shape the public sphere Image Credit: Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

combination of this place-cyber strategy enables the reachability of the social events conducted throughout the city but engages the public in the physical faceto-face situations. This enables citizens to engage in public space with civility. Richard Sennett (1978) best models the Citizen of Affairs for us in his vision of a public life based on civility, the activity that protects people from one another and yet allows them to enjoy one another’s company and makes it possible for people to act together as citizens in the political and social affairs of the city (IRwin. Zube, 1989).

PHYSICAL SPACE

“Habermas’s account of the bourgeois conception of the public sphere stresses its claim to be open and accessible to all. Indeed, this idea of open access is one of the central meanings of the norm of publicity” (Fraser 1990).

The digital application is the space where the user gets an idea about the space and chooses to come for the event. This puts the emphasis on the physical design of the space to attract the crowds. The strategy compels the organizer to develop

the space in a manner that can be attractive for the visitor. Just as the design/atmosphere of a restaurant is also important as much as the food to attract customers, it is the design of the individual spaces that will attract visitors.

The reason for having movable furniture is to encourage vibrancy and change in the public place design. The furniture can be made to encourage interaction or solitude for the visitor. The furniture could be a set of benches and tables that can be used by visitors for playing board games. The furniture could even be designed by local communities

45 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

An example set of physical public space in the city embedded across a pedestrian pathway Image Credit: Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

46 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Above: An example set of physical public furniture across the city.

Image Credit: Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

47 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

A digital public space application as an aggregator for social activities in the physical space.

Image Credit: Ameya Lokesh Kaulaskar

to celebrate their festivals thus increasing the diversity and inclusivity in public space design. The furniture could be locally made or brought from any commercial shop.

The community can pool together capital to arrange furniture for a local event or make the furniture itself. This initiative creates a new market for locals to engage in furniture making that can be designed and sold for specific events. This enables local talents for shaping local districts.

The furniture could be designed in space such as a park, a sidewalk, or a street. Each of these types of spaces is then designed following a vocabulary of typologies such as a curb, a bench, or a lawn. The typologies that we use to design public space do not consider the way we communicate and navigate the city through digital devices.

DIGITAL SPACE

The Cyber-based design is in the form of an application. The application can be downloaded on the iOS and Android platform and is owned by a private company. The company provides the application as a platform for public discourse. The digital application does not control the curation of any event but rather just enables the user to reach out their target audience for the event.

event, the organizer is the main curator of the event and feeds the information of the event accordingly. The organizer also sets the location of the space. They can also leave images of how the place looks and feedback rating if it has been rated before.

When a visitor is near an event, they get a notification of what is happening in that area. If interested further, the visitor can click on it and get a more descriptive view of the event. This is when the visitor scrolls through the review of the event or of the place. The review is a rating system based on how comfortable, safe, and inclusive the event/ space is. The notification radius can be the organizer for the kind of event that is to be conducted. This creates an equal platform for organizers to host a community or city wide event. The objective of this platform is to bring together people for face-to-face interactions but are stimulated to the place by the design of the space.

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT ?

The thinking and development of digital futures has often been pioneered by engineers or people with an science background. The developments of engineering and technology is efficiency. However, in the pursuit of efficiency we end up stepping on the very values that keep the social fabric of the society together. These are the most connected but the loneliest times of history. This very paradoxical nature of our society shows the advantage and the curse of technology.

Technology works of efficiency; design aims for synthesis of form and reason. Both are important for innovation and society but if one is left behind, the society faces the consequences of the first. It is important designers start taking a leading role in thinking about the future and build research to show the future direction to technology.

The user can login into the application and set up an

Just as grub hub or google reviews helps us get an understanding of what is review of a restaurant that we go to. This application gives and idea of what is kind review of spaces the visitor wants to visit. The feedback system of the application gives data for urban designer to understand public’s response to the furniture and thus enable the participation of the public in the making of their urban spaces.

48 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

REFERENCES

Altman, Irwin, and Ervin H. Zube. Human Behavior and Environment, Advances in Theory and Research. First ed., vol. 2 2, Plenum, 1989.

Curry, Chandler. “Public Space, the Public Sphere, and the Urban as Public Realm.” Curry Chandler, Curry Chandler, 6 Feb. 2017, https:// currychandler.com/cool-medium/2017/2/6/public-space-the-public-sphere-and-the-urban-as-public-realm.

Fraser, Nancy. “Rethinking the Public Sphere: A Contribution to the Critique of Actually Existing Democracy.” Social Text, no. 25/26, 1990, p. 56., https://doi.org/10.2307/466240.

Keswani, Serena C. “The Form and Use of Public Space in a Changing Urban Context.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1992.

Misra, Shalini, and Daniel Stokols. “A Typology of People–Environment Relationships in the Digital Age.” Technology in Society, vol. 34, no. 4, 2012, pp. 311–325., https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2012.10.003.

Sennett, Richard. The Fall of the Public Man. Penguin, 2002.

Canovan, Margaret. “POLITICS AS CULTURE: HANNAH ARENDT AND THE PUBLIC REALM.” History of Political Thought, vol. 6, no. 3, 1985, pp. 617–42. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26212420. Accessed 11 Jun. 2022.

MILLER, KRISTINE F. “Introduction: What Is Public Space?” Designs on the Public: The Private Lives of New York’s Public Spaces, NED-New edition, University of Minnesota Press, 2007, pp. ix–xxii. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctttv5pq.4. Accessed 11 Jun. 2022.

Stokes, Benjamin. “Locally Played - https://direct.mit.edu/books/book/4862/Locally-PlayedReal-World-Games-for-Stronger-Places

49 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

the lived-in city | happiness in urban form.

by Dominic Weilminster, AIA LEED AP BD+C, Points West Design Works

We’ve all experienced it, though it can be difficult to pin down in words: a lived-in space. Growing up, I can remember spending childhood summers at a family ranch near Steamboat Springs, Colorado. The modest ranch house and the agrarian structures, each well-worn with age and use. Everything had accumulated as a function of purpose at some time — no corner was left too sharp, no surface too pristine. The imprint of inhabitants was everywhere and, therefore, we felt welcome everywhere. As it turns out, some of the world’s most livable (aka happiest) places capture this same sense at an urban scale.

If understood, we can define the recipe to craft humanistic habitats that support our natural happiness.

Within the German city of Freiburg, the neighborhood of Vauban is a somewhat experimental

residential mixed-use community that exemplifies the simple values of happiness: of being connected, of being yourself, of slowing down and enjoying life. In Vauban, the importance of creating a city that feels rich in investment from its residents and that is authentically reflective of its community—what one of my colleagues termed “messiness”—becomes apparent. When a house feels lived in, you see that the kitchen is used daily for cooking. Books and magazines lay across the coffee table— not just for looks, but with the expectation of being dog-eared. The yard is a constant experiment in urban farming. Vauban is an entire neighborhood that feels this way.

In terms of happiness, Vauban creates an almost campus-like atmosphere of colorful structures, plazas, and paseos. Cars are part

of the mix, but are relegated to second or third-class status, behind pedestrians and bikes. On-street parking is the only option and there are a significant number of streets—likely 40 percent—that is organized for a strictly temporary car presence and are otherwise designed as places for pedestrian activity.

Understanding the relationship between urban design, transit, open space and social factors is key to building better spaces and communities in the future.

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Vauban is the organic nature of the public realm and the lived-in quality of the residential developments. Although much of the architecture is not very old, maxing at around 15 to 20 years, the housing has been imbued with significant personality, giving

50 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

it the sense of being occupied much longer than it has in reality. What this tells the casual observer is that people in Vauban have a considerable association with their place of residence. It also implies a certain social cohesion within the community; people aren’t just manicuring their lawns to show that they can keep up with the Joneses, they are comfortable expressing themselves.

Vauban, with its quiet play streets and its cohesive and calm residential developments, provides almost familial neighbor to neighbor interaction—providing

social stimulus, but also privacy. Connecting everything is a strong bike network which is linked to comfortable walking spaces and a high-frequency streetcar system. Together, these elements simplify and increase the speed of travel between Vauban and greater Freiburg, while promoting social interaction.

Understanding the relationship between urban design, transit, open space, and social factors is key to building better spaces and communities in the future. This seems logical enough but, more often than not, the intangible

pursuit of happiness is not a part of our design, planning, and development dialogues. Typically, expansion of the built environment is focused on marketdriven growth, which responds to land use planning that serves a type of functional and organized logic. The design of these spaces is then heavily biased by desires for convenience, security, and familiarity. But what about if we also thought about what makes us happy?

People are both social and contemplative: too much isolation or over-stimulation

51 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

A typical neighborhood street in Vauban provides the whole picture of how these spaces are used, including garden spaces along each street which are shaped by residents’ investment in the public realm. Image Credit - Dominic Weilminster

can both result in discomfort. Our physical environments are never homogenous (at least they shouldn’t be) and designing for happiness centers shaping experiences to provide a balance of dynamic engagement and comfort to meet both sides of human nature Think about your own experience with happiness – there are scales. We are not necessarily speaking about that fleeting sense of being overjoyed. A better target for happiness is perhaps a sense of fulfillment, satisfaction, and consistent connectedness. A form of happiness in which you are comfortable in your own skin and feel a sense of openness, empathy, and even kinship with those in your community. This is the baseline we

likely all want for our lives, so how does it translate to the physical environment around us?

The notion of a city form that promotes day-to-day human happiness relates to the ability of a city to provide a living and working environment that affords people both the time and freedom to pursue their own happiness, either in a private or social manner. This is a simple statement, but it has a number of implications for urban form. A city that affords individuals with time is one that is connected, which implies a certain degree of density. A city that allows people to engage socially is one that contains open-ended public spaces for organic human

interaction, offering a diversity of uses and providing flexibility to users as to how they would like to engage. This ultimately opens the door for people to function and participate in a long-term community. However, just as a city needs to provide spaces for interaction, it also needs to afford privacy. Humans may be social but are often most comfortably social in smaller numbers. Urban spaces that break an overall experience down into bite-size use clusters provide for a greater sense of ownership over smaller-scale public or semi-public spaces. By designing for smaller-use clusters in cities, we support people by providing opportunities for more open social engagement, while also

52 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Contextual Map highlighting Vauban & Copenhagen Image Credit - Dominic Weilminster

Image Credit - www.vienncouver.com

offering them the ability to feel more secure in their surroundings. When spaces are designed to encourage people to be openly social and also secure, we can quiet the fight or flight instincts and encourage residents are more to feel more positive and reflective.

Amazing things happen when places are designed around happiness: We are better connected with others and we play more often. A trip to Copenhagen’s waterfront on a warm weekend expresses this perfectly. With rolling sculpted piers of varying sizes, the water’s edge through the heart of the city becomes a

playground for kids and adults alike. No special event or cost of admission required. The design of spaces to invite whimsy and exploration provide an unspoken permission (not to mention a draw) for the community to claim the waterfront—and to have a great time doing so.

So what does all of this mean? Really, for a city to work well, it needs to provide opportunities for human investment and support that investment. The term human investment does not necessarily mean monetary investment, although that may be required. It refers to people being able to

really ‘live’ in a community, and to call it their own. Our cities need amenitized infrastructure which is appropriately sized for the human pace of the population that it serves. It does not need to be glamorous or refined, but it does need to be easily accessed through resident-propelled, convenient mobility strategies.

When spaces are designed to encourage people to be openly social and also secure, we can quiet the fight or flight instincts and encourage residents are more to feel more positive and reflective.

53 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Copenhagen’s waterfront invites interaction, play and individual interpretation for it’s use making it a loved destination for all demographics of the community..

54 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Above - Typical pedestrian activated streetscapes

Image Credit - Dominic Weilminster

Once people have access, the spaces need to provide them with social and physical comfort via scale, a sense of ownership in the relationship they hold with the common spaces in which they live and work, and at best, an

experience of discovery or delight which invites all members of the community to make those spaces more memorable. Happy cities are fundamentally places where each member of the local population is a participant (and ultimately

becomes) the foundation of the city’s viability. It is not a strategy about making a destination; it is working simply with what (and who) we have to create a place that feels ‘lived in’.

55 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

Apart from showcasing sustainability, Vaubaun is designed with a degree of colorful organic texture allowing for and encouraging self-expression by residents. This subtle strategy allows this relatively young urban neighborhood to feel ‘lived-in’. Image Credit - joergens.mi - Wikimedia Commons

56 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Copenhagen’s general building orientation is toward the public realm, which is designed for open-ended use and sociability. Whether as a feature of public or privately owned space, the culture of life in the city allows residents and visitors to ‘make themselves at home’ in the public open space around building Image Credit - Dominic Weilminster

57 Avenues, Volume 5 Happy Cities

firmitas, utilitas, venustas no longer

Joseph McKenley, AIA , NCARB, Grizform Design Architects

We are introduced to the famous triad of Firmitas, Utilitas, and Venustas in book three of Vitruvius’

Ten Books on Architecture circa 27 BCE. “Firmness or physical strength secured the building’s structural integrity. The utility provided an efficient arrangement of spaces and mechanical systems to meet the functional needs of its occupants. And venustas, the aesthetic quality associated with the goddess Venus, imparted style, proportion, and visual beauty.

Rendered memorably into English by Henry Wotton, a seventeenthcentury translator, “firmness, commodity, and delight” remain the essential components of all successful architectural design.” With all advancements since then, it still holds true that a building well built meets all three traits equally. By extension, a city of buildings that meet all three traits equally is a happy city. Today, I

find that triangles are often more obtuse than equilateral.

I find this especially apparent in the façades we build today. I find that Architects, under tremendous pressure, have given over to a new triad of priorities - speed, performance, and commerce. I find that this new triad results in buildings that quite often leaves me wanting for more - more strength in their structure and materials; and more beauty. Not usually more utility. Thanks to everincreasing building performance standards, and to costs of construction, efficiency seems to remain a very high priority for clients and so for buildings.

The façade, coming from the Latin word “faccia” or face, is a critical element in the design of cities. The façades of buildings amalgamate to define the streets and plazas that create cities.

So, building façades are the DNA of a city - their uniqueness or sameness contributes to the gestalt of that city - and as such that face is of high importance to a happy city.

Yearly, I give a lecture at the University of Maryland School of Architecture on the Façade as Mediator and as Metaphor. In that lecture, I recognized that the purpose of the façade is two-fold. First, a façade must protect the building and its inhabitants from the elements. A façade must first provide an enclosure; it should keep the rain and snow out, and contribute to providing a thermally comfortable interior. Then, the façade has a duty to the built environment - an aesthetic duty. It also has an opportunity. Façades are able to project an ideal into the built environment, in fact in my lecture I go as far as to say that façades are projections of

58 AIA|DC Urban Design Committee

Next Page: Vitruvius, the ten books on Architecture originally published crica 27 BCE Image Credit: Amazon Books