JIM THOMPSON

DECADES AFTER THE 1967 DISAPPEARANCE OF AMERICAN TEXTILE ENTREPRENEUR JIM THOMPSON, KNOWN AS THE THAI SILK KING, HIS EPONYMOUS BANGKOK-BASED COMPANY LIVES ON, AND SO DO HIS VALUES. WE EXPLORE THE UNLIKELY STORY OF A HERITAGE BRAND THAT FLOURISHES IN SPITE OF—AND PARTLY BECAUSE OF—ITS FOUNDER’S UNSOLVED MYSTERY.

An array of crimson umbrellas mirrors the hue of the teak paneling featured throughout the house.

An array of crimson umbrellas mirrors the hue of the teak paneling featured throughout the house.

In the sweltry darkness of an April Bangkok night, we pass through an alleyway of squat concrete buildings to arrive at an anonymouslooking gate. Just beyond a gravel courtyard, a cinnabar-hued jewel of a 19th century Thai house comes into focus, nestled in a jungly thicket of palms. This is the storied House on the Klong. The famed homage to the region's architecture and art was assiduously assembled by an even more famous man—Jim Thompson, the former Thai Silk King, whose legend the passage of time doesn't seem to diminish but perhaps even emboldens. Thompson, a Princeton-trained architect and art collector who spent the 1930s living and working in New York, first arrived in Bangkok as a World War II military officer in August 1945. Enthralled by Thai culture, particularly the region’s ancient textile traditions, he settled there after the war and began organizing and supporting local artisans, creating a network of Thai weavers and silk farmers whose ancient skills and livelihoods were being threatened by post-war industrialization. By 1950, Thompson had founded the Thai Silk Company, an artisan cooperative, and is credited for single-handedly resuscitating Thailand’s dwindling silk industry and spinning it into an international sensation. Celebrated for his deft use of dazzling color combinations and classic patterns, the multi-armed business Thompson began, improbably, still flourishes today.

As we slip off our shoes and cross the threshold into the House on the Klong’s receiving room of checkerboard marble floors, which Thompson sourced himself, and rich teak paneled walls, an air of mystery and marvel pervades the space, which remains much as it was when Thompson walked out these doors, 56 years ago, never to return. It was Easter in 1967 when Thompson left his home to visit old friends in Malaysia’s remote Cameron Highlands, and after attending a morning church service and enjoying an Easter picnic with his hosts, he vanished into thin air—or rather, into the vast jungle surrounding the country retreat. His disappearance touched off a manhunt of a scale previously unmatched in the region, and despite a thorough search that included extrasensory tactics enlisting the help of mediums and psychics, no credible trace of him has ever been found.

But Thompson’s home remains very much present, an ode to a man of vision, style and yes, mystique. A disoriented Westerner might mistake it, if even momentarily, for a Scandinavian-like interior, but that feeling vanishes quickly, replaced by a sensual physicality—the omnipresent heat, the thickness of the air and the buttery, worn-down patina of the teak floors underfoot which have caressed the bare feet of thousands of people over nearly two centuries. There is an intoxicating languor to it all. The whir of rotating fans, a slight to the modern convenience of air conditioning, is the only disturbance in the velvety blanket of air, which is just how Thompson wanted it.

In contrast to the languidness, every wall and surface of the home is alive thanks to the worldclass collection of Southeast Asian art Thompson accrued in his lifetime, a testament to his vast curiosity and zeal for his adopted country’s architecture and arts. As Somerset Maugham once noted while visiting Thompson, “You have not only beautiful things, but what is rarer you have arranged them with faultless taste.” In addition to Maugham, his guests included the likes of Robert Kennedy, Helena Rubinstein, Doris Duke and countless members of royalty and the diplomatic corps, and his parties and dinners were the stuff of Bangkok legend. Tonight, we were the lucky guests to follow in that tradition, albeit five decades later.

Our host is the ever-amiable Eric Booth, who greets us, a tray of cocktails at the ready, in Thompson’s former living room overlooking a stone courtyard and the klong, beyond which lays the storied Cham weaving village that first captivated Thompson. For Booth, executive director of Jim Thompson, the Thai Silk Company and the artistic legacy is a family affair. His father, Bill Booth, had been hired as a young man in his 20s by Thompson himself after serving in the US military. Bill Booth took over as managing director in 1972 and expanded the company into an even greater multifaceted business. Eric follows in his father’s footsteps but with a particularly keen interest in supporting the arts—especially work that addresses the political climate of his homeland and its people.

We dined that night with Eric on Andaman scallop ceviche, tom yum soup and yellow beef cheek curry, all redolent of the bracingly bright, sense-igniting food Thailand is so well known for. Elaborate phuang malai were arranged across the table, like an installation of fragrant floral jewelry. Belgian chandeliers overhead lit up the house. Lush palms, from banana to bismarck, crept into open windows, blurring the distinction between indoors and out. With the sound of the call to prayer from the Islamic neighborhood ringing from across the klong, the evening, steeped in wine and humidity, felt like a synesthesia dream.

The next morning, we returned to the house—the spell of night lifted. The house and its extensive art collection (now under the aegis of the James H.W. Thompson Foundation) is one of Bangkok’s most visited landmarks. Global languages mingle as group after group arrives. Visitors remove their shoes and follow guided tours through the serpentine rooms. Across the gravel courtyard is a modern two-level store, restaurant and exhibition space devoted to the timeline of Thompson’s life and business pursuits. The area is now known as the Jim Thompson Heritage Quarter. “Ironically, Jim’s disappearance turned out to be effective branding and marketing for the business,” Eric says. With every purchase of a scarf, necktie or bolt of fabric, the customer considers this story, as though he or she is buying a bit of the mystery itself.

This jewel of a house is, of course, the draw. Thompson discovered it while visiting the Cham artisans, the ethnically Vietnamese and Muslim group of traditional weavers who lived in the Ban Krua neighborhood (directly across from this spot on the klong). This is the group with whom Thompson had formed the Thai Silk Company, and on one visit, Thompson happened upon a 19th century Thai house that belonged to one of them. These traditional teak homes were being abandoned in lieu of more Western, ranch-style houses that boasted air conditioning and windows, but Thompson, a trained architect, appreciated the classic form. He acquired the building, turning it into the large, central structure of his house, while two similar structures were discovered in Ayutthaya to comprise the smaller flanking wings. Thompson brought over specialized carpenters also from Ayutthaya to reassemble the buildings—the addition of which ensured ample room for entertaining. “He was a social lion,” remarks Bruno Lemercier, conservator of the foundation. “Everyone stopping in Thailand wanted to see not just the silk, but Jim Thompson and his home. A mix of high society, celebrities and designers all came through here.”

This page: Gracious interiors are filled with art and antiques and furniture upholstered in the vibrant colors that Thompson was famous for, while lush greenery encircles the exterior of the home.

Eric Booth

Eric Booth

From the outset, Thompson envisioned his home as a showcase for his prodigious collection of regional art ranging from ceramics and paintings to sculpture and furniture. “He was an aesthete,” Bruno reflects. “Jim had a real eye, but he liked a good bargain. Many pieces he acquired had imperfections.” Thompson responded to innate beauty rather than museum-like standards. Some standouts include his collection of Benjarong porcelain in vivid, often pastel polychrome with Siamese motifs manufactured in China for the Thai elite. Scenic storytelling devotionals painted on cotton or silk, remarkably intact, hang from the walls. Thompson also retrofitted several windows to create niches for ancient large-scale Buddha sculptures, his favorite of which is a 7th-century limestone Dvaravati school example and remains the focal point of his former office. Thompson wanted his collection seen. “Six months after he moved in, he declared the house a museum, with entrance fee donations benefiting a school for the blind. He wanted to keep things for the Thai people, for his collection to remain together for people to enjoy,” Bruno says.

Art for the people remains a central tenet of Jim Thompson’s legacy. In 2021, the Jim Thompson Art Center opened as an homage to contemporary art and artists of the region. For Eric, this is a natural extension of the foundation, and he does not shy away from controversial or political subjects. Rather, he welcomes dialogue through socially and politically subversive art. “It’s not just another contemporary art exhibition space. The country faces issues today that date to the time Jim was here, many stemming from the Vietnam War and Cold War. What happened then still resonates now,” Eric says. Just a few blocks away from the antiquitiesfilled house, the Art Center welcomes a rotating series of thought-provoking shows. “For us, the house is very important. Like the handwoven silk—it’s about history. But we are also looking at the present and the future, and the Jim Thompson Art Center is where we engage with the social, economic and political situations in the region, and look toward how to solve these problems.”

A modern exhibit at the Jim Thompson Art Center.

This spread: An immersive tableau of richly painted scenes and meditative Buddhist statues mingle with vivid Benjarong porcelain and Chinese export ware.

A modern exhibit at the Jim Thompson Art Center.

This spread: An immersive tableau of richly painted scenes and meditative Buddhist statues mingle with vivid Benjarong porcelain and Chinese export ware.

Four hours north of Bangkok, the gateway of the historically impoverished Isan region is home to another Thompson legacy, the Jim Thompson Farm, known more simply as “the Farm.” We arrive, once again, in darkness. As urban as Thompson’s house is, the Farm is equally rural. We dine that night with Eric on a pond dock, complete with a silk tablecloth. In the distance, we view two temple structures on stilts above the water, floating like two wooden crowns gracing the still surface.

The Farm is the key to the evolution of the multitentacled brand that the Jim Thompson Company is today. Under Thompson’s cooperative-style business structure, silk weavers all worked from home, as the company was not poised for an economic future increasingly trending toward standardization. “My father, this young guy, takes the helm and says, ‘ok, let’s grow the business’,” recounts Eric over dinner. “He opened a factory for hand weaving and dyeing, then the next step on the vertical chain is raising your own silk worms, so he bought this farm.”

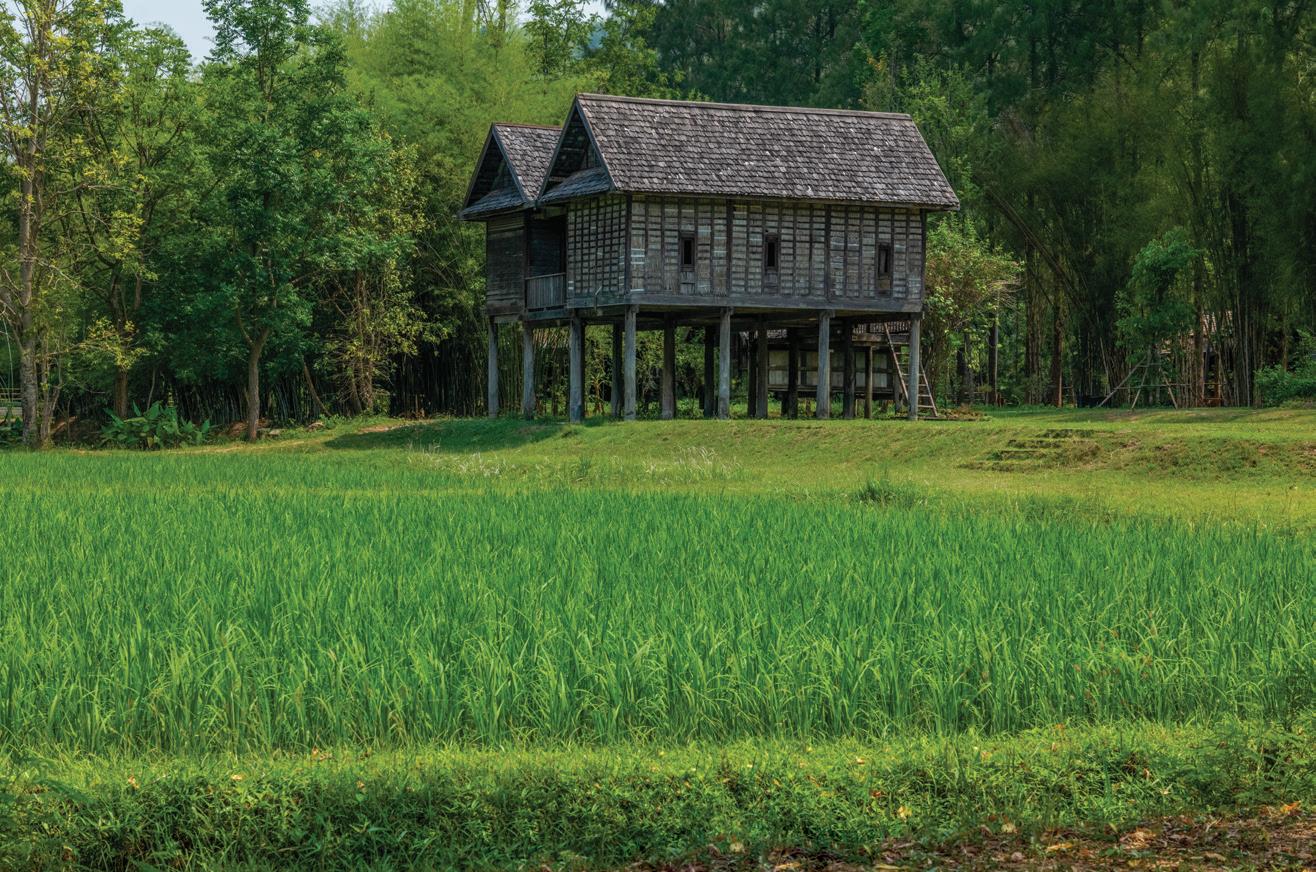

A temple constructed in the classic Isan style for prayer and contemplation graces the surface of the reservoir at the Jim Thompson Farm.

A temple constructed in the classic Isan style for prayer and contemplation graces the surface of the reservoir at the Jim Thompson Farm.

This spread: A day in the life of the Farm where silk weaving is only one of the traditional Thai arts and crafts that flourishes. Preserving these timeless skills and introducing them to visitors is one of Eric's greatest passions.

This spread: A day in the life of the Farm where silk weaving is only one of the traditional Thai arts and crafts that flourishes. Preserving these timeless skills and introducing them to visitors is one of Eric's greatest passions.

This spread: The ancient process of raising silkworms has remained unchanged for thousands of years.

This spread: The ancient process of raising silkworms has remained unchanged for thousands of years.

The arid land, not suited to rice production, was excellent for growing mulberry plants— the preferred food of silkworms. Bill Booth, after working with Chinese silk consultants, developed a Japanese-Chinese hybrid silkworm. Realizing that raising silkworms would require thousands of farmers, he created his own type of cooperative—selling silkworm eggs to farmers across the region for them to independently raise, while the Thompson farm would grow enough mulberry plants for their consumption. The four-stage process, from egg to larvae to molting and finally spinning a cocoon, takes 21 days. “It is like Goldilocks—they need just the right environment to produce the best silk,” Eric says. Once in the cocoon phase, the Jim Thompson Company buys them back from the farmers, paying a premium for the best quality cocoons to yield the finest silk. Once returned to the farm, the silk would be degummed and readied for the looms.

The next morning, Eric takes us on a tour of the farm and the entire silk-weaving process, from egg to final product. After seeing the silkworm in various phases of its cocooning process, we watch a woman tending a vat of boiling cocoons, melting away the binding glue to reveal the silk filaments. “This is the ancient process Jim discovered. When you look at the threads, they’re very uneven, full of humps and bumps, as Jim liked to say. When you dye it, the color doesn’t penetrate evenly—that’s what gives silk its iridescence,” Eric explains, as the woman unfurls filaments from the boiling va t of cocoons. “You can’t put it in a machine, it has to be handwoven. This is Thai silk.”

Bundles of hand-dyed silk threads. Their imperfect texture gives it iridescence.

Bundles of hand-dyed silk threads. Their imperfect texture gives it iridescence.

This spread: The Jim Thompson brand blends traditional handlooms meticulously controlled by artisans with the precision of modern machinery used for mechanically-printed designs.

This spread: The Jim Thompson brand blends traditional handlooms meticulously controlled by artisans with the precision of modern machinery used for mechanically-printed designs.

With a handloom on site, silk by the yard is being made much as it has been for centuries. Dozens of women and men tend the silk, dyeing it in brilliant colors, winding the bobbins, warping the looms and hand weaving the yarns into fabric. The handmade silk will eventually make its way to their showrooms in Bangkok, Paris, New York and London and into homes around the world. In contrast to mass manufacturing, it is remarkable to witness this ancient technique, harnessed for modern luxury by Jim Thompson. Such high-touch artistry is the foundation of the legendary man’s legacy.

But the company is far from anachronistic. Bill and Eric Booth have moved the needle forward on implementing technology to remain competitive. “There’s been a huge investment in modern machinery, printing and weaving to stay relevant for the future,” Eric says. A short drive away, by which we arrive in open-air vintage army jeeps, is the multi-building factory for the mechanized looms—an industrial silk city in the middle of this rural countryside. State-of-the-art automatic looms spin out the resplendent silk scarves and fabrics for the current collection of clothes the company is increasingly known for within Thailand. Silk bolts for interior designers are churned out with inspiration from creative directors, Susan North and Richard Smith. Designs by young artists the brand collaborates with, an effort led by their newly appointed CEO, Frank Cancelloni, come to life. “All our collections relate to Jim—what he was interested in, techniques he modernized. Even the artists we work with to create these collections are always thinking about Jim, his era and what he was interested in. How those things inform us now,” Frank explains.

In the spirit of Thompson, the Booths also use the land as a place for architectural preservation. A collection of authentic Thai houses sourced from all over Isan have been painstakingly moved and reassembled as a focal point on the Farm. “We started collecting the houses. The inspiration, of course, is the Jim Thompson House,” Eric says, “it inspires everyone in a different way. He was fascinated by the traditional culture and architecture. He’d go out on the weekend in his jeep, exploring. He was our Indiana Jones, a real adventurer.” In addition to the reconstructed 19thcentury houses, the Booths also had two temples built on the water, connected to land by a walkway. The two wood structures served two functions: one, built in the Isan region style, is a place for the monks to conduct ceremonies and pray; while the second, modeled on the Isan and Southern Laos tradition, is a kind of library for religious texts. Both stand on stilts hovering above the Farm’s pond, which is also its reservoir.

“These temples were built over water for termite protection. With no bridge linking them to land, the religious texts, made of paper and cloth, would be safeguarded,” Eric explains. A collection of simple hand-carved wood Buddhas presides in the temple reserved for prayer. Perched above the pond with a cross breeze flowing through the structure, the feeling of serenity is palpable.

Eric reflects on the entwined, carefully woven legacy that permeates the Jim Thompson Company today, both in their business and cultural endeavors. “It’s not just the silk. It’s the support of the weavers. It’s the arts. It’s the house itself and the collection within it, all of which shows how much Jim cared about conservation and sharing knowledge,” he says. The Jim Thompson legacy is ultimately a dialogue between past and present.

This spread: Two temples hover over the glassy surface of the water; one a place for contemplation and prayer, the other designed to house and protect religious texts.

This spread: Two temples hover over the glassy surface of the water; one a place for contemplation and prayer, the other designed to house and protect religious texts.

On our last night at the Farm, Eric invited the weavers to feast with us. A sprawling buffet of curries, soups, grilled fish and game, complete with a platter of silkworm pupa accompanied by fish sauce and a dash of chili and lime was washed down with Thai moonshine—rice distilled into a sakereminiscent milk-hued alcohol. We sat on picnic tables facing a stage where a local singing group performed traditional song and dance, which lasted well into the night. A hand-painted backdrop of farmland and antique houses was like a scenic simulacrum of the Farm’s own landscape. Above the stage, a large, dazzling swath of apricot and watermelon checked silk, the likes of which Jim Thompson was famous for, hung like a vibrant banner above the performers, whose music lilted for hours in the embracing darkness. It was evident that while Jim Thompson has been gone for decades, his joyous spirit lives on in the world he created.

A folkloric musical performance added to the cultural experience that made our visit to the farm so enriching.

T he breadth of Jim Thompson’s contemporary business is evident at the company’s 9 Surawong Road location, which Thompson himself opened in 1967, a mere nine days before his fateful disappearance. On our last day in Bangkok, thirdgeneration brand steward, Sasaya Vesanen, spent the afternoon immersing us in the expansive flagship, which was recently reimagined under her watchful eye. The store is connected to the three-floor home furnishings showroom, the main o ces and the sprawling shop full of silk fashion accessories, homewares and clothing. In Thompson’s day, silk for dressmaking was the company’s bread and butter, and people flocked to 9 Surawong Road where silk was displayed in large mahogany wardrobes and brought out to be draped and presented to customers for custom tailoring. Thompson’s fame led to fabric commissions for the costumes in The King & I and Ben Hur. He drew fashion support from Vogue Editor-in-Chief Edna Woolman Chase and collaborated with the likes of Rochas and Balmain. Today, Sasaya and Frank work hand-in-hand to creatively intertwine the fashion and home brands under one roof. According to Sasaya, “What we’ve done at 9 Surawong Road is to show the depth of what the Jim Thompson brand has to o er.”