Iuel-Brockdorff

Every Danish schoolchild learns about Niels Juel, a naval hero famous for routing the Swedes in the Battle of Køge Bay in 1677. Despite being outnumbered by men, guns and ships, Juel’s brilliant tactical innovation led to the greatest victory in Danish naval history and gave the Danish-Norwegian alliance control of the Baltic Sea.

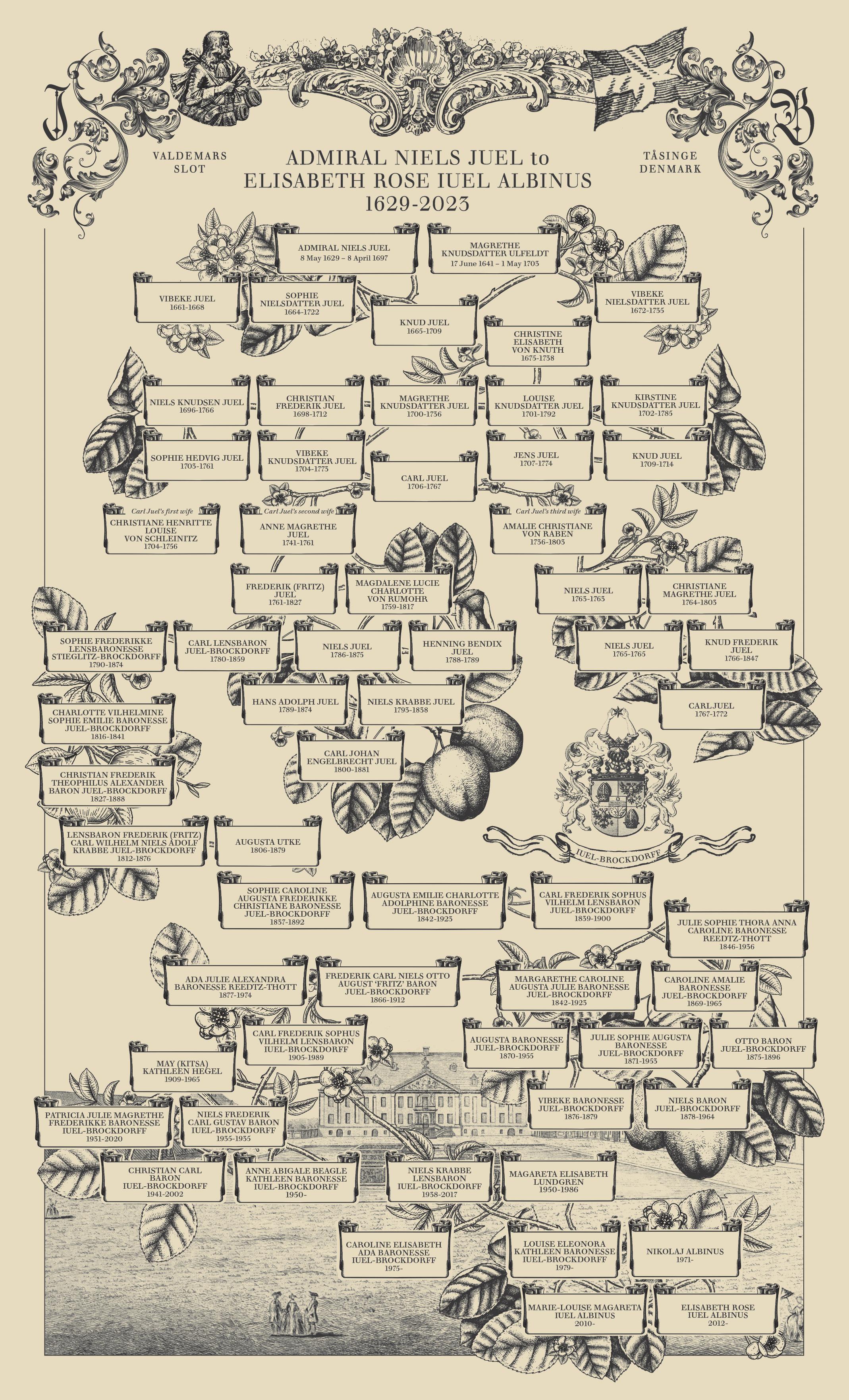

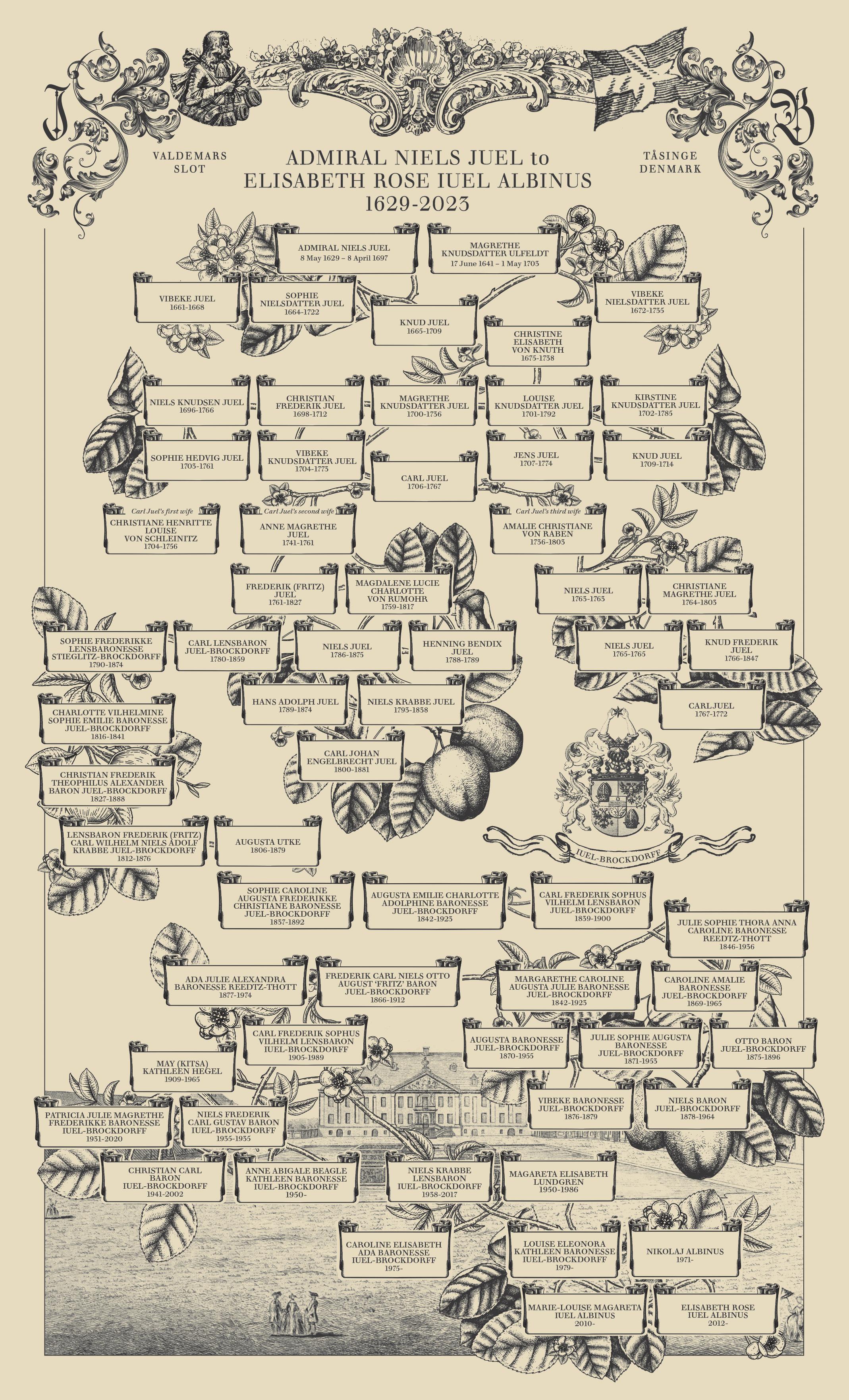

Thousands of Danes daily pass by a commanding bronze statue of Juel that presides over a major intersection in the heart of Copenhagen. Louise Albinus is one of them. She is the picture of vitality, her glowing skin framed by blond hair caught in a loose braid. In her typically casual attire of jeans and sneakers, she blends in with her hardy Dane neighbors, giving no hint of resemblance to the famous admiral in his swashbuckling tall boots, flared coat and broad festooned hat. But Louise is also known as Louise Eleonora Kathleen Iuel-Brockdorff and Niels Juel is her 10th great grandfather. (Juel morphed to Iuel around 1900).

Juel’s victory and valor earned him knighthood bestowed by King Christian IV, thus elevating his heirs to nobility, which, generations later, makes Louise a baroness. Juel’s other reward was Valdemars Slot, a castle commissioned by the king and intended for his son Valdemar, who died young and never took up residence. Designed by Hans van Steenwinckel the

Younger and built from 1639 to 1644, the elegant edifice is more manor house than castle, the largest privately owned home in Denmark and the only royal palace in private hands.

Louise is so nonchalant about her aristocratic status it’s nearly undetectable. She is quick to smile, open and curious, warmly welcoming to all. But underlying her relaxed demeanor she has a Juel-like core of strength, one that has been put to the test in ways she could never have predicted just a few short years ago. As happens in many families, noble or otherwise, hers went through turmoil following the death in 2017 of her beloved father, Baron Niels Krabbe Iuel-Brockdorff.

It’s been a seesawing period of good and bad luck, wonder and woe. Regrettably, a family dispute forced the sale of the estate on the open market. Happily, a term in the baron’s will stipulated that should Valdemars ever be sold, Louise had the sole right to buy it back, something she did in April 2022. Sadly, that term did not apply to the furnishings, the majority of which were removed the following month and put up for auction last September. Luckily, many of the things she cherished most, like irreplaceable portraits of family members, were eventually returned to Valdemars through a series of challenging, often emotional events and gestures. The unexpected generosity of many who have helped recover these artifacts has further buoyed Louise’s mission to restore Valdemars’ heritage.

51 THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE

Louise Eleonora Kathleen

Lifesize equestrian portraits line the walls of the King’s Room.

Lifesize equestrian portraits line the walls of the King’s Room.

In the Reception Room, shrouded figures in tapestries from the mid-18th century contrast with lighthearted overdoor paintings of ladies of the era.

In the Reception Room, shrouded figures in tapestries from the mid-18th century contrast with lighthearted overdoor paintings of ladies of the era.

Arches along a wall of the vast entry hall frame the symmetrical staircase to the second floor.

Arches along a wall of the vast entry hall frame the symmetrical staircase to the second floor.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

To lend financial support to the dream, Louise and her husband Nikolaj have rented some of the 30 small houses scattered around the estate, but the focus is always on making improvements that nurture the arts. “Coming from a banking background, my orientation tends to be the bottom line,” Nikolaj says, “but Louise reminds me to ‘leave your financial head far away.’ I’ve come to realize many propositions, no matter how much business they might generate, simply don’t fit

It’s a tall order. Where once there was a roster of 100 staff, including three solely to attend to the chicken house and gather eggs, now there are three staff in total. There is so much space to work with it’s hard to know where to begin. But what space! Appropriately for an admiral’s manor, Valdemars sits mostly surrounded by water, on the island of Tåsinge in southern Denmark. The main façade of the manor house looks east, past twin gatehouses, out over a rectangular reflecting pond flanked by long low buildings that served as stables, to an enchanting tea pavilion punctuating the eastern shore of the property. It was Niels Juel’s grandson who commissioned these additional buildings in the mid-1800s and by so doing, made the manor house the formal head of a Baroque landscape, the only

63

Beneath Rococo flourishes, pine floors laid in a simple cross pattern in the Garden Room anchor the space.

Beneath Rococo flourishes, pine floors laid in a simple cross pattern in the Garden Room anchor the space.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

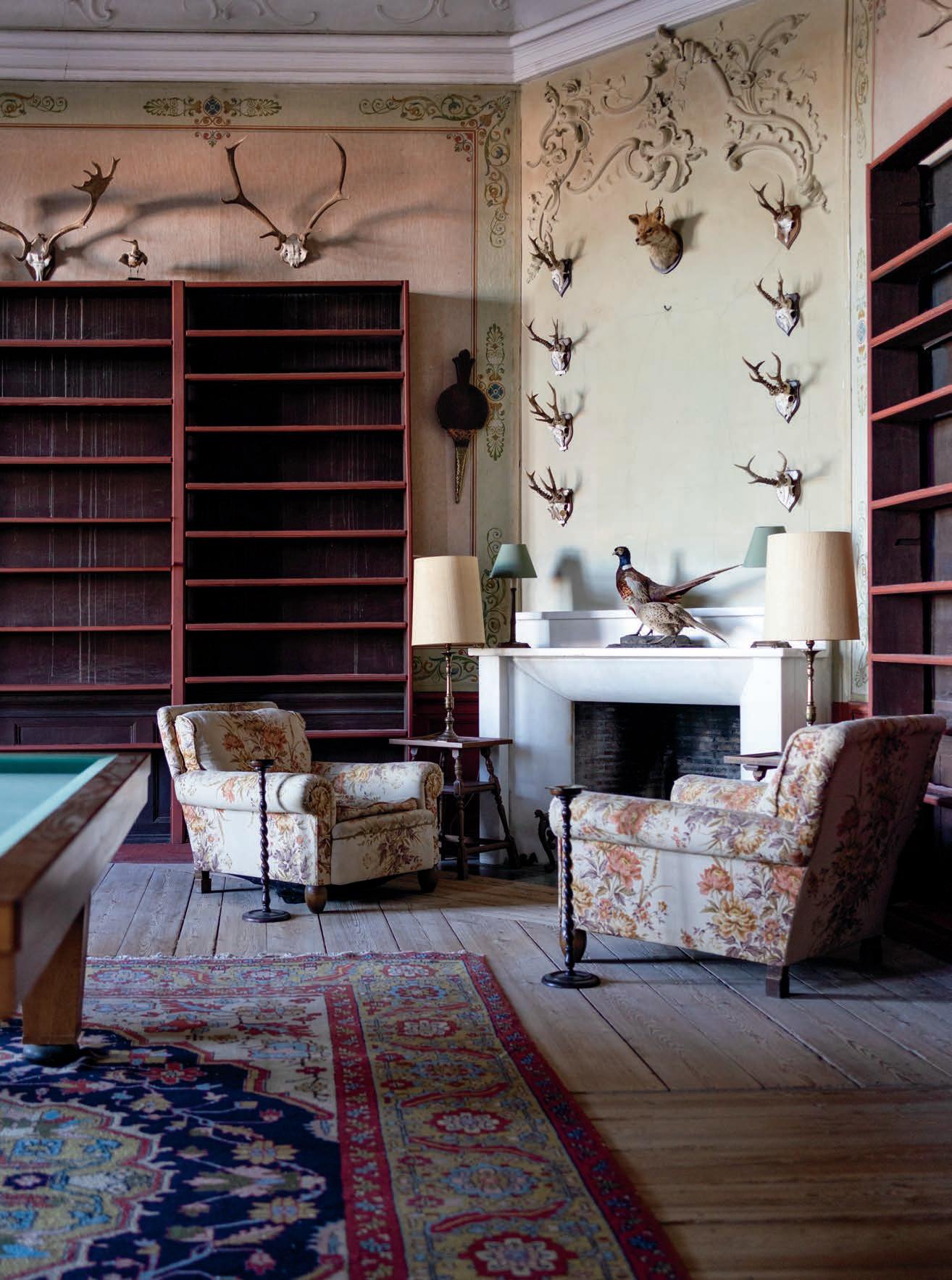

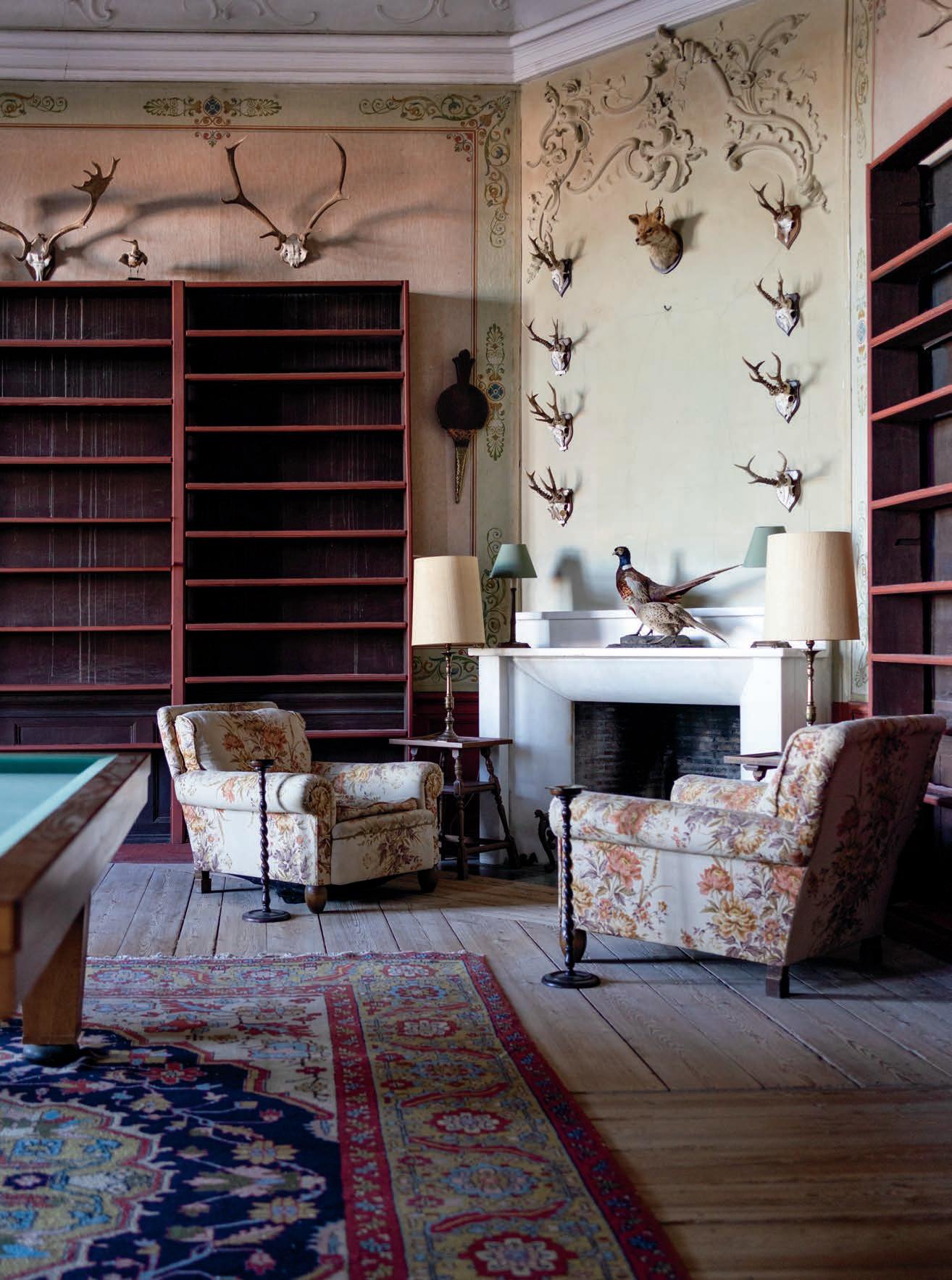

Louise has borne the upheaval with remarkable equanimity, even optimism. In some ways, the castle being emptied created a clean slate for thinking about the property’s future. Where Valdemars was once immersed in the past, with portions of the castle and outbuildings devoted to a toy museum, a big game trophy collection and a maritime museum, now Louise sees room to look forward and throw open the doors to new ideas.

“One of my great visions and dreams is to host exhibitions featuring current and deceased artists inside the castle, and even installations of modern architecture and design,” says Louise, who studied art history at the University of Virginia. “I think that the contrast between Rococo-decorated walls and the work of modern artists will be quite powerful, and it will again make the place a living art space.”

Aside from exhibitions, she hopes to host everything from performances by international artists to readings by local poets. “The 18th-century Danish poet Ambrosius Stub used to write poems at the base of an oak tree just a few steps from here,” Louise says. “Now the tree, named after him, is one of the oldest (400 years) and biggest (24’ in girth) in Denmark.”

To lend financial support to the dream, Louise and her husband Nikolaj have rented some of the 30 small houses scattered around the estate, but the focus is always on making improvements that nurture the arts. “Coming from a banking background, my orientation tends to be the bottom line,” Nikolaj says, “but Louise reminds me to ‘leave your financial head far away.’ I’ve come to realize many propositions, no matter how much business they might generate, simply don’t fit with the DNA.”

It’s a tall order. Where once there was a roster of 100 staff, including three solely to attend to the chicken house and gather eggs, now there are three staff in total. There is so much space to work with it’s hard to know where to begin. But what space! Appropriately for an admiral’s manor, Valdemars sits mostly surrounded by water, on the island of Tåsinge in southern Denmark. The main façade of the manor house looks east, past twin gatehouses, out over a rectangular reflecting pond flanked by long low buildings that served as stables, to an enchanting tea pavilion punctuating the eastern shore of the property. It was Niels Juel’s grandson who commissioned these additional buildings in the mid-1800s and by so doing, made the manor house the formal head of a Baroque landscape, the only intact one of its kind in Denmark.

THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE 63

Valdemars is the largest privately held house in Denmark.

One of two identical gatehouses in a cheery yellow that bookend the entrances to the property.

One of two identical gatehouses in a cheery yellow that bookend the entrances to the property.

Fanciful plasterwork frames Flemish tapestries in the Reception Room.

Fanciful plasterwork frames Flemish tapestries in the Reception Room.

A painting of Niels Juel’s grandson in a guest bedroom shows that the view looking east remains unchanged.

A painting of Niels Juel’s grandson in a guest bedroom shows that the view looking east remains unchanged.

A centuries-old leather portfolio holds historic architectural plans for the castle.

On a window sill in the dining room, a cloth cloche protects the feather crown that once topped a campaign bed.

Lawyer and family friend Klavs von Lowsow and Nikolaj discuss Valdemars’ future.

Cast iron stoves from Norway have long warmed the castle’s rooms.

A centuries-old leather portfolio holds historic architectural plans for the castle.

On a window sill in the dining room, a cloth cloche protects the feather crown that once topped a campaign bed.

Lawyer and family friend Klavs von Lowsow and Nikolaj discuss Valdemars’ future.

Cast iron stoves from Norway have long warmed the castle’s rooms.

69 THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE

Louise gingerly examines original drawings of the castle.

In the library, bookshelves will be removed to restore the room to its original, more austere state.

In the library, bookshelves will be removed to restore the room to its original, more austere state.

Glass apples handblown nearby reference the orchards planted by Niels Juel the Younger in the mid-18th-century.

Glass apples handblown nearby reference the orchards planted by Niels Juel the Younger in the mid-18th-century.

This spread: Nikolaj and Louise, along with architect Jess Heine Andersen and lawyer Klavs von Lowsow, contemplate the ways the stables and barns can be sensitively repurposed for cultural installations and events.

This spread: Nikolaj and Louise, along with architect Jess Heine Andersen and lawyer Klavs von Lowsow, contemplate the ways the stables and barns can be sensitively repurposed for cultural installations and events.

There are yet more outbuildings behind the north stables, some soaring spaces like a horse arena and barn where Louise’s father, an avid sailor, used to store his boats, and some less lofty spaces, like a dairy shed named Hollander House after the Dutch workers skilled at milking animals and making cheese. Each building displays the year it was built along with the initials of those who built it; more formal buildings like the stables also bear a coronet with seven points, indicating the rank of baron.

The reflecting pond is flanked by similar but not identical stables.

The reflecting pond is flanked by similar but not identical stables.

To the south of the manor house are smaller scale structures. A blacksmith forge stands alone, a candidate for a future estate manager’s office. For generations, the manager occupied the ground floor of an adjacent two-story building with household staff bunked under the roof; men in one string of rooms, women in another. The lower floor has recently been handsomely converted into a few apartments, but the upper story remains largely untouched, an atmospheric time capsule complete with handwritten names of flowers on doors. Wallpaper artfully shreds off the old walls; a recently discovered nook once hid weapons and resistance fighters during World War II.

This page: Time stands still on the upper floors of the building that once housed the estate manager.

This page: Time stands still on the upper floors of the building that once housed the estate manager.

75 THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE

A serene face casts a nonchalant eye over construction materials piled in the old forge.

One of the most surprising characteristics of the façade of the manor house are the tall Gothic windows that circle the south end of the building, throwing off the symmetry synonymous with Baroque architecture. It’s as if the chapel that lies behind them was so overflowing with special powers that they broke through the façade to declare their importance.

To call it a chapel hardly does it justice. Gothic vaults soar over a space that accommodates nearly 200 for services. An organ occupies the better part of a choir

loft that spans the back of the room. Another balcony, this one festooned with swagged curtains and the Iuel-Brockdorff crest, was just for the family. Yet for all its magnificence, the chapel retains a Scandinavian sobriety. The leaded windows are clear, not stained glass; an austere tiled stove heats the space; the stone walls and marble pews are all trompe l’oeil; the overall palette is a warm chalky gray. Hovering overhead is a wooden model of a ship, in the Danish tradition of installing a miniature ship in a church as an offering ensuring safe passage for the vessel and its crew.

Major family events, such as the christenings of Louise and Nikolaj’s daughters, continue to take place in the chapel.

Major family events, such as the christenings of Louise and Nikolaj’s daughters, continue to take place in the chapel.

A model ship, representing safe passage through life’s storms, is suspended near the choir loft of the chapel.

A model ship, representing safe passage through life’s storms, is suspended near the choir loft of the chapel.

79 THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE

This spread: Louise, accompanied by daughters Elisabeth Rose and Marie-Louise, points out details of the chapel behind an altar that was modified in the 1880s.

Louise greets us in the chapel from the private family balcony.

Louise greets us in the chapel from the private family balcony.

Of all the spaces in the manor house, the chapel holds the most meaning for Louise and Nikolaj. It is where they were married on a bright spring day in 2009. It is where their two daughters, Marie-Louise and Elisabeth Rose, were baptized just as their mother was. And it is where they have first tested the waters of reopening Valdemars to the public. “In the past,” Louise explains, “the castle has been a place where many musicians have gathered. There was even once a music school, two hundred years ago. So bringing music back seemed like a very natural way to begin.”

Last December, they held two candlelit Christmas concerts featuring an opera singer, a violinist and a pianist, followed by a reception in the entry hall where gløgg

and special apple buns were served. (Niels Juel’s grandson first introduced apples to the island, and Louise hopes to restore the estate’s orchards.) Demand was so great that the 150 tickets on offer sold out in 24 hours, and the public begged for additional performances. Tickets to a second day of concerts were scooped up in no time.

The concert response demonstrated more than just the locals’ curiosity to see a chapel not normally open to the public. It confirmed their sincere and sympathetic support for Louise and Nikolaj’s stewardship of Valdemars. The sundering of antiques that had been part of the manor house for 350 years was painful not just for them but for the entire community who justly viewed it as an assault on their patrimony.

81 THE CURRENT, VOL. 5 | PLACE

This page: Louise and Nikolaj's daughters Marie-Louise and Elisabeth Rose in the chapel.

Clockwise, from top: An original copperplate engraving of the layout of the castle and garden; a leather drum likely used in a military campaign; an oar from Louise’s great-grandfather’s winning rowing team at Oxford; amid intricate calligraphy, the family crest remains vibrant.

Clockwise, from top: An original copperplate engraving of the layout of the castle and garden; a leather drum likely used in a military campaign; an oar from Louise’s great-grandfather’s winning rowing team at Oxford; amid intricate calligraphy, the family crest remains vibrant.

Support has arrived both overtly and in mysterious ways. When Louise and Nikolaj were reviewing the paintings and furnishings they hoped to buy back and return to Valdemars, they made two lists: “nice to have” and “need to have.” Of the 91 items offered in the first auction, they had earmarked 22 as critical and won them all. Of 260 items in the second auction, they secured 27 of the 31 they sought.

Of all the things on display throughout the auctions, though, most spectacular was Louise’s resolve. She sat front and center, going after her birthright with such determination that she put other bidders to shame for daring to raise a paddle and contribute to the dispersal of an historic estate. So touched were people by the sad saga of seeing Valdemars’ interiors dismantled that a few bidders even won significant items and anonymously donated them back to Valdemars.

An enormous painting of the Battle of Køge Bay dominates the upper hall.

Louise holding a portrait of King Christian IV of Denmark by Karel van Mander III.

An enormous painting of the Battle of Køge Bay dominates the upper hall.

Louise holding a portrait of King Christian IV of Denmark by Karel van Mander III.

The Knight’s Hall, a confection of delicate plasterwork, is missing its chandeliers but not its magnificent portraits which are considered official artworks of Denmark’s patrimony.

The Knight’s Hall, a confection of delicate plasterwork, is missing its chandeliers but not its magnificent portraits which are considered official artworks of Denmark’s patrimony.

Most prized of these gifts is a set of 33 chairs, historic shipboard witnesses to Niels Juel’s winning campaign, that have returned to the elegant ballroom where Louise and Nikolaj held their wedding banquet. In an otherwise all-white room with frothy plaster embellishments, the gilded seat backs of the exquisitely-tooled boarskin chairs echo the gold frames of magnificent royal portraits by court painter Carl Gustaf Pilo. “The chairs’ homecoming is such a proud event,” says Nikolaj. “They’ve become a symbol of Louise’s devotion to Valdemars’ legacy and to the community that has rallied to support her.”

To witness the treasures returning to Valdemars was to see Louise’s face light up with pure joy, like a child on Christmas morning. Their return marked more than a win for family continuity. It represented the restoration of significant Danish cultural heritage. As caretaker and restorer, Louise is stewarding the history of Valdemars for her children, the 12th generation, and those to follow. As a visionary, she is fighting to unite the old world with the modern one. Odds are good that she will succeed; after all, she is descended from Niels Juel.

86

Above: Embossed and gilded boarskin chair detail.

Right: Chairs returned to the estate echo the hues and extravagance of a portrait of King Christian VII that hangs above.

Treasured chairs returning to Valdemars.

VALDEMARS SLOT T Å SINGE, DENMARK THURSDAY, OCTOBER 19, 2022 11:23AM

A painting of Niels Juel’s decisive naval victory at Køge Bay.

Opposite: A portrait of Louise Albinus by Louise Fenne atop another more bucolic scenic landscape painting.

A painting of Niels Juel’s decisive naval victory at Køge Bay.

Opposite: A portrait of Louise Albinus by Louise Fenne atop another more bucolic scenic landscape painting.

The formal entrance to the manor house.

The formal entrance to the manor house.

Lifesize equestrian portraits line the walls of the King’s Room.

Lifesize equestrian portraits line the walls of the King’s Room.

In the Reception Room, shrouded figures in tapestries from the mid-18th century contrast with lighthearted overdoor paintings of ladies of the era.

In the Reception Room, shrouded figures in tapestries from the mid-18th century contrast with lighthearted overdoor paintings of ladies of the era.

Arches along a wall of the vast entry hall frame the symmetrical staircase to the second floor.

Arches along a wall of the vast entry hall frame the symmetrical staircase to the second floor.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

Beneath Rococo flourishes, pine floors laid in a simple cross pattern in the Garden Room anchor the space.

Beneath Rococo flourishes, pine floors laid in a simple cross pattern in the Garden Room anchor the space.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

Beneath renderings of champion horses, Louise unpacks far more significant portraits as they return to Valdemars.

One of two identical gatehouses in a cheery yellow that bookend the entrances to the property.

One of two identical gatehouses in a cheery yellow that bookend the entrances to the property.

Fanciful plasterwork frames Flemish tapestries in the Reception Room.

Fanciful plasterwork frames Flemish tapestries in the Reception Room.

A painting of Niels Juel’s grandson in a guest bedroom shows that the view looking east remains unchanged.

A painting of Niels Juel’s grandson in a guest bedroom shows that the view looking east remains unchanged.

A centuries-old leather portfolio holds historic architectural plans for the castle.

On a window sill in the dining room, a cloth cloche protects the feather crown that once topped a campaign bed.

Lawyer and family friend Klavs von Lowsow and Nikolaj discuss Valdemars’ future.

Cast iron stoves from Norway have long warmed the castle’s rooms.

A centuries-old leather portfolio holds historic architectural plans for the castle.

On a window sill in the dining room, a cloth cloche protects the feather crown that once topped a campaign bed.

Lawyer and family friend Klavs von Lowsow and Nikolaj discuss Valdemars’ future.

Cast iron stoves from Norway have long warmed the castle’s rooms.

In the library, bookshelves will be removed to restore the room to its original, more austere state.

In the library, bookshelves will be removed to restore the room to its original, more austere state.

Glass apples handblown nearby reference the orchards planted by Niels Juel the Younger in the mid-18th-century.

Glass apples handblown nearby reference the orchards planted by Niels Juel the Younger in the mid-18th-century.

This spread: Nikolaj and Louise, along with architect Jess Heine Andersen and lawyer Klavs von Lowsow, contemplate the ways the stables and barns can be sensitively repurposed for cultural installations and events.

This spread: Nikolaj and Louise, along with architect Jess Heine Andersen and lawyer Klavs von Lowsow, contemplate the ways the stables and barns can be sensitively repurposed for cultural installations and events.

The reflecting pond is flanked by similar but not identical stables.

The reflecting pond is flanked by similar but not identical stables.

This page: Time stands still on the upper floors of the building that once housed the estate manager.

This page: Time stands still on the upper floors of the building that once housed the estate manager.

Major family events, such as the christenings of Louise and Nikolaj’s daughters, continue to take place in the chapel.

Major family events, such as the christenings of Louise and Nikolaj’s daughters, continue to take place in the chapel.

A model ship, representing safe passage through life’s storms, is suspended near the choir loft of the chapel.

A model ship, representing safe passage through life’s storms, is suspended near the choir loft of the chapel.

Louise greets us in the chapel from the private family balcony.

Louise greets us in the chapel from the private family balcony.

Clockwise, from top: An original copperplate engraving of the layout of the castle and garden; a leather drum likely used in a military campaign; an oar from Louise’s great-grandfather’s winning rowing team at Oxford; amid intricate calligraphy, the family crest remains vibrant.

Clockwise, from top: An original copperplate engraving of the layout of the castle and garden; a leather drum likely used in a military campaign; an oar from Louise’s great-grandfather’s winning rowing team at Oxford; amid intricate calligraphy, the family crest remains vibrant.

An enormous painting of the Battle of Køge Bay dominates the upper hall.

Louise holding a portrait of King Christian IV of Denmark by Karel van Mander III.

An enormous painting of the Battle of Køge Bay dominates the upper hall.

Louise holding a portrait of King Christian IV of Denmark by Karel van Mander III.

The Knight’s Hall, a confection of delicate plasterwork, is missing its chandeliers but not its magnificent portraits which are considered official artworks of Denmark’s patrimony.

The Knight’s Hall, a confection of delicate plasterwork, is missing its chandeliers but not its magnificent portraits which are considered official artworks of Denmark’s patrimony.