WALTER HOOD

REIMAGINES

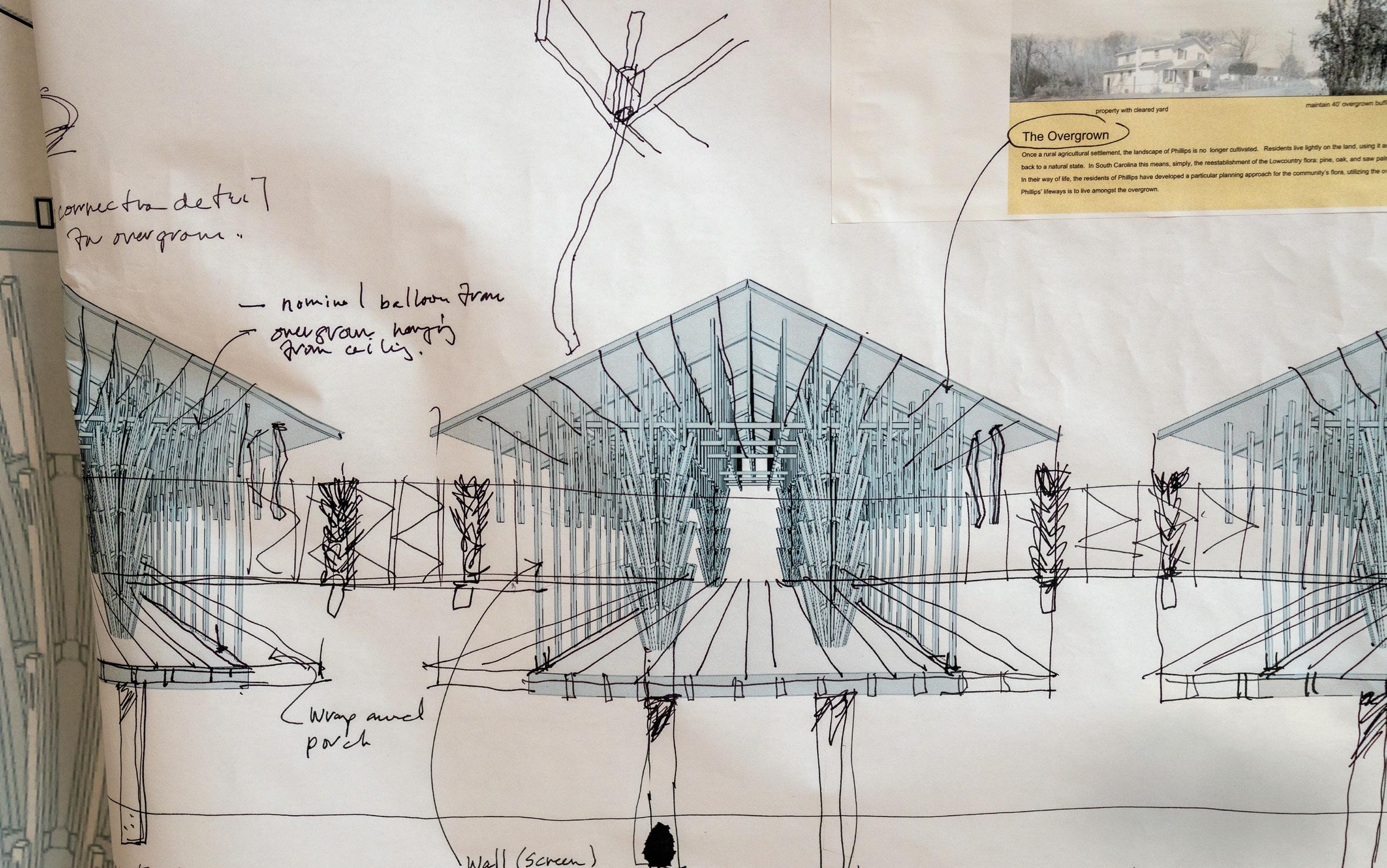

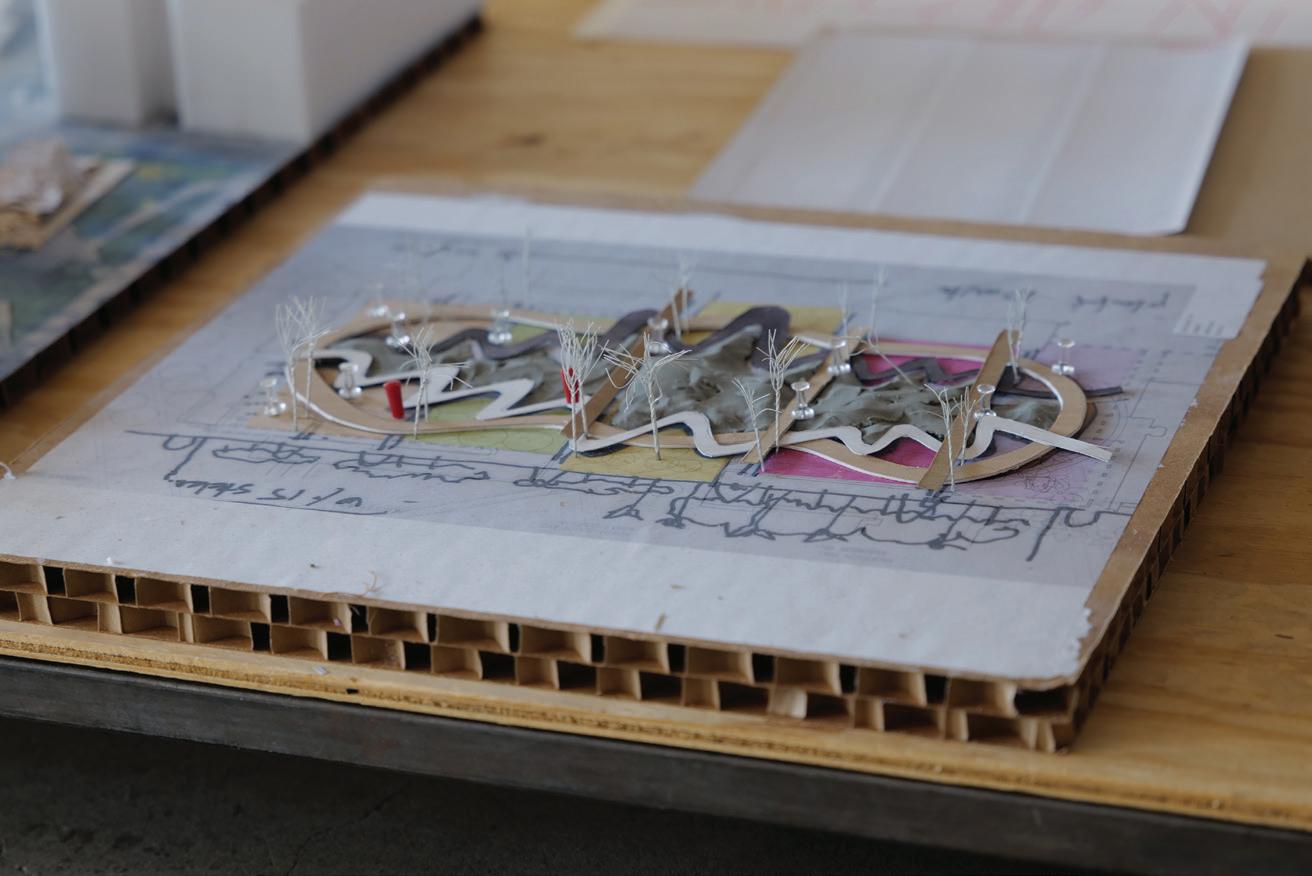

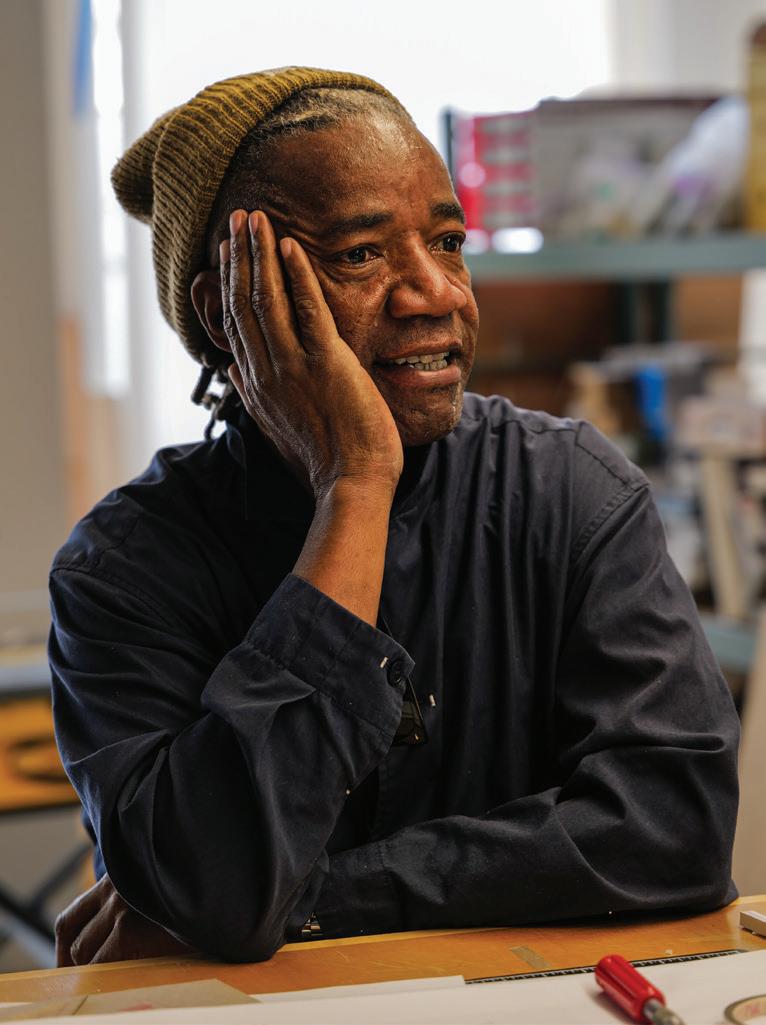

Walter Hood sharing concepts for the Venice Architecture Biennale.

Walter Hood sharing concepts for the Venice Architecture Biennale.

“ITS ALL GOOD IN THE HOOD” proclaims an old bumper sticker (in artful all caps, no apostrophe) in the bottom glass pane of Hood Design

Studio’s ruby red door, a funky vintage doorknocker beside it. It’s all good inside, too, where on the studio’s first floor five or so associates are busy fine-tuning details of current landscape design and art installation projects, including an ode to the shotgun house vernacular for a Jacksonville, Florida, commission commemorating the Johnson Brothers’ home site where the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” was written. “I call this reflective nostalgia; we’re not re-creating a shotgun house, but reflecting on it, designing a memory device to activate the space,” explains Walter Hood, the studio’s founder.

Upstairs, around a U-shaped conference table, Hood shuffles through his chunky sketchbook and large printouts of prototypes for his most recent, exciting and somewhat urgent endeavor—the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, a tremendous honor and opportunity that his team has just recently been given and now has only three months to prepare for.

The Biennale will be another high point of Hood’s threedecade design career that has had many. His accolades include the American Academy of Arts and Letters Architecture Award (2017), the Knight Public Spaces Fellowship (2019), the MacArthur Fellowship (2019) and the Dorothy and Lillian Gish Prize (also 2019), given “to a highly accomplished artist from any discipline who has pushed the boundaries of an art form, contributed to social change and paved the way for the next generation.” In 2021, Hood was awarded the Architectural League’s President’s Medal, the inscription of which dubbed Hood “the contemporary prophet of landscape and public space.” In addition to park prophet, other colleagues and fans have dubbed him a “community whisperer,” but neither is exactly right. First, there’s the problem of the park, which this renegade landscape designer believes is a tired term.

“The park really doesn’t have any power anymore,” Hood argues, digging his dirt-loving heels into a critical stance against the typology of traditional landscape architecture and environmental design. “Can we stop talking about types and talk about people’s relationship to things and places?” he asks.

Nor is Hood’s asking a whisper. The Oakland, Californiabased polymath—landscape designer, artist, urbanist, educator, provocateur—with his pulled-back dreads tinged with gray and his easy, youthful smile has a soft-spoken, gentle presence, but his designs, his vision, his art, is bold. Loud even.

Lush ferns and tree ferns outside the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park.

Lush ferns and tree ferns outside the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park.

Hood cranked up the volume, for example, in his paradigm-shifting “Black Towers/Black Power” installation at MoMA in 2021, part of “Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America,” the first-ever MoMA exhibit to feature Black architects. In it, Hood presented a series of ten rhythmic, sculptural high-rise towers along an urban California avenue, each tower inspired by a patent held by African American innovators (e.g. the folding chair and heating furnace). Together, they “reimagine(d) what a healthy, vibrant and safe neighborhood might look like for Black and Brown people,” Hood explained. His evocative ebony towers and the show in general was “mind-blowing, beautiful work,” according to The New York Times, with “radical goals,” including offering “necessary responses to a system of cultural exclusion that, time and again, erased, demeaned and denied Blackness.”

No, Walter Hood doesn’t whisper to the community, or to a project site, or even to an august institution like MoMA. Rather, he listens to the land’s whispers, the residents’ whispers. His ear is to the ground. He is tuned to echoes of ancestors, to the murmurs of memory and pleas of place, to fissures and scars, stories and dreams long buried, excluded, erased. Despite his three-plus decades of practice and internationally celebrated career as a landscape designer, Walter Hood doesn’t really design landscapes. At least not in the sense of an expert swooping in to impose his vision on a project—a massing of pretty perennials here, shady benches there. Instead, Hood interrogates, interprets and amplifies the narratives that the place, the land, already holds.

Consider, for example, the art-filled geometric gardens at San Francisco’s de Young Museum, where Hood embraced

what he calls the “conscious/unconscious hybridization” of landscapes by pushing against the romantic notion to return to origin (in this case, the origin of Golden Gate park is a big sand dune). Alternatively, he created a fiction, an artifice—a sculpture tea garden and lush tree ferns enveloped within the museum itself, with “places for kids to play and benches for people to sleep on,” he says. “We’re trying to get people to look down at the ground as they move through this space, look at the stone, the beautiful coloration of the sandstone, and actually think about where they are.”

Or consider Oakland’s Splash Pad Park, where Hood re-envisioned the underpass below the intrusive I-580, activating mundane parking spaces and curbs into a vibrant community gathering place, now home to the East Bay’s largest farmer’s market. And one of his more recent projects, the sacred grounds of the International African American Museum in Charleston, South Carolina, where, among other elements, Hood created an infinityedge fountain engraved with abstract forms suggesting figures bound in slave ship bowels to mark the threshold where more than 40 percent of the African diaspora arrived as enslaved chattel. “Our work is about fusing and disrupting and being really deliberate about how we are doing things based on the places in which we are making things,” he explains.

Whether designing for a major museum or cultural institution or a blighted urban streetscape, Hood begins with an intuitive and nuanced sense of place, which is where his personal creative path began as well. Growing up in Charlotte, North Carolina, the son of a career service man, Hood and his family lived in subsidized housing when he was young. For junior high, he was bussed from the

inner city to the suburbs—he remembers being in 7th grade before he first saw a split-level house—and by high school, his family moved to the suburbs. There, as on family trips to visit relatives up North, Hood became aware of how Black people moved through the world differently in these contrasting environments—his first inklings of grappling with the formative power of the public realm. Though he didn’t yet have the vocabulary and conceptual framework to define it, Hood perceived that people act differently in response to different environments, and even as a young man, he began to innately grasp the sociology of spaces.

Always a dabbler and drawer, Hood’s interest in art led to drafting in high school, and from there, to enrolling in North Carolina A&T State University’s architecture program—becoming the first in his family to attend college. After hearing a visiting lecturer discuss landscape architecture, however, Hood switched majors, lured by what he felt was a more multidisciplinary approach to design. At the time, NC A&T was the only Historically Black College

or University (HBCU) to offer a degree in landscape architecture. Hood entered a field where, to this day, he remains an anomaly in a white-dominated profession.

For Hood, landscape design has always been an expansive artistic endeavor. He’s less a green-thumb horticulturalist than a visionary, an ever-curious intellectual interested in planting and nurturing verdant ideas, and he’s got the degrees to prove it. After earning his undergraduate degree and working a few years for the National Park Service and a private firm in Philadelphia, Hood went back to school, earning a master’s in landscape design and another in architecture at University of California, Berkeley. Later, he earned his MFA from The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Academia is fertile ground for a heady guy like Hood, who has been a professor at UC Berkeley since 1993 and lectures widely on campuses around the country, but he’s always combined teaching and mentoring students with his active practice, never retreating to the ivory tower. Unless you count the airy loft of his studio complex on the gritty edge of West Oakland, a

neighborhood that’s served as Hood’s living laboratory of sorts.

Two doors down from the live/work courtyard—a former sign factory—that is Hood Design Studio headquarters, a onestory brick building with barred door and windows boasts a hand-painted “American Casket Company” sign. Beside it, a small house’s façade features a quirky mural, with a discarded toilet-turned-planter as yard art. Across the street, chain link fencing encircles a scruffy abandoned lot. Today West Oakland, the city’s oldest neighborhood and birthplace of the Black Panthers, as well as the focus of Oakland’s “General Neighborhood

Renewal Plan” of the late 1950s, is pocked with pawnshops and payday lenders. Homeless squatters and bleak tent enclaves abound. Hood doesn’t have to look far to observe the recurring cycle of deterioration, renewal and deterioration again that results when paternalistic practices of traditional

An early conceptual prototype.

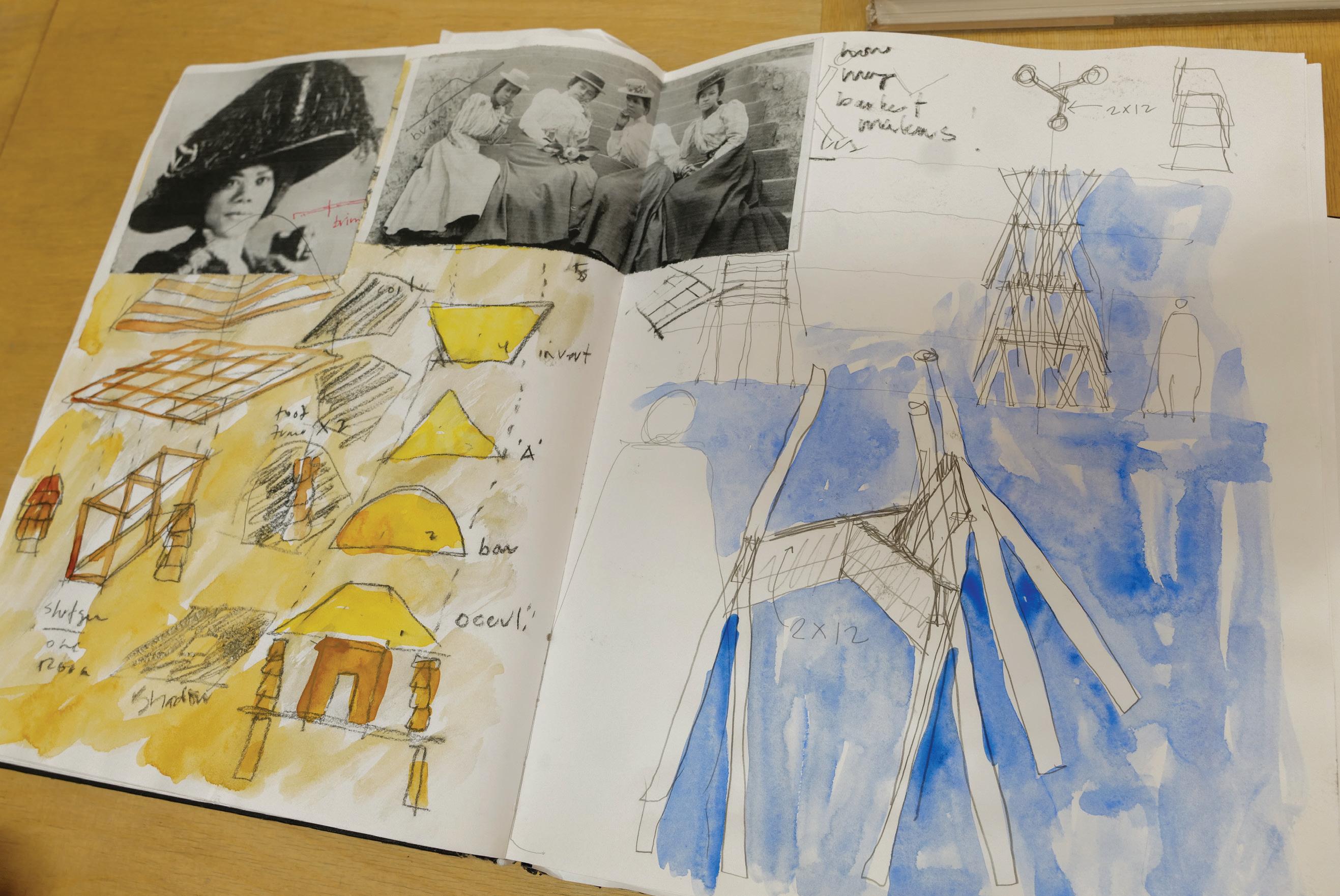

Vintage photographs spark ideas in the studio.

Hood instructing a team member on a shotgun house model for a Jacksonville, Florida, commission.

An early conceptual prototype.

Vintage photographs spark ideas in the studio.

Hood instructing a team member on a shotgun house model for a Jacksonville, Florida, commission.

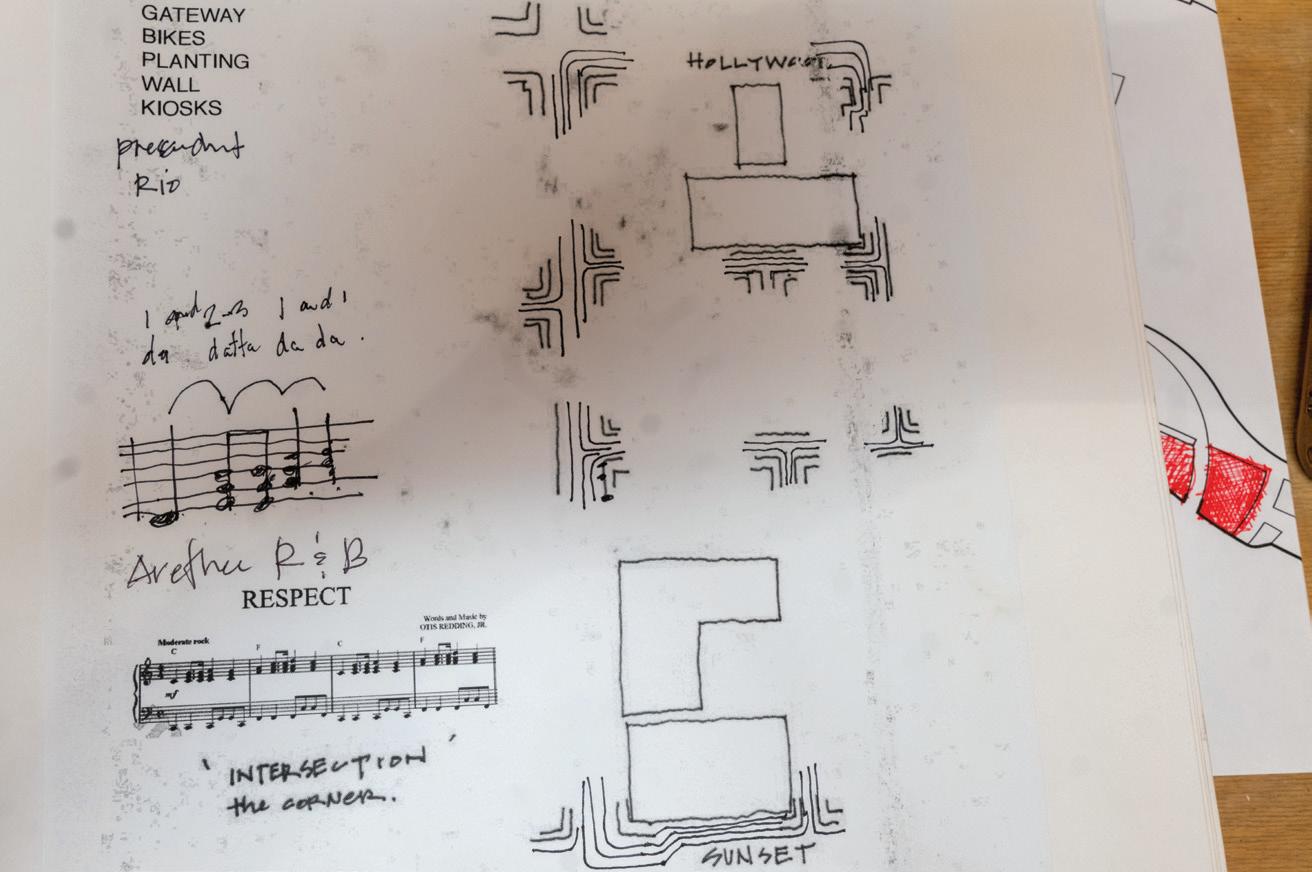

Pages from one of Hood’s many sketchbooks.

Hood's studio and project modeling workshop.

Pages from one of Hood’s many sketchbooks.

Hood's studio and project modeling workshop.

This page: Just outside Fire Station No. 35, BOW, a public sculpture/art installation on San Francisco’s Embarcadero, paying homage to the heroism of fire boats after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

This page: Just outside Fire Station No. 35, BOW, a public sculpture/art installation on San Francisco’s Embarcadero, paying homage to the heroism of fire boats after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake.

urban planning fail to account for “the dynamic economic and social structures of the neighborhood,” he says.

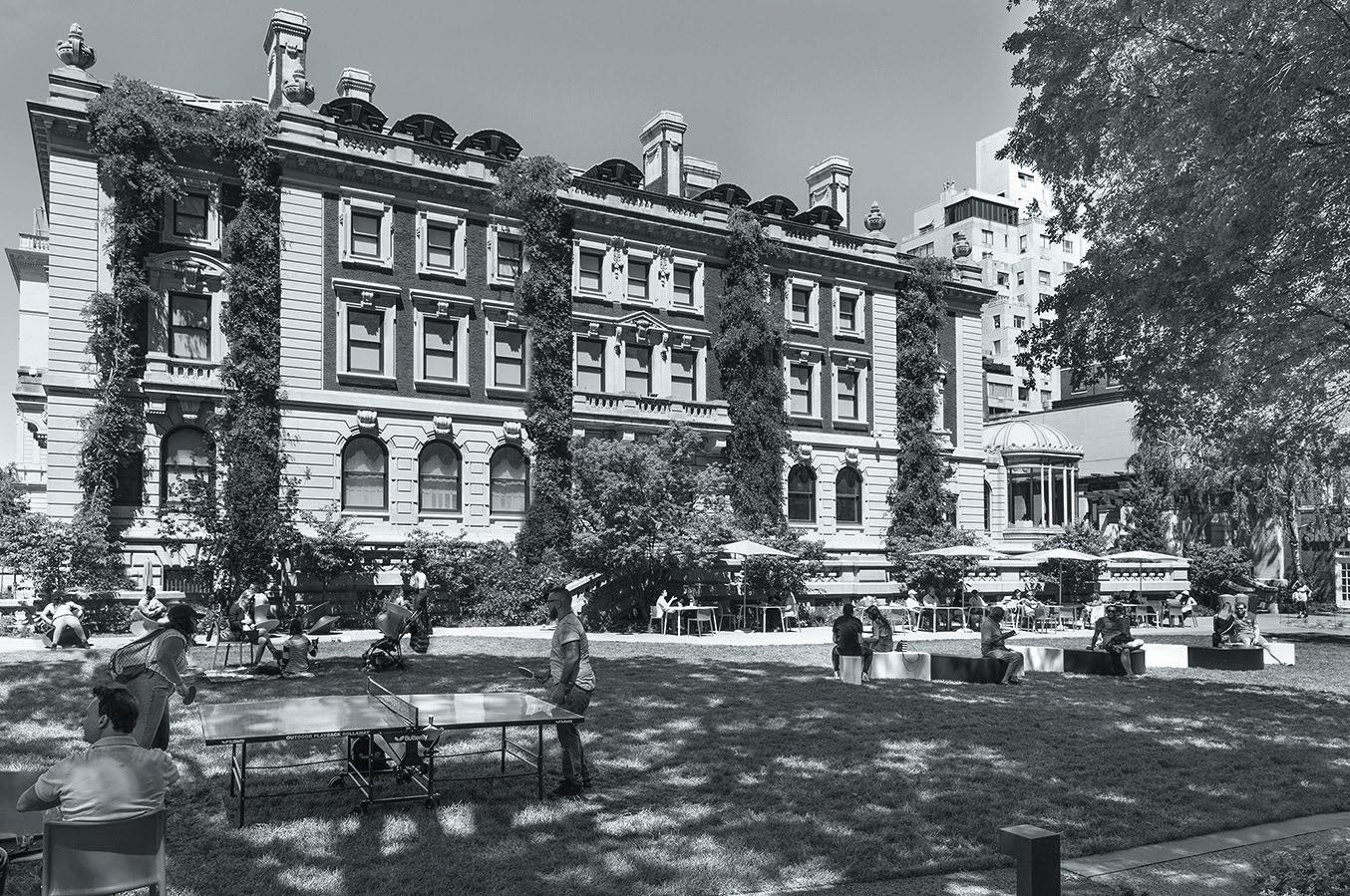

This failure was top-of-mind when, in 1999, Hood was tasked with redesigning Oakland’s Lafayette Square Park, commonly referred to as “old man’s park,” thanks to its popularity among Oakland’s unhoused, including many elderly men. He fought to ensure the redesign met the needs of the diverse population that actually used it, including his adamancy that the new park offer public bathrooms for the homeless, as well as a children’s play area, flower garden, picnic areas and a central water feature. When his firm redesigned the gardens for the Oakland Museum of California in 2021, Hood again set about “breaking the box,” adding new plantings, lighting and gathering areas that softened the hard perimeter, enhancing accessibility and the interface between the museum and the city. Hood set about creating a free public space that welcomed and represented Californians by “investigating what it meant to be a museum for the people,” as the studio’s website notes.

Hood, in his reserved, gentle, cerebral way, has “created his own lane, crafted new language as he celebrates the strangeness of each place,” says New York-based landscape architect Sara Zewde, his former Hood Design Studio colleague and mentee. By transforming run-ofthe-mill public spaces like Lafayette Park and a freeway underpass into inclusive spaces that nurture a sense of community, Hood gives testimony to their resonance and power. Through his artistic meshing of urbanism, public art and landscape design and a process that includes collage, photography, sketching and music—a process perhaps akin to his childhood dabbling—Hood rigorously challenges our understanding of public space. In doing so, he continues to break new ground in designing common ground for the common good.

Hood’s signature audacity and boundary-pushing body of work was also the reason legendary architect Henry “Harry” Cobb of Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, designer of Boston’s iconic John Hancock Tower, picked up the phone in the summer of 2016, called him, and simply said, “Walter, I need you.”

“I didn’t even know what the project was, but when Harry calls, the answer is yes,” Hood laughs. A few weeks later he found himself in Charleston, meeting with Cobb and the team assembled to design the International African American Museum on Gadsden's Wharf, literally the embarkation site, “the threshold where Africans crossed over and became African Americans,” Hood says. Creating a museum to tell the full story of the African diaspora, stories central to the Lowcountry and American experience but often overlooked, had long been a dream of the former Charleston mayor Joseph P. Riley Jr., who first proposed the museum sixteen years before Hood got Cobb’s call.

“We knew Walter was the visionary we needed. He was tired of visiting civil rights and African American heritage sites that didn’t evoke emotion, convey gravity or make him feel much of anything about his own ancestry,” Riley says. “He sensed exactly what this project called for through his simple strategy of coming here and listening and learning.”

Hood, as always, was eager to listen and learn, to put his ear to the ground, but the weight of this project gave him pause. “The IAAM scared the hell out of me. I’d never done anything like it,” he confesses. But he knew Charleston, having designed the courtyard for Memminger Auditorium (now called Festival Hall) in 2008, and a Spoleto Festival USA installation that recreated a rice wetland in the Memminger Elementary School's paved play yard. He knew he could work well given Cobb’s collaborative spirit, and he respected Cobb’s building design: “a spare, elegant, non-rhetorical building that services the landscape without saying ‘look at me,’” Hood says. And he knew an opportunity of this magnitude would likely be his legacy project.

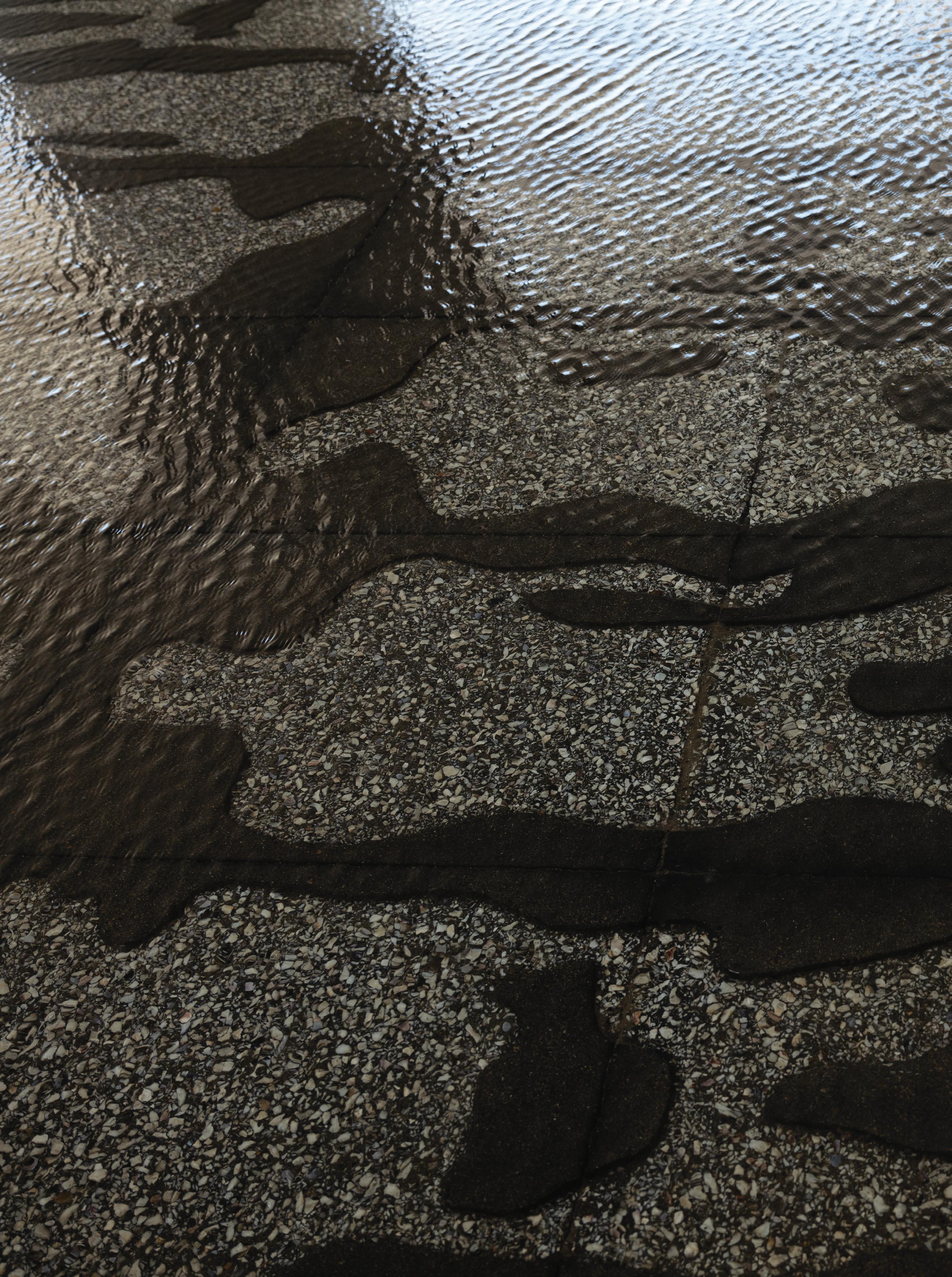

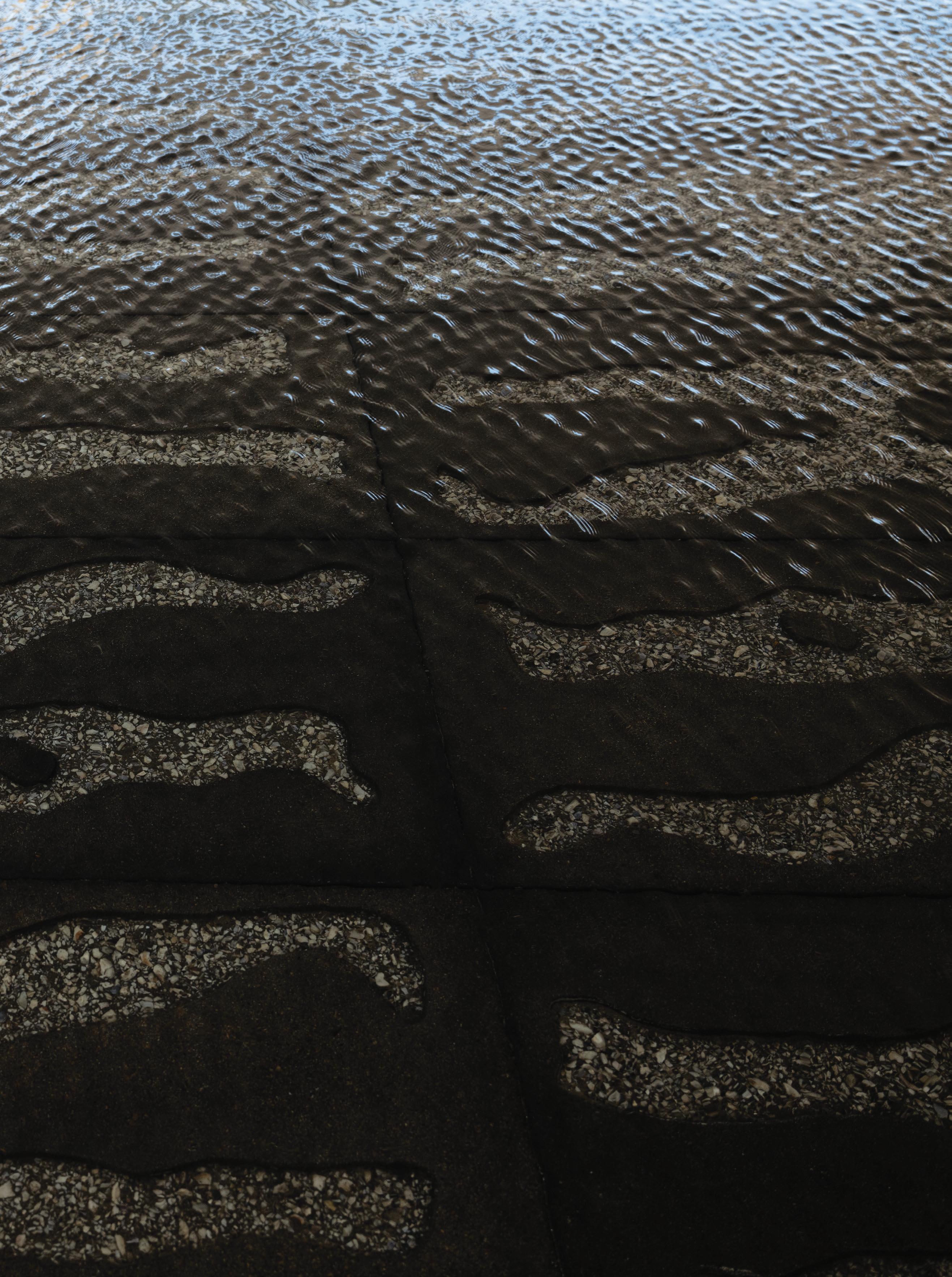

While visiting local historic sites to gain insight into the project, Hood saw a copy of the diagram from the slave ship Brookes on Sullivan’s Island—an image depicting how slave traders could barbarically cram 454 captured Africans into the vessel’s hold. The haunting image reminded him of an abstract African textile, and it sparked his idea to sculpt a similar design on the bottom of an infinity pool and fountain below the lofted building, marking the historic edge of the wharf. Water in the fountain drains and refills several times daily like the tide, ritualizing the sacred ground of the wharf and symbolically collapsing time, melding past and future, honoring African ancestors and the continuation of the diaspora through generations to come.

The fountain/infinity pool below the IAAM features engraved figures that represent captives in the hold of a slave ship. The pool fronts the wharf and fills and empties on tide-like cycles.

The fountain/infinity pool below the IAAM features engraved figures that represent captives in the hold of a slave ship. The pool fronts the wharf and fills and empties on tide-like cycles.

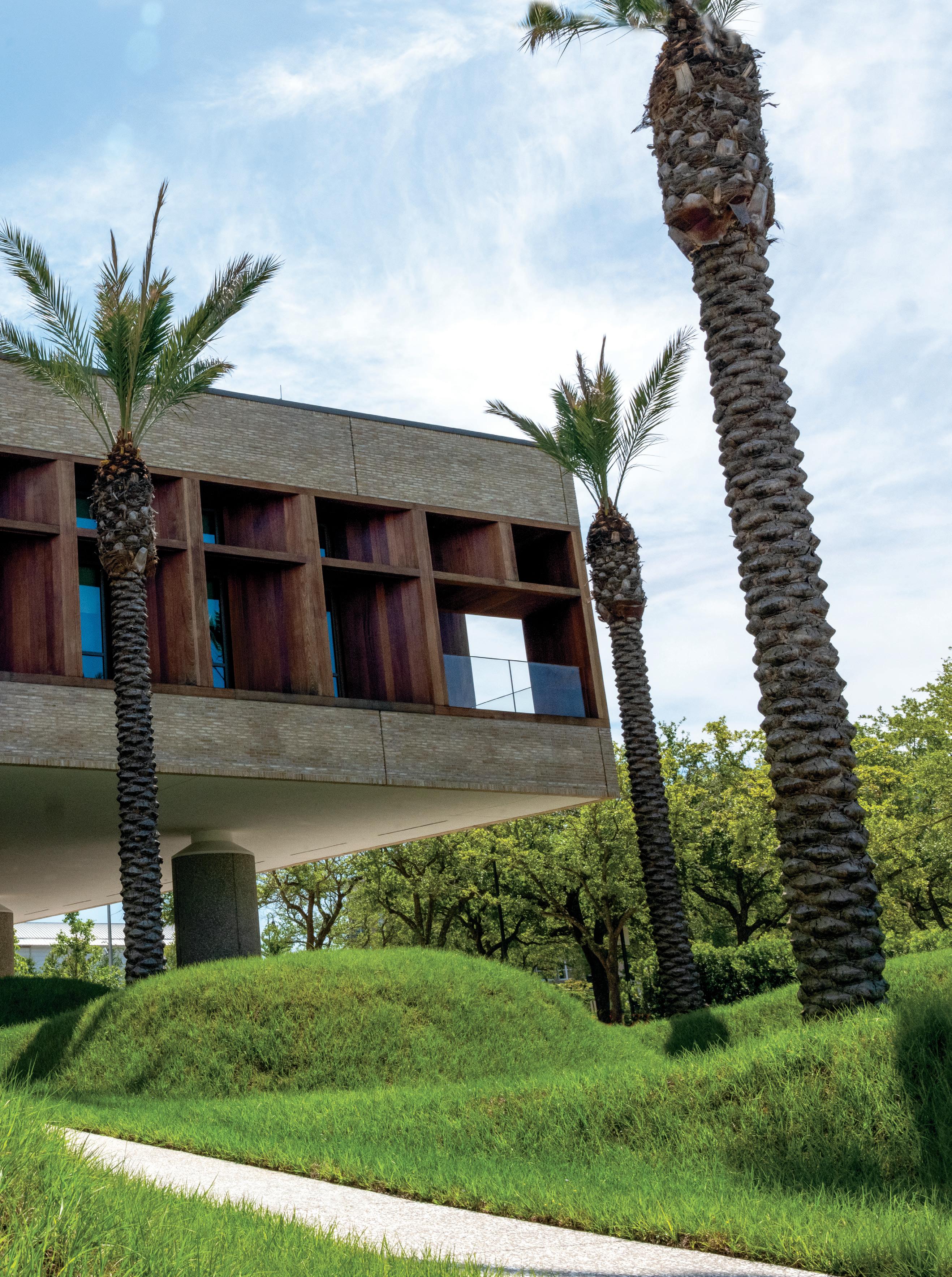

Moody Nolan and Pei Cobb Freed & Partners’ unrhetorical building design “floats” on cylinderlike piers, leaving the sacred ground below open for Hood’s activation. Black marble walls suggest the “hush harbors” tradition—landscapes where Africans would gather in secret to share and keep alive stories from their homeland.

One of a series of abstract forms suggesting humans emerging from bondage.

A serpentine brick wall embraces a stelae garden of abstract monuments to ancestors.

One of a series of abstract forms suggesting humans emerging from bondage.

A serpentine brick wall embraces a stelae garden of abstract monuments to ancestors.

Other landscape design elements include a series of rhythmic dunes suggesting waves or burial mounds on the street side of the museum, a sweeping field of native sweetgrass and an ethno-botanic garden linking West Africa with the Lowcountry, as well as regal palm trees native to West Africa. An obelisk-like stelae garden suggests monuments, purposely undesignated “so visiting school groups can choose which ancestors or leader they might want to dedicate one to,” explains Dr. Tonya Matthews, the museum’s chief executive. On the museum’s east side, a massive black granite wall inscribed with a verse from Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise” marks where a slave warehouse once stood. Archived records recount 700 captive Africans freezing to death while held there.

“I love how Walter has masterfully infused a sense of living into this site of deep trauma,” Matthews says. “The way the sun glistens on the water, the way the water is always in motion and the sweetgrass swaying—you can see and feel the life and energy and continuity in this space. For Walter, every element is imbued with story, which fits the museum, because first and foremost we are storytellers.”

From his North Carolina childhood to his decades practicing in California, Hood as a Black man has grappled with a central question: “are the places that I inhabit valued?” He articulates this in his book Black Landscapes Matter, arguing that “Black landscapes matter because they are prophetic. They tell the truth of the struggles and victories of African Americans in North America. Black landscapes matter because they can be ‘born again,’” he writes. Resuscitating them requires care to “ensure their resonance and power are not lost….We must be audacious in what we bring forward.” Here, on the shore of Charleston Harbor, at the site where thousands of captive people began lives of enslavement, Hood has brought forth a design that is prophetic and redemptive, poetic and audacious. Harnessing the artistry of sculpture, water, stone, dune, sweetgrass, imagery and memory, he brings new life to sacred ground.

Towering palms native to West Africa and gently rolling grass dunes reference coastal connections from Africa to South Carolina and the perpetual ebb-and-flow of history.

Towering palms native to West Africa and gently rolling grass dunes reference coastal connections from Africa to South Carolina and the perpetual ebb-and-flow of history.