THE BURRELL COLLECTION: OBJECTS OF DESIRE

To build the best buildings you have to use the best parts

Award winning Scottish window & door manufacturer providing 'Best Value Solutions' since 1932

KitFix - the original factory fix fenestration system for offsite construction

Extensive innovative product range with cost effective low U-values that can assist in net zero targets

Glazed & unglazed FD30 range now available

Dedicated estimating team & account managers

Fully accredited to the latest BSI standards

The theme of re-emergence dominates the spring edition of Urban Realm, as we welcome green shoots of recovery.

First up is Glasgow’s Burrell Collection (pg 12) which emerges from a five year hibernation. Its transformation has come at the perfect time to reap the dividends of a resurgent leisure economy but has it been worth the wait?

We continue our journey to Paisley (pg 46) via Sauchiehall Street (pg 21) to see how the travails of retail are forcing a reappraisal of how our streets function. Are culture, heritage and entertainment enough?

Across the channel we take a look at the Petite Ceinture (pg 38), a dormant line which has become a battleground for a green revolution in the city.

Landscape steals the limelight at the University of Stirling’s Central Campus

(pg 68) but a new entrance pavilion and improved access show how its true success lies in establishing a new relationship with its setting.

We also pay a return visit to Carbuncle favourite Cumbernauld (pg 82) in the wake of plans to demolish the central ‘megastructure’. A decision which may yet be lamented.

Elsewhere we investigate the importance of retrofitting (pg 54) to meet ever more stringent sustainability goals and recount the unsung timber story of Rogers Stirk Harbour + Partners (pg 88), following the passing of Richard Rogers.

It’s been a breakneck start to the year as we all strive to make up for lost ground but this reassures that whatever challenges lie ahead we have the wherewithall to meet them.

John Glenday, editor

The ultra-compact surface, Dekton® by Cosentino has been selected for use for the Vantage Point Archway Tower redevelopment project in London

Find

25 Year Warranty.

Project Archway Tower Architect GRID Architects Dekton® Surface 3,000 m2 Façade Dekton Danae Natural Collection

Bigg Regeneration has taken forward the next phase of development at Dundashill, Glasgow, with the submission of plans by Stallan-Brand for 79-canalside homes arranged around a sunken garden to complement planned start-up business units.

The joint venture body is owned by Scottish Canals and PfP Capital and managed by Igloo Regeneration. It is delivering a broader 600-home masterplan for the hilltop site, seeding a new community around the burgeoning urban sports destination.

Crosslane Residential Developments have appointed Hawkins\Brown to deliver serviced residential apartments on a brownfield site off Ocean Drive, Leith.

Billed as a new form of living Ocean Point 2, adjacent to Farrell’s Ocean Point office block, encourages tenants to use their rooms solely for sleeping in, with a host of communal spaces and facilities offered within the building as part of the allinclusive monthly rent that covers everything from utilities to a gym membership.

The Royal Zoological Society of Scotland has won approval for the erection of a discovery hub at the Highland Wildlife Park, creating a new gateway to the Cairngorms National Park Comprising an enlarged restaurant and shop with a wildlife and night sky monitoring station the development by Baxter Studio spans three buildings designed using locally sourced and sustainable materials.

Build to rent operator Get Living and Stallan-Brand architects have submitted plans for an intergenerational community on the 7.5 acre High Street Goodsyard site in Glasgow.

Combining 823 build to rent apartments and 687 student rooms the development will improve connectivity between High Street and Bell Street.

Soller Group and Mosaic Architecture & Design are seeking to erect the second phase of planned office development at Carrick Street in Glasgow’s Broomielaw office district.

Rising through 17 floors the taller element will provide over 270,000sq/ft of gross internal floor space and flank a new public plaza.

DS Architecture has applied to build a detached three-bedroom home adjacent to 20 Hillpark Avenue in Blackhall, Edinburgh.

A sensitively scaled design in line with adjacent properties is planned for the 1930s slice ofsuburbia which includes a mix of mid-century bungalows and more recent development.

Proposals to upgrade Queen’s Park Football Club’s training ground at Lesser Hampden to a fully functioning stadium have been filed by Holmes Miller Architects

Accessed from a glazed black brick entrance pavilion off Letherby Drive the expansion will increase capacity at the Glasgow ground to 1,450 by introducing spectator stands to the east and west, facilitating competitive league and cup matches.

Ardgowan Distillery has released its latest plans for a striking production facility and visitor centre overlooking the Firth of Clyde

The carbon-negative timber and steel structure has already been submitted for consideration by Inverclyde Council and will be built by specialist distillery engineers Briggs of Burton for completion by 2023.

56Three Architects have obtained planning consent for the erection of a modest workshop and studio overlooking Lower Largo Beach, Fife.

Housing an open plan workshop or garage on the ground floor the property rises via a top-lit stair at the rear to a studio gallery and a sheltered roof terrace above, offering elevated views across Largo Bay.

The wedge plan workshop will bookend the east of the village.

Ladybank Developments and Michael Laird Architects have received planning consent for a student accommodation development at Haymarket Yards, Edinburgh.

The decision clears the way for the applicant, a joint venture between GSS Developments and London & Scottish Property Investment Management, to deliver 153 studio apartments on a 0.16acre site, including a roof terrace and shared gardens.

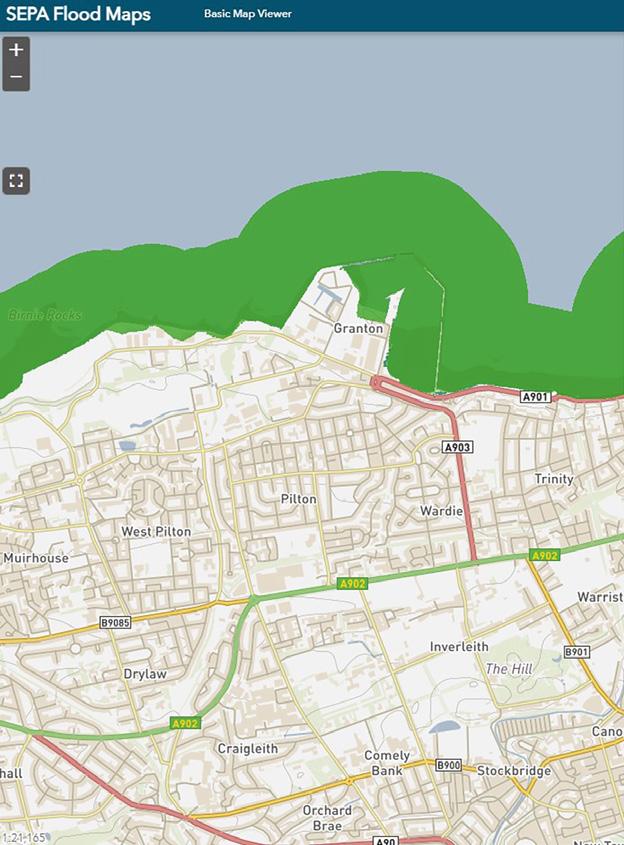

The City of Edinburgh Council has granted consent to a pilot housing project at Granton Waterfront that will trial the delivery of affordable ‘net zero’ homes.

The Edinburgh Home Demonstrator initiative sees CCG and Anderson Bell Christie Architects team up to deliver 75 homes and three commercial units.

An application for planning in principle has been filed for the expansion of Portree, the principal settlement of the Isle of Skye, to address a chronic shortage of affordable housing.

Rural Design has prepared a master plan for 250 new homes on behalf of

Lochalsh and Skye Housing Association to extend the northern outskirts of the settlement at Kiltaraglen over the next two decades.

Boasting an elevated setting above the established urban centre, offering expansive views towards the Cuillins.

The University of Glasgow has moved to extend the presence of a temporary modular structure housing the displaced department of mathematics and statistics for a further five years beyond the approved cut off of February 2022.

Several architectural modifications are planned by jmarchitects in recognition of its continued role, centred on the incorporation of white ‘chalk’ text on dark cladding panels to evoke a giant blackboard. This overlaid text repurposes various computational symbols as floor decals and murals applied to laser cut aluminium panels.

Soller Group with Mosaic Architecture & Design have staged a virtual public consultation into proposals for Glasgow’s latest build to rent scheme.

A 1.3-acre site at 144 Port Dundas Road, comprising a third of a city block in Cowcaddens, has been identified for the delivery of the 16-storey apartment complex, heralded as an essential component of efforts to repopulate the city centre.

A long-awaited report into a devastating 2018 fire that all but obliterated the Glasgow School of Art has found that the cause of the conflagration remains ‘undetermined’.

The Scottish Fire & Rescue Service says physical evidence relating to the source of the fire was destroyed by the same blaze, rendering it unable to attribute an official cause for the record.

Clydebank Housing Association has commenced delivery of 18 homes for social rent on a former bowling green.

The JR Group has moved on-site with a mix of one and two-bedroom flats at Clydebank Bowling Club for the £3.2m build A design team including Mast Architects Cowal Design and Carbon Futures will help to deliver the project.

A disused Highland mill is set to give rise to a new distillery under plans filed by Dunnet Bay Distillers and Organic Architects.

The 200-year old property in Castletown will be subject to a £4m refurbishment to accommodate a distillery and visitor centre, a stone’s throw from the

Network Rail has filed plans for a visitor centre and reception hub at the foot of a vertigo-inducing elevated Forth Bridge walk.

Plans led by Arup with WT Architecture and The Paul Hogarth Company call for the UNESCO World Heritage site to be augmented by a reception centre where thrill-seekers can ascend the South Tower via maintenance gantries.

The revised plans take an ‘economical’ approach with a light weight building.

companies current headquarters. Run by husband and wife team Claire and Martin Murray the distillery owns the Rock Rose Gin and Holy Grass Vodka brands, acquiring the mill last year to provide expanded premises to cater for recent growth.

Plans for a net-zero apartment block have been brought forward for Gullane, East Lothian, to replace an unlisted bungalow on Main Street.

Studio IMA (on behalf of B&Y Developments) proposes to erect four, three-bedroom apartments of a height and scale more consistent with its setting, together with private parking and gardens on the 2.5-acre town centre plot. Set back 8m behind the building line the apartments adopt a distinctive roof geometry.

Dumfries & Galloway Council has awarded conditional consent to 89 homes in Locharbriggs Dumfries, on behalf of a registered social landlord.

Dumfries and Galloway Housing Partnership have identified a former haulage depot for the build which seeks to establish a characterful mix of family homes for social rent led by Collective Architecture and main contractor CCG Built around a ‘green-blue’ network of landscaping and SUDS the masterplan works with the existing lie of the land to segregate vehicle traffic along a single ‘High Street’ separate from active travel routes, connecting a sequence of community squares and spaces.

NHS Highland has completed work on the first of two planned community hospital’s in the region, a £20m facility in Aviemore

Badenoch and Strathspey

Community Hospital houses

24 inpatient beds, 12 consulting/ treatment rooms, a minor injuries unit, outpatients, physiotherapy, NHS dental suite, GP services, x-ray facilities the hospital also serves as a base for the Scottish Ambulance Service

Delivered by contractor Balfour Beatty with Oberlanders

Architects and Rural Design the 120 room hospital has been fitted out by furniture specialists

Deanestor

A former shop unit at 49 Cochrane Street in Glasgow, which has lain empty for over a decade, has begun a new life as an accessible headquarters for the Diocese of Glasgow and Galloway, part of the Scottish Episcopal Church.

The 310sq/m commercial space in the B-listed Italian Centre, last in use as an office by Page\Park Architects, has been retrofitted by Graeme Nicholls Architects to provide a flexible environment for working and gathering over basement and ground floors.

Plans for a bespoke farmyard home on the Isle of Arran have been lodged by Inkdesign who intend to clear a dilapidated cottage, oil container and storage sheds adjacent to Ardlui House to make way for a new dwelling.

Occupying an elevated position some 70m above sea level the site offers extensive views to the Holy Isle and Goatfell, with a bank of mature trees sheltering the site to the west. Salvaged stone will be incorporated into the landscape design.

Mast Architects and CCG have returned with revamped proposals to erect 46 apartments for affordable rent in Govan Superseding a prior application from 2021 the latest submission for the 0.26-hectare island car park, which would host two apartment blocks and shared amenity ground with just 15 parking spaces remaining. Both blocks will stand as mirror images of one another with feature balconies projecting from the prominent gushet end. A footpath will connect Golspie Street and Langlands Road.

A Bishopbriggs medical practice is seeking urgent additional consultation spaces to meet the needs of a fast-growing population in East Dunbartonshire.

Kenmure Medical Practice on Springfield Road proposes to extend their present premises to increase GP and primary care capacity with three additional consultation rooms.

The proposed single-storey extension by S2 Architecture adopts two small ‘pyramid’ roofs similar to the existing surgery with tall box frame windows forming a civic frontage to the street.

David Chipperfield Architects with 3DReid and Loader Monteith have prepared detailed plans to transform the former Jenners department store in Edinburgh into a 96 bedroom ‘lifestyle’ hotel.

The category A-listed Princes Street building has been acquired by Danish billionaire Anders Holch Povlsen to introduce a boutique hotel on the upper levels while retaining The Grand Saloon below as part of a reimagined retail and hospitality experience.

The St Vincent Crescent Conservation Area of Finnieston could be joined by 15 apartments for Glasgow West Housing Association.

Coltart Earley Architecture has been tasked with repairing a hole in the streetscape by mimicking stone string courses and entrance porticos of its neighbour in addition to solid eave parapets, storm doors and cast-iron work.

The City of Edinburgh Council has launched a consultation into its plans to repurpose a Granton gas holder into a waterfront public space.

Views are being sought on how best to utilise the space after securing funding from the UK Government’s Levelling Up Fund to restore the B-listed frame as the centrepiece of a coastal park.

Part of the 15-year Granton Waterfront masterplan by Collective Architecture the proposals call for a sustainable coastal town to be built with the gasholder standing as the lynchpin of an active travel network and green space.

Works to refurbish and extend a historic B-listed Jute mill in Dundee city centre are to enter a second phase with proposals to restore the Victoria Street/Dens Road ‘sawtooth’ profile to its original appearance.

Again led by James Paul Associates the latest improvements to Eagle Mill will marry preservation of surviving fabric, with ‘robust’ interventions to facilitate its new residential nature on secondary elevations such as Lyon Street

‘Light touch’ changes see windows restored to their original proportions, with additional steelwork supporting the retained wall, behind which an ‘industrial’ walled garden will be located for the benefit of residents.

Plans for an urban distillery in the heart of Campbeltown have been drawn up by Bowman Stewart Architects.

Work has been completed on the development of 23 affordable homes at St Ninian’s Crescent in Paisley on behalf of Link Group.

Delivered by the JR Group with Renfrewshire Council and Hypostyle Architects the work comprises a mix of 19

houses and four cottage flats, all of which are occupied.

Built on brownfield land later adopted by the local community as an informal route between shops on Rowan Street and St Ninian’s Road the project maintains this access with improved landscaping.

The Dal Riata Distillery is to be built on Kinloch Road with a capacity for producing 850,000 litres of pure alcohol per year using local barley grown at the historic Dunadd Hillfort Centred on a dramatic still house with floor to ceiling glazing and a viewing gallery overlooking Campbeltown Bay the distillery will hark back to the turn of the 20th century the town hosted no fewer than 30 distilleries.

Scottish Borders Council has shared plans for a £46m replacement for Peebles High School following a devastating 2019 fire.

Stallan-Brand Architects have been brought on board to oversee the new building, which will introduce a range of

educational and community facilities to the town when it opens in 2025.

The tandem build solution is set to break ground later this year, rising on the footprint of an existing rugby field, evoking the form of a ‘country estate’ property typical of the surrounding area.

Link Group has broken ground on 82 affordable homes designed by Stallan-Brand at Upper Achintore, Fort William, as part of an overall masterplan for 319 homes.

Led by the JR Group WGC and TSL Contractors the project will deliver a mix of terraced homes, cottage flats and two wheelchair-accessible bungalows on an elevated 23-hectare site.

Acquired by the affordable housing provider in 2019 the development will provide predominantly terraced housing finished in timber boards.

Plans for an innovative coliving residential home in Aberdeen have been brought forward by Camphill Schools to provide accommodation for charity workers wishing to remain associated with the movement in later life.

A consultation into plans to redevelop the derelict Shawbridge Arcade on Pollokshaws Road, Glasgow, to provide 71 apartments has been launched.

The Wheatley Group with Coltart Earley Architecture proposes to demolish the 1970s arcade to erect eight new-build blocks of up to five storeys.

Kelvin Properties have surfaced plans for a ‘gateway to Paisley’ apartment block on the site of a former office block on the corner of Saucel Street and Lonend. Incorporating shared spaces and hybrid office zones the development of 67 apartments by Mosaic Architects comes with solar PV panels and electric charging.

The co-housing community by Taylor Architecture provides 20 apartments with common house features to encourage friendship and companionship among occupants while maintaining their independence.

Feilden Clegg Bradley Studios have trailed plans for a ‘sustainable urban neighbourhood’ in Finnieston , Glasgow, of between 400-425 homes.

A 0.95-hectare site bounded by Minerva Street Finnieston Street and West Greenhill Place has been purchased by Keltbray Developments to accommodate hundreds of build to rent apartments alongside flats for private sale. Focussed on improving pedestrian and cycle permeability to encourage carfree living the development will incorporate a new east-west street and ground floor public spaces and a central plaza overseen by Open to establish a sense of place.

Edinburgh planners have given the goahead to the refurbishment and alteration of a semi-detached villa at Cluny Drive in Edinburgh’s Morningside to take full advantage of a rear garden. DSArchitecture proposes to demolish an existing sunroom and cut a large new opening to the rear elevation. An adjoining annexe will be given a complementary makeover through internal reorganisation, an altered roof and the addition of zinc cladding.

Expanded plans have been aired by Wilson & Gunn for a 10,000 capacity waterfront arena in Dundee that would provide a home for live music, e-sports events, conferences and other events.

The vision calls for the Mecca Bingo site on the Nethergate to house the arena with an adjoining temporary car park at Yeaman Shore hosting a 70-room hotel, a significant scaling up of ambition from a 2018 proposal for a 6,375 capacity venue alone.

Detailed planning consent is sought for the first phase of a £100m overhaul of the Ocean Terminal shopping mall in Leith.

Detailed plans by Keppie Design with LDA on behalf of the Ambassador Group seek to reimagine the 20-year old retail complex as a community-focused facility by demolishing the north wing of the current building to establish a new outward-facing frontage defined by new retail, leisure and public realm.

Watkin Jones Group has lodged plans for a car-free rental community at New Mart Road, Chesser, with the City of Edinburgh Council.

The brownfield build to rent project replaces former livestock sheds, latterly in use as indoor bowling and football venues, with a mix of homes, student housing and

community facilities.

Led by Manson the work will see a ‘significant’ proportion of iron frames from listed cattle sheds retained and incorporated into the overall development after studies found that the costs of maintenance, repair and upgrade of the sheds were unsustainable.

A public consultation to transform Edinburgh’s Cameron Toll Shopping Centre, currently designated as a commercial centre, into a neighbourhood centre has been held.

3DReid have prepared a radical masterplan for the aging out of town mall, opened in 1984, to take account of fast-changing mobility and shopping patterns. This would see the current site, which alongside the mall comprises two drive-through outlets, a petrol station, service yards and a 1,000 space car park remodelled to face out to the Craigmillar Park Conservation Area

KR Developments and 56Three Architects have opened a public consultation to deliver 230 student bedrooms at South Ward Road , Dundee

A fragmented urban block near Dundee House will be knitted back into the streetscape by establishing a hard edge while retaining an interior courtyard as outdoor amenity.

The Highland Council has brought forward plans to redevelop the Meiklefield area of Dingwall , demolishing 114 existing homes and replacing them with 117 new build properties.

The local authority has enlisted HRI Munro Architects for the rebuild, which will replace ‘four in a block’ properties dating from the 1960s in phases through to 2025.

Arnold Clark and Page/Park have opened a consultation to transform a former garage at 1 34 Nithsdale Drive, Glasgow, into a mix of 106 apartments for general sale.

An island site overlooking Strathbungo Junction will be redeveloped by the car dealership and a future development partner to ‘fill the gap’ in the streetscape, including 100% parking

THE RE-OPENING OF THE BURRELL COLLECTION, IN TANDEM WITH THAT OF SOCIETY AS A WHOLE, PROMISES TO REKINDLE A LOVE AFFAIR WITH THE PUBLIC TARNISHED BY LEAKS AND LIMITED DISPLAY CAPACITY. HAS THE IMPERFECT BEEN MADE PERFECT? URBAN REALM SPEAKS TO JOHN MCASLAN TO FIND OUT HOW A GLASGOW INSTITUTION HAS BEEN RETOOLED FOR THE CHALLENGES OF A NEW AGE.

Glasgow’s Burrell Collection has emerged from an extended hibernation in a more expansive form following a £68m refurbishment at the hands of John McAslan & Partners. The A-listed landmark building was widely praised as a jewel in the crown of the city’s cultural offer but suffered in later years from dwindling visitor numbers, unchecked solar gain from expansive glazing and constant leaks.

Architectural sentiment has similarly blown hot and cold, a point not lost on executive chairman John McAslan who researched the history of the building thoroughly upon taking on the commission. “It was received phenomenally well in some quarters and less well elsewhere, there’s a rather unpleasant piece written by Michael Wilford (a critique of the Burrell Museum published in The Architect’s Journal in 1983), but it was hugely successful and had a million visitors.”

Referencing John Julius Norwich in the contemporaneous Burrell Collection book of 1983 McAslan points to the large amount of white space that became apparent when looking at plan drawings. “The plan effectively shows up the voids at the elongated entrance, courtyard, lecture theatre and temporary gallery. Why have these voids? The turn into the courtyard is a dead-end and you have the Hutton Rooms around its edge. The lecture theatre beyond it and the temporary gallery beyond that was generally shut because the lecture program was infrequent and the temporary gallery, which is a beautiful space with that

gorgeous eastward louvred pitch, never opened.”

The volume of perceived dead space is cited by McAslan as a contributing factor to the declining popularity of exhibits such as the Hutton Rooms (three furnished rooms salvaged from Hutton Castle in the Scottish Borders) in the dying days of the old Burrell, shunned by visitors because it was ‘on a route that you would miss’ and suffering from a paucity of things to see. “The Hutton Rooms were barely used”, he observes. “There were about five people per day visiting the smallest of the Hutton Rooms and maybe 15 or 20 a day for the biggest. You couldn’t access them. The drawing-room, the biggest of the three rooms with dual access from the Walk in the Woods (otherwise known as the North Gallery), was more embedded in the fabric of the building and more satisfying because it forms the northern edge of the courtyard.”

To address these challenges McAslan cites five principal changes; namely a new entrance, agora, temporary gallery, mezzanine and stores. The new entrance was a particular bone of contention in some quarters with McAslan acknowledging that John Meunier, co-architect of the 1972-83 Burrell alongside Barry Gasson and Brit Andresen, ‘wasn’t particularly supportive’. Meunier broke ranks in 2017 to issue a public appeal urging retention of more of the original fabric, principally the extended entrance sequence and restored Hutton Rooms.

Such sentiments were given short shrift by McAslan who

points to the more pragmatic approach of Gasson, who was happy to entrust the Burrell baton to a new generation save for one esoteric detail. McAslan recalled. “His concern was the planting in the courtyard. Originally, there were four trees. But they died and were replaced by four bushes that he hated because they weren’t looked after. He and Meunier had a falling out and there’s a story that when they both visited the building, at the same time, they danced to avoid one another.”

Ultimately it was client Glasgow Life that mandated much of the changes, with practical necessities overriding romantic ideals, sparking a to and fro with the architect to alight on a middle ground that would be acceptable to all. “There was a lot of pressure on Glasgow Life to do certain things to the building to open it up. Most of which I think were fine and one or two that we didn’t particularly want. They wanted the new entrance to be midway in the building and we said you couldn’t do that because it meant you’d have to prop up the landscape. But we did concede that an additional entry in the corner where the two meet could work axially on the Hutton Rooms on the basis that the original entrance route would remain open.

“The original entrance didn’t work, it really didn’t work. I think that while it was elegant as an architectural entrance there are issues of access. It was a piece of theatre and that’s fantastic. The reality was though that we felt there was no reason that this piece of theatre could not be maintained and supported by

a more straightforward gathering space for group visitors, not necessarily in a linear procession.”

That line of thought has delivered two additional entrances on the lower floor from the cafe and at the base of the central public space (agora). An enlarged retail space and cafe also tick the necessary commercial boxes while opening up the hall to better serve gatherings and collections. The agora makes use of a little-used lecture theatre to house stained glass displaced from the new entrance and it connects to open access stores, a temporary gallery and a cafe on the lower floor. This latter change illustrates the fundamental vertical shift at play in a collection that has always been defined by its horizontal relationship to Pollok Park as the building is made to work harder from the roof to the basement.

Every square inch of the building has been accounted for in the redesign to maximise floor space to house the collection, substantially increasing the 1,800 objects (20% of the collection) that are available to view. “That percentage was too low for various economic and curatorial reasons”, acknowledges McAslan. “It was rare for any rotation of the collections to take place and it meant that the majority of the other seven thousand objects were in storage. Now you get a much more rounded sense of Burrell’s collecting by having more objects on display.”

By opening up the ground floor in its entirety the number of objects on display now stands at 5,500 with the remaining

9,000 items available to view in open access stores and which will be rotated through the main display from time to time. Greater flexibility also permits the temporary gallery to accommodate events, with a conservatoire band making use of the agora for a relaunch dinner. Long-term however it will permit recurring weekend talks and concerts to be hosted, keeping people interested long after they’ve seen the exhibits.

A ‘big win’ for McAslan was the first-floor mezzanine spaces which have gone from a few relatively modest impressionist galleries to utilising the entire floor space as a ‘makers and making’ display which enables visitors to explore the collection through the eyes of the artisans behind the art. This has been achieved by pushing staff rooms up into the eaves and relocating community spaces into an independent wing that is closed off out of hours behind a glass door. “It means that truly the Burrell is now a building of three floors, not one. There was evidence that people coming into the Burrell went straight for the cafe, very few people went anywhere. It had to work harder because whether or not one liked it the presentational and rotational aspects of the building limited the interest of the public. There were 125 thousand visitors in its final year and this was decreasing, not just because it was leaking but because there wasn’t enough to see.

“People had tired of it and the way of presenting art had changed, there needed to be more story-driven exhibits. You

could be sniffy and say the purity of the art is being immersed in other narratives but there’s another story of Burrell the collector and how things were made and where they came from. I think for a younger audience in particular it enriches the story of what is a very eclectic collection. It’s appropriate to try and knit all this together in some way. People say the Burrell collection is world-class. Well, it is world-class but it’s a world-class private collection. It’s not the Metropolitan Museum of Arts, the British Museum or the V&A. It’s an eclectic collection by one guy who bought some ships and bought art to build a collection and it ends at Rodin in the 1880s and has elements within it that may or may not interest you like armour and porcelain and cut glass but when I walked around more recently it struck me, it felt like a collection amassed at auction. You had 23 Deygas, a beautiful Cezanne and early Renaissance tapestries but to create a new audience it needed more.”

An eye-watering repair bill of £25m is cited for the roof and facades as well as modernised energy systems, leaving around £5m to cover all the other interventions. “The first part was repair and energy enhancements”, says McAslan. “The second part was facilitating a large number of objects to be displayed at any one point and for all of those objects to be within the building for rotation, all while protecting the grade A nature of the building. Beyond that was the budget for representing the collection, which is significant and additional.”

The refit provided an opportunity to upgrade power, heating and lighting while repairing notorious leaks which bedevilled the museum in its previous incarnation. That process saw existing glazing frames retained, saving over 8.5 tonnes of aluminium, part of a package of facade enhancements that have seen the Burrell Collection achieve a BREEAM Excellent rating.

So often buildings are designed to take a back seat to the objects within but the Burrell encompasses a lot of the exhibits within the fabric of the building itself. How did the practice respect the built backdrop? “The embedded architectural fragments add a level of richness. They are very curious things but they sit so beautifully and the Hornby Portal is just magnificent with the sandstone cleaned. In any listed building, whatever we do, apart from removing later accretions, we are impacting the original fabric. We’re not there to be arrogant and try and make it better. We’re there to try and limit damage to the original concept and respect what existed through the change.”

The landscape was always critical to the success of the building with attention drawn to the lush surroundings as much as the objects within. How does the new look Burrell address its setting? “We created a very simple bound gravel terrace to the cafe which I think will work as an extension of the cafe in the summer. Level with the grass there’s a terraced seating area with three lines of stone and benches, you are encouraged to step through the landscape into the building. On the upper level, there is a rolling forecourt or piazza which will host events. It will be an external congregation space, which it didn’t have before.”

Delayed around nine months following a series of pandemic related interruptions the Burrell is opening at the perfect time to

capitalise on a society re-emerging from stasis but it remains to be seen how people will respond, McAslan himself will reserve judgement until he sees the building in use. But bringing logic and reason to bear on a building that suffered as much as benefitted from its extravagant design has created a far more functional museum while retaining the theatrical aspects which made it so unique.

As a counterpoint to the Macintosh’s sorry tale of fire and flood, the Burrell stands as a testament to the fact that no problem in architecture should be insurmountable, ensuring that the rare beast of a building designed for aesthetics over practicality can live on even in today’s cost-conscious world.

Landscape Architect: John McAslan + Partners

Structural Engineer: David Narro Associates

Services / Fire Engineer / BREEAM: Atelier Ten

Façade Consultant: Arup

Cost Consultant: Gardiner & Theobald

Project Manager: Gardiner & Theobald

Main Contractor: Kier

Planning Consultant: John McAslan + Partners

Acoustic Consultant: Sandy Brown Acoustics

Access Consultant: David Bonnett Associates

Exhibition Designer: Event Communication

Catering Consultant: Jo Headland

Retail Consultant: Seeking State

Wayfinding / Signage Designers: Studio LR

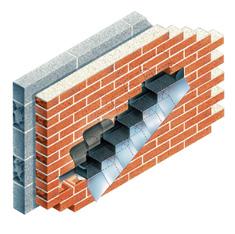

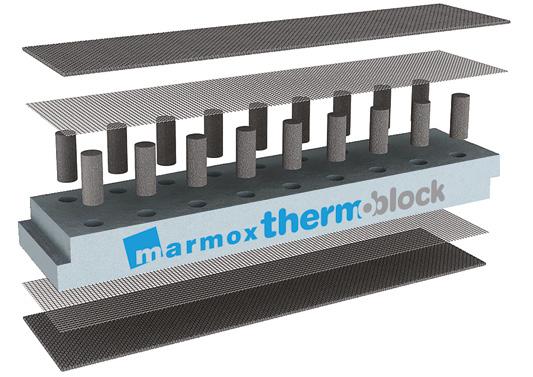

WINDOWS AND DOORS

At NorDan we are happy to be the forerunners in the transition to a sustainable construction industry. We try to lead by example - we’ve done it for nearly 100 years.

NORDAN.CO.UK

W R T C E T B D R I E E A H I Y O E N

PATRICK MACKLIN, DEPUTY HEAD OF THE SCHOOL OF DESIGN AT THE GLASGOW SCHOOL OF ART, UNDERTAKES AN INFORMAL SURVEY OF SAUCHIEHALL STREET’S MULTIPLYING VACANT, VOID AND BROWNFIELD LAND TO SEE WHETHER THE AVENUES PROGRAMME HAS PUT IT BACK ON TRACK.

Sauchiehall Street in Glasgow stretches 1.5 miles (2.5km) from the city’s central core to Kelvingrove in the west end. En-route it is criss-crossed by other streets, the names of which evoke flowers, gemstones, waterways, even Hope itself. In recent years, if certain headlines are to be believed, feelings of the latter have been in short supply, however closer inspection offers alternative readings.

Things change. The street’s central section, from the city centre to Charing X, with its mid-nineteenth century shops, offices, recreational spaces, tenement flats and free-standing houses, was once a mere pathway through a willow grove. A casual survey of its current

early twenty-first century manifestation reveals a place in flux, expressed through sharp contrast and surprising blends of occupancy. Presumptions abound that the place enjoyed better days, before being blighted by an undeserved super-concentration of vacant and brownfield sites clustered between the mall in the east and the motorway in the west. Considering ongoing shockwaves from the financial crisis, radical brick-andpixel alternatives to the high-street and, more recently, the impacts of the pandemic, it is astonishing that it persists at all.

Beginning with the 1970’s pedestrianisation of the street’s easternmost blocks, prioritisation of pavement over highway has extended westwards with the recent piloting of the city’s ‘Avenues Project’. As well as introducing comprehensive traffic-calming strategies, this provides a strong connecting thread through the neighbourhood and firmly asserts the importance of people over motorised vehicles. In January of this year a long overdue adjustment to the Highway Code (rules H1–3) gave priority to pedestrians, then cyclists (and people on horseback) at road junctions. In a gridded city such as Glasgow this has a significant impact on the ebb and flow

of people. Despite this, an impressively enhanced linearity remains bisected or awkwardly abutted by perpendicular routes, as a result, navigation on foot or on wheels, is an episodic experience and transitions between its various segments are far from gentle segues.

There is dramatic contrast between the north and south sides of the street. Active retail units, banks, barbers, bars, and restaurants are evenly distributed between each. Supermarkets dominate the north side, as do pharmacies. The jewel-like Mackintosh designed tearooms face north. Restaurants and cafés are evenly shared but fast-food is doubly concentrated in the south. The sunny side houses a military museum, ‘Scotland’s Biggest Nightclub’, a university dental hospital, the CCA (Centre for Contemporary Arts), Savoy Market and three gap sites. Newsagents are predominant across the road, one incorporating a Post Office. Nearby, behind the façade of the former La Scala cinema, is one of the few remaining and largest bookshops in the country. Notwithstanding this plethora of activity there is a tangible sense of vacancy here.

Glasgow, in contrast to other cities, has a comparatively small number of its citizens living in its

centre, moreover it has experienced an especially slow return to office working. Considerable numbers of former commuters, at least those able to continue operating remotely are either choosing to do so or are compelled to. As a result, the presence of people may never recover to pre-pandemic levels, this is bad for business, and an unnatural hush descends on the place by early evening. Heading into spring, with the pandemic and associated restrictions further easing, the number of vacant units, ranging in scale from compact to substantial, is haunting. Empty shop units and silent bars sit either in clusters or monumental isolation. Evenly sprinkled Deco era buildings which, last century, housed some of the areas celebrated high-street stores, department stores and banks, including C&A M&S, Watt Brothers and Bank of Scotland, are emptied or may soon be so. In the six years since BHS collapsed eight out of ten of this type of retail space has vanished from our cities.

There is an understandable nostalgia for landmark retail, and department stores especially. They often occupy prominent sites within provincial cities, providing legibility and expression of place, but it is useful to remember that, once upon a time, they might have absorbed the

haberdasher, the milliner, and the perfumier, just as the supermarket consumed the butcher, the baker, and latterly, the candlestick maker. Sentimentality cannot insulate city centres from the impact of the seismic shifts in shopping habits that have only accelerated over the last decade, particularly those of the technologically facilitated variety, and became universal during the pandemic.

Throughout the pandemic the interior was subject to unprecedented levels of attention as vast numbers of people across the world were ordered to stay at home and streets emptied. When we could eventually go out, masked, we tentatively exited our dwellings, like scubadivers leaving submarines, or astronauts departing from the protection of a spacecraft. We were confronted with transformed spaces. As we had physically distanced everything had effectively shrunk, we needed more space to do the same things. Where we could we began to encroach onto the street. This shock has drawn fresh focus on practices such as adaptive reuse and transformation. Students in the Interior Design studios at The Glasgow School of Art focus on both these tactics as sustainable ways to revive and revolutionise the way we use and view our city. This may be through detailed focus >

on compact specialist retail design and acknowledge both implicit and explicit context while folding-in the changing nature of shopping itself. These students express their imaginative concerns and obsessions in other ways too, including through emergent typologies such as inter-generational living or critical co-working, and all within existing building fabric, including substantial, and awkward, heritage buildings, preserving, and augmenting genius loci and reprioritising uses of space. The city’s streets are dissected, the logic of their formation exposed, and inventories are created. Suggested alternative occupancy is defined, ranging in tenor from polite interventions to radical remodelling, the emphasis is on interiority.

These approaches, working with what is there and sensitively retuning, are not new, but have become increasingly urgent. From Lacaton and Vassals ‘never demolish’ provocation to ‘The Dutch Atlas of Vacancy’ (RAAAF, 2014) – an inventory of circa ten thousand publicly owned, unoccupied buildings in the Netherlands – the latent capacity of empty/at-risk buildings is made obvious. The sheer amount of wasted built resource, and embodied energy, hiding in plain sight has reached crisis level. A quite different record of superabundance and its impact can be found in Laura Oldfield Ford’s ‘Savage Messiah’ (originally produced in 2005). Its collaged representations of a particular and complex urban reality find an echo in ‘Reactivate Athens’ (2017), itself an assemblage of critical design proposals for that city, as a means of offsetting some of the shock waves generated by the 2008 economic crisis. Where there are gaps a form of solid collaging such as that found in ‘168 Upper Street’ (Groupwork, 2019) may be an appropriate strategy. This building takes digitally facilitated layering and playful fragmentation to new levels allowing its interior to express itself, unburdened by its envelope.

Glasgow’s ‘City Centre Living Strategy’ targets a doubling of the city centre’s population by 2035 (from 20–40k). As well as places to shop these additional people will need a greater blend of high-quality places to live, work, relax and heal, additional public and green space, community clinics, spaces for experimentation. In city centre locations this is currently a challenge. There are simultaneously too many shops and not enough, too many square metres devoted to consumption and too few devoted to creation. We were bored in the city. We can no longer afford to be.

FLEXIBILITY, WELLNESS AND SUSTAINABILITY ARE THE WATCH WORDS ON EVERYBODY’S LIPS BUT WHAT DO THESE OFTEN NEBULOUS TERMS MEAN WHEN TRANSLATED TO THE LANGUAGE OF INTERIOR DESIGN? WE SPEAK TO THOSE DELIVERING THESE ASPIRATIONS TO ESTABLISH WHAT THEY REALLY MEAN.

Anna Lee Senior Interior Designer HLM Architects

How is the demand for adaptable and flexible spaces impacting your work?

The demand for ‘flexibility’ is huge, the hybrid work landscape will continue to evolve as we’re all re-establishing how we want to work, how teams meet and how the organisation intents to foster their internal culture. However, understanding the degree of ‘flexibility’ is paramount, it is not about making everything ‘flexible’. It is important to work closely with the client to identify the key functions of work that need to be supported and matching it with the right category of spaces.

This way, users can comfortably make adjustments within these zones, whilst there are still design cues to help inform the designed functions and behaviours, as well as the mechanisms in place to manage it. When teams are allowed to solve for themselves what is best for their work patterns, it can be very empowering.

How do we design our environment around wellness?

Given the collective experiences of the last 2 years, designing around wellness, wholistically, is more important now than ever. Beyond providing comfortable environments with good air, light, and acoustic quality that considers our physical wellbeing, it is critical that

>

workspaces also do more to improve our mental wellbeing, reduce stress and provide psychological safety. Things we can do to include space planning strategies to manage the level of energy/activity on a floorplate; fit for purpose spaces to suit different styles of collaboration; good wayfinding and technology tools to reduce user frustration; employing biophilic principles to appeal to our senses, connect us to a more natural state; social spaces to develop sense of community and belonging; providing dedicated areas for respite and reflection. Finally, the quality of spaces that help us live out our hybrid lives – personal spaces such as mothering rooms, prayer rooms, space to take a personal phone call, can make a big difference to employee’s overall wellbeing.

By combining innovative sustainable design with the practicalities of achieving statutory compliance and accreditation, we can generate long term environmental and commercial value for our clients. By adopted the targets and approach set out by the RIBA in their 2030 Sustainable Outcomes Guide, we are determined to guide and influence our clients. We have set ourselves a bold and ambitious goal that all projects designed in our studios will be capable of meeting these targets by 2025. Our aim is simple, to deliver the highest performing buildings which have a positive impact on the lives of those who use them and a positive impact on the world for future generations.

Amy Wootton Architect 56three Architects

The hybrid model of working has challenged our understanding of how a workspace should look and function. The pandemic presented a unique opportunity for our own office to undergo a conflict-free refurbishment. M&E requirements became a fundamental consideration, largely to facilitate hot desking, and creating additional breakout spaces for use during video call meetings, lunch breaks etc. became a priority. More homely features have also been incorporated, such as coffee tables, lounge chairs and decorative planting. This desire to create adaptable, comfortable, and ultimately less commercial workspaces, is a trend we are starting to see externally too, which is exciting.

Inevitably, we have seen increased demand from clients wanting spaces that adapt to users – particularly in commercial settings. There is also an increased appetite for conversion and interior fit-out projects, partially due to behavioural changes (large office / retail spaces becoming redundant), and partially because of the financial risk that >

large, new build projects can present. We embrace these projects, as they can offer clients a faster return for less investment, whilst allowing us to flex our interior design skillset. We are passionate about adapting buildings that have become ineffective – creating beautiful, commercially viable and functional spaces as a result.

How do we design our environment around wellness?

Again, this comes back to the idea of creating interiors that work harmoniously with occupants. As a practice offering both Architectural and Interior Design services, we are able to suggest building modifications that ensure adequate space is provided for features such as amenity and natural lighting, whilst minimising and carefully integrating M&E services into environments in the least impactful way possible. We believe that the concept of biophilia is also fundamental to creating healthy spaces, and wherever possible look to include planting in our interior projects. Combined with natural light and ventilation, stress levels can be reduced and performance enhanced.

Kenny Fraser Director Michael Laird ArchitectsWhat project best encapsulates your practice approach?

We would suggest that Brodies LLP’s new Edinburgh home on the top floors of Capital Square in Edinburgh best encapsulates our approach and, in some way, reflects our own values – Considerate, Innovative, Passionate.

Considerate - This project was four years in the making with an excellent client team who were willing to explore the past and learn from previous office designs and how they operated. They took the time to ask their team and learn.

Innovative - Brodies knew that their old (cellular) Edinburgh office restricted their working practices and how they interacted with each other. They were willing to be innovative in exploring new collaborative working practices and to create a space that is intentionally less corporate and reflective of their brand and team culture.

Passionate – There is a clear passion as the team embrace the limitless opportunities in their new home. Within the first few weeks of occupation, we are witnessing a real excitement from the Brodies team as they experiment with each new worksetting and explore every nook and cranny of the new office.

The workplace has been evolving for years and, whilst the pandemic certainly disrupted….well…..E V E R Y T H I N G, it could be argued that it just really accelerated what was

already underway in workplace design….particularly in the technology solutions world.

Now that the ‘dust’ is (hopefully) settling on this pandemic, it is clear that, whilst the ‘virtual’ will always have its place in our workplace, it’s the ‘physical’ and ‘real’ that reminds us what it is to be human and part of a team and is fundamental to our own health and wellbeing.

The move towards more agile worksetting choices has been evolving for some time now. With the quantum leap in comms technology over the last two years, many organisations are now realising that they can really experiment with their teams as to how they will work together in the future.

Change and flexibility is therefore inevitable and very exciting. It brings new challenges and introduces new hybrid concepts of the workplace which blur the boundaries between hospitality, office and home environments.

As interior designers we are finding the furniture supplier industry is playing more of an important design role in this area. This relationship works both ways, is very rewarding and helps balance all of the ergonomics, acoustics, adaptability, costs and ’day two’ service considerations on each project.

The WFH experience has opened people’s eyes to the ways that technology can support us in our work, and where work is done. Businesses are really being challenged to create engaging work environments that draw-in remote workers, and new talent.

Future workplaces will need to evolve from a static form to a more ‘connecting’ experience. The office is becoming a ‘town square-like’ hub energised by the buzz of occupants coming together to connect, collaborate, focus, or simply socialise. Those ‘hub’ spaces will take on a new form with many elements borrowed from home-life and hospitality experiences, bringing welcome comfort and familiarity.

As our world faces resource scarcities and ecological crises, a concern for the adaptability of buildings and the spaces within, is especially relevant. Adaptability allows current and future functions to be fulfilled more efficiently

thus spaces remain longer in service. Interior spaces that can respond to change faster and at lower cost guarantee viability for longer.

That agility (flexibility) will shift traditional thinking. Of course, space’s ability to be rearranged easily as and when necessary, relies on clarity of project vision – A notable example for Keppie being our work on the NHS Louisa Jordan, step-down facility – a fully operational 1000+ bed hospital, conceived and delivered within the existing SEC buildings in only 23 days.

We believe that interior environments should develop with people’s wellness central to the design vision. Businesses whose operations and behaviours focus on health and wellness in a holistic way, attract and retain happy workers and benefit from multi-layered cultural gains.

The embrace of the ‘WELL’ standard sets a performancebased measure, certification, and monitoring framework. As designers, we believe it our duty to encourage healthy habits that support physical and mental wellbeing. One positive post Covid 19 is the elevation of such issues, with employers, developers and operators looking much harder at worker amenities and how these with their business culture function to protect and promote well-being.

We love a complicated project and our flexible workspace project, ‘Clockwise’ at Commercial Quay is no exception! With almost 30,000 sq ft of former warehouse space to be refurbished, it was not only the complex internal architecture but also the program brief that was complex. A complement of different workspaces was required including meeting rooms, on-site café, independent craft brewery bar and extensive break-out. Modifications over the years had resulted in a mix of contrasting structures, ceiling heights and floor levels across all buildings, making this a challenging project to complete, especially with existing tenants in occupation throughout the build. The de-furbished aesthetic, cool break out, café and bar provide a popular addition to Leith.

Flexibility for the workforce has been brought to the fore as we transition out of working from home. Occupiers

are looking for different types of space, after the privacy of home working - enter the phone booth and the zoom room! Technology is making most things possible and along with online meeting platforms and advances in internal fittings and fixtures, a touch free world is becoming more achievable. Sustainable interiors should still be the focus and companies producing interior finishes are developing some interesting products with carbon negative being the goal, rather than just carbon neutral.

Sustainability is a fundamental driver for Morgan Architects’ design output. We continue to champion the sensitive and intelligent reuse of existing buildings. This, combined with innovative building systems and a sustainable approach to material specification, has meant each design has sustainability at its core. For each of our interior projects, we utilise every opportunity to re-use and re-purpose existing building fabric and fit-out materials, and take a ‘fabric-first’ approach to future-proofing the buildings we design and refurbish. Our focus is on creating timeless, resilient and sustainable interiors, that also provide delight for their users.

Client: Empiric Student Property / Hello Student

Borough High Street was an office refurbishment project, on which we were engaged to provide Architectural and Interior Design services. On initial consultation, we were asked to re-imagine the spaces available, creating zones - each providing unique functions. Although the space available was largely open plan, we aspired to create distinctive office, dining, breakout, and meeting zones, each expressed by their own aesthetic, and all with a comfortable and homely feel.

By enhancing original features, such as exposed brick walls, we celebrated the buildings heritage, whilst praying out cable trays to a heritage gold, and specifying vast amounts of planting, gave the space a luxurious, fresh and choreographed feel. Multi-functional furniture punctuates the floor plan, facilitating everything from large, formal meetings to small, casual catch ups.

As well as advising on interiors, we co-ordinated M&E, and suggested how best to adapt existing services to compliment the intended aesthetic. When managing internal partition alterations, we created open, light filled spaces –largely through the extensive use of reeded glazing. We understand that client feels that this refurbishment has been very successful, and that the resulting space offers a broad variety of flexible spaces, within an attractive setting.

14 Alva Street

Edinburgh EH24QG

Tel: 0131 220 3003

Email: info@56three.com

Web: www.56three.com

56three is a design based Architectural and Interior Design Practice with projects covering new build, conservation and refurbishment works throughout the UK. We have an award winning team of architects, technicians and interior designers who are able to provide the full range of architectural services from feasibility through to construction. We work in a collaborative way with relevant stakeholders and planning authorities to embed sustainable solutions providing optimum land and building values, and to deliver the potential for long-lasting and enjoyable places in which to live, work and play.

Glasgow

G2 2SD

Tel: 0141 226 8320

Email: glasgow@hlmarchitects.com

Web: www.hlmarchitects.com

Twitter: @HLMArchitects

Thoughtful design to make better places for people.

We listen and respond to the ambitions of our clients and understand the needs of the people who will use the places and spaces we create. We strive to create places of education that inspire, healthcare environments that nurture, homes that are part of thriving communities, and infrastructure that is sustainable in every sense: environmentally, economically and socially. Our sector-led approach and dedication to retaining our deep rooted regional connections, coupled with a thoughtful approach to design, enables us to differentiate from our peers.

Services:

Architecture

Interior Architecture

Landscape Architecture

Masterplanning

Environmental Sustainability.

James Smith McCune Learning Hub

Client: University of Glasgow

The new learning and teaching hub, which forms the initial phase of this expansion programme, will create a signature gateway building at the heart of the expanded Campus based on active learning pedagogies. The University is undertaking an ambitious expansion programme to further enhance its global standing and provide a positive impact on the community it serves. The design has been inspired and driven by user consultation at every level, emphasising the student experience to provide an environment that is open and accessible for all. Its mixture of lecture theatres, small group rooms, breakout and study areas reflects a growing trend in making faculty areas more bespoke, and focussing general teaching in a shared learning hub that embraces new teaching pedagogies and optimises space utilisation. To fully understand the user aspirations, HLM visited exemplar schemes in Australia with the University, and then trialled new learning pedagogies in a series of pilot rooms in an adjacent building. This has enabled HLM to work with academics to test new approaches such as flipped classrooms and TEAL spaces and define the FF&E and IT needed to support this. The resultant scheme, which opened its doors in April 2021, improves cohesiveness and connectivity across the campus in a building that showcases formal and informal learning and teaching through a welcoming, open environment and encourages students to linger – a sticky campus.

Client: NHS Lanarkshire

The relationship of interior spaces to human experience is an acknowledged central consideration - the important ‘experiential’ factor – equal, if not more important in a future looking hospital. The developing interior design at New Monklands University Hospital places staff, patients, and visitors central to all considerations.

The design establishes a bespoke interior identity inspired by ‘the village’ metaphor, set within the undulating woodland character of the selected Wester Moffat site. An identity symbolic of the diverse local cultures and gathered spaces that flex allowing different functional activities to fuse together. Streets, squares, and gardens are composed to bring diversity of space, green outlook, and personality.

Early in the planning over-arching ‘rules’ set a clarity to orientation and wayfinding. This places staff spaces centrally reducing journey times and affording easy access to external spaces for respite. Throughout the ‘hospital village’ interior spaces embrace opportunities to connect with the outdoors. Campus-wide digital technologies are the baseline, and the design has grabbed the expansive potential digital mediums offer for animating interior spaces - we love the idea of spaces changing; never the same twice, and users able to influence their direct environment?

G2 4RL

Email: info@keppiedesign.co.uk

Web: www.keppiedesign.co.uk

Twitter: @Keppie_Design

We take pride in being extremely easy people to work with and are of course a trusted partner on private and public sector projects. We’re regularly collaborating with exciting people within the biggest names in construction, engineering, architecture, and design across the globe. From Arts & Culture to Healthcare, from Education to Sport, from Finance to Retail - we have a fully exportable skill set that makes a real difference wherever we work. Our global agility allows us to alead and collaborate on a fantastically diverse and inspiring portfolio.

Services: Architecture

Interior Design Planning

5 Forres Street, Edinburgh EH3 6DE

Tel: 0131 226 6991

Email: edinburgh@michaellaird.co.uk

83a Candleriggs, Glasgow G1 1LF

Tel: 0141 255 0222

Email: glasgow@michaellaird.co.uk

Web: michaellaird.co.uk

Twitter: @MLA_Ltd

Instagram: michaellairdarchitects

LinkedIn: Michael Laird Architects

At MLA we believe the interaction of people and place has the potential to transform the way we live and work. By working with our clients collaboratively we create spaces that proudly stand the test of time.

Services:

Architectural Design

Interior & Workplace Design

Strategic Consultancy

CDM Consultancy

New

Client: Brodies, Capital Square, Edinburgh

Scottish Law firm Brodies decided to move from their traditional home at Atholl Crescent in the City’s West End to new, bespoke premises in the top three floors of Capital Square.

MLA were appointed to provide workplace strategy and interior design services to create a flexible, agile workplace that also maximised the amazing views over Edinburgh.

Following a full consultation process with the client, our fit-out provides a rich and tactile workplace environment that is smart, welcoming, brand consistent, and supportive of agile, flexible working.

Workspace is supported by meeting, training & conference rooms, breakout hubs and a café, whilst a bespoke internal stair provides a central focus point that also promotes connectivity between departments.

5 Advocate’s Close

Edinburgh

EH1 1ND

Tel: 0131 332 4200

Email: lisa@morganarchitects.co.uk

Web: www.morganarchitects.co.uk

Twitter: @MorganArchitects

Instagram: @morganarchitects

Linkedin: @Morgan Architects Ltd

Morgan Architects is an Architecture and Interior Design Practice based in Edinburgh and working throughout the UK. Established in 1995, the practice has recently rebranded and is headed by Guy Morgan and Lisa Morgan. We are recognized as the ‘go to’ Architects for solving building designs in challenging sites; where listed buildings require reworking to ensure their future viability, where planning for new build is sensitive and requires strong relationships with both council and stakeholders, where our passion and hard work leads to us designing buildings and interiors that are rational, interesting and the best they can possibly be.

Our brief was to design the first serviced offices in Edinburgh for ‘Clockwise’, the developer’s flexible office operator. The Category ‘A’ listed buildings were originally built as bonded warehouses to store claret, bootlegged via the Baltic states during the Napoleonic wars, and latterly to store whisky until the 1980s. The buildings had to work hard, to support a diverse mix of accommodation notably; hot desking, dedicated desks, and 2 – 12-person private offices whilst also providing exemplary break out-spaces. These included a café, tea preps, both casual and bookable meeting spaces and a variety of touch down points throughout the buildings for casual working and dining. We also converted the impressive brick vaulted space in No. 80, previously a gunpowder store, to an on-site craft brewery bar for a local brewer providing a fantastic additional on-site benefit for tenants and locals alike. Inspired by the stories of the building’s past, we strove to design meaningful interiors with a characterful richness, using natural materials influenced by the rich golden and ruby red hues of the whisky and claret stored here in the past. One of the challenges was delivering this, circa 30,000 sq ft of refurbished office space whilst working around existing tenants.

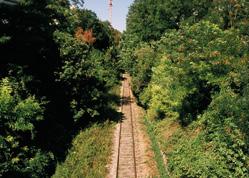

DISUSED URBAN RAILWAYS HAVE LONG BEEN OBVIOUS CANDIDATES FOR BIKE PATHS BUT A NEW GENERATION OF PROJECTS INSPIRED BY THE SUCCESS OF THE HIGH LINE IN MANHATTAN ARE TAKING THE IDEA UP A LEVEL BY INCORPORATING URBAN FARMS AND LINEAR PARKS. LEADING THE WAY IS THE CITY OF PARIS WITH LA PETITE CEINTURE, A CIRCULAR RAILWAY THAT IS BEING BROUGHT BACK TO LIFE AS THE WORLD’S LONGEST URBAN PARK. MARK CHALMERS PUTS US IN THE LOOP.

It turns out that 2018 was a good time to visit Paris. Covid wasn’t even a gleam in an epidemiologist’s eye and the gilets jaunes hadn’t got into their stride – but it was the 50th anniversary of the événements of May 1968, protests which for a brief moment promised to upend French society.

In July 2018, the Île-de-France was also in the grip of a canicule and temperatures reached the high thirties. I stayed at Louveciennes, a five minute walk from the point where Sisley painted the Seine, and explored the city using the RER system of suburban railways. Later, as the day’s heat dissipated, I wandered along the riverbank to sit under the trees beside the Machine de Marly.

There are over 20,000 Parisians per square kilometre. Paris is twice as dense as New York and five times denser than Berlin or Edinburgh. Europe’s population has grown inexorably, yet city density tended to decrease during the 19th and 20th centuries once railways, trams and finally private cars enabled people to commute from the outskirts. That marked the birth of urban sprawl.

Paris is an exception. Its continued density makes places like Louveciennes precious and the railway network vital. The city’s transport system and green spaces come together and clash where a railway known as La Petite Ceinture, or Little Belt, encircles the city centre. Today its abandoned tracks run along a backdrop of graffiti, construction sites and industrial wastelands.

La Petite Ceinture stretched for 35 kilometres and was built in time for the 1867 World’s Fair. It soon carried 750,000 tons of freight each year, but as Paris expanded, lines radiating from the great railway termini grew busier while traffic on the circumferential Petite Ceinture fell away.

The line switched to passengers instead, and by the turn of the 20th century its trains circled the city several times an hour. The development of new Métro lines put paid to that second life: the Petite Ceinture stopped carrying passengers in 1934, and by 1969 it was hors service. Since then much of it has lain unused and overgrown.

At exactly that moment, a movement emerged from the hype and slogans of May ‘68. The Situationist International promised a revolution of everyday life: the last great, imaginative attempt to find an alternative to consumer capitalism. The Situationists recognised we were in thrall to the spectacle of mass media, and tried to convince us to stop living vicariously through TV celebrities and films from Hollywood. While they failed to make a breakthrough in 1968, their ideas outlived them.

Guy Debord, their leader and prophet, was drawn to the remnant spaces of Paris. He and his comrades invented the dérive as an antidote to the commercialisation of the city. A dérive could involve breaking into a derelict building, exploring an abandoned hospital or wandering through Père Lachaise cemetery. So off they went down back streets and through

deserted parks, clambering over walls to see what they could discover.

To Debord, “The lessons drawn from dérives enables us to draft the first surveys of the psycho-geographical articulations of the modern city”. He even had a go at re-drawing the city plan. His Naked City map of 1955 was published in the Psychogeographic Guide to Paris, identifying locations which could be explored with a particular frame of mind intended to draw out their ambience.

Most of the remnant spaces which Debord sought out are long gone, built over and developed for profit, like the old slaughterhouses at Parc de la Vilette or the Renault factory at Île Seguin, but stretches of La Petite Ceinture remain as an overgrown wasteland running through, above and below the city.

Inspired by the Situationists, I walked along a back street in the 15th arrondissement until I found a gap in the fence with a glint of railway track far below. I squeezed through, then skidded on my backside down a sheer slope which I knew I’d struggle to climb back up – but I knew there was bound to be an easier way to escape. There always is.

This was one of the long-abandoned sections of the Petite Ceinture. After 1969, much was retained as a railway – firstly for the movement of rolling stock, and later held in reserve

by SNCF, the state-owned railway company. Ten years later, stretches were incorporated into the construction of the ‘C’ line of the RER (Réseau Express Régional), the regional rapid transit system which serves Paris.

Today around 23 kilometres remains unused, extending clockwise from Batignolles in the 17th arrondissement to the banks of the Seine in the 15th. In theory it’s possible to walk along its entire length; in practice that’s tricky thanks to fencedoff tunnels and crossings with live railway lines. For the past fifty years, Paris has been figuring out how to use this unique landbank.

Until recently, La Petite Ceinture was the domain of underground explorers or cataphiles and the graffiti writers who haunt the Métro system. The catacombs run for kilometres through the limestone underbelly of Paris, and one access is a discreet manhole just inside the darkness of a portal to one of La Petite Ceinture’s tunnels.

Gradually the abandoned railway was encroached on by the city. In 2008, a stretch between the Porte d’Auteuil and the Gare de Passy-la-Muette became a sentier nature or nature trail but the mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, had far greater ambitions. She plans to turn the French capital into La Ville Du Quart D’Heure, which sounds much more attractive than a “Twenty-Minute City”. Thanks to Paris’s density, it’s relatively

easy to ensure that you’re no more than a 15 minute walk from the shops, school and station.

Hidalgo planned to turn parts of the Petite Ceinture in the 16th arrondissement into a green path, and had ambitions to turn an elevated track in the 15th into a High Line-style promenade. The High Line is an imaginative linear park which re-uses an abandoned elevated railway in Lower Manhattan: it was brought back to life by architects Diller Scofidio + Renfro with landscape designer Piet Oudolf.

But around the same time as I walked along the Petite Ceinture’s tracks, Anne Hidalgo was locked in a political battle royal over the line’s future. The trackbed and adjacent land are still owned by SNCF, which proposed a joint venture with the Municipality of Paris to develop twenty stations, platforms and tunnels into bars, restaurants and cultural venues, along with green spaces and more footpaths.

This process is often called gentrification, and I was fascinated to see how it works in France, since gentrification has become a term of abuse in the UK. It translates as middle class people moving into an area and driving up property values so that its traditional inhabitants are priced out. Coffee bars, expensive apartments and cycle paths are some of its outriders.

It’s clear that Parisians have reservations about gentrification, too. Firstly, Hidalgo’s proposal drew the wrath of environmentalists and Communist politicians, who saw it as property speculation on the sly. Soon the political centrists joined them, denouncing “an outrageous concretisation and commercialisation”. So the spirit of Guy Debord lives on in Paris.

The mayor was forced to retrace her steps, unheard of for someone who built her career on tactical urbanism, imposing changes which were claimed to be “temporary” but end up being permanent. Those include the pop-up bike lanes which other cities have copied, and proposals to remove half of Paris’s car parking spaces. Hidalgo has become one of France’s most divisive politicians.

So why are Parisians fighting for an abandoned railway line? Its length, 23 kilometres, makes it the longest urban park in the world. It’s already successful as a green lung, with urban farms which function like allotments, sculpture parks hidden in cuttings, guerrilla gardens tucked away in sidings, nature trails along viaducts and recreation areas for the adjacent HLM flats.

HLM translates as housing at moderate rent, and that cuts to the heart of the issue. As soon as she aligned herself with property developers, Hidalgo was viewed by left-wingers as

having sold out her socialist principles. But she also took aim at pollution and congestion by using the bike as a weapon in the “War against the Car”. That inflamed right-wingers, too.

The so-called war against the car takes on a new sense in Paris. When I stopped at a Park & Ride near Aulnay-sousBois, all the Peugeots, Citroëns and Renaults were dented and scratched, as if they’d been involved in urban combat. But banning the car is only half the equation: it doesn’t solve the problem of shifting hundreds of thousands of Parisians during rush hour.

Some, like the Association Sauvegarde Petite Ceinture (ASPCRF), would like to see the railway brought back into use as a railway. While the line fell out of use decades ago, demand is steadily increasing. A new tram route shadows the Petite Ceinture for several kilometres, serving the same areas and often within sight of the old railway. The first lesson from Paris is that plans to convert urban railways into bike paths are counter-productive when they could become railways again.

Another aspect is the idea that green spaces have a much greater value to people who live nearby, than for commuters who pass through en route to somewhere else, or for nighttime economy entrepreneurs who could open venues anywhere else in the city. With undeveloped land being so

scarce, can Paris afford to give up its biodiversity for bars and restaurants?

Regardless, Paris is years ahead of Scotland in the re-use of railway corridors. Miles of trackbed lie under-used or simply abandoned, such as the old Glasgow Central Line through Kelvinbridge tunnel and Botanic Gardens station which has been sealed off with spiky fences. In Edinburgh, the old tracks from Murrayfield to Granton and Newhaven, which might one day become Line 2 of the tram system, are currently an underutilised bike path.

The North Deeside Line in Aberdeen is similar, an interrupted path which runs from Duthie Park through Cults, Bieldside and Milltimber, has less chance of becoming an active railway again. Finally the old Dundee-Newtyle Line is walkable in Lochee, but disappears under a retail park to re-emerge beyond the edge of the city at Auchterhouse. All four cities fail to recognise the potential of their dormant railways.

Meantime in Paris, you can still witness the Situationist Manifesto in action. Just as Guy Debord cautioned in the 1960’s, go out and explore – especially leftover places like the Petite Ceinture – otherwise politicians will hand them to special interests and big business, and soon you’ll be reduced from a citizen to a mere consumer.

PAISLEY IS WASTING NO TIME POST LOCKDOWN IN PRESSING AHEAD WITH A TOWN CENTRE STRATEGY THAT LOOKS TO THE FUTURE BY BUILDING ON THE PAST. URBAN REALM INVESTIGATES HOW THE LARGEST TOWN IN SCOTLAND IS SQUARING UP TO GLASGOW BY BRINGING OUT ITS ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL BIG GUNS IN RESPONSE TO A HOLLOWED OUT RETAIL CORE.

The much-heralded migration from office to country is opening up new opportunities for small towns to claw back a living from their larger neighbours but what more should our secondary urban centres do to stave off online retail, a brain drain to the cities and shifting work patterns?

Against an inauspicious international backdrop, Paisley is betting on a better tomorrow with Future Paisley, a broad programme of events, activities and investment designed to signal to locals and the wider world that a period of enforced hibernation is now at an end. The Renfrewshire town is one of the first out of the starting gates in responding to the new world order, building on pre-pandemic initiatives such as Paisley 2030 to show that it is back in business as a cultural heavyweight that punches above its population weight.

Current initiatives trace their origins back to The Untold Story, a 2014 bid by Renfrewshire Council to position the town as a bastion of heritage and culture and which acquired real momentum after being shortlisted for UK City of Culture in 2021 and with its green lighting plans for a starchitect museum makeover.

Set against the backdrop of a global pandemic this is

no mean feat, but external forces have undoubtedly taken some of the wind out of these sails, prompting the council to set them billowing again as Alasdair Morrison, Head of Economy and Development at Renfrewshire Council told Urban Realm: “In terms of investment, the world has stood still over the past two years. Lots of things have been delayed simply because of the uncertainty.”