11 minute read

Philanthropy

Dedicated to Science and the Arts:

James V. Aquavella, MD

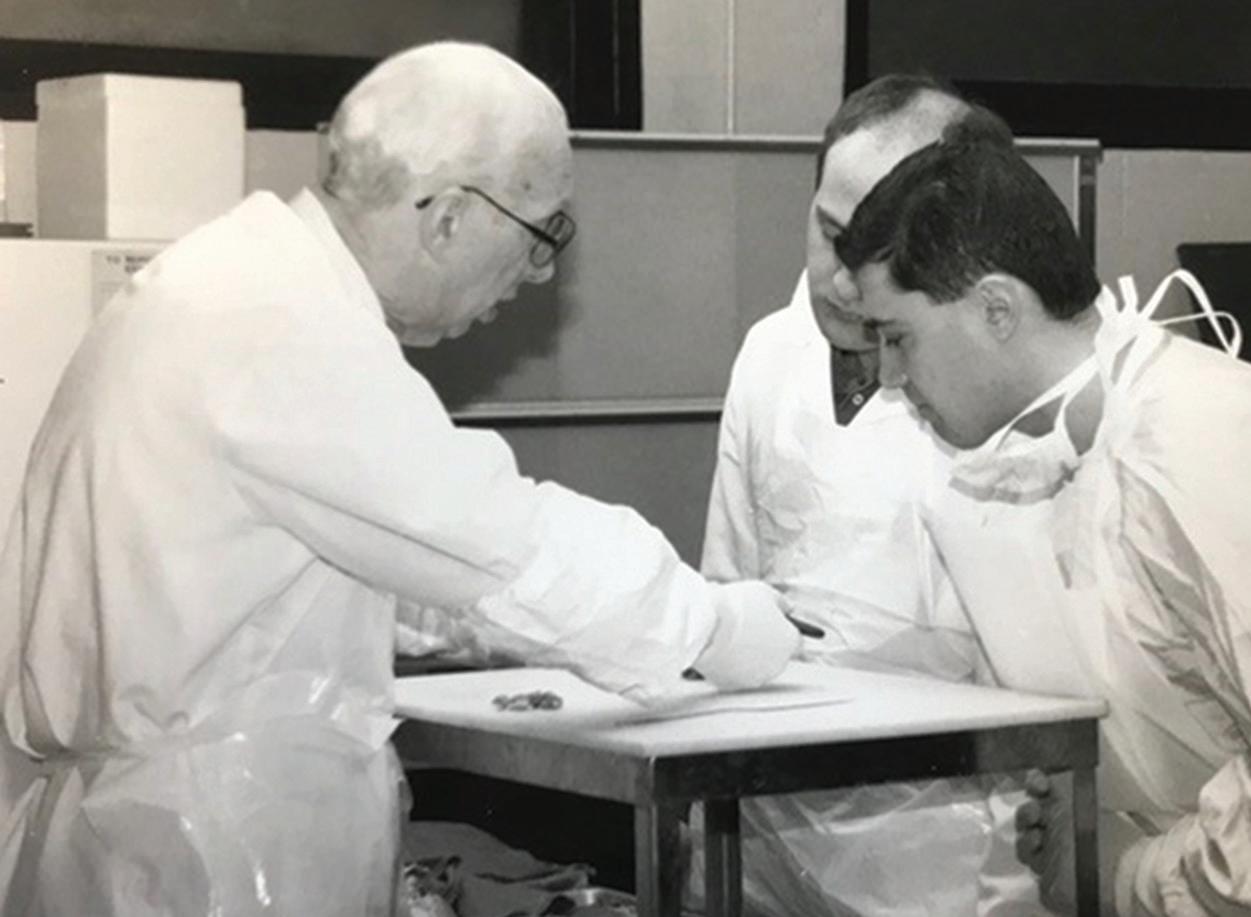

For more than 60 years, James V. Aquavella, MD—a corneal surgeon and the Catherine E. Aquavella Distinguished Professor of Ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Flaum Eye Institute—has been a leader in clinical practice, surgery, education, and research. He is known worldwide for his work with artificial corneal implants for infants and children, which have restored sight to patients as young as a few weeks old.

Over the course of his distinguished career, Aquavella has conducted seminal research; taught and mentored countless medical students and corneal surgeons; given lectures around the world; authored textbooks and published more than 350 papers; and helped and healed many patients and their families.

Aquavella is also a a champion of the humanities, an avid art collector, and a former member of the Board of Managers at the Memorial Art Gallery (MAG). With a strong wish to share his passion for art with the Rochester community, he recently donated

James V. Aquavella, MD

12 paintings from 17th and 18th century Europe and America to the MAG. He and his late wife, Kay—a nurse, educator, and hospital administrator—have gifted a total of 15 works of art to the museum from their private collection.

“Looking back over history, the greatest scientists—from people like Galileo to DaVinci to Isaac Newton—were all devoted to the advancement of their fields as well as to art, music, and the humanities overall,” says Aquavella. “The humanities provide a foundation to better understand the human experience, along with the richness and beauty of it.”

An Accomplished Career

Aquavella was the first fellowship-trained corneal surgeon in the U.S. when he established his practice in Rochester in the mid-1960s, specializing in cornea and external eye disease. Having been recruited by the then-chair of the Ophthalmology Department, John Gipner, MD, Aquavella joined the University in 1962. He has been affiliated with its Flaum Eye Institute for many years and continues to treat patients there.

“Dr. Aquavella has dedicated his life to his patients and to improving their health and quality of life,” says Mark Taubman, MD, dean and CEO, University of Rochester Medical Center. “He’s an exemplary clinician, teacher, scholar, and human being who is committed to making this institution and our community a better place. We both share these convictions, along with our deep appreciation for the arts and opera.” Aquavella received his AB from Johns Hopkins University and his medical degree from the University of Naples in Italy. Upon his return to the U.S., Aquavella became a member of the health teams at the Kings County Medical Center, Brooklyn Eye and Ear Hospital, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Harvard University, and the Schepens Institute in Boston. Later in his career, he became founder and president of the Cornea Society, president of the Contact Lens Association of Ophthalmology, director of the Eye Bank Association of America, and consultant to the Food and Drug Administration and Tissue Banks International.

A Strong Partnership

James and Kay Aquavella were married for 40 years, until her death in 2012. They traveled the world together, often while he participated in conferences and gave lectures. They also nurtured their shared interest in the arts and frequented places such as the Frick Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Metropolitan Opera in New York City; and the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

“Kay was a kind, dedicated woman,” says Aquavella. “She always felt strongly about my commitment to teaching and research and was in favor of supporting the University, both at the Medical Center and at the Memorial Art Gallery, which she very much enjoyed. She was also the driving force in our collaboration to create the first ambulatory surgical center in New York State. The ambulatory procedure is now used for 70 percent of all surgery performed in the United States.”

A Legacy of Giving

In addition to his gifts to the Memorial Art Gallery, Aquavella, established, in 2013, two endowed professorships at the University’s School of Medicine and Dentistry: the Catherine E. Aquavella Distinguished Professorship in Ophthalmology, in honor of his wife, and the James V. Aquavella, M.D., Professorship in Ophthalmology. These gifts ensure that excellence in ophthalmological research, teaching, and scholarship at the University will continue in perpetuity.

Read the full story at uofr.us/Aquavella.

This retired cardiothoracic surgeon and academic medical leader established an endowed scholarship to benefit future generations of medical students.

Stephen Plume (MD ’69, Res ’75)— Emeritus Professor of Surgery, Community and Family Medicine, and The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth College—has spent his career working in academic medical centers as a cardiothoracic surgeon, a faculty member, and an administrative leader. Plume recently established an endowed scholarship at the University of Rochester’s School of Medicine and Dentistry (SMD): the Stephen K. Plume, III ’69M (MD), ’75M (Res) Scholarship.” “I’m very appreciative of what I learned at Rochester,” says Plume, who has spent most of his life in Vermont, just across the state line from Hanover, N.H. “The school and faculty members such as Dr. George Engel, who founded the biopsychosocial approach with Dr. John Romano, provided me with practical knowledge and insight that informed my entire career.”

Plume had a particular affinity for Engel, who was his professor and mentor. “This scholarship pays homage to what he meant to me,” he adds. “It’s a way for me to honor his influence and, at the same time, to support future generations of medical students.”

To make an immediate impact, Plume also established a current-use fund to have resources available to name a scholarship recipient for the 2021–22 academic year. Olanrewaju Akande, a first-year medical student, is the first Plume scholar. Recently, the two had the opportunity to meet over Zoom. “Olanrewaju is a motivated young man with a great future ahead of him,” he says. “He is deserving of a scholarship, and I am glad to support him.”

“Without Dr. Plume’s support, I truly do not envision myself sitting alongside my peers at the University of Rochester today,” says Akande. “Because of his generosity, I am here, at the School of Medicine and Dentistry—my top choice for medical school.”

Here, Plume elaborates on his time at the medical school and his reasons for giving back.

What was the catalyst for establishing this scholarship?

Although I’ve always supported the Medical School through its annual fund, I came away from my 50th reunion a few years ago with a wish to do something more for the institution. I reconnected with friends I hadn’t seen in decades, and I walked through spaces that held significant meaning for me. All of this rekindled feelings of loyalty and affection and prompted me to reflect on how important that time was in my life and career.

What do you wish for Olanrewaju and future Plume scholars?

My wish for all medical students is to find honorable and satisfying careers in medicine. In addition to the benefits of the rigorous academic program at SMD, I’m hopeful Olanrewaju and future beneficiaries of this scholarship become exposed to and take advantage of the hallmarks of a Rochester education.

How do you think the biopsychosocial model transformed clinical care?

For me, it comes down to this: illness is an individual experience that manifests differently in each one of us. It’s personal. We can learn about named diseases in textbooks, but we do not understand an illness until we connect with the person, in the context of that person’s life, goals, and distinct environment. This approach has carried over to other aspects of my life, influencing how I interact with colleagues, institutional leaders, family, and friends.

Advice for prospective medical students?

I do a lot of admissions interviewing for Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth. I advise prospective students not to over-intellectualize their decision. I encourage them to learn what they can about the schools they are considering, and then to ask themselves, “Will I like and trust the people I’ve met?” I remind them that the people shaping their values, whether explicitly or through what has been called “the hidden curriculum” of medical school, are at least as important as the subjects studied. Getting my medical education among those I trust and respect was one of the best decisions of my life.

Stephen Plume, MD

Do you have counsel for those who may be considering a gift to the school?

I encourage other alumni to reflect on what their medical school experience has meant to them over the course of their careers. Then, if they are thinking about making a gift, do what feels right to help nurture the traditional values and expertise that are synonymous with the school.

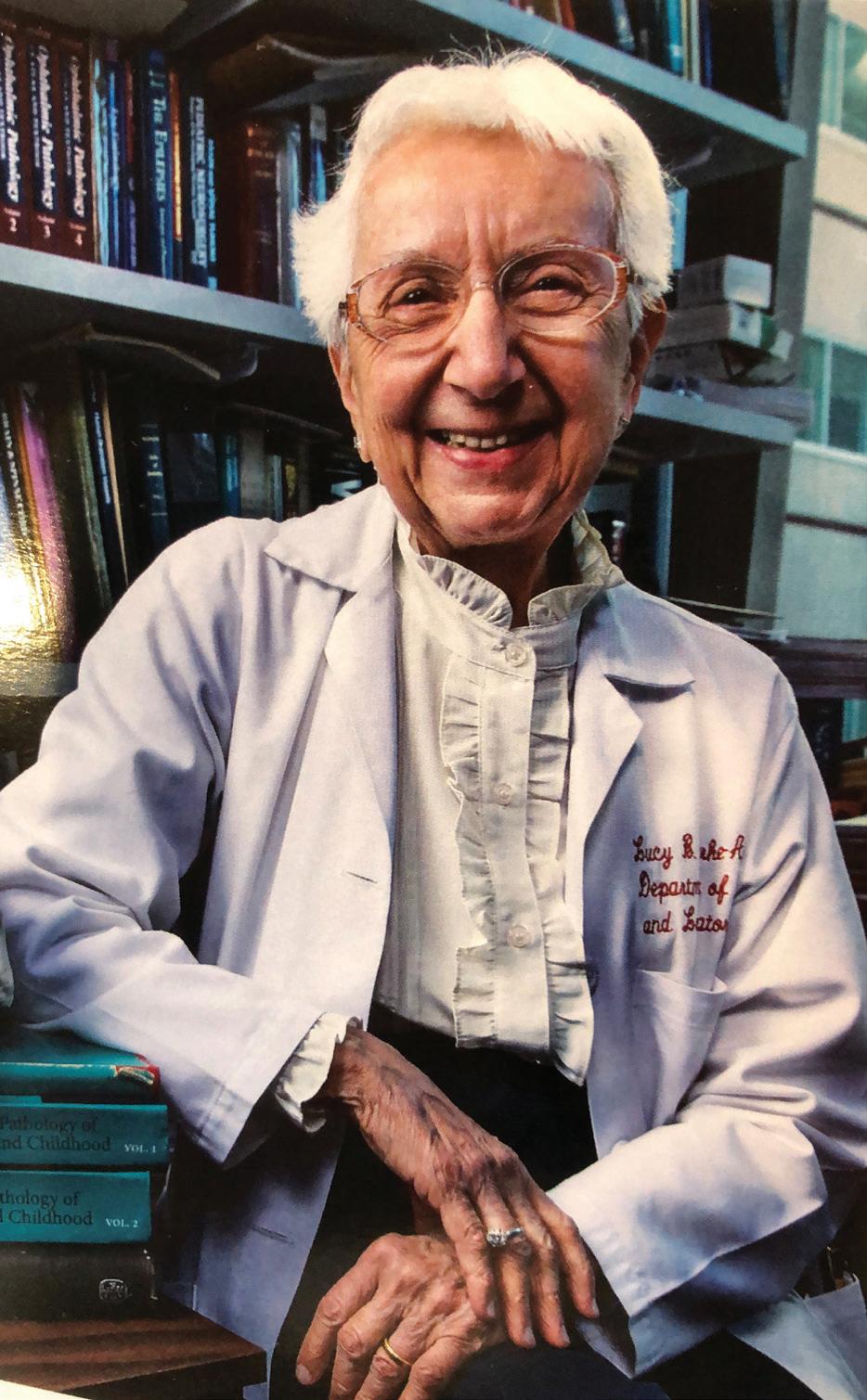

Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD: Trailblazer, Pediatric Neuropathologist, Would-Be Opera Singer

The Flaum Eye Institute is the recipient of a generous bequest from Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD, a longtime supporter of Alex Levin, MD, chief of pediatric ophthalmology at the Institute.

As a young girl and a child of Armenian immigrants, Rorke-Adams thought that someday she’d become an opera singer. But when she was a teenager, a missed audition with a Metropolitan Opera singer set her on a different course, leading her instead to an illustrious 58-year medical career as a pediatric neuropathologist.

Her career highlights include becoming the first woman president of the medical staff at Philadelphia General Hospital and later at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where she spent most of her career. She was also chair of the Department of Pathology at both institutions and acting CEO of Children’s for 18 months. She held long associations with the Philadelphia Medical Examiner’s Office, the Wistar Institute, and Wyeth Research Laboratories. She was also a professor of pathology, neurology, and pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine.

Later in life, Rorke-Adams even became one of the trusted keepers of Albert Einstein’s brain. Here, she provides insight into her life and career.

Career Catalysts

Starting at about age 4, I loved to collect earthworms, especially after a good rain. I’d take them apart to see what I could find. I think that was the beginning of my career as a pathologist. Then, when I was a teenager—right around the time of the canceled audition—I read The Magnificent Obsession by Lloyd Douglass. It’s the story of a feckless playboy who inadvertently causes the death of a famous neurosurgeon. He tries to make amends by studying medicine. I was inspired by the man’s drive to right his wrongs and to become a neurosurgeon.

Proudest Moment

Although I have many, here’s one: In my 1981 Presidential Address to the American Association of Neuropathologists, I challenged a world authority on his long-held theory about embryonal pediatric brain tumors. That gentleman was not pleased. But by challenging him, other colleagues realized that this was fertile ground for study. In consequence, there have been many advances in our understanding of this group of childhood tumors.

A Beautiful Brain

In 1955, Dr. Thomas Harvey, the pathologist at Princeton Hospital, performed an autopsy on Albert Einstein. Five sets of microscopic slides were then made at the pathology laboratory of Dr. William Ehrich at the University of Pennsylvania. Dr. Harvey and I were students of Dr. Ehrich, though he preceded me by some years. Dr. Harvey gave one set of slides to Dr. Ehrich and some years after his death, they were given to me. Dr. Einstein died when he was 76 years old, but his brain was that of a young person. After guarding them for many years, I decided that they belonged in a museum and gifted them to the Mutter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, where they are on display.

Reasons to Give

My parents instilled in me the importance of making my life count for something by sharing whatever talents I possessed with society at large. I tried to do that by focusing on advancing science in the hope of improving the lives of children. My late husband, C. Harry Knowles, was a brilliant scientist and physicist who held more than 400 patents and succeeded exceptionally in the company that he established. He shared a desire to invest in the next generation and chose to do this by establishing the Knowles Teacher Initiative. This initiative supports teachers by advancing their skills in teaching math and science to high school youths.

A Shared Commitment

Harry and I developed a deep friendship with Dr. Alex Levin and his wife, Faith. When we first learned of his pioneering work identifying and treating genetically induced diseases of the eyes, we decided to support him. At that time Dr. Levin was working at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. When he became chief of pediatric ophthalmology at the University of Rochester Medical Center’s Flaum Eye Institute, we redirected our support. My husband was a modest man with a profound altruistic outlook who pledged to continue supporting Dr. Levin’s important work. It now gives me great pleasure to carry out his wishes by formalizing a bequest at Flaum that will do just that.

Read the full story at uofr.us/Rorke-Adams.

Lucy Rorke-Adams, MD