79 minute read

Medical Center Rounds

Collaborative Research $10M NIH Grant to Support URMC Research on Rheumatoid, Psoriatic Arthritis

Jennifer Anolik, MD

Two URMC experts are leading research teams as part of a collaborative effort among the National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Food and Drug Administration, pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations to study the cellular and molecular interactions that lead to inflammation and autoimmune diseases.

Jennifer Anolik (PhD ’94, MD ’96, Res

’99, Flw ’01) professor and interim chief of Allergy, Immunology & Rheumatology, will serve as the principal lead for the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) team, and Christopher Ritchlin, MD (MPH ’08), professor of Allergy, Immunology & Rheumatology, will lead the psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis team.

The program adds URMC to the NIH Accelerating Medicines Partnership®: Autoimmune and Immune-Mediated Diseases (AMP AIM), a prestigious network of academic and clinical researchers. It’s supported by a $58.5 million grant that funds research across all institutions in the network for five years and is divided into four disease teams: rheumatoid arthritis (RA), lupus, psoriasis/psoriatic arthritis, and Sjogren’s disease, with multiple technical cores.

Anolik served as the RA lead and co-chair of the network on an earlier grant—the AMP RA/Lupus program—and is excited to expand her work. In addition to heading up the RA team, she is co-principal investigator on a technology grant with Harvard, for which she will lead the lab work on Sjogren’s at URMC, and is co-investigator with New York University on the lupus disease team.

It is estimated that these grants will bring more than $10 million to URMC over the course of funding.

The new grant will enable the implementation of high-dimensional technology that has been developed in the last decade and apply it to patient-focused research. The prior AMP grant allowed researchers to isolate single cells in target tissue for the first time for research in a “disease deconstruction” approach, and this next stage of the project will incorporate “disease reconstruction”—looking spatially within tissue to determine what cells are next to each other, how they communicate, and how environmental influences affect the cells and/or the disease.

Collaborations among URMC Cores have played a pivotal role in this research because of their expertise and technological developments. Anolik worked closely with John Ashton (’08, PhD ’11, MBA ’17), director of the UR Genomics Research Center, to develop the single-cell approaches during the last grant. Spatial transcriptomics, a process that maps gene activity in a tissue sample, is being further spearheaded by Edward Schwarz, PhD, director of the Center for Musculoskeletal Research (CMSR), and Alayna Loiselle (PhD ’09), associate professor of Orthopaedics. CMSR has provided critical tissue processing for the AMP and will be an ongoing collaborator as spatial transcriptomics approaches are expected to be a key modality. Brendan Boyce, MBChB, professor of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, will continue as a key collaborator for tissue histology.

“Relationships will help solve problems in all diseases,” said Anolik. “The collaboration of multiple departments within URMC is key, but combining research with the other institutions in the AMP AIM network is critical as well, because of the value of input from different places across the country, even the world, where expertise, environmental factors, and patient populations may be different.”

Advancing Treatment URMC Part of Collaboration Awarded $10M for Pediatric Concussion Research

Researchers at URMC are part of a collaborative project, led by the University of California, Los Angeles, that will study concussions in children and teens. The project, which was awarded $10 million from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, will test ways to predict which kids will develop persistent symptoms after a concussion, so researchers can study how to help them recover faster.

The grant to the Four Corners Youth Consortium, a group of academic medical centers studying pediatric concussions, will support Concussion Assessment, Research and Education for Kids— or CARE4Kids—a multisite study that will enroll more than 1,300 children and teens nationwide, including an estimated 240 in the Rochester area.

Every year, more than 3 million people in the U.S. are diagnosed with concussions. Symptoms continue to plague 30 percent of patients three months after injury, and adolescents face an even higher risk of delayed recovery. Chronic migraine headaches, learning and memory problems, exercise intolerance, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depressed mood are common.

The pre-teen and teen years are critical for psychosocial and brain development, and researchers fear what long-lasting concussion symptoms could mean for the developing brain. “Prolonged concussion recovery can have an enormous impact on the lives of teens and pre-teens, often setting the stage for academic difficulties, persisting mood disorders, and chronic pain,” said Jeffrey Bazarian (MD ’87, Res ’90, MPH ’02), professor of Emergency Medicine at URMC, who will lead the Rochester study site. “Early evaluation and treatment for kids at high risk for prolonged recovery is our best hope for preventing an acute injury from becoming chronic.” The study, which focuses on children between the ages of 11 and 18, will unfold in two phases. The first part will evaluate children with concussions to identify a set of biomarkers—including those related to changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and pupil reactivity—that could predict which kids will develop persistent symptoms after a concussion. The next will seek to confirm that these biomarkers accurately predict prolonged symptoms in a second group of children diagnosed with concussions.

Ultimately, the team hopes to develop an algorithm to help health care providers diagnose and treat concussions and enable the development of therapies that could help kids recover from concussions more quickly.

“Discovering objective biomarkers for persistent post-concussion symptoms will permit earlier intervention and future use of specific treatments for these patients,” said national project leader Christopher Giza, MD, director of the UCLA Steve Tisch BrainSPORT Program and professor of Pediatrics and Neurosurgery at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and Mattel Children’s Hospital. “Our big goal is to alleviate suffering and promote maximal recovery.”

In addition to URMC, the study is also currently recruiting participants at UCLA Mattel Children’s Hospital, Children’s National, Seattle Children’s, the University of Washington, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, and Wake Forest School of Medicine. Indiana University, the National Institute of Nursing Research, the University of Arkansas, the University of Southern California, and the University of Utah are also involved.

The URMC team also includes Jonathan Mink, MD, PhD, the Frederick A. Horner, MD, Distinguished Professor in Pediatric Neurology, and Spencer Rosero, MD (Res ’96, Flw ’00), professor and interim chief of Cardiology. Jeffrey Bazarian, MD

Infectious Diseases ‘Immune Distraction’ from Previous Colds Leads to Worse COVID Infections

A URMC study shows that prior infection and immunity to one of the common cold coronaviruses may have put people at risk of more severe COVID illness and death.

Published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases, the study examined immunity to various coronaviruses, including the COVID-causing SARS-CoV-2 virus, in blood samples taken from 155 COVID patients in the early months of the pandemic. Of those patients, 112 were hospitalized and provided sequential samples over the course of their hospitalization.

These hospitalized patients experienced a large, rapid increase in antibodies that targeted SARS-CoV-2 and several other coronaviruses. While big boosts in antibodies is usually a good thing, in this case it wasn’t.

The study showed that these antibodies were targeting parts of the spike protein, which sits on the surface of coronaviruses and helps them infect cells that were similar to common cold coronaviruses the immune system remembered from previous infections. Unfortunately, targeting those areas meant the antibodies could not neutralize the new SARS-CoV-2 virus. When levels of these antibodies rose faster than levels of SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies, patients had worse disease and a higher chance of death.

“In people who were sicker—those who were in the ICU or died in the hospital, the immune system was responding robustly in a way that was less protective,” said lead study author Martin Zand, MD, PhD, senior associate dean of Clinical Research at URMC. “It took those patients longer for the immune system to make protective antibodies… unfortunately, too late for some.”

This study adds to a growing pool of evidence that immune imprinting is at play in COVID immune responses. Zand, who is also a co-director of the University of Rochester Clinical and Translational Science Institute, likens this phenomenon to “immune distraction”: immunity to one threat (seasonal coronaviruses) hijacks the immune response to a new, but similar, threat (SARS-CoV-2). Immune imprinting has been linked to poor immune responses to other viruses, like flu, and can have implications for vaccine strategies.

By some predictions, COVID is likely to be with us for a long time—with new, milder strains emerging and circulating on an annual or seasonal basis. If those predictions hold true, the study suggests that we will need to regularly develop new vaccines targeting the new strains of SARS-CoV-2. While none have come to market yet, pharmaceutical companies such as Pfizer and Moderna have been developing and testing new versions of their COVID vaccines as new variants of concern have emerged.

“We should expect that development of new vaccines is a good thing,” said Zand. “It doesn’t mean the original science was wrong. It means nature has changed. If we want an immune system that pays attention to the right stuff, we need to teach it new tricks with different vaccines.”

Health Equity More Oversight Needed to Improve End-of-Life Care for Assisted Living Residents

Residents of assisted living facilities in states with less rigorous regulations are more likely to die without hospice or at-home end-of-life care, according to a study led by URMC’s Helena Temkin-Greener, PhD, professor of Public Health Sciences, that was published in the journal Health Affairs.

Unlike nursing homes, which are highly regulated by federal and state governments, assisted living communities fall under greatly varying oversight for issues such as minimum staffing levels, depending upon where a person lives. While assisted living communities have become a more common residential care choice for older Americans who require assistance with daily care needs and other supportive services, regulation of these communities varies from state to state, and there has been little analysis of care outcomes.

The study looked at end-of-life care for 100,783 residents who died in 2018–2019 in 16,560 assisted living communities, and specifically at whether they died at home and under hospice care or after transfer to a nursing home or hospital. Overall, 60 percent of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries residing in assisted living died at home, and more than 84 percent of them had hospice care. The probability of dying at home was significantly lower by dual Medicare-Medicaid status but not by race or ethnicity, suggesting dual-status residents may have worse access to high-quality end-of-life care.

Black residents were significantly less likely to be enrolled in hospice before death; several previous studies have shown that Black families are more likely to advocate for continued and aggressive medical treatment at the end of life—a legacy of mistrust in the health care system. Residents were also less likely to die at home or with home hospice in states with lower regulatory oversight of assisted living communities.

Study authors believe these findings should help inform efforts to ensure more equitable access to end-of-life care planning and services in assisted living communities and suggest an important role for state-level regulation in their implementation.

This research was supported with funding from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation.

Strong Expansion Project Strong to Triple Size of ED, Add 100+ Private Inpatient Rooms

An extensive expansion project at Strong Memorial Hospital will add 200 examination/treatment and patient observation stations to the Emergency Department and Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program, as well as a nine-story inpatient bed tower to include more than 100 private rooms. Scheduled for completion in 2027, the project will help to address chronic bed shortages and ED overcrowding issues, which existed prior to but were exacerbated by the COVID pandemic.

University of Rochester President Sarah Mangelsdorf described the expansion, which will add more than 650,000 square feet of new hospital space, as an investment in the community and the medical center. “Educationally, it is a powerful medical-center asset to have a large teaching hospital integrated physically with our three professional schools for clinicians and with the research labs where medical discoveries are made,” she said. “This project will represent a critical investment in modernizing our community’s and our region’s largest hospital for 21st century needs.” Highlights of the project include: ■ Specially designed clinical spaces to serve patients with cardiovascular disease, including ICUs and dedicated inpatient rooms. ■ The most comprehensive modernization project since the current patient tower was completed in 1975, providing private rooms for all patients. ■ ED expansion from 46,000 to 175,000 square feet, including a

Fast Track section enabling patients with lower-acuity concerns to be treated and released quickly. ■ A larger, covered entrance to serve patients as they arrive, with a more efficient triage and registration area and larger waiting room. ■ An 80,000-square-foot parking garage.

Environmental Science Study Links Fracking, Drinking Water Pollution, and Infant Health

Public water supplies are polluted by shale gas development, commonly known as fracking, and can impact infant health, according to a URMC study published in the Journal of Health Economics. The findings call for closer environmental regulation of the industry, since levels of chemicals found in drinking water often fall below regulatory thresholds.

“In this study, we provide evidence that public drinking water quality has been compromised by shale gas development,” said study co-author Elaine Hill, PhD, an associate professor with the University of Rochester Departments of Public Health Sciences, Economics, and Obstetrics & Gynecology. “Our findings indicate that drilling near an infant’s public water source yields poorer birth outcomes and more fracking-related contaminants in public drinking water.”

Hill’s previous research was the first to link shale gas development to drinking water quality and has examined the association between shale gas development and reproductive health, along with the subsequent impact on later educational attainment, higher risk of childhood asthma exacerbation, higher risk of heart attacks, and opioid deaths. Her research brings an important perspective to the policy discussion about fracking, which has often emphasized the immediate job creation and economic benefits without fully understanding the long-term environmental and health consequences for communities in which drilling occurs.

This new study is a complex examination of the geographic expansion of shale gas drilling in Pennsylvania from 2006 to 2015, during which more than 19,000 wells were established in the state. Hill and co-author Lala Ma, PhD, of the University of Kentucky, mapped the location of each new well in relation to groundwater sources that supply public drinking water. They linked this information to maternal residences served by those water systems, as indicated on birth records, and U.S. Geological Service groundwater contamination measures. This data set allowed the two to pinpoint infant health outcomes—specifically, preterm birth and low birth weight—before, during, and after drilling activity.

Other studies have shown elevated levels of chemicals associated with fracking in surface water; however, these levels often tend to be below federal guidelines, are not monitored closely, and even if detected, do not rise to levels that trigger remediation. Hill’s and Ma’s study indicates that fracking-related chemicals—including dangerous volatile organic compounds—are making their way into groundwater that feeds municipal water systems, and that the potential for contamination is greatest during the pre-production period when a new well is established. With only 29 out of more than 1,100 shale gas contaminants regulated in drinking water, the results suggest that the true contamination level is higher. The study specifically finds that every new well drilled within one kilometer of a public drinking water source was associated with an 11 to 13 percent increase in the incidence of preterm births and low birth weight in infants exposed during gestation.

“These findings indicate large social costs of water pollution generated by an emerging industry with little environmental regulation,” said Hill. “Our research reveals that fracking increases regulated contaminants found in drinking water, but not enough to trigger regulatory violations. This adds to a growing body of research that supports the re-evaluation of existing drinking water policies and possibly the regulation of the shale gas industry.”

Innovation Huntington’s Study Recognized for Potential to ‘Shape Medicine’

The journal Nature Medicine has identified a phase-3 study of pridopidine—a promising treatment for Huntington’s disease—as one of 11 clinical trials that will shape medicine in 2022. The URMC Clinical Trials Coordination Center (CTCC) is providing global operational support for the study, which is being conducted at more than 50 sites across the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and Europe.

The journal notes that the PROOF-HD clinical trial is one of several ongoing studies of pridopidine as a potential therapy for Huntington’s, ALS, and other neurodegenerative diseases. Pridopidine is an oral small-molecule compound that binds and activates the Sigma-1 receptor (S1R), which is present at high levels within the brain. By activating S1R, the drug helps boost production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, a protein with neuroprotective properties. This protein is found at reduced levels in people with Huntington’s disease.

The PROOF-HD study is being conducted by Prilenia, the drug’s manufacturer, and HSG—a global network of more than 400 investigators, coordinators, scientists, and Huntington’s disease experts. CTCC has collaborated with HSG on a number of clinical trials, including the First-HD study, which led to the FDA’s 2017 approval of deuterated tetrabenezine for Huntington’s.

CTCC is providing scientific, technical, logistical, and operational logistical support for the PROOF-HD study, which is anticipated to run through April 2023.

Part of the Center for Health + Technology, CTCC is a unique academic-based research organization with decades of experience working with industry, foundations, and governmental researchers in bringing new therapies to market for neurological disorders. Since its inception in 1987, it has played a central role in bringing seven new drugs to market to treat Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and periodic paralysis.

Elise Kayson (MSN ’84), RNC, ANP, director of CTCC Clinical and Strategic Initiatives and Huntington Study Group (HSG) co-chair, is project lead for the PROOF-HD study.

Mental Health Research Major Grant Funds Research to Understand Key Features of OCD: Inflexibility and Avoidance

A team of scientists from across the country will use a $15.6 million award from the National Institute of Mental Health to investigate the brain networks central to obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). The work will build on more than 15 years of research by lead investigator Suzanne N. Haber, PhD, and collaborators to further understand the underlying biology of the disease and guide the development of effective treatments.

“Obsessive compulsive disorder is among the most disabling psychiatric disorders,” said Haber, professor of Pharmacology and Physiology, Neuroscience, and Psychiatry. “It affects 1 to 3 percent of the population worldwide, yet it hasn’t received the same level of attention as other mental health disorders. We’re excited to receive this funding and use translational methods to understand circuit dysfunction in the disease and to develop new treatment approaches that can improve the lives of patients.”

The five-year grant funds a Silvio O. Conte Center for Basic and Translational Mental Health Research at the University of Rochester. Haber has received previous Conte Center grants that have propelled scientists’ understanding of the disease. Major findings include the discovery of a narrower, more defined network of brain regions, dubbed the “OCD network,” that underlie the disorder. The new grant will allow scientists to test the idea that behavioral inflexibility in OCD results from faulty connections between brain circuits in this network.

“The identification of the OCD network is the result of years of research by us and others that demonstrates a set of connected brain structures that are central to linking stimuli to decisions that we make about actions that lead to certain outcomes,” Haber said.

Individuals with OCD often compulsively avoid or take specific actions to avoid a potential bad outcome, despite a low likelihood of that outcome occurring. The action persists despite the awareness that it is not productive. “By studying this network and its role in different aspects of decision making and behavioral flexibility, we hope to better understand how dysfunction of neural connections can result in obsessions and compulsions,” she said.

The University of Rochester team will combine studies of anatomy with high-resolution diffusion and functional imaging to identify relevant connections in the OCD network. This data will help scientists probe abnormalities by using imaging tools in people with OCD. It will also help identify individual variation in critical network locations. Finally, these results will be used to explore new ways to modulate the network, such as through the use of deep brain stimulation and low-intensity focused ultrasound.

Haber notes that the OCD network, which regulates normal behaviors related to the flexibility of responses, is central not only to OCD, but a wide range of other mental health conditions, such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and addiction. Findings from this work could influence the management of these illnesses as well.

The University of Rochester is one of six institutions participating in the research.

Neurology Documentary Sheds Light on the Parkinson’s ‘Pandemic’

A documentary produced by the University of Rochester Center for Heath + Technology (CHeT), The Long Road to Hope, tells the story of individuals with Parkinson’s and efforts to study, treat, and prevent the disease from a global perspective.

The film features 12 patients with Parkinson’s from the U.S., Canada, the U.K., and the Netherlands, along with medical commentary from URMC Neurologist Ray Dorsey, MD, and Bas Bloem, MD, PhD, of Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands.

Dorsey and Bloem discuss the pandemic scope of this largely preventable disease and how addressing it will require a global effort with the same level of focus and resources employed with success to address other public health challenges, such as polio, HIV, and breast cancer.

The film is an outgrowth of ParkinsonTV, a video series launched in 2017 by CHeT and Bloem’s team, which had already created a Dutch-language version of the series. The third season of the English series includes the full documentary plus episodes featuring patients in the film and is available and free to watch on the ParkinsonTV website (parkinsontv.org/three).

The Long Road to Hope was produced and directed by Norman Yung, Alistair Glidden, and Iyad Amer, along with CHeT, and supported by a grant from Roche.

Clinical Innovation Living Donation Opens New Doors for Colorectal Cancer Patients in Need of Liver Transplants

Nearly three years ago, Doug Vincent was given a year to live, having been diagnosed with stage four colorectal cancer that had spread to his liver and was too extensive to be removed. Today, he is alive and cancer-free, thanks to a living-donor liver transplant conducted through an innovative clinical trial at URMC.

Vincent was one of 10 patients treated through a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Surgery, demonstrating the first successful living-donor liver transplants in North America for patients who have liver-confined colorectal cancer tumors that cannot otherwise be removed by surgery.

According to the study, a year and a half after their living-donor liver transplants, all 10 patients were alive, and 62 percent remained cancer-free.

“This [study] brings hope for patients who have a dismal chance of surviving a few more months,” said first author of the study, Roberto Hernandez-Alejandro, MD, chief of the Abdominal Transplant and Liver Surgery Division at URMC. The division has performed more living-donor liver transplants for patients with colorectal liver metastases than any other center in North America. “With this, we’re opening opportunities for patients to live longer—and for some of them to be cured.”

The study, which was conducted across URMC, the University Health Network, and

Cleveland Clinic, focused on colorectal cancer in part because of its tendency to spread to the liver. Nearly half of all patients with colorectal cancer develop liver metastases within a few years of diagnosis, and 70 percent of liver tumors in these patients cannot be removed without removing the entire liver.

Unfortunately, deceased-donor liver transplant is not a viable option for most of these patients because their liver function is fairly normal—despite their tumors. That lands them toward the bottom of the national organ-transplant waiting list. In North America, one in six patients on this list dies each year while waiting for an organ.

Thanks to recent advances in cancer treatments, many of these patients are able to get their cancer under systemic control, which means their liver tumors are the only things standing between them and a “cancer-free” label. It also increases the odds that these patients—and their new livers—will remain cancer-free, which is crucial when balancing the benefit to the patient with the risk to a living donor.

“I’ve seen so many cancer patients whose cancer was not spreading, but we couldn’t remove the tumors from their liver and we knew they would die,” said Hernandez-Alejandro, who is also an investigator at the Wilmot Cancer Institute. “We hoped living-donor liver transplant could give them another chance.”

Because it offered a last resort, the study attracted more than 90 patients from near and far. All patients and donors went through a rigorous virtual and in-person screening process to ensure they were good candidates for the procedure, and they were educated about the risks of the surgery and the possibility of cancer recurrence. Patients and donors underwent staggered surgeries to fully remove patients’ diseased livers and replace them with half of their donors’ livers.

Patients have been closely monitored via imaging and blood analysis for any signs of cancer recurrence and will continue to be followed for up to five years after their surgeries. At the time the study was published, two patients had follow-ups of two or more years, and both remained alive and well—cancer-free.

“This study proves that transplant is an effective treatment to improve quality of life and survival for patients with colorectal cancer that metastasized to the liver,” said senior study author Gonzalo Sapisochin, MD, a transplant surgeon at the Ajmera Transplant Centre and the Sprott Department of Surgery at the University Health Network.

“As the first successful North American experience, it represents an important step toward moving this protocol from the research arena to standard of care,” adds Sapisochin, who is also a clinician investigator at the Toronto General Hospital Research Institute and an associate professor in the Department of Surgery at the University of Toronto.

Roberto Hernandez-Alejandro, MD

aging reIMAGINED

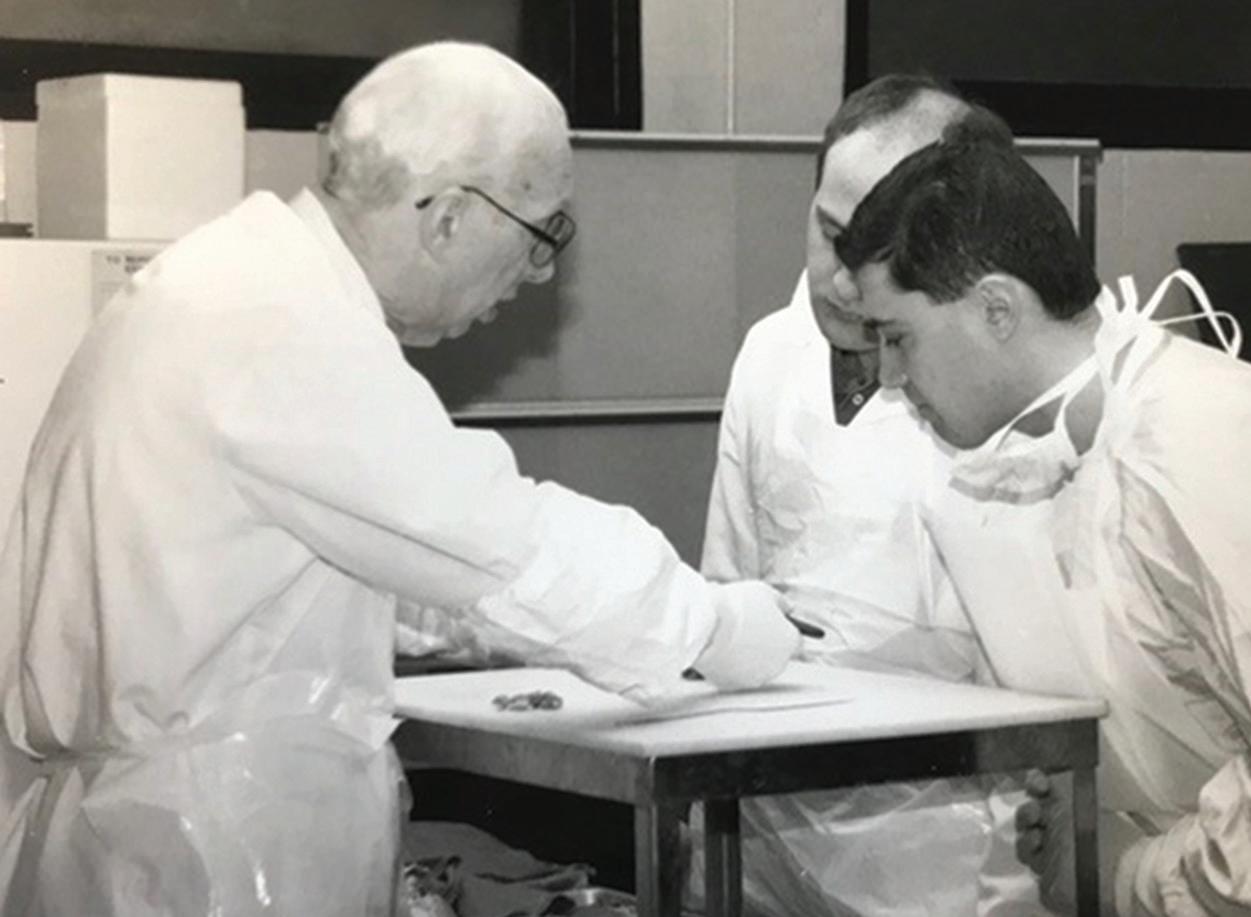

University of Rochester Professor Emeritus William Hall, MD.

MAGINED

a new view of old age

By Sally Parker

One day in 2012, a group of women and men ages 50 to 91 stood, awkward and shivering, on a pool deck at Monroe Community College in Rochester. For some, it was the first time in years they had worn a swimsuit in mixed company. It was also the first day they would train for a triathlon. For eight weeks, they ran, cycled, and swam their way into race fitness. Two months later, more than 50 athletes lined up for the running leg of the race, and a vanguard of local Hell’s Angels’ riders, most in their late sixties or so, started them off with a roar.

-William Hall, MD

Almost everybody finished the certified sprint course triathlon—with a 750-meter swim, 12-kilometer bike ride, and five-kilometer run—all on the same day. “We were presenting them with a life option that they never would have thought possible, and within a week everybody was doing wonderful things. It was an enormous success,” says University of Rochester Medical Center Professor Emeritus William Hall, MD, who created the event with Carol Podgorski (MPH ’85, PhD ’90, MS ’05), professor of Psychiatry. At the time, Podgorski and Hall headed the Center for Lifetime Wellness, which supported the training. AARP provided funds to develop and host it, the first of its kind in New York state.

“What it did for me was solidify this idea that we often sell older people short in terms of what they can do,” Hall says. “That’s when things really got started. It was an amazing example of what is possible to do in Rochester.”

Off and Running

Training for the tri continued for several more summers. By the end of the program, the concept of conditioning and training for adults ages 50 and over had gained a solid footing. It was the natural outgrowth of a University of Rochester tradition in geriatrics that began in the 1960s, long before a focus on healthy aging caught on elsewhere. Fifty years before Hall’s triathletes jumped into the pool at MCC, T. Franklin Williams, MD, was making waves with geriatrics care and research in Rochester. One of the founders of modern geriatrics medicine and a giant in the field (he directed the National Institute for Aging for eight years), Williams placed Rochester at the forefront of geriatrics before it was even a specialty. (See sidebar on page 17.) Williams mentored countless geriatricians across the country, including Hall and others who remained on home ground and built on his success. Today, geriatricians and scientists in the University of Rochester Aging Institute (URAI) are known around the world for groundbreaking research and older-adult care models. The volume of bench research, patient care, and community support related to aging in Rochester is staggering. From fracture centers to DNA research to community music programs for older adults, URAI integrates all such strengths across campuses. Many of these are replicated around the world. And experts here are sharing and collaborating more easily. “Promoting vitality in aging through discovery, collaboration, and innovation is what this Institute is all about!” says Annette (Annie) Medina-Walpole, MD, chief of the Division of Geriatrics & Aging, who directs the Institute with a contagious enthusiasm. “The UR Aging Institute is committed to promoting health, independence, and engagement, enabling all of us to live our best lives.”

Dirk Bohmann, PhD

Redefining Aging

Geriatricians have heard all the stereotypes of old age, usually starting with “it’s tough growing old,” followed by a list of ailments and an inevitable downward spiral of loss and limitations.

However, scientists and clinicians in the URAI say the picture doesn’t fit everyone’s experience of aging, nor did it ever: They are blowing those stereotypes out of the water, proving older adults can be capable of far more—cognitively, physically, socially—than previously believed. Vital and healthy advanced age is not only possible; for a growing number, like Hall’s triathletes, it’s what everyone should strive for. Hall and Susan Friedman, MD, MPH, professor of Medicine in the Division of Geriatrics & Aging, have continued the quest to promote healthy aging. A 2015 article they published in the Journal of the American Geriatrics Society notes that “collaborative efforts between geriatrics, communities, and individuals will set the stage for developing a healthier society for all to age well and successfully.” Friedman has gone on to publish additional papers on healthy aging and to launch the Lifestyle Medicine program at Highland Hospital. “People often think that aging is this inevitable decline. Forget about a fountain of youth. But it seems that the process of aging is really malleable and can be influenced,” says Dirk Bohmann, PhD, senior associate dean for Basic Research and the Donald M. Foster, MD, Professor in Biomedical Genetics, who has studied aging for more than 20 years. The need to study aging and to shift societal attitudes has never been more urgent. More than 10,000 people in the U.S. turn 65 every day, and the number of older adults will more than double to 88 million by 2050, according to the AARP. That’s more than 20 percent of the population. Not surprisingly, funding for aging research—from the National Institute on Aging and a growing roster of other sources—is on a steady rise. Far from a bleak outpost of last-chance medicine, aging research and geriatrics medicine turn out to be an exciting place.

Into his late eighties, one of the founders of modern geriatric medicine rode his bike to work every day from his home on Park Avenue to Monroe Community Hospital (MCH). Rochester’s reputation for aging expertise can be traced back to T. Franklin Williams, MD. Long before the specialty had a name, he trained a generation of geriatricians who went on to become leaders in the field.

Williams and his wife, Catharine Carter Catlett Williams, a social worker and early advocate for restraint-free nursing homes, came to Rochester in 1968 from the University of North Carolina. He was recruited as a professor of Medicine and to direct MCH, which remains a major center for geriatrics care and education in the Rochester community. Teaching was one of his greatest joys, former fellows recall, and he established one of the first geriatrics fellowship programs in the country. As his reputation grew, he was asked to lead the National Institute on Aging, which he did for eight years in the 1980s and ’90s under two administrations. When he was done, Williams returned to Rochester to continue his work for another 20 years. “We were lucky to have Frank and his wife, Carter. They were really the beginning of it,” says geriatrician Robert McCann, MD, former chief of Medicine at Highland Hospital and CEO of Accountable Health Partners, URMC’s clinically integrated network of hospitals and physicians. “He was such a humble, wonderful man.”

T. Franklin Williams, MD, and Catharine Carter Catlett Williams

The URAI Exective Committee includes Yeates Conwell, MD; Dirk Bohmann, PhD; Kathi L. Heffner, PhD; Ryan Gilmartin, MHA, and, not pictured, Annie Medina-Walpole, MD; Andrei Seluanov, PhD; and Vera Gorbunova, PhD.

The RoAR and OARHS of Research

Basic aging research began in earnest at the University many years ago. Bohmann and University professors of Biology and Medicine Vera Gorbunova, PhD, and Andrei Seluanov, PhD, formed RoAR, Rochester Aging Research Center, bringing together investigators in basic and translational research at the Medical Center and River Campus through seminars, an Aging Research Day, pilot grants to advance the work, and ways to collaborate. Podgorski and Professor and Vice Chair of Psychiatry Yeates Conwell, MD, started OARHS, the Office of Aging Research and Health Services, to gather clinicians, researchers, and educators in clinical care and population health. As a complement to basic research, it was a first step in linking basic scientists, clinicians, caregivers, and policy experts around the University. While the two efforts weren’t officially siloed, neither were they connected in any real, change-making way. Collaboration between lab scientists and geriatricians wasn’t natural at first, Bohmann recalls. “RoAR did basic research on the fundamentals of aging, the science behind it, whereas OARHS and geriatrics work on the actual state of being old. These are two different cultures. Still, we figured it would be very useful to support communication between them,” he says. They came together in the newly formed URAI in 2019, spurring a whole new level of excitement and potential for the study of aging and the care of older adults in our health system and community.

Andrei Seluanov, PhD, and Vera Gorbunova, PhD

An Age-Friendly Focus

From a clinical point of view, creating an institute that addresses an increasing need is important, says Mark Taubman, MD, URMC CEO and dean of the School of Medicine and Dentistry. The UR Aging Institute plays a huge part in the University’s strategic plan and mission: to improve the health of the region’s population and enhance UR’s reputation as a research-oriented university and medical center.

We have an opportunity— because of who we are and what we already do with aging— to make a national mark. And we’re ripe to do it.

-Mark Taubman

At every level of care and in every setting, age-friendly health systems follow four elements of high-quality care, the 4Ms: ■ What Matters to You—Know and align care with the older adult’s specific health outcome goals and preferences ■ Mentation—Prevent, identify, treat, and manage dementia, depression, and delirium ■ Mobility—Ensure the older person moves safely every day ■ Medication—If it’s necessary, make sure it doesn’t interfere with the other three Ms

“I look at it as a ‘no wrong door’ approach. Any older adult who comes in, no matter what their need is, they’ll have consistent, evidence-based care that is focused on the unique needs of older adults,” says Thomas Caprio, MD (Res ’03, Flw ’05, MPH ’10, MS ‘15), principal investigator of the Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP) grant and director of the Finger Lakes Geriatric Education Center. The GWEP grant and the URAI fund Geriatric Faculty Scholars from the School of Nursing and Medicine/Dentistry to become geriatrics champions and further disseminate the AFHS within their own specialty, program or department.

Thomas Caprio, MD

To that end, in May 2022, Strong Memorial and Highland hospitals received the highest level of certification as an Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS), an initiative of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement and the John A. Hartford Foundation with the American Hospital Association and the Catholic Health Association of the United States.

As the name suggests, AFHS certification is the best in evidence-based health care for older adults. It’s a focus on what matters to patients receiving care and on improving health outcomes for them—and a perfect fit with the URAI’s mission. “Right now we have a region that’s not growing in population—it’s aging. More and more of the people we take care of are an aging population, and the diseases are age-related,” Taubman says. “We have an opportunity—because of who we are and what we already do with aging—to make a national mark. And we’re ripe to do it.”

In the Institute’s three main areas—research, care, and community— University of Rochester experts are pushing against traditional boundaries of what aging looks like. They’re questioning long-held, limiting assumptions about the physical, mental, emotional, and social abilities of older adults. And they’re doing things quite differently in their clinical studies and scientific investigations.

vital DISCOVERY

Research ranges from basic science in the lab to data science and multidisciplinary aging studies. Scientific discoveries will be translated into creative approaches to increase longevity and health span as well as improve patient care and clinical outcomes. (See page 22.)

The primary aim is to increase access to high-quality geriatrics care—driven by technology and data—in the region. URAI makes sure best practices and care models are shared across the system. A big focus is on workforce education, including training providers of all disciplines and disseminating the principles of the AFHS. (See page 30.)

This pillar focuses on older adults in the Rochester community. It creates a loop of learning that goes both ways between the University and community nonprofits and individuals. URMC specialists and aging organizations offer evidence-based evaluations and lifestyle interventions that promote vitality in aging. And older adults become advocates, teachers, and researchers themselves, enlivening the university community with the spirit of aging. (See page 34.) “We’re not going to do this all at once,” adds Conwell, a member of the URAI executive committee. “Why did we take on a mission for the Institute that is as broad as this is, to include research and education and clinical care and population health? It has to do with the notion of the biopsychosocial model.” The BPS model, the foundation of medical training and care at the University of Rochester, insists on treating not only the physical but the emotional, mental, and social aspects of health. It was conceived by URMC doctors George Engel and John Romano in the 1970s and is now in wide use around the world.

“It is inherently in the air we breathe here, and we want to disseminate that and make that an important part of how we work,” Conwell says. Rochester is the perfect living laboratory to re-envision older age, says Hall, noting that he and colleagues who came up under Williams had support not only from the University but from the community. “There are so many resources to help people age gracefully in Rochester,” he says. “That is probably not as well known here as it is nationally. Somehow this community saw the tea leaves and really tried to develop collaborative programs, so Rochester is well-recognized throughout the country for that form of leadership. “If you’re going to have to age anyway, you might as well do it here in Rochester.”

vital CARE

vital LIVING

Aging research is a wide-open field with a lot of exciting perspectives. But with abundant opportunities come challenges. For the Institute, this means being selective. “We started by building on our existing strengths—and there are many—and now we are moving forward by creating new, unprecedented partnerships and collaboration across our institution that align with our mission and vision,” Medina-Walpole says.

Annie Medina-Walpole, MD, has built a career around one word: yes. “I said ‘yes’ more than ‘no’. I think that opens so many doors,” says the chief of the Division of Geriatrics & Aging, the Paul H. Fine Professor of Medicine, and director of the UR Aging Institute. Her latest “yes” was an enthusiastic one to URMC CEO and SMD Dean Mark Taubman, MD, who in 2016 charged her with building the Institute. At the time, she was the University’s representative to the Hedwig van Ameringen Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program, a prestigious, yearlong, national fellowship for women in medicine. She started building a plan for the Institute as her fellowship project, bringing together people from every corner of the University to create an infrastructure and priorities in each area. Medina-Walpole is a familiar name in the world of American geriatrics. She joined the American Geriatrics Society as a chief resident, and by midcareer she was on the board, serving as president in 2020-2021. Right now, she’s co-leading an examination of diversity, equity, and inclusion for the 6,000-member society, urging a rethink on ageism and racism in health care, particularly for older people of color—an issue that came to light during the pandemic. “It’s not about just hosting a training session or webinar, a one-and-done. We’re embedding this work into the fabric of our society,” she says. “We’re creating a multi-year, multi-pronged approach to address the intersection of structural racism and ageism. Our ultimate goal is health care systems that are free of discrimination and bias.” Medina-Walpole has held just about every leadership post in geriatrics education at URMC since joining the faculty in 1998. She sees her role in the Institute as that of a convener, a connector, and a mentor. Outside the University, she is helping to stitch the Institute into the wider community, where, like Medina-Walpole herself, older adults are building networks of their own to improve the lives of their peers. “We are not just focused on how we can help older people, but also on how they can help us. It’s important to see aging in a different light,” she says. “I truly believe the possibilities are endless with what we can do to empower older people to engage with our University, live longer and healthier lives, and ensure that everyone can age with vitality.”

vital DISCOVERY

The longest-living mammals on Earth, bowhead whales, can live more than 200 years.

In their lab on the University’s River Campus, a research team led by professors of Biology and Medicine Vera Gorbunova, PhD, and Andrei Seluanov, PhD, is studying cells in biopsied tissue from these giants of the ocean to uncover their secret to longevity. Their research into the mechanisms of longevity and genome stability goes back nearly 20 years and aims to solve one of the biggest mysteries of biology: aging. The goal: Slow aging, slow disease. “Aging is a risk factor for many diseases that are afflicting mankind. So, if we could slow down aging, we also would slow cancer, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and other conditions that increase with old age,” says Gorbunova, who is the Doris Johns Cherry Professor and co-director of the Rochester Aging Research Center. “If we succeed to slow aging or improve the process of aging, then we will be able to delay many diseases,” Seluanov adds. Their lab is part of the Vital Discovery pillar of the UR Aging Institute (URAI). In this area, basic and clinical researchers work to study longevity and the causes and conditions of aging—from basic science to translational studies to health care policy. “We are building a strong research infrastructure that will translate scientific discovery into clinical care,” says URAI Director Annie Medina-Walpole, MD. “We’ll ask how and why we age and what factors determine longevity, life span and health span, and what interventions can be used to promote health, well-being, and vitality. This is how we’ll expertly care for the growing population of older patients in our region. And, finally, can we slow down the aging process itself, which can be viewed as the ultimate preventive medicine?”

Funded by a URAI pilot grant, Michelle Janelsins-Benton, PhD (pictured at right with Nikesha Gilmore, PhD), and Luke Peppone, PhD, are working with the Gorbunova and Seluanov Lab in one of the first U.S. aging trials to come from basic research, testing a seaweed compound’s potential to quell the side-effects of chemotherapy in older adult patients with cancer.

At the Bench

In addition to bowhead whales, which are efficient at genome maintenance and DNA repair, Gorbunova and Seluanov study a variety of long-lived animals such as naked mole rats, beavers, squirrels, and bats. They, too, live long and have evolved unique molecular mechanisms of longevity and disease resistance. Bats, for example, have a unique immune system that is resistant to inflammation, a big driver of age-related diseases. The lab is a pioneer in comparative studies on aging, focusing on short- and long-lived animals. Its studies of Eastern gray squirrels (average lifespan: 24 years) and naked mole rats (32) have found additional pathways to putting the brakes on aging. For example, they’ve identified an important gene for longevity in the naked mole rat that, when transferred to mice, increases their longevity as well. Cancer incidence typically increases with age, but these long-lived animals naturally resist it. Studying the mechanisms of that resistance has led to new insights that will soon be tested on humans at Wilmot Cancer Institute. “The process of discovery is really amazing,” Seluanov says. “That’s what is fun. But in addition, we can apply that discovery to improve human health and help people. What can be better than that?”

When molecular biologist Dirk Bohmann, PhD, and his research team were recruited to URMC from the European Molecular Laboratory in 2001, he was using fruit fly genetics to understand how cells defend themselves against effects of environmental stressors such as toxins or radiation.

“It was clear that the ability of an organism to fend off these challenges wanes with age, contributing to the loss of resilience and fitness, thereby increasing the probability of disease and death. But it was unclear at a cell and molecule level why this happens,” says Bohmann. At the time, the University hosted the Nathan Shock Center of Excellence in Basic Biology of Aging with a grant from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Bohmann received a small pilot grant from the center to apply his work to aging. High-level publications and funding from the NIA followed, transforming his group into a leading aging research lab. Team members have gone on to become eminent researchers in their own rights. The fact that long life is a trait that can run in families suggests—and a lot of research confirms—that aging is not simply the result of a randomly determined, inexorable grindstone, but is influenced by genetics. This can explain the differences seen in older adults as they age. Hundreds of genes that influence aging have been identified in studies on a small earthworm known as caenorhabditis elegans. Many of these genes exist in humans, yet whether or how they will influence aging in humans is poorly understood. Studying how these genes function in model organisms, such as in earthworms, fruit flies, or rodents, provides insight into how to promote healthy aging in humans. The laboratory of Andrew Samuelson, PhD, associate professor of Biomedical Genetics, is using the worm to explore the fundamental mechanisms by which aging genes act, and how they may dictate lifespan, health span, and the onset of specific age-associated illnesses such as Alzheimer’s disease.

Supriya Mohile, MD

From the Bench to the Bedside

Because of the Institute, collaborations that bring basic research into the clinical setting are multiplying. Gorbunova and Seluanov, for example, are working with clinical scientists at Wilmot Cancer Institute to treat older patients suffering from the side effects of chemotherapy. And Wilmot works closely with URAI. More than 60 percent of people with cancer are ages 65 and over, and a third are older than 75. Even though those numbers are expected to rise as the population ages, older adults are severely underrepresented in clinical trials, says Supriya Mohile, MD, the Philip and Marilyn Wehrheim Professor of Medicine and director of Geriatric Oncology Research at Wilmot. Most cancer trial participants are in their fifties and early sixties. Resulting treatments are designed for younger adults who don’t have many of the challenges that come with older age, such as with memory, mobility, and multiple medications.

-Supriya Mohile

Allison Magnuson, DO

Still, the field of geriatric oncology has grown dramatically since Mohile’s training in the early 2000s, particularly in the last decade as clinicians and researchers try to understand the risks and benefits of treating cancer in older people, she says. Like much of the work done in the URAI, the geriatric oncology clinic at Wilmot, founded by Mohile and led by Allison Magnuson, DO (’02, Flw ’13, Flw ’14, MS ’20), associate professor of medicine, combines research with patient care. SOCARE—Specialized Oncology Care and Research in Elders— is recognized in the U.S. and abroad for providing the most comprehensive, evidence-based care for patients age 70 and older. With a team of six geriatric oncologists, it’s the largest clinical group of its kind in the country. The opportunity to do translational research while working with patients is a big draw for fellows and residents, and the program is growing from within as a result. Magnuson did fellowships in oncology and geriatrics at Rochester. Now director of SOCARE, she is researching ways to reduce cancer-related cognitive dysfunction, or “chemo brain,” in older patients, who are at greater risk. Magnuson’s latest research breaks new ground. She received a $2.5 million award from the NIA to study how oncologists can better deliver care to cancer patients who have pre-existing dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. About 7 percent of older cancer patients are in this situation, and current data provide no guidance on whether cancer treatments are safe for these individuals, how to assess the patient’s ability to reason and understand information, and how to have difficult three-way conversations between doctor, patient, and the patient’s representative when complex treatment decisions must be made. Magnuson plans to adapt and test an existing geriatric assessment tool for use in these cases.

Vice Chair for Basic and Translational Science Laura Calvi, MD, holds an NIA-supported $2.3 million grant focused on the mechanisms by which the bone marrow ages. This is significant because abnormal mature cells in the bone marrow can cause inflammation and bone loss, and can support the development of leukemia and other blood cancers. Calvi, who holds professorships in the departments of Medicine; Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; Pharmacology and Physiology; and the Cancer Center, is working with the Center for Musculoskeletal Research to understand how phagocytosis of dead and dying cells affects bone aging. Kah Poh Loh, MBBCh (Flw ’18, Flw ’19), a hematologist, oncologist, and geriatrician, develops ways for older cancer patients to use digital technology, such as mobile apps, for behavioral and supportive care interventions. Before launching an app-based trial, for example, she consults with older patients on user-friendly design—from font size to information flow. Loh and two other Wilmot Cancer Institute researchers, Michelle Janelsins-Benton (MS ‘05, PhD ‘08, MPH ’13), associate professor of Surgery, Radiation Oncology, and Neuroscience, and Paula Vertino, PhD, professor of Biomedical Genetics and of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, were awarded the inaugural UR Aging Institute pilot grant this past year. “In every step of the design, they’re partnering with patients. It’s not ‘no,’ it’s ‘how,’” Mohile says. “They’re doing really interesting work, and they’re rising stars nationally.” Eight to 10 geriatrics professionals and students come from around the world every year for SOCARE’s visiting scholars program. After they return home to start clinics and research of their own, they replicate what they’ve learned with ongoing guidance from Wilmot colleagues.

Kah Poh Loh, MBBCh

The Division of Geriatrics faculty rose to the challenges of COVID-19, impacting the clinical and research agenda of URMC and the community. From left: Annie Medina-Walpole, MD; Brian McGarry, PhD; Sarah Howd, MD; Jennifer Muniak, MD; Raje Sathasivam, MBBS; Dallas Nelson, MD; Asma Bawaney, MBBS; Luke Cheung, MD; Tom Caprio, MD; Ryan Gilmartin, MHA; Ian Deutchki, MD; and Joe Nicholas, MD.

Alzheimer’s Disease, Dementia, and Dementia Care

A new T32 training grant from the NIA will support six PhD students each year who are studying Alzheimer’s disease and aging, says Kerry O’Banion, MD, PhD (Flw ’91), vice chair and professor in the Department of Neuroscience. O’Banion and Gorbunova are co-principal investigators on the five-year, $1.44 million grant. Participants will study the basic biology of aging and neuroinflammation, attend weekly seminars, and shadow staff in the Department of Psychiatry’s Memory Care Clinic. “The unique aspect is that PhD students seldom get to see the translational or clinical side that their research in, for example, mice might impact,” O’Banion explains. “You could call it a more holistic view of the challenge.” The grant confirms Rochester’s strengths in Alzheimer’s disease research, he adds. “It’s recognition that this is a place for training the next generation of investigators in this area.” More than 400,000 adults over age 65 in New York have dementia, and nearly 600,000 family caregivers provide 835 million hours of unpaid care every year, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. URMC has tapped into this need with a host of programs devoted more broadly to dementia and dementia care, as well as geriatric mental health and well-being. In these clinics and centers, translational research and patient care go hand in hand: ■ The Memory Care Program focuses on neurodegenerative conditions that affect adults and the aging nervous system, such as Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia. Patients receive diagnosis, treatment, and ongoing care. It opened 30 years ago and is the only program of its kind in upstate New

York that is part of a psychiatry department. The University of Rochester also has the only geriatric psychiatry fellowship program in upstate New York. “We have many clinical trials going at once and are a major site for testing of new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, including monoclonal antibodies,” says

Elizabeth (E.J.) Santos, MD (BA ‘94,

Flw ‘06, MPH ‘13), associate professor of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Medicine, and clinical chief of the Division of Geriatric Mental Health and Memory Care. “Our expertise in caring for patients with dementia is recognized nationally and internationally.”

■ AD-CARE—The Alzheimer’s Disease, Care, Research, and Education program is led by Anton Porsteinsson, MD (Res ’93), the William B. and Sheila Konar Professor of

Psychiatry. The lab participates in international studies in Alzheimer’s disease prevention, cognitive impairment, diagnostic tools, and behavioral disturbances. AD-CARE is co-located with the Memory Care Program, allowing access to world-class clinical care and opportunities to participate in cutting-edge research. ■ The Rochester Roybal Center for Social Ties & Aging Research, also known as Roc

STAR Center, is one of 135 Roybal Centers funded by NIA. The Roybal Center program focuses on the translation of discoveries from basic behavioral and social research into effective interventions to improve the lives of older people and assist institutions in adapting to the aging of our society. The Roc STAR Center, supported by a $3.6 million grant, is the only Roybal Center focused on the loneliness and social isolation of caregivers of a family member with dementia. Research has shown that loneliness increases risk for chronic disease and mortality as much as smoking, obesity, and a sedentary lifestyle. Despite this, there are few scientifically developed interventions to improve social connectedness. “Our work aims to fill this critical gap,” says Kathi Heffner, PhD, co-director of the center and the Marie Curran Wilson and Joseph Chamberlain Wilson Professor of Nursing, professor of Medicine and Psychiatry, associate chief of Research for the Division of Geriatrics & Aging, and a member of the URAI’s executive committee.

Through pilot fund research grants, the Roc STAR Center is building a person-centered portfolio of interventions that community organizations and long-term care facilities can offer struggling caregivers. For example, the center is collaborating with the Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program education series to develop Connections Planning, an online training module for long-term care providers and staff to treat and prevent loneliness and isolation in older adults.

Loneliness among older adults happens, but it is not the norm, says co-director Kimberly Van Orden, PhD (Flw ’10). “In fact, most older adults experience increased psychological well-being and satisfaction with relationships as they age. Social connectedness is actually an aging-related strength that can be capitalized upon to promote well-being.” ■ NEW Brain Aging Center—The Network for Emotional Well-Being and Brain Aging opened in 2021 with a $2.5 million NIA grant. It is a collaboration among five partners, including URAI and colleagues at Duke, UC Santa Cruz, Johns Hopkins, and Stanford universities. Researchers are studying how an aging brain affects emotional well-being in older adults, and how emotional well-being affects brain function and cognitive aging. ■ HOPE Lab—The Helping Older People Engage Lab conducts randomized clinical trials to discover ways to increase social connectedness and improve well-being through older age. ■ HARP—The Healthy Aging Research Program is a multidisciplinary clinical and behavioral research collaborative to promote healthy aging. HARP partners with the Roybal Center,

HOPE Lab, and the Elaine C. Hubbard Center for Nursing Research on Aging, as well as community organizations serving older adults, to help investigators design and implement clinical research studies with older adults.

■ The Stress and Aging Research Lab conducts basic clinical research on the ways in which stress and emotional well-being impact older adults’ immune systems and health outcomes, as well as randomized clinical trials of stress interventions to promote healthy aging. Geriatric psychiatrist

Yeates Conwell,

MD, studies suicide in older adults and is a lead investigator on the NEW Brain Aging Center’s recent grant. Suicide is the bleakest outcome, he says, but it has a lot to teach us about well-being. Studies show older people are on the whole more satisfied with their lives than young and middle-age people. Suicide is a stark reminder that some older adults cannot mobilize the resources that most of their peers can. So what went wrong?

-Yeates Conwell

“The work we do is helping older adults through physical and mental disorders and tough times, but at the same time I learn so much from them—about issues like resilience, stress management, and life experience,” says Conwell, professor and vice chair, of the Department of Psychiatry who directs the Geriatric Psychiatry program and is on the URAI’s executive committee. “My work is driven by the fact that we have so much to learn from older people.”

In the URAI’s Vital Discovery pillar, scientists are working closely with clinicians to bring their research into the living laboratory of health care.

A First in Aging Trials

The Gorbunova and Seluanov Lab is working with clinicians in Wilmot Cancer Institute on one of the first U.S. aging trials to come from basic research. In a recent mice trial, they administered a seaweed compound that activates a gene that can reverse aging. It rejuvenates the way DNA is packaged in the cell, carrying an extra dose of a gene that reorganizes mutated DNA strands into a normal configuration. Treated mice showed signs of improved fitness; they ran faster on the treadmill, and their tails became more flexible.

Now with Gorbunova, principal investigators Janelsins-Benton and Luke Peppone, PhD (BA ’99, MPH ’10), associate professor of Surgery, Orthopaedics, and Cancer, will use the same compound in a small trial with 32 older adult cancer patients who suffer from the side effects of chemotherapy. Funded by a pilot grant through the URAI, the trial will be one of the first bench-to-clinic trials to look at the fundamentals of aging. If the outcome is encouraging, they’ll test it with healthy participants. “That’s where the URAI really helped. We weren’t connected to the clinical side before,” Seluanov says. “This type of coordination is really enhanced by having the Aging Institute.” A regional collaboration also holds promise for research their lab and others do in the URAI. UR is partnering with the University at Buffalo and Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in early-phase drug development. The New York State-funded Empire Discovery Institute holds promise for translating URAI research efforts into therapeutically viable products, that target longevity genes to extend lifespan and health span to a point where commercial partners can develop them into FDA-approved medicines.

Data Played Out in a Pandemic

Health services researcher Brian McGarry, PT (PhD ‘16), assistant professor of Medicine and Public Health Sciences, studies whether health care systems that serve older adults are really set up to meet their needs. McGarry joins a prominent group of collaborators in the Department of Public Health Sciences, Department of Psychiatry, and School of Nursing engaged in studying the impact of organizational factors and health care policies on outcomes for nursing-home care, acute home-health care, and long-term services and supports their recipients, including veterans, using the CMS, AHRQ, VA, and additional data sources.

With a new five-year grant from the National Institute on Aging, McGarry will study how older adults with cognitive decline navigate the enormous amount of consumer choice built into Medicare. In his previous work as a physical therapist, McGarry saw firsthand how hard it was for patients to figure out. Now he studies how public policies are put into practice, how they affect the cost and quality of care, and how these policies can help support older adults when they are making difficult health care and health coverage decisions. He and other researchers in the Division of Geriatrics & Aging meet regularly with clinicians to vet aggregated administrative data, such as claims, to see if it tells an accurate story. “Most of my colleagues are clinicians working with older adults. I get to sit side by side with them and work on research questions that are pertinent to their practice and their patient population,” he says. “It’s something the Aging Institute embodies—making that connection between the number cruncher/researcher and the clinicians who are living the stuff day to day.” This collaboration also fuels McGarry’s research into the burden that COVID-19 imposed on nursing homes. In the early days of the pandemic, McGarry did rapid turnaround research for administrators and policy makers—for example, investigating the extent of staff shortages and the time it took to get COVID-19 test results. Now he is studying weekly data from facilities to see how testing might have been done differently to avoid the high number of nursing home deaths.

-Andrei Selanov

Brian McGarry, PT, PhD

Dallas Nelson, MD Ryan Gilmartin, MHA

Besides dampening demand for nursing home care, which has long-term implications for the industry, the pandemic took the lives of more than 150,000 residents in the United States. McGarry says this fact alone fuels his work, so his colleagues can prepare for the next outbreak. “That’s important to me. What could be done better? And what, from a systematic standpoint, could make nursing homes safer for the staff who work there and the residents who live there?”

The answer to that question is the driving force behind high quality, age-friendly care at our regional hospitals and nursing homes. Kevin McCormick, MD, PhD (Res ’96, Flw ’98), professor of Clinical Medicine, is leading regional efforts in geriatrics as the medical director of Jones Memorial Hospital in Wellsville, N.Y. UR Medicine Geriatrics Group (URMGG), led by Dallas Nelson, MD (Res ’03, Flw ’05), associate professor of Medicine, provides comprehensive care to some of our region’s most frail older adults in 12 skilled nursing facilities and 33 assisted and independent living facilities, while Santos, Adam Simning, MD, PhD, assistant professor, and others in the Department of Psychiatry’s Geriatric Mental Health and Memory Care Division provide telemental health services and supports to residents and staff of about 90 nursing facilities across the state of New York.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided unprecedented opportunities for crisis management and leadership within URMC, the Rochester community, and its surrounding regions; including the care of nursing home residents with COVID-19 infection, delivery of vaccines, boosters, and monoclonal antibody treatment; transition to telemedicine visits; and outbreak testing. McGarry; McCormick; Nelson; and Ryan Gilmartin, MHA, URMGG senior program officer, along with many other UR Medicine faculty and advanced practice providers, rose to this incredible challenge and exhibited extraordinary commitment, leadership, and expertise to coordinate and improve our community’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. (See photo on page 26.)

vital CARE

For older people, falling and breaking a hip is a sentinel moment. For some, it marks the beginning of the end.

In 2004, a team of orthopaedists and geriatricians at Highland Hospital saw an opportunity to change that trajectory. Realizing that medical issues that complicate later-life surgery weren’t being addressed, they created a model of geriatric fracture care that would be replicated around the world. The Geriatric Fracture Center at Highland, developed by Daniel Mendelson (MD ’95, Res ’98, Flw ’00), clinical professor of Medicine, and now directed by Corey Romesser, MD (Res ’06, Flw ’07), associate professor of Clinical Medicine, screens patients with fractures for specific age-related surgical risks, such as medication interactions or delirium. Patients have beds in the orthopaedics unit, where staff are trained in geriatrics care, and are fast-tracked to surgery (within 24 hours of admission). They have fewer complications, such as pneumonia, and are up and walking sooner.

Robert McCann, MD

In addition to designing a better way to treat fractures in older people, the center has spawned a journal and several dozen publications. Doctors in the center have traveled to at least 30 countries to share their knowledge and methodology. They are developing a national teaching program to expand these and a database documenting treatment and outcomes around the country.

Daniel Mendelson, MD, cares for a patient in Highland Hospital’s Geriatric Fracture Center.

“That’s something you can do in a community hospital with connections to an academic medical center. It’s a really great example of optimal care,” says geriatrician Robert McCann, MD, former chief of Medicine at Highland and CEO of Accountable Health Partners, URMC’s clinically integrated network of hospitals and physicians. In 2017, the Geriatric Fracture Center at Strong Memorial Hospital was launched as a model of co-management among hospital medicine, geriatrics, and orthopaedic surgery. Directed by Jenny Shen, MD (Res ’13), assistant professor of Medicine, this fracture center models the original Highland Hospital-based center—with equally successful patient care metrics and outcomes. “Sharing best practices among our own providers and other Age-Friendly Health System (AFHS) institutions will result in the best, most consistent care possible.” The Geriatric Fracture Center is just one of dozens of programs in the UR Aging Institute’s (URAI) Vital Care pillar. Guided by the AFHS model, together they focus on education and multidisciplinary patient care. The Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (Project ECHO®), a video-based mentoring model, reduces health disparities by bringing specialist expertise to frontline staff who work in underserved communities. Under the leadership of Michael Hasselberg (MS ’07, PhD ’13), and Elizabeth (E.J.) Santos, MD (BA ‘94, Flw ‘06, MPH ‘13), URMC chief digital officer, the University of Rochester launched Project ECHO® Geriatric Mental Health, targeting primary care offices throughout New York state. This model was soon extended to more than 100 nursing homes throughout the Greater Rochester region and the state to improve geriatric behavioral health and successfully reduce the use of psychotropic medications in nursing homes. That sparked creation of a full geriatric telepsychiatry program to support multidisciplinary teams working in nursing homes and rural hospitals.

Educating the professional workforce, current and former fellows and program leaders from the divisions of Geriatric Medicine and Psychiatry include, from left: Fatima Hafizi, MD; Thomas Caprio, MD; EJ Santos, MD, MPH; Lisa Vargish, MD; Brigid O’Gorman, MD; Naveen Silva, MD; Sindhu Kadambi, MD; Jennifer Muniak, MD; John Seymour, MD; Kate McBride, MD; Jacqueline Quezada, MD; and Adam Simning, MD.

Learning Curve

Workforce education creates channels for spreading best practices and care models for older adults in hospitals, nursing homes, and clinics. Disciplines come together to research and treat conditions in a way that is tailored to the needs of older patients. A spirit of creativity and curiosity is essential for this kind of collaboration to thrive, but that rarely pops up out of nowhere. Layered underneath is an educated workforce, which brings people together in a united cause. Having staff with the knowledge and skills to care for an aging population is nothing short of a system transformation—and long overdue, says geriatrician Thomas Caprio, MD (Res ’03, Flw ’05, MPH ’10, MS ‘15). Caprio is principal investigator of the University of Rochester Geriatric Workforce Enhancement Program (GWEP), now in its second round of funding with a $3.7 million grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) to support URMC’s Finger Lakes Geriatric Education Center, which Caprio directs. “There aren’t enough geriatricians in the country,” Caprio says. “We’re pushing out the appropriate education and training across all professionals so they are sensitized to the unique challenges and risks of older adults, so they can provide the best care possible. It’s sort of geriatricizing the health care system.”

-Rosanne Leipzig

Jenny Shen, MD (center), consults with Physical Therapist Matthew Humphrey and Nurse Manager Meghan Flanagan in the Geriatric Fracture Unit at Strong Memorial Hospital.

Training is for all kinds of health care professionals, and they learn together in an interprofessional approach—from physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists to therapists, dietitians, and students of all disciplines. Issues discussed relate to the Four Ms of the AFHS (see page 19), addressing everything from cognitive changes and loneliness to medication and advanced-care planning. The workforce enhancement grant also funds training to help age-focused nonprofits and primary care practices diagnose dementia and other cognitive conditions. And spurred by the pandemic, online and videoconference trainings have exploded, reaching more than 15,000 professionals across the state and nation.

The GWEP grant was the first in the state to use Project ECHO® for geriatric training. In this case, it links URMC geriatrics specialists with doctors, nurses, social workers, pharmacists, and others at 60 nursing homes in the Finger Lakes region. Sessions cover geriatric behavioral health, the AFHS, and quality improvement and patient safety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The School of Medicine and Dentistry is one of very few that emphasize an aging curriculum from the first year to fellowship, and it is even taught to undergraduates. Its foundation is in the biopsychosocial model, which treats the person and not just the disease. An integrated aging theme instilled geriatrics into all four years of the undergraduate medical curriculum and is replicated nationally. Students continue with early exposure to older adults in clinics, hospitals, and nursing homes to battle ageism and ensure competency in nationally established geriatrics training benchmarks. “On Day One of medical school, 100 students listened attentively as a geriatrician sat down with a geriatric patient and showed us how to talk to an older patient,” recalls

Heather Hopkins

Gil (MD ’12, Res ’15, Flw ’16), a Heather Hopkins Gil, MD geriatrician and palliative medicine physician at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Rochester’s training for geriatrics is integrated so well that you do not always realize you’re learning fundamental geriatric medicine,” she adds. “This is critical because the majority of patients admitted to hospitals or facing serious illness are older or frail.” Groundbreaking geriatrics educator

Rosanne Leipzig, MD, PhD

(Res ’82), vice chair for Education in the Department of Geriatrics and Palliative Medicine at Mount Sinai’s Icahn School of Medicine, Rosanne Leipzig, MD says her Rochester geriatrics residency training pushed her to be the best clinician possible. “All medical residents spent at least six weeks at Monroe Community Hospital, and with T. Franklin Williams,” she says. “UR geriatrics has developed an excellent national reputation. Many of the most well-known geriatricians have trained there.”

The Beauty of Co-Management

The Geriatric Fracture Center is a geriatric co-management model at URMC that has been replicated around the world to improve patient outcomes in a cost-effective way. It’s the kind of thing the UR Aging Institute (URAI) is ideally suited to help foster. Others include Geriatric Trauma Surgery at Strong, led by Ciandra D’souza, MD, MPH, assistant professor of Medicine; and Geriatric Oncology at Highland, led by Corey Romesser, MD (Res ’06, Flw ’07), associate professor of Clinical Medicine.