Osmosis Science Magazine

Fall 2021 Edition

Cover Design by Josie

Osmosis Science Magazine

Fall 2021 Edition

Cover Design by Josie

By Dusan Vukcevic

What if there was a creature that is so indecisive about its habitat, that it decides to live both in rainforests and in the Antarctic? What if this creature was taking a swim in the Mariana Trench, and warming itself up at the bottom of a mud volcano? Their appearance gave them many names, so today we call them water bears, moss piglets or simply, Tardigrades. Be that as it may, the number of their names is negligible compared to the number of harsh conditions they are able to withstand. Just how resilient are these creatures?

You can throw them into the vacuum of space, or shoot them out of a gun. Don’t serve them water for 10 years, expose them to temperatures as cold as an absolute zero or as hot as 151℃ (when we discover a way to break the Third Law of Thermodynamics, of course). Blast any form of radiation that is a 1000 times stronger than what humans could withstand. Squeeze them at 6000 times atmospheric pressure, or hit them with a 1.14 gigapascal shock You might think to yourself 1 now, well, we can always expose them to a certain type of toxins. And… You are wrong again. As for now, not even toxins would work if you decided to get rid of these tiny, adorable, completely-not-like-an-actual-bear bears. So, where did these creatures come from?

Sadly, we don’t know much about their history, or how they have developed over time. Unlike other ancient creatures that we

have managed to preserve in museums and laboratories all around the world, there are only 3 fossils of tardigrades in the possession of humans. The oldest one is about 78 million years old and is peacefully stored at Harvard. But, on the 5th of October 2021, completely by accident, a new one was found preserved in amber. This piece of amber dates back to the Miocene epoch, 23 million to 5.3 million years ago, and was found in the Dominican Republic. Now, this moss piglet can join the glorious tree of life of tardigrades, together with its two known-species cousins, and one, still not known by its species, discovered in West Siberia. What are the odds that after trying to find ants for months in a dime-sized piece of amber, you suddenly discover this prehistoric little creature, floating together with a beetle, and a flower Apparently, 2 someone was having a productive day in that lab.

The first-ever tardigrade discovered was in 1773. Being so small and harmless, people decided to store them in a drawer and not talk too much about them for quite some time. Nevertheless, in the past couple of years, the scientific community, myself included, has started to read, write, and think about Tardigrades a lot more. If you go and look them up on the internet, you would see an exponential increase in the number of scientific publications focusing on all sorts of things regarding Tardigrades. What is an undeniably eye-catching fact is the way they walk. Yes, the walk. And to be honest, they do it without a flaw (Ahem, for all of us clumsy tall people who trip over a flat surface out there). They have a completely regular gait that looks surprisingly similar to one of larger animals. If your mind is not blown yet, not only are they amazing at their model runway walk, but Tardigrades are one the smallest known animals that even have legs at all! When tested on different surfaces, they were not forced to do anything. Rather, they were just chilling and strolling around the substrate, or perhaps they would see something interesting and run for it 3

Determination is the key to success, which even Tardigrades know by now. Whether this

References

1 “Tardigrades ” American Scientist, February 2, 2018

2 Lanese, Nicoletta “Tardigrade Trapped in Amber Is a Never-before-Seen Species.” LiveScience. Purch, October 5, 2021

walking technique is something that makes them someone’s common ancestor or they just developed it for themselves is yet to be discovered.

As the chronicle of Tardigrades is escalating in a matter of days, we are waiting to see more amazing things they can do, and conditions they can resist. Meanwhile, the scientists will keep firing them from a gun at 825 m/s and sending them into space together with baby bobtail squids to test biological survival inside the infinite dark void. One day, hopefully, their DNA might be a primer to synthesize Dsup proteins (that these water bears, of course, already own) for humans, which will help to protect DNA from hydroxyl radicals. Not only are they endearing, harmless, and friendly, but they will also help us improve our own ability to survive in the future! Enough talking, we will make them blush, or shine blue in their case, and they won’t notice, because they only see

black and white Water bear, moss piglet, !4 Tardigrade, a truly inspiring creature, an ancient creature, a creature that has seen it all.

3 Bowler, Jacinta “This Is How Tardigrades Walk, and We Were Not Ready for the Footage ” ScienceAlert, August 31, 2021

4 “Tardigrades' Latest Superpower: A Fluorescent Protective Shield.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, October 13, 2020

path, but through our collective efforts, humanity fought back, pushing them to the brink of oblivion. But did we truly win? Little did we know, they continued to grow stronger among us, lying dormant… until now.

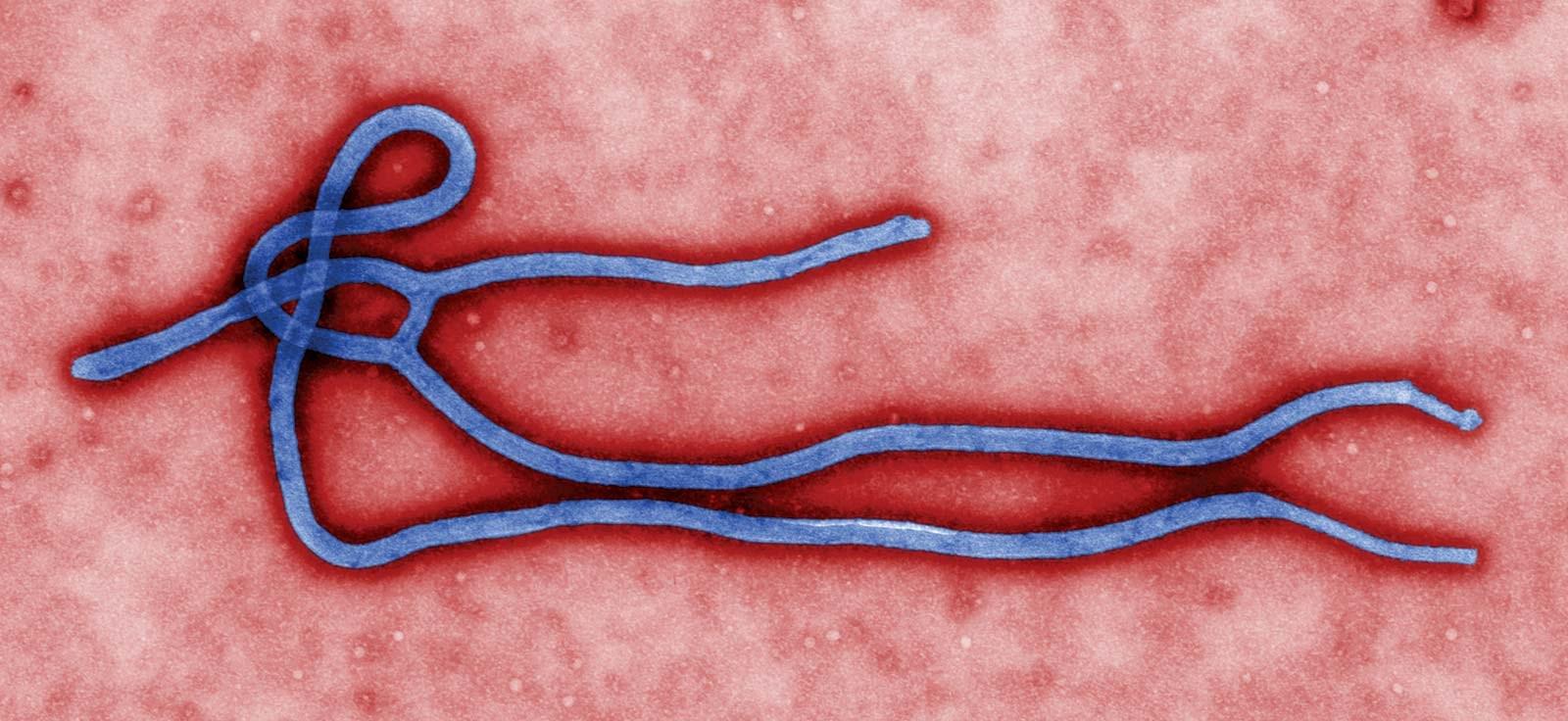

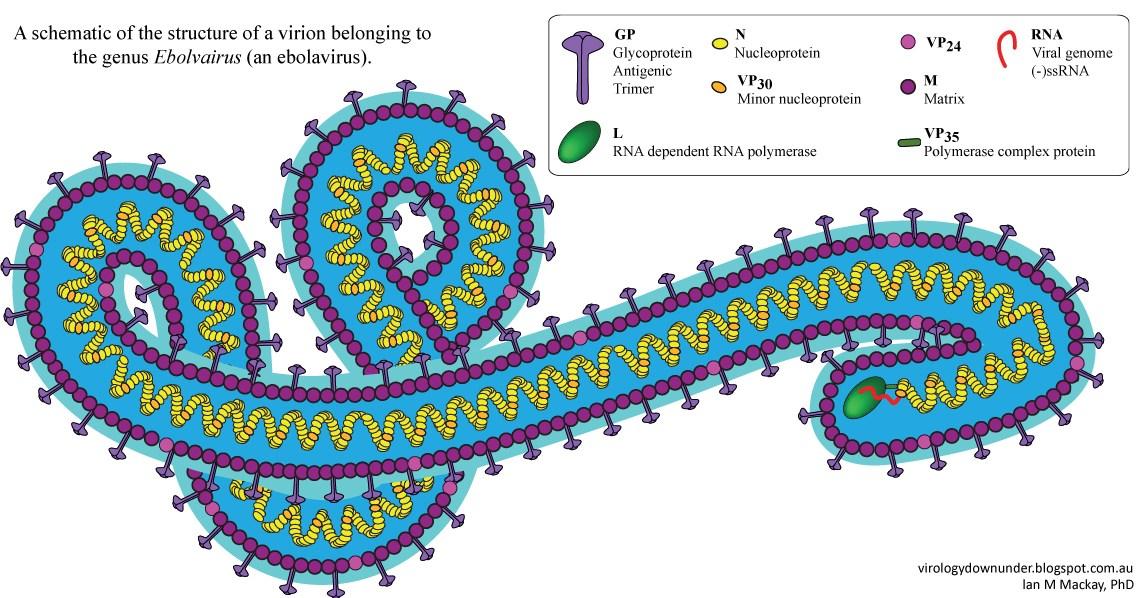

You’ve probably heard similar narration in trailers for movies about alien invasions, but what if I told you a threat was already here. Not in the form of aliens, of course, but something that seems just as foreign to most of us: viruses.To the naked eye, these mysterious particles are invisible, but we know they exist.We can feel their effects when we wake up in the morning with a sore throat, when we hear someone coughing on the street, or when we are fatigued from a fever. Under high powered microscopes, we can see these strange creatures, with their spidery legs, spikey coats, or snake-like bodies.Viruses are obligate intracellular parasites that hijack our cells to reproduce, harming us in the process. In some cases, they can even lie silently within us, waiting for weeks or months before activating like some extra-terrestrial terror. We have long known that many viruses can remain latent in cells for extended periods of time. Many bacteriophages, for example, can undergo a lysogenic cycle, where their DNA is incorporated into a bacteria and remains dormant until some external signal triggers its activation. HIV and herpes viruses are known to enter a latent stage where they remain almost undetectable. In light of the

By Joshua Pandian

even deadlier virus may have a latent stage: the Ebola virus.

In 2014, theWest African country Guinea experienced a major outbreak of the Ebola virus disease (EVD) that ended in 2016. Patient zero is believed to be an 18-month old boy from a small village who received the virus from bats, a potential reservoir host.After spreading rapidly through rural areas, the virus made its way to major urban centers for the first time, significantly increasing the infection and death rates.1 In February 2021, seven years after the start of this outbreak, Guinea experienced a new endemic. In order to prevent the outbreak from being as severe as the previous one, public health officials needed to know the genomic composition of the virus. Information about the virus's genome was crucial to determine what types of treatments would be effective against it as well as to determine the vectors responsible for the new strain’s transmission.2

Using next generation sequencing techniques, researchers sequenced the genome of the 2021 Ebola virus and placed it on a phylogenetic tree to determine how related it was to similar Ebola viruses.The results showed that the genome of the 2021 Ebola virus was of the Zaire ebolavirus species, the same species responsible for the 2014 outbreak.This information was essential to creating a plan of action for treatments, but the second question remained unanswered: what was the vi-

rus’s host? This is where things become interesting. The researchers found that the genome of the virus surprisingly did not contain as many mutations as they had expected. Previous research has established the approximate rate that new mutations occur in the Ebola virus genome, and the researchers could use this data to determine how many mutations were expected to accumulate in the virus over the course of five years between endemics.The presence of significantly fewer mutations led researchers to believe that the virus had remained latent in a human host for the five years between outbreaks.This hypothesis was further supported by data showing key mutations that allowed the virus to jump from animals to humans in 2014 were still conserved in the 2021 virus. One such mutation was to a glycoprotein that allowed the virus to bind to human cells. Conservation of this mutation seems to indicate that the virus did not recently evolve to transmit from animals to humans, but rather it had previously evolved and remained latent in a human host.2

system. Cases of recurring symptoms in the brain and eyes of previously infected patients gives credence to this hypothesis.3

While current research has answered many questions about the Ebola virus, there are still many questions left unanswered. How does a latency period slow down mutation rates? How quickly can viruses like the Ebola virus transfer between species, and which species is the reservoir host for the virus? Is there ever a single reservoir host for these types of viruses, or can these viruses adapt to infect various species with minimal mutations? How long can the virus persist within a single species? Many of these questions can even be applied to coronaviruses, like COVID-19, another group of viruses that can easily adapt to infect many different host species.3 Especially in the face of a global pandemic, the many aspects of viruses that are still unknown can be discouraging. However, as studies like the one above show, by collecting and analyzing data, we can have a better understanding of the various interactions that occur between these infectious agents and their hosts, and we can learn how to better prevent their reproduction and transmission. The more we understand about these diseases, the less alien they become and the less we have to fear

rently, there is no definitive answer for this question, but there are various hypotheses, of which one suggests that the virus may hide in parts of the body that are not targeted as heavily by the immune system.These areas are said to be “immune privileged” and include the testes, eyes, and central nervous

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, March 8). 20142016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Centers for Disease Control and . Retrieved November 5, 2021, from https:// www.cdc.gov/vhf/ebola/history/2014-2016-outbreak/

2. Garry, R. F. (2021). Ebola virus can lie low and reactivate after years in human survivors. Nature, 597(7877), 478–480. https:// doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-02378-w.

3. Keita, A. K., Koundouno, F. R., Faye, M., Düx, A., Hinzmann, J., Diallo, H., Ayouba, A., Le Marcis, F., Soropogui, B., Ifono, K., Diagne, M. M., Sow, M. S., Bore, J. A., Calvignac-Spencer, S., Vidal, N., Camara, J., Keita, M. B., Renevey, A., Diallo, A., … Magassouba, N. F. (2021). Resurgence of ebola virus in 2021 in Guinea suggests a new paradigm for outbreaks. Nature, 597(7877), 539–543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03901-9 .

Jack DuPuy

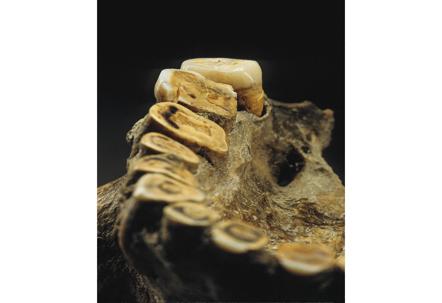

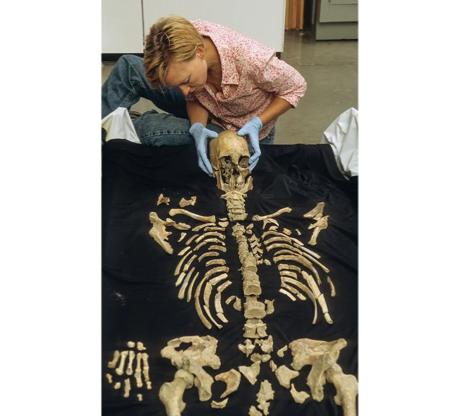

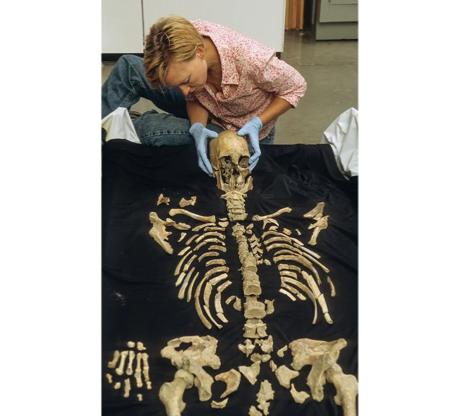

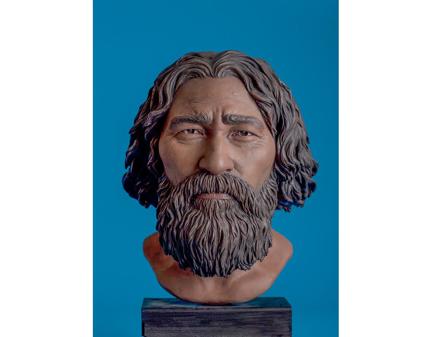

What would you do if you found a human skull on the banks of the James River? On July 28, 1996, two college students stumbled across a skull on the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington. They believed it was a murder victim at first, but archeologists and scientists discovered that the skull was part of a nearly complete, 9,000 year-old skeleton. Pelvic bones provided scientists with clear evidence that this skeleton was male, and they named him the Kennewick Man. Every major bone was recovered except for the sternum and a few bones in the hands and feet, making this prehistoric man one of the most intact skeletons ever discovered in the Americas.

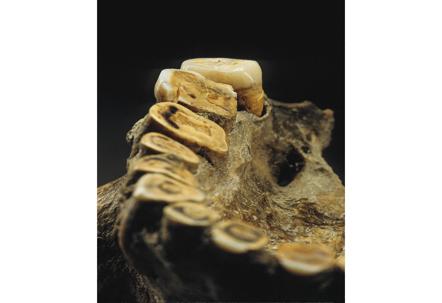

Soon after the discovery, Douglas Owsley and Kari Bruwelheide led a team of twenty-two scientists in examining the nearly 300 bones and fragments, and their first step was to meticulously lay out the skeleton, bone by bone, in a bed of sand1 These experts determined that the Kennewick Man was muscular, stocky, and right-handed, measuring at about 5 feet 7 inches tall and weighing about 160 pounds. Evidence from this man’s bones gave far greater insights into his life than his physical stature, however. Despite being buried 300 miles inland, chemical signatures locked into his bones (based on atomic variations of carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen) suggest that for the last twenty years of his life, he ate marine animals and drank cold glacier water that could only be found in Alaska at the time1 . Furthermore, his leg bones indicate that he often waded in shallow rapids, and he demonstrated bone growths consistent with a condition known as “surfer’s ear” that

results from frequent immersion in cold water1. All of this evidence suggests that despite his namesake, the Kennewick Man lived quite far from modern-day Kennewick, Washington, likely along a coastline farther north.

During their analysis, scientists discovered that the Kennewick Man picked up many injuries over the course of his life and determined that several of them resulted from consistent, intense spear throwing. Bone marks left behind by muscle attachments in his right arm and left leg resemble those of a baseball pitcher, and the repeated throwing motions that caused those marks also likely caused the fracture in his right shoulder joint as well as prevented five broken ribs on his right side from healing after he sustained a damaging blow to the chest1. The Kennewick Man’s most egregious injury was a spearpoint embedded in his right hip. It struck him at a downward angle of 29 degrees, probably during combat, when he was somewhere between 15 and 20 years old, and scientists concluded that he would have died if he was left alone with injury1. While scientists do not know his exact cause of death, they know that his injuries did not kill him, and therefore scientists believe that the people he lived with must have cared for him and nursed him back to health. More evidence of the familial nature of the Kennewick Man’s community exists his skeleton was found intact, and his position suggested he was intentionally buried in a grave. Scientists determined that the Kennewick Man was preserved laying on his back between two and three feet below the surface, and he had his hands by his side, his palms facing down, his feet angled outward,

his body parallel to the river, and his head pointing upstream1. This rare window into the prehistoric culture that Kennewick Man belonged to suggests that some North American tribes buried their dead as early as 9,000 years ago, a fact that archeologists were unaware of previously.

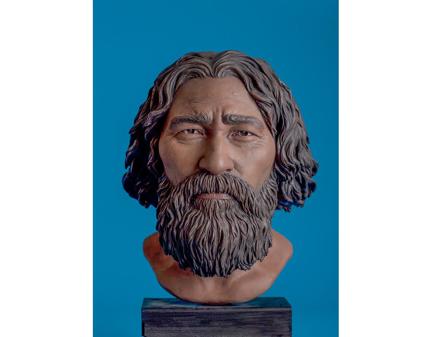

While they were able to continue conducting analysis using CT scans, the federal government gave scientists access to the actual bones of the Kennewick Man for just sixteen days in 2005 and 2006 due to controversies about his ancestry. Soon after his discovery, Native American groups claimed that Kennewick Man was their sacred ancestor and demanded that the government prevent scientific research from being conducted on the remains, but scientists were skeptical2. When archeologists first examined the skull (before carbon-dating proved the skeleton to be 9,000 years old), they believed it was a skeleton of an early European trapper, remarking that the skull lacked typical ancient Native American facial features such as an extended eyebrow ridge and lifted, protruding cheekbones1 . Then, Owsley created a three-dimensional reconstruction of the man’s face based on his skull that looked similar to the face of famous white actor Patrick Stewart3 Unfortunately, this white-washed depiction emboldened white supremacist groups to support their claim that Europeans were the first American settlers, but DNA evidence released in 2015 ultimately discredited this myth and cleared up confusion about the Kennewick Man’s

mysterious ancestry. This DNA analysis, specifically evidence from his Y-

chromosome and mitochondrial DNA, demonstrated that Kennewick Man is most closely related to Northern Native American tribes including the Ojibwa, the Algonquin, and the Colville tribe native to Washington4 . In 1990, the United States government passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act with the goal of rectifying ethical atrocities committed by museums and scientists against the remains of indigenous peoples, and DNA evidence confirming Kennewick Man’s Native American heritage placed his remains under this umbrella. Scientists reluctantly but respectfully returned the remains, and the Kennewick Man was privately reburied by his descendants along the Columbia River in 2017, bringing his fascinating story to a peaceful end.

References:

1- Preston, D. (2014, September). The Kennewick Man Finally Freed to Share His Secrets. Smithsonian Magazine.

2- Samuel Redman Assistant Professor of History. (2016, May 19). Kennewick Man will be reburied, but quandaries around human remains won't. The Conversation.

3- Egan, T. (1998, April 2). Old Skull Gets White Looks, Stirring Dispute. The New York Times.

4- Rasmussen, M., Sikora, M., Albrechtsen, A., Korneliussen, T. S., Moreno-Mayar, J. V., Poznik, G. D., Zollikofer, C., de León, M. P., Allentoft, M. E., Moltke, I., Jónsson, H., Valdiosera, C., Malhi, R. S., Orlando, L., Bustamante, C. D., Stafford, T. W., Jr, Meltzer, D. J., Nielsen, R., & Willerslev, E. (2015). The ancestry and affiliations of Kennewick Man. Nature, 523(7561), 455–458.

Isabel DiLandro

Chandra Thapar, an Indian anthropologist, dedicated a portion of his career to the study of foreign cultures and how they relate to his native country caught his specific attention due to its similarities in the reverence of a sacred animal, akin to how the cow is sacred to India. See below a short consolidation of his findings:

shod. There are rac specialists in each community, perhaps more than one if the community is particularly wealthy. These specialists demand costly offerings whenever a tribesman must treat his ailing rac.

The tribe Dr. Thapar studied is called the Asu and is found on the North American continent north of the Tarahumara of Mexico. Though it seems to be a highly developed society of its type, it has an overwhelming preoccupation with the care and feeding of the rac - an animal much like a bull in size, strength and temperament. In the Asu tribe, it is almost a social obligation to own at least one if not more racs. Ac. nyone not possessing at least one is held in low esteem by the community because he is too poor to maintain one of the beasts properly. Some members of the tribe, to display their wealth and prestige, even own herds of racs. At the age of sixteen in many Asu communities, youths undergo a puberty rite in which they must petition a high priest in a grand temple. He is then initiated into the ceremonies that surround the care of the rac and is permitted to keep a rac.

Unfortunately the rac breed is not very healthy and usually does not live more than five to seven years. Each family invests large sums of money each year to keep its rac healthy and

The rac has many habits which would be considered by other cultures as detrimental to the life of the society. In the first place the rac breed is increasing at a very rapid rate and the Asu tribesmen have given no thought to curbing the rac population. As a consequence the Asu must build more and more paths for rac to travel on since its delicate health and its love of racing other racs at high speeds necessitates that special areas be set aside for its use. The cost of smoothing the earth is too costly for any one individual to undertake, so it has become a community project and each tribesman must pay an annual tax to build new paths and maintain the old. There are so many paths needed that some people move their homes because the rac paths must be as straight as possible to keep the animal from injuring itself. Worst of all, the rac is prone to rampages in which it runs down anything in its path, much like stampeding cattle. Estimates are that the rac kills thousands of the Asu in a year. Despite the rac's high cost of its upkeep, the damage it does to the land, and its habit of destructive rampages, the Asu still regard it as being essential to the survival of their culture.

After returning back to India at the conclusion of his work, Dr. Thapar decided to conduct a survey of randomly selected participants to promote

discussion about his time with the Asu tribe. He decided on three questions. First, he asked if surveyors would want to own a rac to acquire social status. Second, he asked how they would evaluate the intellectual capacities of the Asu. Third, he hypothesized that the Asu had a democratic form of government and were able to legislate positive changes, and asked for participant’s personal recommendations. Those surveyed seemed to split into two general categories.

The first group sympathized with the Asu people but were still quite concerned about the danger they willingly placed themselves in. Many reported that they understood the significance of the animal but they, themselves, would not desire to own one. They mostly came to the collective consensus that while they were not necessarily intellectually inferior, the Asu tribe did not seem to possess the most rational mindset. Thirdly, suggestions were made to cut down on the rac population as they understood the weight of cultural significance they held to the tribe, but ultimately decided they were too dangerous in large numbers to be sensible.

The second group took a more extreme approach. They were adamant about the illogical and hazardous nature of racs and firmly believed that under no circumstances did the significance of this tradition outweigh the risks of owning a rac. Many confessed they did not think very highly of the tribe’s intelligence and, if they were given the opportunity, had no qualms about implementing a system to ban the

ownership of racs altogether for the safety of the people.

After reading the synopsis, you have formed some opinion about the Asu tribe and the position racs have within their society. However, this is a completely fabricated study. Now take a moment to reread the passage given to you with the perspective that the Asu tribe can, in actuality, be read as Usa when presented backwards. Likewise, the word rac instead reads as car.

If throughout your initial reading of this “study” you found yourself agreeing with group two and dismissed any arguments about cultural importance brought to attention by group one, you exhibit confirmation bias. This is a tendency to listen more attentively to opinions that favor your already developed beliefs. Confirmation bias can be rooted in conservation of mental processes that limits the need to make decisions and the protection of self-esteem. Confirmation bias can make us feel as though we are always universally accurate in our personal truths.

If your initial thought of discovering that the “study” was a ruse is to claim that you knew it was fake all along, that is a sign of hindsight bias3. In an old study, students were asked to predict if Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas would ultimately be confirmed. Prior to the results, 58% of students believed Thomas would be chosen. However, after Thomas was officially confirmed, 78% of the same students polled reported believing that this outcome would occur2. This

phenomenon of being able to somehow foresee even the most random events stems from our tendency to believe in our ability to view occurrences as “inevitable” and “misremember” previous conclusions. This overestimation of our foresight can often lead to individuals taking imprudent risks.

If your stance followed the argument of group two and then, when it was revealed to be a ploy, tried to rationalize that you were led to answer that way and in real life you would respect such cultural differences. This is an example of actor-observer bias3 . It is the attribution of personal actions to external influence. Another example of this bias might be blaming a failed test on the teacher for making the exam too difficult. On the other hand, those exhibiting actor-observer bias also attribute other’s actions to internal influence. Say, if observing another student fail that same test, one would conclude that it was a result of that student's own laziness. This leads to miscommunication and a proclivity to blame the opposing side.

Lastly, perceiving American cars as advanced and practical while deeming racs as unnecessary and dangerous can be accredited to the halo effect3. This is the inclination to base overall perception of something on initial impressions, otherwise known as the physical attractiveness stereotype. Often, foreign concepts are less appealing than familiarity. And what is familiar, or attractive, is more likely to be regarded as competent or “good”. This is an especially dangerous bias that affects many in various different aspects

of life such as finding a job or impacting social acceptance versus rejection. These examples are only a few of many. Bias affects all of us, influencing our choices and how we choose to interact with the surrounding world. By becoming aware of our bias, we are able to broaden our perspective and find more compassion in what we may not know or understand. And while perhaps it is impossible to eliminate all of our bias, recognizing its existence is the first step to forming the awareness that improves our functionality as a unique, collective society.

1- Thapar, C. (2002). The sacred rac. Sacred Rac.

2- Dietrich, D., & Olson, M. (1993). A demonstration of hindsight bias using the Thomas confirmation vote - Dorothee Dietrich, Matthew Olson, 1993. SAGE Journals.

3- Cherry, K. (2021). Types of cognitive biases that distort how you think. Verywell Mind.

I’m

late

a

by Caterina Erdas

Modern physics is my only class where half the students are consistently late. It’s not a forgivable one or two minutes late, but five to fifteen. I say this as a culprit myself; I slept in late on the third day of class and didn’t go. It’s ironic, considering we spend a good portion of lecture re-defining time.

“What is time?” Dr. Gilfoyle asked me on the first day of class. Of course, I was the person on the hot seat with three seconds to make an intelligent response for the first question of the semester. No time to create my own, thoughtful answer, so I confidently uttered the phrase one of my smart high school classmates once said: “It’s what a clock measures.”

“You’re right; that’s actually the perfect physicist answer! Time is periodic….” Luckily, my high school classmate with two cybernetic implants (not relevant, but interesting nonetheless) knew what he was talking about.

Modern physics is the beginning of the physics magic show.

After general physics weeds out all the premed biology majors who take it as a requirement, a small group of crazies decide to take modern physics. That is when the professor, excited to have gotten past physics boot camp, pulls back the curtain and reveals a century-old secret: special relativity.

Special relativity, a universal pattern Albert Einstein first translated into words and math, has two fundamental postulates that all its

conceptual and mathematical phenomena follow. First, Newton’s laws of physics are the same regardless of the position you are observing it from (if the observer is moving at a constant speed).1 Basically, if LeBron James dunks a basketball from where you are sitting, the spectator walking to their seat on the other side of the stadium will also see him make the hoop. Premise or postulate number one seems straightforward enough.

Second, the speed of light is always the same, 299 792 458 meters traveled in one second regardless of the position you are observing it from.1 Even if the observer is moving.

Imagine you hold a light bulb and a machine that can measure the speed of light. The lightbulb quickly flashes, sending a light pulse. The machine you hold reads 299 792 458 meters per second. A helpful physics assistant, the Flash, stands next to you and runs behind the light pulse at half the speed of light with his speed-measuring device. He also measures 299 792 458 meters per second.

Physicists have run multiple experiments to see if Einstein was correct, and they have proven his postulate two is true many times over.2 Flash will measure the same speed of light as you did. Pre-1900s laws of physics, which we consider common sense but actually come from Newton, would predict Flash measures half the speed of light. But, Einstein and experimental physicists tell us that the speed of light is the same regardless of whether the light bulb, the observer, or both are traveling at constant speed or stay at rest. Instead, time moves slower for Flash.

A moving clock measures time slower than a stationary one. This phenomenon is called time dilation. When we observe time in our normal, low-speed lives, the effect of time dilation is unnoticeable, so accepting time dilation as true is difficult. I have the proof for measuring time at speeds close to the speed of light, explained by my physics professors, but it’s heavy in geometry and algebra too long to include in this piece.

However, I can present a simple experiment that shows it is true. A muon is a type of particle that is like an unstable electron with a larger mass. After its creation, it quickly decays in 2.2 microseconds if it is not moving. But, scientists ramped up the speed of muons using particle accelerators to close to the speed of light and saw that it took muons 64.4 microseconds to decay.3

Time dilation is more than just a quirky physics trick; without accounting for it, GPS information coming from satellites, which quickly orbiting the Earth, to your phone would be inaccurate. Modern physics challenges our understanding of the universe in surprising ways. The relativistic behavior of time is only the first act of the mind-melting show that is modern physics.

References

1. Einstein, A., (1905). On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies. Annalen der Physik, 17:891.

2. Evenson, K.M., Wells, J.S., Petersen, F.R., Danielson, B.L., Day, G.W., Barger, R.L., & Hall, J.L. (1972). Speed of Light from Direct Frequency and Wave length Measurements of the Methane-Stabilized Laser. Physical Review Letters, 29, 1346-1349.

3. Bailey, J., Borer, K., Combley, F. et al. (1977). Measurements of relativistic time dilation for positive and negative muons in a circular orbit. Nature 268, 301–305.

by Franklin Wetmore

Weeks went by in which I didn’t address the blunt, gripping pain on my inner shin. Now, I was sitting on a paddleboard in the middle of a lake in Suffolk, Virginia. It was almost midnight and the air was cool and breezy. I pressed two fingers into the side of my tibia just to remind myself the shock was there. I feared for what I had done to myself.

The X-ray revealed what appeared to be a large bump on the bone, which could be one of two things: swelling of the tendons lining the inner part of the tibia or a formation of calcium over the injured area. Although I still don’t know which of these was the case until this day, I have a good feeling that it is the former, now that I know more about blood flow around our bones.

We were waist-deep into the 2019 Cross Country season, looking to make a run (pun intended) for the conference title. Suffice it to say Coach Lampert wasn’t happy to hear the bad news - I’m out for the rest of the season with a stress fracture. While I was intrigued by my own stupidity in not addressing the clear and apparent problem in my leg, the way in which my leg responded to being continually used while injured fascinated me more.

Similarly, researchers have only recently discovered how blood vessels, capillaries, bone marrow, and periosteal tissues fully interact, thus revealing to me the truth behind the swelling on my leg. Bone Marrow (BM) in particular is crucial to staying healthy. Located in the inner tunnels of

humans’ larger bones (spine, femur, ribs, etc.), BM is responsible for producing stem cells that create platelets, red blood cells, and white blood cells. Bone marrow failure can have a wide range of effects, from a weakened immune system to dysfunctional blood flow to the development of cancerous cells. Bone Marrow by its very nature needs to be vascular in order to transport disease-fighting substances, known as neutrophils, and to reach platelet-producing cells, known as megakaryocytes.

Why has it taken so long to uncover these?

Examining trans-cortical vessels requires certain types of electronic imaging which, despite major advancements in the medical industry, are relatively new to researchers. Previous studies done on this topic have been conclusive but not assuring on how all of this really works.

Scientists from the University Duisburg-Essen in Essen, Germany, conducted experiments on large murine (mice) bones to examine just how quickly neutrophils can be transported from the inner bone to external circulation. This is important in mammals as bone marrow houses white blood cells, and the quicker those cells are deployed, the quicker the body can heal itself. After injecting a stimulant called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) into the species, which stimulates the movement of these white blood cells, they noticed that it only took a few minutes for neutrophils to be detected in blood circulation outside of the

bone, indicating that the network of arterial and venous vessels is more extensive and activates quicker than initially assumed. After these observations, the researchers used light-sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) and X-ray microscopy to examine the trans-cortical vessels (TCVs) running along the long bones of the mice in the experiment, finding around 16 arterial vessels and hundreds of capillaries. These ran both along and perpendicular to the bones, from the inner (endosteal) to the outer (periosteal) portions.

The directions of the TCVs in a mouse bone were also illustrated, with perpendicular-running vessels towards the top of the bone having a slight downward angle, and the opposite being true for those towards the bottom of the bone. Most of the blood traveling to and from the bone marrow travels through TCVs, and thus the researchers have concluded that these vessels run from the very insides, drawing nutrients from the marrow to the periosteal regions and throughout the rest of the body.

So why has it taken so long to uncover these?

Examining trans-cortical vessels requires certain types of electronic imaging which, despite major advancements in the medical industry, are relatively new to researchers. Previous studies done on this topic have been conclusive but not assuring on how all of this really works.

However, with this newfound knowledge, scientists can do a number of things, like recognize earlier signs of arthritis, treat skeletal injuries more effectively, and improve bone marrow health. The use of new medical technology in this research is reminiscent of an ever-changing healthcare landscape leading to more effective strategies in providing care. These new discoveries will also be able to assist physicians such as orthopedic surgeons in their treatments and even virologists in their study of the body’s response to certain pathogens. I sure wish I had known about trans-cortical vessels when I was sitting on that paddleboard. Would have probably given me some security in understanding what was happening in my leg...I think?

References:

1. Grüneboom, A., Hawwari, I., Weidner, D. et al. A net work of trans-cortical capillaries as mainstay for blood circulation in long bones. Nat Metab 1, 236–250 (2019). A network of trans-cortical capil laries as mainstay for blood circulation in long bones.

By Isabel DiLandro

macrophages to reduce, so it just sits contained in the macrophage’s membrane until the macrophage dies and spills its contents. A new macrophage then scoops up this leftover ink, and the process begins again.

The answer is pretty simple: tattoos are not temporary. But why? How does the ink get there? How does it stay put? In order to understand this process a bit more, it is important to have a basic understanding of the skin’s structure and function.

Many often misattribute the permanence of tattoos to the location of ink in the skin: they believe that the ink is injected into a deep layer of the skin where the cells no longer die or regenerate, thus preventing the ink from falling out. While the depth of the ink application does play a role, this explanation for tattoo permanence is not entirely accurate. In order to understand the problems with this misconception, we need to have a basic understanding of the skin’s structure and function. The skin is the body’s largest organ, primarily serving as the first barrier of protection between the environment and an organism. There are three main layers that make up the skin: the epidermis, dermis, and hypodermis.

The epidermis, or the thinnest outermost layer, maintains homeostasis, while the dermis, a much thicker layer underneath the epidermis, provides cushion and plays a valuable role in healing wounds. The last layer, the hypodermis, is composed mostly of fat and provides insulation. The epidermis is constantly replacing itself, usually fully regenerating every 27 days, so a tattoo located on this layer would fully disappear in the course of an average month. In order to make tattoos permanent, the ink must be injected into the dermis instead. No wonder that butterfly face paint you got as a kid came out in the bath!

How does a tattoo artist’s needle get the ink into the dermis? Many often imagine a tattoo needle as a ballpoint pen that stores ink within it and injects it into the skin. However, in reality, the fluid does not sit within the needle, but on top of it, like a fountain pen. So, instead of thinking of a needle injecting the dermis with ink, think of the dermis absorbing the ink sitting on the top of the needle - much like a paper towel absorbing water.

While the dermis lies deep below the surface of the skin, it is not the depth of the ink, but ultimately the body’s immune system that contributes to tattoo permanence. By repeatedly perforating the skin, the tattoo needles cause irritation and damage to the skin tissue, which causes white blood cells in the dermis, known as macrophages, to trigger an immune response. These macrophages attempt to scoop up and break down foreign debris in the affected area until it is healthy again. However, tattoo ink is too large for the

While tattoos are permanent, one’s thoughts and opinions are always changing. As a result, many often decide they would like to have a tattoo removed. During a tattoo removal, a laser set to a specific wavelength is directed at the ink. Different colors of ink absorb different wavelengths of light. As soon as this light is absorbed, the ink is dispersed into smaller particles, which are small enough for the macrophages to successfully dispel. While lasers can be used to remove a permanent tattoo, it is important to note that this is a lengthy and painful process - not always a quick, guaranteed fix.

The biology of humans is exquisite and complex. Tattoos highlight that beauty behind our intricate orientation. College is a time for experimentation and exploration. No longer are we children with faded infinity signs drawn on in sharpie. It is a new stage in life filled with freedom defining oneself while stepping into adulthood. What better way to commemorate the occasion than with a tattoo?

References

1. Contributor, N. T. (2019, November 25). Skin 1: The structure and functions of the skin. Nursing Times. Retrieved November 2, 2021, from https:// www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/dermatology/skin-1-the-struc ture-and-functions-of-the-skin-25-11-2019

2. Feltman | Published Mar 7, R. (2018, March 7). Tattoos are permanent, but the science behind them just shifted. Popular Science. Retrieved Novem ber 2, 2021, from https://www.popsci.com/how-tattoos-work/.

3. Gardner, S. (2021, March 9). Laser tattoo removal procedure, benefits, and risks. WebMD. Retrieved November 2, 2021, from https://www.webmd. com/skin-problems-and-treatments/laser-tattoo-removal.

By Rachel Decker

Imagine living with another organism in your body, cohabiting for months before you are even aware of its presence. Slowly, a lesion starts to form on your leg. The lesion grows bigger everyday, starting at a couple millimeters but growing up to a couple centimeters. The burning sensation starts with the lesion and can only be dimmed by submerging your leg in water. Suddenly, a worm emerges from the lesion along with pus and blood. The patient is infected with Guinea Worm Disease.

Guinea Worm Disease mainly affects rural parts of Africa and is caused by the parasitic roundworm Dracunculus medinensis. People get infected with the parasite when they drink water containing fleas that have been infected with the parasite’s larvae. The flea goes through the digestive system where it is dissolved by stomach acid and the larvae are released. There the lavare travels through the intestinal wall and develops in the abdominal body. The worm grows to full size then travels to the legs This process 1

typically lasts for 10-14 months. Only the female worm survives for this long as they have a longer lifespan than male worms. Once the parasite reaches sexual maturity, it pushes itself out of the body. At this point, the worm is approximately 60-100 cm long. The host cannot feel anything until the lesion starts to form where the worm is gathering. While the lesion is forming and before the worm bursts through the lesion, the host can develop a fever and become nauseous.

No vaccine or medication exists to stop a D. medinensis infection. The only thing that can be done is making sure the whole worm is removed. If a piece of the worm is left in the body, the wound will not close. Someone has to twist the worm around a stick to remove it without breaking it. This painful process could take weeks. After it’s removed, the worm has to be disposed of carefully or else it could enter a body of water, deposit their lavare, and start the cycle over again. After the entire worm leaves the body, which is

confirmed by the tail end, an open wound is left vulnerable to infection. Guinea Worm Disease is rarely fatal, but subsequent infections from the hole left by the worm are deadly.

Since there is no cure for the parasite to date, focusing on management and prevention is the only way to stop the disease from spreading. Roughly 1% of cases will die from infection Management includes contact tracing,asking infected patients which bodies of water they recently drank out of and who else drank there, and extensive monitoring of active cases to ensure the whole worm is removed. Preventative public health measures include bringing access to filtered drinking water, keeping public water supplies clean, and educating people about the parasite and

controlling infections from animals. 2 Originally, it was believed that parasites could only infect humans by water, but there has been a recent uptick in infections from animals with the parasite. Dogs make up an overwhelming number of animal cases but it is also known that cats and baboons have been infected with the parasite. Currently, there are more animal cases than human cases As long as the . 3 animals are getting infected and the worms are continuing the cycle and laying their

References

1. Greenway, C. (2004). Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm Disease). Canadian Medical Association Journal, 170(4), 495-500

2 Cairncross, S , Muller, R , & Zagria, N (2002) Dracunculiasis (Guinea Worm Disease) and the Eradication Initiative. American Society for Microbiology, 15(2), 223-246 doi:10 1128/CMR 15 2 223-246 2002

larvae in water sources, humans will continue to get sick. The Guinea Worm Disease can render a person immobile for extended periods of time and affect their lives. Combined with the weeks of getting the worm out and with healing from painful, open wounds , people can miss months of work. The reproductive peak of D. medinensis coincides with the peak of agricultural business in rural Africa too, resulting in a sharp decrease in agricultural activity and a sharp increase in economic

hardship It is predicted by the World . 1 Bank that the economic return on the continual efforts of eradicating the disease is 29% per year.

Thanks to President Carter’s passion project, a world with no Guinea Worm disease is possible and may be in the near future . In 1986, he created the Guinea Worm Eradication Program through his charitable organization the Carter Center. Thanks to the Carter Center, World Health Organization and the CDC, Guinea Worm Disease is on track to become the second disease ever eradicated after smallpox, but also the first parasitic disease and the first disease without a vaccine. When the program was first founded, there were 3.5 million cases. In 2020, there were 27 cases.

3 Boyce, M R , Carlin, E P , Schermerhorn, J , & Standley, C J (2020) A One Health Approach forGuineaWorm DiseaseControl:ScopeandOpportunities Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 5(4),159 doi:103390/tropicalmed5040159

By Ryan Cvelbar

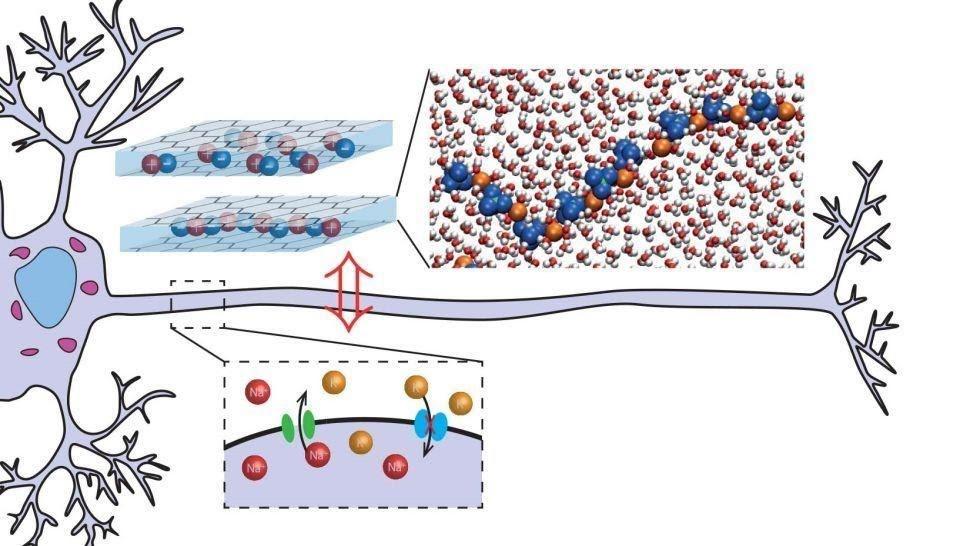

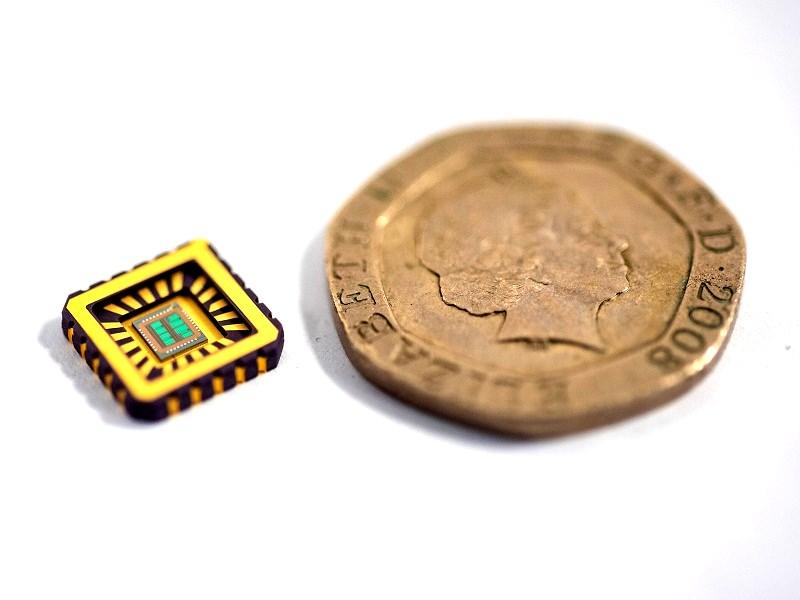

Every year another iPhone comes out with little more than an improved camera and some different colors to choose from. These improvements pale in comparison to the invention of the internet or telephone, two technologies that changed how the world operates. Has the technology industry hit an innovation roadblock? It seems to be the case with Apple as their most backordered new product is a $19 screen cloth6 . One source believes that the future of the technology industry is in AI stating, “by 2030 AI could elevate global GDP 14% from $14 to $15 trillion”5. However, finding the key to achieving optimal AI efficiency while minimizing energy requirements has proven to be quite the challenge. Dr. Paul Robin and his team hypothesize that computers are less efficient because they use electrons instead of ions to function and propose that artificial neurons may be central to advancing AI. A breakthrough this year by Dr. Robin and colleagues has provided a new perspective through which developers can think about AI. This new perspective has been derived from something we are all too familiar with, our brain. The Paris-based team of scientists showed that mimicking neuron ion gradients may be the key to jumpstart AI’s enhancement. A neuron is a specialized cell that is a part of the nervous system and it is connected to billions of other neurons throughout our body. The purpose of a neuron is to receive and transmit electrical signals throughout the body, instructing the body what to do.

Each neuron receives signals at one end of the cell, called the dendrite, and transmits signals at the other end, called the synapse. When a signal is transmitted from one neuron, the signal is received at the dendrites of the neuron and then an action potential travels down the axon of the neuron to the end of the neuron where the signal induces the release of neurotransmitters in the synapse. This either passes the signal to another neuron or induces some action within the body, whether that be the release of hormones by an endocrine gland or the contraction of our cardiac muscle. The entire basis of neuron activity depends on ion gradients within the neuron’s axon. Instead of using electrons to carry electrical signals in a computer, scientists

created artificial neurons with ion gradients to do the same thing. Dr. Paul Robin and colleagues have cited recent advances in nanofluidics enabling the confinement of water in a single molecular layer as a crucial factor in facilitating this energy efficient design. Nanofluidics is the study of fluids confined to structures of a nanome-

ter in size. According to Robin, the prototype of the artificial neuron is made of graphene slits that sandwich a single layer of water molecules and ions. Evidently, this model reproduced the Hodgkin-Huxley model of action potential initiation and propagation in a neuron and spontaneous voltage spikes indicative of neuromorphic activity. This proves that the artificial neuron model acts like a real neuron in the most basic sense.

The significance of this artificial neuron is that it has the potential to make AI

more energy efficient. Dr. Paul Robin points out that, The human brain needs only 20 watts to function, essentially as much as a light bulb, but computers need much more energy”2. Although it sounds unrealistic that some graphene slits and water could be so revolutionary, this breakthrough could result in computers that work more like the human brain than any

other AI algorithm has previously achieved. The next step in this research is to develop the artificial synapse that connects these artificial neurons and transmits electrical signals from one neuron to the next. Scientists imagine that this mechanism could serve to develop energy efficient computers that simulate brain function that can be studied to improve our understanding of how the brain processes information.

References

1. Bergan, Brad. “Scientists Created an Artificial Neuron That Actually Retains Electronic Memories.” Interesting Engineering, Interesting Engineering, 7 Aug. 2021, https:// interestingengineering.com/artificial-neuron-retainselectronic-memories.

2. Dhar, Payal. “These Super-Efficient, Artificial Neurons Do Not Use Electrons.” IEEE Spectrum, IEEE Spectrum, 3 Sept. 2021, https://spectrum.ieee.org/these-artificial-neurons-useions-rather-than-electrons.

3. https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5728-9189, Paul Robin, et al. “Modeling of Emergent Memory and Voltage Spiking in Ionic Transport through Angstrom-Scale Slits.” Science, 6 Aug. 2021, https://www.science.org/doi/full/10.1126/science.abf7923.

4. Mrt. “Study Suggests 'Memories' Can Be Stored in Synthetic Brain Cells.” Market Research Telecast, 10 Aug. 2021, https:// marketresearchtelecast.com/study-suggests-memories-can-be -stored-in-synthetic-brain-cells/125871/.

5. Newman, Daniel. “Ai-as-a-Service: The next Big Thing in Business Tech?” Talented Learning, 1 Sept. 2021, https:// talentedlearning.com/ai-as-a-service-next-big-thing-inbusiness-tech/.

6. Wakabayashi, Daisuke. “Apple's Most Back-Ordered New Product Is Not What You Expect.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 29 Oct. 2021, https:// www.nytimes.com/2021/10/29/technology/apple-polishingcloth.html?referringSource=articleShare.

Thank you to our awesome Osmosis team members!

Editors: Ryan Cvelbar, Rachel Decker, Lily Dickson, Israa Draz, Caterina Erdas, Ally Martinez, Joshua Pandian, Mikayla Quinn, Josie Scramlin, Yulia Shatalov

Design Team: Lily Dickson (chair), Israa Draz, Emily Lekas, Sonia Mecorapaj, Josie Scramlin, Mikayla Quinn, Avery Rothstein, Pamira Yanar

Advertising: Alex Robertson (chair), Andrew Cook, Lily Dickson, Israa Draz, Caterina Erdas

Like what you see? Apply today! urosmosis.com/jointeam