HANG GLIDING + PARAGLIDING + SPEEDFLYING WINTER 2023 Volume 53 #1 695 CENTS

6 50 Years of Supporting the Free Flight Community by Steve Pearson, USHPA President

From Idea to Origin 14

The path to creating skygear hub by Shane Perreco

2022 Highland Challenge 18

A race-to-goal mini-comp recap by Charles Allen Columbia 2022 24

Personal lessons and advancements in Valle del Cuaca by Angela Bickar, Ognjen Grujic, Benjamin Smith, & Joe Popper 2022 Global Rescue XRedRocks 34 by Gavin McClurg

42 2022

Tater Hill Open

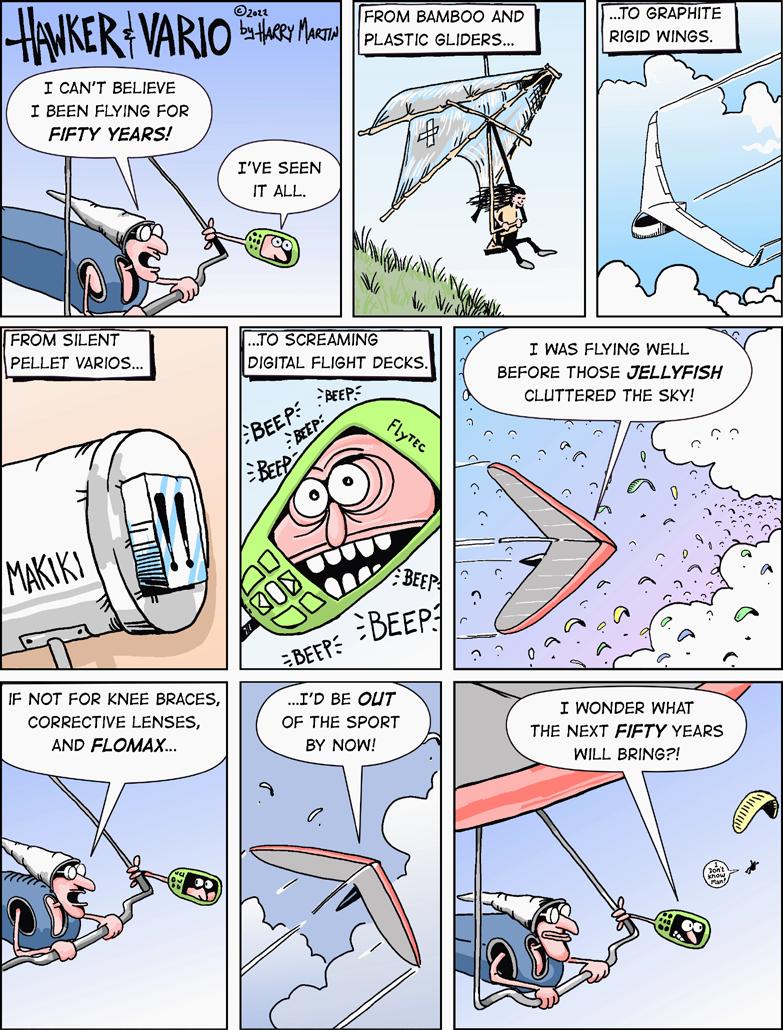

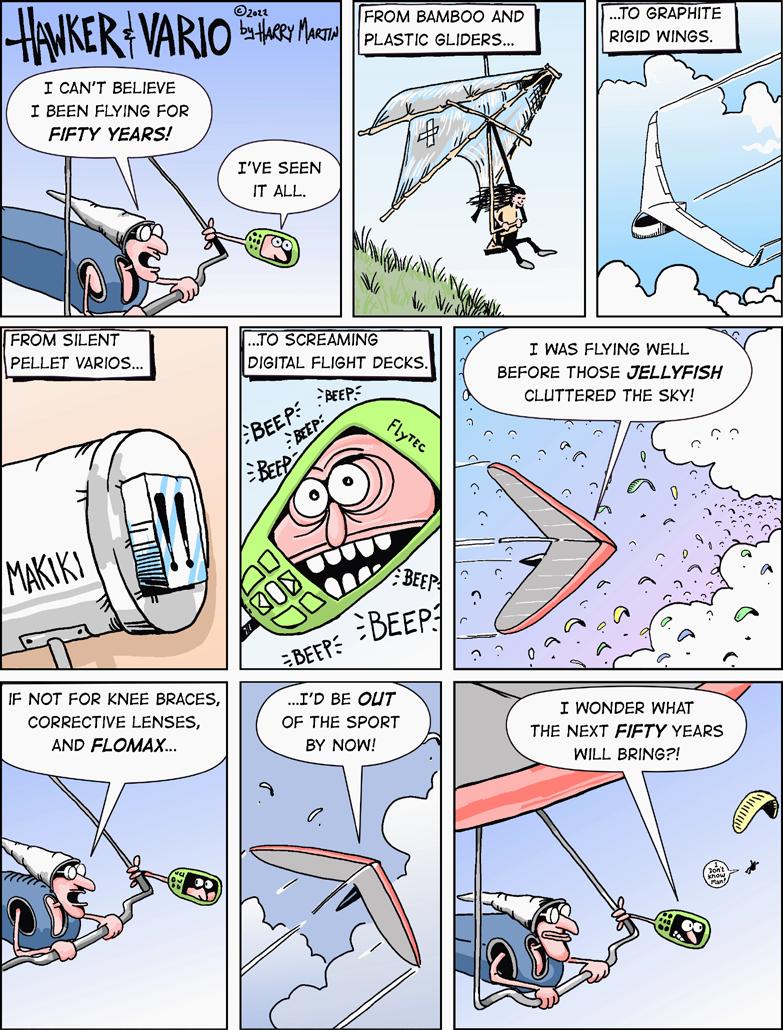

Part 1: Paying better attention to changing conditions by Bubba Goodman Part 2: Cloud suck really sucks by Tony Davis 52 Flying in Wind part 2: Handling Headwinds by Dennis Pagen 56 Flight Testing Lilienthal's Experimental by Markus Raffel 66 Hawker & Vario by Harry Martin

HANG GLIDING AND PARAGLIDING ARE INHERENTLY DANGEROUS ACTIVITIES

USHPA recommends pilots complete a pilot training program under the direct supervision of a USHPA-certified instructor, using equipment suitable for your level of experience. Many of the articles and photographs in the magazine depict advanced maneuvers being performed by experienced, or expert, pilots. These maneuvers should not be attempted without the prerequisite instruction and experience.

POSTMASTER USHPA Pilot ISSN 2689-6052 (USPS 17970) is published bimonthly by the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, Inc., 1685 W. Uintah St., Colorado Springs, CO, 80904 Phone: (719) 632-8300 Fax: (719) 632-6417 Periodicals Postage Paid in Colorado Springs and additional mailing offices. Send change of address to: USHPA, PO Box 1330, Colorado Springs, CO, 80901-1330. Canadian Return Address: DP Global Mail, 4960-2 Walker Road, Windsor, ON N9A 6J3.

SUBMISSIONS

from our members and readers are welcome.

All articles, artwork, photographs as well as ideas for articles, artwork and photographs are submitted pursuant to and are subject to the USHPA Contributor's Agreement, a copy of which can be obtained from the USHPA by emailing the editor at editor@ushpa.org or online at www.ushpa.org. We are always looking for great articles, photography and news. Your contributions are appreciated.

ADVERTISING is subject to the USHPA Advertising Policy. Obtain a copy by emailing advertising@ushpa.org.

©2023 US HANG GLIDING & PARAGLIDING ASSOC., INC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of USHPA.

4 USHPA PILOT

For

info@ushpa.org WINTER 2023 Ratings > 60 Calendar > 65 Classifieds > 65

change of address or other USHPA business +1 (719) 632-8300

USHPA PILOT 5 Reliable Paragliding Equipment advance.swiss Start a New Era HIGH-B PARAGLIDER EFFICIENT PERFORMANCE FROM 3.75 KG* The new IOTA DLS is a high performance XC specialist. Perfectly balanced pitch behaviour and effective C-handle control provide maximum flight comfort. Manufactured with our DLS technology, it offers you both robustness and durability at the usual high level. *Size 21 with optional light risers Distributor: superflyinc.com, info@superflyinc.com, 801-255-9595

Photo: Adi Geisegger

FALL BOARD MEETING

Sept 23-24 | Richfield, UT

USHPA is excited to host the Annual Board of Directors meeting in Richfield, UT before the Red Rocks Fly-in. Please visit the website for updates. ushpa.org/boardmeeting

CELEBRATION > Steve Pearson, USHPA President

50 Years of USHPA Supporting the Free Flight Community

: In December 1973, members of the Southern California Hang Glider Association voted to change the association’s name to the United States Hang Gliding Association, Inc.

Do you have questions about USHPA policies, programs, or other areas?

EMAIL US AT: info@ushpa.org Let us know what questions or topics you’d like to hear about!

Interested in a more active role supporting our national organization? USHPA needs you! Have a skill or interest and some time available?

VOLUNTEER! ushpa.org/volunteer

Hang gliding was a new and unique sport at the time. Stories about the sport were featured in many national publications, including National Geographic, Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, The Smithsonian, Popular Mechanics, and Mechanics Illustrated. In 1973, membership was already at 4,578 pilots, and competitions typically included hundreds of spectators and occasionally TV coverage. Chris Wills, age 21, had recently won the first National Hang Gliding Championships sponsored by Annie Green Springs Wine and was featured in Sports Illustrated. Membership more than doubled in the following seven months, totaling 10,410 pilots in July 1974— more than USHPA’s current membership.

I followed all of this in real time. I built my first glider at age 16 in late 1972, derived from plans in another publication, Low & Slow, but had to wait until my next visit to Southern California in 1974 to complete my flight training. Three years

later, on June 24, 1977, two days after my 21st birthday, my friend and hang gliding icon Bob Wills was tragically killed while filming a Jeep commercial. In the following months, Rob Kells, Mike and Linda Meier, and I took over the management of Bob’s company, Wills Wing. The business closed in 2021 after producing 29,368 gliders (not including our paragliders).

Fifteen major U.S. hang gliding manufacturers had one or more full-page ads in the June 1977 issue of this publication (then still titled Ground Skimmer), including eight from Southern California. Most had closed before ten more years elapsed; however, each had a rich history and made significant contributions to our sport and community. People like Pete Brock, designer of the Shelby Daytona Cobra Coupe (1965), left at the peak of his career to start Ultralight Products (UP). Pete recruited teenage designer Roy Haggard who, among many other achievements, later designed the UP Comet. Piloting a UP Comet II, Larry Tudor become the first pilot to break the 200-mile mark when he flew 221.5 miles on July 13, 1983, just 10 years after UP’s first standard Rogallo. Larry broke the next bar-

The United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association Inc. (USHPA) is an air sports organization affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA), which is the official representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), of the world governing body for sport aviation. The NAA, which represents the United States at FAI meetings, has delegated to the USHPA supervision of FAI-related hang gliding and paragliding activities such as record attempts and competition sanctions. The United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, a division of the National Aeronautic Association, is a representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale in the United States.

6 USHPA PILOT

rier just seven years later with a 303-mile distance and declared goal on July 3, 1990, on a Wills Wing HP AT 158 (now hanging in a museum in Elkhart, Kansas). Larry often talked with me about the 500-mile barrier, but Dustin Martin’s 2012 record of 475 miles will be tough to beat.

However, hang gliding began long before 1973 and the formation of USHGA. It’s controversial even to identify an origin with so many contributors from Dickenson (1963), Miller (1963), Palmer (1961), Rogallo (1948 and later), Bates (1908), Chanute (1896), Lilienthal (1891) and other dreamers of flight like Leonardo Da Vinci from history. Even my uncle built and flew a Bates-type “hang glider” as a teenager in 1927. Despite these numerous milestones, many recognize May 23, 1971, as the beginning of our era, on the day of the Otto Lilienthal Hang Glider Meet commemorating Otto Lilienthal’s 123rd birthday. As Frank Colver recounted, on the morning of the meet, “More hang gliders and hang gliding enthusiasts than anyone had even guessed existed showed up.”

That event catalyzed the Southern California Hang Glider Association (SCHGA) meetings, which regularly included people like Paul McCready (TIME magazine’s

engineer of the century and inventor of S2F theory) and Irv Culver (legendary Lockheed aerodynamicist). Ground Skimmer (later to become Hang Gliding Magazine, then Hang Gliding and Paragliding, and now USHPA Pilot) included articles from distinguished NASA scientists like R.T. Jones and Hewitt Phillips. These contributions were fundamental and essential for advancing our understanding of airworthiness, which was a preeminent concern with fatal accidents growing at an alarming rate.

Within two years, SCHGA developed the foundational administrative architecture that continues to serve USHPA today, including the regional representation with directors and committees to develop safety and training, a pilot rating system, competition structure, accident reviews, site management, and other critical issues. These meetings also spun off another group focused on airworthiness, which later became the Hang Glider Manufacturers Association (HGMA), the seed for other international airworthiness programs and even the consensus airworthiness standards more recently adopted by the FAA for light sport aircraft.

If I were to identify an individual who singularly contributed the most to the development of hang gliders worldwide, it would be Tom Price. He invented and developed the hang gliding test vehicle and shared it with everyone. His contributions to advancing structural integrity and un-

Angie Kennedy hang gliding Ute Pass in Colorado. A pilot paragliding Merriam Crater in Arizona. Pascal Joubert pilot speedflying the Big Horns in Montana.

USHPA PILOT 7

Martin Palmaz > Publisher executivedirector@ushpa.org Liz Dengler > Editor editor@ushpa.org Kristen Arendt > Copy Editor Greg Gillam > Art Director WRITERS Dennis Pagen Lisa Verzella Carl Weiseth

Ben White Audray Luck

Warren

PHOTOGRAPHERS

cover photos by Tom Galvin Brad Balser Seth

derstanding longitudinal stability through the test vehicle and analysis with Hewitt Phillips and Gary Valle made aerodynamic advances possible in the years following 1977. You cannot increase hand gliding or paragliding performance without the constraint of airworthiness, which consists of controllability, structural integrity, and stability. Forty-five years later, the test vehicle remains the best mechanism we have for evaluating longitudinal stability and structural integrity.

The exponential growth of hang gliding soon led to motorized applications, beginning with auxiliary power systems like the Soarmaster and more dedicated systems adapted to the Quicksilver, Fledgling, and Easy Riser rigid wings. With the widespread commercialization of these systems, it became increasingly apparent that federal regulation was unavoidable.

FAR part 103, which governs the operation of hang gliders and ultralights, was enacted and became effective in October 1982. Much could be said about this rule-making, but it is widely acknowledged that the expansive freedom of operations it preserved for hang gliding relied heavily on the extraordinary record of responsible self-governance demonstrated by USHGA and HGMA in the preceding years. This was a windfall of epic proportions at the very margin of the authority of the FAA to enact without congressional authorization, which USHPA has been essential in preserving for the last 40 years.

Although the roots of paragliding are contemporaneous with modern Rogallo-derivative hang gliding in the 1960s, the beginning of the sport didn’t develop until the late ‘80s in Europe. In the U.S., Fred Stockwell established the American

Author and current USHPA President Steve Pearson test flying the prototype XC7 in 1978.

We are the beneficiaries and custodians of an extraordinary confluence of events and people who enabled the freedoms and privileges that the free flight community enjoys today.

Paraglider Association (APA) in Salt Lake City in 1988 and was soon producing a full-feature color magazine and developing administrative programs that mirrored USHGA.

Rob, Mike, and I began flying paragliders between 1989 and 1990. We recognized the commonality between hang gliding and paragliding—the pilots, the flying sites, the soaring activity, other skills, and flight training requirements. It just didn’t make any sense to have two representative associations. Rob and I made several trips to SLC and eventually persuaded Fred to relinquish APA and support a merger with USHGA. Although there were tokens of resistance, USHGA leadership ratified the inclusion of paragliding at the November 1990 board meeting, and paraglider pilots soon realized all the benefits of USHGA programs for ratings, safety, training, competition, and, of course, site access. Fred became the chairman of the USHGA paragliding committee, but it took until 2006 before the membership voted for the name change to USHPA.

One thousand words aren’t enough to identify all the individuals who have made significant and enduring contributions to our community, much less detail who they were and what they did. We are the beneficiaries and custodians of an extraordinary confluence of events and people who enabled the freedoms and privileges that the free flight community enjoys today.

After all these years, I still fail to understand why the free flight experience isn’t

widely popular. Even as the barriers to accessibility and safety have improved, we still haven’t regained the public interest and engagement level of the ‘70s. Nevertheless, I remain optimistic because every pilot, regardless of experience, shares that same wonder as I do on every flight—what else compares to standing with a light breeze on your face and, with a few steps, climbing skyward? Even those with only a tandem or introductory lesson often consider it to be one of the most memorable experiences of their life and forever identify as hang gliders pilots.

Today, pilots are seemingly assaulted by imminent threats to our lifestyle, such as increasing costs, burdensome rules, and liability exposure—but these challenges are not new. Similar to previous challenges, we sometimes became distracted and overwhelmed with disagreements on how to handle these issues. However, this diversity of experience ultimately contributes to the best possible solutions and outcomes. We are better and stronger together despite ever-present disputes on policy and procedure.

There are endless opportunities to contribute to the aspirations that we all share—for improved safety, site security, community growth, and well-being. As in 1973, the best way to secure our future is to volunteer—whether as a mentor or observer, at an event, with a chapter, on an USHPA committee, or as a director. Imagine what you want for the next 50 years, and let’s work together to achieve it.

Steve Pearson President president@ushpa.org

Matt Taber Vice President vicepresident@ushpa.org

Jamie Shelden Secretary secretary@ushpa.org

Bill Hughes Treasurer treasurer@ushpa.org

Martin Palmaz Executive Director executivedirector@ushpa.org

Galen Anderson Operations Manager office@ushpa.org

Chris Webster Information Services Manager tech@ushpa.org

Anna Mack Membership Manager membership@ushpa.org

BOARD MEMBERS

(Terms End in 2023)

Julia Knowles (region 1)

Nelissa Milfeld (region 3)

Pamela Kinnaird (region 2)

Steve Pearson (region 3)

Designated Director 1 (TBD)

Designated Director 2 (TBD)

BOARD MEMBERS

(Terms End in 2024)

Charles Allen (region 5) Nick Greece (region 2) Stephan Mentler (region 4) Tiki Mashy (region 4)

What's your region? See page 63.

USHPA PILOT 9

EPIC 2 MOTOR

The popular Epic 2 EN-B model is now DGAC certified for motor flight. The BGD EPIC 2 MOTOR is “fun on steroids”. It’s a hybrid wing, which means you can fly it with a motor or without—the only difference is the riser set. The MOTOR version is delivered with paramotor risers which feature an efficient trimmer system with a wide speed range for cruising comfortably under power. The EPIC 2 MOTOR comes in three colors and includes motor risers. Contact your dealer for more information. More information: www.BGD-USA.com, Dale Covington +1 801-699-1462.

NIVIUK HAWK POD

Designed specifically to be the ideal choice when making the transition from an open leg to a pod harness, without a large rear fairing. The Hawk is stable, comfortable, and light (medium 3.8 kg). Finally, a harness which addresses different body types (long/short legs or torso) giving you the option to mix sizes between the harness section and the pod section to get the perfect fit. Every harness size has three pod options. Visit www.eagleparagliding.com for more information.

ADVANCE FASTPACK

The popular Advance FASTPACKs have been updated with new designs, colors and sizes. They are now offered in two sizes 160 L and 200 L and they start at 1.3 kg. They are available through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

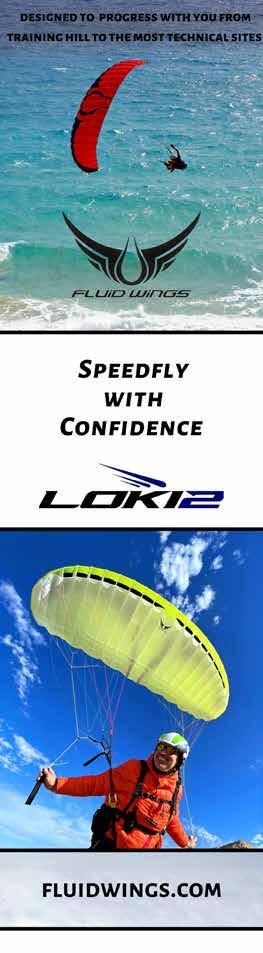

FLUID WINGS LOKI 2

Fluid Wings introduces the Loki 2, a new entry level/recreational speedwing. Designed to make all avenues of speedflying accessible to any speedwing pilot, ranging in ability from the training hill to the most technical mountain terrain. Speedriding, speedflying, and speed-soaring are all in the Loki 2’s repertoire. It is constructed of hybrid materials to optimize weight and performance, including soft brake toggles for a comfortable grip and rear-riser steering for those steep descents. The Loki 2 risers have dual hookin points for pilots to choose the riser length of their choice. The wing’s overall balance from its ease of inflation, ease of kiting, precise control in flight, and strong flare make for a super fun and confidence inspiring experience. You can learn more about the Loki 2 at www.Fluidwings.com, and order via info@fluidwings.com and +1 888-24FLUID.

FLYMASTER BUMPER CASE

Now available for the new Flymaster GPS M and new Flymaster VARIO M is the bumper case to protect your instrument. Easy to mount whilst still giving access to the buttons. Exclusively available from Flymaster USA for $35. More info at www.flymasterusa.com or email directly Jugdeep@flymasterusa.com.

10 USHPA PILOT

NEW BGD HYPERFUNCTION JACKETS

BGD has released a new version of their popular HyperFunction puffy all-weather jacket. The new design features reinforced seams, weather-protective zips, zippered pockets, pit-zips, and a hood. Constructed with animal-free, ultra-light, synthetic down feather fill and nylon outer shell. The jackets come in two new colors: Scarlet Chili Red and Deep Sea Ice Blue. Available now from your local BGD dealer: www.BGD-USA. com, Dale Covington +1 801-699-1462.

NIVIUK ARROW POD HARNESS

A high-performance pod harness designed for XC adventures, and starting competition flying, weighing just 3.95 kg (size M). Details include powerpack pocket, suitable for cables of different electronic devices and a 4 L ballast storage pocket. The Arrow addresses different body types (long/short legs or torso) giving you the option to mix sizes between the harness section and the pod section to get the perfect fit. Every harness size has three pod options. Visit www.eagleparagliding.com for more information.

ADVANCE EPSILON DLS

awaited tenth version of the EPSILON is the DLS. It’s a true mid-B glider for a broad range of pilots. It is a durable light glider in DLS (durable lightweight structure) spirit from 3.5 kg. The successful EPSILON series conveys not only fun and enjoyment, but above all, safety. The ideal paraglider for recreational pilots available in Royal, Spectra, Fire and Gold. Available in a variety of sizes through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

ECHO 2

The ECHO 2 is made entirely from high quality and industry proven Porcher cloth, with sturdier cloth in the center panels where it is needed for additional strength and to ensure longevity. The ECHO 2 has the same webbing risers as on the EPIC 2, much easier to handle than Dyneema rope-style risers. They incorporate the same B/C steering system as on the EPIC 2, and similar to the BASE 2, allowing you to safely explore the entire bar travel. The ECHO 2 is designed to be accessible to lower-airtime pilots, and fun for all. Pilot feedback was key in helping design a wing that launches perfectly. No holding back or over-flying. It’s easy and relaxing, allowing pilots to maximize performance and fun. The ECHO 2 is a bit faster than the original and more dynamic. Long brake travel makes for a late stall point, yet has precise and direct handling like all BGD wings. Contact your nearest BGD-USA dealer for a free demo, or direct from BGD-USA: www. BGD-USA.com, +1 801-699-1462.

BGD ULTRA-LIGHT ANDA

BGD has a new, ultra-light hike-and-fly wing on its way, the BGD ANDA. Currently in certification, this new hike-and-fly fun-machine is targeted as an entry-level hike-and-fly, funfor-all EN-A wing, weighing in at 2.7 kg in the 21 m size. It has 37 cells with no mini-ribs and is expected to support a broad weight range with sizes 21, 23, 25, 27 and 29, and will be certified in extended weight ranges. The ANDA is constructed with sheathed lines and softlinks. A and B risers are made from Kevlar webbing, while the C risers are Dynema. Contact your local BGD dealer to get on the advance order list: www.BGD-USA. com, Dale Covington +1 801-699-1462

WOODY VALLEY CREST HARNESS

The Crest is a 1.98 kg (size M) reversible harness with a completely detachable rucksack. Great for hike-and-fly pilots as well as pilots wanting a light harness with no compromise on comfort. No front mount reserve needed since it’s under the seat reserve compartment, with separate leg support without seat board. The leg straps loop in the main carabiners to reduce weight. Visit www. eagleparagliding.com for more information.

PHI MAESTRO 2

With 76 cells, additional mini ribs, a new profile, wing tensioning, and other new technologies, the Maestro 2 delivers. This is Phi’s greatest leap in performance ever achieved from one model generation to the next. The stability of speed is confidence inspiring, and roll stability removes any unnecessary inefficiencies on glides. The Phi Promise has you covered for any damage in the first year of use through The Eagle Paragliding Repair Shop. Visit www.eagleparagliding. com for more information.

PHI R07 RISERS

These risers come standard on the Maestro 2. The R07 risers offer much better ergonomic function for pilots wanting to use the C-handle flying technique. These specialized risers are produced with different overall total lengths, and speed system length based on your Phi glider model and size. Phi continues its revolution to maximize performance, feel, and handling wherever it’s possible. Visit www. eagleparagliding.com for more information.

CHARLY POLARHEAT LIGHT

Warm, soft, and pliable battery heated gloves eliminate the threat of line tangles with long gauntlets, internal drawstrings, and flat integrated stoppers. Two battery pockets per glove give up to 10 hours of heating time. Made with a 3-layer windblocker softshell exterior, goat nappa leather on the palm, Polartec® Microfleece lining, and Primaloft® outer insulation to keep hands warm and dry. The Polarheat Light gloves are excellent for paragliding and ski touring. Available in sizes S, M, L, XL, and XXL through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801255-9595, or your local dealer.

GIN GRAPHITE JACKET

The Graphite jacket features the latest comfortemp® Thermal Insulation by Freudenberg, which offers an eco-friendly and easy care alternative to down. The jacket is designed for comfort in the air while avoiding overheating on the ground. It is 413 g (M size), and very compact. It comes in sizes XS, S, M, L, XL. In addition to the outer shell and insulating filling, it has a zippered inner chest pocket, outer chest pocket, two hand pockets, and elongated back and extra arm length. It’s available through Super Fly, Inc., www.superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

ADVANCE AXCESS 5

The fifth generation of the extremely popular all-round harness AXESS is here. It has a plastic seatboard in hollow-chamber construction. Proven features such as the harness geometry, the protector system, and the size distribution remain unchanged. Many details have been refined and optimized. Available through Super Fly, Inc., www. superflyinc.com, +1 801-255-9595, or your local dealer.

XC TRACER MAXX 2 WITH FLARM

Unlike conventional variometers with delayed sink and lift tones, the XC Tracer Maxx II’s sensors follow a complicated mathematical procedure to eliminate this delay. Finding and centering thermals with a Maxx II is much easier than with a conventional variometer. The Maxx II has a real FANET including FLARM built in, which means Maxx II can also receive data from other FANET. Adding other Maxx 2 pilots to your screen field is a simple few clicks on the red button. The vario inputs can also be controlled with a remote, which is sold separately. Visit www.eagleparagliding.com for more information.

XC TRACER MINI 5 WITH FLARM

Don’t be surprised if you never have to charge your XC Tracer Mini V during a whole season! The vario has a built-in lithium-polymer battery which, fully charged, lasts for about 30 hours of continuous use. But as the battery is recharged during flight by the built-in solar cells, the autonomy is almost unlimited. The new Mini V also continuously transmits your position via FANET and FLARM. Visit www.eagleparagliding.com for more information.

USHPA PILOT 13

From Idea to Origin

The path to creating SkyGear Hub

by Shane Parreco

: Most of us would agree that learning to fly a paraglider is one of the most exciting and rewarding things humans can do with a bit of their time on this planet. Feeling the wind on your face while leaving the ground for the first time is thrilling and usually hooks us for life. I’ll never forget my first flights. I knew right away that I was always meant to do this kind of flying.

In 2009, my training started in an unusual way. I connected with a colorful, older paramotor instructor, and after a long and exciting phone call outlining the details, I officially started my flying career. At first, my instructor seemed like an unusual cross between Gandalf and Viper from the original Top Gun: equal parts impressive and eccentric. I quickly realized that he was further off the beaten path than I anticipated. Regardless, his introduction to the sky affected me profoundly, and I was hooked.

Soon after, I made my first pilgrimage to the Point of the Mountain, Utah and fell in love with everything paragliding—from the vibe at the hill before an epic sunrise to the sound and feel of a crispy new glider to

the smile that happens when you realize you’re the first one in the sky. It all felt like a dream that I hoped would never stop.

It was at the Point, almost 15 years ago, when the idea first struck me: How cool would it be if there was a way to research and compare gliders from every manufacturer and see them in a unified infographic layout? In my head, the visual looked similar to how most companies showcase their glider portfolio but built so that it would include every paraglider in the world.

Most of my new friends back then laughed at my wideeyed enthusiasm for such a crazy idea, but it stuck with me, and I eventually started to take steps to make it a reality. The way SkyGear Hub came to be is far less dreamy and took way more time, energy, effort, and talented people than I might ever have imagined, but the journey has easily been one of the most rewarding experiences in my life.

Before the spring of 2018, the closest I came to building a website was asking my one coder friend, Mike Wathen, if he would consider making something for fun. He usually obliged and used all kinds of words like ‘Drupal’ or ‘Javascript’, which meant nothing to me. So, to say I was a novice in web development was a bit of an understatement.

The event that set all of this into motion in 2018 was when I became a paragliding instructor. During my

14 USHPA PILOT

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | TRAINING

training, I discussed the idea of building an online education resource for paraglider students with some of that same wideeyed enthusiasm from my early days of flying. But this time, it didn’t feel quite so impossible. As soon as we finished training, I began working on a website to host a student training syllabus and make educational material accessible for anyone learning to fly. The syllabus was written by Doug Stroop, Denise Reed, Marty DiVietti, and Chris Grantham, and after a couple of encouraging phone calls, it was clear the time to make this idea hap-

pen was now. Not long after the first basic version of the site launched in the fall of 2018, the requests for improvements from students and instructors started pouring in. Can we make it more interactive? Can we make the quizzes functional and record the answers? Can we put more pictures in the section about clouds and weather? What about video? Can our students log their flights? What about a P2 checklist? And that was just the beginning. It was clear that constant improvement and building additional functionality was the name of the game, and the time to start was yesterday. The workload was significant, and I needed consid-

USHPA PILOT 15

erable help to support an online training platform that worked well and had room to grow in the future. It started with just one part-time freelance developer, then two, then a dedicated engineer, and finally, a designer to help build the infographic gear research website. And so it went for several months until I got an email from a paraglider pilot in Oregon offering to help. That first call with Steve Roti would end up being one of the most important calls for the future of both websites and the small team we were building.

If you don’t already know him, Steve is one of the kindest humans you might ever meet. His experience in technology and database management is grand wizard

status. You might never know it because his passion for flying, nordic skiing, hiking, biking, and travel keeps him outdoors most of the time. However, when it comes to data modeling and database management, Steve is on a level most people don’t even know exists. I can say without a doubt that the SkyGear Hub and Glider Training websites would not have been possible without his guidance, insight, support, and many hours of coding, troubleshooting, and brainstorming.

With Steve’s expertise lighting the path for our small bootstrapped team, we set clear goals for getting both sites ready to introduce to the world. Early versions of the Glider Training platform have been around since my feeble attempts in 2018, but the SkyGearHub.com and improved GliderTraining.org websites officially launched in early summer of 2022. The response from the community has been amazing, and we see more students and schools joining the platform every month. Ultimately, my goal has always been to make something that would positively impact the whole free flight community. SkyGear Hub has become a platform where you can research almost every glider, harness, and reserve. It is a place to visually understand how you fit your gear and learn about other brands an all-in-one place to access links to equipment reviews and gear manufacturers, and a way to find the Glider Training site that provides access to educational materials and allows people to sign up for online courses with some of the world’s top pilots and instructors. Above all, it serves our mission is to encourage people to approach the world of flying with curiosity and a desire to learn more.

16 USHPA PILOT

Steve Roti.

USHPA PILOT 17

2022 Highland Challenge

A race-to-goal mini-comp recap

by Charles Allen

: The Highland Challenge (HC) is an unsanctioned race-to-goal (R2G) hang gliding competition aimed at gathering friends to fly competitive but fun tasks in a safe environment where pilots can learn from each other. The first HC was held in 2012 at Highland Aerosports in Ridgely, Maryland, comprised four weekends from late spring to early fall, and was scored like any other R2G competition.

When Highland Aerosports closed in 2016, the sport and the event lost an important focal point. However, the HC continued, and I changed the format from an aerotow competition to a mountain competition with basecamp at my weekend house in Liverpool, Pennsylvania. In 2021, we resurrected the aerotow format and decided to have it span eight consecutive scored flying days plus one practice day.

Keeping the event unsanctioned had some advantages. Specifically, we could focus on making it fun and fair without dealing with time-consuming processes and procedures. For example, all pilots should have the opportunity for a good start regardless of launch order. Though not enforced, we encourage the first pilot to be towed to a thermal regardless of tow height or time on tow. The following pilots are then towed to the first pilot and encouraged to pin off when in the soarable lift. The last pilots are towed to the main gaggle with no required pin-off altitude and as close to the edge of the start circle as possible. This methodology ensures a better chance of getting all pilots flying together on course in less time. In 2022, I opted to continue with the aerotow format for another friendly event.

18 USHPA PILOT

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | COMPETITION

Highland Challenge 2022

The 2022 HC started on June 3 and was spectacular; it was the best week of flying I’ve ever had on the Delmarva Peninsula. We towed from a private grass airstrip in Chestertown, Maryland, about 16 miles NNW of Ridgely—the former home of Highland Aerosports and the East Coast Championship (ECC). The field is situated on farmland and has a hanger with power and water, so it can accommodate both tents and campers. The Delmarva Peninsula has similar weather conditions to Florida but on a smaller scale; the Chesapeake Bay is on the west of the Peninsula, and the Atlantic Ocean is on the east, creating a convergence zone with cummies often filling the middle.

Climbs are typically close together and soft, peaking at 400-600 fpm on a good day. The region is flat cropland with no livestock, and few properties have fences or locked gates, so there are abundant spacious LZs, and retrieves are seamless. The first week of June 2022 had ideal weather, and the crops were low, so even the corn fields were landable. This year we only had six pilots participate despite having room for 12—though a few local pilots stopped by to ground crew and wind dummy. We had two Dragonflys on site, but we only had enough pilots competing to justify hiring one full-time tug pilot. However, Ric Niehaus, one of the competitors, was gracious enough to tow a few pilots before flying the task himself. Additionally, some local pilots stopped by and did a few tows in the spare tug.

Task 1

It was a perfect day for this region. Unfortunately, an active temporary flight restriction (TFR) limited our course options since President Biden was at his Rehoboth beach house. We had to under call the task and decided on a 76km dogleg task to the southeast. The first leg was 26km to the east, followed by a 50km leg south alongside the TFR, leaving us an 8km buffer. Goal was Magfar, another grass strip often used in the

late ECC.

I launched first, followed by Knut Ryerson and John Simon, and we climbed to almost 7,000 ft. We were starting high with good-looking clouds on the course line, so I led out with John slightly behind and Knut below as the rest of the field was just getting airborne. We were finding good thermals and getting high for the region.

Around this time, Jim Messina and Pete Lehman were at cloudbase in the start circle about to go on course. However, Ric Niehaus decked 2km from the tow field landing at Ben’s estate. Ben, a former HG pilot who owns the tow field, was kind enough to let us host the event at his place. The extra tug was quickly dispatched to Ric’s location for a relight, and a volunteer ferried him a cart saving him from attempting a foot launch aerotow. This clearly would be against the rules in a sanctioned comp, but without those restrictions, Ric got back in the air and even made goal. Back on course, Knut was having instrument issues, but John and I tagged the first turnpoint then flew the whole 50km second leg to goal together. However, John left slightly before me at the top of the last thermal. Though I could have easily shadowed him from above on the final glide, guaranteeing me a day win, I made a strategic mistake. I opted to fly a straight line to goal, which was left of his line. Unfortunately, my line had more sink, and I had to slow down while his buoyant line allowed him to pull on more speed and beat me to goal by about two and a half minutes.

Five of the six competitors landed at goal, including John, who won the day followed by me in a close second. Despite missing the turnpoint due to instrument troubles, Knut did land at goal. Moreover, conditions were so good that I believe everyone set their site altitude records of over 8,000 ft. After a day like this, we figured the rest of the tasks must be downhill.

Task 2

With a weak forecast for Task 2, we set a short 37km dogleg to the north, which proved tricky despite its

USHPA PILOT 19

The participants of the 2022 Highland Challenge.

length.

Pete Lehmann towed first, followed by Jim, Knut, John, me, and Ric. Jim and John climbed to cloudbase and started towards the first turnpoint, followed by Pete, who eventually got low and opted to fly back to the tow field instead of completing the task.

I was in the start circle and saw Ric in a nice climb under a decent-looking cloud downwind to the north, albeit off course line, but I opted to glide to it. I arrived low to a dissipating cloud and broken zero to 50fpm lift. With no other options, I changed gears and worked the light lift until it finally turned on. Soon after, I saw 20+ soaring birds nearby and joined them—after 25 minutes, I was able to climb to 5,500 ft.

Though it was a bit late in the day to be starting a task, I pushed forward. I glided down the course line to a cloud and connected with the thermal just 1,000 ft away from the first turnpoint. However, since I was down to 2,200 ft., I decided to take the climb and drift downwind instead of pushing 1,000 ft. upwind and hoping I would find a climb after tagging the turnpoint.

Around this time, Ric had decked it about three-quarters of the way to the turnpoint, Knut opted to land at the tow field, and Pete, after a low save from 850ft., flew back to the tow field as well. With the challenging conditions, pilots were dropping like flies.

At almost 5 p.m., I tagged the first turnpoint and started towards goal. The day was getting very soft. As far as I could see, there was only one cloud left which luckily

was right on course line to goal. As I glided, I watched as it slowly fell apart; I arrived at 2,000 ft., but luckily there was still lift. As I slowly climbed in the light lift, I monitored my required L/D to goal as I drifted downwind. (This is my favorite part of the day when you know you’re about to have goal in reach.) Once I had goal made with an under a 10:1 required glide ratio I went on final glide.

Upon arrival at goal, I heard Jim and John (still airborne) chatting on the radio, and they directed me to land in a huge field about 2km past the goal cylinder. It was a stretch to reach as I had to fly over high-voltage power lines but I was lured by the prospect of a waiting driver, wind direction briefing, and cold beer. Upon arrival, I searched the edge of the field, but there was no Jim, no John, no driver, and no beer. Jim and John had hooked a thermal at goal and decided to attempt to fly back to the tow field. They flew about 36km and landed just a few kilometers short.

While not as good as the first day, everyone had fun, with John again winning, followed by Jim, and me in third.

Task 3

The weather for Task 3 called for a blue day with strong winds. However, in our desire to have an easy retrieve, we opted for an upwind triangle instead of a downwind dogleg which would have been the smarter choice for the conditions.

20 USHPA PILOT

Jim, Knut, and I were out on the course first and flew together for one thermal past the first turnpoint at Taylor. The wind was a major obstacle—we were drifting 8km downwind with every thermal and barely making ground. John had a zipper issue, went back to land, and opted not to have a second flight. Pete packed it in around Taylor and flew back to the tow field.

As for Jim, Knut, and I, we were together until a few kilometers past Taylor, where Knut missed a thermal and glided as far as he could before landing. I managed to stay with Jim until 13km from RT314, the second turnpoint. He found a reasonable climb, but I wasn’t able to connect. It was late in the day, the lift was weak, and the winds were strong. While I was drifting downwind away from RT314 and circling in zero sink, I decided that completing the course wasn’t attainable and I would have more fun flying back to the tow field.

As I returned, the bay breeze was in full effect, giving me yet another headwind. However, I made it back with altitude to spare—Pete radioed the wind direction and handed me a beer after landing.

No one made goal, but Jim won the day, landing shortly after tagging the RT314 turnpoint.

Task 4

The weather for Task 4 looked good, with light wind, modest lift, cummies, and cloudbase forecast to be 3,500 ft.—a respectable forecast for the eastern shore. We set a 57km triangle with goal at Ben’s house.

The beginning of the day involved a series of low saves. Though we started out climbing the blue, there were clouds to the east in the convergence zone, and we were clearly on the edge. Decisions at the start of this day were quite varied—Pete went back to the start thermal for a relight before heading onward, I decided to glide downwind on course to a cloud that seemed reachable and in the convergence zone, and Jim saw a wispy to the southwest, and headed for it managing to keep the tow field in glide. He connected with a nice

climb and was on his way.

I had a few good climbs but kept finding myself low and needing to scratch out. At one point was at a mere 600 ft. before finding some zero sink to search in. I managed to change gears quickly and having just pulled off a low save from 800 ft. I patiently worked the broken zero to 50 fpm lift, keenly focused on every foot of altitude gain. It took me 5 minutes to climb 200 ft. staying very flat and not banking despite occasional spikes of 100 fpm. I felt like a frog jumping from lily pad to lily pad. After breaking 1,200 ft. the thermal came together and thirteen minutes later I topped out at 3,200 ft.

Jim, John, and I were equidistant from Temple, the

first turn point. However, I was 4km left of the course line and 1,000 ft. below the others. Given my lower altitude, I opted to continue flying downwind and slightly off course line to the next cloud, hoping I could get back on course once higher, and I found a nice thermal that brought me to 3,200 ft. There was a nice stretch of fields going through a forested section heading to Tem-

USHPA PILOT 21

Gliders in goal after Task 1.

Post Task 4 merriment.

ple, which I followed like a road on glide getting down to 900 ft. before once again finding broken zero lift. I noticed some eagles circling in the area, headed over to them, and quickly got established in the 300-400 fpm core, which took me back to 3,400 ft.

As I tagged the Temple turn point, I saw Pete out front thermaling, which was a huge relief. After flying for almost an hour and a half by myself, mostly down low, I was excited for some company. We shared the thermal, but after reaching 3,600 ft, the climb started to fall apart, so I left Pete to go on glide to a nice looking

cloud 2km left of course line bringing me closer to the Ridgely turnpoint. As I continued, climbs were stronger and more consistent.

Once over the familiar fields surrounding Ridgely, where I have flown numerous times at Highland Aerosports, a flood of memories came back. I knew the fields well and had a high degree of confidence I’d make goal. I tagged the Ridgely turnpoint, found a good thermal on the final leg, and headed for goal. I arrived fourth into goal, with Pete showing up 20 minutes later.

With 5 of 6 of us in goal, everyone was ecstatic. It was a challenging day, but, at least for me, it was the most rewarding flight of the week. The LZ couldn’t be better; we landed on a beautifully cut lawn next to Ben’s huge saltwater pool. We all put on our bathing suits and raided Ben’s fridge.

John won the day yet again, followed by Jim and then Ric.

Task 5

Task 5 was the last day of the comp, and the forecast was perfect for a beach run. Biden had

22 USHPA PILOT

Charles Allen landing at the beach for Task 5.

Pilots at the beach after Task 5.

TASK 5: We all flew over the ocean and did wingovers for the Dewey Beach crowd prior to landing.

MAY 18-21, 2023

left his Rehoboth beach house, so there was no longer a TFR impeding our task. Encouraged by the great forecast, we packed our bathing suits.

The task was a 90.5km dogleg to a turnpoint at Willav, a grass strip, followed by goal at Indian Beach. In the spirit of being a fun comp, we put an 8km radius around Indian Beach so pilots could make goal and land at the last viable field before having to fly over the unlandable town of Rehoboth on route to the beach, making the distance to Indian Beach just under 100k.

Tom McGown, a local pilot not in the meet, joined us for the day, launched first to wind dummy, and once established in lift, we all promptly started launching. We had some nice consistent climbs that took us quite high. I had to pull out one low save after a long glide, but with patience, I managed to make it back up to 5,900 ft.

Jim made goal first, followed by Pete a few minutes later, and I was 10 minutes after them. I watched Jim and Pete land at Indian Beach from afar and radioed for them to snap pictures of me landing. Indian Beach

is private, so it was sparsely populated compared to the dense summer crowds on Dewey Beach just up the coast. We all flew over the ocean and did wingovers for the Dewey Beach crowd prior to landing. John landed about 10 minutes after me and, despite having the fastest time on the course, was third for the day because he took the 2:15 p.m. start clock. Though Knut and Tom didn’t land on the beach, they both made goal landing close to each other at nice fields just inside the 8km Indian Beach goal radius.

While the 2021 HC was terrific, 2022 raised the bar. Not only were many personal bests had, but many genuinely unique flying achievements were made, cementing memories that will be cherished and last a lifetime. Despite being a comp, the sense of camaraderie at the HC differs from other events, making it more fun than larger sanctioned comps. In the air, everyone helps each other on the radio, and on the ground everyone is included in the festivities whether in group dinners or sharing stories around the campfire.

USHPA PILOT 23

DUNE AND AEROTOW COMPETITION • DEMO GLIDERS • FILM FESTIVAL

HANGGLIDINGSPECTACULAR.COM 51 st 51 st SCHEDULE & DETAILS

Personal lessons and advancements in the Valle del Cauca

by Angela BICKAR, OGNJEN GRUJIC, BENJAMIN SMITH, JOE POPPER

by Angela BICKAR, OGNJEN GRUJIC, BENJAMIN SMITH, JOE POPPER

: In the winter of 2022, four of us (along with a few others) signed up with Eagle Paragliding for a memorable flying tour in Colombia. We had 7-14 days of flying with Rob Sporrer and his team of exceptional guides—Jeff Shapiro, Marty DeVietti, Reavis Sutphin-Gray, Austin Cox, Brian Howell, Logan Walters, and Chris Garcia. The tour included daily coaching, debriefs, and the opportunity for in-air coaching via XC tandems. Evening presentations covered thermalling, gaggle flying, weather, the mental aspects of flying, and more. We were learning all the time, everywhere—it felt like drinking from a fire hose!

We all thoroughly enjoyed our experiences in Colombia and decided to collaborate on an article to

24 USHPA PILOT

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | GATHERINGS

Towasis tow training weekend at Laney’s Airfield, NC. Photo by Jared Yates.

COLUMBIA

of the

share our highlights and key takeaways. Flying in the beautiful Valle del Cauca and landing between vineyards, sugar cane, and corn fields was an incredible experience. The locals were friendly and always there to welcome us with big smiles and offer us a ride back to the hotel. We also enjoyed connecting with unique, interesting people

2022

Sunrise from the hotel. Photo by Joe Popper. Marty DeVietti kicking his eaglets out

nest at the Los Tanques launch. Photo by Benjamin Smith.

Eagle Guides (first bottom, left to right: Austin Cox, Marty DeVietti, Brian Howell, Jeff Shapiro, Chris Garcia, Flaco, Logan Walters, Reavis Sutphin-Gray. Photo by a local.

and making new friends on the tour. Flying-wise, we all made significant leaps in our progression. We flew long and far, became more efficient at thermalling, got comfortable with landing out, and reached our personal bests.

However, each of us also faced a personal struggle that affected our flying. Our sport is incredibly mental, and for many, the psychological aspects of our sport are the most challenging components to master. A big part of the Colombia tour was dedicated to the mental aspects of flying—this was where the Eagle crew truly excelled.

The four of us combined efforts to relate our personal mental struggles with flying, how they affected our flying and progression, and how we overcame or worked towards overcoming them. We each had a great experience working with our Eagle instructors and the incredibly supportive community of pilots with whom we had the pleasure of spending the tour. We hope the community will find our stories insightful, relatable, and, for those who face similar struggles, helpful in overcoming them.

Ognjen Grujic

Personal challenges: task overload, motion sickness, positivity

Throughout my flying career, I have faced many obstacles that hindered my progression. The one obstacle I have struggled with most was air sickness which always set in at about 45-60 minutes in thermic air. It prevented me from truly diving into the XC game for a long time. I tried it all! I stopped drinking alcohol, made sure to get a good eight hours of sleep, and I drank three liters of water a day to avoid dehydration. While the problem became less severe, it did not disappear. I started to believe that the problem was physical and that there was nothing I could do to entirely overcome it.

I went to Colombia with a lot of excitement but also with a ton of fear. I worried I might have to cut my flights short due to air sickness and would miss out on perfectly flyable days.

The smoke from a burning field makes an excellent wind indicator. Photo by Benjamin Smith.

26 USHPA PILOT

“We were learning all the time, everywhere—it felt like drinking from a fire hose.”

Throughout the clinic, the Eagle instructors talked a lot about the importance of being positive, having a good attitude, and being kind to oneself. Most importantly, they shared their personal struggles with flying and the mental tricks they used to overcome them. I loved what I was learning, and it helped me grow tremendously. One of the key takeaways for me was the importance of a positive attitude and self-talk, especially when the monkey brain turns on in rough air.

Toward the end of the first week, I got a chance to put this advice to good use. The air got rough, the monkey brain wanted me to land, and I could feel some mild motion sickness setting in. I calmed myself down by deciding to postpone landing for another 45 minutes. With some calming thoughts and self-talk, it worked! The air sickness did not get worse, and I continued flying.

I took one thermal after the other and ended up on the other side of the valley. A glance at my watch revealed that I was way past the 45 minutes I had promised myself. Soon after, things got rough again. I got low with a few landing options and started overanalyzing the landings with respect to a potential retrieve. The air sickness got to me super fast. I threw up over my shoulder and landed soon after. Even with this rough ending, I was shocked to see that my flight had lasted 2 hours and 38 minutes, my new personal record.

Evidently, my motion sickness problem was not physical—I took control of it with a positive attitude and self-talk. Towards the end of the clinic, after many discussions with the instructors, I realized that several factors contributed to my issue. I suffered from self-induced task overload, and my motivation for flying focused too much on the numbers game rather than the journey and the joy of flight.

Identifying the core of the issue helped me to resolve it quickly. I started flying with a big smile and enjoyed every second in the air. I started seeing each flight as an adventure, no matter how long it was. I also saw my progression as a journey rather than a competition. Following this experience, I had multiple long flights without air sickness, but I also had three consecutive days of sledders that I loved. The third one was particularly memorable with a beautiful onehour hike out. I crawled under a barbed wire fence, jumped over streams, and hiked through the fields.

The new me enjoyed it all, while the old me would have kicked the rocks and felt bad because of the sledder. Positivity works!

USHPA PILOT 29

Pilots Jeff Shapiro and Charles Chaffee walking past a sugar cane field after landing. Photo by Benjamin Smith. Cumulus clouds above and endless landing options below. Photo by Benjamin Smith.

Angela Bickar

Personal challenges: comparison, letting go of expectations, changing the narrative This trip was my second to Colombia with the Eagle crew. I love the tours because they enable me to surround myself with exceptional pilots and like-minded individuals. They challenge me to leave my comfort zone and make leaps in my paragliding progression.

I have been flying on and off for seven years, starting when my daughter was just a baby. I’ve had many memorable flights but also had some setbacks. My most significant setback was my reserve toss in June 2021 at Woodrat, Oregon. This was the first time it hit home that I was not invincible. It made me question why I fly and if the risks in this sport make sense for me as a mom. I am still working on rebuilding my confidence and bump tolerance.

I went to Colombia, anticipating this to be a challenge, but I was optimistic and still hoping for personal bests. However, the flights were not happening, at least not how I wanted them to. On day six, my teammate Ognjen and I landed early after a flight of only 12 minutes. I thought that by this point in the tour, I should be flying better, longer, and farther. As I was packing up my wing, tears filled my eyes. I felt impostor syndrome and was overwhelmed thinking about how everyone was progressing faster than me. I tried to heed the lesson that comparison is the killer of joy, but in the moment, it was difficult to rise above the emotions.

On our hike out, Ognjen reminded me that I could change the narrative. I took his advice to reframe the day and focused on the positives: I successfully parked the wing on a slope in a tight spot; I could celebrate a good launch, safe landing, and my growing confidence in landing out.

It was great timing that our guides, Chris Garcia and Marty DeVietti, gave a talk on the mental aspects of flying that evening. They emphasized a growth mindset: the belief that, with time, effort, and practice, we can improve. We can see challenges as opportunities to improve and use setbacks as a springboard to success. They also spoke about letting go of expectations and outcomes. Like flying the day and not the desire, Colombia was a reminder for me to let go of the pilot I was last

30 USHPA PILOT

LEFT: The hike up to launch. Photo by Joe Popper. RIGHT: The streets and surrounding hills of La Unión, a great place to find roasted chicken! Photo by Benjamin Smith.

summer and to embrace the pilot I am now.

Many of the same themes are echoed in my guide Jeff Shapiro’s book recommendation: “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius. “Meditations” led me to discover additional books on the wisdom of Stoic philosophy by Ryan Holiday: “The Obstacle Is the Way,” “Ego Is the Enemy,” and “The Daily Stoic.” When friends ask about highlights from Colombia, I share that I am most grateful for these transformative lessons that have given me a mindset that serves me well in paragliding as well as in my personal and professional life.

Benjamin Smith

Personal challenge: team flying is not for me, yet … Have you ever heard of a new pilot doubling their hours on a single trip to Colombia? That’s what happened to me this year. As a relatively new P2, I came into the 2022 trip with 18 hours, and I left with 36 and some new personal best flights. My goal for the trip was to get more hours, and I succeeded in that respect.

We received fantastic training from the Eagle instructors, and I valued all of it. But how could I apply those grand ideas to my beginner-level skills? Team flying, for instance, is an excellent concept that Eagle strives to incorporate in their XC teaching and radio coaching. When team flying, the more pilots you have sampling air, the greater the chance of finding the best lift. However, for this to work, you need everyone to stay together, flying at the same speed and altitude.

In Colombia, I tried to stay with the team, but I found myself repeatedly arriving late to the party,

USHPA PILOT 31

PWC pilot magic. Photo by Reavis Sutphin-Gray.

A gaggle of pilots working a thermal in the flats between La Union and La Victoria. Photo by Benjamin Smith.

angry), I realized I had to fly my way and at my speed. I discovered that I should do things like top out every thermal, keep recycling until I have someone (or something) marking lift for me, or even retreat to lift if nothing is developing out front. This strategy kept me in the upper half of the sky, where it’s easier to stay in lift.

It started coming together for me on my last day in Colombia. I found myself deep over steep terrain, and I had not seen any other pilots for the better part of two hours—they had left me behind because I was recycling so much.

After being on glide for about 10 minutes, I realized that if I didn’t find lift soon, I was looking at some challenging landing options. Everything below me was shaded out except for a cone-shaped hill next to a winding mountain road. The sun was illuminating this spot. It looked like a perfect little thermal trigger. I could imagine the lifting air dripping off of it. I headed straight for it, and voilà, I found lift. Though it was weak, I managed to gain about 500 feet before I spotted some birds and went to join their climb. Pretty soon, we were all skying out.

I allowed my wing to bite and steer toward the lift, and my vario sang. As I climbed, I found myself wondering where the birds went. I looked left, right, forward, and behind. When I finally looked up, I saw a big black bird soaring one meter above my wing, at the same speed, in the same direction, and maintaining an exact distance from my wing. We flew together for a couple of minutes before separating. What an extraordinary moment! There were no other pilots, just birds, finding a single trigger point above scary terrain. It was a magical day for me, redeeming all of the frustration and anger from the mistakes and bomb-outs of the previous days. I developed new strategies and regained perspective.

At this stage, I’m trying to get long flights to build hours, and I need to stay high in the sky to give myself the best chance. In taking my time and flying at my speed, I am finding I can stay in the air a lot longer and discover things I couldn’t if I were trying to keep up with the team. I’m looking forward to the day when I have the skills to team fly and knock off big XC flights with others, but for now, I am content to fly slower and stay up longer.

Joe Popper

Personal challenge: focus on the accomplishments, not the perceived failures Colombia can be whatever experience you want. If you are a beginner, it is a great place to improve your skills and initiate the XC experience. For intermediate and advanced pilots, it is a place to go big. Valle del Cauca is huge, with opportunities to fly far in almost any direction. In my first year, nearly every flight was a personal best, with the next day being even bigger and better. My skills

32 USHPA PILOT

were a bit off this year due to what I call COVID rust, but I still had an amazing time. The general progression of the day in Colombia was to launch around 10 a.m. into moderate lift. Launch sits at 5,300 feet, and cloudbase sits at 5,500-6,000 feet at that time of day. As the day progresses, base will slowly rise to 10,000-12,000 feet (on good days). During my trip this year, my max altitudes were 8,000 to 9,000 feet, and my flights averaged 2-4 hours. Others in my group got higher and flew farther. This year, it rained a lot in the morning, which made the early flying marginal, and I had several days where I struggled to stay up and find lift. On other days, I hung in with the big dogs for the whole day.

However, I spent too much time on negative thinking. I had several days where my group got low. I worked hard to focus on coring the thermal and flying where my fellow pilots were. Yet invariably, I would sink out, and the group would continue. This pattern continued enough that I began to give up sooner each time. When you are sitting on the ground watching your friends fly off, it’s so easy to become self-critical. I failed to focus on the other days when I would be the first to cloudbase and watch my friends catch up. I only focused on the negative and the self-criticism, and I didn’t take the time to recognize those accomplishments.

My fellow authors seemed faster at recognizing the need to be positive. For me, self-reflection happened during the writing of this article. I found I need to focus on the long list of successful accomplishments that occurred during an amazing flight and enjoy the journey. To put this in perspective, on a day where I missed a low save, I was joined on the ground by a highly rated world-class comp pilot who also missed his low save. It happens. Focus on the positive, learn the lesson of the day, and move past that negativity.

Conclusion

In coming together to write this article, comparing our experiences highlighted our shared mental struggles. We learned that reframing our experiences positively and welcoming challenges enabled us to grow. The challenge and struggle keeps us coming back, and we are grateful for the journey.

to right, top

USHPA PILOT 33

Left

to bottom: Ognjen Grujic, Marty DeVietti, Eric Kurzhals, Dave Pennington and Shaun Wallace.

2022 GLOBAL RESCUE XREDROCKS

by Gavin McClurg | photos by Ben Horton

: Hike-and-fly racing has been popular in Europe for almost two decades. The Red Bull X-Alps kicked it off in 2003, then races like the X-Pyr, Bornes to Fly, EigerTour, and VercoFly came into the mix in the following years. Now, dozens of others are happening across the continent, even in winter. Their popularity boomed even more when COVID shut down all the chairlifts and gondolas in 2020, turning just about every European pilot into a hike-and-fly pilot.

But here in the U.S., hike-and-fly racing hasn’t had the same trajectory—this is likely, at least partially, due to the terrain. Launches and nice places to top land are ubiquitous in the Alps. In North America, not so much. Our terrain is more treed, more rocky, more nasty, more private land, and way less accessible—it’s just gnarlier! However, after attending the Red Rocks Fly-In for a few years in southern Utah, I started thinking it might be possible to run a hike-and-fly race in the U.S.

Pilots launch day 2. Ben Abruzzo and Rob Curran stay high (and in color!), day 3.

Pilots launch day 2. Ben Abruzzo and Rob Curran stay high (and in color!), day 3.

I experienced remarkably reliable weather at the end of September and incredible cloudbase even that late in the season. Plus, the fall colors were a mind-boggling backdrop.

The potential for a race glimmered on the horizon for me, but most of the credit for the vision of a hike-andfly event goes to Stacy Whitmore, a local pilot in south-

ern Utah. While I agreed that flying in southern Utah is nothing short of epic, I didn’t have his conviction that it could work as a hike-and-fly arena. But Whitmore, having pioneered many of the launches in the area, saw the possibilities. His dream was to create an event that would attract some of the big-name European pilots to share both their abilities and methods, allowing our community to rub shoulders with some of the best in the world.

He asked me how we could get the Europeans to come. I responded, “Big prize money and good speaking fees!” And thus, the XRedRocks was born. The 2021 event featured two divisions—Pro and Adventure, and we landed on a format unique to hike-and-fly racing that, to my knowledge, hasn’t been done before: a three-day stage race. Each day, all participants would start together and race towards a declared goal. Each day would be scored as its own race, but the three days would be cumulative.

Day 1 racers take off on the first hike across Poverty Flats. Ari Delashmutt and the rest setting off on day 2.

36 USHPA PILOT

So, in theory, you could have a bad day and still win overall.

And then COVID hit. For the inaugural 2021 XRedRocks, Europeans weren’t allowed to travel to the U.S., so it was strictly a North American affair. But the weather was perfect; Utah did indeed work for hike-and-fly racing, and we had an awesome event. In the Pro division, Matt Dadam took home five grand in cash, followed by Bill Belcourt, and five-time X-Alps legend Honza Rejmanek. The tasks favored pilots who

USHPA PILOT 37

Gavin McClurg sets up the day. Looking into the Koosharem Valley, on the first launch on day 3.

TOP LEFT: Local ripper Lindsey Ripa takes to the skies. RIGHT: Aaron Duragoti soars over the autumn colors.

had great flying skills over those who had a fast ground game.

For the 2022 event, we had a race that had minimal resemblance to the previous year. We updated the name to Global Rescue XRedRocks, as we successfully brought on a title sponsor. We also managed to get some of the biggest names in the sport to attend: Italian pilot Aaron Durogati, a six-time Red Bull X-Alps athlete and the only pilot to have won the Superfinal twice, he holds several records including the Asia distance record—a 308 km FAI whopper in the Himalayas; Swiss pilot Patrick Von Känel, who placed second in the 2021 Red Bull X-Alps; French pilot Tim Rochas, a veteran world cup pilot and test pilot for Niviuk; and

Unfortunately, the weather in 2022 was about as brutal as it could get. A hurricane off the coast of California (which is pretty much unheard of) and a series of hurricanes and tropical depressions in the Atlantic combined to make for wet and windy weather all the way into Utah. The weather made task setting challenging and safety a serious concern.

On Day 1, our weather window for flying was short. We knew overdevelopment was guaranteed; it was just a matter of exactly when. A challenging course was set

38 USHPA PILOT

Frenchman Tanguy Renoud-Goud, who, until recently, held the world record for the most vertical climbed and flown in a single day and who will be a rookie in the 2023 X-Alps.

Swiss pilot and X-Alps legend Patrick Von Känel enjoying the colors of Utah.

starting at Poverty Flats, where the athletes would have to climb almost 3,000 ft. over several kilometers, launch quickly and fly down to the main LZ in Monroe. They would then have to decide to carry on by foot over 40 kilometers to goal near the town of Salinas or make another 2,500 ft. hike to the Cove launch and try their luck racing against the weather.

I estimated the fastest anyone could reach the first launch would be 90 minutes. Durogati showed up in 67 minutes, smiling and not even breathing hard. Rochas was hot on his heels and launched in under three minutes (give that a try— it’s really hard). Then a slew of athletes (including Eric “the Hammer” Klammer, who was the first to the top every day of the 2021 race and now had some competition), many of whom had participated in 2021 and had clearly taken training for 2022 seriously, were off the hill in quick succession. Nearly everyone who made it to the Monroe LZ chose the flying option from Cove, and the race was on. Durogati and Rochas had a comfortable lead, but as the steep and rocky

hike to Cove wore on, Durogati went full beast mode and pulled well ahead. I have raced with Durogati many times over the years and have seen how he moves. He’s always magnificent uphill, but this performance was in the ludicrous category. It was inspiring stuff.

Durogati made mincemeat of the 40 km flight to goal, landing a solid 20 minutes ahead of Rochas but declared the flying tricky. Large cells were dropping virga in our vicinity. Thankfully the fast-growing nimbus clouds shaded everything out so quickly that the energy backed off and allowed many pilots to thread the needle and make goal in the air. Goal in both divisions rapidly filled up with extremely happy and talkative pilots thrilled with their adventure and happy to be on the ground. Unfortunately, many athletes who were not fast on the ground didn’t make it to Cove before it was blown out and couldn’t launch. For some, it was a lot of walking and a long day. The day was short for those who could move fast on the ground early and make it into the air.

The weather on Day 2 was even worse, with higher forecasted winds and a very energetic sky. A task was set that would be physically demanding and keep the flying below

USHPA PILOT 39

Chris Moody and Jason Wallace grinding uphill.

the nuclear winds aloft. I estimated the fittest athletes could complete the course by 2 p.m. Again, I was way off. Durogati again decimated the ground game, crunching the first hike of 3,600 ft. and several kilometers in 1 hr. 32 min., with Rochas and Klammer just behind.

From launch below Monroe Peak, the athletes had to fly down to Poverty Flats, tag a ground turnpoint, and then either race into goal back in Monroe by foot or make a short hike and go for it in the air. Durogati chose the latter option and was in goal just before 11 a.m. Meanwhile, Isaac Lammers and Will Buckner charged insanely hard in the Adventure division, completing the physical course in 1st and 2nd (they would have been in 4th and 6th, respectively, in the Pro class)! Once again, the day punished those who were not fast enough on the ground. Launch got blown out 90 minutes after Durogati launched, and many pilots ended their day there.

The task setting got no easier on the final day of the race. High winds were again forecasted, but thankfully overdevelopment would not be as much of a risk. We decided to move the entire operation to the east and do an out-and-back route in the Koosharem Valley, a place with more wild animals than people (one of the turnpoints was near a ghost town).

Many of the most hearty participants on Day 3 covered well over a marathon on the ground. Most only got one short flight. Walking against the wind defined the day. But as we closed on the deadline, suddenly, the wind began to ease, and a few lucky (and very fast) pilots who had charged hard on the ground found themselves in a position to get back into the air and grab an absolute gem of a flight.

Canadian and 2023 X-Alps competitor James Elliot won the task in incredible style, flying nearly 60km in what he described as “magic air.” He landed at goal a comfortable 20 minutes before the mandatory land-by time. Being at goal and witnessing the elation on James’ face was something I’ll never forget. Thrilled barely describes it! Durogati landed in second, just a few hundred meters short of goal about 40 minutes later, declaring the flight “one of the best of my life!” We then learned he, Rochas, and Jared Scheid had diverted from their course and lost about 40 minutes helping another participant who had a scary (and thankfully injury-free) landing during their walk, so the win was declared a tie. The Global Rescue XRedRocks this year was really tough. It rewarded those pilots who had trained hard and could muscle it out on the ground and make solid flying calls when the opportunity was there. We didn’t fly as far, high, or deep as we wanted, but those days will come. They always do. But we had a great time in an arena where we’ve only scratched the potential.

Podium for the Pro Class. left to rright: Jeffery Longcor (4th), Kevin Carter (3rd), Aaron Durogati (1st), Tanguy Renoud-Goud (2nd), Tyler Burns (5th).

40 USHPA PILOT

Patrick Von Känel dancing with the Utah colors.

“We didn’t fly as far, high, or deep as we wanted, but those days will come. They always do.”

2022 Tater Hill Open

Part 1: Paying better attention to changing conditions

by Bubba Goodman

: The 2022 race was the 17th Tater Hill Open that I have coordinated. I’ve been flying the region since the late 1970s and have banked hundreds of hours and thousands of flights. I know this place well, and I thought, for the most part, that the weather was predictable. Our competition safety records speak for themselves. Until 2022, we never had any deployments. However, just one day in a friendly competition changed everything about how I look at the weather and pilots’ attitudes toward unsafe conditions.

For the 2022 event, we had a great turnout, with over 60 registered pilots. The two practice days were incredible. On Friday, many lucky pilots got over ten grand, and the site was flyable all day. Saturday could have been better, but still, people flew late into the day. Sunday morning, we had a pilot meeting at the LZ. By 9:30 a.m., we were running pilots up the hill. The mountain was ridge-soarable when we got there with a few early clouds. The forecast was for overdevelopment later, around 4 or 5 p.m., so the task committee came

42 USHPA PILOT

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | COMPETITION

up with a short task for both the open and sport classes. All turn points were in front and north, away from where the weather was supposed to be, with good LZs nearby.

The launch window opened at 11:45 a.m., and the start was 1:00 p.m. It was still blue over the back, but we had weak-looking clouds out front. As soon as a couple of pilots stuck, launching began quickly. A few bombed out, but, for the most part, everyone was staying up. It didn’t take long for it to OD toward Grandfather Mountain. This development is quite normal and routinely happens there first. We could see rain some distance away and convergence clouds behind launch, but out front, where the task was run, it was still clear.

There was talk on the radio of rain, but it was early, and pilots were happily running the task. However, as the rain to the south crept slowly toward us, I was getting more concerned and radioed to launch to ask what pilots up there saw. A couple saw rain behind launch to the north, so at 1:27 p.m. I stopped the task. As always at comps, when I stop the task, call the day, or can’t run a task, pilots will sometimes choose to launch or stay flying for a bit.

This day was no different. Some folks tried to get down as fast as possible, others took their time, and others stayed high and enjoyed some airtime. Behind launch, things were starting to build up, and pilots were having a hard time getting down. There were about 10 pilots up on launch, including a couple of hang gliders. We could see a big wall of dark clouds heading our way, so we were scrambling, trying to put things away. I was helping hide the gliders when I looked over my shoulder and saw a paraglider pull up and launch. The gust front was rapidly heading up the back of the mountain, and by the time we loaded everyone in the two trucks, it was blowing 40+ over the back. We drove down in a hailstorm with pouring rain.

When we got to the LZ, most pilots were on the

ground, but four were still in the air. Pilot #1 was having a great time surfing the storm, staying ahead of the gust front. Pilot #2 was trying to stay ahead and get down in a safe field. Pilot #3 had disappeared in the clouds, and folks on the ground were trying to help him by radio. Nobody knew who Pilot #4 was.

The first three pilots all landed in the same field some miles away. Pilot #1 had a great flight by staying in front of the storm, whereas Pilot #2 did not. He had tried many ways to come down, including B-line stalls—he was a little shaken by the experience. Pilot #3 flew through hail, snow, and rain and was coached from the ground on how to descend using advanced maneuvers. He, too, was shaken up by the experience.

What about Pilot #4? Around the same time the other pilots were landing, we received selfie pictures of a pilot on the ground in a big field with a reserve behind them. Only then did we realize who the pilot was. Looking at their tracklog, we saw they were up over 18,000 to 19,600 feet and finally threw their reserve to land safely. So here were four pilots, all in the same air, having totally different flights. The first three were caught in the air, while the fourth pilot chose to launch despite the approaching wall of rain, thinking he would take a sled ride down. All of this happened in a very brief period as

USHPA PILOT 43

Buck Nichols at Tater Launch. Photo by Lucas Soler.