HANG GLIDING + PARAGLIDING + SPEEDFLYING

Briefings 6 Editor 7 Association 8 Calendar 61 Classifieds 61 Ratings 62

Accident Review Committee by the Committee 10

Blodgett Open Space by Martin Palmaz 12

A New Shape by Sofia Puerta Webber 16 Finding ways to repurpose old gear

Calling All Female USHPA Pilots by Julia Knowles 22

Results of the Women's Committee poll

Between the Clouds and a Hot Place by Patrick Switzer 28 A Mojave notebook

Thermal Structures by Dennis Pagen 38

Using proxy plumes to decipher thermals

Notch Peak by Sarah Crosier 42

A para-alpinism adventure in Utah

Inherently Dangerous by Jeff Gildehaus 48

Warn the West by Kubi and Luki Jacisin 52

Paragliding tales from the equator

Installing weather stations by Brian Greeson 56

Cover Photo by Alexis Wheeler

At Torrey Pines Gliderport in La Jolla, one of Dave Metzgar’s lanner falcons soars with Steve Van-Fleet (red) and Jason Hull (green).

USHPA recommends new or advancing pilots complete a pilot training program under the direct supervision of a USHPA-certified instructor, using equipment suitable for their level of experience. Many of the articles and photographs in the magazine depict advanced maneuvers being performed by experienced, or expert, pilots. No maneuver should be attempted without appropriate instruction and experience.

©2024 US HANG GLIDING & PARAGLIDING ASSOC., INC. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior written permission of USHPA. POSTMASTER USHPA Pilot ISSN 26896052 (USPS 17970) is published quarterly by the United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, Inc., 1685 W. Uintah St., Colorado Springs, CO, 80904 Phone: (719) 632-8300 Fax: (719) 632-6417 Periodicals Postage Paid in Colorado Springs and additional mailing offices. Send change of address to: USHPA, PO Box 1330, Colorado Springs, CO, 80901-1330. Canadian Return Address: DP Global Mail, 4960-2 Walker Road, Windsor, ON N9A 6J3.

The Calypso 2 is your passport to a world of adventure, ready to discover new places and routes — both on the ground and in the air.

The Calypso 2 is a true lightweight design, aimed to perfectly match the needs of leisure and progressing pilots who like to travel, hike and even do some XC.

5 Sizes | 55-115 kg | EN B

GLOVES The Airlight gloves by Ozone are lightweight gloves ideal for flying in warm weather or short flights at other times. They pack very small and feature high-quality leather inside with clarino lining. An all-season variation, the Air Glove, is an anytime, anywhere option, with durable Lycra and high-quality Primaloft insulation. Both gloves feature reinforcements on the index finger and the side of the hand to prevent wear and tear from lines and a touch-screen tip on the thumb and index fingers for instrument use. The wrist leash keeps the gloves safely tethered to you when removed in flight. www.flyozone.com

MAGNUM 4 The Magnum 4 is designed for the professional pilot. It has the shortest ground roll of any wing we have flown so far, making for impressively simple launching characteristics. The pilot and passenger are airborne much faster than before, and the glide, speed, and sink rate have been improved over preceding models. Designed for professional pilots, the handling is agile and low-effort, and the same characteristics that make the launch so easy translate to the landing as well. With ultra-precise pitch control and a high resource flare, your crew has never landed so gently. www.flyozone.com

Naviter and Flytec USA are pleased to announce that starting with Software v9.43, the Oudie5 XC/Pro and the Blade will now support FANET and FLARM-out functionality within North America. With this new software, there will be visibility between Oudie5/ Blade users and Oudie N+/Omni users, as well as any other FANET device. Additionally, Oudie5/Blade users will be visible to sailplanes and general aviation aircraft equipped with FLARM receivers. Oudie5 XC/Pro and Blade users are encouraged to upgrade the software and take advantage of the additional safety of FLARM conspicuity as well as buddy flying via FANET. Further info at: www.flytec.com info@flytec.com +1 800.662.2449

: With so many changes happening at the magazine over the last year, I would like to speak directly to current and potential contributors on a few housekeeping items.

As you may remember, earlier this year, we increased our contributor budget by roughly 30%. I hope this increase shows how much we value your contributions and the time you take to share them. However, I have heard that, on occasion, our payment emails end up in your spam folder. We are working to solve this, but in the meantime, please check your spam folders for those emails. I want to pay you!

We send contributor payment emails soon after uploading our publication to print. If you receive a printed copy of the magazine featuring your story and have yet to receive your contributor payment email, please check your spam folder. If you don't find it, please reach out ASAP.

On a related note, if you don't respond to a contributor payment email within 90 days (an extension from what it used to be), the total amount will be considered a donation to USHPA. That’s three months (or one issue rotation) for you to see the email and decide how you’d like to receive your payment or if you would rather donate the amount back to the organization.

Recently, several contributors have asked about directed donations. I love this idea, and we are working to implement such an option. Of course, you can still donate without directing it, but if you want to specify where your donation is going, we have a few options:

• USHPA General Operations

• USHPA Women’s Committee

• Foundation for Free Flight General Fund

• Foundation for Free Flight Site Preservation Fund

• Chapter Support and Site Development Committee

To make a directed donation, simply email me or Maddie Campbell as to where you’d like it to go.

I am incredibly excited about the changes we’ve been making at the magazine over the last year, and I look forward to new options and innovations to serve you better. In the meantime, if you have a story idea, send me a pitch via email. If you have a fleshed-out story with photos, head to https://www.ushpa.org/page/ contributors.aspx and follow our new submission guidelines. I’ve enjoyed working with many new contributors lately and am excited to get to know more of you. Your stories influence, teach, and inspire our community. Thank you for your contributions.

Regardless of whether you’re a member or a magazine contributor, donations are always greatly appreciated. If you’d like to make a donation to USHPA any time throughout the year, visit drop a note to Maddie Campbell at maddie@ushpa.org

Liz Dengler Managing

Editor editor@ushpa.org

Kristen Arendt

Copy Editor

Greg Gillam

Art Director

WRITERS

Dennis Pagen

Lisa Verzella

Jeff Shapiro

Erika Klein

Julia Knowles

SUBMISSIONS from members and readers are welcome. All articles, artwork, photographs as well as ideas for articles, artwork and photographs are submitted pursuant to and are subject to the USHPA Contributor's Agreement, a copy of which can be obtained from the USHPA by emailing the editor at editor@ushpa. org or online at ushpa.org. We are always looking for great articles, photography and news. Contributions are appreciated.

Bradley, Executive Director

Do you have questions about USHPA policies, progra ms, or other areas?

EMAIL US AT: info@ushpa.org Let us know what questions or topics you’d like to hear about!

Interested in a more active role supporting our national organization? USHPA needs you! Have a skill or interest and some time available?

VOLUNTEER! ushpa.org/volunteer

For questions or other USHPA business +1 (719) 632-8300 info@ushpa.org

: As I write, I’m on day 63 of my first 100 in this job. Every day is packed with a combination of the work that is necessary to keep the organization running and the work that can make us into a better organization.

One of the improvements we’re working on is selecting and implementing a new association management system (AMS), specialized software built around a member database. The one we’re using doesn’t work well for us and has high ongoing costs. A better-suited package will help us be quickly responsive to everything you need from us. We know USHPA hasn’t always been responsive and we’ve made changing that a high priority goal.

Next we’ll add a learning management system (LMS). We’ve begun work on courseware for a full pilot training curriculum, starting with online courses for theory and ground school that will complement on-hill training. Led by sports education expert Anna Mack and instructor administrator Greg Kelley, the program’s first products will

be online courses for P1 and P2, since paragliding has the most students, to be followed by P3, P4, hang gliding, speed flying, and instructor training. A small group of our most experienced instructors are participating in this work, and we’ve begun a collaboration with our Canadian colleagues at HPAC. On the side of keeping things running, one of the most important things USHPA does is caretake our tandem exemption with the FAA. FAA Part 103 is the document that lays out the FAA rules for ultralights. Part 103 specifies one person per aircraft, to let pilots take their own risks but not endanger others. Our tandem exemption allows tandem flights but only for instructional purposes, to help a student learn to operate an aircraft with an instructor on board. We apply to renew USHPA’s tandem exemption every two years. We’ve submitted this year’s filing and I’m optimistic that the FAA will renew it again, but please respect the FAA’s intent: we’re only allowed to fly tandems for instruction, not joyrides.

Any advertising or website that even implies the latter can put all tandem flying at risk. If you’re an instructor, please check that your website and promotions conform with this. Also, please remember that you’re required to have a physical copy of the tandem exemption with you during tandems. Because of the potential effect on the rest of us we will be putting teeth in these requests: your USHPA certifications will soon be at risk if you don’t respect these rules.

Similarly, if you’re an instructor or a tandem pilot, please be attentive to executing USHPA memberships and USHPA waivers for all your students. These steps protect you and your assets, as well as your flying sites and USHPA, in the event of a mishap. Because of the risk to the rest of us, of loss of a flying site or financial damage to the organization, following these rules consistently will also soon be a firm condition of keeping your USHPA certifications. I know most of our instructors are already doing these things attentively. Thank you.

All of us who work here are committed to making USHPA more responsive and easier to do business with, for our members, instructors, chapter leaders, and event organizers. Please let us know how we’re doing. You can call Maddie Campbell, our Membership and Communications Coordinator, at (719) 2191588, and you can book a 15-minute Zoom meeting with me by going to: ushpa.org/meetwithjames I look forward to speaking with you.

The United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association Inc. (USHPA) is an air sports organization affiliated with the National Aeronautic Association (NAA), which is the official representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale (FAI), of the world governing body for sport aviation. The NAA, which represents the United States at FAI meetings, has delegated to the USHPA supervision of FAI-related hang gliding and paragliding activities such as record attempts and competition sanctions. The United States Hang Gliding and Paragliding Association, a division of the National Aeronautic Association, is a representative of the Fédération Aeronautique Internationale in the United States.

REGION 1 NORTHWEST

Alaska Hawaii

Iowa

Idaho Minnesota

Montana

North Dakota

Nebraska

Oregon

South Dakota

Washington

Wyoming

REGION 2 CENTRAL WEST

Northern California

Nevada

Utah

REGION 3 SOUTHWEST

Southern California

Arizona

Colorado New Mexico

REGION 4 SOUTHEAST

Alabama

Arkansas

District of Columbia

Florida

Georgia Kansas

Kentucky

Louisiana

Missouri

Mississippi

North Carolina

Oklahoma

South Carolina

Tennessee

Texas

West Virginia

Virginia

REGION 5 NORTHEAST and INTERNATIONAL

Connecticut

Delaware

Illinois

Indiana

Massachusetts

Maryland

Maine

Michigan

New Hampshire

New York

New Jersey

Ohio

Pennsylvania

Rhode Island

Vermont

Wisconsin

Bill Hughes President president@ushpa.org

Charles Allen Vice President vicepresident@ushpa.org

Julia Knowles Secretary secretary@ushpa.org

Pam Kinnaird Treasurer treasurer@ushpa.org

James Bradley Interim Executive Director executivedirector@ushpa.org

Galen Anderson Operations Manager office@ushpa.org

Chris Webster Information Services Manager tech@ushpa.org

Anna Mack Program Manager programs@ushpa.org

Maddie Campbell Membership & Communications Coordinator membership@ushpa.org

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2024)

Bill Hughes (region 1)

Charles Allen (region 5)

Nick Greece (region 2)

Stephan Mentler (region 4)

James Bradley (region 5)

Joseph OLeary (region 5)

BOARD MEMBERS (Terms End in 2025)

Julia Knowles (region 1)

Nelissa Milfeld (region 3)

Pamela Kinnaird (region 2)

Takeo Eda (region 2)

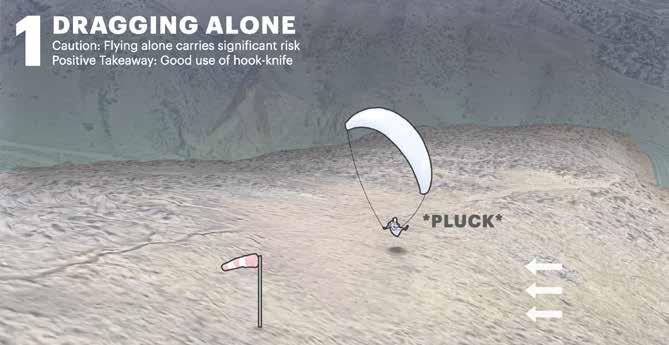

Complicated conditions and the disadvantage of flying alone

: A P2-rated pilot, flying alone this spring at an inland thermal site, went airborne while preparing to launch. The pilot impacted terra firma seconds after being plucked and was dragged through the terrain, resulting in a front-mounted reserve deployment. This accelerated the situation until they became wedged in debris. The pilot was able to use their hook knife to separate from the reserve. This event highlights several concerns. First, flying alone carries significant risk. Specifically, the opportunity to make the launch/no launch decision with other pilots is lost, as is the chance to evaluate the air by seeing others fly. Second, there is nobody to help when an emergency develops. Finally, regardless of location, springtime provides some of the most aggressive and unpredictable conditions of the year. This also highlights the changing environment of recent years and the relatively unpredictable nature of most flying sites/conditions that has become the norm. We are grateful that this incident did not result in anything more than a wrist fracture. Cheers to the pilot who executed the emergency procedure well by using their hook knife to separate from the reserve.

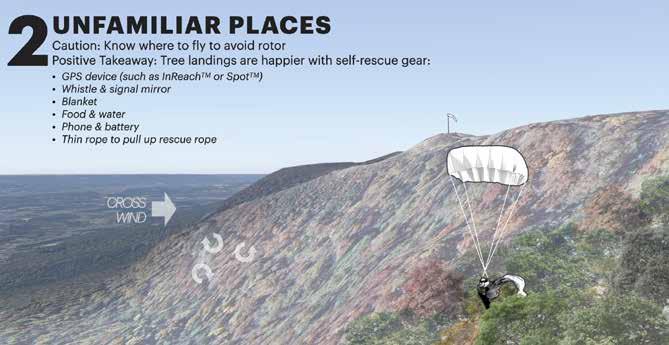

A P2 pilot flying a wooded thermal site landed in a tree without injury. This relatively new pilot received a site briefing, but due to a significant language barrier, clarity was lost. This is a genuine concern as we often host pilots from other places. Though several local pilots were out flying on the day, the pilot navigated into an area characterized by rotor in a crosswind. Pilots are reminded to chat with locals to figure out which portions of a flying site present rotor and which do not, depending on wind direction. Google Earth, flight tracks loaded to the Internet, and videos of others flying the site are additional resources to study the potentially dangerous areas. Some prior preparation using these tools might have prevented this incident. In the event of a tree landing, there is a long list of items that all pilots should carry. This list includes but is not limited to: a whistle, signal mirror, blanket, food, water, phone, phone battery, emergency locator, a way to securely attach to the tree, and, finally, some line that can be lowered to bring up a rope that will serve as a descent mechanism. Although dental floss is anecdotally referenced as such a tool, it often doesn’t work. 5 mm Perlon is a reasonably compact style of usable line/rope for

this use case. Thankfully, tree landings like this one are often characterized by a happy ending with no injuries, though there are no guarantees that this will be the case.

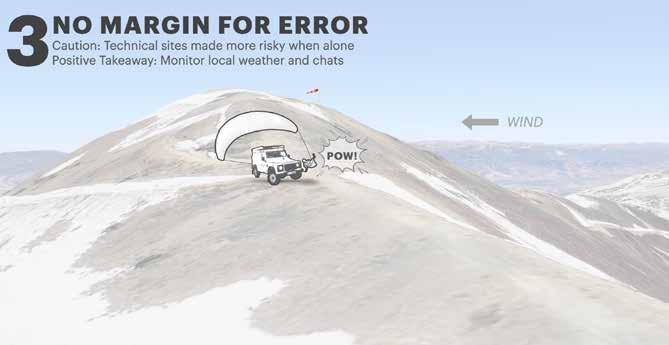

A pilot standing on launch preparing to fly at a lee-side thermal site encountered a rogue gust that caused them to be plucked airborne. The pilot had no wing control and impacted a parked car. The pilot suffered a sprained ankle. This was another case of a pilot flying alone. There are many reasons

why flying alone puts a pilot at a severe disadvantage. Also, we remind pilots who frequent east-facing sites exposed to the usual west-to-east jetstream wind of the western U.S. to monitor forecasts, live weather stations, and group chats to determine which days are flyable. It can generally be presumed that at any popular site, dozens of people will show up on a day with a good forecast and nice conditions. Pilots who find themselves alone on a takeoff should use extreme caution.

by Martin Palmaz

: Flying sites are fundamental for getting pilots in the sky, yet creating and maintaining them can be the most challenging part of fostering a healthy flying community. Fortunately, Colorado Springs, Colorado, has a progressive approach to growing the city and has been a supportive partner in exploring flying where appropriate. The city has wide appeal for outdoor enthusiasts and athletes since it is home to the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee and is adjacent to abundant outdoor recreation in the Pikes Peak region.

Currently, Colorado Springs has two hike-up sites that require advanced skills. Therefore, a new site with high visibility and training potential could drastically change access and growth within this rapidly growing metro area. However, establishing new sites takes time and requires consistent engagement. Over the past 14 years, as the USHPA representative in the community, I have established relationships and the necessary community engagement for getting free flight incorporated into the city’s parks and recreation department’s master plan. With that complete, it is now standard practice to invite USHPA to participate in future planning of open space within city limits.

Colorado Springs acquired Blodgett Open Space in 2001. The land was opened to hikers and bikers under the original master plan, but the open space was marred by misuse, overuse, illegal social trails, and competing recreational use over the years, and the parks and recreation department decided decided that they should take action to improve the area. In 2023, the parks and recreation departmen began a new master planning process to handle the changing demands on the open space while preserving wildlife and habitat. This planning process was USHPA’s first official invitation, and I, as USHPA’s representative in the community, enjoyed participating in the Stakeholder Action Committee for approximately 18 months during the plan develop-

ment and public input process.

The City Council did receive an appeal from a small contingent of local residents about the revised master plan including the new recreational uses. However, the council ultimately voted to deny the appeal and move forward with the new plan to develop the area for more sustainable recreational use that also helps protect the habitat and wildlife. The estimated budget for all open space improvements is $7 million.

Over the next year or two, the city will begin the first phase of work. They will build single and multiuse trails (hiking, biking, and launch access), bury power lines (which block access to the LZ), and create signage that explains flying rules and protocols. Of course, due to the proximity to the Air Force Academy (AFA) and its cadet sailplane training program, this site is highly sensitive and faces intense scrutiny, so defining strict protocols and posting the associated signage is an essential aspect of opening this site. Though a designated launch and LZ have been identified, the site will remain closed to flying until some of these improvements are completed. There is no timeline for the flying site to open, but we hope it will be by the 2025 flying season.

The second phase of development for the open space is still to be decided. The adjacent land is approximately 100 acres and requires extensive reclamation of an old quarry. Once the quarry reclamation process is complete, the city will begin the planning process for phase 2 (including public input). With USHPA’s input and responsible use during phase 1, this will hopefully include additional launches and LZs, that may also include hang

gliding appropriate landing options. If approved, this area would likely be better for training and flying than the other local options.

Training is essential for growth within a sustainable flying community. Unfortunately, land purchased through the Trails, Open Space & Parks (TOPS) program doesn’t allow for commercial training activity, and teaching will not be allowed on the initial site. However, with careful planning and continued community engagement, we hope that the phase 2 acreage can be acquired outside of the TOPS program to allow a commercial school to be established.

If a school can be established, it will be subject to strict protocols similar to the phase 1 site. Additionally, there will be an approval process for instructors wishing to apply for a permit to teach on either

“Establishing new sites takes time and requires consistent engagement.”

Looking south from launch showing quarry reconstruction in progress.

phase 1 or phase 2 land. Once the site has officially opened and some history has been established with the city and AFA, more details about this process will be made available. Responsible flying activity and good relations are essential in seeing this site

potential training site) will increase the visibility of free flight in Colorado Springs and strengthen USHPA’s standing and partnership with the city. This is an exciting evolution, and I am incredibly pleased to see it come to fruition, remain USHPA’s liaison

by Sofia Puerta Webber

Sofía is the creator of Shiwido™ and a writer, wellness consultant, yoga and mindfulness teacher

: This is an invitation to be aware of our gear, transform old wings into something useful, and donate gear to bring joy to others.

While studying for a B.A. in communication science and journalism at university, I traveled to the Amazon region of Colombia for eight months. My job while there was to do social research about the impact of illegal harvesting (coca, amapola, mari-

juana, and poppy flowers) on Indigenous communities, especially children. It was an enlightening and challenging experience. When I returned from the forest, I decided I wanted to help find a way to “Save the Amazon” by creating awareness about how our actions and decisions impact the planet.

I created a toy/instrument inspired by the colors, sounds, winged creatures, and the magic of the Amazon rainforest. When you spin the toy, the colors are vibrant, and it makes a sound like the wind. I called the toy Shiwido (The Magic Land of the Rainbow),

and it became my “magic wand” to inspire others to learn about the Amazon. I put together a workshop that blended yoga, mindfulness, storytelling, and dance and visited several schools, museums, and libraries in Boston, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Colombia to spread the word and help educate the public.

I always carry Shiwido with me, even in my paragliding harness, and I discovered how great it is during para-waiting. My fellow pilots enjoyed spinning it and would tell me it was excellent exercise for strengthening their arms and upper body. So Shiwido became an educational toy with exercise in mind, and I trademarked it in 2007.

So how does this relate to recycling paragliders? Early on, I found a slight durability issue with the toy; kids were playing hard with Shiwido, so I needed to find better quality materials; something softer to the touch, more colorful, and something that could make

a better sound when flown. Right in front of my eyes was the ripstop nylon from my old paragliders! This amazing fabric was perfect; it was specially designed to withstand the stresses and strains of paragliding flights. It was strong and durable while being resistant to water, tearing, and ripping, and it even had some UV protection.

I had been flying for quite a few years by this point, and I had a bit of experience working with the glider fabric from repurposing my old gear. I have owned ten different wings in my pilot life, and I especially remember the feelings I had when I dumped my first glider into the trash. I gazed at it for a few minutes, feeling that something was off. I felt like I was somehow abandoning my old loyal friend who had flown with me since my first solo flight in 1998. My dear purple UP was too old and unsafe to fly, but I had a hard time letting it go. I grabbed some scissors and cut out a few pieces to create something to honor its

To donate your gear to fellow pilots:

Wings for Them

www.ailespoureux.com/?lang=en

Philippe Trautmann (France) ptrautma@yahoo.com

Promotion of Free Flight in Cuba

Chris Arnu (Germany) chris.arnu@gmail.com

Wilder Núñez (USA) wildernd87@gmail.com

ParaCyclage

paracyclage.com

Ana Aguilera paracyclage@gmail.com

Miolento www.miolento.com

Elisa Hensel hello@miolento.com

Banzai Sports Gear

www.instagram.com/banzaisportsgear

Omar Rogel teacheromar82@gmail.com

Shiwido™ www.shiwido.com/shiwidotrade.html

Sofía Puerta shiwido@gmail.com

existence. After a few days, I made a couple of windsocks, wind straps, picnic blankets, decorations for parties, and an anklet that I wore for many years. Knowing how perfect the paraglider fabric would work for Shiwido, I put together a little campaign to get some donations: “Let your old wing fly with a new shape.” Pilots from Torrey Pines Gliderport in San Diego and retired pilots from around California offered solo and tandem wings. With so much fabric, Shiwido took off. Now, it is handmade in the U.S. using recycled materials from paragliders and parachutes. Shiwido is like a flag that reminds us we live on this planet together. I promote clean-ups on the oceanside and nearby parks, and we participate in tours and celebrations that promote zero waste.

I am deeply concerned about the amount of waste we produce and the impact of our actions on the planet. I truly believe we can contribute to a cleaner environment by implementing the four R’s: reuse, reduce, recycle, and recreate. Old gliders, ready to be trashed, are more than a piece of fantastic fabric. They carry a story of beautiful landscapes, flights, and adventures, so I find ways for people to continue enjoying them by creating durable carry-on bags for helmets, radios, and electronics and colorful bags for yoga mats. But I’m not the only one working to reuse these materials.

Though I contacted several hang gliding, paragliding, and parachute factories to learn more about recycling materials, they have yet to respond. However, I kept looking and found amazing people doing extraordinary things with older gear.

Elisa Hensel, a paraglider pilot from Germany who lives in Brussels, is the creator of the company Miolento. Her first donation was a glider from 1991 that a friend had in storage.

“Pilots don’t want to throw away their old wings; they still love them,” she says. “So I tell them, if they give me the wing and tell me what they want, I will create that for you.”

Around 2020, Elisa started making fanny packs from recycled wings, which are incredibly popular; customers can even choose their color combinations.

In addition to the fabric, she uses the lines and risers and keeps everything for future use. She makes all kinds of bags, hair scrunchies, and bracelets, and is considering making jackets, earrings, and other accessories.

Though Elisa works full-time in political affairs in Brussels, she calls Miolento her side love. She says, “Using recycled paragliding wings is nice because you get to do something with your hands and create things.” Her dream is “to give a second life to as many paragliders as possible and, hopefully, one day we can mechanically and chemically recycle the old wings and make new material so we can close the loop.”

Omar Roger is an English teacher who lived in Atlanta, Georgia for 30 years. When he moved back to Mexico, he created Banzai Sports Gear in San Miguel de Allende. A friend told him about paragliding

materials, and he crafted his first fanny bag, intended for ultra-marathoners and hikers to carry food, a flashlight, first aid supplies, and a windbreaker.

An ultra-marathoner since 2015, Omar confesses that his first design was very uncomfortable. But he added a strap to provide better support and reduce bouncing. “I searched for the possibility of manufacturing it in Mexico, but finding someone who could make it for me was not easy,” he says. “I finally found an upholster who helped me to make a great prototype that I use and sell to sportsmates.” He also makes backpacks and will soon have dog harnesses and leashes for sale.

Banzai’s motto is change, adapt, and grow. Oscar believes “if we are in nature, we need to be more aware of nature.”

Ara Aguilera is a fashion designer married to a

paraglider pilot. She created ParaCyclage in 2019 when she moved from Argentina to Interlaken, Switzerland. Her first glider donation was so old that it was covered in mold. However, after washing it, she found it was a beautiful pink that inspired her to design a colorful jacket. She gave this glider a second life.

Ara says that ParaCyclage helped her reconnect with her soul and that sewing is an art form that allows her to express happiness. Ara has an alliance with NOVA that donated 80 paragliders to make 300 products like sports gear, fanny bags, leashes for phones, hammocks, and computer covers. Ara donates gliders that are still airworthy to pilots in other countries.

Philippe Trautmann has been flying for 26 years and lives in Nemours, 50 miles south of Paris. About five years ago, he and some friends founded an NGO called Wings for Them (Ailes pour Eux), which sends reused paragliding equipment to underprivileged pilots worldwide.

All the equipment they receive is provided through donations; out of the 200 wings they receive per year, about 50 are still flyable. Since its establishment, the organization has received donations totaling more than 650 wings, 300 harnesses, 200 reserves, and 250 carrying bags as well as helmets, flying instruments, and radios. “We make sure the functional wings are provided to underprivileged pilots in 16 countries: Colombia, Tunisia, Montenegro, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Cuba, Macedonia, Albania, Pakistan, Morocco, Algeria, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, Brazil, Afghanistan, and New Zealand,” says Philippe.

Philippe notes that about 380 wings have been recycled, thereby escaping waste or incineration. The non-profit supports a network of 12 recyclers who take the non-flight-worthy gliders and sports gear to create items such as hammocks, shelters, outdoor gear, and harnesses. His network of recyclers also creates objects, shelters, and gear used for humanitarian activities such as first aid airdrops with the support of the Humanitarian Pilots Initiative (HPI).

Chris Arnu lives in Karlsruhe, Germany, and became a pilot in 2004. He went to Cuba for the first time in the late 1990s and continues to visit Cuba often; now, he enjoys flying there too. Knowing how

difficult getting gear can be for other pilots, Chris dislikes it when a flyable paraglider is trashed simply because it’s a little old. “It can be used for ground handling and learning purposes in places like Cuba,” he says. Pilots there showed him the gear they were using, and it was in terrible condition, some of which was unsafe for flying. They were even using a reserve parachute from the army. The interaction motivated him to publish a short story on a German paragliding forum, and people started to contact him to donate gear.

“I collect gliders and other items. If gliders are damaged, I can have them fixed for free by an expert in stitching,” says Chris.

Little by little, the Promotion of Free Flight in Cuba project took off. They now accept harnesses, paragliders, helmets, flying suits, parachutes, bags, and varios; everything but radios (because of the political situation in Cuba). “As crazy as it sounds, they have to yell at each other in the air or take the students on a tandem flight, but there are very few tandems,” says Chris.

Chris teamed up with a close friend, Wilder Núñez, who was born in Cuba and currently lives in San Antonio, Texas. He started as a skydiver, then became a paraglider pilot in 2006. Chris and Wilmer take the donated airworthy equipment to Cuba themselves. Wilmer explains, “Cuba needs a lot of things, but with paragliding, we can bring some happiness and enjoyment. This is our passion, and we can help our people and the Cuba Free Fight Federation.”

Being part of a sport that uses such niche fabrics and materials offers the opportunity to be creative. It would be fantastic if manufacturers took responsibility for the end-of-life disposal or recycling of their products by managing the collection and recycling process. Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) can include requirements for product design to facilitate recycling. Perhaps one day, manufacturers and free flight organizations could offer promotional items made from recycled materials or discounts towards the purchase of new equipment in exchange for returning old wings for recycling. It would be wonderful to create an environmental consciousness within our clubs to contribute to conservation efforts, which can benefit individuals and promote social action. By recycling old wings, we can join a circular economy supported by the paragliding and hang gliding industry and community.

: Last winter (2023-2024), the USHPA Women’s Committee sent out a survey to all female-identifying USHPA members. Although our presence has grown in recent years, women pilots are typically in the minority in free flight. It is also less common for us to pursue acro, comps, or careers in the sport than our male counterparts. Some women may not stick around in the sport for as long as their male cohorts. Curious to know why, the Women’s Committee sent out a poll, and the lady birds responded in droves; over 250 pilots submitted answers to the survey. Of course, the first thing that was apparent from the results is that the passion is clearly alive and well among female pilots! In the survey, about one-quarter responded that they fly “as much as humanly possible … flying is life!” Participants averaged a 4.2 out of

5 when rating the importance of flying in their lives, with nearly half considering flying “extremely important” and 78% traveling beyond their home sites to soar.

Beyond confirming our love of flying, the committee aimed with this survey to examine retention and progression, understand preferred learning environments, and identify barriers that hinder women from pursuing more advanced ratings or skills. Some common themes cropped up among the responses. From the survey, it was clear that many feel they (either routinely or at some point in their flying career) experience gender-based challenges. While respondents generally feel supported, over 60% reported experiencing and/or observing sexism (both overt and subtle) or microaggressions within the flying community. In the comments, two significant patterns

FEW TIMES PER YEAR OR LESS

DON’T FLY ANYMORE

emerged throughout the survey. Women consistently miss out on mentorship and learning opportunities that are more readily offered to their male peers, and many feel as if their actions are scrutinized more than men’s. Though all pilots experience both phenomena, the frequency with which they occur for women is a hindrance.

Finding consistent mentorship is a global challenge, but the sheer volume of comments demonstrates how female pilots are disadvantaged. Women tend not to gain access to informal learning moments in the ways that men do, which, over time, can create a significant knowledge gap.

“It’s frustrating that the locals mainly talk to my husband. Even after learning I’m a pilot, they don’t engage with me much,” one woman stated. Another offered, “At times, I fly with less beta than I’d like because it was not offered by male pilots, whereas my husband would regularly get invited on XC missions.”

So much of our education beyond a P2/H2 comes via

informal mentorship. Lack of engagement really limits the learning process. “It does create one more micro-hurdle when trying to learn and grow … there is so much information to learn in this sport, and every ounce counts,” another pilot said. Even small hurdles stack up to create not-so-small disadvantages over time, but certain environments can help to address this gap.

An overwhelmingly positive theme that arose from the survey was the value of women-specific spaces. From fly-ins to group chats to clinics and beyond, these environments allow female-identifying pilots to learn with a cohort. For a deep dive into women-only chat groups, check out Liz Dengler’s article in the November 2022 Cross Country Magazine, “Let’s Connect!” “The only chat group I feel comfortable asking questions in and going for help is the Lady Birds Telegram channel,” one commenter wrote. Whether discussing something specific to our gender, such as pee systems for long XC flights or seeking insights that may not be taken seriously in a general chat, these spaces unlock a safer and more friendly progression for many flying femmes.

Women-only spaces also connect new pilots with female role models and networks to leverage throughout their progression. Another survey respondent wrote, “I would LOVE to see more intentional spaces created for just women! There is nothing more empowering than being taught by other women.”

To address the mentorship gap, the Women’s Committee applied for USHPA funding to promote men-

torship of female-identifying and nonbinary pilots. The request was approved in late 2023 and has already been put to use at events such as the Woodrat Women’s Fly-in held in June 2024. Thanks to the supplemental funding, event organizers can bring in experienced mentors who foster a supportive environment for lady birds to spread their wings. These inclusive mentoring opportunities make advanced skills and competition flying more accessible for women, by women, without leaving anyone out of the circle up at launch.

One survey question examined pilots’ interest in various types of events. The left panel shows baseline interest, while the middle panel shows interest if the activity were specifically for female pilots. In the third panel, items in green show a higher interest in women-specific programming.

Free flight requires a strong mental game. A frequent theme in the survey was that women feel scrutinized more heavily than their male counterparts, which can erode confidence to the detriment of their flying.

One woman wrote, “I have to prove myself in ways that get in the way of my enjoyment and progression. Male pilots are encouraged to push themselves, while female pilots are encouraged to make conservative decisions about gear and progression.” A second said, “It can decrease my perceived competence, increase my (irrational) fear level, discourage me, reduce my ability to make good decisions, reduce my desire to engage with the sport and my community, and make me question my value as a part of the sport.”

More comments reinforced the theme: women feel as if we must constantly prove that we belong and that our mistakes reflect poorly upon all women in the sport. That’s a lot of pressure! This can make it easy to botch a launch or even bail on flying.

Expert pilot and weather guru Lisa Verzella from the Women’s Committee offers her secret sauce for overcoming this. “Everyone has strengths and weaknesses in flying; learn to focus on your strengths at launch. Folks seem to respect that,” she says. Sarah Lockwood, another leader in the women’s pilot community, understands the challenge of finding a confident head-

space, too. “It is so normal to experience self-doubt,” she states. “In a society that tells us we need to be careful, ask permission, and second-guess ourselves from a young age, becoming fully and completely pilot-in-command is no small accomplishment. When you stick with it and truly understand that you belong and are capable, this can positively impact your entire life.”

We can’t necessarily control others’ perceptions of us, but it can help to know we aren’t alone in feeling as if we are under a microscope. The magic of female-dominated spaces can occur as you move beyond them. It is easier to build up fortitude in a safe and supportive bubble; then, when you leave the fold and feel those critical eyes upon you again, you have a more deeply rooted inner confidence to tap into.

At times, education for women might come with strings attached. Whereas men might freely offer advice to male peers, it can be less cut-and-dry for the opposite gender. “It seems hard to find a mentorship that doesn’t come attached with some type of desire for more than a mentorship,” one pilot observed. Establishing trust with a mentor or instructor is foundational to the learning process, and instructors hold a position of authority over their students. Misusing that authority violates USHPA’s Anti-Harassment

Policy and the SafeSport Code of Conduct. However, as more than one respondent noted, “It is difficult to advocate in these situations.” Challenging an authority figure does not typically benefit the student or mentee, who has everything to lose and may fear retaliation. So, how can we proactively avoid these types of issues altogether?

Increasing the number of women who instruct, guide, and offer tandem flights might be the solution. One pilot described how “having a school with a female instructor helped me feel comfortable from day one.” Research consistently demonstrates that sexual harassment declines when more women move into management positions. Although it isn’t unheard of for a woman to harass, it is statistically much less likely. A stronger female presence in our instructor, tandem pilot, and admin pool would organically address these issues without placing the onus on students or mentees to either file a report, deal with it, or leave the sport.

The Women’s Committee has noted a high demand for continuing education opportunities for female pilots. Survey respondents were asked how likely they were to participate in various clinics and events. They were 24% more likely to respond with “Most Definitely” (5 on a 1–5 scale) if the event was for women only. We saw the greatest demand for female-specific flyins, ground handling clinics, thermalling clinics, and

Mentors at the inaugural Woodrat Women’s Fly-in, held in July 2023. Left to right: Julia Knowles, Lisa Verzella, Kari Castle, and Summer Barham.

beginner XC clinics. Interest in SIVs and international tours was quite notable, too. We see a huge opportunity for organizers to consider adding courses specifically for female-identifying pilots, as the demand is high.

The Women’s Committee is currently developing resources to promote professional development, such as clinics and education on competition training. Stay tuned for details from the committee later this year!

We all wish we could fly more. Women reported universal barriers, such as injury or the cost (both in time and dollars) of staying current. Some limiting factors, however, were gender-specific. Many women are grounded by child care demands after starting a family. Children often impact mothers’ participation more than fathers’, with moms often feeling heavily judged for continuing to fly.

“I would like to stop having the shocked conversation about being a pilot and a mother, which I never hear the dads have,” one respondent said. Judith Mole explores this subject in two episodes of The Paraglider Podcast, titled “Flying when Pregnant” (April 13th, 2016) and “Flying Mothers” (May 5th, 2016). Mole interviewed four European pilots who were criticized for flying after or during their pregnancies.

“Oftentimes, at the landing field, people would be like, ‘Are you crazy? What are you still doing flying?’” Elli Torro recalls. After consulting with a medical professional, she continued paragliding into her third trimester, but only when conditions were perfect.

The choice to fly as a mother is never taken lightly. Ruth Churchill-Dower, another interviewee, summed it up nicely: “It is absolutely every woman’s own decision to make that call for themselves, depending on who they are, where their skillset is, what their level of confidence is.” Hopefully, women feel empowered to make their own well-informed decisions to fly during or after a pregnancy. Even the most well-intended critics won’t offer much that an expectant mother hasn’t already considered for her most precious cargo.

This survey also highlighted the overwhelming demand for gear that actually fits women. Many of us struggle to fall within the weight range of even XS gliders, often ballasting up or sacrificing speed and safety while we sit at the bottom of the range. Harnesses don’t always fit our figures well. Comments abounded: I counted over 30, even though the survey did not include any specific questions about gear. One participant wrote, “It would be nice to have R&D done specifically for and by female pilots.” Another noted, “If we had more gear available for women’s bodies, I think the sport would change for women

Pro Tip: NEO makes an excellent rucksack in a range of women-specific sizes that may help our hike-and-fly lady birds!

significantly.” A clear opportunity exists for manufacturers to tap into this rapidly expanding segment of the market!

This survey provided valuable feedback to the USHPA Women’s Committee and is already driving changes that are sure to benefit not just female pilots but the free flight community at large.

We thank each of the 251 pilots who responded to this survey from the USHPA Women’s Committee. Lady birds, stay tuned for more development of women-specific spaces and resources later this season. Committee chair Violeta Jimenez notes: “Our committee was created to support female, trans, and non-binary pilots. If you have questions or concerns you’d like to see addressed or have ideas and want to help, please get in touch.”

You can contact the USHPA Women’s Committee at womens_committee@ushpa.org.

: Mid-afternoon is a bad time to fly a paraglider close to the desert floor. My team had been flying well, yet we were flushed to within a few hundred feet of the deck. Life and paragliding aren’t fair. Eighty minutes earlier, the milk and honey were flowing as we linked up in the freezing air over the Lucerne Valley and pointed east. Flying 10,000 feet above the alluvial fans spilling out from the San Bernardino range, we stayed tight to one another, marking climbs and shifting to better glide lines for 20 miles. Our route then fell through a trapdoor of sink, and the jig was up.

The radio crackled out one safe landing after another as the heat wormed its way through my layers, and the world shrank into a dusty beige box. Backyard dogs took notice and voiced their resentment. The ground was closing in, but I was content, as the previous hour had been spent in perfect flow. The sinkhole grounded half the group, but four of us hung on and regrouped above the town of Joshua Tree. When we landed just after sunset hours later, following a jaw-dropping 40-minute final glide, there was nothing else I could ever want to do or hope to become.

This trip to the Mojave was in the middle of May 2024, hosted by Chris Garcia of Convergence Paragliding. After the trip, I asked Garcia, “Why the Mojave?” He didn’t hesitate: “It’s my favorite place to fly in the whole world. It shaped me as a pilot, and I started Convergence to share these special places with others. The Mojave demands your full toolkit, but it isn’t for everyone. You don’t have to be an expert to fly there, but you need to make good decisions. The landscape in parts of that desert is the most beautiful I’ve ever seen.”

I had previously met two of the guides, Neal Michaelis and Chris Lorimer, but it was my first time getting to know the others, Reavis Sutphin-Gray and

Marcella Uchoa. It was a treat to learn about Marcella’s beloved Sertão flying scene in Brazil. She lights up when she describes the long, demanding days in the air and the incredible hospitality of the locals. Reavis is an institution, a teacher and student fluent in forecasting and tech. He steers pilots around the sky while tracking weather, airspace, and traffic from the top of the stack.

The long drives up the hill through the piñon and yucca gave pilots time to swap stories and bond as sisters and brothers in the desert crucible. After ten days of flying in the Mojave, we emerged with a blueprint of four categories of skills and mindsets that I will forever work to improve: preparation, discipline, resilience, and teamwork.

The Mojave Desert lies in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada, Tehachapi, San Gabriel, and San Bernardino mountains. The heat center of this plateau creates a diurnal low-pressure zone, pulling coastal air through the passes towards the Arizona and Nevada borders. Cloudbase is often above 12,000 feet, giving pilots a couple of miles of headroom to chase down the convergence lines.

The records of air exploration over the Mojave start as early as the 1930s. The Southern California Soaring Association held meets at the Arvin-Sierra glider field on Tejon Ranch in Kern County. Though there are no specific flight reports, there are mentions of those pilots hucking over the mountains into the desert—this was likely the beginning of Mojave free flight.

Chris McKellar enjoying the extra legroom at cruising altitude near Barstow. Photo by Marty DeVietti.

Gus Briegleb started his soaring school at Rosamond Dry Lake (which became Edwards AFB) in 1940, though it was shut down by World War II. After the war, he bought some land from the military at El Mirage lake bed to get the soaring center going again. El Mirage sits right underneath one of the main convergence lines, hence its notoriety continuing through present-day free flight.

In September of 1955, British sailplane pilot Eric Wynter made the pilgrimage to experience a flight with legend Gus Briegleb at the El Mirage lake bed. His description in the June 1956 issue of “Sailplane and Gliding” magazine cannot be improved upon:

“We settled into a steady ten up. Everything was on such a vast scale. From on high, it appears as a brown expanse spread with black stipple which forms vague

square patches, some isolated, some overlapping, like an abstract design. Right beneath us rotated one brilliant green square like a postage stamp. Close to the alfalfa, I could see the foot of the dust devil at the source of our thermal, a shadowy umbilical cord moving just perceptibly across the ground.”

In the 1980s, a band of hang glider pilots figured out how to fly deep lines on their rigs. A pilot who spent years mapping the Mojave was “Fast Eddie,” described by my contacts as “a cornerstone of desert flying” and “the most prolific retrieve driver, probably ever.” He describes his crew “driving around using the Benchmark books and noting the location of triggers, landings, powerlines, everything. There was no GPS—we needed to know that we could land out somewhere [safely].” Eddie remembers Herb Seidenberg, Tom

Truax, and Tony Deleo as major contributors to this desert exploration.

Jonathan Dietch, desert aficionado, hang glider pilot, and another pioneer of the area, emphasized the need for self-sufficiency. “You’d have to hitchhike out to find a phone. We set up a 1-800 number you’d call to leave your location for the retrieve driver.”

Even with all this prep work, in 2024, we still needed to do our homework and know the landscape before stepping off the hill. I discovered I couldn’t use my instruments’ full capabilities when flying really active air and couldn’t use one hand to zoom in on my screen. Since I hadn’t memorized the towns and highways, I wasted half an hour flying at the wrong landmarks.

The flora of the Mojave is cruel and will bite careless pilots; I brushed a gloved hand against a cholla and felt a spine pin the fabric to my knuckle. Can you spot

the Hawaii pilot? He’s the one stepping on his own hand, trying to dislodge the cactus without attracting attention, only to spike himself through the shoe.

Desert veterans like Gavin Fridlund have seen plenty of launch carnage and emphasize that the Mojave toolkit includes solid fundamentals and respect for the environment. In 2017, Gavin recognized that modern gear would allow for renewed exploration of this area, which had previously been challenging to fly on paragliders. In one incident during his explorations launching at Ord, he felt an ominous lull. Sensing that the sea breeze was about to shut them down, he powered down the hill, smashing through sharp foliage before finally separating from the terrain. A yucca spear lanced the webbing of his left hand, the tip exiting at the wrist. In the desert, it is best to dial in launches and choose the run path carefully.

Flying the Mojave can be spectacular but requires discipline to protect safety margins. When considering a risk management strategy, dust devils command our full attention. Dietch recalled several occasions over his years flying there working a ripper down low when a stealthy dusty emerged underneath: “So I’m climbing, minding my own business when suddenly my face is getting sandblasted by pea-sized gravel.”

This phenomenon was confirmed when Reavis reported following his highest ground speed into a climb over a dry lake bed. He looked down to observe the trigger and saw a dusty shifting up through the gears. There is no way to enjoy the middle of the thermic bell curve without brushing up against the outliers, which is why we stayed away from the ground.

Ninety minutes after Reavis pinged out over the lake bed, I had my own encounter with a dusty. We had flown towards a convergence line north of Cajon Pass, but the thermals were broken and turbulent; the good air was already north of us, and we were quickly grounded. As I ran to the glider, one tip shot erect, whipping in tight circles, pulled by a malevolent puppet master. I tackled the mess into submission, protected from the pelting debris by my winter attire. In this environment, if forced to land in the heat of the day, you must assume dusties are nearby and minimize the time you’re exposed to the threat.

The hazards of overdevelopment can be avoided if a pilot so chooses. Clouds build on a continuum, and if we decided to fly the marginal days, we could monitor the sky and move towards safer areas. The instability is a double-edged sword that births cumulonimbus and gust fronts but also gives the potential for long-distance flights. Finding the balance is up to the pilot in command.

During the clinic, Reavis taught us to work towards expanding our “envelope of expertise” by improving our forecasting and observation. The Mojave is ideal for this training since the mountains are separated by wide areas of flat terrain, giving escape options. This is not to say that the clouds are benign. The high base and vast heat reservoirs

give thermals tremendous momentum, so the “45-degree rule” that normally keeps us out of the white room might be adjusted to a “20-degree rule” on powerful days.

I saw some great piloting from both the guides and participants, staying calm under pressure, accepting setbacks, and focusing on the factors within their control. Neal was the leadoff hitter for our first flight. He lost hundreds of feet immediately, but when he showed us the first sign of positive air, I joined him in the thin, sharp cycles. A weak frisbee eventually pinged me out, and the last I saw of Neal was the speck of his canopy where I assumed he was

landing. Forty-five minutes later, he was high, leading the group down the range. He related that, “I was fine with landing out. You have to plan big and imagine what you could accomplish with the day, but you can’t be attached to the outcome. I’m going to keep trying my best all the way to the ground, but if you want it too badly, that’s when things can go wrong.”

Two days later, Reavis launched first followed shortly by Neal and Andrew. The trio searched impossibly low before Neal and Reavis landed near the Mitsubishi cement plant. Andrew stayed aloft, clawing at scraps, inspiring the rest of us to snap out of it and get off the hill. The two of us were soon isolated and critically low when he called out a thermal directly behind me; this climb let us connect back to the

The high terrain behind Blackhawk turns on before the desert floor. Near Blackhawk launch looking south past Big Bear Lake. Photo by Marty DeVietti.

The I-15 corridor mainlines California’s money into the Vegas Strip. Marty DeVietti and Chris McKellar beating the odds. Photo by Marty DeVietti.

group and stay in the game until the guides could relaunch. Andrew’s willingness to dive into tough air and keep working at it was the crux move of the day. When I climbed into the van seven hours later, my mind replayed his efforts and the work of all my teammates who had helped to get the show on the road after a difficult start.

Marcella shared loads of knowledge about team flying, but what stood out to me was her description of changing one’s mindset. In her record-chasing teams at home, they speak of “the flying organism.” Every decision made by the individual should improve the success of the team. Instead of gliding above and behind, we get on bar to catch up and start providing information for the others. Instead of waiting on launch for the day to properly turn on, we get into the sky and increase the team’s chance of finding a climb.

This doesn’t mean that everyone flies the same. The goal is to use individual strengths at the correct time to gain small advantages for the group. I was succeeding in staying off the deck, so I chose to launch early, figuring it would be more helpful to get another wing in the air sooner rather than later. By contrast, my distant observation is relatively poor, and I leaned on the other pilots to spot signs of lift down the course line.

Marcella was also our speed-to-fly advocate, encouraging us to leave climbs as they slowed toward cloudbase. Back at the Lucerne Market, she put it bluntly, “Guys, it’s not necessary to take these climbs above 13,000 feet. Why are we wasting time freezing up there dodging clouds when we could be making better distance in the lower air?” We mumbled agreement while looking at our shoes. I was too embarrassed to say aloud, “But going as high as we can is fun…”

The magic of team flying is that when you commit to the process, you feel the joy of everyone’s flights, even if you stumble and land early. Team success cannot be separated from individual actions, and that’s pretty cool. The more we share, the more we have.

Crux

The fourth day was forecast for south winds and good lapse, with afternoon overdevelopment possible over the highest terrain. As we connected to the Ord Mountains, I failed to quickly recognize when my line went bad. By the time I recovered, the lead pilots were crossing Highway 40, but the group was splintering apart in shady, booming, and active air. Reavis was on the radio vectoring us to the waypoint, and

for the only time of the trip, his voice carried a hint of tension. Then came the call of a reserve deployment. For several minutes, there followed a remarkably calm conversation between Reavis and Andrew, who had thrown near cloudbase when a dynamic collapse recovery wound him up in riser twists. His long ride ended with a good landing, uninjured, and relatively close to a road. Reavis followed him down, and someone asked for the strategy: Should we pull the plug? Reavis replied no, to stay high and away from the ground. Chris announced the plan to meet up in the mellower air north of Route 40, and we continued with no lapse in leadership.

The team pushed north another four hours, flying into the low, late light of a broad valley etched

through with erosion braids. I touched down on the hard-packed shoulder of the main wash. Heavy silence rules this country, and the ringing in my ears was interrupted by a short exchange with a fellow who had been watching from his truck.

Our retrieve team rolled up shortly after his departure and continued north, plucking our last pilots from the wild terrain. Chris had crossed Ibex Pass into a multicolored drainage erupting with mineral outcroppings, and with a bit more effort, he could have dropped his wing directly onto the bank of one of the hot springs nearby. These moments are one of the great gifts of free flight when the team is reunited and we share these outrageous places.

A question always worth asking is, “Why do I fly?” My answer brings me back to a handful of days over the years that have been transformational. These are the experiences of joy, surprise, and being grabbed by the scruff of the neck and thrust face-to-face with life. I used to fear that I would always crave bigger, better, wilder flights and that the path would not be sustainable. I feel at peace now, being fulfilled by paragliding. I don’t know how many other perfect moments await me, but it doesn’t matter anymore. I’ve landed at dusk deep in the Mojave with my team, and that’s all I will ever need.

Pagen

: Most of us know and love thermals in all their multiple shapes, sizes, and strengths. Perhaps thermals are the one factor in flying that pumps the excitement long after we’ve mastered the basic skills. It seems we can never get enough and never exhaust their potential to surprise, uplift, and satiate us. So, we strive to learn more.

I have known excellent pilots who do not analyze or consciously conceive thermal shapes or behavior yet do very well in the bubbling air. These natural pilots are blessed, but for the rest of us, exploring the many different shapes and pathways thermals can develop is very beneficial to our flying. With that in mind, I’d like to pass along what I have seen in the past few years. Of course, we can’t see a thermal, but we can see its effects and watch smoke and other particulates that simulate a thermal. What I have been observing, specifically, is volcanos, wildfires (unfortunately), and bombings (even more unfortunately). Below, I’ll describe how these plume-producers relate to thermals and what we can learn from them.

A couple of years ago, I was fascinated by the numerous photos of the Tonga volcano eruption. The use of drones, aircraft, and other research advances have given us ringside seats to such natural outbursts. But we should ask, “Do volcanos really simulate thermal activity?” I believe the answer is yes. Obviously, the source of the initial rise of the ash and gas plume is much hotter at the surface than a thermal source, but once it rises, expands, and cools, it behaves much like any bulk of air warmer than its surroundings. The presence of particulates in the plume changes its relative density, but the fact is, many normal thermals carry a particulate load, especially in dust devil country.

I tried to catch a couple of photos of the eruption that illustrate some thermal behaviors I think are pertinent. Photo 1 shows a side view of the Tonga eruption. Here, we note the many little side balls or

boles of cloud representing a part of the warm air that breaks off from the main plume. Some of these small sidecar thermals are still going up, but if we encountered one and tried to use it, the climb would be weaker than the main column of lift, and it would soon dissipate.

The lesson, in this case, is: In an area where a large expanse is heated, don’t expect the first bloom of lift you encounter while searching for a thermal to be the best lift in the area. Of course, if you are low, it is wise to take any bit of lift you can find, but in many cases, you will be on the edge of a thermal and miss the main climb if you stay there. I can’t express how often many pilots will illustrate this principle. Usually, in an XC competition, a pilot will find the first blush of lift, others will come in, and the flock will spread out to find the main core. I have seen this in Florida, Tennessee, New Mexico, and Washington, to name a small sample of places.

However, it should be noted that when you are alone, it is difficult to tell if there are better patches of lift around you and perhaps a main core you are missing. The best policy in this case is to rely on recent experience: What have you found in the past half hour or so? Have thermals been fairly tight columns? Is the current lift nearly as strong as other thermals you have encountered on this flight? Are you in an area that has changed (perhaps is more green or more damp than before)?

All this assessment helps you decide to stay with your current lift or widen your search circle to look for a better climb. As mentioned, your current height above the ground is also a factor. The higher you are, the more you can afford to lose a bit while exploring; but also, the higher you are, the more the thermal should be consolidated into one main core with fewer offshoots. We can see a bit of this latter factor in the same photo.

The other point to notice is the presence of at least two inversion layers, identified by the wave-like clouds spread out around and above the plume cloud. With its great upward thrust and heat, the plume

keeps climbing, but the inversions cause the cumulo plume cloud to spread out quite a bit. Again, if this were a thermal we were trying to use, we would encounter bits of lift before we reached the main core, but in this case, the little lift begins much further from the core than in the absence of the suppressing inversions. The best policy in such conditions is to rely on what has gone before on a given flight. Have you had to wade through broken/weak lift to find a good climb in the previous thermals of the day? Well, expect more of the same.

Next, look at the top view photo of the volcano (photo 2). The main thing I immediately saw here was the concentric circles around the main central plume (at least six circles). I have previously shared a photo by my friend John Kangas (photo 3) showing concentric rings around a rising plume (in this case, a power plant exhaust). He first pointed out that these rings most likely exist around strong central thermal plumes and represent lifting and sinking in the air. They are similar to the rings of expanding waves you see when dropping a rock into still water. Since first writing about this phenomenon, I have had several pilots tell me they have experienced a series of lift and sink as they flew towards a thermal gaggle, as I have.

The volcano photo helps confirm what, I think, occurs with thermals. However, wider spread, disorganized, or weaker thermals probably do not cause

such noticeable rings of lift, and the lift can’t usually be used. However, they do point to a good thermal core in the area. A very experienced pilot may be able to fly more directly to the thermal core by noting how long they remain in these alternating lifting and sinking patches.

If you want to see more, you can easily find photos and videos of the Tonga volcano smoke plume by searching “Tonga volcano photos.”

As we all know, fires from Canada to Cancun have been reoccurring with devastating effects. I hate to be a cold scientist and ignore the human cost, but we can observe some thermal traits by looking at the smoke plumes and flumes from these fires. Again, with this example, I note that the rising air initiates from much greater heat than that of a ground-

warmed thermal, but after a bit of climb, it will cool to thermal temperatures. I can attest to this from my experience while flying in Venezuela and some other places where sugar cane fires produce very good thermals (hold your breath).

In the case of such fires, the area of heating is usually much larger than the heated ground that produces thermals (except in very arid regions such as the American West). But even so, you can often see the smoke (which simulates a thermal) consolidate into separate, more compact plumes. I take this action as a lesson on how a thermal down low can lift on a broad area that eventually comes together as it rises. This consolidation occurs because smaller side plumes die out or, more importantly, a stronger lifting patch draws the air in from all around it. You can use this by always trying to detect a drift or draw in one direction as you circle or hunt for lift. Of course, when you’re desperately low, you take anything you can get, but you’ll still want to be aware that there’s probably better lift nearby if yours peters out. Drift clues may help you find it.

Another observation I have made by looking at fire

photos is how a fire near a hill will draw into the slope. This effect is illustrated in Figure 1. Here, we see that a rising, hot plume trying to draw in air from the side can’t do it effectively on the side where the slope is, so the rest of the inward air pushes the lift towards the slope. Most often, a thermal originating near a hill or mountain will track towards the mountain due to the general upslope breeze and the effect described here. So a useful tip is to hug the mountain and scrape the slope when you are down low looking for thermals in hilly terrain (but stay safe with ample clearance and good control speed).

Lately, newscasters and meteo folks have been fond of using the term pyrocumulus to describe the clouds formed by large fires (pyro is the Greek root for fire). It should be noted that these clouds form in the exact same manner as cumulus created by rising thermals. Also, they can produce lightning and precipitation, just like an overdeveloped cumi.

One interesting thing to note is that, unlike most thermals, the load of smoke ash makes the entire rising column visible, so we can get a clearer picture of thermal behavior. I will point out that in wind, we

USHPA members rated H3/P3 and higher are eligible to increase their liability insurance limits to $1 million/$1 million. This increased coverage also includes extraterritorial coverage for international trips of up to 21 continuous days (for pilots rated 4/5 when increased limits are purchased).

Learn more at www.ushpa.org/member/insurance-members

can see the heated air (smoke plume/thermal) tilt over as expected, but also, we can see some stronger areas of lift shoot up above the general tilted rising mass (see Figure 2). These breakout little columns represent a patch of air that is hotter than the rest of the warmed air. In windy conditions, many of us have found that taking these hotter patches up to gain as much altitude as possible and then punching forward into the wind is the best way to find the core of a tilted thermal. Unless we are tracking almost straight downwind, it is unusual to find the best core right off the bat, so we flounder upwind to search.

Our final source of thermal visibility comes from bomb plumes. I am saddened by the events behind such displays, but such plumes again mimic the natural processes of ground-warmed thermals. Again, the source of the rising air is extreme heat as well as some explosive energy, but once again, above a certain level, the conditions of a thermal are duplicated.

Some years ago, I described an incident where I was flying out in a valley near a working quarry. I looked down and saw a large blast in the quarry 2,000 feet below. I quickly flew to it, hanging on for dear life, not knowing what to expect. What I found was one of the best thermals I have encountered in the green eastern U.S. It was big, smooth, strong, and going to the stars. So I firmly believe ground blasts simulate or trigger thermals (it was a generally thermally day, so I expect the blast brought a bunch of warm air with it to make

such a marvelicious thermal).

The main thing I have noticed with blast plumes is they tend to be tight and consolidate quickly as they rise. Such behavior is expected since they originate from a fairly small surface area or single point. I think such columns can best illustrate single-point thermals in hot, arid regions. Our experience indicates that the thermal cores are very defined, often smaller in diameter, and singular in desert conditions. The lower extent of the thermal is drawn in as the surrounding air is moved aside, then passed by.

But even so, there are occasional side excursions or calving of the main thermal column, as seen from the smoke. We should note that a stronger pump of rising air will often push up through the thermal and, when it meets slower, rising air, will cause the thermal to expand or break off a bit to the side. In addition, a vigorous thermal will cause downward moving air around it (sink), which can roll the edges and erode it.

The whole process described in our three scenarios above is somewhat chaotic, and a strong blast, fire, or volcano increases the chaos. But we are designed to detect and recognize patterns, so we can improve our understanding of thermals by observing and pondering the behavior of these visible, rising heat masses. We learn to expect the unexpected when thermalling. Still, we can reduce some of the unexpected and, thus, the mental workload by looking at photos and pondering the natural processes. The mystical becomes manageable.

: Para-alpinism, the sport of climbing a mountain and then paragliding down, is not new. People have been flying paragliders off summits since the sport’s early days. Jean-Marc Boivin, a French alpinist, flew his paraglider off Mt. Everest in 1988, an incredible feat even by today’s standards. In recent years, equipment has become substantially lighter, facilitating increasingly difficult climb-and-fly objectives.

Four years ago, Fabi Buhl, a German alpinist, became the first person to fly his paraglider from Cerro Torre in February of 2020. Cerro Torre, in Argentina’s Patagonia, is a notoriously difficult mountain to climb, and its extreme weather adds to the challenge. In January 2022, three more pilots, a team of two Swiss and one Argentinian, made the climb and flight. The European Alps are another popular climband-fly destination, with their improved ease of access and largely legally open areas for paragliding.

The U.S. faces the problem of many of our public lands being closed to free flight. While we have many world-class climbing areas with big walls, like Yosemite and Zion national parks, these areas are off-limits to paragliding, so finding legal, inspiring climb-and-fly objectives can be more of a challenge.

Notch Peak, a limestone monolith in Utah, has the second tallest cliff face (2,200 feet) in the U.S. To get there, you have to take the “Loneliest Road in America,” U.S. Highway 50, and head into the vast remoteness of Utah’s West Desert. Notch Peak is located in a BLM Wilderness Study Area (not the same as designated Wilderness). According to the BLM Policy Manual 6330, published in 2012, in a wilderness study area, “Aerial activities such as ballooning, hang gliding, paragliding and parachuting (skydiving), may be allowed as long as they meet the non-impairment standard, including not requiring cross-country use of motorized vehicles or mechanical devices to retrieve equipment.”

Jared Scheid, another paraglider from Boulder, Colorado, joined me skiing one day and mentioned the idea of climbing and flying Notch Peak. I immediately told him I wanted in. I had seen the peak up

Sarah Crosier donning her harness for a cruisy flight. Sarah Crosier flying high above Notch Peak.

close while doing some climbing guiding in the area nine years earlier when I lived in Salt Lake City. I was impressed by the magnitude of the peak, and I had heard some wild stories about the looseness of the rock and how scared people had been climbing it. It sounded like a true adventure, and the idea of being able to fly off the summit and be back to camp in mere minutes sounded like a dream.

We arrived at the trail up the backside of Notch Peak late afternoon in mid-May with our rucksacks packed with our full-sized paragliders and our NOVA Bantam miniwings. The plan was to stash the Bantams at the top of the climb so we didn’t have to climb with them. We hiked the 4.1 miles and 2,828 feet to the summit, post-holing and bashing our shins here and there in the spring isothermal snow. We were glad we didn’t attempt the trip any earlier in the season! As we hiked, we felt the intense gusts of

strong thermals ripping up through the canyon. We knew we weren’t in any rush to launch. We relaxed on top, taking in the views, and signed the summit register.

The thermic winds started to mellow out, and just before 6 p.m., I finally launched. I was surprised by how turbulent the air still felt. I pushed away from the terrain and caught a thermal, eventually flying back over Notch Peak itself. Meanwhile, the winds had shifted on Jared, but after 15 minutes or so, he was able to launch. At that point, I had climbed over 14,000 feet (launch was at 9,658 feet) in surprisingly active air for the time of day. We soared around the incredible cirque for a while, taking in the view of the massive face we planned to climb the next day.

Over the radio, I heard Jared say, “I’ve got a heater!” I didn’t know what that meant, but I decided to join him. As I approached him, I saw him take a minor