As humans, we construct our reality through an intricate, subconscious balancing act between biological sensory perception and prior knowledge. That balance was impacted over the past few years as many of our interactions shifted to virtual modes of socializing and communicating.

As this shift took place, it was fascinating to me to see how some people thrived in tha t recalibrated world, while others found online interaction exhausting and couldn’t wait to return to in-person interactions.

But it isn’t just the evolving technological landscape and our individual makeup that complicates the ways in which we experience the world. Our sensory pathways are undergoing alterations and recalibration all the time to keep up with an external environment that’s rapidly transforming — from the increased noise and bustle of growing cities to the effects of climate change.

Fortunately — through advances in neuroscience and imaging, along with better understanding of the ways that culture affects our perception of the world — we can develop strategies to navigate new sensory environments. We can also begin to anticipate what reality might look, feel and sound like in a technologically enhanced future.

This issue of USC Dornsife Magazine taps our academic researchers for insights on a wide range of topics related to the ways in which our senses help us perceive the world. You’ll read about different ways that scent has been conceptualized in India, how taste is a passport to experience Los Angeles, the ways sound shapes our world, touch deprivation in the internet age, and more. I hope you enjoy the experience.

AMBER D. MILLER Dean, USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences Anna H. Bing Dean’s ChairTania Apshankar, Maddy Davis, Greg Hardesty, Stephen Koenig, Rachel B. Levin, Paul McQuiston, Nina Raffio, Vanessa Roveto, Grayson Schmidt

Amber D. Miller, Dean • Jan Amend, Divisional Dean for the Life Sciences • Emily Hodgson Anderson, College Dean of Undergraduate Education • Stephen Bradforth, Senior Advisor to the Dean for Research Strategy and Development • Steve Finkel, College Dean of Graduate and Professional Education • Moh El-Naggar, Divisional Dean for the Physical Sciences and Mathematics • Jim Key, Senior Associate Dean for Communication and Marketing • Stephen Koenig, Senior Associate Dean for Creative Content • Peter Mancall, Divisional Dean for the Social Sciences • Renee Perez, Vice Dean, Administration and Finance • Eddie Sartin, Senior Associate Dean for Advancemen t • Sherry Velasco, Divisional Dean for the Humanities

Kathy Leventhal, Chair • Wendy Abrams • Robert D. Beyer • David Bohnett • Jon Brayshaw • Ramona Cappello • Alan Colowick • Richard S. Flores • Shane Foley • Vab Goel • Lisa Goldman • Jana Waring Greer • Pierre Habis • Yossie Hollander • Janice Bryant Howroyd • Martin Irani • Dan James • Omar Jaffrey • Bettina Kallins • Yoon Kim • Samuel King • Jaime Lee • Arthur Lev • Roger Lynch • Robert Osher • Gerald Papazian • Andrew Perlman • Lawrence Piro • Edoardo Ponti • Kelly Porter • Michael Reilly • Carole Shammas • Rajeev Tandon • Matthew Weir

Published twice a year by USC Dornsife Office of Communication at the University of Southern California. © 2022 USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences. The diverse opinions expressed in USC Dornsife Magazine do not necessarily represent the views of the editors, USC Dornsife administration or USC. USC Dornsife Magazine welcomes comments from its readers to magazine@dornsife.usc.edu or USC Dornsife Magazine, SCT-2400, Los Angeles, CA 90089.

Ever turned a blin d eye? Touched a nerve? Played it by ear? Smelled a rat? Been left with a bad taste in your mouth?

We have heard these idiomatic phrases so often that we take them for granted and yet if we stop for a moment to think about them, we realize the vital role our senses play in conveying meaning. After all, our senses are the conduit to how we experience and learn about the world — how it feels, tastes and smells, what it looks like and how it sounds — so perhaps it isn’t surprising that these references are so ingrained in our everyday language.

In this issue, we explore our principal senses — sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch — through the lens of our scholars’ teaching and research. But we don’t stop at five. Neuroscientists and philosophers now think we may have up to 33. We explore some of these lesser-known senses, along with the so-called “sixth sense,” altered states and visions. We also meet USC Dornsife mathematician Felicia Tabing who has synesthesia, a neurological condition that causes her to see numbers as particular colors. Tabing uses her synesthesia to inspire her art.

In writing about taste for this issue, I interviewed Karen Tongson, chair and professor of gender and sexuality studies, and professor of English and American studies and ethnicity, who uses Los Angeles as a laboratory to teach about food. The first task she sets her students is to reflect on their “Proustian moment” — their most memorable or meaningful taste and how it inspired them. Our conversation led me to think about my own defining taste moment. I was 14 and my father had taken me to London for the first time. For lunch one day we went to an old pub by the Thames — sawdust on the floor and scrubbed pine tables. On the menu were “escargots” (snails). I ordered them, curious about this impossibly exotic — and possibly disgusting — French delicacy. As the buttery, garlicky taste and oddly rubbery texture filled my mouth, I knew I was tasting another culture, another world that was larger and very different from my own, until then, sheltered existence in a small Scottish town. I knew then that that’s what I wanted: to live a bigger, wider, wilder life, to explore and taste all of it, in all its strange, diverse, exotic glory.

That day, I experienced an eye-opening feast for my senses; we hope that this issue provides you with a feast for yours. — S.B.

FROM THE HEART OF USC Celebrating 50 years of JEP; First comprehensive list of imprisoned Japanese Americans during WWII; Research advances fight against COVID-19 variants; Largest endowment gift to any United States university history department; Clarifying climate messaging to inspire action; Inactive sitting increases dementia risk.

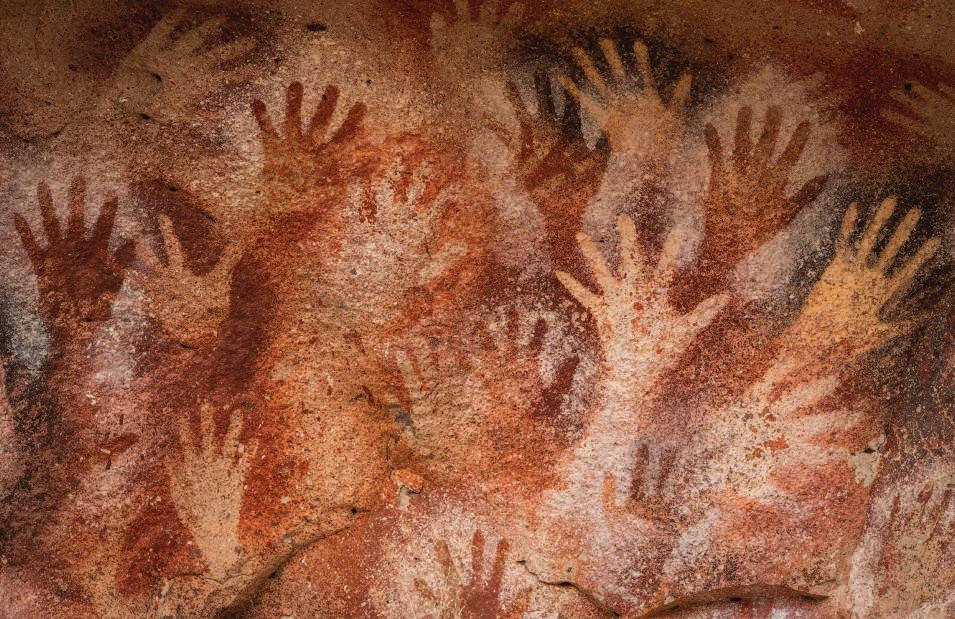

Argentina’s “Cueva de las Manos” (Cave of the Hands) is named for hundreds of paintings of hands stenciled on the rock walls. Created between 7,300 BCE and 700 CE, it is considered by some scholars to be the best material evidence of early South American hunter-gatherer groups. THE SENSES

A beloved Los Angeles landmark, the Nayarit, founded by the grandmother of USC Dornsife historian Natalia Molina, fed the senses but also provided a haven where the marginalized could feel seen and find belonging. By Susan Bell

Sight allows us to explore our world, to orient ourselves within it and to find joy in its myriad manifestations of beauty and wonder. By Rachel B. Levin

Whether it takes the form of a rousing rock concert, a friendly greeting or the lulling buzz of cicadas on a summer evening, sound holds the power to energize us, to cheer us, to soothe us and — above all — to connect us. By Meredith McGroarty

From sautéed grasshoppers to fusion food, USC Dornsife scholars use taste as a passport to explore diverse cultures, histories and identities. By Susan Bell

From aiding romance to communicating with God, scent has long been attributed near mystical abilities.

ByMargaret Crable

From cradle to grave, touch brings us comfort, pleasure and sometimes pain, reminding us of our countless connections to the world and to humanity — including our own. By Meredith McGroarty

If we think of our senses as limited to only five, we might be missing out. By Margaret Crable

CONNECT WITH USC DORNSIFE Facebook.com/USCDornsife Instagram.com/USCDornsife Twitter.com/USCDornsife LinkedIn.com/school/USCDornsife YouTube.com/USCDornsife

A beloved Los Angeles landmark, the Nayarit, founded by the grandmother of USC Dornsife historian Natalia Molina, fed the senses — not only with its acclaimed regional Mexican cuisine but also by providing a haven where the marginalized could feel seen and find belonging. By Susan Bell

This image by celebrated photographer Edward Ruscha shows the Nayarit in 1966 at the height of its popularity. Although the Echo Park restaurant is long gone, the building on Sunset Boulevard with its iconic sign remains — a cherished part of local history.

Drive through Echo Park and you can still see the original sign, faded now but still elegant, spelling out “Nayarit” in the slanting script of a bygone era. In its heyday in the 1950s, ’60s and early ’70s, people came from far and wide, eager to enjoy the authentic regional cuisine served at this popular neighborhood eatery,

described by a Los Angeles Times restaurant critic as one of the best Mexican dining rooms he had ever visited.

But to its devoted patrons, this beloved restaurant was much more than a place to eat. For a quarter century, the Nayarit was a beacon of belonging and acceptance for those — many of them

immigrants or members of the LGBTQ community — who struggled to meet these basic human needs in midcentury Los Angeles, where discrimination and segregation were rife.

The Nayarit was founded in 1951 by Natalia Barraza, a Mexican immigrant and the grandmother of USC Dornsife’s Natalia Molina,

Distinguished Professor of American Studies and Ethnicity and a 2020 MacArthur Fellow. Intrigued by her formidable ancestor, Molina plumbed her family’s history to understand Barraza’s story, and in the process illuminated many facets of the immigrant experience through the lens of her grandmother’s

restaurant. Molina reveals her findings in a new book, A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community (University of California Press, 2022).

COOKING UP THE AMERICAN DREAM Barraza immigrated alone from Mexico to L.A. in 1921

at age 21. As she realized her own American dream, running a successful business — the Nayarit — and adopting two children, she also sponsored, housed and employed dozens of other Mexican immigrants, encouraging them to lay claim to a city long characterized by anti-Latino racism. Along the way, the Nayarit became a vibrant cultural space that embodied her vision

of respect, community and mutual support, as well as an “urban anchor.”

Molina explains that urban anchors are usually considered to be civic projects, such as libraries or hospitals, but in our daily lives, the places where we feel seen, where we feel safe, are often places that we choose to go: bars, restaurants, cafes. These urban anchors, she says, are a different way to look at the city — not as a city planner envisioned it, but as immigrants finding their place in their new hometown.

“These are more than businesses,” Molina says. “They are sociocultural spaces, nourished by the countless small acts of everyday life that build and sustain affective relationships.”

The Nayarit was to become a prime example, providing a supportive “family” for immigrants and other marginalized people in L.A.

NOURISHING THE SOUL OF AN IMMIGRANT COMMUNITY

Molina notes that most Mexican restaurants of that period were called something more accessible, such as El Cholo or El Zarape.

“That my grandmother chose to name her restaurant for her home state of Nayarit signals to me that she had “patria chica” — literally, ‘love of a small country,’” Molina says.

It also created a beacon to others from that region. “When they wanted something familiar, they knew that regional food would really satiate not just their stomachs, but their souls,” she says.

In her book, Molina details

her grandmother’s efforts to serve authentic regional food while still turning a profit.

“Sometimes she served much less expensive cuts of meat — pigs’ feet, organs. As the business developed and she had more money, she was able to offer whole fish when it was available. She would travel down to Tijuana for ingredients,

Spanish-language broadcaster for the team.

“Latino baseball players had money, but they wanted to go somewhere where they could feel comfortable, speak their language and not be discriminated against,” Molina says. “When I asked Señor Jarrín why he enjoyed going there, he said, ‘I wanted to see friends, bump

turn a profit, she could have focused on just hiring experienced Mexican wait staff, but she used the restaurant as a way to bring over family legally from Mexico by providing jobs and the necessary paperwork to obtain visas.”

like moles and chiles. She offered a taco enchilada combo and served freshly made flour tortillas, more associated with Northern Mexico, that became one of the restaurant’s claims to fame.”

The restaurant was a place where you could go, not just to eat food from Nayarit, but to meet people from Nayarit, Mexico, Cuba and other parts of Latin America, and speak Spanish. It became an immigrant hub. And, Molina explains, because the food was so good and the atmosphere so lively, and because Echo Park was both a geographic and cultural crossroads, it drew people from all walks of life.

Musicians would go there after finishing their set, movie stars would eat there after a premier or a long day’s work, and Hollywood celebrities in mixed-race relationships would celebrate there because they felt accepted. When the L.A. Dodgers were in town, Latino baseball players would come to the Nayarit, as would Jaime Jarrín, the

into people I knew and speak Spanish.’

“Everybody that I interviewed, both in the U.S. and in Mexico, said that the Nayarit was the place to go,” Molina says. “And those that I interviewed in Mexico said, ‘If you visited L.A., but didn’t visit the Nayarit, it was like you hadn’t really visited L.A.’”

But in addition to the stars, the locals and the tourists, many others came to the Nayarit to find acceptance and a sense of belonging, among them immigrants and members of the LGBTQ community.

“Anyone who was facing discrimination could go to the Nayarit and find acceptance,” Molina says.

So, how did Barraza establish the Nayarit as a place where marginalized people felt they belonged?

One way in which her grandmother achieved this, Molina says, is through her hiring practices.

“If she had just wanted to

Barraza was attentive to the needs of women, helping many single and divorced women immigrate. She also hired gay men and made them feel welcome.

As the book description says, “In a world that sought to reduce Mexican immigrants to invisible labor, the Nayarit was a place where people could become visible once again, where they could speak out, claim space and belong.”

Today, the Nayarit is long gone, yet its spirit lives on. Sold by Molina’s mother in 1976 after Barraza’s death in 1969, the space continued to operate as a Mexican restaurant until the turn of the century, when it was transformed into a very different urban anchor, The Echo — a music venue celebrated for its punk concerts, where another often-marginalized population finds acceptance. The Echo’s owners opted to leave the Nayarit’s iconic sign rather than put up their own. It still remains — a reminder to anyone seeking a home away from home, a place to be seen and a place to belong.

“Anyone who was facing discrimination could go to the Nayarit and find acceptance.”

FROM

100,000 USC students have provided more than a million hours of service to neighborhoods near USC campuses through the auspices of the Joint Educational Project, recognized as one of the oldest, largest, and best university service-learning programs in the country.

Jasmin Sanchez might not have chosen a science major in college if not for the work of USC Dornsife’s Joint Educational Project (JEP), which enables participating USC students to assist in local classrooms.

In elementary school, most of her science lessons came from books or lectures, with little hands-on learning. When USC students from JEP showed up in Sanchez’s classroom one day, it changed everything.

“They provided all the materials for the students to have hands-on experiments,” she says. “One of the reasons I got into science was because I had these students coming in and teaching me.”

Sanchez graduated from USC Dornsife last spring with a degree in health and human sciences and plans to become an occupational therapist. During her time at USC, she came full circle, teaching science to third graders through JEP, just as she had been taught a decade earlier.

This was the exact outcome that the early organizers of JEP, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, hoped for when the organization began in 1972.

In the early 1970s, tension marred USC’s relationship with its neighbors. Barbara Seaver Gardner, a research associate at USC’s Center for Urban Affairs, had the vision to make a change by bringing USC and its surrounding neighbors together around a common goal: helping children.

Gardner arranged for USC students to teach in elementary school classrooms near campus, providing valuable support to schools that were often underfunded and short-staffed. JEP grew out of this vision, with Gardner becoming its inaugural director.

Around 2,000 USC students now participate in JEP programs each year. While they gain valuable teaching experience in the classroom, their young students benefit, as did Sanchez, from hands-on learning, and teachers get a little help with their workload. Since its founding, some 100,000 JEP students have provided over a million hours of service to schools.

JEP offers more than just classic educational support focused on math, literacy or science. The Peace Project trains USC students in peace education curriculum that they then bring into classrooms. A program called Little Yoginis provides elementary school children with yoga instruction.

Students also go beyond the classroom in their mission to connect with the surrounding community. The Understanding Homelessness Through Service program pairs students with

organizations such as Chrysalis, which prepares people to reenter the workforce.

Alumni of JEP are as impacted by the program as the young students they teach.

Tom Chan ’96 originally majored in business, but participating in JEP ignited a new enthusiasm for social service and teaching. He switched to a liberal arts major, served in the Peace Corps in Thailand, then earned a master’s degree in educational administration.

“If I had never served in JEP, I don’t think I would have been brave enough to change my major to liberal arts as a junior,” says Chan. “I never would have become a professional journalist, certainly never would have joined the Peace Corps, and never would have chosen education as a career path.”

He also would not have met his wife. The two connected while hanging out at the JEP House on campus.

Fifty years of success doesn’t mean the JEP crew is content to rest on their laurels. In partnership with the global educational organization Room to Read, JEP recently released a series of 10 children’s books exploring subjects related to science, technology, engineering, arts and math. Some 9,000 sets of the books will be distributed to children and schools through USC neighbor educational programs.

“I’m just so incredibly proud of what we’ve been able to accomplish in these 50 years,” says Susan Harris, executive director of JEP. “So many students have come through JEP’s doors and been able to make a meaningful change in communities and then go on to do amazing things in their own lives.” —M.C.

New degree program adopts holistic approach to educate students on how to improve global security.

Connecting climate change with Canada’s recent increases in naval defense spending might not seem obvious, but this type of holistic perspective is the focus of USC Dornsife’s new Master of Arts in Global Security Studies. The program seeks to understand our changing world through the lens of experts in political science, international relations, economics, spatial sciences and environmental studies.

The two-year, full-time program, which launched in fall 2022, is especially geared toward students looking to pursue or advance a career in government; with nongovernmental organizations such as those dealing with human rights or disaster relief; or at private firms, including those specializing in national security, says Steven Lamy, Professor Emeritus of International Relations and Spatial Sciences.

Lamy explains that the

program’s spatial sciences element is one thing that sets it apart from similar offerings at other institutions. It is spatial sciences data that allows analysts to make connections between actions taken on the world stage and the various causes and catalysts of these actions. One example might be how Canada’s naval spending is affected by warmer temperatures leading to ice loss that exposes more of the coastline.

“Government agencies, and non-governmental and private sector actors are looking for people who have the skills in spatial sciences to do things like assess attacks made during war and how the populations there are affected, using mapping data,” Lamy says.

Amy Carnes, acting chief of staff for USC Shoah Foundation — The Institute for Visual History and Education, explains that her institute’s extensive

resources, including the testimonies of survivors of war and genocide, will also give students a unique opportunity to study the human impact of mass violence.

“Because we have connections with partners around the world that are doing work that is related to human security and the aftermath of mass violence, we have many resources and bring a lot to the table in terms of practical, hands-on experience,” Carnes says. —M.M.

The list of names of Japanese Americans forcibly interned during WWII has always been woefully inaccurate. Now, a USC Dornsife scholar sets the record straight.

Pioneering research could help predict — and protect against — new COVID-19 strains.

Researchers have found the first experimental evidence explaining why the COVID-19 virus produces variants such as delta and omicron so quickly.

The findings could help scientists predict the emergence of new coronavirus strains and possibly even produce vaccines before those strains arrive.

Scientists led by USC Dornsife’s Xiaojiang Chen, professor of biological sciences and chemistry, figured out the COVID-19 virus hijacks enzymes within human cells that normally defend against viral infections, using those enzymes to alter its genome and make variants.

The scientists infected human cells with the coronavirus in the lab and then studied changes to the virus’ genome as it multiplied. They noticed that many mutations that arose as the virus replicated itself were caused by changing one particular nucleotide, cytosine (C), to Uracil (U).

In 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his administration, fearful that those of Japanese descent would remain loyal to their ancestral home rather than to the United States during World War II, issued Executive Order 9066. The order forced Japanese Americans from their homes to remote camps throughout the U.S. Some 1,600 prisoners died during their incarceration and many lost property and businesses they were forced to abandon.

A complete and accurate list of victims of the executive order has remained elusive over the years. Many names were misspelled and others lost while identities of those born in the camps were often omitted. The Reagan administration’s Civil Liberties Act of 1988 issued an apology to those interned as well as a check for $20,000 to the roughly 80,000 people — including survivors and their families — that the government was able to trace. However, a lack of technology at the time meant that the total number of victims remained inaccurate.

The first comprehensive accounting of those imprisoned is now complete, thanks to the work of Duncan Williams, professor of religion, American studies and ethnicity, and East Asian languages and cultures and director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture.

Williams spent years collecting names from camp rosters and other primary source documents, building a list that not only accurately spells each name, but also produced an accurate tally of the number of people sentenced to the camps.

“Up until this point, everybody’s been guessing,” says Williams. “We came to a total of 125,284 when we finished the project.”

The names are printed in a book titled Ireichō, or The Book of Names, a choice inspired by the Japanese tradition of “Kakochō,” or “The Book of the Past.” A kakochō lists those who have passed away and is placed on altars and read during memorial services.

The book is part of Williams’ and the center’s ongoing effort to memorialize the victims of Executive Order 9066. Their project, Irei: National Monument for the WWII Japanese American Incarceration, received a $3.4 million grant from the Mellon Foundation. It will eventually include an online archive and a series of monuments at former camp sites in memory of those imprisoned.

In September, The Book of Names was put on display at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, where it will remain for a year. Relatives of victims can stop by to place a Japanese “hanko,” or seal, by their family member’s name, as a way to acknowledge their memory. Relatives can also request changes or additions to the list.

Once any edits have been entered at the end of the book’s residency, the list of those who were interned in the camps will be considered finally complete. —M.C.

The high frequency of C-to-U mutations pointed them toward a group of enzymes called APOBEC, which cells often use to defend against viruses by converting Cs in the virus’ genome to Us with the aim of causing fatal mutations.

In an experimental first, Chen and the team found that the C-to-U mutations actually helped the COVID-19 virus to evolve and develop new strains faster than expected.

“Somehow the virus learned to turn the tables on these host APOBEC enzymes for its evolution and fitness,” Chen says.

Fortunately for researchers looking to overcome COVID-19, every good offense has its weakness. In this case, the mutations created by APOBEC enzymes are not random — they happen at specific places in the virus’ genetic sequence. So, scientists can look for these hotspots and possibly use them to predict what new COVID-19 variants might emerge and suggest how to update vaccines so they protect against any new variants that are likely to spread. —D.S.J.

A USC Dornsife alumna donated $15 million in her family’s name to the Department of History at USC Dornsife, the single largest gift to a USC humanities department.

The landmark gift from Elizabeth Van Hunnick follows her donation in 2016 to establish the Garrett and Anne Van Hunnick Chair in European History. Combined, Van Hunnick’s gifts to the department represent one of the largest endowment contributions to any university history department in the United States.

The gift endows three faculty chairs, establishes a faculty research fund, creates a graduate student fellowship and names the department the “Van Hunnick History Department.”

The three new faculty chairs will be named after Van Hunnick and her late father and sister: the Elizabeth J. Van Hunnick Endowed Chair in History; the Garrett Van Hunnick Endowed Chair in History; and the Wilhelmina Van Hunnick Endowed Chair in History.

The previously established Garrett and Anne Van Hunnick Endowed Chair in European History was named in honor of Elizabeth Van Hunnick’s late parents.

“This landmark gift will not only provide essential support for our researchers to pursue cutting-edge scholarship, it will help the department become a magnet for outstanding new faculty, propelling this already strong department to a position of national preeminence,” said USC Dornsife Dean Amber D. Miller.

Van Hunnick, an alumna of USC Dornsife’s history department and resident of San Diego County, said she hopes her gift will help elevate the department to even greater prominence and support the development of more informed leaders.

“I am encouraged by the fact that we’ll have an outstanding history department, hopefully known nationwide and attracting many prominent scholars,” she said. “That’s important because you can see what’s happening in the world today; you see leaders and politicians making the same mistakes over and over again.

“Things could be different,” she said, “if they would just look at history and understand what happened in other cultures and civilizations. You can truly learn a lot from the past.”

Jay Rubenstein, professor of history, chair of the newly renamed Van Hunnick History Department and director of the USC Dornsife Center for the Premodern World, noted that the “astonishing” gift will transform the department.

“The world has always been a highly interconnected place, and the story of its past is a tangled and serpentine tale,” he said. “To tell that story properly requires history departments with great geographic and chronological reach. Thanks to this gift, USC Dornsife’s history department can

attain that degree of wide-ranging excellence.”

Van Hunnick’s parents, Garrett and Anne, emigrated to the United States from the Netherlands in the 1920s.

“Since both my parents were born in the Netherlands, we were raised learning about European culture and history, and we traveled frequently to Europe,” Van Hunnick said.

A teacher, she journeyed to dozens of storied locations around the globe, documenting her excursions on film and sharing them in her classroom.

“I was interested in going to centers of ancient cultures,” she said, including Greece, Rome, Asia, Africa and the Middle East. “I took thousands of 35mm slides, and I would show them to my students. Or maybe the term is ‘bored them,’” she added, laughing, “but I thought it was valuable to share what I saw and learned.”

This spirit of seeking broader knowledge led to Van Hunnick’s support of USC Dornsife and the history department.

“I agree with the Greeks that in order to be a well-educated person you should study many, many different things,” she said. “It’s not just taking a course to get a job. That’s fine, but it’s important to be — I guess the oldfashioned term is — ‘well-rounded.’”

For History Department Chair Rubenstein, the gift is nothing short of historic.

“This moment is — and as a historian, I don’t use this term lightly — a revolution.”

If

don’t see the connection between black holes,

and the economics of happiness, you’re probably one of our few readers who hasn’t yet discovered the monthly, virtual event series known as Dornsife Dialogues. The hour-long forums, which skyrocketed in popularity during the pandemic, feature USC Dornsife scholars (and others) engaged in fascinating discussions on a wide range of topics.

“Unless you’re a student, you’ve got few opportunities to hear our brilliant scholars share their expertise on a wide range of interesting and topical issues,” says USC Dornsife Dean Amber D. Miller. “Dornsife Dialogues changes that dynamic, offering our alumni and others the opportunity to not only hear directly from our faculty and researchers, but to ask them questions.”

Launched in 2017 as a limited series of in-person forums that were recorded and shared via USC Dornsife’s YouTube channel, Dornsife Dialogues was revived in early 2020 as a series of live Zoom events. The first event of the new series, “The Pandemic Election,” featured the leaders of the USC Dornsife Center for the Political Future, Robert Shrum and Mike Murphy, in a lively discussion about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the 2020 election.

There have been 38 events since then; collectively they have had well over 60,000 views.

“We sensed there was a hunger among our alumni, particularly early on in the pandemic, to not only connect with their alma mater, but to hear from experts on timely and interesting topics,” says Sarah Sturm, senior executive director of USC Dornsife alumni relations. “What we didn’t know was how intense the interest would be and that more than two years later, it would remain so strong.”

Ben Wong ’78, who has a PhD in cellular and molecular biology, says he has watched about 20 Dornsife Dialogues. “I truly enjoy learning new things,” says Wong, “especially since there are no quizzes, midterms or final exams.” His favorite event was titled “How to Have Fearlessly Curious Conversations in Dangerously Divided Times.”

“I trust the information to be current, accurate, reliable and presented without an agenda, other than to inform,” Wong says. “Certainly, speakers have their own viewpoints, and frankly if they didn’t, they wouldn’t be very interesting. But USC Dornsife does an excellent job of providing balance.”

The politically themed events were some of the most popular for Larry Goodkind ’84, who says he watches to enjoy “a discussion that’s well-rounded and thoughtful on ways forward.” But the double major in political science and broadcast journalism says he has also enjoyed some of the discusions that “were lighter in nature,” including one regarding the history of the Olympics, hosted by a student. —J.K.

A series of free, virtual events enable alumni to connect with USC Dornsife experts and savor the joys of lifelong learning — without the stress of quizzes, essays or finals.

Scan the QR code to watch highlights from past Dornsife Dialogues. Visit dornsifedialogues.usc.edu to watch past events and subscribe to the email list.

“This process of scientific progress is important for us to wrap our heads around. I think there is a big part of the overall community that is actually coming along on that journey and that might speak to a future where we take public health and our own health much more seriously.”

“You can’t get rid of belief in the supernatural. It’s in your pockets like lint.”

“My job was to get imminent threat information from them in an effective manner.”

— Lisa Bitel, Dean’s Professor of Religion and professor of religion and history

— Peter Kuhn, Dean’s Professor of Biological Sciences and professor of biological sciences, medicine, biomedical engineering, aerospace and mechanical engineering and urology

—Tracy Walder, (BA, history, ’00), former CIA/FBI field agent

“Witches: Beyond Myths and Magic” aired October 31, 2022

“The Unexpected Spy” aired May 6, 2020

you

COVID-19“The Evolution of COVID-19” aired January 19, 2022

Experts aim to inspire action on climate change by refining messaging to increase public engagement.

with the topic. Then we can move to heighten their motivations to pay attention to messages around climate change and to perhaps take actions in their own life to mitigate its effects by adopting more sustainable practices,” Sinatra says. —P.M.

Watching TV might be relaxing but research shows sedentary inactivity may increase risk of dementia.

Adults aged 60 and older who sit for long periods watching TV or engaging in other passive, sedentary behaviors may be at increased risk of developing dementia, according to a new study by researchers at USC Dornsife and the University of Arizona.

Recipients of the 2022 Faculty Innovation Awards, presented by the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies, based at USC Dornsife, are taking steps to explain to the public the threat posed by climate change — such as more powerful tsunamis and hotter temperatures — in ways that inform and inspire action rather than deepen cultural divisions.

“To make the best use of climate change research, experts need to share that knowledge with the public in ways that are clear and meaningful,” says Jessica Dutton, executive director of the USC Wrigley Institute and adjunct assistant professor (research) of environmental studies.

For example, Matthew Kahn, Provost Professor of Economics and Spatial Sciences, and Rob Metcalfe, associate professor of economics, both at USC Dornsife, are using cutting-edge digital tools to accurately convey potential long-term environmental risks for homebuyers. They have partnered with Redfin and the First Street Foundation to incorporate historical and current weather data to assign properties with a risk score for flooding or wildfire. The two are also investigating the effect this data is having on purchasing tendencies.

“More homebuyers are asking: Is the home in a fire zone? Is there a risk for flooding?” Kahn says. “Thus, buyers are less likely to regret their purchase and sellers can take steps to offset Mother Nature’s punches so that they can still sell their asset for a high price.”

Meanwhile, experts on science communication are investigating how political affiliation may distort understanding of climate terms.

Gale Sinatra, professor of education and psychology, says personal emotions and motivations play a large role in an individual’s receptivity to climate-related messaging. For instance, the term “climate crisis” can prompt a different emotional response than “climate justice” or “global warming,” she notes.

“The goal is to leverage emotions in a positive way — in other words, not to get people upset or angry, but rather to elicit emotions that heighten concern and engagement

The study used self-reported data on sedentary behavior for more than 145,000 participants aged 60 and older in the United Kingdom — all of whom did not have a diagnosis of dementia at the start of the project. After an average of nearly 12 years of follow-up, the researchers used hospital inpatient records to determine dementia diagnosis, and after adjusting for certain demographics (such as age and gender) and lifestyle factors (such as smoking and alcohol use), they arrived at their findings.

Researchers found the link between sedentary behavior and dementia risk persisted even among participants who were physically active. However, the risk is lower for those who are active while sitting, such as when they read or use computers.

“It isn’t the time spent sitting, per se, but the type of sedentary activity performed during leisure time that impacts dementia risk,” says study author David Raichlen, professor of biological sciences and anthropology at USC Dornsife. He adds that sitting for long periods has been linked to reduced blood flow in the brain, but intellectually stimulating activities may counteract some of these negative effects.

“What we do while we’re sitting matters,” Raichlen adds. “This knowledge is critical when it comes to designing targeted public health interventions aimed at reducing the risk of neurodegenerative disease from sedentary activities through positive behavior change.” — N.R.

USC Dornsife scholars uncover region’s first-known Roman amphitheater, yielding clues about lives of ancient Roman soldiers stationed outside fabled city.

In 1902, the archaeologist Gottlieb Schumacher conducted the first survey of the ancient city of Megiddo in northern Israel. The area is better known as Armageddon, where the Christian Bible prophesizes that the armies of the world will clash in a final battle.

Schumacher uncovered evidence of occupation by the Roman army and a large, circular depression in the earth that he guessed was an ancient amphitheater. In July, an excavation led by historian and archaeologist Mark Letteney, a former postdoctoral fellow at the USC Mellon Humanities in a Digital World Program, finally proved his hypothesis correct.

The amphitheater was built for the local military base, occupied by Legio VI Ferrata (the 6th Ironclad Legion), which protected Rome’s holdings in what was then the Province of Judea. It’s the first Roman military amphitheater uncovered in the Southern Levant, which encompasses Israel, Jordan and Palestine.

Assisting Letteney was Krysta Fauria, a doctoral student in religion, who found a gold coin that helped the team more accurately date the structures. The coin, which has lost none of its brilliance over the centuries, dates from 245 AD, during the reign of Emperor Diocletian.

Research on the site will continue next summer, with Letteney back in the trenches. He’s hoping to uncover more of the east and west gates of the amphitheater, enabling the team to achieve more precise dating and better understand Roman construction style of nearly 1,700 years ago. —M.C.

A new health-focused minor teaches students how to tackle stress and stay fit.

Some 800 years ago, the Maya worshipped the god of honey in the sacred town of Tulum on Mexico’s Caribbean coast. The town’s importance as a site of spiritual practice remains, with thousands of people visiting the area each year to attend yoga and meditation retreats.

This year’s visitors included a group of USC students on a week-long Maymester course. Led by Isabelle Mazumdar, senior lecturer in physical education, the students took yoga lessons, meditated and explored the region’s history.

The trip was part of USC Dornsife’s new Mind-Body Studies minor, which aims to help students tackle stress and stay fit by teaching them the fundamentals of good health, from sleep to physical exercise.

For neuroscience and cognitive science major Christina Maineri, the new minor also connects directly with her career interests. “I hope to use what I learn from the Mind-Body Studies minor, particularly in regard to how we train our brain, to assist dementia patients,” she says. —M.C.

Pioneering researchers forge path to more sustainable laboratory practices.

At USC Dornsife, two chemistry professors have recently implemented techniques to make their respective research labs greener.

In 1998, the American Chemical Society developed 12 principles of green chemistry, which include measures such as energy efficiency, pollution prevention and the proper disposal of wastes.

In her freshman laboratories, Jessica Parr, professor (teaching) of chemistry, has nearly eliminated the use of mercury in experiments. Her students now also use waste containers, rather than a drain, for water and salt disposal.

“If we introduce students to these practices early, they hopefully will retain some of these ideas and sustainable processes as they go on to other laboratory experiences,” Parr says.

Meanwhile, Travis Williams, professor of chemistry, says his lab has cut energy use.

“We upgraded to a new microfocus diffractometer, which is not only a much better scientific instrument, but uses a fraction of the electricity,” Williams says. “Then we put some blinds on the windows to keep the solar heat out, and now we’ve nearly halved the amount of electricity we use.” —G.S.

ALUMNUS Washington, D.C.

Alumnus helps finally establish a national World War I memorial in the nation’s capital.

Although the United States mobilized more than 4 million troops and lost nearly 120,000 soldiers during World War I, no official memorial had been built at the nation’s capital in the ensuing century since the conflict.

It took a years-long effort from people like alumnus and former Navy captain Chris Isleib, who served as director of public affairs for the World War I Centennial Commission, to secure land and funding to build a memorial. Finally opened in April 2021, the memorial is inscribed with the words of poet and WWI veteran Archibald MacLeish: “We were young, they say. We have died. Remember us.”

The memorial is a fitting accomplishment for Isleib. After graduating with a degree in creative writing in 1985 and serving on the USS Iowa, he spent his career in communications telling stories of the military, from Hollywood to the Pentagon, to ensure they are not forgotten.

—M.C.

More than 90% of the Earth’s ocean species died off in a mass extinction caused by global warming and ocean acidification at the end of the Permian period, some 252 million years ago. USC Dornsife paleobiologist David Bottjer and PhD student Alison Cribb, along with an international team of researchers, have found ancient clues on the seafloor that show how life bounced back.

By studying trace fossils and ancient seabed burrows and trails, they discovered that shrimps, worms and other bottom-burrowing animals were among the first to recover after the catastrophic event. The research team — which included scientists from China, the United States and the United Kingdom — were able to piece together the revival of sea life by analyzing samples representing 7 million years and that showed details at 400 sampling points.

“One of the most remarkable aspects of the data is the breadth of ancient environments we could sample,” says Bottjer, professor of Earth sciences, biological sciences and environmental studies.

Trace fossils mostly document soft-bodied sea animals with little to no skeleton. But the data can indicate how the behaviors of these animals also affected the evolution of other species, including those with skeletons.

It is estimated that it took about 3 million years for the ecological recovery of soft-bodied animals to match pre-extinction levels.

“The first animals to recover were deposit feeders such as worms and shrimps,” says Cribb. “The recovery of suspension feeders, such as brachiopods, bryozoans and many bivalves, took much longer.” Cribb suggests that the deposit feeders may have churned mud that prevented suspension feeders from settling on the seafloor or that prohibited them from feeding efficiently.

Understanding mass extinctions of the distant past and how soft-bodied species recovered can provide important insights relevant to the present and future.

Bottjer said the team’s findings show a variety of ways different groups of seafloor dwellers responded to changing environmental conditions over time, and how that may have played a more important role in the evolution and ecology of species as life recovered than previously understood.

From Inuit hunters in their endless snowy landscape who have no concept of what it means to be lost to profound leaps in microscopy that enable scientists to watch an eye as it forms — sight allows us to explore our world, to orient ourselves within it and to find joy in its myriad manifestations of beauty and wonder.

By Rachel B. LevinThough there is no consensus about which of our five senses is the most important, sight has an edge. Philosophers from Aristotle to Galileo have exalted vision above other sensory capacities, tying it to humanity’s noblest pursuits. From a neuroscientific perspective, visual processing is the most dominant sensory function in the brain. And culturally speaking, most Americans believe there could be no health outcome worse than losing their eyesight.

The perceived value of sight is reinforced by the fiercely visual nature of contemporary life. Screens are now constantly at our fingertips. They saturate us with visual information to process, and the remote social interactions they facilitate are devoid of embodied inputs like smell and touch.

Our sense of sight confers power. We use it to investigate and surveil the planet (and beyond) and take pleasure in its splendors. But sight is also a source of vulnerability. The biological processes that allow our visual system to observe the world accurately can also lead us to perceive illusions — and we don’t always know the difference.

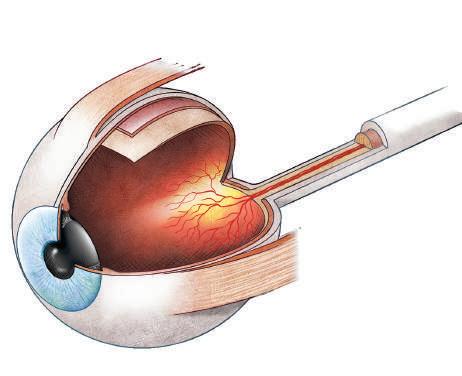

Sight begins in the eye. Light passes through the domeshaped cornea and enters the eye’s interior through the opening called the pupil. The iris (the colored part of the eye) controls how much light the pupil lets in. Next, light passes through the lens, the clear, inner part of the eye that focuses light on the retina. This light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye contains special cells called photoreceptors that turn the light into electrical signals.

Yet even as the eye receives visual input, “seeing” actually happens in the brain. Electrical signals travel from the retina through the optic nerve to the occipital lobe, an area toward the back of the brain that contains the visual cortex. Half of the brain then becomes involved, directly or indirectly, in interpreting the signals.

There’s quite a lot that needs interpreting. Light passing through the eye is bent twice — first by the cornea, then by

the lens. This double bending means that whatever you’re looking at appears upside down on your retina. Your brain makes sure you perceive it as right-side up. Likewise, you perpetually receive two images of the world, one through each eye, and your brain combines them into one.

The role of the brain in sight is most apparent when we’re confronted with visual stimuli that are ambiguous. For example, the “impossible” staircase in M. C. Escher’s Ascending and Descending appears to climb up and down simultaneously because, as your brain attempts to translate the 2D image into 3D reality, it falls back on assumptions that lines are straight and corners are 90 degrees.

Perhaps you remember the bad cellphone photo of “the dress” that went viral in 2015? Some insisted the dress was white and gold; others swore it was black and blue. Research revealed that people’s life experiences influenced their color perception.

Night owls were more likely to see the dress as black and blue, whereas early risers tended to see it as white and gold. That may be because of assumptions each group made about whether the garment appeared in bright daylight or under an indoor bulb — a difference of illumination that cues our visual system toward divergent color interpretations. Those who burn the midnight oil were more inclined to assume artificial lighting than those who rise with the sun, perhaps because of more exposure to it.

“We rely so much on our sense of sight that we trust what we see with our own eyes,” says USC Dornsife’s Norbert Schwarz, Provost Professor of Psychology and Marketing. “Seeing is believing, as the saying goes. But our visual processing can be fallible.”

Making accurate visual judgments is a core part of human survival. We evolved to rely on sight for orienting ourselves to our environment, avoiding danger and navigating through space. Jennifer Bernstein, a visiting scholar at the

USC Dornsife Spatial Sciences Institute, notes that all cultures have developed practices for wayfinding, which involves figuring out where you are and how to get where you need to go.

Inuit hunters in the Canadian Arctic provide an example of how sharply developed our visual perception can become in the service of wayfinding. Amid the snowy landscapes of the Igloolik region, few topographical landmarks stand out to differentiate routes. Young Inuit learn through years of tutoring by elders to orient themselves by attending to visual cues as subtle as snowdrift shape and wind direction. Amazingly, up until the recent adoption of GPS devices, the Inuit had no concept of being “lost.”

If you’ve ever felt directionally challenged without your mapping app — or gotten lost even while using one — you’re probably aware that digital tools are eroding our visual attentiveness to navigational cues in the landscapes we traverse. Bernstein points to research linking GPS use to lower spatial cognition and poorer wayfinding skills.

But she cautions against demonizing the technology, arguing that GPS tools can function as visual “prostheses” that augment our powers of sight. GPS can help those with visual or spatial impairments navigate the world independently. For sighted individuals, mapping apps can facilitate a shift in visual attention from the “how” of navigation to an appreciation of the sights along the route.

“If I can just get in the car and drive, I can look at the fog and the Golden Gate Bridge,” says Bernstein of letting GPS guide her around the Bay Area. In other words, when technology “sees” the path for us, our sense of sight is no longer just a tool of survival — it’s a window into pleasure.

Our visual system is designed for delight. The neural pathway that extends from the retina to the occipital cortex contains opioid receptors, which, when activated, trigger a cascade of chemical changes linked to feelings of pleasure.

The late Irving Biederman, Harold Dornsife Chair in Neurosciences, and professor of psychology and computer science, and director of USC Dornsife’s Image Understanding Laboratory, explained this neural system in a previous issue of USC Dornsife Magazine. “When [our eyes] are not engaged in a deliberate search, such as looking for our car in a parking lot,” he said, “they are directed towards entities that will give us more opioid activity.”

Gazing at beautiful things — natural vistas, compelling artworks, attractive people — stimulates our brain’s reward system and makes us feel good. But the old adage is also true: Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

According to Schwarz, individuals develop an aesthetic preference for visual stimuli that they find easy to process. In one of Schwarz’s experiments, subjects were given a list of words to learn. In one group, the word “snow” was on the list; in the other, the word “key” was featured. Both groups were then shown pictures of a snow shovel and a door with a lock. Those in the “snow” group rated the shovel as prettier; those in the “key” group rated the door as more attractive.

“Any variable that makes processing easier increases perceived beauty, even if it’s a variable that has nothing to do with beauty,” says Schwarz.

In addition to neurochemical and cognitive factors, cultural norms also influence what we see as beautiful. When viewing paintings or sculptures, we often prize the

sophistication of an artist’s vision — a sort of “inner eye” that interprets what it sees in a unique way. But USC Dornsife’s Kate Flint, Provost Professor of Art History and English, explains that artistic and social norms of each era influence both the creation and reception of art.

“Beauty in a work of art … is incredibly culturally determined,” she says. “There are conventions of what constitutes the beautiful at certain times, which then get upended by other generations, other traditions.”

Romantic poet William Blake once mused on the possibility of seeing a world in a grain of sand. He was alluding to not only the grandeur but also the knowledge we can access with our powers of sight — if we pay close enough attention.

Of course, with the naked eye, we can’t actually see the (microscopic) world in a grain of sand or, for that matter, the (telescopic) world in a speck of celestial light. Our desire to know and understand truths beyond our visual limits has driven the development of increasingly powerful sight-enhancing technologies.

State-of-the-art telescopes have offered astrophysicists like USC Dornsife Dean Amber D. Miller the opportunity to visualize faraway stars and look back in time. The first images released from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope earlier this year revealed the presence of never-before-seen galaxies, whose light originated more than 13 billion years ago — around the time of the Big Bang. Miller has likened such images to “‘baby pictures’ of the cosmos.”

Much closer to home, USC Dornsife scientists are making profound leaps in microscopy. At the USC Michelson Center for Convergent Bioscience, the cryo-electron microscopy core facility that opened last year is enabling researchers to glimpse molecules as tiny as individual proteins. And the Translational Imaging Center (TIC), based at USC Dornsife and USC Viterbi School of Engineering, is at the forefront of developing new tools that enable scientists to watch the biological processes of cells as they are unfolding — building microscopes that can collect technicolor images with a speed and sensitivity once thought impossible. TIC researchers can watch the circuit changes in the brain that accompany learning down to the single synapse level. Their collaborators at Keck School of Medicine of USC, Brian Applegate and John Oghalai, are even able to observe and measure the nanometer-sized movements in the human cochlea, part of the inner ear, as it converts sound to neuronal signals.

These technological advances are making it possible for biologists to see the eye itself in impactful new ways. Scott Fraser, Provost Professor of Biological Sciences, Biomedical Engineering, Physiology and Biophysics, Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Pediatrics, Radiology, Ophthamology and Quantitative and Computational Biology, directs the TIC. He and his team have been able to peer into an animal’s eye as it takes shape and forms connections in the brain. Recently, Fraser and his team have turned their tools to the human eye, observing the changes wrought by age and disease. Their hope is that better understanding the eye’s cellular processes can lead to new treatments for vision-robbing diseases like macular degeneration and diabetic retinopathy.

Fraser’s research captures the fragility of sight and its strength all at once. Our eyes may be susceptible to a host of pathologies, but they also have the potential to bring clarity to life’s greatest mysteries.

When technology “sees” the path for us, our sense of sight is no longer just a tool of survival — it’s a window into pleasure.

Whether it takes the form of a rousing rock concert, a friendly greeting or the lulling buzz of cicadas on a summer evening, sound holds the power to energize us, to cheer us, to soothe us and —above all — to connect us.

By Meredith McGroartyWhen Ludwig van Beethoven began losing his hearing as a young man in 1798, he blamed it on a fall, though modern researchers believe illness, lead poisoning or a middle ear deformity could have been factors. Whatever the cause, the hearing impairment did nothing to sweeten the acclaimed composer’s notoriously sour disposition, understandably contributing to his melancholy and ill temper.

Today, more than 200 years after the onset of Beethoven’s hearing problems, we know far more about the nature of sound and the causes of hearing loss. We also better understand how the brain comprehends language, and the power of music to affect brain activity.

But if we now have the means to protect against certain diseases that affect hearing, solutions to address the most common cause of hearing loss, aging, have been more challenging. The effects of aging on hearing can be slowed or partially ameliorated without biomedical devices, but they cannot be reversed — yet.

NEW HOPE FOR THE DEAF

USC Dornsife’s Charles McKenna, professor of chemistry, believes he, along with scientists at Harvard Medical School’s Massachusetts Eye and Ear Institute, may have discovered a drug to repair inner ear cells that are damaged not only from aging, but from prolonged exposure to noise. This drug has the potential to treat damaged areas without being washed away by the ear’s natural fluid — a crucial breakthrough.

McKenna explains that neural sensors turn the vibrations

we perceive as sounds into electrical impulses that the brain can register and decipher. When these sensors are damaged, hearing loss and other issues occur.

“A nerve can send a signal to the brain that lets the brain say, ‘This is a Mozart composition’ or ‘This is someone speaking,’ ” McKenna says. “The theory is that if you could regenerate the neural sensors, you would restore hearing to those who have lost it. Though there are drugs that appear to have the ability to induce regeneration of these neural sensors, successfully deploying those drugs has been a tremendous challenge.”

First, the cochlea, the part of the inner ear where damaged cells are located, is bony, making it difficult for drugs to adhere to it. Second, even if a compound is shown to attach to the structure, the inner ear’s naturally occurring fluid tends to wash it away before it can work.

Based on encouraging findings from their latest study, McKenna says he and his colleagues are optimistic their compound will adhere to the cochlea long enough to be effective. With more research, they hope to prove its efficacy.

While Beethoven struggled with hearing problems, his music, perhaps paradoxically, may help improve the brain functions of others.

Assal Habibi, head of the Brain & Music Lab at USC Dornsife’s Brain and Creativity Institute and associate professor (research) of psychology, explores how music and song affect brain activity using data collected through

electroencephalography and neuroimaging. She and her colleagues have found that music can have several quantifiable benefits for the human brain, particularly in children. For example, playing music can help children hone their concentration skills.

“Music training helps with what is known as speechin-noise perception — for example, when you’re in a noisy environment and someone is calling your name or saying something you need to hear,” Habibi says. “This is a crucial ability for children in a noisy classroom who need to be able to hear the teacher and tune out background noise.”

Music training has also been shown to help some children reach developmental milestones faster. If ongoing research can establish the connection, music training might be able to prevent the onset of certain behavioral and learning issues and lead to new therapies for children who struggle with them.

“One hypothesis is that if music can assist children in reaching developmental milestones faster, for example if they develop language skills earlier, they will be able to better express their feelings and communicate more effectively,” Habibi says.

While music therapy can help individuals sharpen their ability to discern the signal from the noise, linguistics is the discipline that deals with how we create and process the signal — speech itself.

Linguists specialize in the building blocks of language, or how sounds combine to create a word that is understood

by different people, despite the fact that no two people will speak a word completely identically. Dani Byrd, professor of linguistics at USC Dornsife, examines how the vocal tract creates and combines these sounds in everyday speech, and how languages evolve to structure these sounds for encoding information.

“As a linguist I ask, ‘What are the rules that languages use to build their structures, to build their words and phrases? How do they differ from language to language?’ And I look at how and why we can understand these sounds as we do.”

Byrd says our complicated and incredibly nuanced sense of hearing mirrors a corresponding complexity in how we shape our words and sounds to convey meaning.

“The sensory cells of the inner ear are the most sensitive mechanoreceptor of the body. They have movements on a nanometer scale,” she says. “When air pressure fluctuations move your eardrum, that creates movement and an electrochemical cascade inside the inner ear.”

Our sense of hearing has the power to move us in a myriad ways. It also has the power to inspire wonder at its many — as yet — still unsolved mysteries: Why is it that we understand a gasp as a signal of surprise, or possibly fear? Why does the key of D minor often provoke feelings of sadness in one listener but not another? And how is it that our brain can take these vibrations of air and transform them into words, emotions or messages?

“Isn’t it amazing,” says Byrd, “that these tiny fluctuations in air pressure can make you laugh or cry, can convey urgency, can make you fall in love?”

Our nerves relay signals to the brain, which interprets them as sight (vision), sound (hearing), smell (olfaction), taste (gustation) and touch (tactile perception). These five basic human senses help us perceive and understand the world around us.

Olfactory bulb

Olfactory tract

Cribform plate

Chemicals in the air stimulate signals that the brain interprets as smells.

Equipped with 400 olfactory receptors, humans may be able to detect more than 1 trillion scents, according to the National Institutes of Health. We can accomplish this impressive feat thanks to the olfactory cleft found on the roof of the nasal cavity next to the region of the brain responsible for interpreting smell — the olfactory bulb and fossa. When we sniff or inhale through the nose, chemicals in the air bind to specialized nerve receptors located on hairlike cilia at the top of the nasal cavity. This triggers a signal that travels up a nerve fiber to the olfactory bulbs then along the cranial nerves and down the olfactory nerves toward the olfactory area of the cerebral cortex, enabling the brain to interpret what we are smelling.

The complex labyrinth that is the human ear uses bones and fluid to transform sound waves in the air into electrical signals.

Music, laughter, speech — all reach our ears as sound waves in the air. The outer ear funnels the waves down the narrow passageway called the ear canal to the eardrum, or tympanic membrane, creating mechanical vibrations. The eardrum transfers the vibrations to the middle ear, occupied by the auditory ossicles. These three tiny bones — the malleus (hammer), incus (anvil) and stapes (stirrup) — amplify and transport the vibrations, sending them to the cochlea, a snail-shaped structure filled with fluid in the inner ear. There, tiny specialized hair cells detect pressure waves in the fluid, activating nervous receptors that send electrical signals through the auditory nerve toward the brain, which interprets the signals as sounds.

Olfactory nerves

Nasal cavity

Auditory nerve

Auditory canal

Cochlea

Specialized receptors within our skin relay tactile sensations to our brain via peripheral nerves.

Thought to be the first sense that humans develop, touch consists of several distinct sensations communicated to the brain through specialized neurons in the skin. Our skin is made up of three major layers of tissue: the outer epidermis, middle dermis and inner hypodermis. Within these layers, specialized receptor cells detect tactile sensations and relay signals through peripheral nerves toward the brain. The presence and location of the different types of receptors make certain body parts more sensitive. Merkel cells and Meissner corpuscles both detect touch, pressure and vibration. Other touch receptors include Pacinian corpuscles, which also register pressure and vibration, and the free endings of specialized nerves that feel pain, itching

Circumvallate papillae Fungiform papillae

Taste bud

Taste buds on the tongue enable us to identify what we are eating. The small bumps, or papillae, on the surface of the tongue contain taste buds. The number of taste buds we have can vary widely; the average person has between 2,000 and 8,000, which are replaced every two weeks or so. Most are located on the tongue, but they also line the back of the throat, the epiglottis, the nasal cavity and the esophagus. Chemicals from food stimulate gustatory cells inside the taste buds, activating nervous receptors which send messages to the brain — in particular to the thalamus and cerebral cortex — enabling us to identify whether the food we are eating tastes sweet, sour, bitter, salty or savory.

Our eyes translate light into image signals for the brain to process. The dome-shaped cornea is transparent to allow light to enter the eye and curved to direct it through the pupil, which is an opening in the iris (the colored part of the eye). The iris works like the shutter of a camera, dilating or constricting to control how much light passes through the pupil and onto the lens. The curved lens then focuses the image onto the retina. This light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of the eye is a delicate membrane of nervous tissue containing photoreceptor cells. These cells, shaped like rods and cones, translate light into electrical signals. Cones translate light into colors, central vision and details. Rods translate light into peripheral vision and motion and enable vision in limited light. These signals travel from the retina through the optic nerve to the occipital lobe near the back of the brain. There, the visual cortex interprets them to form visual images.

From sautéed grasshoppers to fusion food, USC Dornsife scholars use taste as a passport to explore diverse cultures, histories and identities.

By Susan BellSporting miniature chef’s hats and blindfolds, my 4 -yearold son and a dozen other under-fives at his Paris public preschool gathered excitedly around a long table covered with a cheerful red-and-white checked tablecloth. They were observing “La Semaine du Goût,” an annual week-long celebration of that most French of senses: taste. Set before them were different foods representing the five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter and savory. The game was to sample each — without peeking — and correctly identify its taste.

This national awakening of the senses through the education of the palette is a perfect example of the importance French culture places on taste. Nor is it a one-off exercise. This emphasis on the cultivation of taste continues throughout a French child’s education. Each weekday, 7 million public school children receive a four-course, subsidized lunch that would be the envy of most adults worldwide.

Each meal features a different cheese course with a typical starter of artichoke hearts, lentil or beet salad. Main courses might include roast chicken with green beans or salmon lasagna with organic spinach while dessert is typically a healthy serving of fresh fruit. The foods many Americans associate with classic kids’ fare — pizza, hamburgers and fish sticks — are served in French schools once a month at most. Thus, an entire nation grows up with an appreciation for healthy food and a palette trained to enjoy a wide variety of sophisticated flavors.

More than 5,000 miles away in Los Angeles, USC Dornsife is taking the concept of taste as a teaching tool considerably further. Michael Petitti, associate professor (teaching) of writing in the Thematic Option program, is one of several USC Dornsife scholars who use taste as a passport to explore multiple cultures — all without leaving L.A.

His Maymester course “From Pueblo to Postmates” is inspired by the work of the late Jonathan Gold, the Pulitzer Prize-winning food writer renowned for his culinary explorations of the L.A. area and the historical unpacking through food of its past and the myriad diasporas that call it home.

The course provides insights into L.A.’s ethnic and cultural diversity, how that’s expressed through taste, and how the city intersects and comes together through its culinary creativity.

“You can map the history of L.A. through food,” says Petitti. “We spend a lot of time in Boyle Heights, now a predominantly Latino area but which, like much of East L.A. during the early to mid-20th century, used to be a Jewish neighborhood with numerous Kosher restaurants and food stores.”

Petitti broadens his students’ palettes by taking them to “El Mercadito de Los Angeles,” a Latino market where they taste “nopales” salsa with cactus and “chicharron” burrito — crispy, crunchy pork rinds cooked in a fiery chili sauce made with cactus and wrapped in a tortilla. They also try dried salsa garnished with pumpkin seeds and chili flakes and sample a new fusion of Lebanese and Mexican cuisine that serves up falafel made with chorizo.

In the San Gabriel Valley — a Japanese and Mexican enclave for much of the early to mid-20th century and now inhabited by a Chinese immigrant diaspora — Petitti takes his students to eat authentic dim sum.

In South L.A., students explore the prolific Mexican American and Latino food scene, eating fresh tamales and visiting a working farm in Compton — a city that was once L.A.’s agrarian heart.

Guest speakers, such as Los Angeles Times columnist Gustavo Arellano, also provide expert insider views on the evolution of different areas of L.A.

“One of the most rewarding aspects of this class is that many native Angelenos have taken it and say it opened their eyes to the city, its history, neighborhoods, cuisine, and how others live and experience it. Students discover new insights into the complexity and richness of L.A. through our readings, visits, and guest speakers, as well as their ethnographic interviews and final research projects. That nuanced, epiphanic experience of L.A. is the goal of the course,” Petitti says.

Another USC Dornsife scholar using taste as a lens to understand the city’s complexities is Sarah Portnoy, professor (teaching) of Spanish, who has been teaching Latino food culture for 12 years. Her courses put students in touch with their senses while increasing their Spanish vocabulary and widening their knowledge and experience of Latino culture.

Portnoy agrees with Gold’s description of L.A. as “a rich mosaic.”

“The wealth of Mexican cuisine here is unparalleled in the United States,” she says. “We have the largest population of Koreans anywhere outside of Seoul. We have Salvadorean, Guatemalan, Pakistani, Filipino and Japanese communities — among many others.”

This rich stew of overlapping cultures has provided the perfect springboard for the creation of fusion food, led by pioneers like Roy Choi, founder of the legendary Kogi food trucks, renowned for their Korean Mexican combos.

To sample the vast array of flavors found in the city’s Latino communities, Portnoy takes her students to visit restaurants and to meet chefs and street vendors.

She encourages students to establish a sense of place and history as she prompts them to describe the tastes they encounter.

“I ask them to find out the story behind the restaurant and then to describe the neighborhood, what the place looks like and the diners, before talking about the dish, the colors, the key ingredients, the aromas and what they evoke. Then I ask them to find a metaphor for their experience,” she says.

Portnoy extends this learning experience to her threeweek Maymester course in Oaxaca, Mexico. There, she invites students to taste and describe such unfamiliar items as crunchy “ chicatanas” (ants), smoky mezcal and spicy salsas made from a variety of local chilies.

Portnoy’s scholarship focuses on food-centered life histories. Her work was rewarded this year with a more than half million-dollar grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, shared with her teaching partner, to make a documentary series that explores culture and cuisine on both sides of the Mexico border. Abuelitas (Grandmothers) on the Borderland will be filmed in L.A. and three other U.S. cities, as well as the grandmothers’ Mexican towns of origin. Her partner in the project is Amara Aguilar, professor of journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

Earlier in 2022, Portnoy curated the museum exhibition “Abuelita’s Kitchen: Mexican Food Stories,” which showcased the role traditional dishes played in the lives of 10 Mexican and Mexican American grandmothers living in L.A. and how they passed their culinary knowledge on to their children and grandchildren.

Comprising oral histories, kitchen artifacts and recipes, the exhibition also featured a documentary produced by Portnoy and filmed by USC Dornsife alumni about the grandmothers’ relationships with food, identity and place.

“Food-centered life histories have the capacity to portray the voices and perspectives of women who have traditionally been ignored or marginalized,” says Portnoy. “This project aims to amplify the voices of a group of

indigenous, “mestiza” (of mixed indegenous and Spanish descent), Mexican American and Afro Mexican grandmothers who have cooked, preserved, and passed on Mexican food culture, while creating communities and cultures that are unique to Southern California.”

Portnoy says the project aims to capture not only traditional recipes, but how food is woven through the fabric of the women’s lives. Many of their stories are deeply moving, such as that of Maria Elena who recounts spending long hours selling tamales from a cart in Watts in South L.A. so she could feed her five young children.

Another abuelita, Merced, is filmed preparing “mole poblano” from her Mexican home state of Pueblo. Merced has not been able to return to Mexico to see her children and parents for more than 20 years, but she says the taste of this thick, savory chocolate and chili sauce connects her to them — and particularly to her mother.

“Merced can no longer touch her mother,” Portnoy says, “but still feels viscerally connected to her by this dish she taught her to make as a child.”

The documentary delivers an emotional punch: Food connects generations through tastes, recipes and traditions, but most importantly it is an act of love.

“I asked each of the abuelitas ‘What does this dish represent to you?’” Portnoy says. “They all responded, ‘Amor’ (love).”

So, taste can connect us to our family, our history and our homeland. But it can also serve as a passport that enables us to travel through time.

A prime example is Petitti’s favorite L.A. restaurant, The Musso and Frank Grill. Dripping in history, the legendary dining room was the storied haunt of literary heavyweights William Faulkner, Ernest Hemingway, Dorothy Parker and F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Hollywood greats Charlie Chaplin, Greta Garbo, Humphrey Bogart and Marilyn Monroe.

But what Petitti loves most about the place is that it still serves throwbacks to high-end cuisine of the past such as liver and onions, avocado cocktail and jellied consommé.

“You can go there and eat the kind of meal that Fitzgerald might have eaten. You can actually taste the past, which I think is absolutely fascinating,” Petitti says.

A trip to Tito’s Tacos for what is now — especially in L.A. — an outmoded version of a taco with its hard shell, ground beef, sliced or shredded cheddar cheese and iceberg lettuce, offers another path to explore the past.

“We tend to look down our noses at this classic American taco because now we want a homemade tortilla with what we now consider ‘authentic’ ingredients, probably served from a food truck,” Petitti says. But, he argues, it’s important to understand that this taco was created in the early-to-mid 20th century because Mexican immigrants to Southern California didn’t have easy access to the ingredients they would have had in their homeland.

“Again, it’s a passport to understanding a time and history and the ways that tastes adapt to circumstances,” Petitti says.