Dementia Detectives

Researchers connect the dots to predict and prevent Alzheimer’s and related diseases.

Researchers connect the dots to predict and prevent Alzheimer’s and related diseases.

“This

is our time, place and team, and together, we are transforming how we live and age.”

Dear Friends of the USC Leonard Davis School,

When it comes to making transformative changes in aging research and education, we are at the right time and place and are surrounded by the right people. Next year will mark our 50th anniversary. We’ve grown from a single master’s degree to offering 26 innovative educational pathways; from undergraduates to PhD students, demand for our programs has never been stronger. We’ve established ourselves as the global leader in aging research and education and helped to make Los Angeles a major hub for the field, as seen at this year’s Geroscience Los Angeles Meeting.

Looking forward, we are at the forefront of advancing predictive tools for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, as highlighted in our “Dementia Detectives” cover story. You’ll also read about the impact of 20 years of work in mitochondrial microproteins and the potential it offers for personalized approaches to preventing and treating diseases of aging.

None of this would be possible without our remarkable students, faculty and supporters, including Board of Councilors member Dick Cook ’72, who recently received the Dean’s Medallion for his invaluable contributions.

This is our time, place and team, and together, we are transforming how we live and age.

Fight On!

Pinchas Cohen, MD Dean, USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology

VITALITY MAGAZINE

Chief Communications

Officer

Orli Belman

Editor in Chief

Beth Newcomb

Design

Natalie Avunjian

Copy Editor

Elizabeth Slocum

Contributors

Inga Back

Jenesse Miller

Jason Millman

Constance Sommer

Cover Illustration

Matt Chinworth (c/o Theispot)

USC LEONARD DAVIS SCHOOL OF GERONTOLOGY

Dean

Pinchas Cohen

Vice Dean

Sean Curran

Senior Associate Dean

Maria L. Henke

Senior Associate Dean for Advancement

David Eshaghpour

Associate Dean of Research, Associate Dean of International Programs and Global Initiatives

Jennifer Ailshire

Associate Dean of Education

John Walsh

Assistant Dean of Research

Christian Pike

Assistant Dean of Diversity and Inclusion

Donna Benton

Assistant Dean of Academic Initiatives

Mireille Jacobson

Senior Business Officer

Lali Acuna

Senior Human Resources

Business Partner

3 Postcard A new study abroad course in Ireland and the U.K. 6 Findings Research on stress, “jumping genes” and heart health

Vital Signs Life lessons from educators John and Julia Walsh

Students Highlighting trainee researchers and an undergrad chef

A Powerhouse of Innovation Mitochondria’s mysteries revealed

Healthy Campus Choices Experts help Trojans eat better

Dementia Detectives Connecting the dots for prediction and prevention

Retirement Celebrating Professor Emeritus Jon Pynoos

Wendy Snaer 44 Providing Care & Pursuing Change Alumni advocate for older adults

Giving Name-a-Seat campaign supports auditorium upgrade

Rethinking How We Study Black Aging Lauren Brown aims to reframe the story

Send It in a Letter Low-cost mailings can reduce risky prescriptions

Pinchas Cohen Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science

Bérénice Benayoun Vincent Cristofalo Rising Star in Aging Research Award, American Federation for Aging Research

Kelvin Davies USC Faculty Lifetime Achievement Award

Julie Bates Part-Time/Adjunct Faculty Honor, Academy for Gerontology in Higher Education

Paul Irving Retirement Pioneer Award, Retirement Coaches Association

Cristal Hill, USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology assistant professor, received the Nathan Shock New Investigator Award from the Gerontological Society of America (GSA), the nation’s largest interdisciplinary organization devoted to the field of aging.

The honor is presented to early career scientists who have made outstanding contributions to new knowledge about aging through basic biological research. Hill, who joined the USC Leonard Davis School in 2023 after completing a postdoctoral fellowship at Pennington Biomedical Research Center at Louisiana State University, said receiving the Nathan Shock Award is an honor that provides encouragement and confirms she’s pursuing important research questions.

Hill investigates how dietary interventions interact with cell signaling targets to affect health and aging. In 2022, Hill and others reported in an article in Nature Communications how the hormone FGF21 is required for mice to reap the longevity and metabolic health benefits of a low-protein diet. Of particular interest to her lab is determining the unique effects of low-protein diets on the cellular and molecular changes in adipose tissue (also known as body fat) that impact metabolism during aging.

Understanding how diets and cell signaling work together to affect health could one day enable people to tailor their diet to their individual genetics, she explained.

“Let’s actually start a movement against ageism. ... Let’s face it, I would much rather be aging than the alternative.”

— Paul Nash, instructional professor of gerontology, in a video for Ageism Awareness Day on Oct. 9, 2024.

“Any preventive measure starts from the inside,” Hill said. “Learning more about which dietary interventions affect which genetic targets can help people eat for optimal health.” — B.N.

Peter Pan never grows older, Dorian Gray’s age is frozen, and Dracula is immortal. These fictional characters provided students with starting points for scientific discovery as they traveled through England, Scotland, Ireland and Northern Ireland for a summer course on the genetics of aging.

USC Leonard Davis School Professor Sean Curran led the class and encouraged students to read between the lines and consider whether real-world discoveries could support the fantastical phenomena described in the region’s famous longevity literature.

“Take vampires: They feed on blood and only at night,” said Curran, who is also the school’s vice dean and dean of faculty and research. “The goal was not to prove whether their restricted diet makes them long-lived, but to encourage students to formulate their own hypotheses about aging.”

Students visited castles, cathedrals, lochs and other Atlantic archipelago locations. They also met with leaders of longitudinal studies at universities in Scotland, Belfast and Dublin to understand the importance of measuring population health. Walking through green spaces, taking public transportation and eating local foods also gave students opportunities to gauge how different policies and practices can influence the ability to age well.

“My favorite part of the trip was visiting universities and learning more about what gerontology looks like throughout the different demographics in Europe,” said Amor Mathershed, a current USC Leonard Davis master of science in gerontology student who also earned her bachelor’s degree at the school. “This class provided a great opportunity to examine real-life cases of aging populations on a worldwide scale.” — O.B.

Carefluencers

Social media users who share online their experiences of caring for loved ones.

Francesca Falzarano, USC

Deprescribing Minimizing or stopping a medication to reduce health risks.

American Academy of Family Physicians

Adipose Tissue Otherwise known as body fat. Along with energy storage and insulation, it performs important roles in hormone function and metabolism.

Cleveland Clinic

To live past 100, mangia a lot less: Italian expert’s ideas on aging

“I want to live to 120, 130. It really makes you paranoid now because everybody’s like,

‘Yeah, of course you got at least to get to 100.’ … You don’t realize how hard it is to get to 100.”

— Professor Valter Longo

Column: Hey, Joe, it’s OK to call it quits and leave with dignity and pride

“I’m very concerned about ageism in the workplace, but I’m also concerned about people who think they have to work forever. … Giving people permission to retire is something I think we need to do.”

— Instructional Associate Professor Caroline Cicero

Ancient Greeks seldom hit by dementia, suggesting it’s a modern malady

“The ancient Greeks had very, very few — but we found them — mentions of something that would be like mild cognitive impairment. … When we got to the Romans, and we uncovered at least four statements that suggest rare cases of advanced dementia — we can’t tell if it’s Alzheimer’s.”

— University Professor Caleb Finch

Want to know your risk of chronic disease as you age? Don’t waste money trying to find out

“For the average person, genetic testing gives very limited additional value in identifying the risk of chronic disease.”

— Dean and Distinguished Professor Pinchas Cohen

Can we change how our brains age? These scientists think it’s possible

“It’s a very sophisticated way to look at patterns that we don’t necessarily know about as humans, but the AI algorithm is able to pick up on them.”

— Associate Professor Andrei Irimia

The challenges of aging with Down syndrome

“As we age, we need to assess our energy level and if we have enough support.

… Preparation is key. You can’t wait until you start feeling like you’ve had too much, or you’re getting older, or there’s a health crisis.”

— Research Associate Professor Donna Benton

Tackling the happiness problem plaguing young Americans

“A solution to the challenges of young Americans may be hiding in plain sight. … Leveraging their strengths, older adults can stand up and show up for their younger counterparts, actively seeking cross-generational connections, collaborations and alliances, building community, promoting resilience and employing their wisdom and experience to offer support and perspective.”

— Distinguished Scholar Paul Irving

‘Carefluencers’ are helping older loved ones, and posting about it New York Times

Assistant Professor Francesca Falzarano was interviewed about the growing number of people on social media who share their daily experiences caring for aging parents, grandparents or other relatives. Falzarano referred to the caregivers as “carefluencers” because they can inspire and inform their audiences about caring for aging family members.

“We all have this universal experience where we’ll need to provide care or need to be cared for at some point. Why not start thinking about it now?”

As Biden faces questions about his age, researchers weigh in on working in your 80s

“Given more time, [older adults] perform at the same level as their younger counterparts.”

— Associate Professor John Walsh

How drumboxing exercises your body and mind at the same time

“When you are doing something where you have to keep multiple short-term memories, short little programs, in mind, that’s really one of the most effective cognitive workouts that we can have for the brain.”

— Professor Mara Mather

How to help elderly parents from a distance: Tech can ease logistical, emotional burden

“Long-distance caregivers have not been adequately recognized as legitimate sources of care because of the physical distance that makes their contributions less apparent or visible. However, we have and will continue to see an increase in individuals who find themselves providing, coordinating and managing care from afar.”

— Assistant Professor Francesca Falzarano

Don’t expect human life expectancy to grow much more, researcher says “For me personally, the most important issue is the dismal and declining relative position of the United States.”

— University Professor Eileen Crimmins

45%

Portion of human genome made up of rearrangeable “jumping genes”

A USC Leonard Davis School-led study highlights how transposons — commonly called “jumping genes” because of their ability to move to different parts of the genome — are associated with age-related disease and decline, as well as how additional genes governing transposon expression may one day be therapeutic targets for aging.

USC Leonard Davis Associate Professor Bérénice Benayoun and colleagues cross-referenced the genes IL16 and STARD5, which were suspected to regulate transposon activity, with transcriptomic and genomic data from more than 400 individuals. The results paint a clear picture of the relationship between increased expression of the transposon LINE-1, expression of its suspected regulatory genes, and signs of accelerated aging.

“This study sets a new framework for studying transposons and adds to the body of evidence showing that transposable element activation is contributing to aging,” Benayoun said. “This approach can be used on bigger cohorts of data, which opens the door to finding more of these regulators. From there, we might be able to identify actionable therapeutic targets for aging and age-related diseases.” — B.N.

A recent study highlights possible cardiovascular health advantages in individuals with a rare condition known as growth hormone receptor deficiency (GHRD), also called Laron syndrome.

Over the past two decades, Valter Longo, professor of gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology, and endocrinologist Jaime Guevara-Aguirre of the Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Ecuador, have examined the health and aging of a group of Ecuadorians with the gene mutation that causes GHRD, which results in a type of dwarfism.

Key findings from the latest study:

• GHRD subjects displayed lower blood sugar, insulin resistance, and blood pressure compared with the control group.

• They also had smaller heart dimensions and similar pulse wave velocity — a measure of stiffness in the arteries — but had lower carotid artery thickness.

• Despite elevated low-density lipoprotein (LDL), or “bad cholesterol,” levels, GHRD subjects showed a trend for lower carotid artery atherosclerotic plaques.

“These findings suggest that individuals with GHRD have normal or improved levels of cardiovascular disease risk factors compared to their relatives,” Longo said. — B.N.

How does the stress of a less-forgiving environment affect cells? Simply hardening the surface on which tiny worms grow offers possible insights into aging, cancer and more, according to a USC Leonard Davis study.

“The study of mechanical stress is important because many tissues become stiffer with age, and several age-associated diseases — like cancer — are associated with increased tissue stiffness,” said Assistant Professor Ryo Sanabria, the senior author of the study.

Mechanical stress refers to any type of physical stress, such as tension, torsion, bending, twisting, or exposure to stiffer environments, said co-first author of the study Maria Oorloff ’24.

Oorloff, who recently completed her bachelor of science in human development and aging at the USC Leonard Davis School within the USC Gerontology Enriching Medicine, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (GEMSTEM) to Enhance Diversity in Aging program, was co-first author with Adam Hruby, biology of aging PhD student.

“This project was extremely rewarding and an opportunity for me to expand my knowledge on the work that goes into a project in a basic science lab. Going into it, I had no expectations, and I found that a lot of our findings were impactful in how C. elegans move and function,” Oorloff said. “I hope this research one day can help scientists understand cancer cell growth and survival, leading towards the betterment of drugs for treatment.”

The researchers sought the simplest method to apply mechanical stress for the microscopic nematode worm model organism C. elegans. They grew animals on a surface created to be four times stiffer than the standard substrate and compared their physiology to animals grown in standard growth conditions.

Several health metrics were lower for animals grown on stiffer substrate, including reduced reproduction and muscle function. However, the animals grown in the stiffer environment with more mechanical stress also had longer lifespans.

This surprising increase in longevity may be due to an increase in stress resilience and altered function of several cellular components, including the mitochondria and the actin cytoskeleton. The actin cytoskeleton is the network of proteins bound together in filaments that determines a cell’s shape and enables cellular movement and division.

“I initially thought that lifetime exposure to increased substrate stiffness would lead to an overactivation of stress response pathways, taxing the animal and leading to a shorter lifespan,” Hruby said. “We instead found a slight increase in lifespan which were dependent on changes to the actin cytoskeleton, which is consistent with previous research showing mechanical stress can cause alterations in actin filaments.”

The study has significant clinical potential, Sanabria said.

“Importantly, many of the changes that we see in C. elegans exposed to stiffer substrates are very similar to those found in cancer cells,” they said. “If we could identify candidate drugs that reverse the phenotypes found in C. elegans exposed to mechanical stress, it is possible that these drugs can similarly inhibit cancer cell growth and survival.” — B.N.

Above: The actin cytoskeleton, a network of proteins bound in filaments that gives a cell shape and enables its movement and division, is known to respond to mechanical stress.

The USC Family Caregiver Support Center (FCSC) has created a free caregiving training program to improve the skills and career opportunities for both paid and unpaid caregivers in Los Angeles County, especially for those who care for older adults with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias.

director of the FCSC and a research associate professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology.

The USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology received $3 million from the Administration for Community Living to support family caregivers in maintaining financial stability and workplace security.

Funding will be used to develop and curate various resources and tools, including a website offering comprehensive information tailored to caregivers’ diverse needs. The project will foster partnerships among several leading organizations as well as national, state and local aging networks.

“This award is a recognition of the critical role caregivers play in our society and the need to support them effectively,” said Professor Kathleen Wilber, the Mary Pickford Foundation Chair in Gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School. “We will expand our research and collaboration efforts to create a more supportive environment for caregivers.”

Value of unpaid care provided by family caregivers each year in the U.S.

FCSC’s training program tackles common challenges faced by caregivers, such as transportation, child care, access to technology and the cost of training. By offering financial help and various ways to access training, including online and in-person sessions, the program is designed to make it easier for caregivers to participate. The program is funded by the CalGrows workforce training and development grant program, part of California’s Master Plan for Aging.

According to U.S. government data, approximately 53 million people serve as family caregivers, including 5.5 million caring for service members and veterans. Family caregiving can negatively impact caregivers’ health, emotional well-being and financial stability, with women, who make up nearly two-thirds of caregivers, being particularly affected. AARP estimates that family caregivers provide about 36 billion hours of unpaid care, valued at over $600 billion a year.

USC Family Caregiver Support Center Director Donna Benton is overseeing efforts to ensure that diversity, equity, inclusion and access are central to all product development and dissemination efforts. USC Leonard Davis Assistant Professor Francesca Falzarano is identifying and implementing relevant technology innovations, while Associate Professor Susan Enguídanos heads the Work Group on End-of-Life/Intensive Caregiving. — O.B. $600B

“We are excited to offer this program that addresses the real needs of our diverse caregiving community,” said Donna Benton,

Q: What’s the main focus of your research here at the USC Leonard Davis School?

A: My work focuses on how psychological and social factors throughout the life course shape cognitive aging and dementia risk. To reduce inequities in the burden of dementia, I am interested in understanding these relationships in diverse populations, including groups that are often underrepresented in research. I also have a line of work focused on epidemiologic methods to improve causal inference and generalizability of findings in dementia and cognitive aging research.

Q: What are some of the Alzheimer’s risk factors that you study?

A: I am interested in adverse experiences in childhood, such as household dysfunction or maltreatment, and exposure to traumatic and stressful experiences throughout life, like life-threatening accidents, interpersonal violence or serious illness of a loved one. These are common experiences in the U.S. and globally, and often disproportionately experienced by groups that also experience elevated burden of dementia. I am also interested in factors that may buffer against the impact of trauma and stress, like social support or physical activity. Dementia pathology likely begins decades before clinical symptoms, so understanding sources of risk and resilience starting in childhood and early adulthood, in addition to later-life exposures, is critical.

Eleanor Hayes-Larson PhD, MPH Assistant Professor of Gerontology

Q: Why is it important to know how trauma and other factors can affect cognitive decline?

A: Long term, understanding the impact of trauma and related factors on cognitive decline will help us understand the etiology of dementia and inform prevention approaches. In addition, identifying factors in late life that support resilience against the negative impact of earlier trauma and stress on cognition may be helpful for identifying strategies to preserve cognition in older populations who have lived through such experiences. For example, I am interested in whether social support or financial stability in late life might be important sources of resilience.

Q: What are some of the next big questions coming up in epidemiological research on Alzheimer’s?

A: New biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease and neurodegeneration are being developed all the time, and figuring out how to best incorporate them into population research is important for connecting psychosocial exposures to changes in the brain that lead to dementia. In addition, recruitment of samples with greater diversity is important for ensuring that results of studies, including potential advances in treatments, can help all older adults live healthier lives.

“There is no time like the present for students to make financial and lifestyle decisions that will reduce their risk of many diseases of aging and allow them to lead fulfilling lives.”

— John Walsh, USC Leonard Davis School associate professor

GERO 200 provides students with a roadmap for navigating aging.

John Dionisio didn’t expect to be charting the growth that compounding interest can add to a 401(k) when he signed up for GERO 200, “The Science of Adult Development,” as a USC undergraduate student. But graphing this wealth-increasing investment strategy is a key assignment in the popular undergraduate elective course, which teaches students how to support — and become — older adults.

“I did not have any financial literacy before taking this class,” said Dionisio, who graduated as a lifespan health major from the USC Leonard Davis School in 2021 and is now earning his doctor of physical therapy degree at USC.

Dionisio says the assignment and the course in general provided a solid foundation for moving to the next stage of life and preparing for changes that come with aging.

That’s exactly the goal and the reason the course is often referred to as “Life Skills.”

Taught by Associate Professor John Walsh and USC Leonard Davis lecturer and attorney Julia Walsh, the class covers the impacts of aging from the perspectives of biology, economics, policy, business and society.

“Knowledge is power,” said John Walsh. “This course is built on the idea that there is no time like the present for students to make financial and lifestyle decisions that will reduce their risk of many diseases of aging and allow them to lead fulfilling lives where they can do all the things they want to do.”

In the course, which is offered online three times a year, the Walshes use personal insights, population data and planning tools to give today’s students tools to be healthy adults. John Walsh shares some of the main lessons with us here:

“One of the best things you can do for your future self is to start financial planning now. The reality is that aging comes with financial challenges, whether it’s the cost of caregiving or relying on Social Security. Creating a financial plan, like setting up a Roth IRA, can set you on the path to financial stability. Starting early means you can take advantage of compound interest and feel more secure in your retirement.”

“The choices you make today—what you eat, how often you exercise, how you manage stress—can have a huge impact on your health as you age. Things like obesity and poor diet are major risk factors for diseases such as diabetes, heart disease, and even Alzheimer’s. Making small but consistent lifestyle changes now can decrease your risk for these age-related conditions and allow you to keep doing the things you love for longer.”

TAKE MENTAL HEALTH SERIOUSLY

“Mental health is something we all deal with, no matter who we are or how old we are. Recognizing mental health challenges — whether it’s clinical depression or other issues — can lead to methods that help us manage them. In aging populations, mental health often gets overlooked, but conditions like depression can increase the risk for diseases like diabetes and cardiovascular problems because it disrupts lifestyle. By educating students on brain health, particularly neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, we aim to show that it’s never too early to reduce risk. Living a healthy lifestyle today can have a significant impact on brain health in the future.”

“Caregiving might not be something you think about now, but it can be a major part of life as your parents or grandparents age. It’s not just a personal commitment; it’s a financial one, too. Many people find themselves unprepared for the costs and emotional toll of caregiving. Being aware of this responsibility and discussing it with your family can help you plan ahead.”

“One of the most practical things you can do is to start talking with your family — especially older relatives — about their health, finances, and plans for the future. These conversations can be tough but are essential for preparing for what lies ahead. Understanding their wishes and needs helps you make better decisions and fosters stronger relationships across generations.”

Former student John Dionisio has taken these lessons to heart and feels that no matter their major, all students can benefit from the longevity literacy that GERO 200 imparts.

“Everyone should take this course,” he said. “It lets you know what to expect as you age and gives you the tools to prepare.”

— O.B.

“Food in general is so important to the

and

lifespan,

what you eat and what goes in your body reflects on how you age.”

— Jordyn Roberson ’25, owner and chef of Jordie’s Joint

For chef and USC Leonard Davis student Jordyn Roberson, feeding the community and studying aging is a satisfying combination.

As a student at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology as well as a chef and business owner, Jordyn Roberson has a lot on her plate.

Roberson, a senior majoring in human development and aging with a minor in nutrition and health promotion, started her catering and meal-prep business, Jordie’s Joint, in fall 2022. Prior to launching her own business, she had been cooking from a young age and had begun blogging about food and fitness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Alongside her busy school schedule, she provides meal-prep services, caters events and sells mouthwatering meals at pop-up events on the USC campus. During one such event, held in February 2024 at SC Black Flea in honor of Black History Month, the menu included marinated jerk chicken wings, creamy baked mac and cheese, stewed cabbage and caramelized plantains.

“Coming to an event like this means community,” Roberson said during the pop-up. “It means serving people, and that’s what makes me happy: just being able to feed everyone and put a smile on their face.”

Since then, her business has continued to grow. Roberson recently catered her largestever event, preparing more than 150 meals for the USC football team, and she’s also preparing to cater a wedding for the first time. Additionally, she is now an award-winning chef,

having earned the Best Mac and Cheese title at the 626 Dena Day market in June 2024.

Now, as she gears up for her USC graduation, she’s balancing school and her business alongside a 12-week accelerated culinary education program. She’s also interning with Hydro Gummy, a nutrition-based startup that promotes “water you can eat,” a helpful hydration supplement packaged as a tasty snack and intended for older adults with dysphagia, swallowing problems or other hydration challenges. Additionally, she’s a student researcher in the lab of Assistant Professor Cristal Hill and is studying the effects of a low-protein diet on the body’s metabolic processes.

Following graduation, Roberson says she’d like to enroll in graduate school and become a registered dietitian nutritionist, eventually blending her knowledge and her experience with Jordie’s Joint to start a nonprofit nutrition-assistance and meal-prep organization focused on fighting chronic illnesses through dietary interventions.

“I would like to create medically tailored meals for individuals and heal them through food. Hopefully, then I could collaborate and work with programs like Meals on Wheels and build a large network,” she says. “Alongside this, depending on how Jordie’s Joint continues to operate, potentially, I would like to operate a small restaurant or expand into a larger business.”

For Roberson, studying gerontology while running her business has highlighted how crucial food is to the process of aging well.

“Food in general is so important to the lifespan, and what you eat and what goes in your body reflects on how you age,” she says. “Knowing how to cook and learning what to cook is very important to how you age.” — B.N.

Scientists from across Southern California gathered for the second annual Geroscience Los Angeles Meeting (GLAM), a daylong conference spotlighting the work of students and trainee aging researchers, on Sept. 6, 2024, at the California Science Center.

GLAM featured research talks by trainees, a student and trainee poster session, and two-minute flash talks by undergraduate researchers. More than 400 registrants representing 29 institutions attended, including USC, UCLA, Cedars-Sinai, UC Riverside, UC Irvine, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute, UC San Diego, and Loyola Marymount University.

Janeel Calzaretta, a USC BS in neuroscience and MS in global health student, said she found participating in GLAM particularly valuable in regard to learning about paths in geroscience.

“Attending discussions deepened my understanding of the biological processes that drive aging while also highlighting a unique level of academic and professional rigor that drives research forward,” said Calzaretta, a Gerontology Enriching Medicine, Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (GEMSTEM) scholar conducting research in the lab of USC Leonard Davis School Assistant Professor Constanza Cortes.

For more info and recipes, follow @jordiesjoint

Giving students at all levels and postdoctoral researchers opportunities to present research and network is a key focus for the annual event, as other scientific meetings focus on presentations by established researchers and faculty members, according to USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology Vice Dean and Professor Sean Curran, Associate Professor Bérénice Benayoun, and Assistant Professor Ryo Sanabria, the event’s organizers. The event was organized by the Los Angeles Aging Research Alliance, a partnership among USC, UCLA, Cedars-Sinai and other area organizations involved in aging research to promote age-related advances and improve health and well-being across the lifespan. Event sponsors included the Hevolution Foundation and the USC-Buck Nathan Shock Center as well as VWR, Miltenyi Biotec, Active Motif, Caron Scientific, and 10X Genomics. — B.N.

By

WE ALL KNOW THE DRILL: You go to the doctor’s office, and before you ever see a physician, a nurse slides a cuff on your arm and takes your blood pressure. The result gives some insight into your risk for a heart attack or a stroke.

But what if that result could also reveal your risk for developing Alzheimer’s?

A blood pressure reading at a moment in time doesn’t tell much, says Daniel Nation, the Merle H. Bensinger Professor of Gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. But Nation’s research shows that charting how blood pressure varies may offer insights on brain health.

“We have found that your variability in your blood pressure — how much it changes, beat to beat, minute to minute, even within a single heartbeat — is a major risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia,” he says.

Think of them as “dementia detectives.” USC neuroscientists like Nation pore over clues, determined to piece together the facts that will reveal dementia’s modus operandi. Some study possible dementia triggers, such as traumatic brain injuries, vascular degeneration and air pollution. Others examine the role of the musculoskeletal system, or genetics, or fingernail-size brain centers, or the effect of sex differences in the development of Alzheimer’s. But they share a common hope: that their research will help reveal if, when and how dementia will strike.

“The processes that take place in the brain after a traumatic brain injury also age the brain. ... The question is whether TBI could lead to changes in brain biology along trajectories that increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s.”

— Associate Professor Andrei Irimia

Vascular disease affects the brain’s blood vessels and is a common cause of dementia. But how does one lead to the other, and can we tell if someone’s at risk? These are questions Nation is trying to answer.

The brain, he explains, cannot store energy. Instead, it gets it “on the fly” from nearly 400 miles of blood vessels that ribbon through and around it, he says. That makes the brain “very vulnerable to any kind of vascular problem,” Nation says.

There are two main ways someone can develop vascular dementia, he says. One is from a stroke, or a series of strokes, that causes accumulated destruction to the brain’s memory centers. The second way is small vessel disease. This is when the brain’s small blood vessels start to degenerate, leading to extensive damage to the white matter that connects the different parts of the brain, Nation says. It’s often only clear as symptoms of cognitive decline begin to show. Many dementia patients have both small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s, he says.

Some of Nation’s research is focused on angiogenesis, the process by which blood vessels repair and even regrow. By growing brain blood vessels in a dish, he says, his lab is hoping for findings that “may generate new ideas that are totally different types of [dementia] interventions” than we currently have.

Nation also wants to understand how and why vascular dementia develops, and to create tools to track it as it’s happening. Graphing blood pressure variability over a period as short as seven minutes offers clues into the presence of small vessel disease, he says. It’s not

yet clear whether the vessel damage is due to surges in blood pressure that damage vessel walls, or the dips in pressure that repeatedly deprive the brain of blood flow, he says.

Either way, the issue “is currently not treated, because all of the treatments are just based on average pressure,” he says. Were physicians to begin treating such variability, “it would have a big effect, potentially,” he says, “because we have consistently observed high blood pressure variability as a risk factor.”

Another risk factor for dementia is brain injury. Nation’s colleague Andrei Irimia is studying the risk that traumatic brain injuries, or TBIs, pose for the development of Alzheimer’s, while also exploring possible interventions that can prevent the worst effects of TBIs from happening at all.

“The processes that take place in the brain after a traumatic brain injury also age the brain,” says Irimia, associate professor of gerontology, quantitative and computational biology, biomedical engineering and neuroscience. Such processes, like brain swelling and inflammation, are also present in Alzheimer’s disease, he says.

“The question is whether TBI could lead to changes in brain biology along trajectories that increase the risk” of developing Alzheimer’s, he says.

In this, and in his effort to more broadly examine neurodegeneration, Irimia has harnessed the power of artificial intelligence. His team has used a neural network — an AI model that “learns” through intensive, complex data analysis — to identify novel aspects of aging that may predispose people to developing Alzheimer’s. Irimia

Number of people who have dementia worldwide, according to the World Health Organization.

has also mapped how genetics interact with brain structure to increase or decrease Alzheimer’s risk.

“Obviously, there’s a lot more work to do” with neural networks, he says. “This is a very new field.”

One day, physicians may be able to use such deep, detailed brain imaging to identify people whose brains are aging quickly or abnormally, while they are still cognitively normal.

“It could reduce the risk for Alzheimer’s for individuals who might be at higher risk,” he says, “but who may, by virtue of these interventions, be assigned to a trajectory of aging that does not eventually lead to dementia.”

Anthropology and genetics provide leads

Irimia’s quest to understand dementia has led him to the Amazon basin in Bolivia, where he’s studied the Tsimane people, who live a preindustrial lifestyle that features high levels of physical activity and a healthy diet devoid of highly processed foods. “Despite the fact that they have more infectious disease, due to lack of access to modern medicine, they also have far lower rates of dementia,” he says.

It appears that their lifestyle is protective of brain health in a way our industrialized lifestyle is not, he says.

“The Tsimane, and other preindustrial societies where being sedentary is not the norm, can teach us a lot about how lifestyle and factors related to industrialization, the consumption of processed foods that is so pernicious in modern societies — how all these factors can actually influence dementia risk,” he says.

University Professor Caleb Finch, the ARCO/William F. Kieschnick Chair in the Neurobiology of Aging, also

studies the Tsimane and the long-term effects of modern society on the brain. It’s part of Finch’s lifelong quest to understand the mechanisms of human aging — including the roots and triggers of Alzheimer’s.

Even in our more sedentary, industrialized societies, exercise and diet mitigate Alzheimer’s disease risk, Finch says. “We were the first to show that if you take an ordinary mouse with human Alzheimer’s genes and put it on a low-fat diet, there are much fewer Alzheimer’s changes in the mouse’s brain,” he says.

Those same mice had to work in their cage to get food, and they were incentivized because they were hungry, he says. Similarly, people who are physically active and have low body fat are at lower risk for dementia than those who are more sedentary and heavier, he says.

Another known risk for Alzheimer’s is air pollution. Finch’s research traced the pathways in the mouse brain that air pollution uses to accelerate Alzheimer’s-like changes. His findings showed this can happen in mice who are only exposed prenatally.

Over and over, Finch’s research points to one weapon against Alzheimer’s: lifestyle prevention.

“We don’t really have any interventions for Alzheimer’s other than lowering the risks by lowering the risk of heart disease,” he says. “All of what is good for the heart is good for the brain, and what is bad for the heart is bad for the brain.”

Historically, Alzheimer’s has been a rare condition, he says. Only a “very few and rare genes” destine a small number of people to develop the disease, usually in their 30s and 40s, he says. But in modern societies, “we can see at least a fivefold increase in the risk of serious

60%

The APOE4 gene increases risk of Alzheimer’s, to the extent that people who carry two copies of APOE4 have a 60% chance of developing the disease by age 85.

cognitive impairment at later ages,” he says. “This is environmental.”

A gene called APOE4, which is known to increase the likelihood of Alzheimer’s in industrialized populations, doesn’t appear to get triggered in that way in the Tsimane. Instead, it seems to have somewhat of a protective function, Finch says.

Young Tsimane women who have the gene are able to bear more children, despite the highly infectious environment, he says. “So in some conditions, the Alzheimer risk gene is protective from infections,” he says.

Understanding the role of the APOE4 gene — and its companions, APOE3 and APOE2 — looks increasingly like an important piece of the Alzheimer’s puzzle, says Christian Pike, professor of gerontology and assistant dean of research.

Pike began his career studying beta amyloid, the protein that forms the plaques found in Alzheimer’s brains. These days, though, his attention and his research are centered on the family of APOE genes because they are “a really significant regulator of longevity,” he says.

The APOE3 gene is neutral for Alzheimer’s; the APOE2 gene is protective against the disease; and the APOE4 gene increases the disease risk, to the extent that people who carry two copies of APOE4 have a 60% chance of developing Alzheimer’s by age 85. Much of Pike’s recent research looks at diet and pharmaceutical interventions that can blunt or even reverse the effects of the APOE4 gene in genetically engineered mice.

One intriguing study looked at what happened when mice bred with human versions of APOE genes were treated with an estrogenrelated molecule called 17a-estrodial. Certain mice that were given this drug at the onset of middle age later showed improved cognition and reduced brain damage from destructive proteins, Pike says. The benefits of the drug were limited to mice who had the APOE4 gene, and the effects were stronger in male mice than in female ones, Pike says.

In other studies, Pike and Associate Professor of Gerontology Changhan Lee are looking at the impact of a fasting diet on Alzheimer’s, as well as the effects of a microprotein called MOTS-c, which may also have a role in obesity and diabetes, according to research by USC Leonard Davis School Dean and Distinguished Professor Pinchas Cohen.

The work is complex because mice are not exact stand-ins for humans, Pike says. For instance: Female mice, like almost every other animal on the planet besides humans, don’t go through menopause. And male mice don’t age in the same way male humans do, either.

“They’re models, and incomplete models, because they can only model specific components of a condition,” he says. “When you get something as complicated as Alzheimer’s disease, you can’t include all the different components that you want.”

So, one experiment will look at the effects of aging, and another at Alzheimer’s pathology, but marrying the two in one experiment can be tricky if not impossible, given other variables, he says.

“You can only answer so many different questions at a time, and

then you try to make conclusions based on some sort of composite of several different pieces, but we can’t put it all together yet,” he says.

Untangling neurotransmitters, hormones and endocrine disruption

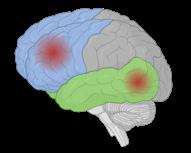

Mara Mather, professor of gerontology, psychology and biomedical engineering, is investigating the role and functions of the locus coeruleus, a small part of the brain stem that plays a large part in dementia. The tiny bluish region (its name translates as “blue spot”) is one of the first places where Alzheimer’s pathology occurs in the brain. (Mather cites research from 2011 that showed precursors of Alzheimer’s in brains of people in their 30s.)

Mather’s lab is analyzing pupil dilation, since that is one indication the locus coeruleus is activated. Perhaps these and other signs of locus coeruleus function could be used as early indicators of Alzheimer’s, she says.

“We don’t really have any interventions for Alzheimer’s other

than lowering the risks by lowering the risk of heart disease. All of what is good for the heart is good for the brain, and what is bad for the heart is bad for the brain.”

— University Professor Caleb Finch

“The ideal next step would be to target the locus coeruleus in interventions,” she says. “Can you be doing things that really benefit the locus coeruleus in particular?”

The locus coeruleus produces neurotransmitters that activate the brain’s hippocampus region, a site of learning and memory. The hippocampus is another site in the brain where Alzheimer’s disease first becomes apparent, and a region that Teal Eich, assistant professor of gerontology and psychology, studies as she tries to unravel a bedeviling scientific mystery: Why does Alzheimer’s affect more women than men?

A 2021 pilot study shed some light. Women’s cognitive abilities were associated with levels of a key neurotransmitter, gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), in the hippocampus, such that lower levels of GABA predicted worse memory. This wasn’t the case for men. The pilot study involved only 20 participants, but preliminary data from a larger study of more than 300 participants is

showing the same results, Eich says.

“That led to the question: What might be happening in women versus men?” she says.

Alzheimer’s researchers have found that women’s susceptibility to many frailties and diseases increases significantly after menopause, when estrogen levels drop dramatically. But estrogen levels can’t be the only reason behind the GABA results, because all women who live long enough go through menopause, but not all of them get Alzheimer’s, Eich says.

“There have to be other factors that are influencing this, that are changing the trajectory of estrogen or the timing of it or how it’s impacting brain function,” she says.

That set Eich on a new research path, one she’s still in the process of funding: How are pollutants and human-made toxicants impacting menopausal women, and what connection might that have to GABA levels in the brain?

Dementia isn’t a specific disease but is an umbrella term for memory loss and declines in other cognitive abilities that are severe enough to interfere with daily life. Progressive dementia comes in several forms, including the following:

Alzheimer’s disease, characterized by amyloid proteins clustering together into plaques within the brain, is by far the most common type of dementia, contributing to 60-70% of dementia cases.

Vascular dementia is found in as much as 20-30% of dementia cases worldwide and is the result of reduced blood supply in the brain, often due to multiple small strokes or blood clots.

Sources: Alzheimer’s Association, Mayo Clinic

Dementia with Lewy bodies contributes to 1015% of dementia cases. Lewy bodies are abnormal clusters of the protein alphasynuclein that build up inside neurons within the brain.

Frontotemporal dementia refers to subtypes of dementia caused by nerve cell damage in the frontal lobe (the brain region closest to the forehead) or the temporal lobes (the regions near the ears). It contributes to 10-20% of dementia cases.

Mixed dementia refers to the presence of signs of multiple types of dementia. Recent research indicates that as many as 50% of dementia cases could involve more than one type of dementia pathology, and likelihood of mixed dementia increases with age.

Many of these chemical compounds are endocrine disruptors, “and there’s a lot of work on how they impact fetuses in utero and how they affect childhood development,” she says, referring to research showing possible links between such chemicals and changes such as childhood obesity and early puberty.

“But there’s almost no research of how [endocrine disruptors] affect women in menopause,” Eich says. She’s hoping to change that by studying whether exposure to certain toxins affects women’s hormone levels in midlife, and how that, in turn, might impact brain function, she says.

Once the function of GABA, and its relationship with estrogen, is better understood, researchers may be able to target GABA levels with pharmaceutical interventions, Eich says. This gets to a larger question of aging, she says. Just as one person’s skin wrinkles faster than another’s, or one person’s hair goes grayer earlier than a friend’s does, so, too, may other, less visible parts of our bodies age at different rates, researchers are starting to understand.

Eich wonders about endocrine age, especially as it applies to women. If GABA levels predict cognitive function in women but not in men, that could mean GABA is also connected to women’s hormone levels. And that could mean, Eich says, “that maybe endocrine age is going to be a good predictor of brain health.”

Putting the pieces together for prevention

Exercise and how the body’s fitness affects the brain is a key focus of research for another USC Leonard Davis school scientist, Constanza Cortes.

“The ultimate goal of my lab is to develop what I like to call ‘exercise in a pill,’” says Cortes, assistant professor of gerontology.

One of the most powerful preventions against dementia is exercise, Cortes says, but in our often-sedentary society, few people move enough. Some people find themselves constrained by work and care obligations, others by access to gyms or safe outdoor spaces. Older people may have mobility challenges on top of that, she says.

“If we could develop a pill that gives you those same benefits, you can just take that drug and get the benefits of exercise, hopefully, without having to get on a treadmill,” she says.

For too long, she says, neuroscience research has ended at the neck. But scientists know that when the body moves, one system starts talking to the other: the muscles to the endocrine system, the organs to the blood. “Now, we’re starting to see that the brain is actually involved in those conversations much more deeply than we ever knew,” she says.

This may be coming into play with the plaques that show up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients. Cortes compares the plaques to trash that builds up in sections of the brain. “We think that one of the ways that exercise is good for you is that it is telling the brain — essentially, the trash truck — to ‘Hey, go pick that trash up; it’s sitting over there,’” she says.

Cortes models Alzheimer’s in mice, and she’s found that when they run on wheels in their cages, plaques in their brain shrink, and

“We think that one of the ways that exercise is good for you is that it is telling the brain, ‘Hey, go pick that trash up; it’s sitting over there.’”

— Assistant Professor Constanza Cortes

“Data suggests that we all should be thinking about [Alzheimer’s] more as a general health issue: the health of our brain.”

— Professor Mara Mather

even disappear. “That gives us a really good target so we can modulate and change these disease-associated markers,” she says.

The next step is to pinpoint messengers between the muscles and the brain, because “if we can figure out what the messengers are, I can mimic it with a drug and make a pill for it that mimics the effects of exercise,” she says.

Recently, Cortes’ lab has found one that seems to work in mice. “We’re pretty excited because that means we have a target to go after,” she says. In the coming year, her lab will begin work on developing a version of the medicine for humans, she says.

Eventually, she hopes, physicians will hand at-risk patients a pair of prescriptions: one an exercise-imitating pill, and another a personalized exercise plan. Even with a drug at hand, movement will remain important, she says, and it’s never too late to start.

“No matter how old you are, or how sedentary you are, any kind of increase in your physical activity levels will give you a benefit,” she says. “Even if the only thing you can do is walk around your apartment for a couple of minutes every day, that is better than not doing it.”

Mather also has a whole-body perspective as she investigates how the nervous system’s “fight or flight” mechanism plays a role in dementia.

The autonomic nervous system has two parts: the sympathetic and the parasympathetic. The sympathetic is what we use to move, to generate energy and ideas, and, in times of crisis, for emergency responses like “flight or fight.” The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for helping us digest food, calm down and rest. In other words, it undoes the excitable work of the sympathetic nervous system. Both branches of the nervous system are essential for health and emotional well-being, but as we age, the parasympathetic begins to deteriorate.

“You can think of it like, if you’re doing a really hard physical workout, the sympathetic system is involved quite a bit,” says Mather. “But if you worked out to the max every day without resting, your body would completely fall apart.”

Rest is important for restoring that damage; the trouble, she says, is when your body becomes less effective at making that rest happen.

“My question is, how much can we restore that balance, and how will that influence the progression towards [preventing] neurodegenerative disease?” she says.

To that end, Mather studies heart rate variability, which decreases as the parasympathetic system deteriorates. Simple breathing exercises can increase heart rate variability while simultaneously decreasing in the blood the proliferation of the amyloid beta peptides linked to the Alzheimer’s disease process, Mather and colleagues found in a 2023 study.

All in all, the data on Alzheimer’s points increasingly in one direction, Mather says. “It suggests that we all should be thinking about [Alzheimer’s] more as a general health issue,” she says. “The health of our brain.”

Brain health — it’s a relatively new concept, but within it may lie the key to unlocking many of dementia’s greatest mysteries. How do vascular changes impact brain health? Traumatic brain injuries? A declining parasympathetic nervous system? Sex hormones?

We already know that sleep, diet, exercise and stress can impact our brains as we age. But what else are we missing? And what more can yet be done?

One day, Pike predicts, his and others’ work will probably result in a pill or pills to reduce or eliminate the symptoms of Alzheimer’s. But even then, he adds, physicians will probably still tell patients to maintain two tried-and-true prevention practices.

“We’ve known for a long time that the best prevention is diet and exercise,” he says. “It’s not that I don’t believe in beta amyloid anymore. I absolutely do. At the same time, I think of this more holistically: that Alzheimer’s is not just a brain disease; it’s a whole-body disease.”

Photo: Chris Shinn

How a serendipitous discovery more than 20 years ago led to a new chapter in biology and made the USC Leonard Davis School a leading force in unraveling the mysteries of mitochondria.

BY BETH NEWCOMB

It’s a simple statement, but it’s true: “Perseverance is the key to scientific success,” says Pinchas “Hassy” Cohen, dean of the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and USC Distinguished Professor of Gerontology, Medicine and Biological Sciences.

He would know. Nearly 25 years ago, Cohen — a professor at UCLA at the time — led a study on a growth hormone called insulin-like growth factor (IGF) that unintentionally revealed the existence of a small peptide called humanin. But this tiny protein wasn’t coded for in the DNA within the cell’s nucleus; it arose from the separate, smaller genome within the mitochondria, organelles known primarily for their function as energyproducing “powerhouses” of cells.

Humanin’s source in the mitochondrial genome, 16S rRNA, wasn’t initially thought to be a region that could code for proteins at all. The notion that it could code for humanin and similar “microproteins” was initially met with a great deal of skepticism from others in the scientific community, recalls Cohen, who joined the USC Leonard Davis School in 2012. It took many years of subsequent research from Cohen and colleagues for the wider field to accept that 16S, as well as other similar regions of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, could produce tiny proteins with huge roles in metabolism, aging and age-related diseases.

“People now recognize that there are these things called small open reading frames, and that they can express small proteins, or microproteins. This opens up the human genome, originally thought to contain only 20,000 genes, and increases it by at least two orders of magnitude,” Cohen explains. “And in the mitochondrial DNA, where we primarily work, there used to be thought to exist only 13 protein-coding genes that are all involved in the mitochondrial biology. Now, we think there are approximately 700 of them.”

What started as an inadvertent finding has, after weathering years of skepticism and sparking the interest of more and more researchers, started a new era in biology and drug discovery, he says.

“The discovery of microproteins that we made 25 years ago and have built upon now was a real, unique body of work that represents a new chapter in biology,” Cohen says. “It really changes how we look at genetics and transcriptomics and proteomics. It completely reshuffles the deck, if you will.”

Mitochondria aren’t simply energy factories for our cells; they also have important roles in metabolism, cell death, communication between cells and more. Their small, circular genome and their complex abilities reflect their evolutionary origin — before they were mitochondria, they were bacteria that were engulfed by larger cells to form a symbiotic relationship, which happened 1.5 billion years ago. This significantly upgraded ancient organisms’ ability to extract energy from food sources, allowing a more complex system to exist.

“Because mitochondria used to be bacteria themselves, they appear to retain some ability to sense their environment and communicate information to other mitochondria,” Cohen says.

Mitochondria’s communication skills are of particular interest to Changhan David Lee, associate professor of gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School. Originally trained as a microbiologist and bacterial geneticist, he became more interested in the mitochondrial genome as he completed his PhD in genetic, molecular and cell biology at USC. In 2012, he joined Cohen’s group and began searching for new, small genes in the mitochondrial DNA that expanded the observations made in the Cohen lab. Lee was particularly excited about this concept as he was investigating new genes in bacterial genomes during his undergraduate training.

“At the time, mitochondria were still largely thought about as ‘just making energy,’ but it didn’t really make sense that that was the only thing that mitochondria would have evolved to have become,” Lee says. “I knew there was something more to it. And then I found Hassy’s research, and it just clicked. So, I joined his lab, and we set off to find some new genes.”

One of the genes they discovered coded for a protein called MOTS-c. Found during a screening for peptide activity in response to metabolic changes, the microprotein was first described in 2015 for its role as an “exercise mimetic,” restoring insulin sensitivity and counteracting diet-induced and age-dependent insulin resistance. Subsequent studies of MOTS-c led by Cohen, Lee and colleagues have greatly expanded the microprotein’s job description, uncovering its role as both sender and receiver in intracellular communication during cellular stress and its protective effect against the muscle loss that often accompanies obesity and aging, as well as highlighting how the hormone is expressed in the brain to help regulate metabolism.

In 2021, Research Assistant Professor of Gerontology Hiroshi Kumagai discovered a naturally occurring mutation found in 8% of Japanese individuals that predis-

Right: Dean and Distinguished Professor Pinchas Cohen with Research Associate Professor Kelvin Yen, a member of the Cohen lab since 2011.

Page 24: Cohen with Research Assistant Professor and Cohen lab member Hiroshi Kumagai.

poses them to Type 2 diabetes. Kumagai also recently discovered a key mechanism for the action of MOTS-c by unraveling the molecule CK2, with which MOTS-c interacts in muscle.

USC Leonard Davis School research has also shed light on how MOTS-c plays a role in immune system regulation. In mice that had been genetically engineered to develop autoimmune diabetes, a model of Type 1 diabetes in humans, treatment with injections of MOTS-c protected pancreatic cells from being attacked by immune cells and prevented the onset of the disease, per a 2021 study. And new research from Lee’s lab posits that MOTS-c is the first mitochondria-encoded peptide found to be a host-defense peptide, a protein that directly combats bacteria and regulates immune function.

“This shines a bit more of an evolutionary light on what the mitochondria, from its humble bacterial origin, may have had to do during evolution to work out a symbiotic relationship with a bigger cell and protect itself,” Lee says.

Research Associate Professor of Gerontology Kelvin Yen has long been interested in aging, conducting research on caloric restriction and longevity in mice as an undergraduate at the University of California, Berkeley, and studying the role of insulin and IGF signaling in extending the lifespan of worms as a PhD student at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. In 2010, as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Massachusetts, Yen attended a talk given by Cohen on novel mitochondrial peptides and their role in aging and was immediately intrigued.

“It was super cool and very exciting,” Yen recalls. “I’d never heard of these microproteins before in my life, much less a mitochondria-specific microprotein.” Yen reached out to Cohen following the talk to ask about postdoctoral opportunities; he relocated to Los Angeles and joined the Cohen lab in 2011.

Since then, interest in mitochondrial microproteins has expanded rapidly, not only as USC Leonard Davis researchers identified more proteins but also as mass spectrometry technology improved, enabling more thorough confirmation of the new peptides, Yen explains. And as the body of research has grown, it has further highlighted the connections among mitochondrial biology, aging and age-related diseases.

In a 2016 study, the Cohen group uncovered the genes for six new mitochondrial microproteins, which were dubbed small humanin-like peptides (SHLP, pronounced “schlep”) 1 through 6, and described their possible protective roles versus age-related diseases, including cancer. Of the six, SHLP 2 has been particularly interesting, with the initial study suggesting that it has insulin-sensitizing, anti-diabetic effects.

Subsequent research published in 2024 showed how a variant of the SHLP 2 gene with a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, or “snip”) — a difference in just one “letter” of the protein’s genetic code — increased both its expression and stability and cut the risk of Parkinson’s disease by 50%. The paper, first-authored by Adjunct Research Professor of Gerontology Su-Jeong Kim, noted that the variant was found in 1% of people of European descent.

outside the nucleus of the cell, Cohen says. “With every other gene in the body, there are two copies; every person is an admixture of their two parents,” he says. “But mitochondrial DNA only comes from our mother; we only get one copy, and there is no admixture. This allows us to use mitochondrial DNA to trace our maternal ancestry.”

In addition, while mitochondrial DNA is passed directly from mother to child, it also undergoes evolution at 10 times the rate of nuclear DNA. As a result, “there’s a lot of diversity within the mitochondrial DNA that’s directly linked to maternal ethnicity,” Cohen explains.

CROSS-DISCIPLINARY STRENGTH

Chris Shinn

Similarly, the mitochondrial microprotein MENTSH, recently characterized by Yen, appears to have a SNP variant associated with an increased risk of diabetes. The variant is more commonly found in people of Native American descent, Yen says.

Mitochondrial genetics offers unique insight into aging across various populations due to its location

As USC Leonard Davis researchers have characterized more microproteins, they have also been able to leverage the school’s leadership in biodemography, the incorporation of biological data into large population studies. With the genetic information that’s included in studies such as the Health and Retirement Study in the U.S., scientists can get a clearer picture of how mitochondrial DNA relates to health in humans, says USC University Professor and AARP Chair in Gerontology Eileen Crimmins, a pioneer in biodemography.

“Because we have built these large data sets with representative samples of individuals from different backgrounds, we can look up various genetic markers and we can see how they relate to health outcomes in real populations, with all the other competing things that affect their health,” Crimmins says. She and colleague Em Arpawong, research associate professor of gerontology and director of the Gerontology Bioinformatics Core, have invoked multiple data sources and data types, from genetic code to gene expression levels, to collaborate in unraveling how the mitochondrial genome works together with the nuclear genome to affect aging-related processes. They are co-authors on many USC Leonard Davis mitochondrial microprotein studies, designing analyses that take results from the lab bench and put them into real-life context. Brendan Miller, a 2022 USC PhD in neuroscience graduate, says the interdisciplinary nature of the Leonard Davis School was the “perfect environment” for his work. His fascination with mitochondria having their own genome and his interest in Alzheimer’s led him to the school and Cohen’s lab, and having Crimmins as a co-mentor helped him obtain his skills in statistical methods, population genomics and big-data analyses.

“As a result, we’ve been able to go into these large population databases and find different mitochondrial genes and variants of these genes and immediately bring them down into an experiment that we can test,” Miller says. “That was the biggest standout of USC: having multiple experienced investigators from different backgrounds working on the same question.”

Miller, now a postdoctoral scientist at the Salk Institute, was first author of a 2022 Cohen lab study that identified the mitochondrial peptide SHMOOSE. He used the techniques he learned at USC to identify a mutated version of the protein that increased Alzheimer’s disease risk and brain atrophy. Nearly a quarter of persons of European descent appear to have the mutation, which is associated with a 30% increase in Alzheimer’s risk.

“Ultimately, the goal for SHMOOSE would be to find ways to increase its sensitivity or stability, and pinpoint the exact mechanism that it is involved in,” Miller says, explaining that the peptide’s significant association with Alzheimer’s risk could make it an important drug candidate.

Microproteins in general are exciting potential treatments for age-related disease by nature of their size, he adds.

“Peptides offer a significant advantage in drug development because they’re specific as protein binders,” Miller explains. “There’s often many off-target effects from using larger drug templates. But for peptides, they are smaller and tend to be more specific.”

Since Cohen arrived at the USC Leonard Davis School in 2012, he and his team have discovered and published research on a dozen mitochondrial microproteins, with many more in the pipeline, he says. The tools and techniques he and colleagues have developed continue to advance the field and propel discoveries toward translation.

“We know that these peptides have important roles in Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, obesity, diabetes, heart disease and probably multiple other issues related to health and aging. And we’ve created a pathway for discovery, characterization, IP protection, preclinical development and potential commercialization,” Cohen says.

He notes that an analog of MOTS-c has reached human clinical trials in a company he co-founded, with a Phase 1 study suggesting that MOTS-c treatment indeed has beneficial effects similar to what was seen in animal data. “It is overall a very exciting field with a lot of potential,” he says. “Naturally, it needs substantial investment to move to the next step, but the scientific foundation and rationale are only getting stronger and more compelling.”

Another part of growing the school’s strength in mitochondrial research has been recruiting and educating researchers who are excited about mitochondria and their roles in aging. Ana Silverstein and Melanie Flores, 2024 PhD in molecular biology graduates and postdoctoral researchers in the Cohen lab, both say they didn’t know much about mitochondria when starting their PhD program but broadly knew they wanted to study the immune system and cancer, respectively. Both note that learning about Cohen’s research during a presentation for molecular biology PhD students immediately sparked their interest.

“I saw immense overlap in my research interests in immunity and inflammation, and exploring questions related to mitochondrial function and the field of aging seemed like this exciting and nebulous expedition that I became eager to be a part of,” Silverstein says. “I jumped into longevity research and never looked back.”

Both researchers are already contributing to the rapidly growing body of mitochondrial microprotein

research. Silverstein is working to characterize a peptide that’s a potential regulator of obesity and inflammation, while Flores is investigating a peptide that appears to be involved in regulating tumor growth and survival and could have potential implications for cancer therapeutics.

After more than two decades, the initial skepticism surrounding the discovery of mitochondrial microproteins has morphed into infectious excitement about this uncharted territory in biology — and the USC Leonard Davis School is blazing the trail.

“We’ve established multiple investigators within the school who are part of this process working on various different microproteins, all of which are important and relevant in aging, and have created the infrastructure to continue to use these tools to identify additional high-value mitochondrial microproteins that can be translated into potential interventions in diseases of aging,” Cohen says. “A lot of the people that I’ve trained have chosen this to be their field of study. And we’ve created a real force here, with many collaborations within USC and other collaborators in Los Angeles, around the country and around the world.”

The tiny peptides produced from the mitochondrial genome appear to have big impacts on obesity, diabetes, frailty, Alzheimer’s and more, according to research from the Cohen lab. Additional recently discovered peptides also show promise against cancer, heart disease and eye disease.

Healthy choices support mitochondrial function

Increase in disease risk

Decrease in disease risk

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH, or fatty liver)

- Insulin resistance and diabetes

- Sarcopenia (muscle loss) and frailty

BY CONSTANCE SOMMER

The USC EatWell subcommittee, co-led by USC Leonard Davis professor and dietitian

Cary Kreutzer, helps USC students, staff and faculty eat better with workshops, recipes and nutritious on-campus meal choices.

Cary Kreutzer wants to help USC faculty and staff eat healthier.

“A healthy employee is a great mentor, a great teacher,” says Kreutzer, instructional professor of clinical gerontology at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology and a registered dietitian.

Kreutzer is turning her convictions into action as the co-leader of USC’s EatWell subcommittee. Composed of faculty and staff, the committee is dedicated to improving the health of campus employees with a varied offering of healthy on-campus menu choices, short cooking videos, monthly lunchtime Zoom sessions on healthy eating topics and, soon, a cookbook.

Faculty and staff “play an important leadership role in keeping students healthy and happy,” Kreutzer says. So, the committee is asking, “How can we help people who want to learn more about eating well, and how can we make this information easily available to them?”

EatWell is part of USC Healthy Campus, a crosscollaboration of USC faculty and staff working toward healthy culture change at USC. Healthy Campus partners across academic and administrative units to develop, implement and, ultimately, institutionalize practices, policies, systems and environments essential for the creation of a health-promoting campus.

The EatWell subcommittee, led by Kreutzer and USC Hospitality registered dietitian Lindsey Pine, consists of faculty, staff and nutrition students who work together to create and support a health-promoting university. Other Healthy Campus subcommittees focus on mental health, physical activity, social connection and work-life harmony, says Julie Chobdee, associate director of USC’s health and well-being program.

Charged with selecting a faculty lead for the committee, Chobdee reached out to Kreutzer. As director of the USC Leonard Davis School’s Master of Science in Nutrition, Healthspan and Longevity program, Kreutzer is uniquely suited to advise on nutrition education and research, vet speakers and provide reliable, accurate information on the topic for the campus community, Chobdee says. “She has the expertise that we need,” Chobdee says. “She’s wonderful to work with — very collaborative, very passionate.”

One of the cornerstones of the EatWell program is “EatWell Bites,” monthly Zoom sessions that Kreutzer and Pine hope are both educational and manageably sized. (They are 30 minutes long, on the first Thursday of the month, from 12:15 to 12:45 p.m.)

The format has proved to be a winner. Up to 400 people RSVP for each webinar, with about 100 showing up for the live session, Chobdee says. “It’s been very popular, very positive responses from our faculty and staff,” she says. “They love the bite-size. They love that it’s quick, simple and interactive.”

Topics have ranged from October 2023’s “Observe, Savor, Eat: Learn to Be a Mindful Eater,” led by Michelle Katz, USC Student Health Center dietitian, to “Optimizing Nutrition on the Go: Smart Eating Strategies for Travel and Summer Adventures,” led in July 2024 by Frida Hovik MSNHL ’21, a registered dietitian and clinical research coordinator in the Department of Neurology at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

Kreutzer prefers to call the webinars workshops rather than lectures because “we have a lot of interaction. … We really want to engage participants,” she says. “As adult learners, it’s about getting your questions answered.”

People have so many questions about food in part because there are so many choices to make today, Kreutzer

“I

UNDERSTAND THAT BEHAVIOR IS HARD TO CHANGE. YOU JUST START SOMEWHERE WITH MAKING BETTER CHOICES AND BALANCING YOUR INTAKE OF COMFORT FOODS ALONG WITH NUTRIENT-DENSE WHOLE FOODS.”

— Instructional Professor Cary Kreutzer

says. “Even nutrition experts, we live in this environment [where] we have easy access to ultraprocessed foods that are quick, that are easy, that don’t require refrigeration, that don’t require preparation,” she says. These foods can also be cheaper than preparing meals from scratch, she says.

But with a little bit of planning, eating well and nutritiously is both doable and delicious, Kreutzer says. “I’m not saying don’t ever eat out, don’t ever buy ultraprocessed food,” she says. “But make whole foods your go-to first choice.”

Many campus eateries now offer EatWell-branded meals, marked by an EatWell logo, that are designed to be balanced in sodium, added sugar and calories, and do not contain trans fats or partially hydrogenated oils. They include options like the Breakfast Buddha Bowl at Seeds Marketplace, the Roasted Chicken Salad at Café Annenberg and the Pomodoro Pasta at Filone’s.

“Our objective is to give people delicious, nutrientrich meals that just happen to fit within a set of curated nutrition guidelines,” says Pine, who relied on the US Dietary Guidelines, researched what other universities were doing and talked to other dietitians on the EatWell committee as she and the USC Hospitality retail culinary team worked to create the dishes.