10 minute read

Equine Athlete

High anxiety

Several situations can lead your horse to be stressed

By Heather Smith Thomas

Horses are herd animals and do best with friends in sight and forage in front of them most of the time.

STRESS is a part of life—for horses and humans. Adversities challenge our minds and bodies and different individuals deal with it in different ways. Physical and mental stresses in small doses can make us stronger. Stress can be insignificant if temporary and short term. How the body reacts to stress (with production of cortisol and other hormones) can be helpful in the short term, helping the horse (or human) focus on the problem at hand. The horse stressed by fear of a predator can run faster, for instance. If he’s stressed by a winter storm his body goes into survival mode and he can go without feed a bit longer, until the blizzard ends and he can go back to grazing again.

If stress is prolonged, however, the very things that enable the body to endure the shortterm adversity start to become detrimental instead of helpful. Cortisol production (a natural steroid) triggered by stress begins to hinder the immune system. Prolonged stress can lead to illness (opportunistic diseases take advantage of the depressed immunity), ulcers and other bad things.

In nature, stresses for the horse were usually temporary. The herd sensed danger, became alarmed and fled, outrunning the predator, and then relaxed and went back to grazing again. The wind-whipped rain or snow that drove them to shelter behind a hill, out of the wind, lasted for part of a day and then subsided. Only a long-term stress like severe drought or a bad winter and subsequent starvation was truly detrimental.

Our domesticated horses, however, have more to deal with than what Mother Nature throws at them, and stress can often be a negative factor in their lives. Sometimes the effects of stress are obvious (the horse gets “shipping fever” after a long transport, or a group of newly-weaned foals—stressed by the weaning—get sick with influenza), but often the effects of stress are subtle; we may not always recognize them unless they result in poor performance, stereotypic behavior or ulcers. There are many stressors in our horse’s lives, and not all horses react the same way in how they deal with stress.

Weather

Horses adapt to changes of season, growing longer, thicker hair for winter and putting on a layer of insulating fat under the skin. In summer, they’ve shed out and grown shorter hair and the circulatory system adapts—bringing blood closer to the skin surface to help dissipate core body heat and help facilitate sweating. In natural conditions horses can usually handle the stress of cold weather or summer’s heat.

When humans enter the picture, however, we often add to these stresses by how we use and manage our horses. We may haul horses from a warmer southern climate to a colder northern climate and they have trouble making a fast adjustment, not having had a chance to grow a winter hair coat. Horses moved from Florida or Texas to Minnesota or Wyoming may have a tough time that first winter (and be more vulnerable to illness). It may take a year before they fully adapt to the seasons in their home. The same is true for horses going from a colder climate to a warm one; they may suffer heat stress or lose the ability to sweat properly (anhidrosis).

How we use our horses may also increase the effects of weather stress. If we keep horses blanketed in winter, or clip them so we don’t have to dry a long winter coat after exercise and sweating, they may chill more readily. Likewise, if we use them hard in summer, they may suffer heat stress due to fatigue and dehydration.

stressed more than others. The circumstances of shipping may make a difference in the level of stress, and the physiological impact of that stress. Horses that are stressed too much are more likely to become ill. Multiple studies have shown that confining horses to a trailer for long periods of time has detrimental effects on the respiratory system. The longer the trip, the more likely the horse may end up with a variety of problems--infections like shipping fever or pleuritis, or impaction.

Horses generally don’t drink well when traveling. Many of them are too stressed, even though it might not be obvious they are stressed, and won’t relax enough to drink, or might not want to drink strange water at a rest stop, and thus dehydrate during travel. Some won’t eat well during a long trip, because they are stressed.

Several studies have shown that transport in itself is a stressful event for horses. Two indicators of stress are a rise in heart rate and blood cortisol concentrations. The neutrophil-lymphocyte ratios change; there is usually a decrease in lymphocytes when horses are transported. These are the cells necessary for a good immune response.

Carolyn Stull, PhD (University of CaliforniaDavis) and Dr. Anne Rodiek (California State University-Fresno) worked on several research projects involving transport, one of which was to study physiology of horses during 24 hours of transport and the 24 hours of recovery after transport. The results of this study were publicized in 2003. The horses’ physiological responses during travel and during recovery (resting in individual stalls) were documented, to see how quickly they returned to normal.

Body weight, rectal temperature, white blood count, hydration and other factors were measured. The horses lost about 6% of their body weight during transit, due to sweat loss and decreased gut fill (eating less than normal), but they all recovered about half of this weight loss during the 24-hour rest period after transit. Hematocrit and total protein concentrations increased during transit, which is an indication of dehydration, but these measurements returned to normal during the 24-hour recovery period.

Stress levels can also be measured by checking cortisol levels in the blood. This hormone (produced by the adrenal glands in response to triggering mechanisms originating in the hypothalamus, and passed to the adrenal glands via the pituitary) is generally a good indicator of stress. The concentration of cortisol in the 15 study horses increased during loading into the transport van and contin

ued to rise during the 24 hour travel, peaking at the end of the trip. After the horses were unloaded, their cortisol levels dramatically dropped.

Since cortisol hinders the immune system, its influence can be measured by the ratio of two types of white blood cells (neutrophils and lymphocytes) instrumental in fighting disease. This ratio in the study horses increased during transit and did not return to normal by the end of the 24-hour rest period. The fact it takes longer than this to recover from the effects of stress may be one reason why horses are susceptible to illness following long transport.

In newer studies, investigators continued to look at markers of stress such as increased heart rate during transport. Increased heart rate is probably an indicator for stress, but horses are all different. Some of them travel well and some don’t. One study showed that horses can be habituated to travel, and horses accustomed to traveling have lower heart rates than ones that were inexperienced.

Social Stress

Horses are social creatures and herd animals. In the wild they lived and traveled in groups. A finetuned social structure was essential to their daily

Travel can stress some horses more than others. The longer the trip, the more likely the problems.

Above: Mackenzie Weisz

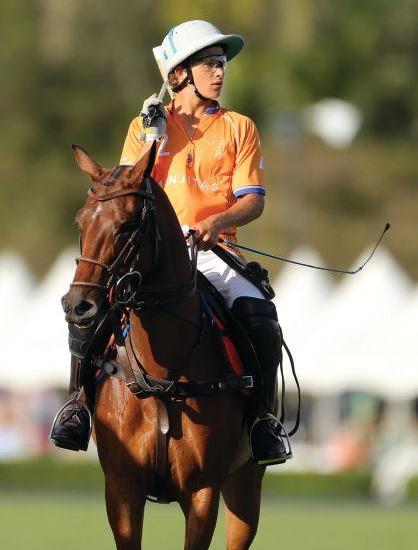

Right: Maco Llambias

NEWS • NOTES • TRENDS • QUOTESNEWS • NOTES • TRENDS • QUOTES

HEAD Subhead THAT’S THE BREAKS Shortened season ends in injury for some

WHILE THE coronavirus cut many players’ seasons short, for a few, it also ended in injury. Mackenzie Weisz was enjoying a terrific season, playing with Las Monjitas in the 22-goal Gauntlet of Polo at International Polo Club Palm Beach. The team won the C.V. Whitney Cup, the first of three events, and was doing well in the Gold Cup. But on March 8, in its game against Dutta Corp, Weisz fell off his horse with a minute left in the second chukker, landing hard on his feet and breaking his ankle. He was replaced by 3-goal Bautista Panelo for the rest of the match.

The team ended up losing that match in surprising fashion but still topped its bracket and advanced to the quarterfinals. Panelo stayed on, helping the team win its quarterfinal match against Patagones. Weisz was on the sidelines, cheering on the team. Las Monjitas was set to play in the semifinal when the season was cut shortly. Hopefully, Mackenzie will be back in the saddle if and when the semifinal is rescheduled. Las Monjitas is the only team eligible to win the 2020 Gauntlet of Polo and the $1 million in prize money.

A few days earlier, former 7-goaler Negro Aguero was helping flag a Gold Cup game between Cessna and Coca Cola when two players came running off the field on either side of him. He was unable to get out of the way and was run over, resulting in a dislocated shoulder and a compound fracture of his leg. He was airlifted to a hospital. He has a long road ahead of him but was reportedly in good spirits and is expected to make a full recovery.

On the West Coast, 4-goal Maco Llambias was playing at Eldorado Polo Club in Indio, California, when he and his horse fell on Feb. 26. Llambias was playing for Antelope in the Fish Creek 8-goal. The team was on a winning streak after winning the Mack and Madelyn Jason final—with Llambias being named MVP—and had made it to the final of both the Beal and Fish Creek 8-goals. In the fifth chukker of the latter, while on a run downfield, someone apparently inadvertently bumped into him, causing his horse to fall. He left the game and was replaced by Marcos Alberdi.

Llambias had broken his wrist, requiring surgery to have a plate and screws put in.

Best wishes to each of these players. On the bright side, if you had to pick a time to have surgery or a lengthy recovery, this is probably the best time. KERRY KERLEY

TEXAS TECH Raffle, auction help raise needed funds

AT THE MOST RECENT Texas Arena League event at Legend’s Horse Ranch’s East Texas Polo Club in Kaufman, Texas, the Texas Tech Polo Club came out to participate and hold fundraising events.

League sponsor Jackrabbit Tack and Consignment donated a NOCSAE certified Charles Owen helmet to be raffled off, and an online silent auction was held for a variety of items donated by Tackeria, Andrea Womble Russo, Wyatt Myr, Elite Motion & Performance, Owen Family, Casablanca Polo, Corey Schlensker, Cargill, Robin Sanchez and more.

Texas Tech Polo Club is an entirely student-based, run and financed program. Club member Amelia Fisher wrote, “[We] love giving people from all backgrounds and equine experience levels the opportunity to learn horsemanship and become experienced in the polo discipline.”

The fundraisers help the club meet its financial goals for the year. It is usually held during one of the last legs of the Texas Arena League, however the global pandemic forced the club to move the auction online.

The club’s facilities were located on property owned by its coach Clyde Waddell, who passed away four years ago. Since then, club members and alumni have been looking for a way to purchase the property. Fortunately, the property was recently purchased by Denny Yates, the father of Texas Tech alumna Ashley Yates Owen, with the intention of keeping the Texas Tech Polo Club going for future generations. The property will be managed by Owen and her husband Ryan Owen, also an alumnus. Both continue to play polo and are actively involved in the Tech Polo Alumni Association.

The Owens are looking for club members, alumni and supporters to help improve the property and make it a top-rated program. Plans include cleaning up the property; improving the guest parking area; enlarging the arena and improving the footing; improving the lighting; improving the buildings; and creating a memory wall.

If you would like to help the program in any way, please contact Ashley at ttpaa2016@gmail.com. Tax deductible donations can be made to the Texas Tech Polo Alumni Association, a 501c (3) non-profit organization.

The Texas Tech team members