10 minute read

Yesteryears

Marion Hollins

An accomplished sportswoman was national champion

By Peter Rizzo

Historians could make a solid case for Marion Hollins to have been one of the best female polo players of her time, though she is better known in annuals of sporting history as a championship golfer and a savvy golf course designer, developer, promotor and real estate investor.

A promotion for a 1998 biography “Champion in a Man’s World: The Biography of Marion Hollins” announced, “David Outerbridge tells the tale of an extraordinary woman who is perhaps the sportswoman of the century. Yet, although she filled the newspapers and magazines of her day, her record of amazing accomplishments is not well known today.”

Was Hollins the best sportswoman, or perhaps even the best horsewoman of the 20th century? From a young age, Marion excelled in a number of sporting endeavors including marksmanship, swimming, race car driving and tennis and tennis court development.

As an equestrian, aside from polo, Hollins was instrumental in introducing steeplechase racing to northern California and helping found the Pacific Coast Steeplechase and Racing Association. She also was heavily involved in racehorses.

Born in 1892, to a wealthy and socially prominent family in East Islip, New York, she grew up on her parent’s 600-acre country estate where she learned to manage four-in-hand horse carriages and ride horses. She also learned to play golf at nearby Westbrook Golf Club. Her father was Harry Bowly “H. B.” Hollins, an American financier, banker, railroad magnate, and partner and best friend of the immortal J.P. Morgan. Unfortunately, her father’s business went bankrupt in 1913 and most of the family estate had to be sold to address longstanding debts.

Outerbridge describes Hollins as being born into a man’s world at a time that women “knew their place.” However, she rejected the notion throughout her tradition-shattering life and was not stopped by obstacles or convention about what she thought needed to be done. She marched in New York City for women’s right to vote in public elections and actively promoted sports for women and children.

At 19, she sailed the Lusitania to spend two months in Europe, an annual sojourn for many years prior to World War I. She was reportedly also the first

women who ever raced in an automobile competition.

Hollins was making her mark as a world-renowned golfer, winning the Women’s Metropolitan, then qualifying for the finals of the 1913 USGA Women’s Amateur. She won the tournament in 1921, in a surprise upset over three-time defending champion Alexa Stirling, an American Canadian who many considered the best woman golfer at the time.

When the Creek Club on Long Island banned women, Hollins helped design the golf course and build 22 tennis courts at the newly-formed Women’s National Golf & Tennis Club in Glen Head. She also hired the club golf pro, Ernest Jones, convincing him to move to the U.S. from Britain.

Hollins was chosen as the captain of the first U.S. Curtis Cup team and went on to win the inaugural event in 1932, defeating teams from Great Britain and Ireland. Hollins was unflappable and known for her fluid swing and her odd habit of humming “The Merry Widow Waltz” to keep her calm and cool while she navigated the course.

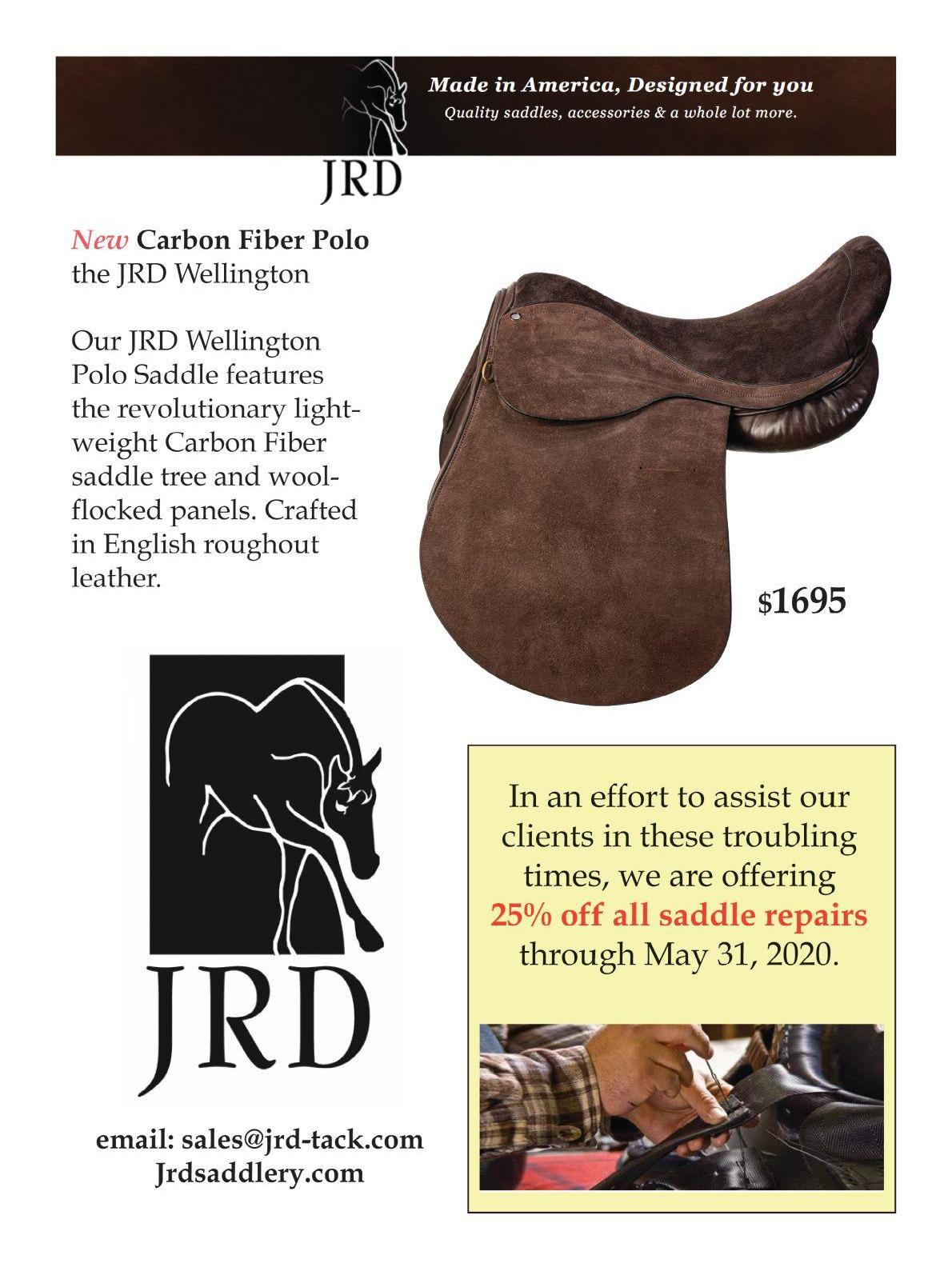

JULIAN P. GRAHAM/LOON HILL STUDIOS

Marion Hollins on horseback, 1924

Marion Hollins, enjoying polo practice in California in 1925.

Marions Hollins, Mrs. Jackson, Mrs. Hart and

Mrs. Spencer Tracy JULIAN P. GRAHAM/LOON HILL STUDIOS

Hollins was also a pioneering force for American women’s polo in the early part of the 20th century. Her family wealth and social connections introduced her to the many, extended New York polo families. Guests at her family home included the likes of polo greats Devereux Milburn and Frank Appleton.

As early as 1913, when she was in her early 20s, Hollins traveled for the season to Aiken, South Carolina, and Palm Beach to hunt and play polo and golf. In the summers, she played on Long Island.

A report in the New York Evening Post read, “Miss Hollins played on the Aiken team and Miss Helen Hitchcock [daughter of Louise E. Hitchcock] played on the Meadow Larks in a polo match yesterday at Piping Rock [Long Island, NY] and Aiken won … Miss Hollins gave a fine exhibition of polo … Miss Hollins scored three goals … Mrs. Thomas Hitchcock gave the cups to the winners.”

The New York Times reported, “A polo game in which women starred and were recipients of much praise was played on Field No. 1 of the Piping Rock Club this afternoon between Aiken and Meadow Larks … Miss Hollins played a remarkable game. Her maneuvering over the field and the perfect handling of her mounts was a notable feature. Both Miss Hollins and Miss Hitchcock exhibited the daring of men. In their defensive tactics they were not only hard riders but skilled horsewomen and players …”

According to reports, future Hall of Famers Thomas Hitchcock and Harry Payne Whitney were happy to loan Hollins their horses, a sign of the respect they had for her horsemanship and poloplaying abilities. When she played polo, she could play all four positions and was known for her strong, forehand stroke.

By the end of 1920, there were reports that Marion was playing polo with members of a British men’s team, which had challenged the United States at Long Island’s Piping Rock polo field.

Outerbridge described her as a party girl who drank, smoked and would not hesitate to climb through a friend’s bedroom window at 6 a.m., champagne bottle in hand.

While she had a few boyfriends, she never married. When asked by one of her nieces why she never married, Marion replied, “Good heavens, what would I do with a husband? I don’t have enough hours in a day as it is.”

In 1924, Hollins wanted to live and work with two of her favorite sports, polo and golf, so she moved to Monterey, California, to work for Samuel F. B. Morse, owner of 7,000 acres on the Monterey Coast that included a lodge, hotel, polo field and two golf courses. Nine-goaler Eric Pedley was known to play at the property’s field. Hollins helped Morris develop the property.

Hollins went on to flip large portions of prime coastal real estate she bought in Big Sur, the mountainous area of the Central Coast between Carmel highlands and San Simeon. She hired wellknown british golf course architect, Alister MacKenzie, to design a number of high-profile golf clubs that included Morse’s Cypress Point Club and the west course of Australia’s Royal Melbourne Golf Club. Later, MacKenzie helped her design the Pasatiempo Golf Club in Santa Cruz.

By 1928, Marion created an investor syndicate with a number of East and West Coast financiers— such as old family friend and poloist, Harry Payne Whitney, and her brother, Kim—founding Kettleman Oil Corporation. Initially, they ran into problems but

once they hit oil, Standard Oil Company bought out the syndicate. Her share of the profit was $2.5 million [a little over $36 million in today’s value].

She put some of her fortune into a trust for her parents but ignored her brother’s and friends’ advice to create a trust for herself. She did, however remember her friends. Years before, Marion, polo player Eric Pedley and horsewoman Louise Dudley made a vow that if any of them made $1 million, they would pay the other two $25,000 each. When Hollins received her money, she kept her end of the bargain, holding a dinner party and putting checks for $25,000 under Dudley’s and Pedley’s plates.

With the rest of the money, Hollins invested in a 570-acre real estate development located in the hills of Santa Cruz County. Hollins rode the site from the back of her horse, making the decision to purchase, and then to fund, her own site development plan that included a swimming pool, tennis courts, bridle trails, a steeplechase course, a beach club on Monterey Bay, high-end residential homesites, and of course, a polo barn and a polo field with a full schedule of weekend matches. She called the property Pasatiempo.

In 1929, Marion invited world golfing sensation Bobby Jones to play an exhibition round on the opening day of her new golf course at Pasatiempo. While they walked her new golf course, they talked about Jones’ aspirations to build his own golf course.

During this time, polo was becoming popular with Hollywood types and many made their way to Pasatiempo, including Spencer Tracy’s wife Louise, who joined Hollins to win the inaugural California Governor’s Cup.

The same year the club opened, the Stock Market crashed, sending the entire world reeling into the Great Depression until the outbreak of WWII. Hollins managed to hang on to the club but it was not easy.

When Jones and a partner found an ideal golf course site in 1931, in Augusta, Georgia, they hired MacKenzie and the same land planners Hollins had used at Pasatiempo.

In 1934, seven clubs, including Pasatiempo, banded together to form the Pacific Coast Women’s Polo Association. Dorothy Wheeler was elected chairman. Wheeler decided to write to the USPA, basically requesting recognition and suggesting women’s associations could work equally well in other parts of the country.

She received a reply rejecting the notion, stating for the record: “… it was not the policy of this Association to make any attempt to identify itself with women’s polo.”

Undeterred, Wheeler helped establish a Women’s Polo Association later that year, publishing a year

Marion Hollins and friends, watching polo in the 1920s.

Louise Tracy and Marion Hollins won the Governors Cup together.

book and its own handicap list. The association also founded a Women’s Open Championship.

Outerbridge wrote, “In 1936, at age 44, overweight and well past her prime, Marion nonetheless earned a six-goal rating [the highest handicap rating was 8]. Her rating on the men’s scale was 2).” She won the Pacific Coast Women’s Championship with Pasatiempo the same year.

There are some questions as to the validity of the claim by several historians that Marion was rated 2- goals in men’s handicaps. For the most part, women were not officially recognized by the USPA, though a few women registered with initials rather than their first names. When the USPA was made aware of it, they officially banned women from registering with the association in 1935.

Outerbridge wrote, “A California newspaper cited a quote from the 1930s: ‘What Babe Ruth is to baseball; Marion Hollins is to polo.’ It is hyperbolic, but at least it is a historical counterbalance to today’s ignorance of Marion Hollins as not only dominate in women’s polo, but unique in her frequent matches with leading male players of the world.”

Marion’s fame, fortune and her life met great personal and financial hardships, perhaps dimming her contributions to sporting history in the U.S..

In 1937, Hollins suffered head injuries in a car accident with a drunk driver. About the same time, she ran out of money and in 1940, she lost Pasatiempo to foreclosure.

In 1942, she managed to qualify and win the Pebble Beach championship, establishing a record of seven wins. Later that year, Hollins played her final golf match, besting the reigning U.S. Women’s Amateur Champion Betty Hicks.

In an article about Hollins, Hicks wrote in 1986, “I was 21 and Marion was 49, and since I believed physical deterioration was complete by 40, I felt certain I would have no trouble disposing handily of this ebullient mass of cashmere and tweed. … and then I was astonished when she gathered together that mountain of wool and swept into a potent, rhythmic swing…”

There is very little record left of Marion’s final two years of life, except for reports about the behavioral changes from the auto accident. She died of cancer, Aug. 28, 1944 in Pacific Grove, California, at the age of 51. Sadly, she was nearly destitute due to diminished health and loss of capacity to address her business affairs.

In 2002, Hollins was inducted posthumously into the Suffolk Sports Hall of Fame on Long Island in the Golf and Historic Recognition Categories. In a nod toward the #MeToo era and the spirit of Marion Hollins, a new golf tournament began in early April 2019 titled, the Augusta National Women’s Amateur Championship. The first two rounds were played at Champions Retreat, in Evans, Georgia, and the final round was played before the Masters—at Augusta National—a fitting turn of events and something Marion would have applauded and if able, might have competed and won. •