11 minute read

Yesteryears

Pure patriotism

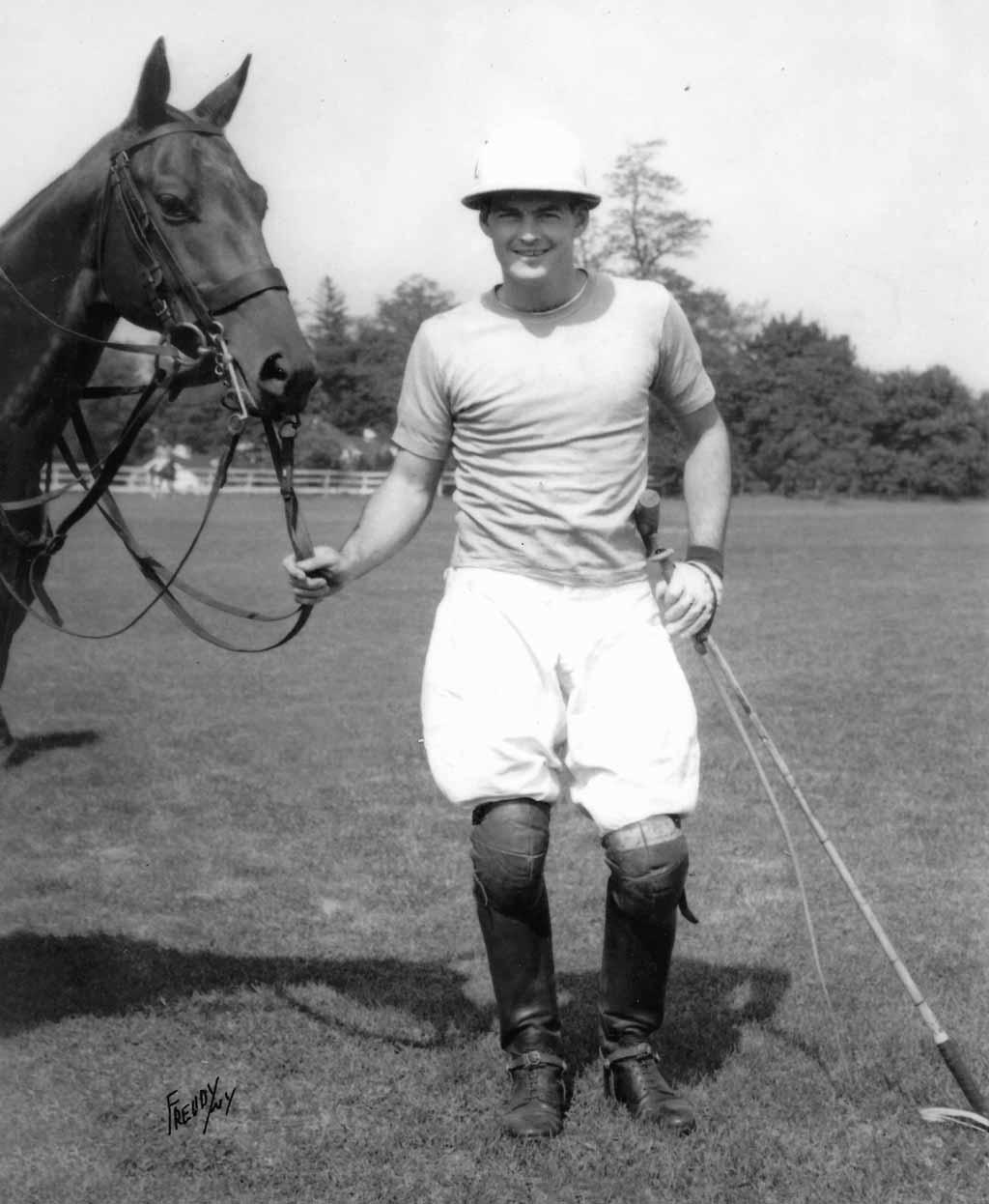

Polo guided early years of general’s illustrious career

By Peter J. Rizzo

Gen. George Scratchley Brown

Polo helped instill the values of leadership, teamwork and daring into a young military brat who carried those qualities with him during an impressive military career, spanning over four decades, as a decorated war hero. Ultimately, his passion for polo did not withstand his strong allegiance to his country, and he went on to become the highest-ranking, most senior officer in the Armed Forces.

George Scratchley Brown was born in Montclair, New Jersey in 1918 to Thoburn Kaye Brown and his wife Frances Katherine Brown (née Scratchley). The military family moved often, however, for many years his father was stationed in West Point, New York, where the first collegiate polo game was played in 1920. At the time, polo was played at almost every post in the Army.

“Requiring intelligence in the horse as well as skill in the rider, polo is a sport particularly suited for the Army,” West Point’s yearbook, the Howitzer, stated.

According to the book “George S. Brown General, U.S. Air Force Destined for Stars” by Edgar F. Puryear Jr., George and his brother learned to ride horses in riding classes offered by the military bases. While their father was stationed at West Point, the brothers would help exercise polo ponies. The pair began playing bike polo and eventually, horse polo. George honed his horsemanship skills and his interest in the sport grew.

Brown’s daughter, Susanah Howland wrote, “... My grandfather TK was a cavalry officer and my dad and his brother spent their summers with their father while he engaged in cavalry exercises. My dad and uncle pretty much grew up around horses and riding. Theirs was not typical “riding lessons” at the post barn.”

Brown decided he wanted to attend the U.S.

Military Academy at West Point right out of high school, but his father convinced him to first attend a year of college. After graduating from high school in Leavenworth, Kansas, Brown enrolled in engineering courses at the University of Missouri. A year later, in 1937, he received a congressional appointment to West Point.

While at West Point, George roomed with John Norton, who went on to become lieutenant general in the U.S. Army. George joined the academy’s polo team, which competed in intercollegiate championships—then played both indoors (for the Townsend Cup trophy) and outdoors (for the Gerry trophy). It was a good fit for the young man who enjoyed the competitive nature of the sport. He was known for his hard-riding but was never dangerous or unfair. He also enjoyed the social aspects of polo with the visiting teams and when the West Point team traveled.

West Point earned an intercollegiate championship in 1938. The Howitzer described the season as a pitched battle between Army and Yale, with Yale finally striking out in the indoor:

“As usual, the first game was with Squadron A of New York and as usual Army won. In this context and the two that followed, Captain Johnson tried various combinations of Christian, Boye, West, Milton and Brown in an effort to find a team that clicked. Against Pegasus, Metropolitan champions, Army met its first defeat. Then an overwhelming victory over Norwich pointed out the team that was to become intercollegiate champions: Christian, West and Boye.”

Brown was listed as a substitute in the 1939 outdoor collegiate championships. West Point suffered an 11-3 drubbing by Yale, led by future Hall of Famer Alan Corey, in preliminary matches of the championships.

In the 1939 indoor season, Army, made up of Brown, Ted deSaussure and captain Ross “Rass Hoss” Milton—all sons of cavalry officers—defeated Princeton, 17-5. Milton was hospitalized a week later with pneumonia, knocking him out for the season. JV player Bobby Strong was called up to replace Milton. Princeton edge them 13-12 in overtime in the next game and they fell to Pennsylvania Military College, 11-9. The trio finally started playing well in its game against Cornell. Winning by a large margin in the early part of the game, the JV team was brought in to finish it off, 19-6. The varsity team displayed the same strength against Yale, racking up five goals before Yale

Brown earned the Distinguished Service Cross after his leadership while bombing oil refineries in Romania. Brown was captain of the West Point team during his senior year.

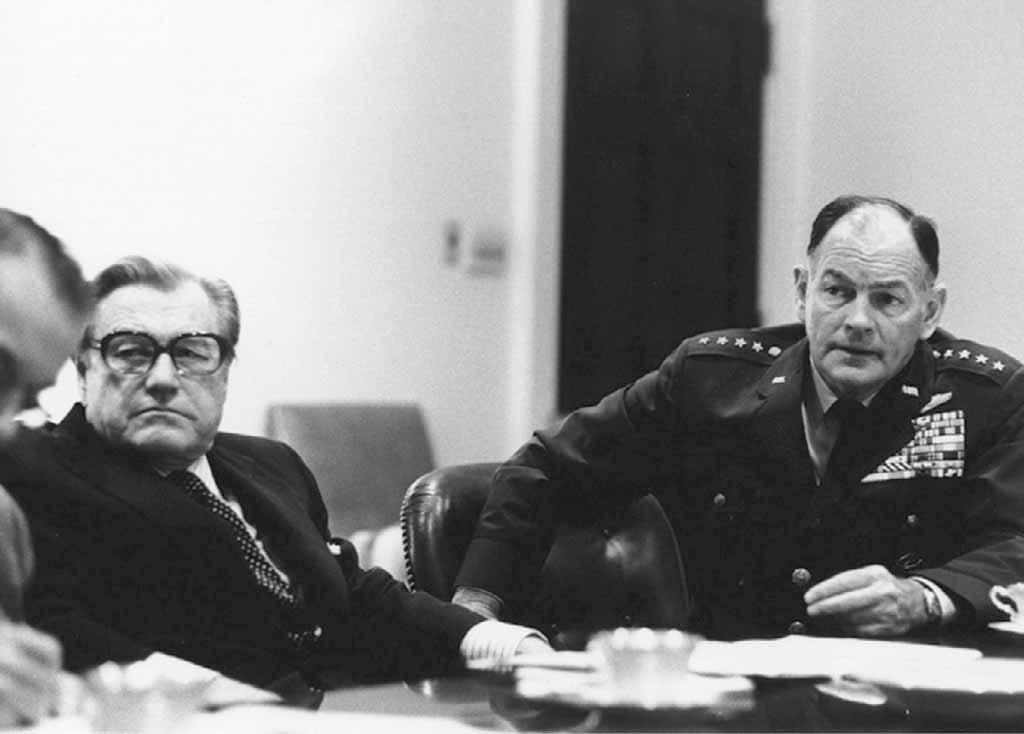

Nelson Rockefeller and Gen. George S.Brown

George Brown and his West Point teammates could get started. Yale trailed most of the game but rallied in the last period to force overtime. Army held on for the 12-11 win with each player scoring four times. Princeton went on to win the championships.

In the 1940 outdoor collegiate championships, the West Point team defeated Harvard, 17-8, in its first match, but lost to perennial front-runners Princeton, 11-9, in the semi-final.

With his natural leadership abilities on the field, it was no surprise when Brown was named team captain in his senior year. The team held its own against veteran teams, including those made up of West Point officers and others from ivy league schools and Squadron A Armory in New York City.

West Point’s yearbook summarized the season: “The ... spring season delivered far too many slippery fields and Army only scheduled two games, Princeton and Harvard. The team of Ross Milton, Bob Strong, George Brown and Ted deSaussure had much fast practice, however, against the Gerry brothers highgoal team and against the West Point officers’ team.

“The intercollegiates found the team commuting between West Point and Boston via airplane. Harvard was drubbed handily in the first round as Ted deSaussure hit ten goals. Princeton proved too tough in the next round and the cadets were eliminated. The indoor season was eminently successful; only one game was lost and that to Princeton. PMC, with its hard-hitting Del Carrol (another future polo hall of famer) was met and defeated in a blaze of deSaussure-Brown glory. Cornell proved easy meat for the seasoned cadets and the advent of the intercollegiates found them the slight favorites over defender Princeton. As the tournament started, the trio took PMC again with Andrus doing some beautiful hitting. The finals brought Princeton who squeezed out a victory and retained the cup. In this tournament as throughout the season, Brown led the team with great distinction and his calm manner served to redeem many situations.”

While at West Point, George met Alice “Skip” Colhoun at a party and later, they began dating, eventually marrying in 1942. Colhoun is the step-sister of polo player Dan Colhoun, a longtime committee member of the USPA’s Armed Forces Committee.

George graduated from the academy in 1941. A description in his senior yearbook stated, “Brownie started out at the very beginning to make a success

of his career as a cadet, and one needs only notice all those chevrons to see that his aims rang true. Being captain of the polo squad as well as regimental adjutant made him undisputed leader of that horsey group known as the station wagon set. The cavalry has never had a more loyal supporter than Brownie. His military record and his fame as a polo player should be a good indication of the fine cavalryman he is sure to make.”

He had aspirations of joining the cavalry, staying close to horses, however it wasn’t to be. Instead, fate took him in a different direction ... up!

“I’m not aware that Dad had the opportunity to play polo after he graduated from West Point, got his wings and went to war. My parents were married soon after his graduation and he went to England for 3 years a mere three months later,” Howland wrote. “When he returned there was no opportunity for horses although the ‘horse gene’ seems to have been passed on to my brother who has been a cowboy in New Mexico for most of his life and my daughter, GSB’s granddaughter, who is a competitive equestrian in the jumper ring.”

After graduation, Brown began flight training in Pine Bluff, Arkansas. He received his pilot wings a year later, in 1942, at Kelly Field in Texas. He was initially assigned to Barksdale Field in Louisiana, where as a member of the 93rd Bombardment Group, flew B-24 Liberators. After flying antisubmarine patrol in Ft. Meyers, Florida, he transferred to England, joining the Eighth Air Force. For the next 20 months, he served as commander of the 329th Bombardment Squadron, group operations officer and group executive officer. As the latter, he participated in low-level bombing raids of oil refineries in Romania from a temporary base in Benghazi, Libya. Several planes, including the group commander’s, were shot down or crashed. Brown, then a major, led the group back to Benghazi. The heroics earned him the Distinguished Service Cross.

In May 1944, Brown was appointed assistant operations officer of the 2nd Air Division, and assumed similar duties a year later with Headquarters Air Training Command at Fort Worth, Texas.

Brown joined Headquarters Air Defense Command in 1946, located at Mitchell Field, New York, as assistant to air chief of staff, operations, and later become assistant deputy for operations.

George’s yearbook stated he was the undisputed leader of that horsey group known as the station wagon set.

Brown said working with troops was similar to working with horses.

During the Korean War in July 1950, he became commander of the 62nd Troop Carrier Group at McChord Air Force Base in Washington, operating between the West Coast and Japan. During 1951 and the early part of 1952, he commanded the 56th Fighter Wing at Selfridge Air Force Base in Michigan; and in May 1952, joined Fifth Air Force Headquarters at Seoul, Korea, as director for operations.

In July 1953, Brown assumed command of the 3525th Pilot Training Wing at Williams Air Force Base in Arizona. He entered the National War College in 1956, and after graduation in 1957, served as executive to the chief of staff of the U.S. Air Force.

Two years later, he was selected as military assistant to the deputy secretary of defense, before becoming military assistant to the secretary of defense. He was promoted to brigadier general the same year.

His career continued at a rapid pace as he repeatedly proved his mettle and ascended the ranks.

In 1963, Brown became commander of the Eastern Transport Air Force at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey and a year later, was selected to organize Joint Task Force II, a Joint Chiefs of Staff unit formed at Sandia Base in New Mexico, to test military weapon systems for all branches of the military.

During his career, George made the comparison between working with horses and troops. In both cases, it is necessary to learn their habits, strengths and weaknesses, and spend time patiently training and conditioning them while building their trust.

From August 1966 to August 1968, he served as the assistant to the chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff, in Washington, D.C., until assuming command of the Seventh Air Force and becoming deputy commander for air operations, U.S. Military Assistance Command. He was responsible for all Air Force combat air strike, air support, and air defense operations in Southeast Asia. In his MACV position, he advised on all matters pertaining to tactical air support and coordinated the Republic of Vietnam and United States air operations.

In September 1970, Brown, now a general, assumed the post of commander, Air Force Systems Command, headquartered at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland.

Brown entered the national limelight after he was appointed chief of staff of the Air Force in 1973 and chairman of the Department of Defense Joint Chiefs of Staff a year later.

As chairman, Brown spoke candidly, often expressing opinions on a number of highly controversial topics. In 1977, he was publicly critical of Congress, leading to calls for his dismissal. President Ford refused, saying he was an outstanding soldier.

After a 40-plus-year career, he retired in June 1978 after being diagnosed with prostate cancer. He died later that year and was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

Upon his death, Secretary of Defense Harold Brown said, “This nation has lost a great patriot and an innovative chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He was a pioneer as an Air Force officer. He was a sincere, straightforward and dedicated man. He was a friend.”

An addition to the Distinguished Service Cross, his military decorations and awards include the Distinguished Service Medal with three oak leaf clusters, Silver Star, Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters, Distinguished Flying Cross with oak leaf cluster, Bronze Star Medal, Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters, Joint Service Commendation Medal and Army Commendation Medal.

“... the medals were a by-product of his core belief in his duty and dedication to his men, service and country,” Howland wrote.

He was inducted into The National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1985.

The USPA honors Brown with the Gen. George S. Brown circuit tournament played at clubs throughout the United States. •