$N

&

» •

03RINNE

Brigham D. Madsen

eeraNNE

is

THEGENTILE CAPITOL OFUTM

Utah State Historical Society SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH

Contents

Preface

1

ix

The Burg on the Bear The Pacific Railroad; Founding of Corinne; Lawlessness of Early Corinne; A Gentile Newspaper; Locating the Junction City; The Montana Trade

Trail Town

31

A City Charter; Municipal Government; Law and Order; Freighting and Stagecoaching; Merchants and Storekeepers; City Improvements

Gentile Capital

65

Descriptions of Corinne; Resident Population; A Governor and Annexation to Idaho; Capital of Utah; Statehood for Deseret; Lobbying for a Canal

4 The Liberal Party

93

Cullom Antipolygamy Bill; The Godbeite Schism; Woman Suffrage in Utah; Founding the Liberal Party; Liberal vs. People's Party; Republicans and Democrats in Utah; Decline of Corinne's Liberal Party

5 Bearding the Prophet

123

Grant Appointees in Utah; Mormon and Gentile Militia; Chief Justice James B. McKean; The Saints of Box Elder County; The Cattle-stealing Case; Brigham's Curse; The Corinne Free Market; Junction Placed at Ogden

vu

6 By Land and by Sea

l55

Paddlewheel Steamboat; The Smelting Works; The Utah Northern Railroad; The Utah, Idaho, and Montana Railroad; Corinne Branch of U N R R ; Portland, Dalles, and Salt Lake Railroad

7 Corinne the Fair

1"^

Utah and Corinne Reporter; Daily Mail and Corinne Record; Episcopal and Methodist Churches; Presbyterian and Catholic Worship; Sunday Laws; A Free Public School

8

Culture on the Bear

223

Holiday Extravaganzas; Baseball Champions; The Opera House; Sports and Fraternal Orders; Chinatown

9

Indian Scare

259

Extension of the Utah Northern; Menace of Franklin; Malad Irrigation Company; Colonization Plans; Northwestern Shoshoni; Indian Scare

10

The Gentiles Flee

295

A Profitable Centennial Year; Utah and Northern Railroad; The Freighting Ends; A Curse Consummated; Conclusion

M a p : Corinne and Vicinity

30

M a p : The Montana Trail

64

Index

Vlll

321

Preface

Until the driving of the Golden Spike on May 10, 1869, the Mormon people had been able to establish their Great Basin empire mostly undisturbed by any influence from the rest of the nation. All at once their isolated silence was broken by the steam whistles that inaugurated an influx of outsiders coming by train from east and west. The construction crews building the railroads were the first to meet the Saints of Utah, and some of the entrepreneurs accompanying the railroad penetration immediately saw the possibility of founding a railroad town that could capture the lucrative wagon trade to the Montana mines, heretofore controlled from Salt Lake City. Corinne, the first large Gentile town in Utah, was the product of that dream. Located about six miles west of Brigham City on the west bank of Bear River where it flows into Great Salt Lake, Corinne became the freight transfer point for goods from the Central Pacific Railroad to Idaho and Montana. The town also became a center of anti-Mormon activity and, until 1878 when the narrow-gauge Utah and Northern Railroad gained control of the Montana traffic, Corinne existed as a burr under the Saints' saddle, annoying and threatening Mormon political and economic control of the territory. The competition with Mormon Utah of the small Gentile town with a population of perhaps fifteen hundred people would have been laughable if its assault on Mormondom had not coincided with national attempts to break Brigham Young's con-

i.\

trol of Utah and to eradicate the practice of polygamy. President Ulysses S. Grant, his federal appointees, and the Congress were determined to destroy the remaining "relic of barbarism" in the nation and, at the same time, to bring the Mormon prophet to heel. Corinne, therefore, became a symbol of resistance to the Mormons and gained much support in Washington, D.C., to further its aims to establish itself as a permanent and progressive city and as a leader in the attack on the Mormon stronghold. The history of Corinne is also interesting and significant for the scene it presented of a Gentile culture of Protestant religions, a free public school, and an atmosphere of fun, frolic, and freedom a frontier end-of-the-trail town offered in contrast to the more orderly and conservative culture of the Utah Saints. Situated on the transcontinental railroad, Corinne was an excellent midpoint stopping place for tourists and visiting easterners making a short visit in Mormondom, and the town benefited from these contacts. Corinne conceived many wondrous projects that failed to materialize, but not through lack of some tremendous effort on the part of her citizens. To Corinnethians their failures seemed attributable, in almost every instance, to the machinations and evil workings of their Mormon neighbors who continually derided and discounted the town's prospects. The rivalry was intense despite the David-Goliath aspects of the relationship. I first became interested in Corinne as the result of doing research on the Montana Trail. As the freight transfer point from railroad cars to wagons, Corinne was the terminus of the trail. Everett L. Cooley, curator of Western Americana, Marriott Library, and professor of history at the University of Utah, encouraged me to undertake the project, and I hope he will find the effort worthwhile. I am also grateful to the staff members of the following libraries and repositories for their assistance and interest: Montana State Historical Society; Idaho State Historical Society; Utah State Historical Society; University of Utah, Marriott Library; Utah State University, Merrill Library; Brigham Young University, Lee Library; Historical Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints; University of California, Bancroft Library; Huntington Library; Library of Congress; and the U.S. National Archives. A grant from the University of Utah Research Committee was very helpful in defraying travel and typing expenses, and I should like to express my appreciation to the

Corinne

members of that committee. I am particularly indebted to LaVon West for her interpretation of my far-from-perfect handwriting and her typing of the manuscript. For any errors of fact or interpretation, I am solely responsible. BDM

Preface

TheT3urg on theT3ear The Pacific Railroad As the Mormon pioneers of 1847 drove their slow-moving ox trains west to the Rocky Mountains, the tired emigrants were already looking forward to the day when a transcontinental railroad would end the enforced isolation of their new Great Basin home and bring an easier passage through the wastelands of the Plains. In a later reference to the original journey, Brigham Young said that he and his followers "never traveled a day without marking the path for the road to this place." 1 Twenty-one years later, as the rails of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific lines converged on Great Salt Lake, Young reiterated his belief that the Pacific road would be advantageous for his people: So far as we are concerned we want the railroad, we are not afraid of its results. . . . And when this road is finished our friends can come and see us, and witness the peace, the order, the freedom from crime, that possesses the cities of Zion, and they will compare them with the sinful depraved cities of our neighbors, and we shall loose [sic] nothing by the comparison. 2 The editor of the Deseret News supplied an economic advantage, explaining that Salt Lake City would act as a great inland seaport to draw trade from the surrounding states that would be established around the mecca of the saline metropolis. Another Mormon journal,

The ceremony of laying the last rail at Promontory, Utah, May 10,1869. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum.

the Millennial Star, predicted that the Union Pacific would aid the Saints in publicizing their doctrines to the world. 3 But concomitant evils raced ahead of the civilization being advanced by the iron horse. At the railroad towns of Bear River City, Echo, Wahsatch, and Uintah, wondering Mormons could observe "unblushing depravity, gross intemperance, gambling hells, and kindred places" in "full swing." In addition, railroad workers and other Gentiles began to have visions of opening the rich mines of Utah now that there was a means of transportation for ores to the smelters and markets of the East. Even the well-established Mormon towns of Ogden and Brigham City along the line of the railroad began to feel the crush as laboring men, travelers, and salesmen descended on the too-few hotels and restaurants, asking for accommodations. One correspondent at Brigham City bravely wrote the Deseret News, "Notwithstanding we are surrounded by many indications to suddenly

Corinne

become a railroad town, the spirit of the gospel is nowise restrained in its usual bearings. . . ." 4 To the pragmatic Mormon leadership it seemed that more than courage was needed to stem the Gentile encroachments on the society and economy of Utah. As early as 1864, long before the railroads reached Utah, Brigham Young had counseled Lorenzo Snow, church leader at Brigham City, to establish cooperatives as a means of making the Saints self-sustaining and, at the same time, to encourage outside merchants to leave the territory. In a sermon in the Salt Lake Tabernacle in April 1866 the prophet reminisced with his followers that he had predicted the destruction of Zion unless some kind of control were exercised over the Gentile storekeepers who were beginning to crowd into Utah. 5 And the program the shrewd leader had fashioned to control the trade and commerce of Mormondom was based squarely on the cooperative scheme tried by Lorenzo Snow. It included a plan (1) to contract to build the railroads through Utah to keep out as many of the hell-on-wheels construction camps as possible, (2) to establish a churchwide wholesale establishment under the name of Zions Cooperative Mercantile Institution that would move all imports, (3) to organize cooperative retail outlets in each local church ward to eliminate non-Mormon stores, (4) to support only local producers and manufacturers, and (5) to boycott all Gentile merchants and bankers.1' Brigham Young had earlier sermonized about the chief motive for the prohibition of trade with non-Mormon firms. Our outside friends say they want to civilize us here. What do they mean by civilization? Why, they mean by that, to establish gambling holes — they are called gambling hells — grog shops and houses of ill fame on every corner of every block in the city; also swearing, drinking, shooting and debauching each other. Then they would send their missionaries here with faces as long as jackasses' ears, who would go crying and groaning through the streets, "Oh, what a poor, miserable, sinful world!" That is what is meant by civilization. That is what priests and deacons want to introduce here; tradesmen want it, lawyers and doctors want it, and all hell wants it. But the Saints do not want it, and we will not have it. (Congregation said, Amen!). 7 The near approach of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific roads in late 1868 and early 1869, therefore, brought a torrent of appeals from Mormon leaders to their people to support the new

The Burg on the Bear

3

cooperative movement. Brigham Young led off with the admonition that despite the expected complaints from outside merchants, they would be left to take care of themselves, while the church would attempt to control its own storekeepers for the benefit of faithful members and would excommunicate all dissidents who continued to trade with Gentiles.8 William Clayton, newly appointed secretary and cashier of the Salt Lake City branch of the ZCMI, emphasized the move to dispossess Mormon storekeepers of their business by writing that the cooperative had not only bought out Jewish merchants such as N. S. Ransohoff and received assurances that the former Mormon Walker brothers were anxious to sell but had also purchased the assets of such Mormon traders as A. C. Pyper, Eldredge and Clawson, and William Jennings. Clayton concluded, "I am in hopes the spring will see a pretty general clearing out." 9 And finally, Young's counselor George Q. Cannon bluntly warned the Saints to stop trading with the Gentiles or be cut off from the church. He continued that he would prefer to excommunicate the disloyal members now than be forced to do so after the church had been driven to the mountains and dispossessed of its property.10 While Mormon Utah prepared to freeze out all outsiders, newspaper reporters representing the eastern and California press ridiculed the fear of violence and sin that railroad civilization was introducing into the Great Basin kingdom. John Hanson Beadle of the Cincinnati Commercial thought that if Salt Lake City, which had had a stable government for twenty years, feared the arrival of a few roughs, its officers of the law confessed a weakness they should carefully hide. Even the Salt Lake papers recognized that the intrusion of lawlessness would be of short duration and that the waves of affliction introduced by the misnamed Gentile "civilization" would soon disappear. 11 The New York Herald, along with most national news journals, expected that the new Pacific railroad would solve the Mormon problem and the issue of polygamy by introducing not only border ruffians to Utah but also by opening to the gaze of all the world the hidden sores that supposedly scarred the religious and political body of Mormondom. The New York Tribune was sure that the railroad would transform Brigham Young's peculiar society.12 As for the attempt to force Gentile merchants out of Utah, both New York newspapers were of the opinion that Young's revelation

Corinne

establishing stores under "The All-Seeing Eye" or, as they called it, the "bulls-eye cooperative," would be counterproductive because the Mormon people would not obey the dictum. Also, said the Sacramento Union, with women "everywhere clamoring for more rights," they would not "be put off much longer with the fourth, tenth or sixtieth of a man for a husband." To sustain such foolish and insidious customs as cooperatives and polygamy, wrote the Herald, might require Brigham Young to move all his people to the Sandwich Islands, even if this were only a Gentile joke at present.13

Founding of Corinne With such speculations by the eastern press about the impact the Pacific road would have, and while the Mormon people resolutely prepared to stand off the influx of Gentiles, some far-seeing men began to wonder about the possible founding of a "Great Central City" that would control trade to vast areas of the Intermountain West. J. H. Beadle, in a surprisingly accurate forecast, wrote to his Ohio newspaper on October 17, 1868: Somewhere, then, between the mouth of Weber Canon and the northern end of the lake, at the most convenient spot for staging and freighting to Montana, Idaho, Oregon and Washington, is to be a city of permanent importance, and numerous speculators are watching the point with interest. But the location is still in doubt. . . . Going north, the valley of the Salt Lake seems to narrow gradually, and imperceptibly becomes the valley of Bear River, . . . and at no very distant day Salt Lake City will have a rapidly-growing rival here. It will be a Gentile city, and will make the first great trial between Mormon institutions and outsiders. . . . It will have its period of violence, disruption and crime, . . . before it becomes a permanent, well-governed city.14 By early spring of 1869 Wahsatch and Echo had already "gone up the spout" and the new sites of Promontory City, Blue Creek, and Bear River at the head of Great Salt Lake and the rich silver district of White Pine in eastern Nevada were beginning to attract attention. Mormon leaders were convinced that their well-established town of Ogden would become the great trade metropolis, but the non-Mormons insisted that they must locate apart from the Saints where they

The Burg on the Bear

5

could control their own municipality and establish a separate Gentile monopoly.1" To ensure that the Union Pacific would enjoy the advantages and profits of the new center, its agent, J. M. Eddy, laid out a town on Broom's Bench seven miles north of Ogden and christened the new settlement Bonneville after Capt. Benjamin L. E. Bonneville who had traded for furs in the area during the early 1830s. An auction of one hundred lots was announced for March 18, 1869, with the understanding that Bonneville would be the terminus of the Utah Division of the Union Pacific, that it would be the location of roundhouses and machine shops, and that it would also become the "switching off place" for Idaho and Montana. But investors were not convinced that it would become a bona fide railroad town. Sales of lots were meager, and by March 26 Bonneville was "considered among the defuncts" by speculators, although Union Pacific officials continued to boost the prospects for the place.16 As early as February 1869 the Salt Lake Telegraph announced that the "New Bear Riverites" were confident that the city of the future would be located at the spot where the rails crossed Bear River, and in far-off Montana an observer gave the reasons why this was the proper site for the grand railroad emporium: (1) it was the nearest point on the line of the railroad to Montana, (2) it was the nearest point to the fifteen thousand people living in northeastern Utah, (3) it was an excellent place for the junction of the Oregon and Puget Sound branch of the Union Pacific, (4) it was located in Bear River Valley where some four hundred square miles of the prettiest land awaited only an irrigation system to divert water from Bear River for an acreage that was already producing sixty bushels of wheat per acre without irrigation, and (5) Bear River offered the only abundant supply of water between the Wasatch and Humboldt mountains. 17 Speculators seemed to agree, as lots were on sale at Bear River by March 19. Many were hopeful that their fortunes would be made on the banks of the stream.18 Even earlier than March 1869 Box Elder County authorities at nearby Brigham City had recognized a need for some authority in the area of the proposed railroad crossing at Bear River. The county court, in a special session of December 15, 1868, established license fees of one hundred dollars for retailers of "Vinous Spirituous Liquors"

Corinne

located within five miles of the county seat and twenty-five dollars for ordinary dram shops — any "house, booth, or Shantee, Dug out, or tent, or any other place" — situated beyond the five-mile limit. Under this ordinance A. Stubblefield was permitted to sell liquor at Booths Ferry on Bear River beginning December 19, 1868, while the firm of Frost and Cole was granted a license on February 15, 1869, to dispense whiskey on the west side of Bear River near the lower ferry.19 J. H. Beadle visited the spot on January 16, 1869, and reported the Stubblefield saloon "where one could get bread, meat, coffee, and sage brush whiskey, on a pinch"; another saloon under construction by Green and Alexander; a man named Gilmore of Brigham City who had laid two foundations for buildings; and others who were considering the site as a natural location for the proposed town. 20 Two other visits by Beadle on February 6 and 18 revealed a town of fifteen houses and one hundred fifty inhabitants. The citizens held a meeting, called the place Connor City in honor of Gen. Patrick E. Connor, and hoped that the Union Pacific officials would lay out a city at the site. Beadle reported: There is no newsstand, post office or barber shop. The citizens wash in the river and comb their hair by crawling through the sagebrush. A private stage is run from this place to Promontory, passing through Connor. The proprietor calls it a Tryweekly, that is, it goes out one week and tries to get back the next. . . . 21 Although Beadle thought that the squatters on Bear River were "a little fast" inasmuch as all the lands within twenty-five miles of the track had been withdrawn from sale by the Department of the Interior acting under the provisions of the Pacific Railroad Act, he nevertheless maintained his interest in the rapid growth of the town. On March 11 he visited the crossing in company with twelve other interested men: Col. C. A. Reynolds, Maj. F. Meacham, Lieut. A. E. Woodson, Gen. J. A. Williamson, Capt. E. B. Zabriskie, Capt. John O'Neil, M. T. Burgess, S. S. Walker, M. H. Walker, N. S. Ransohoff, N. Boukofsky, and J. M. Worley. This combination of former officers in the Union Army and Gentile merchants from Salt Lake City, all looking for a business opportunity away from the restrictions and competition of the Mormon towns, met on the grassy bank of the river, partook of a cold drink, and then spent the rest of the day drinking

The Burg on the Bear

7

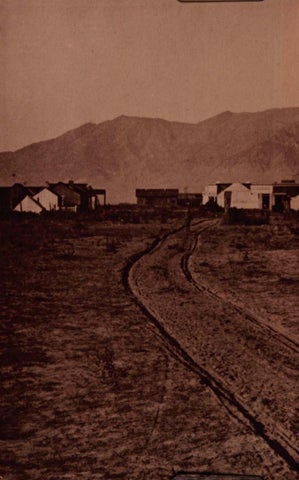

A distant view of Corinne from the northwest. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum. toasts to President Ulysses S. Grant; to the vice-president; to the United States, "May their jurisdiction soon be extended over Utah"; to "the twin relics of barbarism, slavery and polygamy. May the one soon follow the other to perdition"; "And so on, all day and nearly all night, the brunt of the business finally settling on Capt. Zabriskie, who was well able to bear it." After a rapid recovery the next morning most of the party located claims on even sections of land as near the crossing as they could get but, at the same time, were still uncertain if the Union Pacific would establish a town at the spot.22 Having attempted, unsuccessfully, to interest speculators in Bonneville, the railroad company now surveyed the Bear River site and designated Gen. J. A. Williamson as its agent to auction off the lots. Beadle reported, on March 15, 1869: The Mountain Metropolis. The child is born, and her name as you see, is Corinne. Gen. Williamson was given permission to name the town at the crossing of Bear River, North, as the Saints

8

Corinne

call it, and he has christened it after one of his daughters, Corinne. Whatever may be thought of the name, it has escaped the all but inevitable 'city' attachment under which most new towns in the West suffer during their infancy. Corinne is euphonious; new, short enough and long enough, pretty, grand. . . ." 23 A New York Herald reporter explained further that General Williamson's daughter was "a pretty, sprightly young lady of some fourteen summers, named Corinne, after the heroine in Madame de Stael's novel of that name," and the newsman thought the name "a very pretty one, of which the citizens need never feel ashamed." 24 The Salt Lake Telegraph editor later voiced a complaint with which countless other Utah citizens have since agreed. He said that he could not remember how to spell the town's name. It was like trying to spell Cincinnati or Tennessee, and he suggested a couplet to help those of short memory: Two n's, an i, and an e, An r, an o, and a C. As a final dig, he suggested dropping the name altogether and christening the settlement, "Bar Town," "Fulcrum," "Forlorn Hope," or "Last Ditch." 25 By the middle of March, Capt. John O'Neil was busy laying out the town west of the river at the crossing, surveying lots on section 31 north of the track and on the north half of section 6. Under the railroad charter, section 31 was railroad land while the half of section 6 was government land that had to be purchased by the Union Pacific from claimants who had settled it under the Preemption Act of September 4, 1841. The city plat was one mile square, laid off with blocks of twelve lots each, 22 by 132 feet in size, and with an alley through the center of each block. The railroad company received alternate lots in compensation for surveying and platting the site and so became a powerful joint owner of the town. On March 25, forever after celebrated as Pioneer Day by the Corinnethians, a grand auction resulted in the sale of $30,000 worth of lots, ranging in price from $400 to as high as $1,000 each. Within the first week, about $100,000 worth of lots were sold in what investors hoped would soon become the "Queen City of the West." 26

The Burg on the Bear

9

Panoramic view of Corinne and some of the town's earliest structures. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum.

At the time of its founding the lilliputian town of Corinne consisted of sixty or seventy tents and shanties and three or four hundred inhabitants. As one of its first citizens, J. H. Beadle, wrote: It was a gay community. Nineteen saloons paid license for three months. Two dance-houses amused the elegant leisure of the evening hours, and the supply of "sports" was fully equal to the requirements of a railroad town. At one time, the town contained eighty nymphs du pave, popularly known in MountainEnglish as "soiled doves." Being the last railroad town it enjoyed "flush times" during the closing weeks of building the Pacific Railway. The junction of the Union and Central was then at Promontory, twenty-eight miles west, and Corinne was the retiring place for rest and recreation of all employees. Yet it was withal a quiet and rather orderly place. Sunday was generally observed: most of the men went hunting or fishing, and the "girls" had a dance, or got drunk. 27 A more detailed and shop-by-shop description by a reporter of the Salt Lake Telegraph was even more revealing: One house, or tent, of feminine frailty, one bar room and chop house adjoining, one grocery, one saloon with "convenient" apartments, one toggery institution of Jewish origin, one punk roost, one keg saloon, two mercantile adventures, one mayor, marshal and his deputy and city councilors, one vacant lot, one town liquor store, one billiard hall, one bachelor's retreat, one large and inexhaustible stock of general merchandise yet to arrive, one "Gentile boarding house," two private concerns, one "its my

10

Corinne

treat," one washing, ironing and plain sewing erection, one old maid, ah! old as the venerable U.P.R.R. and equally irrepressible, together with one young Americaness, much dilapidated through constant service from Omaha; one faro table, and three card monte; one square meal and round chowder-house, one drug, nostrum, dry-goods, hardware, a spicy peppering of the nymphs du grade, and oyster shop; one corn depot, minus the corn; one lumber yard, fenced with sagebrush; one corral, feed and sale stable, one ton of hay thrown out in the cold; several promiscuous ladies, in eight-by-ten duck domiciles, accommodatingly interspersed for catching stragglers; one or two wholesale and retail liquor establishments, one news depot without the Telegraph; one trio-bagnio, one pale apothecary's shop, where the ills to which Christian flesh is heir are speedily put in trim to call again; one Montana blacksmith shop; . . . one Ping-Chong tea dealer. . . . The correspondent ended his long one-sentence account with the comment that Corinne was "the hope and sheet anchor of civilization for the Mormons, 'the only point on earth where Christianity can be brought into contact with Mormonism and make itself felt.' " The writer implored the government in Washington, D.C., to "patronize such an outgrowth of Christianity." 28 With a tent city founded and expectant merchants eagerly awaiting the trade that would surely come, construction workers finally laid the tracks of the Union Pacific across Bear River and through Corinne on April 7. J. E. Howe, chief engineer of the railroad company, had by this time decided that Corinne rather than Bonneville should be the point of concentration, and the town plat was extended to encompass three square miles of area. Beadle thought that perhaps as much as one-half of the merchant capital and three-fourths of the brains and energy of Salt Lake City would be immediately transferred to the new town. Certainly the high prices for lots, lumber, beef, and other commodities beckoned to the Gentile entrepreneurs of the territory.29

Lawlessness of Early Corinne To bring a semblance of order to the new settlement, the citizens, following good republican practice and without any pretense of asking the Box Elder County authorities at Brigham City for permission, elected Gen. J. A. Williamson as mayor, William Kenney as marshal, M. C. Bowers as deputy marshal, W. Spicer as city attorney, and five

The Burg on the Bear

11

councilors: John O'Neil, J. C. Shepherd, John McLaughlin, J. A. McCabe, and Joseph Crabb. The marshal and his deputy were not without work, because two days after the founding of the town, Beadle reported the incident of a drunken brawler who began firing at random among the tents with the result that an innocent man was shot through the hips.30 The Deseret News thought the place was "fast becoming civilized; several men having been killed there already, the last one was found in the river with four bullet holes through him and his head badly mangled." One visitor merely passing through the town had just alighted from the Wells Fargo stage about a half-mile from Corinne when three ruffians seized him, took him to the city where he was imprisoned in a small room, and threatened him with hanging unless he surrendered his valuables. After losing his belongings he traveled to Brigham City, obtained a warrant, and returned to Corinne where the town marshal refused to serve the warrant unless he was paid $100 in cash for the service, a request the victim could not meet.31 Still another resident of the town played policeman and robbed an individual of $150. When a Jewish merchant lost a stock of goods to a Gentile and had the latter "incarcerated in the cotton calaboose of Ba-ar-town," forty citizens retrieved the thief from the jail and freed him.32 But perhaps a correspondent of the New York Herald, traveling through the West, best expressed the lawlessness of early Corinne: I was compelled to remain there one night, and after inspection of the locality, and noting the number and variety of the faces of the men portion of the community, I deemed it best for the safety of my person and pocket to leave if possible. Looking eastward I happened to espy a neat looking town or village, . . . about eight miles distant, and upon inquiry found that it was Brigham City, a thoroughly Mormon settlement but a place where one could stay with comparative comfort and safety . . . . I chartered a wagon, or rather a pine box on four wheels and left. I drew a long sigh of relief when Corinne was behind me, and I retained but one thought about it, viz., that by reason of the number and evident character of the females inhabiting it its name should be changed to Camille.33 The sedate and quiet Mormons of the county seat at Brigham City were appalled at the eruption of violence just next door and took immediate action to grant the petition of J. A. Williamson and others

12

Corinne

to appoint O. J. Hollister justice of the peace and David R. Short as constable in the newly formed Malad Precinct. Although correspondent Beadle could write the Cincinnati Commercial that the free city of Corinne was exercising all the powers of sovereignty, the founders of the town were happy to appeal to constituted authority at the county seat for help. 34 And the lawlessness of Corinne became an object of concern as the Saints at Brigham City watched their heretofore seldom-used jail fill up with criminals from the town at Bear River. Especially disturbing was the case of James Marley, Morris Kahn, and William Smith, alias "English Bill," charged with robbing Edward Kinney of $130. On June 17 the prisoners broke jail and were shot dead by the prison guard. Unfortunately, during the attempted escape one of the guards, Jonathan T. Packer, was shot in the thigh by a bullet from the revolver of another guard. 35 Surely, Box Elder County had become the abode of a Sodom by a Salten Sea. It was little wonder that the Mormon press very early attached the name "The Burg on the Bear" to the apparently sin-filled city of Gentiles, and, as often happens to a phrase of euphonious alliteration, the title has since found a place in nearly every article written about Corinne. The Salt Lake Telegraph started the attack just two days after the birth of the town by noting that "Already, a good sprinkling of 'frail ones' are on the ground, and in less than a month 'civilization' bids fair to be under full headway." A correspondent, writing from Ogden, pointed out that many of the transient merchants in the city were heading for the new El Dorado on Bear River and he was glad to see them go: They came, they went, and when they left us, They only of themselves bereft us !30 William Clayton was of the opinion that "hell is let loose in earnest," while Brigham Young hoped the rowdy element accompanying the construction of the railroad would soon "pass away," especially at that "sink of pollution," Corinne. 37 A correspondent agreed with the editor of the Salt Lake Telegraph that a thriving town could not "be resolved from the foetid elements rankling at Corinne" but that the place could serve as a sewer to drain off the accumulating filth that had built up during the previous ten years in Utah. 3 * A Deseret News reporter approved the sentiments of an eastern gentleman who said,

The Burg on the Bear

13

"God Almighty have mercy on the people of Ogden, if the carcass of Corinne is to be disemboweled in their streets!" Except for this blast and an occasional reference to Corinne as the "Chicago of the mountains . . . with its few miserable huts and shanties and 'deadfalls,' " the Deseret News as the churchly voice of the Mormon leaders allowed the Salt Lake Telegraph and the later Salt Lake Herald to deride and condemn Corinne. As the News editor patiently explained to his Brigham City correspondent who had reported the town election news for Corinne, "Being a matter so utterly void of significance, we do not wish to attach a seeming importance to it by publishing it in the News." 39

A Gentile Newspaper Such lofty and disdainful aloofness on the part of the Mormon scribe became increasingly difficult to maintain when the Burg on the Bear sprouted its own newspaper by early April 1869. John Hanson Beadle, finding himself temporarily out of funds in October 1868, had volunteered to write a few editorials for the almost defunct Salt Lake Reporter. The owner, S. S. Saul, was so impressed with the new reporter's pungent wit and acrid style that Beadle was immediately hired and, along with two partners, A. Aulbach and John Barrett, soon bought the paper and moved it to the more hospitable Gentile clime of Corinne. 40 Here, Beadle found magnificent support for his unceasing anti-Mormon articles as he and his colleagues struggled to keep the infant Utah Semi-Weekly Reporter alive. By November the paper had burgeoned into a triweekly sheet, but its three owners had, by then, surrendered their interests to the Printers' Publishing Company whose new management announced that delivery would stop to all patrons who failed to notify the company about their subscriptions. Before the change in ownership and throughout the summer and fall of 1869, editor Beadle had full opportunity to establish his point of view and philosophy and, with one brief exception, what came to be the policy of all other Corinne newspapers: attack Mormon theocracy and polygamy at every opportunity; if there were no other news, always fall back on further derision of Mormon practices and theology; and continue a drumfire of boosterism to publicize the grand potential of Corinne as a thriving metropolis and place of settlement

14

Corinne

for other Gentiles. Beadle agreed with his successor that "Ours is a fight of no ordinary consideration. . . . We have the banded influence of Mormonism against us on three sides, and rival towns on the fourth." 41 The extravagant chamber of commerce editorials exceeded even the well-known propensity for small western towns to blow their own horns. The Boise Idaho Statesman, despite its usual support of the Reporter's anti-Mormon tirades, could not refrain from commenting that one would think that according to the columns of the Corinne newspaper "New York, Chicago and San Francisco were situated too far from Corinne ever to amount to much," and although a good paper, the Reporter's "inordinate, uncontrollable weakness is Corinne. It seems to suppose that adjectives and assurances will build a city." 42 Although boosting the prospects of Corinne was a necessary and vital part of /promoting the financial success of the town's business, including that of the Reporter, the barrage of anti-Mormon attacks, asides, and ridicule became almost an obsession with the various editors who tended to look upon themselves as the intellectual and cultural leaders of the town's citizenry. Nothing was too far-fetched that it could not be enlarged upon not only to the delight of the Gentile readers of Utah Territory but also to the consternation and exasperation of easterners far removed from the field of the newspaper battles. For example, the New York Tribune of May 1, 1869, quoted the Utah Reporter's account of a sermon by Brigham Young in which the prophet was supposed to have censured Thomas L. Drake, a vociferous Mormon-hater and associate justice of Utah Territory in 1863: There was old Drake, the D dest old rascal in the country, that said he "loved to d n the Mormons, he'd get up at midnight and walk ten miles over thistles to d n them, and he'd d n any man that wouldn't d n them"; and I say G d d n him, and God will d n him and all such scalawags as they send out here. The Tribune writer attested that the Corinne paper had the most positive proof that the above remarks were reported word for word and concluded that if such things could be said publicly what thoughts and feelings must the Mormon leaders keep hidden in their wicked souls.43 Typical onslaughts against the Utah Saints by the Reporter included disparagement of Mormon leaders, charges of injustices perpe-

The Burg on the Bear

15

trated against defenseless Gentiles, learned analysis of Mormon character or lack of it, and exaggerated accounts of the pernicious effects of Mormon theology on the benighted followers of the "Profit" as Brigham Young was customarily called. When N. P. Woods was appointed deputy U.S. marshal for Utah, editor Beadle attacked him as the nephew of Daniel H. Wells, the supposed evil genius of Mormonism. In illustration of the second category above, the Reporter editor gave an account of a young Gentile gentleman who was attacked by five armed men for "paying attention to some of the Mormon girls" of Salt Lake City. The editor concluded, "the life of a Gentile . . . is not worth a feather in the hands of the Mormon police." In a leading editorial the Reporter explained why the Saints were so downright mean: "The difference between inherent and ordinary meanness is this: The ordinary mean men are usually only mean where their own interests are involved, whereas the inherent mean men [Mormon] are blind to all interests, personal, local or general." As for From their tent office, 1869, the staff of the Reporter initiated one of the liveliest news sheets in Utah journalistic history. William H. Jackson photograph, courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey.

16

Corinne

the questionable doctrines of the Utah church, the editor quoted a New York Post article that emphasized the frightful mortality rate among Mormon children, Young's counselor Heber C. Kimball having reportedly buried forty-eight of his sixty-three children. The Reporter insisted that the Post was misinformed, the editor apparently personally knowing of one polygamous family that had buried one hundred forty-eight children. He was sure that polygamy was the reason for the high death rate. But sometimes it was just easier to dismiss a Utah leader with a succinct "once an ass always an ass," as in the case of T. B. H. Stenhouse.44 The internecine newspaper war between the Utah Reporter and the Mormon journals of Salt Lake City finally erupted into a cause celebre that received national attention. In early autumn Beadle published a severe criticism of polygamist Judge Samuel Smith of Brigham City, charging the jurist with having married two of his cousins and two of the daughters of his own brother to increase his total family complement to six wives. On November 1 Beadle appeared at the Brigham City courthouse, one of twelve Gentiles among twelve hundred Mormons, to answer charges of a debt of $886.82/ 2 supposedly owed to O. H. Elliott for supplies furnished to the Beadle Printing Press. Presiding Judge Samuel Smith dismissed the suit in favor of Beadle. As the editor was leaving the courthouse a young man approached him and said, "You're the man that wrote that lie about my father." He then knocked Beadle down and stomped on him. The assailant, Hyrum Smith, a son of the judge, was tried for the offense and fined $50, although Beadle later maintained it was only $5. Beadle suffered a broken collarbone, in two places, a badly cut temple, an injured right eye, a section of his scalp torn off, and some internal injuries. He was taken to Corinne where he was given medical attention and endured a convalescence of about five weeks before leaving for his home in Rockville, Maryland, having "no desire to try it again" in Mormondom. 45 The eastern press read with avidity the stream of articles pouring forth over the wires and in the editorials of the Reporter. According to the editor, it was Hyrum Smith's intention to murder Beadle; the Mormons of Utah were "sordid barbarians . . . when native-born American citizens are plotted against, shunned, abhorred, driven, persecuted and murdered by a horde of unscrupulous, outrageous, lying,

The Burg on the Bear

17

thieving, murdering fanatic foreigners, it is time for action. . . . "There is no such thing as justice or security for their persons or property here." 4G The Salt Lake newspapers, on the other hand, explained that it was a personal quarrel only and did not represent the views or practices of the general Mormon population, although the Salt Lake Telegraph could not refrain from concluding, "What are we coming to, when in a free country a man cannot slander his neighbors through the press to his heart's content, without getting a bloody nose for it?" 4? The Deseret News was forced to recognize the existence of Corinne again by acknowledging that "Mr. Beadle is the editor of an insignificant sheet . . . which only maintains a circulation of a few scores by continually loading its columns with diatribes against the Mormon Church, . . . remarkable for nothing but scurrilous abuse and sheer lack of truth." While deprecating the attack by young Smith, the News nevertheless warned that "When . . . such parties make their slanderous aspersions personal, they must look for and abide by the consequences." 48 The whole affair was important not only for highlighting the antipathy evident between the two groups but also for exacerbating the Mormon problem in the East and especially in the nation's capital where some lawmakers rejoiced at the new ammunition furnished them to help in the passage of even stricter anti-Mormon legislation.

Locating the Junction City Despite the developing friction between Saint and Gentile in Utah, especially at the focal point of Corinne, with the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the gradual disappearance of the rough construction element, Mormon leaders were relieved by the summer of 1869 to see quiet and peaceful visitors coming by the scores to Salt Lake City and other northern Utah towns.49 In the minds of both Gentile and Mormon businessmen, the immediate question to be resolved was the location of the final junction of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific roads because that spot would become very important as a freight transfer point for goods to Idaho and Montana as well as being the end of the line for both companies where roundhouses and machine shops would provide employment for hundreds of workers with the concomitant of prosperous retail trade.

18

Corinne

East and West shaking hands at Promontory, Utah, May 10,1869. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum.

Within a few days of the driving of the Golden Spike, speculation had narrowed the choice between the Gentile village of Corinne and the Mormon town of Ogden, and now began a long struggle in both Utah and Washington, D.C., to make a final determination that could mean prosperity or decline for Corinne or added growth for the already substantial Ogden. 5 " Brigham Young had anticipated the need for a junction city as early as December 1868 when he determined that the location should be at Ogden. Recognizing that the two railroad companies could be swayed by a proper inducement and that available land at Ogden was already appropriated for other uses, he met with certain property owners and arranged with enough loyal brethren of his church to agree to sell sufficient land at $50 an acre to furnish a site for a railroad station and shops. The railroad officials were astounded, Dr. Thomas C. Durrant of the Union Pacific commenting that there "was not another man on earth could have done the same." The church, of course, assumed the cost of the land and then awaited the expected decision in favor of Ogden. To strengthen the claim of the Utah leaders for Ogden as the site of the junction and to give Salt Lake City a railroad connection to the

The Burg on the Bear

19

Pacific road, Brigham Young proposed to build a branch line from the capital to Ogden, using what finally amounted to $530,000 worth of iron, rolling stock, and construction equipment secured from Mormon contracts in building roadbed for the Union Pacific. The balance of $320,000 in cost was met by calling on the Mormon people who lived along the route to furnish labor and some materials in exchange for railroad tickets and merchandise or, in some instances, to repay the church for having furnished transportation for immigration to the Utah Zion.51 A ground-breaking party was held just seven days after the driving of the Golden Spike, and soon the various Mormon wards had crews at work on the sections of roadbed through their areas. Brigham's son John W. Young, in charge of construction, told the men that he wanted the track laid "without the name of Deity being once taken in vain. And the prospects are that his wish will be gratified." At least that was the pious hope of the Deseret News.52 The last spike on the Utah Central Railroad was driven on January 10, 1870, and as the Saints exulted in their unique achievement an official of the Union Pacific attending the rite declared that the thirty-eight mile railroad was the only line west of the Missouri River built without any subsidy from the government. 53 The new railroad offered a number of advantages to the Utah Saints. It aided immigration to Salt Lake City, gave easy passage to the semiannual conferences of the church, allowed low-cost transportation for Mormon officials and missionaries traveling in line of duty, and, above all, made the new mines in the Salt Lake Valley and Tooele regions economical and profitable to work.54 No wonder the Corinne newspapers tried to belittle the influence of the new line by referring to the U C R R as the "Un Certain R. R." 55 The road certainly strengthened the position of Ogden as the probable meeting point for the two transcontinental roads. Congress had apparently considered the matter settled when it passed in April 1869 the Pacific Railroad bill that decreed "the common terminus of the Union Pacific Railroad and the Central Pacific Railroad shall be at or near Ogden, and the Union Pacific Railroad Company shall build and the Central Pacific Railroad Company shall pay for and own the railroad from the terminus aforesaid to a promontory summit, at which point the rails shall meet. . . ." The words "or

20

Corinne

near Ogden" gave the Union Pacific just enough leverage to continue attempts to capture the Montana trade that now seemed destined to fall to Corinne as the nearest railroad point of departure for the north. By late April rumors had spread that the Central Pacific had completed the purchase of that section of the Union Pacific line from Ogden to Promontory and that as an appendage of the Union Pacific Corinne was definitely "on the fence," as Leland Stanford refused to give assurance of patronage from his company to the new town on Bear River.50 While Mormon newspapers began to refer to Ogden as "Junction City," Corinnethians became desperate. Other speculations had the Union Pacific willing to sell its road west of Ogden, although preferring to keep Corinne as its terminus. Still others in the know were sure that the two roads would finally agree to own jointly the section between the two towns. The Salt Lake Telegraph described a conversation between two gentlemen, one of whom suggested that if Ogden were finally chosen, "Corinne would fold up its tents and not very silently steal away to Ogden." 5T A correspondent writing from Salt Lake City in October thought it a scandal that the two roads were still meeting at Promontory as they haggled over the price the Central Pacific should pay for the road to Ogden. 5S The latter company threatened to build its own line to Ogden to share in the Utah trade. The Union Pacific moved its shops into Ogden, which the Deseret News thought would mean the demise of "Bar-artown"; and one disgusted patron thought that Corinne might be a reasonable compromise to settle the problem and that the Gentiles' real headquarters were at Corinne. 59 The two companies finally settled upon Ogden as the de facto junction of their two roads, and by December 1, 1869, the Central Pacific had dispatched three hundred Chinese workers to improve its new section of the line to Ogden. The Deseret News editor worried over the influx of undesirables from Promontory and Corinne into Ogden but reassured himself that there were no lots available for purchase by these owners of gambling hells and rum holes.00 The Utah Reporter put on a brave face about the ostensible location of the junction at Ogden, reporting that Leland Stanford was inspecting Corinne and would probably offer some help to the Gentile town but more realistically admitting that the location of the junction

The Burg on the Bear

21

was not really important as long as Corinne controlled the Montana trade. 61 The Idaho Statesman was of the opinion that "the Corinnetheans look 'sick.' They fear that railroad connection with Montana will go with the junction to Ogden . . . ," a prophecy that eventually was fulfilled. The Boise paper was also certain that the transportation of goods and passengers to western Idaho would come from Kelton, west of Great Salt Lake on the Central Pacific, another realistic appraisal.02 But the people of Corinne continued to push the prospects of their chosen city at the expense of their Mormon rivals. A typical blurb explained that Corinne handled more business and paid more taxes than did Salt Lake City.03 In solid support of fellow Gentiles, newspapers like the New York Herald also saw comfort in the inevitable decline of the new temporary junction at Ogden, because Corinne was still the depot for Montana and Idaho freight and had better prospects for growth than Ogden. The Herald was certain that although many people were leaving Corinne for Ogden, the lack of available land, the exorbitant rents charged by Mormon landlords, and the insufficient profits available at Ogden would "be conducive to a speedy return to their first love, .onnne.

The Montana Trade The founders of the place had been confident from the first that the natural advantages of the settlement would make it a terminal town that could monopolize the Montana and Idaho trade. It lay at the head of what Capt. Howard Stansbury in 1849 had called "the best natural road I ever saw," from the mouth of Bear River, north over the easy Malad Divide, down Marsh Creek and the Portneuf River to Fort Hall and Snake River Valley, across the Snake at Idaho Falls and then due north again across the Continental Divide at another low elevation at Monida Pass, and finally down Red Rock Creek to the headwaters of the Missouri River."5 The location on the west bank of Bear River not only removed a formidable river crossing but also placed the town at a point where the stream was eighteen feet deep and two hundred feet wide, water enough for a lake port that could draw trade from the mines south of Great Salt Lake. Finally, the location placed the town on the most northerly point of the Pacific

22

Corinne

railroad, four hundred seventy-five miles from Helena, Montana, and twenty days or less time for goods from the East. Realizing these advantages, the Union Pacific had very reluctantly given up ownership of the track from Ogden to Corinne to the Central Pacific which now controlled the transfer of freight to the northern mining camps and towns of Idaho and Montana, the shipment of goods to Boise and western Idaho by way of Kelton, and the trade of northern Utah as well through its terminal at Ogden. Corinne, quite naturally, became Montana-minded, realizing that its very existence and potential for growth were almost solely dependent on its position as the point where freighters transferred goods from the trains to their wagons for the long ox-team trip to the north. 00 Since the opening of the mines in western Montana and eastern Idaho in 1862—63, the two areas had been supplied along two main routes: by wagons on the Montana trail from Salt Lake City and by steamboats up the Missouri River from Saint Louis. Of the approximately 25,000 tons of manufactured goods and other articles shipped into western Montana and eastern Idaho each year to supply the 50,000 residents there by 1869, probably 6,000 tons came from Salt Lake City and the balance from Saint Louis. The river route offered cheaper transportation but an unreliable delivery date because periods of low water would often strand the boats several hundred miles downstream, necessitating the dispatch of wagon trains to pick up the goods for delivery to Fort Benton, the head of navigation. Merchants in Helena, Virginia City, Bannack, Deer Lodge, and the other towns had, therefore, become accustomed to ordering bulk or heavy goods by way of the Missouri but more critical items such as tools, clothing, fresh fruit in season, and other necessities or luxuries via freight wagons from Utah. One of the chief disadvantages of the latter route was the long wagon haul from Omaha or Saint Louis to Salt Lake City even before other freighters could pick up the goods for transshipment north. This meant that orders had to be placed far in advance of delivery to Montana businesses. Then, all at once, the driving of the Golden Spike had eliminated the long trip by wagon and had further shortened the distance to Montana by placing the terminus of the road at Corinne, some seventy miles north of Salt Lake City.07 Wholesale dealers at Omaha and San Francisco, the people at Corinne, of course, and Montana merchants all expected that the Mis-

The Burg on the Bear

23

souri River route would now become obsolete or that, at least, the proportion of goods sent from Corinne would rise dramatically. The everlastingly optimistic promoter at the helm of the Utah Reporter expected that the town would now command the entire trade to the North; and, as far as passenger travel was concerned, the editor was sure that with the temperature at ten degrees below zero at Fort Benton, "People are not going in and out of Montana that way when they can come through Corinne, where everything is warm and lovely as the heart could wish." In support of Corinne's hopes, forty-three Helena merchants dispatched a telegraph to the eastern firm of Graham, Maurice and Co., offering their support for a proposed fast freight line from New York which the company intended to establish by way of the Pacific railroad and Corinne to Montana. 09 These sanguine expectations of both Corinnethians and Montanans were not realized, as lower rates and higher water continued to make steamboat traffic on the Missouri River the most economical and satisfactory means of supplying the northern territory with bulk goods. But the new freight-transfer point on the Central Pacific became so important for the rapid and sure delivery of critical articles that the people of Montana became quite Corinne-minded. The shift to freighting via the Central Pacific was a gradual process, however, the old law of physics that a body in motion tends to remain in motion operating very well in this instance. The uncertainty of the completion of the transcontinental railroad, the lack of a definite location for a freight-transfer point, and the deliberate underbidding in 1869 for freight by the Missouri steamboat lines, all worked to discourage northern merchants from attempting to change their pattern of obtaining supplies or goods for their Idaho and Montana customers.70 As a result, Corinne seemed, to many observers, to be a dying town during the summer of 1869. The editor of the Deseret News was glad and noted that many people were deserting the town which he thought was nothing more than a bilk anyway. Other newspapers in Utah and Montana agreed that Corinne was quiet, flat, and fast disappearing and that its rival, Ogden, was in no better shape.71 In fact, T. B. H. Stenhouse, sent by Brigham Young to establish the Telegraph newspaper at Ogden, wrote in July that there were no prospects for success; the people's pockets were empty; the town was dull; and there was nothing to provide any interest for a paper. 72

24

Corinne

One bright spot in an otherwise gloomy panorama was the flight of those lawless and discordant individuals who had brought Corinne into disgrace in the eyes of its Mormon neighbors. The Deseret News, surprisingly, wrote on July 28, "Those vile blots on the social surface, which made Uintah and Corinne moral pest spots, have been removed, and the element that remains is courteous, peaceable, gentlemanly and business-like." 73 Only one dance hall and gambling hell remained by late June, and the Helena Herald was pleased that "the town is casting aside its cotton overalls, and will soon appear in a more pleasing and goodly raimant." The Montana paper also noted, on September 23, that Corinne was quite brisk in comparison with any other town in the area outside of Helena, which emphasized that Montana merchants were beginning to place orders for goods from the wholesale houses at the Central Pacific location.74 The resulting pick-up in business worried the local newspaper editor, who began to expostulate with his fellow Enthusiastic crowds at the laying of the last rail of the transcontinental railroad. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum.

The Burg on the Bear

25

townsmen to lay in large stocks of goods for the mountain orders and to wake up to their own interests.75 To counteract the gloom exhibited by some Corinnethian businessmen and the impending doom, which throughout the history of the Gentile town seemed always to hover like a black cloud of Mormon locusts on the horizon, the Utah Reporter started very early what came to be an interminable newspaper campaign of puffs and spouting about the absolute inevitability of the supremacy of that metropolis of the mountains — Corinne. 70 By late 1869 the editor was devoting long editorials and special articles in praise of his favorite town, noting that Thomas C. Dunn of Salt Lake City or some other distinguished citizen had decided to become a Corinnethian, reporting that four local stagecoach company men were visiting in town, and taking pride in "our H O M E . . . an American city." 7T After all, Corinne was becoming a town of no ordinary importance, the stepping-stone between the prairies of the Midwest and. the vast resources of the Pacific Slope, the halfway house between Mexico and Canada, a harbor of rest for the weary transcontinental traveler, a point of departure for the northern territories, and a natural outfitting place for miners and explorers. The Idaho Statesman commented, "that lest its modesty shall be its ruin, we advise the Reporter to 'stand in' and blow a little for Corinne." 7S Nevertheless, the year of the Golden Spike had marked the birth of the first important Gentile town in Mormon Utah, had seen it struggle through an infancy of turmoil and trouble, and had finally ended watching and wondering if the fledgling would survive to adulthood. To loyal Corinnethians, at least on the surface, there was no doubt about the potential for growth and greatness. All that was necessary was the development of trade with the eager customers of Idaho and Montana and the establishment of a stable city government to direct and supervise the building and expansion of the new industrial and commercial center of the Rocky Mountains. As a new year approached, the citizens of Corinne turned their attention to the internal problems that must be solved if the bright future that beckoned were to be realized.

26

Corinne

NOTES FOR CHAPTER 1 1 Deseret News, 11 September 1868; see also Robert G. Athearn, "Opening the Gates of Zion: Utah and the Coming of the Union Pacific Railroad," Utah Historical Quarterly 36 ( 1 9 6 8 ) : 291-314. 2 Brigham Young to George Nebeker, 4 November 1868, Brigham Young Letter Books, microfilm, reel 16, 208, Archives Division, Historical Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. 3 Deseret News, 7 August 1867; Millennial Star 30 (1868) : 4 4 0 - 4 2 ; "Journal of Leonard E. Harrington," Utah Historical Quarterly 8 (1940) :46. * Deseret News, 19 December 1868; 10 February, 25 March 1869. 5 Leonard J. Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation among the Mormons (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1976), pp. 112-13; Sermon of Brigham Young, 8 April 1869, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool, 1854-86), 13:36. 6 Leonard J. Arrington, From Quaker to Latter-day Saint: Bishop Edwin D. Woolley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 1976), p. 428. 7 Sermon of Brigham Young, 8 October 1868, Journal of Discourses, 12:287. ÂťIbid., 29 November 1868, 12:312; 7 April 1869, 1 3 : 4 ; George A. Smith to Brigham Young, 1 May 1869, BY Letter Books, reel 17,512. 9 William Clayton to Dear Friend, 23 March 1869; William Clayton to Heber Young, 4 April 1869; William Clayton to F. M. Lyman, 2 May 1869; William Clayton to Karl G. Maeser, 5 July 1868; William Clayton to Bro. Jesse, 19 December 1869; in William Clayton Letter Books, vol. 4, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 10 Sermon of George Q. Cannon, 7 October 1868, Journal of Discourses, 12: 294; see also Ronald W. Walker, " T h e Godbeite Protest in the Making of Modern Utah" (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1970), p. 36; and Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1958), pp. 293-322. 11 John Hanson Beadle Scrapbook, 22 November 1868, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.; Salt Lake Herald, 5 January 1869; Deseret News, 7 July 1869. 12 New York Herald, 12 May 1869; New York Tribune, 19 May 1869; Salt Lake Herald, 24 December 1868. 13 New York Tribune, 19 August 1869; New York Herald, 10 November 1869; Sacramento Union, 10 November 1869. 14 Cincinnati Commercial, 17 October 1868. 1! >Salt Lake Telegraph, 19 December 1868; 8, 10, 24 March 1869. 10 Salt Lake Telegraph, 15, 23, 26 March 1869. 17 Salt Lake Telegraph, 2 February, 5 March 1869; Montana Post, 19 March 1869; Beadle Scrapbook, 21 February 1869. 18 Salt Lake Telegraph, 23, 24, 26 March 1869; Deseret News, 24 March 1869. 19 Box Elder County Records, Book A, 15 December 1868, 148; Book A-B, 1856-86, 207, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City. 20 Corinne Journal, 25 May 1871. 21 Ibid.; Beadle Scrapbook, 18 February 1869. 22 Beadle Scrapbook, 11 March 1869. '" Ibid., 15 March 1869. 24 New York Herald, 29 December 1869. Corinne ou I'ltalie, published in 1807, is considered to be Madame de StaeTs best work of fiction and a strong influence on the romantic novel. 25 Salt Lake Telegraph, 26 April 1869.

The Burg on the Bear

27

2 ° Beadle Scrapbook, 15 March 1869; Salt Lake Telegraph, 27 March 1869; Corinne Journal, 25 March 1871; S. H. Goodwin, Freemasonry in Utah (Salt Lake City: Committee on Masonic Education and Instruction, 1926), p. 7; Bernice G. Anderson, "The Gentile City of Corinne," Utah Historical Quarterly 9 (1941): 141-42. 27 John Hanson Beadle, The Undeveloped West; or, Five Years in the Territories (Philadelphia, 1870), pp. 120-21; John Hanson Beadle, Polygamy; or, The Mysteries and Crimes of Mormonism (Philadelphia, 1904), p. 234. 28 Salt Lake Telegraph, 13 April 1869. 29 Salt Lake Telegraph, 9 April 1869; Deseret News, 14 April 1869; Montana Post, 16 April 1869; Beadle Scrapbook, 27 March 1869. so Salt Lake Telegraph, 13 April 1869; Beadle Scrapbook, 27 March 1869. 31 Deseret News, 7 April, 26 May 1869. 32 Salt Lake Telegraph, 15 June 1869; Deseret News, 9 June 1869. 33 Salt Lake Telegraph, 26 May 1869. 34 Box Elder County Court Records, 18 March 1869, 2 1 1 ; 13 July 1869, 213; 6 September 1869, 213; 6 December 1869, 216, U t a h State Archives; Cincinnati Commercial, 30 September 1869. 35 Box Elder County, First District Court, Book A-B, 1856-76, 15 June 1869, 304, Utah State Archives; Salt Lake Telegraph, 23 June 1869; Deseret News, 23 June 1869; see Jesse H. Jameson, "Corinne: A Study of a Freight Transfer Point in the Montana Trade, 1869 to 1878" (M.A. thesis, University of Utah, 1951), p. 64. Jameson says that the legend of nightly killings during 1869 is just that — a legend. In fact, there was less recorded crime in Corinne. during that summer than in Salt Lake City. 36 Salt Lake Telegraph, 27 March, 1 April 1869. 37 William Clayton to Heber Young, 4 April 1869, WC Letter Books, vol. 4; Brigham Young to A. Carrington, 13 April 1869, BY Letter Books, reel 16, 482. 38 Salt Lake Telegraph, 22, 26 April 1869. 39 Deseret News, 5 May, 18 August, 1 December 1869. 40 Beadle, The Undeveloped West, pp. 115-17. 41 Utah Reporter, 2, 13 November 1869. 42 Idaho Statesman, 25 November, 21 December 1869. 43 New York Tribune, 1 May 1869. 44 Utah Reporter, 23 October; 4, 9, 21 December 1869. 43 Beadle, The Undeveloped West, pp. 183-87; Box Elder County, First District Court, 12 October, 1 November 1869, 9; Utah Reporter, 23 October 1869. 46 Utah Reporter, 4, 6 November 1869. 47 Salt Lake Telegraph, 4, 7 November 1869. 48 Deseret News, 10 November 1869. 49 William Clayton to John Gillibrand, 24 July 1869, WC Letter Books, vol. 4. 50 Montana Post, 14 May 1869. 51 Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, pp. 265, 270-72, 485-86. 52 Deseret News, 14 November 1869. r.3 Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, pp. 272-73. =4 Ibid., pp. 273-75. D5 Utah Reporter, 15 January 1870. ™ Deseret News, 28 April, 5 May 1869; Idaho Statesman, 29 April 1869. 57 Deseret News, 26 May 1869; Salt Lake Telegraph, 27 May, 23 July, 18 August, 14 September 1869. 08 Letter from Salt Lake City, October 1869, Bancroft Scraps, Utah 1 170, Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 59 Ibid.; Deseret News, 2 September, 6 October 1869.

28

Corinne

60 Salt Lake Telegraph, 12, 30 November 1869; Idaho Statesman, 27 November 1869; Deseret News, 1 December 1869. oi Utah Reporter, 30 November; 2, 23 December 1869. 02 Idaho Statesman, 20 November, 4 December 1869. M Utah Reporter, 27 November 1869. 4 MOT ForA; tferaW, 29 December 1869. a:i Salt Lake Telegraph, 5 April 1869; Howard Stansbury, Exploration and Survey of the Valley of the Great Salt Lake . . . (Philadelphia, 1852), p. 93. G6 Jameson, "Corinne: A Study," pp. 6-43. 67 Ibid., pp. 20-47. 88 New Northwest (Montana), 3 December 1869. e9 Utah Reporter, 27 October, 11 November, 28 December 1869. 70 Jameson, "Corinne: A Study," p. 85. ™ Deseret News, 12 May 1869; Salt Lake Telegraph, 14, 22 May; 20 J u n e ; 20 July 1869; Helena Herald, 13 May 1869. 72 T. B. H. Stenhouse to Brigham Young, 20 July 1869, BY Letter Books, reel 62. 73 Deseret News, 28 July 1869. '^Salt Lake Telegraph, 20 June 1869; Helena Herald, 23 September 1869. 75 Utah Reporter, 6 November, 14 December 1869. 70 Idaho Statesman, 25 November 1869. 77 Utah Reporter, 6, 27 November; 23 December 1869. 78 Idaho Statesman, 25 November 1869.

The Burg on the Bear

29

Clorinne and Vicinity

Tooele O Stockton O O Ophir

30

Corinne

'xHMr*-n^S'fl

Trail Town

A City Charter Although a city government of the popular style had served Corinne fairly well during its first year of existence, the absence of an official charter and a legally constituted election process had led to abuses and charges of irresponsible administration. The whole matter came to a head in February 1870 when leading citizens representing the Chamber of Commerce Association called on Constable Patterson to request his resignation which "would be cheerfully accepted and no questions asked" because his supervision of the office had proved unsatisfactory. The same delegation then asked Justice of the Peace S. G. Sewell to vacate his office for, as the Utah Reporter explained, the two officials had been chiefly responsible for the bad management of city affairs that was standing in the way of "the brilliant future awaiting us. . . . Corinne is no longer a harum-scarum western town. . . . " Sewell answered the charges by presenting an itemized statement of his handling of the money provided for building a jail and employing special police, an accounting the Reporter called inaccurate, hinting that more serious derelictions would shortly be published. As for Patterson, before he could be removed, he became involved in a public fight with a Mr. Wright, to the disgrace of himself and his fellow townsmen.'

31

The dismayed citizens circulated a petition on February 14, 1870, asking the territorial legislature, then in session, to grant the city a charter. According to a member of the petitioning committee, Orson Hyde Elliott, writing his reminiscences later, the legislature rejected the request until he secretly traveled to Salt Lake City, made a personal appeal, and within one hour saw the passage of a bill incorporating Corinne. But personal memories tend to build the esteem of the author as he looks back in time at his own tremendous exploits. The Utah Reporter merely noted that Elliott had been appointed by the citizens to present the petition and had gone to Salt Lake for that purpose.2 The charter, approved February 18, 1870, granted all of section 36 and about half of section 31 of township 10, and all of section 1 and about three-fourths of section 6 of township 9, of ranges three and two west, to the new Corinne City.3 This was a larger area than the original city plat recorded by J. E. House in Douglas County, Nebraska, on May 24, 1869, but even that vision had encompassed sufficient land for a magnificent metropolis. The Central Pacific Railroad divided the town into roughly northern and southern areas, although the business section lay almost completely south of the tracks while the northern section came to be the staging grounds for freighters readying their trains for the trip to Montana. From North Front Street just above the railroad line, the town was planned for ten blocks beginning with Washington Street and extending to Nevada Street. South of the tracks, Montana Street became the main thoroughfare with adjoining Colorado Street offering sites for overflow business. The city extended thirteen blocks to the south, ending with Canal Street. All the streets led from the west to the banks of Bear River. It must have been somewhat galling to the Corinnethians to note that their charter was signed by George A. Smith, president of the territorial council but also a Mormon church counselor to Brigham Young, and by Orson Pratt, speaker of the Utah Territorial House of Representatives and the leading philosopher and expounder of Mormonism.4 The act of incorporation, in eighteen sections, granted powers somewhat typical for most western towns. Provision was made for a mayor and ten councilors, five of whom were to be elected for one-year terms and five for two-year terms, with annual elections for five councilors thereafter. Elections were established for on or before the first Monday in April of each year, with the first election to include as

32

Corinne

voters all those who had been residents of the town for at least six months prior to election day. There were to be two justices of the peace, and a recorder, treasurer, assessor and collector, marshal and supervisor of streets, or as many of the latter officials as the citizens should desire. The city council had the necessary powers to levy and collect taxes upon all taxable property, real and personal, within the city limits. Appeals from city courts were to be heard by the probate court of Box Elder County. 5 And, finally, neither the mayor, members of the council, nor the justices of the peace were to receive salaries, with the justices being allowed to collect only such fees as the mayor and council prescribed. The Utah Reporter was especially pleased that there were to be police justices who could punish such offenses as disturbing the peace and other breaches of good order with appropriate fines that would also provide a considerable revenue for public improvements.0 Proceeding under authority of the new charter, a municipal election was held on March 3, 1870, during which several political parties appeared under such names as up towners, down towners, north siders, Malshites, and Munrorers, the latter two designations deriving from the two principal candidates for mayor. W. H. Munro, for the Citizen's ticket, received 110 votes, while Julius Malsh received 112 votes on the People's ticket. But when several individuals filed sworn statements that they had not been entitled to vote, with the contest then ending in a tie, the election judges decided to have the two candidates draw lots. Munro was the winner and took office with the following councilors: J. W. McNutt, S. L. Tibbals, John H. Gerrish, Samuel Howe, and F. Hurlbut for two-year terms; Hiram House, J. W. Guthrie, John Kupfer, J. W. Graham, and A. J. Fitzgerald for one-year terms; and T. J. Black and C. Bernard as justices of the peace. With one or two exceptions, the new officials were among the founders of the town and all were businessmen and property owners. A month later Julius Malsh was installed as a councilor to replace A. J. Fitzgerald who had resigned.7

Municipal Government The mayor and council met to organize several standing committees and to adopt rules of procedure both of which remained in

Trail Town

33

Montana Street, Corinne. Andrew J. Russell photograph, courtesy of the Oakland Museum.

effect with only minor changes throughout the decade of the 1870s. The committees, composed of three members each, were: Finance and Claims, Ordinances, Licenses, Police, Streets and Public Improvements, and Credentials. The council agreed to meet on the first Monday in April, June, August, October, and December; adopted a fine of $1.00 for every absence; allowed a temporary replacement for any member absent from the city for twenty days; and ordered that no member could speak more than twice on a given subject. The recorder was to be the tax assessor, and the town marshal was also going to serve as the supervisor of streets and the collector of taxes, a significance not unobserved by all property owners. The Utah Reporter was named the official paper, expected to publish the actions of the council without expense to the city. But Dennis J. Toohy, editor, made up for this altruism by being named city attorney, a position that did return small amounts such as $5.00 per day to prepare

34

Corinne

the ordinances passed by the council. Toohy reported his own selection "as the most fitting which could have been made. . . ." Apparently, city revenues did not provide for any grand perquisites of office as the council first met in the office of Dr. O. D. Cass and, then, at the hay scales where the marshal was told to furnish the necessary seats and lights. The marshal must have been busy elsewhere; the next minutes recorded, "There being no lights or seats on motion the Reading of the minutes and all business was dispensed with . . . ." The recorder was instructed to purchase twelve chairs at $3.50 each and one table at $12.00 for the council, and the marshal was further ordered to compel the attendance of every member at the next meeting, a maneuver that evidently was not successful because, again, there was not a quorum present. At its working sessions in 1870 the council did undertake the passage of some necessary ordinances that revealed the needs and aspirations of the young town. Regulations were adopted to license dogs and to prevent swine from running at large, the latter problem being a continuing irritant throughout the town's early history. At its second meeting the council passed, on first reading, an ordinance "abolishing polygamy within the City Limits" but did not again bring up the subject, apparently deciding that Corinne must first put its own house in order before attacking the despised Mormon practice. 9 The very next ordinance proposed to restrain "Gaming and Houses of 111 Fame" failed on first vote but finally was passed on April 4, 1870. The regulation must not have been very effective because the council adopted another provision on August 18 to suppress disorderly houses. In another reference to the same problem, a resolution was adopted ordering the justice of the peace to remit onehalf of a fine "imposed by him against certain women found guilty of violating an ordinance of the city." Also, there were ordinances devoted to public health, licenses for circuses and other exhibitions, to prohibit swimming and bathing in Bear River within the city limits, instructing the marshal to inspect the flues and chimneys of all houses for possible fire hazards, to allow Councilman John Kupfer to "discharge Fire Arms on his own premises," to permit S. J. Lees to maintain a tent standing on the corner of Fourth and Montana streets, and to prohibit individuals from carrying concealed weapons or discharging firearms in the streets.10

Trail Town

35