XU S A^CJfU^JJnLX^ a a K x \ < c B M~D

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORYBOARD OF EDITORS

KENNETH L. CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1995

ARLENE H. EAKLE, Woods Cross, 1993

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1994

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1994

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1995

RICHARD W SADLER, Ogden, 1994

HAROLD SCHINDLER, Salt Lake City, 1993

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden, 1995

GREGORY C. THOMPSON, Salt I.ake City, 1993

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-6024 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00.

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate accompanied by return postage and should be typed double-space, with footnotes at the end. Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 1/4 inch MS-DOS or PCDOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. Additional information on requirements is available from the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICA L QUARTERL

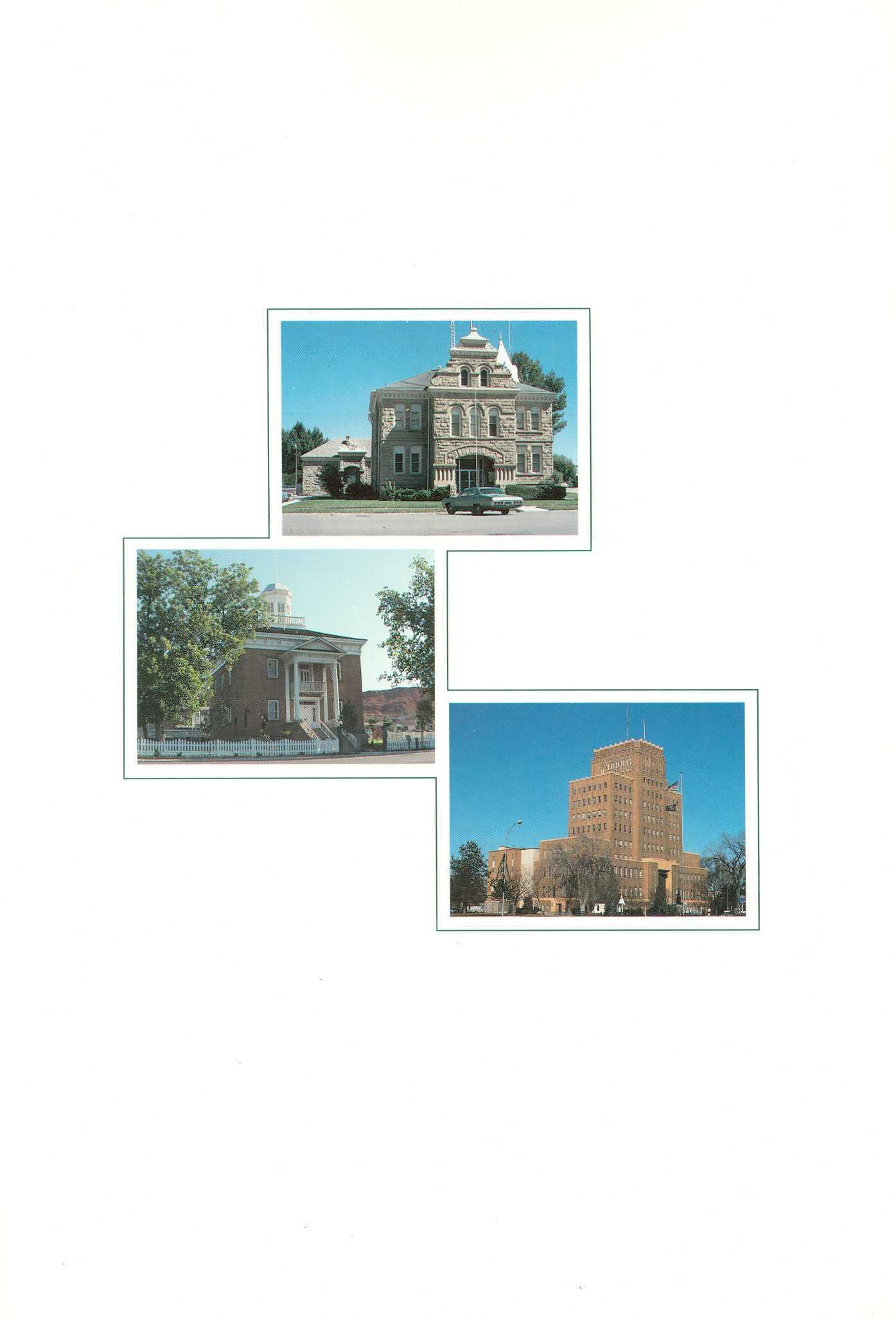

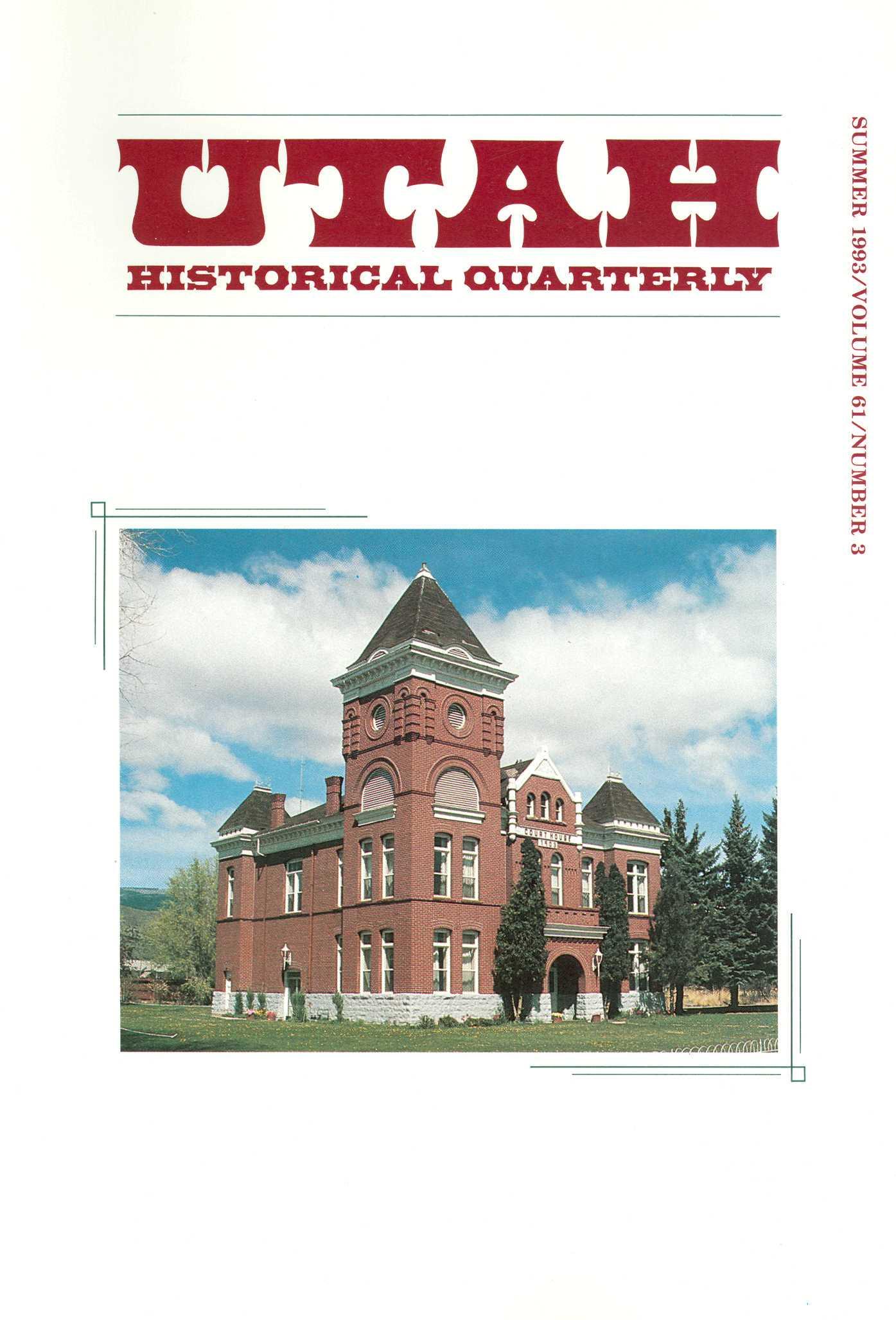

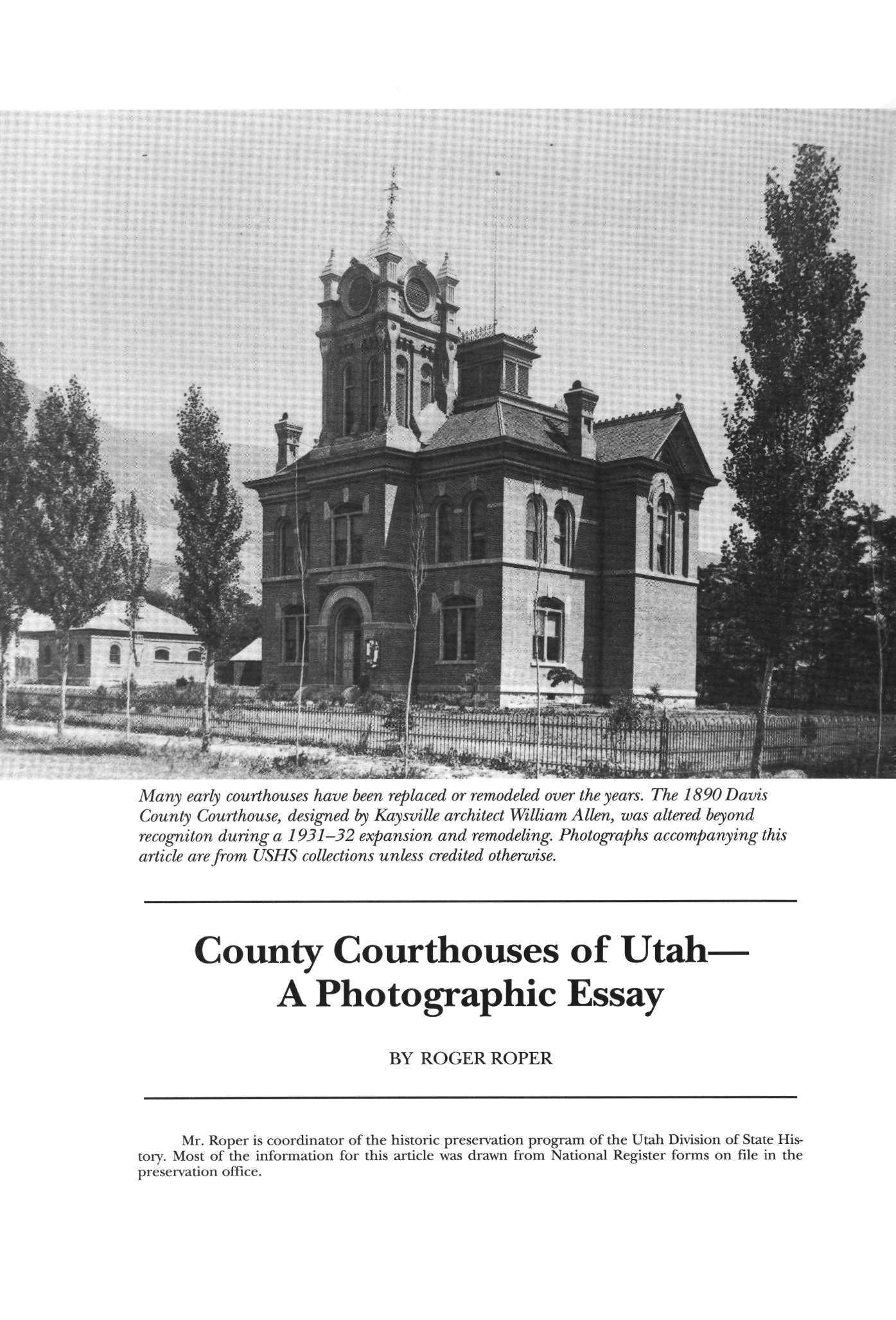

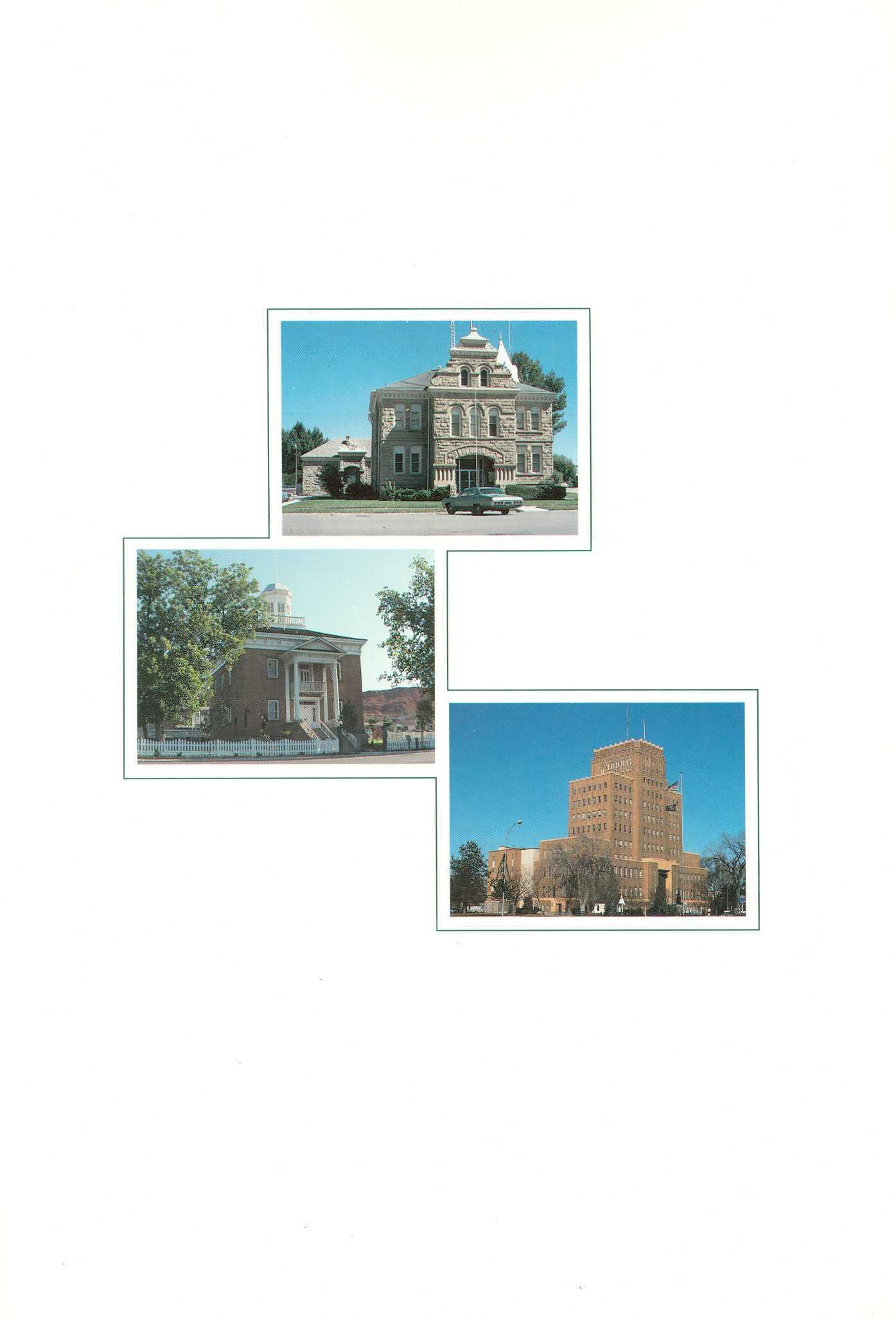

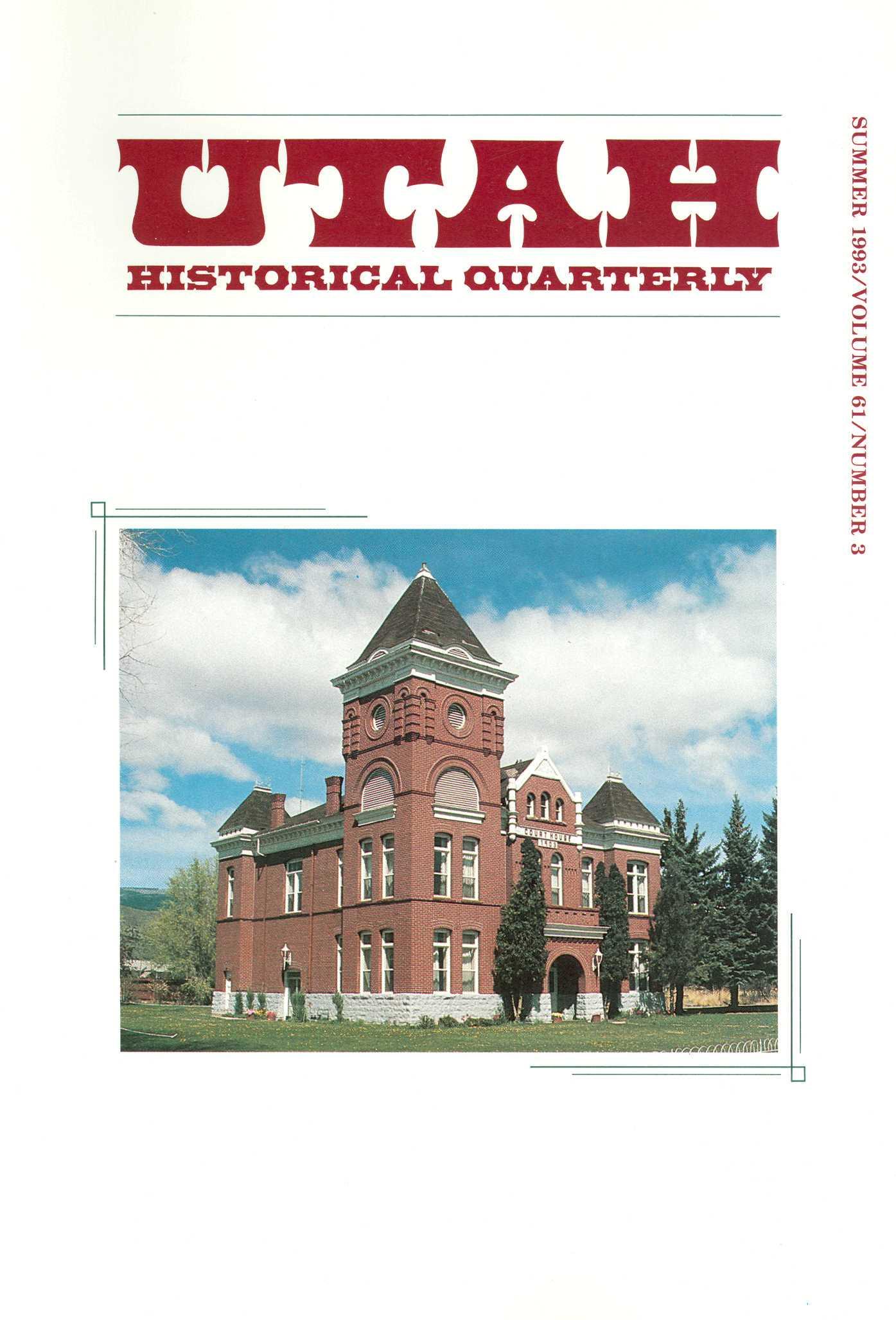

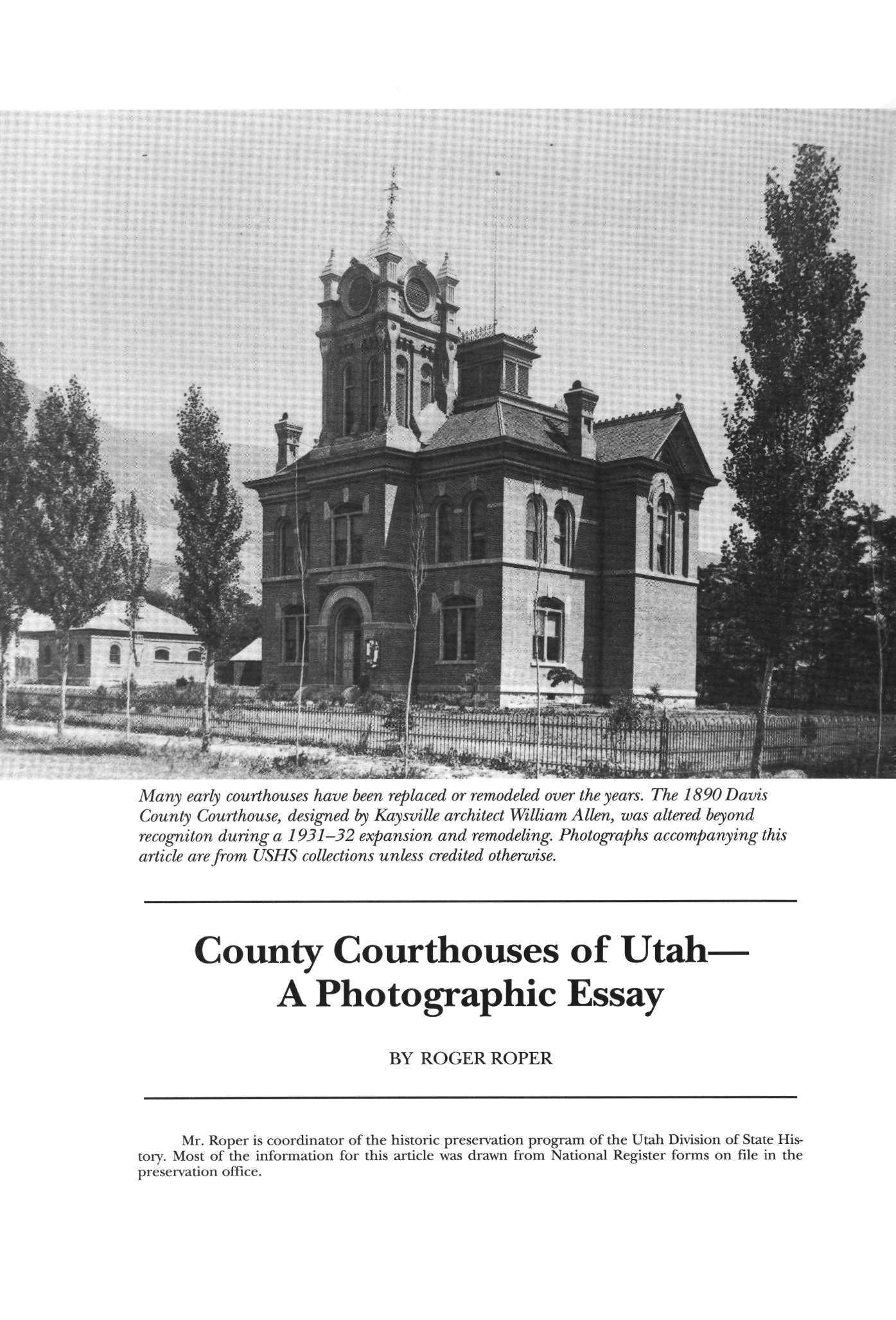

Contents SUMMER 1993 / VOLUME 61 / NUMBER 3 IN THIS ISSUE 207 "SISTERS AT THE BAR": UTAH WOMEN IN LAW CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN 208 UTAH STATE SUPREME COURT JUSTICE SAMUEL R. THURMAN JOH N R. ALLEY, JR 233 REMEMBERING JUSTICE A H ELLETT J ALLAN CROCKETT 249 COUNTY COURTHOUSES OF UTAH— A PHOTOGRAPHIC ESSAY ROGER ROPER 258 THE EMANCIPATION OF THE JUVENILE COURT, 1957-65 REGNAL W GARFF 269 AN AFFAIR WITH A FLAG DO N V TIBBS 280 BOOKREVIEWS 284 BOOKNOTICES 294 THE COVER Four of Utah's historic county courthouses are pictured. On thefront cover is the Piute County Courthouse injunction. On the back cover are the courthouses of Summit, Washington, and Weber counties, located in Coalville, St. George, and Ogden respectively. All are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. USHS collections, preservation office files. © Copyright 1993 Utah State Historical Society

Y

RICHARD E. WESTWOOD Rough-water Man: Elwyn Blake's Colorado River Expeditions JIM ATON 284

RONALD L. HOL T Beneath These Red Cliffs: An Ethnohistory of the Utah Paiutes JOEL C. JANETSKI 285

B CARMON HARDY Solemn Covenant: The Mormon Polygamous Passage KENNETH L. CANNON II 286

STAN LARSON, ed. Prisonerfor Polygamy: The Memoirs and Letters of Rudger Clawson at the Utah Territorial Penitentiary, 1884-87 WILLIAM C. SEIFRIT 288

ANNIE M. SMITH. Ute Tales ALAN D. REED 289

M. CATHERINE MILLER Flooding the Courtrooms: Law and Water in the Far West CRAIG FULLER 290

EDWARD A. GEARY. The Proper Edge of the Sky: The High Plateau Country of Utah MELVTN T. SMITH 291

MARIA S. ELLSWORTH, ed. Mormon Odyssey: The Story of Ida Hunt Udall, Plural Wife Jo AN WASHBURN 293

Books reviewed

In this issue

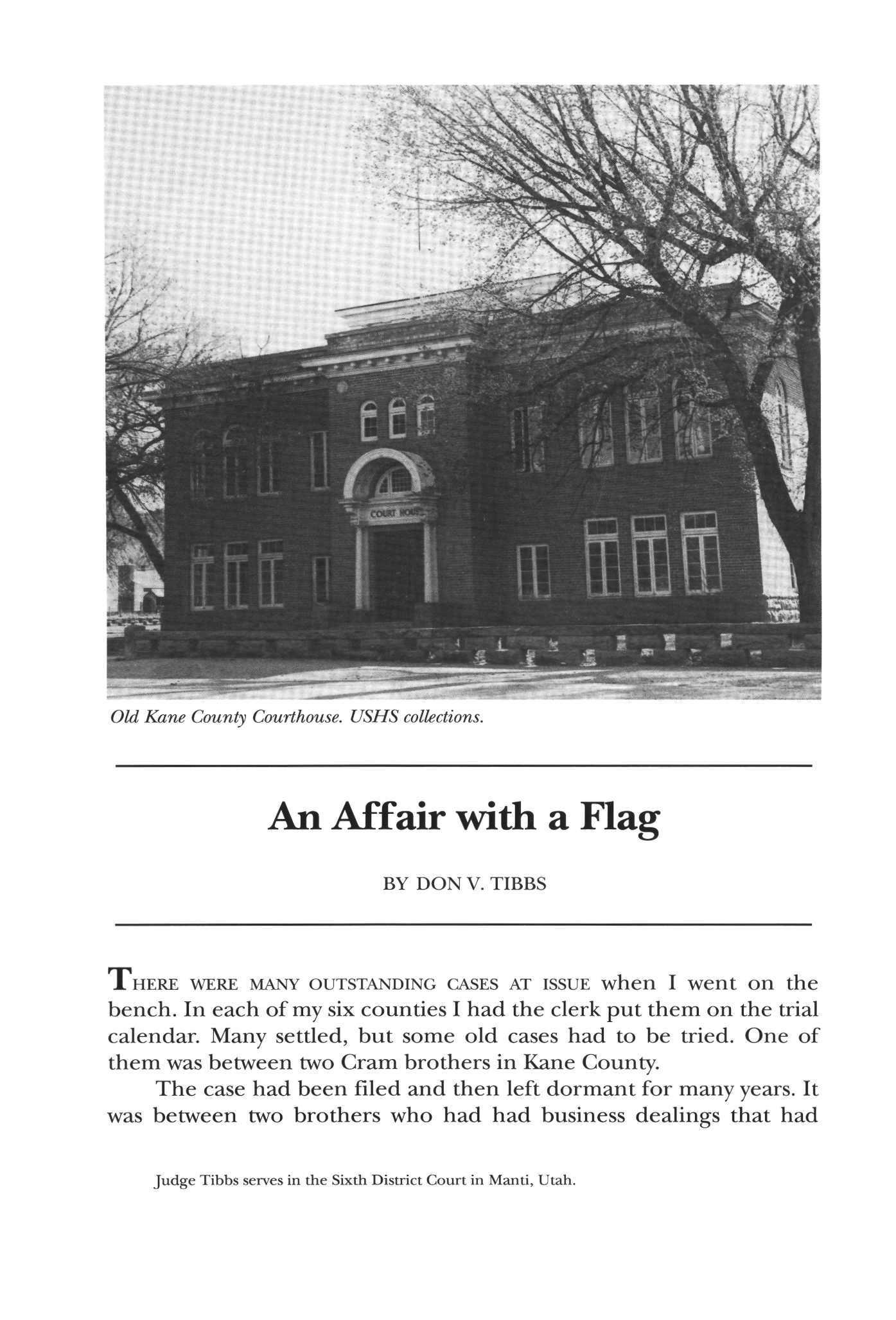

Desiring to promote the history of Utah law and courthouses, the Utah Bar Foundation approached the Utah State Historical Society last year and proposed a joint effort in the production of a special issue of Utah Historical Quarterly. Working together in the call for and refereeing of papers, the two agencies gathered a half-dozen articles that represented the diversity, complexity, and significance of the legal experience in Utah.

A detailed look at the role of women in shaping the state's legal institutions, two biographical sketches, a photo essay on National Register courthouses, an analysis of the juvenile court's evolution, and a judge's lighthearted personal reminiscence were among the topics finally selected.

The Utah Bar Foundation was incorporated December 13, 1963, as a nonprofit corporation. Every attorney licensed to practice law in the state is a member It uses income from gifts, donations, bequests, devises, membership contributions, and interest on lawyer trust accounts to further its many public-service goals. These include projects related to public education regarding the law, legal services to the public including those who might not otherwise be able to obtain professional representation, programs at institutions of higher learning, and charitable and other worthy causes.

Comstock Clayton Foundation, sponsored by Calvin A. Behle, one of the original founders of the Foundation, and his wife Hope, contributed funds to pay for some nice aesthetic touches for this publication, including the full-color cover and a special over-run of 500 cloth-bound copies

As the Utah Bar Foundation approaches its thirtieth anniversary, the Behles and other members can point with special pride to this issue as another entry in their catalog of notable achievements

Utah Bar Foundation standing: Carman E. Kipp, Kipp & Christian; Richard C. Cahoon, Marsden, Orion & Cahoon; James B. Lee, Parsons Behle & Latimer; Stephen B. Nebeker, Ray, Quinney & Nebeker; seated: Ellen M. Maycock, Kruse, Landa & Maycock; Hon. Norman H. Jackson, Utah Court of Appeals; Jane A. Marquardt, Marquardt, Hasenyager & Custen.

Photograph by Robert L. Schmid.

Utah Bar Foundation standing: Carman E. Kipp, Kipp & Christian; Richard C. Cahoon, Marsden, Orion & Cahoon; James B. Lee, Parsons Behle & Latimer; Stephen B. Nebeker, Ray, Quinney & Nebeker; seated: Ellen M. Maycock, Kruse, Landa & Maycock; Hon. Norman H. Jackson, Utah Court of Appeals; Jane A. Marquardt, Marquardt, Hasenyager & Custen.

Photograph by Robert L. Schmid.

"Sisters at the Bar": Utah Women in Law

BY CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN

BY CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN

I N 1872 ELIZABETH KANE, WIFE OF Col. Thomas L. Kane of Philadelphia, a long-time friend of Mormon church president Brigham Young, traveled with her husband on Young's annual winter pilgrimage to south-

Cornwall Madsen is an associate professor of history and senior research historian with the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History at Brigham Young University

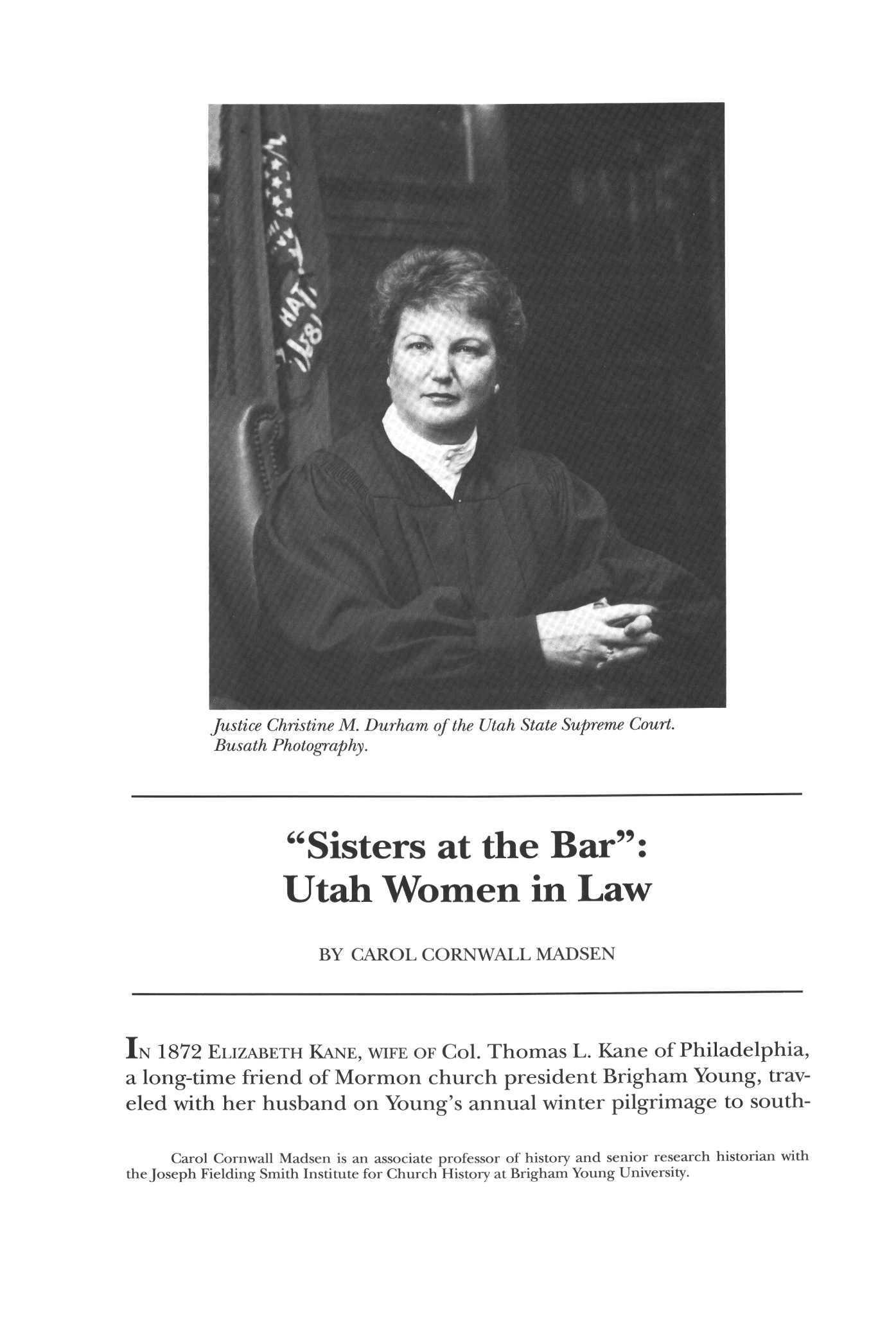

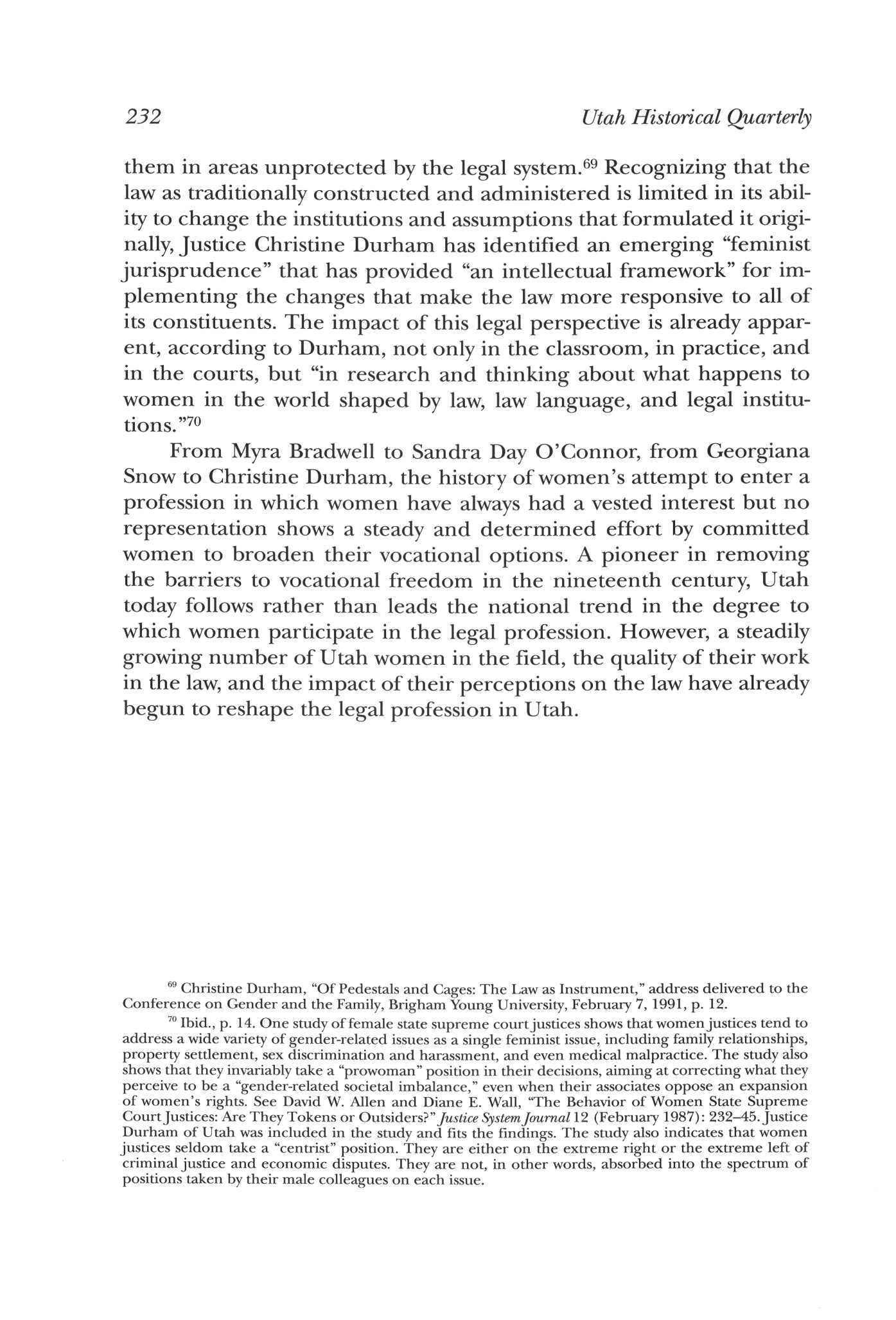

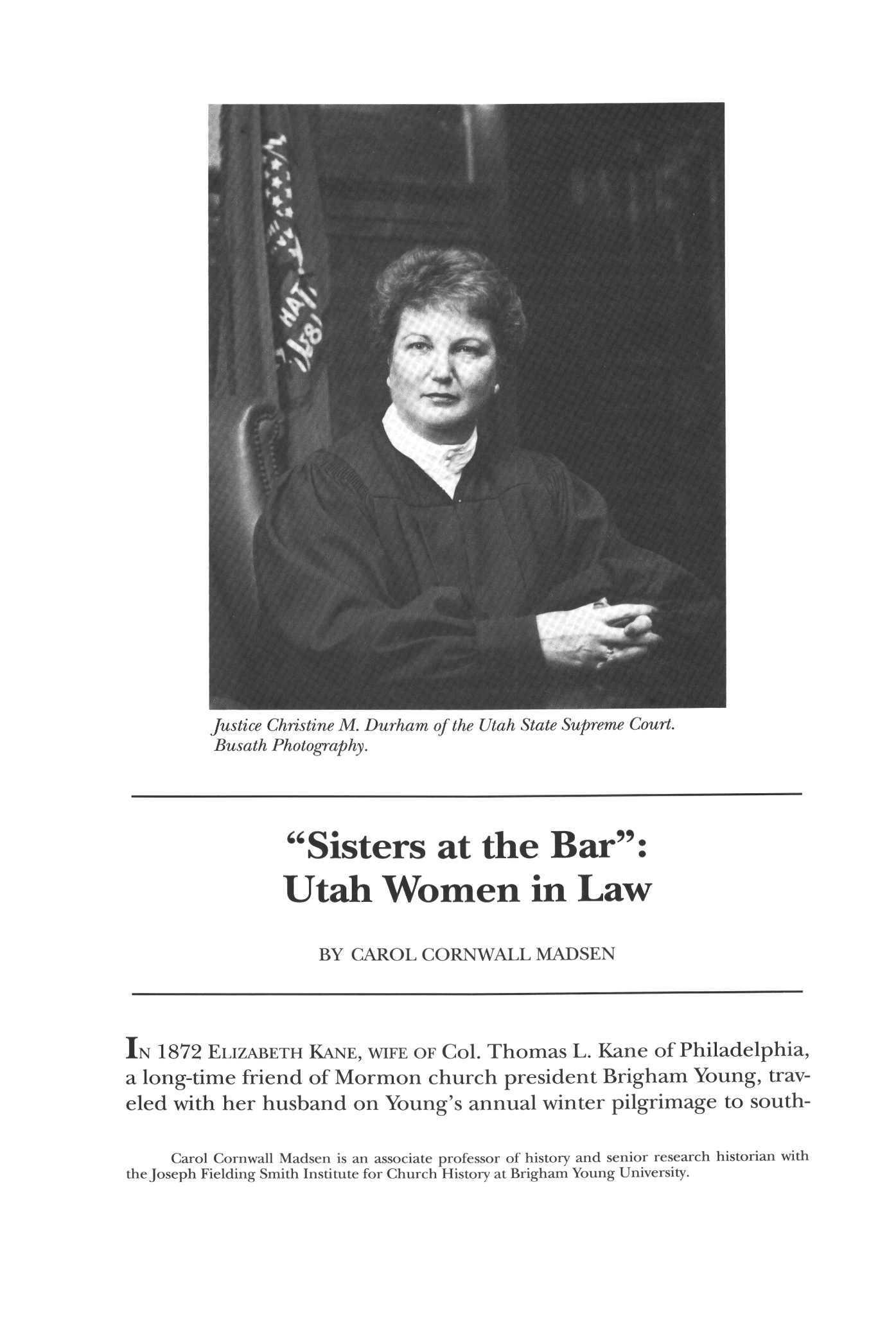

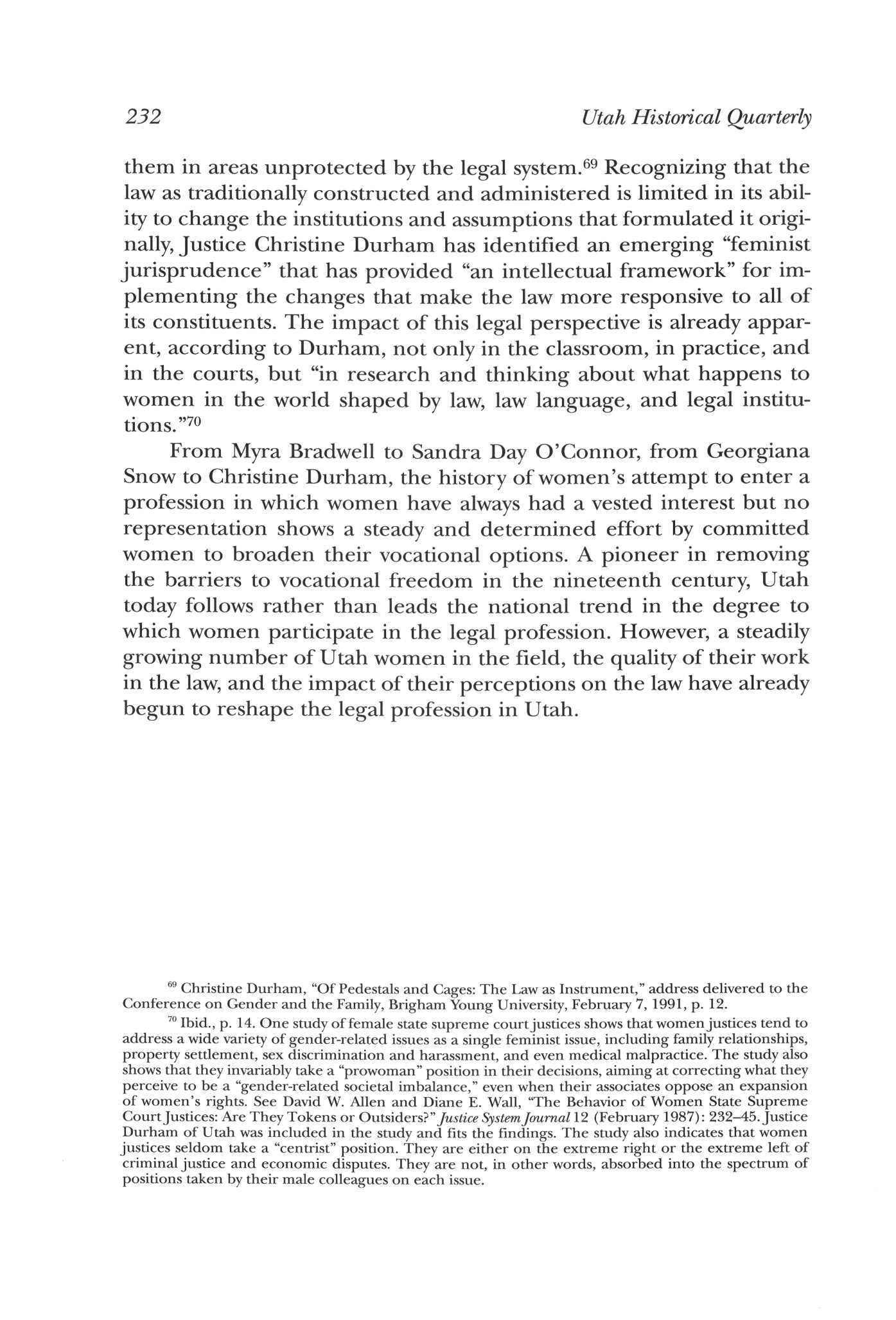

fustice Christine M. Durham of the Utah State Supreme Court. Busath Photography.

Carol

ern Utah After visiting numerous Mormon communities along the way she observed, "They close no career on a woman in Utah by which she can earn a living."1 Indeed, frontier Utah erected few legal or social barriers against women's entry into gainful employment, including the so-called learned professions of law, medicine, and higher education. Although this flexibility reflected the exigencies of a developing community, it also demonstrated the assumption that women were capable of such learning, a view that did not enjoy a consensus in nineteenth-century America. At a time when respected voices in the medical profession warned that the rigors of education would unbalance women's physiological makeup, women who chose professional training did so at a perceived risk. Ever pragmatic, Brigham Young countered these prevailing theories and encouraged women to study law, medicine, and other branches of learning to meet Utah's need for their professional contributions.2

The story of Utah women's entry into law isjust one chapter in a larger story that features women willing to push against the constraints of social custom and claim a place in the professional world, reaping disapproval, ridicule, and, frequently, social isolation in the struggle. Although many of the legal barriers to women's right to occupational choice began falling throughout the country soon after the beginning of this century, it has been only in the last two decades that the social and attitudinal impediments that have prevented women from entering the mainstream of professional life have significantly diminished

The entry of women into the work force introduced a variety of complex gender issues, many of which were unique to professional women It raised questions of propriety as well as capability even as it defined new ways for women to relate to society, forcing new interpretations of woman's sphere and those elements of cohesiveness that characterized the female culture.3 Subject to the same discriminatory

1 Elizabeth Wood Kane, Twelve Mormon Homes Visited in Succession on aJourney through Utah to Arizona (Salt Lake City: Tanner Trust Fund, University of Utah Library, 1974), p 5

2 Brigham Young, Sermon in the Old Tabernacle, July 18, 1869, reported by David W Evans, Journal of Discourses, 20 vols (Liverpool, 1871), 13:61

3 As delineated by Joan Jacob Brumberg and Nancy Tomes in "Women in the Professions: A Research Agenda for American Historians," Reviews in American History 10 (June 1982): 275-96, professional women represented a commitment to education, independence, and personal aspirations that exceeded or even contravened the economic rationale for most working women Th e authors raise questions about the tension between the methods and approaches of the professional and nonprofessional or volunteer woman Th e theory that women wielded more political power and public influence through a separate female culture than through integration into traditionally male public institutions and professions is advanced by Estelle Freedman in "Separatism as Strategy: Female Institution Building and American Feminism, 1870-1930," Feminist Studies 3 (Fall 1979): 512-29

Utah Women in Law 209

practices aswomen wage earners, professional women also faced legal and educational barriers as well as persistent social disapproval unknown to their working class sisters The distinction between jobs and careers involved more than class differences. The professions pitted men and women against each other in competitive arenas dominated by male rules, male institutions, and male values. The story of women in the professions is not only an account of their struggle to claim a portion for themselves but a story of the significant impact their presence is making, particularly in the field of law.

Not until after the Civil War did women mount serious attempts to enter the professional fields Barriers to entry were different in the various professions and the progress of women in each followed different routes Utah was among the first in the nation to permit women into the learned professions, but beyond the entry point the historical development in Utah generally paralleled that of the rest of the country.

Unlike those who entered higher education and medicine, women who chose law as a profession encountered major legal restraints. Under the common law married women could not act as independent legal entities and were thus unable to make contracts, sue, write wills, and own or convey property in their own name. Married women could not, therefore, enter into contracts with their clients or sue on their behalf, a common law disability similarly extended to single women who desired to become lawyers Moreover, neither married nor single women were eligible to vote or hold office under the common law, a restriction that was interpreted in most states to include the position of attorney, who was an officer of the court.4 Some state statutes expressly prohibited women's admittance to the bar or contained masculine pronouns in delineating qualifications for lawyers (indicating the "intent" of lawmakers).

The experience of BelvaAnn Lockwood in obtaining law training and admission to practice demonstrates the obstacles that faced women of her generation Refused admission to the law school of Columbian College (later George Washington University) and Georgetown and Howard universities, she gained acceptance to the National

4 In some cases this objection was overturned. See Kilgore v. The State of Pennsylvania as quoted in D Kelly Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar: Women and Legal Education in the United States, 1870-1890, "Journal of Legal Education 28 (1977): 489 In other instances this restriction, relating only to married women, did not inhibit some judges from ruling against any woman, married or single, from admission to practice

210 Utah Historical Quarterly

University Law School in Washington, D.C., in 1871.Despite completing the course two years later, she was awarded a diploma only after appealing to U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant, ex-officio president of the law school. She was then admitted to the bar of the District of Columbia When one of her legal cases reached a federal Court of Appeals, however, her right to plead was denied because, the court ruled, "a woman is without legal capacity to take the office of attorney."5 Her application to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1876 was similarly denied The ruling could be changed only by congressional legislation. Finally, in March 1879, after three years of lobbying, Belva Lockwood became the first woman admitted to the highest court of the land. It took several more years before she was admitted to practice in her native state of New York.6

Of the three learned professions, the law seemed most incongruous with the prevailing notions of womanhood. This psychological barrier was constructed from contemporary theories of woman's dependence upon emotion and intuition rather than intellect, a characteristic clearly impairing woman's performance in the legal sphere, it was assumed. Additionally, a woman's limited physical capacity, it was argued, would naturally preclude the intense concentration and long working hours required by the profession Moreover, common wisdom affirmed that male competitiveness and aggressiveness, foreign to feminine nature, best served the practice of law.7

Most formidable, the profession represented a role conflict of immense proportions As one nineteenth-century critic argued:

How would a lawyeress be able to consult with her clients, when she was attacked by the nausea of the first few months of pregnancy? And afterward what a figure she would make in court, when, the months of interesting situation being advanced, her curved lines become crushed with an anterior round line? And if the pains should come upon her in the heat of argument! That would be fine indeed! Would she invite her

5 Quoted in Thomas Woody, A History of Women's Education in the United States, 2 vols (New York: Science Press, 1929), 2:378.

6 Edward T James, Janet Wilson James, and Paul S Boyer, eds., Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary, 1607-1950, 3 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), 2:413-16; see also Julia Davis, "Belva Ann Lockwood, Remover of Mountains," American Bar Association Journal 65 (June 1979): 924-28

7 Barriers to female entry into the legal profession are discussed in more detail in Ellen Spencer Mussey, "Women Attorneys," American Bar Association Journal 9 (January 1923): 62-63; Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar," pp 486-93; Kathleen E Lazarou, "'Fettered Portias': Obstacles Facing Nineteenth-century Women Lawyers," Women LawyersJournal 64 (Winter 1978): 21-30: Patricia M. Hummer, The Decade of Elusive Promise, Professional Women in the United States, 1920-1930 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1976), pp. 43-49; Woody, History of Women's Education, 2:378-80.

Utah Women in Law 211

colleagues to serve her as midwives? And in childbirth, farewell to business! Poor clients! I assure you that I laugh to myself thinking of the ridiculous figure that a woman lawyer would make. 8

Women's maternal and domestic duties were more than female occupations to the nineteenth-century mind; they were identifying characteristics, and it was a conceptual leap of some magnitude to separate women from these functions.

Legal or social barriers emerged in all aspects of women's attempt to become lawyers: acquiring a legal education, gaining admittance to the bar, and practicing. Arabella Mansfield was one of the few women in the beginning to meet success. In 1869, having studied law privately with her husband, she became the first woman to be admitted to a state bar, Iowa, because the district courtjudge who ruled on her application was willing to construe the male pronouns relating to qualifications of lawyers as inclusive of women. 9 Ada Keply was not so fortunate After graduating in 1870 with the distinction of being the first woman graduate of a law school, the Union College of Law (now Northwestern), she was refused admittance to the Illinois Bar.10

One of the most publicized efforts was Myra Bradwell's. She studied law in her husband's law office in Illinois, a traditional apprenticeship utilized by many lawyers until the early part of the twentieth century. She edited a legal newsletter and operated a printing shop for the publication of legal forms and documents Deciding to become a lawyer herself, she applied for admittance to the Illinois Bar but was refused on the basis of her marital status and sex Married women could not make contracts, the court asserted, and the common law prohibited women from engaging in the practice of law "That God designated the sexes to occupy different spheres of action, and that it belonged to men to make, apply, and execute the laws, was regarded as an almost axiomatic truth," the court concluded.11 Bradwell then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court on the grounds that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed her the right to choose her own vocation. The Supreme Court concurred in the lower court's ruling. The majority decision reaffirmed the law's instrumentality in sustaining social values:

Quoted in Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar," p 491 Lazarou, "'Fettered Portias,'" p 22

0 Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar," pp. 485-86.

1 Bradwellv. Illinois, 55 Illinois 535 (1869), quoted in Lazarou, "'Fettered Portias,'" p 23

212 Utah Historical Quarterly

The claim of the plaintiff, who is a married woman, to be admitted to practice as an attorney and counselor at law, is based upon the supposed right of every person, man or woman, to engage in any lawful employment for a livelihood The claim assumes that it is one of the privileges and immunities of women as citizens [under the 14th amendment] to engage in any and every profession, occupation or employment in civil life.

It certainly cannot be affirmed, as a historical fact, that this has ever been established as one of the fundamental privileges and immunities of the sex. On the contrary, the civil law, as well as nature herself, has always recognized a wide difference in the respective spheres and destinies of man and woman Man is, or should be, woman's protector and defender. The natural and proper timidity and delicacy which belongs to the female sex evidently unfits it for many of the occupations of civil life. The constitution of the family organization, which is founded in the divine ordinance, as well as in the nature of things, indicates the domestic sphere as that which properly belongs to the domain and function of womanhood. The harmony, not to say identity, of interest and views which belong or should belong to the family institution, is repugnant to the idea of a woman adopting a distinct and independent career from that of her husband. 1 2

An attempt by Lavinia Goodell to join the bar in Wisconsin elicited the same type of sociolegal response that focused primarily on law as an undesirable vocation for women:

There are many employments in life not unfit for the female character The profession of law is surely not one of these The peculiar qualities of womanhood, its gentle graces, its quick sensibility, its tender susceptibility, its purity, its delicacy, its emotional impulses, its subordination of hard reason to sympathetic feeling, are surely not qualifications for forensic strife Nature has tempered woman as little for the juridical conflicts of the court room as for the physical conflicts of the battlefield.13

The rulings were already defensive, however. Within a decade after Goodell lost her appeal, twelve states and territories and the District of Columbia admitted women to the bar through judicial decree while eight additional states did so through revised legislation.14 They

12 Bradwellv. Illinois, 83 U.S 130 (1873)

13 In re Goodell, 39 Wis> 232 (1875)

14 States admitting women through judicial enactment were Iowa, Missouri, Michigan, Utah, Maine, Indiana, Kansas, Connecticut, Nebraska, Washington Territory, the United States Circuit and District Courts in Illinois and Texas, and the District of Columbia Those awaiting legislative action were Illinois, California, Minnesota Massachusetts, Oregon, Wisconsin Ohio, and New York See Ellen A Martin, "Admission of Women to the Bar," Chicago Law Times 1 (November 1886): 76-92, as reprinted in Lazarou, "'Fettered Portias,'" p 30

Utah Women in Law 213

had all capitulated to the unremitting efforts of women applicants to bring the law into step with a society that was slowly beginning to respond to women's changing legal status and their demands for a greater public role.

Throughout the nineteenth century the study and practice of law were nonstandardized and generally unregulated There were no uniform licensing procedures or standards, no conformity among the law schools that then existed, and only a minimum amount of reading or training with an attorney required for admittance to a state bar Admission to most bars required no legal examination and no evidence of training, only a recommendation from a practicing attorney vouching for the candidate's moral character rather than his legal competence. Until well into this century few states required attendance at a law school or a law degree for admittance to the bar.15

Nevertheless, the number of law schools grew from 31 in 1870 to 124 in 1910, along with the development of degree-conferring curriculums. Some began to open their doors to women. 16 Most women, however, received their training in the part-time law schools, 2 of which were exclusively for women: the Portia School of Law in Boston and the Washington College of Law in Washington, D.C. In 1890 there were only 10 part-time schools with 537 students, but their number grew to 64 by 1916, enrolling 10,734 students, almost as many as in the 76 full-time law schools.17

As more universities and colleges established law schools, they also developed stringent admission policies and uniform curricula. Standardized class work among the more prestigious eastern schools became de rigueur in response to a drive in 1893 by the Section on Legal Education of the American Bar Association. The Association of American Law Schools, established in 1890, also focused its attention on improvement in legal education. The part-time schools, unable to compete, lost acceptability as legal training fields. Women were a casualty of this development.

With the rise of professional law schools, independent study or apprenticing also lost favor. Would-be lawyers were forced to turn to the law schools for training. The two major regulatory associations,

15 Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Seventh Annual Report (1922), p 86, as quoted in Hummer, Decade of Elusive Promise, p 47

16 Among the first were Union College (1870); Michigan (1871); Washington University, St Louis (1871); Harvard University (1872); Iowa State (1873); National University, Washington, D.C (1873) See Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar," p 494

17 In 1916 there were 76 regular day schools enrolling 11,469 students

214 Utah Historical Quarterly

the American Bar Association and the Association of American Law Schools, had succeeded by 1920 in making three years the standard period for law training leading to a degree and had insured that by 1925 at least two years of college education were requisite for entrance to law school. Some few states continued to require only study in a law office for bar candidacy. Approved law schools that still prohibited women in 1920 were Catholic University, Columbia, Harvard, University of Florida, and Washington and Lee.18 Not until 1972 were women admitted to all ABA approved law schools.19

Fewer women actually practiced law than studied it. Not until 1920 did states begin to pass statutes requiring law school training for bar admission, and not until then had all states except Delaware removed restrictions against women's admission to their bar associations.20 However, after admission to the bar, women faced additional impediments in associating with law firms and attracting clients Often less well trained than their male counterparts, they had to prove their ability "It undoubtedly requires the courage of one's convictions to enter upon a field where opposition is so strong," wrote one early woman lawyer.21 Those with male relatives in the profession fared best, assisting lawyer husbands or fathers in writing briefs or devoting themselves "chiefly to office work." Some moved into law-related fields or public law. Others went west where they faced less discrimination and the profession as a whole had more opportunity for expansion. A fifth of the women lawyers before the turn of the century never practiced at all.22

The 1878 organization of the American Bar Association was a response to similar local and state organizations. It remained an elitist group for many years, however, attracting lawyers primarily from the more prestigious eastern law schools As late as 1900, of the 113,460 lawyers practicing in the nation, only 1,540 belonged to the ABA No women were allowed tojoin until 1918

18 Bureau of Vocational Information, Training for the Professions (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Service, 1924), p 432-33

19 Donna Fossum, "Women in the Legal Profession: A Study of Social Change" (Ph.D diss., University of New York at Buffalo, 1981), p 3

20 Hummer, Decade of Elusive Promise, pp 47-48

21 Marion Weston Cottle, "The Prejudice against Women Lawyers: How Can It Be Overcome?" Case and Comment 21 (October 1914): 372, as quoted in ibid., p. 48.

22 Weisberg, "Barred from the Bar," pp 494-97

Utah Women in Law 215

Shut out from the networking and support system that membership in the ABA provided, women lawyers formed the National Association

of Women Lawyers in 1910 and the next year published the first issue of the Women LawyersJournal. Many women lawyers refused tojoin, fearful that its existence would either deter or erase the possibility of membership in the ABA. Eight years later, when the ABA opened its doors to women, many of those who joined also retained membership in the women's association. An early issue of the Journal outlines appropriate etiquette and dress for the woman lawyer at the turn of the century:

The principal drawbacks to a woman's success when pitted against man in the legal battle are to be found in the handicaps of sex. The voice, physical appearance, and attire of the average woman lawyer do not produce the impression of authority and aggressiveness which are characteristic of the average man lawyer Legal ability alone cannot make up for lack of power and authority, and the woman who would succeed in jury trials should bear in mind the fact that one of the chief ways of impressing an audience is through the speaker's voice A highpitched, nervous-sounding voice carries little conviction with it, and the woman jury lawyer should, if necessary, prepare herself for her work by a special course of training in the art of effective speaking

In regard to her personal appearance, there are several things which the woman trial lawyer will do well to observe She should never appear in court in anything but a dignified street costume, and it is advisable that she should remove her hat before addressing the judge The tendency on the part of women to feel that their sex entitles them to receive, rather than to pay, deference should never be allowed in the court room. 2 3

In Utah the experience of women in law diverged somewhat from the national pattern. The practice of law was not highly regarded by the American public generally, but it met no stronger opposition than in territorial Utah. The Mormon experience with the law had been frustrating and disappointing, engendering distrust of lawyers as well as the legal system. Though he later supported the study of law, Brigham Young did not mince words in describing his feelings toward lawyers in 1852:

To observe such conduct as many lawyers are guilty of, stirring up strife among peaceable men, is an outrage upon the feelings of every honest, law abiding man To sit among them is like sitting in the depths of hell, and their hearts are as black as the ace of spades They love sin, and roll it under their tongues as a sweet morsel, and will creep around like wolves in sheep's clothing, and fill their pockets with the

23 Women LawyersJournal (May 1911), n.p., as quoted in D X Fenten, MS. Attorney (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1974), pp 33-34

216 Utah Historical Quarterly

fair earnings of their neighbors, and devise every artifice in their power to reach the property of the honest, and that is what has caused these courts.24

That same year the Utah Legislative Assembly almost legislated the legal profession out of existence An act regulating attorneys provided that a man or woman (italics added) could act as attorney for himself or herself or could choose any person of good moral character to represent him or her.25 Even more unusual than this grant of legal power to non-lawyers was its application to women. The statute empowered Utah women to act as counsel not only for themselves but for others. There is little evidence that women availed themselves of this privilege although the diary of MarthaJane Knowlton Coray suggests the possibility that she might have assisted a friend in court in 1874 under the provisions of this act.26 Nevertheless, there were lawyers in Utah, and legislators did establish qualifications for practice, primarily proof of good moral character and a favorable report of an examining committee to that effect. If an applicant had been admitted to the highest court of another territory or state, proof of that sufficed for admittance to the Utah Bar. The statute contained no prohibitive language relative to women. 27

On September 21, 1872, while Myra Bradwell of Illinois was waiting to hear the Supreme Court's decision on her application to practice, two women applied for admission to the Utah Bar: Phoebe W. Couzins and Georgiana Snow Couzins, a non-Utahn, had already been admitted to the Arkansas and Missouri bars after graduation from the Washington University Law School in Missouri. Her admission to Utah was automatic since she had proof of prior acceptance to two other bars. In welcoming Couzins to the bar, Utah Supreme Court Justice James McKean, a federal appointee, reflected Brigham Young's altered view of the profession:

It has been said by a learned writer that law is the refinement of reasoning Perhaps it is natural to infer that those who have the most refinement ought to be very clear, perhaps intuitive reasoners. Certainly no gentleman of this bar would deny that, in social life, woman's influence is 196

Andrew Love Neff, History of Utah: 1847-1869 (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), p

25

Utah Women in Law 217

An Act for the Regulation of Attorneys, Section 1, February 18, 1852, 1851-52 Laws of Utah 55

26 Martha Jane Knowlton Coray, Diary, April 17, 18, 20, 21, 1874, Special Collections, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo

27 1 Utah 6

refining and elevating. May we not hope that the honorable profession of the law may be made even more honorable by the admission of women to the bar It strikes us as a novelty, gentlemen, but everything in the line of progress is, at some time or other, a novelty I very cheerfully admit Miss Couzins to this bar and, gentlemen, I present to you our sister at the bar?8

The implication is obvious that far from being debased by entering a profession traditionally masculine, women would refine and elevate the profession to their own standards. Snow, a local woman, had studied law by reading in her father's law office and serving as his clerk for three years. Zerubbabel Snow had served as an associatejustice of the Utah Supreme Court and as a Salt Lake City attorney. Though Georgiana was well known in Utah legal circles, she went before the committee of examiners as the law required Some feared that had the court admitted her without such an examination, "some young, incompetent gentlemen might apply here and plead that as precedent in his case and so place the court in the embarrassing position of appearing to have one rule for one sex and another rule for the other sex."29 The court again enthusiastically welcomed a woman to the bar:

It may be pertinent for the court to remark that Miss Snow will find in Utah an ample field for the exercise of her professional talent [T]he fact that she has long resided here, and that she is the daughter of a lawyer, will be of great service to her, giving her much advantage over strangers who come here, and especially in listening to the complaints of her own sex. 30

Judge McKean called on prevailing gender stereotypes to demonstrate women's unique contribution to the profession The notions that female qualities would enhance the profession or that they would be useful in providing legal service to other women were not unique to Utah, but neither were they fundamental to the gradual acceptance of women in the practice. Georgiana Snow, however, used her legal training in other pursuits. She accepted appointments as a notary public and territorial librarian; and after her marriage and move to Wyoming she entered politics, serving a term as an alternate delegate to the 1892 presidential convention.31

218 Utah Historical Quarterly

28 DeseretNews Weekly, September 25, 1872 Italics added 29 Ibid See also the Woman's Exponent, October 1, 1872, p 68 30 Ibid 31 Woman's Exponent, February 15, 1874, p. 140; and March 1, 1874, p. 149.

The admission of these two women to the Utah Bar created considerable notoriety for Utah, then undergoing a national antipolygamy campaign that characterized Utah women as subjugated and repressed. The Missouri Republican, among other newspapers, in commenting on the court's reception of these women, noted that Utah's "social system seems to have been the lock and key by which women have at last entered into the wider, nobler sphere for which they have prayed and worked." Other newspapers commented on the anomaly of a society that condoned both polygamy and female vocational freedom.32

The record shows no other female applicants to the Utah Bar until 1892 when Josephine Kellogg, a Provo, Utah, woman, was admitted A newspaper article that same year indicates that an unnamed woman and a "Miss Lee," possibly the daughter of Salt Lake City attorney Orlando Lee, graduated from eastern law schools about this same time and had found employment in the law offices of their fathers while awaiting admission to the bar Two other Utah women were noted as studying in eastern colleges.33

Margaret Beall Connell, admitted to the bar in 1908, is the only woman designated as an attorney in The History of the Bench and Bar in Utah, published in 1913, though two others are mentioned as studying law.A native of Ohio, Connell took an extension course at the University of Chicago and later attended the University of Berlin in Germany She read for the law over a period of years, completing her legal education at the University of Utah and becoming one of its first women graduates. She worked in the federal court in Utah as a deputy clerk and later moved to Los Angeles where she set up her

32 Woman's Exponent, October 15, 1872, p 73 The decade of the 1870s also marked a surge of female interest in medicine, with more than a dozen Utah women studying for their medical degrees in eastern colleges Women were also represented on the faculties and Boards of Trustees of the University of Utah, Brigham Young Academy in Provo, and Brigham Young College and the Agricultural College in Logan.

33 Woman's Exponent, June 1, 1892, p 172

Utah Women in Law 219

Margaret Beall Connell was admitted to the bar in 1908. From The History of the Bench and Bar in Utah

own practice.34 Agnes Swan (Bailey) is listed in the 1911 Salt Lake City Directory as having passed the bar that year and set up practice in the Deseret News Building, although her name is not on the Supreme Court Register of admittees.

Between 1902, when the register begins, and 1940, 19 women were admitted to the Utah Bar. Evidently not all practiced law. The 1900 Utah Census reports only 1 woman was in active practice (and 433 male lawyers), 2 women in 1920 (444 men), 5 women in 1930 (598 men), and 8 women in 1940 (613 men). 3 5 Before World War II the lawwas not a popular profession for Utah women.

Utah did not offer formal legal education until 1907 when the University of Utah Law School was organized.36 Granting only a twoyear certificate at first, from 1911 until 1967 it awarded a bachelor of law degree. Students could begin law school during their senior year of college, receiving a B.A. after their first year of law school and an LL.B. after two additional years. Since 1967 graduation from the U. in law confers ajuris doctor degree.

Very little data is presently available about female law students during its earliest years, but one of the most prominent women graduates of the U. Law School before World War II was Reva Beck Bosone who received her degree in 1930. She was the only female graduate that year, although another woman had entered law school with her. The study of law became a springboard for Bosone to both a judicial and a legislative career. Her mother had once told her that if she wanted to do good, "go where the laws are made." This counsel evidently initiated a lifetime desire to be a legislator, and she determined that the profession of law was the best training for that career Upon graduation she worked with her lawyer brother and later set up practice with her husband in Helper, Utah. Two years after graduation she was elected to the Utah State Legislature and four years after that she was appointed a cityjudge, serving until 1948. She was elected twice

34 History of the Bench and Bar in Utah (Salt Lake City, 1913), pp. 125-26.

35 Based on data in the Twelfth through the Sixteenth Censuses published after each census by the Bureau of the Census as Special Reports-Occupations (Washington, D.C , 1904-52)

36 In 1853 territorial legislator Hosea Stout recorded in his diary that he and several members of the bar and "other gentlemen" met at the State House with Judge Zerubbabel Snow "to take into consideration the propriety of establishing a law school under the direction of Judge Snow who tenders his service as a teacher gratis for the benefit of all those who wish to enter into the study of law the Judge gave us a short lecture on the nature and origin of government & law after which it was agreed to establish the school and meet next Tuesday evening at the same place." Hosea Stout, Diary, December 2, 1851, reprinted in Kate B Carter, ed., "The Pioneer Attorney," Treasures of Pioneer History, 6 vols (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1952-57), 4:266

220 Utah Historical Quarterly

to the U.S. Congress, the only woman from Utah in that legislative body until the election of 1992.37

In 1930, when Bosone graduated, women constituted only 2.1 percent of the profession nationally, and only 5 of Utah's 603 practicing lawyers were women Nationwide, throughout the 1920s and 1930s women were clustered in a limited range of legal work such as briefing, probating, abstracting, examining titles, and preparing income tax returns. They were seldom found in corporate or international law, and only a few were litigators or involved in criminal defense.38

Most women graduates between the wars, both in Utah and elsewhere, were independently motivated to study law, viewing it less as a route to public service or social betterment than as a means to fulfill personal aspirations. Utahn Dorothy S. Merrill is representative. Like Bosone, she had parental support to study law but did not choose public ends. A brilliant, ambitious woman, she attended the University of Utah and then its law school, graduating in 1931 at the age of twenty-two She took additional legal training at the University of Chicago, receiving aJ.D. degree with a specialty in wills and trusts. In 1932 she married Harrison Brothers who had just completed his legal studies at Stanford University. She set up her practice independently from her husband, who embarked on a career in finance. Although she later moved into the field of stocks and bonds, she retained her law practice and a career independent of her husband. In the absence of a local women's law association, Merrill joined the Utah Business and Professional Women's Club. A singular honor was appointment by her male peers to membership on the Utah State Code Commission empowered to revise the state's legal code.39

38

Utah Women in Law 221

Reva Beck Bosone. USHS collections.

37 Beverly B Clopton, Her Honor, theJudge: The Story of Reva Beck Bosone (Ames: Iowa State University Press, 1980), pp 57-60 Utah's second female representative, elected in 1992, is Karen Shepherd

U.S. Bureau of Vocational Information, Training for the Professions (Washington, D.C , GPO, 1924), p 431

39 Interview with Margaret Merrill Nelson Brothers, a sister, on October 15, 1986, in Salt Lake City.

The presence of women in law school proved less problematic for them than the profession. Specialization and megafirms on the scale known today were not characteristic of the practice at mid-twentieth century, and few women were invited to join the existing firms throughout the nation. Utah was no exception. Thus, many women sought employment in public law and law-related fields. One Utah woman graduate of the 1950s, determined to set up a practice, became a sole practitioner in the office where she had been a legal secretary for several years Sharing office space with four other attorneys, she carved a place for herself in the area of motor carrier rights. Keeping abreast of the practice required twelve-hour work days Having made her way on her own in a male profession she is not particularly sympathetic to the demands made by women lawyers today, nor does she subscribe to the distinction made between men and women lawyers. She is a lawyer, not a "woman" lawyer, she insists, conducting her practice on the same terms that have defined the practice for generations.40 She was not unusual in adapting her personal life and career to the demands of a male-defined profession. Unlike professional women of the 1980s, professional and business women a few decades ago sought assimilation rather than accommodation.

Before the outbreak of World War II there were 598 men and 8 women practicing law in Utah. Despite the return of war veterans after 1945, the numbers did not change significantly throughout the next decade (633 men and 10 women by 1950). In 1948, the University of Utah Law School registered 361 students, 9 of them women, the largest enrollment to that date. The number of practicing attorneys in Utah at that time, however, does not reflect this surge of law students. The highest number of admittees to the Utah Bar throughout the 1950s did not exceed 68 in any one year, the number fluctuating from a low of 23 in 1954 when more veterans might have been expected to seek admission.41 The Korean War, although it did not diminish enrollment figures, may have interrupted the move from school to practice. By the end of the decade the number of practicing male attorneys had increased less than a third, to 795,while the number of female attorneys had tripled to 24.42

The social revolution of the 1960s propelled women into the pro-

222 Utah Historical Quarterly

40 Telephone interview with Irene Warr, October 20, 1986 41 Statistical data obtained from U.S Census Reports, Utah State Bar Association, and statistical summaries of the University of Utah 42 Data obtained from the Utah State Bar Association, 645 So. 200 East, Salt Lake City.

fession at an accelerated rate The civil rights movement had initiated a similar effort for women's rights, and the field of law not only offered a direct route toward legal and political power for women but, as a traditionally male bastion, posed a conspicuous challenge for women to test their entry into that field.

In 1970 27 women applied for entrance to the University of Utah College of Law; 6 were accepted. They joined 8 other women to account for just under 4 percent of law students. The next year 13 were accepted out of 60 applicants, and in 1983, a peak year to that date, 49 out of 194 applicants were accepted. In the 1992-93 school year women constituted nearly 42 percent of the total law school enrollment and 54 percent of the entering class.43 At the Brigham Young University College of Law the percentages of women students are slightly less. From 1973,when the school was founded, to 1985 the law school enrolled a total of 1,685 men and 270 women, the women totaling 13 percent of its students Women's representation before 1989 reached a high of 22 percent but dropped dramatically to little more than 15 percent in 1989. Women accounted for 32 percent of the total enrollment for the 1992-93 school year, however, with 30 percent of the entering class being women. 44

In 1990 women made up 12.5 percent of Utah's lawyers (18 percent nationally). Most of them, 79 percent, along with 76.6 of the male lawyers, practiced in Salt Lake County. Ten women were the most in any one firm that year, totaling 8.5 percent of its attorneys.45 By 1992 women accounted for 14.8 percent of the state's attorneys. With more women law students the percentage will undoubtedly rise. Moreover, the fact that "women are disproportionately represented in the top of law school classes," according to one report, would compel law firms to hire more women if they desire the top performing students.46

Despite the increased number of women in the profession, residual psychological and professional barriers range from the subtle to

43 Admissions Office figures for 1990 show that 169 women and 217 men were enrolled in the U College of Law.

44 Admissions Office, J. Reuben Clark School of Law, Brigham Young University, 1986.

45 Utah State Bar Association figures plus additional information obtained from listings in the 1990 Salt Lake City Directory.

46 Judge Michael Zimmerman as quoted in the newsletter of the Women Lawyers of Utah, July 1986, p 3 Women have also proven their capability with the LSAT In 1966 6.5 percent of the students who took the test in Utah were women with a mean score 17 points below men's In 1970, just four years later, 13.3 percent were women, with a mean score 7 points higher than men's (Admissions Office, College of Law, University of Utah.)

Utah Women in Law 223

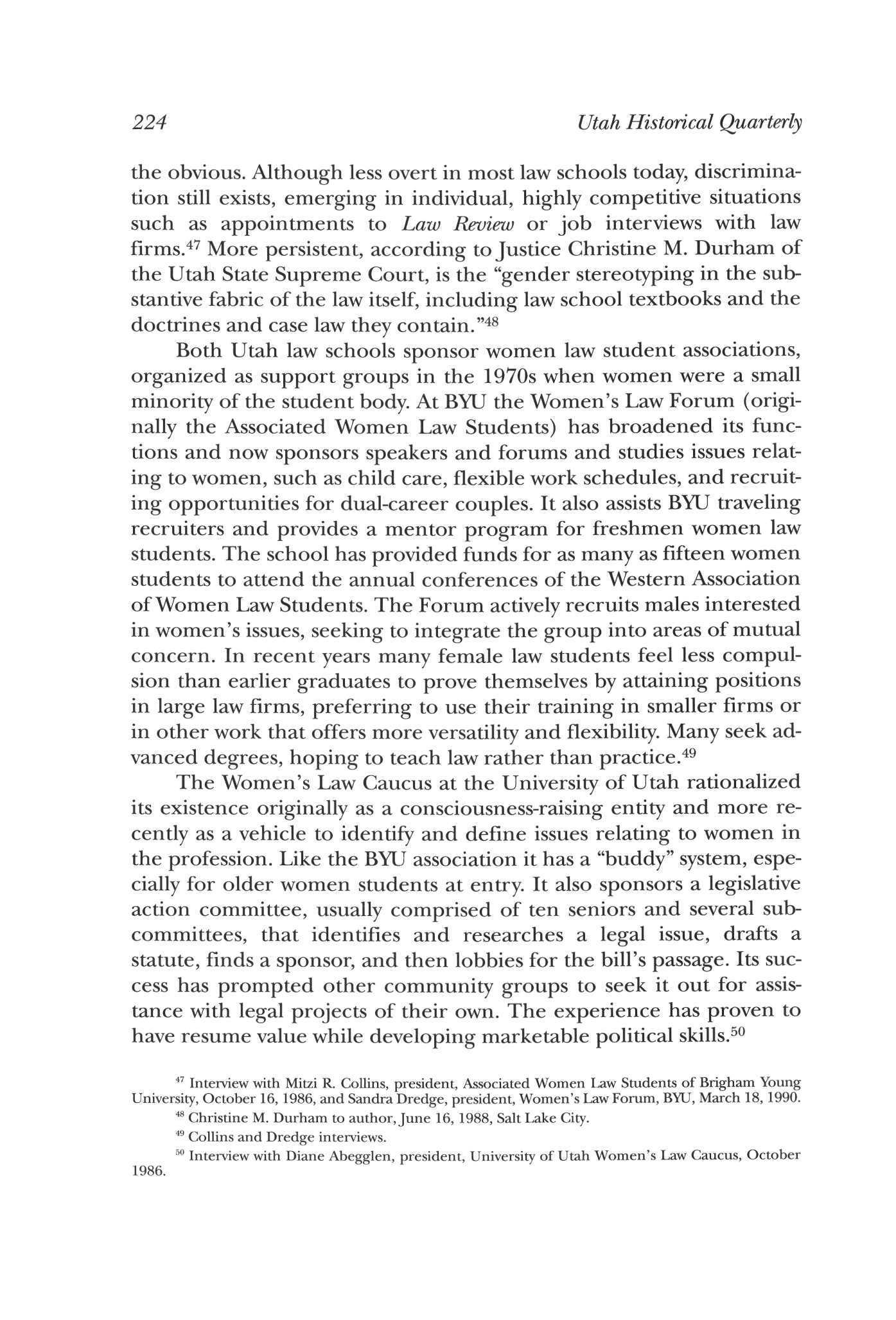

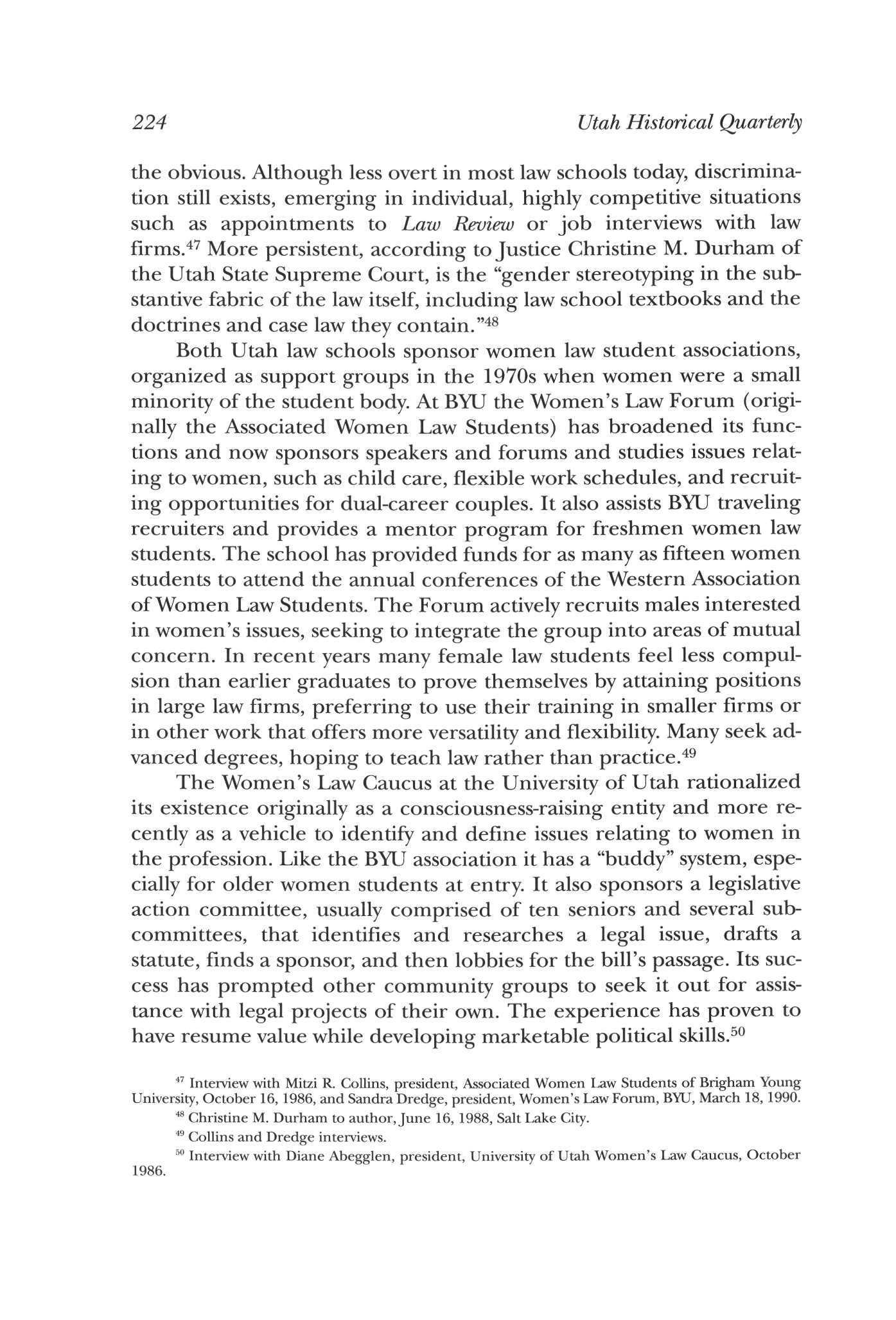

the obvious.Although less overt in most law schools today, discrimination still exists, emerging in individual, highly competitive situations such as appointments to Law Review or job interviews with law firms.47 More persistent, according toJustice Christine M. Durham of the Utah State Supreme Court, is the "gender stereotyping in the substantive fabric of the law itself, including law school textbooks and the doctrines and case law they contain."48

Both Utah law schools sponsor women law student associations, organized as support groups in the 1970s when women were a small minority of the student body. At BYU the Women's Law Forum (originally the Associated Women Law Students) has broadened its functions and now sponsors speakers and forums and studies issues relating to women, such as child care, flexible work schedules, and recruiting opportunities for dual-career couples It also assists BYU traveling recruiters and provides a mentor program for freshmen women law students. The school has provided funds for as many as fifteen women students to attend the annual conferences of the Western Association of Women Law Students The Forum actively recruits males interested in women's issues, seeking to integrate the group into areas of mutual concern. In recent years many female law students feel less compulsion than earlier graduates to prove themselves by attaining positions in large law firms, preferring to use their training in smaller firms or in other work that offers more versatility and flexibility Many seek advanced degrees, hoping to teach law rather than practice.49

The Women's Law Caucus at the University of Utah rationalized its existence originally as a consciousness-raising entity and more recently as a vehicle to identify and define issues relating to women in the profession. Like the BYU association it has a "buddy" system, especially for older women students at entry. It also sponsors a legislative action committee, usually comprised of ten seniors and several subcommittees, that identifies and researches a legal issue, drafts a statute, finds a sponsor, and then lobbies for the bill's passage. Its success has prompted other community groups to seek it out for assistance with legal projects of their own The experience has proven to have resume value while developing marketable political skills.50

47 Interview with Mitzi R. Collins, president, Associated Women Law Students of Brigham Young University, October 16, 1986, and Sandra Dredge, president, Women's Law Forum, BYU, March 18, 1990

48 Christine M Durham to author, June 16, 1988, Salt Lake City

49 Collins and Dredge interviews

50 Interview with Diane Abegglen, president, University of Utah Women's Law Caucus, October 1986

224 Utah Historical Quarterly

The first wave of women graduates in the early 1970s challenged the system by demanding access to the same professional ladder that had always been available to men. That is, rather than making their own way as sole practitioners, practicing with relatives, or using their law training on the fringes of the profession, they sought positions in established law firms, the most viable route to success in the profession One woman's experience indicates how formidable the opposition to women was two decades ago. Since law firms generally hired only male students as law clerks, she supported herself as a teaching assistant until she graduated from the University of Utah College of Law in 1972, specializing in estate planning and tax law After graduation she applied at one of the largest Salt Lake City law firms but was advised there were no openings; however, a week later the firm posted a notice of an opening in her field. Despite pressure from the University of Utah president, a former member of the law school faculty, she was not granted an interview Before she was finally accepted by another Salt Lake City firm (after six interviews and a change of firm policy), she had applied to 200 law firms throughout Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and California without success. In the meantime she had been given a full-time teaching position at the U College of Law, which she gave up tojoin the firm. After nearly three years with the Salt Lake City firm she decided to return to teaching.51 Her entry, along with a few other women, into the ranks of major law firms marked the beginning of a minor revolution. She and her colleagues were at the cutting edge of an ever increasing surge of women into the profession who would not remain on the periphery.

In some respects women law graduates in the late 1960s and early 1970s were more similar to earlier graduates than to those who followed them They often subjugated their personal and family concerns to the requisites of the profession and subscribed to the prevailing standard of legal success: acceptance and eventual partnership in a large, prestigious firm. Proving themselves capable meant adopting the rigorous schedule of accumulating "billable hours" that had become pro forma in the profession and avoiding the female ghettos of family and domestic law. It also meant cultivating the confidence of male attorneys and clients, many of whom initially refused to deal with a woman lawyer. Few sought the support of other female attorneys

Utah Women in Law 225

51 Interview with Constance Lundberg, professor of law, J Reuben Clark School of Law, BYU, October 16, 1986

except for occasional social meetings All had made their own private accommodations to their careers and indicated no need for institutional support. Those who did seek it usually left Utah to practice where such support systems were more accessible.52

A later graduate encountered other problems of adjustment when beginning practice. One of the first twowomen to associate with a large Salt Lake City firm, she found that "acceptance by attorneys in other firms aswell as by clients who were used to dealing with men depended on the continual reassurance to them of her capabilities by senior members of her firm." Some of her former male student colleagues who had been supportive in school became "patronizing in the practice."53 Within a few years, however, much of the initial awkwardness and reservations of both clients and attorneys disappeared as she and other women lawyers became familiar figures in the clerk's office filing papers, in the courtroom trying cases, and in the office counseling clients.

Despite the reluctance of some women in the last century to form their own association when denied admission to the American Bar Association, others have sought the support of professional networking that such associations provide. Originally shut out from the informal social encounters in which male attorneys conduct business, find referrals, and generally make professional connections, women have utilized their own law associations to share information and experiences as well as build solidarity. While the Utah State and County Bar Associations have always extended membership to women, the need for an organization to address specific women's issues in the profession impelled a few women attorneys to organize Women Lawyers of Utah, Inc., in the late 1970s. Like their counterparts nearly a century earlier, they met resistance from those women who were reluctant to be designated specifically as "women lawyers," desiring assimilation into the profession without gender distinction. "For women who had served their professional apprenticeship," one attorney noted, "such an organization meant a step backwards," conjuring up arguments of the "distinctiveness" of women that early entrants into the profession had disclaimed. For many women lawyers, proving their ability at law translated into accepting the structure, procedures, and values of the profession as itwas then constituted.

226 Utah Historical Quarterly

52 ibid 53

1986

Interview with Pat Leith of Van Cott, Bagley, and Cornwall, February 12,

Women Lawyers of Utah, however, provided a collegial support network for women feeling professionally isolated. The organization remained informal until 1978 when Christine Durham and Eleanor Lewis were appointed judges and attended a charter meeting of the National Association of Women Judges where, according to Justice Durham, "we viewed first hand the stimulation, support, and initiative such an association could provide." Despite misgivings from some quarters, the two judges infused life into the Utah organization and within a comparatively short time it proved its value to women in the legal community. Within a decade a third of the women lawyers in Salt Lake County had become active members.54

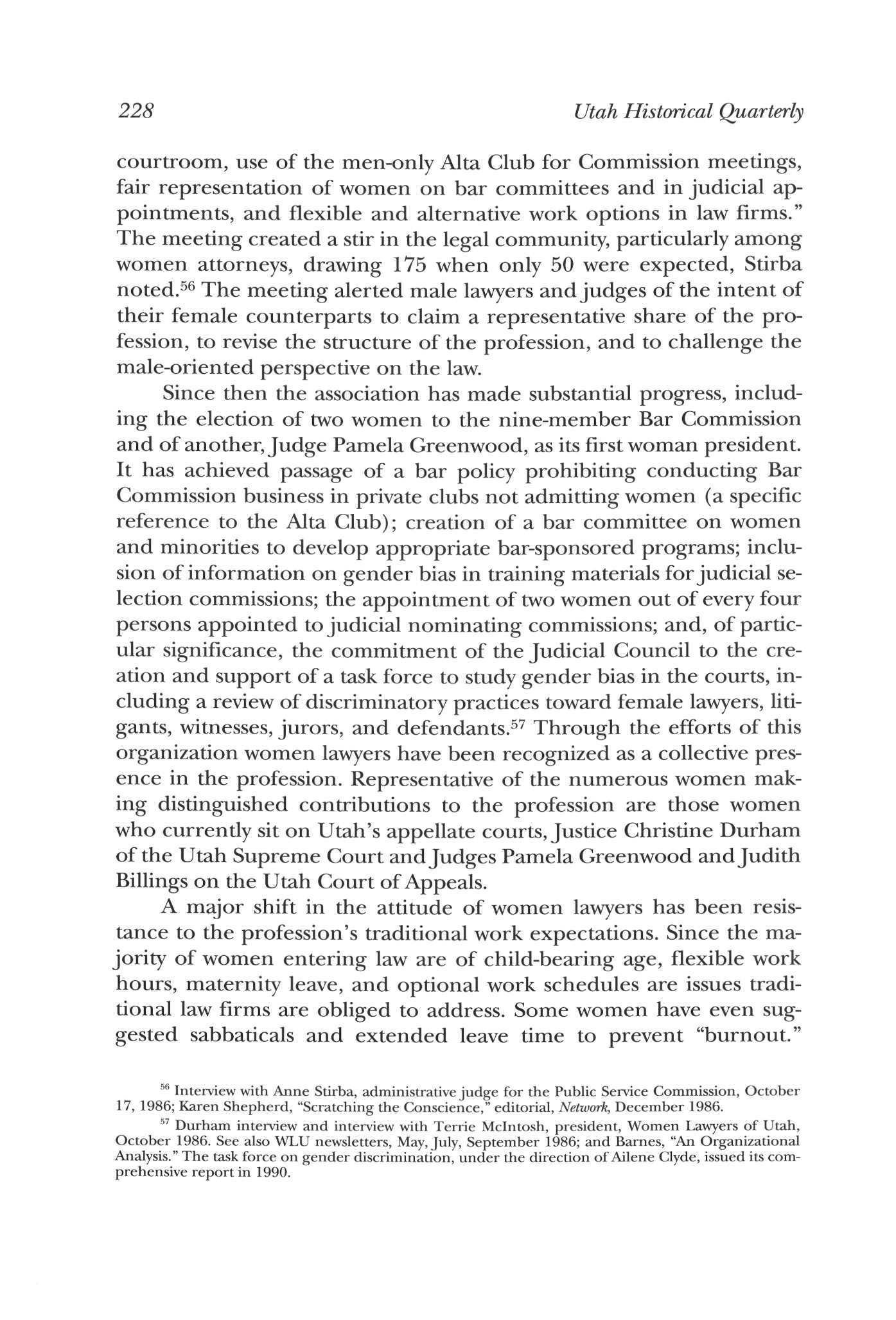

From a hesitant and ambivalent beginning, Durham said, the association coalesced around several specific goals: "to provide support and professional networking to its members, to heighten awareness of women's legal issues and continuing discrimination, and to offer institutional backing for women to gain entry into the power structure of the profession through membership on bar committees and judicial nominating commissions."55 The election of Anne M Stirba in 1984 as the first woman to serve on the Utah State Bar Commission may well have been a test case for the influence of the WLU in support of her candidacy. Though not necessarily an advocate for women's issues, she participated as a member of the commission in a town meeting that turned into a "sensitivity training session" in which Appeals Court Judge Judith Billings and Utah Supreme Court Justice Christine Durham along with then president of WLU, Jane Conard, confronted the male members of the Bar Commission with issues and problems directly related to women lawyers. Out of this meeting, Stirba recalled, came discussion concerning "sexist language in the

Utah Women in Law 227

Bar Commissioner Anne M. Stirba. From Utah Bar Letter, October 1986.

54 Catherine Barnes, "Women Lawyers of Utah, Inc.: An Organizational Analysis," May 19, 1986, typescript copy in possession of author.

55 Interview with Justice Christine Durham, October 1986

courtroom, use of the men-only Alta Club for Commission meetings, fair representation of women on bar committees and in judicial appointments, and flexible and alternative work options in law firms." The meeting created a stir in the legal community, particularly among women attorneys, drawing 175 when only 50 were expected, Stirba noted.56 The meeting alerted male lawyers andjudges of the intent of their female counterparts to claim a representative share of the profession, to revise the structure of the profession, and to challenge the male-oriented perspective on the law.

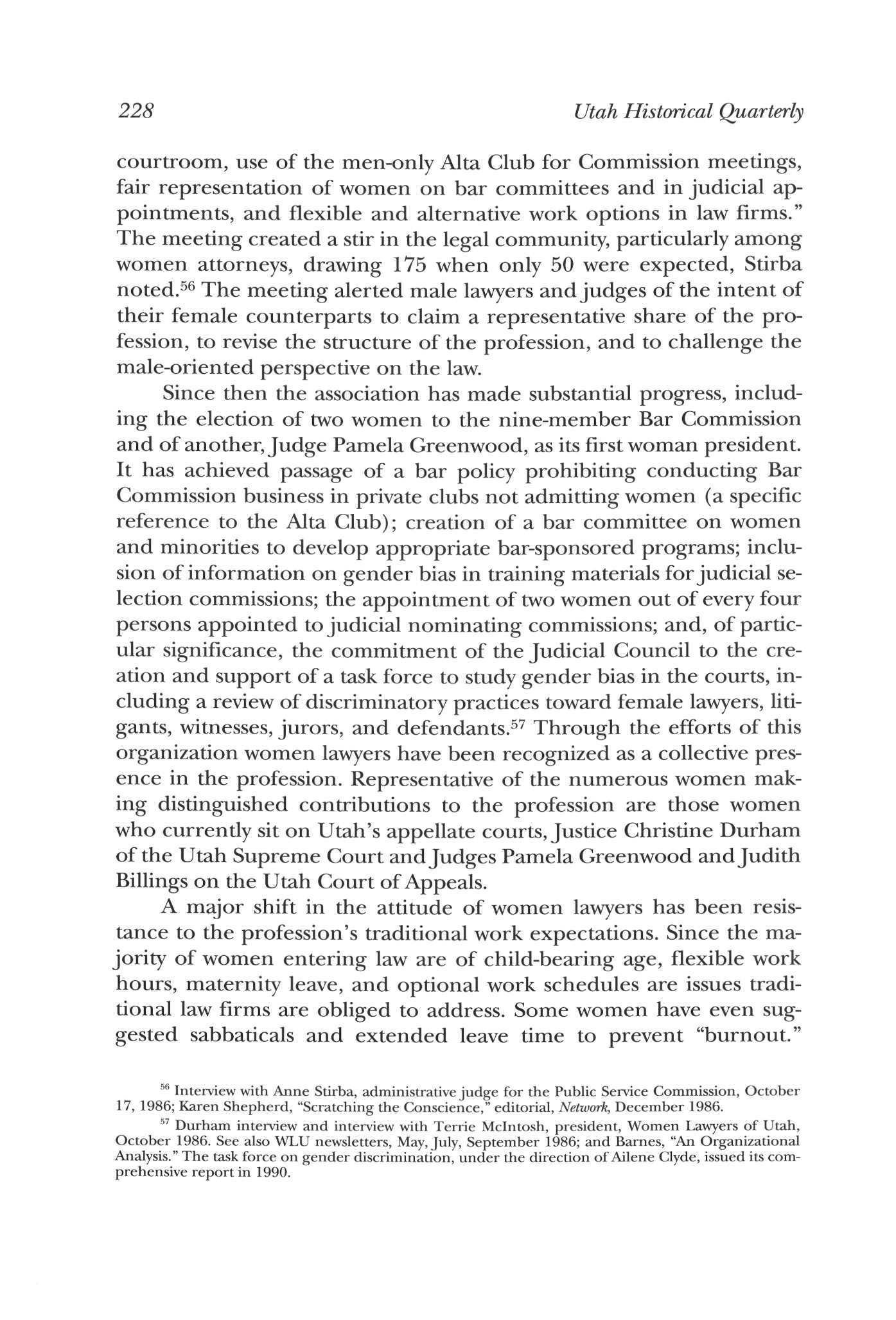

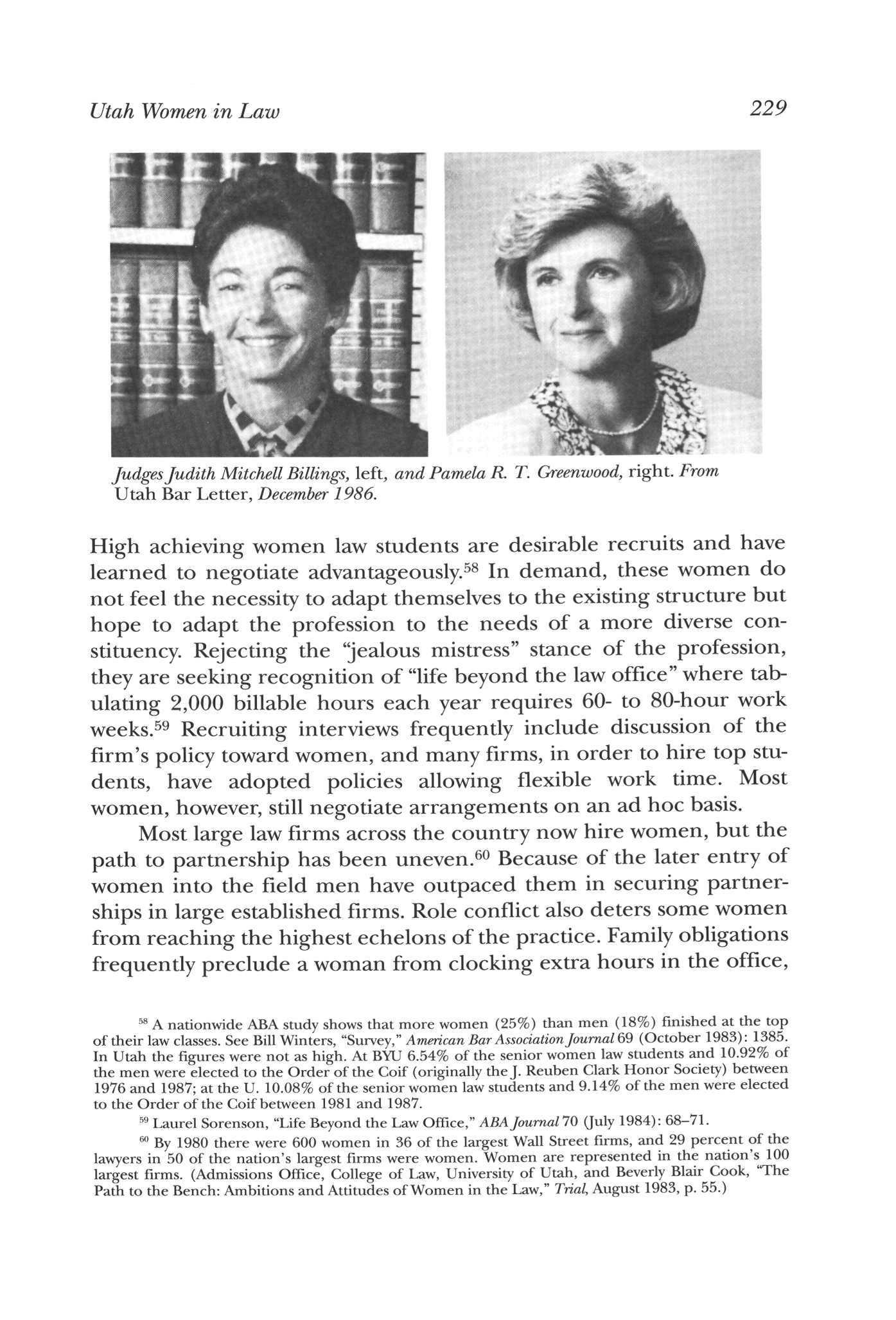

Since then the association has made substantial progress, including the election of two women to the nine-member Bar Commission and of another,Judge Pamela Greenwood, as its first woman president. It has achieved passage of a bar policy prohibiting conducting Bar Commission business in private clubs not admitting women (a specific reference to the Alta Club); creation of a bar committee on women and minorities to develop appropriate bar-sponsored programs; inclusion of information on gender bias in training materials forjudicial selection commissions; the appointment of two women out of every four persons appointed tojudicial nominating commissions; and, of particular significance, the commitment of the Judicial Council to the creation and support of a task force to study gender bias in the courts, including a review of discriminatory practices toward female lawyers, litigants, witnesses,jurors, and defendants.57 Through the efforts of this organization women lawyers have been recognized as a collective presence in the profession. Representative of the numerous women making distinguished contributions to the profession are those women who currently sit on Utah's appellate courts,Justice Christine Durham of the Utah Supreme Court andJudges Pamela Greenwood and Judith Billings on the Utah Court of Appeals. A major shift in the attitude of women lawyers has been resistance to the profession's traditional work expectations. Since the majority of women entering law are of child-bearing age, flexible work hours, maternity leave, and optional work schedules are issues traditional law firms are obliged to address. Some women have even suggested sabbaticals and extended leave time to prevent "burnout."

56 Interview with Anne Stirba, administrative judge for the Public Service Commission, October 17, 1986; Karen Shepherd, "Scratching the Conscience," editorial, Network, December 1986.

D7 Durham interview and interview with Terrie Mcintosh, president, Women Lawyers of Utah, October 1986. See also WLU newsletters, May, July, September 1986; and Barnes, "An Organizational Analysis." The task force on gender discrimination, under the direction of Ailene Clyde, issued its comprehensive report in 1990.

228 Utah Historical Quarterly

High achieving women law students are desirable recruits and have learned to negotiate advantageously.58 In demand, these women do not feel the necessity to adapt themselves to the existing structure but hope to adapt the profession to the needs of a more diverse constituency Rejecting the "jealous mistress" stance of the profession, they are seeking recognition of "life beyond the law office" where tabulating 2,000 billable hours each year requires 60- to 80-hour work weeks.59 Recruiting interviews frequently include discussion of the firm's policy toward women, and many firms, in order to hire top students, have adopted policies allowing flexible work time. Most women, however, still negotiate arrangements on an ad hoc basis.

Most large law firms across the country now hire women, but the path to partnership has been uneven. 60 Because of the later entry of women into the field men have outpaced them in securing partnerships in large established firms. Role conflict also deters some women from reaching the highest echelons of the practice. Family obligations frequently preclude a woman from clocking extra hours in the office,

58 A nationwide ABA study shows that more women (25%) than men (18%) finished at the top of their law classes. See Bill Winters, "Survey," American Bar Association Journal 69 (October 1983): 1385. In Utah the figures were not as high At BYU 6.54% of the senior women law students and 10.92% of the men were elected to the Order of the Coif (originally the J Reuben Clark Honor Society) between 1976 and 1987; at the U 10.08% of the senior women law students and 9.14% of the men were elected to the Order of the Coif between 1981 and 1987

59 Laurel Sorenson, "Life Beyond the Law Office," ABA Journal 70 (July 1984): 68-71

60 By 1980 there were 600 women in 36 of the largest Wall Street firms, and 29 percent of the lawyers in 50 of the nation's largest firms were women Women are represented in the nation's 100 largest firms. (Admissions Office, College of Law, University of Utah, and Beverly Blair Cook, 'Th e Path to the Bench: Ambitions and Attitudes of Women in the Law," Trial, August 1983, p 55.)

Utah Women in Law 229

Judges Judith Mitchell Billings, left, and Pamela R. T. Greenwood, right From Utah Bar Letter, December 1986.

traveling, or assuming other professional responsibilities that usually count toward advancement, a familial commitment not yet expressed as frequently by men. 61 Moreover, for both men and women the competition for legal positions in all areas of the law has intensified as new lawyers have virtually glutted the field. In the 1970s there were 2 lawyers for every 1,000 people nationally, an adequate supply. By 1990 the ratio had shifted to 3.5 lawyers per 1,000. In Utah the statewide ratio in 1990 was lower than the national average, only 2.2 per 1,000, but in Salt Lake County, where most of Utah's attorneys are clustered, there were approximately 4.1 lawyers per 1,000, making competition all the keener.62

For some women the problems of role conflict and the "negative work environment" they sometimes encounter, including less pay, less opportunity for advancement, and less control than their male counterparts enjoy, have caused dissatisfaction and led some of them out of private practice or into other areas of the profession.63 Some women initially opt for public or government service in order to avoid the tensions and pressures of private practice.64 The comparative inability to generate clients and business as easily as men is one reason given for the high percentage of women in salaried positions, reaching 70 percent, according to an ABA survey in the mid-1980s. Only 40 percent of male lawyers were salaried at that time.65 As their incursion into the profession becomes ever more pronounced, women's impact on the procedure and substance of the law becomes even more compelling. Although some would argue that both men and women are trained to view issues only as "lawyers," others do not discount the influence of different social perspectives.

bl Some of these issues are discussed in relationship to Utah professional women, including Judith Billings, in "Was 1992 Really the Year of the Woman?" Salt Lake City, January/February 1993, pp 58-66, 105.

62 Population figures as of January 1991 obtained from the Office of Budget and Planning, Utah State Capitol, Salt Lake City

63 From a survey sponsored by the ABA's Young Lawyers Division, cited by staff director, Ronald Hirsch, at the National Conference of Women's Bar Associations, ABA Midyear Meeting, Baltimore, Maryland, 1986

64 Anne Stirba, first woman membe r of the Utah State Bar Commission, and administrative judg e for the Public Service Commission, is one who deliberately chose to work in public service in order to become more immediately involved in a wider variety of issues She has felt a strong sense of personal responsibility for her work and great flexibility in determining issues and procedures Interview, October 17, 1986

65 Donna Fossum, "A Reflection on Portia," American Bar Association Journal 69 (October 1983): 1391 Another ABA Journal 71 (December 1985): 34-35, article, "Leaving the Law," noted additional causes for dissatisfaction, such as burnout, the adversarial nature of the work, and continuing discrimination Both articles cited the inability to attract clients as a major problem for women Those litigators who do stay report that they relish their work as much as men

230 Utah Historical Quarterly

Both the substance and the practice of the law reflect the presence of women whose perspective on life and morality, law andjustice are not necessarily similar to men's. As a system of regulating standards and relationships the law is ideally gender neutral, but in reality it both reflects and sustains social values and relationships that have, in many areas, been unfavorable to women. The values, insights, and perspectives that an individual interpreter, whether advocate orjudge, brings to bear in the interpretation of law inexorably reflect that individual's judgment and experience. Some have viewed a growing emphasis on conciliation and concern for the personal consequences of resolutions representative of women's approach to arbitration and ruling.66 Studies indicate that women have shown and often prefer to use their skill as facilitators, negotiators, and mediators, which particularly suits a trend toward mediation rather than litigation.67

Moreover, women tend to bring a pattern of personal and social relationships that some psychologists have identified as distinct from that of men. "Women as a group," law professor Kenneth Karst has observed, referring to Carol Gilligan's psychological studies of women, "tend to define themselves and others as members of networks of relationships." This perception of themselves predisposes women to view the consequences of argument, arbitration, and ruling in less easily defined contours than men. As women enter into more policy making decisions, particularly the judiciary, this point of view, Karst believes, will be "progressively infused" into public life.68

This broader female perspective undergirds an approach to law employed by many lawyers and judges today. Time has shown that an earlier feminist platform of equality under the law often translated into inequity for women whose social circumstances often disadvantaged

66 Kenneth L Karst, "Woman's Constitution," Duke Law Journal, June 1984, p 507 The move toward "Alternative Dispute Resolution," which stresses negotiation over litigation, is reflective of this approach

67 Lundberg interview See also an interview with Sue Walton, business manager of Western Arbitration Association, in the Salt Lake Tribune, October 19, 1986, which examines the Alternative Dispute Resolution Utah now has a facility where ADR programs can be implemented and mediation and other related training is available See Hans Q Chamberlain, "Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR)," Utah BarJournal 1 (November 1988): 6-7

68 Karst, "Woman's Constitution," pp 461-62, has applied the psychological theories of Carol Gilligan in In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women's Development (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982) to women's influence on the development and interpretation of law Gilligan, according to Karst, finds that men and women tend to have distinctive views of interpersonal relationships and the meaning of morality Men tend to view human interactions as contractual and hierarchical, while women see the same interactions as part of a continuous nonpositional connection of relationships Karst concludes, "It takes no sophistication to recognize that American law is predominantly a system of the ladder, by the ladder, and for the ladder."

Utah Women in Law 231

them in areas unprotected by the legal system.69 Recognizing that the law as traditionally constructed and administered is limited in its ability to change the institutions and assumptions that formulated it originally,Justice Christine Durham has identified an emerging "feminist jurisprudence" that has provided "an intellectual framework" for implementing the changes that make the law more responsive to all of its constituents. The impact of this legal perspective is already apparent, according to Durham, not only in the classroom, in practice, and in the courts, but "in research and thinking about what happens to women in the world shaped by law, law language, and legal institutions."70

From Myra Bradwell to Sandra Day O'Connor, from Georgiana Snow to Christine Durham, the history of women's attempt to enter a profession in which women have always had a vested interest but no representation shows a steady and determined effort by committed women to broaden their vocational options. A pioneer in removing the barriers to vocational freedom in the nineteenth century, Utah today follows rather than leads the national trend in the degree to which women participate in the legal profession. However, a steadily growing number of Utah women in the field, the quality of their work in the law, and the impact of their perceptions on the law have already begun to reshape the legal profession in Utah

69 Christine Durham, "Of Pedestals and Cages: The Law as Instrument," address delivered to the Conference on Gender and the Family, Brigham Young University, February 7, 1991, p 12

70 Ibid., p 14 One study of female state supreme court justices shows that women justices tend to address a wide variety of gender-related issues as a single feminist issue, including family relationships, property settlement, sex discrimination and harassment, and even medical malpractice The study also shows that they invariably take a "prowoman" position in their decisions, aiming at correcting what they perceive to be a "gender-related societal imbalance," even when their associates oppose an expansion of women's rights See David W Allen and Diane E Wall, "The Behavior of Women State Supreme Court Justices: Are They Tokens or Outsiders? "Justice SystemJournal 12 (February 1987): 232-45 Justice Durham of Utah was included in the study and fits the findings. The study also indicates that women justices seldom take a "centrist" position They are either on the extreme right or the extreme left of criminal justice and economic disputes They are not, in other words, absorbed into the spectrum of positions taken by their male colleagues on each issue

232 Utah Historical Quarterly

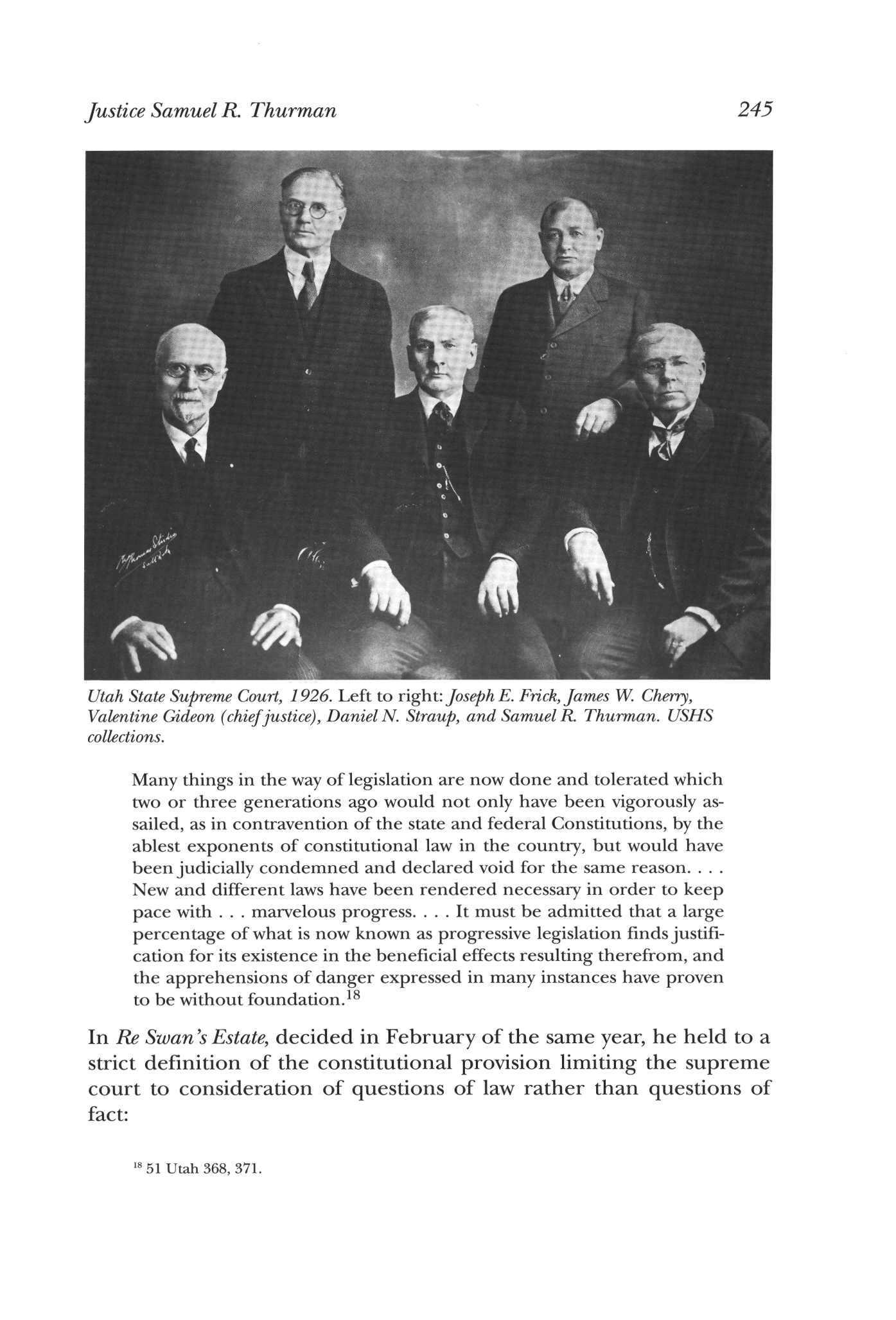

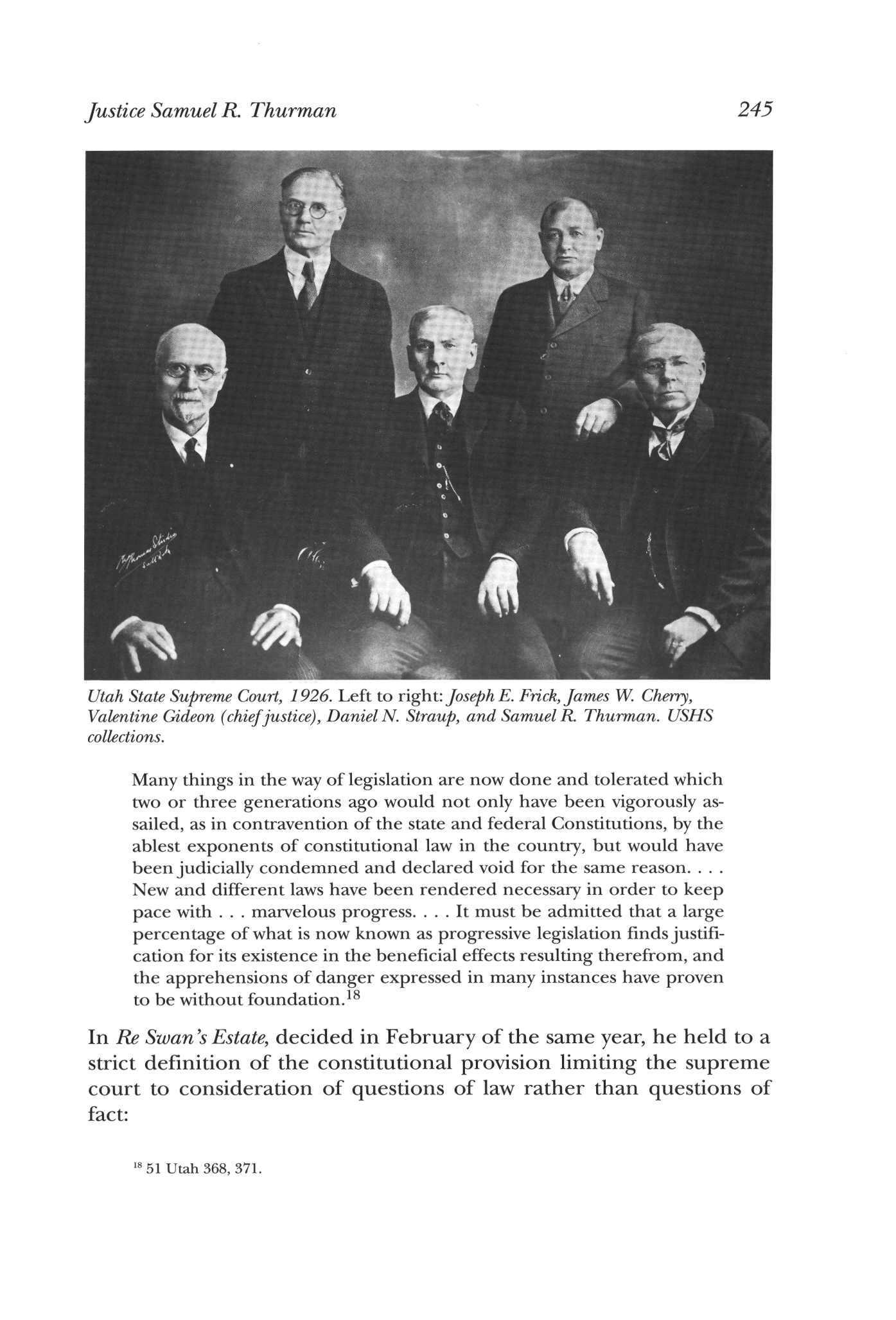

Utah State Supreme Court Justice Samuel R. Thurman

BY JOH N R. ALLEY, JR.

SAMUEL R THURMAN'S 1917 APPOINTMENT TO THE Utah State Supreme Court by Gov. Simon Bamberger was a fitting climax to an active career in Utah politics during its most turbulent years. His appointment, the first of a Mormon, by the state's first non-Mormon governor, to a court that had inherited its initialjustices from its territorial predecessor—a primary instrument of a federal campaign against the Mormon church—represented the growing reconciliation between

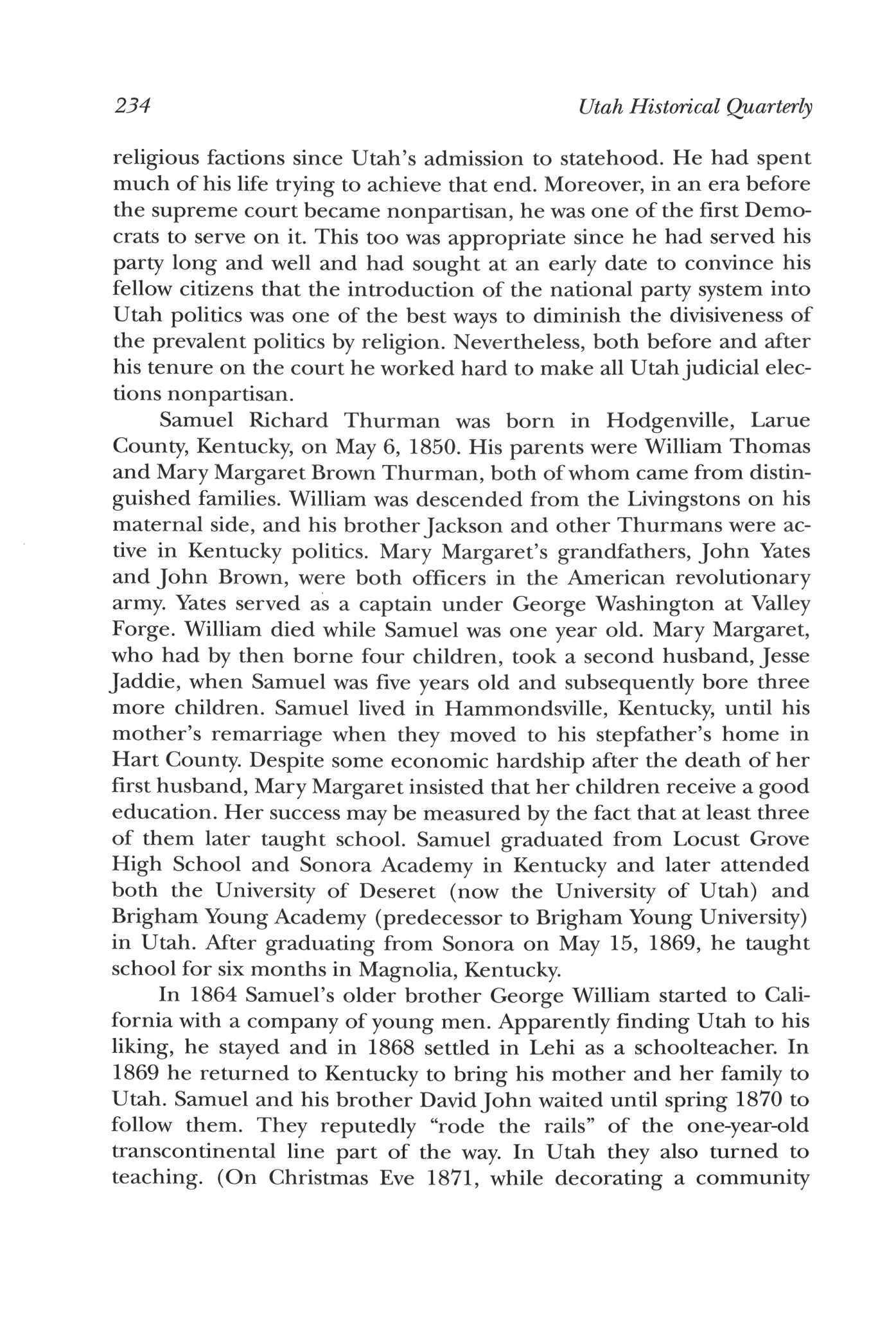

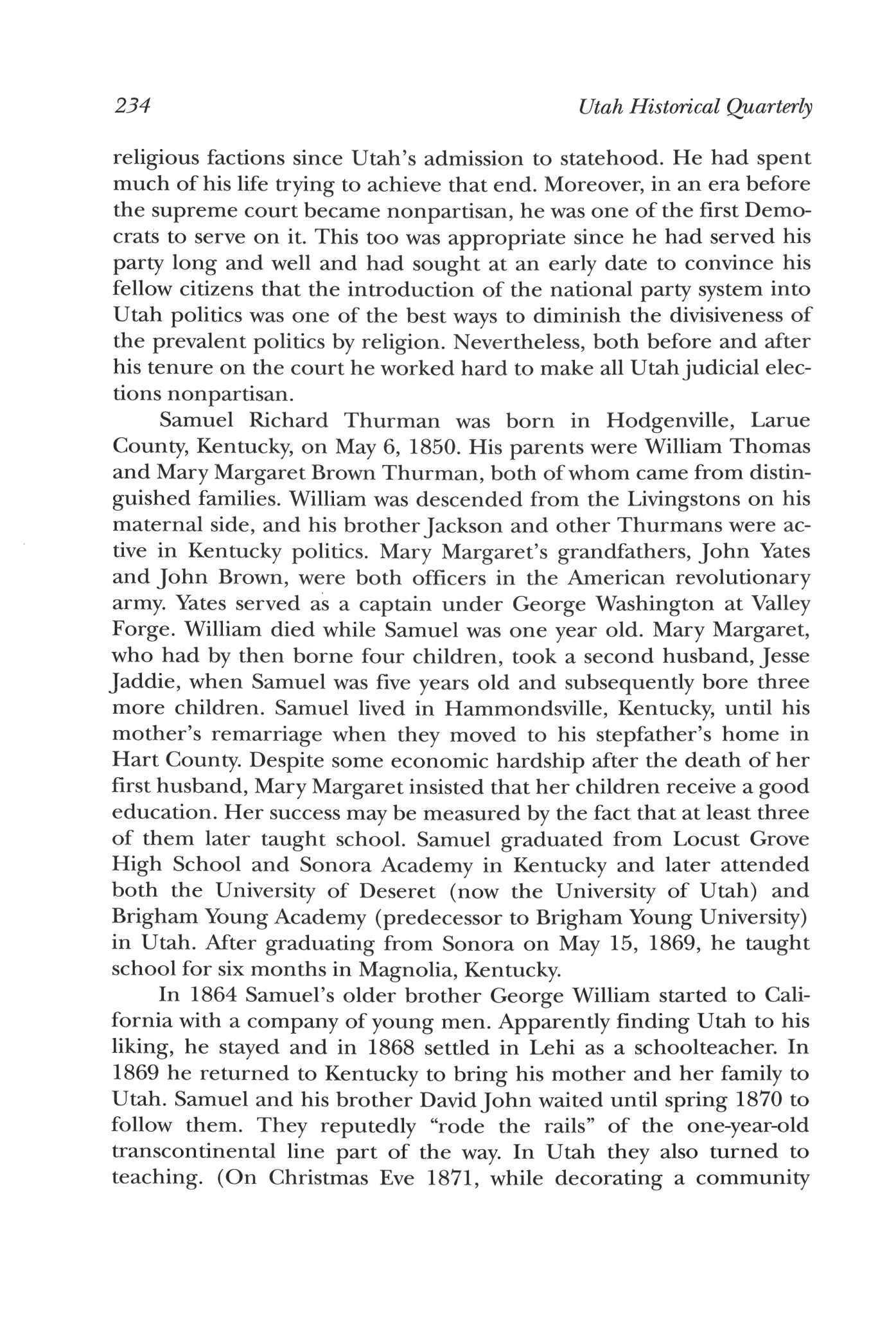

Samuel R. Thurman. USHS collections.

Dr Alley is editor of Utah State University Press

Samuel R. Thurman. USHS collections.

Dr Alley is editor of Utah State University Press

religious factions since Utah's admission to statehood He had spent much of his life trying to achieve that end. Moreover, in an era before the supreme court became nonpartisan, he was one of the first Democrats to serve on it. This too was appropriate since he had served his party long and well and had sought at an early date to convince his fellow citizens that the introduction of the national party system into Utah politics was one of the best ways to diminish the divisiveness of the prevalent politics by religion Nevertheless, both before and after his tenure on the court he worked hard to make all Utahjudicial elections nonpartisan.

Samuel Richard Thurman was born in Hodgenville, Larue County, Kentucky, on May 6, 1850. His parents were William Thomas and Mary Margaret Brown Thurman, both of whom came from distinguished families. William was descended from the Livingstons on his maternal side, and his brother Jackson and other Thurmans were active in Kentucky politics. Mary Margaret's grandfathers, John Yates and John Brown, were both officers in the American revolutionary army Yates served as a captain under George Washington at Valley Forge. William died while Samuel was one year old. Mary Margaret, who had by then borne four children, took a second husband, Jesse Jaddie, when Samuel was five years old and subsequently bore three more children. Samuel lived in Hammondsville, Kentucky, until his mother's remarriage when they moved to his stepfather's home in Hart County. Despite some economic hardship after the death of her first husband, Mary Margaret insisted that her children receive a good education. Her success may be measured by the fact that at least three of them later taught school. Samuel graduated from Locust Grove High School and Sonora Academy in Kentucky and later attended both the University of Deseret (now the University of Utah) and Brigham Young Academy (predecessor to Brigham Young University) in Utah. After graduating from Sonora on May 15, 1869, he taught school for six months in Magnolia, Kentucky

In 1864 Samuel's older brother George William started to California with a company of young men Apparently finding Utah to his liking, he stayed and in 1868 settled in Lehi as a schoolteacher. In 1869 he returned to Kentucky to bring his mother and her family to Utah. Samuel and his brother DavidJohn waited until spring 1870 to follow them. They reputedly "rode the rails" of the one-year-old transcontinental line part of the way. In Utah they also turned to teaching. (On Christmas Eve 1871, while decorating a community

234 Utah Historical Quarterly

Christmas tree, George was shot and killed by a rowdy student whom he had previously chastised.) During the next eight years Samuel taught school and used his free time to study law In February 1871 he joined the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Samuel married Isabella Karren of Lehi on May 4, 1872. They would have eight children: Richard Bertram, born November 7, 1873; May Belle, May 18, 1876; Mary Margaret, November 21, 1878; Lydia Catherine, May 2, 1882; William Thomas, April 21, 1885; Samuel David,July 25, 1887; Victor Emanuel, May 6, 1890; and Allen Grover, February 6, 1893.1

Meanwhile, Samuel's study of the law also bore fruit when in 1875 at the age of twenty-four he was appointed city attorney for Lehi. He did not remember his introduction to trial law as auspicious (although he was city attorney he would not be admitted to the bar until 1878 or 1879). He "conceived the brilliant idea" of trying his first two cases together. In the trade of a calf one man was accused of swindling another, who in turn was accused of assaulting the alleged swindler Although the jury was instructed that it was up to them to decide whether the second party, who admitted the assault, was sufficiently provoked by the swindle, they not only found the first party not guilty of the swindle, thereby removing the possible provocation, but also, having considered the assault first, claimed there was enough reasonable doubt about whether the second party had been provoked to find him not guilty as well. Samuel drolly attributed the verdicts to "the efficiency and flexibility of the doctrine of reasonable doubt."2

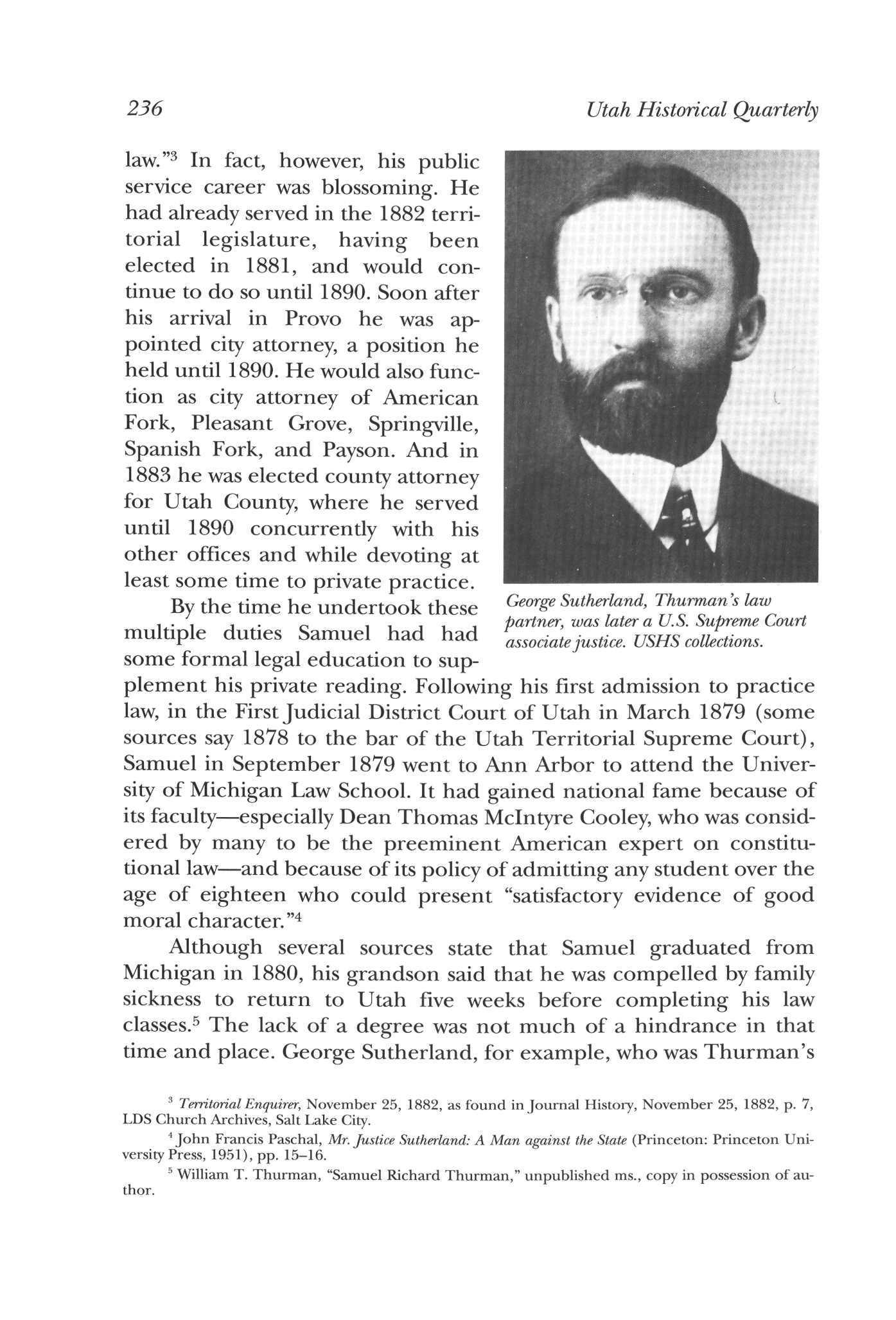

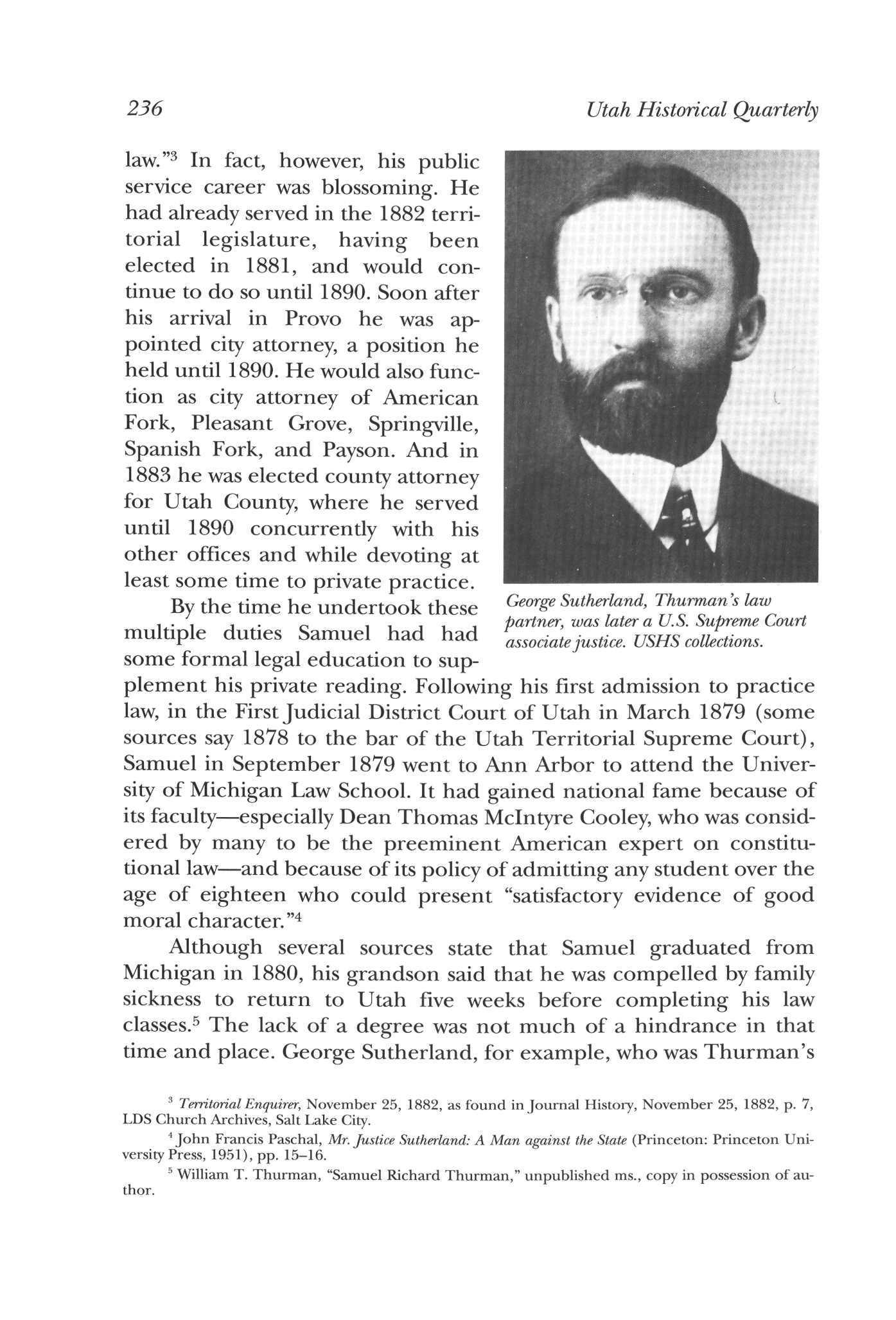

Thurman also served as auditor and alderman of Lehi. In 1877, while holding the latter position, he became mayor when his predecessor resigned. This temporary role lasted only until 1879, but he was elected mayor in his own right in 1881. In November 1882, three months before the next city election, he resigned in order to move to Provo and "devote hereafter his whole time to the practice of the

1 Information regarding Samuel Thurman's children is from Family Group Records for Samuel Richard Thurman, Genealogical Library of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City Short biographies of Thurman can be found in J Cecil Alter, Utah, the Storied Domain: A Documentary History of Utah's Eventful Career (Chicago: American Historical Society, 1932), 2:52-54; Frank Esshom, Pioneers and Prominent Men of Utah (reprint ed., Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1966), p 1213; Portrait, Genealogical, and Biographical Record of the State of Utah (Chicago: National Historical Record, 1902), pp. 411-12; Press Club of Salt Lake, Men of Affairs in the State of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1914), p. 174; Ralph B Simmons, Utah's Distinguished Personalities (Salt Lake City, 1933), 1:206; Noble Warrum, Utah Since Statehood: Historical and Biographical (Chicago: S.J Clarke Publishing Company, 1919), 2:96-100

2 Samuel R Thurman, "Reminiscences of a Barrister," History of the Bench and Bar of Utah (Salt Lake City, 1913), pp 73-74

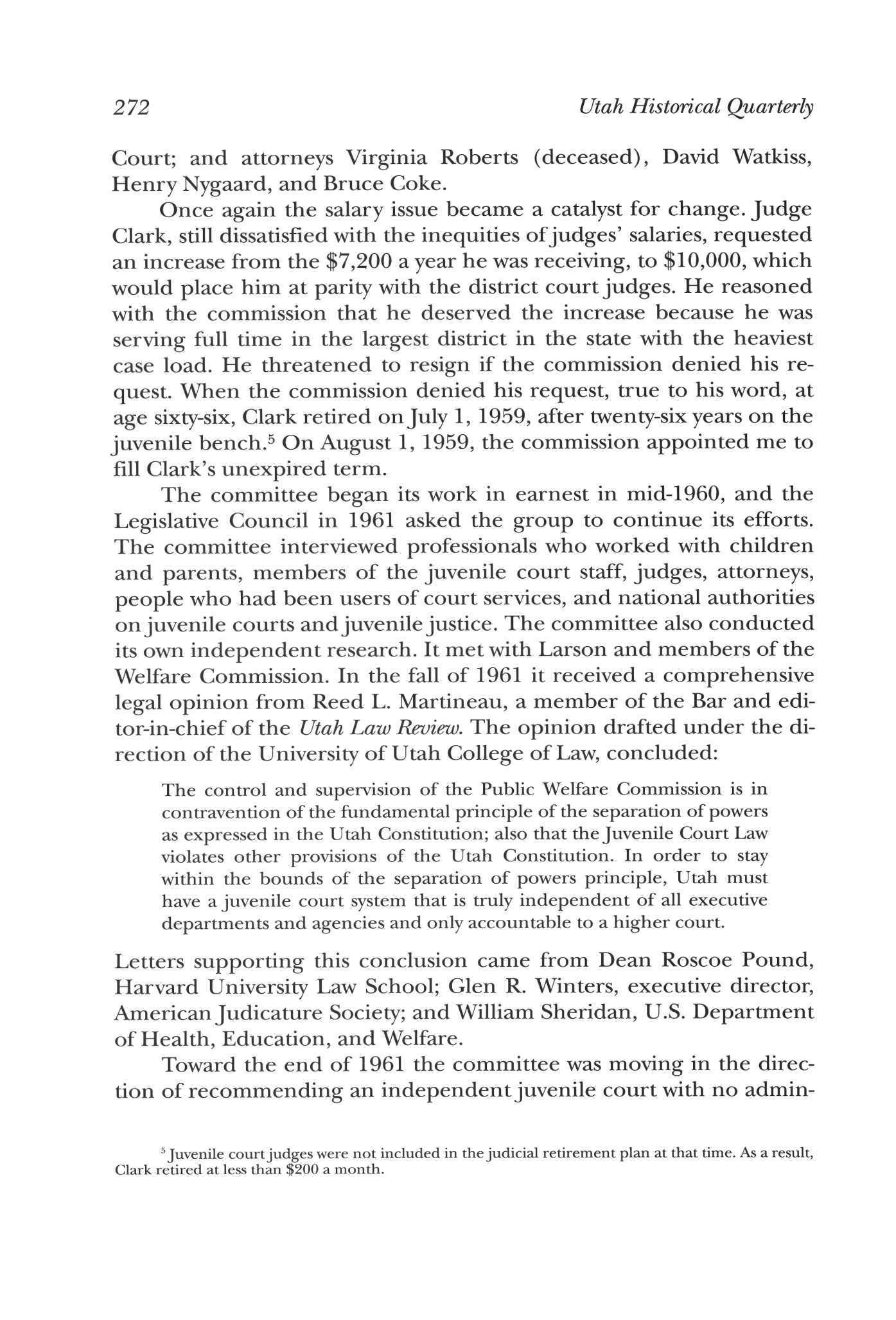

Justice Samuel R. Thurman 235