2 H H W CO CD O r d S M 05 to d td

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAX J EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

KENNETH L CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1995

JANICE P DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M. GODFREY, Logan, 1994

JOEL C JANETSKI, Provo, 1994

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1995

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

RICHARD W SADLER, Ogden, 1994

GENE A SESSIONS, Ogden, 1995

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801)533-3500 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 x/\ or 3 x/i inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor. Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society.

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICAL ClUARTERLY Contents WINTER 1994 / VOLUME 62 / NUMBER 1 IN THIS ISSUE 3 A GAUGE OF THE TIMES: ENSIGN PEAK IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY RONALD W. WALKER 4 THE WASTERS AND DESTROYERS: COMMUNITY-SPONSORED PREDATOR CONTROL IN EARLY UTAH TERRITORY VICTOR SORENSEN 26 "RAGS! RAGS!! RAGS!!!": BEGINNINGS OF THE PAPER INDUSTRY IN THE SALT LAKE VALLEY, 1849-58 RICHARD SAUNDERS 42 JAKOB BRAND'S REGISTER OF DUTCHTOWN, UTAH'S LOST GERMAN MINING COLONY WILMA B. N. TILBY 53 JOHN STEELE: MEDICINE MAN, MAGICIAN, MORMON PATRIARCH KERRY WILLIAM BATE 71 BOOKREVIEWS 91 BOOKNOTICES 99 THE COVER Jakob Brandfamily; upper half, 1-r: Jules, Jake, Katherina, Emit, Gottlieb, Anna; lower half, 1-r: Elisabetha, Matilda, Jakob, Charly, Martha. Courtesy of Wilma B. N. Tilby. © Copyright 1994 Utah State Historical Society

UT iJk( mmJnL

E. BUSH, JR.

DONALD K GRAYSON The Desert'sPast: ANaturalPrehistoryof the Great Basin DAVID RHODE Books reviewed 91 D MICHAEL QUINN, ed The New MormonHistory:RevisionistEssays onthe Past WAYNE K HINTON 92 JILL MULVAY DERR, JANATH RUSSELL CANNON, and MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER. WomenofCovenant: TheStoryof Relief Society REBECCA VAN DYKE 93 GARTH L MANGUM and BRUCE D BLUMELL TheMormons' Waron Poverty: AHistoryofLDSWelfare, 1830-1990 MARCELLUS S SNOW 95

HealthandMedicine amongthe Latter-daySaints: Science, Sense,and Scripture HERBERT Z. LUND, JR. 96 ROBERT M UTLEY TheLanceandthe Shield: TheLifeandTimesofSitting Bull DO N R MATHIS 98

LESTER

In this issue

Ensign Peak, the subject of the first article in this issue, is one of several prominences in the hills north of the State Capitol. Its shape, though distinctive, hardly qualifies as a peak, and several of its neighbors exceed its modest 5,414-foot height Nevertheless, Ensign Peak has been the scene of more history—some of it disputed—and the object of more planning, promotion, and preservation activity than most of the majestic peaks of the Wasatch range

Evidently, the nascent settlement overlooked by Ensign Peak echoed with the howling of wolves in the early years. Organized hunts in the Salt Lake and Cache valleys attempted to eliminate wolves and other "wasters and destroyers." As the second article points out, these mass shootings of wildlife may offend late twentieth-century sensibilities, but today's more than adequate food supply was bound to change perspectives

With self-sufficiency the "politically correct" watchword in pioneer Utah's temporal affairs, attempts to make paper for printing newspapers, announcements, and other communications come as no surprise. Paper was a costly import and its deliveries were erratic, the third article notes, but the first locally made paper embarrassed the craftsmen who had to print on it.

German immigrants have carved a major place for themselves in Utah history, and much has been written about them. But even a welltraveled road may have unexplored branches The fourth article presents an intriguing story of German settlers in Dutchtown near Eureka in the Tintic Mining District. Jakob Brand's notebook opened a new area of research that ultimately helped the author understand the dynamics of community life in Juab County and the interaction of German settlers there with those living in Cache County and other locales.

The final piece recounts the fascinating life of John Steele, a medical practitioner in Toquerville who struggled unsuccessfully to find marital bliss Renowned as a bonesetter and herbalist, Steele also dabbled in astrology and witching A legend in his own time, he remains larger than life almost a century later.

John Steele. Courtesy of Genevieve S.

Jensen.

John Steele. Courtesy of Genevieve S.

Jensen.

A Gauge of the Times: Ensign Peak in the Twentieth Century

BY RONALD W WALKER

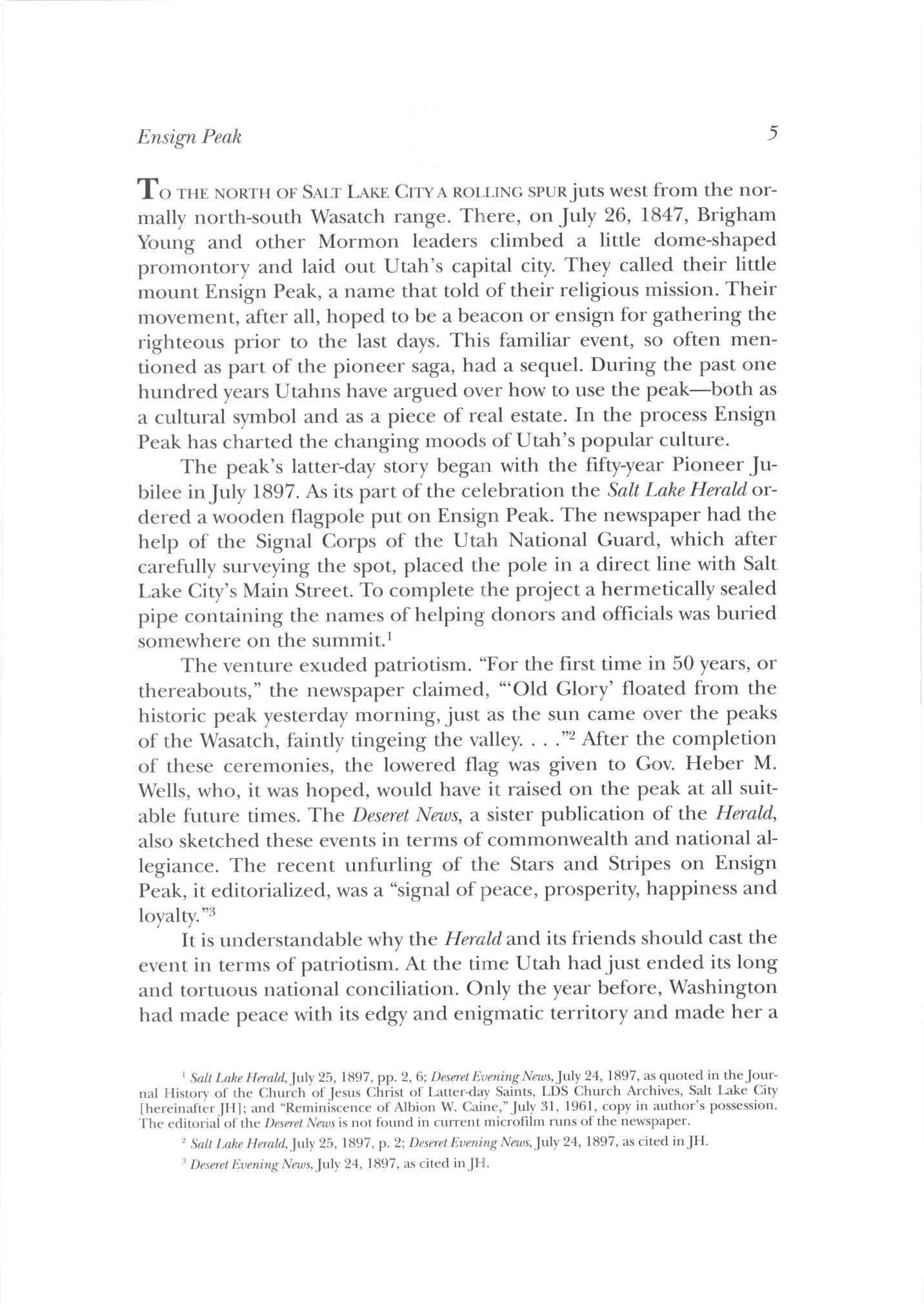

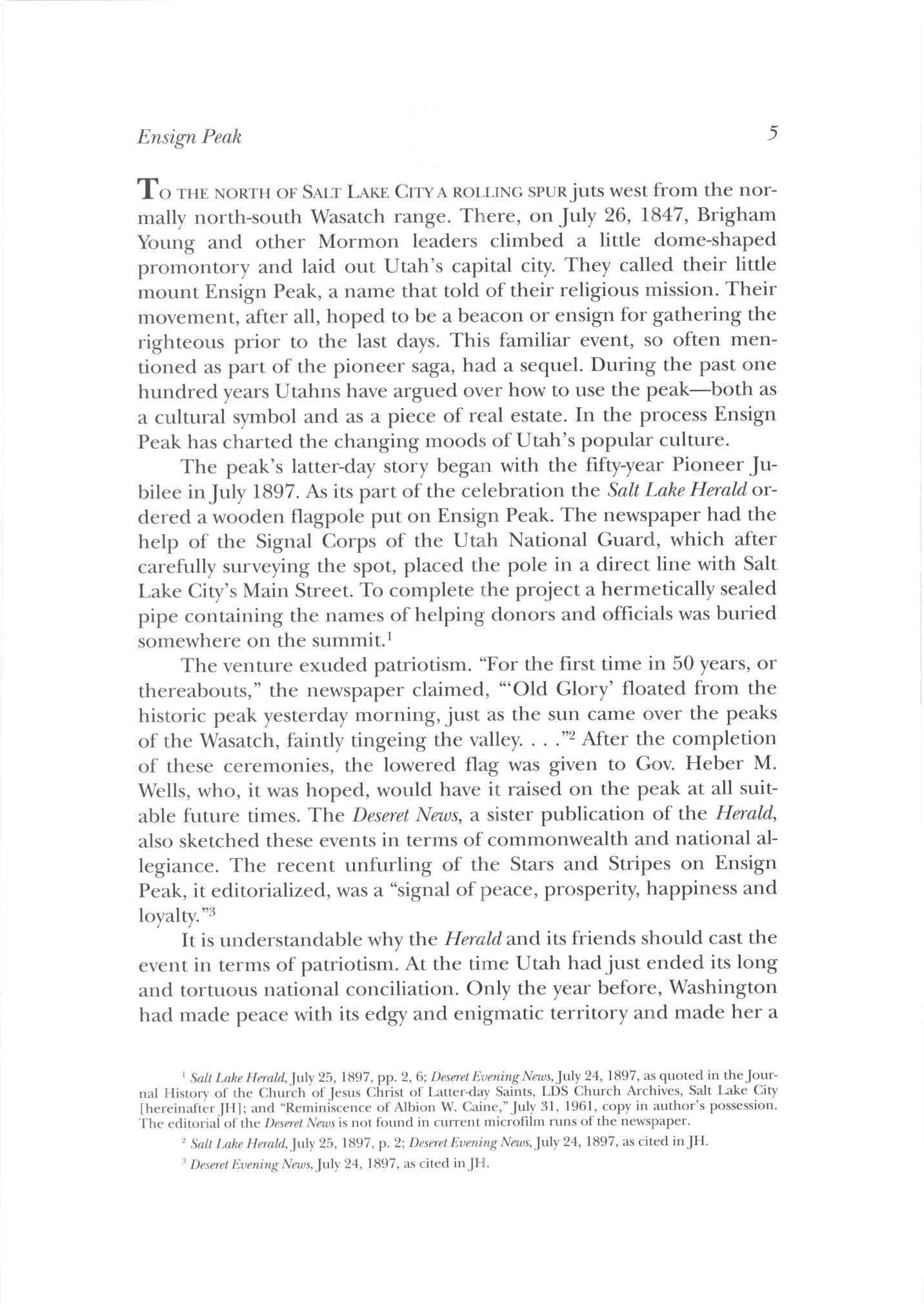

Thefamiliar dome shape ofEnsign Peak rises to the left of the State Capitol in this 1964 U.S. Bureau of Reclamation photograph in USHS collections.

Dr Walker is professor of history and senior research associate, Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History, Brigham Young University

BY RONALD W WALKER

Thefamiliar dome shape ofEnsign Peak rises to the left of the State Capitol in this 1964 U.S. Bureau of Reclamation photograph in USHS collections.

Dr Walker is professor of history and senior research associate, Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History, Brigham Young University

Xo THE NORTH OF SALT LAKE CITY A ROLLING SPUR juts west from the normally north-south Wasatch range. There, on July 26, 1847, Brigham Young and other Mormon leaders climbed a little dome-shaped promontory and laid out Utah's capital city. They called their little mount Ensign Peak, a name that told of their religious mission. Their movement, after all, hoped to be a beacon or ensign for gathering the righteous prior to the last days. This familiar event, so often mentioned as part of the pioneer saga, had a sequel. During the past one hundred years Utahns have argued over how to use the peak—both as a cultural symbol and as a piece of real estate. In the process Ensign Peak has charted the changing moods of Utah's popular culture

The peak's latter-day story began with the fifty-year Pioneer Jubilee inJuly 1897 As its part of the celebration the Salt LakeHerald ordered a wooden flagpole put on Ensign Peak The newspaper had the help of the Signal Corps of the Utah National Guard, which after carefully surveying the spot, placed the pole in a direct line with Salt Lake City's Main Street. To complete the project a hermetically sealed pipe containing the names of helping donors and officials was buried somewhere on the summit.1

The venture exuded patriotism. "For the first time in 50 years, or thereabouts," the newspaper claimed, "'Old Glory' floated from the historic peak yesterday morning, just as the sun came over the peaks of the Wasatch, faintly tingeing the valley. . . ."2 After the completion of these ceremonies, the lowered flag was given to Gov. Heber M. Wells, who, it was hoped, would have it raised on the peak at all suitable future times. The Deseret News, a sister publication of the Herald, also sketched these events in terms of commonwealth and national allegiance The recent unfurling of the Stars and Stripes on Ensign Peak, it editorialized, was a "signal of peace, prosperity, happiness and loyalty."3

It is understandable why the Herald and its friends should cast the event in terms of patriotism At the time Utah had just ended its long and tortuous national conciliation Only the year before, Washington had made peace with its edgy and enigmatic territory and made her a

1 Salt Lake Herald, July 25, 1897, pp 2, 6; Deseret Evening News, July 24, 1897, as quoted in the Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City [hereinafter JH]; and "Reminiscence of Albion W. Caine,"July 31, 1961, copy in author's possession. The editorial of the Deseret News is not found in current microfilm runs of the newspaper

2 Salt Lake Herald, July 25, 1897, p 2; Deseret Evening News, July 24, 1897, as cited inJH

:1 Deseret Evening News, July 24, 1897, as cited in JH

EnsignPeak5

state For their part, Utahns were eager to show their appreciation— and their Americanism Their ancestors had been driven from New York, Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois and as a result had entered the Great Basin with badly splintered loyalties These early pioneers were more willing to affirm the ideals of America than the conduct of those Americans who had tormented them But such a distinction was lost on their children and grandchildren. The new generation wished to be known as loyal citizens—without qualification.

For these Utahns Ensign Peak was a patriotic symbol According to the traditions that they had inherited and wished to foster, Brigham Young's first party had raised the American banner during itsJuly 26, 1847, reconnaissance. This episode, so the story went, was the first American flag-raising in the Great Basin. The Mormons had thereby wrested Utah's soil from Mexican control and furthered the manifest destiny of the rapidly expanding United States. The Mormons, in short, had been loyal American empire builders.

These ideas—repeatedly put forward during the first decades of the twentieth century by boosters of Utah's past and future—were rejected with equal force by those disputing such claims This first "cultural war" over the meaning of Ensign Peak had its roots in the religious and political conflict of the time The turn-of-the-century Salt LakeTribune, ever the curmudgeon to Mormon views, enthusiastically took on the issue In 1908 the newspaper noted the eagerness of its rival, the LDS-owned Deseret News, to accept uncritically the supposed Brigham Young, July 26, 1847, flag-raising. The only banner waved that day, according to the Tribune, was a "yellow bandanna decorated with black spots," which was attached to Willard Richards's walking cane. "That was the 'flag' that was first hoisted by the Mormon 'pioneers' in this valley," the Tribune claimed. To support its view the newspaper quoted, without citation, no less a light than Heber C. Kimball.4

A black spotted, yellow bandanna, of course, was a considerable come-down from an empire-claiming, patriotic American flag. Two years later the Tribune returned to the refrain. The newspaper quoted an address of William C. A. Smoot, once a twenty-year-old member of the first pioneer party, made at a gathering of the anti-Mormon American party Smoot challenged the idea that prior to the coming of the Saints the Salt Lake Valley had been a barren desert He further challenged Mormon pulpit oratory by agreeing with the Tribune's earlier

6Utah HistoricalQuarterly

4 Salt Lake Tribune, November 19, 1908, p. 4.

account of a boyishly waved, non-Arnerican-flag, a yellow bandanna, which at the time was meant to prefigure a scripture-fulfilling ensign, later to be lifted.5

By denying one of the increasingly accepted patriotic icons of the community, Smoot received the heavy scorn of the SaltLakeHeraldRepublican, often an ally of the Deseret News. The newspaper unfairly charged that Smoot was an "intense Mormon hater," who enjoyed "detailing the bitterest falsehood and railings against his former associates." He wished, the Herald-Republican continued, to rob the first settlers of their deserving "mead of praise." To be sure, Smoot had been an LDS bishop, a position he resigned after a dispute with church leaders. But his words in the intervening years had not been shrill—not at least until the Herald-Republicans editorial called them forth.6

The Mormons themselves were not united on the subject. Apostle Matthias F. Cowley upheld the traditional view. His biography of Wilford Woodruff, a member of the first Ensign Peak party, contained a paragraph that would muddle other Mormon accounts for the next several decades:

On Monday the 26th [1847], President Young and several brethren ascended the summit of a mountain on the north which they named Ensign Peak, a name it has borne ever since Elder Woodruff was the first to gain the summit of the peak Here they unfurled the American flag, the Ensign of Liberty to the world. It will be remembered that the country then occupied by the Saints was Mexican soil, and was being taken possession of by the Mormon Battalion and pioneers as a future great commonwealth to the credit and honor of the United States.7

5 Salt Lake Tribune, March 18, 1910, p 2

6 Salt Lake Herald-Republican, March 23, 1910, sec 1, p 4; W C A Smoot, "Bishop Smoot's Trenchant Reply," Salt Lake Tribune, March 27, 1910, p 12 Smoot may have lost his LDS moorings, but candor in this case seems to have been mistaken for enmity. For further information on the man see Salt Lake Evening Telegram, July 26, 1913, p 6, and "William Cockhorn Adkinson Smoot," in Our Pioneer Heritage, 20 vols (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1957-77) 2:557-58

7 Matthias F. Cowley, Wilford Woodruff: History ofHis Life and Labors (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1909), p 316

EnsignPeak7

Close-up ofEnsign Peak, ca. 1940, shows its distinctive shape. USHS collections.

Perhaps Cowley had data that no one else before or later has unearthed, and events took place just as he wrote. But LDS historian B. H Roberts, writing a decade later, wanted cold, hard, validating facts and could find none In an article entitled "The 'Mormons' and the United States Flag," Roberts complained that if the Brigham Young party had raised the American flag an on-the-spot diary surely would have recorded the event. Roberts concluded that the ensign of Ensign Peak was simply a literary metaphor for the Mormons' Gospel mission and bore no relationship to any flag whatsoever.8

Less than ten years later Roberts's voice was rising. With LDS spread-eagle oratory and faith-promoting sermons continuing, the historian was clearly vexed. Treating the Ensign Peak episode once more in his magisterial, six-volume survey of LDS history, his words became sharp The peak had neither timber nor brush to mount a standard, Roberts argued, and no evidence confirmed the nine men had carried with them a flag. He concluded that the proposition was "utterly impossible" and "unwarranted," a "pious fiction [that] lives on and on by the force of parrot-like iteration and re-iteration adnauseam.''9

Roberts was not alone in insisting on what he believed was historical fact Assistant LDS historian Andrew Jenson, in turn, was rankled by a detailed description of the supposed pioneer flag-raising, which in one retelling had great specificity. According to this account, three pioneers were dispatched to the peak at 6 A.M. on July 24, 1847—before Young had even arrived in the valley—to claim the Great Basin from Mexico Their supposed proclamation had a chiseled-in-marble quality.

In raising this flag upon this mountain, which we name Ensign peak, we take possession of this valley and of all the mountains, lakes, rivers, forests and deserts of this territory in the name of the United States of America and proclaim this land to be the American territory.10

Jenson wanted proof for such an extraordinary statement, with its "startling details." It could not be accepted from memory alone, he insisted, because of "the abundant documentary proofs" to the contrary. To this complaint he offered a postscript. "We historians have

8 B H Roberts, "The 'Mormons' and the United States Flag," Improvement Era 25 (November 1921): 5 Also see B H Roberts, "The Oration," In Honor of the Pioneers (Salt Lake City: Bureau of Information, 1921), pp 24-25

9 B H Roberts, A Comprehensive History of The Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930), 3:271-79

10 AndrewJenson, "Historian Gives Account of Ensign Peak," Salt Lake Tribune, August 1, 1931, p. 4.

8Utah HistoricalQuarterly

done our best to prove the correctness of such tales," he admitted. "We have failed and have long ago concluded that no such event took place. ... In the interest of true history, let us stick to facts and not assert things that we have to refute later."11

But the tide was irresistible. Despite the objection of Mormon historians the fabled version of the Ensign Peak flag raising continued to be told as far away as Georgia and by such dignitaries as United States senators.12 It was also told visually within the Utah Capitol rotunda The celebratory panels of Works Progress Administration artists Lee Greene Richards, Waldo Midgley, Gordon Cope, and Henry Rasmussen contain one scene depicting the Brigham Young party hoisting the American banner on the peak. One critic swallowed hard:

Tourists gaze upon it and are deeply impressed. The youth of Zion view it reverently, and returning to their school desks write about it with pride Why contend that the story is too good to be true? In this instance, truth may never overtake fiction. The radiant fancy of the poet and painter has eclipsed the historian's carefully considered opinion.13

Like the Pilgrims' Plymouth Rock, Ensign Peak had gained a life of its own Susa Young Gates, Brigham Young's talented and prolific daughter, was another catalyst She was aware of the historical proscriptions of Roberts and others but would have none of it. Defending her patrimony, Gates's KSL radio address, June 1, 1929, argued that after the pioneer leaders had ascended and named Ensign Peak, the Stars and Stripes flew from a pole raised by Wilford Woodruff. She cited Cowley as her source.

14

Later she was more cautious. Working on a biography of her father, Gates wrote several rough drafts that acknowledged the revisionism of "recent students," but she used careful phrases to retain her intent The United States flag or "its equivalent" had been flown on the peak either on the first day or "a little later," she now said In her view the Saints' allegiance to the United States was staunch Joseph Smith and Brigham Young never had "the least idea of leaving the country whose flag of freedom had floated over the[ir] homes and [in whose] victorious armies . . . [had] marched their own revolutionary sires.

11 Ibid

12 Atlanta Georgian, February 17, 1908, as cited in Roberts, Comprehensive History, 3:272-73; and Deseret Evening News, November 4, 1911, p 31

13 Mark A Pendleton, "Ensign Peak," p 1, MS, University of Utah Library, Salt Lake City

14 Susa Young Gates, Brigham Young: Patriot, Pioneer, Prophet: Address Delivered Over Radio Station KSL, Saturday, June 1, 1929 (Salt Lake City?, n.d.), p 10

EnsignPeak9

The land of America was Zion to these leaders and to their associates and friends—patriots and sons of patriots all."15 These passages were later cut when her severely reduced manuscript was published

There were several reasons why the mythic version of the flag-raising refused to die. First, for anxious Utahns hoping to mend fences with their fellow Americans it put to rest the nineteenth-century calumny of LDS disloyalty with compelling force. It told of a lifted ensign during the dramatic first moment of colonization and placed at front stage Mormon leaders, not subordinates But there was another reason. Despite the expert witness of Roberts and Jenson to the contrary, the legendary Ensign Peak flag-raising contained more than a kernel of truth. Recent probing into the documentary record suggests that the Mormon pioneers may have raised two distinctive flags on the peak. The first, an American banner, was hoisted not on July 26, 1847, but likely several weeks later. The second flag is more problematic. An emblematic church ensign, symbolizing the gathering mission of Mormonism, may have been lifted as part of Utah's first Pioneer Day celebration, July 1849. Ironically, the twentieth-century Ensign Peak history controversy produced a minor surprise. Patriotism, rather than expert opinion, proved to have the larger claim to truth.16

The dispute over the early flag-raising was not the peak's only twentieth-century cultural expression. More telling and widespread, Ensign Peak hosted popular ritual. Starting in 1916 and continuing off and on for two decades, Utahns honored the historic site by hiking to its summit, usually as part of the state's July 24 Pioneer Day rites The Boy Scouts sponsored the first two celebrations with camp fires, games, flag-raisings, and talks by Roberts and Ruth May Fox, a member of the LDS Young Ladies General Board So successful were these pilgrimages that the boys and their leaders planned to make them an annual event.17

15 These passages consistently appea r in the various preserved drafts of chap 9, Susa Young Gates Papers, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City

16 Th e question of the Ensign Peak flag-raising is treated in Ronald W Walker, "'A Banner Is Unfurled': Mormonism's Ensign Peak," forthcoming, Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. Two me n claimed to have been present when the American flag was hoisted; see Joh n P Wriston, 'Th e Book of the Pioneers," unpublishe d miscellany collected by the Utah Semi-Centennial Commission, 1897, Utah State Historical Society, p 344, an d "Remarks of Harrison Sperry," Deseret News, August 14, 1920, sec 4, p vii A tattered American flag that some claimed had bee n flown o n the peak in 1847 was displayed forty-one years later; see Deseret Evening News, July 25, 1888, p 2 For the possible flying of the distinctive Mormo n flag see Franklin D Richards Diary, July 21, 1849, an d Charles Benjamin Darwin, "Journal of a Trip across the Plains from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to San Francisco,"July 1849, Huntingto n Library, San Marino, California

17 Deseret Evening News, July 27, 1916, p 2; Salt Lake Tribune, July 27, 1916, p 14

10Utah HistoricalQuarterly

But they were preempted. Adults as well as youth wished to be involved. In 1918 a World War I patriotic rally included the oratory of LDS general authority and historian Orson F. Whitney, his stentorian phrases lightened by patriotic singing and by the music of the University of Utah's U.S. Military Training Detachment Band. Some 700 citizens attended.18

The next year boosters planned "one of the most unique and historic church celebrations in the history of the state." "Autoists" were told to drive their vehicles to the new State Capitol and then proceed up West Capitol Street to the coiling dirt road that led to the base of the hill. Pedestrians could take the Capitol Hill streetcar line and walk on the new "scenic boulevard"—perhaps today's East Capitol Boulevard. Boy Scouts helped make these instructions explicit by marking the trail with buffalo-head emblems, each with an Indian arrow pointing to the summit.19

The program was as detailed as the travel instructions. It included flag raising and Scout salute; community singing, "America" and "Come, Come, Ye Saints"; invocation; soprano solo, "O Ye Mountains High"; historical sketch, Andrew Jenson; address, Richard W Young; community singing, "The Star Spangled Banner"; benediction; and the viewing of the summer sunset A small organ carted to the top provided music

EnsignPeak11

18 Deseret Evening News, July 23, 1918, p. 2. 19 Deseret Evening News, July 19, 1919, sec 4, p vii, and July 25, 1919, sec 2, p 2

Both Ensign Peak, immediately right of State Capitol, and streetcar line, farther right, show in this unusual Shipler photograph in USHS collections.

The address of World War I hero Gen. Richard W. Young, then president of the LDS Ensign Stake, was characteristic of the entire proceeding. He praised the pioneers and urged his audience to copy their example. But much of his talk reflected the era's sturdy national loyalty For fifty years, Young said, Ensign Peak had stood for Utah's patriotism. It was Utah's symbol of the national spirit and its love of country.20

Most of the annual celebrations that followed took place in the late evening with programs that included community sings, solos, campfires, games, flag-raising, and the usual watching of the summer sunset. Some of Utah's leading figures spoke. In addition to Roberts, Fox, and Young, audiences heard Melvin J Ballard, Heber J Grant, Richard R. Lyman, Nephi L. Morris, Oscar W. McConkie, George Albert Smith, and Anthony W. Ivins. Sometimes the evening's activity held an unexpected twist On one occasion the celebrants left the hill at nightfall, lighting their way with picturesque Japanese lanterns and singing as they went.21

With people trooping to Ensign Peak each year, hopes were kindled for some kind of memorial. As early as the turn of the century city boosters had campaigned for a commemorative park near or around the hill. In August 1908 LonJ. Haddock, secretary of the Manufacturers' and Merchants' Association, proposed that the city, which held title to the ground, franchise the area to private developers They in turn would make the needed improvements and gain a profit by charging for access. Haddock thought the Ensign Peak area, with its history and commanding view, could become a "sort of Mecca for Salt Lake tourists."22

The local newspapers agreed. The slopes of Ensign Peak deserved to be preserved, the Deseret News thought, as the scene of "one of the most remarkable events in American history"—an allusion apparently to Brigham Young's alleged flag-raising. Other Salt Lake City newspapers were equally enthusiastic. The Inter-MountainRepublican believed Haddock's proposed project would be an ornament to the city: "Every root of lawn, every mass of flowers, every tree [on the peak], would attract the attention and provoke approving comment from the people of Salt Lake." With such a plan in place, the newspa-

20 Deseret Evening News, July 28, 1919, p 3; Improvement Era, September 1919, pp 1015-16

21 These events were reported in the Salt Lake City newspapers usually a day or two after the event For Japanese lanterns see Deseret News, J\\\y 25, 1922, sec 2, p 1

22 Deseret Evening Neius, August 8, 1908, p 4

12Utah HistoricalQuarterly

per predicted that a railroad to the summit was "inevitable." The SaltLakeHerald also joined the chorus. An Ensign Peak park was a "public necessity," it declared. Piping water to the summit would permit grass, shrubs, and trees, which would provide a "beautiful pleasure ground for all the people, rich and poor alike." The Herald was insistent: "Carry out the plans for Ensign Peak park, and do it now."23

For a while it seemed Ensign Peak and its neighborhood might harbor a forest. Several weeks after Haddock proposed his plan, U.S. Sen. Reed Smoot, recently returned from visiting Switzerland's managed forests, argued a similar policy for Utah The Deseret News immediately took hold of the idea and suggested the Ensign Peak area as a good place to start Utahns could sow hardy wildflowers on the top of the summit, while the sloping flat lands to the south might be planted with trees. Interested citizens had already begun offering funds for the project, the newspaper advised; now if only the sand and gravel diggers who were ripping at the west side of the hill could be restrained. The newspaper made a final suggestion that the city sponsor an annual children's Arbor Day for the peak. "When once the idea of reformation takes hold of the people and is made part of the work of the school children, the future of forests in this country will be practically assured," the News opined.24

None of these early plans materialized Eight years later Ensign Peak remained unchanged except for a new steel flagpole erected to replace the Herald's 1897 wood frame. But LDS Presiding Bishop Charles W. Nibley and his church had an innovative idea. In May 1916 he petitioned the city commission to permit the placing of a huge, concrete cross on the peak. The memorial, to be funded by the

EnsignPeak13

Charles W. Nibley. USHS collections.

23

10,

JH ; an d Salt Lake Herald,

9,

p. 4. 24

News, Septembe

16, 1908, p 4

Ibid.; Salt Lake Inter-Mountain Republican, August

1908, as cited in

August

1908,

Deseret Evening

r

church, should be large enough to be "readily seen from every part of the city."25

It was an earnest time, given to good works and ideal symbols, and Bishop Nibley and his church saw the proposed cross as a progressive antidote to the city's growing social unrest. It would set the right moral tone, doing more, said one, than "all the drafting of statutes and ordinances, the preaching of sermons, or the publishing of newspapers can ever do in this city and state."26 But the Mormon church had another reason for suggesting the memorial Many visitors came to Salt Lake City believing the Mormons were not Christians. "The monument is intended as an insignia of Christian belief on the part of the Church which has been accused of not believing in Christianity," said the DeseretNews.27 In short, the proposed cross would be good public relations

Nibley's plan met immediate opposition

The Reverend Elmer I Goshen of the First Congregational Church voiced his disagreement, while City Commissioner W. H. Shearman asked the question that many Salt Lake City citizens felt: How could a cross, a symbol never used by the Mormons, be more fitting than an unfurled American flag?28 Emil S Lund, a state legislator, expressed stronger objections His lengthy petition to the city commission attacked the plan, Mormonism, and even Christianity itself. "I fail to recognize where the cross has ever performed police duties," he wrote sarcastically. Nor was he pleased with any recognition of organized religion: "Christianity has failed, and a new era [is] coming, based upon material facts and the rights of humanity, upon which the cross of Christ has been a burden and obstruction of freedom." To these arguments, Lund added a constitutional complaint. The erection of a religious symbol on public property was a First Amendment violation, he believed.29 Rabbis William Rice and Samuel Baskin also entered the fight. Neither objected to a monument honoring the pioneers but opposed a religious symbol on public property They left their meeting with Commissioner Karl A Scheid, the most vocal supporter of the plan on the city commission, unmollified. If the plan went forward, the men

25 Deseret Evening News, May 5, 1916, p 2

26 Karl A Scheid as quoted in Deseret Evening News, May 9, 1916, p 5

27 Deseret Evening News, May 5, 1916, p 2

28 Deseret Evening News, May 9, 1916, p 5

29 Emil S. Lund to the Board of City Commissioners, May 10,1916, copy in Charles W. Nibley Papers, LDS Church Archives

14Utah HistoricalQuarterly

warned, the city's "united spirit of citizenship" would be destroyed— carefully measured words that were meant as an obvious warning.30 Five years earlier the city had thrown off the anti-Mormon partisanship of the American party. Rice and Baskin hinted that if the plans for a public cross went forward the old fires might be rekindled.

With the proposal facing a determined opposition, Commissioner Heber M. Wells, the former state governor, offered Bishop Nibley some behind-the-scenes advice. Wells recommended the church carefully nudge the petition through the city commission by not urging it too strongly. Most of the commissioners were already favorably inclined, he believed.31 Wells was right. His colleague, Commissioner Scheid, expressed the view of the majority in city government: "The commission could trust the organization that had constructed the temple, the Hotel Utah, the [LDS] administration building and the tabernacle to construct a monument that would be a credit to the city."32 Neither Scheid nor the other commissioners seemed concerned about the legality of erecting a religious monument on public land At least they did not address the issue

On May 25, three weeks after Nibley introduced the plan, a listless city commission met to consider it. Wells could see no reason for prolonging things. According to the former governor, everyone had "his mind made up anyway." The desultory discussion ended with a 41 vote. Shearman, complaining the plan had caused enough trouble already, cast the sole negative vote.33

The commission's approval failed to mute opponents Back at his B'nai Israel congregation, Rabbi Rice signaled his continuing resistance He promised that although neither he nor his congregation would seek an injunction against the building of the cross, a number of citizens, "not all of whom are Jews," probably would do so. Among the prospective litigants was Emil Lund.34

The opposition was not confined to non-Mormons. A number of Nibley's own communicants disagreed with the church's policy. One anonymous LDS letter writer ("I want to live quietly and privately") complained about the chosen symbol: "If a righteous man unfortunately was crucified I fail to see why the Mormons should perpetuate

EnsignPeak15

30 Salt Lake Tribune, May 23, 1916, p 14 31 Heber M Wells to Charles W Nibley, May 19, 1916, Nibley Papers 32 Salt Lake Telegram,, May 25, 1916, sec. 2, p. 1. 33 Salt Lake Telegram, May 25, 1916, sec. 2, p. 1. 34 Salt Lake Herald-Republican, May 27, 1916, p 4

this infamous death by building a cross on the Peak." He suggested the beehive or seagull as more appropriate commemorative tokens.35 His desire for anonymity was widespread. "Many of our good Mormon brethren have privately expressed to me their opposition," Wells reported in a letter to Nibley, "until I suggested that if they desired to make an argument against the proposition to please make it to you. Then they faded away."36 As always in such matters, some members were torn between religious compliance and personal feeling

Some LDS opposition was anti-Catholic, considering the cross to be papal One angry correspondent, who for once refused to be deferential, expressed "astonishment" at the church's position. "Bishop," he lashed out, "with all due respect to you and your intelligence, I do not hesitate to say to you, that you are either influenced by the Roman Church officials, or are ignorant of the moral turpitude of this same powerful influence, which seeks to dominate every institution in City, State, and Nation."37

James Z. Stewart, a devout churchman who had spent many years in proselyting in Catholic Mexico, also strongly opposed the scheme. "I have heard many Latter-day Saints express their disapproval of it, and I must say that I would regret very much to see it placed there," he wrote. For Stewart, like others, the rub was the symbol. Rather than a sign of true Christianity, he saw the cross as Romanish superstition or, worse still, the chilling, apocalyptic "sign of the beast" spoken of in the Book of Revelation.38 A multitude of appropriate pioneer symbols could properly adorn historic Ensign Peak, Stewart thought, "but the cross never."39

Even the parents' class of the influential LDS Twentieth Ward joined the controversy. After a "full and complete discussion," class members unanimously registered their "emphatic protest," which was conveyed in their written memorial. Perhaps a flag-topped obelisk bearing the name of Brigham Young would do. But authorities must not permit a cross on Ensign Peak's incline.40 Faced by the growing hostile tide, the church quietly dropped its proposal.

> To Charles W Nibley, May 9, 1916, Nibley Papers

3 Wells to Nibley, May 19, 1916

7 Charles Lerane? to Charles W Nibley, May 13, 1916, Nibley Papers

4 Revelation, chaps 13-14

'J Z Stewart to Charles W Nibley, May 30, 1916, Nibley Papers

5 A T Christensen, "Supervisor," to Charles W Nibley, June 14, 1916, Nibley Papers

16Utah HistoricalQuarterly

EnsignPeak17

During the following years, other ideas for anEnsign Peak memorial surfaced Onesuggested a large sign on the hill saying "THIS IS THE PLACE," Brigham Young's aphorism, which perhaps could be blazoned in neon. 41 The 1934 Ensign Stake proposal was less flamboyant Its Mutual Improvement Association suggested a tower monument built ofeight- to twelveinch stones taken from the church's various units and historic sites. The latter, it was suggested, might include large rocks taken from such places asJoseph Smith's Sacred Grove near Palmyra, New York, thefabled temple lot from Independence, Missouri, and sites on the old Mormon pioneer trail.42

The Ensign Stake plan was elaborate It proposed that each stone mortared into the monument should be identified with a metal rivet—or failing that, perhaps a paper outline ofeach could be placed within the memorial On the outside or facade, the recently formed Pioneer Trails and Landmark Association promised a bronze plaque. John D. Giles, the PTLA executive secretary, thought the project would "doubtless be the greatest effort yetundertaken" by the fledgling association.43

The Salt Lake City Commission gave its sanction, while local architect George Cannon Young, a grandson of Brigham Young, provided the design. Most of the eighty main LDS church units complied by sending representative stones, though the Alberta, Canada, Stake,

42 Deseret News, May 23, 1934, p 9

43 Ibid.

A stone monument was erected in 1934 on Ensign Peak. Salt Lake Tribun e photograph in USHS collections.

" Junius F Wells, "Brigham Young's Prevision of Salt Lake Valley," Deseret News, December 20, 1924, Christmas News Section, p. 60.

either through misunderstanding or zeal, shipped an abounding one hundred pounds of material. Seven weeks after the project had been announced, masons put the first stone in place, taken from the old paper mill site at the mouth of Big Cottonwood Canyon. A plinth of granite secured from the old Salt Lake Temple quarry served as a base. The entire monument was ready for dedication a week later. It stood a commemorative-fitting 18.47 feet in height, marking, of course, the year of the pioneers' arrival. Its squared foundation was presumably the same dimension.44

Five hundred attended the unveiling on July 26, 1934, and if newspaper reports of the services were accurate, Ensign Peak once more hosted pioneer and patriotic themes. George Albert Smith sketched the history of the first trek to the summit; Anthony W. Ivins, counselor in the LDS First Presidency, recalled his youthful visits to the area when he dug sego lilies for scant nourishment; and Mormon President Heber J Grant reminisced about early Salt Lake City days when Main Street was scarcely more than a "cabbage patch."45 The Reverend John Edward Carver of Ogden provided the non-LDS counterpoint As the main speaker of the day, Carver continued the praise of pioneer virtue. Unlike the nineteenth-century trader and hunter, Utah's settlers had made homes and had transformed the Salt Lake Valley into the "most beautiful city in the world." Carver closed by urging LDS youth to continue the Mormon epic.

Then, with a full moon rising over the eastern mountains, the program closed with the singing of pioneer songs and the lowering of the American flag to the strains of "America."46 "It was very hard climbing [to the top]," said seventy-seven year old Grant after the experience. "But I thoroughly enjoyed the evening's entertainment."47 Apparently several flagpoles were put in place after the building of the Ensign Stake's memorial. In the late 1930s and early 1940s a tall, three-pillared pole rose on the mount, replaced later by a single post erected by the LDS Emigration Stake. In turn, in 1955 the 115th Engineers of the Utah National Guard prepared the foundation for yet another flag tower. Their blasting literally shook parts of the city

18Utah HistoricalQuarterly

44 Salt Lake Tribune, July 27, 1934, p 20; Salt Lake Telegram, July 17, 1934, p 12; and Deseret News, July 19, 1934, pp 9, 11 45 Deseret Neivs, ]u\y 26, 1934, p 9, and July 27, 1934, pp 13, 20; Salt Lake Tribune, July 26, 1934, p 20 46 Deseret News, July 26, 1934, pp 13, 20; Salt Lake Tribune,]\x\y 26, 1934, p 20 47 Heber J. Grant Diary, July 26, 1934.

and brought a flurry of worried phone calls Then twenty volunteers from the Salt Lake City Fire Department and the Utah Power and Light Company lugged the new 700-pound, 40-foot pole to the summit, which was dedicated in a special Veterans' Day Service in honor of LTtah's servicemen.48 Thereafter, Guardsmen designated six annual events when they planned to fly the flag from the peak: Washington's Birthday, Memorial Day, Flag Day, Independence Day, Pioneer Day, and Veterans' Day.49

While many continued to honor the spot, others were less respectful. Two years after the monument's dedication vandals fired thirty rifle shots into the bronze marker that had been attached on the south side of the stone monument "Many of the letters appear damaged. Too bad," disparaged a letter to the Deseret News. In succeeding years the marker was stolen, while still later the new flagpole was vandalized When members of the United Veterans Council hiked to the top of Ensign Peak to place a bronze plaque on the pole they found that pranksters had battered its locks and partially cut its cable. Both had to be replaced "Youngsters are only hurting themselves when they damage an American flagpole," one of the veterans lamented. "It's their flag that flies from that pole." Such destructive acts became commonplace to the poles and memorial on the summit.50

There were other indignities. From the start of the century businessmen had tried to exploit the promontory "An automobile at the top of Ensign Peak!" began a 1910 newspaper article. "That was where a Velie '40' was Tuesday, and no other car had been there before which simply proves that to a good, reliable car there is no such word as 'can't.'" Not to be outdone, two weeks later the picture of a competing automobile also appeared in the newspaper. Said the supporting caption: "A great deal of excitement was caused the past week when the Randall-Dodd Automobile company drove a model 10 Buick to the top of Ensign Peak. ... A year ago it was thought an impossibility to drive a car up the steep incline, but machines are made so perfect nowadays that hills do not prove much of an obstacle for the average driver."51 The gimmick was successful enough to bring

48 Deseret News and Telegram, November 8, 1955, p 2B.

49 Deseret News, May 7, 1957, p 12

50 C V Hansen in Deseret News, October 21, 1936, p 4 In 1992 the original plaque was found supposedly in a West Jordan, Utah, chicken coop. See Deseret News, LDS Church News Section, October 17, 1992, pp. 4, 7.

51 Salt Lake Tribune, March 10, 1910, p 4, and March 27, 1910, p 18

EnsignPeak19

VELIE AUTOMOBILE CLIMBS ENSIGN PEAK

AUTOMOBILE ON ENSKIN' TEAK

From the Salt Lake Tribune, March 10, 1910.

another imitator. A Thor motorcycle with a passenger in a sidecar made it to the peak's flagpole in 1916 "An impossible feat for any previous motorcycle" was the boast.52

More disturbing, members of the Ku Klux Klan used Ensign Peak to further their purposes. Despite the on-going opposition of LDS and most Utah civic leaders to their cause, Klansmen in 1925 staged a nighttime Washington's Birthday recruiting parade in the capital city The event was heralded by a suddenly appearing, burning cross on Ensign Peak. Then a cavalcade of hooded and robed Klansmen, estimated to number several hundred, wove its way through downtown Salt Lake City.

Two months later an even more dramatic KKK event unfolded. On the evening of April 6, 1925—a date chosen to coincide with influx of visitors to the semiannual Mormon General Conference—startled Salt Lake City citizens once more saw Ensign Peak aglow, this time with several large KKK crosses that were starkly visible throughout the valley. Beneath these fiery tokens on the semilevel flats below, "thousands" of Klansmen met that evening in a formal Konklave. The

20Utah HistoricalQuarterly

52 Deseret Semi-Weekly News, May 4, 1916, p. 3.

ceremony centered around two altars, about five hundred yards apart, where induction into the Klan's various orders took place. A circular sentry line of Klansmen, estimated to be a mile long, gave anonymity to the participants and their parked automobiles.

A KKK spokesman pronounced Utah's first Konklave to be "in every way a great success." It certainly seemed so In addition to the assembled Klansmen, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Utahns watched the event on the Ensign Peak downs, just beyond the KKK pickets, while still more observed from the valley. The "pageantry, mysterious garb, mystical ritual, fiery crosses, billowing flag displays, and martial music presented a spectacular sight," a historian of the Klan later wrote. To be sure, the nocturnal ceremony had an effect. For the next several days Salt Lakers were "talking Klan and thinking Klan," though the movement never established deep or long-lasting roots in the state.53

The Klan was not the only organization to use Ensign Peak Salt Lake City's West High School used its slopes to place timbers in an "W" configuration; the wood was periodically burned when the school had a special celebration And rumors circulated that Mormon Fundamentalists secretly used the place. Denied entry to LDS temples, so the story went, these LDS dissenters recalled Brigham Young's 1849 consecration of Ensign Peak for prayer and the endowment ceremony and performed such ordinances there themselves.54 A mysterious flag, flown from the peak six months after the start of the Second World War, seemed to lend credence to these rumors. This banner—probably a Fundamentalist standard—had thirteen red and purple stripes and a dark blue canton containing forty-eight, seven-pointed gold stars and a larger, truncated gold star in the middle bearing the insignia "United Israel of America." Arnry officials confiscated it from the local police for "investigation," and in the excitable spirit of the time cryptically refused to comment on the "possibilities of the flag's designer and what it stood for."55

Commercial interests also tried to use Ensign Peak for their purposes. One business hoped to put several large, electric advertising

53 Larry R Gerlach, Blazing Crosses in Zion: The Ku Klux Klan in Utah (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1982), pp. 104-9.

51 Franklin D Richards Diary, July 23, 1849, LDS Church Archives Immediately after Young's dedicatory prayer, Addison Pratt, already called to a South Seas LDS proselyting mission, received his endowment on the peak The tradition of other LDS endowments being performed there during the nineteenth century is preserved in the Deseret Neivs, July 24, 1897, p 9

55 Salt Lake Tribune, June 4, 1941, p. 13.

EnsignPeak21

Confiscated United Israel of America flag displayed by, left to right, Sgt. Larson, Officer Springer, Capt. Carter, Put. C. L. Ping, Sgt. Steinfeldt, Allen George, and Lt. William A. Cody, provost marshal at Fort Douglas. Salt Lake Tribune photograph in USHS collections.

signs on the crest of the hill. The city commission rejected this proposal. Then an oil refining company returned with a new proposal, thinly disguised as a public service project The company promised to build a huge, flashing billboard on the summit that would encourage safe driving, asking only to prominently feature its trademark and name on the sign.56

These efforts raised several important questions. What was the best use of Ensign Peak land? Should commercial development or historic preservation receive the highest priority? The answers were not always environmentally sensitive. During the latter part of the twentieth century sand and gravel companies continued to gnaw at the mount's western slope Moreover, some traffic planners hoped to construct a multilane "Bonneville Drive," which, if built, would require deep and scarring cuts on the west and south sides of the hill or a three-mile tunnel burrowed near the peak Southbound Davis County traffic, they explained, needed better access to Salt Lake City.57

For a moment there was even talk of mining ore on the peak

During the uranium boom of the 1950s one prospector who claimed to hold mineral rights to some of the area hoped for a big strike. "We've had some determinations," he said The ore "is there, but we don't know in what quantity or quality."58 Such expansive rumors had

56 Salt Lake Tribune, March 25, 1952, p 9, and December 7, 1952, sec C, p 10

57 Deseret News, March 14, 1974, p 2B, and April 24, 1974, p 2D The length of the proposed tunnel, later shortened, proved too costly to build and the scheme was abandoned

58 C L Singleton in Salt Lake Tribune, March 30, 1956, p 8B

22Utah HistoricalQuarterly <+m 4 $ 4& j ^ jg| ^ \T s> &^ B ^

a precedent During the nineteenth century gold miners had pocked the hill with exploratory caverns and left tailings scattered across the hillside. Even the remnant of a cart road, used to take their mining machinery to the northern bench, remained visible.59

During World War I officials had tried to extract another kind of resource from the Ensign Peak bench. As City Commissioner Herman H. Green explained in June 1917: "In the present war situation, with increased food production a crying demand, I think it would be a little short of criminal to allow the [Ensign] flat to remain idle when it will produce grain." To carry out the enterprise, Green secured the "expert opinion" of University of Utah PresidentJohn A. Widtsoe, the loan of a state tractor, and several "gang plows" to aid the machinepowered machinery They city expected that 20,000 bushels of turkey red wheat could be dry farmed on 1,500 acres below the summit.60

None of the efforts had a permanent effect on the landscape. By the early 1950s the land north of the State Capitol remained largely intact—a "barren, wind-swept hill country" reserved for the eventual creation of a city park That at least was the repeated hope of several city officials. But such a prospect was threatened by growing land values. "The same topographic advantages which gave the peak area its historical significance have long drawn covetous glances from real estate men who know a good subdivision site when they see one," observed the Salt LakeTelegram. Indeed, the area promised to be "one of the most magnificent residential areas of the country."61

With such a valuable asset on their hands city officials equivocated. By 1952 Salt Lake City badly needed a new water purification plant in City Creek Canyon, and until one could be built the area was closed to recreation. Perhaps the Ensign flats land might be sold to finance City Creek water development, which in turn would reopen one of the area's old picnic spots. "What finer parting gesture could Ensign Flats make than to help out a fellow 'old-timer' in trouble," the Telegram thought.62

Evidently this rationale persuaded the city commission to act. It sold several hundred acres of the land immediately below Ensign Peak to a group of Salt Lake City businessmen in an uncompetitive

60 Salt Lake Telegram, June 29, 1917, 2d sec, p 10

61 Salt Lake Telegram, June 11, 1952, p. 12, and March 18, 1953.

62 Salt Lake Telegram, June 11, 1952, p. 12.

EnsignPeak23

59 James Aitken, Erom the Clyde to California with Jottings by the Way (Greenock, Scotland: William Johnston, 1882), p 55

sale, which at the time rankled the Salt Lake Real Estate Board, the Utah Home Builders Association, and the Chamber of Commerce. 6 3

In later years the move equally angered preservationists, who censured the controversial deal as a breach of the city's long-standing aim of placing a park on the north bench.

For its part, the city claimed a memorial was still in its plans—if not on the recently sold land, at least on the summit There, officials promised, "something really splendid" would be worked out, with access routes and observation facilities for a "fitting monument." The proposed park would celebrate history and at the same time offer a vantage point of "unmatched beauty and inspiration."64 A half-dozen years later the National Guard seemed ready to help. As a training exercise it offered to build a road to the top of the peak that would open its "scenic and tourist" resources Such a scheme, predicted the Salt LakeTribune, "would prove quite an attraction."65

Those hoping to preserve the land were unsure of the city's resolve. This historical site must never be used for "commercial or for mercenary purposes," the Sons of the Utah Pioneers insisted. "It must be developed into a beautiful and sacred shrine where visitors may be made acquainted with the purpose for which it was dedicated."66 To ensure such a result, Wilford C Wood, a Bountiful furrier and historical collector, offered to buy Ensign Peak in 1955, but the city declined The "land atop Ensign Peak is destined to become a city park," Park Commissioner L. C. Romney once more affirmed.67

In the early 1960s an ambitious plan for a "memorial, public pavilion, information center, and outstanding landmark" rivaling the "This Is the Place" Monument was drawn by Salt Lake architect Roger M. Van Frank and received the support of such community boosters as Nicholas G. Morgan, Sr. The blueprint called for the surface of the summit to be paved with a giant concrete observation deck on which an "ultra-modern" building would be placed Its roof, explained Van Frank, was designed to mark the exact crossing of the pioneer eastwest, north-south meridians that had begun the nineteenth-century Utah land survey. Others attributed still greater significance to the location. "It would honor the spot where Brigham Young made his final

63 Deseret News and Telegram, March 18, 1953, p 12A

61 Ibid

m Salt Lake Tribune, October 21, 1959, p 20

66 "Brigham Young Foresaw Mount Ensign," Pioneer 5 (July-August 1953): 16-17, 50

"7 Salt Lake Tribune,July 13, 1955, p 25

24Utah HistoricalQuarterly

decision to settle the valley," reported the Deseret News, "where some people believe the Mormon leader may actually have made his famous remark, 'This is the place.'" Unfortunately, this project, like the various ideas for an Ensign Peak park, died due to the lack of community support.68

Thirty years later the promise remained unfulfilled. Ajoint resolution of the Utah State Legislature called for the preservation of the area, and the current developer, Ensign Peak Incorporated, traded over sixty acres to the city to permit the building of a parking lot at the base of the peak and a hiking trail to the crest To assist this work a citizen's foundation was organized. It quickly abandoned the old ideas of a summit-climbing automobile road and the construction of a large memorial on the top Instead, foundation and city officials spoke of a nature and history walk that would allow future Utahns and tourists to savor Ensign Peak in a state similar to that of 1847.69 To initiate these plans the foundation once more sponsored Pioneer Day community hikes reminiscent of the 1920s and 1930s The July 26, 1993, ceremony included LDS General Authorities Gordon B. Hinckley and Loren C. Dunn, Salt Lake City Councilwoman Nancy Pace, and state legislator Frank Pignanelli Crowd estimates ranged as high as 1,400. The new development was scheduled for the state's 1996 centennial celebration.70

Whatever its future, Ensign Peak has already played an important role in the history of Salt Lake City and the wider Utah community During the twentieth century it had pitted religious traditionalists and historians. Later, during its Christian cross controversy, the peak had briefly set at odds Mormon leaders and unmalleable followers. Still later, it put commercial boosters and preservationists in opposition to each other. Through all these twists and turns Ensign Peak, as symbol and site, has conveyed aspects of Utah's popular culture.

68 Deseret News, December 15, 1962, B7 The plan included a "perpetuating fund" for the future upkeep of the memorial

69 Deseret News, LDS Church News Section, October 17, 1992, pp 4, 7

70 Salt Lake Tribune, July 27, 1993, p. B3; Deseret News, July 27-28, 1993, and LDS Church News Section, July 31, 1993, pp 3, 6

EnsignPeak25

The Wasters and Destroyers:

Community-sponsored Predator Control in Early Utah Territory

BY VICTOR SORENSEN

BY VICTOR SORENSEN

Monday, 25th [December 1848] Th e reports of guns were heard in every direction, which is nothing uncomo n about chrismas times, but insted of waisting their Powder as usual on such ocasions, hundred s of Ravens no doubt were killed on that day. Th e Boys being full of shoot as well [as] the Spirit of the Hun t went it steep. 1

THI S EXCERPT FROM JOHN D. LEE'S JOURNAL records the first shots fired in one of the major battles of man's war on predatory animals in Utah Territory The following study of two community-sponsored predator hunts that took place during the early settlement of Utah—one in the Salt Lake Valley and another in Cache Valley—will provide a narrative of the hunts, explain why they took place, and explore why they were

Mr. Sorensen lives in Hyde Park, Utah.

1 Robert Glass Cleland and fuanita Brooks, eds., A Mormon Chronicle: The Diaries ofJohn D. Lee, 1848-1876, 2 vols (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1955), 1:85

Nauvoo Legion encampment, undated. Some members of this citizen army participated in the winter 1848-49 predator hunt, although the legion had not been reorganized in Utah at that time. USHS collections.

carried out in a particular fashion. In almost any historical event, multiple factors contribute to create and give meaning to what has happened In the case of these hunts, factors ranging from survival to hatred of predatory animals must be considered.

As the Mormon pioneers prepared for their second winter in the Salt Lake Valley, church leaders took steps to secure the community's livestock and foodstuffs against the uncertainties of frontier life in their new community. Early in December 1848, due to problems with wolves, foxes, ravens, and other animals, "it was considered advisable for rival companies to be organized to destroy the same."2 Entrusted to carry out this plan was the Council of Fifty. This body, made up of prominent leaders of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, was organized byJoseph Smith in 1844 to act as the political or civil arm of the kingdom of God. In conjunction with the leaders of the Salt Lake Stake, the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and the First Presidency of the church, the Council of Fifty played a critical role in the preterritorial government of Utah.

John D. Lee, a member of the council, recorded in his journal the proceedings of that group as it debated the issue of predator control:

Amoung the Many, Th e wasters and destroyers was taken into consideration, to wit, the wolves, wildcats, catamounts, Pole cats, minks, Bear, Panthers, Eagles, Hawks, owls, crow or Ravens & magpies, which are verry numerous & not only troublesome but destructive. 3

To remedy the problem, Brigham Young appointed John D Lee and John Pack to be captains of two competing teams consisting of one hundred men each to make war on the predators. Thomas Bullock was designated as clerk to keep the whole affair in order.

On Christmas Eve 1848 Bullock and Pack went to John D Lee's home to make the proper arrangements for the hunt. They drafted the "Articles of Agreement for Extermination of Birds & Beasts" as well as a list of hunters who were to participate.4 In this document the rules and rewards of the hunt were defined:

Articles of Agreement between Captains Joh n D Lee and Joh n Pack, made this 24th day of December, 1848, to carry on a war of extermination

2 Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (hereinafter JH), December 7, 1848, microfilm copy in Special Collections, Merrill Library, Utah State University, Logan

' Cleland and Brooks, A Mormon Chronicle, 1:82

4 Edith Jenkins Romney, ed., "Thomas Bullock Diaries," December 24, 1848, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City

PredatorControl27

against all the ravens, hawks, owls, wolves, foxes, etc., now alive in the valley of the Great Salt Lake Firstly; it is agreed that the two companies shall participate in a social dinner with their ladies, to be made in the house of said Joh n Pack, on a day to be hereafter name d and to be paid for, by the company that produces the least numbe r of game

Secondly; the game shall count as follows, the right wing of a raven counting one, a hawk or owl two, the wings of an eagle five, the skin of a minx or pole cat five, the skin of a wolf, fox, wild cat, or catamount ten, the pelt of a bear or panther fifty. No game shall be counted that has been killed previous to this date

Thirdly; the skins of the animals, and the wings of the birds, shall be produced by each hunte r at the recorder's office, on the 1st day of February, 1849, at 10 a.m. for examination and counting at which time the day for recreation will be appointed

Fourthly; Isaac Morley and Reynolds Cahoon shall be the judges or counters of the game, and to designate the winners and Thomas Bullock be the clerk to keep a record of each man's skill, and to publish a list of the success of each individual

Fifthly; the ma n who produces the most proofs of his success shall receive a public vote of thanks on the day of the feast.5

The list of hunters is an interesting document in itself. Those familiar with Utah or LDS church history will recognize many of the names. Brigham Young, Willard Richards, and Heber C. Kimball constituted the First Presidency. Members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, leaders of the Salt Lake Stake, and other important men in the community are also well represented Significantly, thirty-five of the participants were members of the Council of Fifty, as were the clerk, both judges, and both team captains, leaving no doubt that this was a Council of Fifty affair.6

On Christmas Day 1848 the shooting began. News of the hunt must have spread by word of mouth because the "Articles of Agreement" and the list of hunters were not made public until that evening when John Pack took them down to the old fort to post them, along with a "Notice to hunters to have a Field Dayon Monday next."7

Little detailed information exists to tell us how the hunt proceeded.John D. Lee, team captain, who kept an activejournal during this time, makes no mention of any hunting activity personally. The only record forthcoming of personal participation comes from a man

' JH, December 24, 1848 The Articles of Agreement and its accompanying list are found in both the Journal History and in John D Lee's journals with only minor discrepancies

6 D Michael Quinn, "The Council of Fifty and Its Members, 1844 to 1945," Brigham Young University Studies 20 (Winter 1980): 193-97

' Romney, "Thomas Bullock Diaries," December 25, 1848

28Utah HistoricalQuarterly

J.D Lee

LIST OF HUNTERS

J Pack

J. D. Lee

Heber C. Kimble

W Richards

P.P Pratt

John Young

Edward Ellsworth

Gardner Potter

Seth Dodge

Aron Farr

Samuel Cams

David Cams

Wm A Pirkins

J.S. Fulmer

Horace Draker

Orson Drake

Jas Allerd

W.K Rice

Peter W Conover

David Fulmer

Jas Orr

Hosea Stout

Chas Kenedy

Jas Davis

A.C Brower

Samel Turnbow

Levi Stewart

Henry Gipson

Wm Bird

Justin Shepherd

Gilbreth Haws

Jas Gorden

Angus Dodge

Samuel Caldwell

John D Holyday

Alexander Williams

Seth Tanner

Stephen Chipman

Washburn Chipman

Isaac Morly.Jr.

John Scott

J.M Grant

S Keeler

Williard Snow

Jefferson Edmunds

Ethen Pettitt

Alexander Harriss

Wm Woodland

Wm G Perkins

Robert Campbell

Geo. Bean

Jas. Ivie

Jud Stadard

Franklin Ivie

John Higbee

Wm Norton

Edward Walters

Samuel Campbell

Robert Owens

Wm Matthews

Wm Croasby

A.P Dowdle

Jackson Allen

Francis Williams

Jos. L. Haywoode

CP Lott

Shadraich Holdaway

W.G. Pain

Ebneezer Brown

H.S Eldridge

John Bankhead

F.D Richards

Eprain Pearson

Richard Bush

[ ] Pace

Sandford Porter

Wm McKowen

Lorenzo Snow

W.W Phelps

Wm Clayton

J.L. Smith

Chas. Decker

A.P. Free

Wm. Lammy

Z.W Sparks

J.S Allen

Joel Ricks

E.D Wooley

Daniel McArthur

Z.W Rasacrance

Jefferson Hunt

J.W Hickerson

T.S Williams

Zerah Pulcipher

John Pack

B. Young

A Seymour

John Taylor

John Smith

Edward Hunter

Wm Potter

P Sessions

Jas Brown

G.D Grant

C.C Rich

Daniel Cams

D.H. Wells

Alex. Boss

Sandford Bingham

Hecter Haight

Fatter Drake

I.C Haicht

Thos Bingham

Chancy West

Chas Shumway

M.D Hamilton

Shadrach Roundy

B.F.Johnson

A. Rice

OP. Rockwell

Darwin Richardson

Vincent Shirtliff

[ ] Robbins

Daniel Spencer

Andrew Cahoon

Wm Empy

Jos Matthews

Jas M Flake

John Holladay

John Vancott

Lorenzo Young

Hyram Gates

Levi Reed

Wm. Kimble

Liwis Robbinson

Erastus Snow

Jazareel Shewmaker

Brown Crow

James Richey

Allen Smithson

Moses Thurston

John Norton

Loren Walker

Wm Brown

E.K Fuller

Daniel Hendrix

Isaac Higbee

Thos Bingham

J.A Armstrom

Elijah Clifford

John Kay

Bur Frost

J.M. Burnhisal

Albert Carrington

Jacob Gates

Abraham Conover

P.B Lewis

John Topham

Young Boyce

Schyler Jennings

Benj F Mitchel

Chas C Burr

Wm M Lamon

Jas Beck

Daniel M Thomas

Francis McKowen

Jos P Fielding

Phinehas Richards

Geo. B. Wallace

Young Thomas

Claudiaus V. Spencer

Chas Chapman

Isaac Lancy

Loran Farr

Thomas Richey

Simeon A Dean

James Craig

Samuel Wooley

Barnabas L Adams

Albert Petty

Hanson Walker

Lorenzo Twitchell

Nathanil Fairbank

Dimick Huntington

Abraham Washburn

John Brown

N.K Whitney

Predator Control29

who is not found on the list of hunters. Thomas Bullock's journal entry for December 26 reads: "The brethren busy shooting the Crows ... in afternoon T.B. [Thomas Bullock] & R.C. [Reynolds Cahoon] go out on shooting foray, the Crows very wild secured 5 wings. ..." With Bullock and Cahoon serving as clerk and judge of the competition respectively, it seems odd that they would also be shooting Perhaps the early days of the hunt were something of a free-for-all. Writing from Salt Lake City on January 1, 1849,John L. Smith noted that "There is a general raid by the settlers on bears, wolves, foxes, crows, hawks, eagles, magpies and all ravenous birds and beasts."8 The fact that Bullock made at least a third "Agreement and list of Shooters" on December 27 shows that the hunt was still being defined.

In reality the teams were never composed of 100 men each. The lists vary between 186 and 209 names, but only 84 men ever turned in hides and wings to be counted Most of the men on the lists would not have found time to participate, especially those with pressing duties in their ecclesiastic, civic, and personal lives.After all, the individuals did not volunteer; rather, their names were chosen by the organizers. 1 JH, January

30Utah HistoricalQuarterly

John Pack from A Bit of Pack History or Biography by WehrliD. Pack (1969).

John D. Lee. USHS collections.

1, 1849

Many of the notables on the lists were probably there purely out of respect and the prestige of having them associated with one's team. Others may have felt like Hosea Stout who, upon learning that he was chosen to participate, "declined to accept the office not feeling very war-like at this time."9

Despite a lack of information about the details of the hunt, the final figures grimly attest that it was carried out with success. During the month ofJanuary one alteration in the rules did occur, according to Lee's journal:

During the intermission of the council, the Hunters made such rapid havock, among the Wolves & Foxes especially, that it was thought best by the captains of the Hun t to continue slaying one mount h longer, which was aggreeable to the wish of the feelings of the council Th e Capts. however met on the first day of Feb. to notify their Men of the last arraingement. 1 0

March 1, the day appointed for counting the game, was clear and mild by all accounts. Thomas Bullock kept a record and a tally of the day's proceedings:

Captns. Pack & Lee with Fars. Morley & Cahoon as Counters 8c T.B. Clerk at Office to receive Game when the brethren brought as follows

Lee protested that roughly two thirds of his men were not accounted for, "not having notice in time; but the greater part of Capt. John Pack's game was brought in on that day." Not ready to give in, Lee probably petitioned the Council to make the final day of counting

9Juanita Brooks, ed., On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844-1861, 2 vols (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1964), 2:338

10 Cleland and Brooks, A Mormon Chronicle, 1:87

11 Romney, "Thomas Bullock Diaries," March 1, 1849 The 84 people referred to on the list under "total killed" were, of course, total participants.

PredatorControl31

Persons Wolverines Wolves Foxes M[inks] Eagle Magpies Ravens Joh n Pack's Side 47 2 247 151 10 5 377 558 J<ihn D Lee's Side 3784 651 130 340 Total Killed 84 2 331 216 10 9 507 898 5,332 2,110 n

March 5, for on March 3 the council voted that "those persons who had not already reported the amount of game they had killed in the late hunt, have the privilege of counting the same on the following Monday at the Council house."12

Things seemed to be getting a little out of hand at this point. Lee recorded that on the morning of March 5,

Wolves, Foxes, mi[n]ks 8cc.8c the wings of Raven, Magpies, Hawks, owls

8c Eagles were roling in to the clerk's office in every direction to be counted, each Hunte r eager to gain the contest. At 4 P.M. poles closed, giving J.D Lee a majority of two thousand five hundre d 8c 43 skelps Th e entir No brought on both sides was estimated between Fourteen & Fifteen Thousand." 1 3

Bullock recorded it a little differently:

I. Morley - R. Cahoon -J.D. Lee & J. Pack in Office to meet the Hunters 8c count Scalps &c when the amoun t was counted, but on account of cheating I cannot record the exact amount but refer to the list-14

The "list" probably refers to the figures found in the Journal History, which gives a final inventory of the hunt's success as follows:

Joh n D Lee's company of 37 persons had killed 516 wolves, 238 foxes, 20 minks, 4 eagles, 173 magpies, and 439 ravens, which were considered equivilent to 8455 ravens and that Joh n Pack's company of 47 persons had killed 2 bears, 2 wolverine, 2 wildcats, 267 wolves, 171 foxes, 11 minks, 5 eagles, 359 magpies, hawks, and owls, and 687 ravens, equivalent to 5912 ravens; thus Lee's company claiming a count of 2543 ravens [majority] Total killed by both companies, 2 bears, 2 wolverines, 2 wild cats, 783 wolves, 409 foxes, 31 minks, 9 eagles, 530 magpies, hawks, and owls, and 1026 ravens. 1 5

The hunt may have achieved its objective of destroying many animals the pioneers considered threatening to their welfare, but the agreed-upon festivities and vote of thanks never came to pass.John D. Lee noted:

Thos. Williams on Capt. J.D. Lee's Side, won the vote of thank[s] by a majority of about 300 skolps He brought in about 2100 skelps Capt J

12 Cleland and Brooks, A Mormon Chronicle, 1:97; JH, March 3, 1849

13 Cleland and Brooks, A Mormon Chronicle, 1:100

14 Romney, "Thomas Bullock Diaries," March 5, 1849

lnJH, March 5, 1849. This list does not give an accurate description of the biological diversity existing in the Salt Lake Valley at the time Coyotes were undoubtedly killed by the hunters but counted as wolves or foxes Ermine and weasels were probably counted as mink And terms as general as fox, hawk, owl, and eagle make no distinction for specific species

32Utah HistoricalQuarterly

Pack was rather wo[r]sted 8c sadly disapointed when he found that on e 100 me n beat two Tribes of Indians & the white Tribe of the valley However n o insinuations Th e hun t resulted in good. 1 6

Lee, regardless of his denial, does insinuate that Pack lost despite cheating byenlisting thehelp ofIndians. In allfairness, Leeis suspect as well It was, in all likelihood, Lee who favored moving the dayof counting from February 1 to March 1 and later from March 1 to March 5.17 Both moves were to hisadvantage AndTom Williams,who almost single-handedly put Lee's team on top, was a man whohas been credited byonehistorian asbeing able to "steal anything from a hen on her roost to a steamboat engine."18 However, no insinuations. Actually, cheating and dishonesty have a long tradition in the predator control business. Early bounty laws hadtobe carefully constructed to prevent fraud by those whowould try to collect on the same wolf more than once. 19

Regardless of who cheated whom, the promised dinner never took place due to the squabbling of the captains Andthe public vote of thanks wasnot forthcoming because of the "unsavory reputation" that TomWilliams had built for himself over the years. 20 With that, this particular episode in the "war of extermination" came to a close.

As the Mormon settlers continued to spread throughout the Intermountain West they often faced the same hardships that beleaguered the original pioneers in the Salt Lake Valley. During the late 1850s and early 1860s the first settlers moved into the Cache Valley some ninety miles north of Salt Lake City. Notlong after their arrival problems with the fur-bearing residents of the valley resulted in another campaign to rid the area of predators Information about this Cache Valley hunt isvery sketchy and is taken entirely from reminiscences recorded decades after the fact Even the year it occurred is subject to debate But enough information exists to allow for a comparison with theSalt Lake hunt

One source says thehunt took place "about 1868,"butthat seems quite late considering thevalley hadbeen settled for almost ten years

16 Cleland and Brooks, A Mormon Chronicle, 1:100

17 JH, February 20, 1849

18 Juanita Brooks, John Doyle Lee: Zealot, Pioneer, Builder, Scapegoat (Glendale, Calif.: A H Clark Co., 1964), p 142

19 William Cronon, Changes in the Land: Indians, Colonists, and the Ecology of New England (New York: Hill and Wang, 1983), p 133

20 Brooks, John Doyle Lee, p. 142.

PredatorControl33

by then.21 Thomas Irvine, a participant in the hunt, while not mentioning any date, places "the big wolf hunt" between 1860 and 1863 in his recollections of early events in the valley.

As in Salt Lake, the hunt in Cache Valley was competitive Two groups were organized by dividing the valley into North and South teams with Logan, the principal town, also being divided. A certain point value was attached to the targeted species as well. When the hunt ended there was to be a dinner and dance held at the expense of the losing team.22

Some confusion exists as to who led the teams Joel Ricks,Jr., lists Thomas E. Ricks as captain for the North and Moses Thatcher as captain for the South. Another source lists Thomas E. Ricks as captain of the South and Sylvanus Collett as captain for the North.23 The latter arrangement seems most likely for reasons that will be explained later The mention of Moses Thatcher suggests that he was involved in some way and gives more weight to an earlier date than 1868 for the event since Thatcher was serving a mission for the LDS church in England that year.

The hunt took place during the winter when wolves and coyotes could be more easily pursued in deep snow:

Th e me n took advantage of such an occasion and hundred s mounte d horses for the contest and made a careful search through the fields of the valley Hundred s of coyotes and wolves were killed with heavy clubs and guns. Th e north side won and the South side had to treat to a big dance and feed.24

From the accounts, wolves and coyotes appear to have been the principal targets of the hunt, but crows and foxes are also mentioned, and it is quite probable that all predatory birds and animals were included. This hunt seems to have incorporated more team effort in driving the targeted animals into a concentrated area—a style known as a ring hunt—whereas the Salt Lake hunt was more of an individual effort, unless the "field day" called for by Thomas Bullock onJanuary 1, 1849, was also a day for a collective effort to concentrate the targeted species.

21 M. R. Hovey, An Early History of Cache County (Logan, Ut.: Logan Chamber of Commerce, 1925), p 65

22 Joel Ricks, Jr., "Some Recollections Relating to the Early Pioneer Life of Logan City and Cache County," pp. 7-8, 60, typescript, Special Collections, Merrill Library, Utah State University.

23 Hovey, An Early History of Cache County, p 65

24 Ibid

34Utah HistoricalQuarterly