* _ > M CO CO < O f O oo \ d w W 4X

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ . EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD O F EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City, 1997

KENNETH L CANNON II, Salt Lake City, 1995

JANICE P DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M. GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C. JANETSKI, Provo, 1997

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1995

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden, 1995

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00.

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5 l/4 or 3 x/i inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file. For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

HISTORICA L QUARTERLY Contents FALL 1995 / VOLUME 63 / NUMBER 4 IN THIS ISSUE 297 DECADE OF DETENTE: THE MORMONGENTILE FEMALE RELATIONSHIP IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY UTAH CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN 298 SO BRIGHT THE DREAM: ECONOMIC PROSPERITY AND THE UTAH CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION JEAN BICKMORE WHITE 320 STATEHOOD, POLITICAL ALLEGIANCE, AND UTAH'S FIRST U.S. SENATE SEATS: PRIZES FOR THE NATIONAL, PARTIES AND LOCAL FACTIONS EDWARD LEO LYMAN 341 ALL HAIL! STATEHOOD! AUDREYM GODFREY 357 IN MEMORIAM: C. GREGORY CRAMPTON, 1911-95 CHARI.ES S. PETERSON 370 BOOK REVIEWS 374 BOOK NOTICES 384 INDEX 386

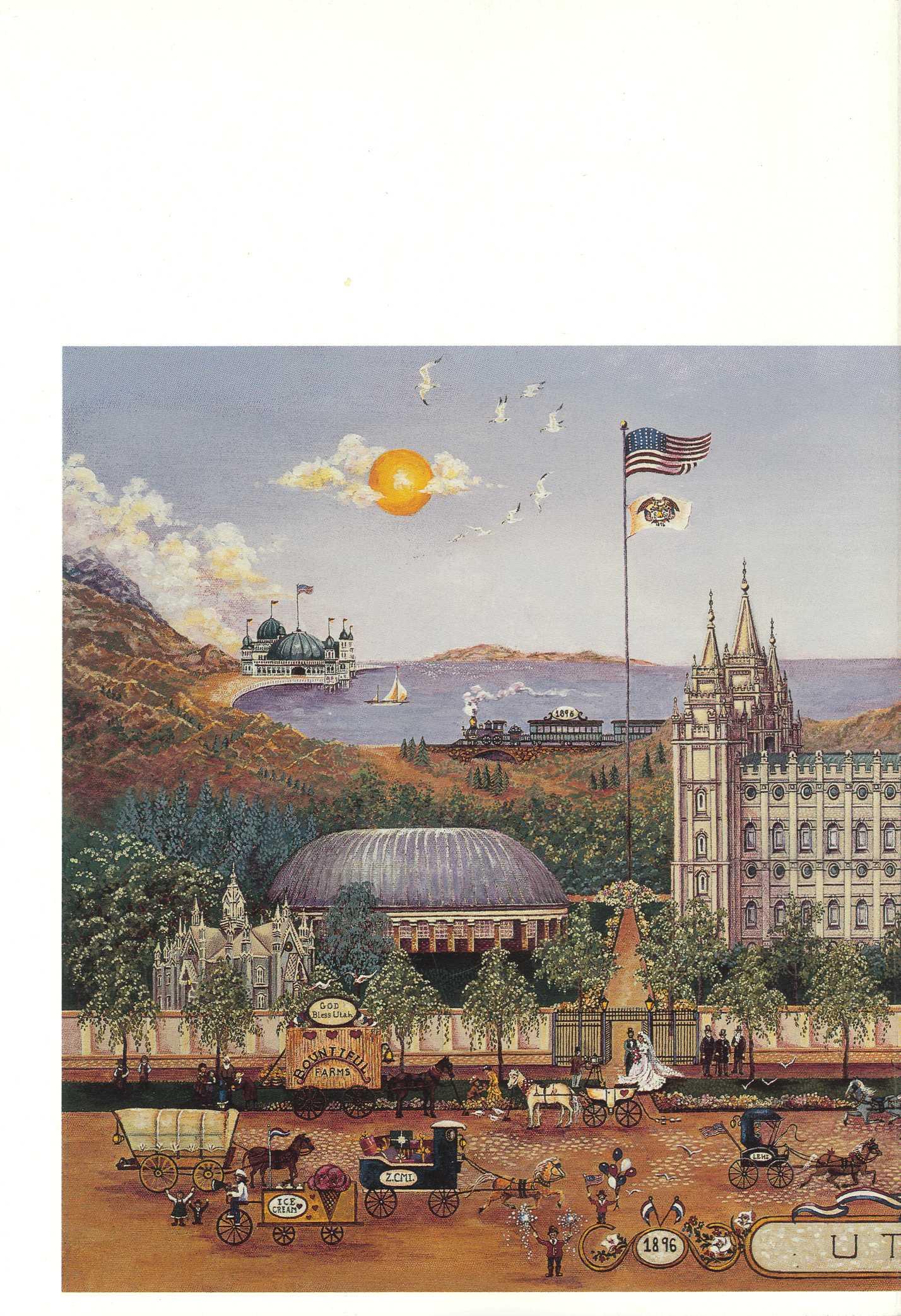

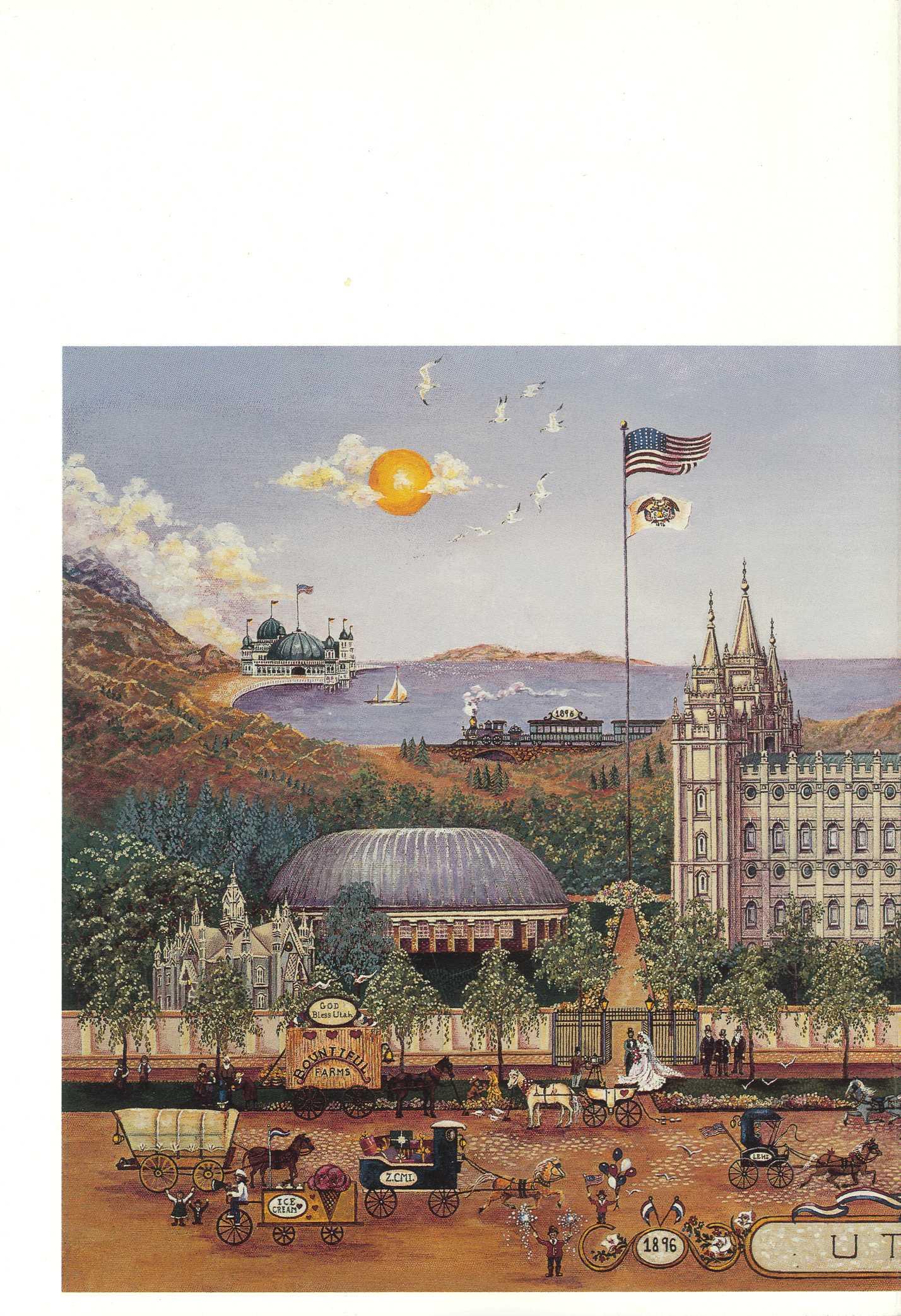

COVER Statehood

© Copyright 1995 Utah State Historical Society

THE

day painting by Jacque Baker, dedicated to the memory of herfather, Captain DeVere Baker of the Raft Lehi.

TOM TILL and BROOKE WILLIAMS Utah: A Centennial Celebration GARY PETERSON 374

LEONARD J. ARRINGTON Utah's Audacious Stockman: Charlie Redd. GARY L. SHUMWAY 375

DAVID B MADSEN and DAVID RHODE, eds Across the West: Human Population Movement and the Expansion of the Numa KAREN LUPO 377

LYMAN HAFEN. Roping the Wind: A Personal History of Cowboys and the Land W. PAUL REEVE 378

DEAN L MAY Three Frontiers: Family, Land, and Society in the American West, 1850-1900...RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS 379

ROGER D LAUNIUS and LINDA THATCHER, eds Differing Visions: Dissenters in Mormon History. .LOLA VAN WAGENEN 381

D MICHAEL QUINN The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power MELVIN T. SMITH 382

Books reviewed

In this issue

"Miss Utah comes into the Union bright and smiling," observed the Indianapolis Sentinel a century ago, and few assessments better summarized the popular mood within the 45th state on that festive occasion The long-awaited achievement of statehood on January 4, 1896, was a great climacteric in Utah history. Appropriately, we dedicate this issue of Utah Historical Quarterly to that centennial event

The first article analyzes the accommodation of Mormon and gentile women during the statehood decade, noting the types of differences that proved capable of mitigation and those that did not It is followed by a detailed look at basic issues decided during the Constitutional Convention that would set the tone and direction of the new state government. Then comes an interpretation of the politics of admission from a national perspective and the machinations behind the selection of Utah's first U.S senators A colorful description of the week-long statehood celebrations held throughout Utah's communities caps the thematic offerings It is succeeded by one of the Quarterly's periodic special features, a memorial tribute to a departed Lhstorical Society Fellow whom the historical community will greatly miss.

The publisher and readers of this commemorative issue owe special thanks to Jacque Baker, a local artist, for her generous donation of art for the cover This wonderful rendition of Salt Lake City in 1896 was recently purchased by Senator Orrin Hatch and now graces his Washington, D.C, office. Better than a thousand words, it captures the bright and smiling complexion of that memorable time in Utah history.

Looking north on Main Street, Salt Lake City, at about the time of statehood. USHS collections.

Looking north on Main Street, Salt Lake City, at about the time of statehood. USHS collections.

MMMM* a „-, vim, ,^„ <Tnn 77i£ Industrial Christian Home for Women, 145 South Fifth East, built as a refuge for Mormon women wanting to leave polygamous relationships, became a symbol of detente.

Little usedfor their original purpose, its rooms filled other needs. In the 1890s the Ladies Literary Club, which by then was seeking participation from leading IDS women like Emmeline B. Wells, held its meetings there. USHS collections.

Decade of Detente: The Mormon-Gentile Female Relationship in Nineteenth-century Utah

BY CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN

BY CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN

I N OCTOBER 1890 MORMON CHURCH PRESIDENT WILFORD WOODRUFF issued his Manifesto pledging to abide by the law of the land which had declared the practice of polygamy (correctly, polygyny) unconstitutional in 1879. Since the first public announcement of the practice among

:>~ must *_ » n u

Dr Madsen is professor of history and senior research historian with the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History at Brigham Young University.

Mormons in 1852, polygamy had created controversy and storms of social protest. The Manifesto, therefore, represented a victory not only for the federal government, and its repressive enforcement legislation, but for the moral conscience of thousands of women collectivized in a national "purity" crusade that had identified polygamy as a flagrant abuse of traditional moral values.1 For more than a decade before the Manifesto women throughout the country, at the instigation of non-Mormon women in Utah, denounced the religious practice of plural marriage and embarked on a self-imposed mission to awaken Mormon women to an awareness of their "moral degradation" and to demand legislation that would halt the offending practice. To arouse the nation and prick the conscience of Congress, women lectured, lobbied, petitioned, and published against the "moral blight" in Utah. They felt vindicated, therefore, with passage of the antipolygamy acts of 1882 and 1887which led to the Woodruff Manifesto in 1890.

Most studies of this volatile period have focused on Utah's long struggle for statehood and the Mormon capitulation to federal power that redesigned Utah's legal and political landscape.2 Few have explored woman's role, particularly in the period of social reconstruction that followed the Woodruff Manifesto. Easing the way to statehood, the Manifesto also became an overture to detente for Utah women. During the last decade of the nineteenth century Latterday Saint and gentile3 women blurred their former hostilities over polygamy and joined their common community interests in collective civic action. The decade clearly illustrates the significant impact of a distinct female cultural system based on shared values and the social power of its solidarity.4

1 Two studies that explore the uses of female moral authority are Ruth Bordin, Woman and Temperance: The Search for Poiuer and Liberty, 1873-1900 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1981), and Peggy Pascoe, Relations of Rescue, The Search for Female Moral Authority in the American West, 1874-1939 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990)

2 Standard studies are George S. Ellsworth, "Utah's Struggle for Statehood," Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (1963): 60-69; Howard R Lamar, "Statehood for Utah: A Different Path," Utah Historical Quarterly^ (1971): 307-27; Gustive O. Larson, The "Americanization" of Utahfor Statehood (San Marino, Calif.: Huntington Library, 1971); Gustive O Larson, "Government, Politics and Conflict," in Utah's History, ed. Richard D. Poll et al. (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978): pp. 243-56; and Leo Lyman, Political Deliverance: The Mormon Qiiestfor Statehood (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986)

s Mormon, Latter-day Saint, and LDS are identifying titles for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and will be used interchangeably throughout the paper; gentile was commonly applied by Mormons in the nineteenth century to non-Mormons in Utah

4 The merits of a separate and distinctive female "political culture" are discussed by Estelle Freedman in "Separatism as Strategy: Female Institution Building and American Feminism, 1870-1930," Feminist Studies 5 (1979): 512-29; Paula Baker, "The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780-1920," American Historical Review 89 (1984): 620-47; and Michael McGerr, "Political Style and Women's Power, 1830-1930," Journal of American History'77 (1990): 864-85

Decade ofDetente 299

After completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 more gentiles filtered into the remote Utah Territory as miners, military personnel, entrepreneurs, educators, and clerics Bringing their families with them, they established a small, diverse, non-Mormon population. United in their antipathy to polygamy, gentile women, through formation of an antipolygamy society in 1878 and publication of the Anti-Polygamy Standard two years later, made a visible and vocal stand against the practice. Their opposition was not only ideological but practical. In 1872 when the Mormon legislature abolished the dower right, a move that helped to equalize the claims of plural wives on their husband's estates, legal first wiveswere deprived of a common law protection.5 Also distressing was Utah's permissive divorce law.Although it prevented polygamy from being "a system of bondage" for plural wives, as explained in a defensive Deseret News article, it also made Utah an infamous divorce capital in the 1870s.6 Even woman suffrage, granted in 1870, merely entrenched Mormon political dominance and secured LDS practices, gentile women believed They vigorously campaigned for its repeal, willing to lose their own franchise in order to lessen the political imbalance in Utah Congress responded by repealing woman suffrage in Utah as a provision of the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act.

The Manifesto thus became a prelude to conformity with American political and legal tradition and helped redefine the parameters of female community in Utah. The "tendency toward female association," which had budded early in the century into religious and benevolent societies, flowered by the end of the century into secular cultural clubs and reform organizations. These associations brought women together in collective efforts for self-improvement, philanthropy, and social welfare. They also facilitated women's entry into the public realm and gave their members a growing share of public influence as they transformed social needs into public policy.7 The

5 The dower right provided a widow whose husband died intestate with a one-third interest in his real property and before his death an inchoate one-third interest

6 A Deseret Weekly News article, "Divorce," October 3, 1877, explains the position of the LDS church towards divorce Though the law had been in effect since 1852, its liberal grounds and residency provisions brought hundreds of divorce-seekers to Utah after completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 For more information about how Utah law accommodated the practice of plural marriage see Carol Cornwall Madsen, "'At Their Peril': Utah Law and the Case of Plural Wives, 1850-1900," in Western Historical Quarterly 21 (1990): 425-44

7 Barbara Leslie Epstein analyzes this transition in The Politics of Domesticity, Women, Fvangelism, and Temperance in Nineteenth Century America (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1981), as does Karen J Blair in The Clubwoman as Feminist: True Womanhood Redefined, 1868-1914 (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1980)

300 Utah Historical Quarterly

challenge that lay before Utah women after the Woodruff Manifesto was how to make their common female community interests bridge the chasm polygamy had created. For a decade their enthusiasm to join the surge of associated female activity that had swept the country elsewhere muted the strident chords of the recent conflict

Until the Manifesto the public activities of Utah women had followed different tracks. Both LDS and gentile women responded to the welfare needs of their own religious groups by organizing benevolent and social aid societies. LDS women attacked social problems through the Relief Society, which had flourished throughout the church since 1867, dispensing Christian charity, instructing its members in economic self-reliance, and promoting home industries, notably the processing of silk and the merchandising of home-crafted products.8

Though their numbers were far fewer, Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish women in Utah used their women's associations to help establish hospitals, to organize nurses' training programs, and to provide a variety of benevolent and social services In 1884 Baptist women organized a Ladies Aid Society for charitable service along with Sunday Schools and Christian Endeavor Societies to promote Christian principles. Emma Parsons, who directed the Sunday School, also gave temperance lectures. Several other Baptist women organized a Loyal Temperance Union.9 Temperance was a major goal of women's reform associations, following the lead of the immensely popular Woman's Christian Temperance Union. The Congregationalists organized a sewing school for young women along with a benevolent society. During one period they sponsored four charitable societies to provide help for "any whom we find in need" regardless of denomination. The Women's Society of the Methodist Church was active in recruiting teachers and social workers and sponsored two boarding houses for women as well as a home for girls. The Presbyterians organized a Ladies Aid, a Women's Missionary Society, and a Young People's Society of Christian Endeavor.10

8 The Relief Society was originally organized in Nauvoo, Illinois, in 1842. It was disbanded two years later In 1854, seven years after the church had settled in Utah, several ward Relief Societies were organized in Salt Lake City, but not until 1867 was the Relief Society organized throughout the church For a review of the various charitable organizations developed during this period see Emmeline B Wells, Charities and Philanthropies: Woman's Work in Utah (Salt Lake City, 1893). See also Kate B. Carter, "Men's and Women's Societies, Clubs and Associations," pamphlet, Daughters of the Utah Pioneers lesson for February 1950, pp 209-52

9 R Maude Dittmar, "A History of Baptist Missions in Utah, 1871-1931" (M.A thesis, University of Colorado, 1931), p 44

10 Carter, "Men's and Women's Societies," p 219; see also John Sillito and Constance Lieber, "A Heritage of Conflict, Women and Religion in Utah, 1847-1920," paper in possession of author, pp 15-20

Decade ofDetente 301

Establishing one of the earliest hospitals in Utah marked the major community service of the Episcopalians in 1871 Staffed and directed by women, it also supported a nurses training school. The Catholics also opened a hospital as well as an orphanage, and Catholic Charities became a substantial and enduring benevolent organization in Utah.Jewish women, who constituted one of the smallest of the women's groups in Utah, were among the first to organize a benevolent society in the late 1860s, and theJewish community enjoyed the assistance of several Christian denominations in building its synagogue. 11 Thus, even as the divisive antipolygamy campaign convulsed Utah, some of the public activities that united community women across religious boundaries elsewhere also flourished in Utah but along denominational lines.

With the official retreat of polygamy, however, women were quick to forge inclusive bonds. They took their impetus for united effort from national as well as local social issues, rapidly discovering the impact of female collectivity. One significant area of detente was politics, which required a major shift in loyalty and political practice. For women it was especially difficult Lingering traces of hostility from the antipolygamy campaign complicated initial efforts to form a grass-roots movement to reclaim the vote in 1889. With only a few exceptions, gentile women, still apprehensive about Mormon political domination, refused tojoin. They registered a second protest in 1895 during the debate on woman suffrage in the Utah Constitutional Convention.12 However, after woman suffrage was voted into the Constitution, old resentments diminished and politics became a social arena which made allies of former political foes.13

New political coalitions had earlier been formed when the local People's (Mormon) and Liberal (gentile) political parties disbanded in favor of the national parties in 1891.14 With female suffrage guaranteed by the new state constitution, the two political parties eagerly courted women to their ranks and included them on every level of organization, recognizing their potential political power. Though most gentile women favored the Republicans and LDS women the

11 Carter, "Men's and Women's Societies," p 226; Sillito and Lieber, "A Heritage of Conflict," pp. 32, 34. For data on the early settlement of Jews in Utah see Leon L. Watters, The PioneerJews of Utah (New York: American Historical Society, 1952)

12 Jean Bickmore White gives a full account of this debate in "Woman's Place Is in the Constitution: The Struggle for Equal Rights in Utah in 1895," Utah Historical Quarterly 42 (1974): 344-69

13 This transition is discussed in the sources cited in footnote 2

14 The Liberal party did not fully disband for another two years, having met moderate success at the ballot box

302 Utah Historical Quarterly

Democrats, some resisted the trend and joined the other party For the first time women found themselves in the same political camp as their former opponents, campaigning, fund-raising, and rallying together for their respective parties, and even running for office on the same ticket. These new political configurations broke through the long-standing religious alignment. The triumph of politics over religion became evident in the results of the first state election in which women could vote. The party affiliation, not the religious, determined the winners. Both Mormon and non-Mormon women were elected to the state legislature and various county offices.15

After regaining the vote with statehood, Utah women supported the newly organized Utah Council of Women, which superseded the former territorial suffrage association. At the request of Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, the Utah Council of Women was organized to aid other states in their suffrage quest. Utah women representing all faiths and both political parties joined the Council and remained active until November 1920 when the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified giving the franchise to all women in the nation.16

While Utah women were debating party politics they were also engaged in another pursuit, once a major point of discord but rapidly becoming an element of conciliation Education had been one of the earliest fronts on which the Mormon-gentile battle was fought in Utah At settlement the LDS church established ward schools throughout the territory, with instructors selected from among the settlers and tuition charged to remunerate the teachers and maintain the schools. The parochial schools, established by the gentile denominations in the 1870s and supported by national religious and educational associations, challenged the LDS school system by offering trained teachers, modern pedagogical methods, and free tuition, factors that attracted many LDS children.17 Both systems labored to inculcate their own values. Gentile teachers approached

''Jean B White, "Gentle Persuaders, Utah's First Woman Legislators," Utah Historical Quarterly 38 (1970): 31-49. It is ironic that during this period of Mormon-gentile detente politics became a divisive factor in LDS sisterhood The entrance of Utah women into party politics is discussed in Carol Cornwall Madsen, "Schism in the Sisterhood: Mormon Women and Partisan Politics, 1890-1900," in Davis Bitton and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, eds., New Views of Mormon History, Fssays in Honor of LeonardJ. Arrington (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1987), pp 212-41

16 Susan B Anthony and Ida Husted Harper, eds., The History of Woman Suffrage, 6 vols (Rochester, N.Y: Susan B Anthony, 1902), 4:949-50; 6:644-50

" Attendance figures for the Ogden Academy, for example, compiled by the Congregationalsponsored New West Education Commission which supported a teaching mission in Utah, indicate that Mormon enrollment ranged from 26 to 74 percent of the total studentbody over a five-year period in

Decade of Detente 303

their work in Utah with missionary zeal, and indeed many were sent to Utah expressly commissioned to dissuade young Mormons from engaging in plural marriage For two decades LDS leaders had consistently opposed a free territorial public school system, reluctant to surrender control of curriculum and personnel in the ward schools.18 Antipolygamy laws in the 1880s and a growing gentile political power, however, led the legislature in 1890 to finally adopt a taxsupported public school system for the entire territory Another major barrier to rapprochement fell, and while both parochial and LDS-supported schools persisted, public school educators could join forces and shift their attention toward providing adequate public schooling for all Utah children.19

The time also seemed propitious to join the popular national kindergarten movement which had interested many Utah women since the 1870s. Camilla C. Cobb, adopted daughter of Utah educator Karl G. Maeser and a trained teacher herself from Dresden, Germany, introduced kindergartens to Utah in 1874. She had learned the early childhood educational principles of the famed Dr Friedrich Froeble and applied them in her teaching.20 Though meeting some initial apathy, she set up a small school "in the vestry of President Brigham Young's old schoolhouse inside the Eagle Gate." Her first pupils were her own children and those of John W. Young, son of Brigham Young.21 The spirit of kindergarten work proved infectious and small

the 1880s (See Annual Reports of the New West Education Commission, 1885-1890, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.) Additional information on the development of public education in Utah can be found in Clyde Wayne Hansen, "A History of the Development of Non-Mormon Denominational Schools in Utah" (M.S thesis, University of Utah, 1953); Stanley S Ivins, "Free Schools Come to Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly 22 (1954): 321-42; C Merrill Hough, "Two School Systems in Conflict: 1867-1890," Utah Historical Quarterly 28 (1960): 113-30; Charles S Peterson, "A New Community: Mormon Teachers and the Separation of Church and State in Utah's Territorial Schools," Utah Historical Quarterly 48 (1980): 293-312

18 A discussion of Mormon opposition to public school education on ideological grounds is Allan Dean Payne, "Mormon Response to Progressive Education" (Ph.D diss., University of Utah, 1977)

'•' Although private LDS and other denominational schools continued to operate, the tax-based public school system naturally removed numerous students from private schools, forcing the closure of many of them The LDS Church Education System, however, maintained its interest in the education of Zion's youth by establishing academies, junior colleges, and extra-curricular religion classes

20 This German educator (1782-1852), deeply influenced by Pestalozzi, an earlier educational innovator, is noted for his interest in early childhood development which led to the establishment of the first kindergarten or "garden of children." His educational philosophy was based on his belief that "all education not founded on religion is unproductive" and his conviction that the function of education is to develop the faculties by stimulating voluntary activity or, in the case of children, play He devised various activities for children designed to strengthen their bodies, exercise their senses, and challenge their minds.

21 Mrs C D Fox, "A Life Dedicated to Kindergarten Work," in Kate B Carter, comp., Treasures of Pioneer History, 6 vols (Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1952-57), 1:59-62; see also "The Pioneer Kindergarten," Woman'sFxponent 25 (April 1, 1897): 124

304 Utah Historical Quarterly

independent kindergartens sprang up after Cobb's model Anna Elizabeth Richardson Jones and Elizabeth Dickey were among the first Protestant women in Utah to develop kindergartens, Jones opening a private school in 1880 and Dickey, through the auspices of the Presbyterian Women's Executive Board of Commissioners, in 1883.22 It was logical for the new kindergartens in Utah to be religiously sponsored because of their strong focus on moral training and the educational philosophy of their founder, Dr. Froeble.23

To better support the growing movement and secure funding and personnel, LDS and gentile educators formed city and territorial associations, but independent of each other In 1892 Mrs E H Parsons, a Baptist, organized the Salt Lake Kindergarten Association which imported a trained teacher to set up a kindergarten for children and a teacher training class for young women. The association also lobbied the legislature to grant local school boards the option to open kindergartens in their districts. Two years later, needing a stronger support base, the association enlisted the help of the city's women's clubs. At a meeting with the Ladies Literary Club, the Free Kindergarten Association was formed with educator Emma McVicker as president. That year the association sponsored the services of Alice Chapin of Boston, an expert in kindergarten training, who opened a training school and model kindergarten in the First Congregational Church parlors in Salt Lake City. She was well received by both Mormon and gentile teachers, who later attended her kindergarten training classes at the L^niversity of Utah.24

Sensing a competitive spirit in the flurry of interest in kindergarten training and mindful of the apparent lead taken by non-LDS women in the movement, LDS church leaders enthusiastically supported the organization of an LDS association in 1895 spearheaded by Sarah Kimball, Isabella Home, Elmina Taylor, Zina D. H. Young, Bathsheba W. Smith, and Ellis Shipp, all of them known more for their work in LDS women's associations than in education. They organized the Utah Kindergarten Association with a slate of officers that included seventeen directors and nine members of an advisory

22 Marie Fox Felt Papers, Histoiy of the Kindergarten, fid 4, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah

2:1 A brief discussion of the kindergarten movement as one aspect of social reform is William Leach, True Love and Perfect Union: The Feminist Reform of Sex and Society (New York: Basic Books, 1980), pp 331-34

24 Felt Papers; Journal History of the Church, June 18,1894, pp 4-5, LDS Church LibraryArchives

Decade ofDetente 305

board, six of whom were the organizers. Three kindergartens were opened soon thereafter under the auspices of the association as well as a training class for teachers taught by Anna R Craig of the Brigham Young Academy, ironically, a non-Mormon. She was assisted by Nettie Maeser and Emmeline Y Wells (not to be confused with Emmeline B. Wells), two strong Mormon advocates of the program. With the association's backing, other women, including Louie B. Felt and May Anderson, leaders of the LDS children's Primary Association, also tried their hands at teaching kindergarten while introducing some of its philosophy into the Primary.25

By 1896 the overlap of goals and methods, mutual need for funding and lobbying power, and the new spirit of detente prompted the two associations to merge. Officers elected at the first annual meeting of the combined groups represented a cross section of men and women, Mormon and gentile, and professional and volunteer, all dedicated to establishing kindergartens in Utah. Their parochial interests were submerged in their mutual enthusiasm for early childhood education and the establishment in Utah of the progressive methods popular elsewhere in the country. The circular announcing the formation of the association was signed by representatives of all of the religious groups in Utah, indicating their continuing stake in education The newly organized Utah State Kindergarten Association, assisted by the lobbying committee of the Utah Federation of Woman's Clubs, obtained legislation in 1898 providing funds for a state kindergarten training school at the University of Utah, and additional legislation in 1903 provided that at least one kindergarten be opened and maintained in every town in Utah of 2,500 inhabitants.26 During the remainder of the century Utah kindergarten women attended national conferences together, engaged the services of prominent educators, and planned numerous fund-raising socials, all as progressive women of Utah.

The local kindergarten movement, along with varied other educational and civic projects, was given a strong boost when the Utah Federation of Woman's Clubs was organized in 1893. Utah women had already experienced the support and visibility provided by affiliation with local, state, and national levels of women's associations,

25 Journal History of the Church, August 23, 1894, p 4; May 6, 1895, p 2; September 7, 1895, p 5; September 13, 1895, p 6; December 24, 1895, p 8

26 Mary B Fox, Director of Kindergarten, State Normal School, "The Practical Value of Kindergarten," Utah Lducational Review 1 (October 1907): 21-22

306 Utah Historical Quarterly

such as the National American Woman Suffrage Association, National Council of Women, and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union. Thus, when Charlotte Emerson Brown, first president of the General Federation of Woman's Clubs, urged her niece, Antoinette Brown Kinney of Salt Lake City, a member of the non-Mormon Ladies Literary Club, to organize a state federation, Kinney was quick to respond In April 1893 the Utah Federation was organized with six participating clubs, the second state/territory to federate.27

The club movement, which proliferated throughout late nineteenth century America, had penetrated Utah in the 1870s. Gentile women were the first to adopt social clubs in Utah.28 In 1875 Jennie Froiseth, who was at that time a leader in the antipolygamy cause, having brought national club woman Julia Ward Howe into the antipolygamy crusade as an ally, accepted Howe's suggestion to organize non-LDS women into the Blue Tea Club, so named by Howe.29 A difference in objectives among the members resulted in an offshoot club, the more popular Ladies Literary, with which the Blue Tea later merged. The Ladies Literary Club is credited with being Utah's first woman's club. It restricted its membership, claiming to be "an avowedly exclusive club for intellectual food and companionship."30

Other than the records of a Utah chapter of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, organized in 1883, there is no evidence of additional clubs until the 1890s when a burst of organizing occurred. From 1890 to organization of the State Federation in 1893 at least eight women's clubs came into being: La Coterie of Ogden (1890); the Nineteenth Century Club of Provo (1890); the Utah Women's Press Club (1891); the Cleofan and the Reapers (1892); the Authors Club of Salt Lake City, the Aglaia of Ogden, and the Woman's Club

27 Mrs J C Croly, The History of the Woman's Club Movement in America (New York: Henry G Allen & Co., 1898),'p H12

28 An exception might be the Philomathean Club, organized in Payson, Utah, in 1872 One extant newsletter, The Philomathean Gazette, dated December 23, 1872, is available in Special Collections, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo I am indebted to Alyson Rich Jackson for drawing my attention to this source.

29Julia Ward Howe was an inveterate club woman, In 1871 she presided over the New England Woman's Club, one of the country's first woman's clubs, and helped found the General Federation of Woman's Clubs in 1889, serving as a director from 1893 to 1898 The Blue Tea took its name from the term "blue stocking," given to literary women in England a century earlier and the "dainty pink teas" they sponsored See Katherine B Parsons, History ofFifty Years, Ladies Literary Club, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1877-1927 (Salt Lake City: Arrow Press, 1927), pp 22-24

30 Parsons, History ofFifty Years, pp 2-24 See also Journal History of the Church, April 27, 1917, pp 7-8 Papers of the two clubs are housed in Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah

Decade ofDetente 307

of Springville (1893).31 That women in smaller, rural areas also joined the organizing bandwagon is very likely, their records, if any, probably passing informally to each succeeding officer In 1892, capitalizing on the nation-wide organizational craze, Olive Thorne Miller, a national writer, prepared "a practical guide and hand book" for inexperienced club women entitled The Woman's Club. It not only offered suggestions for every conceivable type of organizational pattern, it also preached the philosophy of club work, particularly applicable to Utah. "Cooperation," she wrote, according to a review of the book in the Woman's Exponent, "uplifts as well as harmonizes those elements in society and in home life that are otherwise left to individual cultivation or restraint and by mutual effort and sympathy much greater benefit to all must necessarily follow."32

With the help of Corinne M. Allen of the Ladies Literary Club and Nora M. Jones of the Provo Nineteenth Century Club, Antoinette Kinney called a statewide organizational meeting to which seven clubs and twenty-three delegates responded. Six clubs, both Mormon and gentile, elected to join the new federation: the Ladies Literary Club, the Salt Lake Woman's Club, the Nineteenth Century Club, La Coterie, the Cleofan Club, and the Utah Women's Press Club.33

Almost immediately the new federation developed programs to improve the social landscape of Utah. Its objective reflected the selfappointed role that club women were assuming in communities throughout the nation: "To bring into communication with one another the various women's clubs in Utah, that they may compare methods of work and become mutually helpful . . . and in general to promote such measures as shall best advance the educational, industrial, and social interest of the State."34 Though women's clubs, initially literary and cultural, were characterized as "post school education," their increasingly external focus on the state and national levels redefined them as influential agents for civic improvement and social change. Not as directly self-serving as some other national

31 Utah Federation of Woman's Clubs, Program Yearbook for 1908, p 6, Special Collections, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University There were undoubtedly other local clubs that did not join the federation or preserve their records in known repositories

' "The Woman's Club," Woman's Exponent 20 (October 1, 1891): 53 The Woman's Exponent was an LDS women's publication from 1872 until 1914

33 Adelia Knudsen, "History of the Utah Federation of Women's Clubs, 1893-1952," typescript copy, Utah State Historical Society Library, Salt Lake City See also Croly, The History of the Woman's Club Movement, pp 1108-17

54 Knudsen, "History of the Utah Federation of Women's Clubs."

308 Utah Historical Quarterly

women's associations, they were devoted less to promoting woman's status than to the development of community welfare. While individual clubs in Utah maintained their own cultural and philanthropic agendas, collectively they lobbied for libraries, kindergartens, public parks and playgrounds, protective legislation for women and children, juvenile courts, and preventive health measures. They also organized sub-committees within their individual groups to investigate other community needs.35 Their combined strength and the solidarity of their shared commitments gave them a prominent public presence

The federation not only brought the segregated clubs into collective effort in behalf of the community, but it also engendered social relationships as women found common interests and friendships that subordinated their religious identities.36 A garden party in 1893 introduced gentile guests Margaret Salisbury, Isabella Bennett, and the Honorable Aurelius Miner and his wife to the largely LDS membership of the Territorial Suffrage Association, the Utah Women's Press Club, and the Reapers Club, whose members had arranged the party.37 The social coup for a number of LDSwomen was an invitation to attend a meeting of the exclusive Ladies Literary Club held, ironically, in the former Industrial Christian Home for Women, a prodigious symbol of their former antagonism.38 Emmeline B.Wells, one of the fortunate few, observed, "Some years ago, no Mormon could be admitted as visitors even, but now things are different—we [Mormon women] are sought after We are getting more recognition and stand more on an equality with other women than formerly."39

The 1896 convention of the State Federation of Woman's Clubs was a model of congeniality. Euretha K. Barthe established the tone of cooperation in her welcoming address. Hailing the large gathering of women, "the first and largest assemblage of women in the new State" (statehood had occurredjust six months earlier), she charged

35 Utah Federation of Women's Clubs, Yearbook for 1908, p 6

36 Several non-Mormon women joined the Mormon-organized Utah Women's Press Club or participated in its activities after 1895 See Woman's Exponent 24 (June 15, 1895): 12; 25 (June 1, 1896): 18; 25 (December 15, 1896): 73 Mormon women had already begun affiliating with the Ladies Literary Club; and the Cleofan and Nineteenth Century Clubs, in particular, diversified their membership

:" Woman's Exponent 22 (August 15, 1893): 20.

38 Established by Congress at the instigation of Angie Newman, an avid antipolygamist crusader, for refuge and rehabilitation of disillusioned polygam3us wives, the Industrial Christian Home for Women failed to attract sufficient clients to maintain iti. original purpose See Pascoe, Relations of Rescue, pp. 24-?>\, 87-90.

39 Emmeline B. Wells, Diary, January 26, 1894, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah

Decade ofDetente 309

the federation to "secure us leadership in matters now pressing for action in our State We represent the women of Utah," she affirmed, "of diverse ages, tastes and faith, banded together by common interest in all that pertains to the advancement and progress of women."

Dr. Romania B. Pratt, a Salt Lake City doctor, compared the Reapers Club, which she represented, to a small brook swept into the larger stream of the General Federation, "helping to create a mighty force of woman power" that would refine and improve the world.40 Like the social purists of an earlier decade, club women little doubted the potential of their collective action.

The appeal of federation enticed twenty-three additional women's clubs, both Mormon and gentile, to join before the end of the century, their members serving together on committees and participating at the annual conferences. Through these associations, with their civic agendas, Utah women united to express their female interests under the umbrella of public service and reform Associated effort, they discovered, gave women social impact, while petitioning and lobbying, political tools of the disfranchised, became even more effective in the hands of the politically empowered. The "Collect for Club Women," the federation's statement of purpose, professed the commonality of women's social culture as defined by the club movement. "May we strive to touch and to know the great common woman's heart of us all," the motto read That "the great common woman's heart" often found diverse objects for its loyalty and affection perhaps prompted the concluding caution: "Let us not forget to be kind." If Utah women could not experience total unity in addressing the issues and challenges of their common social environment, for a decade they were able to find some consensus in their diversity

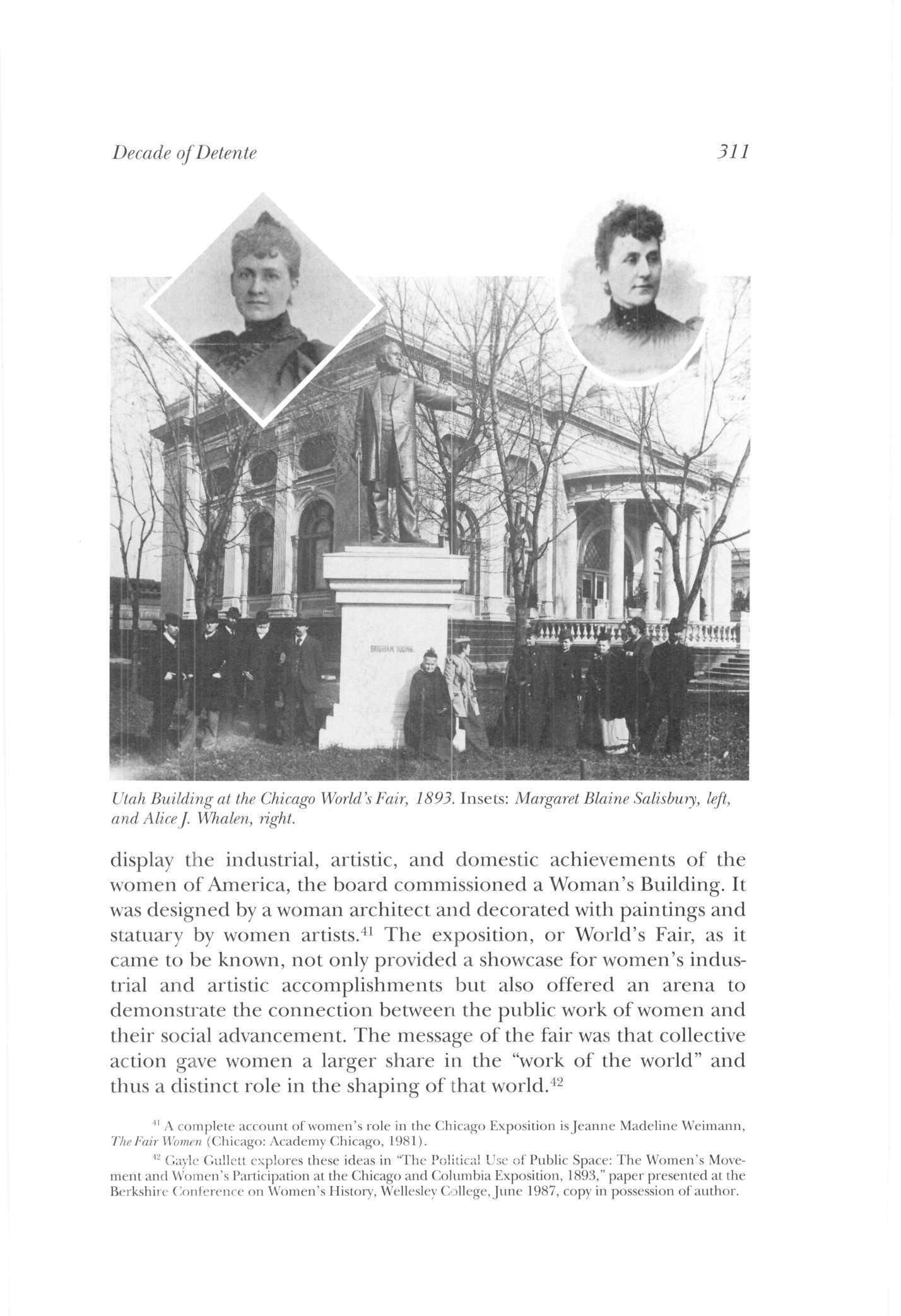

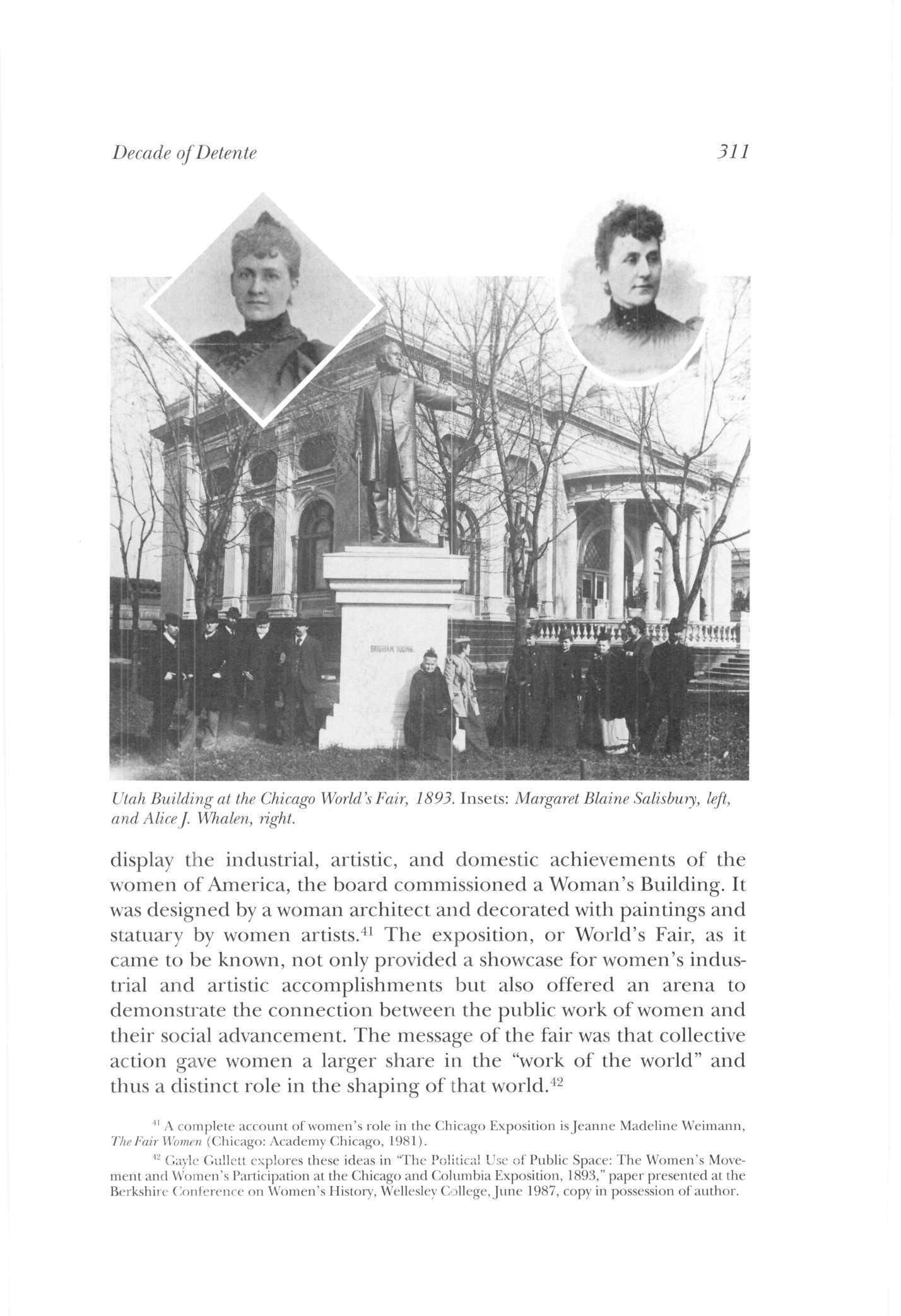

Of all the avenues to detente, the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago claimed the highest degree of cooperative effort among the largest number of Utah women. In fact, it was a major catalyst for associational activity among women across the country The creation of a Woman's Department within the administration of the exposition, with a separate Board of Lady Managers, invited female representation at the grand celebration (a year late) of Columbus's arrival in the New World and America's growth as a nation. The national Board of Lady Managers was replicated in every state and territory with representatives from each constituting the national board. To

310 Utah Historical Quarterly

40

"Utah Federation of Woman's Clubs," Woman's Exponent 25 (June 1896): 1, 2

display the industrial, artistic, and domestic achievements of the women of America, the board commissioned a Woman's Building. It was designed by a woman architect and decorated with paintings and statuary by women artists.41 The exposition, or World's Fair, as it came to be known, not only provided a showcase for women's industrial and artistic accomplishments but also offered an arena to demonstrate the connection between the public work of women and their social advancement The message of the fair was that collective action gave women a larger share in the "work of the world" and thus a distinct role in the shaping of that world.42

41 A complete account of women's role in the Chicago Exposition is Jeanne Madeline Weimann, The Fair Women (Chicago: Academy Chicago, 1981)

42 Gayle Gullctt explores these ideas in "The Political Use of Public Space: The Women's Movement and Women's Participation at the Chicago and Columbia Exposition, 1893," paper presented at the Berkshire Conference on Women's History, Wellesley College, June 1987, copy in possession of author.

Decade of Detente 311

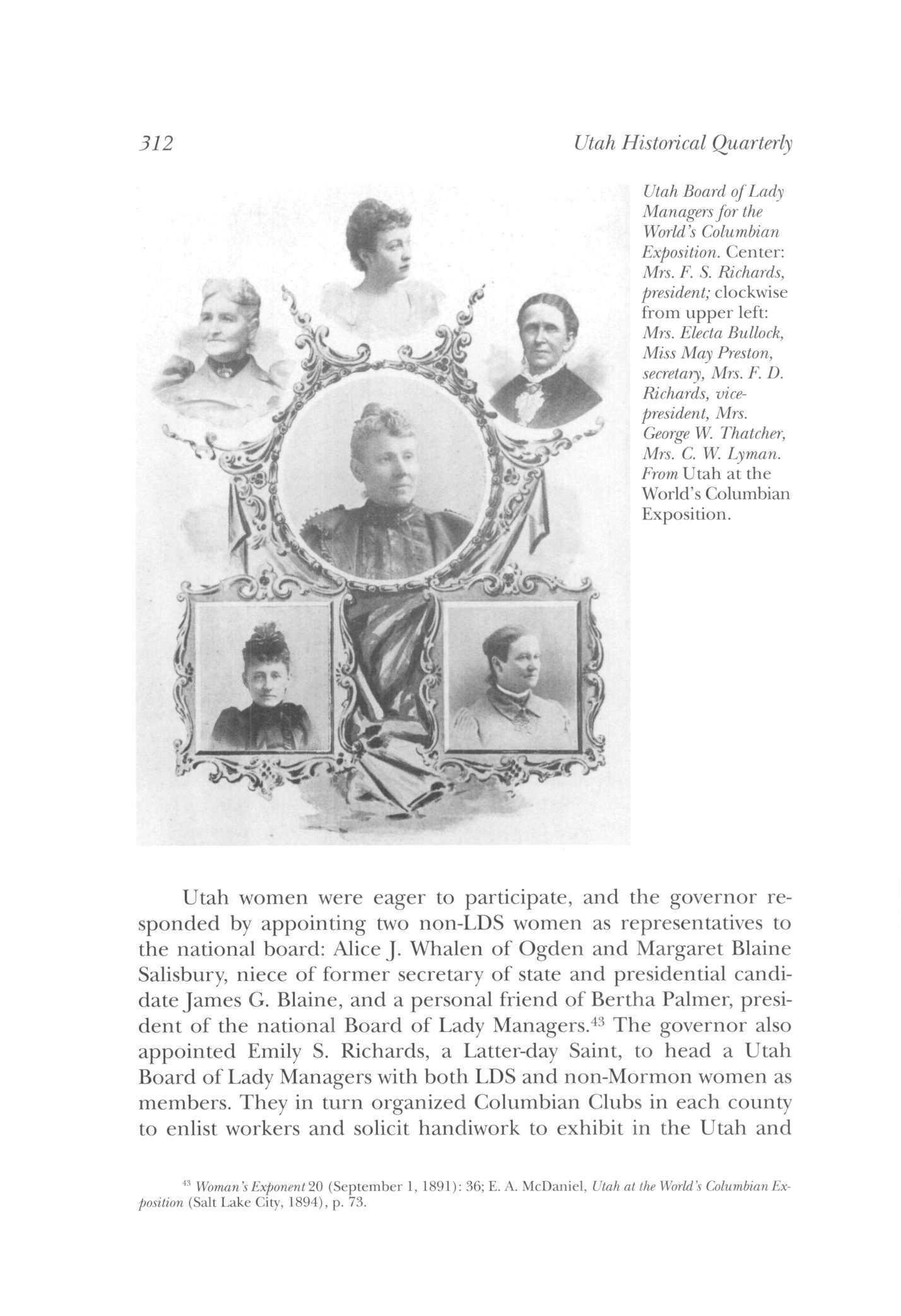

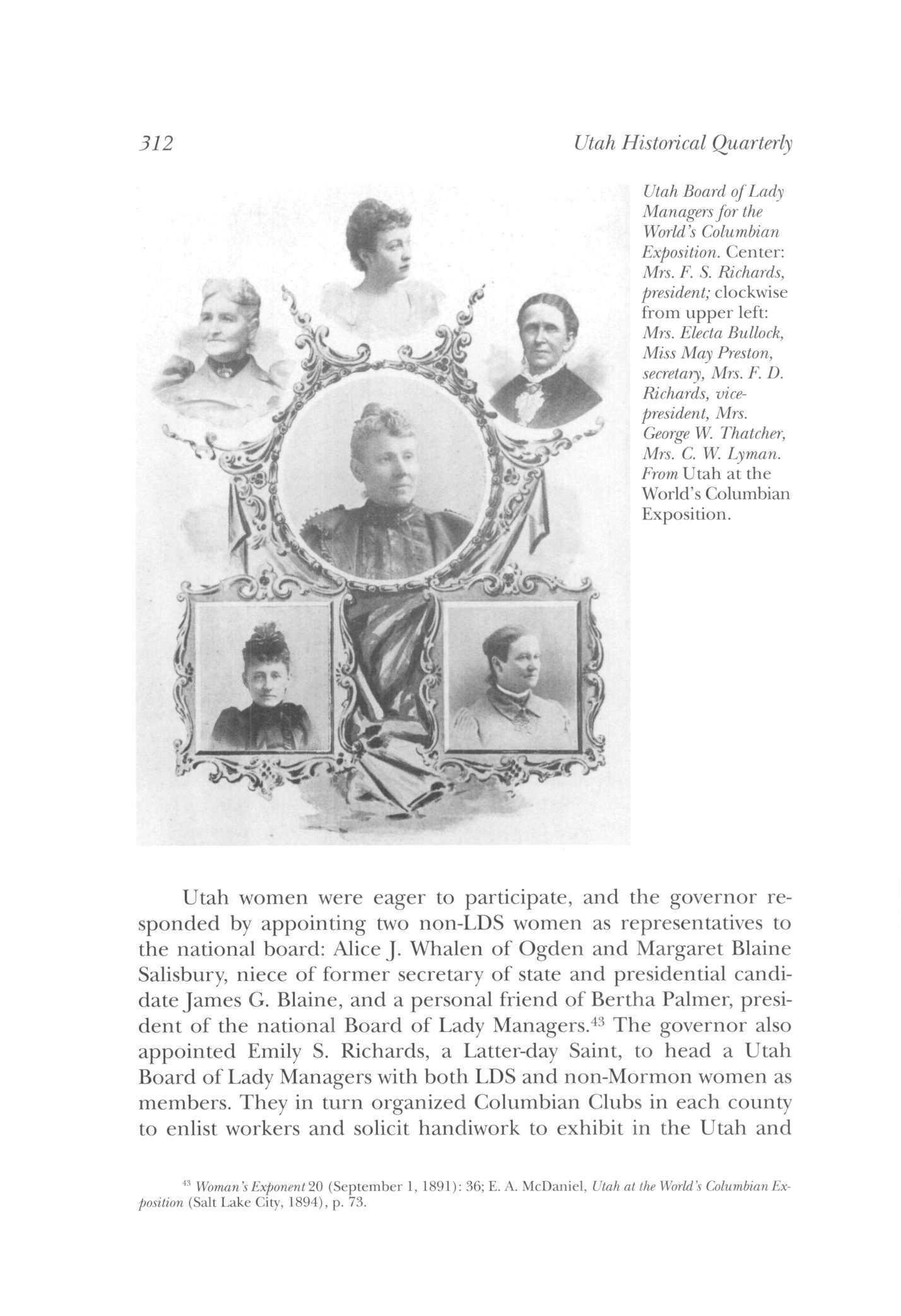

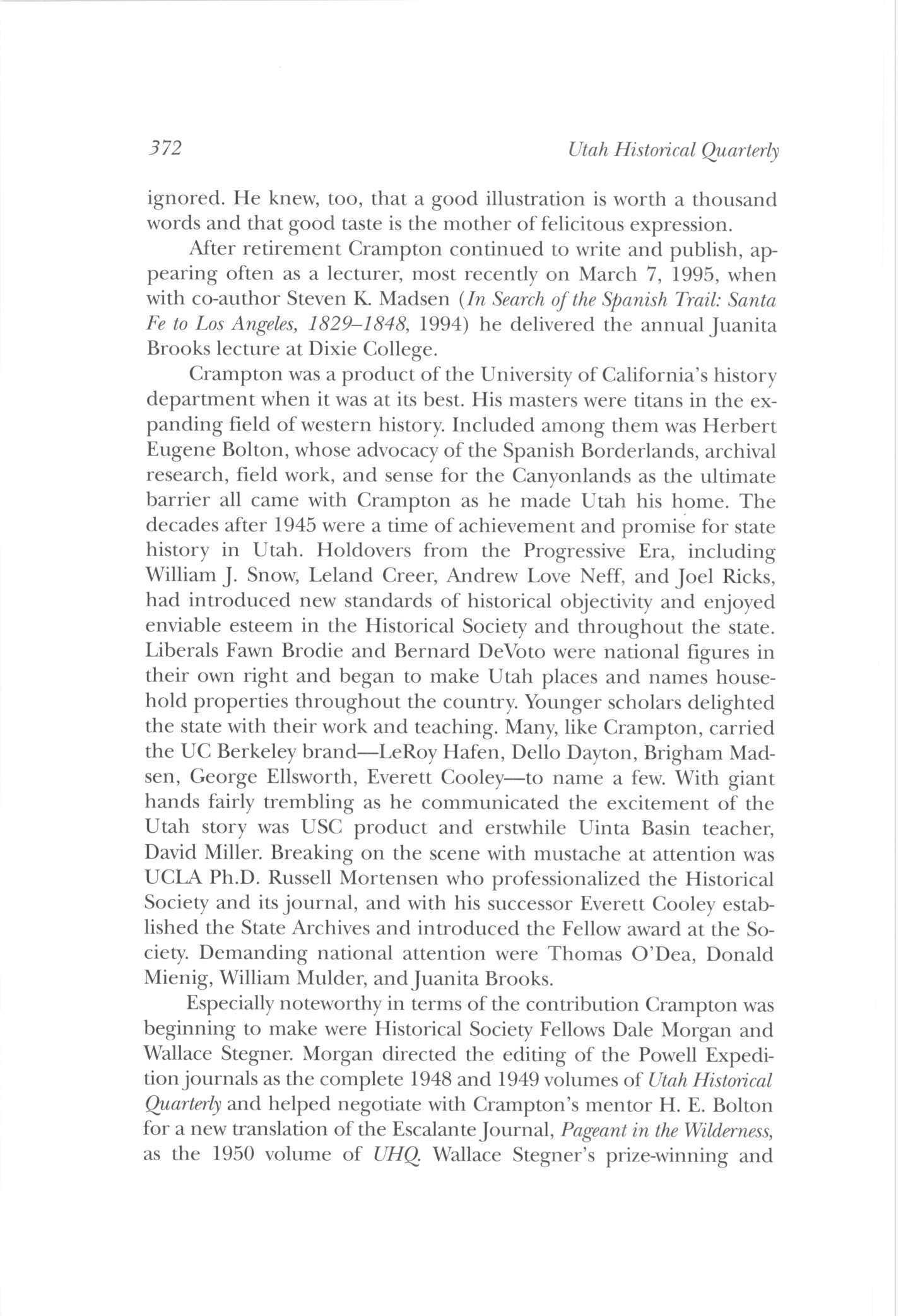

Utah Building at the Chicago World's Fair, 1893. Insets: Margaret Blaine Salisbury, left, and AliceJ. Whalen, right.

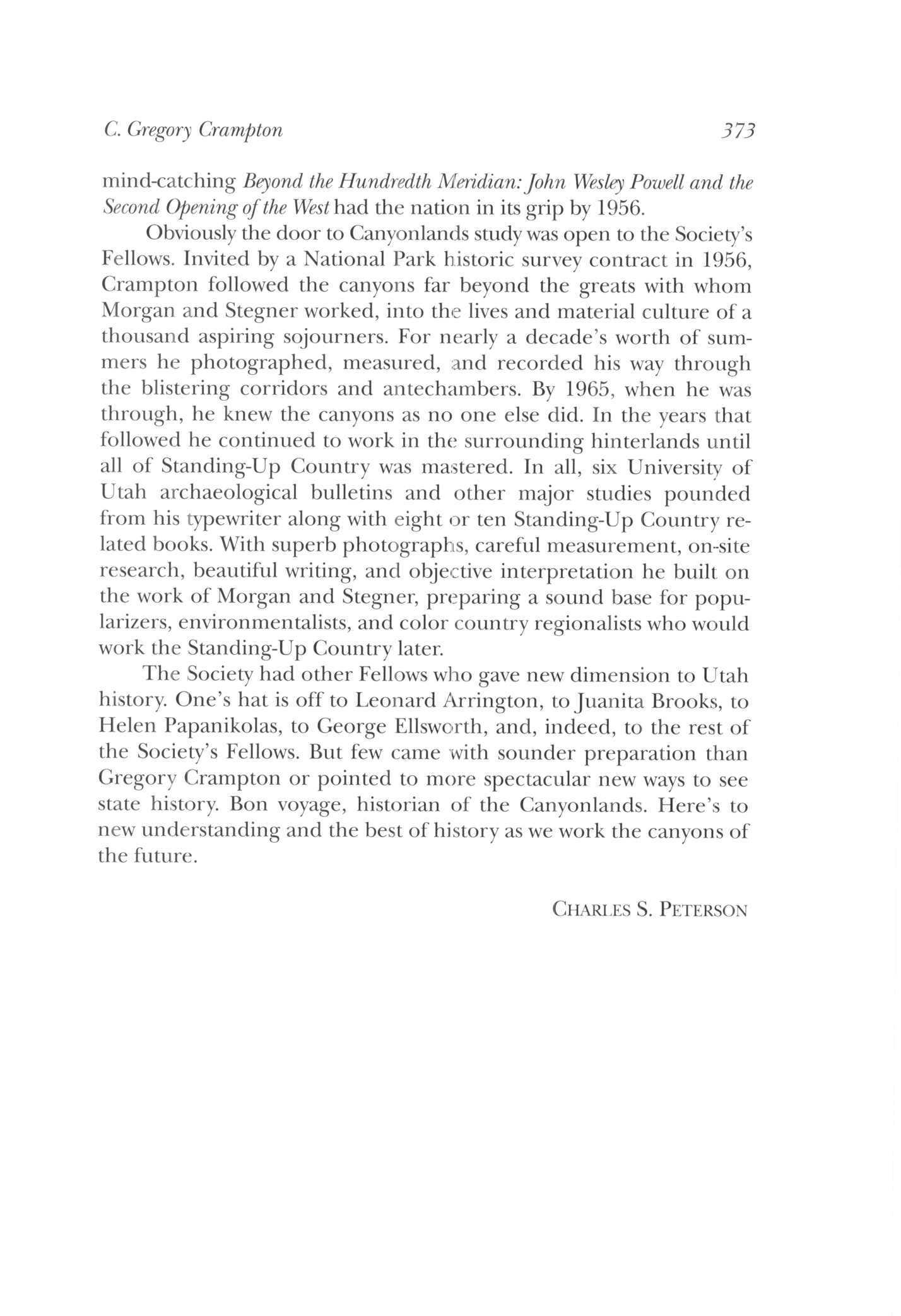

Utah Board of Lady Managersfor the World's Columbian Exposition. Center: Mrs. F. S. Richards, president; clockwise from upper left: Mrs. Electa Bullock, Miss May Preston, secretary, Mrs. F. D. Richards, vicepresident, Mrs. George W. Thatcher, Mrs. C. W. Lyman. From Utah at the World's Columbian Exposition.

Utah women were eager to participate, and the governor responded by appointing two non-LDS women as representatives to the national board: Alice J. Whalen of Ogden and Margaret Blaine Salisbury, niece of former secretary of state and presidential candidate James G. Blaine, and a personal friend of Bertha Palmer, president of the national Board of Lady Managers.43 The governor also appointed Emily S. Richards, a Latter-day Saint, to head a Utah Board of Lady Managers with both LDS and non-Mormon women as members. They in turn organized Columbian Clubs in each county to enlist workers and solicit handiwork to exhibit in the Utah and

312

Utah Historical Quarterly

43 Woman's Exponent 20 (September 1, 1891): 36; E A McDaniel, Utah at the World's Columbian Exposition (Salt Lake City, 1894), p 73

Woman's buildings.44 To discern the reality of women's everyday experience the national board solicited from each state statistical surveys of women's employment and reports on their legal status, their clubs and societies, the philanthropy and reform work in which they were engaged, and other notable achievements.45 Utah women also produced three volumes that utilized much of the data: Charities and Philanthropies, Woman's Work in Utah, edited by general Relief Society secretary Emmeline B. Wells with the help of her non-Mormon friend EmmaJ. McVicker; Songs and Flowers of the Wasatch, a selection of poems by Utah women poets dedicated to Margaret Salisbury; and World's Fair Ecclesiastical History of Utah, compiled by representatives of all the religious denominations in Utah and edited by Relief Society leader Sarah M. Kimball. The preface to the Ecclesiastical History defined their hope for more tolerance and unity:

It is the earnest desire of members of the committee that a closer feeling of unity, and a broader desire for general helpfulness may result from the study of this little volume which we dedicate with love and prayers to the World's Columbian Exposition.46

In addition, twelve Utah women submitted their books to the library of women authors in the Woman's Building, including the antiMormon novels ofJennie Froiseth and Cornelia Paddock.47

Margaret Salisbury used her personal friendship with Bertha Palmer to obtain a special congressional appropriation to Utah women to prepare a silk exhibit for the Woman's Building in addition to the cream-colored silk curtains embroidered with the sego lily that Utah women contributed to its decor. Salisbury appointed Isabella Bennett, Corinne Allen, and Mormons Zina D H Young, Emmeline B. Wells, and Margaret A. Caine to arrange the exhibit. They invited skilled Utah women to demonstrate the entire silkmaking process. Sericulture, originally a Relief Society enterprise, had waxed and waned as a viable Utah industry. Over the years many

44 Margaret Salisbury's special appeal to the legislature for funds to support Utah women's contribution to the Woman's Building was a brief synopsis of the broad range of industry and productivity in which Utah women were engaged "whether in the studio, counting house, schoolroom, factory, mill, dairy, or the farm." She noted the many employments and professions in which women were trained and urged the legislature to allow Utah women the opportunity "to meet their sisters of the different States and Territories in a manner highly creditable to the energy, intelligence and talent which characterize the women of the West." See "An Able Appeal," Woman's Exponent 20 (March 1, 1892), 125-26.

45 See Weimann, TheFair Women, p. 381; also Woman's Exponent 21 (August 1, 1892): 24

46 World's Fair Ecclesiastical History (Salt Lake City, 1893), pp vi-vii

47 The others were Eliza R Snow, Hannah T King, Augusta J Crocheron, Mary Jane Tanner, Romania B Pratt, Mrs W S McCornick, Mary E Almy, Emily B Spencer, Hannah Cornaby, and Sarah E Carmichael See Woman's Exponent 22 (April 15, May 1, 1893): 156

Decade ofDetente 313

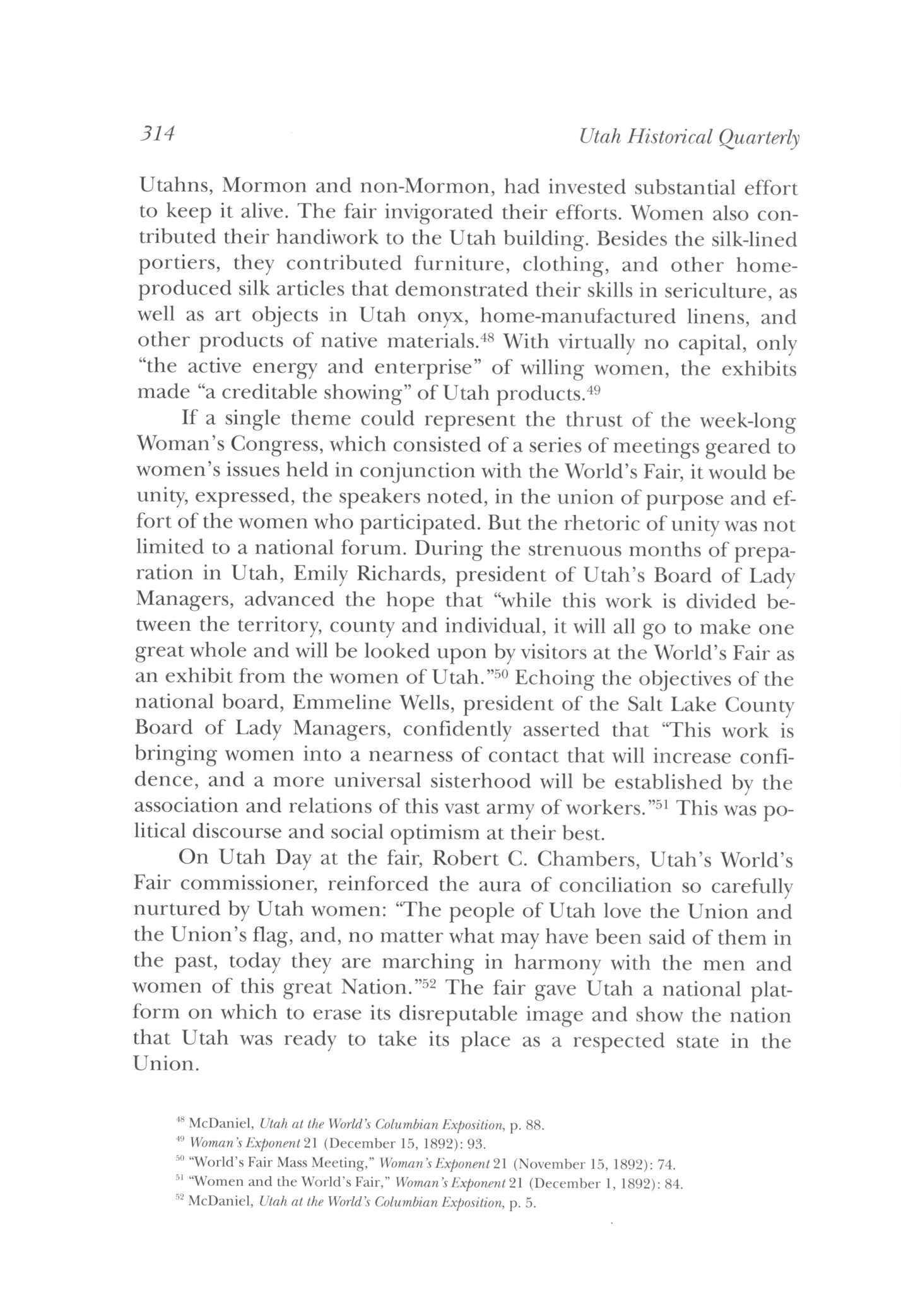

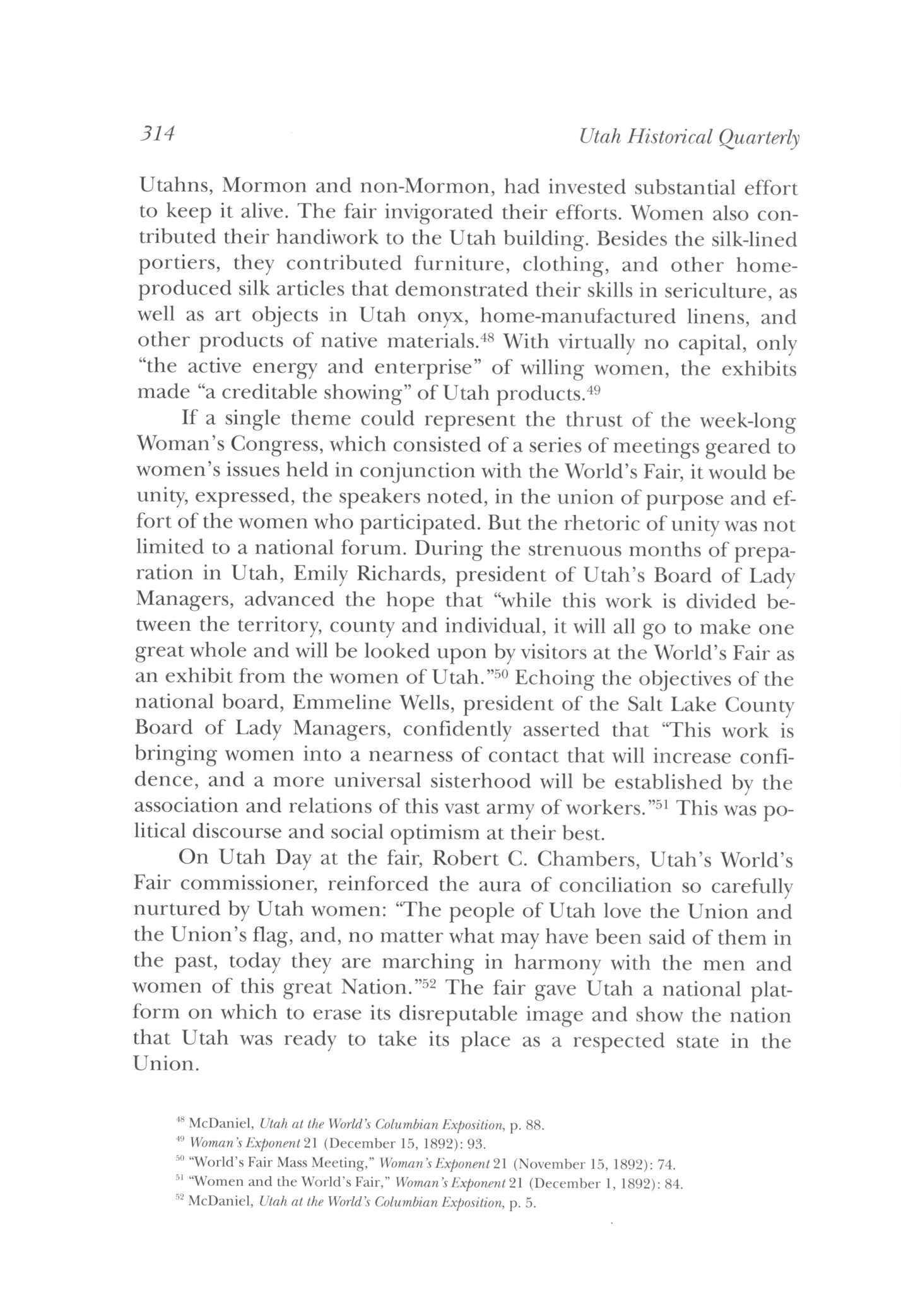

Utahns, Mormon and non-Mormon, had invested substantial effort to keep it alive. The fair invigorated their efforts. Women also contributed their handiwork to the Utah building Besides the silk-lined portiers, they contributed furniture, clothing, and other homeproduced silk articles that demonstrated their skills in sericulture, as well as art objects in Utah onyx, home-manufactured linens, and other products of native materials.48 With virtually no capital, only "the active energy and enterprise" of willing women, the exhibits made "a creditable showing" of Utah products.49

If a single theme could represent the thrust of the week-long Woman's Congress, which consisted of a series of meetings geared to women's issues held in conjunction with the World's Fair, it would be unity, expressed, the speakers noted, in the union of purpose and effort of the women who participated. But the rhetoric of unity was not limited to a national forum During the strenuous months of preparation in Utah, Emily Richards, president of Utah's Board of Lady Managers, advanced the hope that "while this work is divided between the territory, county and individual, it will all go to make one great whole and will be looked upon by visitors at the World's Fair as an exhibit from the women of Utah."50 Echoing the objectives of the national board, Emmeline Wells, president of the Salt Lake County Board of Lady Managers, confidently asserted that "This work is bringing women into a nearness of contact that will increase confidence, and a more universal sisterhood will be established by the association and relations of this vast army of workers."51 This was political discourse and social optimism at their best.

On Utah Day at the fair, Robert C Chambers, Utah's World's Fair commissioner, reinforced the aura of conciliation so carefully nurtured by Utah women: "The people of Utah love the Union and the Union's flag, and, no matter what may have been said of them in the past, today they are marching in harmony with the men and women of this great Nation."52 The fair gave Utah a national platform on which to erase its disreputable image and show the nation that Utah was ready to take its place as a respected state in the Union.

48 McDaniel, Utah at the World's Columbian Exposition, p. 88

49 Woman's Exponent 21 (December 15, 1892): 93

0 "World's Fair Mass Meeting," Woman's Exponent 21 (November 15, 1892): 74

51 "Women and the World's Fair," Woman's Exponent 2\ (December 1, 1892): 84

52 McDaniel, Utah at the World's Columbian Exposition, p. 5

314 Utah Historical Quarterly

The popularity of the silk-making demonstration at the fair and talk about a permanent woman's building prompted Utah women to work on a special silk exhibit for the building and to resuscitate the moribund silk industry in Utah With the urging of Margaret Salisbury's silk committee, the Utah legislature approved organization of a Utah Silk Commission. Zina D. H. Young was appointed president and Isabella E Bennett, Margaret A Caine, Ann C Woodbury, and Mary A. Cazier became members of the commission. A bounty of twenty-five cents for a pound of cocoons ignited a flurry of interest, but the bounty became too large a financial drain and was withdrawn in 1905.53 Despite its ultimate failure, this cooperative effort proved to be another consequence of the spirit of detente that had motivated so much community action during this socially conscious period.54

And so the decade drew to a close. The accommodation that had been achieved was remarkable considering the intensity of the prior discord. Personal friendships, cooperative civic projects, and organizational alliances emerged, healing differences and bridging the gulf of intolerance and conflict. Emmeline B. Wells, a noted LDS social activist and women's leader, wasjust one of many who found that her association with non-Mormons such as Margaret Salisbury, Emma McVicker, and Lillie Pardee became enduring friendships. Like other club women she brought the clubs she had founded, the Reapers and Utah Woman's Press Club, into cooperative participation in the Utah Federation of Woman's Clubs and the civic programs it supported. Capitalizing on the strength of unified action, the women of Utah were able to promote legislation and initiate programs and projects that would improve Utah's moral, educational, and social environment.

But the fragility of this carefully nurtured alliance was exposed even before the decade ended. The election of LDS church leader and polygamist B. H. Roberts to Congress in 1898 provoked another national woman's antipolygamy campaign It began with a protest from several Protestant groups in Utah, denouncing not only his marital status but the potential conflict of interest his dual offices posed It swelled into a national crusade embracing the press, religious

53 The history of sericulture in Utah can be found in Chris Rigby Arrington, "The Finest of Fabrics: Mormon Women and the Silk Industry in Early Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly 46 (1978): 376-96.

'

Decade ofDetente 315

4 Support for the silver standard also brought Mormon and gentile women together in a mass meeting, former polygamy adversaries sitting together speaking on the same platform, and signing their names on the same memorial to Congress See Woman's Exponent 22 (August 1, 1893): 12

organizations, and a host of national women's associations. Many of them, such as the powerful Woman's Christian Temperance Union, the National Christian League for the Preservation of Moral Purity, the National Association of Loyal Women ofAmerica, and the Free Baptist Women's Missionary Society, were members of the National Council of Women scheduled to hold its triennial convention in Washington in February 1899 in the midst of the campaign against Roberts.55 The LDS Relief Society, the Young Women's Mutual Improvement Association, and the Primary Association were also members. Pressured to add another resolution against him to the growing number by other women's organizations, the National Council faced the dilemma of acceding to the demands of some of its most influential members, thereby offending its long-time LDS affiliates, or protecting the interests of its loyal LDS members and possibly alienating the membership of its most noted ones. 56 The issue divided the delegates.

Supporting a resolution against Roberts, council president May Wright Sewall urged the Mormon delegates not to miss this "golden opportunity" to gain wider acceptance and prestige among the major women's organizations by voting with them on the Roberts issue. The dilemma was not easily resolved by the ten LDS participants, since Roberts's opposition to woman suffrage just four years earlier had alienated him from many of the women of Utah. Mormon loyalties prevailed over gender ties, however, and the Utah delegates, along with sympathetic members of the council, all spoke in defense of Roberts's constitutional right to be seated. Their arguments succeeded in convincing a majority of council members to pass the milder of the two resolutions proposed by the resolutions committee, which denounced all "lawbreakers" in public office rather than singling out Roberts or polygamy.57

The controversial issue continued to simmer when Mormonism's growth through an active proselytizing system alarmed antipolygamists who feared a revival of plural marriage. In 1902, even as LDS delegates sat in session at another triennial convention of the

55 For details of the woman's campaign against Roberts see William Griffin White, Jr., "The Feminist Campaign for the Exclusion of B H Roberts from the Fifty-sixth Congress, "Journal of the West 17 (1978): 45-52 See also Davis Bitton, "B H Roberts and the Election of 1898-1900," Utah Historical Quarterly 2b (1957): 27-46

56 The neutral quality of its credo was clearly in jeopardy A stated aim of the council was to "strive to overthrow all forms of ignorance and prejudice by the application of the Golden Rule to society, custom and law."

"' Wells Diary, February 26, 1899; Susa Young Gates, "The Recent Triennial Convention in Washington," Young Woman'sJournal 10 (May 1899): 204-5; New YorkJournal, February 18, 1899

316 Utah Historical Quarterly

National Council of Women, then numbering over a million members, representatives of the International Council of Women, the General Federation of Woman's Clubs, and "other kindred associations" spoke before the House Committee on the Judiciary in support of a constitutional amendment against polygamy. As a result of their appeal, Congress proposed a committee of investigation to study the "facts of missionary work in Utah."58

Though nothing came of the 1902 investigation, the issue exploded again a year later with the election of Apostle Reed Smoot to the Senate. Though he was a monogamist, opponents once again feared that his church position would compromise his political office. As with Roberts, a groundswell of opposition once again began in Utah, gaining in national support until a hearing was launched by the Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections. Not until February 1907, four years after his election, was he finally permitted to assume his place in the Senate.59

During the hearings women's groups were active against Smoot. In February 1904, at the Executive Meeting of the National Council of Women held in Indianapolis, an antipolygamy resolution was presented by the chair of the committee on resolutions, Elizabeth Grannis, who was also president of the National Christian League for the Promotion of Social Purity The resolution echoed the objective of the earlier purity crusade and had originated, according to Grannis, in Salt Lake City "by people who knew of the continued presence of polygamy." Mormon delegates Emmeline B Wells and Maria Y Dougall succeeded in getting it tabled.60

However, three months later the president of the National Congress of Mothers, who was also chair of the Legislative Committee of the National Federation of Woman's Clubs, proposed a resolution against polygamy and another antipolygamy constitutional amendment. Despite the "heroic" protests of Brigham Young University educator Alice Reynolds, a delegate to the convention of the National Federation, the resolution passed, and lobbying continued for an

58 Journal History of the Church, February 25, 1902, p 2

59 B H Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church, 6 vols, (reprint ed., Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1965), 6:393-99

' "Executive Session N.C.W., Indianapolis, Indiana," Woman's Exponent 32 (February 1904): 68-9 The resolution stated: "Resolved That any practice which undermines the foundation of famiiy life should be strongly deprecated, and since polygamous marriage is a terrible evil, which threatens to destroy the home and the state in portions of our country, the people should petition and protest against the seating in our national Congress any man who may practice or subscribe to it."

Decade of Detente 317

amendment.61 For a period thereafter, the Congress of Mothers, an organization that had originally welcomed Mormon women, barred them from membership.

These inflammatory anti-Mormon outbursts seriously damaged the conciliatory achievements of the earlier decade, both locally and nationally, culminating in a local incident in 1909. Following the quinquennial meeting of the International Council of Women in Toronto, Canada, a group of international delegates visited Salt Lake City. By this time many non-Mormon women had organized Utah chapters of the Maccabees, the Woman's Relief Corps, the Jewish Council, the Woman's Suffrage Council, and the National Christian League. They had followed the LDS women's organizations as affiliates of the National and International Councils of Women Representatives of these associations formed a committee to entertain the delegates with a dinner and program to be held in the pavilion at Saltair, a popular lakeside resort They appointed Emmeline B Wells, general secretary of the LDS Relief Society and a charter member of the National Council of Women, as chair and toastmistress.62 Old resentments were aroused when Wells invited LDS PresidentJoseph F. Smith, a polygamist, and his counselors to attend the festivities. The day before the reception, in an act of protest, Corinne Allen, an influential gentile committee member, sent Wells a letter of resignation, affirming her personal regard and respect and her willingness "to ignore all differences of opinion" but explaining that as a member of the National Christian League it was impossible for her to "honor a man who stands for the violation of the law which the National league is organized to uphold." In a public statement she declared that her resignation was a means of "publishing to those women who come here that the Christian women of Salt Lake City do not condone nor approve of the social ulcer which exists here."When her personal feelings for Wells and her public disapproval of polygamy conflicted, she opted for her longest held commitment. She and most of the other gentile members of the committee boycotted the reception.63 The breach was serious and left doubts about the advisability of maintaining LDS affiliation with state and national groups that continued to harbor anti-Mormon

61 Journal History of the Church, May 26, 1904, p 4

b2 "International Council Delegates," Woman's Exponent 38 (August 1909): 12; Deseret News, July 16, 1909, p 2

"'Wells Diary, July 16, 1909; Salt Lake Tribune, July 17, 1909

318 Utah Historical Quarterly

sentiments. Joseph F. Smith entered the debate in 1913, cautioning LDS women against subordinating the autonomy and objectives of their organizations to those of their national affiliations but leaving the question of continued membership to the auxiliaries.64 Though they chose to retain their association with the National and International Councils of Women, there was sufficient distancing to bring NCW president May Wright Sewall to Salt Lake City to ease the strained relations. While she was successful in strengthening ties between the National Council and its Mormon affiliates, it took a national emergency to bring local Utah women into the same measure of harmony they had experienced two decades earlier World War I was the catalyst that united their efforts in behalf of Utah once again.

Against the emotionality provoked by two decades of conflict over polygamy, the Woodruff Manifesto of 1890 had mitigated the differences between Mormon and gentile women. The social climate in Utah had become conducive for the formation of a cohesive corps of female civic workers. Through their volunteer organizations Utah women cooperated in making a social impact in Utah and had finally connected with public-spirited women throughout the country as "Utah women."

But the rhetoric of female community that had been so enthusiastically dispensed throughout the decade and the public action it had fed hid the realities of entrenched differences. It took decades for the specter of polygamy to be laid to rest, even after a second Manifesto in 1904. Polygamy had proven to be as divisive among women in Utah as race or class among women elsewhere. Female community, it seems, was always subject to the claims of a more compelling female loyalty than gender.

While the harmonious relationships during this period were delicately balanced on volatile issues, the decade gave women precedents on which to base future cooperative action. They had proven how effective coalitions of disparate groups can be when propelled by shared objectives, and they had generated the cohesiveness that female networks can create in a community Though the period is most remembered for the political, legal, and social changes that transformed Utah, less noted but equally notable were the women who defined and negotiated their own social politics during this dynamic decade in Utah's history.

Decade ofDetente 319

64 Relief Society Minutes, October 3, 1913; see also March 17, 1914, LDS Church Library Archives

So Bright the Dream: Economic Prosperity and the Utah Constitutional Convention

BY JEAN BICKMORE WHITE

BY JEAN BICKMORE WHITE

industry

Utah

part of the statehood "dream"for many.

Main Street

Second South in

Salt Lake City

limited

time of statehood. USHS collections.

Attracting business and

to

was

The intersection of

and

downtown

shows

development near the

Dr White is emeritus professor of political science, Weber State University

WHE N UTAH'S CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION MET ON MARCH 4, 1895, to write the document that would usher in Utah statehood, the delegates were not entirely happy to be meeting in the Salt Lake City and County Building Although the imposing structure was practically brand new, delegates voiced a litany of complaints about it. The location was too far from the downtown business district. The meeting place, a courtroom on an upper floor, was hard for the older delegates to reach, since there was no elevator. After meeting for a few days in the room they had many more complaints—about the lack of desks, the poor ventilation, the limited space for visitors.

To add insult to perceived injuries, the windows over the doorways read "Criminal Court Room." This led to no end ofjokes about the character of the delegates. The committee on arrangements reported that they could find no other suitable meeting place, and the price certainly was right: Salt Lake County offered the room free of charge. Since Congress had appropriated only $30,000 to spend on all the expenses of the convention, the delegates decided to make the best of it

Within a few days the room was festively decorated by Salt Lake County. The Deseret Evening News reported on March 14 that the alcove above the president's chair had been "artistically arrayed in the national colors, and reaching out from it in all directions were more flags than any delegate cared to count." Immense streamers of bunting ran from the chandeliers in the center of the room to the corners. Large steel engravings of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and the current president—Grover Cleveland—adorned the walls.

The 107 men elected to write a constitution for Utah faced the job with both hopes and fears. Although they were diverse in background, interests, political philosophy, and financial means, they were united in these hopes and fears Even though they had an Enabling Act passed by Congress the year before to guide them, they still had a lingering fear that somehow the new constitution could be rejected, either by Utah voters at an election in the fall, or by President Grover Cleveland.1 Neither fear was welljustified, for there had

1 An Enabling Act is not necessary for statehood and does not guarantee it It does list conditions that should be met by a territory, and in Utah s case—after the rejection of previous constitutions—it set forth requirements to be met in its 1895 document Utah's act is in Ch 1328, Statutes at Large, 107. It is also printed in the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: Star Printing Co., 1898), 1:3-8 (hereinafter Proceedings).

Utah Constitutional Convention 321

been sweeping changes in the territory during the previous five years. The 1890 Manifesto of the Mormon church urging its members to obey the anti-polygamy laws had paved the way for dramatic political and economic changes in Utah and had helped to foster a new and improved national image for the territory. It had also made possible a new atmosphere in which Mormons and many prominent nonMormons could work together to break down religious, political, and economic barriers that had long divided them.2 By 1895 both Mormon and gentile leaders had concluded that continuing as a territory was untenable Future population growth and development of the area's vast natural resources were unlikely without statehood

Achieving statehood was the primary goal of the convention

The fear that they might somehow lose this prize, now that it was almost within their grasp, motivated delegates to be cautious and conservative. They shunned experimentation and generously copied older constitutions, reasoning that these documents had survived presidential scrutiny and had "safe" provisions.3 To guard against rejection by the voters at an election in the fall, they tried to keep taxes and debt low. This was considered wise by local newspaper editors who claimed to feel the public pulse.

The Salt Lake Tribune, in a March 7 editorial, bluntly told the delegates that "The people cannot stand much added burdens in any form, and the more that are provided in the Constitution the greater the danger of its rejection." In a list of "do's" and "don'ts," the Tribune urged (among many other things): Do let taxation be as little felt as possible.

Don't provide for extravagance.

Don't attempt to reform the world.

Don't put in fads and frivolous provisions.

In short, provide the framework necessary for a State government, and when you have done that, squelch all else and quit.

The Salt Uake Herald noted in a March 21 editorial some fears

2 Members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are called Mormons or Saints Utahns who are not members, including Jews, are commonly known as gentiles The economic, political, and social polarization of the territory on religious lines and the gradual accommodations achieved by the two groups are discussed in Jean Bickmore White, "Prelude to Statehood: Coming Together in the 1890s," Utah Historical Quarterly 61 (1994): 300-315

3 The constitution written in 1895 cannot trace its ancestry to a single document Delegates were given copies of all forty-four state constitutions, and they frequently referred to them. They paid close attention to constitutions of the six western states that had been admitted in 1889 and 1890: Washington, Montana, North and South Dakota, Idaho, and Wyoming, but also to New York state's new constitution, which had been rewritten in 1894 The Washington State Constitution of 1889 was frequently quoted and copied

322 Utah Historical Quarterly

that statehood would not be approved because of the shift of many expenses from the federal to the new state government. Delegates should not put anything in the document that would feed these fears, they cautioned.

This fear of rejection was not the only emotion that drove convention action. From the start there was an exuberant feeling that the future of Utah as a state would be far different from its turbulent territorial history—if only it could attract business and industrial development to augment its agricultural economy. Delegates dreamed that statehood—which now seemed so close—would bring an influx of new capital to spur mineral and other industrial growth and open a bright new era of economic prosperity. The need for outside capital was clear One writer on the West has pointed out that development of the economy of the region matured only as it absorbed "massive inputs of Eastern capital and technology."4 Frank J. Cannon, Utah's delegate to Congress, expressed a common sentiment when asked whether he thought statehood would benefit Utah to any great extent:

I believe that when Utah becomes a full-fledged state a great impetus will be given to our industries. I think, however, that it will be a healthy, normal advance, and result in great industrial good to our state. We have, to begin with, a population of 300,000, and we are able to take care of over a million people I should say that a million or more people can easily support themselves in Utah.5

The future also looked bright to the Salt Lake Tribune. On March 8, as the convention was getting down to business, crowds of spectators gathered at the southeast corner of Temple Square to see a gas torch lighted, completing the transmission of natural gas into the city. The event prompted an exuberant editorial the next day in the Tribune.

With this new fuel available, Salt Lake City should take a bound forward in home industries Manufacturers are no longer in the grasp of the coal monopoly; the smoke nuisance will be abated; there will be opportunity for development on the grandest scale.

4 Gene M Gressley West by East: The American West in the Gilded Age, Charles Redd Monographs in Western History, No 1 (Provo, Ut.: Brigham Young University Press, 1972), p 2

:' Salt Lake Herald, April 16, 1895 Like many others, Cannon tended to let enthusiasm run ahead of the facts Utah's population was recorded at just 210,779 in the 1890 census and did not reach 300,000 until after the turn of the century The 1970 U.S Census was the first to record more than a million residents. Allan Kent Powell, ed., Utah History Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), p 431

Constitutional Convention 323

Utah

. . . Salt Lake can be a second Pittsburgh, minus the smoke and grime. No other city in the land possesses the prospects for great growth that are open to Salt Lake City

Given the depressed state of Utah's economy in 1895, it took a giant leap of imagination to see Salt Lake City as a pristine-air Pittsburgh. Utah's economy was still primarily agricultural. It was augmented by a struggling mineral industry, but the need for outside capital limited the full exploitation of the area's metal mines. The territory was sadly short of the manufacturing firms that could absorb her increasing workforce and bring in much-needed dollars from outside her borders.

The Panic of 1893 and the recession of the 1890s were as keenly felt in Utah as in the rest of the nation.6 Local agriculture in Utah was in the process of transition from small farms—the backbone of Brigham Young's plan for a self-sufficient Mormon economy—into commercial farming.7 Mining, which would transform some proudly independent prospectors into a cadre of millionaires, needed outside capital in the 1890s. Surface ores had been exhausted and, as Dean L. May observed, "Further development depended upon deeper, lower-grade ores, which could be mined only with considerably greater investment."8 Manufacturing of finished products for export outside the territory was slow to develop; most manufacturing in Utah involved the conversion of local farm and mineral products for use by Utahns or intermediate processing of these products for export.9 A combination of circumstances was changing the economic climate in Utah. The two separate economies analyzed by LeonardJ. Arrington—Mormon and gentile—that had existed throughout most of the history of the territory were moving closer together.10

h The impact of the 1890s depression on agriculture and the effect of the gold standard on silver are discussed in Harold Underwood Faulkner, American Economic History, 8th ed.(New York: Harper & Row, 1960), pp 519-23 For the effect of the depression in Utah see LeonardJ Arrington, "Utah and the Depression of the 1890s," Utah Historical Quarterly 29 (1961): 3-18.

' Charles S Peterson points out that during the 1890s "Farming became a business rather than a way of building the Kingdom Technology became increasingly important and manpower less so." See "The Americanization of Utah's Agriculture," Utah Historical Quarterly 41 (1974): 122-23 There were increasing indications, Peterson concludes, that "an almost desperate quest for commercial success characterized the lives of progressive farmers."

8 "Towards a Dependent Commonwealth," in Richard D Poll, ed., Utah's History (Provo, Ut.: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), p. 223.

9 Ibid., p 235

10 Arrington described the divided economy as a "two-decker economy" until the turn of the century, one based on farming and manufactures for home use, the other on mining and trading From Wilderness to Empire, University of Utah Institute of American Studies, Monograph No 1, 1961, p 14

324 Utah Historical Quarterly

The desire of Utahns to parlay their natural resources into prosperity created a need for expanding export industries The territory was becoming interdependent with the national economy and needed financial assistance for further development. Some industrial development was stimulated by the Mormon church, notably in the sugar industry, hydroelectric power systems, and salt production from Great Salt Lake.11 The church, however, had financial problems of its own; eventually its leaders found it unadvisable to use church credit to shore up the Utah economy. 12

Considering the high unemployment and fragile economy of the territory in the early 1890s, it is not surprising that concern with economic matters should occupy so much attention during the Constitutional Convention of 1895. It is surprising that there was so much optimism about the economic prosperity delegates thought would arrive after the attainment of statehood Running through the debates was a feeling that if the right climate could be fostered under the constitution, both home industries and new, scarcely dreamed-of enterprises funded by outside capital, would thrive in the new state.

The delegates represented a broad spectrum of the territory's population, and it seemed that all of them dreamed of prosperity for Utah Since 1894 had been a strong Republican year, the fifty-nine delegates from that party outnumbered the forty-eight Democrats, but generally issues were not decided along party lines. Delegates ranged in age from a twenty-five-year-old teacher to a seventy-sixyear-old builder; those in their forties made up the largest age group Voters in 1894 had elected men who were prominent in their communities and veterans of government service as mayors, city council members, county selectmen, county attorneys, probate judges,justices of the peace, and other local offices. Several delegates had served in previous constitutional conventions and others in the territorial legislature Farmers and stock-raisers made up the largest occupational group, followed by merchants and manufacturers, then

11 See Arrington, "Utah and the Depression of the 1890s," pp 12-18, for a discussion of measures taken by Mormon leaders to solve employment problems and promote industry in the face of the 1890s depression

12 See Ronald W Walker, "The Panic of 1893" in Powell, Utah History Encyclopedia, p. 413 Although church-financed enterprises, including the building of Saltair resort, helped to provide jobs, they were contrary to the desires of many gentiles to minimize the role of the Mormon church in Utah's economy and foster an open field for private enterprise See Arrington, "Utah and the Depression of the 1890s," p 18

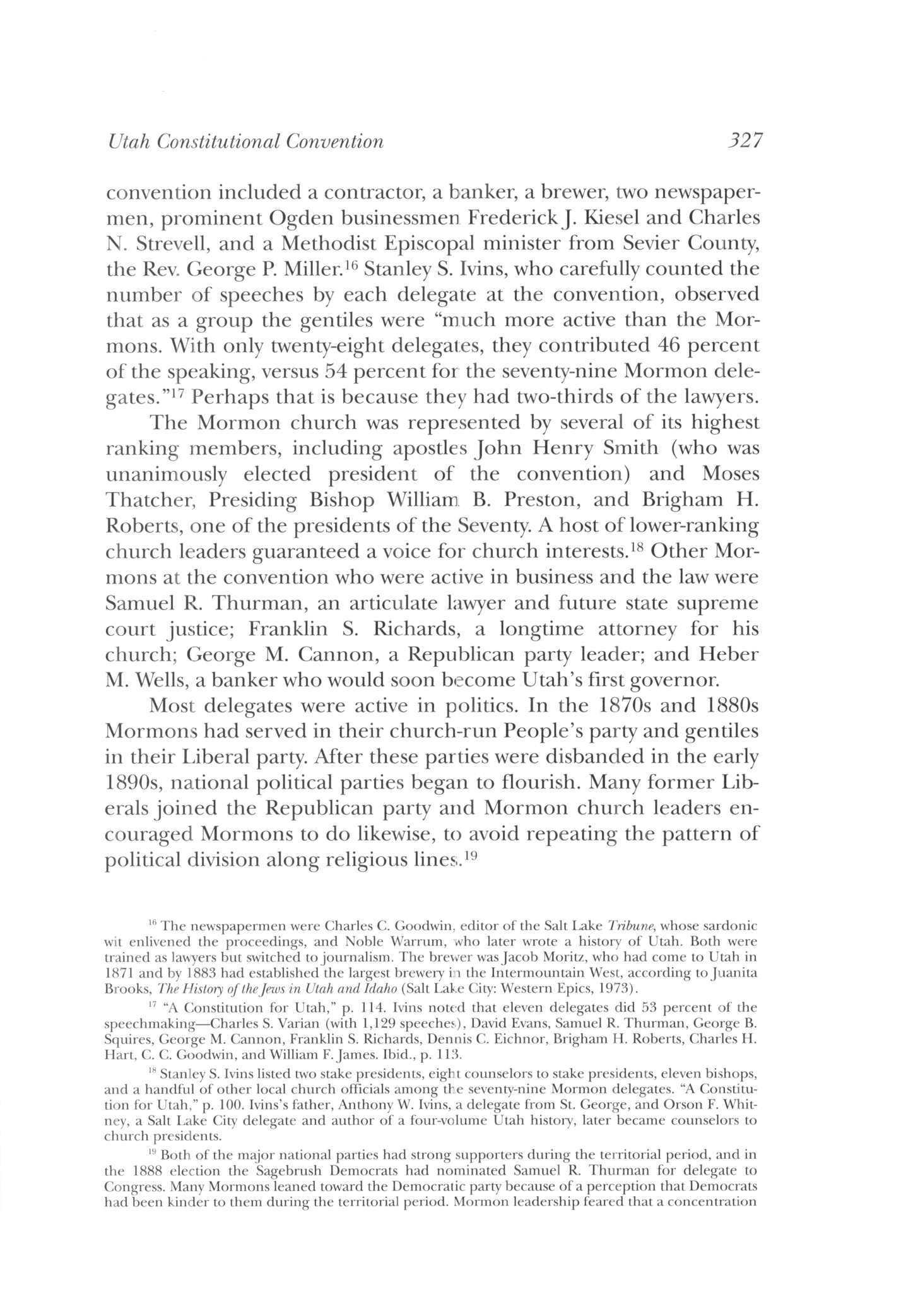

Utah Constitutional Convention 325

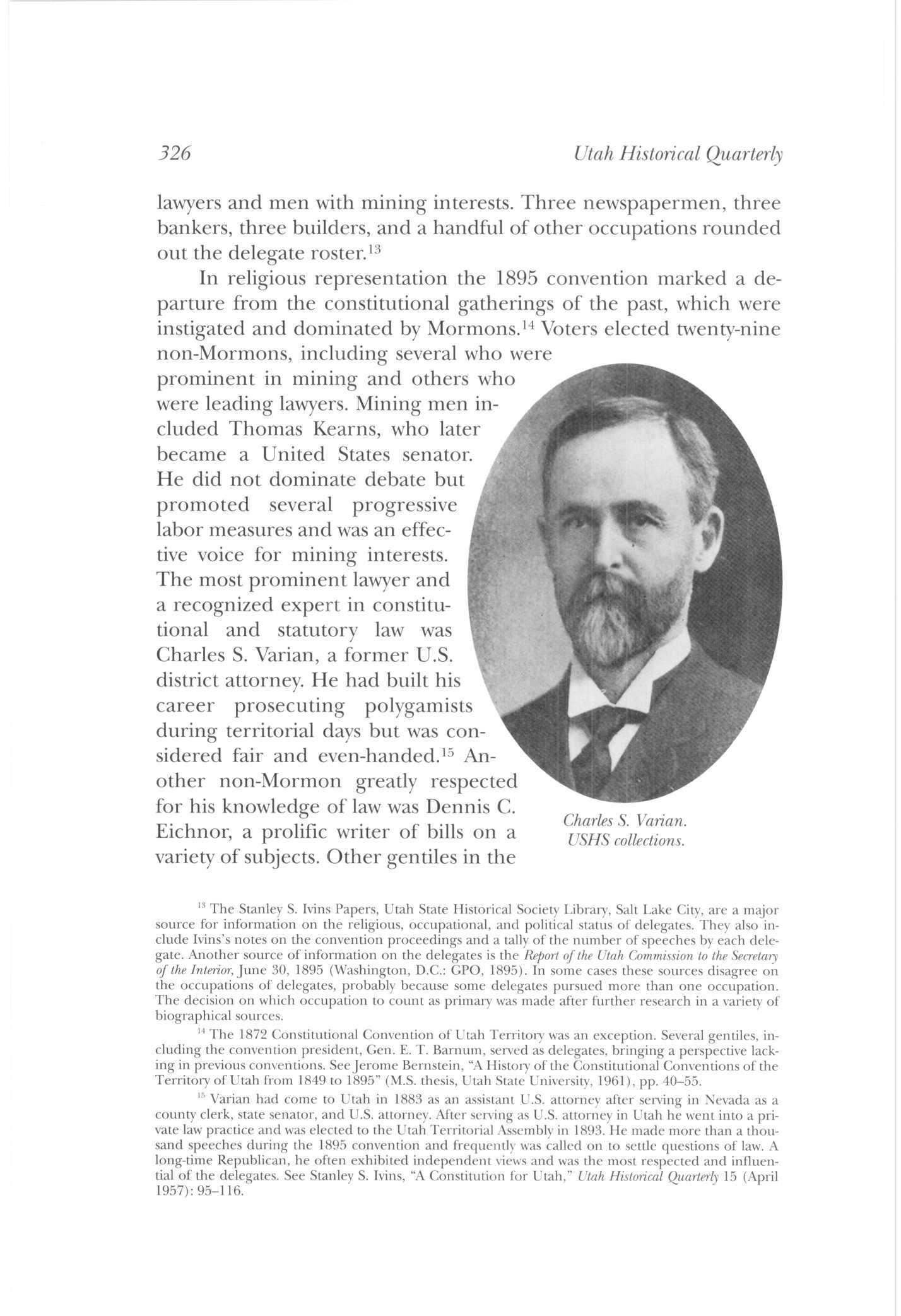

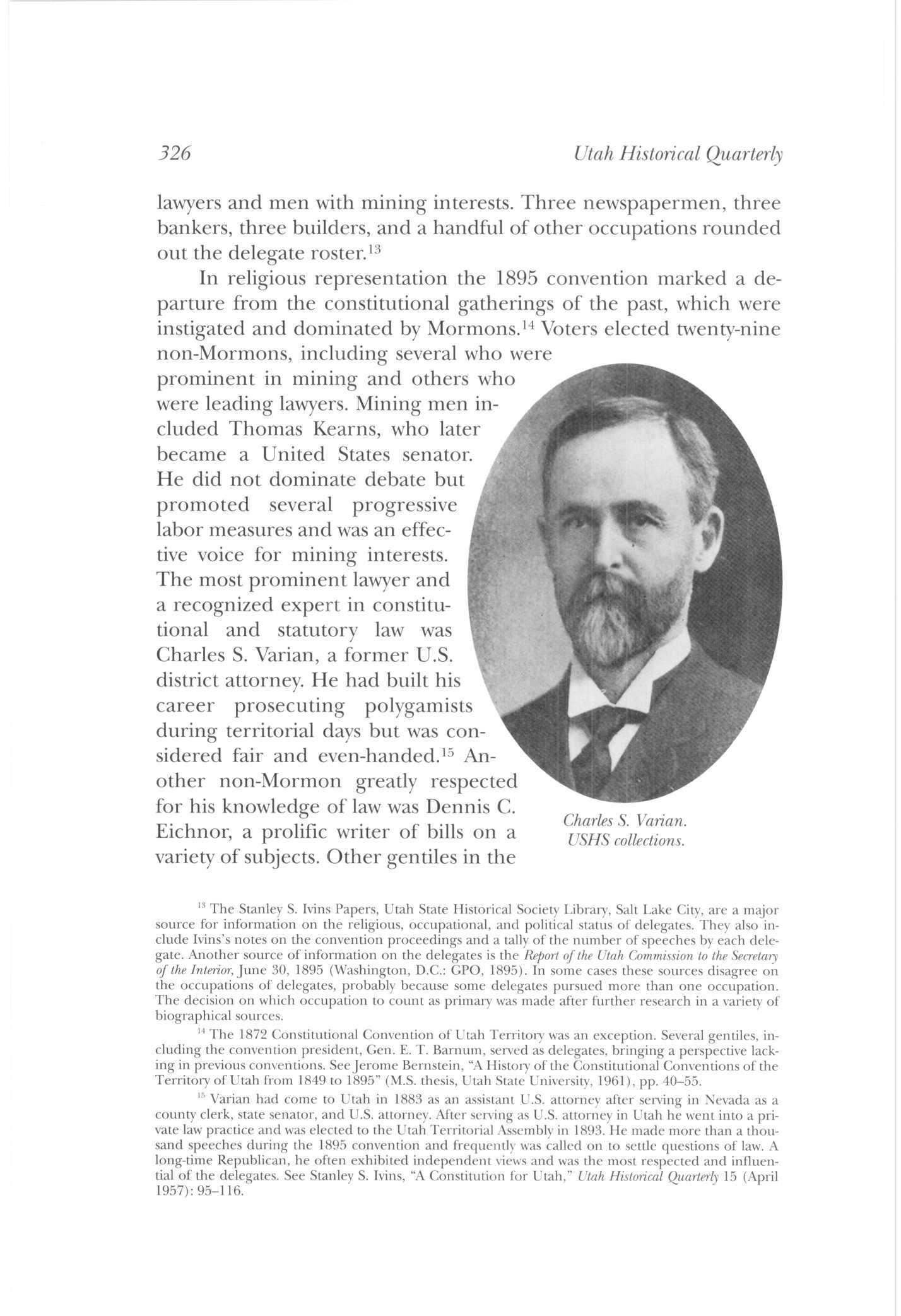

lawyers and men with mining interests Three newspapermen, three bankers, three builders, and a handful of other occupations rounded out the delegate roster.13