Ul hd W o I—» co CD \ o d d S 53 H

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, Managing Editor

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, Salt Lake City, 1997

JANICE P. DAWSON, Layton, 1996

AUDREY M GODFREY, Logan, 1997

JOEL C. JANETSKI, Provo, 1997

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora, WY, 1996

GENE A SESSIONS, Ogden, 1998

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 1996

RICHARD S. VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over), $15.00; contributing, $25.00; sustaining, $35.00; patron, $50.00; business, $100.00.

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 5!4 or 3M> inch MS-DOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Second class postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah

Postmaster: Send form 3579 (change of address) to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101

HISTORICA L QUARTERLY Contents SPRING 1996 \ VOLUME 64 \ NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 107 SALT LAKE CITYS REAPERS' CLUB . . SHARON SNOW CARVER 108 THREE DAYS IN MAY: LIFE AND MANNERS IN SALT LAKE CITY, 1895 DEAN L. MAY 121 LEWIS LEO MUNSON, AN ENTREPRENEUR IN ESCALANTE, UTAH, 1896-1963 VOYLE L. MUNSON 133 SOME MEANINGS OF UTAH HISTORY THOMAS G. ALEXANDER 155 THE HISTORICAL OCCURRENCE AND DEMISE OF BISON IN NORTHERN UTAH KAREN D. LUPO 168 GORGOZA AND GOGORZA: FICTION AND FACT CHARLES L. KELLER 181 BOOKREVTEWS 187 BOOKNOTICES 197 THE COVER Women with bicycles, May 28, 1924, may have been Utah Power & Light Co. employees, according to photographer's note. Shiplerphotograph in USHS collections. © Copyright 1996 Utah State Historical Society

BRADLEY W. RICHARDS TheSavage View: Charles Savage,PioneerMormon Photographer . . WILLIAM C SEIFRIT 187

C MARK HAMILTON Nineteenth-century Mormon Architecture and City Planning

PETER L. GOSS 188

JACK GOODMAN AS YOU PassBy:Architectural Musings onSaltTake City,a Collection ofColumns and Sketchesfrom the Salt Lake Tribune JULIE OSBORNE 189

MAUREEN URSENBACH BEECHER, ed. ThePersonalWritings ofElizaRoxcy Snow POLLY STEWART 190

REBECCA BARTHOLOMEW. Audacious Women: EarlyBritish Mormon Immigrants

LYNNE WATKINS JORGENSEN 192

WILLIAM JOHN GILBERT GOULD My Tife onMountain Railroads

ROBERT S. MIKKELSEN 193

COYF. CROSS II. GoWestYoung Man! HoraceGreeley's Visionfor America

SCOTT C ZEMAN 194

FRANCIS HAINES. TheBuffalo: TheStory of American Bison and Their Hunters from Prehistoric Timesto the Present

KAREN D LUPO 196

Books reviewed

In this issue

As the decade of the 1890s dawned and Utahns busied themselves with their final push for statehood, an important social trend was sweeping across the nation—the creation of women's organizations. Utah responded in mainstream fashion, organizing numerous clubs and associations to serve wideranging needs. One such group, Salt Lake City's Reapers' Club, is described in our first article and analyzed not only for format but also for its contribution to the larger movement.

The next three articles also reflect a centennial connection At the time Salt Lake City hosted the state constitutional convention in May 1895, it was in the process of shedding a frontier image and striving for a cosmopolitan one. A three-day summation of newsworthy events of that time and place offers a lively and revealing approach to community history Then comes a look at Leo Munson, born in the year of statehood and possessed from an early age with a natural aptitude for business. His story is much more than a biography. It is a history of the values, axioms, and entrepreneurial spirit that have defined business success through the ages. Thousands of Leo Munsons have created an interesting economic pattern and cultural diversity in Utah that are given meaning in the wonderful thought-piece, penned by one of our state's premier historians, that follows.

The issue concludes with two articles that probe myth and mystery in the prehistorical and historical record. Whether tracking bison or place names, scholars of our craft continue to delight and amaze with their endless curiosity, critical thinking, breadth of interest, and love of research

'.,'':

Second South, looking westfrom Main Street, ca. 1896. USHS collections.

Salt Lake City's Reapers' Club

BY SHARON SNOW CARVER

O N MONDAY, OCTOBER 3, 1892, EMMELINE B. WELLS, prominent Salt Lake City editor, writer, and Mormon women's leader, recorded in her diary that she had "sent for some of the sisters to come and talk over the matter of a literary club. . . ."1 Eight prominent Salt Lake City women, all Mormons, answered her summons and decided to call an organizing meeting in two weeks.2

This study focuses on the membership of the Reapers' Club, the Salt Lake City literary club established by Wells, and demonstrates how the organization fits into the state and national literary club movement Recent studies by Karen Blair and Anne Firor Scott give a composite picture of American women's literary clubs at the turn of the century.3 Although they use an impressive array of personal collections and club records from the East and West coasts, touching down quickly in Ohio, Texas, and California, their view does not take into consideration the uniqueness of the West and raises the question of how the western woman fits into the literary club picture. Additionally, the study of Utah women's club movements has been very general or limited to the Mormon church's Relief Society or the specific women involved. For this demographic study of a specific Salt Lake women's club, the membership was identified for three years—1892, 1900, and 1907—and collective biography was used. It was possible to identify and categorize fifty of the fifty-seven women members (88 percent) for these three years The categories were determined by and compared to Blair's general description of women's clubs to ascertain if the Reapers' Club conformed to the national movement.

During the 1890s women in America participated in a frenzy of organizing despite early cries that such activities would result in

Ms Carver is a doctoral candidate in U.S history at Brigham Young University

1 Emmeline B Wells,Journals, vol 15 (Monday, October 3, 1892): 90, typescript, Archives, Harold B Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah

2 These women were identified by Wells as "Drs. Shipp Ellis & Maggie [medical doctors Ellis Reynolds Shipp and her sister wife Maggie C Shipp later Maggie Roberts] Mary & Lillie Freeze [sister wives Mary Ann Burnham Freeze and Lelia Tuckett Freeze] Ruth [May] Fox, Sister Phebe [Clark] Young, Margaret [Ann Mitchell] Caine and Sister [May Booth] Talmage "

3 Karen Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist: True Womanhood Redefined, 1868-1914 (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, 1980); Anne Firor Scott, Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1991).

ruined homes and neglected children.4 According to William O'Neill's history of feminism, by 1900 "half of the important American women's organizations had been established, most of them in the 1890's."5 This organizational activity can be attributed to a number of changes—including access to education and the increasing "respectability" of the suffrage movement—in the status of women that occurred in the decades immediately preceding it.6 However, the increased leisure (helped by the declining birthrate) of middle-class wives and mothers, according to Carl N. Degler, was the prevailing circumstance that contributed to the club phenomenon. 7

Urbanization and industrialization brought change to the middle-class home and reduced household chores. In addition, the concept of separate spheres for men and women, in which the leisure of the wife was a symbol of success, created a large group of middle-class women searching for an acceptable opportunity in society for companionship and excess energies.

When they were formed, a majority of the new middle-class organizations were originally designed for self-improvement Studies of these literary clubs suggest that they played a vital role in the movement of women from the private sphere of the home into the more public sphere of civic and political reform Clubs helped and encouraged women to broaden their influence and autonomy by capitalizing on their so-called inherent domestic and moral superiority. In The Clubwoman asFeminist Karen Blair investigates the role of these clubs in

4 Scott, Natural Allies, p 117

5 William O'Neill, Every One Was Brave: A History of Feminism in America (Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969), p 149

6 For the tripling of female college enrollment between 1890 and 1910 see Steven Mintz and Susan Kellogg, Domestic Revolutions: A Social History ofAmerican Family Life (New York: The Free Press, 1988), p 111

7 Carl N Degler, At Odds: Women and the Family in Americafrom Revolution to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980), p 324

SaltTake City'sReapers' Club 109

Emmeline B. Wells. USHS collections.

nineteenth-century feminism and concludes that they offered women a viable feminist alternative to the more radical suffragists. She further credits them with laying the foundation for the surge of support that the suffrage movement experienced around 1910.8 In Natural Allies Anne Firor Scott argues that the "culture club" was central to "American social and political development."9 The involvement of an enormous number of respectable "ladies" in the literary club movement indicates that rather than being an anomaly, clubs were a viable part of the Progressive Era.

During the middle and late nineteenth-century, Utah was an area of vigorous feminist activity. While most powerful American men resisted woman suffrage, many of Utah's Mormon leaders openly supported strong women who would sustain church doctrine while taking part in feminist activities.10 Because church leaders encouraged participation in the national suffrage movement, the role of Utah women's literary clubs in the extensive state suffrage activity could prove vital to understanding the feminist movement in the West

Unique in the Intermountain West, Utah was settled by Mormon pioneers, a cohesive group with clearly defined leaders. Polygamy, the unorthodox marriage pattern participated in by a large group of Mormons, caused numerous problems between the faithful and later arriving non-Mormon settlers. Separate but often parallel women's reform and social clubs were organized with religion (including polygamy) being the major focus of division.11

In 1890, after intense federal prosecution of polygamists, Mormons officially discontinued the practice of plural marriage in the United States. While abandoning polygamy did not immediately reconcile the Mormons and their neighbors, it did lead to a period of cooperation.12 In her 1898 History oftheWoman'sClubMovement, Jennie

8 Suffragists demanded, as Ellen DuBois explains in "The Radicalism of the Woman Suffrage Movement: Notes Toward the Reconstruction of Nineteenth Century Feminism," in Mary Beth Norton, ed., Major Problems in American Women's History (Lexington, Mass.: D C Heath and Co., 1979), pp 209-14, admission to the social order on an individual basis not connected with woman's place in the home This radical stand, bypassing the woman's sphere, is what many women found difficult to support Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, p 3

9 Scott, Natural Allies, p. 2. Feminist and suffragist are used interchangeably in this paper. They refer to the later movement that expanded woman's sphere to include reform in the public sector

10 Anne Firor Scott, "Mormon Women, Other Women: Paradoxes and Challenges," fournal of Mormon History 13 (1987): 14 Published speeches of church leaders in the DeseretNews and the Woman's Exponent also show this support.

11 See Carol Cornwall Madsen, "Decade of Detente: The Mormon-Gentile Female Relationship in Nineteenth-century Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly 63 (1995): pp 298-319; and Barbara Hayward, "Utah's Anti-Polygamy Society, 1878-1884" (master's thesis, Brigham Young University, 1980) Until 1891 Utah's political parties were organized on religious lines. Clubs and organizations were divided in the same way.

12 Madsen, "Decade of Detente."

HO UtahHistorical Quarterly

Croly, in historic understatement, referred to less favorable social conditions in Utah, suggesting the population was made up of "strongly contrasted and picturesque but not easily harmonized elements."13

The Utah Federation of Women's Clubs, organized in 1893, was one forum in which both Mormons and non-Mormons were able to cooperate.14 Croly credits the need for a unifying element as the reason for Utah women's clubs being the second in the nation to organize a state federation.15 These nascent efforts at interaction and harmony between the two dominant groups in Utah fit into the larger women's club movement. Utah women were becoming conscious of the effectiveness of joint action. As one clubwoman somewhat dramatically expounded:

The Reapers' Club .. . is as a small streamlet... as it glides into the larger stream of the State Federation, and with it sweeps into the General Federation of Woman's Clubs, helping to create a mighty force of womanly power which will raise the standard of morals in the world , 16

Utah women, Mormon and non-Mormon, were ready in 1892 to join the stream and sweep forward in the American women's club movement

From 1891 to 1893 Utah experienced a peak in club activity.17 On October 17, 1892, two weeks after her first inquiry, veteran club founder and supporter Emmeline B Wells organized the Reapers' Club at a meeting held in the Woman'sExponent offices.18 The president and the secretary were scheduled to be rotated at each meeting, after the

13 Jennie Cunningham Croly, The History of the Woman's Club Movement in America (New York: Henry C Allen & Co., 1898), pp 1112-13

11 See Madsen, "Decade of Detente," for a study of cooperation between Mormons and nonMormons in the last decade of the nineteenth century One area of cooperation was the kindergarten movement The Salt Lake Association, later the Free Kindergarten Association, was organized in 1892 by Mrs E H Parsons, a Baptist The Utah Kindergarten Association was organized by Sarah Kimball, Isabella Home, Elmina Taylor, Zina D. H. Young, Bathsheba W. Smith, and Ellis Shipp, all members of the Reapers' Club In 1896 the groups united and were successful in obtaining funding for a free kindergarten Public schooling for all Utah schoolchildren, the Utah Council of Women, the National American Woman Suffrage Association, and Utah's participation in the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago were all areas that saw women disregard religious difference.

16 Croly, History, pp 1112-13

16 Romania B Pratt, "Reaper's Club," Woman's Exponent 25 (June 1896): 1-2

17 See Croly, History, pp 1108-17; and Alyson Rich Jackson, "Development of the Woman's Club Movement in Utah during the Nineteenth Century" (honors paper, Brigham Young University, 1992). In 1891 the Woman's Press Club and the Nineteenth Century Club were organized in Utah; in 1892 the Woman's Club, the Cleofan, the Reapers' Club; and in 1893 the Authors' Club, the Aglaia Woman's Club of Springville, and the Utah State Federation of Women's Clubs Other clubs may have been organized that were not members of the federation. In addition, the LDS Relief Society, official church women's organization, was incorporated October 10, 1892 Jill Mulvay Derr,Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher, Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1992), p 145

18 The Woman's Exponent was a bimonthly paper independently published in Salt Lake City between 1872 and 1914 It was outspoken in its support of feminism and suffrage, regularly editorializing and

SaltTake City'sReapers'Club 111

minutes and roll call, but the treasurer was to serve for one year. The rotating chair was common in clubs nationally because it gave more women an opportunity to learn to conduct. Wells was chosen as president with May Talmage secretary and Carrie S. Thomas treasurer.19 The club arranged to meet every two weeks at the Exponent offices in the Templeton Building The Reapers' Club was organized at the height of the Utah club movement, and its correlation to the national literary club movement, as outlined by Blair and Scott, is the focus of this study.

According to Blair, the average literary club was usually a homogeneous group of mostly "mature" women with grown families who shared a common experience, possibly birthplace, school, or religion; however, often the occupation or economic status of the husbands was the major commonality. The women frequently showed determined loyalty to the club, remaining members year after year and introducing their women relatives to membership.20

The Reapers' Club in most ways fits Blair's description of the "average" woman's literary club Reapers' were not only members of the Mormon church, but most shared the common experience of polygamy

reporting on the movements. It also reported on the activities of LDS women's organizations, including Relief Society and Young Ladies Association It received encouragement from church leaders but was financed by subscription See Claudia L Bushman, Mormon Sisters: Women in Early Utah (Cambridge, Mass.: Emmeline Press Ltd., 1976), pp 178-80

19 Wells,Journals, vol 15 (October 17, 1892): 91

20 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, p 63

112 UtahHistorical Quarterly t MWMMM f|iL"\ .;-L*V-.v::•<>••• ':•/•:. Mi ^ ••I^LLL LLfI"" "-" " " ' " '" L^LlLL^Lf#SlwlII;K^:i-;;''>: L^-L*L;i3j?!iL; i • •.. L:.L.. . '::i;m ittlis r::|'f:S!lllV;:t;1.::LLf;:^ iff*® ,••'.;•: " :L ."••;: T:^L-L^:,L:^ L T/j£ Reapers'

m^

Street

South

C/w&

m £/i£ Templeton Building on the southeast corner of Main

and

Temple. USHS collections.

Ninety-one percent of the club members whose personal circumstances could be positively determined were involved in plural marriage as wife, mother, or daughter. This figure is even higher than a recent Salt Lake City study of polygamy suggests.21 Another common experience shared by the Reapers' was birthplace. When the birthplace of fifty of the fifty-seven representative members was identified, the British Isles topped the list with 38 percent, and Utah came second at 30 percent When parentage is taken into account for the fifteen Utah-born club members, nine (60 percent) were secondgeneration British.

Blair suggests that literary club members were mature, but her failure to give figures for her estimate makes it difficult to determine if the Reapers' were average However, the large number of women in their thirties suggests a younger club than the mature collection that Blair describes. A breakdown of the Reapers' membership for the three representative years shows a slightly aging group with an overall average age of forty-five. In 1892 the average age was forty-four, but the largest age group was in its thirties. Eight years later in 1900 the mean age was forty-eight, and in 1907 it was down to forty-five The largest group in both those years was between forty and forty-nine Sample members included both May Booth Talmage, who was twenty-four years old when she joined, and seventy-four-year-old Mary Isabella Hales Home, who had three daughters in the club.22

21 See Marie Cornwall, Camela Courtright, and Laga Van Beek, "How Common the Principle?: Women as Plural Wives in 1860," Dialogue, afournal of Mormon Thought 26 (1993) This study gives polygamous marriage involvement of Salt Lake women as 56 percent in 1860 This corresponds with LarryML Logue, A Sermon in the Desert: Belief and Behavior in Early St. George, Utah (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988)

According to

Salt Take City'sReapers' Club 113

Reapers' Club member Ruth May Fox was born in Wiltshire, England. USHS collections.

22

the 1900 census, May Booth Talmage, 31, was the wife ofJames Talmage, a 37-yearold schoolteacher She had been married 12 years, and one of her six children was alive in 1900 Also living in the household were five children ages 6 months to 11 (identified as sons and daughters of her

Blair suggests that the husband's occupation, status, or income was the most common unifying factor in clubs. Because the Reapers' contained so many prominent Mormon women, the status of both the woman and her husband and/or father was considered. Of the members classified, 76 percent were the highest status, including LDS church auxiliary general board members, wives and daughters of church presidents Brigham Young, John Taylor, and Lorenzo Snow, and representatives of state associations. Wealth was not considered because of the difficulty of determining it with multiple wives.23 Traditionally, plural marriage was reserved for those men who were considered "worthy" and was a prerequisite for higher advancement in the church hierarchy. These figures suggest that the club was representative of prominent Mormon women rather than an association of polygamous wives.

Blair indicates that the majority of club women nationally had already raised their families. The declining birthrate (down to 3.56 per woman nationally in 1900) is seen as one reason for the increased activity in literary clubs.24 In the Reapers' Club the representative women averaged 7.4 children; ten of the women had nine children each and two reported twelve According to the 1900 census, however, the mean number of children under eighteen in the homes of clubwomen was 2.1, and 38 percent of the sample women did not have children eighteen or under in their homes at all. Another 24 percent had only one or two minor children. Although three women had six, seven, and eight children in the home in 1900, these figures show that the majority of women did have fewer children at home (despite the high birthrate) in the years when they were active in the Reapers' Club, conforming to the national pattern.

Club women, according to Blair, showed loyalty to their club and often introduced their women friends and relatives to membership Where this difficult variable could be determined, 40 percent of the women in the Reapers' Club were identified as having relatives in the husband) and a Norwegian servant In 1900 Mary Isabella Hales Home was an 81-year-old widow living with her son-in-law and daughter, Henry C and Clara James Also in the household were Clara's three sons and two daughters ages 4 to 14 Clara was also a club member The James family, including Home, and the Talmage family lived in the same LDS ward, Farmers Ward

23 If a woman or her husband or father had national, state, or churchwide renown she was considered of highest status City, business, or local church prominence was considered of secondary status which included 24 percent of the members

24 Nancy Woloch, Women and the American Experience (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1984), p. 271; and Degler, At Odds, p 325

114 UtahHistorical Quarterly

club.25 When ecclesiastical ward membership and close associates working in auxiliary organizations on local and churchwide levels were added to the relationships considered, all identified women were associated with each other in some way

The names of women's literary clubs usually reflected either the meeting time or purpose, according to Blair. Utah clubs followed this pattern with the Ladies' Literary Club, the Reviews' Club, the Authors' Club (comprised of students of authors not authors themselves), the Historical Club, and others.26 The Reapers' Club was no exception to this pattern. The name was chosen to represent gleaners that "grasp the sickle of industry and enter the fields of science and knowledge to reap and bind into sheaves, golden truths. . . ."27

Generally the clubs required only a small budget because expenses were minimal. According to Blair, the dues usually ranged from fifty cents to ten dollars a year with an initiation fee from two to five dollars.28 The Reapers' paid a fifty cent initiation fee and their annual dues of one dollar were paid semiannually in October and April. In addition, donations were made to help fund special events such as a reception honoring club founder Emmeline B Wells and hosting a reception for the Utah Federation of Women's Clubs. During the years 1898 and 1900 the club records also show donations of ten cents by most members for a traveling library, a state project mentioned in Croly's History oftheWoman's ClubMovement in America. Occasionally, the treasurer recorded fines, usually twenty-five cents, but listed no reasons for the levy.29

25 Relative was determined as a mother, daughter, sister, or sister wife (married to same husband). Other relationships were too involved to take into consideration for this study Unfortunately only obvious relations were identified, and the actual percentage could be much higher

26 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, p 62; Croly, History, pp 1108-17

27 Woman's Exponent, 25 (June 1896): 2

28 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, pp 64-65

29 Reapers' Club Papers, 1892-1912, MSS, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City

SaltTake City'sReapers' Club 115

Mary Ann Burnham Freeze, above, and her sister wife Lelia Tuckett Freeze, were both club members. USHS collections.

Nationally, Blair concludes that in most clubs of the time dues were usually expended on ballots, reports, programs, flowers, postage, and rental of a meeting place.30 The Reapers' were no exception. Club papers include receipts for flowers, postage, supplies, and dues to both the State and General Federation of Women's Clubs. The club rented meeting space at the Woman'sExponent offices from Wells Blair mentions that club badges (paid for by members) and colors, carefully selected by organizers, were standard in clubs of, the era. 31 The Reapers' color was red and the badge was a wheat head. Club members paid twenty-five cents each for their badges and usually wore them to special meetings and functions.32

Newspapers faithfully reported club meetings and special events, giving accounts of topics discussed but also detailing the refreshments, table settings, and flowers, and including the color scheme and the ladies attending. This elitist reporting has been the target of criticism that labels the clubs as cliques and devices for class consolidation as well as vehicles for upward mobility.33 This criticism is valid to some extent but does not negate the value of the clubs to the feminist movement. In fact, women may havejoined for the very reasons that critics decry and, in joining, participated in the move toward civic activity.

The Woman's Exponent was the main news medium for the Reapers' Club. Although some events were reported in Salt Lake City newspapers, the Woman'sExponent printed detailed summaries of club reports as well as the names of members who participated on the programs. Reapers' socials, often held in conjunction with the Utah Women's Press Club, were reported in great detail, including invited guests and eminent women and men who attended.34 Special musical numbers and poetry readings were noted and admired. Mention of the beautiful yard or home of the hostess was usually included along with a description of the flower arrangements and table settings

Blair asserts that although club programs were often described by participants as "universities for middle-aged women" who had lacked the opportunities for education that had later become available to

30 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, pp 64-65

31 Ibid, and Croly, History. Newspaper accounts indicate that colors, badges, and a symbol were important to women club members

32 Woman's Exponent 25 (June 1896): 1; Reapers' Club Papers

33 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, pp. 66, 71.

34 The Utah Women's Press Club was organized in 1892 by Emmeline B Wells Women who had published in ajournal or newspaper were eligible for membership Utah Women's Press Club Papers, LDS Church Archives. See also Linda Thatcher and John R. Sillito, "'Sisterhood and Sociability': The Utah Women's Press Club, 1891-1928," Utah Historical Quarterly 53(1985): 144-56

lief UtahHistorical Quarterly

women, there was no real wish for intense study. The clubs often moved rapidly from one subject to the next, allowing little time for more than superficial knowledge of their potpourri of topics.35

The Reapers' Club fits this description When its formation was announced in the Woman'sExponent it was heralded as a literary club of women who are past school or university life, but who wish to keep pace with the progress being made nowadays, and whose interest in the intellectual and moral development of the world is such as stimulates them to make every effort possible for general enlightenment, moral, spiritual and physical growth.36

In a report to the third annual convention of the Utah Federation of Women's Clubs held in May 1896, Dr Romania B Pratt reported that the Reapers' Club was in its fourth year of "useful instruction." She noted that

the object of this club is social and intellectual development Its design is to cultivate the heart as well as the brain which will form a good mental equilibrium and fit woman not only to shine as a greater light around her own hearthstone, but to be a more efficient custodian of home interests in the wider domain of the world.37

While the Reapers' advertised its intellectual benefits, in reality, along with other literary clubs of the era, it offered a diverse but undemanding program that did not diverge far from the middle-class womanly concern with home, family, and morality. Despite this traditional focus, Reapers' Club members appear to have had better than average training. Often their biographies and obituaries emphasize education, mentioning college and university attendance Four medical doctors, graduates of eastern medical schools, were active members of the club: Ellis R. Shipp, Maggie Shipp, Romania B. Pratt, and Mattie H. Cannon.38

Most clubs, according to Blair, had a fairly rigid structure that included following parliamentary procedure, keeping minutes, and selecting an annual topic for study. Generally the programs consisted of one or two papers, about ten or twenty minutes each, with a short group discussion In addition, current events were discussed, but con-

35 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, pp. 57-59.

36 Woman's Exponent 21 (December 1892): 92.

37 Ibid., 25 (June 1896): 1-2 Romania B Pratt and Parley P Pratt, Jr., were divorced in 1881, and on March 11, 1886, she became the plural wife of Charles W Penrose Christine Croft Waters, "Romania P Penrose," in Vicky Burgess-Olsen, Sister Saints (Provo: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), pp 351, 353 The records of the Reapers' Club and the Exponent article give her name as Piatt

38 Mattie H Cannon was more formally known as Martha Hughes Cannon

SaltTake City'sReapers'Club 117

troversial subjects such as politics, Freud, or Darwin were avoided. Shakespeare's plays, Dante's Inferno, and Browning's poetry were favorite subjects for papers that, while not literary masterpieces, were painstakingly researched, written, and read by club women who conscientiously tried to improve their minds. Every meeting usually contained musical or dramatic performances for variety, and refreshments were considered an important part of the meeting because women who might be too shy to give their views in a formal discussion might be persuaded to express themselves in the more relaxed atmosphere that refreshments produced.39

In the same diary entry that records the organization of the Reapers' Club, Wells outlines club programs Each topic, she notes, will be presented for twenty minutes, followed by a forty-minute discussion of the topic and thirty minutes to discuss current events. Conscious of the celebration of Columbus's arrival in America, Wells assigned the first topic, Queen Isabella, to Phebe Young, and Columbus and Ferdinand were targeted as the next two topics.40 In 1900 the Exponent reported that the Reapers' were studying American history, and earlier subjects had included a study of the American mound builders and noted American writers In addition, the lives of eminent women, Martha Washington, Eliza R. Snow, and Clara Barton, were related. The educational methods of Pestalozzi and Froebel regarding kindergarten work were studied as were "scientific subjects"—electricity and Thomas A. Edison. An "instructive lecture on the construction of the eye" was given by Dr. Romania B. Pratt.41 Reapers' Club papers were carefully prepared by members with the goal eloquently stated by Pratt:

The women of the Reapers' Club do not intend to be gleaners only from the good works of others, but hope through industry to leave to posterity

39

40 Wells,Journal, vol 15 (October 17, 1892): 91

41 Woman's Exponent 21 (December 15, 1892): 92

118 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Dr. Ellis R. Shipp. USHS collections.

Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, pp. 58, 66-67.

a legacy of their own noble thoughts and improved methods of life, that it may truly be said of them that "the world is better for their having lived in it."42

Besides learning skills such as speaking, researching, and writing, American club women gained new confidence and developed a strong sense of sisterhood between members. This feeling of sisterhood was valued by nineteenth-century women and provided them a support network against the isolation of their homes.43 In addition a new awareness of their own worth allowed some of them to branch out into the civic domain. Besides learning to sustain each other, club women learned to support all women They found that women did not have to be silent in public, that they had something worthwhile to say This newly learned articulation and acceptance of women was a boost to the female status. In 1892 when Emmeline B. Wells recorded the following statement in her journal she might have been expressing the feelings of a large number of women in Utah and America.

How strange it seems in view of the past when I was just buried as it were in oblivion that I should ever speak in a public assembly, many changes have taken place in the condition of women in this place in public and private.44

Scott points out that some club women moved from self-improvement to community involvement to national or state political action, while others never left the comfort zone of literary club activity.45 This inconsistency was typical of early women's activities and allowed women to reach a level of comfort consistent with their beliefs. When women were involved beyond the home, they were mostly concerned with civic housekeeping—women and children, education, health, libraries, beautification, and moral issues. These were projects that the women's sphere could be stretched to encompass.

While the study of American history, Martha Washington, and the eye do not seem like steps to feminism, the clubs were indeed taking their first steps in that direction. These club women were determined to improve their condition, and according to Blair, this was a bold concept They had the "audacity to strive for self-improvement in an era that defined ladies as selfless agents devoted to the well-being of

42 Ibid., 25 (June 1896): 2

43 For more on female relationships see Nancy F Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: "Woman's Sphere" in New England, 1780-1835 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), and Caroll Smith-Rosenberg, 'The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in Nineteenth-century America,'' Signs 1 (1975): 1-29

44 Wells,Journal, vol 15 (January 19, 1892): 7

45 Scott, Natural Allies, p 140

SaltTake City'sReapers'Club 119

others."46 Even social climbing was useful in helping women evolve from captives of the "cult of true womanhood" to the public sphere.

Literary clubs taught and educated women, not only in the ways intended but in other important ways They offered a support network of like-minded women to encourage new skills and helped the less courageous of nineteenth-century women to reach out without letting go of the familiar. Literary clubs allowed women to safely stand with one foot in the home while testing the waters of activity outside their domestic world.47

The Reapers' Club of Salt Lake City was a typical nineteenth-century woman's literary club As this study demonstrates, despite polygamy, Mormonism, and a high birthrate, it was very much a part of the American women's club movement and offered Salt Lake City Mormon women an alternative and an addition to suffrage work and home and child care.

46 Blair, The Clubwoman as Feminist, p.58

47 Some Reapers' Club members were very involved with civic and church programs See notes 14 and 17 and Madsen, "Detente." The Relief Society and the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association were both headed by members of the Reapers' Club See individual biographies in Andrew Jenson, Latter-Day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols (Salt Lake City: Western Epics, 1971), and Derr et al., Women of Covenant. Papers of the Salt Lake County Woman Suffrage Association of Utah show that 34 members of the association were also members of the Reapers' Club between 1890 and 1896 On November 15, 1892,just two days before the organization of the Reapers' Club, the Suffrage Association was reorganized with seven new officers Four of these officers—Nellie C Taylor, Adelia W Eardly, Lelia Freeze, and Phebe C. Young—were members of the Reapers' Club.

120 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Three Days in May: Life and Manners in Salt Lake City, 1895

BY DEAN L.MAY

BY DEAN L.MAY

WEDNESDAY, MAY 8,1895, WAS A WARM AND SUNNY DAY The temperature was in the 70s, despite earlier predictions of showers. It was also the day 99 of 107 delegates to the Utah Constitutional Convention gathered to sign the handwritten document in the recently completed City and County Building. This was a triumphant moment, the culmination of forty-six years of strife and tension and sixty-six days of discussions, committee meetings, debates, and political

wrangling

Indeed the delegates were so weary by Monday, May 6, that they had become impatient with the slow pace ofJoseph Smith, the scribe.

"*•'": '"•"•s.-ziym

One of Salt Lake City's early electric streetcars, ca. 1895. Uniformed men are]. E. Peacock and Rudolph Evans. USHS collections.

Dr May is professor of history at the University of Utah

Though typewriters were available, the official ceremonial copy had to be penned laboriously in long hand ("engrossed") in preparation for the signing Smith had fallen far enough behind that an assistant had been hired so the climactic ending ceremonies would not be delayed.

There was evidence of frayed nerves when delegate John Chidester of Panguitch demanded enough copyists to finish the job "as he wanted to go home." Cache County delegate Charles Henry Hart replied that "Mr. Smith was doing a very creditable piece of work. The man called in to assist him was doing botch work and so far as he . . .was personally concerned he would hesitate to attach his signature to such scribbling." The convention members called the scribe from his work to have him tell them how soon he could be finished if he worked alone. The pressures on him were showing too. He replied, "If let alone I can complete the copying of the constitution . . . Wednesday morning by 10 o'clock."

"In your own handwriting?" asked Salt Lake delegate George Squires.

"In my own handwriting, yes sir," the clerk replied. Satisfied, the delegation approved the firing of the erstwhile assistant and moved on to other matters.1

Salt Lakers—indeed, Utahns everywhere—had followed the proceedings avidly in newspapers, which provided much more than the twenty-second sound bites most Americans are fed on now. But there was much more going on that three days in May than just the Constitutional Convention. The Salt Take Tribune, for example, informed its readers of the distinguished guests staying at the city's major hotels, including the mining magnate Enos A. Wall of Ophir, who was a guest at the Cullen, and other named persons at the Templeton and the Knutsford. Imagine the outcry, in our present age of zealous protection of privacy and personal rights, if the Marriott Hotel even hinted at printing the names of its guests. Clearly Utahns of 1895 lived in a world where all were more open to public scrutiny,

122 UtahHistorical Quarterly

1 This paper was originally prepared for a symposium on the Utah State Constitution sponsored by the Utah State Archives with funding from the Utah Humanities Council, and held May 8, 1995, in the Salt Lake City and County Building I am grateful to Jean Bickmore White for information on the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. The paper is drawn principally from the Salt Lake Tribune and the Deseret News of the week of May 6 through May 13, 1895, the week the delegates to the Constitutional Convention finished their labors All references and quotes will be from these sources unless otherwise indicated The account of the debate over the "engrossing" of the document was reported in Deseret Evening News, May 6, 1895.

and privacy was less sacrosanct. Yet some aspects of life for Salt Lakers in '95 seem at first glance almost eerily like ours.

International tensions were in the news on Monday the 6th— more so than the local tensions then being resolved in the City and County Building. "Clouds in the East" was the Deseret News headline, referring to stormy efforts to ratify a treaty ending the Sino-Japanese war. Though we are at times prone to imagine Salt Lakers of any period prior to our own as hopelessly provincial and uninformed about the broader world, the newspapers of the day highlighted international news on the first page and quoted newspapers from Paris, Toulon, Yokohama, and Washington, D.C.

As in 1995, a sensational California murder case was being tried— this one in San Francisco rather than Los Angeles. Theodore Durrant, a medical student, was charged with murdering two people in the Emmanuel Baptist Church, of which he had been a member. Jockeying between prosecution and defense attorneys had begun with "The lawyers for the defense meeting to stem the tide of public opinion by telling us on what lines they will conduct the case."

Political corruption was evident then as now with the governor of Kansas charged with obtaining money under false pretenses And local voters were no doubt reassured by the report from Salt Lake County government promising no new taxes. "No Increase in Taxes" the headline blared "You may put it down," said Selectman Geddes on May 7, "that there will be no increase under this administration of the tax levy."

The pledge was made in spite of the terrible condition of the city's streets The day that Selectman Geddes made his no-new-taxes pledge, Pauline Mahlstrom demanded that the city pay her $20 damages "for injuries sustained by her horse being driven into a hole at the corner of Fourth South and East Temple Streets." Far more ambitious, C W. Bouton demanded $2,550 "in damages for injuries he sustained slipping on a sheet of ice on Second South." Apparently, then as now, pressing problems in providing public services did not deter ambitious politicians from cutting the tax base to support them.

There was concern about the direction of public education, even at a time when almost all school classes, and government meetings as well, including every session of the convention, were opened and closed with prayer. A literary group, the Polysophical Society, had met the previous Saturday at Brigham Young Academy in Provo. There, Mormon leaderJoseph F Smith delivered an extemporaneous lecture

Life and Manners in SaltLake City,1895 123

on "Moral Education" in which he maintained that "the whole aim of our public schools is to educate the mind and develop the body to the exclusion of the proper moral training." He argued strongly that the situation be remedied.

And on Monday Orson F. Whitney and Calvin Reasoner announced publication of a slick new periodical with the titillating title Men and Women. The content did not quite live up to the title, though it is fair to say its tone was definitely avant-garde. The journal promised to:

interpret humanity in all its relations as superior to its institutions, manners, and customs It will be faithful to women, and will endeavor wisely and effectively to give full expression to that world-wide movement in behalf of women which in the providence of God is destined to achieve results of untold importance in the drama of human progress It will advocate equal suffrage in Utah, and whatever else seems to be a normal outgrowth of civilization, and this in full faith that such movement come as legitimate expression of human development and .. . a higher and truer happiness for both sexes

John and Seymour Neff appeared before County Commissioner Pratt on May 7 to answer a charge of "befouling the waters of Mill Creek by allowing drainage to run therein. They pled guilty and as there was not much to the case, were let off on paying the costs. Daniel Hussey entered the same plea to a similar charge and paid the costs B A M Froiseth, a real estate man, and Caroline Kahlstrom answered to a complaint charging a like offense They pled not guilty and their hearing was set for the next Thursday at 10 o'clock A.M." Also on May 7 news was received that the Kearney Bicycle Company of Nebraska was going to open a factory in Salt Lake City or Pueblo, Colorado. The new factory promised to boost the economy, still ailing from the Panic of 1893. "In case Salt Lake will give them a bonus they agree to put in a factory that will give employment to 250 hands and will pay good wages."

Obviously, there was much then that resonates with us today. But while many concerns of the 1890s were similar to ours, much was different as well. The population boom of the 1880s saw Salt Lake City grow 116 percent in a decade. The hard times of the '90s slowed the pace dramatically—to 19 percent. The depression precipitated by the panic was clearly lingering into 1895. Several arrests for vagrancy were made each day during the last week of the convention, and Salt Lake City was proposing "to feed its tramps two meals of bread and water a day."

124 UtahHistorical Quarterly

There were about 50,000 Salt Lakers when the constitution was drafted, making it a major metropolis for its time. Ogden, by contrast, was not yet 16,000, and Provo was a comfortable rural town of 5,700. Most Utahns still lived in small towns. Fillmore, former territorial capital, had just 971 inhabitants Brigham City had reached only 2,500, just half the size of Logan, while in Parowan but 988 persons lived.2

Salt Lake City was thus quite a wonder to the many rural folk of the region. OleJensen had not visited this, the capital of his world, for twenty years when he made the laborious journey from Star Valley, Wyoming, to attend LDS General Conference in 1898 He was astonished by what he saw: "I noticed a great change The first sight being the beautiful temple, with its spires on top, and on one of them a statue of the angel Moroni, with a book of Mormon in his hand."3

The temple loomed tall at the time, above all other city buildings, dwarfing the Deseret Store and Tithing Yard, where the Joseph Smith Building now stands, the old City Hall, the Council House, and even the Salt Lake Theatre. It had been dedicated just two years before. It was probably the exotic, multi-spired temple, more than any other structure, that made Salt Lake City different from all other cities in the West, and Ole Jensen, good Mormon that he was, was appropriately impressed. Though the sacred first caught his eye, he was quick to notice the profane at his feet. The new technologies facilitating city life left him amazed.

The street cars were running on schedule-time with electricity; sidewalks paved with brick, rock, etc and water works in every house I next visited the plant where electricity was generated to light up the city. This is also a remarkable feat. . . . My observations showed that almost everything moved by either steam or electricity. I saw no horses used to work, and only some for touring or pleasure trips.4

Yes, indeed, there were paved sidewalks, if almost no paved streets, and the streetcars were running. All of them had moved from mule to electric power by 1895, the competing lines of the Salt Lake

2 These figures are from U.S Census returns for the years indicated, the 1895 numbers calculated as a straight-line estimate using the 1890 and 1900 returns as the bases The growth rate would surge again to 73 percent between 1900 and 1910

3 Ole A.Jensen Diary, 1898, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City Jensen usually made annual entries in his diary Subsequent quotes from his diary are from the same year and are indicated as such in the text.

4 Salt Lake's first electric plant began operations in 1881 Though the first lines carried direct current and were thus limited in the distances served, in 1890 Lucien Nunn and Paul Nunn demonstrated the feasibility of alternating current hydroelectric plants, which quickly became widely employed in Utah and other parts of the West It is not clear from Jensen's account if he visited the Big Cottonwood Canyon plant, completed in 1895 (and still generating electricity in 1996), or another See Obed C Haycock, "Electric Power Comes to Utah," Utah Historical Quarterly 45 (1977): 174-87

Life and Manners in SaltLake City,1895 125

Railroad Company and the Salt Lake Rapid Transit Company extending south to Sugar House and east to Fort Douglas, giving urban life new dimensions and patterns that were rapidly transforming the city.5

The term "rapid transit" carried an eloquence for our grandparents that we, with our Hondas, Toyotas, and Fords, have long since forgotten. Cities had traditionally been limited in scale by the sheer logistical problems of moving people and goods around in them. As cities grew their denizens were, in fact, at a disadvantage compared to country dwellers in that only a few city folk had the pasture and hay needed to keep horses and the wealth needed to buy a carriage. And even if they did, a trip out required a thirty-minute hitching of team to carriage before it began Urban life was thus more centered in the local neighborhood than now, and ward stores or neighborhood mercantiles still held the local clientele.

The streetcar, introduced with mule-drawn cars in the 1870s, changed all that. It offered relatively inexpensive, safe, and reliable transportation. By 1895 it had become a necessity of urban living. When Allen Hilton confronted his court-appointed guardian on May 7, his complaint was that the guardian had refused "him money for the most ordinary expenses, going so far as to deny him street car fare." The same day four boys were arraigned when caught in the apparently common act of stealing a ride on a streetcar. They pleaded guilty and were allowed to go.

The streetcars created suburbs by making daily travel to the city center easy and practical Cities could now grow to dimensions previously impracticable and unworkable People could conveniently venture out of their intimate neighborhoods and temporarilyjoin a more anonymous stream of humanity. To a society long confined by the mutual watchfulness of neighbors, the prospect of "going out" was exhilarating. Frequent shopping trips to the downtown Auerbach's or ZCMI department stores became pleasant occasions. One went not only to shop but to see the crowds and to be seen by them, a downtown excursion often necessitating dressing in Sunday best

The streetcars made possible a variety of amusements hitherto less accessible. There were three driving parks (horse racing tracks) in Salt Lake City—Utah, Jordan River, and Calder's. Visiting one of them, you might be lucky enough to bet on one of H. W. Brown's

126 UtahHistorical Quarterly

5 Thomas G Alexander and James B Allen provide valuable information on the growing infrastructure of Salt Lake City in the 1890s in Mormons and Gentiles: A History of Salt Lake City (Boulder, Colo.: Pruett Publishing Company, 1984), pp 125-62

horses—Dan Velox, Jassey, or Miss Foxie—so well known they even raced in Denver Top sprinters at Calder's Park included Mischief, La Belle, and a brown four-year-old, Aubertine.

A Sunday afternoon amidst the crowds of Saltair, Garfield Beach, or Lagoon became a favorite pastime. And these were not just places where kids hung out. Lovely photographs were taken in 1895, for example, of a cakewalk at Lagoon for couples over seventy, all carefully protecting themselves from the sun with hats and parasols of the type Auerbach's had on sale for 70 cents, and obviously having the time of their lives. The photographs show young and old alike dressed in somber-toned woolens, the women constrained by tight corsets and their white blouses showing lace-trimmed leg-o-mutton sleeves. Tribune editors by 1895 were poking fun at the concept of the "New Woman," but the daring fashions had not yet reached deeply enough into Salt Lake City for women to begin bobbing their hair, shedding their corsets and petticoats, or raising their hemlines.

The men wore ill-fitting ready-made wooljackets over unmatched crumpled trousers and ample, dark shoes or boots. Men and women wore hats, and many, in addition, held a parasol. They understood better than we that in this rarefied air the sun can be an enemy.

Life and Manners in SaltLake City, 1895 127

This photograph in USHS collections is captioned "Watching the result of the Cake Walk, Old Folks day, Lagoon, f uly 6th, 1898."

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention were no doubt similarly clad when they visited Saltair on Monday afternoon, May 6 The planned outing had caused a bit of stir at the convention that morning. Delegate David Evans of Weber County did not want to go, arguing that the Convention could not spare the time. "There is no doubt about it," chimed in another delegate. He was countered by delegate Squires, however, who said there "was very much doubt." David Stover of Tooele County agreed, insisting that "he wanted a salt water bath." The argument seemed persuasive, for the vote was forty-five in favor and twenty-two against, hopefully not a reflection on delegate Stover's personal hygiene The delegates and their wives boarded the train in Salt Lake at 2:15 P.M The ride included a ten-minute halt "at the salt fields during which the pyramids of glistening saline were admiringly looked upon and praised, as they always are by those who see them for the first time." A special dispatch to the DeseretNews reported at 3:15 that "the excursionists are now scattered from the first floor of the pavilion to the tower. So far none of them have dared to brave entering the water, and no formal program is being observed. The party is expected to reach Salt Lake on the return trip about 5 P.M." Returning on schedule, they refreshed themselves in preparation for the Constitutional Ball at Christensen's Hall that evening The dance card offered "a 'Woman Suffrage' schottische, a 'Prohibition' two-step, a 'San Juan'jig quadrille, and 'Where are we At' Virginia Reel. The grand march was 'Hurrah for Statehood.'"

A plethora of other amusements were available as well. On Monday the 6th the Politic Debating Club held a mock trial, a farce where a young man was suing another for stealing his date, a Miss Hettie Watson, while on an outing at Saltair. The jury found in his favor, and the judge concluded that "the plaintiff recover the amount of cold cash claimed [presumably the cost of admission], the defendant to have and retain the affection already in his possession, while to the court should be turned over by . . . Hettie Watson all the love and affection over which she had any control not actually in the possession of the defendant."

On Tuesday the 7th the Philopathian Debating Club announced a contest with the Washington Debating Club for the next Thursday evening at the rooms of the Philopathian Club at 375 West Second South on the question "Resolved, That women should have the right of suffrage," a pressing national question that the Constitutional Convention had already decided for the soon-to-be state of Utah.

128 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Monday evening the Chinese pupils of the Congregational mission entertained at the Congregational church with "psalms, songs, recitations and school exercises. The boys taking part did remarkably well, considering the difficulty in mastering the English language."

Newspapers announced each day a long schedule of fraternal and sororal meetings. At least one of six different Masonic groups had a meeting every day of the week. Fraternal brothers could attend one of ten different Odd Fellows gatherings every week night. Six Knights of Pythias chapters met at 7:30 in Castle Hall on Richards Street, one meeting every week night A group called the Red Men also met regularly There were, in addition, ladies' auxiliaries for all these groups, and other women's clubs as well, such as the one called the "Rathbone Sisters."

The Most Reverend Archbishop Gross of Oregon and the Right Reverend Bishop Glorieux of Idaho had visited Salt Lake City on Sunday the 5th, celebrating High Mass in St. Mary's Cathedral. Mormon Tabernacle services that day included speeches by church historian AndrewJenson and George Q Cannon Jenson spoke on the importance of keeping personal records Cannon "emphasized the importance to the Saints of keeping careful records of their private lives as well as their work in the ministry of the gospel." Kate Hodge, a niece of convention delegate David Evans, sang a solo at the Methodist Episcopal Church that night and was planning to sing the waltz song from Gounod's opera Romeo andJuliet at the Marchesi Club concert on Monday. Prominent women's rights advocate Susan B. Anthony and the Reverend Anna Shaw were expected to arrive in Salt Lake City on Sunday the 12th to speak at meetings during the next three days

And of course there was the theater, with performances of a comic opera, Priscilla, about the courtship of Miles Standish, at the Salt Lake Theatre. "The BiMetallic Blacks Operatic Minstrels" were appearing at the Opera House, and the Wonderland Theatre advertised "two big shows" each evening and offered special performances for children and ladies

Critics of the time were, to put it mildly, blunt. A Mrs. Knowlton, who played the part of Priscilla "sang in a voice [that] is very light and sweet," wrote the DeseretNews critic rather gently, but then he inserted the dagger. Her voice "seemed to need a supporting instrument in the orchestra to hold it on the key." Mr. Jennings's part as governor of Plymouth "was well made up and well acted, but execrably sung Why

Tife and Manners in SaltTake City,1895 129

the director should have Mr.Jennings sing at all, is past understanding. The music should be cut out bodily."

There were less wholesome amusements On Sunday evening police descended on a Third South lodging house "operated upon a plan European, and from one of its apartments dragged an erring twain, who were registered at headquarters asJohn Thompson and Ada Smith." Thompson was arrested for frequenting, Smith for staffing, and the proprietor for running a house of ill repute.

On Tuesday night alone, thirty-eight defendants were brought into the police court. Joseph Ward pleaded guilty to charges of keeping a gambling house and was fined $25 The police also arrested J Doe Seeley for disturbing the peace Seeley was said to have thrown a rock at a neighbor's house, but he maintained it was his wife who threw at a dog. AndJennie Smith and Clara Cox were arrested, apparently regulars in this particular night court, "and left the usual amount for their appearance."

A number of others were run in for drunkenness. Also arrested were youths Ben Davis,John Thompson, Charles Dennis, and Frank Porter "for bicycle riding on the sidewalk in the restricted district."

130 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Salt Lake Theatre. USHS collections.

J. C Nixon was arraigned on a charge of disturbing the peace and riding a bicycle without a license. Four others were fined $2.00 each for violating the bicycle ordinance, all of which seems a distant anticipation of present laws directed at skateboarders.

Our Star Valley friend, OleJensen, was ready for the cyclists, who were pioneering avidly their own non-polluting form of personal transportation "I also saw many people, both men and women, riding the bicycles with great speed," he said, "but this did not surprise me as I was posted previously about the invention."

Cycle shops were flowering like board and blade shops in Salt Lake City today, the cyclists obviously seen by the staid citizenry as a threat to public safety The Salt Lake Cycle Company was offering $500 in prizes to winners in a fifteen-mile Handicap Road Race to be held on Decoration Day, May 30, with the first prize being a much-coveted "Cleveland Swell Special Bicycle." The Tribune reported that "the bicycle clubs of the city are working hard for a wheel path in Liberty Park, with a fair prospect of success." A special committee visited the park and decided it would be easy to make an eight-foot bicycle path like one already in use at the Hot Springs: "It is said in support of the plan, that it would make a very attractive resort for the wheeling fraternity, would clear the drive-ways of bicycles and add to the public pleasure very materially." Apparently, as often happens when a novelty appears, the old-time citizenry distrusted the new device.Just as skateand snow-boards seem to non-boarders a threat, even when injuries and or damage do not exceed those of other conveyances, so the bicycle seemed dangerous and frightening to those who moved about on horses or trolleys.

All this and much more was going on in Salt Lake City during those final days when the Constitution was being approved and signed. The delegates, many from quiet villages, no doubt were delighted to get back to things at home, leaving the capital city aboard one of the twenty or so railway trains that ran each day.

Salt Lake City was in 1895 a bustling place, possessed of a boldness and openness that in many ways surpassed our city of today. Electric trains and personal transportation were changing in fundamental ways the way people thought about themselves and their relationship to rest of the world. Quiet neighborhoods no longer could contain them; and in the broader city they came out to see, they found a casual conviviality and easy-going pleasures they had never known

Still, as Paul Simon and Art Garfunkle so eloquently put it, "A

Tife and Manners in SaltTake City,1895 131

man he hears what he wants to hear and disregards the rest." What Ole Jensen saw of the city was there too:

I attended all meetings of the Conference and gladly received all of the instructions; everything moved orderly, people dressed neat but plain I never saw anyone intoxicated, nor heard any profanity while in the city, although it may of existed.

Nonetheless, he could dimly see the new century crashing in:

I noticed there was a similitude of dress with our country people, only golden cased spectacles were worn by old and young, I supposed for pride The city seemed full of merchandising of every kind On every corner were solicitors selling candy, bananas, and etc A good meal could be had for 15^; and a bad for 25^.

Much seems the same, but in fact all has changed, in the century since Utah's Constitution was completed in Salt Lake's City and County Building, on May 8, 1895.

132 UtahHistorical Quarterly

Lewis Leo Munson, an Entrepreneur in Escalante, Utah, 1896-1963

BYVOYLE L. MUNSON

BYVOYLE L. MUNSON

I F MY FATHER, LEWIS LEO MUNSON, KNOWN AS LEO, had been born in 1826 instead of June 29, 1896, he would have been happy owning a trading post at a critical junction of two pioneer trails. After starting small, within twenty years he would have offered every conceivable service travelers needed, with each of his children big enough to work involved in the delivery of those services. In addition, he would have known of the opportunities at other posts along the trail, thinking that

Dr Munson, a retired educator, lives in Bountiful, Utah

t _ '" - ', p. • M; :i%iMM'r '•**' •'•'Wf;':-.:i-

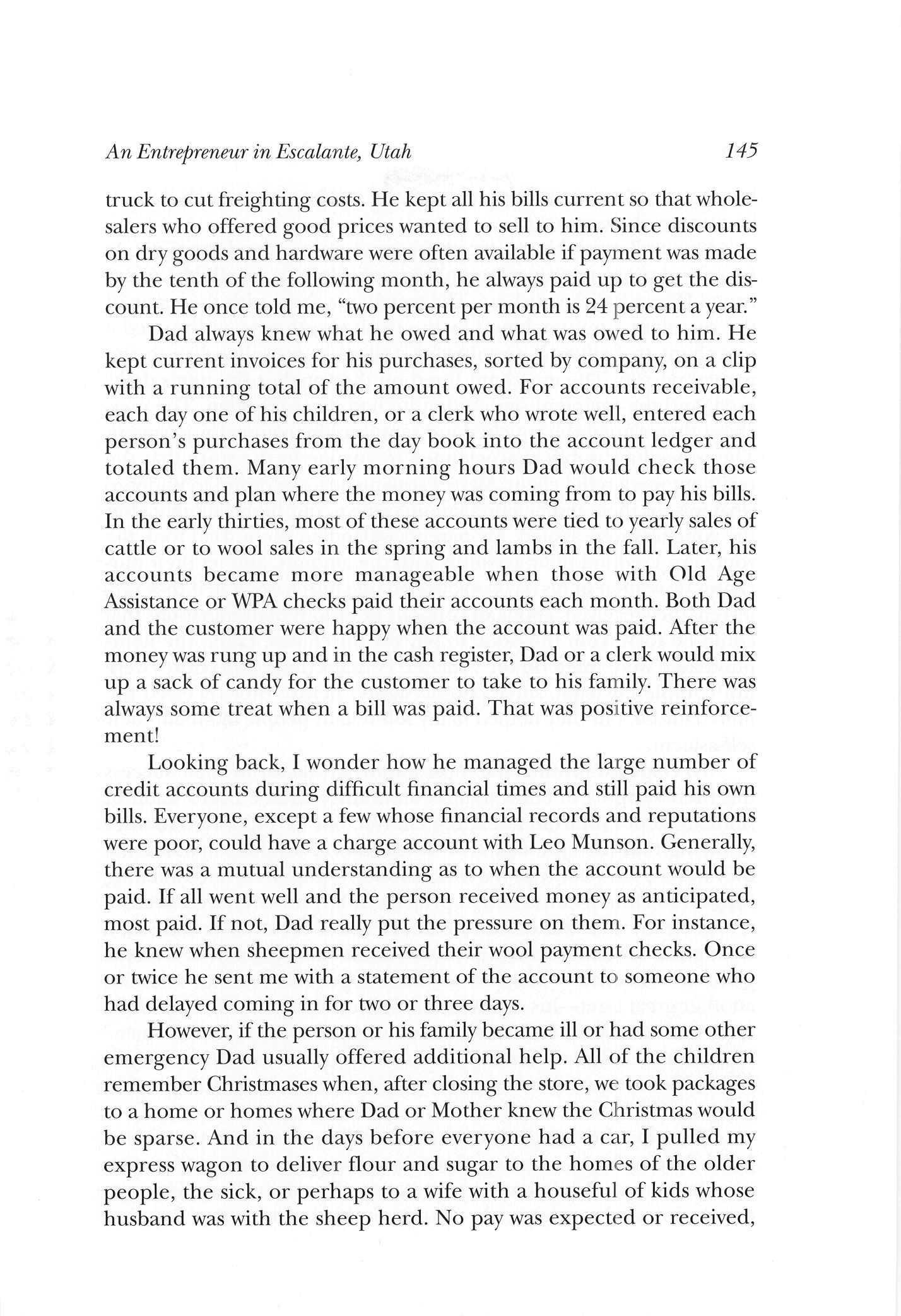

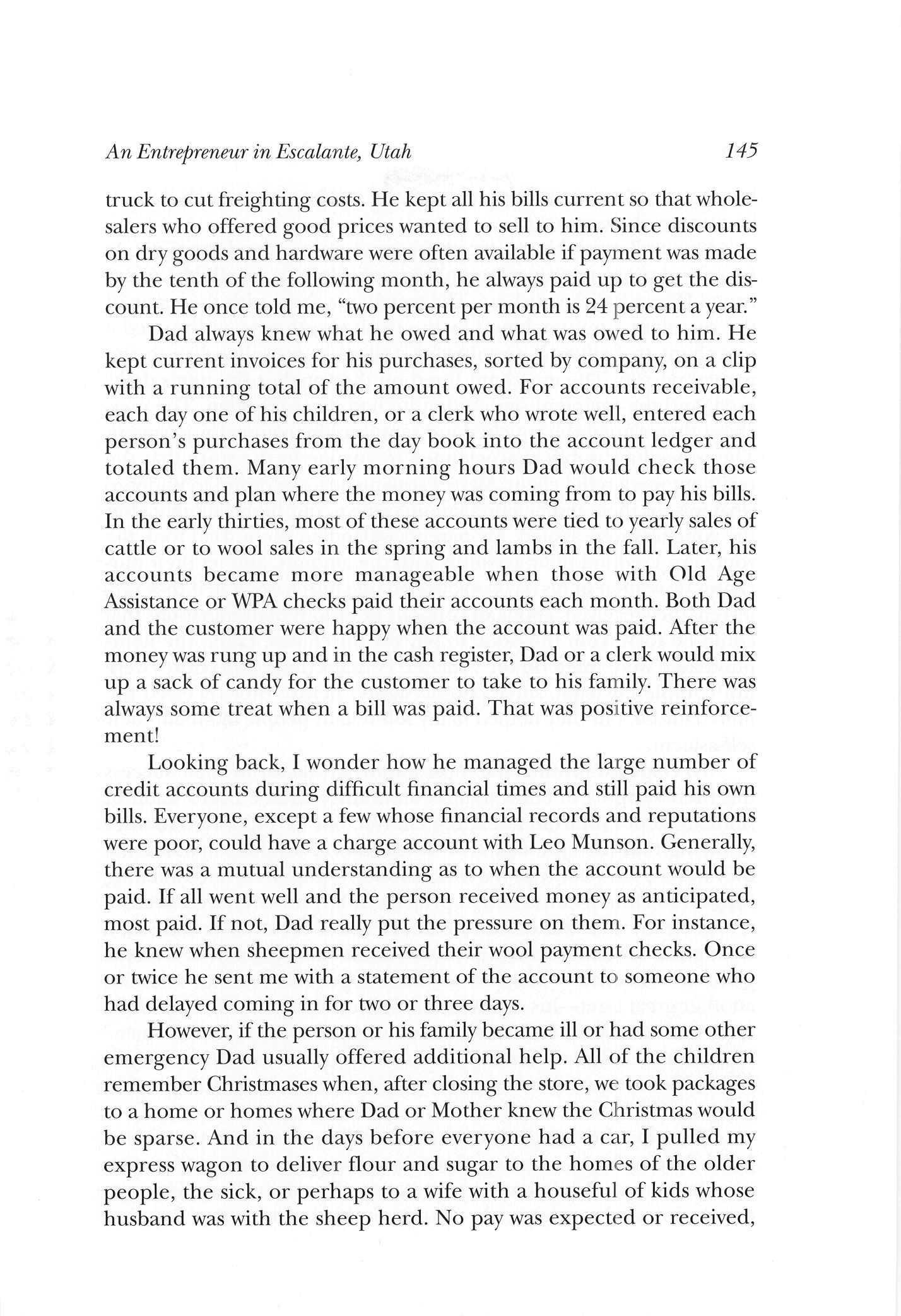

This U.S. Forest Service photograph of Escalante's Main Street shows Leo Munson's store. USHS collections.

some day his children might want to buy one of these locations and provide needed services there

Leo, the eldest living child of Lewis T. and Emma A. Morrill Munson, was born in the year of Utah's statehood in a one-room log cabin in the mouth of Circleville Canyon approximately two miles south of Circleville, Piute County. During the eleven years the Munsons lived in this location, their family Bible records the births of two brothers and two sisters.

In 1907 the family moved into "a nearly new, nine room frame house in Tropic."1 Tropic, Garfield County, was not the luxuriant land the name implies. I remember hearing my parents laugh at a story about a relative who was working near the rim of Bryce Canyon A tourist looking east saw Tropic and its bare surroundings a few miles distant. "What can you ever grow in a place like that?" he asked. The Tropic resident replied, "Wormy apples and kids."

But the Munsons' orchard produced bushels of good apples and other fruit The four cultivated fields produced feed for the horses and milk cows, plus some corn and other grain for the family Range cattle furnished meat and some cash, augmented by wages from jobs Lewis found. By careful management of their resources they lived well.

Dad's sister Ila wrote that when Leo finished the eighth grade, the school principal came to their home and told the parents that "Leo could outdo the teachers, and the principal, in mathematics, spelling, and English." As a result, he was offered a scholarship to attend high school in a larger town. However, his parents thought he was too young to leave home, so he attended the eighth grade again because he was so anxious to learn.2 Ila added, "from that time on Leo showed his potential of being a leader. When our Father would go away to work to provide for his family, Leo would lead out, and with the help of our mother, and his younger brothers, Forest and Levar, was able to keep the work on the farm rolling quite smoothly." Moreover, "While other men sat by the store and whittled wood and visited, Leo would be doing any kind of work he could find to make money."3

One of thosejobs was selling Wearever Aluminum Dad once told me of the first home where he gave a full sales presentation He took each item from his carrying case, pointing out the quality of the construction, how easy each pot was to use and clean, and how suited it

3 Ibid

134 UtahHistorical Quarterly

1 Ila Munson Pollock, "Life's Story," p 1, copy of MS in author's possession

2 Ila Munson Pollock, "Leo and Hortense Munson," The Cope Courier, August, 1976, p 7

was to the preparation of delicious foods. Soon he had pots and pans all over the floor. When it came time to leave, he was unable to get everything back in his case. But he persisted and did well selling aluminum cookware.

On April 4, 1917, Dad married Hortense Cope in the Manti LDS Temple. Although they differed in many ways, for forty-six years they supported each other in rearing and providing for their nine children: Voyle (1919), LoRee (1922), Evelyn (1924), Lasca (1926), LoRell (1928), Orpha (1930), Lloyd (1931), Howard (1934), and Vaunda (1936), plus Dad's youngest brother, Pratt (1920), who lived with them part-time for several years and full-time from 1935 to 1943.

In the spring of 1918 my parents began farming some undeveloped land in Losee Valley, east of Tropic. Six days a week they lived in their one-room log house, building corrals, grubbing brush, plowing, planting, cultivating, irrigating, and reaping a meager harvest from the blue clay soil. Saturday afternoons they went to town for barrels of drinking water and other supplies and stayed for church. Winters they lived in the Lewis Munson family parlor.

In 1921 they moved into a two-room frame home on a Tropic lot with a good orchard. Dad supplemented his farm income by building wood racks in his blacksmith shop, hauling wood, working on the Tropic Reservoir, selling fruit, custom cutting grain with his binder, or by any means he could find.

When I was five or six I accompanied Dad with a load of apples to Panguitch. He divided the wagon box into compartments and covered the bottom with straw. The brilliantly red, almost black, Ben Davis apples filled one compartment, the Pearmaines another, and perhaps other kinds in another. We camped the first night in a small

An Entrepreneurin Escalante, Utah 135

Leo and Hortense Munson, 1938. Unless credited otherwise, photographs are courtesy of the author.

log cabin at a sawmill in Red Canyon, rolling our bed out on a dirt floor In Panguitch the next day Dad showed the beauty and taste of the apples to prospective buyers and soon sold the load. Traveling home we stopped at the sawmill for a load of lumber. During the night rain and mud dripped through the roof onto our bed. By sunrise we were headed for home. Going down the steep "dump"4 dugway, the lumber slid forward and jammed into the rear of the horses. Frightened, they tried to run away, but Dad turned them into the inside bank so they had to stop Then he spoke softly to them and patted them until they quieted down. He adjusted the load, tied it more securely, and we arrived home without further difficulty.

When my sister Evelyn was born on August 27, 1924, Mother wrote, "As our family grew, Leo could see he had to do something besides farming. He became a traveling salesman in his spare time. He sold women's dresses, silk hose, [men's] socks, suits, and neckties He was a good salesman and made good at it going to all the adjoining towns."5 Later, he added Stark Brothers Trees to his line. He and two other men from Tropic sold products on a circuit south to Kanab, east to Escalante, and north to Beaver. But neither Leo nor Hortense liked him to spend so much time away from home.

InJuly 1926 Leo and his brother-in-law,J. Austin Cope, who had a store in Tropic, took their eldest sons and went to Escalante to sell hot dogs, hamburgers, soda pop, and other refreshments at the 24th of July celebration. Mother went along, noting, "While there, Leo decided to buy a little store . . . sort of an ice cream parlor and butcher shop."6

Although Mother wrote, "Leo decided to buy," she was certainly involved in making the decision, for the two of them committed all they had to the new enterprise. ByJuly 30 the family goods were loaded on a truck and on their way to Escalante That same night they unloaded their possessions in part of a rented house near the little store. How difficult it must have been to sever ties with both of their families and their lifetime friends in Tropic. Their moving so quickly is congruent with an axiom Dad sometimes quoted, "It is easier to take off a dog's tail in one whack than to cut it off a piece at a time."

Dad was not a complete stranger to Escalante residents because

6 Ibid

136 UtahHistorical Quarterly

4 To residents of Garfield County, the road from the top of the Bryce Canyon Plateau down into Bryce or Tropic Valley was known as the "dump."

5 Hortense Cope Munson, "History of Lewis Leo Munson," copy of MS in author's possession.

An Entrepreneurin Escalante, Utah 137

many had purchased merchandise from him during the past two years. He knew that Escalante people had more money to spend than those in most southern Utah towns. The Sanitary Meat Market was the only source of fresh meat in Escalante, and he could also expect to sell ice cream and sandwiches to some of the town's thousand residents.

The market had no display case or automatic refrigeration The meat hung in a walk-in boxjust large enough for one beef, one pork, a keg of wienies in heavy brine, a few sides of salt pork, and some smoked bacon A tin-lined box along the north side held a piece of ice for refrigeration. Copper tubing drained water from the melting ice onto the ground between the back of the meat market and the Star Amusement Hall

During the summer ice came from the South Ward Relief Society ice house. I remember taking my express wagon to the ice house and helping a lady struggle to remove a piece of ice from the sawdust and to weigh it using a steelyard After a careful trip down the Meeting House Hill, I swept the ice and then rinsed it with a bucket of water to remove the clinging sawdust. Then it was a man's job to get it into the cooler Within a short time, though, Dad rented the ice house and "put up" his own ice. He froze ice cream in a hand-turned freezer.

Since the nearest packing plant was in Salt Lake City, Leo bought local cattle and pigs and butchered his own meat. He had no problem with government grading and no trouble selling grass fat beef or pork that had been fed a little dishwater along with its grain or corn. The carcasses were separated into primal cuts. If a customer wanted a Tbone steak, the butcher wrestled the loin onto the block, cut the desired amount with the steak knife and hand meat saw, and placed the cut onto a piece of waxed paper on the scales, which gave the weight and helped compute the price. When a customer wanted salt pork or bacon, the butcher placed the slab on the block and cut and wrapped a chunk near the desired size. The process worked when the butcher was on duty, but it was a terrible struggle for Mother when she had to mind the store. Once Edward (Teddy) Wilcock, who owned the largest store in town, came for some T-bone steak Doing her best, she brought out a piece of the neck and cut the requested number of steaks. What Wilcock thought of the steaks is not known, but the incident became a family tale repeated for many years

The little building, located east of the pool hall on the north side of Escalante's Main Street, soon underwent some changes. Leo bought an adjoining building and stocked groceries. Having limited

capital, he ordered Blue Pine groceries every night from John Scowcroft and Company to be delivered by mail. The order would arrive within three to five days It was an exciting day for the family and of great interest to the townspeople when Leo had a cement slab about 12 feet wide poured in front of his store, the first cement sidewalk on Main Street. By then merchandise was coming by freight to Garfield County, and before long Leo had bought his own truck and was making regular trips to Salt Lake His brother Levar was the store butcher and truck driver.

Onjuly 15, 1929, three months before the stock market crash that heralded the Great Depression, we moved into a new brick home, the second in town to have a bathroom and running water. By May31, 1931, the store was in a new 40-by-60-foot brick building west of the pool hall.

In 1931 Escalante was a relatively isolated community where most people lacked transportation to travel very far and the roads discouraged such travel. In 1932, of my five closest friends age thirteen and fourteen only one had been as far as Marysvale, the railroad terminus, some ninety miles away. Some had never been sixty miles to the county seat in Panguitch So, until the end of World War II the town's isolation encouraged shopping at home.

138 UtahHistorical Quarterly

The Munsons' brick house in Escalante. Courtesy of Vaunda M. Willis, Glenwood, Utah.

But Dad had to compete with three other stores that had been operating longer and were better established and with the catalogs of Sears, Roebuck, Montgomery Ward, and the Chicago Mail Order Company. Most ranchers went to other towns to sell their livestock or wool, and with a check in their pockets they were ready to buy there Also, the truckers that freighted wool and cattle were always happy to pick up flour, sugar, and other staples for the "big city price" plus freight. Many Escalanteans bought their yearly or at least a six-months' supply of these items in the spring and fall.

Dad's business expansion came at a time when Escalante's economic conditions had begun deteriorating. Many residents ran sheep or cattle on mountain ranges supervised by the Forest Service in the summer or on public lands in the desert areas in the winter. Periodic summer floods that sometimes overran the banks of Escalante Creek and Harris Wash resulted from the overgrazing west and north of the town. But government reductions in livestock numbers incensed the owners and reduced their income