2 O I—i ^D <C GO O r d d w 1NS

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

MAXJ. EVANS, Editor

STANFORD J. LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN S. ROGERS, Associate Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

AUDREY M. GODFREY, Logan, 2000

LEE ANN KREUTZER, Torrey, 2000

ROBERT S MCPHERSON, Blanding, 1998

MIRIAM B MURPHY, Murray, 2000

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora,WY,1999

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 1999

GENE A. SESSIONS, Ogden, 1998

GARY TOPPING, SaltLake City, 1999

RICHARD S VAN WAGONER, Lehi, 1998

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah's history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, SaltLake City,Utah 84101 Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly,Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly Newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20.00; institution, $20.00; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or over),$15.00;contributing, $25.00;sustaining,$35.00;patron, $50.00;business, $100.00

Materials for publication should be submitted in duplicate, typed double-space, with footnotes at the end Authors are encouraged to submit material in a computer-readable form, on 3K inch MSDOS or PC-DOS diskettes, standard ASCII text file For additional information on requirements contact the managing editor. Articles represent the views of the author and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage ispaid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to UtahHistoricalQuarterly, 300 Rio Grande, SaltLake City,Utah 84101

mm )ZnttA(XX HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y Contents SPRING 1998 \ VOLUME 66 \ NUMBER 2 IN THIS ISSUE 99 ROLLINJ. REEVESAND THE BOUNDARYBETWEEN UTAH AND COLORADO EDITED BY LLOYD M PIERSON 100 DR ELIZABETH TRACY:ANGEL OF MERCY IN THE PAHVANT VALLEY EDWARD LEO LYMAN 118 JAMES T. MONK: THE SNOW KING OF THE WASATCH CHARLES L. KELLER 139 "EL DIABLO NOS ESTA LLEVANDO": UTAH HISPANICS AND THE GREAT DEPRESSION JORGE IBER 159 IN MEMORIAM: S. GEORGE ELLSWORTH, 1916-97 EVERETT L. COOLEY 178 BOOKREVIEWS 181 BOOKNOTICES 191 THE COVER Four Corners, (n.d.). USHS collections. © Copyright 1998 Utah State Historical Society

JEAN BICKMORE WHITE Charter for Statehood: Fhe Story of Utah's State Constitution HENRY WOLFINGER 181

GARY TOPPING. Glen Canyon and the San Juan Country W. L. RUSHO 182

CAROL CORNWALL MADSEN, ed. Battle for the Ballot: Essays on Woman Suffrage in Utah, 1870-1996 .EDWINAJO SNOW 183

COLLEEN WHITLEY, ed. Worth Fheir Salt: Notable but Often Unnoted Women of Utah .LYNN WATKINS JORGENSEN 185

VIVIAN LINFORD TALBOT. David E. Jackson: Field Captain of the Rocky Mountain Fur Frade JOH N W. HEATON 186

GREG MACGREGOR Overland: Fhe California Emigrant Frail of 1841-1870

JAY HAYMOND 187

JAMES H MAGUIRE, PETER WILD, and DONALD BARCLAY, eds. A Rendezvous Reader: Fall, Fangled, and Frue Fales of the Mountain Men, 1805-1850 JOH N D. BARTON 188

SALLY ZANJANI. A Mine of Her Own: Women Prospectors in the American West, 1850-1950

JUDYDYKMAN 189

Books reviewed

May Procession at the Guadalupe Mission, 1943. Courtesy ofArchives of Catholic Diocese of Salt Lake City.

In this issue

Every time and place has a few saints and scoundrels, and so does this issue of the Quarterly. Of course, nobody is really all one or the other, but according to local memory in Millard County, Dr. Elizabeth Tracy came close. The doctor— well-bred, gentile, and forty years old—came out to the near-empty "North Tract" to marry a crusty Irish judge In short order she made herself indispensable to the entire community, and not only because of her great medical skills.

Near the other end of the spectrum, the brash James Monk used a whole arsenal of creative techniques to build his own fiefdom among the mountains and miners of Big Cottonwood Canyon. Inevitably his audaciously built house of cards collapsed as he lost his mines and what money he had He also lost one last battle: he had to go to church.

As fascinating as such characters are, the past is largely made up of ordinary people figuring out how to live in an uncertain world Too many of these stories go untold, but in this issueJorge Iber unearths some as he describes how the Great Depression affected Utah's Hispanics. Although all of them faced overwhelming challenges, individual experiences varied, and so did responses The article shows, however, that most Hispanics found strength in their common culture as they worked to maintain community.

Starting the issue off is the written report of the man who faced the daunting task of surveying the southern Utah/Colorado boundary. The work certainly didn't resemble a survey job in, say, Kansas, but Rollin Reese and his crew struggled through canyons, rivers, and mountains to get the job done Along the way Rollins recorded his impressions, giving us a clearer sense of a time and place—which, in fact, is what all the stories in this issue do

We end with a personal tribute to S. George Ellsworth, recently deceased Fellow of the Utah State Historical Society It is a well-deserved accolade to a giant in our profession—a man who, in the eyes of Utah historians, achieved sainthood a long time ago.

Rollin J. Reeves and the Boundary Between Utah and Colorado

EDITED BY LLOYD M. PIERSON

TH E LAND SURVEYS OF THE STATES AND TERRITORIES of the United States have been important ever since day one. As states and territories were designated from the original thirteen colonies and from purchased and conquered lands, and as settlers immigrated to claim public lands, federal land surveyors were almost on their heels, sometimes ahead of them. Working according to various federal laws that determined new state and territorial boundaries, surveyors—both government and contract—eventually covered the nation.1

Lloyd M. Pierson is retired and lives in Moab, Utah. He served eighteen years with the National Park Service as ranger, archaeologist, and superintendent and nine years with the Bureau of Land Management as staff archaeologist.

Complete copies of the Reeves report reside in the land offices of the Bureau of Land Management in Salt Lake City and Denver The original is in the National Archives (cartographic records of the General Land Office, Record Group 49) A copy was kindly provided the author by Jerry Thomas and Brad Groesbeck of the BLM in Utah

1 After the Land Ordinance of May 20, 1785, surveyors used the rectangular survey system as opposed to the metes and bounds surveys of the original thirteen states At the time of Reeves's survey, the U.S General Land Office wasresponsible for managing public lands, and besides setting boundaries, the surveys were designed to provide information that would assist in management decisions

A transit, used by surveyors to sight the "target" on a surveying rod. All photos USHS collection.

A transit, used by surveyors to sight the "target" on a surveying rod. All photos USHS collection.

RollinJ Reeves was a contract surveyor, paid by the mile, experienced and, as is apparent from hiswritings, educated, intelligent, and perceptive. His 1878boundary survey between Colorado and Utah was induced, in part, by Colorado statehood in 1876 and by the settlement of southeastern Utah.2 As required by his contract, Reeves made a detailed record of his monumenting and surveying work; in addition he provided a summary of his observations, many of which have historical value, since little is known of the area he was surveying in the late 1870s.

Southeastern Utah and southwestern Colorado were in the first period of settlement when Reeves did his boundary survey. There is little in the historic record regarding the life and times of the settlements he visited; no newspapers were extant in the region at that time. In fact, Reeves's report is one of the few documents about southeastern Utah prior to the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition of 1880; his observations are therefore quite valuable.

In his report, Reeves provides information about little-known roads and mail routes of the period, which helps us to understand the settlement of the region He also provides descriptions of early residents, including Peter Shirts, an early settler of the SanJuan; the settlers at La Sal, Utah; Utes and Navajos; and area ranchers near the Big Bend of the Dolores River. In addition, his evaluation of the economic possibilities of the area are cogent and quite interesting. Apparently, the type of document Reeves produced has received little attention from researchers. Yet Reeves's attention to details— given at the government's insistence—indicates a rich resource of little-used material lying in the archives of the General Land Office.

Reeves's handwritten field notes consist of three basic parts: a short introduction detailing his arrival at the starting point, a mile by mile record of his survey, and a detailed summary of his observations along the boundary line and vicinity.

COLORADO-UTAH BOUNDARY LINE FIELD NOTES 3

[OF U.S SURVEYOR ROLLIN J REEVES, 1878]

Havingbeen designated bythe Honorable Secretary of the Interior on the 11th ofJulyA.D. 1878to execute the surveyof the boundary line between the State ofColorado, and the Territory of Utah, in accordance with the Act

Colorado-Utah Boundary 101

2 Colorado's Enabling Act of March 3, 1875 (18 Stat 474) designated the western boundary of Colorado at 32 s longitude west of Washington, D.C s The report has been transcribed aswritten, without corrections.

The rod,or "story pole,"couldtelescope shorter or longerto compensatefor rough terrain.Also shown is atripod,onwhich thetransit wasfixed.

of Congress, approved June 20th 1878; and having on the 26th ofJuly 1878, entered into a contract with the Honorable Commissioner of the U.S.General Land Office, Iproceeded, without unnecessary delay to Ft Garland, Col and Alamosa, Col the latter being the terminous of the Denver and Rio Grande Rail Road.4

At those points I purchased supplies and transportation, employed several additional assistants and finished the outfitting for the proposed survey.

While en route from Washington to Colorado, I had stopped at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and called on Gen. Pope, who informed me that a Military Escort had been ordered toJoin us from Ft. Wingate, New Mexico Territory, but on my arrival at Ft. Garland Col. Gen. Hatch, the Commander ofthe Districtin which the survey lies proposed to furnish an Escort from the Military Camp on the La Plata river, in S.W. Colorado.5 Accordingly, after the change was sanctioned by Gen.

4 The Act of Congress authorized the survey of the Colorado-Utah boundary, not to exceed $15,000 in cost. Ft. Garland is located 26 miles east of present-day Alamosa, Colorado, and was established in the 1850s.The Denver and Rio Grande Railroad got to Alamosa in 1878 See Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg, Rio Grande Mainline of theRockies (San Diego: Howell-North, 1980), p 371

102UtahHistoricalQuarterly

5 General John Pope was commander of the Department of the Missouri Edward Hatch

Colorado- UtahBoundary103

Pope, our escort, consisting of "D"and "K"Companies, 9th Cavalry,6 Joined us (D Company did) about the time we commenced the real survey of the boundary line,while wewere encamped on SanJuan River.

The special instructions, with my copy of the contract and Bond were mailed to me from Washington D.C.on 3rd August '78,and received byme at Animas, Colorado about the 20th ofAugust '78.7

Messrs Tuttle and Gorringe arrived in Fort Garland with me, and we were afterwards joined by Messers Dallas, Toof, Mosely and Sturgus The remaining members of our party were employed from Colorado.8

Having completed our preparations we started on Aug 15 '78 for the South West corner ofColorado The distance isabout 300miles On ourway we stopped two days at Tierra Amarilla, NewMexico, to purchase pack-animals (burros.)9 Also several days atAnimas, Colorado to replenish our supplies, complete the rigging of our pack-saddles, and get ready for the final start to the Initial Monument, still about 100miles distant

After aweek ofhard marching wearrived on the North bank of theSan Juan River, Sept 4, 1878.AtMitchell's Ranch, about 50miles from the beginning corner, we werejoined by Mr. Shirts, an old and experienced mountaineer, who claimed to be familiar with the country and the Indians in this region, and who subsequently, for about twoweeks, acted as our guide and interpreter in dealing with the Navajo and the Ute Indians.10

We arrived about noon on the 4th dayof September 1878.

During the afternoon and the following morning a rude raft was constructed of dry cottonwood logs and on the same day (5th Sept.) Messrs

was only a colonel, but he wasin command of the Ninth Regiment of Cavalry,with headquarters in Santa Fe and companies scattered throughout NewMexico and Colorado In the spring of 1878, companies D, G, I, Kand Mwere encamped on the La Plata Riverjust north of the NewMexico boundary because of Ute Indian troubles in southern Colorado. Specifically, theywere there at the request ofAgent Weaver at the LosPinosAgency TheUtes were being forced to move to newreservations inwestern Colorado from eastern Colorado and northern New Mexico See William H Leckie, The Buffalo Soldiers (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967), pp 205-207 Seealso Monroe Lee Billington, New Mexico's Buffalo Soldiers, 1866-1900 (Niwot: University Press of Colorado, 1991), pp 45-46, 58,117

6 The Ninth Cavalry consisted often companies Officers were white,while enlisted men and noncommissioned officers were black soldiers, including many former slaves and veterans of the CivilWar Companies usually consisted of three officers and 35men Company DwasledbyCapt Francis D Dodge and Company Kby Capt. Charles Parker. The latter took over escort duty on October 19, 1878.See Regimental Returns, Ninth Cavalry, September and October, 1878,RG 94, Records of the Adjutant General's Office, National Archives

7 Animas, Colorado, wasa short-lived mining townjust north ofpresent-day Durango

8 Reeves had hiscrew swear to do an adequatejob asrequired by the General Land Office and as directed by that office J J Sturgus, Leonidas Dallas, C H Gorringe and,joining them later, Henry Potmecky were chainmen. Reeves listed himself as surveyor and astronomer, aswas Capt. H. P. Tuttle. Edwin Toof, along with Dallas, Mosely, Sturgus and Potmecky,joined Reeves at Ft Garland, Colorado Tuttle and Gorringe were already with Reeves Others in the crew were Shannon, Kelly and Scott, who joined later in Colorado

9 Tierra Amarilla isa settlement in northern NewMexico, some 75miles southwest ofAlamosa It is a little out of the direct line of march from Ft Garland to Animas

10 Peter Shirts was a bachelor who in 1877 settled at the mouth of Montezuma Creek where it enters the SanJuan River See David E Miller, Hole in theRock (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1959), pp 25,33 TheHenry L Mitchell extended family settled atthe mouth of McElmo Creek the summer of 1878 SeeRobert S McPherson, TheNorthern Navajo Frontier,1860-1900 (Albuquerque: University of NewMexico Press, 1988), pp. 40-42.

Sturgus, Shannon, Kelley and myself tried to cross the river by getting on the raft and poleing and paddling it across the river, but the current was too strong (estimated to be 7 miles per hour) and we were carried about two miles below our starting place and landed on the same (North) side of the river

Finding it impracticable to ford or raft the river, we next sent two of our party some 50 miles above our Camping place, to bring down a skiff said to be owned by a son-in-law of Mr Shirts, at a settle. / . i-nPeter Shirts merit on the river at that place.

After four days travel the men returned without the boat, stating that the owner wasuseing it so constantly during the present high water, that he could not spare it, though urged strongly to do so by Mr Shirts. He would neither sell, nor hire, nor loan it.

Bythis time the river had fallen several feet, though still too high for us to ford without too great danger. We now built another, similar raft, larger and more easily handled, constructed of 9 dry cottonwood logs, tied together with "Sling and lash" ropes belonging to the pack train. Raft was about 14 feet long by 8 feet wide Mssrs Tuttle, Gorringe, Mosely, Kelley, Shannon, Dallas, Scott, Sturgus and myself crossed on this raft, to an island; then towed the raft around the foot of an island, then all, except Gorringe and Mosely crossed on raft to second island, then towed the raft about 300 yards up stream, and crossed to the South Shore of the river

All bedding, instruments, clothing [line missing from copy] the raft with Tuttle and myself, and the remaining five men clung to the sides of the raft, wading, swimming and pushing it to the opposite shore, which we reached about 500 yards below, the point from which we had embarked.

12

The riverwhere we crossed including two islands,was about 1000 yards wide, current strong (probably 6miles an hour) water muddy and from 3 to 7 feet deep When we first tried to cross, on 5th September, itwas from 10 to 15feet deep in the middle, and the current stronger

In the afternoon Mess. Tuttle, Shannon and Iwalked up Navajo Creek about 4 miles, then separated, and came back to the river along opposite sides of the Mesas bordering Navajo Creek We found no corner. 13

11 This wasprobably Mancos, Colorado The Mitchells had come from southwestern Colorado, and Shirts (sometimes spelled Shurtz) had come from southern Utah, both to farm and trade with the Navajos The Mormon "Hole-in-the-Rock" exploring party found them still there in 1879, firmly entrenched The "skiff" may have been the "home made" canoe Shirts is reported to have had the next year See Miller, Hole in theRock, p 150

12 In the summer the SanJuan River, after a high spring runoff inJune, can flood from rains farther upstream At other times it isalmost dry, and "push boating" on the SanJuan isawell-known aspect of river-rafting there

1S Present-day maps show no Navajo Creek near the Four Corners monument, but they do show "Todastoni Wash"justwest of the monument at the same location as "Navajo Creek." The "corner" Reeves was looking for is the Four Corners monument where the states of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah meet

104UtahHistoricalQuarterly

During the day several Navajo Indians, who had come from their Reservation on the South Side of the river, to trade with the Ute Indians on the North Side the river, forded the river on their horses about two miles above the Camp where we had rafted. IAfterwards crossed and recrossed on my horse several times at the same ford but the main party recrossed to the north side on the same raft on which they had first crossed the day before

The next morning Sept 11th '78,a Navajo Indian, directed byMr Shirts, crossed the river and escorted by Mr Gorringe, proposed to show us the corner for a consideration Abargain was made He took us directly to the true corner, which was East, about Kof a mile of Navajo Creek and away up on a high mesa, [line missing] a fair state of preservation, and was clearly identified by descriptions furnished us from the General Land Office. [Illegible] Capt Tuttle's drawing.

On same night (Septr. 11th 78) Capt. Tuttle and Mr Gorringe made observations for azimuth of Polaris at its eastern elongation, which occurred about 8 P.M

They had a favorable night with very satisfactory results (See Astronomical Report of Captain H.T Tuttle, pages 11and 12bound with this volume) [not included here].

We camped on the river SanJuan about XA mile North of the transit, and they came into Camp about 10P.M.with all hands in good spirits. The result of the observations on Polaris being so satisfactory with a resulting well defined azimuth, itwas decided to prolong the line to the North Side of the San Juan river, and get a new Meridian from the opposite side. This was almost absolutely necessary also on account of our great trouble in communicating with the Camp on the North Side,where were most of our blankets, provisions and (except transit) most valuable instruments

Commenced at the Initial Monument, identified by the discriptions furnished by the U.S. General Land Office.14

Barometer reads 25.33 in. It is a compensated aneroid, manufactured by L. Casella, London, England No. 2195. It was a new instrument and had never been used in the field.

[From page 10 through 349 of Reeves's report he describes mile by mile, in excruciating but necessary detail, the land and each monument he set. These notes are not given here].

GENERAL DESCRIPTION

The instrument used in the execution of this surveywere the same used by Capt. H. P. Tuttle. They are fully described by him in his astronomical

14 The

p 202

Colorado-UtahBoundary105

"initial monument" is the Four Corners sandstone marker set in 1875 by C Robbins Later it was replaced by the present concrete monument See Lola Cazier, Surveys and Surveyors of the Public Domain, 1785-1975 (Washington: U.S Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management 1977),

One hundredfeet long,thechainwasstretchedbetweentheman with thetransitandthe manwith the rod.

report, and as that forms a part of this complete report their repeated description isnot considered necessary.

They consisted of a new transit made byWm Wurdeman, Washington, D.C. I purchased this instrument from Mr.Wurdeman for boundary surveys. The needle of the compass had lost its power, which I did not discover until we had entered upon the survey For this reason our results for variation are not entirely but only approximately reliable In all other respects the instrument was in good condition.

A sextant manufactured by Spencer Browning and Cos., London, England Thiswas the same instrument used byProf Denison in his and my survey of the Washington Ter and Idaho Ter Boundary line

An Aneroid Barometer, manufactured by L. Casella, London, England. This was a new and superior instrument and was loaned to us by the Bureau of Engineers, War Dept Two superior field glasseswere used by the forward and back flagmen, and greatly facilitating their work.

An extra sextant, loaned to us by the Engineer Bureau, was carried constantly with us to use in case our own became impaired

I also carried a new standard steel tape which was used only in testing

106UtahHistoricalQuarterly

Colorado-UtahBoundary107

and regulating the two steel-wired brazen-linked chains which were used in measuring the boundary line.15

A number of steel chisels, hammers, marking irons, axes, hatchets, saws, spades, shovels, picks etc etc all of convenient and appropriate construction, were provided and used as occasion required

The points on the line where the flagmen were stationed, and where the transit subsequently stood, are indicated in the field notes by the abbreviation T.P. meaning Transit Point, or Turning Point. They are frequently, but not invaribly noted. The reason for noting them at all is to define certain points along the line between the mile corners, and to which we could return if necessity required. Theywere usually marked by awooden peg driven into the ground by the front or head flagman, at the precise point where the flag pole was first stuck on the line.16

The flag poles were the same used in the survey of the Dakota-Wyoming boundary line, but were freshly painted.17

Bearings were frequently taken from various points along the line, but it was impossible to take many from the mile corners. Generally no natural objects could be seen, and when seen were often not appropriate objects to use for bearings Stones were used for mile corners when ever they could be found They were considered superior, more durable than wood

The best stone and wood were used which could be obtained from the surrounding country. Where the stones are not of the required dimensions, it isbecause they could not be found and were not to be had.

The monument commemorating the corner common to the Territories of Utah, New Mexico,Arizona, and the State of Colorado, which was the initial point of this survey, and which was established byMr. Chandler Robbins, U.S. Surveyor in 1875, is situated on a flat and lofty mesa about one-half a mile South of the SanJuan River, and about one-quarter of a mile east of Navijo Creek. Starting from this corner the line very soon descends several hundred feet into the Navajo Creek Valley, thence climbs a spur of the bluffs on the south side of the SanJuan River, thence having crossed this spur, descends abruptly to the south edge of said river.

There isa lowbottom bordering the SanJuan River, on the north side, from one-eighth of a mile to one mile wide and continuing, with occasional breaks where the bluffs come abruptly down the waters edge, for many miles up and down the river.

15 Reeves had two different teams of chainmen measuring the distance as a check on accuracy Chains and links are no longer used today, as surveyors are much more accurate with a radar-type instrument

16 When Allen D Wilson returned to resurvey and fill the gaps in Reeves's line in 1885,he did find most of Reeves's monuments, but not all See Allen D Wilson, Field Notes, Of thesurvey remarking and completing a portion of theBoundary Line between the State of Coloradoand the Territory of Utah, RG 49, National Archives

17 Reeves had surveyed the Wyoming-Dakota boundary line in 1877 See C AlbertWhite, A History of theRectangular Survey System (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1982), p 156

Cottonwood trees, willows and aspen are found in this valley in great abundance. The grass on the hills immediately north of this bottom is good, which makes this a good stock range all along the river.

Soil in the valleyissecond rate, but it can be used cultivated by irrigation from the river.18 The timber isof a fair size, though much of it isdead. The valleyon the north side isabout one-quarter of a mile on the boundary line,which latter crosses the river three times on the second mile Near the crossing by the line the valleyhas evidentlybeen used bythe Navajo Indians, in caring for their sheep, Since we saw ruins of numerous corrals, and great quantities of sheep croppings allalong the river in the bottoms.19 These Indians are known to own large and numerous bands of sheep, and we suppose they have used this bottom to protect their stock from bad weather, and to keep their flocks intact, grazing them on the surrounding hills,watering them from the SanJuan, and herding them in the bottom, protected bybluffs and timber and brush

A band of about thirty Ute Indians came down from their northern homes and camped on the San Juan about two (2) miles above where we were encamped. They were well armed and mounted, and had brought ponies with them to trade with the Navajo Indians, who came from their reservation immediately on the south side of the river and who forded the river on horse back, loaded with blankets of their own manufacture, which they traded for the ponies of the Utes.20 No hostile demonstrations were made by either Indians, Soldiers or Civilians and we had no trouble with them during our stay in the vicinity.

After reaching the high bluffs, on the north bank of the SanJuan river, the line traverses a rolling elevated, grass-covered table land, mainly free from brush and timber for about thirty miles, ascending Northward and crossing numerous, rocky ridges hills, valleys and canons, all having for about sixty miles, a general Southwestern slope toward the SanJuan River valley, and into which they nearly all empty21 Their general trend isfrom East and north-East to West and Southwest

The surface is badly broken, the walls and bluffs, rocky and steep, and the timber which we gradually enter about the 25th mile, is mainly Pifion, very tough and stunted, and having its bark full of sandgrit, dulling the axes and making our progress slow and difficult.

In the vicinity of McElmo and Montezuma creeks numerous ruins of ancient buildings, in various stages of preservation, were seen and exam-

18 In this Reeves was prophetic, for Mormon pioneers were trying this method offarming a couple of years later in the Bluff area.

19 Obviously Reeves mean "droppings," a distinct signature of the presence or passing of sheep

20 The SanJuan River had long been, in peaceful times, a meeting place for Utes and Navajos bent on trading When the Elk Mountain Mission tried to settle in the present-day Moab area in 1855, the missionaries, accompanied byUtes, trekked to the SanJuan River to trade with the Navajos. See Ethan Pettit Diary, p 4-6 (manuscript copy in Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley)

21 Reeves iswriting about the so-called "Great Sage Plain" east of present-day Monticello, Utah, and the canyons draining from it into the SanJuan River to the south

108UtahHistoricalQuarterly

Navajos typical of those seenbythe surveyingparty. Therewereno hostileincidentswith either the NavajosorUtes.

ined. Some of these are fully noted and described at their proper places in the foregoing field notes The first fifty miles of this boundary line passes through the North-eastern quarter of the ruins region, which latter extends from this northern boundary away down through Arizona, New Mexico and into Mexico and Central America.22

From about the sixteenth mile station north of the beginning corner, up to and including the one hundred and thirtieth mile, the drainage is into the Dolores River. From thence North the drainage is into the Grand River.23

From about the fiftieth to the ninetieth miles inclusive, the topography is represented on the maps of Dr Haydens surveys as being a broad sage brush plain, free from timber, with rolling surface and generally a fair country over which to prolong the boundary line. We found it to be an almost impassible region, cutup by boss canons, having perpendicular sand stone

22 The prehistoric ruins in this area are SanJuan Anasazi (Pueblo) dating up to the late 1200s. There are both open sites and cliff dwellings here The boundary lines passes, at about mile 28, right next to the Holly Group of ruins, a part of Hovenweep National Monument These are spectacular buildings with towers

23 Reeves must have meant "sixtieth mile" instead of "sixteenth,"for the drainage into the Dolores does not begin along the boundary line until one gets a little north of present-day Monticello, some 60 miles north of the Four Corners The Grand River is,of course, the present-day Colorado River, the name having been changed in 1921 at the request of Coloradoans

Colorado-UtahBoundary109

walls, and one of the most difficult sections to chain or travel over that I have ever seen. 24

There are no settlements by white men, immediately along the line from the initial monument, the the [sic] one hundred and fiftieth mile corner. The only settlement near the line, for the first ninety miles, is about thirty miles east of and opposite to the thirty or thirty-first miles on the survey At that point there are several ranch-men living in cabins on the south side of the Dolores River, at what is Known as the big bend of the Dolores River, or at the mouth of East Canon. There are no women nor children, but about a dozen bachelors who have built cabins and own large bands of cattle and horses. The most prominent among them are the May Brothers. Here too is the last Post Office, until we reach the ninety second mile.25 The only other settlement near the line is on Deer Creek, or what is marked, "Tukuhnikavats Creek" on Dr Hayden's maps. The post office is called La Sal City. The settlement is located about six miles west of the boundary, on Deer Creek opposite the ninety first mile. It consists of some eight or ten families, embracing from thirty to fifty people, among them some very respectable women and well appearing children. There are about a dozen cabins already built and several under construction. The first settlers arrived about twoyears ago, and all have come from the west, not from Colorado or any point east They are an industrious, enterprising and peaceful community There are no Mormons among them, though living in the Pi Ute County, Utah.

Thousands of bushels of vegetables were raised there last summer. Some grain was grown and many tons of native hay was cut from the surrounding prairie It is located at the Eastern base of the Sierra La Sal, is probably seven thousand feet above sea level, has rich soil, fine grass, Pine and Cedar and Pifion timber, and well located for irrigating from the waters of Deer Creek. Mr. Isaac King is the Post Master and keeps the station. They have a weekly mail from the west and one from the East This was the last mail and settlement on our way north. On October 17th ,we mailed our last

24 Hayden's description is based on the account of the Gannett-Gardner parties, members of his survey group who, after being ambushed by Indians at the mouth of Peters Canyon (nine miles north of present-day Monticello) in 1875, crossed the plain from northwest to southeast on the crest of the drainage, avoiding the canyons cutting into the plain from both sides This isthe route of the Old Spanish Trail and the present-day highway Reeves was forced to take the hard route cutting across canyons that mostly run at an angle to die boundary line Hayden's surveys were made to get detailed geographical information on lands of the West open to settlement See F V Hayden, Ninth Annual Report of the U.S. Geologicaland Geographical Survey of the Territories Embracing Colorado and Parts of Adjacent Territories in the year 1875 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1877).

25 The settlement at the "Big Bend" of the Dolores Riverjust downstream from present-day Dolores, Colorado, had by 1878 a post office named after the river, i.e Dolores, in a ranch house See Duane Smith, "Valley of the River of Sorrows," in George D Kendrick, ed., The River of Sorrows (Denver: U.S Government Printing Office, n.d [circa 1982]), pp 10-13 The Mays, R W "Dick" and "Billy," had an isolated ranch near the Utah-Colorado line. In 1881 Dick was killed by Indians, which triggered a battle between whites and Indians ending at Pinhook in the LaSal Mountains See Faun McConkie Tanner, The Far Country: A Regional History of Moab and La Sal Utah (Salt Lake City: Olympus Publishing Co., 1976), pp 117-46

110UtahHistoricalQuarterly

letters there in going north.26 Our next opportunity was at Los Pinos Indian agency, probably 45 miles east of the line, where we mailed letters one month afterwards on November 17th '78

With the exception of the narrow strips of land immediately in the creek bottoms, no good agricultural land of any quantity was discovered along the line. The soil in Deer Creek and Dolores River valleys could be irrigated and be made productive, but the canons of the latter are so deep and the valleys are so narrow that they are almost unavailable to settlers, and are too small tojustify improvement. The whole Grand River valley so far as we saw it, seems almost a desert. There is no good grass and the soil is worthless On the south side of the river, there was nothing but red sandstone cliffs and mesas and canons, bold and picturesque in appearance, but apparently utterly worthless for any useful purposes. On the north side of the river in many places, there isa narrow, bottom covered with cottonwood trees, while about half of the distance along the river up and down the stream, the banks consist of steep, high bluffs, impossible to ascend, and shutting out the view of the river from the wagon-road and trail, which forms the highway between Colorado and Utah, and follows for many miles the north side of the river Most of the timber along the line is Mountain Cedar, Pine, Pifion, Aspen, Cottonwood (in the valleys) Willows and large sage.

The Pifion isgenerally of small size,very rough and knotty and the bark is filled with sand grit, quickly taking off the edge of axes used in clearing and marking the line Two wagon roads were crossed: one on the sixty first mile bearing North west and South East, leading from settlements in Utah to the settlements in Colorado, commencing at Salina, Utah, and extending a south-Easterly direction, around the Southern base of the Sierra La Sal, thence South Easterly into the Mining town of Parrott City, Colorado, via, the Big Bend of the Dolores River, and thence over the Mancos River.27

The road isgenerally in fair condition, but there are several very steep and rocky hills which are so bad that the strongest-built wagons only can

26 The families that settled in the fall of 1877atwhat isnowknown as "Old La Sal"were the Tom Rays, Philander Maxwell, Dr William McCarty and sons, Niels Olson, \he Silveys, and probably others (Faun McConkie Tanner, ibid SeeFrank Silvery, Historyand Settlement ofNorthern Sanfuan County,Utah (Moab:TimesIndependent, 1990), pp 2-3 Old La Sal,which was abandoned in 1930, islocated in Section 34, Township 28South, Range 23Easton the U.S Geological Survey 15minute LaSalQuad., dated 1954 (twelvemiles east of present-day La Sal) The post office was established September 12, 1878,with William Hamilton as postmaster (National Archives to author, May 16, 1958) No Isaac King shows up in any of fhe local histories A mail routewasestablished between Salina,Utah, and Ouray, Colorado, in the spring of 1878 SeeTanner, p 81 Reeves iswrong about the religious preference of the settlers of La Sal, assome of them were Mormons See Norma Palmer Blankenagel, The Salt and theSavor. . . La Sal and Her People (privately printed, 1982), p. 29. Deer Creek runs into LaSalCreek today La SalCreekwasnamed Tukunikavatsbythe Hayden parties,aswas what isnow known asSouth Mountain See Lloyd M Pierson, "LaSalMountains; Ute Names," Canyon Legacy, No. 26 (1966), pp 2-5

27 Parrott City was a short-lived mining town on the La Plata River west of present-day Durango and at the base of the La Plata Mountains See Henry Gannett, The Origin of Certain PlaceNames in the U.S., U.S Geological Survey Bulletin 197 (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1902, Reprint 1978), p. 202. The road generally followed the route of the Old Spanish Trail.

Colorado-UtahBoundary111

Uteencampmentat Los Pinos,1874.

travel them with any safety. My own wagon had both axels broken and was left (abandoned) in trying to carry supplies to us on Grand River. The only other road we encountered waswhat is known as the old Salt Lake wagon road This is in better condition, has been considerably traveled and worked It was first built by U.S Troops, many years ago, and has been much used since.28 This road is the main thoroughfare between Colorado and Utah. It begins at the southern terminous of the Utah Central Rail Road and bears in a general east direction, strikes Grand River, about fifteen miles west of the boundary line, thence follows the North bank of Grand River

112UtahHistoricalQuarterly

28 Colonel W W Loring with 50 wagons and 300 men traversed this route in 1858 traveling from Camp Floyd, Utah, to Fort Union, New Mexico, at the same time building a road that most likely is the one later called the Salt Lake Wagon Road See LeRoy R Hafen, "Colonel Loring's Expedition Across Colorado in 1858," The Colorado Magazine, Vol 23,No 2 (1946), pp 49-75

about sixty (60) miles to a point about forty (40) miles east of the line, thence crosses it and takes its course up Gunnison River for some thirty-five miles, after crossingwhich it continues in the same direction to within twelve miles of the Los Pines Indian Agency,29 where it branches and leads east and south into the SanJuan mines, and then east to the railroads and to Denver, Colorado

From the sixtieth mile on the line to the one hundred and fiftieth mile the whole surface is exceedingly broken and rough: much worse than one can conceive without having seen it The one striking feature is the prevalence of "boss Canons," These are canons cut into the solid sandstone rocks by mountain streams and torrents The walls are generally perpendicular on all sides, making them seem like a huge box These banks and walls frequently extend for many miles in an east and west direction, and, being too steep to descend even on foot, we were frequently compelled to travel several miles to get down into one of these canons, asjust as far again in order to get out The pack animals were obliged to go even further In many instances, we walked from two to four miles to make a half mile in distance & S. [stay?] on the line, while our camp at night would be from five to seven miles away, and we would have to walk it after the days work was done in the evening and before commencing work in the morning.

In one instance, between the thirty seventh and forty-second miles, we were obliged to take the pack train some twenty miles around, east of the line, to cross a canon. 30

Again, about the eighty-seventh mile the surface near the line was utterly impassable and everybody was compelled to travel over forty (40) miles to reach a point one mile north of the quitting point, and on the meridian we were establishing.31

This occasioned a three days delay. In both of these places the men at work on the line could not get to the pack train and it could not be brought to them, so they were compelled to remain out all night without blankets, provisions or water. I did not know then and do not understand how this could be avoided in such a country on such a survey, unless every man iswilling to carry his own blankets and rations. To do this, and work at the same time, most men are unwilling to undertake. I know of no way of avoiding these hardships in locating a boundary line properly through such a country.

From one hundred and nineteenth to the one hundred and thirty first miles, the surface on the line was simply impassable. The entire party includ-

30

31

Colorado- UtahBoundary113

29 Reeves means the Los Pinos Agency

Reeves was crossing the Squaw Canyon drainage west of present-day Cahone, Colorado. He went to the east to staybetween it and Cross Canyon and then headed into the Squaw Canyon drainage.

This must have been the canyon of La Sal Creek at Milepost 92, asit isa precipitous canyon, but a 40-mile detour seems a little extreme Asa contract surveyor Reeveswasprobably selling himself and the difficulties of thejob so as to make up for not monumenting sections of the boundary

ing our Military escort of about thirty men, and all our animals, with their packs, were forced to abandon the line and seek a route to the east of the boundary, in order to cross the Dolores River and get out upon the high, rocky mesa on the north side of the Dolores River.32 Although the distance on the meridian of the boundary was only eleven (11) miles, we probably traveled from fifty to sixty miles, and were tramping five days, in reaching the prominent white rock cliff on the boundary which we had carefully chosen, before quitting the lines, and the identification of which can not fairly be questioned. The field notes show that on this section of the line the distances were determined by astronomical observations for latitude, made on the meridian at the quitting and beginning (resuming) points, and the distance between them computed and reduced to miles and fractions of a mile As there was no fit surface over which to measure a base line, no triangulation could be resorted to. Neither Captain Tuttle nor I knew of any other satisfactory way of prolonging the boundary line and yet keeping the distances even more nearly correct than by chaining I do not consider it feasible to cross the Dolores River from the south to the north side, near the line, and still get up on the line to a point that could surely be identified, nearer (further south) than the natural object chosen by our party It is utterly impossible to cross to the north side of the river on the boundary line, or even get on the line on the north bank of the river with the animals carrying the blankets, provisions, instruments, etc.

No such point is accessible Even though a reckless and adventurous mountaineer should climb to the north wall of the river near the line, he could not be placed in line, because the nearest point to which the transit could be carried on the south side of the river, would be where we placed our final monument, viz at 119 V% miles on the line and which is probably three to four miles from the southern edge of the north wall of the Dolores River.

33

For the first 92 miles no running water was crossed by the boundary line Water was found in tanks or pockets in the rocks in holes in the beds of dry streams, and by digging in low sandy bottoms

The scarcity of water, especially at this season of the year (September and October) caused great inconvenienc in having frequently to locate camp several miles from line Water for cooking purposes, and to be carried in canteens by the party atwork on the line, was transported in Kegs, on the backs

114UtahHistoricalQuarterly

32 Reeves has run into the deep canyons leading off the northeast side of the La Sals and draining into the Dolores River The map of the route taken by Reeves's military escort support groups, drawn by Lt B S Humphrey, Ninth Cavalry, shows them moving along the route of the Old Spanish Trail and setting up temporary supply camps. The cavalry followed the route of the Old Spanish Trail from Colorado through Moab to a point north of Moab, where they headed east on the Salt Lake Wagon Road This avoided most of the rough country the survey was going through but probably made their task of supplying the survey party more difficult See Lloyd M Pierson, "Buffalo Soldiers Come to Spanish Valley," Canyon LegacyNo. 28 (1996/97), pp 2-8

33 Reeves's milepost 119J4 is on South Beaver Mesa overlooking the spectacular canyon of the Dolores River a few miles above where it enters the Colorado River near present-day Dewey, Utah.

Cartoonof aslacker. Whiletherewere some surveyorswhoskimped on theirfieldwork,it is clear that RollinReeves did getupfrom hisdesk tosurveytheColoradoUtahborder.

of pack animals, but the animals themselves had to be watered every day or two. Twenty three miles [mules] and horses were constantly employed by the surveyors, besides about one hundred and fifty that belonged to the government, and were employed by the two companies of cavalry acting as escort

The warm weather and lack of water caused no little suffering to both men and animals while the time employed in hunting water and in traveling to and from camps, located awayoff the line,was nearly, ifnot quite, equal to the time actually spent while immediately at work on the line of survey. 34

From the 92nd mile north, water was more abundant and several mountain streams were crossed. Among the largest streams were, besides the Grande and Dolores Rivers, Deer (or Tukuhnikavats), Roc and Granite Creeks, and Little Dolores River. Roc Creek, Deer Creek and Little Dolores River were the only running mountain streams. Rock Creek was the largest and most beautiful mountain stream crossed by the line. Dolores River flows through a deeply-cut canon of red sand-stone, probably fifteen hundred feet below the general elevation of the surrounding bluffs. It can be reached from only one break in the walls, on the south side near the line. The route is down an old Indian trail referred to in the foregoing field notes. This seemed to be an abandoned road, and I think we were the first white men 34

Colorado-UtahBoundary115

As a contract surveyor dependent on future jobs and paid by the mile, Reeves may be making a case here for a higher rate per mile in rough country

to follow it. There was no evidence of its having been used for several years. Had this almost obliterated ponny trail not been discovered, I think we should have been compelled to go from 30 to 50 miles out of our way to find a pass down into the canon, and get out on the line, on the North side of the river. The last six or seven miles of the line, i.e. from the 144th to the 150th mile, crosses an usually broken surface The breaks of all the South shore of the Grande River are similar to those in the vicinity of the Dolores River. They consist mainly of a series of successive, deep sand stone canons, with intervening rocky ridges and mesas. Their general trend isfrom East to West, and the drainage is into Grande River. I cannot conceive of any useful purpose to which this country may be adapted

The grazing was excellent in most places along the line, but the average altitude being great, water usually scarce, and most of it considerably below the general level, the country bordering the line can hardly be considered a first class grazing region. Stock would usually require feeding during a portion of the winter.35

There were no practical miners nor geologists among our party and consequently, no mines nor minerals were discovered.

Very little opportunity was afforded our party for hunting and fishing since our time was so closely occupied directly with the survey.

Elk and Deer were frequently seen near the line, in various places, most notably between the 90th and the 115th mile. In the vicinity of Deer and Roc Creeks, I saw several bands, numbering from five to ten in each The soldiers killed a few. The Cinnamon Deer [bear?] was the only kind seen and that was on the Dolores River, and a few miles South of Deer Creek. Fish were caught in SanJuan, Grande and Dolores Rivers. There is evidence that Grande and Gunnison Rivers are wide, deep and swift streams during high water. Much trouble and danger isfeared in our prospective return to the 150th mile point, this spring, on account of these rivers.36 There are neither bridges, ferries, nor settlements along these rivers for many miles, East and West of the boundary line.

No hostile Indians were encountered, no dangerous sickness endured nor serious material losses sustained during the prosecution of this survey

During the first month wewere enroute from Washington to the initial point of survey, it rained nearly every day, that being the rainy season in Colorado. Afterwards we were blest with fair weather almost continually. The work of locating the line was begun on September 12, 1878, and we finished the 150th mile monument, where work was suspended in a snow and rain storm, on the afternoon of Sunday, November 10th , 1878. On the night of October 14th , it

35 Reeves's analysis is fairly accurate, but in the next few years after his survey, the country filled with ranches and livestock See Utah Historical Quarterly Vol 32, No 3 (1964) for more information on Utah's cattle industry.

36 To finish the boundary survey and marking north to Wyoming

116UtahHistoricalQuarterly

rained very hard, and the next day, it snowed several hours, falling four or five inches. Much of this snow remained on the ground all winter.

After suspending work, we traveled the old Salt Lake Wagon road up Grande, Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers, crossing each, and entering the Lake City tole-road about one hundred and twenty-five miles from our starting place. Thence to Ft. Garland, via Lake City, Antelope Park, Wagonwheel Gap, Delitorte37 and Alamosa, arriving at Fort Garland November 29, 1878

I trust it may not be out of place for me to express my appreciation of the great services rendered by Capt. H.P. Tuttle, who acted as the Astronomer of this survey. He has been a faithful, industrious and patient worker and assistant from the very inception of this survey to the final suspension of field work on the Grande River. In his subsequent reductions and reports, he has shown the same worthy traits of character.

Capt. Charles Parker of K Co. 9th Cavalry, who has had charge of our military escort, has performed his duty in avery praise worthy manner and I am under great personal obligations to him, and to his command, for many voluntary and gratuitous acts of kindness and assistance, rendered my party and myself.38

I am grateful to for the evident and hearty interest they have taken in protecting us and facilitating the establishment of the boundary line.39

37 A confused rendition of Del Norte, Colorado. Reeves crossed the SanJuan Mountains between Lake City and Alamosa viatwo passes, each around 11,000feet in elevation, in winter, with no complaints. Thejob was done and he was heading home.

38 Capt Parker with part of Company Kapparently waswith the surveyors to fend off Indians while Lt Humphrey with the rest of the company kept the supply lines open

39 In his seminal History of theRectangular Survey System (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1982), p. 172, C.Albert White states that the boundary lines of Colorado follow straight lines of longitude and latitude However, the boundary with Utah has a deviation bearing two miles to the west starting at about the 81s1 milepost and continuing northwest, coming back on a more northerly line at about milepost 89 One source {The DenverPost, March 16, 1958) saysReeves had cloudy nights and could not see Polaris, the north star, during that time, but his notes indicate he may have had a problem in triangulation going across a canyon Reeves came back and finished the line to the northwest corner of Colorado the next year In 1885 Wilson reran the boundary and found tbe deviation, but, according to law, once the line wasset it could not be changed, and sowe have the "bent"boundary between Colorado and Utah See Franklin Van Zandt, Boundaries of the United States and the Several States, U.S Geological Service Professional Paper 909 (Washington, D.C: Government Printing Office, 1976).

Colorado-UtahBoundary117

Dr. Elizabeth Tracy: Angel of Mercy in the Pahvant Valley

BY EDWARD LEO LYMAN

BY EDWARD LEO LYMAN

WHIL E THE LEGENDARY Mormon women physicians Ellis Shipp, Romania Pratt Penrose, and Martha Hughes Cannon were in the twilight of their careers, another Utah doctor—this time a gentile—was earning a similar, though more geographically limited, reputation In 1910, Dr Elizabeth Cahoon Tracy—at around the age of forty—began her first marriage and second medical career amidst the drab greasewood-covered lands of the so-called North Tract area of west Millard County.1 In a place where transportation was still poor and the population was considerably larger than itwould be in later years, the min-

A native of Delta, Dr. Lyman teaches history at Victor Valley College, California, and continues a rigorous writing schedule

The author acknowledges the earlier contributions of local historian LaVellJohnson, on whose work he has heavily drawn

1 Locals consider the area surrounding Delta, Woodrow, and Sutherland to be "west Millard County"; in reality, the area ismiles from the county's western border

Photo courtesy of Great Basin Museum, Delta, Utah.

Dr. Elizabeth Tracy: Angel of Mercy 119

istrations of this kindly doctor easily made Elizabeth Tracy legendary in her own right.

By 1910 the area where Dr. Tracy would live and practice had attracted a number of settlers still hoping to establish prosperous farms in the early twentieth century. The land was being developed, largely by non-Mormons, under the Carey Act;2 these developers had agreed to assist the Mormon-dominated irrigation companies in impounding winter runoff at an enlarged Sevier Bridge Dam in southeasternJuab County, making a great deal more water available downstream in Millard County Largely because of the supposed abundance of irrigation water available for these vast Pahvant Valley lands, the promoters became successful in recruiting settlers from throughout the American Midwest, California, and places in between.

The centerpiece of the new agricultural development scheme was the uncleared but fertile fields soon named Sutherland, which became some of the most productive land in Utah. Several milesfarther north, another community, named Woodrow after the recently elected president of the United States, also sprang into existence. Unfortunately, most of the soil there did not prove quite as productive as that in Sutherland. YetWoodrow settlers, and those on even worse land farther out in an area mainly called Sugarville, worked just as hard as their neighbors in grubbing greasewood stumps, plowing land, and digging irrigation ditches—and they held equally high aspirations for eventual prosperity.

Of future importance to Dr Elizabeth Cahoon, a man named Jerome Tracy was one of the first to become established at Woodrow. Tracy, a former NewYork statejustice of the peace, "was educated for the [Roman Catholic] clergy, but renounced his training and wandered where he pleased," according to longtime Delta newspaperman Frank A Beckwith Most recently, Tracy had been prospecting and mining throughout the Southwest, particularly in Arizona When he left employment in a mine nicknamed the "widowmaker" because of its many silicosis victims, he came into contact with promoters of the Oasis Land and Water Company project in west Millard County, and he committed to developing a farm on two forty-acre tracts near a crossroads location soon to become Woodrow

Tracy's first winter on the raw land was relatively mild, and he was comfortable in the canvas-topped sheep camp he placed on the site.

2 The CareyAct, passed in 1894, provided for the reclamation of arid lands byconveying up to one million acres to states that were willing to promote irrigation projects

2 The CareyAct, passed in 1894, provided for the reclamation of arid lands byconveying up to one million acres to states that were willing to promote irrigation projects

The next year he had a framedlumber granary built in preparation for the good barley or wheat crop he expected. All the fields needed was one good irrigation, but that never occurred, because the Burtner-Delta dam broke that year. All the farmers on the project lost their crops from lack of water. The dam washout essentially bankrupted the Oasis Company, and although many families abandoned the area and others voiced major discouragement, Tracy and a few other hardy pioneers remained optimistic over the region's prospects as a great agricultural center. They proved to be correct. West Millard became the country's premier alfalfa seed-raising region and is still the leading alfalfa hay producer in all of Utah and perhaps the entire Intermountain West.

There is no reason to believe that Jerome Tracy, described as a "short, bristly Irishman," held any grudge over the dam washout, the irrigation company's most serious crisis. However, later records from his justice of the peace court for Woodrow precinct indicate that he was consistently impatient with the successor irrigation company when it allowed water delivery canals to overflow, creating difficult mud hazards along the roads of the community that he, more than anyone else, was charged to oversee and protect. More than once he levied fines on the Delta Canal Company for offenses that others might have been more likely to overlook.3 The judge was notorious as "a most colorful character," and he was "keen on issues as he saw them."4

Tracy had already met Dr Elizabeth Cahoon through the mediation—some alleged that it was connivance—of a mutual friend. While most people considered Tracy abrupt and somewhat opinionated, he was apparently also a good-looking, interesting middle-aged man. At one time, Elizabeth inquired if he ever swore, although she had

120 Utah Historical Quarterly

Judge Jerome Tracy. Photo courtesy of author.

3 Woodrow PrecinctJustice Court Records, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

4 Millard County Chronicle, July 31, 1947, in which Elizabeth's close friendJosie Walker told the "Life Story of Dr E.R.C Tracy."

undoubtedly heard of his fluency in that aspect of communication. His reply that he never did "in the presence of ladies"was apparently adequate.Jerome sent Dr. Cahoon an issue of the local newspaper promoting west Millard County,5 and while she had probably already committed to becoming his wife, she read it, liked what she saw, and agreed to come to Utah to marryJerome and live with him on his farm. Referring to the fact that he had wooed and won the hand of the impressive doctor in marriage, Utah friends universally agreed that thejudge's "oratorical ability many times exceeded his ability as a farmer "6

Dr. Cahoon metJerome at Salt Lake City, where they were married on September 10, 1910. Two weeks later, they arrived at the boxcar depot of Akin, soon to be Delta, where they walked a short distance to a tent serving as the first public eating place in the infant town and had a good breakfast The proprietor informed them that the postmaster was anxious for the bride to retrieve the mail forwarded to her, because all the wedding gifts sent from the East were too much for his cramped log cabin quarters. After a ten-mile drive in

6

Dr. Elizabeth Tracy: Angel ofMercy 121

Jerome Tracy and Elizabeth Cahoon Tracy before their marriage. Photo courtesy of Great Basin Museum.

5 One of those who refused to be discouraged by dams going out for two successive years was former mining camp newspaper editor Norman Dresser, whose initial issue of the Millard County Chronicle featured an article on the area's potential. Elizabeth Tracy later served as Dresser's local correspondent in exchange for a free subscription

LaVellJohnson, ed., "Elizabeth R Cahoon Tracy, M.D.," MS., Great Basin Museum, pp 10-15

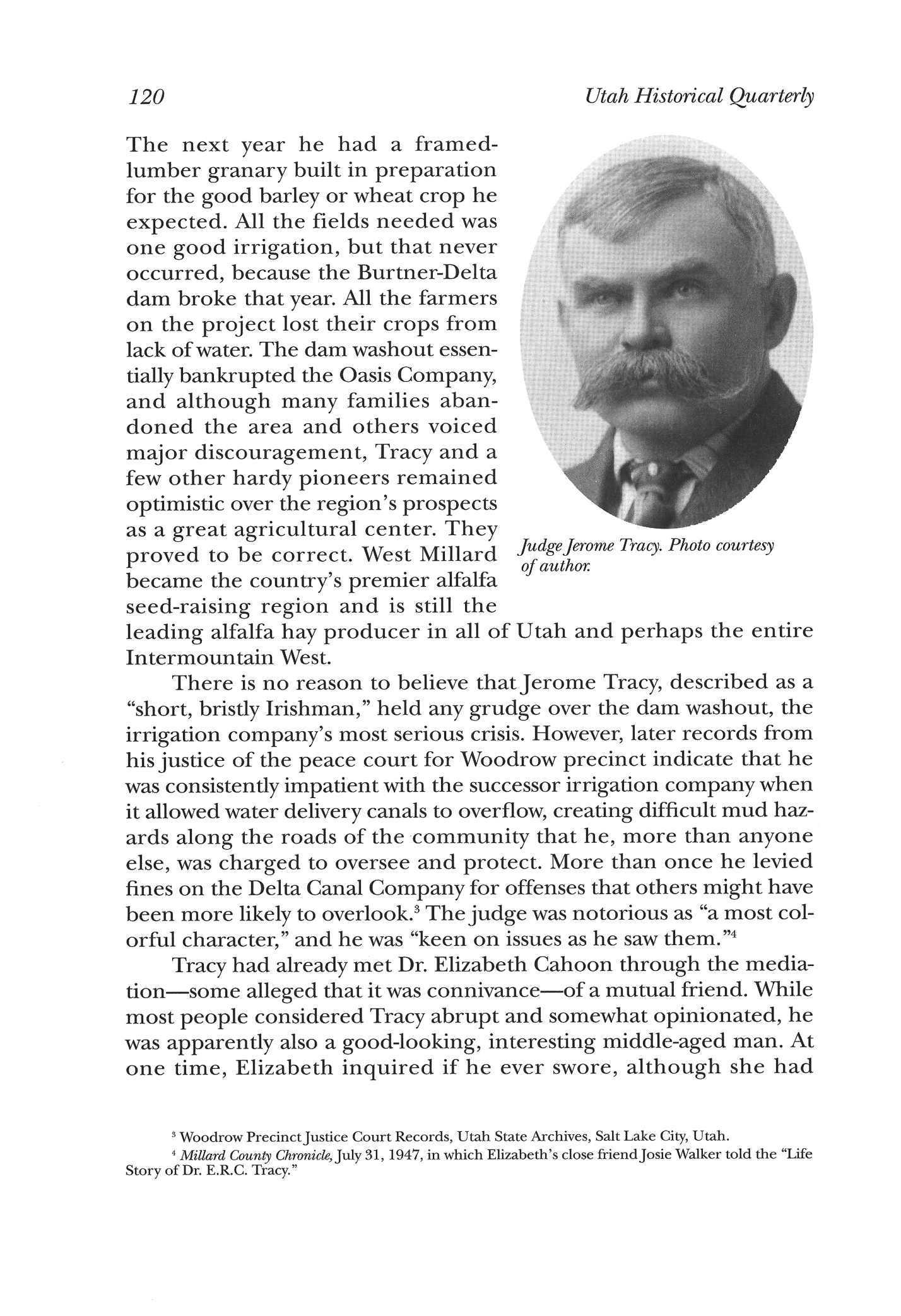

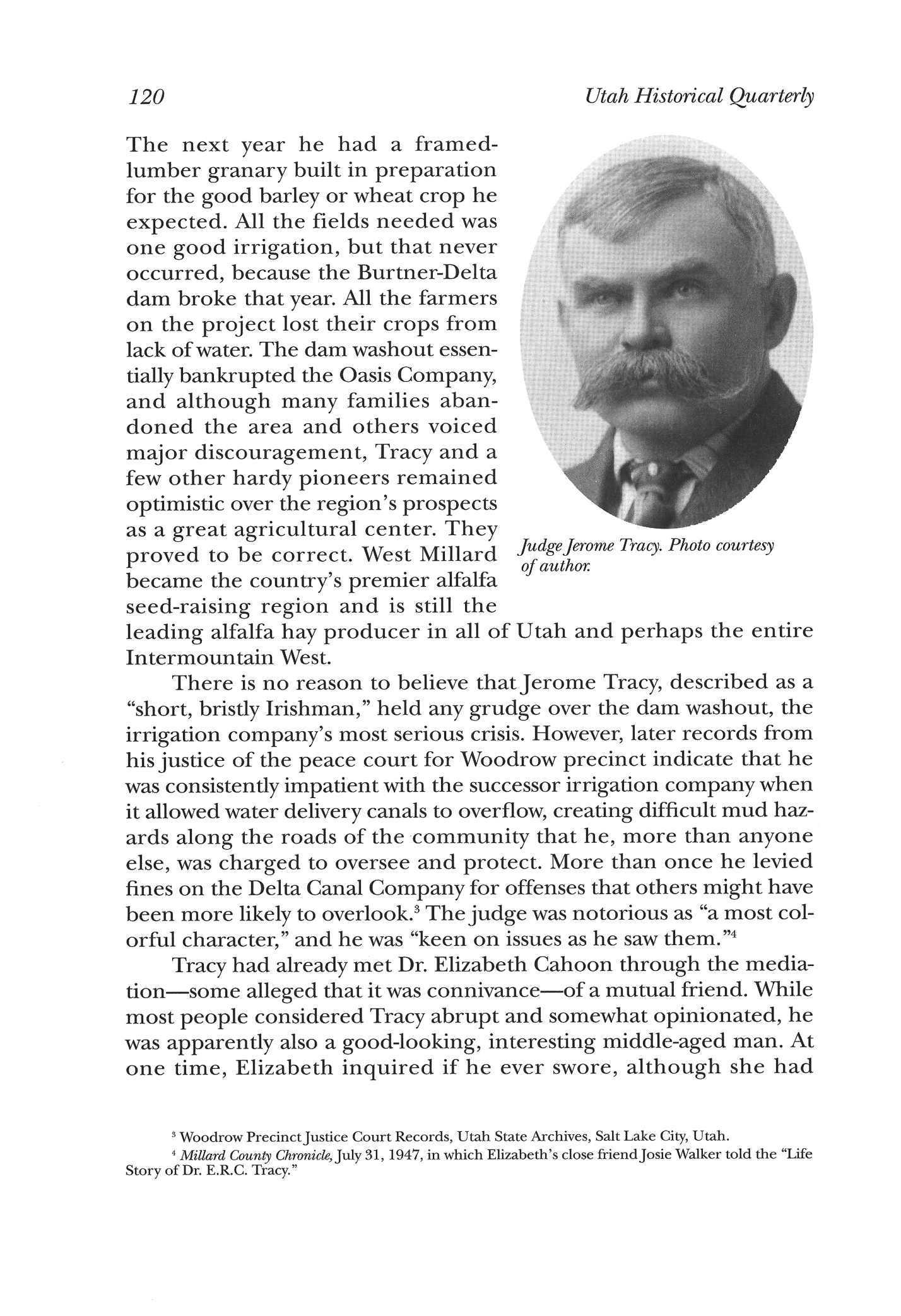

a white-topped buggy, Elizabeth first saw the fourteen-by-ten windowless granary that, aswas typical for the area, would be her home until better quarters could be moved to their property within the year. Jerome was known to quip at the time, "It's not so hot, but it's all we got.'"

The couple was soon marooned for the winter in their desert location, at that time two and a half miles from their nearest neighbor. But the bridegroom had sowell provided for winter supplies that on occasion local stores came to him for replenishment when freight was not delivered with sufficient promptness at Akin Besides, as Elizabeth later recalled, she and her husband had a good library and the time to enjoy it Judge Tracy, according to Frank Beckwith, was a "voluminous reader and the best posted man in seventeen states . . . original, full of mirth,just oozing reminiscences," and as such would have been particularly good company. Jerome also loved classical music and had many good records that would have helped occupy the time; no doubt theywere played on a spring-propelled Victrola, since it would be more than a dozen years before electric power would be available in the vicinity.

722 Utah Historical Quarterly

The Tracy home in Woodrow. Also visible is a sidebar mower, perhaps the one Elizabeth sat on as she contemplated her life. .FromWest Millard County, Utah, a booklet produced by the Delta Commercial Club, undated. Courtesy of author.

7 LaVellJohnson, "APiece of God's Green Earth for Me," typescript MS., Great Basin Museum, Delta, Utah, pp 1-6

One day not long after the first winter, the relatively new bride was sitting on the spring seat of a mowing machine facing the inevitable Pahvant Valley wind with her back to the house, perhaps becoming accustomed to the scenery so different from her earlier life. Her husband came up behind, slipped his hands over her eyes and quietly inquired of her thoughts Assuring him of no worries or anxiety for the future, she replied rather romantically that she was cruising through her present life with him with "a sense of freedom and exultation." Elizabeth later recalled that even in subsequent years they "lived and worked and dreamed together" with a "mutual sense of freedom from care and responsibility."8 Other aspects of her life indicate that she actually did feel an acute sense of responsibility for others, but it iscertain that those yearswere indeed a happy and satisfying part of an eventful life.

In one notable incident, thejudge publicly displayed his affection for his wife. Many dances were held at Woodrow Hall, soon erected across the road from their home Elizabeth usually attended, but because of a lame leg she never danced. At one of these dances Jerome suddenly came across the floor, leaned down, kissed her, and stated for all to hear, "God, Betsy, I love you." One of her closest friends concluded that certainly Elizabeth "had experienced the richness in life from this relationship."9

As a local correspondent to the Millard Progress, perhaps Elizabeth Tracy described Woodrow to the readers in the fall of 1915. Woodrow was not a town or anything similar but was simply an agricultural district which centered on a crossroads intersection. The Tracys happened to reside on one corner; the others were occupied by a district school, a country store, and eventually the Woodrow recreation hall Yet the crossroads was the vital center of a community with as much unity and spirit as any closely situated urban neighborhood.10

This community had a higher concentration of non-Mormons than any other area in Millard County. The 1920 census indicated that the population of 431 was divided almost equally between Latter-day Saints and so-called gentiles But since more than half of the LDS residents were children, the preponderance of non-Mormon adults in the area was quite large. The situation was similar aswell in the com-

9 Millard County Chronicle, July 4, 1935; ibid.,July 31, 1947

10 Millard County Progress, October 22, 1915.

Dr. Elizabeth Tracy: Angel of Mercy 123

8 Dr Elizabeth Tracy, "Impressions of a Tenderfoot," Millard County Chronicle, July 4, 1935 LaVell Johnson, penciled notes of interview withJohn DeLappJr., Great Basin Museum; Millard County Chronicle, July 2, 1981

munities being established farther north and west, particularly in Sugarville.

Born at Dover, Delaware, to strictly religious parents, Elizabeth had obtained a good education, including eventually an M. D. degree, an achievement that was still unusual for a woman. Tracy's early medical practice was at children's hospitals in New York City, with some time at Bellevue Hospital. While there is every indication that she intended to retire from practice when she married and moved to Utah, there were simply too many people in need of her impressively effective services for her to deny them. She was to serve selflessly in the less-than-prosperous North Tract area of west Millard County for a full twenty years.

Perhaps another reason Elizabeth changed her plans and reentered the medical profession was her disappointment at not becoming a mother herself. The quilt-covered child's trundle bed that neighbors saw, placed carefully under the big bed of the granaryhouse, was eloquent testimony of the lady's hopes. It probably took less than a year for Elizabeth and Jerome to realize that, for them, the time of child-bearing had passed. Local historian LaVell Johnson aptly conjectured, "That empty trundle bed explains why Elizabeth Tracy worked so hard to save every baby she could which was born to a mother in the [land-irrigation] project." A close friend in the Millard County years, Cornelia Turner, noted the care the doctor took to tie her new infant's hair with a pink ribbon. Elizabeth "loved to wash and play with babies," she stated. This observation is further corroborated

124 Utah Historical Quarterly

fi n i i.

Woodrow Hall, the community center located across the street from the Tracy home. USHS collections.

Dr. Elizabeth Tracy: Angel of Mercy

by the doctor's own statement that "each new babywasabeautiful and precious thing beloved by all."11

One of the emergencies that essentially forced Elizabeth Tracy back into medical practice was her diagnosis that a neighbor boy, Taggy Hersleff, had a ruptured appendix. She knew he would die if not rushed to Salt Lake City for surgery, so the Tracys took him to Delta, and the doctor accompanied him by train to the cityfor the successful operation. Another crisis, apparently early in her North Tract residence, occurred when a young neighbor boy—probably Ed Miller—severely burned his hand. Elizabeth sat him in her rocking chair, carefully cleaned the hand, and applied some type of salve to each bit of burned skin. Then she bandaged the throbbing hand one finger at a time, instructing that the bandage should not be removed for about three weeks. When examined after the requisite time, the skin showed no scar tissue, and even after fifty years the former patient could demonstrate full use of his hand

LaVellJohnson concluded that Elizabeth Tracy "could no more shut her eyes to her neighbors' plight than she could shut her heart." The otherwise doctorless Woodrow-Sutherland-Sugarville region had too many babies to deliver, fractured bones to set, and other medical needs to attend to, and the conscientious doctor could not ignore such demands. Over the years, under primitive conditions with oftenimprovised materials and equipment, Dr. Tracy's success at practicing the healing artswas phenomenal.

12

At first, those requesting the doctor's care brought their own conveyances to take her to patients, but Dr. Tracy soon secured agood driving team and buckboard and learned to drive them over the rough roads at good speeds Night and cold did not deter the fur coat-clad doctor on her errands of mercy When the roads were too muddy, she was even known to travel byhorseback Many of the dwellings to which she was called were shacks, tents, and camp wagons, where she performed her work with skill equal to that which she had demonstrated in the best of conditions in NewYork City.John DeLapp recalled that his mother had once assisted Dr. Tracy by holding a girl on a dining room table while the doctor sutured wounds inflicted bya horse bite.13

It isuncertain whether Elizabeth Tracy had ever engaged in gen-

11 Johnson, "God's Green Earth," pp 2-6; Millard County Chronicle, July 4, 1935;ibid.,July 31,1947

12

13

125

LaVellJohnson, pencil notes, Great Basin Museum; Ruth Clark Done, letter to Great Basin Museum, February 23, 1993,drawing on information from her aunt who had once spent awinter boarding with the Tracys

LaVellJohnson interview withJohn DeLapp, copy in Great Basin Museum

eral practice prior to her arrival in Utah, but her experience in a major metropolitan children's hospital certainly helped her master one of the most challenging and appreciated areas of a physician's calling, pediatrics. She was believed to be "unsurpassed in the diagnosis of children's disease."Whether or not she had previous experience, the doctor also became an expert at delivering babies and caring for the mothers, in some instances bringing every child in a family into the world

And more than a few adults owed their lives to her skill and medical knowledge. Illustrative of her success is a brief entry in a local newspaper stating, "Mrs. Herman Holdredge was critically ill last week, but with Dr. Tracy in attendance, is getting along nicely." One of the most appreciated aspects of Elizabeth's practice was her bedside manner, for she always talked out the case and relieved as much anxiety as possible. As patient and friend Josie Walker reminisced, "her patients were stimulated by her conventions. Her humor was rich and juicy. One often forgot to groan and laughed instead."14

One of the notable contrasts between Elizabeth Tracy and most other contemporary (male) doctors was the use to which she put her skill with a sewing needle. Not only was she famed as a seamstress, making gift clothes for neighbor and namesake children, but when she was waiting for an expectant mother's delivery, she frequently occupied the time stitching baby clothes for the new arrival. Her husband divulged that she did not buy white outing flannel by the bolt but in multiple bolts for that purpose. Her sewing skill undoubtedly helped her improvise surgical bandages and perhaps other useful appurtenances of the profession, since she did not have access to the ready-made items available to her during her New York years. 15

The Tracys were particularly unoccupied with financial concerns Even with those patients who were fully able to pay substantial fees the doctor charged but twenty-five dollars for a child's delivery, including subsequent check-up visits—less than half of what a doctor in northern Utah would charge. As early observer Frank Heise recalled, "Money was scarce and many times she knew she would never receive a dime for her services, but she never refused to answer a call, regardless of weather conditions or time of day or night."16 Her calls were

14 Millard Progress, March 5, 1914; Millard County Chronicle,July 31, 1947

126 Utah Historical Quarterly

15 LaVellJohnson, ed., "Jerome and Elizabeth Tracy Helped Found Woodrow," MS., Utah State Historical Society; Millard County Chronicle, July 31, 1947

16 "Biography of Frank Heise," holograph, 1967, Great Basin Museum.

frequently offered free to those in distress who were reluctant to request assistance. Often her payment was in kind: a bag of alfalfa seed, a load of hay, ahome-cured ham, a quarter of beef, chickens, or eggs. These items found their way into the kitchens of needy people farther along her route as often as they reached the Tracy household. A vivid example of Elizabeth's characteristic generosity and love of her neighbors was the first-hand experience of theJenkins family, who lived at the same crossroads as the Tracysfor over a decade. Lynn and WandaJenkins recalled that the doctor was their mother's closest friend and that she gave the family many gifts. On one occasion Mrs. Tracy made beautiful embroidered silk dresses for each of the four Jenkins daughters. One of the doctor's prized possessions was a specially made gold-tinted carnival glass dish given by friends as a wedding present Young Wanda, who often helped with the Tracy housework at the larger house soon moved across the canal from the original, demonstrated such fascination with the dish that Elizabeth presented it to the mother to give the girl later asawedding present— and it is treasured to the present time. Similarly, when Mrs.Tracy was preparing to leave Woodrow after her husband's death, she urged Bob Jenkins to do her a favor by taking the big Dodge touring car off her hands, the only approach that would have persuaded him to accept the offer. The family enjoyed the automobile for years thereafter. The most lasting impression of the two neighbor girlswho had the opportunity to observe her over much of her West Millard career was that

Dr. Elizabeth

ofMercy 127

Tracy: Angel

"North Tract Gentile Pioneers, " according to notes made by LaVellJohnson. USHS collection.

Elizabeth Tracy "was kind in every way—areal humanitarian." Not coincidentally, thatwas precisely the term the widow of a former doctor colleague, Ivie Smith, used in reference to Elizabeth.17

Dr Tracy played an essential role in helping another family residing not The treasured dish that, like so many far awaymake it through the extended things, Dr. Tracy gave away. crisis of losing a relatively young husband and father. With some frequency, the doctor would drop byto persuade the mother, Henrietta Barben, that her daughters could handle the family's housework while Henrietta accompanied the doctor on house calls,where she sometimesstayed to assistafter Tracymoved on to take care of other cases Mrs. Barben did sufficiently well that in subsequent years Dr. Tracy's successors continued employing her in similar ways.In some cases, when the family paid their doctor bill the entire account went to the widow-assistant, no matter how much she protested that it was more than her share In addition, the eldest Barben daughter did washing and ironing for the Tracys,asshe did for others in the neighborhood. The Tracyspaid her adollar for each session, andwhen she protested that others paid her less, thejudge called them "skinflints," insisting on continuing the higher fee.

Henrietta Barben recalled that after thejudge died and Dr.Tracy began severing her ties toWoodrow, itwasa "hard blow"to many she had helped and encouraged for so long The sprightly Henrietta, in her mid-90s at the time of her reminiscences, concluded, "I don't think many of us would have made it through all the hardships if it had not been for the encouragement and help of Jerome and Elizabeth Tracy."18

One of the strongest demonstrations ofrespect isnaming a child after aperson. Itisimpossible at thisjuncture to count the number of maleTracysand female Bettyswhowere named for the doctor,but the number wasunusually large and included Tracy Fullmer and Tracy Shields, Elizabeth (Betty) Shipley Swenson, and Elizabeth (Betty) DeLapp Baker. Childless herself, Dr. Tracy always remembered her

128 Utah Historical Quarterly

17 Interview with Lynn J Wilson and WandaJ Parish, Victorville, California, June 22, 1993; Ivie Smith (widow ofDr Bernard H Smith) toM E Bird, April 12, 1974, inBird file, Great Basin Museum 18 LaVellJohnson, ed., "Henrietta Barben Autobiography," MS., Utah State Historical Society

little namesakes with gifts on their birthdays. She gave the Shields boy a corduroy suit she probably made herself and thereafter sent an annual check A decade after she moved from the area, she sent a rather large check from Florida, confessing that in her declining years she would probably be unable to continue the practice.19

Elizabeth's family had been devoutly religious, with her father serving at least part of his time as a clergyman. In the Delta area, the doctor was an active member of Reverend Charles H. Hamilton's Presbyterian church, the first Protestant congregation there. But the judge, a former student for the Catholic priesthood, never had much appreciation for the sermon delivery methods of the reverend, whose habit it was to pace the floor and wave his arms as he preached. Jerome drove Elizabeth to church services each Sunday then stayed in the car and read the newspaper until she was ready to leave. Elizabeth was also a teacher in the community Sunday school at Woodrow, and her Mormon friend, Josie Walker, described her as a "deep student and teacher of the Bible."