UTA H HISTORICA L QUARTERL Y (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIA L STAF F

MAXJ EVANS, Editor

STANFORDJ.LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTENSMARTROGERS, Associate Editor ALLANKENTPOWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISOR Y BOAR D O F EDITOR S

NOELA CARMACK,Hyrum, 2003

LEEANNKREUTZER,Torrey, 2003

ROBERTS.MCPHERSON,Blanding, 2001

MIRIAMB.MURPHY,Murray, 2003

ANTONETTE CHAMBERSNOBLE,Cora,WY, 2002

RICHARD C ROBERTS,Ogden, 2001

JANETBURTONSEEGMILLER,Cedar City, 2002

GARYTOPPING,Salt Lake City, 2002

RICHARD SVANWAGONER,Lehi, 2001

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah history The Quarterly is published four times ayearbythe Utah State Historical Society,300 Rio Grande,Salt Lake City,Utah 84101.Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership andpublications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $20; institution, $20;student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or older),$15;contributing,$25;sustaining,$35;patron,$50;business,$100.

Manuscripts submitted for publication should be double-spaced with endnotes Authors are encouraged to include a PC diskette with the submission. For additional information on requirements, contact the managing editor Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society

Periodicals postage ispaid at Salt Lake City, Utah

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City,Utah 84101

98 IN THIS ISSUE

100 Thomas L. Kane and Utah's Quest for Self-Government, 1846-51

By Ronald W.Walker

120 Wanda Robertson: A Teacher for Topaz

By Marian RoberstonWilson

139 North Logan: A Town without a Plan ByJessie

Embry

152 "You Haven't Got Enough Guts to Shoot — Hand Me That Gun!" Sheriff Antone B. Prince, 1936-1954

By Stephen Prince

172 BOO K REVIEWS

MarlinStum,photographsbyDanMiller. Visions ofAntelope Island and Great Salt Lake.

Reviewed by David Stanley

VirginiaMcConnell Simmons. The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico.

Reviewed by Kathryn L MacKay

TomDunlay Kit Carson and the Indians.

Reviewed by Clifford P Coppersmith

DavidE Stuart Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place.

Reviewed by Winston Hurst

BradDimock Sunk without a Sound: The Tragic Colorado River Honeymoon of Glen and Bessie Hyde.

Reviewed by James M. Aton

KennethWilliamTownsend World War II and the American Indian.

Reviewed by Jim Vlasich

Robert S.McPherson,ed. The Journey of Navajo Oshley: An Autobiography and Life History.

Reviewed by Gary Tom

BOO K NOTICES

SPRING 2001 • VOLUME 69 • NUMBER 2

' COPYRIGHT 2001 UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

184

Very often, the course of events creates a situation that calls for someone to step forward and do something, for good or for ill. In 1846 the well-born Thomas L. Kane set out with "dazzling hopes" to forge a notable public career. But those ambitions ebbed when he visited the Mormon refugees from Illinois at their camp near Council Bluffs.Ashe grew to know the Saintspersonally and ashe saw their suffering, he later said, his "higher humanity" overrode his desires for fame. By nature and upbringing Kane had already become interested in -workingin behalf ofunderdogs,and here he found acause that ignited him From this point, he would spend much of his energy and political currency in helping the Saints as he spoke, wrote, lobbied, strategized, and maneuvered in their behalf. His work in helping the Mormons gain political ascendancy in the UtahTerritory isthe focus ofthe first article

I N THI S ISSU E

98

A century later, Wanda Robertson made up her mind to serve an oppressed group. As a gifted educator training new teachers at the University of Utah's Stewart School, Robertson received an invitation to supervise the elementary schools at the Topaz internment camp near Delta. The dean of the College of Education frowned on her "going out to help those people" ofJapanese descent, and her family also criticized her decision.Nevertheless, she readily left her comfortable university career.She saw the internees not as "enemy aliens" but as refugees unjustly driven from their homes, and she wanted to use her training and experience to help the incarcerated children. Our second article tells that story.

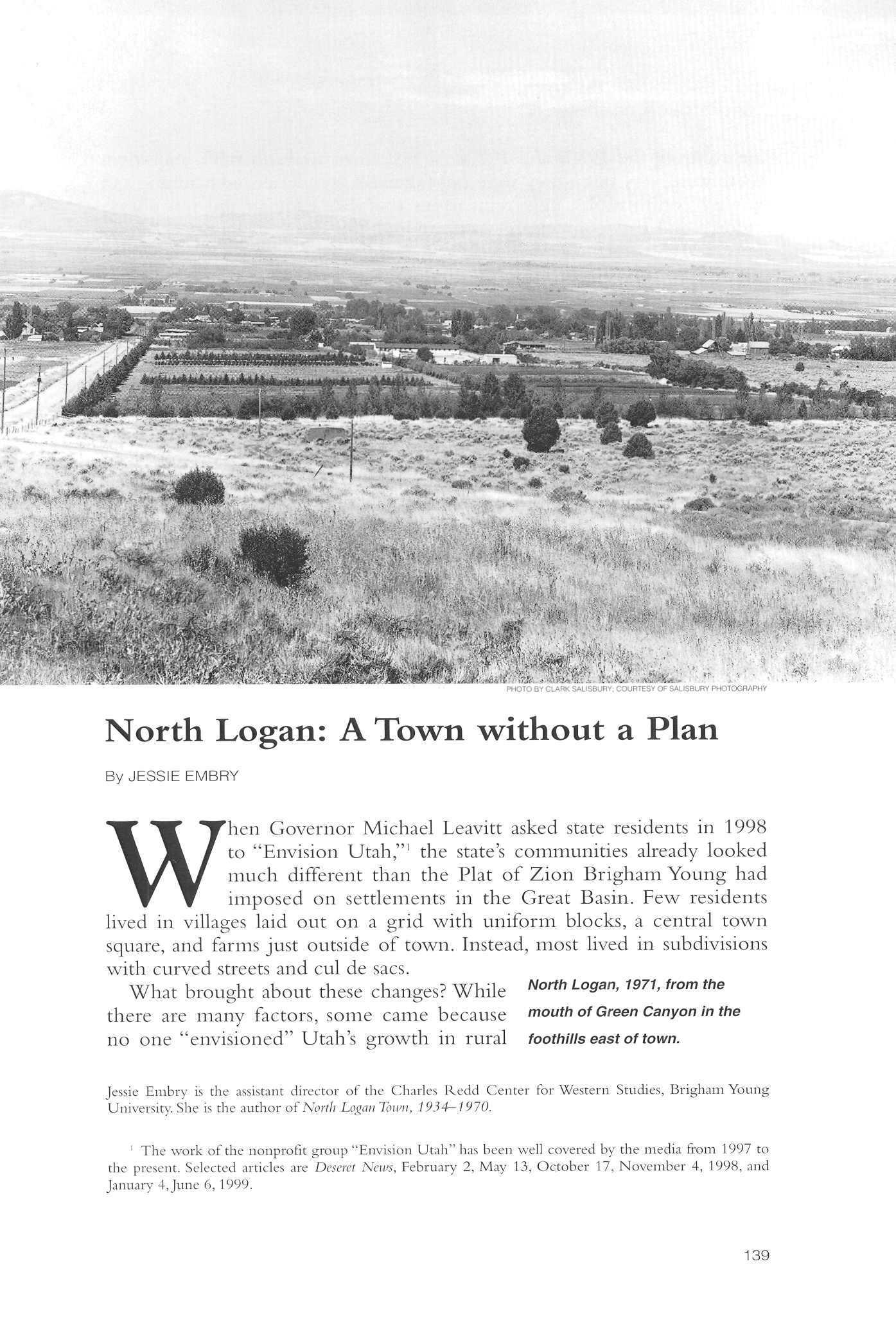

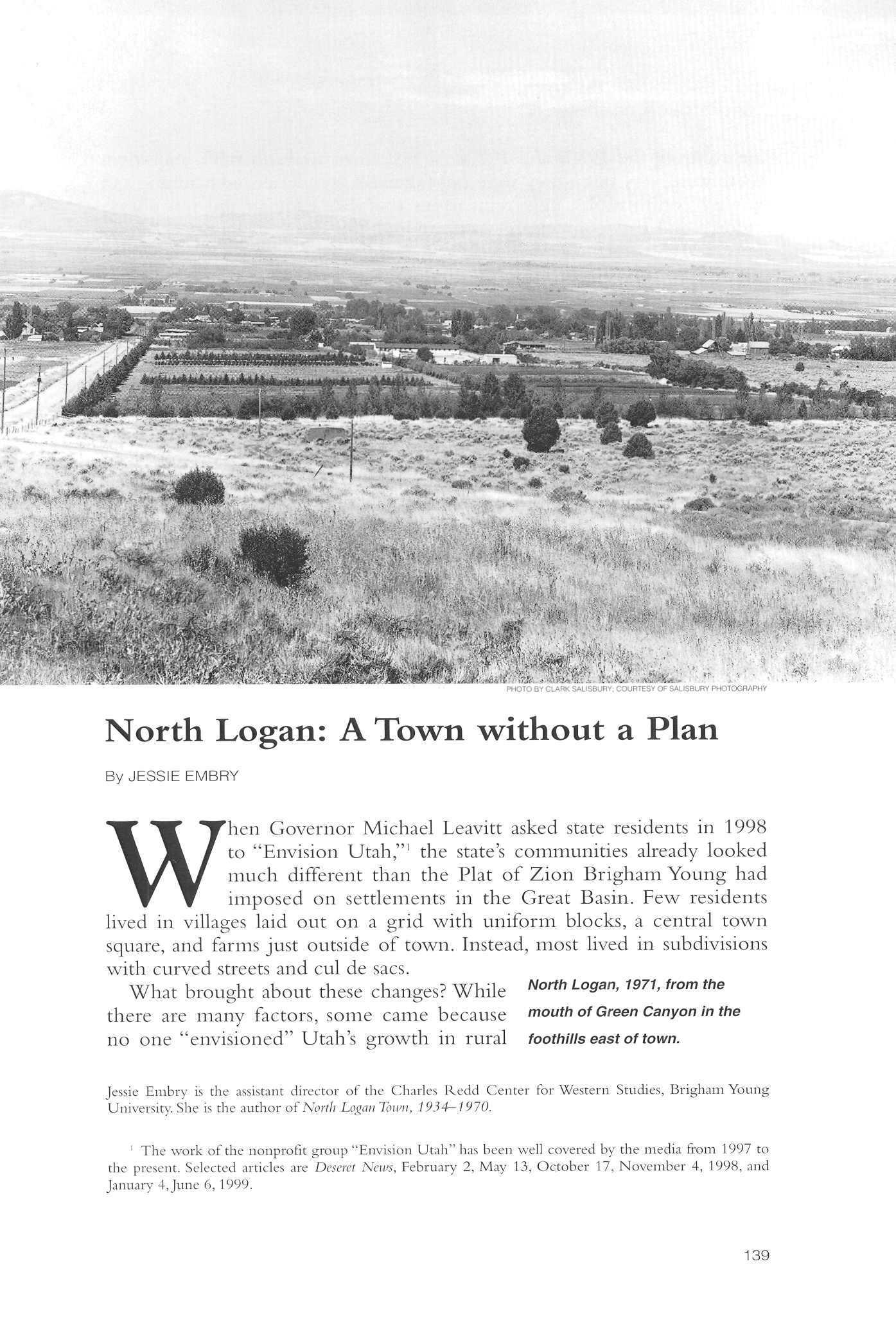

The third article in this issue deals not with an individual but with a community of individuals—citizens, leaders, developers—working to negotiate the future of North Logan As growth pressured the town, volunteer planners and elected officials tried to make good decisions But since they had little experience, they had to feel their way along Often, they created ordinances, zoning maps,and master plans only after mistakes had made the need for better planning tools painfully obvious Also, their goals of good planning and good neighborliness collided at times Thus the town changed gradually, subdivision by subdivision In examining North Logan, the article eloquently portrays pressures and pitfalls that have been experienced by many Utah towns

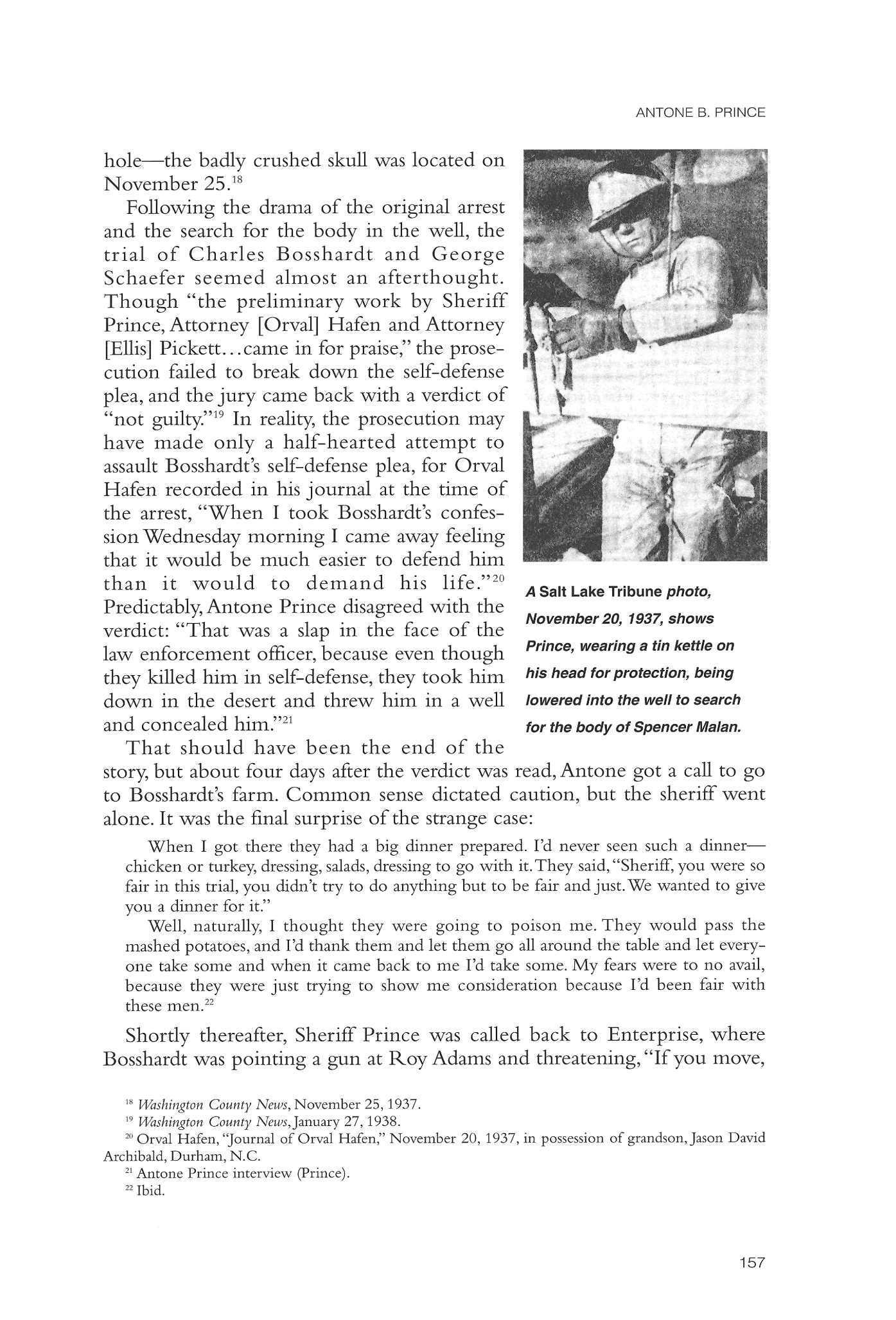

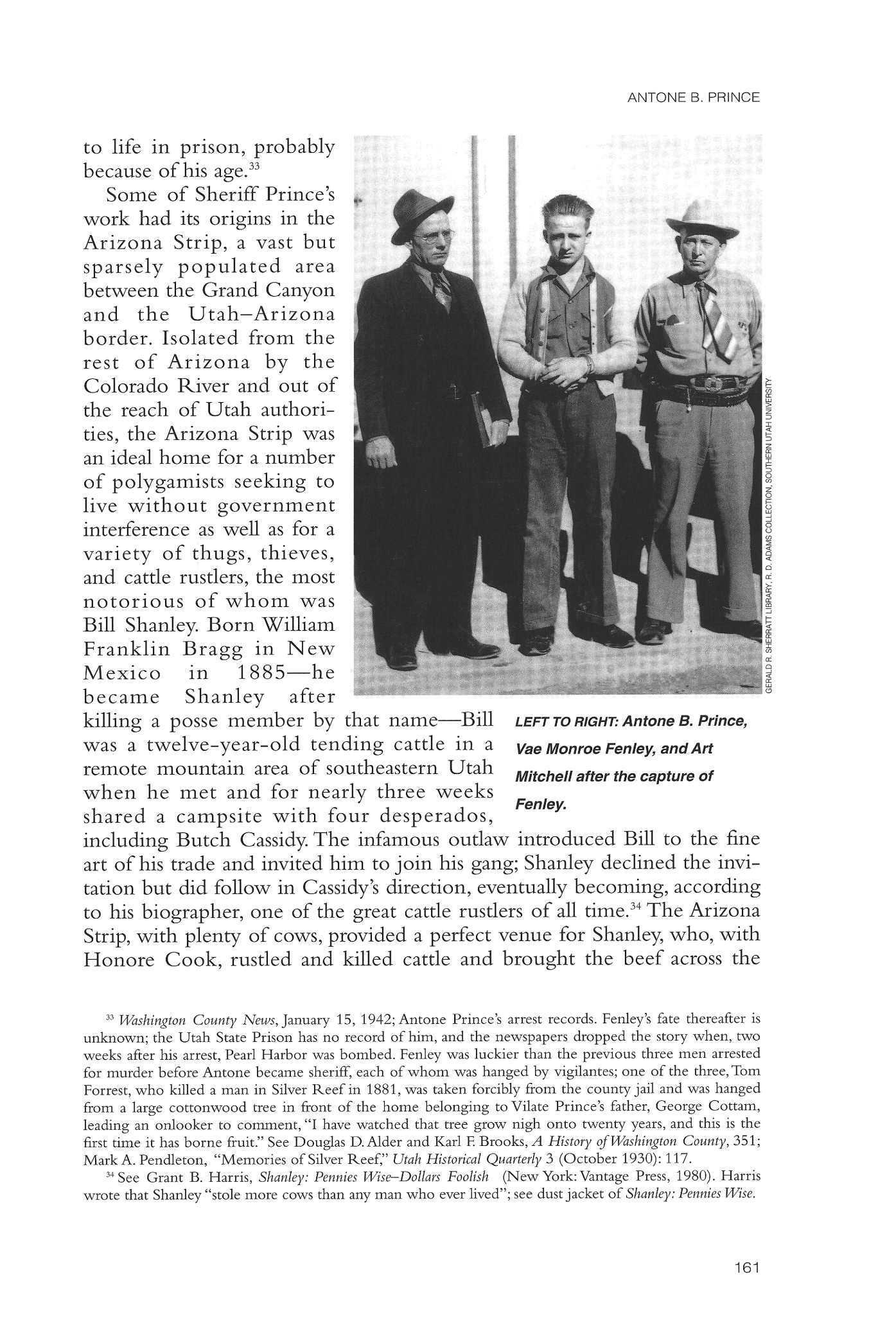

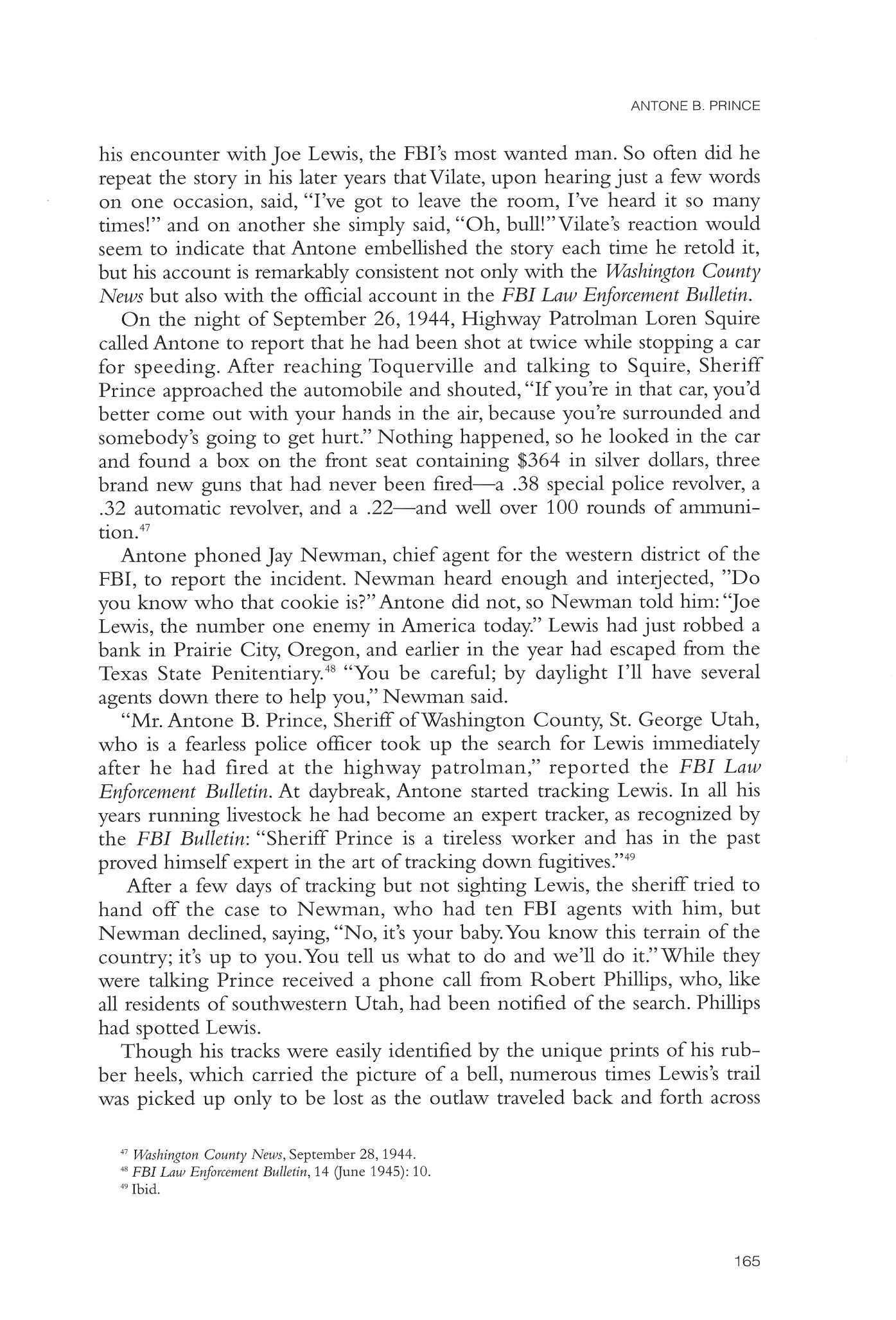

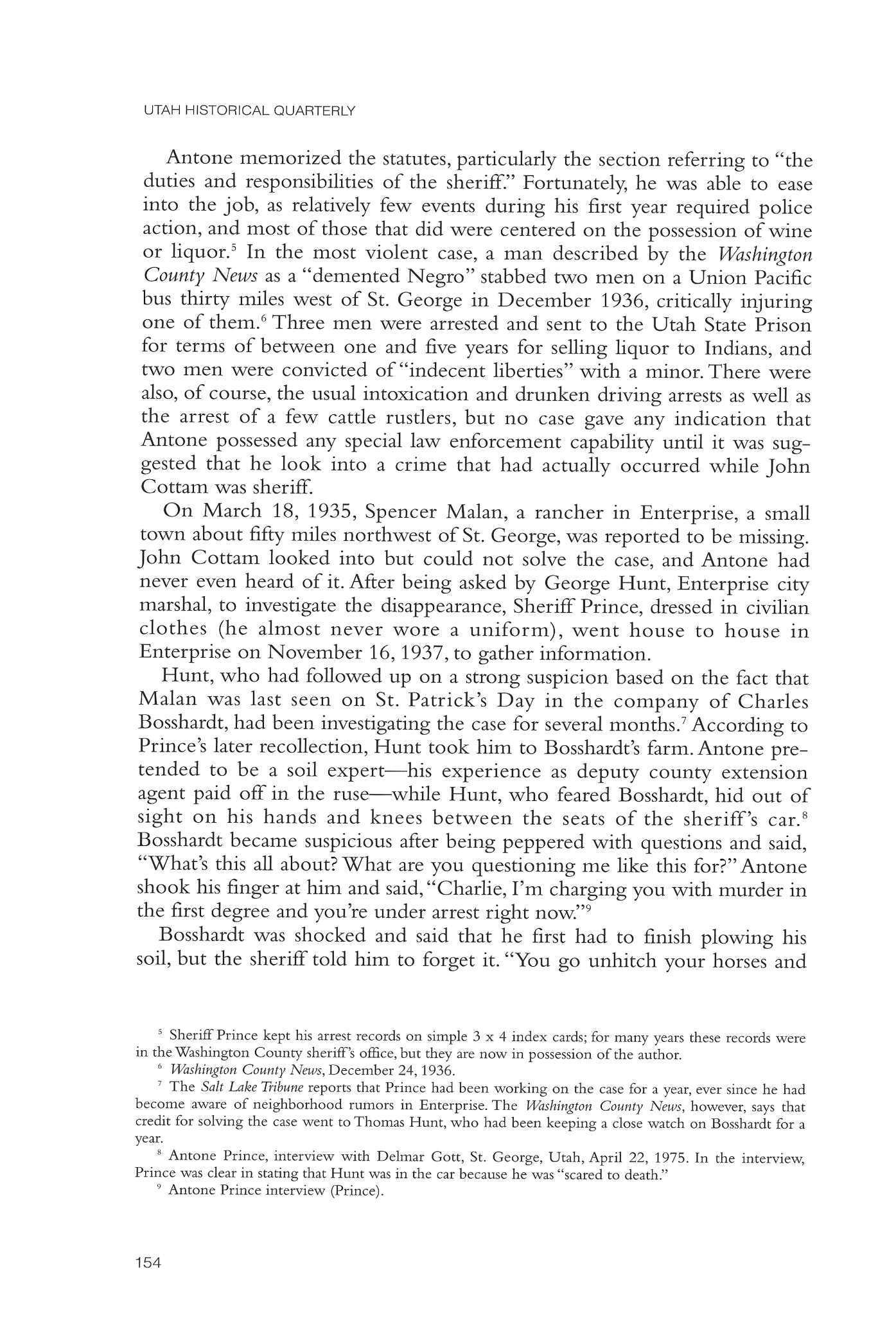

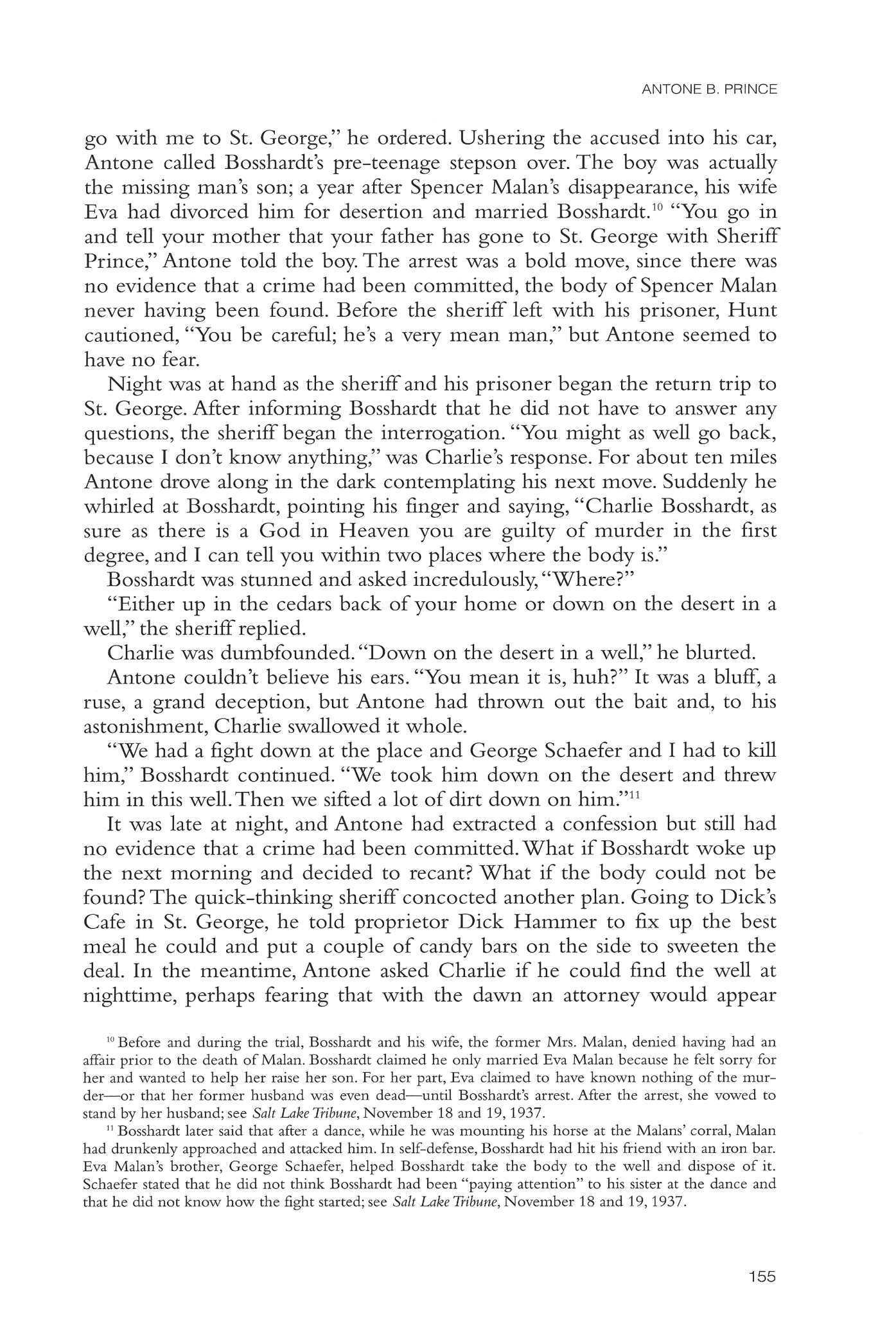

Yet another article,the last in this issue,tells the story of aperson "called" to step into alarger arena of service Summoned to theWashington County courthouse in 1936, assistant county extension agent Antone Prince got a shock when the commissioners told him,"Congratulations....We appointed you sheriff today."Unaware of how competent he would actually be at the job, Prince accepted hesitantly Resourceful, fearless, and somewhat naive, this untrained sheriff solved his cases in unusual ways His career covered more than arrests, though Like Kane and Robertson, he was kind to a despised minority:the criminals whom he arrested Not that he circumventedjustice (except in a"crime"involving Dixie College football), but he did treat his prisoners with unusual respect, and he often trusted them in ways that are inconceivable today

The community members of North Logan responded to needs created by the changing times. Likewise, the three individuals described in our other articles responded to circumstances that called for their particular talents. Fortunately, those who stepped forward to address the situations explored in this issue ofthe Quarterly were people ofintegrity and good intentions.

OPPOSITE: Students at Topaz pledging allegiance to the flag. ON THE COVER: A high school student studying in his family's barracks at the Topaz Japanese American internment camp. USHS photo

99

Thomas L. Kane and Utah's Quest for SelfGovernment, 1846-51

By RONALD W WALKER

By RONALD W WALKER

On the day the U.S government declared war on Mexico, May 13, 1846, diminutive, twenty-four-year-old Thomas Leiper Kane (1822—83) attended a meeting of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in his native Philadelphia With the Mexican War beginning and the Mormon trek west in progress, Kane apparently saw an opportunity for both idealism and ambition: Perhaps he could aid the Mormons and at the same time start a military or political career in California, the rumored stopping place of the Saints.Might he gain a commission in the U.S Army or eventually sit in the U.S Congress as California's (and the Mormons') delegate? His Mormon—California adventure might even provide the basis for writing a book.1

Of course,youthful and highly ambitious goals seldom go asplanned. In Kane's case,his contact with the Mormons led to a different outcome. For the rest of his life—more than thirty-five years—Kane became the Saints' most helpful nineteenth-century ally While scholars have already detailed some of Kane's Mormon-related activity, especially his role in helping to settle the "Utah War" of 1857-58, his early work with the Mormons requires further

Thomas L. Kane

(1822-1883)

1 For Kane's literary and political ambitions, see Thomas L Kane to Elisha Kent Kane, May 17, 1846, Kane Papers, American Philosophical Society, cited in Mark Metzler Sawin, "A Sentinel for the Saints: Thomas Leiper Kane and the Mormon Migration," Nauvoo Journal 10 (Spring 1998): 20

Ronald W Walker is professor of history and director of research at the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for LDS History, BrighamYoung University

100

examination.2 Between 1846 and 1851,Kane and LDS leaders built close ties that help to explain several important events in early Mormon and Utah history,most notably Utah's quest for territorial self-government.This quest reached a climax with the appointment of Mormon leader Brigham Young as Utah's first governor It is a colorful and important story, well worth the telling

Kane was a scion of a distinguished family ("I have been born with the gold spoon in my mouth, to station and influence and responsibility," he would say).3 His father, John Kintzing Kane,judge of the U.S. District Court for eastern Pennsylvania and a Democratic party insider, had connections withJames K Polk'sWhite House AlthoughThomas Kane was in poor health when he first met the Mormons (illness plagued him from his youth), during the next several weeks he established aworking relationship with eastern Mormon leaders,and he used his father's connections to visit leading Washington insiders, including Democratic party chieftain Amos Kendall, U.S Secretary of State James Buchanan, U.S Secretary of War William L.Marcy,and Polk himself.These talks,which often included LDS eastern representativeJesse C.Little,led to the approval of aMormon battalion for Mexican War service.4 For the Mormons, the battalion was a godsend While allowing them to show their patriotism to a doubting U.S public, the battalion also provided much-needed money for their western trek—soldiers'salariesbecame achurch resource.

The Mormon battalion may have offered more than met the eye. Kane later revealed that during hisWashington talks he had become party to a secret and never-disclosed Polk administration plan that apparently aimed to involve the Mormons in wresting California from the Mexicans "You never...have understood this," Kane later wrote Mormon leaders in an enigmatic passage that he never explained.At the time ofKane's letter, with Polk dead and other principals to the plan expunging details from their papers, Kane promised to put in his personal papers a detailed memorandum explaining the episode Unfortunately, the memo has never come to light.5 Kane's reports have this much credence:Polk and his administration

2 Sources on Kane include Albert L Zobell,Jr., Sentinel in the East:A Biography ofThomas L. Kane (Salt Lake City: Utah Printing Company, 1965); Leonard J. Arrington,'"In Honorable Remembrance': Thomas L. Kane's Services to the Mormons," Brigham Young University Studies 21 (Fall 1981): 389-402; Richard D. Poll, "Thomas L Kane and the Utah War," Utah Historical Quarterly 61 (Spring 1993): 112-35; and the already cited Sawin, "A Sentinel for the Saints,"17-27, which is useful in describing Kane's earliest contacts with the Mormons

3 Thomas L Kane to Brigham Young, September 24, 1850, typescript, "Correspondence between Thomas L Kane and Brigham Young and Other Church Authorities, 1846-1878," LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City. Unless otherwise cited, the documents in the following footnotes are drawn from this important source.

4 Jesse C Little Journal, July 6, 1846, cited in Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latterday Saints, LDS Church Archives (hereafter Journal History)

5 Kane to "My Dear Friends" (Brigham Young, et al.), July 11, 1850 Kane thought that "No living man survives informed upon the topic, unless [Nicholas P.] Trist[,] the Mexican Treaty Negotiator," who was also formerly chief clerk for the U.S State Department Kane either failed to write the memo or thought better of the idea and destroyed it. David J. Whittaker, director of the L. Tom Perry Special

L KANE

THOMAS

101

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

were conspiracy-prone,weaving intrigue within intrigue.

Whatever the plan, in early summer 1846Kane left Washington for California, bearing official government dispatches and a letter of recommendation from Polk The latter's closely worded phrases seemed "written with the goal of hinting at (butconcealing) a special Kane mission. Polk wrote ofKane having his"confidence" andbearing"information ofimportance."Polk's letter also instructed U.S officials to render Kane "alltheaid and facilities in accomplishing theobject ofyourjourney."6 Nothing more than these allusive passages appeared, although part ofKane's mission had to dowith putting theMormons under close watch.7 Atthetime, Mormon intent was unclear andtheir presence intheWest disquieting.

Arriving atFort Leavenworth inJuly,Kane found that hewastoolate to join the regular California migration, already on the plains. Disappointed by the"abasement" ofhis"dazzling hopes ofwhich I only have the secret," he returned the government dispatches toWashington by mail He then traveled totheMormon camps,which were stalled near theMissouri River near present-day Council Bluffs, Iowa, to fulfill the"main object ofmy journey." 8 For the first time, he would have the opportunity to meet Mormon leaders firsthand.

What he saw deeply affected him.Witnessing the Saints' distress and sensing their basic decency, Kane found himself re-examining thevanity of his ambition Helater explained:

I believe that there is a crisis in the life of every man, when he is called upon to decide seriously and permanently if he will die unto sin and live unto righteousness, and that, till he has gone through this, he cannot fit himself for the inheritance of his higher humanity, and become truly pure and truly strong, 'to do the work of God persevering unto the end'.... I believe that Providence brings about these crises for all of us, by events in our lives which are the evangelists to us of preparation and admonition. Such an event, I believe too, was my visit to you. 9

Kane's change from politician—adventurer tohumanitarian maynothave been as dramatic as he later made it.While a young student studying in France, he hadshown enough revolutionary fervor to have theParis constabulary arrest him;at this youthful stage ofhis life he hadbeen studying the writings ofsuch radical reformers asAuguste Comte, Francois Fourier, and Claude Saint-Simon, and he apparently was attending meetings that aimed at social andpolitical reform Another sign of Kane's idealism sur-

Collections at Brigham Young University and curator of the recently acquired but still unavailable Kane papers at BYU, suggests that no such memorandum exists in the collection

6 James K Polk to Kane,June 11, 1846

7 Thomas L Kane to John K and Jane Leiper Kane,July 3, 1846, Kane Papers,American Philosophical Society, cited in Sawin, "Sentinel for the Saints," 21, and Thomas L Kane to George Bancroft, July 11, 1846, Bancroft Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, in Donald Q Cannon, ed., "Thomas L Kane Meets the Mormons," BrighamYoung University Studies 18 (Fall 1977): 127-28

8 Thomas L Kane to John K and Jane Leiper Kane, July 3, 1846, and Thomas L Kane to George BancroftJuly 11,1846

9 Kane to "My Dear Friends,"July 11, 1850

102

faced when he met the Mormons in 1846;he carried with him letters of recommendation written by Roman Catholic prelates The Kane family made noblesse oblige a matter of routine, even to the point of extending friendship and perhaps service to the unpopular Roman Catholics of the time.10

Two weeks after arriving in the Mormon camps,Kane began to act on behalf of the Saints He wrote a letter to President Polk endorsing the Mormon plan to establish a temporary "Winter Quarters" on Potawatomi land in Iowa.11 The matter was of critical importance to the Mormons, whose migration had stalled on the plains of Iowa and were therefore in need of a way station for their westward journey. In part due to Kane's helpful letter and to the later lobbying of government officers by Kane and his father, the Mormons were allowed to stay on Omaha and Oto land on the west side ofthe Missouri River.12

Then, two months after he first met the Mormons and started his western adventure,Kane's fragile 5'6", 130-pound frame gave way.At the time, his disease was called "nervous bilious fever," perhaps one of those fevers common to the Midwest lowlands or perhaps what one historian has identified as pulmonary tuberculosis.13 Whatever the nature of his sickness, he was severely ill, and for a time those around him despaired of his life. At Kane's request, the Mormons sent an express rider to Fort Leavenworth to get the best medical help available.14 Until the arrival of a doctor, the Mormons themselves nursed their young, elite visitor He had his hair shaved, requested the purgative Dover's Power, and asked to be bathed in order to break his fever, a request that may have led to rumors of his LDS baptism.15

Nursing was not the only bond that drew Kane to the Mormons. He found that he liked the Mormon leaders, including John Smith, uncle of the church's founding prophet At Kane's request, Smith pronounced upon him a "patriarchal blessing." Mormons believed that a patriarchal blessing could foretell the future, and in Kane's case the promises were striking. Despite his poor health, he was promised life and protection ("No power on earth shall stay thy hand"), a distinguished posterity, and even a fullness of LDS priesthood power, despite his not being a Latter-day Saint. Kane put enough credence in the blessing to speak fondly of it in later years and

10 Letters of Francis Patrick Kenrick, Bishop of Philadelphia, and Daniel J Desmond, Consul General of His Holiness Gregory XVI, dated June 9 and 11,1846.

11 Kane to Polkjuly 20, 1846Journal History.

12 For the Kanes' later lobbying, see Journal History, September 4 and 12, 1846

13 Arrington, "'In Honorable Remembrance,' 391 Kane himself called his fever "the congestive." See Thomas L Kane, The Mormons, as excerpted in William Mulder and A Russell Mortensen, eds., Among the Mormons: HistoricAccountsby Contemporary Observers (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1958), 208

14 Brigham Young to Stephen W Kearny or "Whoever May Be in Command," August 10, 1846 For a printed extract of this letter, see Oscar Osborn Winther, ed., The PrivatePapers and Diary ofThomas Leiper Kane:A Friend of the Mormons (San Francisco: Gelber-Lilienthal, Inc., 1937), 21

'Journal History, August 11, 12, and 14, 1846

THOMAS L KANE

103

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

to inquire whether it remained in force.16

Kane found no Mormon leader more fascinating than Brigham Young, and the two began a friendship that lasted untilYoung's death thirty years later. It was a friendship based on more than Kane's warm appraisal of Young's leadership ("an eccentric great man," he calledYoung17) Despite the great differences in their backgrounds,Kane andYoung found that they were congenial spirits. Both enjoyed planning and carrying out great schemes.Both were visionaries who saw themselves asworkers in behalf of the downtrodden. Both felt they had a stubborn independence from society's traditions and corruptions Finally,both Kane andYoung liked to share their ideas with each other, usually by letter or by courier."I have also to thank you for your kind hearted letters,"Kane once wrote,"though short, always so fresh and racy and spirited in composition."18 Hardly a major national event passed without acomment between them, and even some of Young's later policies in Utah seemed to have had an antecedent in their letter-writing.

The day after receiving Smith's blessing,Kane was well enough to return East. He had been with the Mormons for less than two months, but these days were important for both parties, as his later reflections made clear."I am getting to believe more and more every day asmy strength returns that I am spared by God for the labour of doing you justice," he wrote to his new friends.19 For Kane, the Mormons seemed to intensify what was already stirring within him:a sympathy for the unpopular and unfortunate, a need for aprincipled life ofservice,the hope for a cause to set him apart Perhaps some of these impulses had an element of sibling rivalry His dashing brother Elisha was already well on his way to becoming a famous author andArctic adventurer. In 1850 Elisha would serve assenior medical officer in the celebrated Grinnell expedition to rescue SirJohn Franklin; three yearslater he led asecond expedition

As for Mormon religious claims,Kane was guarded A dozen years after Kane first met the Mormons,Young gingerly invited Kane to undertake a close study of Mormonism. Kane replied in such a way as to have Young acknowledge their frank differences and close the discussion.20 Kane, raised a Presbyterian, apparently was not attracted to denominationalism or even to formal Christianity. Ifthese opinions brought distress to his family, espe-

16 For Kane's request for the blessing and its circumstances, see Wilford Woodruff Diary, September 7, 1846, Wilford Woodruff Papers, LDS Church Archives, and Patriarchal Blessing, September 7, 1846, LDS Church Archives Kane later wrote that the blessing "has not failed so far, though there have been times plenty when I could not have insured on it at 99V2per cent.;—but I am curious to know, does...[Smith] say it is still to hold?" For this inquiry, see Kane to Young, Heber C Kimball, and Willard Richards, February 19, 1851

"Kane to James Buchanan, undated rough draft, 1858

18 Kane toYoung, September 24, 1850

19 Kane toYoung, September 22, 1846.

20 Young to Kane, May 8, 1858, andYoung to Kane, January 14, 1859, Brigham Young Letterbooks, BrighamYoung Papers, LDS Church Archives

104

cially to his future wife, Elizabeth, who hoped for his conversion,21 they probably gave him the emotional distance and tolerance to view Mormonism for "what it was:a new but misunderstood movement of great religious and social promise Whatever its rough edges, these would be smoothed with time

Kane already had been helpful in getting a Mormon battalion authorized during the Mexican War. He had also induced his father to use his influence to gain permission for the Mormons to use Indian land for their Winter Quarters en route west. However, these acts only began his Mormon mission. Upon returning to Washington and submitting a proMormon report, Kane found Polk disturbingly uncertain about his policy toward the Saints.Instead oflistening to Kane,the president seemed to turn to such advisors asarch-Mormon foeThomas Hart Benton, Missouri's senator, who reportedly talked about sending a "dragoonade" to force the Mormons from Winter Quarters. Perhaps hoping to rid himself of Kane's entreaties, Polk tried to persuade Kane to "go abroad upon other public service,"perhaps to serve as anAmerican diplomat. However, Kane refused to be managed. In a private interview with the president he accused Polk of "deceit," and when the Democratic party nominee, Lewis Cass, sought election in 1848,Kane worked to defeat him.Politicians like Polk and Cass led Kane to accept adark view.Political office, he believed,usually reflected "the arbitrary trammels of party" and a likely suppressed conscience in favor ofpolitical expediency22

Facing political uncertainty, Kane embarked on a public relations campaign designed to shape a pro-Mormon government policy. He wanted to "manufacture" public opinion. First, he wrote and placed in the national press supposedly "impartial letters" about Mormon activity.These Kaneauthored letters,published in various newspapers in the United States, had such authentic-sounding addresses as Nauvoo, Galena, St. Louis, Ft. Leavenworth, and other western communities.23

Kane described these first letters as artillery "long shots" of limited impact. Next he fired at "close quarters."This second volley consisted of clearly pro-Mormon articles for leading national journals.24 By December

21 When Kane returned from Utah after negotiating a settlement to the "Utah War" in 1858, Elizabeth was encouraged by her husband's well-marked Bible. However, Thomas later informed her that "the hope that had dawned on him of being a Christian was gone." See Elizabeth Kane Diary, May 21, 1858, as cited in Richard D Poll, "Thomas L Kane and the Utah War," Utah Historical Quarterly 61 (Spring 1993): 133

22 These details are contained in a lengthy letter, Kane to "My Dear [Mormon] Friends,"July 11, 1850. Kane also prepared a memorandum detailing the Polk administration's anti-Mormon activity and promised the Mormons a copy in case of his death Also see "Text of a Conversation between Thomas L Kane,Wilford Woodruff, and John Bernhisel," November 25, 1849, and "Views of Col Thomas L Kane on a Government for Deseret," November 26, 1849, in Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff'sJournal, ed Scott G Kenney, 9 vols (Midvale, UT: Signature Books, 1985), 3:513-15 For further detail on Benton's antiMormonism, screened through the filter of Mormon leader Jedediah Grant, see Journal History, February 6,1855,2-3.

23 Kane toYoung, December 2,1846

24 Ibid

THOMAS L KANE

105

1846 he had placed articles in Philadelphia's "religious Whig organ," the Pennsylvanian: two describing the ruffianism that forced the Mormons from Nauvoo and another praising the deportment of the Mormon Battalion. The Pennsylvanian's editorial, printed next to one of the articles, revealed the newspaper's debt to Kane

A friend of ours,who has recently passed the summer months in the neighborhood of the camp of Mormon emigrants...has impressed us very deeply with a sense of the gross injustice which they have sustained from the bordermen of Illinois He speaks of thousands of men, women, and children, peaceable, industrious, and prospering, expelled without other cause of reproach, than the eccentricities of their religious faith One of the strange things that his account involves, is the want either of integrity or firmness in the newspapers of the West, from which public opinion has been forced to glean the material for its judgment in the case The truth, as we are assured, remains yet to be told; and woeful truth it is, most dishonoring to the American name. 25

Kane's success went beyond his most optimistic hope.A letter toYoung proclaimed his success and declared his intention to renew his campaign in NewYork City26 Two "weeks later, the New York Tribune published a frontpage, pro-Mormon piece with the headline: "The Mormons—Their Persecutions, Sufferings and Destitution." Next to it was an article taken from the U.S. Gazette that compared Mormon virtue with their enemies' sin Explaining the Tribune's coverage, editor Horace Greeley wrote of an unnamed informant, who from "extensive personal observation" testified to the good character ofthe Mormons and to the "sheer robbery,outrage, and lust" of their persecutors. "Eternal shame to Illinois for allowing...[the Mormons] to be so tortured and ravaged!"said Greeley27

Kane's address before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania was an even more effective piece of image-making. Kane accepted an invitation to speak to the group with an important stipulation: his subject would be announced only after the lecture had been prepared and was ready for delivery.With Kane's pro-Mormon role already being strongly criticized— leading political and religious figures had expostulated with him "almost beyond his endurance"—Kane wanted nothing to come between him and his intended pro-Mormon lecture.28

Unfortunately, his health refused to cooperate.As he prepared his lecture, "pain" and "weakness" so racked him that he held a pen with difficulty. Nevertheless,for a month he did not miss a single day of writing At night he continued his work, sometimes sitting on the edge of his bed,his feet in a pan of hot water, a kettle of strong tea beside him, and a brandy-soaked towel on his head. He hoped his writing, despite his pain, might achieve a

25 Pennsylvanian, November 25,1846, cited in Mark Sawin,"A Sentinel for the Saints," 24

26 Kane to Young, December 2, 1846 When these newspaper articles reached the Mormons at their Winter Quarters camp, they "gave great satisfaction." The Mormons believed that Kane was "doing us all the good he can."Journal Historyjanuary 17, 1847, 1, and January 29,1847, 4

27 NewYork Tribune, December 16, 1846, as cited in Mark Sawin,"A Sentinel for the Saints," 25

28 Orson Spencer to BrighamYoung, November 26, 1846

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

106

cool and detached style—perhaps,he said,he could imitate the result of the celebrated nineteenth-century clown Grimaldi, who "took care to dance with [the] most spirit when his gout was at his worst."29 When the time for his presentation arrived, Kane was physically carried to the lecture hall, where he was aided by a strong sedative and a determined will. "I am superstitious enough to believe [I was] spiritually sustained," he said. Although he finished his delivery without hemorrhaging, he collapsed on the way home and remained prostrate for several days. Reporting these events toYoung,Kane thought himself"quite likely to live,if only to swell the chapter ofMormon miracles."30

The lecture was warmly received by Mormons and those of other faiths. It had polish, restrained emotion, and interesting anecdote and detail—all told through the eyes of a supposedly neutral, on-the-scene observer. Kane understood that, for his audience of opinion-makers, the most effective advocacy was a soft voice that allowed readers to make their own judgment. One passage described the city of Nauvoo, quiet and forlorn, after the Mormon exodus.

I was descending the last hill-side upon my journey, when a landscape in delightful contrast broke upon my view Half encircled by a bend of the river a beautiful city lay glittering in the fresh morning sun;its bright new dwellings,set in cool green gardens, ranging up around a stately dome-shaped hill,which was crowned by a noble marble edifice, which high tapering spire was radiant with white and gold The city appeared to cover several miles,and beyond it, in the background, there rolled off a fair country, checkered by the careful lines of fruitful husbandry The unmistakable marks of industry, enterprise, and educated wealth, everywhere, made the scene one of singular and most striking beauty.

This halcyon depiction ended with a sharp disjuncture, calculated for emotion: "I looked," said Kane, "and saw no one."31 He was, of course, emphasizing the Mormon expulsion

The lecture did not weigh evidence or give a non-LDS point of view

Rather, Kane presented the evocative:Mormon virtue, Mormon suffering, and the Mormon expulsion.The result was powerful public relations. "Let the historian quibble about detail," Utah's territorial delegate John Bernhisel reportedly said after reading the lecture."Kane wasn't [just] writing history; he "was creating literature, giving the essence of an epic saga." For Bernhisel, hard at work in the Mormon cause,the lecture was "a masterpiece.

Kane's public relations campaign had two immediate effects. It made any U.S. action against the Mormons difficult, perhaps impossible, including

29 Kane to Young, September 24, 1850 Joseph Grimaldi (1778-1837) was sometimes described as the "father of modern clowning"; he popularized the white-face clown in distinction to the traditional Harlequin

30 Ibid

31 Thomas L Kane, The Mormons: A Discourse Delivered Before the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: King and Baird, Printers, 1850), 26.

32 Cited in Samuel W.Taylor, Nightfall at Nauvoo (NewYork: Macmillan, 1971), 15

THOMAS L KANE

107

Benton's rumored plan to force the Saints from their Winter Quarters campground Second, it had the by-product of helping raise funds in the eastern United States for the migrating and needy Mormons.To this end, Kane gave Mormon solicitors letters of introduction, convened a public meeting in the "Declaration Room" of Philadelphia's historic Independence Hall to support the fund-raising, and probably wrote a"Call for Sympathy" that circulated in the East He also appealed to his personal friends for donations and made his office a place of deposit. Thus, with Kane assuming "the responsibility of laying...[Mormon] claims before the public,"between $5,000 and $10,000 was raised.33 The money was desperately needed

Kane's support for the LDS cause did not end with image-making and fundraising. From his first visit with the Mormons in summer 1846, he believed that Mormon security required self-government. The question first arose ashe explored Mormon attitudes and Mormon settlement plans WouldYoung and other Mormon leaders accept a U.S.territorial government in theWest? And if so,on what terms?Young replied as though the Great Basin region that the Mormons hoped to settle was already U.S. territory, although theTreaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was not signed until two years later.Waving aside this technicality,Young expressed his willingness to accept aterritorial government and confirmed the matter several days later with aformal letter to Polk.According to thisletter,written likely at Kane's direction, the Mormons regarded the idea of a territorial government as "one of the richest boons of earth"—but with the provision that such a government should reflect local values.Ifasked to submit to territorial officers who delighted in"injustice and oppression, and whose greatest glory is to promote the misery of their fellows, for their own aggrandizement, or lustful gratification," the Mormon people,Young insisted, would retreat to "deserts/'"islands,"or"mountain caves."Young's plain words may have been prompted by Kane's inside information that a Mormon nemesis, former Missouri governor Lilburn W Boggs, was seeking a political appointment in theWest.34

Despite their hope of securing a territorial government on favorable terms, Mormon officials undoubtedly had mixed feeling about the U.S. government and those who administered it; their American loyalties were tested by their feeling of alienation arising from past persecutions Nor were they alone in their government suspicion. Looking atAmerican conditions through the prism ofhis stern idealism,Kane saw corruption,just as the Mormons did. "My heritage is among the mixed oppressors and oppressed.. of an ancient and corrupt society," he toldYoung Such views

33 See minutes of church conference in Silas Richards's house, December 3, 1847, General Church Minutes, LDS Church Archives, and Davis Bitton, "American Philanthropy and Mormon Refugees, 1846-1849,"Journal ofMormon History 7 (1980): 63-81.

34Journal History,August 7 and 9, 1846

UTAH HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

108

left Kane feeling estranged, apart.At one point in his career, he refused a Democratic party offer that he stand for Congress in what was deemed a "safe" seat and instead showed sympathy for the newly organized Free Soil party.What America needed was major reform, Kane believed, and he was unsure whether the nation was prepared for such a remedy. If"the angry waves of crime and passion" became too great, he toldYoung, he would leave Pennsylvania to seek haven among the Saints.35

Although Kane and Young had dark views about American society, especially of the men who led the nation, both understood the practical reasons for limited political activity: Some causes, after all,were worth the effort, like securing the Mormon commonwealth in the West. In April 1847,while the Saints still remained in NebraskaTerritory,Kane prepared a draft for American authorities on the question of Mormon territorial government and sent a copy to the Saints for approval. No doubt basing his document on his previous discussions with Young in Iowa, Kane sought imprecise but ambitious boundaries for a new Mormon territory: California's Sierra Nevada on the west; the Salmon River andWind River territory on the north; the Laramie plains in present-day eastern Wyoming on the east;and on the south the American border, which until the end of Mexican-American hostilities remained uncertain. It was a princely domain,more than twice the size ofthe state ofTexas.36

Kane's letter, significantly, showed that the Mormons were not only talking about an American territorial government but were also taking concrete steps to secure one.The point is important for historians who have claimed that church officials' talk about aKingdom of God meant that the Mormons, by going west,were seeking an immediate and independent temporal kingdom.This is a historical view that the Kane-Young letters do not support.37

When Kane sent his draft proposal on territorial boundaries to Winter Quarters, he requested that Mormon leaders respond by signing and returning blank sheets of paper.After learning of the Mormon reply to his proposal, Kane apparently hoped to write a more polished draft over the imprimatur of the Mormon signatures.The procedure, full of potential dangers for the Mormons, showed the trust that had grown between the two parties.The signed sheet,in other hands,would have been carte blanche for much mischief.

Neither Kane nor Mormon leaders chose to reveal their growing ties.To maintain their arrangement, news between the two often went by courier instead of U.S.mail, which was not always secure.And when government

35 Kane toYoung, September 24, 1850

36 Kane to Willard Richards,April 25, 1847

37 For a review of the literature on the topic of Mormon intentions as well as his own argument that the Mormons hoped for political independence, see Klaus J Hansen, Questfor Empire: The Political Kingdom of God and the Council of Fifty in Mormon History (East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1967), 111-20

THOMAS L KANE

109

mail was used, meaning might be expressed in veiled or carefully written language Both Kane and Mormon officials knew that his value as a Mormon lobbyist was based on his acting asan interested but semi-impartial humanitarian, not as a formal Mormon agent. In fact, the Mormons never sent "instructions" to Kane, only a periodic request or an exchange of information Kane would then act on his own, and his work might remain anonymous or only partly told, even to church leaders. Notwithstanding this freelance mode, Kane served Mormon interests as fully asifhe had been their emissary.

In February 1848 Mormon officials, now in the Great Basin,asked Kane to put the question ofterritorial government before Congress with "all the Agitation...the nature of the case will admit."38 When Washington took no action,Young and other Utah leaders in the winter of 1848—49prepared a petition for a territorial government that ran to twenty-two feet and contained 2,270 signatures.39 The Mormons' proposed slate of officers would have put church leaders firmly in control: Brigham Young, governor; Willard Richards (Young's second counselor), secretary of state; Heber C. Kimball (Young's first counselor),chiefjustice;and Newel K.Whitney (presiding bishop) and John Taylor (apostle), associate judges To present the petition inWashington, church leaders selected as their representative Dr. John M.Bernhisel, a quiet-spoken, fifty-year-old doctor who had attended the University of Pennsylvania.

In seeking territorial status, Mormon leaders wanted a government on their own terms.As they had told Polk in 1846,the new government must be democratic in the sense that its officers should be local citizens, not office-seekers selected by people in far-off Washington.40 Such a demand coincided with American political philosophy, which in turn reflected the checkered history of 170 years of British colonial rule. In fact, the American founding fathers felt so strongly about the issue that they produced the famed Northwest Ordinance of 1787,which promised settlers in new territories basic civil rights, increasing degrees of representative government based on population growth, and an orderly and quick transition to full statehood.41

Utah popular sovereignty met resistance inWashington for the same reasons that the Mormons wished it At issue was the question oflocal control as well as its corollary:What kind of social and political conditions would be permitted in Utah? If Mormons were appointed to territorial offices, they would continue their theocratic ways.Moreover, government officials

38 Young to Kane, February 9,1848, BrighamYoung Draft Letterbook, LDS Church Archives

39 Dale L Morgan, The State of Deseret (reprint, Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 26

40 For examples of this theme in LDS correspondence, see Evan M Green to Brigham Young, October 7, 1848, Journal History; and George A. Smith and Ezra T. Benson to Brigham Young, October 10, 1848, Journal History.

41 For an introduction to the American territorial system, see John Porter Bloom, ed., Conference on the History of the Territories of the United States (Athens, Ohio: University Press, 1973).

UTAH HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY

110

were hearing rumors of the Mormon practice of plural marriage Was the U.S government willing to give de facto recognition to this practice, too? When Kane spoke with Polk in late fall or winter 1848-49,he learned that the president was growing more cautious about his Mormon policy and wanted to appoint his own Utah officers For Kane,this opened the alarming prospect of "strutting...military politicians" who might injure the Mormons while filling their "pockets" with graft Thoroughly upset with Polk and without consultingYoung, Kane withdrew Utah's request for territorial government No U.S government for Utah was a better option than this kind of government, Kane believed It was his "last sad & painful interview"with Polk.42

When preparing their petition for territorial government, Mormon leaders had been unaware of the Kane-Polk interview; during the first years of Utah's settlement, six months might pass in wintertime between the receipt of eastern dispatches, and these might be delivered by slow-moving emigrants in early summer. 43 However, onjuly 1, 1849, Mormon leaders received news that they excitedly likened to "the revolutions of kingdoms" that "operated like the harvest shower on the earth."44 What was so momentous and"earth-shattering"? Likely,it was Kane's letter of November 26, 1848, apparently only now arriving in Utah, telling of Kane's final interview with Polk, along with all its troubling implication. In addition to this document, Kane's mood was recorded by Apostle Wilford Woodruff, who met with Kane in the East.According toWoodruff, Kane believed the appointment of non-LDS territorial officers would create the turmoil of two side-by-side governments, federal administration and church rule.Rather than accept such aprospect—"You owe...[the national government] nothing but kicks,cuffs and the treatment ofwicked dogs, for that is the only treatment you have received from their hands since you have been a people"—Kane advised Mormon officials to abandon their goal of a territorial government led by local leaders and to work instead toward statehood, which would free Utah of the threat of territorial appointees.As the Mormons pursued this new goal,Kane advised them to stay aloof from eastern factions agitating the question of extending slavery into the western territories.Mormon political objectives could best be met by building a broad-based coalition in which no easterner saw the Mormons asapolitical enemy 45

To the persecution-weary Mormons, the prospect of having hostile territorial officers in their midst seemed almost apocalyptic in consequence, especially if such officers were drawn from the U.S. military. For half a

42 "Text of Conversation between Thomas L. Kane and Wilford Woodruff and John M. Bernhisel."

43 Orson F.Whitney, History of Utah, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon & Sons, 1892), 1:392.

44 Willard Richards to KaneJuly 25,1849,Journal History

THOMAS L KANE

111

45 Kane's interviews with Woodruff took place at the end of 1849 See "Text of Conversation between Thomas L Kane and Wilford Woodruff and John M Bernhisel" and Wilford Woodruff Diary, December 4, 1849, LDS Church Archives

dozen years they had been hearing rumors (many coming from Kane) of a U.S. Army action against them, first in Nauvoo, then during the Iowa and Nebraska exodus, and now in Utah The latest news was all the more alarming because of its apparent source:Mormons trusted Kane and they trusted his appraisal of what nonLDS territorial appointees might bring, in part because Kane's strong feeling coincided so closely with their own.

Within weeks of receiving the July mail, Mormon leaders embarked on a remarkable course Following Kane's plan, they abandoned the idea of territorial government and adopted a determined, almost panic-stricken quest for statehood Their vehicle was the establishment of a provisional government, which they called "Deseret" (a Book of Mormon term meaning honeybee and symbolizing industry).The idea was to force the issue of statehood by implying the possibility or the reality of independence. Texas had succeeded with the tactic, and California was employing it at the very moment. Earlier, the ephemeral "states" of Franklin (embryonicTennessee) and Oregon may have hastened the process ofstatehood by using the maneuver. 46

When the Mormons submitted their State of Deseret constitution to Washington, they provided alist of qualifying events:apublic notice calling for a constitutional convention, February 1, 1849; a five-day convention beginning on March 5; and the convening of Deseret's legislature to request that the new state be admitted into the Union "on equal footing with other states," on July 9. But historian Peter Crawley's study of the period suggests that none of these events actually took place.47 Anxious to slow the hostile policies ofPolk and his successor ZacharyTaylor and worried about getting aresponse toWashington asquickly aspossible given the poor overland communications, Mormon officials apparently invented each of these incidents. Perhaps Mormon leaders hoped that their will (and political need) might be taken for the deed.

While it was apolitical and public relations ploy,the State ofDeseret also expressed Utah attitudes. Once more, the Mormon appetite for land was clear. Although on the east and south they gave up claim to parts of

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Utah Territory delegate and state hood lobbyist John Bernhisel.

USHS Photo

46 Dale L Morgan, The State ofDeseret (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987), 7-8, fn

112

47 Peter Crawley, "The Constitution of the State of Deseret," BrighamYoung University Studies 29 (Fall 1989): 7-22

present-day Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico, their desire to occupy the central core of the Intermountain West remained. On the question of leadership, the State of Deseret again petitioned that Mormon leaders might serve as secular leaders: Brigham Young as governor, Heber C. Kimball as lieutenant governor, Willard Richards as secretary of state, and a group of second-tier Mormons as members of the legislature andjudiciary.48

"The little sapling, then in form of territorial government, has assumed the features of the mountain pine, under the name of the State of Deseret," Willard Richards,Young's counselor, wrote Kane in lateJuly. Richards also assured Kane that the Saints intended to follow his advice by remaining apart from sectional controversy: "Of slavery,anti-slaveryWilmot provisos,etc., we, in our organization, have remained silent."49 Accepting another item of Kane's counsel,the Mormons tried to appear not "too Mormon" by selecting Almon Babbitt as the State of Deseret's representative to Washington. Babbitt, anominal Church member and partisan Democrat, seemed a good choice to meet congressmen on their terms. "I dont care if he drinks Champagne & knocks over a few Lawyers & Priests all right—he has a right to fight in hell," saidYoung with rhetorical flourish.50 Deseret was engaging Congress on its own terms.

During the crucial negotiations for a Utah government, Utahns had three representatives inWashington: Kane,Babbitt, and Bernhisel In Kane's mind,Young had chosen too well with Babbitt, whom he saw as a "small politician but a rough one of the Missouri Stamp"—an allusion to querulousTom Benton This censure,unusual for Kane,deepened as the congressional session went forward Kane thought that Babbitt was always "weaving paltry[,] peter funk combinations, incubating trivial[,] five pennybit leagues,making declarations and pledges whose inconsistency he was at no pains to reconcile, and confiding to everybody the keeping of secrets that he had no power to keep himself One could have believed nature to have

48 Ibid., 11,15

49 Richards to KaneJuly 25, 1849Journal History Nothing illustrates the shift in Mormon policy as much as a comparison of this letter with another sent to Kane two and a half months earlier The earlier letter had expressed a desire for territorial government; see Richards to Kane, May 2, 1849, Journal History.

50 Brigham Young, RemarksJuly 8, 1849, General Church Minutes, LDS Church Archives.

THOMAS

L KANE

Almon Babbitt, State of Deseret's representative in Washington.

USHS Photo

113

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

gifted him "with a kind of instinct opposed to truthfulness."51

In contrast, Kane thought Bernhisel was poles apart from Babbitt While the choice of Babbitt as the State of Deseret's official representative technically put Bernhisel on the sidelines (his official assignment was to represent Utah's request for a territorial government), Bernhisel took lodging at the National Hotel—"the centre ofpolitics,fashion and folly"52—and began to cultivate Washington's opinion-makers, who eventually would praise him by citing small virtues: he was dutiful, selfless, and an unpretentious gentleman.While Kane at first also described him narrowly, citing his "modest good sense"and "careful purpose to do right,"Kane came to abroader estimation Many Washington politicians were "faster horses for the Quarter heat" than Bernhisel, Kane thought.Yet "I do not think I know another Member [of Congress] of whom I could assert "with equal confidence that, in all his career, he has not committed one grave mistake or been betrayed into a single false position."33 Bernhisel ran the long race

The Congressional session of 1849—50 was tumultuous.At issue was the Mexican cession of land, made more difficult by the question of whether slavery should be extended into the territories To solve the national North—South crisis, president-elect Zachary Taylor floated the idea of admitting California and Utah as a single state "with no mention of slavery but with the understanding that the new unit would likely be a free state.A de facto, non-slave California—Utah might thereby balance the large and recently admitted pro-slavery state ofTexas;each state -would be subdivided in the future.54 The plan was designed to get the issue of slavery out of the halls of Congress and leave it to local determination. When Californians rejected the proposal,Taylor, no longer having a reason to restrain his feeling about the Mormons, reportedly called them a"pack of out-laws," unfit for self-government, either territorial government or statehood.55

By March 1850, Utah's future seemed bleak.The Mormons' worst fears seemed to be coming to pass."I am thoroughly convinced from my knowledge of the views and feelings of the President and his Cabinet," Bernhisel wrote Young, "that they would not nominate the present officers [of the State of Deseret],nor any persons that we should select, and if they did, the Senate "would not confirm them." Instead of Mormon officers, Bernhisel predicted the appointment of "hungry office hunters"—"whippersnappers,"he called them—who would be willing to "make a man [an] offender for a word."56 Among Bemhisel's sources of information was Stephen A.

51 "Text of Conversation between Thomas L Kane and Wilford Woodruff and John M Bernhisel"; Kane to Young and Advisers, September 24, 1850; and Kane to Young, Heber C Kimball, and Willard Richards, February 19, 1851.

52 Bernhisel to the First Presidency, March 21, 1850Journal History

53 Kane toYoung, September 24, 1850; and Kane to YoungJanuary 5, 1855.

54 B H Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1930) 3:437-39; Dale L Morgan, The State of Deseret, 39

"Babbitt toYoungJuly 7, 1850Journal History.

56 Bernhisel to the First Presidency, March 5, 1850Journal History

114

Douglas, chairman of the U.S Senate's Committee on Territories, who extended no hope that a church leader could receive a territorial appointment.57

Then, suddenly and unexpectedly, the gloom began to lift. American political leaders led by Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky proposed an "omnibus"ofmeasures designed to solve the western problem and preserve the Union. Later known as the Compromise of 1850, these measures balanced sectional concerns with such diverse provisions as (1) the establishment of northern and western boundaries ofTexas and the agreement not to admit states from adismemberedTexas;(2) the admission of California as a free state; (3) the side-by-side organization of territorial governments of New Mexico and Utah; (4) the passage ofastringent fugitive slavelaw; and (5) the prohibition of the slave trade in the nation's capital.These "compromise" measures, largely in their original form, passed the House on September 7, 1850,and two dayslater passed the Senate.

The Compromise of 1850 effectively ended the provisional State of Deseret and with it several of the Mormons' most cherished hopes. Although the Mormons would seek statehood repeatedly during the next forty years, the central government had decided that that quest would be settled on its terms and not the Mormons'. Even the theological and uniquely Mormon name of "Deseret" had to be surrendered, as the Compromise of 1850 chose "Utah" as the name for the new territory. Still more disturbing to the Saints, Congress severely pared the new territory's proposed borders, rejecting the Mormon argument that the territory must be expansive to support apopulation in semiarid conditions.The new borders, enclosing much of the present states of Utah and Nevada, curbed Mormon ambitions and created artificial, not topographical, boundaries on the north and south ("The ignorance of the collected wisdom of the nation in regard to our region of country is most profound," groused Bernhisel58).

Of course, the crucial question remained—the concern that lay behind the Mormon exodus west and four years ofsubsequent political maneuvering,including the singular step of manufacturing "founding events"for the State of Deseret.Would the Mormons have self-rule? Or would outsiders be appointed for the new territory of Utah?

Bemhisel's dispatches began to brighten. Shortly after the passage of the act creating theTerritory of Utah, he reported that the new U.S.president, Millard Fillmore (Taylor died after only four months in office), was seeking national conciliation, even for the Mormons. In fact, Fillmore, surprisingly, seemed "favorably disposed" to the appointment ofYoung as Utah's governor. 59

57 Bernhisel toYoung, March 27, 1850Journal History

58 Bernhisel toYoung, September 7, 1850,Journal History

59Bernhisel to Young, September 12, 1850, Journal History, and Bernhisel to Millard Fillmore, September 16, 1850Journal History

THOMAS L KANE

115

What had happened? Several factors, each cumulative in effect and perhaps none decisive, were responsible for Utah's improving prospects. Young's State of Deseret had presented the government with the difficult choice of overturning the status quo, while Bemhisel's patient diplomacy had had an effect, too.Perhaps still more important was the nation's shifting climate of opinion. Emotionally spent after months of sectional wrangling, the country's leaders were in no mood to test Mormon resolve by appointing officials unacceptable to them

However, Utah's prospects also owed a debt to Kane The impact of his public relations campaign had the good fortune to crest just as the grand compromise was being forged—late summer 1850.When Kane had given his lecture in March, he at first believed that it would accomplish everything that he desired The "battle"to improve the Mormon reputation was won, he toldYoung at the time "There is nothing more left to do than scatter here or there a routed squad or two, and bury the dead upon the field."60

Bernhisel,sensing the contrary political wind in early 1850,knew better. He urged Kane to publish the lecture and hurried to Philadelphia to aid with its editing At first 1,000 copies were issued, "very handsomely got up,"at a cost of about $150,which Kane apparently bore However, byJuly the document was proving so popular that an edition of another 500 was run. Kane himself helped with the circulation. He sent a copy to each U.S. senator and to three-quarters of the congressmen, who reportedly were "highly pleased with it." Bernhisel made a further distribution: Copies went to Bemhisel's personal friends, government leaders, local libraries, PresidentTaylor,and to"corps editorial."61

Perhaps to maximize its effect, for the first and only time Kane allowed his name to be attached to his writing about the Mormons."It is contrary to my Rule to print anything of literary pretension over my signature," he toldYoung,"but I embraced this opportunity of expressing some...of my regard."62 Because ofKane's high-profile name and especially because of the pamphlet's skillful prose, public opinion began to shift. Men and women might continue to be put off by Mormonism's religious claims, but after reading Kane's work they were more willing to accept the Mormon people ashard-working and wronged Nor was the effect fleeting Throughout the rest of the century, The Mormons would be quoted again and again by a stream of derivative works,its impact reaching asfar asEurope.Even urbane France had few readers left "unmoved"by its evocation.63

After Kane delivered his lecture, the crisis of his health deepened, and

60 Kane to "My Dear Friends,"July 11, 1850

"Bernhisel to Young, May 24, 1850Journal History, 2; and Bernhisel to YoungJuly 3, 1850 Journal History, 4—5

62 Kane toYoung, September 24,1850

63Wilfried Decoo, "The Image of Mormonism in French Literature: Part I," Brigham YoungUniversity Studies 14 (Winter 1974): 162

UTAH

HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

116

despairing doctors prescribed a trip to theWest Indies as perhaps his only chance of recovery. 6 4 Anxious to remain near climaxing events in Washington, Kane refused to go, and he won his gamble by beginning a slow recovery. If too ill to lobby during the titanic 1850 congressional session, Kane was able to give Bernhisel and Babbitt valuable backroom advice about decision-makers and policy Once again, he warned that the Mormons must remain aloof from sectional controversy

In late summer he assumed a larger role As Fillmore grappled with the question of Utah appointments for the new territory, Kane returned to Washington to meet with Fillmore several times The two had met earlier during the Free Soil movement and had liked each other.65 Although Kane did not make a full record of their discussions,he did reveal several important details Seeking a deft political compromise that might displease the fewest people, at first Fillmore asked Kane to accept the Utah governorship.66 Kane refused

At another point in their ongoing discussion, Fillmore invited Kane to speak, "not as a politician" but "as a gentleman," about Young's qualifications for appointment. In an age offormal honor and propriety,the request was designed to lay aside partisanship for candor. Kane responded by vouching for Young's "excellent capacity, energy and integrity" and his "irreproachable moral character," ajudgment based on Kane's "intimate personal knowledge." He would later strengthen his recommendation by placing it in writing In response, Fillmore claimed to be "fully satisfied" with Kane's assurances and nominatedYoung asUtahTerritory's first governor. 67 Fillmore had"relied much" on Kane's witness,he would later say. 68

As part of his decision, Fillmore agreed to appoint a broad slate of Mormon officers to Utah's new territorial government The president, Kane reported,was a democrat in the full sense of the term, opposed to the "principle ofmonarchy and centralism by naming aViceroy or Governor-General over the Mormons asasubject people."69 Unfortunately, Fillmore'splans were undermined by Babbitt's machinations Seeking apersonal advantage, Babbitt tried to change the proposed list ofMormon-favored officials by nominating some of his friends We "nearly lost the whole," said Kane Although Kane moved quickly to staunch the harm, the incident probably cost the Mormons one or two appointments.70

When Fillmore at last announced his nominations, they included

64 Bernhisel toYoung, March 27, 1850,Journal History, 4

65 Kane toYoung, Kimball, and RichardsJuly 29, 1851

66 When the Taylor proposal to admit a unified California-Utah was being discussed, Kane had also rejected an offer to become a U.S senator from the new state See Bernhisel to Robert PattersonJune 29, 1859

67 Kane to Young, Kimball, and RichardsJuly 29, 1851, Kane Papers For Kane's written assurances, see Kane to FillmoreJuly 11, 1851

68 Millard Fillmore to Kanejuly 4, 1851 Journal History, 11

69 Kane to Franklin Pierce, September 3, 1854.

70 Kane toYoung, Kimball, and Richards, February 19, 1851.

THOMAS L KANE

117

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Brigham Young, governor; Broughton D Harris, secretary; Joseph Buffington, chiefjustice (later replaced by Lemuel G. Brandebury); Perry C. Brocchus and Zerubbabel Snow, associate justices; Seth M. Blair, U.S. attorney; and Joseph L Heywood, marshal The nominations of Young, Blair, Heywood, and Snow (a non-practicing but recently rebaptized Mormon) met Mormons' hopes;Harris,Brandebury, and Brocchus did not. Still,Bernhisel was probably close to the truth when he put the best face on the government's action."The appointing power has been far more liberal to us, than it has ever been to any other Territory," he told Young.71 Young's appointment, of course,was the key one,allowing the Mormons to retain control oftheir government.

Recognizing Kane's achievement, Bernhisel presented the Mormons' friend with an elegant robe of wolf and fox skins lined with drugget and tipped with scarlet—"the most splendid sleigh robe ever seen," Bernhisel thought.72 After receiving the garment, Kane first displayed it as an "ornament" in his Independence Hall office Still later he loaned it to his brother Elisha,who used it on hisArctic expeditions. InformingYoung of its transfer, Thomas, tongue-in-cheek, spoke of it as "the first missionary of Mormonism to the North Pole."73

Kane also had professional debts to pay, and he, too, used a token to express his thanks.Taking a set of Deseret-minted gold coins that Young had sent him, Kane commissioned the manufacture of signet rings, which he then sent to "leading friends" who had helped in his campaign to mold public opinion While Kane did not leave a complete record of recipients, NewYork Tribune editor Horace Greeley was one of the first.74

News that Utah had been organized into a U.S. territory reached Salt Lake City in the middle of October.Then, a month later, Mormon leaders in Salt Lake City talked about the matter during one of their desultory discussions that served to unify and inform the Mormon leadership At the time,Young and the others were not aware ofYoung's appointment as governor. Nor did they know of Kane's crucial lobbying with Fillmore. However, they knew enough of Kane's activity to describe it as one of "the richest gifts of heaven till this weary pilgrimage is done."75 Kane's role in the political maneuvering had been in fact decisive

However, something as complete had worked within Kane himself. During the troubled summer of 1850 when both his life and the Mormon cause seemed at risk, Kane had taken the time to look back on events, and in the process he wrote a passage to his Mormon friends that was both biographically and historically revealing "Our relations have much changed

71 Bernhisel toYoung, November 9, 1850Journal History

72 John M Bernhisel, Remarks, August 3, 1851, General Church Minutes, LDS Church Archives

73 Kane to Young and "Immediate Advisors," September 24, 1850, and Kane to Brigham Young, Kimball, and Richards, February 19, 1851

74 Young to Kane, October 20, 1849, and Kane toYoung, September 24, 1850

7Journal History, November 20, 1850, 4

118

from what Fortune and Mr.Polk seemed originally to intend them to be," he reminisced in the warm tones that an expected death can bring

I thought myself near enough to some ofyou,when you bade me God speed, beyond the Missouri;but in little more than a month after, I was committed beyond recovery to the course which I had afterwards to pursue, and then, from being your friend, in the sense of your second in an affair of honor, it happened that the personal assaults upon myselfmade your cause become so identified with my own that your vindication became my own defense and as"partners in iniquity," (to quote one particular blackguard of those times) we had to stand or fall, together This probation it is, that has made me feel our brotherhood, and taught me, in the nearly four years that have elapsed since Ileft the Camp where your kind nursing saved my life,to know from the heart,that Ilove you,and that you love me in return.76

It was not simply that the careers of Kane and the Mormons had become joined. Kane sensed that he had become "morally more or less a changed man" and that there was "something higher and better than the pursuit of the interests ofearthly life for the spirit made after the image ofDeity."77

Kane sometimes lapsed into melodrama, and during the summer of 1850 he wondered ifhe should bequeath his heart to the Mormons,to be placed in the yet-to-be-built Salt Lake Temple "that, after death, it may repose, where in metaphor at least it often was when living."78 Yet, as before, human uncertainty asserted itself. Instead of falling to an early death, the fragile, often-on-the-precipice Kane would live for another thirty years, outlasting most of the LDS men and "women "whom he had met in 1846, includingYoung. During these remaining years, Kane -would continue to serve notjust the Mormons,but other causes"turned desperate,"to use his own phrase.And he would realize, at least in part, an epitaph that he had once held out as an ideal—to serve society as one of its "unthanked and unrewarded pioneers of unpopular reform."79 That, of course,isyet another story

'Kane to "My Dear Friends,"July 11, 1850.

1 Ibid

THOMAS L KANE

Ibid 119

1 Ibid 1

Wanda Robertson: A Teacher for Topaz

By MARIAN ROBERTSON WILSON

By MARIAN ROBERTSON WILSON

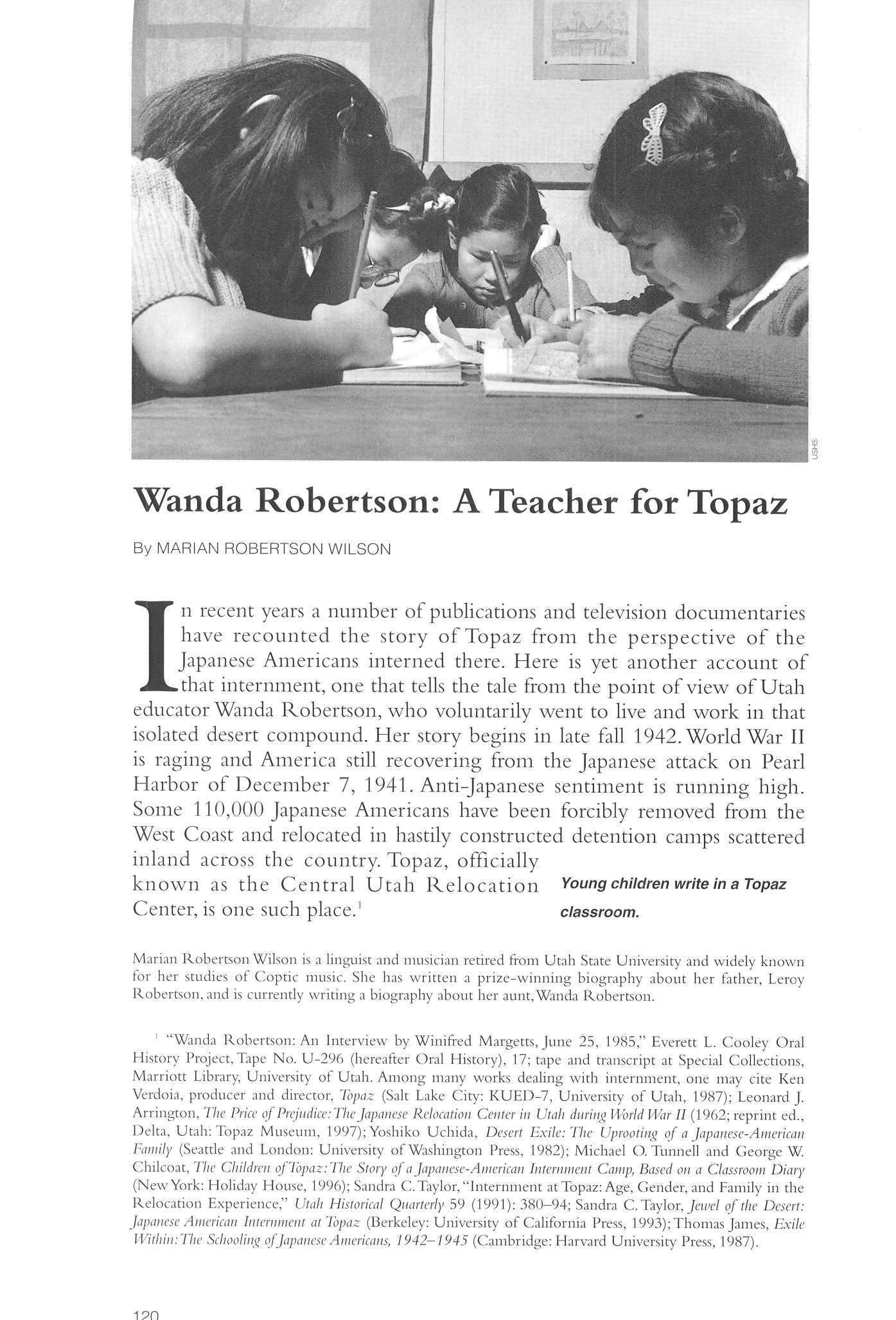

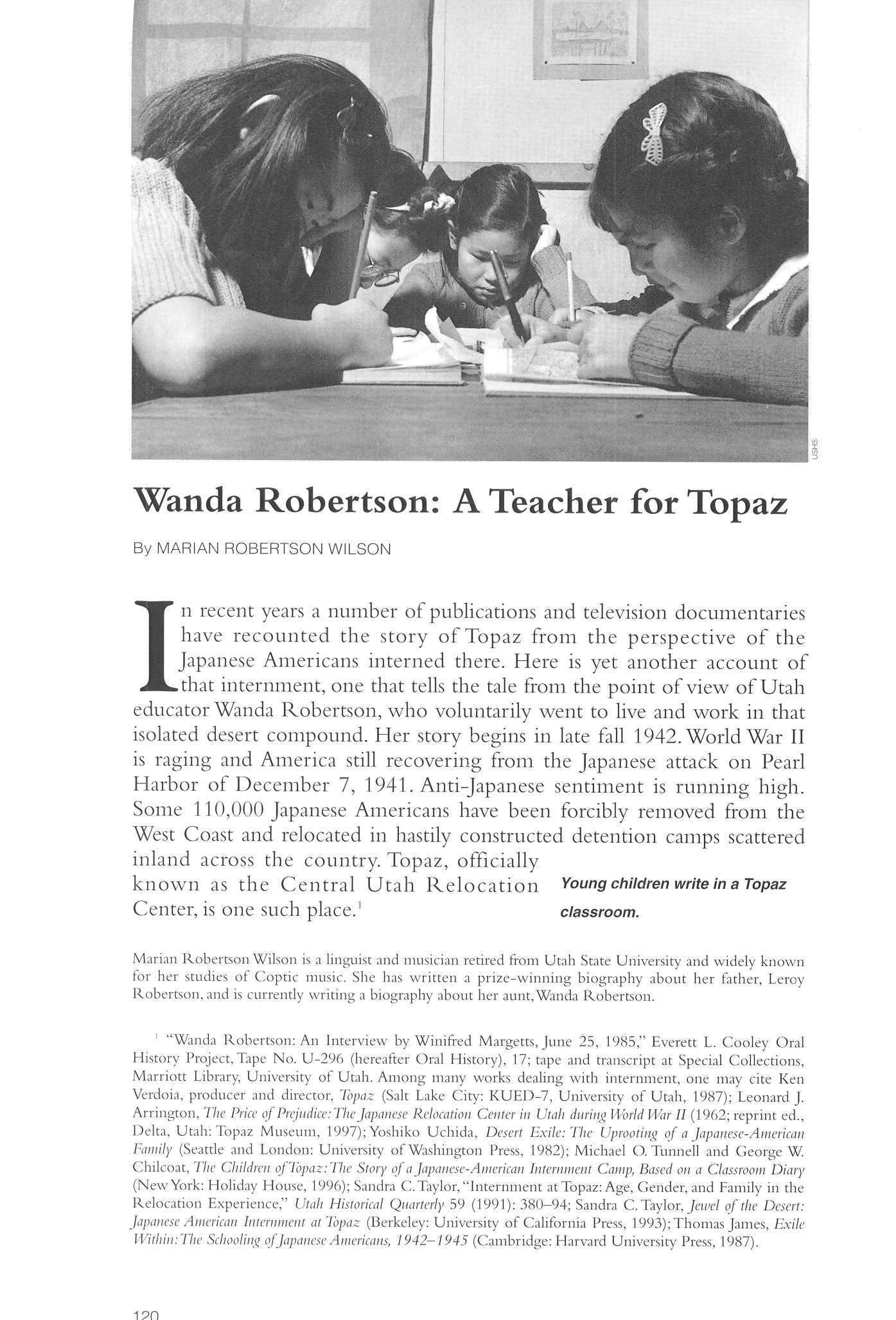

In recent years a number of publications and television documentaries have recounted the story of Topaz from the perspective of the Japanese Americans interned there. Here is yet another account of that internment, one that tells the tale from the point ofview of Utah educatorWanda Robertson, who voluntarily went to live and work in that isolated desert compound. Her story begins in late fall 1942.WorldWar II is raging and America still recovering from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor of December 7, 1941 Anti-Japanese sentiment is running high Some 110,000 Japanese Americans have been forcibly removed from the West Coast and relocated in hastily constructed detention camps scattered inland across the country. Topaz, officially known as the Central Utah Relocation Young children write in a Topaz Center, isone such place.1 classroom.

Marian Robertson Wilson is a linguist and musician retired from Utah State University and widely known for her studies of Coptic music. She has written a prize-winning biography about her father, Leroy Robertson, and is currently writing a biography about her aunt,Wanda Robertson

"Wanda Robertson: An Interview by Winifred Margetts, June 25, 1985," Everett L Cooley Oral History Project,Tape No. U-296 (hereafter Oral History), 17; tape and transcript at Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah Among many works dealing with internment, one may cite Ken Verdoia, producer and director, Topaz (Salt Lake City: KUED-7, University of Utah, 1987); LeonardJ Arrington, The Price of Prejudice:TheJapanese Relocation Center in Utah duringWorld War II (1962; reprint ed., Delta, Utah: Topaz Museum, 1997); Yoshiko Uchida, Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese-American Family (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 1982); Michael O Tunnell and George W Chilcoat, The Children ofTopaz:The Story of aJapanese-American Internment Camp, Based on a Classroom Diary (New York: Holiday House, 1996); Sandra C.Taylor, "Internment at Topaz:Age, Gender, and Family in the Relocation Experience," Utah Historical Quarterly 59 (1991): 380-94; Sandra C Taylor, Jewel of the Desert: Japanese American Internment at Topaz (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993);Thomas James, Exile Within: The Schooling ofJapaneseAmericans, 1942-1945 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987)

i? n

Fresh from Columbia University's Teachers College and a well-liked instructor at the University of Utah's Stewart Teacher Training School,2 Miss Robertson has just been asked to become supervisor of elementary education at Topaz, a position she would very much like to accept Accordingly, she meets to discuss the situation with her administrative superior, the dean of the College of Education. After a few minutes, the dean—reflecting the current attitude—avers, "Wanda, I am not sure the University of Utah would approve of any faculty member going out to help those people," to which Wanda replies, "I am not sure I want to be affiliated with any university that would object."3 She did succeed in securing aleave of absence from the university, set to begin in mid-December at the end offall quarter Very soon thereafter, off she drove to Topaz

Why would this thirty-nine-year-old woman so staunchly oppose the prevailing mood of the country, face ridicule from her family, and risk a promising university career at this point in her life? Her answer was that she found all war very ugly, and going to Topaz was her way to ease troubles.4 But there were other commanding reasons as well. From her earliest years,Wanda had by nature been very independent and extremely curious to know about the diverse folk who lived both within and beyond the mountain-rimmed valleys of her native Utah. Even before Topaz, her adventurous ways had taken her to teach in many schools far and wide.

According to family records,Wanda Melissa Robertson -was born May 10, 1903,toJasper Heber and Alice Almyra Adams Robertson in Fountain Green, a thriving Mormon community nestled at the base of Mount Nebo in northern Sanpete County. She once described her childhood as"just an old-fashioned country life...a very simple life, good, but very simple."5 As a youngster she did the chores and played the games common to most little girls growing up in rural Utah, with but one exception. She loved to help her sheep-raising father, especially at lambing time when, among other duties,she tenderly cared for the newborn "starvy lambs"thatJasper placed in her arms to keep alive and bleating when their mothers rejected them.6

2 The Stewart Teacher Training School, named for University of Utah professor William M Stewart, was founded in 1891 in order to give student teachers the experience of teaching under the supervision of professionals During Wanda's tenure, it served kindergarten through sixth grades The building it occupied, southwest of the present Utah Museum of Natural History, was demolished after the school closed in 1965.

3 Wanda Robertson, conversation with author, Salt Lake City, early 1950s At this time the dean of the College of Education was John Wahlquist.

4 Renee Robertson Whitesides, interview 'with author, Kaysville, Utah, August 30, 1998 Whitesides is Wanda's niece and also took teacher-training classes from her Unless otherwise indicated, all notes of interviews are in possession of the author

5 "Family Records" in possession of Renee R Whitesides, Kaysville, Utah Wanda Robertson, interview with Brenda Anderson Daines, Salt Lake City, c 1985, 9-10 (hereafter Daines interview), transcript in scrapbook about Wanda Robertson compiled by Brenda's mother, Nancy O Anderson, Nephi, Utah I thank Brenda's parents for kindly lending me this scrapbook. Wanda was the fourth of seven children, six of whom grew to maturity

6 Oral History, 2

WANDA

ROBERTSON

121

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

She wasalso intrigued bythecolorful gypsies who came to Fountain Green hawking their wares; and she envied the family of mixed ethnicity living at the west end of town, whose long and lusty parties heard throughout the valley often kept her awake.Wanda wistfully felt that those celebrating westenders "always seemed to have themostfun." She loved music, could play by ear any tune she heard, and spent hours listening to the recordings ofclassical music brought home by her older brother Leroy7

She attended school first atFountain Green Elementary, then Moroni High School, and finally Snow College in Ephraim, where she earned aNormal Degree (then the equivalent ofa five-year teaching certificate).Already shehaddecided tospend herlife teaching children.The title ofhervaledictory address at Snow typifies her lifelong thinking: "Where there is no vision, the people perish." Descriptions byclassmates also characterize herwell:"Full ofpep,talkingis her chief occupation [She] loves street meetings."8

After graduating from Snow, Robertson eagerly began teaching atage nineteen, and she would prove to be a"natural."Very tall, very thin,and always impeccably dressed with nary astrand ofher thick black hair outof place,shepresented quite animposing figure to herstudents Nonetheless, from the outset she easily related to each child. As one of her former fourth-graders would later reminisce:

[At last] I had a teacher who liked me! No matter that she seemed to like all the other kids as well How did she know my name before I knew hers?.. And how did she make me feel right from the start that I was going to like. .school?.. If it had been her style, she could have been the envy of any disciplinary schoolmarm, but in her classroom discipline was not imposed—it just seemed to happen I cannot picture her seated. Much of the time, almost imperceptibly, she moved around the room in a way that allowed her to engage every student...[of which] the primary effect was to form a bond with each student and with the class We didn't need to be told, as we often were...that Miss Robertson was a vital, caring person and a truly exceptional teacher. We knew that almost from day one. 9

7 Wanda Robertson, interview with author, Salt Lake City, December 1980, tape in Addenda to the Leroy J Robertson Collection, Special Collections, Marriott Library, University of Utah Wanda's brother, Leroy Robertson, would go on to gain international recognition as a composer For more information about Wanda's childhood and the Robertson family's early years in Fountain Green, see Marian Robertson Wilson, Leroy Robertson: Music Giantfrom theRockies (Salt Lake City: Blue Ribbon Publications, 1996), 7-29

8 Wanda took this title from Proverbs 29:8. For the valedictory address, see Oral History, 8. For the classmate descriptions, see Robertson's copy of the Snow College Snowonian, 1921—22, where these comments are found under her class picture and autographed on the back flyleaf. This copy waskindly lent to me by the Development Office of Snow College

9 Gordon E.Porter, Utah State University professor emeritus, to author, November 17,1998. Copies of all letters cited arein the author's possession.

Wanda Robertson, c. 1939.

122

During these early teaching years Wanda managed to earn a bachelor's degree from Brigham Young University and a master's from Columbia University in New York, mostly by going to summer school and taking correspondence courses. 10

Before Topaz,Wanda taught both in Utah's Mormon farming communities and in the mining towns ofPark City and Bingham Canyon,where the children's immigrant families came from more than twenty countries, spoke different languages,and were often in conflict with each other How Wanda herself learned from these diverse children, and in turn helped them listen to and learn about each other, makes a tale to be told elsewhere.11 She met another challenge at Logan'sWhittier School,which was then connected to the Utah State Agricultural College as a teacher-training institution similar to Stewart School Here she not only had to teach the children but also arrange programs for the student teachers (trainees).12 The mid-1930s would find her in New York City teaching at the prestigious Lincoln School, then associated with Columbia University's Teachers College and recognized for its innovative teaching programs At Lincoln she worked with the children of some of the nation's "most rich and famous," many of whose parents had also emigrated from several countries According to Wanda,these youngsters,too,had their problems.13

Wanda may well have remained in NewYork City the rest of her life, for she loved the diversity of its people and the offerings ofits many museums, theaters,and concert halls But astime wore on she came to feel ever more isolated from her loved ones in Utah, and at the outset ofWorldWar II in 1939 she decided to return home By 1940 she was teaching at Stewart School,and in late 1942 she moved on toTopaz.14

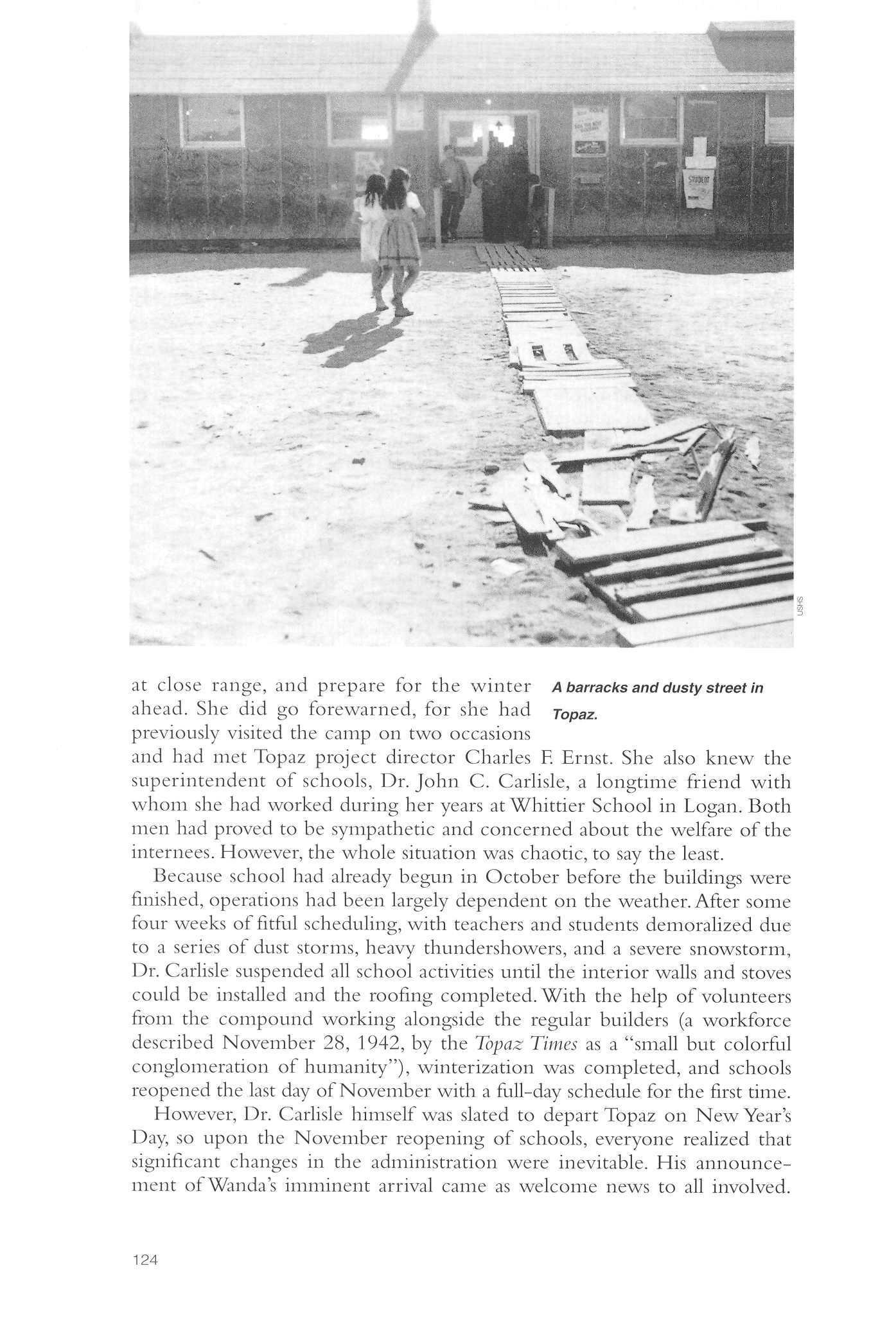

Although Wanda was not due to begin work at Topaz until December 31,she arrived a couple ofweeks early in order to settle in,assay conditions