HISTORICAL

QUARTERLY 1 NUMBER 3

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY (ISSN 0042-143X)

EDITORIAL STAFF

WILSON G. MARTIN, Editor

STANFORDJ. LAYTON, Managing Editor

KRISTEN SMART ROGERS, Associate Editor

ALLAN KENT POWELL, Book Review Editor

ADVISORY BOARD OF EDITORS

NOEL A. CARMACK, Hyrum, 2003

LEE ANN KREUTZER,Torrey, 2003

ROBERT S. MCPHERSON, Blanding, 2004

MIRIAM B. MURPHY, Murray, 2003

ANTONETTE CHAMBERS NOBLE, Cora,m, 2002

JANET BURTON SEEGMILLER, Cedar City, 2002

JOHN SILLITO, Ogden, 2004

GARY TOPPING, Salt Lake City, 2002

RONALD G.WATT,~~S~ Valley City, 2004

Utah Historical Quarterly was established in 1928 to publish articles, documents, and reviews contributing to knowledge of Utah history. The Quarterly is published four times a year by the Utah State Historical Society, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101. Phone (801) 533-3500 for membership and publications information. Members of the Society receive the Quarterly, Beehive History, Utah Preservation, and the bimonthly newsletter upon payment of the annual dues: individual, $25; institution, $25; student and senior citizen (age sixty-five or older), $20; sustaining, $35; patron, $50; business, $100.

Manuscripts submitted for publication should be double-spaced with endnotes. Authors are encouraged to include a PC diskette with the submission. For additional information on requirements, contact the managing editor. Articles and book reviews represent the views of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Utah State Historical Society.

Periodicals postage is paid at Salt Lake City, Utah.

POSTMASTER: Send address change to Utah Historical Quarterly, 300 Rio Grande, Salt Lake City, Utah 84101.

194 IN THIS ISSUE

196 An Immigrant Story: Three Orphaned Italians in Early Utah Territory

By Michael W Homer

215 Wakara Meets the Mormons, 1848-52: A Case Study in Native American Accommodation

By Ronald W Walker

238 "Electricity for Everything": The Progress Company and the Electrification of Rural Salt Lake County, 1897-1924

By Judson Callaway and Su Richards

258 The Fight at Soldier Crossing, 1884: Military Considerations in Canyon Country

By Robert S. McPherson and Winston B. Hurst

282 BOOK REVIEWS

Maureen Trudelle. Navajo Lfeways: Contemporary Issues, Ancient Knowledge

Reviewed by Nancy C. Maryboy

Eileen Hallet Stone. A Homeland in the West: UtahJews Remember

Reviewed by Jeanne Abrams

Charles M.Robinson 111. General Crook and the Western Frontier

Reviewed by Mark R. Grandstaff '

Stanford J. Layton, ed., Being Dgerent: Stories of Utah5 Minorities

Reviewed by Linda Sillitoe

Jackson J. Benson. Down by the Lemonade Springs: Essays on Wallace Stegner

Reviewed by Russell Burrows

David M. Wrobel and Patrick T. Long, eds. Seeing and Being Seen: Tourism in the American West

Reviewed by Wilson Martin

293 BOOK NOTICES

SUMMER 2002 VOLUME 70 NUMBER3

O COPYRIGHT 2002 UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The basic story of Utah's "new immigrants" will be familiar to long-time readers of Utah Historical Quarterly. These were the people who came to Utah from eastern, southern, and southeastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to find work in the mines, in smelters, on the railroads, and elsewhere as blue-collar workers. They came in sizeable numbers, tended to be nonMormons who settled in ethnic enclaves, and took two or three generations to integrate fully into the social mainstream.

Much less common were immigrants from these more distant European ports who came as LDS converts during the pioneer period. Daniel, Antoinette, and Jacques (James) Bertoch were three such people. Converted Waldensians, these young people left Piedmont for Zion in 1854 and experienced an incredible series of adventures that have somehow escaped the attention of historians until now. Their amazing saga is detailed in our first article.

Taking place at the same time were talks and negotiations between territorial leaders and the Ute leader Wakara. A complex, mercurial man, Wakara was (and continues to be) many things to many people. Historians have been fascinated by him from the beginning, and several of their portraits have graced the pages of this journal through the years. Our second article builds on previous studies by adding much new detail and insight as it focuses on the years before the Walker War. Written with sensitivity and

IN THIS ISSUE

balance, it endows this important personality with flesh-and-blood traits never before delineated so well.

Our third article has the feel of modernity as it centers on the coming of electrical power to rural Salt Lake County from the 1880s to the 1920s. The Progress Company was an important pioneer in this far-reaching technology, and its turbulent history is well told in these pages for the first time.

Hard to believe-but true-electrical power had already found its way into some businesses and along city streets in Murray and Salt Lake City as cowboys, Indians, and U.S. soldiers were still engaged in Wild West-styled shootouts elsewhere in the territory. A fast-paced, confusing skirmish at Soldier Crossing in San Juan County, poorly understood by contemporary observers and variously interpreted by historians since, is finally analyzed and explained by two energetic, on-the-ground researchers in our concluding article. It is an appropriate capstone to this issue, combining with the preceding articles to illustrate the variety of experiences, personalities, circumstances, geography, values, and incidents that define Utah history and make it so interesting.

OPPOSITE: "Dinner Scene of Platueau Cow Boys," a c. 1887photo. Sam Todd, number 13, participated in and wrote about the Soldier Crossing skirmish.

ON THE COVER: Tailor John I? Wright at work in his shop on Main Street in Murray. Wright exemplifies the small business owners who received electricity through the Progress Company. Note the fuse box and meter mounted above the window, the suspended incandescent lamp, and the electric pressing iron. He retained his foot-treadle sewing machine, however. Courtesy of Diana S. Johnson; all rights reserved.

An Immigrant Story: Three Orphaned Italians in Early Utah Territory

By MICHAEL W. HOMER

By MICHAEL W. HOMER

w

illiam Mulder, a distinguished immigration historian, wrote almost fifty years ago that the immigrant story is "a source of history still unexplored, not only in Utah but in the United States at large. It is a hidden literature, a hidden history...it is a literature of the unlettered ...it is hidden in languages other than English [and] it is not in readily available form, often physically inaccessible."' More than twenty years later Mulder was still convinced that the immigrant voice remained hidden and that "in Mormon history this voice has been but faintly heard."2 Not much has changed since Mulder made these observations. Mulder, Helen Z. Papanikolas, Philip E Notarianni, and a few others have written about immigrants' experiences in Utah.3 But their voices are still Danieh and James only occasionally heard as "sources become (0' Jacques) Be*ochr Italian more elusive as each year passes."' immigrants to Utah.

Michael W. Homer is a trial lawyer living in Salt Lake City. A version of this paper was presented at the American Italian Historical Association meeting held in LasVegas in October 2001. The author wishes to thank Flora Ferrero, Mario DePillis, Matt Homer, Massimo Introvigne, and Philip E Notarianni for their comments, assistance, and inspiration.

' William Mulder, "Through Immigrant Eyes: Utah History at the Grass Roots," Utah Historical Quarterly 22 (1954):41,45.

William Mulder, "Mormon Angles of Historical Vision: Some Maverick Reflections," Journal of Mormon History 3 (1976): 13, 19.

See, for instance, William Mulder, Homeward to Zion (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1957);Helen Z. Papanikolas, ed., The Peoples of Utah (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1976).

Andrew E Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised (Norman:University of Oklahoma Press, 1968), 12.

Notarianni has been diligent in exposing the hidden stories of Italian Ameri~ans.~He has described the lives of Italians who immigrated to Utah Territory between the mid-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the time, Italy was overpopulated, offered few jobs for sued laborers, and was suffering massive crop failures. These Italians immigrated "with the ardent desire to shed their old world identity and be reborn to a new life.. . . They craved a new identity and a new life."6

In Utah, as in the West generally, Itahan immigrants were a "relatively small percentage of the total population" and "too few in number to change its culture radi~ally."~Although most Italians who immigrated to Utah during the nineteenth century came to chase the American dream in mines and on railroads, the first group of Itahans that settled in the territory were Mormon converts who left their ancestral homes near Turin between 1854 and 1855.* They came to Utah not only because they believed that Mormonism would enrich their lives and, according to Mormon doctrine, ensure that their families would remain intact after death, but also because, like most other immigrants, they desired to join a new economic brotherhood.

Mulder calls LDS converts' "break with the Old World.. .a compound fracture: a break with the old church and with the old co~ntry."~Even though they were prepared to live among and marry immigrants from other countries and cultures, it was not always easy for them to assimilate into Utah society. It took time for their fractures, the break with the old church and the old country, to heal. They had to overcome language, cultural, and religious differences. They had even more difficulty integrating into American society and realizing its promise of greater economic opportunities. Like most immigrants, they "faced years of hard work in order to save enough money to buy improved land or a going business."1° This process was even more difficult for converts who lost their parents, became orphans, and were sent to live in inhospitable places.

When Mormon missionaries arrived in Italy in June 1850, they began proselyting in Piedmont among the only indigenous Protestants on the

Among Notarianni's many articles concerning the Italian immigrant experience, see Philip F. Notarianni, "Italian Fraternal Organizations in Utah, 1897-1 934," Utah Historical Quarterly 43 (1975): 172-87; "Italianiti in Utah: The Immigrant Experience," in The Peoples of Utah, 303-31; "Utah's Ellis Island: The Diflicult 'Americanization' of Carbon County," Utah Historical Quarterly 47 (1979): 17-93; "Italian Involvement in the 1903-04 Coal Miners' Strike in Southern Colorado and Utah," in George E. Pozzetta, ed., Pane e Lavoro: The Italian American Working Class (Toronto: Multicultural History Society of Ontario, 1980), 47-65; and Philip E Notarianni and Richard Raspa, "The Italian Community of Helper, Utah: Its Historic and Folkloric Past and Present," in Richard N. Juliani, ed., The Family and Community LiJe of Italian Americans (NewYork: Italian American Historical Association, 1983),23-33.

Eric Hoffer, The Due Believer (reprint, NewYork: Time, 1964), 95-96.

Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised,9,333.

Missions opened by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon church) in England in 1837 and in France, Scandinavia, Italy, Switzerland, and Prussia in 1850-51 produced thousands of converts who immigrated to Utah before the end of the century; see Bruce A.Van Orden, Building Zion: The Latter-day Saints in Europe (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Company, 1996).

Mulder, "Through Immigrant Eyes," 47; Mulder, "Mormon Angles of HistoricalVision," 20.

'O Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised, 10.

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

Italian peninsula. The Waldensians were descendants of lay Catholic reformers who resided in Lyon, France, during the late twelfth century. These reformers lived in poverty and dedicated their lives to be witnesses for Christ, even though they were not compensated and had not received ecclesiastical approval. When their local bishop instructed them to stop preaching they refused; thereafter, the church excommunicated them and included them in its list of heretics. Not surprisingly, the group became increasingly distrustful of church authorities and began to regard themselves bound together in a separate religious community. Beginning in the thirteenth century they were driven from their urban venues and experienced a diaspora. They relocated not only in Piedmont but also in Provence, Dauphin&,Bohemia, and even in southern Italy (Calabria and Apulia). The Waldensians lived in isolated communities in each of these locations. They developed an underground culture, distinctive doctrines, and heretical rituals. In 1532 the Waldensians aligned themselves with Protestants in Switzerland and mohfied many of their historical doctrines and rituals. Thereafter they were part of a much larger target, and for the next two hundred years they were severely persecuted. Although the Reformation provided the catalyst for bringing the Waldensians in Piedmont out of their isolation, it resulted in their extinction in Germany, France, and southern Italy. They survived in Piedmont only because of their remote mountain location.

After the Waldensians aligned themselves with the Reformed Church in Switzerland, their pastors began emphasizing their pre-Reformation origins and they were increasingly convinced that, because of their history of persecution, they were a chosen people.They also claimed that they couldtrace their origins to the primitive church because of "some idealized hypothetical antecedents of the reformed church." Although there is no reliable evidence that the Waldensians originated before the twelfth century, their history is full of examples of "real people who had suffered persecution in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries in the Alps."" Waldensians were forced to seek exile, to hide in caves, to repulse attacking government forces, and to heave large boulders from mountainsides at soldiers who advanced up their narrow valleys to destroy their villages.12

" See Euan Cameron, The Reformation of the Heretics: The Waldensians of the Alps, 1480-1580 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1984), 237. Other recent studies ofwaldensian history include Giorgio Tourn, You Are My Witnesses:The Waldensians across 800 Ears (Torino: Claudiana, 1990); Prescott Stephens, The Waldensian Story:A Study in Faith, Intolerance and Survival (Lewes, Sussex: Book Guild Ltd., 1998); and Gabriel Audisio, The Waldensian Dissent, Persecution and Survival, c. 1 1 70-c. 1570 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999).

"The most famous caverns used by Piedmontese Waldensians for refuge during persecutions in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were Gheisa d'la tana, located near Chanforan in the Angrogna valley, and the Bars de la Tagliola, located at the foot of the Rock of Casteluzzo. See GianVittorio Avondo and Franco Bellion, LE KlEi Pellice e Germanasca (Cuneo: L'Arciere, 1989), 102-103. See also Edward Finden, The Illustvations of the Kudois in a Series of Views (London: Charles Tilt, 1831), 31-32; and Ebenezer Henderson, The Vaudois: Comprising Observations Made during a Tour to the Valley of Piedmont, in the Summer of 1 844 (London: Snow, 1845), 115-1 6.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Protestant missionaries embraced the Waldensians to foster their own agendas. Anglicans believed that Waldensian claims to apostolic origins provided all Protestants a church through which they could trace an untainted priesthood back to the primitive church. Reformed Protestants, including the Calvinists in Switzerland and the Presbyterians in England, believed that Waldensian doctrines and rituals proved that their own reformed theology was closer to primitive Christianity than Catholicism was. Other churches, including the so-called American churches-Mormons, Adventists, and Bible Students-were convinced that the

Waldensians' history of persecution, their

LDS elder refusal to submit to papal authority, and many of their doctrines and practices demonstrated

that an apostasy had taken place and that the

Waldensians had preserved many pure doctrines of the primitive church.

this

Mormon missionary Lorenzo Snow believed that the Waldensians were "like the rose in the wilderness" and that their history of persecution had prepared them for his message." During the nineteenth century some Waldensians dissented &om their own church because they believed it had abandoned its historic mission to preach the primitive gospel. Some of these dissenters were later attracted by Snow's message. Although the group was no longer persecuted, its members lived poor and isolated lives. Mormon missionaries were struck by the extreme poverty and crowded conditions of their valleys. Hundreds ofwaldensians, out of a total population of only 20,000, were leaving their ancestral homes each year, not to escape religious persecution but to search for greater economic opportunities. Despite appalling economic conditions, the Waldensian leadership was reluctant to organize or endorse any program of emigration because it feared that members would eventually abandon their cultural and ethnic heritage if they left the valleys.

Snow made several promises to encourage Waldensian investigators to join his church and emigrate to Utah Territory. He reassured the persecution-weary Piedmontese that there was no "external, or internal danger" in Utah. He also pledged to them that "we all are rich-there is no real poverty, all men-have access to the soil, the pasture, the timber, the water power,

13For accounts of Lorenzo Snow's activities as an LDS missionary, see Lorenzo Snow, The Italian Mission (London:W.Aubrey, 1851), and Eliza R. Snow Smith, Biography and Family Record of Lorenxo Snow (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Co., 1884).

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

Engraving of the rock of

Luuo. From

peak,

Lorenzo Snow dedicated the

itafian

San Germano, Val Chisone, the home village of the Bertoch family.

and all the elements of wealth without money or price." Perhaps most important, he assured them that "many thousands [of] dollars have already been donated.. .to be increased to millions" for a Perpetual Emigrating Fund to assist the poor in emigrating." By the end of 1852, thirty-six persons had converted to Mormonism, and in 1853, the most successful year of the mission, fifty-three additional people chose baptism.'' Many of the converts were farmers who were experiencing increasing difficulties raising crops because of grape disease and potato rot.

In April 1853 the LDS First Presidency published its Ninth General Epistle, in which it instructed all church members to immigrate to Utah. In July the epistle appeared in the Millennia1 Star, which circulated throughout the European Mission.16The First Presidency reassured church members in Europe that the "Perpetual Emigrating Funds are in a prosperous condition," although "but a small portion is available for use this season." It also encouraged members to contribute to the fund to help "the Saints to come home.And let all who can, come without delay, and not wait to be helped by these funds, but leave them to help those who cannot help themselves.'' Finally the epistle encouraged widows to wait until they settled in Utah to be "sealed" to their dead husbands for eternity.

Jean Bertoch, a sixty-year-old farmer from San Germano Chisone, was among the fifty-three Waldensians converted in 1853. He was baptized by

l4 Lorenzo Snow, La Voix deJoseph (Torino: Ferrero et Franco, 1851), 73-74.This pamphlet was translated into English, in abbreviated form, the following year; see Lorenzo Snow, The Voice ofJoseph (Malta: n.p., 1852), 18.

l5 Concerning the Italian Mission, see Michael W. Homer, "The Italian Mission, 1850-1867," Sunstone 7 (1982): 16-21; Diane Stokoe, "The Mormon Waldensians," (M.A. thesis, Brigham Young University, December 1985); Michael W. Homer, "The Church's Image in Italy from the 1840s to 1946: A Bibliographic Essay," BYU Studies 31 (1991): 83-114; Michael W. Homer, "Gli Italiani e i Mormoni," Renovatio 26 (1991): 79-106; Michael W Homer, "LDS Prospects in Italy for the Twenty-first Century," Dia1ogue:AJournaE ofMormon Thought 29 (1996): 139-58; Flora Ferrero, L'emigrazione valdese nello Utah nella seconda metd del1'800 (Tesa di Laurea: Universiti di Torino, 1999); Michael W. Homer, "'Like the Rose in the Wilderness': The Mormon Mission in the Kingdom of Sardinia," Mormon Historical Studies 1 (2000), 25-62; Michael W. Homer, "L'azione missionaria in Italia e nelle Valli Valdesi dei gruppi Americani 'non tradizionali' (Awentisiti, Mormoni, Testimoni di Geova)" in La Bibbia, la Coccarda e il Eicolore. I Valdesi fra due emancipaxioni, 1798-1848, a cura di Gian Paolo Romagnani (Torino: Claudiana, 2001), 505-25; and Flora Ferrero, "Dalle Valli Valdesi a1 Grande Lago Salato: Un percorso di conversione," in La Bibbia, la Coccarda e il Tricolore, ibid., 531-38.

l6 Millennia1 Star 15 (1853): 436-41.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Jabez Woodard, a thirty-two-year-old gardener from Peckham, England, whom mission president Lorenzo Snow chose as his succe~sor.'~Jean and his wife Marguerite Bounous, who had died in 1840, had three sons and two daughters:Jean, Antoinette, Marguerite, Daniel, and Jacques. Jean was a landowner in the Val Chisone, where the family lived, farmed, went to school, and enjoyed some social connections. Even after his wife's death, Jean remained close to his in-laws. One brother-in-law, Jean Pierre Meynier, was the mayor of San Germano and an elder in the Waldensian church. Another brother-in-law, Daniel Vinson, was a dissenter who became alienated from the Waldensian church during a reawakening ("risvelgio") in the valleys that began during the 1830s.

Jean and his five children were baptized on August 3, and twenty days later Jean was ordained an elder. The church program of immigration, described in La Voix de Joseph and reemphasized in the Ninth General Epistle, resonated with Jean Bertoch. Within a few months of his conversion and ordination,Jean took steps that he hoped would enable him and his children to leave their overcrowded valleys in Piedmont and immigrate to Utah. Jean was probably also encouraged by assurances that when he arrived in Utah he could participate in rituals that would guarantee that his wife, who had died when Jacques was still a toddler, would be sealed in marriage to him for eternity. In October Jean paid 200 lire to the Kingdom of Sardinia to secure a military deferment for his eighteen-year-old son, Daniel. Without the deferment, Daniel would have been required to enlist in the army, and he could not have left Italy for at least another two years.''

In December 1853 Bertoch sold the family's two-story home (which was also designed to shelter livestock) and the adjoining cropland, located on steep mountainsides above San Germano Chisone. Notwithstanding massive crop failures and depressed economic conditions, Bertoch sold his residence to Gioanna Bertalot for 2,200 lire, which was about the same amount he had invested in the property.19 In January 1854 Bertoch sold another field he used for farming farther upVal Chisone, in Pomaretto, for 300 lire.20Contemporary notarial records demonstrate that during the 1850s farmers continued to buy and sell property and that most departing Mormon converts could dispose of their properties for reasonable prices.

Shortly after Jean sold his properties, Mormon converts began preparing to leave Piedmont and take their long journey to Utah. Although Jean wanted to emigrate with his children,Jabez Woodard asked him to remain in Italy to preside over a third church branch, which was organized in San Germano on January 7, 1854.21Jean could have paid for his children's trip

l7 Concerning Jabez Woodard, see Jabez Woodard Journal, LDS Archives, Salt Lake City.

l8 Registro delle Insinuazioni di Pinerolo, 1853, vol. 1046,425-26,Archivio di Stato di Torino.

l9 Registro delle Insinuazioni di Pinerolo, 1854, vol. 1049,477-78,Archivio di Stato diTorino.

*'Registro delle Insinuazioni di San Secondo, 1854, vol. 562,157-59,Archivio di Stato di Torino.

21 Millennia1 Stay, 16 (1854):61-62.

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

Torre Pellice, where the immigrant Waldensians boarded coaches to cross the Alps.

by using the money he received when he sold his land, but he was asked to donate a portion of the proceeds to the LDS church to sustain the Italian

Mission. Converts from each of the mission's three branches received assistance from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, so that no single branch would be favored over another and, perhaps most important, to ensure that the membership of no single branch would be dramatically depleted by emigration. The first group of emigrants included Barthslemy and Marianne Pons and their three children (representing the Angrogna Branch), and Philippe and Marie Cardon and their six children (representing the Saint-Barthdemy). Jean's children represented the San Germano Branch-Jean, age twenty-six; Antoinette, twenty-three; Marguerite, twenty-one; Daniel, eighteen; and Jacques, fifteen. Jabez Woodard planned to accompany the converts to England, meet his wife and three children there, and then continue to America. Jean was therefore confident that his children would be safe during the long journey to America. He sent them with the partial assistance of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund and promised them that he would join them in their new homeland the following year.

On February 8, 1854, twenty converts met in Torre Pellice to board coaches that eventually took them to Susa, a small village located at the foot of the Alps. In Susa they hired diligences, which were placed on skids and drawn by mules, to carry them up the steep Mt. Cenis Pass and across the Alps to France. After the converts had successfully crossed the Alps, the diligences were placed on wooden wheels and the group continued to Lyon, where they caught a train to Paris, and from there to Calais. In Calais they boarded a steamer that transported them to the British coast, where they took trains to London and then to Liverpool. On March 12 they boarded the John M. Wood, which crossed the Atlantic Ocean with 397 Mormon converts from England, Denmark, France, and Italy. On May 2, 1854, the first group of Mormon converts fiom Italy arrived in New Orleans.

On May 3 they boarded thejosiasiah Lawrence, a steamboat that transported them up the Mississippi to St. Louis. On May 14, shortly before arriving in St. Louis, most of the church members were detained on Arsenal Island, which in 1849 had become an inspection site and a quarantined area where immigrants were examined for cholera. On the morning theJosiah Lawrence arrived in quarantine, the Bertoch family suffered a tragic loss. Marguerite,

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

FROM WILLIAM BEATTIE. THE WALDENSES (LONDON. GEORGE VIRTUE 1838)

who had celebrated her twenty-first birthday shortly before leaving Italy, died of cholera in the arms of Philippe Cardon7s daughters. Eleven other converts died within a few hours and were buried with Marguerite on the island. Daniel Bertoch later called her death "one of [the] first hard trial[s] that I had to pass

When they were released from quarantine, the surviving Bertoch children started on the route that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had followed fifty years earlier in their epic journey across the American continent. The converts boarded steamships that conveyed them up the Missouri River to Westport, Missouri. Near Westport they camped at Prairie Camp, a Mormon staging area, where they prepared for the difficult overland journey across the Great Plains. While outfitting for the westward trek, Daniel took lessons "in breaking whiled fatt steers never befor having had any expirians with any kattle."23The converts remained at the staging area for several months before starting their trek to Utah during the third week in July. Daniel was assigned to the Robert L. Campbell company,24 while his siblings Jean, Jacques, and Antoinette traveled with the William A. Empey company. The companies traveled about ten miles per day during their westward trek.

While traveling across the Great Plains the companies banded their 150 wagons together when they saw Native Americans in the area. But they encountered greater dangers than Indians. Daniel remembered that "our cattle never unyoked until we were out of buffalo country.We would camp early enough to feed the cattle before dark.. .. One night we had a stampede.The whole plain trembled and shook under the weight of 125 yoke of cattle running madly over the plains. In the morning we found them two or three miles from the camp. They were all together and we did not lose one." But although they successfully recovered cattle, they lost additional converts. round the third week of ~u~ust,while camping near Fort Kearny, Nebraska Territory, the Bertoch children were stunned when their oldest brother, Jean, died of pneumonia. BarthGlemy Pons, the father of three small children, also died about the same time.25There were other close calls for the surviving Bertoch siblings. In rnid-September, near Fort Laramie, Jacques fell from a wagon and the wheels ran over his legs. Although the boy recovered, he and his sister entered the Salt LakeValley on October 26, two days afier their company's forty-three wagons arrived,

22Biographyof Daniel Bertoch (c. 1919), copy in possession of author.There are two variations: a manuscript written in Bertoch's handwriting and a typescript written in third person. The second variant contains details that were presumably recorded from stories told by Bertoch himself. Unless otherwise noted, material about Daniel comes from this source.

23 Ibid.

24RobertL. Campbell was a twenty-nine-year-old Scottish convert from Glasgow. He was also the president of the company of LDS emigrants aboard theJohn M. Wood.

25Biographyof Daniel Bertoch. Some family accounts also claim that Jean Bertoch, Jr., was injured during the trans-oceanic journey when he fell through a hatch on the ship but that he had recovered by the time he reached New Orleans.

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

because they had wandered away from the company and become lost in the mountain^.'^ Daniel's company entered the valley on October 28. It had taken the first group of Italian immigrants nine and one-half months after leaving Torre Pellice to reach Salt Lake City.

When Jacques and Antoinette arrived in Salt Lake they were introduced to Joseph Toronto, who took them to his residence on First Avenue to wait for Daniel. Daniel spent his first night in the city in a shelter "made back of a dirt wall, just north ofJohn Sharp's dwelling."The next day Daniel met Toronto, who "took me paniel] to his house where I met my brother and sister."27The Bertoch

Joseph Toronto. children were among many immigrants who spent a few days in Toronto's home before being sent to a settlement in the territory. Toronto was a thirty-six-year-old convert from Sicily who had met Brigham Young in 1845 and donated $2,600 in gold to the church.Three years later, he helped driveYoung9scattle across the plains. In 1849 Young asked Toronto to travel to Italy with Lorenzo Snow to help organize the LDS mission. When Toronto returned to Utah in July 1852 he lived with Young-and even became known as "JosephYoung"-until he married a Welsh convert and built his own home on First Avenue. His residence thereafter became a halfivay house for many newly arrived imrnigrant~.'~

Brigham Young asked Toronto to supervise the Bertoches because they were not accompanied by their father. The siblings were relatively young, did not speak English, and shared an Italian connection with Toronto. Even though Toronto did not speak French, the Waldensians' primary language, he spoke Italian, which was their second language. Unlike later Italian immigrants, the converts from Piedmont did not settle together in the same communities-The Pons, Cardon, and Bertoch families were sent to separate settlements along the Wasatch Front, and, with few exceptions, they did not see each other again.

Young had assigned Toronto the task of caring for his cattle herd on the Great Salt Lake's Antelope Island. The United States Army Topographical

26AndrewJenson, Latter-Day Saints Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Co., 1901-1936), 2:462.

27 Biography of Daniel Bertoch.

28 Concerning Joseph Toronto, see James A. Toronto, "Giuseppe Efisio Taranto: Odyssey from Sicily to Salt Lake City," in Bruce A.Van Orden, D. Brent Smith, and Everett Smith,Jr., eds., Pioneers in Every Land (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1997), 125-47, and Joseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch (Farmington, Utah: Toronto Family Organization, 1983).

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Engineers, commanded by John C. Fremont and including Fremont's guide and confidante Kit Carson, had first explored the lake in September 1843.29 When Frkmont and Carson returned to the Great Salt Lake in October 1845 they explored and named Antelope I~land.~'Frkmont's accounts influenced Brigham Young's decision to settle in Salt Lake Valley and to use Antelope Island for grazing. In 1848 Young sent Lot Smith, Heber P. Kimball, and Fielding Garr to explore the island and confirm whether it was suitable for grazing. During the fd of that year, several church members set up ranches on the island and drove their cattle over the sandbar that connected it with the mainland. In 1849Young asked Garr to be his on-site foreman and to care for church cattle and other livestock on the island. In the fall of that year Garr moved church cattle to the island and built a corral and an adobe ranch house-known as "the old church housew-as a residence for his family3*In April 1850 the Topographical Engineers, under the command of Howard Stansbury, conducted a more complete exploration of the lake. Some of Stansbury's company reached the eastern shore of Antelope Island, "passing over a sandbar which unites it with the mainland," but Stansbury landed on the island "[alfter a heavy row of six hours" from the mouth of the Jordan River. The company drove its livestock from the mainland across the sandbar to the island and "placed them under the charge of the herdsman [Fielding Garr] licensed by the Mormon authorities" because the eastern slope of the island was "one of the finest ranges for horses and cattle to be found in the whole valley." Stansbury camped near springs located approximately five miles north of the land bridge while he surveyed the lake.32In September 1850 the legislature of the State of Deseret "reserved and appropriated [Antelope and Stansbury islands] for the exclusive use and benefit of [the Perpetual Emigrating] Company, for the keeping of stock." Thereafter, Antelope Island also became known as Church Island because the cattle, sheep, and horses that immigrants used to repay their debts to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund were kept on the island."

29 John C. Frkmont, Report of the Exploring Expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the Year 1842, and to Oregon and North Calfofovniain the years 1843-'44 (Washington,D.C.,: Gales and Seaton, 1845), 152-57. On September 9,1843, Frimont and his company took boats down the Bear River and paddled on the Great Salt Lake to Disappointment Island, which Howard Stansbury later renamed Fremont Island. While on the island, FrCmont speculated that both Antelope and Stansbury islands were "connected by flats and low ridges with the mountains in the rear" but left a "more complete delineation for a future survey."

30 Milo Milton Quaife, ed., Kit Carson'sAutobiography (Lincoln:University of Nebraska Press, 1966),89.

"Dale L. Morgan, The Great Salt Lake (reprint, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1995), 252. The house, kept in use as a ranch house until 1981, is Utah's oldest Anglo-built house still on its original foundation.

32Ho~ardStansbury, Exploration and Survey of the klley of the Great Salt Lake of Utah, including a Reconnaissance of a New Route through the Rocky Mountains (Philadelphia:Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1852), 156-65.

33Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 251-53. Morgan writes that, although the island was technically reserved for the Perpetual Emigrating Company, some church leaders also used it for their own stock; "cattle and horses were the essential medium of exchange, for many of the Saints saw no cash from one year's end to the next."

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The three surviving Bertoches went "to Antelope Island to work for President Young, under the direction of Mr. Toronto," four years after Stansbury completed his survey.34Those who had borrowed from the Perpetual Emigrating Fund often repaid the church by working on public works projects, and the young Bertoches were expected to labor in "redemption servitude" to repay their loan while they waited for their father.35The three did not reside at Fielding Garr's ranch but lived in a rustic shelter built by Toronto.

The first winter on the island was difficult. The Bertoch siblings spoke only a few words of English and they could not communicate with anyone on the island. The boys had the duty of walking around the island every day to check the location of cattle while Antoinette remained in the cabin to perform domestic chores. Toronto brought supplies every two weeks. The three survived on flour, bran, cornmeal, squash, and "bunch grass to chew on." Daniel reminisced, "I had to go to the canyon every day for wood, which resulted in wet feet. For my shoes were so bad that I was obliged to tie them on with strings.'' He remembered, in a letter to Jacques, "our early days in Utah especially on the Church Island when we eat that big Ox.. .. Toronto said the Grando Bovo will Die we better kill him and eat him oh how toff he was I would had good teeth yet if it hadn't been for eating of that Ox and-many other things we did eat makes me sick to think about it now."36

The Bertoch siblings did not record many of their experiences on Antelope Island. Like most immigrants they were "unlettered," and they probably felt that most of their daily activities were not significant enough to record for posterity. But as Wilham Mulder has observed, "The history of

35 The Perpetual Emigrating Fund Ledger confirms that the Bertoch family was initially indebted to the Perpetual Emigrating Company "for the cost of transportation of family from Liverpool to Salt Lake City" in the amount of $296.50.This was reduced by "cash paid on a/c of passages" in the amount of $169.75, leaving a balance "due the P.E.F. Co." of $126.75. Each of the five children was assessed $25.35, even though two of them died before arriving in Utah Territory. See PEF Ledger, LDS Church Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah. The Bertoch debt had been discharged when the list of those still indebted to the PEF was published in 1877; see Names of persons and suveties indebted to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company from 1850 to 1877 (Salt Lake City: Star Book and Job Printing Office, 1877), republished in Mormon Historical Studies 1 (Fall 2000), 141-42. For more on the PEF and indebtedness, see Scott Alan Carson, The Pevetual Emigrating Fund: Redemption Servitude and Subsidized Migration in America's Great Basin (Ph.D. diss., University of Utah, 1998). Carson notes that less than 2 percent of the immigrants who arrived in Utah during 1854-55 were farmers. The Bertoch children's obvious lack of skills meant that they needed supervision and were best suited for ranching activities.

36Biographyof James (Jacques) Bertoch (c. 1923), in possession of the author; biography of Daniel Bertoch; Daniel Bertoch to James Bertoch and Anne Cutcliff Bertoch, February 14, 1922, copy in possession of the author (emphasis added). Unless otherwise noted, material about Jacques comes from the biography of James Bertoch.

During the summer prior to the Bertoches' arrival, grasshoppers had destroyed much of the crops and grazing areas in the valley and on the island. As a result, in October church leaders moved most of their cattle from the island to new range near Utah Lake. In addition, during the summer of 1854 the Great Salt Lake reached its highest elevation since the Mormons had arrived. For the next five years it was impossible to use the sand bar to reach the island. See Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 254-55.

34 Biography of Daniel Bertoch.

Utah, as seen through immigrant eyes, is full of significant trifles.'' Daniel's holographic memoirs demonstrate the significance of such trifles. They demonstrate the difficulties that many immigrants experienced in adjusting to their new environment. Daniel wrote that in the spring of 1855

Toronto and myself started for Salt Lake with a piece of bran bread in our pockets. We were trying to find the head of the Jordan River. We came across a large flat boat filled with water, we stayed to empty it, but before our task was done it began to get dark, so we started for the nearest light. We stayed with Mr. Keits at K7s Creek. At breakfast I was seated next to a young lady about eighteen years old, dressed in a clean calico dress. Imagine my humiliation, for I was dressed in a greasy canvas, that Toronto brought from New Orleans. Next day we went back to complete our task and a terrible storm came making it imp~ssible.~'

This storm put Daniel and his companions "in danger of our lives.. .. Toronto called to us to come into the boat, and we began to pray in English. When we finished he called on a Danish boy, and he prayed in Danish; then he asked me. I prayed in French for the first time without my prayer book. It wasn't very long before the storm quieted down and we got away safely." These experiences, which Daniel remembered throughout his life, persuaded him to leave Antelope Island. "The next day we started in quest of the Jordan River, we found it in the late afternoon. We got in our boat and traveled up the river, we camped that night at Bakers. The next day we arrived in Salt Lake and went to Toronto's. I stayed with him long enough to get a pair of shoes then I ran away."38

Daniel found Salt Lake City much busier than Antelope Island.When he realized the church was constructing a temple there he decided that he would rather help dig its foundations than continue to live and work on the island. He labored at the temple block for about six weeks before John Sharp hired him to help dig a canal from Big Cottonwood Canyon to the mouth of City Creek Canyon. Sharp furnished Daniel and his fellow workers a weekly ration of "1/2 pounds of shorts [bran and other by-products of milling], 1-1/2 pounds of flour and meat the size of a mans two fists." In the fall Daniel "went to Sharp for my money, he told me there was no money, only what we ate."39

~aniel-was left "peeniless and without a place to stay," but he was even more distraught when he was told that same day, by a company of Mormon immigrants, that his father was dead and had been buried in Mormon Grove, Kansas. Jean Bertoch had left Italy in February 1855 with the second group of Mormon converts.40After the first group had depart-

38 Biography of Daniel Bertoch.

39 Ibid.

1bid.The second group ofwaldensian emigrants included members of the Malan and Bonnet families from the Angrogna Branch; and Bertoch from the San Germano Branch. The third and last group of Italian converts left Piedmont in the fall of 1855. It included Madeleine Malan from the Angrogna Branch; members of the Rochon, Chatelain, and Beus families hom the San Germano Branch; and the Gaudin

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

37 Mulder, "Mormon Angles of HistoricalVision," 55; biography of Daniel Bertoch. Large flat-bottomed boats were used to transfer stock between the mainland and the island.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

ed, new convert baptisms had failed to keep pace with the number of members who wanted to immigrate to Utah, probably because Waldensian pastors became more aggressive in their opposition to Mormon missionaries. The Waldensian church also began to discuss and formulate its own program of emigration, which would eventually lead to the establishment of Waldensian communities in North and South Ameri~a.~~During the same year, the Perpetual Emigrating Fund became increasingly strained, the church became "more selective with respect to the type of migrants it assisted,"" and some Waldensians, especially those who were unskilled, found it difficult to leave for America as soon as they would have liked. Some of these returned to the Waldensian church and later settled in other locations.

Jean Bertoch and fourteen other Italian converts probably followed most of the route his children had used one year earlier to journey from their ancestral villages to Liverpool. Bertoch and his group did travel to Susa in a little more comfort than the previous group had because the Kingdom of Sardinia completed its rail lines from Pinerolo to Turin in June 1854 and from Turin to Susa in May 1854.43On March 31, 1855, they boarded the ship Juventa in Liverpool. It arrived in Philadelphia on May 5 without suffering any losses. The LDS hierarchy had selected Philadelphia as its point of entry to save both the time and the lives that were often lost when converts arrived in New Orleans. From Philadelphia the Italians traveled by rail as far as Pittsburgh, where they boarded Ohio River steamships to St. Louis. There they boarded steamships that transported them up the Missouri River to Atchison, Kansas, located five miles from Mormon Grove, where they outfitted for the westward trek. During the spring and summer of 1855 "nearly 2,000 Latter-day Saints with 337 wagons" left Mormon Grove for the Great Basin. Unfortunately, many converts, including Bertoch, died of cholera in Mormon Grove and were buried in unmarked graves near the ~ampground.~~

Daniel was stunned by his father's death, which, ironically, occurred about the same time he ran away from Antelope Island. He decided to swallow his pride and return to the island to rejoin Jacques and Antoinette. "My brother and sister were living on the island. I felt pretty blue and alone in the world. Having run away fromToronto I hated to go back, but I did and he took me back on the island in the fall of 1855." But Daniel

family from the Saint-Barthdemy Branch.This group boarded the john]. Boyd in Liverpool on December 12, 1855, and arrived in New York City on February 16, 1856. See "Emigration Records and Ship Roster,,' LDS Church Archives.

41 See George B. Watts, The Waldenses in the New World (Durham: Duke University Press, 1941).There were twenty-seven LDS baptisms among the Waldensians in 1854, another twenty-six in 1855, and only eight in 1856; see "Record of the Italian Mission," LDS Church Archives.

42 Carson, The Perpetual Emkrating Fund, 448.

43L~igiBallatore, Storia delle ferrovie in Piemonte, dalle origini alla vigilia della seconda guerra mondiale (Torino: Biblioteca Economia, 1996),27-37,101-103.

44 Stanley B. Gmball, Historic Sites and Markers along the Mormon and Other Great Western mils (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 131-32.

nearly perished in a storm as he journeyed back to the island. "While in the lake a dreadful storm started. I was drifted all over and thought any minute I would be tipped over and drowned. I was very frightened so I prayed and then trusted the Lord. I was carried safely to the island and stayed at the church [probably Fielding Garr's ranch] that night. The next day I went on to my brother and sister."" When the three siblings reunited, they realized that they would have to survive in Utah without their father.

Jean Bertoch's death perhaps accelerated his children's assimilation into Mormon society. During the summer of 1855 grasshoppers devastated the valley and the island even more severely than they had the previous year. The winter provided no relief. Daniel later wrote that "the winter of '55 and '56 was a hard one. The spring of 1856 was one of the hardest that the people had to pass through. Many a family had to sit down to the table and ask the blessing on the food and there was nothing but a dish of greens to be seen."46In the midst of these hardships Antoinette left the island in February 1856 to marry Louis Chapuis, a twenty-nine-year-old Frenchspeaking convert from Lausanne, Switzerland. Chapuis had met and befriended the French-speaking Bertoches two years earlier aboard theJohn M. Wood. Antoinette and her husband eventually settled in Nephi and raised four children. Her brothers had more difficulty finding patrons. But they did cultivate relationships with surrogate fathers closely connected to the church hierarchy, who promised them food and shelter in exchange for work. In the fall of 1856 Daniel "started to work for George D. and Jedediah Grant" at Mound Fort, one of four forts built during the 1850s within the present city limits of Ogden. His patrons were at the center of the Mormon Reformation, and Daniel was rebaptized in the Ogden River.

Only Jacques, now eighteen, remained with Joseph Toronto. He moved from the island to Point of West Mountains (near Garfield) when Toronto, seeing that grazing conditions were better near the shore of the lake, decided to relocate his personal ranch.47In 1854 the territorial legislature had begun issuing grazing rights, not only on the islands of the Great Salt Lake but also on the lake shore from Tooele to the mouth of the Jordan River. Good grazing lands were becoming increasingly scarce because of grasshoppers and severe weather. Jacques became the foreman of the new ranch and began using "Jack Toronto" as his nickname. He lived in a oneroom rock building that he and Toronto constructed, and he used an oblong cavern known as Toronto's Cave as an additional shelter and barn.48

Like most Mormons, Daniel and Jack were seized by the events that

45Biographyof Daniel Bertoch. The Garr ranch was owned by the LDS church, and the ranch house was called the "old church house"; see Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 252.

46 Biography of Daniel Bertoch. For more on the grasshoppers, see Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 255.

47 Biography of Daniel Bertoch. Point ofWest Mountains eventually became known as Pleasant Green; see Francis W. Kirkham and Harold Lundstrom, eds., Tales of a Triumphant People: A History of Salt Lake County, Utah, 1847-2900 (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers of Salt Lake County Company, 1947).

48 Morgan, The Great Salt Lake, 256; Kirkham and Lundstrom, eds., Tales of a Triumphant People, 271-72;

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

The author and his son Matt in front of Toronto's Cave, where Jacques (James) Berfoch lived for a time.

briefly disrupted the territory during the winter of 1857-58. Despite assurances made in La Voix de Joseph that there were no internal -. * or external dangers In Utah, the United States Army began marching toward the territory during the summer of 1857. Brigham Young saw striking similarities between Waldensian history and the situation in Utah Territory, and he reminded church members that the Waldensians had shown courage and perseverance in defending their valleys and he encouraged his followers to do likewise. In the fd of 1857 Jack accompanied Toronto to Echo Canyon, where, as his ancestors had, he helped prepare his church's resistance to government troops. With more than two thousand other volunteers, he dug trenches across Echo Canyon, and on the has overloohng the canyon he loosened rocks that could be hurled down at the soldiers.49

Because of the oncoming federal troops, the following spring Daniel accompanied George D. Grant (Jedediah M. Grant had died the previous December), and other Mormons to the Provo River bottoms, where they remained for two months while the army passed through Salt Lake City. After the Utah War, Daniel returned to Ogden, but shortly thereafter he moved with his patrons to a ranch located near Littleton in Morgan County. Jack returned to Point of West Mountains and resumed his duties as ranch foreman.

For the next ten years Daniel and Jack gradually assimilated into Mormon society. They learned to speak English, worked for their patrons, attended church, and married young British converts who had recently arrived in the territory. In 1866 Daniel married seventeen-year-old Elva Hampton, who gave birth to four children before she died in 1874. Following her death he married another British convert, eighteen-year-old

Joseph Toronto, 23. Toronto's Cave is also known as Deadman's Cave because of archaeological artifacts, now deposited at the University of Utah, that were found there. In 1874 Louis Laurent Simonin, a French traveler, visited a cave near the Great Salt Lake (it is unclear, however, whether this was Toronto's Cave) where Indian artifacts had been found. Simonin was shocked to discover that one of two skulls found in the cave was being used for productions of Hamlet at the Salt Lake Theatre. He was able to obtain the skulls from Charles Savage and George Ottinger, and he gifted them to the Paris Museum. See Louis Laurent Simonin, A travers les Etats-Unis, de I'Atlantique au Pac$que (Paris: Charpentier et cie., 1875), 121-23.

19BrighamYoung, "Present and Former Persecutions of the Saints, Etc.," in Brigham Young et al., Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool: 1855-86), 5:342.Jacques had undoubtedly heard stories about his Waldensian ancestors who harassed troops loyal to the House of Savoy from cliffs above the road at Chiot dl'Aiga in theVal Angrogna while the troops were marching up the valley to their settlements at Pra del Torno; see Avondo and Bellion, Le mlli Pellice e Germanasca, 99-100.

James Bertoch with his wife

Ann C. Bertoch, six-month-old daughter Ann Elizabeth, and mother-in-law Elizabeth Hill Jones Cutcliffe in 1867.

Sarah Ann Richards, who bore five more children. In 1866 Jack, who by this time preferred the name James, married nineteen-year-old Ann C~tcliffe.~~ She eventually gave birth to thirteen children. Even after they married and began raising children, Daniel and James, who in 1866 were thirtyone and twenty-eight, continued to work for their patrons in exchange for subsistence in kind. Although they wanted to own their own farms, neither could afford to purchase property because their patrons did not pay wages. As long as they continued to work for room and board they did not have any realistic prospect of achieving economic independence or of enjoying "access to the soil, the pasture, the timber, the water power, and all the elements of wealth," as promised in La Voix de Joseph.

When the Civil War-time Congress passed the Homestead Act in 1862, Daniel and James finally would be given an opportunity to achieve their dream of farming their own land. The Homestead Act empowered settlers who had no economic resources to obtain free land. Immigrants who had filed a declaration to become U.S. citizens could apply for patents-legal title-for as much as 160 acres of surveyed land. Applications would be approved if homesteaders could demonstrate that they had improved the land-plowed, raised crops, put up fences, dug wells, constructed ditches, built homes-and lived there for at least five years. Before passage of the Homestead Act, it was not unusual for local church leaders to distribute farmland to families who were called to settle in specific communities. These distributions were not recognized as legal conveyances until the

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

50 Biography of James Bertoch. According to some family accounts James helped sponsor Ann's ernigration by contributing to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund. The same sources repeat family stories that James helped rescue her company when it arrived late in November and was snowbound in the mountains.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

United States Land Office confirmed them, however. Since the Land Office was not established in Utah until after the completion of the transcontinental railroad, territorial residents could not take advantage of the benefits of the Homestead Act until 1869."

Both Daniel and James applied for homesteads almost twenty years after they arrived in the territory, on land where they had labored for patrons all of their adult lives. On October 22, 1873, Daniel filed an application for a homestead of eighty acres located in the vicinity of Littleton, Morgan County. Daniel had lived and worked in Morgan County for the Grant family since 1860. In his application he noted that he had made improvements to the land since 1862.James Ned his application for a homestead of 79.8 acres on June 20, 1874.52His homestead was located near the Toronto ranch in Point of West Mountains, also called Pleasant Green. He had worked there since 1856, and he had lived there with his wife and children for eight years. James built a house and planted crops and fruit trees on the gentle slope of the mountain that rose above the highway that ran from Salt Lake City to Tooele. The United States Land Office granted Daniel title to his homestead on October 1, 1879, and to James on March 30, 1881, afier it approved the final proofs that confirmed they had complied with all of the requirements of the Homestead Act, including U.S. ~itizenship.~~ The brothers had not applied for citizenship until they-realized they had to be U.S. citizens in order to obtain land patents under the Homestead They had lived in Utah Territory for more than twenty-five years before they became citizens and obtained their own property."

The experiences of the Bertoch children demonstrate that converts who assimilated into Mormon society sometimes found it more difficult to integrate into the American economic system. The siblings emigrated from a

51Le~nard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 183G1900 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 90-93, 249-50. Concerning the Homestead Act, see Benjamin Horace Hibbard, A History ofthe Public Land Policies, 2d ed. (Madison and Milwaukee: University ofWisconsin Press, 1965),347-85.

''Shortly afier James applied for his homestead, Joseph Toronto returned to Italy. He spent one and one-half years in Palermo during 1876-77, successfully converting fourteen friends and relatives who returned to Utah with him in 1877; seeJoseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch, 25-26.

53DanielBertoch filed his Application for Patent on October 22, 1873 and his Final Proof on April 5, 1879. His Application for Patent was approved on July 1, 1879. James Bertoch filed his Application for Patent on June 20, 1874, and he filed his Final Proof on October 16,1880. His Application for Patent was approved on February 12, 1881. See Homestead File 1088 (Daniel Bertoch) and Homestead File 1359 (JamesBertoch) ,National Archives, Old Military and Civil Records Branch,Washington, D.C.

54 In 1873 and 1874 Daniel and James signed affidavits filed in connection with their applications for homestead patents, in which they stated that they were United States citizens. Actually, Daniel did not become a naturalized citizen until April 28, 1879, while James did not obtain citizenship until May 4, 1878. Each brother applied for citizenship because it was a requirement under the Homestead Act. See Daniel Bertoch and James Bertoch Homestead Files, National Archives.

55 An Italian newspaper reporter interviewed some of the family members converted by James Toronto during the same year James was granted title to his homestead.They were apparently not as patient as the Bertoch brothers. They told the reporter that they were disillusioned with Utah and that they wanted to return to Italy. See L'Eco d'ltalia, January 8, 1881. Eventually, one family did return to Sicily and another moved to California. SeeJoseph Toronto: Italian Pioneer and Patriarch, 26.

small and isolated community in Piedmont where they had lived as part of a family unit and a religious community. They experienced a test of their cultural identity when they lost two siblings, were separated from other Italian immigrants, and lost their father. During their first two years in the territory the Bertoches were detached from society because they understood only the rudiments of English and probably even less about their newly adopted religion. Antoinette and Jacques lived in virtual isolation from Mormon society on Antelope Island. Although Daniel worked for the church in Salt Lake City during the spring and summer of 1855, he also spent most of his time on the island. Initially, the Bertoches did not assirnilate into Mormon society because they retained their cultural distinctiveness in their tiny community of three people. They continued to speak French, they prayed from their prayer books, and they remained essentially a Waldensian family.

When the children left the island, separated, and gradually began losing their cultural distinctiveness, their eventual assimilation into Mormon society was assured.They no longer had daily association with persons who shared their language and customs.They began to associate with others and eventually married converts from other nationalities and cultures. They raised English-speaking children, participated in multi-cultural church meetings, and were called to church positions. But their assimilation into Mormon society did not result in their automatic integration into American society, the object of virtually every convert from Europe. Daniel and James did not achieve this second level of assimilation until Utah began its own gradual integration into the national economy and they obtained land through the Homestead Act. Thereafter, they no longer had to depend upon patrons, and they became participants in the barter system that was common in the territory. They owned land, homes, and livestock, worked as farmers, and served on boards of schools and water c~mpanies.~~

New waves of Catholic Italian immigrants to Utah at the end of the century also overcame immense obstacles as they oriented themselves to their new environment and as they struggled to enjoy the benefits of the American economy. It was usually even more difficult for them to find acceptance in some social circles because of their religious differences. But

56 In 1892 James returned to the Waldensian valleys as a Mormon missionary. Perhaps the example of Joseph Toronto, his surrogate father, who returned to Italy twice during his adult life and returned to Utah each time with relatives, was compelling for the fifty-three-year-old farmer. James and his mission companion lived in San Germano Chisone for nine months. In San Germano James was reunited with his cousins, who were prominent citizens in their small mountain town. He visited the family home that his father sold in 1854."The first day [I was in the valleys] I visited Monsieur Meynier and family, my cousins, and was well received, then I was accompanied by my cousin Meynier to my Father's place or what used to be his home which caused many a strange thoughts and feelings upon my mind, the house has not been occupied since it was sold in the year 1854.The house is in a good preserved condition, with the exception of the wood work on the outside"; mission journal of James Bertoch, June 30,1892, copy in possession of author. James corresponded with the Toronto family during his mission but, unlike his former patron, he did not convert any of his cousins. Nevertheless, a number ofwaldensians did emigrate to Utah during the same decade. See Watts, The Waldenses in the New World, 229-32.

AN IMMIGRANT STORY

they also confronted many of the same obstacles that had challenged Daniel and Jacques in their quest to achieve the American dream. They were few in number, did not speak English, and lacked economic resources. Some worked for the railroad; others became farmers or miners. They lived in temporary settlements in rudimentary shelters (shacks and boxcars instead of caves), gathered to worship, and struggled to preserve their cultural identity in a land where a hostile majority often ridiculed them. Since their numbers were small they eventually associated with, lived among, and married into the larger society. In the process they began to lose some of their cultural distinctiveness. Federal laws enacted to protect the rights of workers helped improve their lives as much as the Homestead Act had helped to liberate earlier immigrants.

When James retired in 1905, he sold his homestead, which he had farmed since 1874, to J. M. Anderson, an undisclosed agent for the Utah Copper Company, a New Jersey corporation, for $6,500. Other property owners in the area, including one of Joseph Toronto's sons, also sold property to the same agent.57After Anderson quit-claimed his newly acquired interests to the Utah Copper Company, the company began to employ some of this new wave of Italian immigrants on the same property where Bertoch had lived and worked for more than fifty years. Like Bertoch, some of these Italian immigrants were protected by patrons and labored for food and ~helter.~'Before long, concentrators and mills replaced James's fields and orchards, and copper tailings gradually covered his home site. Thus, several generations of Italian workers-Mormon and Catholicworked on the land but in different ways.

New generations of Utahns will continue to discover how rich and diverse the tapestry of the state really is as they discover the hidden histories of our state's immigrants. Young Italians, Greeks, Germans, Scandinavians, and members of many other ethnic groups overcame tremendous obstacles to realize some portion of the American dream. For the most part, these immigrants willingly participated in the process that eventually resulted in "their virtual ethnic dsappearance." It was a price they were willing to pay for "a new identity and a new life."59The eventual acculturation of most immigrants and their unwillingness or inability to tell their own stories, make it more difficult for succeeding generations to discover their hidden histories. But the difficulties we encounter in discovering their histories is well worth the insight we gain into the unsung fathers, mothers, brothers, and sisters who literally built this state while they chased their dreams and established new realities for themselves and their posterity.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

57 These land records are located at the Salt Lake County Recorder's Office, Salt Lake City, Utah.

58 Some Italian laborers paid tribute to a "padrone" in exchange for employment; see Notarianni, "Italianit; in Utah," 307. Notarianni notes that a "paucity of source material may forever preclude a definitive study of the padrone system in Utah." The same is also true for the practice of Mormon patrons who offered board and room to young converts in exchange for labor on their farms and ranches.

59 Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised, 13,10.

Wakara Meets the Mormons, 1848-52: A Case Study in Native American Accommodation

By RONALD W. WALKER

In late summer 1848, a party of several hundred Utes arrived in Salt Lake City to meet the Mormons-members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints-who had settled in the region the year before. With the Utes was their famous headman, Wakara, who had won his laurels not so much by birth or family but by ability and charisma-and because of his success in adapting to new conditions. During the next four years, these gifts were to be amply displayed, and Wakara's interaction with the Mormons may be seen as a case study in attempted cultural adaptation.What were the tests and difficulties facing an able Native American who saw the advantages of a new culture? Could these challenges be overcome? Or was the conflict of culture too great for even a man ofWakara7sinclination and ability?

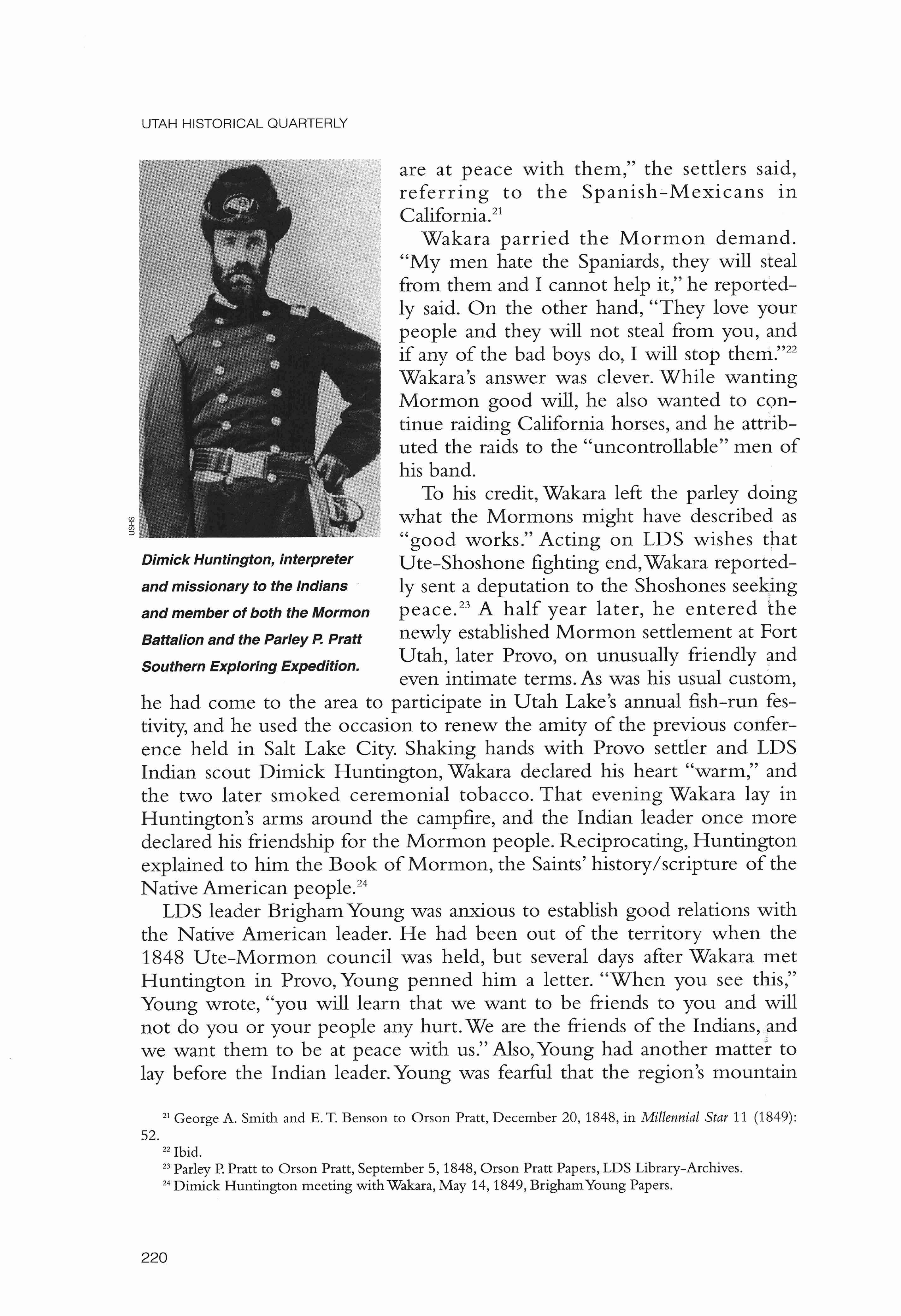

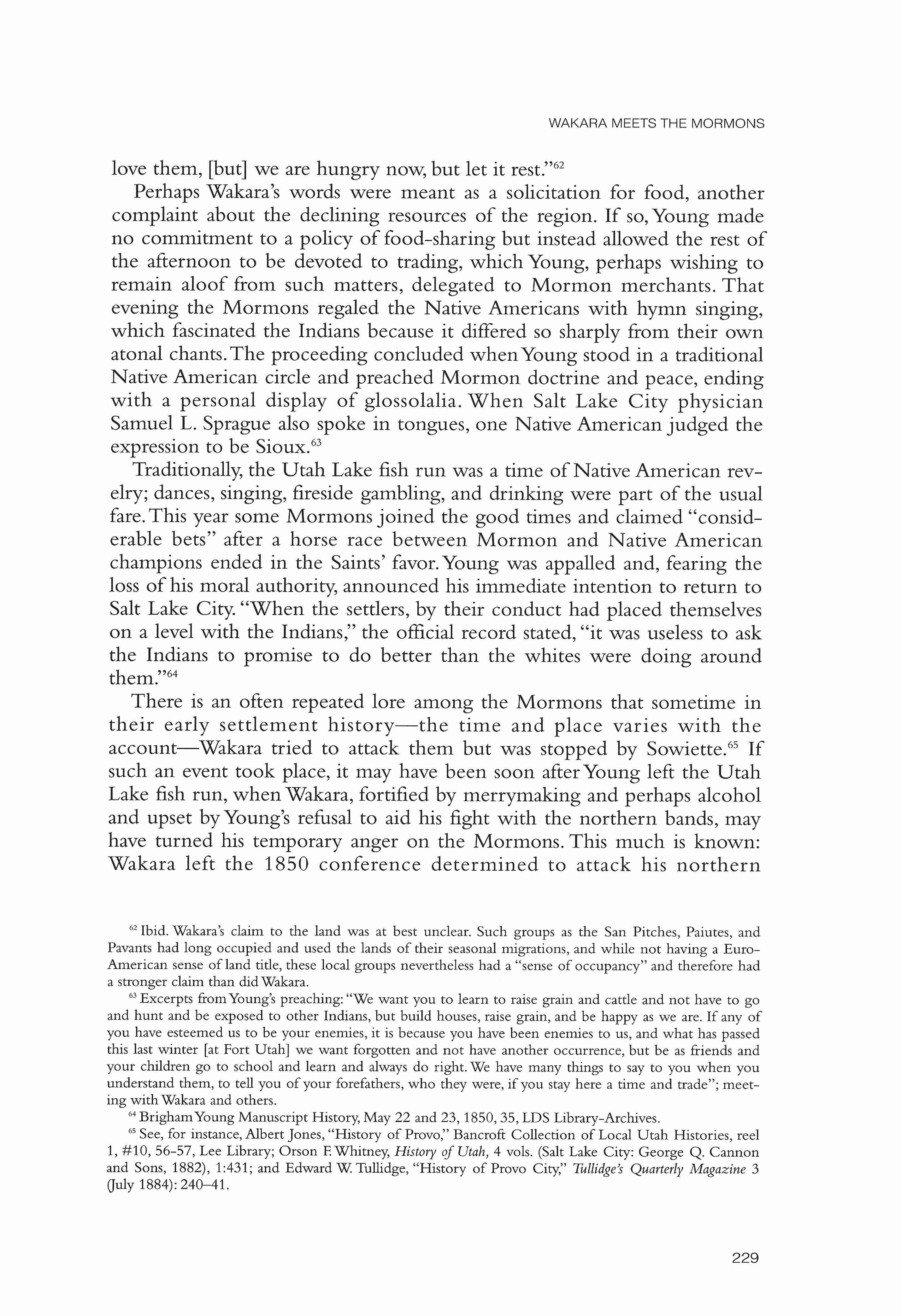

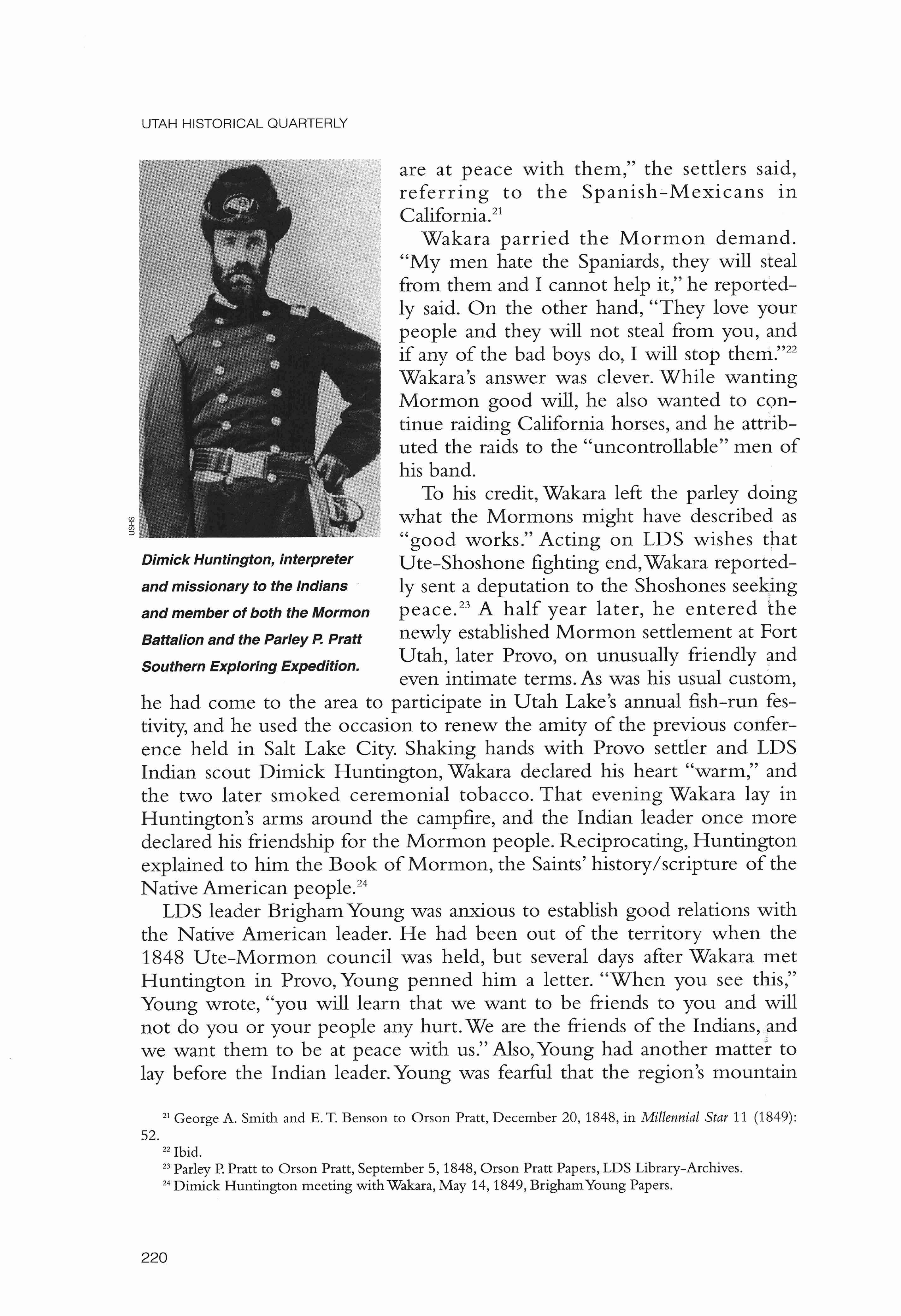

Of course, this article will only partly answer these questions.The historical sources, slanted toward the Euro-American point of view, are incomplete. Moreover, the first years ofWakara7sMormon relations hardly tell the full story. But what can be presented here is a largely untold account of Ute-Mormon interaction as well as informa- The Ute leader Wakaray depicted tion that suggests that there was cooperation and conciliation between the two peoples in a painting by Solomon along with the frequently cited incidents of CaNalho' a*isf/PhotOgrapher conflict.' for John C. Fremont's fifth Wakara was born about 1815 near the expedition.

Ronald Walker is a senior research associate at the Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for LDS History and professor of history at BrighamYoung University.

The best treatment ofWakaraYsculture and routine is Stephen PVan Hoak, "Waccara's Utes: Native American Equestrian Adaptations in the Eastern Great Basin," Utah Historical Quarterly 67 (Fall 1999): 309-30. Traditional and popularly written surveys of Wakara's career include Paul Bailey, Walkara, Hawk of the Mountains (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1954) and Conway B. Sonne, World ofWakara (San Antonio, Texas: Naylor Company, 1962).This article owes a debt to my colleague, Dean C. Jessee, with whom I am working to create a documentary record of Mormon-Native American relations. Jessee was particularly helpful in securing some of the documents cited below. I intend this article to be the first in a two-part series dealing with the Wakara-Mormon connection.

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

Spanish Fork River in north-central Utah. It is not known when he received his name, which meant "yellow" or "brass." Some have speculated that something yellow attracted his gaze when he was a child. Or perhaps he was so charmed by the color that he wore yellow war paint, rode a flaxen horse, or dyed his clothing yellow. Some said that even his gun had a yellowish hue. However unlikely some of these possibilities are, the settlers spelled his name variously as "Wacker," "Wacarra," "Wacherr," "Wakaron," "Walkarum," "Walcher," or the spelling that whites found most familiar, "Walker."2

At thirty-six years of age Wakara weighed about 165 pounds and stood five feet, seven and one-half inches tall, about the norm for EuroAmericans of the time. His eyes were dark, his hair "black and cut short," and his complexion a "reddish olive" tint.' But beyond these physical traits, there was little unanimity in descriptions of him. One man who knew him well called him one of the shrewdest of men, "a natural man" who "read from nature's book^."^ Others saw him as personable, dignified, and fearless. However, these estimates were balanced by still other reports that used "white man" epithets: He was crafty, craven, and self-seeking, and he had an unusually large head and bandy legs5 Adding to the confusion were the man's religious feelings, which seemed to baffle observers. Known to pray five or ten minutes at a time, he might speak of prophetic dream^.^ According to one narrative, once while hunting in the Uinta country, Wakara became ill, and for more than a day his body lay lifeless. During this experience, according to lore, Wakara was told that his life was not ended; people belonging to a white race would visit him, and he must treat them kindly. As a token of the supernatural interview, he was given the new name of "Pan-a-karry Quin-ker," or Iron Twister, perhaps a suggestion of his ability to resist death.This account has at least this much plausibility: In later years, Wakara made a point of saying time and again that he never had taken the life of a white person, nor would he.7

Childhood gaze: Dirnick B. Huntington, Vocabulary ofthe Utah and Sho-Sho-Ne, or Snake, Dialects, with Indian Legends and Traditions, Including a BriefAccount ofthe Lfe and Death of Wah-ker, the Indian Land Pirate (Salt Lake City, UT: Salt Lake Herald Office, 1872), 27.Appurtenances:William R. Palmer, "Pahute Indian Government and Laws," Utah Historical Quarterly 2 (April 1929): 37n. Gun: Alva and Zella Matheson, Oral Interview, 1968, p. 7, #336, Doris Duke Oral History Collection, Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City. According to one pioneer, the chief's proper name was "Ovapah"; see LeGrand Young, "The First Pioneers and the Indians," Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 12 (July 1921):99.

"Indian Measurements,"August 2, 1852, Indian Affairs Files, BrighamYoung Papers, Library-Archives of the Church ofJesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter LDS Library-Archives).

Huntington, Vocabulary ofthe Utah and Sho-Sho-Ne, 27.

For a sampling of sources, see Lynn R. Bailey, Indian Slave Trade in the Southwest (Los Angeles: Westernlore Press, 1966), 150; Bailey, Walkara:Hawk of the Mountains, especially 13; A. J. McCall, Pick and Pan: Trip to the Diaings in 1849 (Bath, NewYork: Steuben Courier Printer, 1882), 60; Dan Elmer Roberts, "Parowan Ward," 12, LDS Library-Archives; Sonne, World of Wakara.

"Utah Territory Militia and Nauvoo Legion Papers," March 16, 1854, reel #3, #1303, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City; General Church Minutes, June 4, 1854, LDS Library-Archives; diary of Robert Lang Campbell, December 7,1849, LDS Library-Archives.

' Huntington, Vocabulary of the Utah and Sho-Sho-Ne, 27; Jules Remy and Julius Brenchley, AJourney to

By heritage, Wakara was born a Tumpanawach (also called Tinpenny, Timpanogos, or Timpanogots), a branch of the Ute people that occupied some of the best land in the Great Basin, the flora- and fauna-rich eastern shoreline of Utah Lake. His father had been a minor Tumpanawach leader who, because he had refused to join a local fight, had been murdered. Wakara took his revenge by killing the perpetrators and then fled to live among the Sanpitch bands of central Utah. Using this region as his base, he assumed the new ways of the horse-mounted Utes.

The horse was revolutionizing Wakara's society. When the expedition of Dominguez and Velez de Escalante came through the area in 1776, it reported seeing no horses west of the Green River. However, within several decades British and American trappers were noting "a great number of good horses."' Indeed, mountaineer Warren Ferris saw not only horses but also skillful riding. Ute horsemen "course down ...[the] steep sides [of the mountains] in pursuit of deer and elk at full speed," said Ferris, "over places where a white man would dismount and lead his h~rse."~

Ferris's horsemen were probably Uintah or Colorado Utes. It took longer for Wakara's progenitors, more to the west, to adapt to the animal, partly because the horse was seen as a competitor for scant resources; if a horse came into the region, it was likely to be slaughtered for food. Moreover, there was the problem of caring for the animal. Wakara's father was one of the first Tumpanawach to own a horse, but it died from lack of food while tied to the corner of his dwelling.The Tumpanawach simply did not know "anything of the nature of the animal.'"o

A new material culture soon developed as the Indians of central Utah adopted the horse. Bridles, bits, and saddles were some of the new gear they now used. Instead of the brush-and-pole wickiup, the mounted Indians used the warmer and transportable buffalo-skin tepee. And instead of being confined to a relatively small food-gathering range, the mounted Utes could travel extensively, enjoy better foods, and engage in wider trade. William Ashley was astonished to find the Utes he encountered carrying English-made light muskets and wearing pearl-shell ornaments that the Native Americans said had come from a distant lake." Clearly, these Great Basin Indians had expanded their horizons both geographically and in terms of their personal wants and possessions.

The new horse culture allowed new economic patterns, especially the

Great Salt Lake City 2 vols. (London:W. Jeffs, 1861) 2:345-46; James Linforth, ed., Routefrom Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Wlley (London: Latter-day Saints' Book Depot, 1855), 105; and "High Priests' Minutes, 1856-1876," Salt Lake Stake,June 7,1854,122, LDS Library-Archives.

Dale L. Morgan, ed., "Diary ofWilliam Ashley, March 25 to June 27, 1825," Missouri Historical Society Bulletin 11:181.

Warren Angus Ferris, L$e in the Rocky Mountains, ed. LeRoy R. Hafen (Denver: Old West Publishing Company, 1983), 388.

lo Linforth, ed., Routefvom Liverpool to Great Salt Lake Klley, 105. l1 Morgan, ed., "Diary ofWilliam Ashley," 181-82.

WAKARA MEETS THE MORMONS

UTAH HISTORICAL QUARTERLY

trading of commodities. Items of exchange might include Ute buckskin, horses and mules, guns and ammunition, and household wares and trinkets. Another key staple was Indian "slaves," usually children or young women taken by the Utes from such weak and impoverished bands as the Paiutes of south-central Utah. These captives were then transported to New Mexico or California by the Utes themselves or by sombrero-clad, gaudilydressed "Spanish" traders, who were in fact usually New Mexicans. Technically, these "Indian slaves" were indentured servants who might be released from their servitude after several decades of service.12

Through some undocumented set of circumstances,Wakara came to personify this new Native American culture. By the late 1830s and early 1840s, his success gave him influence over the southern California trail. John C. Frkmont, who met him and his men in 1844, described his band's skill with more than a trace of admiration. "They were robbers of a higher order than those of the desert," said Frkmont. "They conducted their depredations with form, and under the color of trade and toll for passing through their country." Thus, rather than attacking caravans and killing the teamsters, these Native Americans asked for a horse or two and, to ease the pain of such taxation, sometimes gave a nominal gift in return. "You are a chief, and I am one too,"Wakara told Frkmont, suggesting the two trade gifts without calculating their respective value. Frgmont surrendered a "very fine" blanket that he had secured invancouver, while Wakara apparently reciprocated with a Mexican blanket of inferior grade."