3 minute read

In This Issue

Our perspectives are influenced by many factors—age, education, upbringing, experiences, to name just a few. As we seek to learn more about Utah’s past, fresh perspectives are always welcome. The first article for our summer issue offers just such a perspective. The twenty-one-year-old Leonard Swett made his first trip West in 1879 as a member of a United States Geological Survey expedition conducting scientific studies of the remote Colorado Plateau of southern Utah and northern Arizona. In a series of letters written to his parents in Chicago, Swett provides interesting insights about nineteenth-century Utah and Utahns as he describes his stays in Salt Lake City, Nephi, Cove Fort, Beaver, and Kanab.

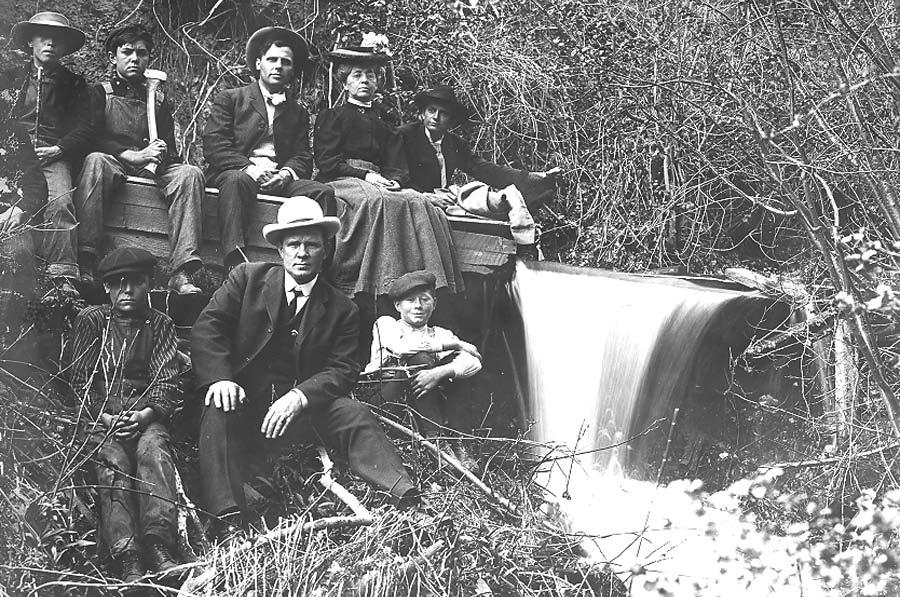

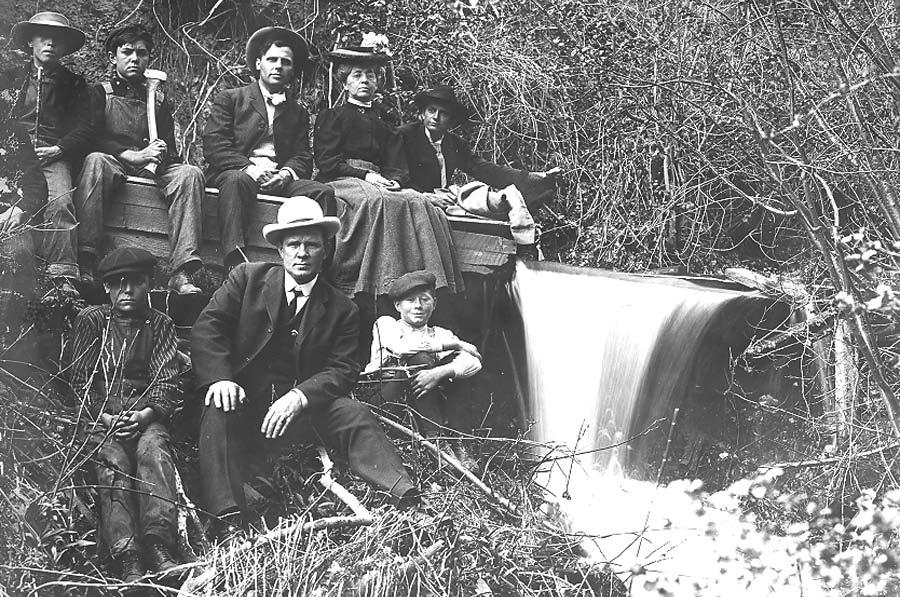

Visitors to Canyon Crest (Bountiful Peak) in Davis County May 14,1906.

PHOTOCREDIT: SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The events of Utah’s Black Hawk War that began in 1865 have been carefully documented. Our second article goes beyond an account of the causes, the raids, the pursuits, and the deaths to examine the economic impact of the war on the southwestern Utah settlements of Clover Valley, Shoal Creek, and Hebron when Brigham Young ordered the abandonment of outlying communities on the Mormon frontier. The policy created immediate economic and social hardships, especially for small and isolated settlements. However, abandonment and relocation also offered potential advantages that emerged in the aftermath of the Black Hawk War.

At about the same time Mormon settlements south of Utah Valley were being abandoned and consolidated under the threat of attack by the Ute leader Black Hawk, Clarence King conducted a reconnaissance survey of the north slope of the Uinta Mountains in northeastern Utah along the Utah Wyoming border as part of the United States Geological Exploration of the 40th Parallel. Timothy O’Sullivan,photographer for the survey, captured the majesty of the pristine wilderness in photographs he took in August 1869. Beginning in 2001,photographer and author Jeffrey S.Munroe,returned to the Uinta Mountains to relocate and rephotograph the scenes first recorded by O’Sullivan. We invite you to make an arm-chair summer trip to the Uinta Mountains to study the one-hundred-thirty-eight-year-old O’Sullivan images and compare them with the recent photographs to see what has remained the same and what has changed during the intervening years.

A forest ranger on the Mt.Timpanogos trail in 1930.

PHOTOCREDIT: SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

When agents of the Dutch East India Company first landed on the southern tip of the African continent in 1652,their interaction with native Africans began a three-hundred year process that culminated in an official policy of apartheid by the South African government in 1948.In the aftermath of the horrendous legacy of the recent Holocaust in Europe and with the seeds of a civil rights movement beginning to germinate in the United States, the discrimination and racial separation that characterized apartheid in South Africa seemed to go against the forces carrying the nations of the world toward a more humane and enlightened treatment of all citizens. The struggle over apartheid was intense, bitter, and, at times, deadly. As our final article in this issue illustrates, the anti-apartheid campaign reached all the way from South Africa to the campus of the University of Utah as protesters challenged the propriety of the school owning stock in companies that supported apartheid in the troubled African nation. After a series of petitions, demonstrations, protests, lawsuits, and arrests, the University of Utah Institutional Council voted in 1987 to divest the university’s stock in companies that supported apartheid in South Africa. Seven years later, the official policy of apartheid ended with the 1994 election of Nelson Mandela as president of South Africa .