44 minute read

The Salt Lake County Rotary Jail

The Salt Lake County Rotary Jail

By DOUGLAS K. MILLER

The last half of the nineteenth century was an age of Victorian scientific certitude in America. An optimism born of the industrial age and new technologies included the belief that these new technologies could remedy all social ills. One new technology developed during this era was a new kind of escape-proof jail that allowed a single jailer to manage up to forty prisoners without any physical contact with his charges. Seventeen (possibly eighteen) counties in the United States, including Salt Lake County, invested in this “latest improved and best classified prison heretofore invented or constructed on the part of thoroughly competent and scientific men.” 1

When the Mormons first arrived in what would become Salt Lake City in 1847, they made no attempt to create a government separate from the church. The only authority recognized by the people was that of the church and any breach of conduct or any dispute between parties was handled by ecclesiastical leaders. By 1850, however, the General Assembly of the State of Deseret passed an ordinance that provided for the election of sheriffs, and five years later Salt Lake County built a jail. 2

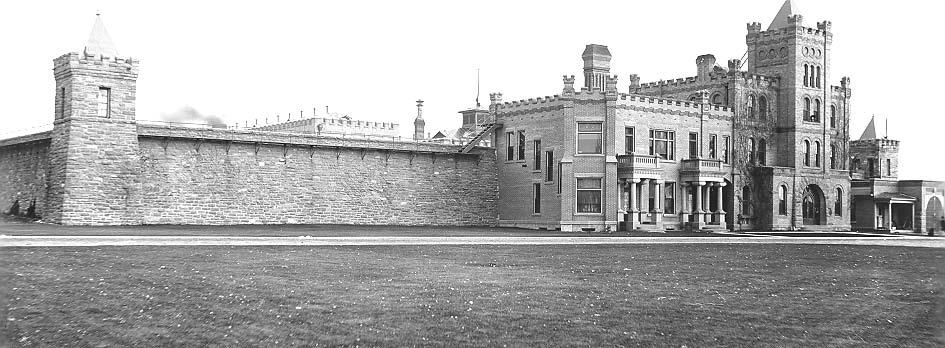

The sheriff’s residence in front of the Salt Lake County Rotary Jail.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Utah’s first known jail was in Salt Lake City and was made out of mud or adobe. According to the Utah correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, the jail was “divided into cells, and is surrounded by a high board fence… The calaboose was always guarded by eight men, who were changed every day, so fearful were the Mormons lest the prisoners should escape.” 3 The “calaboose” was replaced later with Salt Lake City’s “prison” at the rear of Salt Lake City Hall, which was part of Salt Lake County’s first courthouse, located on Second South between Third and Fourth West. This first county jail consisted of five damp underground cells in the windowless basement, which the Salt Lake Herald described as “oppressive and gloomy, and particularly defective as to ventilation.” The accommodations lacked bedsteads or elevated bunks, which made it difficult to keep the straw mattresses dry. 4 The Salt Lake Tribune reported that within the cells there existed “an odor of mould and a stench of filthy humanity” which became so sickening at times that the prisoners had to be moved upstairs into the courthouse, just to keep them from dying and where they were guarded at considerable expense. 5

When the first jail was constructed in 1855, the population in Salt Lake City was almost exclusively Mormon, but this would soon change. The advent of the railroad in 1869 made western migration easier for both Mormons and Gentiles alike. The population of Salt Lake County nearly doubled, from 31,977 in 1880 to 58,457 by 1890, and the increase in population resulted in a corollary increase in crime. 6 The Deseret News put it this way a decade later.

Overcrowding at the jail was never a problem, but the opposite frequently was. Prisoners often escaped, either by overpowering their guards or by sawing through the bars, and by 1887 the county recognized the need for a better facility.

In February 1887, the county court appointed Salt Lake City Mayor Francis Armstrong and Probate Judge Elias A. Smith to travel east to examine the latest in jail technology. It is not clear why the city mayor and a probate judge were sent on this errand for the county, but the Salt Lake Tribune quoted a dispatch from an unnamed Washington, D. C., newspaper that suggested that Armstrong and Smith were part of “a strong Mormon lobby” that were traveling to the nation’s capital “to work against the Edmunds-Tucker bill.” 8 The two men were gone for only a week, however, and made stops at Council Bluffs, Omaha, and St. Louis, Missouri, so it is doubtful that they could have also traveled to Washington, D.C. to engage in a lobbying effort. Even the anti-Mormon Salt Lake Tribune denied the rumor.

Upon their return, Mayor Armstrong announced that he favored the traditional square-cage jails he had seen in Omaha and St. Louis, while Judge Smith stated that “in his own mind . . . he had no doubt that the rotary jail was the one thing needful here.” 9

The new rotary jail, invented in 1881, was hailed at the time as the jail of the future, the latest product of a progressive and inventive age. 10 The Deseret News and the Salt Lake Tribune later described the rotary jail as “a whirligig in a squirrel cage,” a device that “looks for all the world like a huge rat trap,” and a “circular cell structure . . . turning upon conical steel rollers, like a railway turntable, with which we all are familiar.” 11

It might best be described in contemporary terms as a two-tiered lazy Susan with each platform divided into ten pie-shaped cells. The walls between the cells were solid plate metal to isolate the prisoners from one another, and at the outer perimeter of the circle were horizontal bars fixed in place off the turntable. The drum turned inside the stationary cage and was controlled by a single jailer turning a crank in an adjacent room. The jailer could rotate the entire cellblock and place any cell he chose in alignment with a single door that he could open by pulling a lever near the crank. This let the prisoner into a narrow passageway with three more doors: one to let the prisoner into an adjacent exercise corridor on one side, one to let the prisoner into a room with a “grub hole” where he picked up his meal on the other side, and one to let the prisoner into the room with the jailer. Unless the jailer opened the latter door, he could move the prisoners from place to place within the cellblock and never have any personal contact that would put him in danger. Also, the constant cellblock rotation discouraged prisoners from attempting to saw their way to freedom, as each time the jailer turned the crank, the prisoners were confronted by a new set of bars.

The original idea for a circular jail may have originated with British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who wrote an influential tract on penitentiary management in 1787. Bentham’s design, called the panopticon, consisted of cells along the outer perimeter of a circle. Solid walls between the cells isolated the prisoners while the grated openings facing a central guard tower subjected every convict to constant scrutiny. This created what Bentham called a “sentiment of an invisible omniscience,” which Bentham believed would have a redemptive effect on the prisoners. More importantly, he thought his design would allow the prison to operate with a smaller staff. 12

The inventors of the rotary jail, William H. Brown and Benjamin F. Haugh of Indianapolis, Indiana, altered Bentham’s design, moving the cells from the perimeter of the circle to the apex and mechanizing the cellblock to make it rotate. The altered design lost Bentham’s principle of invisible omniscience—the jailer could only see into one cell at a time—but in the tradeoff several benefits were gained. Brown and Haugh’s 1881 patent application stated: “The object of our investigation is to produce a jail or prison in which prisoners can be controlled without the necessity of personal contact between them and the jailer or guard, and incidentally to provide it with sundry advantages not usually found in prisons . . .” 13

The sundry advantages included running water and “flush” toilets in every cell, but these amenities were not provided for the prisoners’ convenience or comfort, but rather out of concern for the jailers’ well being. Before flush toilets were installed in jails, waste was deposited in buckets that the jailer sooner or later had to collect, with all the risks that devolved when a prisoner possessed a bucket of offal. Nevertheless, when the first rotary jail was built in Crawfordsville, Indiana, in 1882, when most private homes lacked indoor plumbing, these accommodations for the prisoners created a backlash. The Crawfordsville Weekly Review acknowledged that the jail was “uncrackable” but at the same time called it a monument to “the vanity of the . . . Board of Commissioners” who went so far as to have their names inscribed in stone above the front door. 14 These same county commissioners were soon voted out of office.

A “complete scientific system of water supply and sewer drainage” ran through a hollow cast-iron shaft, eight feet in diameter, that ran through the center of each circular platform. The shaft also served as the vent for the boiler in the basement. This dual use of the central core for smoke ventilation and plumbing created the advantage of preventing the pipes inside the stack from freezing in the winter. 15 How the plumbing system for these early “flush” toilets worked remains unclear, however, as the description offered in the patent application is rather cryptic.

The rotary jail built in Gallatin, Missouri, in 1887 may provide some insight into how the sewage system worked in some of the rotary jails. In the Gallatin jail the raw sewage from each cell had to remain in the toilet hopper until the cellblock was rotated, which allowed the pipe from each cell to line up sequentially with a single sewage outlet. This system of holding sewage, combined with the summer heat and poor ventilation in the Gallatin jail, sometimes resulted in an overpowering stench. 17 The sewage system in the Crawfordsville jail seems to have worked differently, however, as a picture in the jail museum shows a jailer in the basement pulling a lever to “flush” the toilets.

The patent holder/inventors, Brown and Haugh, built the first rotary jail in Crawfordsville, but later signed over their rights to an agent, Charles H. Sparks. The inventors were less interested in building jails than in securing sales for their ironworks, and the agreement allowed Sparks to engage other builders so long as the iron and steel came from Brown and Haugh’s foundry in Indianapolis.

The next three rotary jails, constructed in Maysville and Maryville, Missouri, and Council Bluffs, Iowa, were built by a firm from St. Louis, initially called Aldrich and Mann but later called Mann and Eckels. 18 18 Sparks then made an arrangement with the Patent Rotary Jail Company of Chicago, billed as “the exclusive manufacturer of the Patent Rotary Jail,” which built a rotary jail at Rapid City, Iowa, in 1886 and was in the process of building another at Appleton, Wisconsin, when Mayor Armstrong and Judge Smith left Salt Lake City in early 1887. 19

It is significant that the Salt Lake City men stopped in Council Bluffs, where the only three-tiered rotary jail had been completed just two years earlier. There is no record showing that Armstrong and Smith saw the rotary jail in Council Bluffs, but an article in the Council Bluffs Globe at about the same time called the jail a “pretty near failure” as it would not rotate properly on its axis. 20 This is corroborated by Walter A. Lunden, who found that all rotary jails built between 1882 and 1885 had mechanical difficulties with the gears, which made it difficult to turn the inner cylinder. Also, many prisoners in the early rotary jails suffered injuries to their arms or legs when these limbs protruded between the bars as the jailer turned the crank. 21 Perhaps it was these drawbacks that led Mayor Armstrong to favor the more traditional jail for Salt Lake City.

The two Salt Lake City officials also stopped in St. Louis, however, home to the Pauly Jail Building and Manufacturing Company, which, in spite of the Chicago firm’s exclusive claims, had also begun to build rotary jails.

Pauly claimed to be the largest jail-building company in the world and their Pauly Catalogue provides the sales pitch they may have presented to Mayor Armstrong and Judge Smith.

The Pauly Catalogue also acknowledged that “some of the first ones erected were slightly defective in some parts and have not proven as satisfactory in their operation as the inventers had intended, yet it only required a little experience in the application of mechanical skills to overcome all obstacles and bring it up to its present state of perfection . . .” 23

The catalogue highlighted six essential features of the rotary jail: (1) security of the prisoners, (2) safety of the jailer, (3) classification of prisoners, (4) perfect ventilation, (5) unexcelled sanitary arrangements, and (6) architecture. 24 Classification of prisoners referred to the fact that walls between the cells were solid plate iron, making it impossible for a prisoner in one cell to see the prisoner in another. This segregation meant that a man detained as a witness would “not be obligated to associate with the vulgar and unfeeling criminal.” It also allowed the jailer to offer better food and kinder treatment to more compliant prisoners while subjecting others to rougher fare and more severe handling, with none being the wiser as to their disparate treatments. 25

The other point that bears mentioning is the architecture. Pauly had an architectural office with over six-hundred plans to choose from, which allowed a county government to select a plan that would suit its needs without the added expense of hiring an architect.

Charles H. Sparks, who held the patent rights, was simultaneously an agent for the Pauly Company in St. Louis, and the Patent Rotary Jail in Chicago (despite the latter’s exclusive claims). He had secured a contract for the Chicago firm to build a rotary jail in Burlington,Vermont, in March 1887 and at about the same time secured contracts for Pauly to build a rotary jail in Sherman, Texas, in March 1887; in Gallatin, Missouri, in April 1887; and in Salt Lake City one month later.

This photograph shows the Salt Lake County Court House on the left, the Fremont School in the center, sheriff’s residence and Salt Lake County Jail on the right.

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The new Salt Lake City jail was constructed at 268 West Second South (between 3rd and 4th West under the modern street designations), next to the County Courthouse, which housed the old jail.

The Salt Lake Tribune offered this description of the design for the new county jail.

Construction of Salt Lake County’s rotary jail began in the summer of 1887.The Deseret News reported on the stone used on the new jail, “What is known as Parry’s stone quarry, situated three or four miles east of the cemetery near Ephraim, Sanpete County, produces a very beautiful kind of building stone . . . [and] ten cars have been shipped by Watson Brothers, of this city, this season, and five or six more have been ordered for the new county jail.” 27

The following July, the new jail was ready for occupancy. Pictures of the Salt Lake City facility, when compared with the jail in Crawfordsville, showed a very similar architectural plan. Each building had the same arch design over the main entrance and each structure on the left side of the entrance was very similar. Each also had a porch on the right side of the main entrance, though the pillar configuration of the supports on each porch was somewhat different. The rest of the Salt Lake City structure, however, on the right side of the main entrance, was much larger and more elaborate than the Crawfordsville edifice. The Salt Lake City structure was symmetrical; the right side mirrored the left, and a central steeple gave it the appearance of a church. 28

When the new Salt Lake County jail opened on July 4, 1888, seven prisoners were transferred from the old jail—one charged with housebreaking, one charged with robbery, two (including a woman) charged with vagrancy, and three charged with being insane. 29

Members of the grand jury who made a visit to the new rotary jail shortly after its completion reported “We have visited the new County Jail and found that institution everything that could be desired.” 30 Eight years later, another grand jury report conveyed the same sentiment. “We beg to report that we found the county jail in excellent condition; clean, well ventilated, heated and lighted; the culinary department well conducted; the attendants courteous and kind.” 31

The next detailed description of the jail is found in the Deseret News in 1902, fourteen years after it opened. The full-page feature article suggests that it is perhaps a misnomer to refer to the jail as strictly a rotary jail. The facility contained as many conventional square cage cells along the exterior walls as it had rotary cells on the drum in the middle. Each of the twenty conventional cells, or “side cells” contained a cot, a stationary washbasin, and a lavatory. The rotary cells had the same amenities, except hammocks replaced cots. The prisoners in the rotary, according to the Deseret News, disliked the hammocks but found them preferable to sleeping on cement or steel, so each soon learned “to woo his slumber in his swinging bed.” 32

The basement of the jail contained a dungeon, two dark cells in which the prisoners were put when they violated the rules. 33 No report has been found that suggested the dungeon was cruel, but an 1893 grand jury report complained that the cells were improperly located, as the prisoners placed therein “are usually very noisy, and we are informed their outcrys [sic] are plainly heard on the street, frequently attracting crowds of passers-by, thus creating a nuisance.” 34

The 1902 Deseret News article also explained that the worst prisoners were kept in the rotary where the bars, made with hardened steel, were more more difficult to cut with a saw. The bars on the rectangular side cells were made of a softer metal. 35 The Desert News described the rotary jail as

There were attempted escapes, however; the first occurring only two months after the new jail opened, though the incident had nothing to do with the rotary design. A jailer had taken a prisoner outside to work on the lawns and when the jailer became distracted, helping some plumbers inside, the unsupervised inmate ran away. 37

UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Four years later, in December 1892, the Salt Lake Tribune described another attempted escape and the report offers some insight into how the jail was run, including a gap in supervision.

In 1898 another prisoner tried to escape, this time by carving a pistol from wood and soap which he then “covered over with tinfoil so as to appear at first sight to be made of steel.” “It was an ingenious contrivance,” the Salt Lake Tribune reported, “and so closely resembled the genuine article that it would have completely deceived anyone who did not know it was an imitation.” The scheme was foiled, however, when another inmate informed the jailers of the plot. 39

PAULY CATALOGUE

In 1902, a prisoner successfully “broke out” of the rotary jail only because he had broken out with the measles. Inmate Frank Walsham, while awaiting trial for embezzling nine dollars, was released to the care of his relatives. “Now the mystery of the jail,” wrote the Salt Lake Tribune, “is how did Frank get it? Visitors . . . are required to leave their measles in the office before going inside, and the officers would like to know who smuggled them in to Frank.” 40

The only known successful escape from the rotary jail was made on February 1, 1907. On that morning, the jailers turned the rotary to get prisoner Charles Riis for court but found his cell empty. During the night Riis had sawed through the bars of his cell and then through the bars on the window. He then used two blankets tied together to lower himself to the ground. 41

The Ogden Standard Examiner called the escape an eye-opener for the Salt Lake officials and offered this explanation of how a prisoner held behind bars might get his hands on a saw.

Another article in the Standard Examiner suggested that the prisoners used oil and wrapped the bars with rags to muffle the sound of the sawing. 43

The Deseret News feature article on March 1, 1902, offers a snapshot of the Salt Lake County jail and of the type of convictions for the time. Among the inmates were Frank Blanchard, wanted on two continents for forgery; Dan Reynolds, a twelve year old incorrigible; C. E. Henry, an embezzler who sent his employer into bankruptcy; Thomas Hendrickson, serving three months for refusing to support his children; George Moore, a seventy-two year old Union soldier who said he stole a clock to keep from starving; George Beck, who represented himself as a charity worker soliciting funds for the widows and orphans of the recent Scofield mine disaster; Lucille Kert and Willie Black, two women, charged with robbing an Oregon tenderfoot of $1,100 on Commercial Street (better known as Salt Lake City’s tenderloin district); and Joe Harris, a black man charged with vagrancy, and “who fills the jail with old plantation melodies to the music of guitar and mandolin, which chases away the blues of prison life.” 44

Another occupant of the rotary jail was described as “a Chinese opium fiend.” He had been jailed for attempting to cut a countryman’s head off on Chinese New Year and was reportedly driven frantic by the jailer’s refusal to supply him with “yen hop” (opium). “He gets very little of it,” the jailer told the Deseret News, “but when it is furnished him he executes a demonical war dance, and his glee passes all understanding.” 45

Two men charged with murder, the only two homicides committed in Salt Lake City during 1901, were also in the county jail in 1902. Roy Kaighn, one of the two convicted murders, was described as a “lady’s man” who stabbed a traveling man. Willard Haynes, while “half drunk and drug crazed” killed his victim. The Deseret News reported, “Kaighn’s jail life has done wonders for him. He no longer has the wild, haggard, hysterical appearance . . . [but] today is healthy and strong with an appetite equaling that of any farm hand. The cigarette habit that was sapping his life out of him has been largely overcome and he no longer has access to opium or other like drugs.” 46

The jail’s most famous prisoner at the turn of the twentieth century was Peter Mortensen, a well-known Salt Lake City criminal. On Monday night, December 16, 1901, a reputable Salt Lake City businessman, James R. Hay, crossed the street to Mortensen’s house to collect a debt. Mortensen owed Hay’s employer $3,800 which Mortensen later said he had given Hay, but the next morning Hay was missing and the police quickly concluded that Hay had skipped town. James Sharp, the missing man’s father-in-law, however, accused Mortensen of murdering Hay, saying that “within twenty-four hours his body will be found in a field not more than a mile from this spot.” The next day the body was found in a nearby field and when Sharp took the witness stand at the preliminary hearing he declared that he knew that Mortensen had killed Hay because “God [had] revealed it to me.” 47

CRAWFORDSVILLE JAIL MUSEUM

In preparation for the trial, more than eleven hundred potential jurors were screened before twelve men good and true were finally seated. This was the longest jury selection process in Utah’s history and became drawn out largely due to Sharp’s claims of revelation. In the end Mortensen was found guilty, though not because of the revelation and was executed at the Sugarhouse Prison on November 20, 1903. The Deseret News then advised its readers that “henceforth all comment and discussion of the awful case be dropped.” 48

The only execution to take place at the Salt Lake County rotary jail took place on August 7, 1896. Charles Thiede, convicted of murdering his wife by cutting her throat, refused to choose the method of his death when the judge offered the firing squad or hanging. As a result, the judge decided for Thiede and chose hanging, granting Thiede the privilege of testing another scientific development of the age, a new type of gallows. Rather than being dropped through a trap door with a rope around his neck, as was the traditional method, a four-hundred-and-thirty-pound weight connected to a rope wound through pulleys was designed to jerk Thiede upward instead.

On the day of the execution,Thiede’s arms were secured at his sides and his legs bound together with straps. The Salt Lake Tribune described the scene this way:

Thiede’s pulse was taken at intervals, before and during the hanging. When taken from his cell that morning, his pulse was 118, and when the cap was placed over his head, it had jumped to 129.While he hung in the air his pulse ranged from 120 to 54, and then stopped altogether at 10:54, a full fifteen minutes after the weight had been dropped. Contrary to expectations, Thiede’s death was not from a broken neck, but from strangulation after hanging for a quarter of an hour. 50 This new method of executing criminals, though stored for years in the jail’s basement, was not used again.

Little information is available on other rotary jails across the country during this period, but the Pauly Catalogue suggested that all were functioning well.

But in spite of Pauly’s claims, no more rotary jails were built after 1888. Cost may have been a factor. The material costs for rotary cells versus conventional cells may have been about the same, but the additional cost of bearings, conical gears, and drive shafts, along with the additional installation costs would have made the rotary a much more expensive proposition. An additional disincentive was that the moving parts acquired through the extra expense only increased the risk of mechanical failure.

The most frequent problem with the jails as they aged was rust and rot to the cast iron shaft that formed the inner core to which the toilets were attached. Water exposure corroded the iron at the jail in Crawfordsville so badly that one inmate was able to pull a toilet off its mounting and crawl into the central shaft. From there he found his way to the basement and made his escape through the coal chute. 52 Something similar may have happened in Waxahachie, Texas, where the frequency of escapes was cited as a reason to close the jail. 53

Jailer inconvenience may have been another factor in the halt to further construction of rotary jails. The increased security the rotary promised seems to have come at the price of the jailer having to constantly turn the crank. It is possible, for example, that in order to serve each prisoner breakfast, the jailer had to crank the drum around to each cell, first for the prisoners on lower level and then for those on top. When breakfast was finished he had to do it again to retrieve the plates and silverware. He did this at every meal, then to let prisoners in and out of the exercise corridor and then to accommodate visitors.

TOP: Interior of the jail. BOTTOM: A jail cell in the jail.

This problem may have been solved in some rotary jails by the installation of an electric motor to turn the cylinder. The rotary jail in Oswego, New York, for example, seems to have been electrified, as indicated by an article in the local newspaper, although this solution created other problems.

The jail in Salt Lake City may also have been electrified, though the only evidence of this is a single line in the 1902 article in the Deseret News. “When a prisoner is wanted for any purpose a pull at a hand lever brings the rotary round to a point directly opposite the iron barred passage . . .” 55 The pull of a hand lever to move the platform, rather than the turn of a crank, suggests that by 1902, at least, the Salt Lake County rotary jail utilized some force other than human power to turn the cellblock.

The rotary jail in Council Bluffs was reputedly powered by a water wheel, which could keep the platform in motion all night when the jailer went to bed. A line in a 1927 Deseret News suggests that the Salt Lake County rotary jail also had this capability. “[P]risoners were not submitted to the torture of being turned around and around till driven half mad, as in an eastern center, [though] the construction was of the same type.” 56 In an earlier Salt Lake Tribune article, written a year before the rotary jail was built in Salt Lake City, it stated that “During the night when there is danger of an attempt to escape, the cells can be kept slowly revolving by a small water-power motor or any motive power most convenient.” 57 This is a line copied from the Pauly Catalogue, however, and may not reflect what was actually built in Salt Lake City. If the Salt Lake County rotary jail was in fact powered by water, the source of the stream between Third and Fourth West on Second South remains a question.

One researcher of rotary jails thought the drum might have turned on its own “by means of a heavy weight or spring.” 58 Perhaps the jailer wound a large spring and the tension was released in ticks, like the second hand of a clock, to keep the drum turning. Or perhaps a set of heavy weights hanging from chains worked, as in a cuckoo clock, to keep the rotary in constant motion throughout the night.

Another reason for halting the construction of rotary jails was concern for prisoners’ safety. In Crawfordsville, a prisoner got an arm caught between the bars during rotation, which necessitated the use of torches to cut him free. 59 In Maryville, Missouri, a prisoner’s head was crushed in the bars, resulting in the decision in 1904 to weld the rotary platform in place so it no longer turned. Doors were then cut in the outer cage to provide a separate entrance to each cell. 60

Counties were also increasingly sensitive to the issue of fire safety. A tour guide at the Gallatin, Missouri, jail noted that, “in the event of fire in the building, the prisoners would die miserably in their ‘squirrel cage.’ There would not be enough time to rotate each cell to the only exit and free the prisoners one by one.” 61

This marked the beginning of the end for the rotary jails. In 1905 the jail in Appleton, Wisconsin, was declared unfit and in 1909 the jail in Oswego, New York, was also condemned. Other jails have uncertain closure dates but may have also been closed in this timeframe. Of the rotary jails that remained, the jail in Wichita, Kansas, received the worst press. During World War I, when thirty members of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were held there for two years on wartime conspiracy charges, a prisoner gave this description:

The public perception of rotary jails was changing from a technological marvel to an inhumane method for the jailing of criminals. A commentary on the rotary jail in Wichita, Kansas, in 1918 stated: “There remains to be described a device for confining men that exhibits both ingenuity and perverted purpose. It combines the efficiency of modern invention with the insensibility of the thirteenth century. Yet it is defended by people who are no doubt quite humane in their private lives.” 63 An American Civil Liberties Union brief from that same year added: “Dante should have visited the Wichita [Rotary] Jail before writing his vision of Hell.” 64

The Salt Lake County Commission also seemed to be wary of the continued use of the rotary jail, and on April 12, 1909, adopted a plan to build a new county jail. The new jail, completed the following July, was located on the corner of Fourth South and Second East, where the new Salt Lake City library presently stands. The 1911 Salt Lake City Sanborn maps show that the building that had housed the rotary jail still existed but noted “Jail. Vacant. Concrete Floors” The next available Sanborn map (1927) shows the old Sheriff’s residence still standing but the jail behind the building had been demolished. What remained served as a private residence, then an apartment building, until it was destroyed in August 1927. 65

Of the seventeen (perhaps eighteen) rotary jails that were built, only three have survived intact into the twenty-first century: the jail at Gallatin, Missouri, with eight cells on a single tier; the jail at Council Bluffs, Iowa, with ten cells on each of three tiers; and the jail at Crawfordsville, Indiana, with eight cells on each of two tiers. Only the jail in Crawfordsville, the first rotary jail ever built, continues to function, though it, too, had once been disabled for safety reasons. 66

SHIPLER COLLECTION, UTAH STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

When the rotary jails disappeared they were quickly forgotten, even in the communities where they had once existed. When the Historical Society in Crawfordville decided to save their jail as a museum in 1973, they also began a quest to learn what had become of the other rotary jails built across the country. As a part of that pursuit, a letter was sent to Salt Lake County Sheriff Delmar Larsen in 1976 asking about the rotary jail in Salt Lake City. Larsen responded by saying,

Inquiries at the Salt Lake City Library evoked the same response. “We have checked into our old files and can locate no information at all concerning a rotary jail in Salt Lake City.” 68

Salt Lake City was not alone in this regard. Joseph F. Fishman, a former inspector of prisons, wrote in 1923: “As far as I can recall at the moment there are only two or three other jails of similar design in the United States.” 69 There were still at least ten in existence at that time. Likewise, early researcher Walter A. Lunden, wrote in 1959 that only six rotary jails had ever been constructed. 40 Not until the late 1970s, due to the efforts of Earl Bruce White of Crawfordsville, were seventeen, possibly eighteen, former rotary jail sites identified. But even White reports that he had lived in Pueblo, Colorado, for twenty-five years and passed the jail every day on his way to work, yet did not know that Pueblo was home to the last and largest rotary jail ever built. White’s best clues as to the location of the other rotary jails were contained in the documents he secured from the old Pauly Jail Building and Manufacturing Company in Saint Louis, which listed not only the jails that Pauly had built but included archival records from other companies, too. 71

It was Pauly’s reputation, experience, and marketing aggressiveness that undoubtedly spread the construction of rotary jails across the United States in 1887 and 1888. The Pauly Company built jails in Sherman, Texas, Gallatin, Missouri, Salt Lake City, Williamsport, Indiana, Oswego, New York,Waxahachie,Texas, Charleston,West Virginia, Dover, New Hampshire, Wichita, Kansas, Pueblo, Colorado, and possibly in Paducah, Kentucky.This new type of jail was a bold experiment in the management of prisoners, which emphasized jailer safety and, as a by-product, offered superior sanitary arrangements for the prisoners. When first introduced in the late nineteenth century, it was a symbol of a new scientific age and represented a progressive interest in applying science and technology to the social ills of the day. But over time that view shifted from a focus on technology to a view concerned with the occupants of the cells, and the very factors that had been the jail’s selling points became the jail’s liabilities.

NOTES

Douglas K. Miller is Director of the Children’s Justice Center in Davis County. He graduated from Weber State University with a BA in history and earned a master’s degree in educational psychology from the University of Utah. He lives in Ogden.

1 The Pauly Jail Building and Manufacturing Co., Catalogue (circa 1886),19.Photocopy in possession of Montgomery County Cultural Foundation,Crawfordsville,Indiana.Hereinafter referred to as the Pauly Catalogue.

2 Herbert Lester Gleason,“The Salt Lake City Police Department,1851-1949 A Social History”(master’s thesis,University of Utah,1950),7-13;and Deseret News,June 27,1855.

3 Harper’s Weekly, November 6,1858,copy in the Utah State Historical Society library.

4 Salt Lake Herald,March 6,1877.

5 Salt Lake Tribune,February 22,1882.

6 Allan Kent Powell,ed., Utah History Encyclopedia (Salt Lake City:University of Utah Press,1994), 432.

7 Deseret News,March 1,1902.

8 Salt Lake Tribune,February 16,1887.The Edmunds-Tucker bill was designed to combat Mormon polygamy,which created a new class of criminal offense,unlawful cohabitation and made it easier to prosecute plural marriages.

9 Ibid,,February 23,1887,and Salt Lake Herald,March 10,1887.

10 The Pauly Catalogue,19.This catalogue was produced by the Pauly Jail Building and Manufacturing Company about 1886.A photocopy is in possession of Montgomery County Cultural Foundation in Crawfordsville,Indiana.

11 Salt Lake Tribune,September 19,1898, Deseret News,March 1,1902,and Pauly Catalogue,21.

12 Jeremy Bentham, The Panopticon Writings,ed.Miran Boˇzoviˇc,(London and New York:Verso,1995), 29-95.

13 W.H.Brown and B.F.Haugh,U.S.Patent No.244,358,filed July 12,1881.

14Weekly Review (Crawfordsville,Indiana),July 1,1882.

15 U.S.Patent No.244,358.

16 Ibid.

17 Letter Lee Kreutzer to Kent Powell,August 28,2006,in possession of author.In the letter Lee Kreutzer recounts her tour of the rotary jail in Gallatin,Missouri.

18 For more about the rotary jail,its design and construction see Earl Bruce White,“The Rotary Jail Revisited,”unpublished paper Montgomery County Cultural Foundation,Crawfordsville,Indiana,c.1979.

19 Letter dated August 8,1886,on Patent Rotary Jail Company stationary,Pauly Archives,cited by White,“The Rotary Jail Revisited,”6.

20 Council Bluffs Globe,(Iowa) 1887,cited in Ryan Roenfeld,“Historic Pottawattamie County Squirrel Cage Jail,”p.11,The Historical Society of Pottawattamie County,Iowa,www.thehistor icalsociety.org/Jail%20extended.htm,(accessed May 4,2007).

21 Walter A.Lunden,“The Rotary Jail,or Human Squirrel Cage,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 18 (December 1959):149-57.

22 Pauly Catalogue,p.5.

23 Ibid.,25.

24 Ibid.,26-27.

25 Ibid.,19.

26 Salt Lake Tribune,July 23,1887.The newspaper stated that there would be twenty cells per tier but this was an error.There would be only ten cells per tier,each cell holding two prisoners for a total of twenty prisoners per tier.

27 Deseret News,August 10,1887.

28 As a part of the restoration project in Crawfordsville,which began in 1973,the surface paint was removed from the pillars on the porch and what is believed to be the original colors were discovered beneath.These colors have now been restored and the new paint reflects what the building may have looked like in its heyday.A color photograph of the Crawfordsville jail illustrates well what historians miss when they have to rely on black and white pictures.What is actually portrayed in both pictures,however, is not the jail but the sheriff’s residence.The jail components of the buildings were connected to the residence but located behind.The jail structure had an octagonal shape to accommodate the circular profile of the rotary.This can be seen in a photograph of a model of the Crawfordsville jail.The model also shows a back entrance where prisoners were brought in and out without having to pass through the sheriff’s residence.The sheriff’s residence at the Crawfordsville jail has been restored.The rotary cells in Crawfordsville contained metal bunks while the Salt Lake City rotary cells contained hammocks.The cells in the Crawfordsville jail were also larger than those in the Salt Lake City facility.The drum on which the cells were constructed was always twenty-four feet in diameter and the Crawfordsville jail had eight cells on each level while the Salt Lake City jail had ten.White,“The Rotary Jail Revisited,”16.

29 Salt LakeTribune,July 4,1888.

30 Deseret News,October 3,1888.

31 Salt Lake Tribune,November 11,1896.

32 Deseret News,March 1,1902.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid.,June 10,1893.

35 Ibid.,March 1,1902;Ogden Standard Examiner,March 28,1903.

36 Deseret News,March 1,1902.

37 Ibid.,September 19,1888.

38 Salt Lake Tribune,December 20,1892.

39 Ibid.,September 19,1898.

40 Ibid.,March 1,1902.

41 Ogden Standard Examiner,February 1,1907.

42 Ibid.,February 2,1907.

43 Ogden Standard Examiner,March 28,1903.

44 Deseret News,March 1,1902.

45 Ibid.

46 Ibid.Opium was legal to possess,or even eat,though smoking it was illegal and an arrest could only be made if the act of smoking was witnessed.The Salt Lake Tribune on May 12,1899,reported that “Unless the officers are able to break in and catch the fiends in the act of smoking,capture the layouts and the proprietors,it is useless to make a move for a conviction cannot be secured.”

47 Deseret News,January 23,1902.

48 Ibid.,November 21,1903.For a detailed account of the Peter Mortensen case,see Craig L.Foster, “The Sensational Murder of James R.Hay and the Trial of Peter Mortensen,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65 (Winter 1997):25-47.

49 Salt Lake Tribune,August 8,1896.

50 Ibid.

51 The Pauly Catalogue.Although Pauly takes credit for the jails at Crawfordsville and Burlington,these jails were actually constructed by other firms.

52 Conversation with Tamara Hemmerlein,Director of the Old Jail Museum at Crawfordsville,Indiana, May 19,2006.

53 John Hancock,“Ellis County’s Third Jail-1888”Ellis County Museum,Inc.,at http://www.rootsweb.com/~txecm/ellis_county_jail_1888.htm (accessed May 4,2007).

54 Palladin Times ( Oswego,New York),November 20,1945.

55 Deseret News,March 1,1902.

56 Ibid.,August 15,1927.

57 Salt Lake Tribune,July 23,1887.

58 Jonathan Dean,“The Old Jail Museum,”unpublished manuscript in possession of Montgomery County Cultural Foundation Crawfordsville,Indiana,circa 1980,7.

59 Conversation with Tamara Hemmerlein,The Old Jail Museum Director,Crawfordsville,Indiana,May 19,2006.

60 Roenfeld,“The Historical Society of Pottawamie County Squirrel Cage Jail,”p.11,www.thehistor icalsociety.org/Jail%20extend-ed.htm,(accessed May 4,2007).

61 Letter from Lee Kreutzer to Kent Powell,August 28,2006,wherein Kreutzer recounts her tour of the rotary jail in Gallatin,Missouri.Copy of letter in possession of author.

62 Letter from a prisoner in the Wichita,Kansas,Rotary Jail,October 8,1918.American Civil Liberties Union Papers,Volume 89,Firestone Library,Princeton University,Princeton,New Jersey.

63 Winthrop D.Lane,“What’s the Matter with Kansas? It’s Jails! Uncle Sam:Jailer,” Survey,(September 6,1919):811.

64 American Civil Liberties Union Papers,Volume 89,Firestone Library,Princeton University, Princeton,New Jersey

65 Deseret News,August 15,1927.The Salt Lake Polk indexes show that the building was the residence of Thomas S.Fowler from 1918 to 1924.It was thereafter subdivided into two apartments in 1925 and three apartments in 1927.

66 When this author visited the Crawfordsville jail in May 2006,the Museum tour guide,Elizabeth Shull in her seventies,turned the crank to rotate the cellblock without any difficulty.Elizabeth Shull had served as the jail matron for four years prior to the jail being closed in June 1973.

67 Letter to Earl Bruce White,October 22,1976.

68 White,“The Rotary Jail Revisited,”18.

69 Joseph F.Fishman, Crucibles of Crime:The Shocking Story of the American Jail,(New York:Cosmopolis Press,1923),49-50.

70 Walter A.Lunden,“The Rotary Jail,or Human Squirrel Cage,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 18 (December 1959):149-57

71 While visiting with the Director of the Old Jail Museum in Crawfordsville,Indiana,on May 19, 2006,I learned that the original Pauly documents had subsequently been destroyed and that the copies secured by White were all that remained.Copies of the documents have been donated to the Utah State Historical Library.